Over 4·4 million Canadians live in households affected by food insecurity, the inability to acquire adequate food due to limited financial means, according to data collected in 2017–2018(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell1). Statistics from other high-income countries also underscore the prevalence of this public health problem(Reference Pollard and Booth2–Reference Purdam, Garratt and Esmail6), while in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, signs indicate worsening food insecurity globally(7). Food insecurity is of concern because of its demonstrated links to a wide range of negative consequences, including poor physical and mental health, with a corresponding substantial toll on health care systems(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell1,Reference Tarasuk, Cheng and de Oliveira8) .

To date, policy and programme responses to address food insecurity in Canada have typically been limited to food banks and food-based programming, such as community gardens and kitchens, and workshops focused on food skills(Reference Bazerghi, McKay and Dunn9,Reference Tarasuk10) . Food skills are described as a ‘complex, inter-related, and person-centered set of skills… needed to provide and prepare safe, nutritious, and culturally acceptable meals for all members of a household’(11) and may pertain to cooking and food preparation. The appropriateness and effectiveness of responses to food insecurity that focus on food skills have been criticised because they do not address the inadequate financial resources and systemic inequities that underlie food insecurity(Reference Tarasuk10,Reference Loopstra and Tarasuk12,Reference Loopstra13) . In particular, the motivation for food skills workshops appears to rest upon the notion that individuals living in food-insecure households possess low food skills(Reference Tarasuk and Reynolds14–Reference Hamelin, Mercier and Bédard17). Workshops and other education-based interventions focused on improving food skills(Reference Fano, Tyminski and Flynn18–Reference Wilson, Matthews and Seabrook20) thus may aim to improve food resource management and cooking self-confidence through interactive learning opportunities(Reference Pooler, Morgan and Wong19).

However, research suggests self-perceived food preparation skills do not differ by household food security status among adults(Reference Huisken, Orr and Tarasuk15,Reference Hamelin, Mercier and Bédard17) and that adults affected by food insecurity have strong food skills and take pride in meals they create using limited resources(Reference Huisken, Orr and Tarasuk15,Reference McLaughlin, Tarasuk and Kreiger16,Reference Tarasuk21) . For example, almost all participants in a Canadian study of 153 low-income mothers prepared food from scratch at least once during the 3-d study period, with over half preparing food from scratch each day(Reference McLaughlin, Tarasuk and Kreiger16). Canadian adults affected by food insecurity have also been shown to be aware of healthy eating principles, but unable to engage in them due to limited financial resources(Reference Dachner, Ricciuto and Kirkpatrick22,Reference Power23) . Further, prior research indicates sufficient food skills are not enough to overcome financial barriers that underlie food insecurity(Reference Huisken, Orr and Tarasuk15,Reference Hamelin, Mercier and Bédard17) . More broadly, health literacy, which refers to an individual’s ability to engage in various health-related tasks(Reference Berkman, Davis and McCormack24) such as understanding and applying principles of healthy eating, may not be applied among individuals affected by food insecurity in favour of prioritising food affordability(Reference Huisken, Orr and Tarasuk15,Reference Dachner, Ricciuto and Kirkpatrick22,Reference Power23) .

Data on associations between food insecurity, food skills and health literacy are lacking among youth and young adults, whereas concerns about food deskilling and reliance on pre-made foods(Reference Chenhall25), as well as a lack of opportunities to learn how to shop for and prepare healthy and economical foods(Reference Wilson, Matthews and Seabrook20,Reference Colatruglio and Slater26,Reference Maynard, Meyer and Perlman27) , have been raised with respect to this population. For example, based on in-depth interviews with seventeen university students who recently transitioned to independent living, Colatruglio et al. (Reference Colatruglio and Slater26) identified limited educational opportunities as a contributing factor to challenges in developing and using food skills. In qualitative research by Maynard et al.,(Reference Maynard, Meyer and Perlman27) post-secondary students drew attention to their limited food skills, though their experiences of food insecurity were underpinned by inadequate financial resources.

The purpose of the current study was to assess associations between household food security status, self-rated food skills, an indicator of health literacy based on application of a nutrition label and meal preparation at home among a sample of young Canadian men and women, aged 16–30 years. Based on prior research, we hypothesised food skills, health literacy and the proportion of meals prepared at home over 7 d would not differ by food security status among men or women.

Methods

Data were drawn from the baseline wave of the Canada Food Study, conducted in October to December 2016(Reference Hammond, White and Reid28). Participants were recruited from five major Canadian cities (Vancouver (BC), Edmonton (AB), Toronto (ON), Montreal (QB) and Halifax (NS)) using systematic sampling and standard intercept techniques(Reference Hammond, White and Reid28). Participants were recruited from a sample of sites stratified by region/neighbourhood and site type (mall, transit hub, park or other shopping district). Additional details about the Canada Food Study are available elsewhere(Reference Hammond, White and Reid28).

Eligible individuals were 16–30 years of age, lived in one of the five cities and had access to a laptop, desktop computer or tablet with connection to the internet. Participants were provided CAN $2 upon recruitment and CAN $20 via e-transfer after completion of the study. In total, 6720 participants were recruited and sent an email invitation to complete an online survey in English or French that queried a range of information related to food, nutrition and health(Reference Hammond, White and Reid28). A total of 3234 (48·1 %) accessed the survey, with 2795 fully completing it and 439 partially completing it. After excluding those who did not complete the Food Source Dietary Recall (which was early in the survey), did not pass the data integrity check or had a pattern of unusual responses, the final sample available for analysis included 3000 participants(Reference Hammond, White and Reid28). For the current analyses, individuals with missing food security (n 234) or employment status (n 7) data were excluded. Additionally, a small number of individuals self-identified their gender as non-binary or did not identify their gender (n 40); almost a quarter of this group had missing food security data and the remaining individuals were excluded since the numbers were too small to allow reliable analysis. The final analytic sample included 2729 participants, 1389 men and 1340 women.

Household food security

Household food security status over the past 12 months was ascertained using a version of the Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM)(Reference Hammond, White and Reid29) adapted for online self-administration. The HFSSM was developed by the US Department of Agriculture(Reference Hamilton, Cook and Thompson30) and is widely used in food security monitoring and research, including in Canadian surveillance(31). Ten items reference adults in the household and eight items reference children under the age of 18 years. The items within the HFSSM range in severity from worrying about running out of food, to not being able to eat balanced meals and skipping meals, to going a whole day without food(Reference Hammond, White and Reid29). Based on the number of affirmative responses and coding used by Health Canada(31), households were determined to be food secure or food insecure. In households with children under 18 years of age, both adults and children must be classified as food secure for the household to be classified as such. In households without children, household food security status is equivalent to adult food security status. Those households classified as food secure affirmed one or no items on the HFSSM.

Food skills

As an indicator of food skills, participants were asked to rate their cooking skills as poor, fair, good, very good or excellent(Reference Hammond, White and Reid29). This single item was adapted from a rapid response module developed through qualitative interviews and focus groups, and field tested for use in the 2013 Canadian Community Health Survey(32). The response categories were collapsed into poor or fair, good or very good, or excellent(Reference Slater and Mudryj33). Analyses making use of this variable excluded two individuals who responded do not know or refuse to answer.

Health literacy

We also drew upon an indicator of health literacy based on a self-administered adaptation of the Newest Vital Sign(Reference Weiss, Mays and Martz34). To complete the Newest Vital Sign, participants were asked to use a nutrition label from a container of ice cream to answer six questions, querying items such as the number of calories in the entire container and the amounts that would provide specified amounts of carbohydrates and saturated fats(Reference Weiss, Mays and Martz34). Scores on the Newest Vital Sign have been shown to correlate with a measure of reading comprehension among children and adolescents(Reference Warsh, Chari and Badaczewski35) and with a test of functional health literacy among adults(Reference Weiss, Mays and Martz34). While the Newest Vital Sign was developed as a measure of patient health literacy, it has been noted to be potentially valuable in assessing how health literacy contributes to food-based decisions(Reference Mansfield, Wahba and Gillis36). Participants who answered 0 or 1 questions correctly were classified as having a high likelihood (50 % or more) of limited health literacy, while 2–3 correct answers were reflective of possibly limited health literacy and 4–6 correct answers reflective of likely having adequate health literacy. Analyses using this variable excluded 127 individuals who responded refuse to answer to any question in the module.

Location of meal preparation over the past 7 d

Participants were prompted to report the preparation location of each of their meals over the past 7 d, including breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks(Reference Hammond, White and Reid29). For each eating occasion, seven response options were possible: home, by you; home, by someone else (family, partner, friend); restaurant/take-out/cafeteria/vending machine; someone else’s home; did not eat; do not know or refuse to answer. A prior analysis of data from this sample showed high correlations (r = 0·89) between the proportions of meals prepared at home and outside the home based on these questions and a 7-d food record (unpublished results). For each eating occasion and for all eating occasions combined, the proportions of meals prepared at home were calculated. Meals prepared by the respondent and meals prepared by anyone in the household were considered since the respondent may not have had primary responsibility for food preparation. Those who did not report the location of at least one instance of each eating occasion over the 7 d were excluded.

Demographic variables

Demographic variables of interest were identified based on prior literature(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell1,Reference Tarasuk10,Reference Che and Chen37) and included age, gender, racial/ethnic identity, income adequacy, education and employment status.

Age was expressed by quartiles. Based on a question recommended by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research(38), participants were asked to identify as a man, woman, trans male/man, trans female/woman, gender queer/non-conforming or provide another response. As noted, participants who self-identified as non-binary were excluded from analyses due to the small sample size. Racial/ethnic identity was identified using two questions, one on racial background and a second on Indigenous identity. Responses were used by the Canada Food Study team to identify participants as White, Chinese, South Asian, Black, Indigenous (inclusive of those indicating another identity in addition to Indigenous) or mixed/other(Reference Hammond, White and Reid29). Mixed/other is reflective of participants who identified as more than one race/ethnicity (other than Indigenous) or did not provide a response(Reference Hammond, White and Reid28).

Income adequacy was assessed by asking participants to indicate how easy it is for them to financially support themselves(Reference Litwin and Sapir39). Options included very difficult, difficult, neither easy nor difficult, easy, very easy or do not know/refuse to answer(Reference Hammond, White and Reid29). For analyses, these categories were condensed into very difficult/difficult, neither easy nor difficult, very easy/easy and do not know/refuse to answer. The highest level of education the respondent had achieved or was currently pursuing was categorised as high school or less, Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel (2-year programme exclusive to Quebec that prepares students for university)/trade school/college, university and missing/not stated. Employment status was categorised as working full-time, working part-time and not working (either actively looking for work or not).

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS Studio, Version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Post-stratification sample weights constructed based on 2016 population estimates from Statistics Canada’s post-censal CANSIM tables were applied. For each age by sex group, weights were calculated as the population proportion divided by the sample proportion, ensuring the weighted sample aligns with known population proportions(Reference Hammond, White and Reid28).

Given the gendered nature of food insecurity and food preparation and skills more broadly(Reference Wilson, Matthews and Seabrook20,Reference Martin and Lippert40,Reference Olson41) , analyses were stratified by gender. Frequencies were run to characterise the sample according to demographic characteristics and household food security, food skills and health literacy. Binary logistic regression was used to determine if there was an association between each of food skills and health literacy and household food security status. These models included age, racial/ethnic identity, income adequacy, education and employment status as covariates.

The mean and median proportions of meals, by eating occasion, prepared at home were computed by household food security status and gender. Medians were reported in addition to means to account for the potential impact of skewed distributions. General linear models were used to examine associations between the proportion of meals prepared at home, either by the respondents or by any individual in the household, and household food security, adjusting for the demographic variables noted above. Separate models were run for each eating occasion (i.e., breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks), as well as for all eating occasions combined. To account for the potential impact of missing data on the observed associations, these models were repeated excluding participants who did not report a food preparation location for each eating occasion for at least 4 of the 7 d (this was not conducted for snacks because snacking was assumed to be less routinised compared with other eating occasions).

Statistically significant results were identified using a P-value of < 0·05 for all models. The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure(Reference Thissen, Steinberg and Kuang42) was used to account for false positives, with a false discovery rate of 0·05 applied to each regression and general linear model.

Results

Demographics

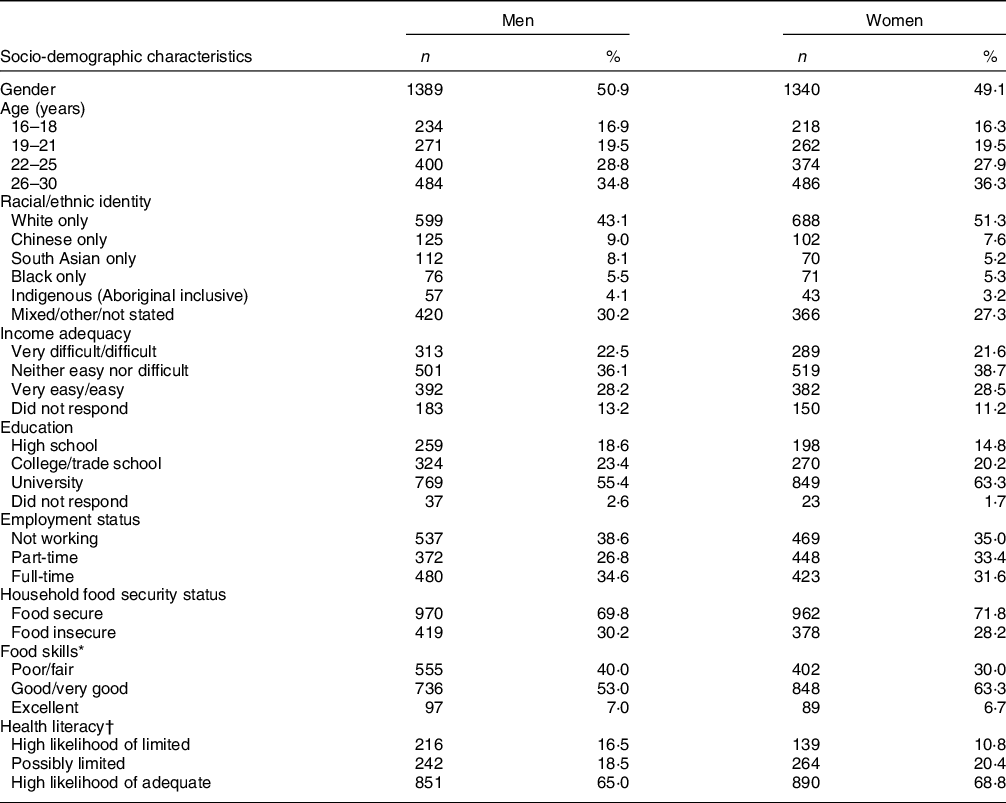

The sample included almost equal proportions of men (50·9 %) and women (49·1 %) (Table 1). Overall, 30·2 % of men and 28·2 % of women were classified as living in food-insecure households. Half of men (53·0 %) and six in ten women (63·3 %) reported their food skills as good/very good. Similar proportions of men (65·0 %) and women (68·8 %) were considered to have a high likelihood of adequate health literacy.

Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics, food security, food skills and health literacy by gender, Canada Food Study (n 2729), 2016

* Data on food skills were missing for one man and one woman.

† Data on health literacy were missing for eighty men and forty-seven women.

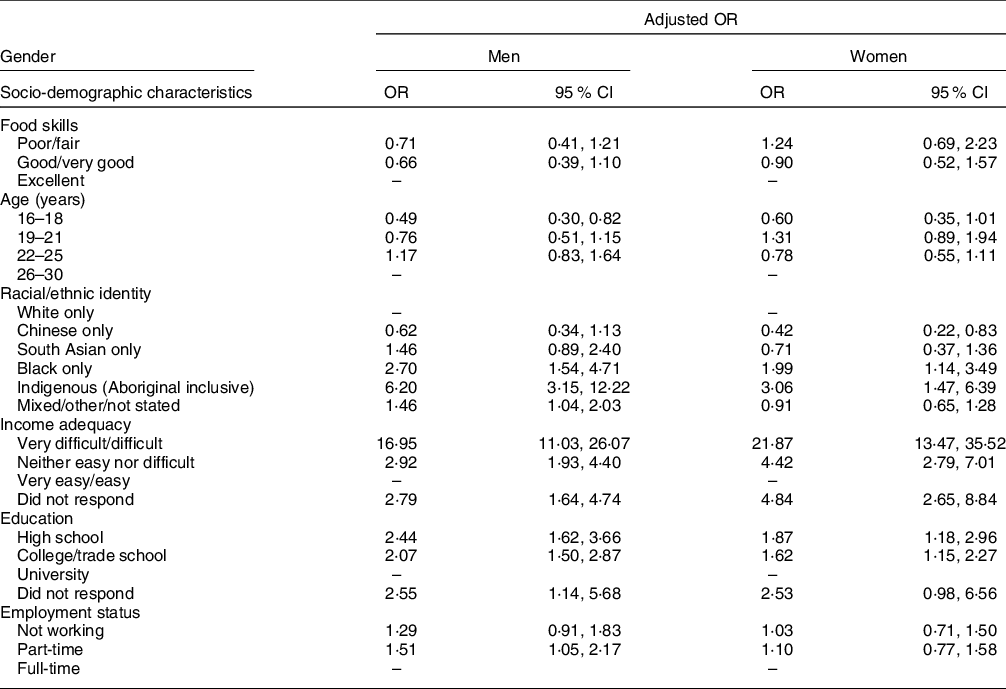

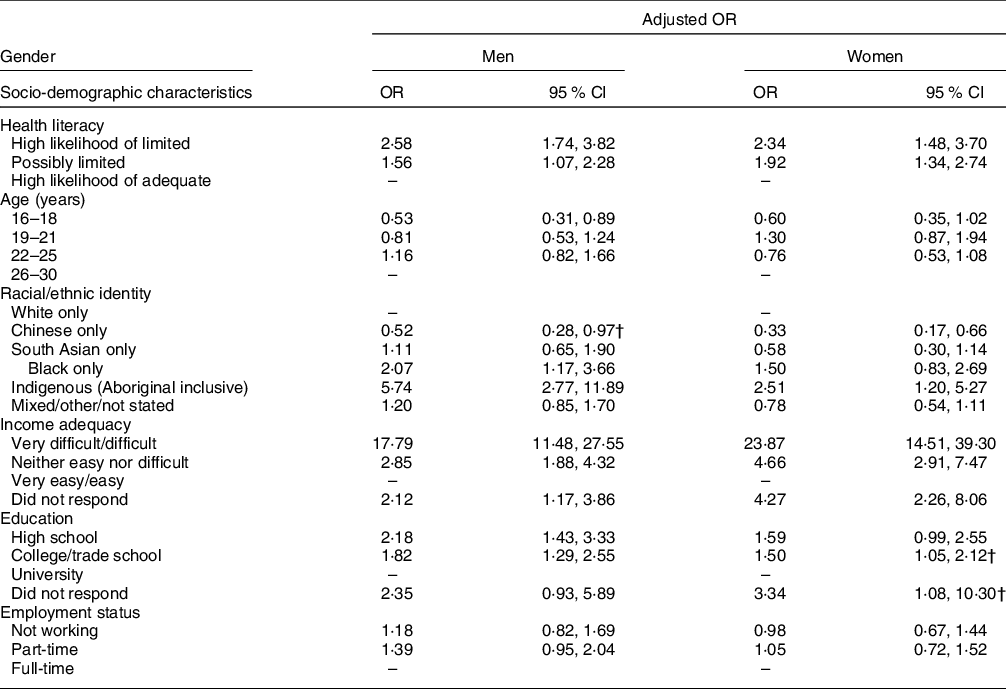

Adjusting for the demographic variables noted above and accounting for false positives, there were no differences in self-reported food skills by household food security status among either men or women (Table 2). Compared to men with a high likelihood of adequate health literacy, the adjusted odds of living in a food-insecure household among men with a high likelihood of limited health literacy and possibly limited health literacy were 2·58 (95 % CI 1·74, 3·82) and 1·56 (95 % CI 1·07, 2·28), respectively (Table 3). Compared to women with a high likelihood adequate health literacy, the adjusted odds of living in a food-insecure household among women with a high likelihood of limited health literacy and possibly limited health literacy were 2·34 (95 % CI 1·48, 3·70) and 1·92 (95 % CI 1·34, 2·74). According to each of the regression models assessing associations between food skills and health literacy and food security status, both men and women who identified as Black or Indigenous, reported experiencing financial difficulty and had less than a university level education were two or more times more likely to live in food-insecure households than their counterparts (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2 Adjusted OR for household food insecurity in relation to food skills, by gender, Canada Food Study (n 2727*), 2016

* Data on food skills were missing for one man and one woman.

Table 3 Adjusted OR for household food insecurity in relation to health literacy, by gender, Canada Food Study (n 2602*), 2016

* Data on health literacy were missing for eighty men and forty-seven women.

† After accounting for false discoveries using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure with a false discovery rate of 0.05, the estimate was not statistically significant.

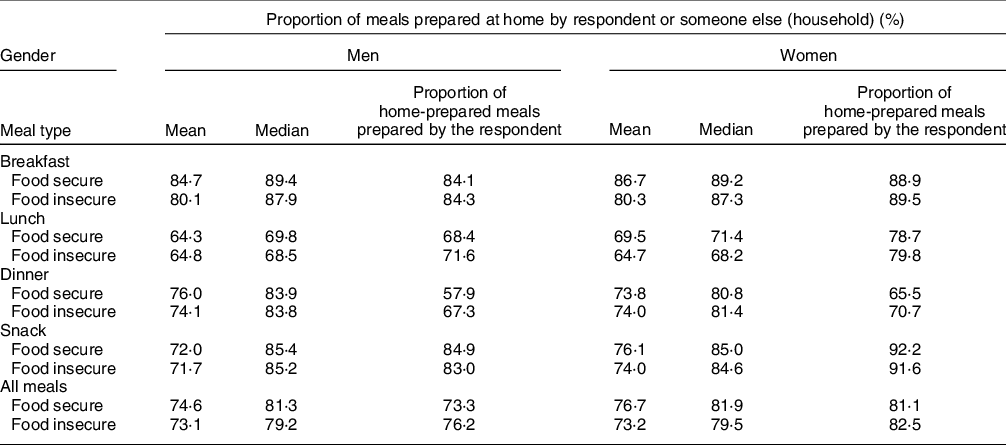

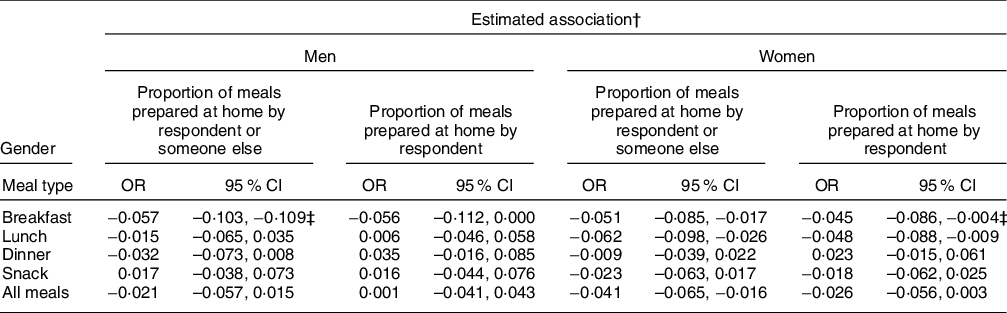

Among men and women who reported the preparation location for at least one of each eating occasion over 7 d, approximately 80 % of meals were prepared at home, regardless of household food security status (Table 4). In general linear models, adjusting for the demographic variables noted above and accounting for false positives, no significant associations between the proportions of meals prepared at home and household food insecurity were observed among men (Table 5). Among women, adjusting for other variables and accounting for false positives, the proportion of lunches prepared at home by the respondent was negatively associated with food insecurity (β = –0·048, 95 % CI –0·088, –0·009) (Table 5). This association was not observed when the model was repeated excluding those who did not report the preparation location of at least four lunches (Table 6). Among women, the proportions of breakfasts (β = –0·051, 95 % CI –0·085, –0·017), lunches (β = –0·062, 95 % CI –0·098, –0·026) and total meals (β = –0·041, 95 % CI –0·065, –0·016) prepared at home by the respondent or someone else within the household were negatively associated with food insecurity among women (Table 5). Significant associations for breakfast and lunch were also observed after excluding those who did not report the location of at least four of each of the eating occasions (Table 6).

Table 4 Mean and median proportion of meals prepared at home by gender and food security, Canada Food Study (n 2729*), 2016

* Seventy-two men and sixty women did not report the location of at least one breakfast, nineteen men and thirteen women did not report at least one lunch, three men and one woman did not report at least one dinner, and eighty-nine men and sixty-six women did not report the location of at least one snack.

Table 5 Adjusted association between the proportion of meals prepared at home and food security status by gender, Canada Food Study (n 2729*), 2016

* Seventy-two men and sixty women did not report the location of at least one breakfast, nineteen men and thirteen women did not report the location of at least one lunch, three men and one woman did not report the location of at least one dinner, and eighty-nine men and sixty-six women did not report the location of at least one snack.

† Estimates were derived from a general linear model adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, income adequacy, education and employment status.

‡ After accounting for false discoveries using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure with a false discovery rate of 0.05, estimate was not statistically significant.

Table 6 Adjusted association between the proportion of meals prepared at home and food security status among respondents who reported preparation location of breakfast, lunch or dinner at least four times by gender, Canada Food Study (n 2729*), 2016

* 272 men and 263 women did not report the location of at least four breakfasts, 116 men and 110 women did not report the location of at least four lunches, and forty-six men and forty-five women did not report the location of at least four dinners.

† Estimates were derived from a general linear model adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, income adequacy, education and employment status.

‡ After accounting for false discoveries using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure with a false discovery rate of 0.05, estimate was not statistically significant.

Discussion

In this sample of young Canadian adults, household food insecurity was not associated with self-perceived food skills. These findings are in line with prior evidence indicating food skills do not differ by household food security and that interventions aimed at improving food security by fostering food skills have largely been ineffective(Reference Loopstra13,Reference Huisken, Orr and Tarasuk15,Reference Fano, Tyminski and Flynn18) . However, men and women with lower health literacy, based on interpretation of a nutrition label, were more likely to live in food-insecure households compared to those with likely adequate health literacy. Further, small differences were observed in the proportions of meals prepared at home over 7 d between women in food-secure and food-insecure households.

Other research has similarly suggested that limited health literacy is associated with food insecurity(Reference Chang, Kim and Chatterjee43,Reference Butcher, Ryan and O’Sullivan44) . The measure of health literacy used in the current study consisted of a functional task using a nutrition facts label. It is likely those who are reliably food secure have more opportunities to practice the use of nutrition facts labels and similar numeric information, and that this may relate to their higher performance on this task(Reference Butcher, Ryan and O’Sullivan44). For example, those with constrained financial resources are likely to prioritise price, with lesser consideration of preferences and healthfulness(Reference Huisken, Orr and Tarasuk15,Reference Dachner, Ricciuto and Kirkpatrick22) . Thus, nutrition labels may not be regularly used, perpetuating the interconnection between inadequate health literacy, as assessed by this measure, and food insecurity(Reference Chang, Kim and Chatterjee43,Reference Sinclair, Hammond and Goodman45) . Consistently, research with Australian adults suggested those affected by food insecurity were less likely to use food labels, as well as to plan meals ahead of time and make a shopping list(Reference Begley, Paynter and Butcher46).

Alternatively, although our models included indicators of income adequacy and education, it is possible that the observed association between food insecurity and health literacy reflects relationships between health literacy and income and other indicators of socio-economic status. Indeed, prior research suggests that low health literacy is more common among those who are socially disadvantaged(Reference Schillinger47), including those with low income and education, as well as individuals identifying as non-White(Reference Sinclair, Hammond and Goodman45). While health literacy may be considered to be an individual-level construct related to ability or capacity(Reference Berkman, Davis and McCormack24), it is increasingly placed in a broader framework that recognises how health literacy interacts with the social determinants of health and the health care system(Reference Greenhalgh48). Indeed, in a synthesis of the evidence on health literacy and social disadvantage, Schillinger posits that low health literacy is not a diagnosis but should be viewed as a marker of life circumstances, including limited access to education(Reference Schillinger47). As such, low health literacy and its interactions with the social determinants of health and social disadvantage may reflect inequitable distribution of health-promoting resources and health-damaging exposures(Reference Schillinger47). Under this conceptualisation, then, both food insecurity and low health literacy are products of structural disadvantage rather than independent predictors of one another. Such structural disadvantage cannot be ameliorated by food skills workshops or other educational initiatives. Future investigations to elucidate how health literacy and food insecurity interact with one another and other social determinants will benefit from comprehensive measures of health literacy that appropriately capture the complexity of this construct among diverse populations(Reference Schillinger47).

The observation that women living in food-insecure households prepared a slightly lower proportion of meals at home compared with women in food-secure households may reflect efforts to cope with the financial constraints that define food insecurity. Previous research found that US adults living in food-insecure households made decisions about cooking dinner at home strategically to stretch financial resources(Reference Virudachalam, Long and Harhay49). For example, when time permits, home cooking may be employed, whereas purchasing inexpensive food outside the home may compensate for budgetary and time constraints(Reference Virudachalam, Long and Harhay49). Those in food-insecure households, for example, may be more likely to have precarious employment, with less control over their own schedules(Reference McIntyre, Bartoo and Emery50).

Research with Australian adults also suggests a lower likelihood of cooking meals at home using healthy ingredients and feeling confident about cooking a variety of meals among those affected by food insecurity(Reference Begley, Paynter and Butcher46). In that research, there was also an association between food security status and cooking skills, but with an item focused on whether respondents can or do cook. The difference in what was measured across studies, with a reliance on a single item capturing self-rated cooking skills rather than behaviours in the current study, may explain the differences in results given that those experiencing food insecurity may not have lower food skills but rather fewer opportunities to use them. This is borne out by the lack of associations observed between food insecurity and reported food skills, but some differences in the extent of food preparation at home by food security status in the current study. The potential for food insecurity to disrupt food preparation activities adds to the evidence underscoring the need for concerted efforts to ameliorate food insecurity, so all Canadians are able to engage in dietary practices encouraged by Canada’s Food Guide, such as cooking more often(51). Limited opportunities to engage in food preparation may contribute to reliance on pre-made and highly processed foods and impede healthy eating, contributing to diet-related chronic diseases(Reference Chenhall25,51) . Opportunities to engage in cooking and other food skills among young emerging adults may be particularly important given their newfound independence and the potential for dietary practices developed during this period to track into later life(Reference Christoph, Larson and Winkler52).

Although this sample may not be representative of young Canadians living in urban areas, the prevalence of household food insecurity is alarming, with almost three in ten respondents characterised as living in food-insecure households. It is challenging to compare the prevalence to nationally representative household-level estimates, but these also paint a worrisome picture, with over 4 million Canadians living in food-insecure households(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell1), even before the COVID-19 pandemic. The factors associated with food insecurity in this sample are markers of economic and social disadvantage, consistent with those observed repeatedly in other studies(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell1,Reference Tarasuk10,Reference Che and Chen37) , and include inadequate income and lower levels of education. Respondents identifying as Black and Indigenous also had higher odds of food insecurity, a pattern observed in analyses of nationally representative survey data and other Canadian studies(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell1,Reference McIntyre, Bartoo and Emery50,Reference Willows, Veugelers and Raine53) . These findings speak not only to the need for attention to policies such as universal basic income and minimum wage increases but also efforts to redress the complex and institutionalised ways in which some members of our society are systemically disadvantaged from full participation in economic, social and other systems(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell1).

While food skills were not associated with household food security status, 40 % of men and one-third of women in this sample self-reported their food skills as poor or fair. These findings highlight a potential role for food-related programming as a strategy that, in conjunction with system-level responses to address social and other determinants of health, may support improved dietary practices, including alignment with Canada’s Food Guide(51). Relatedly, the Government of Ontario (a province in Canada) is in the process of amending provincial curriculum for grades 1 to 12 to include courses focused on food literacy and healthy eating(Reference Kramp54). Under this Act, Food Literacy for Students, youth will engage in experiential learning to develop the skills needed to grow and prepare food, understand the local food system and make healthy food choices. It is of promise that such programming will be offered to all students rather than targeted to those assumed to be deficient in knowledge and skills based on low income, food insecurity or other indicators. However, given that one in five children in Ontario lived in food-insecure households(Reference Tarasuk and Mitchell1) even prior to the pandemic, focusing on food literacy within the curriculum in the absence of specific responses to redress food insecurity raises ethical concerns. Consistently, there has been a recent shift in the field of public health nutrition away from food skills defined narrowly towards the broader conceptualisation of food literacy. Food literacy encompasses the knowledge and skills to plan, manage and prepare healthy foods within the political, social, environmental and economic constraints of the food system(Reference Vidgen and Gallegos55,Reference Thomas, Perry and Slack56) . In particular, food literacy frameworks increasingly recognise that food knowledge and skills and the confidence to apply them cannot be successfully developed and used without the support of broader determinants, including financial capacity and socio-cultural influences(Reference Thomas, Perry and Slack56). Thus, joined-up approaches that address the broad range of factors that influence and shape eating patterns, and robust evaluations of those approaches, are needed.

Several considerations should be borne in mind in interpreting the findings. The current study provided an opportunity to examine food skills and other variables of interest among a large sample of Canadian youth and young adults. Though participants were recruited from five major cities across Canada and sampling weights were applied, the results are likely not generalisable to all young adults in Canada, such as those living in smaller cities and rural areas. The HFSSM was administered directly to respondents, including those under the age of 18 years who may not have a full understanding of the food situation in the household (though qualitative research suggests that even younger children are aware of food insecurity affecting their households)(Reference Fram, Frongillo and Jones57). Furthermore, food skills were ascertained using a single question that asked participants to self-report their overall level of food skills. Perceived food skills may be conflated with experiences of food insecurity in that inadequate food access (and other manifestations of poverty likely to accompany food insecurity) may limit opportunities to practice cooking and other skills. The measures of health literacy and food skills were also limited. Future research using more comprehensive measures of health and food literacy to better understand their interactions with food insecurity would be beneficial.

Reporting of the location of meal preparation may be affected by recall bias, as respondents were asked to retrospectively recall where they prepared their meals over the past 7 d, though a prior analysis suggested high correlation with a 7-d food record (unpublished results). Nonetheless, it is possible this 7-d period did not represent respondents’ habitual meal preparation practices. Some respondents may not have reported a preparation location for a given eating occasion because they do not routinely consume that meal (e.g., breakfast). The analysis was repeated excluding respondents who did not provide a food preparation for at least 4 of 7 d for each eating occasion, excluding snacks; this did not have a substantial effect on our findings. Further, skipping meals such as breakfast has been found to be uncommon across age groups in Canada(Reference Barr, DiFrancesco and Fulgoni58), though it is likely more common among those affected by food insecurity. Additionally, the proportion of meals prepared at home may be an overestimate of cooking from scratch, as previous work found that 25 % of home-prepared meals were derived from ready-to-eat or boxed foods(Reference Wiggers, Vanderlee and White59). It is also possible some respondents reported the location of meal consumption rather than preparation, although the questions emphasised the latter.

In sum, self-reported food skills were not associated with household food security status among this sample of young Canadians, whereas, among women, small differences by household food security status were observed in the proportions of meals prepared at home over 7 d. Men and women with lower health literacy were more likely to live in food-insecure households, though this finding may reflect links between low health literacy and factors also associated with vulnerability to food insecurity, including low income. Furthermore, food insecurity was pervasive, and the odds of food insecurity elevated among those with low income adequacy and education and those identifying as Black and Indigenous. Actions to address the economic and social disadvantage that underlies food insecurity are urgently needed.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This project has been made possible through funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the view of the Public Health Agency of Canada. Additional funding was provided by a PHAC-Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Chair in Applied Public Health (Hammond), which supports David Hammond, staff and students at the University of Waterloo. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: D.H. and L.V. designed the overall study, including the food source measures. D.H. secured the funding. D.H. and C.M.W. coordinated data collection. C.M.W. prepared the dataset. A.P. and S.I.K. formulated the research questions. A.P. conducted the analyses and led the drafting of the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the University of Waterloo Research Ethics Committee (ORE# 21631). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.