How judges and courts make decisions is undoubtedly central to legal studies. While forms of political control of the judiciary and of individual judges exist in every country, the specific dynamics of these controls differ drastically. But the institutional designs have nonetheless been a crucial factor in judicial decision-making process, both in liberal democracies and in authoritarian states. In the United States, for example, judicial politics depends upon whether judges are elected or appointed (Reference FriedmanFriedman 2009). In authoritarian regimes, in contrast, the institutional arrangements overwhelmingly affect judicial decision-making process, as demonstrated by a burgeoning literature on such courts around the world (see Reference Ginsburg and MoustafaGinsburg and Moustafa 2008).

The institutional environment in which Chinese courts and judges are embedded is also a key to understanding their decision-making process. The financial reliance of Chinese courts on local governments, for example, has generated incentives for local protectionism, and judicial independence is limited because the appointments of senior court officials are controlled by local political elites (Reference ClarkeClarke 1995; Reference HeHe 2011; Reference He2012b; Reference LubmanLubman 1999; Reference PeerenboomPeerenboom 2002). Institutional constraints, especially the measures on individual judges' performance, also markedly affect their decision-making (Reference HeHe 2009a). In addition, the institutional environment of judges has been an important factor in understanding the room for Chinese judges to make autonomous decisions (Reference SternStern 2010).

While this institutional approach has a lot to offer in understanding the judicial decision-making process in authoritarian regimes, it suffers from a paramount difficulty: some core judicial decision-making institutions are seldom accessible for direct examination. The adjudication committee (审判委员会) is the highest decision-making body in Chinese courts. We also know that the committee reviews and rules on the most complicated, controversial, and significant cases behind closed doors without hearing cases (Reference CohenCohen 1997, Reference Cohen2006). But more than six decades after the establishment of the People's Republic, and three decades after China's reforms, our understanding of this central decision-making body remains rudimentary. Since the meetings are not open, and the minutes are not available to the public or even to the involved parties, the details of the committee's operation remain mysterious. Earlier researchers have had to rely on legal regulations, sporadic interviews, published judgments, media reports, speculations, and anecdotal accounts (Reference ChenChen 1999; Reference HeHe 1998; Reference WooWoo 1991; Reference WuWu 2006; Reference ZhuZhu 2000). Although these works are capable of providing insights, they work through the rather narrow interpretative lens of academic or legal professionals. The objectivity of these studies would be greatly augmented by direct examination of the systematic data into the operation of the adjudication committee.

This lack of data also makes it difficult to assess important academic debates. Since the 1990s, the committee has been the focus of what might be the most provocative debate on judicial reforms in Chinese jurisprudence. The committee has been criticized for lacking transparency, for violating due process, and for undermining judges' judicial independence (Reference ChenChen 1999; Reference CohenCohen 2006; Reference HeHe 1998; Reference LubmanLubman 1999; Reference WuWu 2006). While many critics urge its reform if not its abolition, some scholars, most notably, Zhu Suli, the former dean of Beijing University Law School and a pivotal legal theorist, argue that the committee performs many indispensible functions in the local context (Reference ZhuZhu 2000; cf Reference UphamUpham 2005).

The debates center on three aspects at the heart of China's judicial reforms: legal consistency, judicial independence, and corruption (see Reference Peerenboom and PeerenboomPeerenboom 2010: 77–78). First, the defenders claim that the committee contributes to consistency in adjudication within a jurisdiction by bringing the specialized knowledge and experience of the committee members to bear on complicated cases. The critics, however, argue that the committee has become an institutional haven for judges who are uncomfortable in ruling on difficult cases, thus discouraging judges from improving their judicial skills (Reference WuWu 2006). Second, the reformers argue that because the committee imposes decisions on the judges hearing the case, judges have little latitude to issue their own rulings (Reference HeHe 1998). The defenders, however, argue that this system indeed creates a united front against external pressures and thus preserves the independence of the judiciary as an institution (Reference ZhuZhu 2000). Finally, according to its defenders, the committee institutionalizes supervision, which can limit corruption—it is easier to bribe a judge or two than it is to bribe nine or ten members of the committee (Reference ZhuZhu 2000: 112). The reformers counter that to influence the decision, one only needs sway the more powerful members (Reference HeHe 1998; Reference WuWu 2006).

Without a systematic empirical inquiry that can open this black box, however, these arguments are difficult to evaluate. Critics and defenders of the committee alike base their arguments on institutional description and analysis with, at best, some sporadic interviews with judges. Given their different perspectives and individualistic impressions, it is natural that the two sides make opposite points. When anecdotal and attitudinal evidence is used as the basis of the debates, either side can easily prove that the other is completely wrong.

Drawing on the archival minutes of the committee in a lower-level court in Shaanxi province for 2009, and supplemented with interviews with relevant judges and secondary literature, this article not only contributes to the understanding of the decision-making process in Chinese courts, but also sheds light on the debate. Given the vast size of China and its tremendous regional variations (Reference ZhuZhu 2007), the data from a single court within a single year would certainly not lead to comprehensive and accurate picture of the committee. It will, however, answer several crucial questions about the functioning of the committee, its operational patterns, and the underlying logic. Are the cases reviewed really complicated, controversial, and significant? What percentage of suggested opinions of the adjudicating judges are changed, and why? Whose opinions count? Does the committee make better decisions in terms of evidence admission, fact discerning, and application of the law? How is the operation of the committee related to the socio-economic conditions of the region? The data and analysis shall provide further fuel for the ongoing debates on the role of the committee as well as on the relationship between the judges and authoritarian regimes more generally.

Data and Methods

The court is located in southern Shaanxi Province, western China. About a third of its 430,000 residents live in the countryside. The economy of the region grew during the initial stage of the reform period, but by 2008, the income per capita for rural and urban residents had reached only around 4,000 and 14,000 yuan, respectively (CNY).Footnote 1 Since 2006, the courts have heard slightly fewer than 3000 cases annually, most of which were civil, criminal, and enforcement. Overall, the jurisdiction of the court is of medium scope for China's lower-level courts (see Reference ZhuZhu 2007: 218).

Through a collaborative research project between a local law school and the court, the archival minutes of the adjudication committee became accessible. As a visitor of the law school, I was invited to advise the court staff on how to write investigative reports. One of the research projects of the court then was to examine the functioning of the adjudication committee and I was thus granted access to the minutes. Since under Chinese law, the minutes are not publically accessible, I was only allowed to read the minutes in a court office. I could take notes on the minutes, but not photocopy them. The court has given me permission to use the information for my own research, on condition that no case or individual's identification shall be disclosed, to avoid potential impact on cases that had been decided. To understand the stories behind the minutes, I interviewed five judges who had been involved in reporting some of the cases. Due to the sensitive nature of the topic discussed, I did not tape-record the interviews. Instead, I took notes of the interviews and compiled them immediately after the interviews.

Two handwritten volumes from 2009 contain the minutes of deliberations on all the reviewed cases. This is the most recent year in which most of the cases had already been settled, even if the appeal process was initiated. With all the pages running continuously and consistent with the content at the beginning, it is clear that no cases had been removed because of their sensitivity or other concerns. Compiled manually and threaded together through punched holes, the minutes are supposed to be kept indefinitely. For each case, there is a standardized cover page, the upper half of which records the time, venue, attending members, reporting judge, and recorder. It is followed by court letterheads if the other half of the cover page cannot accommodate the discussion content. The poor quality of the letter paper is indicative of the financial constraints upon the courts.

It is surprising that none of the minutes have been signed. Should not the committee members have signed their names for what they said and decided? I was told that in most situations, the meetings are held for the purpose of making a decision or finding a solution. Since the decision is made collectively, no single committee member is held personally responsible. It is less important who says what. It is, therefore, in nobody's interests to check the accuracy of his remarks (all the members of this court were male). Indeed, the committee members never bothered to read the minutes. As long as the final decisions are not incorrectly recorded, a missing sentence or two is nobody's business.

Nor were voting records found. According to Article 10 of the Organic Law of the Courts, the decision of the committee shall follow the majority rule, so one would expect to see voting records. The fact, however, is that the committee rarely took a formal vote. As shown in the minutes, in the situations where there was a decision, it had been reached by consensus, no matter whether or not there were debates. When expressed opinions were impossible to reconcile, the president's words were final: either to seek further opinions from the higher-level courts, or to ask the adjudicating judges to continue their investigation. As will be shown, the hierarchical structure in which the members are embedded leaves little room for formal voting.

One will also be disappointed if she wants to find written evidence of corruption and illegal interferences. This is because while the meeting is confidential, unlawful activities are unlikely to be formally discussed. Even if they were discussed, only a thoughtless recorder would faithfully record them since it is no less than setting a time bomb for the committee.

What, then, can one learn from the minutes? Because these minutes are not intended for the eyes of the litigation parties or their lawyers, the recorders have no reason to hide something that is the routine practice, even if an outsider would see such a practice as inappropriate. For example, in many cases, the minutes clearly state that the court needed to avoid political trouble by looking for an out-of-court “political solution” to a dispute whose pure legal resolution might have proven embarrassing. In numerous situations the committee decided to seek instruction from the higher level courts. This indicates that the decisions of the committee, whether politically sensitive or not, were accurately recorded.

More directly for the purpose of this article, the minutes record the subject matter of the cases, the suggested opinions of the adjudicating judges, and whether the committee supported or overruled the opinions. They also clearly state the sequences of the discussion, and more importantly, who had the final word. Recording what happen at the most decisive moment for the case outcome, the minutes speak volumes on the intersection of the law, power, and politics. I know of no other work whose data offer such a close look at the decision-making process in the judicial systems of the Chinese or other authoritarian states.

The Committee

The origins of the adjudication committee can be traced to the early 1930s, in the communist settlements in rural China during the revolutionary period. According to historical records, the committee was set up because adjudicators had little professional training, and because policies, guidelines, directives, and statutes were difficult to apply uniformly. To ensure justice, it was better for a committee to make a collective decision based on majority rule (Reference WuWu et al. 2005: 19). This arrangement was later incorporated into the judiciary of the PRC, as the highest decision-making body in adjudication (PRC Organic Law 1983 Art. 10; SPC 1999 Art. 22). Although many reforms and improvements have been made since then, the organic structures remain largely unchanged.Footnote 2

As Chinese courts are now bureaucratically organized with a finely differentiated hierarchy of ranks, the adjudication committee, as an internal institution of the courts, from its composition to operation, is heavily influenced by the administrative ranking system. While the procedure laws make it clear that the major function of the adjudication committee is to adjudicate significant and difficult cases and to summarize adjudicative experiences,Footnote 3 the administrative ranking is in reality the determining factor in the appointment of its members. It usually consists of officials with the highest administrative rankings in a court (Reference ZhuZhu 2000). This Shaanxi court is no exception. The committee was composed of not only the president, the vice presidents and the heads of the major adjudicative and enforcement divisions, but also the disciplinary inspector. They were appointed simply because they were the members of the Party leadership, who were the de facto court leaders. Moreover, the terms of these judges are for life, and replacements have been rare. Once appointed, a member would not be removed except for illness, retirement, or leaving the court. One original head of the no. 1 civil division, for example, kept the appointment when he was transferred to the enforcement bureau as the vice director, a position not necessarily associated with the membership. Another original head of the no. 1 division had kept the appointment after retiring as division head. In short, membership has become a symbol of power and status.

While to review significant or complicated cases is the major task of the adjudication committee, there are no legislative definitions of what is “significant” or “complicated.” This arrangement leaves individual courts to have their own detailed definitions. While the working rules of the adjudication committee on the reviewing scope in many courts include a rather limited amount of cases, this Shaanxi court's are quite extensive.Footnote 4 The followings are only more related to the purpose of this article: a case that a judge or panel cannot resolve through consultation with immediate superiors (item 2), cases involving local institutions or powerful figures (item 11); administrative adjudication cases (item 9). In addition, the following criminal cases shall be reviewed: cases involving suspended sentencing, exemption of punishment, acquittals, monetary fines, institutional crimes, corruption, and serious criminal cases which may invoke ten years or more of imprisonment (item 5). For civil cases, it covers those involving government agencies, mid- and large-sized enterprises, foreign invested enterprises, class action, migrant workers, newly emerged cases, or disputed amount of money in excess of three million yuan (items 9–10). The rules ends with “other cases or questions the committee regards necessary”(item 17).

Procedurally, there are two possibilities that a case will be reviewed: one is directly determined by the court leaders, including the division heads and the (vice) presidents, when they regard so doing as necessary; the other is initiated by the collegial panel or the adjudicating judge. According to procedure laws, all cases are either decided by the normal procedure by a panel usually composed of three judges, or the summary procedure with only one adjudicating judge. In practice, there is always a designated responsible judge, while other judges on the panel are largely symbolic. The responsible judge, or the adjudicating judge when the summary procedure is employed, is the reporting judge.

Since 2008, the court has required the reporting judge to submit a written report prior to the meeting, describing the basic facts and her or the panel's suggested positions.Footnote 5 When the turn for her case comes, she is summoned to the meeting to orally explain the facts and proposed positions, and answers questions, but not to participate in the discussion. She leaves the meeting venue once the discussion of her case is over. The reporting judge will then photocopy the minutes and place the copy into the case file as an inaccessible appendix. As the judge responsible for the case, she incorporates the decision of the committee into the judgments, beginning with the standardized sentence “according to the decision of the adjudication committee of this Court.” As an entrenched practice in Chinese courts, no reasons are provided for the committee's decision. Nor is the composition of the committee disclosed.

Cases Reviewed

In 2009, the committee held 47 meetings, almost one each week, of which 46 discussed cases. In total, it reviewed 430 cases. In most situations, the meetings lasted for a whole morning. Many or most cases were handled relatively quickly because the committee discussed, on average, more than nine cases in each meeting, so each case was discussed only for approximately 20 minutes.Footnote 6

As shown in Table 1, the vast majority of cases reviewed were criminal, with a modest amount of civil cases. Of course the committee also reviewed all the administrative adjudication cases and some enforcement cases. But similar to what Liu documents in another lower-level court in northern China (Reference LiuLiu 2006), only a few administrative cases were filed, reflecting the tremendous difficulty of administrative litigation in China (Reference PeiPei 1997). Even fewer cases could survive formal adjudication, because many ended as withdrawal or reconciliation, due to the pressures of the government agencies and the “harmonious” efforts of the court in persuading both parties to compromise. When some of them (five in the year) eventually entered into the meeting of the committee, the issues were more procedural than substantive. It usually involved the approval of the committee, for example, on the government decision on compulsory housing demolition, which invoked little discussion. Similarly, most enforcement cases were reviewed merely because the committee needed to fulfill the procedural requirements. I will focus here on the civil and criminal cases.

Table 1. All Cases Reviewed by the Adjudication Committee in the Shaanxi Court (2009)

Note: Upholding means that the committee upheld the suggested (majority) opinions of the adjudicating judge or the collegial panel.

Criminal Cases

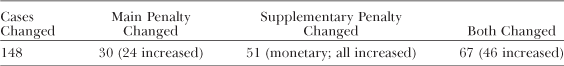

Several patterns are clearly seen in the above table. First, virtually all the criminal cases (96.8 percent) were reviewed by the committee, as a result of the rules on the jurisdiction of the committee. Put differently, among all the cases reviewed by the committee, 84.4 percent were criminal. Second, in these criminal cases, the committee modified almost 41 percent of the suggested opinions of the adjudicating judges, much higher than the equivalent of civil cases (8.3 percent). Third, the committee tended to increase the penalty, and especially the fines of the defendants (Table 2). Among the 51 cases in which only supplementary penalties were changed, all of the fines were increased by 1,000 to 10,000 yuan. This pattern could also be found in the cases that ended with suspended sentences. Among 103 such cases, the committee upheld 96 percent of the recommendations, but changed 42 percent of the cases on supplementary penalties, including the probation period, suspended duration, and fine. Once again, the changes for fines were generally unidirectional—more often than not, they increased.

Table 2. Suggested Opinions Modified by the Committee in Criminal Cases

These patterns indicate, first of all, that the committee spent most of its energy not in streamlining legal criteria or developing general legal rules, but in discussing specific cases, most of which were routine, or even trivial.Footnote 7 As almost all the criminal cases were reviewed, this point seems only too obvious because it is impossible for a basic-level court to hear so many significant and difficult cases. This can also be inferred from the duration of discussion on each case: after all, how can the committee make an informed decision on a complicated case within only 20 minutes? The criteria of “significant and difficult” are not just stretched very far, but are almost non-existent. Second, among criminal cases that were modified, the committee has usually changed in favor of longer suspended sentences and especially increased monetary fines. In one injury case, for example, the collegial panel suggested a three year sentence, but suspended for four years. Three members agreed with the suggested opinion, but another three believed that since the injury caused “serious damage” (a legal standard), a suspended sentence should not be adopted. The final decision followed the suggestion of the president: “In my subjective view, it is okay to award suspended sentence. For this sort of cases, settlement [between the defendant and the victim] shall be encouraged. In this case, the defendant already compensated the victim, and it just reaches the standard of the serious damage. It is fine to lengthen the suspended sentence to five years.”

One obvious reason for this unidirectional change is that the court is underfunded and therefore has an interest in increasing the monetary penalties. Inadequate funding has been a chronic problem for courts in less developed areas (Reference HeHe 2009b). The problem was exacerbated after the central government lowered the litigation fees so that more people would have access to court (State Council 2006). Even after the central government started to provide partial support in 2009, the financial situation of the court has not changed much. When litigation fees as the main income source were cut off, the court has had to rely on criminal monetary fines. In one case, indeed, the minutes recorded what the president said: “The defendant gets a penalty below the stipulated sentencing level, so he shall pay some fines. If he does not pay, eight years will be imposed; otherwise six years.”

Why did such a change have to be made by the committee, the highest adjudicating institution which is supposed to deal with the most difficult and significant cases? In other words, if the court wants to impose heavier monetary penalties to increase its income, it can simply make it clear in its internal instruction to the adjudicating judges; there is no need to change all these cases through the adjudication committee. Inadequate funding of the court thus is only part of the story.

Two other explanations based on interviews are plausible. One is that the committee needs to do something in reviewing the cases. As shown, it is a policy of the court that almost all the criminal cases be reviewed by the committee. If the committee does not make any changes, there is no reason for such a policy. When the committee does make changes, it wants to be sure that those changes are indeed safe to make. Then to increase the monetary fines or nominally heavier penalties becomes an attractive choice, because they are within the stipulated level and thus will never be regarded as an incorrect decision.Footnote 8

The other is more fundamental and systemic. The criminal trial is, arguably, most vulnerable to judicial corruption. The defendants are more willing to offer bribes to the court and judges because their freedom is at stake. On the other hand, the requests from the defendants in criminal cases are easier to grant because the resistance from other litigation parties is weaker than in civil cases. In civil cases, each penny that one party requests has to come from the other party; but awarding the criminal defendant a shorter term of imprisonment, lower monetary penalty, or a suspended sentence for what would have been an actual sentence requiring stay in prison does not directly harm the interest of the victims or the prosecutor. It would thus encounter much weaker resistance from them (Reference Li and PeerenboomLi 2010: 218). In other words, it is less likely that in criminal cases they would oppose such lighter sentencing or report on potential corrupt activities. As a result, an effort that tends to exonerate the defendants is suggestive of contamination or even corruption. On the contrary, any effort to increase the penalty of the defendants is seen as aboveboard. Consequently, all the members are willing to show that they are independent and have no connection whatsoever with the defendants by suggesting slightly heavier penalties.

One might argue that the increases are attempts by the committee to counteract inappropriately lenient punishments resulting from the corruption of the adjudicating judges. This explanation is problematic, however, because only a small proportion of the increases are related to the main penalty (Table 2) (i.e., whether to offer suspended sentence or not, or increase the duration of the actual sentence), which is the most likely area involving corruption. The majority of the changes thus do not limit the corrupt activities of the adjudicating judges. It is more likely that the adjudicating judges and the committee act tacitly in this process: the adjudicating judges make a suggestion, and the committee makes primarily cosmetic changes.

Civil Cases

In contrast, the committee reviewed 48 civil cases in 2009, among which only four suggested opinions were changed. The committee decided to request written instructions from upper-level courts for seven cases. In other words, the committee upheld 58 percent of the suggested opinions of the adjudicating judges. Again, few of these cases were doctrinally difficult.

Why were 41 percent of the suggested opinions in criminal cases modified while only 8 percent of civil cases were? The dynamics here differs from those of criminal cases in many aspects: the reasons for reviewing, the nature of the cases, and the relationship between the judges/courts and the litigants.

The reviewed cases could be divided into two categories: significant, and difficult to resolve. The significant cases usually involved external influences. In one doctrinally straightforward contractual dispute on breach damages (hereafter Contract Case), the plaintiff, a local enterprise, obviously with the support of prominent political figures, refused to compromise with the defendant, a company based in X province. Believing that he would be able to influence the decision through upper-level officials, the plaintiff did not even attend several hearings. The responsible judge had to visit the plaintiff's business site and plead him to sign the paperwork. The court leaders, apparently under heavy external pressures, only instructed the adjudicating judges to try their best to render a decision favoring the plaintiff. The plaintiff, however, was still dissatisfied. When the committee reviewed the case a second time, a decision was simply to change the composition of the collegial panel.Footnote 9

For the second category, usually it was the adjudicating judges who requested a review. The reason for review is simply that, as reported by Yang, “the facts are complicated, the litigants are emotional, which may lead to adverse social consequences” (2010). They did so not because they held different opinions from their immediate superior, and not because the legal issues were too complex, but because it was hard to find an appropriate solution in the local context. Submission to the committee simply provided a way out.

A divorce case illustrates this point. A wife filed a petition for divorce, but her husband contested it. The marriage had been extremely tense: the wife left home and the husband searched for her throughout the city. As a result of this broken relationship, he became mentally unstable. While the wife insisted on a divorce (死也要离), the husband threatened to kill his estranged wife and their child (离了就死). In addition, the two sets of in-laws and especially the wife's mother had been interfering in the couple's relationship. Although the law is clear on the issue—to grant divorce or not depends on whether the emotional relationship between the two parties is disrupted—it is not helpful at all for solving the dilemma. The adjudicating judge decided for adjudicated denial for the first-time petition but the wife filed the petition again six months later. While an adjudicated divorce would customarily have been granted in the second-time petition (Reference HeHe 2009a), the adjudicating judge felt uncomfortable doing so.Footnote 10 Under the circumstances, submitting the case to the adjudication committee was to be a feasible option and so she did, suggesting another adjudicated denial. Needless to say, the committee upheld the suggested opinion. After all, nobody wanted to bear the blame if the husband carried out his murder threat.

This case shares several characteristics with many civil cases submitted to the committee by the adjudicating judges: legally and factually straightforward, monetarily inconsequential, confrontational between the two litigation parties, difficult to enforce, likely to trigger violence, and unlikely to benefit from the litigation parties. All these explain why there are no equivalent compulsory reviewing requirements for civil cases, as for criminal cases. The adjudicating judges, however, have every reason to take the initiative to submit. In submitting the case for review, the adjudicating judges may hope that the committee could provide a better solution. But in most situations, they are aware that it is almost impossible. Imagine, if the adjudicating judges, having deliberated on the cases during the whole process, still could not find a viable solution. How can the committee members have a better idea, given the fact that most members are not specialists in the field and are not even familiar with the pros and cons of the case?

The real reason for submission lies in that the committee is a good shelter for avoiding risk: having sought the committee for decision, the adjudicating judges can exempt themselves from potential responsibility even if the decision indeed culminated in violence. After all, the decision is the committee's. As the very least, the responsibility has been diluted. An interviewed judge said: “If a decision is made by a single judge, he or she is 100 percent liable for the decision. If made by the collegial panel with three judges, then only one third for each.” The reality is that, since the 1990s, not a single committee member has ever been penalized for what he said in the adjudication committee.Footnote 11

When a difficult civil case (difficult in the non-legal sense) such as this is submitted, rarely has the committee changed the suggested opinions. The can would be kicked down the road: the committee would either uphold the proposed opinions, or seek instructions from the upper-level court—another tactic to avoid risk. The committee upholds the suggested opinions not just because it does not have better solutions, but also because proposing new solution is not sensible: if a committee member proposes a new solution which turns out badly, the member only hurts himself, or loses face among colleagues at the very least. In contrast, upholding the proposed opinions involve little risk: even if the solution suggested by the adjudicating judges is later proven bad or wrong, it is the judges who shall be blamed: after all, the judges are the ones who handle the cases in person and shall thus understand the case more thoroughly. Furthermore, unlike most criminal cases, this type of civil cases involves much less opportunity to benefit from the litigation parties, a fact well-understood by everyone in the court. Subsequently, the committee members do not need to “prove” they are clean.

Whose Opinions Count?

Existing studies suggest that the discussion of the committee follows a set pattern: usually with the judge adjudicating the case reporting first, then members raising questions, and the president remaining silent until the end (Reference WuWu 2006; Reference ZhuZhu 2000). This sequence has also been stated in some court documents (e.g., SPC 2010). The rationale for the president to keep silent until the end is straightforward: it allows him to evaluate the discussion without prejudicing it or influencing the views of individual members.

The minutes, however, indicate that this pattern was far from clear–cut. For many of the cases, there was virtually no discussion: the cases were so clear-cut that there was no need for discussion; the president just made the decision. For cases with some discussions, the director of the relevant division spoke first, followed the vice president. It was also true that in many other cases, the president or vice presidents spoke first. Overall, once the president or the vice president of the division proposed a solution, the discussion ended because other members usually concurred. As one interviewed judge said: “The rule is that the president shall keep silent until the end, but there is no way to enforce such a rule. When the president wants to have control, he can simply speak first to set the tone. Can any other member stop him from speaking? Of course not. “The point is reiterated by another interviewed judge who has more than ten years of experience reporting cases to the committee: “Even if the president speaks at the last, but when other members realize that his opinions differ from theirs, they would try to amend their original positions so to stay with him.”

If Woo elaborates upon the critical influence that the president has over judicial decision making by analyzing the legal regulations (1991: 102–03), the data here provide statistics that indicate the extent to which the president controls the final decisions of the committee. Take the criminal cases as an example,Footnote 12 among the 148 criminal cases in which the suggested opinions of the adjudicating judges were changed, 135 (91 percent) were changed largely according to the suggestions of the president, 11 (7 percent) were changed according to the director of the criminal division. Only 1.3 percent were changed based on the suggestions of other members. Although other members with various sorts of power can exert a variety of influences, the authority of the president in decision-making is just staggeringly enormous.

While the law states that it shall follow the majority rule and every member has an equal vote in the committee, the reality is that this equality has been overtaken by the entrenched administrative hierarchy. Symbolically, the adjudication committee holds roundtable meetings, a design suggesting that the members are of equal status. But the so-called equality cannot be insulated from the members' unequal administrative status. The unequal administrative status of the members does not vanish in the committee meetings simply because they sit at a roundtable. In reality, every member has his fixed seat, usually with the president sitting directly opposite to the reporting judge. Of course the reporting judge knows to whom he or she is reporting. In other words, the equal status of committee members exists only on the paper of the committee rules.

It is in this context that the above results can be understood. The president, as the political boss in the court, has tremendous control over other judges and officials, from career development to a variety of resources. No other members could afford to forget their administrative rankings in the committee discussion. After all, most members want to remain on good terms with the president in the interest of an earlier promotion, a better position, or simply a more pleasant working environment. At the very least, there is no reason to offend him. Subsequently, even if they disagree with him, it is difficult for them to present their opinions and have a genuine exchange of views. Indeed, a reading of the minutes suggests that the members with lower administrative rankings are always eager to toe the line with the president.

The discussion pattern reflected just one way that the president exercised his control. Other means were also inferred from the minutes and interviews. In a property dispute (hereafter the Property Case), the plaintiff sold her right to buy a work-unit sponsored apartment to her colleague for 10,000 yuan in 2000, which was more or less the market price.Footnote 13 But housing prices had, unexpectedly, tripled over the decade after the transaction. Citing a law forbidding such transactions, the plaintiff sued to invalidate the transaction. Both parties, however, agreed that they had voluntarily engaged in the transaction. By then there were no clear rules on how such a dispute should be decided. Both parties had found connections to the committee members. The plaintiff, working part-time as a lay assessor and obviously well-connected to the court, managed to have the support of the responsible judge and all members of the committee except the president. When the committee reviewed the case, all these members expressed their support for the plaintiff before the president had a chance to utter a word. Under majority rule, the discussion should have ended there. The president, who was connected to the defendant, refuted their position, stating that invalidating such a transaction that was harmless to others and that had been completed a decade earlier was pointless and would have serious negative social consequences. He then suggested consultation with the intermediate level court. That was the committee's final decision. Although his points make sense to me, his ties to the defendant indicated that the president was able to get his corrupt way against all others.

If invoking social consequences against a literal application of law could be regarded as a difference of opinion, seeking instructions from the intermediate court was a polite way for this president to assert control. A prevalent practice in Chinese lower courts to avoid the reversal of their decisions by higher courts' (Reference LiuLiu 2006: 93–94), the frequent use of seeking instructions by this committee during the year had specific connotations. As I was told, this is because this president had worked in the criminal division head of the intermediate court before assuming the presidency in this lower level court. He thus had quite good control over the responses of the intermediate court. When he made such suggestions, it meant not only that this decision should be made cautiously. In a less blunt way, the underlying message was that “I want to take control.”Footnote 14 As shown in the Table 1, the percentage of cases ending up with seeking instructions was not insignificant. This working style, as I was told, differed from that of his successor, the current president, whose background was completely different. With no formal legal training and few connections in the court system, the current president preferred to have more decisions made inside the court. Beneath the two different working styles is the same logic: the president has ways to control the decision-making of the committee.

Outdated laws, different interpretations, inconsistent applications, and vaguely defined social policy all provided the president with vast room to make decisions. This is not to say that he will exercise his power arbitrarily: in most circumstances, he will not and cannot. But the institution does allow him cover his own agendas and concerns in a legitimate mantle. In the Property Case, for example, the decision could have been made for or against the plaintiff. According to the governing laws then, both decisions would not be regarded as incorrectly decided,Footnote 15 and it seems that whoever in power had the final say.

When several members collectively make a decision in a committee, as argued by Gigerenzer, members often face psychological pressures, and moral judgments are based on simple decision rules, such as “do what the majority of your peers do” (2007: 182, 191). Judge Edwards of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals admits that he instills collegiality among the judges in his court and discourages dissenting opinions (Reference Edwards and Drobak2006: 237–38; 2003). I would add that, with the sweeping authority of the president, the fact that many members in the adjudication committee lack time and capability to comment meaningfully on the cases only makes the situation worse. As mentioned, although some members have been adjudicating cases for years, they usually specialize in a single field. In most situations, they are not even familiar with the facts and the subtleties of the issues. For all these members, as the senior officials in the court, busy with multiple duties, to study the case files meticulously beforehand was unrealistic (cf Reference YangYang 2010). As a result, they have to rely on the written and (mostly) oral reports of the adjudicating judges. As long as the stories presented by the reporting judges make sense, they have few reasons not to concur with the proposed decisions of the president. Speaking first or initiating a debate would simply betray their ignorance.

The Reporting Process

When many members have to rely on the oral report, the reporting process may tilt the balance. The decision of the committee, to some extent, is made through the lens of the reporting judges. The judges' own interpretations and tendencies inevitably become part of the basis of the committee's decision. What and how the judges report will then significantly affect the outcome of the case. According to my interviews, most reporting judges prepare diligently before the meeting because they know they are going to be interrogated. Even though they cannot control the discussion and decision-making process, for many reasons they want to defend their suggested positions. Since most of the committee members are the leaders of the court, the reporting judges want to leave a positive impression. They hope to show that they thoroughly study the cases, make meaningful suggestions, and answer the questions professionally. Needless to say, if their suggested opinions are frequently reversed, their professional capabilities might come into question. In other words, the committee process compels the reporting judges to think more of the cases and to speculate on the expected outcome of the powerful members. There seems a rising sense of professional pride especially among the younger generation of judges (cf Reference Balme and PeerenboomBalme 2010).

Despite the efforts made by judges, many communication problems persist. Both my interviews and secondary evidence suggest that some reporting judges might not be able to articulate the issues and facts clearly, especially when the case is complicated. Some important facts might be missing, due to the negligence of the reporting judges. Some emotional but legally irrelevant details may be injected. Since I did not have access to the judgments to the meetings, no comparison between the judgments and the discussed content was made. But as observed by Reference WuWu (2006) and Reference YangYang (2010), even decisions of the committee may not be accurately reflected in the judgments. On the one hand, this should not be surprising, given the fact that no members will bother to look at the minutes. On the other hand, some judges complained that the questions raised by some members, especially those who never hear or adjudicate cases, were less than professional. In the exaggerated words of one interviewed judge: “The only function of reporting is to educate some members.” Another judge who often reports cases said: “I always hope that my case is placed at the end of the sessions. By then the minds of the members are unclear because they have been discussing cases for hours. So they cannot raise many questions on my case and my suggested opinions are more likely to be upheld.”

Some reporting judges, however, have taken advantage of this arrangement to manipulate the outcome (Reference YangYang 2010). According to Wu's interviews with a veteran recorder:

If the reporting judge has a personal goal, he can work on the way of reporting, which would allow him to both accomplish his goal but exempt his responsibility—how he reports the case becomes extremely relevant. For example, if the reporting judge wants heavier criminal punishment for a defendant, he could focus on the pathetic situations of the victim, such as how long the victim was staying in bed, or how bad the defendant carried out himself—to show the poor character of him. In this way, the committee will add the criminal punishment in a very simple tort case … (2006: 198–199)

Of course a well-trained member may not be distracted by the exaggeration of those legally irrelevant points. But as shown, many committee members neither have the incentive to speak their minds nor to study the cases in any depth. The inevitable result, as argued by Reference WuWu (2006), is that the more complicated the cases are, the easier it is for the reporting judges to (mis)guide the committee in making decisions.

The Debates Reconsidered

Legal Consistency

In his influential book Bring the Law to the Countryside, Zhu contends that “the committee has improved or will further improve the quality of average judges in some places” because it compensates for the lack of professional sophistication of many judges by bringing the specialized knowledge and experience of the committee members to bear on difficult cases (2000: 112). Furthermore, the committee contributes to consistency in adjudication within a jurisdiction, a role that may be particularly important in China, where cases are rarely published and legislation is often broadly programmatic (2000).

The data, however, provide little support for these assertions. First of all, it is unclear that the committee makes better decisions than the adjudicating judges. (It is, of course, very difficult to define “better.”) The fact remains that the committee upholds the majority of suggested opinions, in criminal and civil cases alike (54.52 percent and 58.33 percent, respectively, as shown in Table 1). Even for criminal cases, in which the committee modifies many suggested opinions, the changes are only increases in monetary penalties; as to cases suggested for suspended sentencing, most changes involve minor changes such as the duration of probation. The changes imposed by the committee have little to do with the key question—whether the suspended sentencing is appropriate or not.

If the committee is making a better decision, one would expect it to go in both directions, depending on the facts and the law. The tendency to increase the fines in most cases suggests other reasons. As mentioned, other non-legal considerations such as exoneration from corruption or justifications for systematic interference have been in play. It is therefore hard to assert that the committee is making better decisions.

In contrast, one might well argue that since the adjudicating judges have gone through the whole process including hearings, they are in a far better position to pinpoint the exact amount of fines than are the committee members who usually do not have enough time to read the file in advance. One can also argue that adjudicating judges are more cautious in proposing the amount of fines because they know their decisions will be reviewed by the committee and they will have to defend their suggested opinions. But since the committee's decisions are not subject to any further supervision inside the court, the decisions are more likely to be discretionary.Footnote 16

Moreover, despite the generally poor professional quality of this court,Footnote 17 the alleged function of promoting legal consistency is hardly seen. The data suggest that the committee does not or cannot fulfill this duty. First, the committee spends most of its time discussing individual cases. Second, the training and background of the committee members indicate that the committee is not well-equipped for this job. The heads of the adjudicative divisions are experienced adjudicators, but may not necessarily be the best in the court, because there is no guarantee that the best adjudicators are appointed as the division heads. Some of them, after becoming division heads, may not remain abreast with the latest laws and cases. In addition, some presidents and the disciplinary inspector may not have any adjudicative experience at all. More specifically, among the eleven members of the committee, only four continued adjudicating cases as regular judges. It is difficult for the committee to set good examples for other judges when the majority of its members neither hear nor adjudicate cases. Finally, the decisions of the committee, as shown in the data, are not much better than the ones suggested by the adjudicating judges. The discussion, if any, rarely has anything to do with the legality of the disputes or the application of the laws, but mostly with the severity of the punishment or the appropriateness of a given solution in terms of its social and political effects. Seeking instructions from the intermediate court or communicating with the local government and the Party is frequent, but legal debates are hardly seen, the president makes most of the final decisions. If the discussion may play some educational role, it is the reporting judges who educate those members who have little adjudication experience or have not closely followed the legal development. Even when there are some laudable decisions, there are no institutional mechanisms to disseminate the experiences. The minutes are created solely for the purpose of record: nobody would check them once the file is closed. For the last two decades, not a single document has been issued by the committee in promoting judicial craft.Footnote 18

On the other hand, the committee's responsibility dilution function has significant impact on the judges' behavior. Once the committee has reviewed the case, the potential responsibility for the adjudicating judges for making a wrongful decision is significantly reduced; sometimes it disappears. Consequently, the committee has become a haven for the avoidance of responsibility. As observed by Reference WuWu (2006: 196), when asked when a case will be submitted for review, many judges responded that they do so when they need to share the responsibility for it. As mentioned, even if the committee upholds the suggested opinion of the adjudicating judges and that decision is later proven to have been wrong, the responsibility of the adjudicating judges will be minimized because it has become the committee's decision. A shared and thus reduced responsibility in the collective decision-making process certainly gives judges an incentive not to decide difficult cases by themselves (Reference Balme and PeerenboomBalme 2010: 156). Furthermore, when the litigation loser faces the bureaucratic and faceless adjudication committee, which seems both hard to oppose and more communally based, conflicts would be dampened or lumped. As a result, whenever adjudicating judges encounter cases that they cannot think through, they simply ask the committee to review them, instead of making efforts in applying the laws and locating a good solution. Contrary to the intended function of improving the judicial skills of the adjudicating judges, the existence of the committee has discouraged judges from improving themselves, or at least discouraged them from taking responsibility.

Judicial Independence

While the Constitution of China (Art. 126) and Organic Law of the Courts (Art. 4) stipulate that the courts exercise the adjudicative power without being interfered by any individuals and institutions, both de facto and de jure it is legitimate that under the Chinese political structure the Party has a role in significant and difficult cases (Reference HeHe 2012a). Since it does not specify what the significant and difficult cases are, the real questions are in what types of cases that the party and the court have interacted and what role the adjudication committee has to play in the interaction. More specifically, is the committee in a better position to resist external influences?

A reading of the minutes indicates that in many cases the committee went out of its way to cater to the government and the Party. As a legal requirement, a court approval is needed before the government can conduct compulsory enforcement on housing demolition. In discussing such a request by the local government, the president said: “The compulsory enforcement is granted; prepare the decision, but wait for further instructions from the district Party Committee before delivering to the parties.” An interviewed judge explained that “this is to see if the Party Committee has a different opinion over the issue.” Together with many requests to the intermediate court for instructions, all these indicate that the president simply tried to avoid responsibility, and simultaneously maintained a good relationship with, if not made effort to please, the local government and the Party.

On the other hand, among all the reviewed cases, not a single one indicates that the committee had attempted to resist external pressures. Since the committee, as a collective decision-making body, can be used to dilute responsibility, one may reasonably raise the question why the resistance against external influences is not found. In other words, if no one would bear responsibility for whatever decisions made, why do not some members stand up for the law? The reason may lie in the decision-making structure. Since the president is almost the sole decision-maker in the committee, it does not carry much weight in using the committee to resist external pressures. Other political elites could simply call the president, knowing that he can get things done. While one might argue whether to resist the pressure would hinge on the personal style of the president, the truth is that the president has little incentive not to cooperate. As an experienced bureaucrat, every president, having been appointed to that position, must be an expert in scratching the backs of the local political elite. Indeed, when there are illegitimate pressures, the president can simply use the committee as a legitimate cover for illegitimate decisions, as evidenced by the Property Case and the Contract Case. Under these circumstances, the committee has become a convenient option for the president to justify such decisions. As aptly put by Reference LiuLiu (2006: 94), “[i]t is through the internal power structure within the court that external influences are capable to control the outcome of cases.”

Even if the committee may resist some external interference, the role of the committee in this regard remains minor because many, and more illegitimate influences often circumvent the formal institutions to work through informal channels. As Reference SelznickSelznick (1966) argues, unlike formal ones, informal influences have real power and control over the decision-making process. Reference LiuLiu's (2006) ethnographic work also suggests that in Chinese courts, informal influence on the decision-making process based on the administrative ranking system undermines the due process of law much more severely than the formal adjudication committee does.

In line with these points, my observations suggest that the committee, as a formal institution, has been sidelined in many cases facing external influence. When political elites make calls, they usually contact the top court leaders who have discretion as to whether or not to place the cases in question on the agenda of the committee. In many circumstances, as I was told, the adjudicating judges are simply asked to follow the instructions of the court leaders, when they are under intense pressure. A judge with twenty years of working experience in the court said:

The most outrageous situation that I have encountered involved local protectionism, where I was asked by the court leaders to release the assets of a local enterprise already frozen by the court, upon the request of a Shanghai petitioner in an enforcement case. Such behavior was outright illicit, but the president, vice president in charge of our division, and the division head had all signed the release order and I had to follow suit.

When asked why the issue had not been reviewed by the committee, the judge replied: “Those illicit requests are not appropriate for formal discussion.”

Although the party's interference in these cases may not be problematic under China's political and legal structure, the Party's reasons for interfering and the court's incentives to seek opinions are usually opportunistic. The adjudication committee, however, turns out to be an instrument, when needed, in facilitating such opportunistic considerations.

How about internal independence, which means judges' ability to decide cases without interference from senior court officials (Reference Peerenboom and PeerenboomPeerenboom 2010: 77)? Reference WooWoo (1999) suggests that supervision is the main way to limit judges' discretion and the adjudication committee is an institutional check on individual judges and it reflects the Chinese concept of judicial independence as the “independence of the court as an organic whole” (Reference WooWoo 1991). Indeed, the control inside the court itself may not be a drawback for judicial independence at all. Reference Ginsburg and PeerenboomGinsburg (2010) even argues that China shall strengthen this aspect, learning from the experience of Japan. The key question, however, is whether the control of the judges through the committee is efficient or fair, two stated goals of the judiciary. From the data and analysis, the committee is not at all efficient, if it means to handle the cases quickly without unnecessary delay. As to criminal cases, almost all the cases are reviewed by the committee and the decisions of a significant proportion of cases are changed. More cosmetic than substantial, these changes are not equal to decisions with better quality. As for the more difficult and complicated civil cases that are reviewed by the committee, the committee is not capable of providing better solutions. Comparing the decisions of the committee with those made by adjudicating judges, appeal rates or remand rates of the committee decisions are often higher (Reference WuWu 2006; Reference YangYang 2010).Footnote 19 The review of the committee, by and large, only adds another level of bureaucracy by depriving the adjudicating judges of their decision-making authority.

Nor is the internal control through the committee fair. While the minutes do not provide direct evidence, the reporting process potentially allows for numerous miscommunications between the adjudicating judges and the committee. Facts might be twisted or missed, legally irrelevant points exaggerated, and the process manipulated. Without participating in the hearing, the committee members rule on cases with which they themselves are not familiar. The litigation parties have no ideas about who makes the decisions affecting their property and freedom. That is also why throughout the last two decades, not a single member in this court has ever been asked to recuse himself.Footnote 20 The existence of the committee has completely destroyed the recusal institution (回避制度).

Judicial Corruption

While Zhu Suli maintains that it is more difficult to bribe nine members of the committee (2000: 112), He Weifang argues that the amount of corruption is a function of the quality of the decision-makers and the institutional environment, not of the number of decision-makers (1998). To what extent can the data be used to assess the debate? In other words, is the committee in a better position to limit judicial corruption than the adjudicating judges or the collegial panel are? Not a single trace of corruption can be inferred from the minutes. After all, no member would be so thoughtless as to leave written evidence of corruption. But the decision-making structure does hint at an answer. If the members of the committee have equal status and the process is relatively transparent, the answer might be yes. But the data show that the reality is far from this assumption. There are more people on the committee than on a collegial panel, but fewer actual decision-makers. Power is highly disproportionate among the members. When the president makes more than 90 percent of the modified decisions and does not hesitate to speak first, one only needs to work on him, as shown in the property case. For ordinary criminal cases, the adjudicating judge, the director of the criminal division, and the (vice) president in charge of the division are the key. Once all these persons reach a consensus, there is little that the other members can say. A ten-member decision-making body therefore, does not necessarily raise the threshold of corruption or of external interference. As an interviewed judge commented: “Judging the level of corruption based on the number of people is just laughable.”

At the same time, this secretive process can easily be corrupted. Without effective supervision, the key members of the committee can inject their prejudice into the decisions. Even a reporting judge may guide or mislead the committee into making the desired decision. Other types of connections also permeate the committee: the lay assessor in the Property Case, who contacted most of the committee members in advance in the property case, is only the tip of an iceberg. Also in that case, the president, connected to the defendant, eventually prevailed against all other members. In such an institutional arrangement, what outcome would one expect in the litigation between an average citizen and a powerful one? (cf Reference He and SuHe and Su 2013 forthcoming).

The data on suspended sentencing provide further evidence on the limited role of the committee in controlling corruption. An area highly vulnerable to judicial corruption, a suspended sentence must be reviewed by the committee. Several interviewed judges admitted that corruption ran rampant in this area: prices are set for reduced and suspended sentences. But the data indicate that the committee has done very little to limit the applications of the suspended sentencing—it changed less than 4 percent of the suggested opinions.

In a way, the committee has become a safety device to protect the adjudicating judges and the committee members from being accused of corruption. When a case is reviewed by the committee, the decision becomes the committee's. The adjudicating judge significantly lowers the possibility of being punished for corruption since it is no longer her decision. For the committee members, a collective decision absolves everyone of responsibility. The insignificant changes, often by adding more monetary penalties, are well within the discretion of the law: there is no way to show which decisions are being bought or paid for. Reviewing most criminal cases simply means that the committee has participated in both the decision-making process and more importantly, in sharing the opportunities of bribery-taking. That is why the internal documents requiring almost all the criminal cases be reviewed have been well-implemented. That is also why “criminal judges are always busy with banquets,” as a saying goes, and why many judges prefer to work in the criminal division.Footnote 21

Black Hole of Responsibility

The tasks for the adjudication committee, as stipulated, are to summarize adjudicative experiences, adjudicate significant and difficult cases, and discuss other adjudication related issues. The data and analyses above, however, indicate that the court is far from realizing these goals. While it does review significant and difficult civil cases, it offers adjudicating judges with little help. For criminal cases, the reviewing scope is overwhelmingly enlarged, and the committee thus does not at all focus on difficult and significant cases. Nor does it summarize or disseminate adjudicating experiences.

What emerges from these operational patterns is a theme that the committee makes it possible for all sides to avoid assuming actual responsibility for decisions. Not only can the adjudicating judge whose case is reviewed avoid responsibility, but so can the committee, since the decision is supposed to be collective. Specifically, judges hearing civil cases will submit the most difficult and tricky ones to the committee and thus dilute its responsibility. In criminal cases, adjudicating judges do not have much choice on whether or not to submit for view, but being reviewed by the committee is not inconsistent with their interest. Once the cases have been reviewed, their potential risk of being caught in corruption and of awarding incorrectly decided cases disappears. It is equally safe for the committee members. Since neither voting nor signature is required, they can safely and easily inject their legal and extra-legal views with no consequences. This is not untrue for the president: he makes decisions for the majority of reviewed cases, but all in the name of the committee. For truly significant cases that may lead to social consequences and thus may hold the president responsible, he simply suggests the committee to seek instructions from upper-level courts or to communicate with the local government. In other words, the committee, by and large, creates a black hole of responsibility.

When the committee becomes a device for avoiding responsibility, its intended functions in promoting adjudicating skills, enhancing judicial independence, and controlling judicial corruption are all crippled. With regard to promoting adjudicating skill, the presence of the committee discourages the reporting judges from applying themselves on difficult cases. Whenever there is external interference on the key leaders of the court, as occurred in the Contract Case, they absorb it with the committee. It also adversely affects internal judicial independence, since the adjudicating judges are eager to submit difficult civil cases to the committee; while in criminal cases, the committee simply imposes its decisions on the adjudicating judges. Similarly, judicial corruption finds a convenient channel in the committee. In civil cases such as the Property Case, both parties try to leverage their connections to influence the committee. In criminal cases, all of the unlawful exchanges between a reduced penalty and money lose trace with the decisions being reviewed by the committee. Expanding its reviewing scope, the committee members share with adjudicating judges the decision-making powers and potential benefits in engaging the unlawful transactions. Taking advantage of the responsibility avoidance characteristic of the committee, the reporting judges could manipulate the committee to make a skewed decision.

All of these phenomena beg a question: Why does nobody, including both the rank and file judges and court officials, seem to be willing to bear the responsibility for decisions? This may have to be understood in terms of the authoritarian nature of the Chinese government. To reap the regime-supporting benefits of the courts, the regime must allow the courts to enjoy certain power and autonomy. During the reform period, Chinese courts have been assigned an increasingly important role in social control, legitimation, and providing a credible investment environment, as evidenced by the increased caseloads and expanded jurisdictions (Reference Peerenboom and HePeerenboom and He 2009). At the same time, the Chinese government, like most other authoritarian regimes, has been cautious in loosening its control over the courts and judges. To check or regulate the exercise of power, liberal democratic countries may simply hold the judges accountable for the law or to the public. But authoritarian regimes, including China's, want to hold them accountable not just for the law or the public, but also for the political leaders or the regime's ultimate interests (Reference Ginsburg and MoustafaGinsburg and Moustafa 2008; Reference ShapiroShapiro 1981: 32; Reference SolomonSolomon 2007: 123).

Starting in the early 1990s and continuing into the twenty-first century, the Chinese courts have been subjected to greater scrutiny. Specifically, the responsibility systems (目标责任制) that evaluate and discipline court cadres and judges with quantified measurements have been launched. The performance of the courts and judges will be significantly discounted if litigants file a successful complaint against them. When social stability becomes a serious concern for the ruling party and government, for example, anything that might lead to a mass social movement will be severely punished. If a “vicious incident,” usually referring to sit-ins, public demonstrations, or unnatural death, results from some court behavior, it may ruin the political career of the court directors, regardless of the merits of the courts' behavior (Reference MinznerMinzner 2009; Reference Su and HeSu and He 2010). In some cases, court decisions are even subject to the media's scrutiny (Reference LiebmanLiebman 2005). In addition to the general requirements specified in the Judges Law (Amended 2001, Articles 32–35), more detailed regulations, such as measures for holding adjudicating staff responsible for incorrectly decided cases (错案追究制) (SPC 1999), have been issued by courts across the country, with sanctions including monetary fines and negative notations in a judge's career file (Reference HeHe 2009a).

In this context, it is only natural that judges and court officials try to avoid responsibility in making decisions. Reference MinznerMinzner (2009) points out that a consequence of the responsibility systems is the widespread practice of advisory requests: lower-level court judges solicit the views of higher courts and judges regarding how to decide pending cases. This article further suggests that the adjudication committee, with its collective decision-making mechanism, serves the judges' needs in dealing with all these pressures. That is why the fact that “the litigants are emotional,” which is legally irrelevant, becomes a basis for submitting a civil case to the committee for review (Reference YangYang 2010). It is also why in the Divorce Case, the reporting judge and the committee tacitly rejected the divorce application, even though the emotional relationship of the couple had obviously ruptured. The black hole of responsibility in the adjudication committee is also helpful in accommodating the unlawful demands and extra-legal interferences, making it easier for the judges to gain personal benefits or deal with the local political reality, as shown in the Contract Case. In a sense, the original functions of the adjudication committee have made room for the avoidance of responsibility. As a result, these functions have been eroded at the least and subverted at the worst.

Conclusions

Relying primarily on the minutes of the adjudication committee in a basic level court in a poor province of one year, this study does not aspire to meet the highest standards of objectivity. While the types of cases reviewed, the average discussion time for each case, the percentage of suggested opinions being modified, the sequence of discussion, and who make the final decisions are just a matter of fact, the judges being interviewed might overgeneralize on the basis of their own experiences. Accounts from these varying sources may not always be consistent. Despite the variation in these approaches, some fundamental themes emerged from these sources: the disproportionate power among committee members, miscommunication between the committee and adjudicating judges, bureaucratized decision-making process, violation of due process of law, and more fundamentally, its role as a protective device to avoid responsibility.

In addition to illustrating the operational pattern of the most important decision-making body in the Chinese court, this study has demonstrated that institutional evolution is important in understanding judicial politics. The literature has never lost sight of the institutional arrangements and incentives in the courts (Reference Ginsburg and MoustafaGinsburg and Moustafa 2008; Reference HilbinkHilbink 2007; Reference ShapiroShapiro 1981; Reference SolomonSolomon 2007), but their focus has always been whether the judges and courts are capable of increasing their authority or independence under given institutional factors. The story of the adjudication committee nonetheless shows that the courts and judges are adaptive and innovative, but not necessarily in pursuit of greater autonomy or authority. Pressured to be accountable to their political leaders, the law, and the public, the judges have transformed the adjudication committee into a shelter to avoid responsibility, carving room for their survival and interest. The decision-making of the court is thus being shaped by the judges' adaptive capacities and also by how the judges make use of the legal institutions. The adaptive and innovative capabilities of China's courts and judges indicate that the relationship between the regime and the judges is far more complicated than previously imagined. The contextual factors that contribute to such a relationship and its implications to the functioning of the judiciary deserve special attention.

This dynamic shall help explain why the regime's reform efforts, including those combating judicial corruption and improving adjudicating skills, have been difficult. Indeed, the study highlights an institutional dilemma of the judiciary in authoritarian regimes: uncomfortable with an empowered judiciary, the regime set stricter criteria for the assessment of judges' performance. At the same time, the story of the adjudication committee demonstrates that this is a tough job. The judges and the court officials have been able to diffuse the pressures and even subvert the requirements through the committee.

One reason why the adjudication committee in this Shaanxi court reviews so many cases is that the court leaders are less resourceful, partially because of relative economic underdevelopment of the region. The court leaders are still capable of controlling the decision-making of all these cases. Their relatively lower income also gives them a greater incentive to control and thus they are less willing to delegate authority to individual judges (Reference HeHe 2011; Reference He2012b). Reports from some areas already suggest that the committees may review significantly fewer cases (Reference GuanGuan 2004: 27; Reference YangYang 2010), either as a result of the efforts toward judicial transparency or because the heavy caseloads preclude a comprehensive review. Many courts have followed the directives of the SPC in decentralizing the power of the adjudication committee, setting up specialized subcommittees, incorporating committee members from veteran judges, and streamlining discussion rules (SPC 2005; 2010). Further research thus should focus on whether these reforms will change the operation pattern and decision-making process of the committee, and especially the role in responsibility avoidance.Footnote 22 Only when more empirical data and studies become available, can these questions be satisfactorily answered.