Seasonal tides cast up mud-covered clay pipes on the banks of the Thames as a matter of course, just as heavy ploughs on East Anglian fields turn up these objects, lost for generations. Licensed mudlarks and country walkers are thrilled with their finds, British things that confirm a long-standing passion for tobacco and the everyday fitment that enabled its enjoyment. Archaeologists are also rewarded by clay pipes from centuries past.Footnote 1 Such encounters inspire attention to the materiality of things. The Museum of London and other institutions hold countless of these artifacts, the detritus of industry, trade, consumption, and sociability. These objects are also offshoots of early globalization and evidence of Native American tobacco culture adapted in new climes.

The clay pipe is a “British thing” distinct to its time, but that is only a partial provenance. Although thousands of them are unearthed in Britain or described in British archival records, these small relics are also evidence of early globalized trade, imperial ventures, and material translation across cultures; their Britishness is contingent. They accompanied complex enterprises in which a new-style masculinity arose, new racial categories were framed, and a new sociability took root. Tobacco and the clay tobacco-pipe industry are entwined with globalizing practices beginning with Europeans’ encounters with the leaf after the 1490s. Marcy Norton explains the profound Indigenous American knowledge at the heart of tobacco culture and its subsequent cross-cultural spread. Newcomers to the Americas became convinced of the benefits of this herb and learned the manner of ingesting it, an education over generations that accompanied diplomacy and trade, evangelizing and sociable pleasures. Britons played a part in this passage and looked to profit from it. Harbors, riverfronts, and forest clearings became performative settings where learning occurred and was later carried back to Britain. Pipes were soon a mainstay among merchants, missionaries, and mariners, populations with networks worldwide.Footnote 2

Figure 1 Clay tobacco pipes, London, England, 1580–1590. Science Museum, London. CC-BY.

English ships made about three hundred sorties to the Caribbean between 1550 and 1624, involving about twenty-five thousand sailors and nine hundred ships. Looting was soon as commonplace as trade in these environs, with tobacco a preferred commodity.Footnote 3 Mariners suffered many deprivations on long journeys, and tobacco eased hunger at sea; when on shore, they typically binged, and tobacco offered another means of relaxation. The habit readily translated to new contexts, and the tobacco pipe came in time to characterize maritime men. Sailors’ rowdy conviviality and martial exploits signaled the growth of a new-style of plebeian masculinity embedded in British imperial pursuits. Ballads praised mariners’ exploits, and eighteenth-century print media marked their rhetorical rise with tobacco pipes at hand.Footnote 4

Clay pipes added a new material idiom to daily life.Footnote 5 “Tobacco taking” became fully embedded in plebeian recreation over the 1600s, a pleasure at London's St. Bartholomew's Fair, a new fashion for “young country gallants” visiting the capital, and essential in soldiers’ entertainment.Footnote 6 In 1678, a London magistrate castigated women who “have the impudence to smoke Tobacco, and gussle in All [ale] houses”Footnote 7—the two practices now virtually synonymous.

Figure 2 A sharp contrast is made between the manliness of the smoking sailor and the imputed effeminism of this macaroni. James Aldwell (1739–1819). 772.07.25.01.0. Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

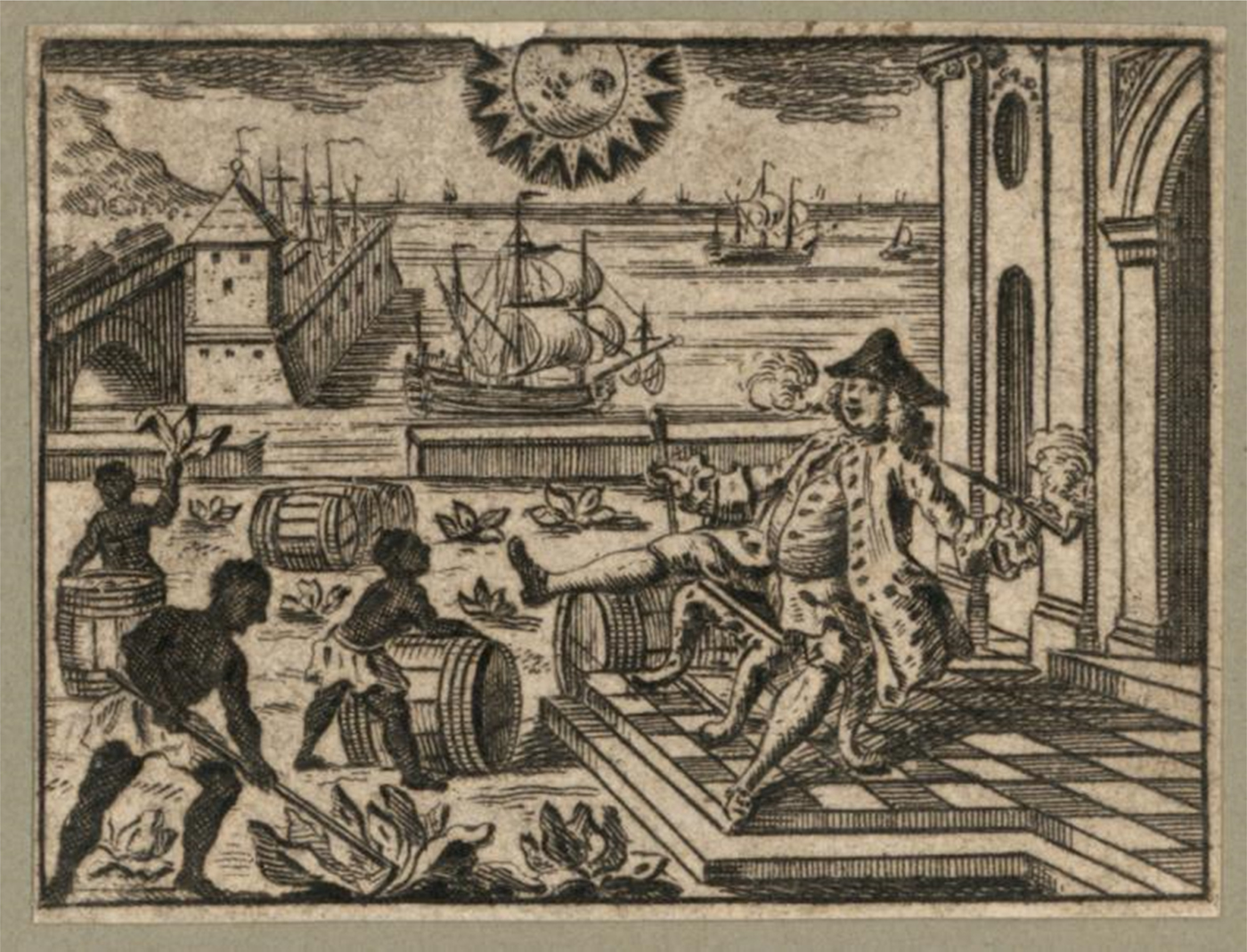

The appetite for tobacco stoked the production of leaf and pipe. The spread of the crop relied on the systematic dispossession of Native Americans and the importation of labor from Africa; a Virginia official championed the Chesapeake slave system in 1683, stating that the “low price of Tobacco requires it should bee made as cheap as possible, and the Blacks can make it cheaper than Whites.”Footnote 8 Both themes were visualized in media from tobacco jars to trade cards, bill heads to tobacco wrappers. Trade cards were especially important as mobile primers, “more central to pre-nineteenth century advertising than were newspapers and newssheets.”Footnote 9 Buyers were instructed through common visual scenarios that equated pleasurable consumption with the dispossession of American indigenes and the enslavement of Africans. A hierarchy of peoples was being normalized, developing into the racial stereotypes that followed. Cheap clay pipes marked this pattern.

Pipe making, “imitating Mexican pipes,” sprang up around the ports of Boston and London about 1600.Footnote 10 Yarmouth, Chester, Hull, Edinburgh, Newcastle, and Gateshead followed suit. Englishmen spread the trade to the Netherlands, where it also flourished.Footnote 11 Pipe makers are recorded in eighteenth-century directories, with those at dockside best placed to serve a growing market.Footnote 12 The twenty thousand English pipes unearthed in Port Royal, Jamaica, speak to the importance of smoking for both enslaved and free.Footnote 13 Jamaica was the site of early tobacco cultivation before the Chesapeake burgeoned. From the outset, tobacco smoke served in the management of slaves, “because they say that when they [slaves] stop working and take tobacco their fatigue leaves them.”Footnote 14 On long sea voyages, tobacco and tobacco pipes were essential supplies, offering solace to intransigent human cargo and assisting in the function of trade.Footnote 15 Pipes aided in the consumption of the fifty million pounds of tobacco legally landed in English ports about 1750, reaching one hundred million pounds annually by 1770. Much of this stock was dispersed to other markets, though the British taste for tobacco remained firm, served by both legal and illegal suppliers.Footnote 16

Figure 3 Tobacco dealer's trade card, eighteenth century. George Arents Collection, New York City Public Library Digital Collections, accessed 27 June 2018, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/b3af248f-3cc5-7070-e040-e00a180638c0.

Those barrels of tobacco have long since been smoked and the embers extinguished. The bodily knowledge of pipes—the feel of the warm pipe bowl and the physical management of this tool—once routine to our ancestors is equally transient. But if these elements have passed, their effects survive in the economic and political systems set in place, including the forced movement of people and the reshaping of land. The clay pipes lying under our feet or washed up by the tides denote the extraordinary changes that shaped Britain in the early global era, evidence we can hold in our hands.