Food allergies are an adverse immunological reaction arising from exposure to a specific food protein antigen (i.e. food allergen)(Reference Yu, Freeland and Nadeau1). In Europe and the United States, the estimated prevalence of food allergies is approximately 8 % of children and 2 % of adults(Reference Sicherer and Sampson2). In developing countries, and especially in Middle East Arabian countries, there remains a lack of information regarding the prevalence rates and incidence of food allergy and other food hypersensitivities(Reference Loh and Tang3,Reference Leung, Wong and Tang4) . Many studies in Saudi Arabia have estimated an increasing prevalence of food allergies and reported the severity of certain food allergens(Reference Gadelrab5,Reference Kwaasi, Parhar and Al-Sedairy6,Reference Tayeb, Koshak and Qutub7) . A study in Jeddah by Aba-Alkhail and El-Gamal with 1341 asthmatic patients estimated that the prevalence rate of clinical sensitivity to food was 29 %(Reference Aba-Alkhail and El-Gamal8). Furthermore, a cross-sectional study in two emergency departments revealed that food was the most common trigger of anaphylaxis (39 %) compared with insects (38·5 %), drugs (17·4 %) and environmental factors (5·0 %) and that the prevalence of food allergies was higher among paediatric patients relative to adults(Reference Alkanhal, Alhoshan and Aldakhil9).

Once an allergic individual comes into contact with a specific allergen, a cluster of related symptoms may appear, ranging from mild symptoms, such as rashes, to more severe symptoms, such as vomiting, diarrhoea, breathing difficulties and, in extreme cases, anaphylaxis(Reference Sharma, Bansil and Uygungil10). Food-induced anaphylactic shock is the most life-threatening systemic symptom, as it is rapid in onset, occurring within seconds or minutes of exposure, and may cause death if not treated immediately(Reference Sampson, Muñoz-Furlong and Campbell11). As there is no medical treatment for eliminating food allergies, prevention of an allergic reaction is solely dependent on eliminating the food allergen from the individual’s diet(Reference Moore, Stewart and deShazo12). Adherence to an allergen-free diet can be a difficult task, as it requires knowledgably reading food labels to avoid the specified allergen and identify any hidden sources. Another important issue is related to the lack or insufficiency of information about allergen ingredients in prepacked food. A considerable proportion of accidental allergen consumption happens when eating outside the home. It has been found that 21–31 % of accidental consumption occurs when eating in restaurants and 13–23 % occurs in other eating-out settings, such as workplace or school canteens(Reference Versluis, Knulst and Kruizinga13). Consuming an allergen outside the home accounted for 32·2 % of anaphylaxis-related hospital admissions(Reference Beyer, Eckermann and Hompes14) and has been implicated in 50 % of allergen-caused deaths(Reference Pumphrey and Gowland15). Food-allergen avoidance impacts individuals’ well-being and quality of life, as well as placing significant restrictions on social and behavioural outcomes(Reference Muraro, Dubois and DunnGalvin16,Reference Barnett, Vasileiou, Jaspal and Breakwell17) . Therefore, an effective food-labelling system for allergen ingredients is important for protecting the health of consumers with food allergy. This system should also include effective food-allergen labelling regulations for non-prepacked products.

In October 2019, the Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) introduced new legislation (No. SFDA.FD/56) requiring that food establishments providing and selling non-prepacked foods provide allergen information on any of the major fourteen specified allergenic foods and their protein derivatives: milk, soya, mustard, lupin, eggs, fish, crustaceans, peanuts, tree nuts, molluscs, cereals containing gluten, celery, sesame seeds and sulphur dioxide and sulphites at concentrations of more than 10 mg/kg or 10 mg/l(18). This legislation applies to restaurants, food trucks, bakeries and cafés. Moreover, food-allergen labelling on menus is required to be provided in a clear, written form in Arabic(19). Additionally, the new legislation requires precautionary allergen labelling (PAL)/advisory labelling, such as ‘may contain’ or “manufactured in a facility that contains’’ or similar phrases to indicate that a product may contain allergens caused by possible cross-contamination(20).

This legislation is aligned with European Union legislation (EU Food Information for Consumer Regulation No. 1169/2011, (EU FIC)) issued in December 2014, mandating the labelling of these fourteen specified food allergens used as ingredients in non-prepacked food items sold by food businesses(18). Many studies in the UK have examined the effect of EU FIC legislation. For example, a study examining the effect of allergen-labelling legislation on the behaviour and attitudes of consumers with food allergy towards eating out reported that this legislation has improved delivery of information regarding food allergens and increased awareness of food allergies in restaurants and diners. In addition, the current study revealed that consumers with food allergy prefer written forms of allergen labelling and verbal communication with staff for confirmation of labelled allergens(Reference Begen, Barnett and Payne21). Another study revealed that, following the EU FIC legislation, consumers were moderately satisfied with the allergen-labelling information made available in food establishments(Reference Barnett, Begen and Gowland22).

As the declaration of allergens on the menus of food establishments in Saudi Arabia is newly implemented, to our knowledge, there have been no studies conducted to assess the views of consumers with food allergy towards the new SFDA legislation. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to assess the allergen-labelling knowledge, practices, preferences and perceptions towards the new SFDA allergen-labelling legislation among consumers with food allergy in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Study design

The current study utilised an observational cross-sectional approach, conducted between February and March, 2020. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Participants and recruitment

The current study includes 427 participants (convenience sample). The target population consisted of adults (18 years and older) with food allergies, residing in Saudi Arabia. Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire created using Google forms and distributed using the snowball sampling method through emails and social media platforms such as Twitter and WhatsApp. E-mails were used to share the link to the questionnaire with multiple faculty members. For WhatsApp, medical professionals, including allergists, gastroenterologists and registered dietitians working at allergy clinics, were requested to share the link to the questionnaire with their patients or clients. In addition, the link was also shared with all contacts in the contact lists of the authors, and they were encouraged to share the link with others. On Twitter, we requested public figures and influencers with a high number of followers in Saudi Arabia to re-tweet the link to the questionnaire. In addition, the food allergy advocacy groups in different regions of Saudi Arabia were contacted and encouraged to share the questionnaire with their group members. Collected data were entered and stored electronically, and the identities of participants remained anonymous throughout the study.

Sample-size calculation

As there were no Saudi studies similar enough to be used as a reference, we calculated the sample size of participants using data obtained from the SFDA concerning the prevalence of wheat allergy in Saudi Arabia. According to SFDA, 500 000 people suffer from wheat allergy in Saudi Arabia(Reference Aljoaid23). Therefore, using the online Epi Info sample-size calculator supported by the Division of Health Informatics & Surveillance, and Centre for Surveillances, Epidemiology & laboratory services, the required sample was found to be n 384, at a statistical power of 95 %, error margin of 5 % and design effect of 1.

Study questionnaire

A five-section questionnaire was constructed by combining questions from previously published and validated surveys(Reference Zurzolo, Koplin and Mathai24–Reference Marra, Harvard and Grubisic26). In addition, some questions were modified to suit the target population, and some were added to assess perceptions of the new SFDA allergen-labelling legislation. The questionnaire was translated from English to Arabic using the Brislin back-translation method(Reference Brislin27,Reference Cha, Kim and Erlen28) to suit the target population. For pilot testing, a field study with six participants (who were excluded from the actual study) was conducted to ensure clarity and suitability of wording. The questionnaire was also reviewed by three independent experts with experience in the food-allergy field, and questions were modified accordingly. In addition, consent and confidentiality statements were included at the beginning of the questionnaire.

The first section of the questionnaire covered the participants’ characteristics (seventeen questions)(Reference Marchisotto, Harada and Kamdar25). This included questions on socio-demographic characteristics, prevalence of self-reported food allergy, number of family members with a food allergy, type and symptoms of the food allergy, time of diagnosis, previous counselling regarding food-allergen labelling and the potential sources of information.

The second section assessed the knowledge of food-allergen labelling legislation (four questions)(Reference Marchisotto, Harada and Kamdar25). This included knowledge-assessment questions regarding prepacked food-allergen labelling legislation in Saudi Arabia with ‘yes,’ ‘no’ or ‘not sure’ options.

The third section assessed the purchasing practices based on food-allergen labelling (four questions)(Reference Zurzolo, Koplin and Mathai24–Reference Marchisotto, Harada and Kamdar25). This included questions about participants’ practices in purchasing prepacked products based on food-allergen labelling. Questions included the frequency at which prepacked products would be purchased depending on the precautionary phrasing used on the label; participants used a three-point Likert scale with the options ‘never,’ ‘sometimes’ and ‘always’ for various precautionary phrases (e.g. ‘Contains Allergen,’ ‘May Contain Allergen’ and ‘Manufactured in a Facility that Also Processes Allergen’).

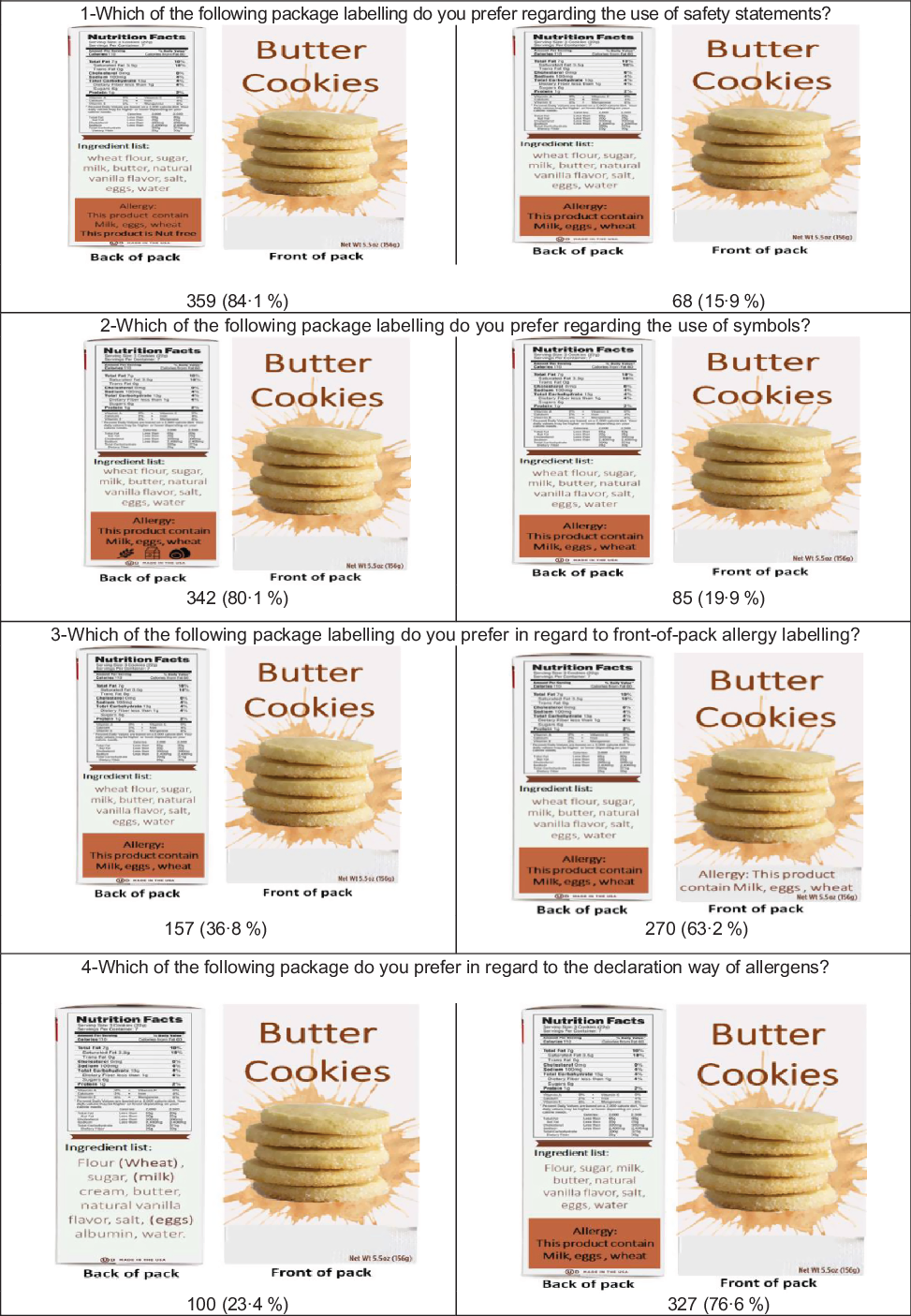

The fourth section assessed the preferences of consumers with food allergy regarding food allergen labelling (four questions)(Reference Marra, Harvard and Grubisic26). This included pictures of different types of product packaging in order to evaluate consumer preferences through questions related to the use of safety statements, symbols and the placement of information on prepacked food products.

The fifth section evaluate the perception of the consumers with food allergy towards the new SFDA allergen-labelling legislation (ten questions). This developed questions included whether they noticed the presence of the allergen information on menus, whether they prefer a separate menu for allergen information and whether they are satisfied with the allergen information in restaurants. Additionally, a question asking participants’ comments was included. The validity of the perception questionnaire was determined in two steps. First, the questionnaire was evaluated by three independent experts in the field of food allergy, one of them being a nutritional epidemiologist with expertise in biostatistics. Second, the questionnaire was pilot tested by six individuals diagnosed with food allergies. The results from the pilot test (excluded from the final test) revealed that the questions were well-constructed with clear wording.

For knowledge questions, a score of ‘1’ was assigned to correct answers, whereas a score of ‘0’ was assigned to incorrect or unsure answers. For practice and perception, responses to questions were scored so that higher scores corresponded to increasingly favourable practices and perceptions. Total scores were computed and tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test.

Statistical analysis

Data entry and statistical analysis were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 25. Descriptive statistics were completed using frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Since the total knowledge, practice and perception scores were abnormally distributed, non-parametric statistical tests were utilised. The Mann–Whitney U test was used when comparing two groups, and the Kruskal–Wallis H test was used when comparing more than two groups. P-values ≤0·05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 427 responses were received. Table 1 summarises the socio-demographic characteristics of participants. The age of 41·2 % of participants ranged between 18 and 24 years. Most (78·5 %) were female, and the majority (92·5 %) were Saudi nationals. Approximately two-thirds (67·7 %) were university graduates. Only 9·6 % were certified as health practitioners. Nearly a third (32·3 %) had no income, whereas 11·5 % had an income exceeding 20 000 SR/month.

Table 1 Socio-demographic characteristics of participants (n 427)

Table 2 shows the participants’ background. Only 8·6 % of participants lived with more than three household adults (≥18 years old) with food allergies, whereas 40·6 % lived with no household adults with food allergies. More than half of participants (53 %) had no household children (<18 years old) with food allergies, whereas only 1·8 % had more than three children with food allergies. The most commonly reported food allergens were cereal containing gluten (26·9 %), eggs (25·3 %), milk products containing lactose (22·7 %), tree nuts (22·5 %), peanuts (19·7 %) and fish (18·0 %). Less than half of participants (48 %) had been clinically diagnosed. A history of receiving educational material/advice relating to reading food labels at the time of diagnosis was reported by 36·1 %. The duration since food allergy diagnosis was 10 years or more among 30·4 % of the participants. The majority (75·9 %) had an experience with an allergic reaction to food, whereas 46·4 % reported an experience with a severe allergic reaction to food. Only 16·9 % have had serious, non-fatal incidents of food anaphylactic shock while eating out. The most commonly reported source of information regarding the proper reading of food-allergen labels was the internet (52·2 %), followed by social media (23·4 %) and healthcare professionals (19·7 %).

Table 2 Background of participants (n 427)

* Mango, banana, strawberry, chocolate, kiwi, hot pepper.

Knowledge of food-allergen labelling legislation

As shown in Table 3, only 28·1 % of participants knew that there were governmental regulations in Saudi Arabia regarding food-allergen labelling and 47·1 % knew that food allergen labelling regulations in Saudi Arabia require the declaration of allergens in the ingredient list. Almost half of participants (51·3 %) and (50·1 %) knew that advisory labelling is not required by law and that PAL/advisory labelling is not based on specific amounts of the allergen present in the foods, respectively.

Table 3 Food-allergen-labelling legislation knowledge

Purchasing practices

As shown in Table 4, approximately two-thirds (67 %) of participants check labels on prepacked food products for allergens. Among these participants, 40·2 % did this every time they bought a product. The majority (80·1 %) checked both ingredients and the PAL/advisory statement. More than half of the participants indicated that they would always purchase a product if the food label was free of allergens (53·4 %) or allergen-free (52·2 %), whereas more than half of them would never purchase a product if the food label indicated that the product contained allergens (50·1 %) was manufactured on the same equipment as products containing allergens (53·6 %), or was manufactured on shared equipment with products containing allergens (51·1 %).

Table 4 Purchasing practices based on food-allergen labelling

Food-allergen labelling preferences

The majority of participants (84·1 %) preferred food products that contained a safety statement. Most (80·1 %) preferred products that contained pictures. Nearly two-thirds of participants (63·2 %) preferred a labelling format with information on both the front and back of the product. Also, most (76·6 %) preferred mentioning the allergen as a statement underneath the product ingredients (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The preferences of food-allergic consumers regarding food allergen labelling (n, %)

Perception of the new Saudi Food and Drug Authority food-allergen-labelling legislation and participant comments

As shown in Table 5, only 26·2 % of participants were aware of the new allergen legislation stating that restaurants should provide information regarding the top fourteen allergens contained in their food by labelling these ingredients on menus or menu boards. Among those that were aware, 58·9 %, 50·9 %, 73·2 % and 39·3 % noticed the presence of allergen information on the menu, were more comfortable eating out, were more comfortable asking food servers about allergen ingredients and thought that food items produced at homes and marketed on social media were required to declare food allergens on labels, respectively.

Table 5 Responses of participants regarding perception of new Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) food-allergen-labelling legislation

Almost one-third of the participants (37·2 %) reported visiting a restaurant or ordering a takeaway food once a week, whereas only (5·6 %) did not do that. The majority of participants (81·7 %) preferred a separate allergen menu. Most (60·6 %) were more likely to eat at chain restaurants that reported the allergen information of each of their food items on menus. The majority of participants (94·4 %) were supportive of the new SFDA legislation requiring restaurants to provide allergen information on menus or menu boards for each food item at the point of purchase. More than half (56 %) were dissatisfied with the availability and adequacy of allergen information at restaurants.

The most prominent comments that we received from the participants are shown in Table 6. These comments could be used to improve food labelling regulations as well as to improve the operation of restaurants.

Table 6 Participant comments

Association of participant characteristics with their knowledge, practices and perceptions relating to food-allergen labelling legislation

As shown in Table 7, female participants and those who had their food allergies diagnosed within the last 1–3 years had significantly higher knowledge were more likely to follow the recommended practices and have favourable perceptions of food-allergen labelling, compared with other groups (both P < 0·05). Participants aged between 25 and 34 years had a significantly higher knowledge of food-allergen labelling legislation compared with other age groups, and the group with the lowest level of knowledge consisted of adults aged 55 years or above (P < 0·01). In addition, non-Saudis showed a significantly higher rate of following the recommended practices compared with Saudis (P < 0·05). Certified healthcare practitioners and participants who had received educational material/advice relating to reading food labels at the time of diagnosis had significantly higher knowledge and more favourable perceptions of food-allergen labelling legislation compared with uneducated groups (both P < 0·05). Moreover, clinically diagnosed participants and participants whose source of information about food labelling was social media had a significantly more favourable perception of food-allergen labelling compared with other groups (both P < 0·05).

Table 7 Association of participant characteristics with their knowledge, practices and perceptions relating to food-allergen labelling legislation

IQR, inter-quartile range; SFDA, Saudi Food and Drug Authority.

* Kruskal–Wallis test.

** Mann–Whitney test.

Discussion

This is the first study to provide insight into the knowledge, practices and preferences of consumers with food allergy related to food-allergen labelling legislation in Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, this is the first study to examine the perceptions of consumers with food allergy towards food-allergen-labelling legislation recently enacted by the SFDA. Therefore, the current study will provide a foundation for future research in this field.

Importantly, the current study has shown that the most commonly reported food allergens among individuals with food allergy were cereals containing gluten, such as wheat, oats and barley; eggs; milk products containing lactose; tree nuts, such as almonds, hazelnuts, walnuts, cashews, pecans, brazil nuts; and peanuts. These allergens are some of the most common food allergens in adults, as mentioned by NIAID(Reference Boyce and Assa’ad29). In agreement with our finding, a study in Riyadh of 100 asthmatic patients examining the frequency of sensitisation to inhalant and food allergens revealed that the most noticeable reaction, as indicated by the presence of specific IgE antibodies, was to peanut allergen, affecting 11 % of patients(Reference Gadelrab5). Moreover, a retrospective study conducted in Makkah with eighty patients with food allergy evaluated the presence of specific IgE antibodies to common food allergens revealed that the top five food allergens were cocoa (22, 27·5 %), peanuts (14, 17·5 %), egg white (12, 15 %), milk (10, 12·5 %) and strawberry (9, 11·3 %)(Reference Tayeb, Koshak and Qutub7). Recently, a cross-sectional study surveyed 1260 adult Saudi participants with food allergy and found that the most commonly reported allergenic food were eggs (22·0 %), fish (13·8 %) and fruits (20·5 %)(Reference Rasha, Husam and Jihan30). The only means of preventing food allergies is to completely avoid consumption of all food products containing the allergen. Current application of new legislation in Saudi Arabia promises to provide increased protection to consumers with food allergy.

Our results showed that most of participants lacked knowledge about the presence of governmental regulations in Saudi Arabia regarding food-allergen labelling. Moreover, approximately half of participants had noticed the declaration of food allergens in ingredient lists and recognised that PAL is not required by law. Our results indicate the need for increased awareness of allergen-labelling regulations in Saudi Arabia, as sufficient knowledge and awareness of food-allergen labelling is important for the health of consumers with food allergy. Other studies examining the knowledge and perspectives of schoolteachers relating to food allergies in Saudi Arabia have revealed that most schoolteachers in Jizan(Reference Gohal31) and Al-Qassim(Reference Alsuhaibani, Alharbi and Alonazy32) have little knowledge of food allergies and their potential effects on the learning process. In contrast, high food-allergy awareness was reported among parents with allergic children(Reference Alanazi, Aalsubaie and Aalkhozym33). A higher level of knowledge and better purchasing practices were notable among female and non-Saudi participants, as well as those who had been diagnosed with food allergies for at least a year or more. Most studies that have measured the prevalence of food allergies in regions, such as in the United States and New England, have found that the prevalence of food allergies is higher among females, and that females are more susceptible to food allergies than males(Reference Acker, Plasek and Blumenthal34–Reference Verrill, Bruns and Luccioli36). This difference in prevalence likely explains why females were generally more knowledgeable of food-allergy labelling legislation, in addition to the fact that our study population sampled a higher percentage of females. Moreover, the culture of Saudi Arabia often requires females to be the ones primarily responsible for procuring food for the family; thus, their improved purchasing practices and enhanced knowledge of food labels may stem from this cultural norm. This pattern was also observed in a recent study in a culture where females were considered the main caregivers(Reference Swinkels, Tilburg and Verbakel37). The experience gained by allergic individuals after several years of being diagnosed with food allergies made them more knowledgeable and improved their purchasing practices as they became more cautious and read food labels, especially if they had been exposed to a previous allergic reaction or received any advice or educational materials from physicians or dietitians. Additionally, clinically diagnosed participants had greater knowledge than self-reporting participants. This could be related to the fact that the former group received medical advice or printed educational materials at the time of diagnosis. The small number of non-Saudis (7·5 %) may explain why they were more consistently informed compared with Saudis, as the probability of finding variation in such a small sample size is small. In addition, food allergies have not received much attention until recently in Saudi Arabia compared with other countries, which may explain why non-Saudis were more consistently informed. Younger allergic individuals (aged between 25 and 34 years) also had higher levels of knowledge, as they are generally more engaged with social media; it is easier for this population to access relevant information.

Our findings revealed that purchasing practices were affected by the wording of PAL statements, and a wide variety of these statements increase buyer confusion. Similar findings were observed in a previous study assessing consumer understanding and purchasing practices among adults with food allergy and caregivers in the United States and Canada, revealing that 40 % or fewer purchase food with PAL(Reference Marchisotto, Harada and Kamdar25). This confusion can be addressed by standardising PAL statements among factories in Saudi Arabia.

In our study, most participants preferred food-allergen labels that contained a safety statement and symbols on both sides of the package (front and back) that was provided separately from the ingredient list. This finding was similar to that of a study conducted in Canada with 1100 consumers with food allergy, which found that the most important factor in the efficacy of food-allergen labelling was the use of symbols (43·5 %). Safety statements (26·4 %) and the placement of information (18·9 %) were comparatively less important(Reference Marra, Harvard and Grubisic26). The difference in our results may stem from the different methods that were used to assess labelling preferences. In the Canadian study, a discrete choice experiment questionnaire design was used that required participants to choose between food products with different combinations of safety statements, precautionary labelling, use of symbols, and placement of information. The importance of attribute presence on the food product was then determined based on participants’ choices. As the SFDA has not released the specific criteria or standards for allergen-labelling systems, such as the positioning of allergen information on food labels, the specification of allergen sources, and the font used to denote allergens in the ingredient list (19), we recommend that specific criteria be used for allergen labelling based on the preferences of consumers with food allergies to reduce the risk of food allergen exposure.

Only 26·2 % of study participants were aware of the implemented legislation. Among those who were aware, 58·9 % noticed the presence of allergen information on food menus, while just over half (56 %) reported being dissatisfied with the allergen information provided when eating out. The fact that the legislation has been recently implemented, as well as the reported insufficiency of allergen information available in food establishments, may have contributed to the low level of awareness among participants. Additionally, differences in the level of satisfaction between participants in the current study may stem from the type of food allergens avoided. This pattern has also been reported in another study(Reference Barnett, Begen and Gowland22), in which variation in satisfaction between participants was influenced by the food ingredients avoided, such as gluten, nuts, or milk. Moreover, according to a longitudinal study in the UK, most participants noticed improvements in the level of food-allergen information provided but, at the same time, expressed that there was a need for further progress to be made(Reference Begen, Barnett and Payne21). This pattern may be explained by the fact that post-legislation data were collected for a longer period following the EU FIC implementation compared with the period during which data were collected in our study. However, in the current study, 50·9 % and 73·2 % of those aware of the implemented legislation reported being more comfortable eating out and asking restaurant staff about allergen ingredients, respectively. This change in comfort level may reflect the enhanced consumer rights that they felt when eating out, given that all food establishments must now disclose food-allergen information. This change may also be attributed to the increased awareness of food allergies among food handlers in different food establishments. Moreover, our findings were consistent with a study in the UK following the implementation of EU FIC legislation, indicating that participants with food allergy and intolerant participants were more comfortable eating out and asking restaurant staff about allergens in food(Reference Begen, Barnett and Payne21).

In general, perceptions of participants in our study highlight the need for improvement in allergen declarations made by food establishments. Potential approaches include the use of a separate allergen menu and the incorporation of food-allergen information on menus for each food item at the point of purchase, as these approaches were favoured by most participants in our study.

Several limitations of the current study require consideration. First, most study participants were young and educated. This could be attributed to the fact that approximately 53·6 % of the Saudi population above 25 years of age has a degree in higher education(38). Second, research data were self-reported, and such data are often biased. Moreover, the higher percentage of self-diagnosed food allergies among the study population may have led to the overreporting of food allergies. Third, this is the first study to assess the perceptions about the newly implemented legislation among consumers with food allergies, and there are no previous studies on the prevalence of food allergies in Saudi Arabia, these data cannot be generalised to the population with allergies and future studies are necessary to address this limitation. In addition, although the majority of the survey questions in the current study were used and published by other validated studies(Reference Zurzolo, Koplin and Mathai24,Reference Marchisotto, Harada and Kamdar25,Reference Marra, Harvard and Grubisic26) ; some questions were added by the authors of this work. Therefore, future research should test the validity and reliability of this questionnaire, including calculation of the Cronbach α coefficient. Furthermore, the questionnaire was administered online, which excluded potential participants who did not have internet access.

Conclusion

Most participants had sufficient knowledge of food allergen labelling legislation, especially women and young adults. Although most participants supported the new legislation, there was a clear gap in knowledge of the new SFDA legislation in Saudi Arabia, indicating that the passing of this new legislation needs to be more broadly disseminated so that allergic individuals are better informed. PAL was one of the major factors affecting the purchasing practices of participants, as a high degree of variation in PAL led to increased confusion during the purchasing of products, highlighting the need to standardise PAL among food factories. The results of the current study also provide information on the preferences of participants regarding food labelling and restaurant menus, which can be used to improve the way allergens are presented on both food labels and menus. The findings from the current study could be applied in future studies to explore the perceptions about the legislation among consumers with food allergies.

Representative randomised samples should be obtained in future studies examining the knowledge, preferences and perceptions relating to food-allergen labelling among consumers with food allergy. Additionally, we encourage more longitudinal studies to measure the long-term impacts of the newly implemented legislation. Finally, a nationwide survey is needed to measure the prevalence of food allergies in Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank all our participants for their time and contribution in the current study. Financial support: This research received no external funding. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. Authorship: Conceptualisation, W.T.A., L.A.; methodology, W.T.A., L.A., Afnan.A.A., Athear.A.A., D.A.A., N.A.A., S.A.A. and A.M.A.; data collection, W.T.A., L.A., Afnan.A.A., Athear.A.A., D.A.A., N.A.A., S.A.A. and A.M.A.; data entry and analysis, W.T.A., L.A., Afnan.A.A., Athear.A.A., D.A.A., N.A.A., S.A.A. and A.M.A.; writing-original draft preparation, W.T.A., L.A., Afnan.A.A, Athear.A.A., D.A.A., N.A.A., S.A.A. and A.M.A.; writing – review and editing, W.T.A. and L.A.; supervision, W.T.A. and L.A.; project administration W.T.A. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Unit of the Biomedical Ethics Research Committee at King Abdulaziz University (Jeddah, Saudi Arabia) (reference no. 77-20). An electronic written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.