Introduction

The mass media is one of many institutions that contribute to shaping stereotypical representations of older people, while also serving to consolidate social constructions of old age (Iversen and Wilinska, Reference Iversen and Wilinska2020). It has been suggested that the mass media may even be the dominant constructor and diffuser of age stereotypes, through presenting, duplicating and circulating representations of older people (Rozanova et al., Reference Rozanova, Northcott and McDaniel2006; Vidovićová and Honelová, Reference Vidovićová and Honelová2018). Media portrayals of older people have remained one of the core research themes in the developing field of media and ageing (Barton and Schreiber, Reference Barton and Schreiber1978); hence, the existing body of research examining representations of older people in mass media is abundant. However, the extensive range of social media has attracted limited research endeavours on how older people and later life are represented, from social networking sites to microblogs, photograph- or video-sharing networks, social news and discussion forums, to mention but a few.

Previous studies examining social media representations of older people have presented seemingly contradictory results concerning the role of social media in reinforcing or destabilising stereotypes of older people. For example, according to Oró-Piqueras and Marques (Reference Oró-Piqueras and Marques2017), YouTube videos under the labels of ‘old age’, ‘older age’ and ‘senior citizens’ produce a counter-stereotypical representation of older people and accordingly destabilise old-age stereotypes. Likewise, another study suggested that older adult bloggers advocate various and individualised viewpoints about old age and thereby challenge stereotypical notions (Lazar et al., Reference Lazar, Diaz, Brewer, Kim and Piper2017). On the other hand, Levy et al. (Reference Levy, Chung, Bedford and Navrazhina2014) considered Facebook to be a site for negative age stereotypes, finding that the descriptions of Facebook groups focusing on older individuals significantly excoriated older people. Similarly, Makita et al. (Reference Makita, Mas-Bleda, Stuart and Thelwall2021) argued that Twitter appears to be a platform for reproducing and strengthening discourses about older people as a disempowered, vulnerable and homogeneous group. These studies are important for focusing on the individual contributions to constructing social media representations of older people. However, prior research has not dealt with the social media depictions of older people produced by organisations or social institutions (e.g. businesses, the authorities), which engage in social media to a steadily increasing extent.

Recently, local authorities in many countries have started to use social media to establish connections with citizens and external stakeholders, as well as to strengthen transparency, accountability and citizens’ trust (Bonsón et al., Reference Bonsón, Torres, Royo and Flores2012, Reference Bonsón, Royo and Ratkai2015; Feeney and Welch, Reference Feeney and Welch2016). Through their use of social media, local authorities have worked on promoting the accessibility of information and e-services and achieving greater interaction with citizens. Additionally, they are expected to publish informative content on social media and to include materials from their own websites (Bonsón et al., Reference Bonsón, Torres, Royo and Flores2012). Given that the Nordic countries are at the cutting edge of digitalisation in the European context (Randall and Berlina, Reference Randall and Berlina2019), there is evidence suggesting that local authorities in these countries are becoming particularly active in their use of social media. For instance, Swedish local authorities have taken up social media (i.e. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Flickr) at a steady pace and are substantively performing online activities (Larsson, Reference Larsson2013). In this study, the use of social media by Swedish local authorities serves as a research context for advancing our knowledge about media representations of older people and the role of local authorities in reinforcing and challenging stereotypes of older people.

Because local authorities are bound by specific institutional regulations and rules, their responsibility for the social media representation of older people is distinctively different from those of other content producers. Swedish municipalities were given the mandate to develop social media regulations under national legislation and to perform social media activities that clearly conform to these regulations (Klang and Nolin, Reference Klang and Nolin2011). Since the passage of the Discrimination Act (2008:567) in Sweden, municipalities and joint local authorities have been obliged to abide by anti-discrimination legislation, which aims to combat discrimination and promote equal opportunities regardless of age, disability, ethnicity or other social characteristics in various work domains, including institutional communication. As a consequence, local authorities have the potential to impact upon the ways in which older people are represented on social media, given the tactics they have developed for reaching out to and engaging with citizens.

Studying older people together with other age groups and making comparisons between and within age groups allows researchers to develop theoretical arguments that are relevant to the entire lifecourse and can enhance our understanding of the ageing process (Närvänen, Reference Närvänen, Öberg, Närvänen, Näsman and Olsson2004). Thus, the present study examined social media representations of older people constructed by local authorities and compared them to other age groups. This was accomplished through an analysis of 1,000 Facebook posts published by 33 Swedish local authorities. In this study, local authorities refer to the organisations responsible for the provision of public amenities, facilities and services in a particular area, including schools, museums, libraries, recreation centres, and so forth. This study made use of a collection of Facebook posts to analyse the signs, activities and contexts assigned to older people, in relation to ten well-defined aspects, aiming to shed light on the ways in which older people are visually portrayed in the photos compared to other age groups. The questions that this study aims to answers are:

• What social media representations of older people can be identified?

• What signs, activities and contexts are associated with older people compared with other age groups?

Previous studies

Media representations of older people

Most European societies exhibit a gradually ageing demographic, which we can expect to be reflected in the media through increasing visibility given to older people, as the media simultaneously reflect and construct societal changes (Amaral et al., Reference Amaral, Santos, Daniel, Filipe, Zhou and Salvendy2019). In this way, the salience of certain issues (e.g. successful ageing) in the media may act to perpetuate and normalise certain assumptions. It has been found that older people have been commonly underrepresented in the media across different societies (Hiemstra et al., Reference Hiemstra, Goodman, Middlemiss, Vosco and Ziegler1983; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Miller, McKibbin and Pettys1999; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Carpenter and Meyers2007; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Schwender and Bowen2010; Prieler et al., Reference Prieler, Kohlbacher, Hagiwara and Arima2015). Other studies have expressed great concern about the exclusion of certain groups of older adults from the mass media, such as older women (Simcock and Lynn, Reference Simcock and Lynn2006; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Harwood, Williams, Ylänne-McEwen, Wadleigh and Thimm2006; Edström, Reference Edström2018), ethnic minority older people (Roy and Harwood, Reference Roy and Harwood1997), those in certain occupations (Signorielli, Reference Signorielli2004) and the oldest members of society (Bonnesen and Burgess, Reference Bonnesen and Burgess2004; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Leyell and Mazachek2004). Previous studies, however, have not examined media representations of older people in comparison to representations of other age groups. This study is based on a conception of old age as an advanced lifecourse phase and compares the Facebook poses of older people to those of younger age groups.

There is a sizeable body of work in support of the argument that older adults have been portrayed in an over-simplified and over-generalised manner according to the frequency of stereotypical representations. Loos and Ivan (Reference Loos, Ivan, Ayalon and Tesch-Römer2018) found that, since the 1990s, visual media representations of older people in the advertising and television industries on both sides of the Atlantic have been shifting towards depictions that are more favourable. This has led to media representations of older people who may be considered successful, whether in terms of physical and mental health status (Robinson and Callister, Reference Robinson and Callister2008), or in social engagement and economic status (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Rakoczy and Staudinger2004). With a focus on the gender-related patterns seen in stereotypes of older people, Clarke et al. (Reference Clarke, Bennett and Liu2014) found that older men were represented in magazines as being influential celebrities or healthy and happy people. Additionally, Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Ylänne and Wadleigh2007) found that older women were featured in advertising campaigns as being the perfect grandparents.

Given that the producers of media content have become adaptive to local cultural norms in order to communicate their messages effectively (Raman et al., Reference Raman, Harwood, Weis, Anderson and Miller2008), local content producers and audiences can be seen as active contributors to producing particular media portrayals of older people. Ylänne (Reference Ylänne, Twigg and Martin2015) argued that it is important to take into account the contexts in which older people are represented, since impersonal agents help to define the conceptions of old age in varying ways. To date, previous studies focusing on the Swedish mass media have primarily discussed the representation of older people in the context of social care provision and distribution. For example, Lundgren and Ljuslinder (Reference Lundgren and Ljuslinder2011) found that Swedish news media depicted the country's ageing population within the discourse of political economy and constructed it as a threat to the welfare system. Similarly, Agren (Reference Agren2017) argued that the news media used political-economic discourses to amplify deficiencies in elder-care within the welfare state, with a focus on newspaper articles detailing loneliness among older people. These studies reveal the relevance of local authorities as organisers of social welfare for examining media representations of older people.

Stereotypes of older people in the media and the ideology of ageing

Previous research analysing media content about older people identified a variety of categories of media representation, which are largely in alignment with the stereotypes of older people (Hummert et al., Reference Hummert, Garstka, Shaner and Strahm1994) held by all members of society. So, for instance, magazine advertisements have been examined to develop and validate a typology of media representations of older people, resulting in some descriptive types of portrayal that correspond to multiple stereotypes of older people (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Miller, McKibbin and Pettys1999; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Wadleigh and Ylänne2010a, Reference Williams, Ylänne, Wadleigh and Chen2010b; Ylänne, Reference Ylänne, Twigg and Martin2015). Specifically, the major advertising representations of older people characterising them as the ‘golden ager’, the ‘perfect grandparent’, the ‘mentor’, the ‘coper’, the ‘celebrity endorser’ and the ‘comedian’ promoted the image of ‘successful ageing’ that was associated with positive traits among older people, such as being happy, active, wise and family-oriented; conversely, other advertisements represented older people as ‘despondent’, ‘reclusive’, ‘severely impaired’ or ‘shrewish/curmudgeonly’, which echo negative traits of frailty, dependency and incompetence.

When society is considered as a repository of knowledge, these widely held stereotypes are socio-cultural and group-level phenomena that can be (re-)produced and conveyed in the mass media (Stangor and Schaller, Reference Stangor, Schaller and Stangor2000). Research examining media content about older people can thus offer socio-cultural insights into the construction and maintenance of stereotypes of older people. Two strands of analysis of stereotyped content featuring older people can be seen in prior studies. On the one hand, there is the Stereotype Content Model proposed by Fiske et al. (Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002), which has been adopted to analyse media content about older people along the dimensions of warmth and competence (Lepianka, Reference Lepianka2015; Kroon et al., Reference Kroon, Van Selm, Ter Hoeven and Vliegenthart2018). On the other hand, several studies have used content analysis techniques to document the frequency of media representations of older people conveying messages about what are considered to be stereotypical thoughts and roles for older persons (Loos and Ivan, Reference Loos, Ivan, Ayalon and Tesch-Römer2018). This paper is intended to contribute to this burgeoning area of scholarship on stereotypical media representations of older people.

van Dijk (Reference van Dijk and Wodak1989) argued that the media play an important role in the reproduction of ideologies, as they (re-)interpret, (re-)construct and (re-)present opinions. Repeated stereotypical representations have ideological effects on justifying and promoting the interests of particular social groups, given that those in a dominant social position have the power to establish and popularise their own understandings and thus make these seem natural (Gorham, Reference Gorham1999). There have been extensive discussions within the literature on the political economy of ageing about the ideology of ageing, which serves to establish and perpetuate understandings of the devaluation, marginalisation and oppression of older people in economic, social and cultural terms (Salter and Salter, Reference Salter and Salter2018). This ideology rests on a recognition of individuals as inevitably experiencing a decline towards death during the latter phases of the lifecourse (Higgs and Gilleard, Reference Higgs and Gilleard2020). This ideology is potentially undergirded by, and results in, stereotypical media representations of older people. In answering the question of who benefits from this decline ideology, Salter and Salter (Reference Salter and Salter2018) argued that a network consisting of the pharmaceutical industry, the medical profession and the state worked on the legitimation of advantageous benefits and relational power in the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States of America (USA), because they profit from increasing drug consumption by people of advanced years. Social understandings of ageing in favour of these beneficiaries can be partially constructed, propagated and sustained by stereotyped content about older people, e.g. those representing older people as frail and in need of social care.

Researchers have presumed that greater exposure to particular media content has an impact on people, modifying age-appropriate beliefs, attitudes and behaviours towards older people (Prieler et al., Reference Prieler, Ivanov and Hagiwara2017). Donlon et al. (Reference Donlon, Ashman and Levy2005) proved that greater television exposure predicted more negative images of ageing among older individuals. Additionally, Mastro (Reference Mastro, Nabi and Oliver2009) argued that media exposure contributes to forming stereotypes of social groups at the individual level, given mass media's role in socialisation and priming. The recurring media depictions of older people increases the likelihood of audiences encountering them. This highlights the importance of studies examining the presence of specific messages and the extent to which these messages appear in the media.

Analytical aspects of documenting visual portrayals of older people

Gorham (Reference Gorham1999) argued that stereotypical media representations link social-level myths with individual-level cognition and suggested an interpretive framework for analysing media texts in descriptive and evaluative manners. This study draws attention to the signs in media texts which function as myth-consistent cues for perceivers who are cognitively processing the information about social groups. Documenting and translating the frequency of occurrence of certain signs in media texts is considered a technique for identifying stereotypical media portrayals and signified stereotypes. Since stereotypes of older people (e.g. vulnerability) are shaped contextually, concretely and spatially (Krekula, Reference Krekula2010), the present study contextualises these signs on the basis of previous research examining visual images of older people.

A variety of analytical aspects have been defined and focused on in previous studies examining media depictions of older people. Researchers in this field have performed the analysis of these aspects both in single-case studies of specific media coverage and in cross-cultural comparative analyses of representations of older people. Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Harwood, Williams, Ylänne-McEwen, Wadleigh and Thimm2006) reviewed previous analyses of media portrayals of older adults and defined several analytical aspects when examining advertisements, including the presence of older adults, role prominence, traits or characteristics, social contexts and physical settings, thematic analysis and products. Similarly, Chen (Reference Chen2015) defined four aspects for analysing representations of older people in advertising: the degree of presence, role prominence, product association and social context. The present study established an assemblage of ten analytical aspects for assessing visual content about age groups by drawing upon six aspects mentioned in previous studies and suggesting four additional analytical aspects.

Degree of presence

Degree of presence is frequently used as an analytical concept in quantitative content analysis to investigate the frequency of appearances by older people. Chronological age has been employed as a constructor to divide people into age groups. For instance, 50+, 55+ and 60+ were used as age cut-offs to refer to the older population (Hiemstra et al., Reference Hiemstra, Goodman, Middlemiss, Vosco and Ziegler1983; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Carpenter and Meyers2007). It should be noted that this approach overlooks social and cultural constructions of old age, which this study seeks to address by considering old age to be a life phase and acknowledging that the social meanings of old age are developed in relation to other life phases. In this regard, Presence of Age Groups is used to identify the visibility of different age groups and to investigate the contextual features associated with each group. The scheme of this concept consists of five lifestage groups (infants, children, adolescents, adults and older adults).

Role

In order to pursue an in-depth analysis of the presence of older people, previous studies have examined the roles in which older people have been cast from a visual perspective (Atkins et al., Reference Atkins, Jenkins and Perkins1990; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Carpenter and Meyers2007; Prieler et al., Reference Prieler, Kohlbacher, Hagiwara and Arima2015); for instance, older people may appear in the background or in minor roles. Considering that there is little available research analysing social roles, this study investigates the social roles that older people perform in specific settings. As argued by Wallander (Reference Wallander2013), people may take on multiple roles, with an emphasis on the increasing lack of attention paid by dominant roles to minor roles. This study focuses on the aspects of Roles in Activity and Roles in Context to identify the social roles assigned to people at different lifestages in two settings.

Setting and social integration

Setting is a commonly used concept for describing the physical places where older people appear. Roy and Harwood (Reference Roy and Harwood1997) designed a scheme for this concept, consisting of ‘being pictured at home’, ‘outdoors’, ‘in a business’, ‘in a hospital’ and ‘others’. While this approach has proved effective, the present study suggests specifying recognisable settings to improve the validity of this concept. Additionally, social integration has proven effective for characterising the multigenerational setting of older people presented in visual images (Roy and Harwood, Reference Roy and Harwood1997; Prieler et al., Reference Prieler, Kohlbacher, Hagiwara and Arima2015). This study deepens the level of analysis in this regard by including Physical Settings, Multiple Age Groups and Other People in the assemblage for analysing the representation of age groups.

Products and services

This concept has often been used in previous studies to describe commercial goods shown in advertising representations of older people (B Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kim and Han2006; Simcock and Lynn, Reference Simcock and Lynn2006; MM Lee et al., Reference Lee, Carpenter and Meyers2007; Prieler et al., Reference Prieler, Kohlbacher, Hagiwara and Arima2015). For instance, advertising representations of older people were associated with certain recurring commercial products, such as daily necessities, financial insurance, medications, and so forth. When it comes to broader analyses of media representations of older people (not only in advertising), the present study suggests a more inclusive concept of Objects to also include more mundane items that may assign value to social groups. For example, objects such as walking aids serve to generate the representation of older people being weak, frail and infirm (Lepianka, Reference Lepianka2015).

Stereotypes and traits

Drawing upon the stereotypes of older people identified by Hummert et al. (Reference Hummert, Garstka, Shaner and Strahm1994), Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Miller, McKibbin and Pettys1999) invited three judges to evaluate whether the portrayals of older people in magazine advertisements resonated with specific stereotypes. Considering that the activity of participants captured in the photos can be used as a vital sign for interpreting what stereotype(s) the activity of older people connotes, the present study sets forth the concept of Activity to describe and understand the depicted activities in which older people take part.

Themes

Among the examples of a thematic analysis of visual representations of older people, Williams et al. (Reference Williams, Wadleigh and Ylänne2010a) developed a thematic typology of older people consisting of: the ‘golden ager’, ‘perfect grandparents’, ‘gravitas’, ‘comedic’, ‘celebrity endorsers’ and others; additionally, Clarke et al. (Reference Clarke, Bennett and Liu2014) recognised six themes covering the range of portrayals of older men in magazines: wealthy, politically influential, civically engaged, physically active, sexually engaged and healthy. Despite the value of this research, few of these studies have been able to draw upon the contextual themes associated with local authority services. The present study uses Themes to highlight the specific context in which older people were depicted.

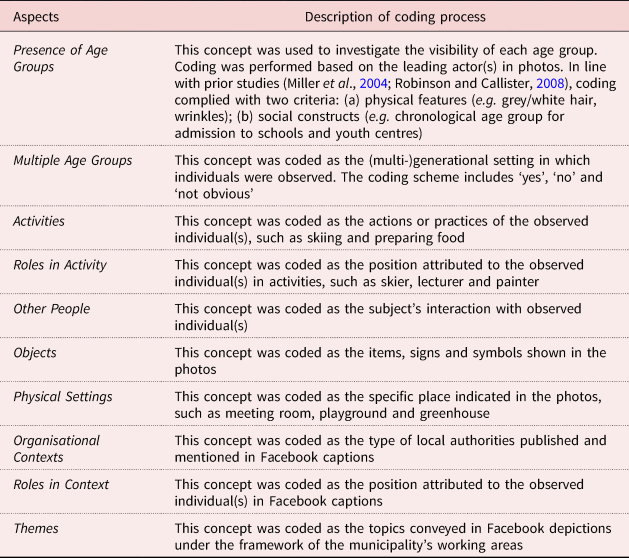

In summary, this study established an assemblage of ten analytical aspects for content analysis, consisting of: Presence of Age Groups, Multiple Age Groups, Other People, Activities, Roles in Activity, Objects, Physical Settings, Organisational Contexts, Roles in Context and Themes.

Materials and method

Swedish municipalities and joint local authorities have increasingly used social media tools as a prominent method of institutional communication. This study focuses on the Facebook posts published by local authorities in the municipality of Norrköping, which is one of the largest municipalities in Sweden, with a population of about 143,000 inhabitants in 2019. The administration of this municipality is relatively advanced in social media management and visual language use. It attaches importance to the use of visual images and the representation of lifestage groups on social media (Xu, Reference Xu2019). Consequently, this municipality appears to be a suitable research context for examining social media depictions of older people produced by local authorities.

Swedish local authorities are responsible for providing public services in a particular area, such as education, museums, library, youth work, elder-care, support for people with disabilities, health care and environmental issues. In this respect, older people are represented as care recipients, local authority workers and activity participants on authority-managed social media. Given that Facebook is the most frequently used platform among municipalities (Larsson, Reference Larsson2013), the present analysis includes all the Facebook pages managed by the local authorities in the municipality of Norrköping.

Materials

This study used Facebook posts produced by local authorities in 2018, with a data-set of 1,000 posts established using the following criteria:

(1) Duration: This study extracted Facebook posts published in 2018. As a special case, it excluded 101 photos from the Facebook album Cultural Night 2017, although these photos were posted in 2018. The Cultural Night in Norrköping is a significant annual event and it is expected that photos will be published on Facebook by the event organisers. This study aims to evaluate the annual media performance of local authorities during a normalised one-year period; hence, the 2017 album was considered an overdue media release and was therefore excluded from the data-set.

(2) Human figures: In terms of the presence of human figures, several types of photos were identified, including portraits, group shots and body parts pictures.

(3) Compositional posts: A set of photos of the same scene taken from multiple perspectives allows viewers to appreciate the spatial configuration of the occasion. Thus, this study assembled these photos into one compositional post for the analysis, because viewers often cognitively perceive them as one post through the visual sense.

(4) Ruled-out images: Blurred photos, duplicates and infographics were ruled out due to the coding process being unfeasible. Additionally, movie scenes and posters were excluded, as this study focuses on the citizens of Norrköping.

Method

Bell (Reference Bell, Van Leeuwen and Jewitt2001) showed that visual content analysis is a systematic observational method for investigating the ways in which people are represented in the media; additionally, it allows researchers to describe media representations in terms of well-defined aspects. Hence, this study analysed the visual content of 1,000 posts through coding and interpretation to identify the recurring signs, contexts and activities assigned to each age group, as well as the symbols visualising age stereotypes. The unit of analysis consists of a Facebook photo and its caption. As described in the previous section, the assemblage of analytical aspects was used for content analysis by coding the available information embedded in the Facebook posts. Specifically, the analyst coded the photos in relation to seven aspects (Presence of Age Groups, Multiple Age Groups, Other People, Activities, Roles in Activity, Objects, Physical Settings) and the captions in relation to three aspects (Organisational Contexts, Roles in Context, Themes). A coding scheme was created and developed to guide coder decision-making during the content analysis (as shown in Table 1). The author of this scheme manually performed the coding process following the coding scheme over a two-month period. In order to ensure intra-coder reliability, 92 posts were coded on all variables in a pilot study and re-coded after two weeks, and again at four weeks, resulting in consistency across results. A Word/Phrase Frequency Counter was used to calculate the salience of frequently appearing signs.

Table 1. Descriptions of analytical aspects and coding instructions

Findings

A visual content analysis of Facebook posts published by local authorities was performed to investigate what social media representations of older people can be seen, compared with other lifestage groups. The study's findings are given in the following.

Presence of Age Groups

Presence of Age Groups refers to the degree to which particular age groups were portrayed in the material. Findings show that a small number of photos do not indicate the lifestage of citizens. These were mostly published by the central administration, the public housing company and the tourist information office. Infants were mainly portrayed by family centres and preschools; children and adolescents were mostly captured by recreation centres and schools; adults were presented by a wide range of local authorities. Yet, media representations of older people were largely generated by particular authorities (e.g. the art museum, cultural nights, the municipality's central administration and the city library). With a focus on assessing the (in)visibility of minorities among older people on these Facebook pages, this study found that only four out of 37 photos depicted older people in wheelchairs, denoting those with physical disabilities. Few photos showed older people from minority ethnic groups or living with severe illnesses. Thus, it was observed that certain groups in later life were insufficiently depicted on Facebook, despite the fact that Swedish public authorities endeavour to promote an inclusive media representation of senior citizens in an intersectional manner.

Multiple Age Groups

The aspect Multiple Age Groups was designed to reveal the extent to which the leading actor was depicted together with individuals at other lifestages. Infants were mostly presented in multigenerational settings (with middle-aged care-givers), whereas other age groups were frequently shown only with their age peers. Older people were presented to a great extent with either middle-aged care-givers or senior friends, but rarely with young people. These depictions contribute to the representation of insufficient interactions occurring between age groups, failing to establish an imaginary of intergenerational relations across the wider society considering the provision of welfare.

Other People

Through the aspect of Other People, this study identified any other individuals interacting with the leading actor(s) in the photos. Findings reveal that local authorities mostly presented citizens with similar-age peers and in interactive relationships; e.g. they mainly depicted adolescents actively interacting with friends close in age. In pondering what types of people can be recognised, the findings suggest that juveniles and older people are depicted with someone offering (in-)formal care to them, which implies dependency. However, there is not enough material to characterise the major groups of other people frequently accompanying older people, due to the number of Facebook posts being limited.

Activities and Roles in Activity

Activities and Roles in Activity reveal that posing is the most common activity in the photos depicting almost all age groups (as shown in Table 2). The Facebook photos predominantly portrayed children and adolescents engaged in activities that are pertinent to the physical, intellectual and social developments when moving from childhood to adulthood; in addition, they mostly presented adults participating in work-related events. Meanwhile, older people were represented in leisure-based or care-based social gatherings, for instance coffee breaks or footcare. The limited photos of older people do not allow us to pinpoint the specific activities in which older people were overwhelmingly portrayed.

Table 2. Activities and roles in activity

The findings suggest that the photos depicted young people undertaking a variety of active roles in exercising autonomy while presenting older people in less-agentic roles. The tripartite division of the lifecourse into three segments was also represented in the photos: preparation for work (e.g. vocational education and training for teenagers), working years (e.g. giving a speech/presentation, having a business meeting) and retirement (e.g. coffee breaks, foot bathing).

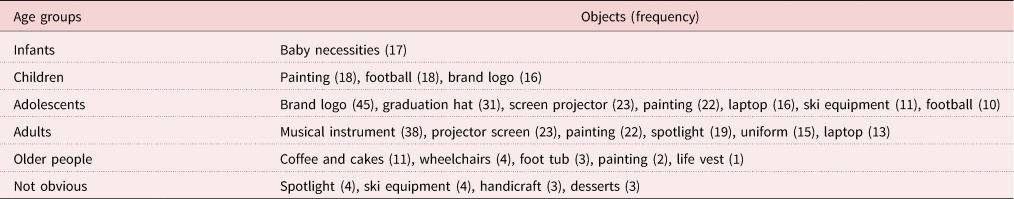

Objects

Some recurring objects were found to correspond to lifestage groups (as shown in Table 3). The findings revealed six kinds of objects: brand logos, household necessities, recreational stuff, business-related objects, natural entities and identifiable objects. Based on the presence of some of the objects shown in the photos, this study identified the typical representation of each age group in the media: infants with baby necessities, children with paintings and footballs, adolescents with Swedish student caps and adults with musical instruments. Older people were mostly presented with coffee and cakes (11 out of 37 photos), which potentially results in media representations of older people that stress them being sociable. Considering the social perceptions of older people found in empirical studies, coffee and cakes signify the sociable trait of the ‘golden ager’ as coffee breaks are often seen as an important occasion for socialising with others.

Table 3. Objects

With the support of a comparative methodology, the findings suggest that young age groups shown in these Facebook posts were depicted with a diversity of visual symbols identifying commercial corporations, primarily relating to sports (e.g. Nike's Swoosh logo) and technology (e.g. Apple's silver logo); however, older people were not related to any of these brand logos. The greater presence of particular logos in the photos of young people could communicate a sense of young people being active consumers of athletic and technological products, especially in the market, which often values young people's preferences and expectations. As a special category of signs, brand logos carry rich connotations assigning particular attributes to brand consumers (or the target audience). Brand logos have the capability of reflecting and defining some parts of consumers’ identities, such as their beliefs and desired (or actual) lifestyles (Park et al., Reference Park, Eisingerich, Pol and Park2013); additionally, these logos can inspire people in public rituals of social bonding (Bishop, Reference Bishop2001). In this study, the presentation of brand logos contributes to the representation of young people as athletically and technologically competent, superior to older people. Moreover, young people were given a variety of roles that exercise agency (e.g. independent mechanical engineers and creative musicians); conversely, older people were less often depicted as the agents of their activities. This representation resonates with ingrained social perceptions of older people as having relatively low social status in terms of power, prestige and influence, compared to other age groups.

Physical Settings

Findings show that children and adolescents were significantly often depicted in recreation or sports centres, and adults were diversely portrayed in different work venues. These age groups were frequently depicted in open areas, which can make people feel energetic and comfortable about exercise. Yet, one of the main portrayals of older people cast later life as taking place in indoor space, which may resonate with, and even reinforce, stereotypical views of older people being unproductive at work and at risk of losing social contact. Additionally, a large number of the photos of older people could not be interpreted as illustrating any concrete surroundings or communicating specific meanings, which could be interpreted as an underrepresentation of older people.

Organisational Contexts and Roles in Context

The aspects Organisational Contexts and Roles in Context were set up to identify which local authorities were explicitly mentioned in Facebook captions and which roles were undertaken by the depicted people. This study found that Facebook posts of children and adolescents mentioned different recreation centres in most of the captions, which suggests that their municipal life takes place primarily in a leisure environment where boys and girls can develop confidence, leadership and self-discipline. Additionally, Facebook posts of older people noted two other kinds of organisations in the captions: cultural organisations working on spreading knowledge about art and literature, and residential homes offering social care. The explicit mention of these authorities in the captions indicates that older people are important beneficiaries of cultural heritage and social care.

Similarly to Roles in Activity, the findings under the aspect of Roles in Context indicated that minors and adults were depicted as active and agentic characters (e.g. artist, sportsman), whilst older people were shown in free-agency roles in the organisational context (e.g. care recipient, care home resident). This reflects empowerment and agency varying throughout the phases of the lifecourse: teenagers have agency in the transition to adulthood; older people withdraw from public roles and society. In this respect, the portrayals may help to maintain the notions of children as ‘beings and becomings’ (Uprichard, Reference Uprichard2008) and older people as ‘has-beens’ (Krekula et al., Reference Krekula, Närvänen and Näsman2005).

Themes

Themes was suggested in order to investigate the themes that are embedded in the depictions of each age group. Although each age group was associated with particular themes, adults were correlated with heterogeneous themes. As the most prominent themes identified in the depictions of most age groups, ‘Culture and Leisure’ represents children's and teenagers’ involvement in music, sports and design, as well as older people's meetings with friends and participation in cultural organisations. ‘School and Preschool’ refers to play-based learning programmes for infants, school education or vocational training for children and young people, and informal learning in later life. ‘Support and Care’ concerns nursery care for babies, family care for children and young people, care-giving by middle-aged people and social care for older people. ‘Work and Business’ represents the professional life of the workforce and later-life employment in the creative industries (crafts and publishing). ‘Accommodation’ refers to young people's participation in community gardening, the home life of adults and senior housing for people aged 65 years or over. ‘Civic Engagement’ represents group activities undertaken by citizens promoting the sustainable development of society, such as campaigns and international co-operation. Most of the themes embedded in the Facebook posts featuring young people could be conceived of as domains in which older people might feasibly and acceptably take part.

Older people were predominantly depicted in a particular way in two themes (‘Culture and Leisure’, ‘Support and Care’). Under the theme ‘Culture and Leisure’, Facebook captions mainly described older people as active participants in cultural programmes and entertainment activities. The representation of retirement leisure was manifested as older people engaging in artwork design and musical performances, which mirrors positive stereotypes of older people (e.g. a golden period of leisure, youthfulness). Facebook captions under the theme of ‘Support and Care’ predominantly depicted older people receiving social care services; however, the corresponding photos portrayed senior care recipients as physically capable and socially involved to a moderate extent, given the marginalisation of walking aids in the photo frame. This media representation of older people indicates local authorities’ efforts to construct a relatively superior status for senior care recipients and to challenge negative stereotypical views of the oldest-old as ‘burdensome’.

This study found that older people were portrayed in a less-diversified manner in all respects (activity, roles within an activity, other people, objects, physical setting and organisational context) than other age groups (children, adolescents and adults), who were depicted across a much broader range of each aspect. Local authorities tended to depict older people having coffee indoors, in most cases accompanied by age peers or care-givers. Additionally, the Facebook captions often depicted older people as recipients of social care services and participants in leisure activities. However, these depictions produced a less-diversified representation of older people, which enables citizens to perceive them as a homogeneous group, while also not being fully aware of different ageing experiences and outcomes. This representation contributes to a post-work identity of older people engaging in leisure activities and care homes, given that newly retired people would reflect upon how they should live.

Since repeated representations of social groups in particular ways by the media can be conceived of as the construction of stereotypical media representations, the present study attempted to identify what aspects of media portrayals of older people identified on the Facebook pages of local authorities can be seen as dominant, and how extensive such portrayals are. Based on the findings described above, social media depictions of older people were predominantly found in the aspects Objects and Themes, whereas they seemed much less prominent within other aspects due to the numbers of photos of older people being limited. Based on the evidence exclusively derived from these Facebook posts, the dominant social media representation of the lifecourse can be described as: newborns were accompanied by their parents and received services from family centres; children were engaged in a wide range of leisure activities prearranged by youth recreation centres, together with friends and leisure managers; teenagers were depicted pursuing their education and developing collaborative leadership skills; after finishing school, citizens tended to perform work duties mainly in the public sector; and older people were provided with residential care and engaged in planned activities.

Discussion

The present study examined social media representations of older people through a visual content analysis of the signs, activities and contexts depicted in a set of Facebook posts. Given that signs are seen as elemental units for conveying meaning (Fiske, Reference Fiske2002: 40), audiences can make sense of the content relating to older people and later life by using these signs and connotations. This study identified the repeated signs, activities and contexts that serve to represent older people as remaining socially engaged and moderately physically capable. This representation of older people on the Facebook pages mostly reflects the positive stereotype of older people as ‘golden agers’, which contrasts with a previous study (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Chung, Bedford and Navrazhina2014) arguing that Facebook might be a social networking site for negative stereotypes of older people.

Drawing upon the theoretical conceptions of old age, this life phase has been refined as two new stages of life, the ‘third age’ and the ‘fourth age’, highlighting the distinction between the young-old and oldest-old (Laslett, Reference Laslett1994; Neugarten, Reference Neugarten1968). The young-old (aged 60–79 years) are seen as those in active retirement who exhibit choice, autonomy, self-expression and pleasure, while the oldest-old (aged 80 years and over) are considered to be ‘the others’ and are associated with narratives of loss of autonomy, dependency, frailty, decline and death (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010, Reference Gilleard, Higgs, Green, Murphy and Model2014). These distinctions between phases of later life might be represented on social media, because the media can function as both informing and reflecting society. The present study's findings confirmed the distinction between the young-old and oldest-old in social media representations. Specifically, the young-old were depicted as third agers enjoying active lives; the oldest-old members of society were portrayed as less agentic but sociable and relatively physically capable.

Gilleard and Higgs (Reference Gilleard and Higgs2008) have argued that the cultural capital of the third age mostly flows from the effective use of individual leisure time rather than from contributions in working life, given the logic of consumption and the individualisation of society's surplus for defining the third age. However, the present study's findings deconstructed this cultural construction of the third age. Older people were mainly shown engaged in a limited number of leisure-based and low-consumption social activities (e.g. coffee breaks and footbaths). Additionally, the Facebook posts published by cultural organisations working on spreading knowledge about literature and art mostly depicted older people remaining in the workforce, for instance as authors or art workers. Pickard (Reference Pickard2019) has argued that the dominant representation of third agers appears problematic, because it homogenises older people and masks the inequalities stratified by class, race, gender and others. In the present study, this homogenised representation of older people was established through dominant depictions of sociable third agers and reinforced by insufficient portrayals of much older people or certain sub-groups.

Based on a literature review of studies examining the image of ageing, Bai (Reference Bai2014) found that older people were predominately portrayed as a dependent, vulnerable, frail, incompetent and disempowered group. However, this prevailing representation of older people differs even from social media representations of the oldest-old found in the present study. On the Facebook pages analysed, the oldest-old people were represented in an overly optimistic light. Specifically, while senior care recipients were mostly portrayed as employing good self-management but with care-givers shown on the side, their walking aids were often shown at the edge of the photo frame, thus becoming unnoticeable and failing to communicate the ‘reality’ of these people. Considering that the older people who receive social care services in Sweden generally have extensive care needs (Schön et al., Reference Schön, Lagergren and Kåreholt2016), this paper argues that the social media representation of the oldest-old collides with the ‘fourth age’ reality of senior care recipients, in this area at least. This can be interpreted as evidence of distancing older people from the ageist stereotypes (e.g. dependence, loss of agency and dignity) that are seemingly associated with the fourth age. Kydd et al. (Reference Kydd, Fleming, Gardner, Hafford-Letchfield, Ayalon and Tesch-Römer2018) believe that the notion of distancing has taken root in the social fear of unpredictable ageing and entering the fourth age with increasing dependency. Media images can convey particular claims and define what are appropriate thoughts, actions and roles for members of society (Gorham, Reference Gorham1999). In this respect, the overly optimistic depictions of senior care recipients are presumably problematic, because such misinformation about the oldest-old might lead their relatives and care-givers to mistakenly assess the physical functioning of older people.

Since local authorities have gradually become engaged in social media, their media practices could be one of the factors accountable for representing the active social lives of third agers prominently but the fragile and dependent lives of fourth agers only marginally on their Facebook pages. As Hjarvard (Reference Hjarvard2008) noted, the media has emerged as an independent institution with its own logic and has simultaneously become an integrated part of other institutions. This is defined as the mediatisation of society. Recent evidence suggests that this mediatisation has begun within Swedish local authorities in the ways in which these organisations have become adaptive to the institutional and technological modus operandi of the media (Fredriksson and Pallas, Reference Fredriksson and Pallas2016; Olsson and Eriksson, Reference Olsson and Eriksson2016). Specifically, the administrations are inclined to communicate the message that their organisations are well run and rational, to value their media reputations and attempt to avert the negative impacts of media coverage (Boon et al., Reference Boon, Salomonsen, Verhoest, Pedersen, Bach and Wegrich2019). In this regard, the authorities presumably favour media depictions of older people who remain agentic with the intention of showing that local authority services are of good quality and well organised.

Social media replaces the traditional one-way institutional communication with multi-dimensional communications, enabling local authorities to recognise the importance of social media users’ engagement and to adjust their practices of social media use accordingly. For instance, the Swedish authorities have considered their audience to consist of specified segments of the citizenry and have adopted a communicative tone of ‘friendliness’ (Olsson and Eriksson, Reference Olsson and Eriksson2016). As a special segment of the social media audience, older media users have turned out to be a growing group on social media platforms, especially on Facebook. It has been reported that 4 per cent of older people aged between 65 and 79 in Sweden used social media as of 2009, rising sharply to 39 per cent by 2018 (Nordicom, 2019). Facebook has been experiencing a loss of its youngest users, while seeing growth in older age groups in the UK and the USA (Saul, Reference Saul2014; Schaffel, Reference Schaffel2018; Sweney, Reference Sweney2018). Since many older people do not want to be seen as the ‘burdensome’ oldest-old (Kydd et al., Reference Kydd, Fleming, Gardner, Hafford-Letchfield, Ayalon and Tesch-Römer2018), local authorities might support depictions of active older people, which appears to be a more favourable social imaginary. Additionally, older people's relatives seem to be an important group of social media users (or audiences) whom it is worthwhile for local authorities to be informed by and connected with. Carlstedt and Jönson (Reference Carlstedt and Jönson2020) found that Swedish nursing homes represented senior residents as sociable in order to satisfy the unrealistic expectations of relatives. This helps us to understand the present study's findings showing that fragile and critically ill older people were invisible on the Facebook pages of local authorities.

Conclusion

The present study has identified the recurring signs, activities and contexts of older people shown in the Facebook posts published by local authorities. These favourably but stereotypically depicted older people as remaining socially engaged and moderately physically capable. It also found that the young-old were represented in active and agentic life, while the oldest-old were represented as being less agentic but still sociable and modestly physically competent. When compared with other age groups, older people were represented as inferior and in a less-diversified manner.

It is expected that this study will contribute to an improved understanding of social media representations of older people in the following respects. The present analysis has extended our knowledge of the extent to which, and in which aspects, older people were depicted in a particular way. The identified Facebook representations of older people mirrored and maintained positive social perceptions, which contrasted with many previous findings of social media representations of older people as mostly frail, infirm and incompetent. Additionally, the comparative methodology used in this study can be applied to other studies examining media content about older people or other groups.

Local authorities in many countries are increasingly engaging in social media and such media have become an institution with strong image-building power. Since recurring media presentations may serve as stimuli for the social membership categorisation of older people in the minds of the wider public, this paper recommends that communication officers aiming to achieve non-stereotypical media representations of older people (or other groups) reduce the frequency of stereotypical signs and advocate using a diversity of signs in the photos they choose.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions. The author would also like to thank Annika Taghizadeh Larsson and Lars-Christer Hydén for valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article. This study was accomplished within the context of the Swedish National Graduate School for Competitive Science on Ageing and Health (SWEAH) funded by the Swedish Research Council.

Financial support

This work was supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie (grant number 764632).

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.