Introduction

Much discussion on the situation in post-Soviet Russia has focused on the effects of the fall from imperial glory all the way down to painful defeat. Various sides of this contrast, captured in the concepts of “Weimar syndrome,” cultural trauma, and ressentiment, to mention the most prominent few, all share the same central point—the feeling of national humiliation (Hanson and Kopstein Reference Hanson and Kopstein1997; Sztompka Reference Sztompka2000). Discomfort and disequilibrium as the essential parts of these phenomena bring to the forefront the demand for restoration of positive national identity and national pride created by the elites and the general public alike. To follow the processes born of this demand, in this paper we look at the dynamics of national pride in post-Soviet Russia.

Interest in contemporary Russian national identity and nationalism has surged over the last few years. The existing research mostly addresses the rhetoric and actions of the country’s political elite (Kolstø Reference Kolstø2016; Blakkisrud Reference Blakkisrud2016; Laine Reference Laine2017). Our study is dedicated to the less-visible part of the picture—the notion of national pride in Russian mass consciousness. By differentiating pride in the various kinds of achievements of the country, we seek to counterbalance the subjective and objective factors and explore to what extent the dynamics of national pride parallel changes in Russia’s economy, politics, and other spheres.

The added value of the paper is found in its demonstration of the substantial net growth of Russians’ national pride in the country’s various achievements and Russian citizenship over the last 20 years as well as the corresponding drop in citizens’ shame in their country. The growth has not been confined to post-Crimean mobilization. It is present throughout all 20 years and parallels the real or imagined progress in the Russian economy, society, and political influence. In most of these years, however, the growth is selective, and not present in science, sports, arts and literature, or history. In contrast to this, the growth we attribute to the post-Crimean mobilization is almost universal and more rapid than in any preceding time period. Besides, over the post-Soviet period, Russians’ national pride has become more competitive thanks to its stronger association with the belief in the superiority of their country.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows. In the background section, we examine the existing body of research on national pride in general and post-Soviet Russian national pride in particular. Based on these considerations, we propose a series of hypotheses that can be inferred from the existing knowledge. The data and methods section presents the empirical research conducted to test these hypotheses. The results section consists of two parts. First, we share Russia’s scores on national pride and shame in 1996, 2003, 2012, 2014, and 2015 and estimate the magnitude, direction, and statistical significance of the dynamics between adjacent time points as well as the net dynamics. Second, we analyze the correlation between national pride and belief in a country’s superiority and their dynamics as well as the dynamics of the superiority belief per se. In the discussion and conclusion section, we confront the hypotheses with the accumulated empirical evidence on Russian national pride and formulate some suggestions for investigating the dynamics of national pride in other countries.

Background

National pride is a favorable attitude toward one’s country in general, toward its specific achievements, and toward one’s national identity (Smith and Kim Reference Smith and Kim2006). The peculiarity of pride is found in its communicative context, since pride is a favorable attitudinal message addressed to significant others (mainly foreigners) with the expectation of a favorable response from them. Thus, national pride combines one’s own favorable attitude toward the country with the expectation of a favorable attitude from significant others. Compared to evaluations of satisfaction, pride statements imply higher standards of excellence. To be proud of something requires a higher perceived quality of the relevant object than to be satisfied with it.

Contemporary nation-states as well as their citizens strive for positive national identity and strong national pride as their attributes, and the focus on positive or strong pride is predominant in national pride studies. This striving for positive or strong national pride is implied by several theoretical traditions. Tajfel (Reference Tajfel2010) posits the general need for attributing positive significance to any social identity; Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2001) introduces a general notion of national identity as “natural” and “healthy”; Almond and Verba (Reference Almond and Verba1963) consider national pride a necessary prerequisite for the formation of a civic culture based on a strong sense of solidarity. Most theories of nationalism suggest that governments make a special effort to promote strong national pride in their citizens using schooling, media, and other social institutions (Billig Reference Billig1995; Anderson Reference Anderson2004; Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm2012). Their immediate goal is strong national pride, no matter how well it is grounded in the country’s achievements. In their seminal work, Almond and Verba classified national pride as an emotional component of political culture, and this classification does not imply any cognitive process of relating pride to the country’s achievements. In line with such an approach, Solt (Reference Solt2011) demonstrates that stronger national pride may serve as the compensatory response to the country’s level of inequality, and such a compensatory relation does not imply any connection between pride and the country’s achievements either.

Contrary to this predominant theoretical assumption, some publications on national pride (Magun and Magun Reference Magun and Magun2009; Fabrykant and Magun Reference Fabrykant and Magun2016) outline the idea that when generating statements on how proud they are of their country and its achievements, respondents do perform some cognitive work. They try to consider the country’s actual achievements and compare them with its aspired state. The extent of such cognitive work varies for different kinds of statements. It is higher for pride in specific achievements and lower for generalized pride, which is more directly affected by relevant social norms. Needless to say, in many cases people have no direct access to the objective manifestations of actual achievements of their country and rely on secondary messages provided by the media. Still, even in such cases, their pride statements may result from some cognitive efforts and can be considered grounded, and not purely normative.

This theoretical idea is supported by empirical evidence from 32 countries analyzed by means of a multilevel regression (Fabrykant and Magun Reference Fabrykant and Magun2016). The study shows that national pride in various countries’ achievements actually depends on the countries’ economic and socioeconomic achievements (reflected in the gross domestic product [GDP] per capita and human development index [HDI] measures), and that this association can be mediated by cognitive processes, as mentioned above.

Another cleavage, besides the one between grounded and normative pride introduced in the previous research, relates to the structure of national pride in country-specific achievements. Based on factor analysis results, Hjerm (Reference Hjerm2003) categorizes pride variables related to various specific achievements as either political and cultural, which he considered two independent kinds of national pride. Later, Magun and Magun (Reference Magun and Magun2009) and Fabrykant and Magun (Reference Fabrykant and Magun2016) suggest other terms for these two kinds of pride, namely pride in mass versus elitist achievements. Mass achievements refer to the economy, social security, democracy, fair and equal treatment of all groups in society, and the country’s political influence in the world. Their distinctive feature is that their inputs and outputs are perceived as more closely related to laypeople’s experiences. Elitist achievements refer to arts and literature, sports, science and technology, and history; their inputs and outputs appear to laypeople as rather distant from their daily lives. Elitist achievements result from the activity of the great people of the past and present, and mass achievements are produced by the present-day national state. There is also a difference in the access to information about the two kinds of achievements. Pride in mass achievements is more affected by the immediate experience of individual participation in a country’s economic, social, and political life than the pride in elitist achievements. The latter is more affected by information from media reports of achievements of past and present elites and is more likely to be normative. Interestingly, the only exception belonging to neither type was pride in the armed forces.

Instead of the two independent sets of pride variables suggested by Hjerm (Reference Hjerm2003), the alternative analysis presented in those later publications detects the coexistence of two types of relations between mass and elitist pride. The predominant one is the positive, friendly relation indicating the compatibility of the two kinds of pride, but the secondary one is the conflict relation between them. Correspondingly, pride in country-specific achievements is described by two dimensions, one of which is general pride in the country’s various achievements, and the other of which is the conflict between pride in elitist and mass achievements. Cross-country comparisons demonstrate that a country’s socioeconomic achievements affect both dimensions of national pride: higher GDP per capita and higher HDI cause higher levels of general pride in a country’s various achievements and, additionally, cause relatively higher pride in mass than elitist achievements (Fabrykant and Magun Reference Fabrykant and Magun2016). The dynamics of national pride in Russia should be considered in this general frame of reference developed for the analysis of national pride.

The studies examining the various facets of Russians’ attitudes toward national pride in 1996 and 2003 all demonstrate a rather low level of pride in the country’s mass achievements and armed forces, with average scores either lower or just slightly higher than “not very proud” (Gudkov Reference Gudkov1999; Bavin Reference Bavin2003; Magun and Magun Reference Magun and Magun2009; Grigoryan Reference Grigoryan2014; Fabrykant and Magun Reference Fabrykant and Magun2016). The average scores for pride in elitist achievements were around “somewhat proud,” which is higher than for mass achievements in Russia but still lower than that of most other countries. So, the need for positive national identity and strong national pride was not satisfied in these years. That is why, for many post-Soviet years, the wish for Russia “to restore its status as a great power” (velikaia derzhava) appeared among the most widespread popular aspirations and was featured among the top three expectations of a prospective presidential candidate (Gudkov Reference Gudkov2014, 40–41). All these facts indicate the prerequisites of a strong demand for higher national pride.

This demand, moreover, meets the other kind of preconditions for the growth of national pride from the supply side. Based on the differentiation between grounded and normative national pride, the necessary supply may come in the form of objective grounds for national pride or as massively transmitted state rhetoric that such grounds for pride exist. Publications in Russian studies demonstrate both these prerequisites.

Most research focuses on the rhetorical part of the national pride related supply. Much of the analysis of national identity issues in contemporary Russia are dedicated to the country’s massive ideological bases for instigating national pride such as neo-Eurasianism (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2004; Shekhovtsov and Umland Reference Shekhovtsov and Umland2009; Østbø Reference Østbø2016; Clover Reference Clover2016) and other, milder and somewhat more conventional ideologies present in the top-down political rhetoric (Malinova Reference Malinova2014; Blakkisrud Reference Blakkisrud2016; Kolstø Reference Kolstø2016; Laruelle Reference Laruelle2016), which are intensely transmitted via popular media, especially television (Tolz 2016). Only a few authors complement this view with analysis of the objective components of the supply side. Specifically, Shleifer and Treisman (Reference Shleifer and Treisman2005, Reference Shleifer and Treisman2014; see also Treisman Reference Treisman2011) show that post-Soviet Russia achieved real progress in economics and institution building, and their conclusion can be interpreted as suggesting objective grounds for an increase in national pride in Russia. Still, as the authors themselves remark, their views oppose the prevailing position, which regards post-Soviet Russia as a failure and an aberration and its economy as underperforming. Some critiques go as far as to define Russia as “abnormal,” with scant prospect for improvement (Rosefielde Reference Rosefielde2005; Hedlund Reference Hedlund2008) and therefore more grounds for shame than pride.

The interplay of objective grounds and ideological mobilization as two kinds of supply factors is well illustrated by the annexation of Crimea. In a public opinion poll, the incorporation of Crimea into Russia, as well as the preceding victory of the Russian team at the Winter Olympics in 2014 (the post factum annulment of some medals won by the Russian team occurred only much later) were two of the three most popular answers to the question about “the most important events in 2014” (the third one was the “collapse of the [Russian] ruble;” Levada Center 2015b, 9). Both of these events were appreciated and perceived as tangible achievements for the country by the vast majority of the Russian population (Levada Center 2015b, 174–176, 214–216). As a result, the survey data demonstrate that the generalized national pride measured several months after these events increased considerably compared to the previous measurement (Levada Center 2015a). The upsurge of national pride constitutes a part of a general positive shift in various kinds of social attitudes after February 2014 (Rogov Reference Rogov2015; Levinson and Goncharov Reference Levinson and Goncharov2015). In their explanations of the increase in national pride and other facets of well-being after February 2014, researchers paid attention to the dramatic increase in the volume of political news and explanations broadcasted by the state-controlled TV channels (Borodina Reference Borodina2014) and consumed by the general public (Gudkov Reference Gudkov2014, 219; Borodina Reference Borodina2014; Rogov Reference Rogov2015). This patriotic campaign gave fresh impetus to the state patriotism policy, which has been around since the early 2000s. The new “Program for patriotic education in the years 2016–2020,” a successor of similar programs for the preceding periods of 2001–2005, 2006–2010, and 2011–2015, proclaims as its goal inter alia “the education of pride in the past and current country’s achievements” (Medvedev Reference Medvedev2015). The recent parliamentary initiative aims at turning a series of five-year programs into a full-fledged law, making patriotic education mandatory and unified all over Russia.Footnote 1

This brief review demonstrates that, to the present moment, the dynamics of national pride in the post-Soviet period has received fragmentary attention only in the sporadic press releases by the Russian public opinion centers Fond Obshhestvennoe Mnenie (Public Opinion Foundation, 2010), the Levada Center (2015a, 2016a), and VCIOM (Russian Public Opinion Research Center 2015). Most of these data reflect the net increase in national pride and decrease in the shame of the country during the tracked periods. There are two exceptions: the first concerns the decrease in the generalized pride from 2002 up to 2010, and the second concerns the decrease of the pride in achievement in sports from February 2014 to May 2016.

Leaving aside its fragmented nature, the available survey data on the dynamics of national pride tracks a range of 11 years at best and predominantly features its generalized indicators; they track the specific indicators across time spans of only two years. The analyses of these data do not compute the size of effects and their measures’ statistical significance and do not control for change in the sociodemographic structure of the country’s population. This paper compensates for these deficiencies by providing a systematic, methodologically rigorous review of the dynamics of Russian national pride comprising a period of 20 years. Based on the reviewed studies of national pride in general and in Russia in particular, we suggest that in contemporary Russia, the shared need for positive national identity amplified by the real progress during the country’s post-Soviet development led to a net increase in Russians’ national pride. Such an increase could be easily taken for granted if it were dated by the incorporation of Crimea or the successful Olympics organization and participation in 2014, but the current paper traces it to an earlier period of post-Soviet transformations.

Hypotheses and Rationale

The years from 1999 to 2012 (with the exception of the post-crisis year 2009) were a time of rapid growth of the Russian economy, which then slowed down from 2012 to 2014 and, in 2015, turned into a recession (Akindinova and Yasin Reference Akindinova and Yasin2015; Akindinova, Kuz’minov, and Yasin Reference Akindinova, Kuz’minov and Yasin2016; Gurvich Reference Gurvich2016a, Reference Gurvich2016b). In addition, political achievements occurred parallel to the economic growth. The satisfactory outcome of the second Chechen war counteracted the demoralizing effect of the first one. The campaign in Georgia in 2008 augmented the military record of the Russian army as well. Based on the idea that national pride reflects a country’s perceived achievements, national pride in Russia can be expected to have increased before the incorporation of Crimea. Previous multi-country research has demonstrated that a country’s socioeconomic advancement primarily affects pride in mass achievements, and it can be expected that the Russian dynamics would feature the same emphasis. The same is true for the military victories of the 2000s, which should affect pride in the army.

H1. The non-Crimea pride increase: since the start of the post-Soviet economic growth and prior to the incorporation of Crimea, pride in all of the country’s achievements increased, especially pride in mass achievements and the armed forces.

The incorporation of Crimea into Russia in the spring of 2014 was perceived by the majority of Russians as one of the country’s greatest achievements, and it had a strong positive impact on general national pride as well as on other social attitudes substantively unrelated to the focal event. This public response was amplified by the simultaneously implemented media campaign of patriotic mobilization, which probably would have strong generalized effects on national pride in most countries’ achievements.

H2. The Crimea pride increase: the incorporation of Crimea led to an increase in pride in most kinds of the country’s achievements. This growth was faster than the growth in pride in the preceding period of post-Soviet history.

The period between late 2014 and late 2015 encompasses a series of momentous events in various spheres. In the socioeconomic sphere, the drop in oil prices and the resulting rapid depreciation of the Russian ruble after “black Thursday” on 16 December 2014 must have had a sobering effect on pride in the economy. In the geopolitical sphere, on the contrary, the agenda of the previous period kept unfolding with the beginning of Russia’s military operation in Syria. For this reason, pride in the army and probably in the country’s political influence in the world was likely to continue growing, albeit more slowly than immediately after the incorporation of Crimea.

H3. Post-Crimea pride dynamics: a year after the incorporation of Crimea, pride in most achievements stagnated and pride in the country’s economy even declined, while pride in the armed forces and political influence in the world continued to grow.

Smith and Jarkko (Reference Smith and Jarkko1998) and Smith and Kim (Reference Smith and Kim2006) allow for a possible association between national pride and placing one’s own country above others. We suggest that it is worthwhile to regard such national pride as competitive (implying win-lose relations) as opposed to noncompetitive (not implying win-lose relations). This emphasis on competition boosts a self-serving social comparison, which appears in the Russian case as resentment against the West and particularly the USA (Morozov Reference Morozov2015; Hopf Reference Hopf2016). The notion of “great power,” so attractive to the Russian public, implies inter alia that a country is superior to other countries. The indicator of superiority in our dataset is the belief that “Russia is a better country than most other countries,” and in line with the wish of the population, we expect that this belief grew stronger between 1996 and 2015. By the same token, pride in the country’s achievements became more competitive—that is, more strongly associated with the belief in the country’s superiority.

H4. Belief in Russia’s superiority over other countries and positive correlation between this belief and prideful attitudes increased throughout the post-Soviet period.

Data and Methods

In the present research, we test the hypotheses on the dynamics of Russian national pride using five datasets provided by five survey waves. Three of these were run within the framework of the International Social Survey Program (ISSP), which is one of the most comprehensive international survey series. The three rounds of the ISSP included in our analyses, from 1995–1996, 2003–2004, and 2012–2014, are entirely dedicated to national identity.Footnote 2

Each dataset of the ISSP–National Identity module contains a variety of survey items reflecting respondents’ views on various facets of nationality, including national pride. The fourth and fifth datasets included in our analyses reproduce all the relevant variables of national pride but were collected in Russia in surveys not affiliated with the ISSP.

The data were collected in June 1996, July 2003, October 2012, November 2014–February 2015 (which we consider as entirely belonging to 2014, since only approximately 17% of respondents were polled in 2015), and October–November 2015. The 1996 survey was conducted by VCIOM, the surveys from 2003, 2012, and 2015 were conducted by the Levada Center, and the survey from 2014 was conducted by the Institute of Comparative Social Research. In our empirical analyses, we therefore use a harmonized dataset comprising the data on national pride collected in Russia in 1996, 2003, 2012, 2014, and 2015. The sizes of each representative national sample are 1585, 2383, 1516, 1244, and 1603 respondents, respectively. The first three surveys represent the non-Crimea period, divided into two roughly equal time spans (1996 to 2003 and 2003 to 2012), and the last three represent the Crimean period, also divided into two much shorter, also roughly comparable periods (2012 to 2014 and 2014 to 2015).

To detect changes in the level of the indicators of national pride that occurred between each the five waves of the survey, we use regression analysis. It yields coefficients estimating strength and significance of the shifts of national pride between each survey time point. In more technical terms, we estimate ordinal logistic regression models for each facet of national pride and pride-related phenomena as dependent variables. All the models have the same independent variables. The main variables indicate in which survey wave each piece of data was collected. To account for possible effects of sociodemographic changes in Russia’s population on national pride, we also add several basic sociodemographic parameters as independent variables to each regression model. The models differ by reference survey waves.

The set of questions to measure national pride are introduced as follows: “how proud are you of Russia in each of the following?” Respondents are then required to express their pride on a four-point scale (“not proud at all,” “not very proud,” “somewhat proud,” or “very proud”) for each of the following specific achievements of their country: the way democracy works; its political influence in the world; Russia’s economic achievements; its social security system; its scientific and technological achievements; its achievements in sports; its achievements in arts and literature; Russia’s armed forces; its history; and its fair and equal treatment of all groups in society. The survey also contains a question on generalized pride in nationality by asking, “how proud are you of being a Russian citizen?” with the same response options. In other countries, in place of Russia, the same questions include the names of the relevant countries.

Two pride-related dependent variables include national shame and belief in the country’s superiority. The questions for these variables are worded as (1) “there are some things about Russia today that make me feel ashamed of Russia,” and (2) “generally speaking, Russia is a better country than most other countries,” with response options of “disagree strongly” (1), “disagree” (2), “neither agree nor disagree” (3), “agree” (4), and “agree strongly” (5). The original scales measuring national pride and pride-related variables had the opposite direction.

The sociodemographic control variables are represented by age (measured in full years), gender, education (operationalized as the total number of years a respondent spent receiving education), marital status (five options: officially married, cohabitating, widowed, separated/divorced, and single, never married), subjective social status (self-evaluated on a five-point scale where 1 is lowest and 5 is highest), employer organization type (recoded into a variable showing whether a respondent is employed by a government or public sector organization or by a nongovernmental employer), number of working hours per week, and religiosity (operationalized as frequency of attendance of religious services ranging from 1, never, to 6, several times a week).

All these variables and the relevant questions appear in the same manner in all three rounds of the ISSP–National Identity module, and the data for Russia are available in all these datasets. Moreover, beyond the ISSP project, these same questions were posed to Russian respondents in 2014 and 2015, and these surveys strictly reproduce the wording of the relevant ISSP questions. There were, however, two exceptions. The question on pride in nationality was absent from the questionnaires used in 1996 and 2015, and the question on shame was not included in the same dataset with the other questions in 2015. This makes it impossible to estimate a regression model for shame as a dependent variable, but does nonetheless allow us to compute a country average for 2015.

To evaluate the dynamics of national pride in Russia in comparison to other countries, we use the data for 11 countries represented in all three waves of the ISSP–National Identity module: Czech Republic, Hungary, Ireland, Japan, Latvia, Norway, Philippines, Russia, Slovenia, the United Kingdom, and the USA.

Thus, the data used in this paper yield the most comprehensive dataset to date on national pride in Russia that can be comprised from national surveys conducted within the post-Soviet period. We are aware of the fact that the collection of datasets we have at our disposal does not constitute a time series and, therefore, does not allow us to trace changes year by year. Nevertheless, the exact time points of the surveys allow to us trace the three periods of pride change corresponding to our substantive hypotheses. The hypotheses outlined in this paper do not refer to the exact time points of the surveys, but the surveys available fortunately allow the examination of the three periods of pride change corresponding to our substantive hypotheses.

The time spans between each of the first three waves are quite long (seven and nine years), and might include several shifts in national pride in varying directions. Nonetheless, the analysis detects the statistically significant net changes for each of these long time spans, findings which indicate the predominant directions of change over time. The most recent surveys in 2014 and 2015 provide the opportunity to follow shorter-term changes, and this opportunity appears especially relevant for the period of increased national pride vulnerability.

Results

Dynamics of National Pride

This section deals with the changes in the levels of various indicators of national pride between each of the five survey waves. The results are presented in Table 1, which contains four regression models for each dependent variable. Each model compares the data on a dependent variable for a certain wave with each other wave. Thus, the first model compares the level of national pride in 1996 to the levels of national pride in 2003, 2012, 2014, and 2015. Positive regression coefficients in the body of the table indicate growth in an indicator of national pride from the 1996 reference wave to the wave compared to it, and negative scores indicate decline. Changes for other periods were tested in the same way for models two to four. The coefficients estimating the impact of the sociodemographic variables are presented for each indicator of national pride only once, because they stay the same in all the regression models.

Table 1 Ordinal Regression Models of National Pride, Shame, and Belief in Russia’s Superiority.

*significant at 0.05; ** significant at 0.01; *** significant at 0.001

The regression coefficients indicating changes over the period immediately following the reference wave are highlighted in bold italic.

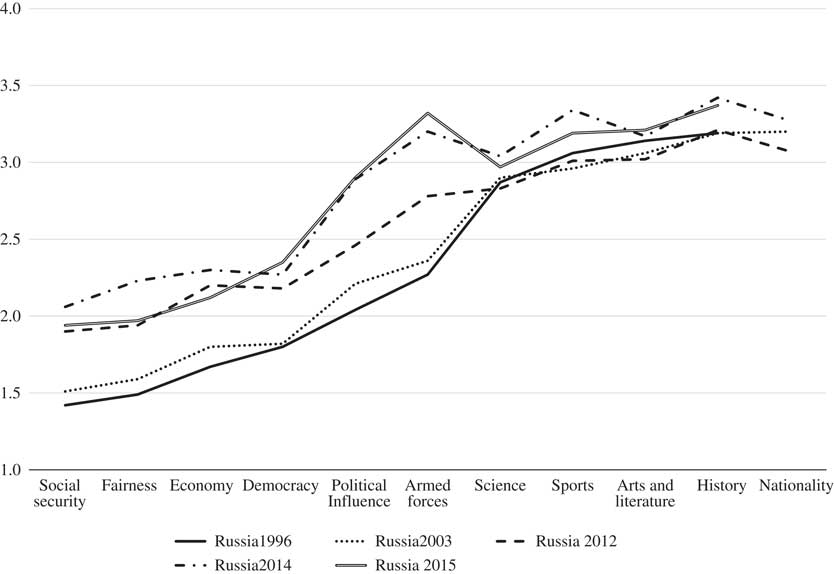

Figure 1 provides the general picture of national pride dynamics based on the country averages. Because this figure does not account for the statistical significance of cross-wave differences or the impact of sociodemographic changes in Russia’s population, our description of the results is based on the regression coefficients reported in Table 1. Nevertheless, Figure 1 roughly reproduces the main features of the regression analysis, and we include it here as a useful graphic illustration.

Figure 1 Dynamics of pride in various country’s achievements, 1996–2015 (1, not proud at all; 2, not very proud; 3, somewhat proud; 4, very proud).

The regression coefficients describe the net difference between national pride in various achievements in 2015 and 1996 (Table 1, Model 1, in italics). This is an indication of a net increase in the national pride in all the country’s achievements except arts and literature across the 20 years. There is the net increase in generalized pride in nationality from 2003 to 2014 as well. The weak correlation (averaging about 0.1 out of 1.0) of the national pride facets with belief in unconditional support of one’s country (a survey item measuring the level of agreement with the statement that “people should support their country even if the country is in the wrong”) shows that most respondents do not report an exaggerated level of pride just out of loyalty.

The changes between the adjacent waves (e.g., between 1996 and 2003, 2003 and 2012; the corresponding coefficients are in italics and bold in Table 1) mostly indicate an increase in pride as well. Of the 31 significant regression coefficients, 23 (74%) of them indicate an increase in pride over time, and they are usually larger in magnitude than the negative coefficients showing a decrease in pride.

In absolute scores, on the four-point scales, the largest net increase in average score from 1996 to 2015 equals 1.0 point for pride in the armed forces and 0.9 for political influence in the world. This is followed by pride in fairness and equality with a net change of 0.7 points, then social security (0.6), the economy (0.6), and democracy (0.5). The smallest increases are in pride in sports (0.3), history (0.2), and nationality (0.1), with zero increase in pride in arts and literature. As a result, the average Russian score in 2015 was “not very proud” (or a bit more) of social security, fairness and equality, the economy, and democracy; “somewhat proud” of science and technology and political influence in the world; more than “somewhat proud” of sports, arts and literature, and nationality (2014); and slightly more than that of history and the armed forces.

Figure 1 depicts remarkable differences among the scores on pride in different kinds of achievements. In each of the five surveys conducted throughout the entire time span from 1996 to 2015, Russians were much more proud of their country’s elitist achievements and their own nationalities than of the country’s mass achievements. Because the net increase in mass pride was larger than that of elitist pride, this structural difference is most distinct in 1996 and later becomes less pronounced, as indicated by the less-steep Russian pride curves in 2012–2015 as compared to 1996–2003. Pride in the armed forces does not belong to either mass or elitist pride estimates; its score is intermediate in the first three survey waves and approaches its peak positions in the years 2014 and 2015.

Coming back to regression coefficients, we take a more detailed look at the different parts of the time span under study. The two initial periods analyzed in this paper—between 1996 and 2003 and between 2003 and 2012—are similar in their patterns of national pride change. Both of them are characterized by rising pride in mass achievements and the armed forces and declining or stagnant pride in elitist achievements and Russian citizenship. Still, in the second period, from 2003 to 2012, the increase in pride in social security, fair and equal treatment of all the groups in society, economic achievements, democracy, political influence, and the armed forces is much higher than in the first increase from 1996 to 2003.

The period between 2012 and late 2014 is notable because, for the first time, all pride estimates but two (economic achievements and democracy) increased. This growth can no longer be captured by the difference between mass and elite achievements. It is the first period since 1996 where pride in science and technology, arts and literature, history, and nationality became stronger, and the positive effects of these pride attitudes compensate or outweigh the negative effects of the previous, longer periods of change. The size of significant regression coefficients is remarkable as well. The strongest effects hold for political influence, sports, and the armed forces, and they indicate that the two-year increase in pride is stronger than the nine-year increase in the previous period (or almost as strong, in the case of the armed forces). The positive effects for pride in social security and fairness indicates a larger increase than could be expected from adjusting the previous nine-year effects.

The majority of pride increments reported in 2014 remained intact in 2015 due to the fact that in the period from late 2014 to late 2015, five pride variables stagnated, and the pride in the armed forces and democracy even increased. Three pride variables (pride in fairness, economy, and sports) decreased between 2014 and 2015, which for pride in fairness and sports means a return toward their earlier scores. Yet none of the three falling pride attitudes returned to their minimum scores.

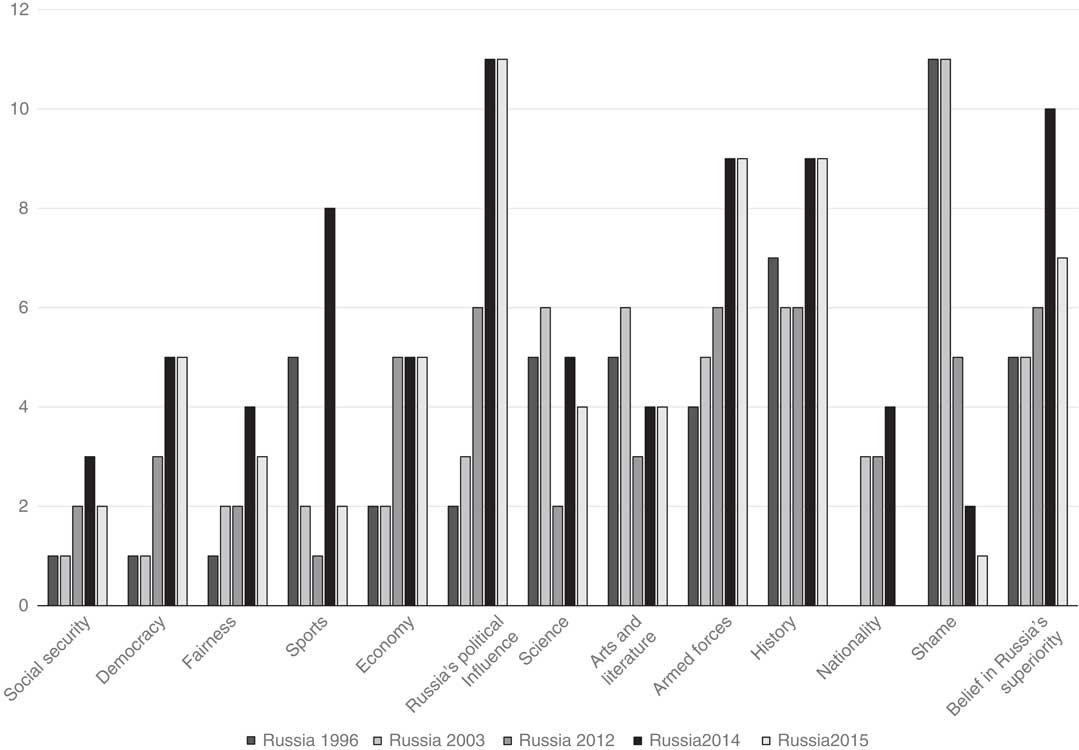

Cross-country ranking of pride scores helps compare the described dynamics of pride in Russia. The ISSP project involved many countries at different times, but the data for the three waves (1995–1996, 2002–2003, and 2012–2014) are available only for 10 countries besides Russia, namely the Czech Republic, Hungary, Ireland, Japan, Latvia, Norway, the Philippines, Slovenia, the United Kingdom, and the USA. Figure 2 illustrates the number of countries overtaken by Russia for each point in time plus one (one point was added to provide visibility for otherwise invisible zero bars), and this is a reverse of Russia’s rankings relative to the other countries. The relative ranks for Russia in 2014 increased compared to 2012 for most pride facets with the exception of pride in the economy. By 2014, which was the best year for Russian pride, Russia shifted to the highest position among the countries covered by the data on pride in political influence in the world, the third-highest position in pride in history and the armed forces, and the fourth-highest position in pride in sports (although this dropped again in 2015). However, Russians’ pride in social security, democracy, fairness, the economy, and nationality, as well as in science and the arts and literature, remain comparatively low. The shame of the country is the substantive opposite to national pride, and so we expect it to decline in parallel to the increase in national pride across the post-Soviet years. The results confirm this expectation. All three coefficients for adjacent waves indicate a decrease in shame from 1996 to 2014. The largest decrease, between 2003 and 2012, complements the increase in pride in mass achievements and the armed forces throughout the same period. We could not include the year 2015 into the regressions for shame, but a comparison of the means indicates a sharp decline in shame from 2014 to 2015 (Figure 3). The average evaluation of shame drops 1.5 points on the five-point scale across the 20 years. It is equivalent to the change in the average response to the statement “there are some things about Russia today that make me feel ashamed of Russia,” from “agree” to “neither agree nor disagree” and even a step further to “disagree.” As a result, the shame of the country fell from the highest to the lowest position among the 11 countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2 The number of countries overtaken by Russia on national pride, shame, and belief in one’s country superiority plus one, comparison of mean estimates, 1996–2015 (the scores for Russia in 2014 and 2015 were compared to the scores for other countries in 2012).

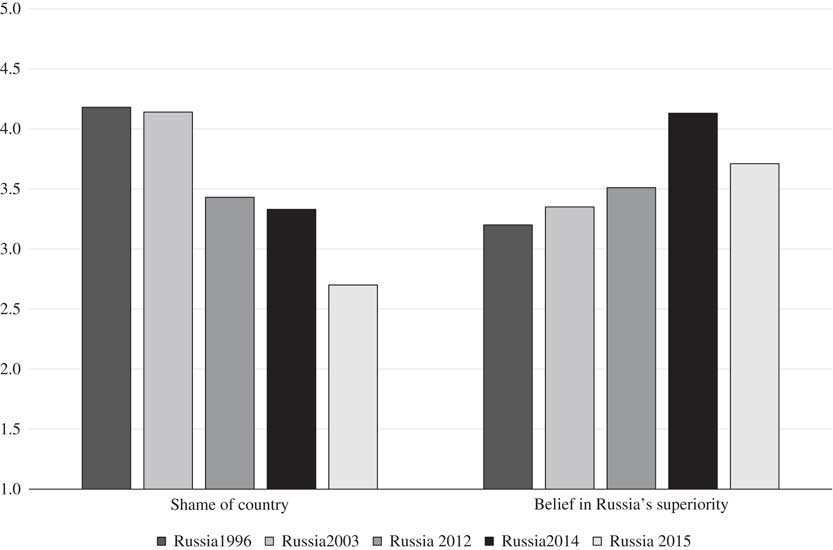

Figure 3 Dynamics of belief in Russia’s superiority and shame of country, 1996–2015 (1, disagree strongly; 2, disagree; 3, neither agree nor disagree; 4, agree; 5, agree strongly).

The sociodemographic variables were added to the regression models to clear out the wave effect due to changes in the population structure. Table 1 presents the effects of these variables on the indicators of pride, shame, and belief in the country’s superiority.

The Dynamics of Belief in Russia’s Superiority and its Association with National Pride

Both the mean scores (Figure 3) and regression coefficients for the wave dummies (Table 1) indicate consistent strengthening of the belief that, “generally speaking, Russia is a better country than most other countries” from 1996 to 2014. The average score changed from a position slightly higher than the neutral “neither agree nor disagree” in 1996 to a position slightly higher than the definitely positive “agree” in 2014 (the most positive position is “agree strongly”). In 2015, the average score came down to slightly lower than “agree.” Russians’ belief in their country’s superiority over other countries peaked at the end of 2014, immediately following both geopolitical and Olympic sports achievements. After a slight decrease in 2015, understandably following economic turmoil, this belief is still stronger than it was in 2012. Cross-country rankings (Figure 2) demonstrate the same trend. In 1996, Russians were placed in the seventh position among 11 countries in their belief in the country’s superiority; in 2014, they rose to the second position behind Japan; finally, the decrease of 2015 brought them to fifth place.

Table 2 demonstrates that all correlation coefficients between pride in a country’s various achievements and belief in its superiority are positive, and all but one are statistically significant. These findings mean that Russians’ national pride tends to be involved in social comparison processes, and the Russians who are proud of their country’s achievements tend to view them as greater than achievements of other countries. In 2015, such associations are strongest for the country’s political influence, democracy, and armed forces. These facets of national pride imply a higher inclination to compare their own country with other countries. On the contrary, arts and literature, fair and equal treatment of all social groups, and social security are the facets least likely to be compared, because they have the least correlation with belief in the superiority of Russia.

Table 2 Spearman’s Correlations Between Pride in Various Country’s Achievements and Belief in Russia’s Superiority.

Presented in descending order of correlations for the last available year.

* significant at 0.05; *** significant at 0.001.

Each line of Table 2 corresponds to a specific facet of pride, and for each facet the correlation coefficients increase from 1996 to 2015 (most differences between coefficients are statistically significant). This finding indicates that, in addition to growth in national pride, the meaning of pride throughout the 20 post-Soviet years has also changed substantively. With time, Russian pride attitudes have become more strongly associated with belief in Russia’s superiority over other countries. The largest increase over time is found for pride in democracy and political influence—in Russia, probably the two most discussed issues of comparison, and the two most difficult issues for the general public to evaluate unequivocally. The data from other countries represented in all three waves of the ISSP Online SupplementFootnote 3 show that Russia shares its increase in the strength of correlation between national pride and belief in superiority with most post-socialist countries.

Discussion and Conclusion

Taken together, the results mostly confirm all four hypotheses. The hypothesis H1 predicted a universal increase for all the pride estimates, with larger increases in pride in mass achievements and armed forces through the period of economic growth starting in 1999 but not overlapping with the incorporation of Crimea and its implications. We check this hypothesis by comparing the 1996 and 2012 surveys with the 2003 survey as the interim one. H1 is partially confirmed, with the increase in pride in mass achievements and the armed forces occurring as predicted. Still, pride in elitist achievements shows no increase at all; rather, it declined or stagnated throughout this period.

To explain this result, we refer to the abovementioned point that there are two types of relations between pride in mass and elitist achievements: generalized and conflicting. We did not formulate any hypotheses on the factors determining the predominance of each of these types of relations, but based on the results described in this paper, we can conclude the predominance of conflict in the 1996–2012 period. This conflict most likely is indicative of the compensatory function of elitist pride used by people to outweigh their cognizance of poor mass achievements of their country (Fabrykant and Magun Reference Fabrykant and Magun2016). The compensatory function is probably inherited from Soviet society, which generously provided public goods to counterbalance the scarcity of private ones (Trudolyubov Reference Trudolyubov2011), with the difference between public and private goods being rather similar to the difference between the country’s elitist and mass achievements. Accordingly, the net increase in the country’s mass achievements in 1996–2012 provides a valid basis for the corresponding increase in pride and makes it unnecessary for Russians to reassure themselves with pride in the country’s elitist achievements.

According to the rationale for hypothesis H1 outlined earlier in this paper, an increase in mass pride should result from the supply side—the country’s perceived economic and military achievements—as well as from the perceived normalization in Chechnya. There was no real progress in democracy across those years: according to Polity IV measures (the democracy index varying from −10 for complete autocracy to 10 for perfect democracy), Russia shifted from four in 1996 to five in 2012, remaining in the same category called “anocracy” (Marshall Reference Marshall2014). However, comparisons of both the regressions and averages demonstrate that pride “in the way democracy works in Russia” becomes one of the main beneficiaries of the national pride increase. The explanation lies in the way the notion of democracy is constructed in Russia. According to the 16-year monitoring by the Levada Center (from 2000 to 2015), about 30% of Russians (ranging from 24% to 47% in various years) include “the country’s economic flourishing” in their understanding of democracy. In addition, a fraction of Russia’s population of approximately the same size (from 24% to 41% in various years) consider “order and stability” one of the features of democracy (Levada Center 2016b, 51). This country-specific pattern corresponds to the conclusions of Welzel and Moreno (Reference Welzel and Moreno2015) based on comparative survey data from approximately 50 societies worldwide, including Russia.

Hypothesis H2 predicted the pride increase associated with the incorporation of Crimea, and to test it we compare the 2012 and 2014 surveys. This hypothesis is fully confirmed. From 2012 to 2014, the only period in the entire monitoring, the regressions indicate the increase in all pride estimates except two and a time of faster change than any before it. The two-year increase in pride is stronger than the nine-year increase found in the previous 2003–2012 period (or almost as strong, in the case of the armed forces). Thus, the pride variables demonstrated the same generalized response to patriotic mobilization as the response of other social attitudes described in the literature (Rogov Reference Rogov2015, Levinson and Goncharov Reference Levinson and Goncharov2015).

To test hypothesis H3, concerning the post-Crimea dynamics of national pride, we compare the 2014 and 2015 surveys, and this hypothesis is mostly confirmed. First, unlike in the preceding period of patriotic euphoria, the main tendency is pride stagnation or deterioration. Second, pride in the armed forces kept increasing—in line with continuing geopolitical activities of the Russian state and its coverage by the state-controlled media. Third, pride in the economy decreased—in line with the Russian economic crisis launched by the collapse of oil prices and the Russian currency rate at the end of 2014. It is worth mentioning that pride in economy proved itself, a very sensitive indicator of the real economic situation at the previous period of monitoring as well. The timing of the 2014 survey overlapped with the beginning of the economic crisis, and pride in the economy remained unchanged even under the pressure of patriotic mobilization. The increase in pride in the armed forces could be viewed as a secondary compensation for the lesser pride in the economy and testing “a new ‘post Crimea’ social contract, in which the people accept economic hardship in return for Russia’s restoration to the ranks of the great powers” (Rutland Reference Rutland2016, 358).

Still, the hypothesized increase in pride in political influence did not occur. This is most likely because the people became aware of the mixed results of Russian activities in southeastern Ukraine and the critical or reserved response from most of the world’s politicians regarding the incorporation of Crimea. Influenced by the information flow from the state-controlled media, people may derogate that response as unjust, but the very fact that it was mostly critical and led to the country’s isolation may inadvertently enter their minds and corresponding media messages.

The unpredicted increase in pride in democracy in 2015 cannot be attributed to pride in the economy, because the latter decreased over that year. During the same period, popular support of the succession of powers and the necessity for public control over the government as an essential part of democracy considerably weakened, and the percentage of those believing that contemporary Russia is democratic grew (Levada Center 2016b). Thus, the paradoxical increase in Russia’s pride in democracy over this year owes much to a redefinition of democracy in the public opinion in such a way that it is not that the objective reality comes closer to a model democracy, but that the subjective model of democracy itself gets modified to better match the current state of affairs. This way, popular demand for pride in democracy is reconciled with the actual authoritarian backlash.

Hypothesis H4 concerning belief in the country’s superiority and its association with national pride postulated the strengthening of this belief and increase in its association with pride, and this hypothesis is mostly confirmed. The belief in Russia’s superiority consistently grew stronger in the time between 1996 and 2014 (especially from 2012 to 2014), and the strength of the association between national pride and belief in superiority grew stronger as well, making national pride increasingly competitive. Competitiveness also grew in most post-socialist countries. For Russia, we ascribed this effect to the post-imperial demand for greatness. In other post-socialist countries, this competitiveness is likely due to the rapid transition from isolation to global openness and European integration inevitably intensifying comparisons to other countries.

This competitiveness may seem akin to chauvinism and gives an impression of strong ties between national pride and hostility towards foreigners. The empirical evidence demonstrates that national pride and belief in national superiority in Russia are indeed positively correlated with various anti-foreigner attitudes. Yet the correlations are consistently weak (around 0.15) and do not increase with time. It means that national pride and even belief in national superiority are distinct from chauvinism.

What was not predicted is the weakening of the belief in superiority (but not the strength of its association with national pride) in 2015. The swift turn from the peak in this belief in 2014 to the remarkable decrease in 2015 indicates that Russians’ mass beliefs, even on such a sensitive issue, can step back. It may be due to the specific grounds on which Russia is considered “a better country than most other countries.” According to public opinion research conducted in 2015, the majority of Russians prefer to live in a country able to provide a high standard of living for its population but not in a militarist superpower (Levada Center 2016b, 34), and the country’s economy deteriorated in 2015 (Gurvich Reference Gurvich2016a). So, the dynamics of belief in Russia’s superiority demonstrates a degree of sensitivity to the objective component of the supply side that cannot be fully overridden with patriotic propaganda.

The dynamics of national pride can vary across countries. Our analysis of the Russian case suggests a specific frame of reference for studying these dynamics in various countries taking into consideration not only the changes in the level of pride as such but also its relative competitiveness operationalized as a correlation with belief in national superiority.

Acknowledgments

This work is the output of a research project implemented as a part of the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (NRU HSE). The authors are grateful to the Levada Center for the survey data on Russia from the ISSP–National Identity datasets and for the 2015 dataset, and to the Institute for Comparative Social Research for the 2014 dataset. Preliminary versions of this paper were presented at the following conferences: “Nation-building and nationalism in today’s Russia” (Tallinn University, April 28–29, 2016), “Europe, Nations, and Insecurity” (Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, June 30–July 2, 2016); “Nationalisms in the post-Soviet space” (The Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, Moscow, October 31–November 2, 2016), and the April 18th conference on economic and social development (National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, April 11–14, 2017). The authors are grateful to the conference organizers and all the participants who discussed the paper for their valuable feedback.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2018.18