The Priory of Saint Mary of Bethlehem was established in 1247 as an outpost of the mother church in Palestine and lay just to the north of the walls of the City of London on land donated by Simon FitzMary. Like many religious communities, the Priory cared for the sick and by 1400 had come to specialise in the care of the mentally ill. On dissolution of the monasteries the Priory became the property of the Crown and one of the five ‘Royal Hospitals’, with Saint Bartholomew's, Saint Thomas’, Bridewell and Christ's Hospital. In 1546 the Lord Mayor of London, Sir John Gresham, petitioned the Crown to allow the administration of Bethlem to pass to the City; this was granted.

The Priory was accommodated in dilapidated buildings and in 1674 the authorities sought a new building. They engaged Robert Hooke to prepare plans. Professor of Geometry at Gresham College and curator of experiments to the Royal Society, Hooke had worked on major buildings with Wren and Hawksmoor (including the Monument) and had himself designed the Royal College of Physicians. Most recently he had surveyed a part of London after it had been destroyed by the fire of 1666.

The new hospital was designed to accommodate 136 patients on two floors, with equal provision for men and women. The site backed onto London Wall close to the church of All Hallows. Hooke adopted a single-pile method of construction to ensure good ventilation. This choice led to a long narrow building. He combined the monastic layout of a cell for each patient with a broad corridor similar to the galleries of grand houses. Each cell had a small barred window facing south with no glazing. The galleries faced north and were glazed. The last in Hogarth's series of paintings A Rake's Progress (‘In the Madhouse’) shows how the galleries were used. In creating the ‘gallery ward’, Hooke had introduced an arrangement that was to be used in the design of mental hospitals for more than 200 years.

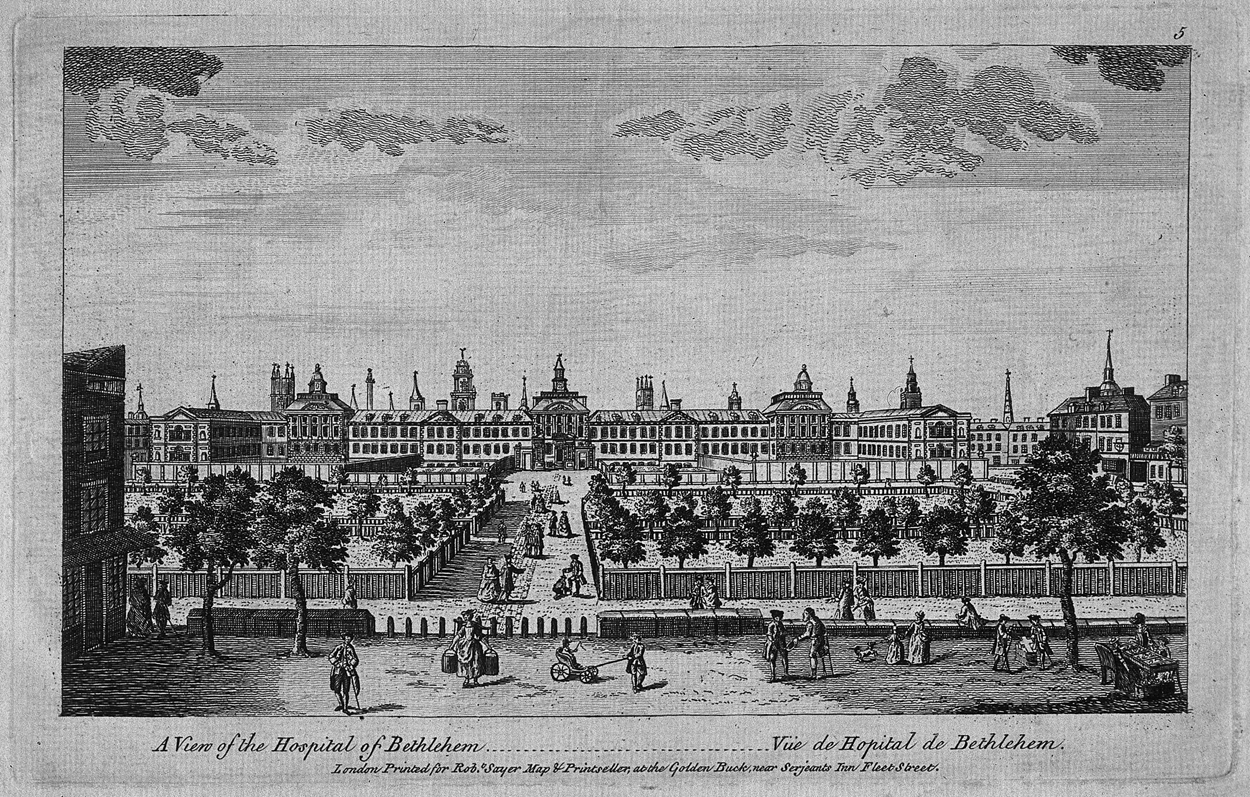

Externally, the building was in the baroque style and almost 600 feet in length. The galleries ran the full length of the building but were interrupted by grills. The central administrative block and the end pavilions were faced in stone and were advanced. The building was decorated with pilasters, balustrades, viewing platforms, swags and cupolas, giving an impression of considerable grandeur reminiscent of a palace; this gave rise to mocking comments comparing the hospital to the Palace of Versailles and questioning whether this was a wise provision for the accommodation of lunatics. Statues of ‘raving and melancholy madness’, by the Danish sculptor Cibber, stood on top of the gate posts, announcing the building's purpose.

Between 1723 and 1735 wings in the Palladian style were added at each end of the building. These double-banked wards were less satisfactory than those opening onto a gallery. Figure 1 shows the enlarged hospital with, in the background, the towers and spires of new City churches designed by Wren and his associates. As time went by the building suffered from neglect and from the marshy ground on which it stood. After much negotiation and a subsidy from the government the hospital moved to a new building at St George's Fields, Lambeth, in 1815. The new hospital, a part of which is now the Imperial War Museum, was remarkably like the one it replaced.

Fig. 1 Bethlem Hospital (c. 1740). Wellcome Collection, (CC BY 4.0).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.