Introduction

Young adults are identified as a vulnerable group who are at increased risk of suicide by the Department of Health’s Connecting for Life – Ireland’s National Strategy to Reduce Suicide 2015–2020 (CfL). The majority of third-level students fall within this group.

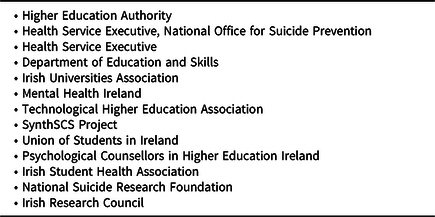

The Higher Education Authority (HEA) has a statutory responsibility for the effective governance and regulation of higher education institutions and the higher education system in Ireland (HEA, 2021). One of the HEA commitments to the CfL strategy was Goal 3.3.3 to develop national guidance for higher education in relation to suicide risk and critical incident response (Department of Health, 2015). In order to fulfil that commitment in 2018, the HEA formed a Connecting for Life working group (HEA CfL) in 2018. Members of the working group as shown in Table 1 were drawn from a cross section of key stakeholders.

Table 1. Higher education authority connecting for life working group

In September 2019, the SynthSCS Project presented the preliminary findings from a scoping review of international best practice to the CfL working group. It was agreed that the SynthSCS project’s research positioned them well within the field of knowledge and resulted in the working group’s request they would draft the National Framework for Student Mental Health and Suicide Prevention in Higher Education.

Context of student mental health

Higher education in Ireland is provided by universities, technological universities, institutes of technology, colleges of education, and other higher education institutes, with populations ranging from 1000 to 30 000 students. A high proportion of school leavers enter higher education in Ireland. There was an increase of over 500% between 1960 and 2010 (Hyland, Reference Hyland2011) and in recent years that trend has continued. Recent figures show that there are 235 697 students enrolled across the higher education system (HEA, 2021).

Over the past decade, surveys of young adults have shown an increase in mental health problems (Dooley & Fitzgerald, Reference Dooley and Fitzgerald2012; Dooley et al. Reference Dooley, O’Connor, Fitzgerald and O’Reilly2019). This is also evident in the numbers of students seeking support services for mental health problems (AHEAD, 2019). While concern for student mental health increases, it remains that the majority of students cope well in higher education, but some groups and demographics do not. The identified factors that may increase a student’s risk of developing mental health difficulties, whilst in higher education include exam and assignment stress; transitions into and out of higher education; financial concerns; balancing paid jobs and academic work; social tensions with family, friends, and relationships; social media; and broader geopolitical concerns (Universities UK, 2018; Dooley et al. Reference Dooley, O’Connor, Fitzgerald and O’Reilly2019).

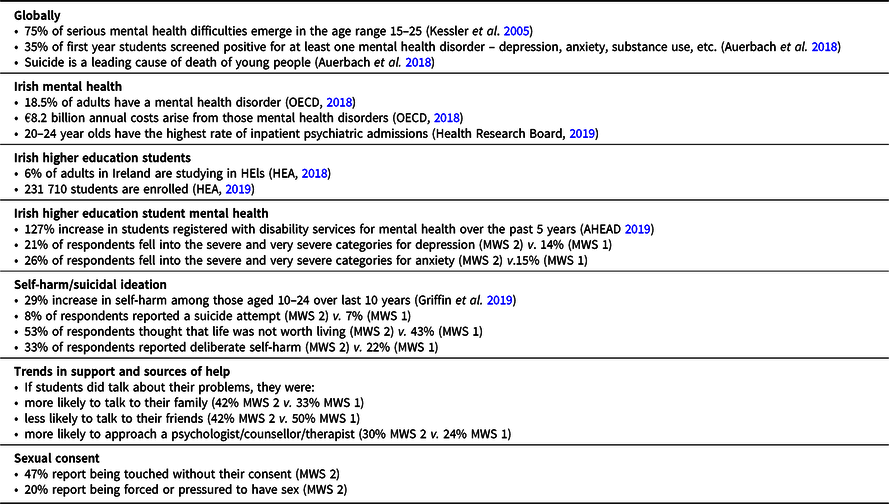

Present policy aims to increase access and widen participation leading to a student population that is more diverse and an increase in students from underrepresented groups. Some groups of students are at greater risk of experiencing mental health difficulties these groups include LGBTQ+; international students; asylum seekers and refugees; ethnic minorities; students that experienced trauma; distance learners; first generation; mature students; and those from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds (Dooley et al. Reference Dooley, O’Connor, Fitzgerald and O’Reilly2019). Students at increased risk of suicide include those who self-harm; those who have been bereaved by suicide; those who have existing health or psychological conditions or difficulties; and those who have a history of drug or alcohol misuse (Universities UK, 2018). Table 2 shows data on student mental health reported on a global scale (Auerbach et al. Reference Auerbach, Mortier, Bruffaerts, Alonso, Benjet, Cuijpers, Demyttenaere, Ebert, Green, Hasking, Murray, Nock, Pinder-Amaker, Sampson, Stein, Vilagut, Zaslavsky and Kessler2018), Irish mental health from a European perspective (OECD, 2018), the high number of students in Ireland (HEA, 2018, 2019), and of the challenges to student mental health in Ireland (Dooley & Fitzgerald, Reference Dooley and Fitzgerald2012; AHEAD, 2019; Dooley et al. Reference Dooley, O’Connor, Fitzgerald and O’Reilly2019). It is evident that young people in Ireland are struggling with mental health (Dooley et al. Reference Dooley, O’Connor, Fitzgerald and O’Reilly2019; Union of Students Ireland, 2019) as is the case internationally. Globally, the demand for mental health support in higher education far exceeds the resources available (Auerbach et al. Reference Auerbach, Mortier, Bruffaerts, Alonso, Benjet, Cuijpers, Demyttenaere, Ebert, Green, Hasking, Murray, Nock, Pinder-Amaker, Sampson, Stein, Vilagut, Zaslavsky and Kessler2018). Over the last 5 years in Ireland, there has been a 127% increase in students registered with disability services for mental health conditions (AHEAD, 2019).

Table 2. Global and national statistic on mental health, young people and students

Original source Numbers at a glance: National Student Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Framework (Fox et al. Reference Fox, Byrne and Surdey2020: 7).

HEA, Higher Education Authority; HEI, Higher Education Institute; HRB, Health Research Board; MWS 1, My World Survey 1 (2012); MWS 2, My World Survey 2 (2019); NSRF, Nation Suicide Research Foundation; OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; WHO, World Health Organisation.

The current support services available for students on campus include counselling, access, academic help centers, disability services, health centers, students’ unions, chaplaincy, and careers service. While mental health first responder resources on campus can include any staff in a student-facing role, the increasing demand for professional supports for student mental health is largely provided by student counselling services, disability support services, and student health centers.

Developing the framework

Scoping review

The literature reviewed for this study looked at how student mental health and suicide prevention is addressed in Ireland and internationally. The search terms and key words included: student mental health, student wellbeing, institution student mental health supports, higher education mental health policy, suicide prevention in higher education, and national student mental health policy.

The search was limited to literature published within the last 15 years, in the English language, on student mental health in the higher education/third level/university sector. A systematic database search was completed of EBSCO, Behavioural and Social Sciences, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search of gray literature included government policy documents, including the Department of Health, the Department of Education and other national and international policy documents relating to higher education, mental health, and suicide prevention.

A critical review and analysis of the literature provided the building blocks for the Framework by providing an evidence base and guidelines for policy and practice. The scoping review found empirically supported models of practice from other countries where extensive work had been done or was under way in the relevant areas, including the Jed Foundation based in the USA, the Canadian Post-Secondary Mental Health Guide, the Under the Radar report from Orygen in Australia, Stepchange Mentally Healthy Universities in the UK. These recommended that a whole system approach is needed to address student mental health. Suicide prevention and mental health needs to be integrated through change at all levels, ingrained into the campus culture, decision-making, and requires participation of all stakeholders across the whole sector.

Process

The Framework was the product of the HEA CfL working group, a collaborative cross discipline/sector team that included: health professionals, government representative’s, policy makers, community organizations, researchers, students, educators, and clinicians.

The SynthSCS project presented to the HEA CfL Working group on international guidance in higher education suicide prevention in September 2019 and from then began developing the Framework. In October, the team presented a first draft of the document to the working group for review. Two subsequent drafts were presented in November 2019 and January 2020, with reviews then incorporated. The authors also developed an implementation guide, to support higher education institutions in implementing the guidance, complete with links to resources and tools. The final draft and implementation guide was prepared for consultation with stakeholders.

Consultation event

The HEA CfL developed a consultation plan that included groups in the education and health sectors, including the HSE National Office for Suicide Prevention, the Health Service Executive’s Mental Health Division, the USI, Psychological Counsellors in Higher Education Ireland; Irish Student Health Association; National Suicide Research Foundation, Irish Universities Association, the Technological Higher Education Association, Mental Health Ireland, the Irish Research Council, the Department of Education and Skills, the Disability Advisors Working Network. The draft guidance and implementation plan was circulated to those groups for review ahead of a national consultation day.

The Consultation Seminar ‘Mental Health and Suicide Prevention in Higher Education: towards a National Framework’ happened in March 2020 at University College Dublin. The event included presentations from higher education leaders in Ireland and the UK on their research and implementation projects in the area of student mental health. The seminar invited participation by key stakeholders including institutional leaders, researchers, practitioners, academics, and international experts to advise on the draft.

Two specific consultations with students were planned at the end of March and the end of April 2020 before finalizing the Framework. These consultations were led by USI and the HEA CfL subgroup.

Students representatives from HEI’s across Ireland attended and provided feedback.

Feedback was collated from the consultations and themes representing the whole sector were incorporated.

Examples of feedback included:

-

resources/online supports needed for non-traditional students (first generation, international, minority).

-

the economic case for investing in student mental health was highlighted.

-

feedback on how health/mental health services can collaborate.

-

communication and media guidelines were suggested.

-

importance of clear definitions of positive/negative mental health.

The final document was presented to the HEA CfL working group and forwarded to copywriters and designers.

Framework format

The framework was developed with the following format:

Chapter 1, Mental health in Irish higher education: describes the background on why Ireland needs a National Student Mental Health & Suicide Prevention Framework.

Chapter 2, International practice in student mental health and suicide prevention: an overview of what other countries are doing and what can be learned and applied in an Irish context.

Chapter 3, National Student Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Framework for Ireland: details the nine themes, aligned with actions.

Implementation Guide: detailed steps and resources for HEIs to implement the recommendations of the Framework.

The Framework

This Framework is Ireland’s first national approach to address student mental health and suicide prevention. The Framework will help higher education institutes identify where further improvements for student mental health are needed, provide good practice guidance and resources, and help to standardize approaches across the country.

The Framework, as shown in Fig. 1, has nine interconnected themes. As discussed above, developing a whole system collaborative approach for student mental health and suicide prevention is not the responsibility of a single department nor is it the case for one theme. The nine interconnected themes are lead, collaborate, educate, engage, identify, support, respond, transition, and improve, and they must be implemented together to ensure continued improvements in whole system support for student mental health and suicide prevention.

Figure 1. National Framework for Student Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Original source: Fox et al. (Reference Fox, Byrne and Surdey2020: 22) National Student Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Framework.

Progress in student mental health and suicide prevention will only happen if prioritised at a national, sectoral, and institutional levels – through policy and strategy, that is student-centered and championed by strong leadership. HEIs need a creative and inclusive approach to student mental health and suicide prevention. Students and staff should be involved at every stage of the journey to improve mental health outcomes. Strong partnerships need to be embedded throughout the institution as well as with the HSE, local and national authorities, with NGOs, and the wider community.

Education and training are key to an improved understanding of and attitudes to mental health and suicide prevention. HEIs need to ensure that all campus members are trained in mental health literacy and suicide awareness so that they can identify signs of psychological distress and direct vulnerable students to appropriate resources. Student well-being needs to be nurtured through the development of community connectedness, purpose, engagement, and belonging. Institutional culture should reflect diversity, inclusivity, and compassion.

HEIs need to take a proactive stance to identify students who are at risk of mental health problems as well as promoting mental health awareness for all students and all front facing staff. Provide students with accessible and well-resourced mental health support. Support services need to be safe, inclusive, and culturally appropriate to all students. HEIs need to have a crisis response or critical incident plan that is accessible to the institution as a whole. The plan should include clear responding protocols for varying levels of crisis and effectively communicated to the whole institution.

Higher education represents a series of transitions for students, and it is vital that institutions have supports in place for pre-entry, induction, reorientation for students who have spent time away and outduction for final year students. Supports and interventions need to be in place for students who are more vulnerable during transitions such as international students, students with existing mental health issues, students with disabilities, students from ethnic minorities, those who identify as LGBTQ+, and others. A whole system response requires starting with a baseline needs assessment and evaluation of current practices. The frequent collection, evaluation, and strategic auditing of data are vital to ensure policies and interventions remain effective and allow prompt action to be taken to improve student mental health outcomes.

Implementation of the Framework

The National Student Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Framework was launched on World Mental Health day 10th October 2020. The Framework was developed to fulfil the HEAs obligation to the CfL strategy to develop national-level policy for suicide prevention in higher education.

The Framework was launched during the COVID-19 global pandemic a challenging time for the staff and students in higher education. The HEA CfL working group has continued to meet and are considering ways to incorporate institutional leadership engagement and support for the Framework.

Providing evidence-based CPD for student services staff is also recommendation of the Framework. Beginning in late 2020, the HEA and NOSP supported 300 student counselling service staff across 25 HEI’s in Ireland in completing Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) training. CAMS is an evidence-based therapeutic intervention that encourages a collaborative highly interactive assessment process and treatment plan.

Also, in development is an updated, online training provided by student counselling services to HEI staff on Identifying and Responding to Distressed and at Risk Students. The new version of training will increase accessibility and reach more HEI staff and in turn develop a campus culture that supports student mental health and suicide prevention.

Embedding well-being into required learning spaces is also recommended by the Framework and the USI in collaboration with the National Forum of Teaching and Learning produced a report Embedding well-being across the curriculum in higher education (Byrne & Surdey, Reference Byrne and Surdey2021).

Another implemented recommendation is the collaborative keyword partnership between the free 24-hour text line 50808 and HEI’s in Ireland. The 50808 crisis text line serves over 200 000 students anonymously, remotely, and is a vital support resource outside of normal office hours and over holiday periods. The keyword partnership allows each HEI to promote their own keyword to open a text conversation with a trained volunteer. As a result, a high level of anonymous data can be shared with the HEI with regard to their students’ use of the service, presenting issue, time of contact, number of escalations to emergency services. These data then inform direction of resources to address significant trends and possible gaps in service provision.

The Framework’s recommendations are further reinforced by new sector-wide required reporting on each HEI’s general progress on their implementation of the National Student Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Framework nine themes.

To improve student mental health and foster student success, this Framework was developed as a whole system approach to building inclusive campus communities that emphasizes de-stigmatization of mental health and seeking support.

There is still much work to be done.

Limitations

The Framework was developed over a short period of time. Continued collaboration and communication will be essential to ensure that the recommendations of the Framework are implemented to support student mental health and suicide prevention. Further research is needed to explore how national-level policies can be integrated to increase effectiveness, for example, linkages between this Framework and related health policies like Sharing the Vision: A Mental Health Policy for Everyone National Mental Health Policy and Services for Ireland 2020–2030 (Department of Health, 2020). Research is also needed to examine the frameworks implementation and what resources, strategies, and supports will be most effective for improving student mental health into the future.

Acknowledgments

When this perspective was developed, the authors Treasa Fox (Project Lead), Dr Deirdre Byrne, and Dr Jessica Surdey were members of the SynthSCS Project from TUS Midlands. The SynthSCS project is part of the larger HEA funded 3SET Project a collaboration between TCD, UCD, and TUSMM on student engagement and success in Irish Higher Education. We thank the participants who contributed to the consultation events and our colleagues from the HEA Connecting for Life Working Group for their inputs and expertise that assisted in the Framework development.

Financial support

The SynthSCS Project is funded by Higher Education Authority Innovation and Transformation Fund 2018.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation. The study discussed in this perspective piece was approved by the ethics committee at Athlone Institute of Technology. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.