INTRODUCTION

Tibial fractures are the third most common fracture seen in the pediatric emergency department (PED). In young children, the majority of these are because of toddler’s fractures (TF), with an incidence of 0.6-2.5 per 1000 emergency department (ED) visits.Reference Shravat, Harrop and Kane 2 , Reference Clancy, Pieterse, Robertson, McGrath and Beattie 3 Despite this frequent occurrence, there is no evidence to support the optimal manner to immobilize this injury, and there is variability in recommended management. Pediatric emergency textbooks suggest initial immobilization in an above-the-knee (AK) circumferential non-weight bearing cast for both confirmed (positive X-ray findings) and presumed (normal initial X-ray) TFs.Reference Fleisher, Ludwig, Henretig, Ruddy and Silverman 4 , Reference Halsey, Finzel and Carrion 5 However, some institutional guidelines endorse the use of other immobilization strategies. 6 Immobilization can have significant health care implications and cause unnecessary burden for patients and their families. Casting has been linked to skin breakdown in up to 27% of children and increased hospital resource use such as return visits to the ED for cast problems and orthopedic follow-up,Reference Sawyer, Ivie and Huff 7 adding to the already present daily challenges of caring for non-ambulatory toddlers.Reference Schuh, Whitlock and Klein 8

Our current understanding of a physician’s approach to TF is mainly based on two recent small single-centre studies, which reported variation in the management of confirmed and presumed TFs.Reference Sapru and Cooper 1 , Reference Schuh, Whitlock and Klein 8 It is not known whether the variation in management is widespread across PEDs or what factors are associated with these variations. Documenting variation is a crucial first step to identify areas in which: 1) evidence is lacking to guide practice that could provide the rationale and acceptable intervention strategies for subsequent clinical trials; and 2) quality improvement efforts should be targeted. Our study addressed knowledge gaps regarding management of confirmed and presumed TFs by characterizing variation in the self-reported practice of Canadian emergency physicians.

Our overall objective was to characterize the management of TF by physicians working in EDs affiliated with the Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) network. Specifically, we sought to 1) determine the variation among PEDs in the management of TF (confirmed and presumed); and 2) determine whether the management of confirmed and presumed TFs was different. Our secondary objective was to assess the association between demographic variables (physician or institution) and immobilization strategies. We hypothesized that there would be significant variation in management strategies for confirmed and presumed TFs across and within Canadian PEDs.

METHODS

Study design and administration

This was a cross-sectional online survey of Canadian physicians who were members of the PERC network, a network of health care professionals, which aims to facilitate multicentre research projects. It comprises 15 Canadian centres (BC Children’s and Women’s Hospital, Alberta Children’s Hospital, Stollery Children’s Hospital, Royal University Hospital, the Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg, Children’s Hospital of Western Ontario, McMaster University Medical Centre, the Hospital for Sick Children, Kingston General Hospital, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Montreal Children’s Hospital, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Ste-Justine, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université Laval, IWK Health Centre, and Janeway Hospital). The PERC network contains 211 members with active email addresses, and survey response rates are typically around 65-75%.Reference Benidir, Lim, Salvadori, Sangha and Poonai 9 , Reference Poonai, Cowie and Davidson 10

The survey was piloted on 10 physicians from five different centres and then revised. The final version was emailed to 211 physicians between April and June 2015 using a modified Dillman’s method, which consisted of an initial email, followed by reminder emails at 1, 3, and 7 weeks. We sent an additional reminder 5 weeks after the initial contact.Reference Hoddinott and Bass 11 The survey used Lime Survey web-based software (Lime Survey Project Team/Carsten Schmitz [2015]). 12 A total of five invitations were emailed to physicians to request their participation in the survey. Basic demographic information (gender, certification, years of practice, the number of shifts worked per month, the institution of the emergency department, availability of cast technician, and the presence of fracture management guidelines in ED) was collected. Two clinical vignettes followed and consisted of two hypothetical scenarios of a toddler presenting with a limp following an injury. The first was a confirmed TF based on a positive radiograph showing a classic TF (tibial oblique spiral fracture of the distal metaphysis), and the second was a presumed TF based on a suspicious history and normal radiographs. Identical multiple-choice questions for each case were then presented to the survey participants to determine their management strategies.

Analyses

Physicians not currently practising in pediatric emergency medicine were excluded from the analyses. We conducted descriptive analyses using proportions and performed Chi-square tests to assess variation among different Canadian EDs for each type of fracture and variation between the two fracture types. For each type of fracture, we calculated the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals to determine the association between the demographic variables and management strategy (using a dichotomous outcome: the most commonly chosen management strategy v. all other strategies). Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.4). We obtained approval for the study from our institutional research ethics board.

RESULTS

Respondents

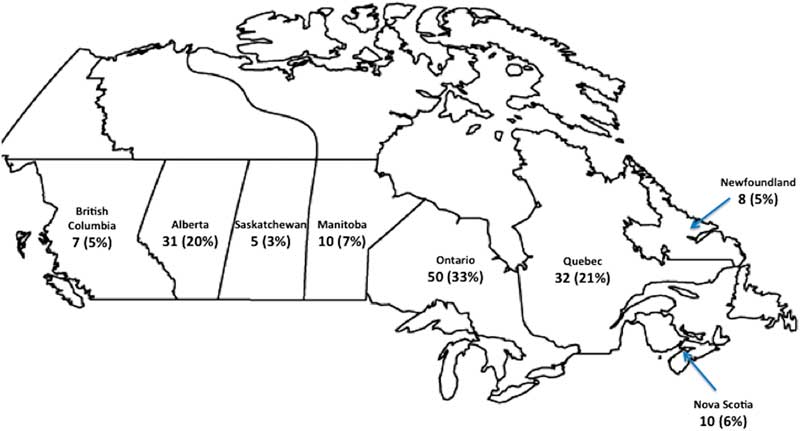

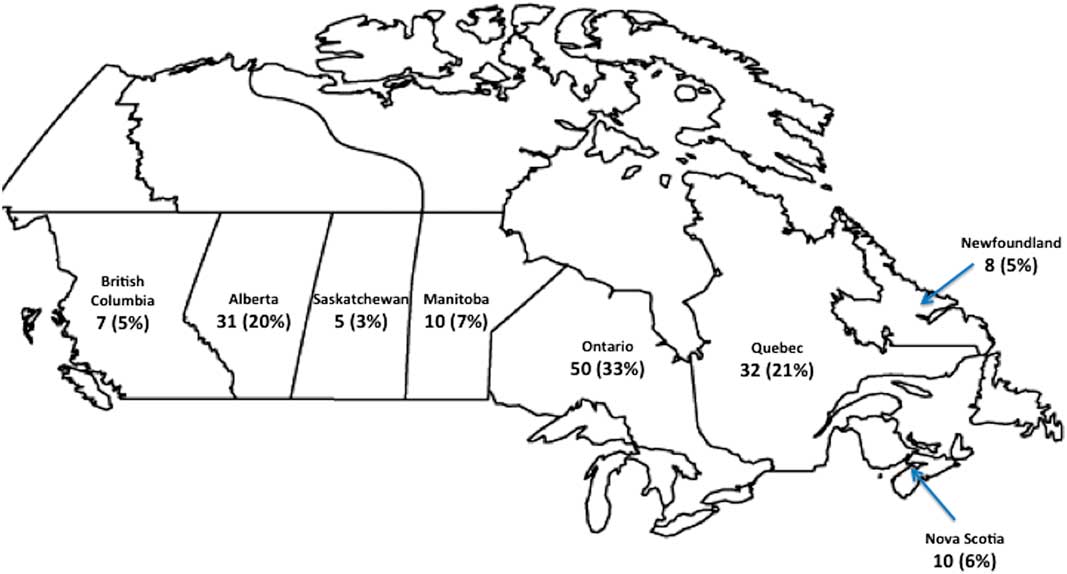

The response rate was 75% (158/211). Five members were excluded because they did not currently practice pediatric emergency medicine. Therefore, 73% (153/211) completed the survey and met the inclusion criteria. Most respondents were certified pediatric emergency physicians (60%) and worked in 14 different PEDs. The demographics of the respondents are provided in Table 1, and their geographic distribution is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Geographic distribution of survey respondents.

Table 1 Demographics of survey respondents (n=153)

CCFP EM=College of Family Physicians of Canada, Emergency Medicine program; FRCP EM=Fellow of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine physicians; PEM=Pediatric Emergency Medicine.

Management strategies

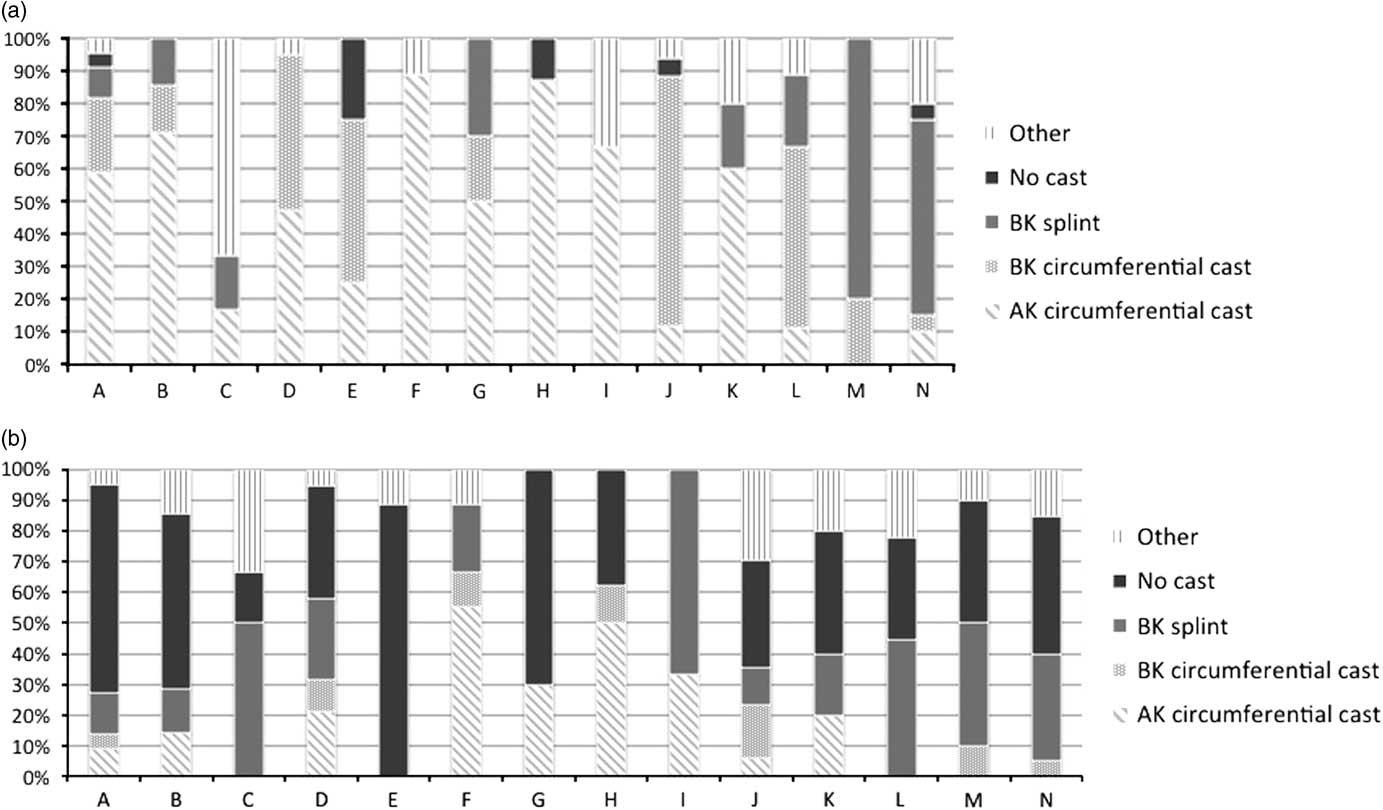

Figure 2 demonstrates the nationwide variation among EDs in the management of TF. Figure 2a outlines the difference in the management of confirmed TF. Seven (50%) centres managed preferentially with an AK circumferential cast, three (21%) centres managed mostly with a below-the-knee (BK) circumferential cast, and two (14%) centres managed with a BK posterior splint. This variation was significant (p<0.001). Figure 2b identifies significant differences in the management of presumed TF (p<0.001). Indeed, eight (57%) centres opted to manage without casting, three (21%) centres predominantly used a BK splint, and two (14%) centres mostly used an AK circumferential cast.

Figure 2 Nationwide variation in management strategies for TFs across Canadian PERC sites. (a) Confirmed TFs; (b) Presumed TFs. Note: The number of respondents for each vignette was 153. The x axis represents each of the 14 PERC centres; the y axis represents the percentage of each management strategy. BK=below the knee; AK=above the knee.

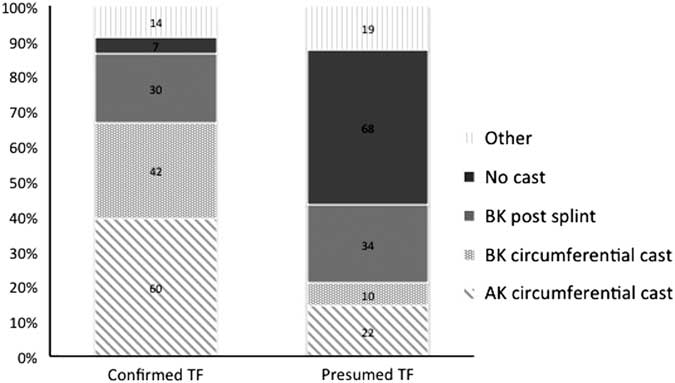

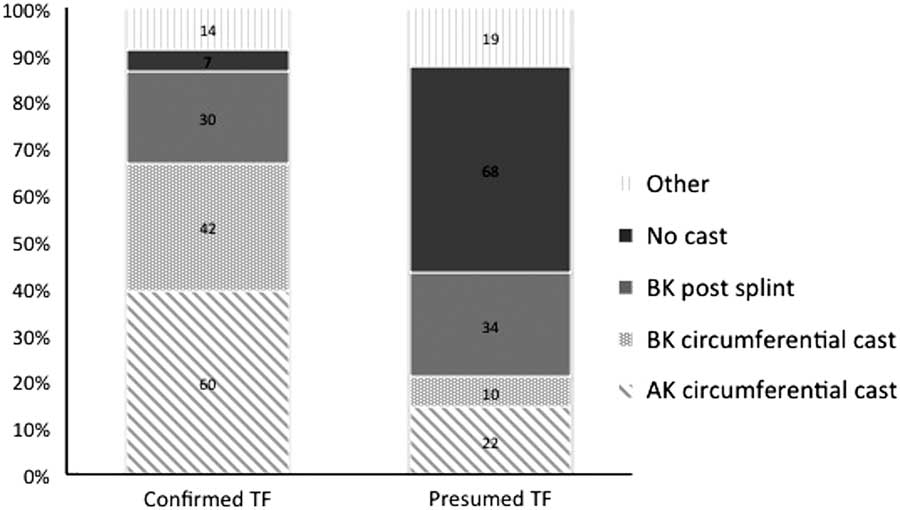

Figure 3 demonstrates variations in overall practice between confirmed and presumed TFs (p<0.001). For confirmed TF, 95% physicians chose to immobilize the injury. The two most frequent immobilization strategies included an AK circumferential cast (39%) and a BK circumferential cast (27%). A minority (20%) chose a BK splint as the ideal management option. For presumed TF, most respondents (44%) chose to manage without casting. If immobilization was done, a BK splint was the most popular (22%), followed by an AK circumferential cast (14%).

Figure 3 Practice variation in management strategies between confirmed and presumed TFs. Note: The number of respondents for each vignette was 153. Within each pattern of the bar graph is the absolute number of respondents who chose that treatment option. The y axis represents the percentage of each management strategy. BK=below the knee; AK=above the knee; post=posterior.

Association of demographics in the management of TF

For confirmed TF, the outcomes were dichotomized to AK casting v. other management strategies (BK circumferential casting, BK posterior splint, no immobilization, and others). Table 2 demonstrates that none of the measured demographic variables studied were associated with the choice of an AK cast, as compared with others.

Table 2 Association of demographic variables with the use of an AK cast for confirmed TF

PEM=pediatric emergency medicine.

Given that the most common management strategy for presumed TF was no cast, the outcomes were dichotomized to no cast v. other management strategies (AK circumferential casting, BK circumferential casting, BK posterior splint, and others). Table 3 shows that there was no association between the demographic factors and decision to treat without casting, as compared with the other modalities.

Table 3 Association of demographic variables with the use of an AK cast for presumed TF

PEM=pediatric emergency medicine.

DISCUSSION

The current survey demonstrates that there was a significant variation in nationwide practice regarding the management of TF. This variation was observed both within each institution and across the country. Although confirmed and presumed TFs are considered to be a spectrum of the same injury, the two differed in terms of management approach. Physician and institutional demographics were not associated with specific immobilization strategies for either injury.

Confirmed TF

A large majority (95%) of physicians agreed that the presence of a fracture line on the initial radiograph should be managed by immobilization with either a cast or splint. An AK circumferential cast was chosen by 39% of respondents, and BK immobilization with a cast or splint was the treatment of choice for 47% of survey participants. Our results are in contrast with that of the traditional pediatric emergency textbook approachReference Fleisher, Ludwig, Henretig, Ruddy and Silverman 4 to manage both presumed and confirmed TFs with an AK cast and with more recently published articles,Reference Sapru and Cooper 1 , Reference Schuh, Whitlock and Klein 8 in which 67%-75% of children with a confirmed TF were immobilized with an AK circumferential cast.

The notion that all pediatric fractures need casting has recently been refuted for other low-risk injuries. In the case of distal radial buckle fractures and suspected Salter-Harris 1 fractures of the distal fibula, randomized controlled trials have shown that healing occurs without casting with low complication rates.Reference Al-Ansari, Howard and Seeto 13 - Reference Plint, Perry and Tsang 21 In addition, family satisfaction was significantly higher in those groups managed without casting or with the most minimally invasive strategy.Reference Boutis, Willan and Babyn 18 Similar to the above-mentioned injuries, TFs are non-displaced fractures, have intact bony cortices, and do not involve the proximal or distal tibial growth plates. Therefore, TF may have a similarly low risk of complications.

Presumed TF

The traditional textbook approachReference Fleisher, Ludwig, Henretig, Ruddy and Silverman 4 for the management of presumed TF does not reflect current practice. In our survey, only 14% of respondents chose to manage this injury with an AK cast. Interestingly, 44% of survey participants chose not to immobilize patients who initially had negative radiographs.

We wondered what could explain the discrepancy between our respondents’ approaches and recommended management and whether diagnostic uncertainty played a role. We question whether radiographs are the ideal imaging modality for the diagnosis of presumed TF. Up to 60% of children in whom TF is suspected have negative initial radiographs.Reference Sapru and Cooper 1 An X-ray follow-up study of patients with presumed TF and negative initial X-rays revealed that only 40% of patients have a periosteal reaction in repeat radiographs 7-10 days later.Reference Halsey, Finzel and Carrion 5 This highlights that 60% of patients with presumed TF are incorrectly diagnosed and unnecessarily immobilized. Although accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and radiation exposure may be limiting factors, magnetic resonance imaging, bone scintigraphy, and computed tomography have been shown to improve the diagnostic accuracy of children with other occult fractures.Reference Boutis, Plint and Stimec 16 , Reference de Zwart, Beeres, Rhemrev, Bartlema and Schipper 22 There is a paucity of literature regarding the diagnostic gold standard to rule in or rule out presumed TF. In the era of point-of-care testing, ultrasonography may prove to be helpful in bridging this diagnostic gap. Point-of-care ultrasonography is a novel tool being used in PEDs for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal injuries and has been useful in identifying occult fractures such as scaphoid, hip, and rib fractures.Reference Tessaro, McGovern, Dickman and Haines 23 - Reference Yıldırım, Unlüer, Vandenberk and Karagöz 28 A case report described its use for diagnosis of TF.Reference Lewis and Logan 29 Future studies comparing the above-mentioned imaging modalities might help better describe the entity of presumed TF and confirm whether a fracture is present.

The lack of clear evidence to guide the management of this injury has forced physicians to adopt their own approach for managing TF. Interestingly, we found that only 22% of centres had institutional fracture guidelines for the management of musculoskeletal injuries. Despite the presence of these guidelines, physicians working within the same centre did not have a homogenous approach for this injury.

The impressive practice variation identified in our study supports the need for a prospective study randomizing the different management strategies to determine functional and quality-of-life-related outcomes in children with both confirmed and suspected TFs. We hypothesize that the traditional management of TF using an AK cast might be unnecessary and place a significant burden on caregivers who are faced with having to carry their toddler for up to 4 weeks. The ultimate goal is to develop guidelines, which would provide a standardized and less invasive approach for the management of these common injuries, thus optimizing health-related outcomes for both patients and their families.

LIMITATIONS

For this study, limitations are inherent to its design. The clinical scenarios were hypothetical, and the answers were subjective and might not predict true clinical management. The clinical scenarios included two patients aged 24 months that might limit generalizability to other age groups. Furthermore, as the study was conducted in only Canadian centres, it might not reflect international differences in management. Our survey participants were physicians who work in tertiary care PEDs that might limit the generalizability to non-academic settings.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study is the first to identify a nationwide variation in the management of TF. This confirms our suspicion that a lack of consensus exists among Canadian pediatric care providers treating these injuries. Additional studies are needed to compare these identified management strategies to assess functional outcomes and family satisfaction to implement standards of care for all children with these injuries.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Patricia Li was funded by a Chercheur-boursier clinicien Junior 1 from the Fonds de la Recherche du Québec–Santé and a New Investigator Salary Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Competing interests: PL is a member of the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, which is supported by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec–Santé. JS and DB have nothing to declare.