Introduction

Sacred shrines are innumerable in Palestine. Nearly everywhere—in the villages, on the mountains, in the valleys, in the fields—do we meet with them. There is hardly a village, however small it may be, which does not honour at least one local saint.Footnote 1

—Ethnographer, Tawfiq Kan‘an (1882–1964)In the late 1920s, Palestinian ethnographer Tawfiq Kan‘an conducted a survey of more than five hundred popular holy sites—natural and man-made outcroppings populating Palestine’s countryside. Recording many sanctuaries now lost to the ongoing Nakba’s radical transformation of the territory since 1948, he preserves a vanishing landscape, both cultural and topographical. Read retrospectively, the author’s wariness of foreign intervention in Palestine casts a long shadow, articulating a fear of “disappearing” cultural practices embedded in a landscape subjected to colonial exploitation and erasure by “European civilization.”Footnote 2 The study of Palestinian sanctuaries, remarks Kan‘an, “brings the reader into direct contact with the daily life and customs of the inhabitants of Palestine” rendering visible the generational transmission of knowledge rooted in Palestinian “practices and rites” upon the land.Footnote 3 Cataloguing the topographical markers of these sanctuaries—the “shrine, tomb, tree, shrub, cave, spring, well, rock [and] stone”—he illuminates the physical and narrative construction of Palestinian space suggestive of cultural anthropologist Keith Basso’s elaboration of “place-making.”Footnote 4 In Basso’s seminal work on spatial construction as learned from the Western Apache, he describes place-making as the act of “doing human history.”Footnote 5 A remark made by an Elder to Basso that “wisdom sits in places” resonates with Palestinian place-worlds, presenting a counter-narrative to the conquest of colonial space and facilitating a paradigm to consider place-making as an enduring narrative practice.Footnote 6 Articulating two modes of disruption, place-making narratives preserve indigenous culture in the face of colonial conquest and unsettle colonial paradigms of spatial belonging and exclusion. Despite the efforts of settler colonial erasure, this interpolative practice has been carried through Palestinian narrative traditions into the present. Raja Shehadeh’s Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape (2007) illustrates an indigenous mode of seeing, creating, and contesting spatial narratives, disclosing the role of place-making in contemporary Palestinian literature.

Indigenous Land Narrative

The [Palestinian] Arab has a vast balance of romance put to his credit very needlessly. He is as disgustingly incapable as most other savages, and no more worth romancing about than Red Indians or Maoris.Footnote 7

—Archeologist, Sir Flinders Petrie (1853–1942)With the earliest materializations of British colonial and Zionist ambitions in Palestine, Palestinian awareness of being the native inhabitants (al-sukkān al-aṣliyyūn) constitutes a core formation of their political consciousness. In 1921, the First Palestinian Delegation to the United Kingdom submitted a memorandum to Winston Churchill declaring that the “Palestinian people will never admit the right of any outside organization to dispossess them of their country.”Footnote 8 Following the 1948 Nakba, and throughout the 1960s and 1970s, scholars such as Fayez Sayegh, Elia Zureik, Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, George Jabbour, and Abdul Wahhab Al Kayyali advanced the analysis of Israel as a settler colonial formation.Footnote 9 In 1982, the founder of the Journal of Palestine Studies, Elias Sanbar, drew an explicit comparison between the settler colonial society of Israel and the United States, where the “only role” of both the Palestinian and the Native American in those societies “[consists] in disappearing.”Footnote 10 And yet, while the comparison of the Palestinian struggle to other indigenous peoples allows for “an understanding of the structures of power and domination that settler states share,” reading the trauma of Palestinian dispossession through the lens of indigeneity is not an uncomplicated proposition.Footnote 11 Not only is the language of indigeneity routinely appropriated by the Zionist project of Jewish “return,” but Palestinian leaders have at times themselves fallen prey to the colonial myth of indigenous erasure and flattening. Even while Yasser Arafat deployed a transnational ideology of decolonization, as early as the 1980s he asserted the “view of indigenous peoples as vulnerable and primitive,” internalizing the perceived failure of indigenous politics to achieve liberation.Footnote 12 Acknowledging and working through this complicated history is integral to a reinvigorated Palestinian engagement with transnational decolonial politics. Although settler colonialism speaks to the structures of power that have and continue to dispossess Palestinians, the political categoryFootnote 13 of indigeneity encompasses the Palestinian history, continuity, and futurity fundamental to liberation. In what Anishinaabe scholar Gerald Vizenor has termed survivance, comparable to the Palestinian concept of ṣumūd (steadfastness), the centering of indigeneity engages “an active sense of presence over absence, deracination, and oblivion.”Footnote 14

Kan‘an’s study of Palestinian sanctuaries captures this cultural practice of survivance by centering the indigenous narratives of a large section of Palestinian society in the late 1920s, the peasantry or fellāḥīn, constituting roughly 80 percent of the population.Footnote 15 Often inhabiting sites providing natural sustenance or protection, Palestinian sanctuaries express and reinforce the fellāḥ’s relationship with the land. The parameters of this relationship are dictated by a walī (saint or guardian) whose spirit inhabits the space. The union of the sacred figure with natural topography in narrative form engenders the specificity of this kind of Palestinian place-making. Cree scholar Stephanie Fitzgerald defines the genre of place-making as “land narrative,” extending Basso’s conception to examine “the vital role contemporary Native narratives of land and place-making play in the regeneration and resurgence of tribal nations and communities.”Footnote 16 Similarly, William Bauer examines how land narrative has been deployed by indigenous peoples “to gain control over the changing historical circumstances” and provide a path for “descendants to follow.”Footnote 17 The Palestinian land narratives recorded by Kan‘an function in complementary ways.

As Salim Tamari suggests in his thorough study of Kan‘an’s contribution to Palestine’s historical and cultural archive, the Palestinian doctor and ethnographer would not have seen his research as part of an indigenous restoration project in line with its current usage. Tawfiq’s ethnographic study—a modernizing project that simultaneously attempts to preserve native traditions—adapts the language and aspired institutionalization of Western ethnography in Palestine. Kan‘an’s study reflects the principles and tensions of the Arab nahda movement, articulating not a “reaction [against] Orientalist discourse, but an attempt to modify that discourse in favor of finding a niche within its confines.”Footnote 18 And yet, what Tamari identifies as Kan‘an’s nativism—“resisting acculturation, privileging one’s own ‘authentic’ ethnic identity, and longing for a return” to indigenous modes of being—is evocative of indigeneity as a political category of resistance.Footnote 19 Although Kan‘an “did not use the term nativism” (or indigeneity) in his study, by reading against the grain of his text we unearth an invaluable archive of the Palestinian land narrative tradition.

A compelling instance of Palestinian land narrative recorded by Kan‘an is the tale of Sittnā el-Ġārah (The Lady of the Laurel Tree). This walīyyah (feminine of walī) was venerated at a laurel tree located east of the village of Beit Nuba, near present day al-Ramlah. During the British invasion of Palestine in 1917, the walīyyah is reported to have appeared “standing on the top of the tree, with a greenish garment, a light head-shawl and a sword in her hand, which dripped with blood” repelling the English troops each time they advanced.Footnote 20 Sittnā el-Ġārah’s story is indicative of this tradition’s responsiveness to contemporary events. As living entities, land narratives are “created and re-created” according to an organizing logic that privileges place, rather than temporal sequence.Footnote 21 As a regenerative form, land narrative looks to the past, present, and future simultaneously, reinforcing traditional practices while responding to “changing historical circumstances.”Footnote 22 The simultaneity of land narrative’s retrospective and prospective gaze articulates indigeneity as both a cultural category of preservation and a political category of change.

The story of Sittnā el-Ġārah also illuminates dangerous missteps in the framing of indigenous struggles by discourses that obscure settler colonial origins. In the case of the “Israel-Palestine conflict,”Footnote 23 this is often achieved by a focus on newsworthy events rather than analyses of settler colonialism’s enduring structure. Marking the distinction between structure and event, Patrick Wolfe exposes the incremental design of settler colonialism—the “elimination of the native”—whether through removal, assimilation, genocide, or some other cumulative form of ethnic cleansing.Footnote 24 A retrospective reading of Sittnā el-Ġārah, contextualizing this tale in the aftermath of the 1917 British invasion, exposes the structural accretion of settler colonial erasure. Beit Nuba (and historic Palestine) passed from Ottoman to British domain as a mandate territory officially in 1922 following the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement in which the British and French conspired to divide and seize Arab territory; the village next fell under Jordanian control following the 1948 war when much of historic Palestine was forcibly annexed by the new state of Israel; finally, Beit Nuba was occupied by Israeli forces in 1967, at which time the village was depopulated, demolished, and replaced by an Israeli national park.Footnote 25 The Ayalon Canada Park sits on the remains of three Palestinian villages—Beit Nuba, Imwas, and Yalu—whose ruins are disguised by signs describing the “ancient buildings, in terms of their Biblical, Roman, Hellenic and Ottoman pasts.”Footnote 26 This effacement illuminates the displacement of indigenous place-making narratives by settler colonial ones through the practice of toponymicide. Footnote 27 De-Arabization through the erasure of Palestinian place-names constitutes a fundamental practice of Israeli settler colonialism epitomized by the state’s “Place-Names Commission,” established in 1949 to hebraicize the terrain.Footnote 28 Palestinian land narratives, like Sittnā el-Ġārah, fundamentally unsettle the foundational myths of settler states to expose indigenous effacement from time and space as intrinsic to settler nation-building.

In discussion with Patrick Wolfe, J. Kēhaulani Kauanui has argued that the occultation of settler colonialism’s enduring structure necessitates the recentering of indigenous narrative in scholarly and cultural discourse. Interventions that “exclusively focus on the settler colonial without any meaningful engagement with the indigenous,” she argues, risk reproducing the very “logic of elimination” they oppose.Footnote 29 Holding settler colonial discourse accountable to indigeneity necessitates the disruption of fundamental Western paradigms and epistemologies of place-making. Indigenous peoples’ assertions of sovereignty “on the grounds of historical continuity, cultural autonomy, original occupancy and territorial grounding” challenge the foundational myths and principles of the Western mono-cultural, mono-national constitutional state.Footnote 30 The exclusivity with which sovereignty and nationhood are articulated in and by settler spaces is fundamentally challenged by indigenous land narratives, whose conceptions of sovereignty and nationhood do not advance Western paradigms or settler interests. Asserting the absence of a national sovereign consciousness among indigenous peoples has, therefore, been a long-held position advanced by settlers as a rationale to seize and “improve” the land inhabited by “uncivilized” natives. Indeed, even while Palestinians were not lacking institutions recognizable to Western observers as stereotypically constitutive practices of national consciousness (including the presence of taxation, land registration, political parties and leadership, hospitals, schools, a railway system, and newspapers) the mandate to improve the land by a people ostensibly more capable of modernization was deployed to justify disenfranchisement. Therefore, while the British did designate Palestine a Class A mandate highly capable of self-governance, the premise that sovereignty may be evaluated and awarded by an external colonizing entity illustrates the detrimental power dynamic under which much of the global south labored throughout the twentieth century.Footnote 31 The very debate, both past and present, over whether Palestinians deserve sovereign rights is an argument which takes as its premise that these rights are not “[vested] in the Palestinians themselves” to begin with.Footnote 32

This progressivizing narrative was adopted by political Zionism, which, while claiming to restore the global Jewish diaspora to an ancient birthright, invoked the colonial invention of terra nullius as a legal pretext for land seizure—that is, the seizure of supposedly uncultivated or uninhabited terrain—as the means of restoring and improving the Holy Land. Either “liberating” the land from the decay of Arab misuse or, conversely, erasing Arab presence on and development of the land entirely—from Zionist leaders of the early twentieth century and Israeli leaders of later decades to the Jewish National Fund (JNF) website todayFootnote 33—Zionist discourse routinely cites the unique capacity of Jewish labor and ingenuity to improve and modernize the land—to make the desert bloom. In the words of JNF official Yosef Weitz, celebrating the organization’s afforestation projects: “Developed agriculture in a civilized country is always accompanied by the forest…. One cannot describe such a society without the forest.”Footnote 34 The JNF’s continued description of pre-1948 Palestine as a “desert-nation”Footnote 35—ostensibly undeveloped and lacking “proper” forests—articulates the continued colonial designation of Palestinians as uncivilized and, therefore, un-nationalized.

Historian Rana Barakat argues that the national struggle in Palestine has typically been framed according to such measures of progress, effectively dictating a narrative of triumph and defeat.Footnote 36 To surpass this triumph-defeat narrative, settler colonial discourse must be held accountable to indigeneity by integrating indigenous modes of national consciousness into its analytical frameworks. Extending the boundaries of national existence beyond a developmental model of European statehood calls the very permanence, inevitability, and rigidity of the settler nation-state into question. This path of interrogation presumes the nation’s dynamism—its unsettledness by nature—in contravention to its one-dimensional framing. The collaborative nature of trans-indigenous scholarship offers alternatives to settler colonial ways of seeing and knowing without mandating a singular path of resistance or mode of theorizing indigenous preservation, sovereignty, and nationhood.Footnote 37 This scholarship advances a radical rethinking of the nation-state and its constitutional and legal frameworks. As Mohawk scholar Audra Simpson argues in “Paths Toward a Mohawk Nation,” examining the multidimensionality of Indigenous nationhood, a theory of nationalism must “[extend] to the aspirations and actions of those collectivities that do not fit the template—those that are non-western, economically integrated and at times, appear to be politically dominated.”Footnote 38 Tawfiq Kan‘an’s account of Palestinian land narrative does “not fit the template” of Western national conscious and its narration, but rather invokes the capacity of nationhood to be a regenerative act of communal becoming, unimpeded by extrinsic preconditions and assessments of national triumph, defeat, or preparedness. An examination of Palestinian land narrative as a distinct mode of national narration exposes this tradition as an enduring regenerative place-centered practice. Place-centered narration, as opposed to the presumably default organizing logic of historical time, illustrates the mobilization of indigeneity as a political category of both preservation and change.

Time-Centered and Place-Centered Narration

Notably disclosing the nation’s embodiment in the novel and newspaper, Benedict Anderson’s seminal intervention on national consciousness examines how the advent of historic time (that “endless chain of cause and effect”) made it possible, in eighteenth-century Europe, to think the nation in the “‘homogeneous empty time’” of the present.Footnote 39 Mikhail Bakhtin describes this shift in temporal perception as provoking “the problem of time in literature … with particular intensity.”Footnote 40 Bakhtin’s elaboration of the literary chronotope—the narrative configuration of space-time—illuminates its subjective nature through his analyses of its diverse constructions across the novel’s genealogy. The paradigm of historical progressive time emerging from eighteenth-century Europe takes on a mythical, rather than scientific, character when its literary genesis and construction are considered. As Hayden White elaborates, the narrative construction of “history” and “literature” (segregated into two distinct fields during this period of European cultural history) underscores the false premise of neutrality attributed to historical time, laboring under its own supreme fictions. And yet, while temporal construction dominates critical literary and historical discourse, “phenomenological [approaches] to representations of the local” disclose comparable power logics at work.Footnote 41 Even Bakhtin, devoting primary attention to “the problem of time” as the “dominant principle in the chronotope,” attends to the power logics of spatial formation.Footnote 42 Examining the adventure time of the ancient Greek romance, for instance, Bakhtin elaborates how the abstract quality of this chronotope necessitates a concerted lack of spatial specificity, constructed in an “abstract expanse of space.”Footnote 43 Any “concretization, of even the most simple and everyday variety,” he contends, “would introduce its own rule-generating force.”Footnote 44 The rule-generating force of spatial-construction is not confined, however, to literary narrative but also reflects and constitutes geopolitical place-making practices—that is, it has material ramifications in the “real” world. In settler colonial contexts, a European chronotope of historical progress has been (and continues to be) utilized as a tool of dispossession.

Adapting Walter Benjamin’s terminology, a “stubborn faith in progress” has been consistently deployed by empire to justify its violent subjugation of indigenous peoples.Footnote 45 Edward Said’s elaboration of Orientalism—that narrative device generating a timeless primitive Arab “East” as a foil for “Western” civilizational advancement—resonates in Mark Rifkin’s exposition of the settler-state’s temporal “singularity.”Footnote 46 For Rifkin, this singularity not only erases indigenous peoples from the historical record, but also constructs a state-centered temporality that fundamentally subverts “native time.” Reema Hammami and Julie Peteet variously examine the Israeli checkpoint, illustrating its deployment as an “artefact of power” in the Israeli infrastructure of stasis (the complex system of checkpoints, permits, road segregation, and roadblocks) that produces the conditions necessary to materialize the myth of Israeli advancement and Palestinian inertia.Footnote 47 Dedicated to developing comparative frameworks, Gary Fields and Brenna Bhandar separately examine the colonial ideology of progress through the lens of “land improvement,” exported from England to its colonial territories and adapted, in Palestine, by the Israeli state.Footnote 48 Bhandar identifies this phenomenon as a “narrative of linear improvement” disseminating the ideology of Western historical progress.Footnote 49

As these scholars suggest, time and space constitute critical sites of struggle, where the assertion of Western progress ostensibly authorizes the colonial manipulation of indigenous space. Given the Nakba of 1948 never ended, the unremitting reverberations of the Palestinian traumatic past in the present have resulted in the advent of collapsed Palestinian time.Footnote 50 The Nakba’s temporal composition as an “eternal present” dictates a continuous state of waiting for return from temporal circularity, or stasis.Footnote 51 In physical space this is embodied by Palestinian refugee camps, which while developing over the past seventy years into ramshackle city quarters, retain the name muḫayyim (camp) to signify temporariness and intended return. As Peteet contends discussing Israeli checkpoints: “Waiting, with the body in prolonged stasis, publicly performs and displays state domination over the minutia of daily life.”Footnote 52 This “prolonged stasis” describing the checkpoint, camp, and more broadly, a collective Palestinian consciousness, displays “state domination over” virtually all aspects of Palestinian existence. However, centralizing the trauma of colonization through a disproportionate emphasis upon the disruption of Palestinian linear time poses distinct drawbacks. As Jodi Byrd, a scholar of the Chickasaw Nation, argues in The Transit of Empire, a conventional emphasis upon:

Vertical interactions continually foreground the arrival of Europeans as the defining event within settler societies, consistently placing horizontal histories of oppression into zero-sum struggles of hegemony and distracting from the complicities of colonialism and the possibilities for anticolonial action that emerge outside and beyond the Manichean allegories that define oppression.Footnote 53

Deploying Edward Said as a bridge between postcolonial scholarship and indigenous knowledge, Byrd suggests the utility of contrapuntal analysis to the field of settler colonial studies. Displacing the centrality of European agency by “bringing indigenous and tribal voices to the fore” facilitates the advancement of analytical frameworks derived from indigenous discourse itself.Footnote 54 Opening Palestinian literary narratives to place-centered analysis expands their conditions of possibility, otherwise ensnared “within the dialectics of genocide” by liberal colonialist rhetoric. According to this Manichean allegory, “Indigenous peoples will [either] die through genocide policies of colonial settler states (thus making room for more open and liberatory societies)” or they will “commit heinous genocides in defense of lands and nations.”Footnote 55 The cruel progress of civilization is rendered inevitable by this paradigm whose aim is the “more open and liberatory” society of the nation-state. Recentering place in Palestinian literary analysis, however, offers one path to complicate the myth of settler colonial progressive time.

Distinguishing between indigenous and colonial place-making as the conscious conception of “land as a meaning-making process” rather than a passively “claimed object,” Seneca scholar Mishuana Goeman advocates a broader use of the geographical framework grammar of place. Footnote 56 Although this epistemology includes the colonial practice of renaming indigenous places, it also encapsulates those power relations that give “authority to some grammars while denying, erasing, or overlaying others.”Footnote 57 The production of settler colonial space is intended to conceal rather than disclose the presence of such grammars, therefore, simulating or appearing as “reality” much like the “comforting seriality” of historical time.Footnote 58 As such, signs describing the ruins of the Palestinian villages in Ayalon Canada Park as ancient buildings not only erase Palestinian presence, but also lull the viewer into compliance to a familiar narrative of “Western” progress, insinuating the Israeli state’s uninterrupted lineage to biblical/Roman/Hellenic civilization. Indigenous land narrative unsettles settler colonial narrative by disrupting the ideology of historical progress and the singularity of Western civilization’s linear space-time. This disruption “upends the state-determined fixity” of the nation-state (that presumed apex of historical progress) exposing it as an “unfinished” project of “unconquered” peoples, and as such, rendering visible the multiplicity of space and time.Footnote 59

By departing from this paradigm, place-centered analysis presents the opportunity to reevaluate common readings of Palestinian narrative, such as its fragmentation, temporal circularity, and stasis often attributed to the traumatic rupturing of Palestinian time, which “[foregrounds] the arrival of Europeans as the defining event within settler societies.”Footnote 60 Although postmodernist readings of Palestinian literary fragmentation and dislocation are evocative of the Palestinian traumatic eviction from time and space, they threaten to curtail the agency of Palestinian cultural producers. Examining Palestinian literary form also from the perspective of placed-centered narration—that is, a cultural practice of land narrative—displaces the premise that time-centered narration constitutes a default organizing logic. The simultaneity of place-centered narration, which “moves out in all directions at once” making it “difficult to imagine a narrative structure capable of capturing this multiplicity,” illuminates the figment of European progressive time and its detrimental ramifications for indigenous peoples.Footnote 61

Mapping Narrative Space in Raja Shehadeh’s Palestinian Walks

Raja Shehadeh’s Palestinian Walks: Notes on a Vanishing Landscape (2007) is divided into seven chapters, each dedicated to a path walked by Shehadeh through Palestine. His work echoes Tawfiq Kan‘an’s fear of a “disappearing” landscape realized to catastrophic effect.Footnote 62 Shehadeh’s narrative is also suggestive of Kan‘an’s modernizing ethos, both authors illustrating their relative cultural capital by writing in English for a broadly foreign (if not explicitly Western) audience. The normalization of a West Bank–centric view of Palestine—that is, of a Palestinian nation isolated from both the inhabitants of Gaza and East Jerusalem as well as the millions of refugees in diaspora—might also be leveled as a legitimate critique of Palestinian Walks’s ability to comprehensively represent Palestinian land narrative and nationhood. And yet, it is just these tensions that make Shehadeh’s work a critical site of analysis evincing the pressures exerted on Palestinian authors to engage the global literary market for legitimization (both of their artistry and political existence) and the physical segregation of Palestinian peoples from one another and the contiguous historical territory. It is precisely in Shehadeh’s land narrative that the continuity of Palestinian nationhood is asserted through praxis.

The sites visited by Shehadeh, like those visited by Kan‘an, suggest the endurance of Palestinian knowledge and cultural practices. In a scene that could have appeared in Kan‘an’s study of Palestinian sanctuaries, Shehadeh describes the maqām (tomb of a saint) of Nabi Aneer, “a small domed structure … built around the tomb, where locals could go to pray and meditate.”Footnote 63 Entering the maqām, Shehadeh realizes he has interrupted someone’s quiet reflection and silently exits. The regeneration of land narrative as a living practice is illustrated both by this instance of continued visitation and by the layering of spatial narratives—that is, the personal accounts of Shehadeh’s walks through Palestine on top of the communal narratives saturating the places he visits.

Another instance of narrative layering occurs while Shehadeh overlooks a valley slightly southwest of Ramallah. His walking companion, Adel, explains that a new military road and the separation wall will expropriate the entire hill. When asked about this soon-to-be inaccessible territory, Adel describes two sanctuaries, Maqām Abū Zaytūn and Maqām Imm Eš-šayḫ, as well as a valley to the west called Wādī El Malāqī, meaning the valley of meetings. This valley, he states, was likely “given this name because it connected many villages from the central hills and the coastal plain.”Footnote 64 Adel’s description of Wādī El Malāqī as a narrative construction of Palestinian place-worlds, resonates with Kan‘an’s complimentary description of Maqām Abū Zaytūn and Maqām Imm Eš-šayḫ:

[Imm Eš-šayḫ] whose shrine lies near [Beitunia, southwest of Ramallah], beheld one day a column of fire reaching from heaven to earth. The same night a reverend šêḫ appeared to her and said that his place lay at the point where the fire touched the earth. Early next morning she hurried to the site, which was known to be absolutely treeless and to her great astonishment found a large olive tree growing there. She called the place êš-šêḫ Abû Zêtûn [Abū Zaytūn ].Footnote 65

The land narratives Shehadeh deploys to map Palestinian space are, then, not synchronic narrations of movement through space, but rather reflect the deep sedimentation of place-making diachronically over deep time. And while the progressive space-time of Israeli settler colonialism threatens Palestinian space-time, the stone outcroppings of the Palestinian sites Shehadeh describes “dotting the land” insinuate a sense of permanence even in their owners’ absence.Footnote 66

Shehadeh’s despair over the political, legal, socio-cultural, economic, environmental, and human ramifications of Palestine’s vanishing landscape is articulated through a narrative act of resistance—that is, as a chronicle of indigenous spaces that reproduces their integral narrative construction. The correlation of Palestinian movement through space and narrative practice is articulated as a collection of seven sarḥāt, or walks. In the process of writing the book, Shehadeh states that he came to experience the writing practice itself as his “eighth journey.”Footnote 67 Sarḥa is an agrarian term describing the act of roaming freely, coming from the verb form meaning “to let the cattle out to pasture early in the morning, leaving them to wander and graze at liberty.”Footnote 68 Shehadeh describes one going on a sarḥa as a person who “wanders aimlessly, not restricted by time and place, going where his spirit takes him to nourish his soul and rejuvenate himself.”Footnote 69 The description of this landed practice is mirrored in the work’s meandering narrative form, with each chapter organized by space rather than time and moving according to the mandates of place-centered narration.

Shehadeh’s first sarḥa begins in 1978 with a walk northwest from Ramallah to Harrasha. As he moves through space, the story is prompted to move back in time to where certain locales evoke stories of Shehadeh’s great uncle, Abu Ameen, who also shared a love for sarḥāt. On this journey Shehadeh discovers the plot cultivated by his great uncle. These agricultural plots are often marked by the presence of quṣūr (plural of qaṣr), “round stone structures dotting the land where farmers kept their produce and slept on the open roof” during the summer months.Footnote 70 Shehadeh identifies Abu Ameen’s qaṣr, literally meaning castle, by corroborating a family legend of the hand-carved stone “throne” (‘arš) sitting outside the building’s entrance. After telling the story of Abu Ameen, who rejected the city life chosen by Shehadeh’s lawyer-grandfather, the narrative moves into the near present. In 2003, Shehadeh leads his nephew Aziz on the same sarḥa through Harrasha to visit the family qaṣr and arš. As the pair return to Ramallah, a city still recovering from the devastation of the 2002 Israeli assault, they pass through a demolished police station where Aziz picks up an undetonated missile and narrowly averts the lethal aftershock of militarized settler colonial violence.

Although shifts across large swaths of time, both within and between chapters, may simulate the temporal insecurity of traumatic Palestinian time, such a reading threatens to overshadow the centrality of place in Shehadeh’s narrative renderings. Place and not time dictates these temporal movements, illustrated by the organization of the text’s chapters into sarḥārt, from “Ramallah to Harrasha,” to “Ramallah to A‘yn Qenya,” “Wadi Qelt to Jericho,” and so on. These sarḥāt are not only deployed as an organizing logic of form but also of the work’s content. Like Ghassan Kanafani’s desert in the famous novella Mā Tabqa La-Kum (1966, in English, All That’s Left to You, 1990), the sarḥāt lend voice to the land itself. As Shehadeh describes the native plant life of Palestine, he uses local place names (“Harrasha,” [small forest]; “Wadi El Wrda,” [valley of the flower]; “A‘yn El Lwza,” [almond spring]) and Palestinian structures like the quṣūr and maqāmāt as spatial identifiers. As such, Shehadeh deploys Palestinian grammars of place in contravention of settler colonial spatial logics, just as his walks circumvent and contest Israeli “security” borders.Footnote 71 The very act of walking “at liberty” in Palestine “not restricted by time or place” constitutes a challenge to the totality of the Israeli settler colonial project, even while Shehadeh’s path is increasingly obstructed by walls, military forces (both Israeli and Palestinian), security zones, and settlements.

Shehadeh relates that he first became conscious of the “language of the hills” as a young lawyer taking up “disputes between landowners who possessed kawasheen [kawāšīn] (certificates of ownership)” for unregistered land whose boundaries were described by physical features in the “language of hill farmers.”Footnote 72 Here he encountered words like baydar (threshing floor) and sabīl (path) as markers of land parameters. Shehadeh employs similar language in his walks, expressing a relationship to space that is rooted in Palestinian knowledge, transmitted communally through living archives and by habitual practice. Relational and cardinal direction lead the reader on a journey through valleys, hills, springs, and villages unfamiliar to internationalized, linear descriptions of the Holy Land—for instance, the pilgrimage route from Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity to Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher. These grammars of place also constitute a distinct contrast to the one and only map rendering of Palestine appearing on the first page of Palestinian Walks. Although the cities mentioned in Shehadeh’s walks appear on this map (Ramallah, Jerusalem, and Jericho), many of the villages, hills, mountains, valleys, and springs constituting the majority of the narrative’s landmarks and destinations are noticeably absent. Why include a map if not to assist the reader in experiencing Shehadeh’s spatial renderings? The answer likely lies in the question itself. Shehadeh’s narrative mapping of Palestinian grammars articulates a relationship to space inconsistent with the scientific accuracy of two-dimensional cartography. Indeed, the modern science of cartography—intersecting neatly with the expansion of colonial empire—articulates a Western proprietary space-time of exploration and domination.

It is no coincidence that the premise of historical time’s neutral authority and the scientific precision of cartography emerge as dominant narrative and visual representations of colonial space-time contemporaneously. The myth of historical time as a “value free, ‘scientific’ view of the past” applies seamlessly to the perception of cartography’s unbiased scientific representations of space.Footnote 73 The ascendency of these representational paradigms as modern disciplines in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe during the height of colonial expansion, however, provokes critical misgivings regarding their credibility as objective mediators. Maps, like narrative representations, are selective depictions that require political and cultural contextualization. The field of critical cartography is attuned to the relationship between “maps and power, both the ways in which states use maps to conquer or control territory and the more subtle ways in which maps erase certain social or political formations and suppress alternative visions of space.”Footnote 74 Maps are visual renderings of these power relations, in Goeman’s words, giving “authority to some grammars [of place] while denying, erasing, or overlaying others.”Footnote 75 Zayde Antrim, who examines the distinction between indigenous mapping traditions in the eastern Mediterranean and the emergence of European cartography in this region, argues that native mapping practices before the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries tended “to stress mobility, overlap and contiguity between the places they depicted” while the mapping practices that followed articulate increasingly “atomizing territorial taxonomies” of property, boundary, and domain.Footnote 76 With the colonial encounter and rise of the nation-state, the spatial narrative advanced by this latter mapping tradition has “severely constrained cartographic and spatial thinking, both within the region and without, making it difficult to visualize other possibilities.”Footnote 77 The two-dimensional map in Palestinian Walks, ineffectual as a complement to Shehadeh’s narrative mapping of space, illuminates this distinction.

From 1871 to 1877, the British- and American-led Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF), whose aim was “generating new knowledge … about the Holy Land,” conducted a massive survey of the territory.Footnote 78 The resulting Survey of Western Palestine is characteristic of colonial mapping, expressing an acute “interest in antiquity—here biblical times—and an emphasis on mathematical accuracy as a means by which local knowledge would be reproduced and made available to an English audience.”Footnote 79 Shehadeh remarks:

Once the ways of these hills were known only to those who used them. They could tell which land was whose and roughly where the borders of each plot lay. Then in 1865 the first preliminary meeting of the Society of the Palestine Exploration Fund … was held in the Jerusalem Chamber of the Palace of Westminster…. Thus began a process that continues to this day of travelers and colonizers who see the land through the prism of the biblical past, overlooking present realities.Footnote 80

The PEF’s Survey of Western Palestine brought the Holy Land under British domain. Through cartography, the English demonstrated their technical skill by reproducing the experience of walking the hills and valleys for their compatriots. As such, even if Palestinians had walked the land for centuries, they had not assimilated their knowledge to a “civilizational standard of progress measured in terms of scientific achievement”; therefore, the British considered their maps closer to the ideal of the “Holy Land” than the land itself—their maps “were Palestine at home in England.”Footnote 81 Disdain for the actual territory and its people was recorded by the PEF cartographers who describe “the land as underutilized,” emphasizing “the negligence of the local people and the Ottoman government with respect to land ownership, cultivation and general stewardship.”Footnote 82 The narrative of land improvement, arising from Britain’s cartographic revolution in the late sixteenth century when widescale mapping facilitated the enclosure of private territory, was advanced by British colonial mapping. Indeed, cartographic expeditions like that of the PEF facilitated the British occupation of Palestine in 1917, set in motion by the Sykes-Picot Agreement between France and Britain, which in 1915 negotiated the annexation of Arab lands on a map signed by both parties. As Shehadeh remarks, the PEF maps were later “the basis for land registration” under the British Mandate for Palestine, a colonial project thinly veiled as “improvement.”Footnote 83 Facilitating ownership by way of representation, cartography was adapted by the Zionist movement in the 1920s–1930s (and reiterated by the state’s “Place-Names Commission” in 1949) intending to “popularize the idea of Palestine as a Hebrew territorial space” through the production of maps “representing Palestine as an area of Jewish settlement absent an Arab presence.” Footnote 84 The visual and linguistic rendering of Palestinian space, first subjugated by cartographic representation and then erased by it, advanced the acquisitive nature of cartography as a path to settler annexation and indigenous erasure.

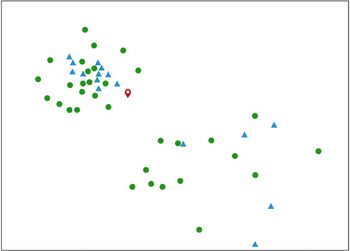

Thinking through Shehadeh’s narrative as a mapping project of local knowledge through the deployment of Palestinian grammars of place provokes a different rendering of space from that produced by European cartography. Shehadeh’s relational description of local, contiguous space resonates with the mapping tradition described by Antrim, stressing interrelation, movement, and connection. Antrim’s inclusion of these indigenous mapping traditions in her survey “[expands] the definition of a map to encompass a wider range of artefacts than would be considered in a scientific approach, some of which may at first seem more like diagrams or paintings than maps.”Footnote 85 This description resonates with Franco Moretti’s usage in Maps, Graphs and Trees: Abstract Models of Literary History, where he endeavors to determine how maps add to our knowledge of literature. Here Moretti deploys maps as diagram-like renderings that disregard scientific specificity in order to focus on “mutual relations.”Footnote 86 Moretti’s application of maps is suggestive of what an alternate visual rendering of Shehadeh’s narrative space might look like. Diagramming Mary Mitford’s Our Village, a work representative of the popular British genre of village stories in the early nineteenth century, Moretti illustrates a narrative movement through space comparable to Shehadeh’s Palestinian Walks. In Mitford’s work, the “narrator leaves the village each time in a different direction, reaches the destination charted … and then turns around and goes home.”Footnote 87 What emerges with the mapping of these destinations (figure 1) is “a little solar system, with the village at the center of the pattern.”Footnote 88 Moretti distinguishes this map from those he produced for another project, Atlas of the European Novel, 1800–1900. Although he “encountered all sorts of shapes,” they tended toward linearity, with the circular pattern of village stories constituting a distinct outlier.Footnote 89 Moretti contends that the shift from a circular to linear pattern was instigated by the British empire’s “dramatic transformation of rural space” through the process of “parliamentary enclosure.”Footnote 90 Mitford’s village stories reverse “the direction of history,” contends Moretti, by presenting her urban readers with the “older, ‘centered’ viewpoint of an unenclosed village,” and the circular movements of the narrator illustrating that genre’s “fundamental chronotope.”Footnote 91 This circular space-time is distinct from the linear chronotope of the European novel as a consolidated statist form. Mitford’s unenclosed circular space-time makes room for “alternative homelands,” whereas the later narration of the space-time of enclosed private properties embodies “the capitulation of local reality to the national center.”Footnote 92 Shehadeh’s sarḥāt, like Mitford’s village walks, evoke the ability to walk freely “not restricted by time and place.”Footnote 93 And yet, a confrontation between Mitford’s spatial rendering and Shehadeh’s illustrates the aftermath of British enclosure in colonial territories and how “the Palestinian landscape [became] part of this lineage of dispossession.”Footnote 94 When we map Shehadeh’s sarḥāt (figure 2), the “little solar system, with the village at the center of the pattern”Footnote 95 does not quite emerge.Footnote 96

Figure 1 A recreation of Moretti’s map/diagram of Mary Mitford’s Our Village, with the village at the center and the destinations of the walks encircling it.

Figure 2 Map/diagram of Shehadeh’s walks. The triangles depict destinations, while the circles denote landmarks and reference points.

The collection of spaces visited and referenced in Shehadeh’s sarḥāt form, instead, an askew figure-eight pattern with Ramallah at its cross-section, illustrating the limitations imposed upon Shehadeh’s movement. Walks that might have otherwise “spread evenly all around” encounter multiple impediments: to the west and south of Ramallah, movement is obstructed by the Israeli “security” border and construction of the separation wall, often cutting deeply into Palestinian land, particularly south of Ramallah, to annex expansive swaths of Palestinian territory; as a strategic agricultural zone, much of the Jordan Valley to the east of Ramallah was converted into Area C (Israeli military controlled) territory through the Oslo process; and to the west, south, and east of Ramallah, Israeli settlements connected by Israeli-only roads and surrounded by “security” buffer zones prohibit Palestinian access. A narrative mapping of the book’s sarḥāt—in its form and content—illustrates an indigenous narration of space as historical and geopolitical mediator.

Despite Shehadeh’s determination to continue walking unimpeded, he finds himself increasingly disoriented, describing the anxiety caused in one instance when losing his way while driving back from the Jordan valley:

I must have taken a wrong turn and found myself in the midst of new settlements and industrial zones, vast open spaces that made me wonder what country I was in…. All of the signposts pointed to Jewish settlements. I could find none of the features that used to guide me on my way: that beautiful cluster of boulders, those cliffs just after the bend that dips into the valley and up again onto the road with the attractive village to the right. “Where am I?” … I began to sweat. Where was I?Footnote 97

Before setting out on the work’s final sarḥa, Shehadeh confronts the dilemma exacerbated by the recent experience of getting lost. While wishing to reach Wadi Dalb through the familiar path of Abu Ameen traced in the first sarḥa, he must instead acknowledge the terrain’s radical transformation. With consternation, he admits a partial defeat by referencing a map:

[This] was not a practice I would have chosen, for it implied submission to others, the makers of the maps, with their ideological biases. I would much rather have exercised the freedom of going by the map inside my head, sign-posted by historical memories and references: this area where Abu Ameen has his qasr [qaṣr], that rock where Jonathan and I stopped and had a talk. That hill over which Penny and I had a memorable walk. But I had no choice. To find a track I could take that was without settlers or practice shooters or army posts or settler bypass roads had become a real challenge.Footnote 98

In Mapping Israel, Mapping Palestine, Jess Bier notes the common rejection of map use by Palestinians. Although partly joking, Bier cites a colleague’s quip: “‘We don’t use maps in Palestine … It’s a small country. We know where we’re going.’”Footnote 99 Part of this rejection is practical. The “calculated unpredictability” of Palestinian travel enforced by roadblocks, checkpoints, settlement construction, and the changing landscape makes a reliance on maps untenable.Footnote 100 However, another principal motivation for this rejection is culturally engrained. Shehadeh rejects the narratives advanced by these maps and their imaginative geographies, which detrimentally shape Palestinian lives by imposing settler colonial inventions upon the geography and its people. Bier’s interviewees, like Shehadeh, stress the “importance of interpersonal relationships, instead of maps, in finding one’s way.”Footnote 101 Shehadeh’s despair at being stripped of this right is palpable. No longer capable of relying on Palestinian knowledge alone, he is forced to consult that object typifying settler colonial space-time so that he may plot a passable route to his destination through a geography transformed by militarized architecture and enclosure. The formerly unimpeded and aimless meandering of the sarḥa is at least partially forced into a target-oriented path.

Despite this concession, Shehadeh contests the ascendancy of colonial cartography through his meandering composition, circumventing the settler state’s militarized boundaries. Shehadeh undermines the remapping and remaking of Palestinian geography in a process Audra Simpson calls “cartography of refusal.”Footnote 102 Describing the Mohawks of Kahnawà:ke, the cartography of refusal takes shape in the people’s present-day labor, invoking their “prior experience of sovereignty and nationhood” and upending the perception that colonization is a condition belonging to a bygone era.Footnote 103 The continuation of indigenous traditions as a form of survivance or sumūd crystallizes not in a canonical rigidity of cultural traditions but rather in a continued regeneration of cultural forms.Footnote 104 Shehadeh’s Palestinian Walks embodies this cartography of refusal. Giving literary form to the Palestinian navigation of settler colonial time and space, Shehadeh’s narrative invokes a kind of transcendent mobility unhindered by the impediments of Israeli settler colonialism (see Maryam Griffin’s forthcoming discussion of Palestinian transit and speculative art).Footnote 105 Shehadeh’s practice of sarḥa takes two forms: the first, a physical activity of walking the countryside, and the second a literary act in which the sarḥa is revitalized as a narrative device and an artistic product. This lived cartography of refusal presents a provocative counterpoint to Edward Said’s elaboration of “imaginative geography”—that colonial invention which represents indigenous space-time, like the “Orient,” with little actual attention paid to the geography and its people.

Conclusion

Shehadeh’s final chapter, an imagined sarḥa, is distinctly evocative of Said’s “imaginative geography.” After divining a route that would allow him to mostly bypass settler obstacles, in part by employing a taxi that would drop him off just past the conspicuously named “Harasha” Israeli settlement, Shehadeh imagines himself setting off on his last sarḥa of the collection.Footnote 106 While temporarily revived by walking in the open hills near Wadi Dalb, Shehadeh is caught off guard by an unexpected companion while approaching the spring of A‘yn Dalb. Sitting by the water’s edge, an Israeli settler calmly packs the tobacco bowl of his water pipe. Shehadeh’s description of the settler, characterized by both a gun resting at his feet and “kind, intelligent eyes,” is purposefully incongruous.Footnote 107 Cautiously engaging the settler in conversation and tempered debate, Shahadeh encourages him to confront his ingrained belief in Israeli exceptionalism while constantly vigilant of the man’s access to “justified”’ violence: “he [the settler] had the authority; he was the law” for “a settler can shoot at a Palestinian with impunity.”Footnote 108 Shehadeh, nonetheless, confronts this threat candidly and poetically: “Your gun is out of place, leaning against that rock. Don’t you think? … This beautiful day and the gun don’t go together.”Footnote 109

As they debate, Shehadeh despairs that their mutual admiration for the landscape is incapable of upending the settler’s allegiance to a violent land narrative detrimental to both the Palestinians as an indigenous people and their native plant life, topography, and ecosystems. Shehadeh outlines Palestinian indigenous rights, based on a historic continuity of inhabitation, as synonymous with the violated rights of the land, mutilated by the occupation’s bulldozers and concrete fortifications. The soldier’s responses, however, are confined by an adamant faith in progress: “Progress is inevitable. You would have done the same as we are doing. Only you lacked the material and technical resources.”Footnote 110 Making little headway, Shehadeh attempts a final appeal: “The way it’s going we’ll end up with a land that is criss-crossed with roads. I have a vision of all of us going around in circles. Whether we call it Israel or Palestine, this land will become one concrete maze.”Footnote 111 The soldier, unable to counter this dystopian prediction, invites Shehadeh to smoke with him. The two sit, then, in silence on the bank of the stream that they “each call by the same name, after the same tree, pronounced in [their] different ways,” A‘yn Dalb and A‘yn Dolev.Footnote 112

Shehadeh’s final imagined sarḥa charts the dangers of a future based on a critical view of the present. This future-oriented focus resonates with the land narrative’s continued regeneration. The prospective gaze is amplified by this sarḥa’s entrance into fantasy. In particular, Shehadeh’s imaginary encounter with the settler and, before that, his dystopian experience of getting lost while driving, resonate with two characteristic modes of speculative fiction: the incursion of an unsettling presence in the space of the familiar and estrangement from familiar space and time. It is no coincidence, then, that a reminiscent encounter appears in Elia Suleiman’s unique take on fantasy in the film The Time That Remains (2009). In the opening scene of this experimental film, Suleiman is a silent witness to estrangement. Picked up at the airport by an Israeli taxi driver, the non-native/native Israeli exhibits increasing anxiety upon entering an unfamiliar landscape in the West Bank. Distraughtly pulling to the side of an empty road, and speaking mostly to himself, the driver laments: “What is this place? … Where do I go now? How do I get home? … Where am I? Where am I?” Suleiman and Shehadeh’s dystopian take on indigenous land narrative exposes the absurd reality that the “imaginative geography” of settler place-making has been unable to conceal and the enduring act of Palestinian land narrative it has been unable to uproot.