In the early 1950s, six feature films dedicated to one of Italy’s most significant events of recent history – the mid-nineteenth-century unification of the peninsula – appeared on Italian screens: Mario Costa’s Cavalcata d’eroi (‘Ride of Heroes’, 1950); Goffredo Alessandrini’s Camicie rosse (‘Red Shirts’, 1952);Footnote 1 Pietro Germi’s Il brigante di Tacca del Lupo (‘The Bandit of Tacca del Lupo’, 1952); Gian Paolo Callegari’s Eran trecento … (La spigolatrice di Sapri) (‘They Were 300’, 1952); Piero Nelli’s La pattuglia sperduta (‘The Lost Patrol’, 1953); and Luchino Visconti’s Senso (1954).Footnote 2

The impetus for the short time span – just four years – during which these films were produced was the posthumous publication in 1949 of Antonio Gramsci’s Il Risorgimento as the third instalment of his 30 Prison Notebooks written between 1929 and 1935.Footnote 3 In particular, the two films that show traces of Gramsci’s revisionary reading of the Risorgimento are La pattuglia sperduta and Senso. Nelli’s film displays the aesthetics of neorealist cinema, being shot with amateur actors and in an ‘almost documentary-like’ style, avoiding ‘the hagiographic approach characteristic of earlier films’;Footnote 4 Goffredo Petrassi’s symphonic score, however, disregards neorealist premisses and instead exhibits sonic vestiges of the forced, heroic style exemplified by the virile, fascist idiom of film music. Whereas La pattuglia sperduta focuses on the First Italian War of Independence of 1848–9, Visconti’s film showcases the third, and last, war of 1866. As the first Italian film shot in Technicolor, the lavish period melodrama is decisively influenced by the aesthetics of nineteenth-century opera, music and literature with its luxurious mise-en-scène, splendid sets, sumptuous costumes and stylized acting. It does not, however, feature a commissioned score from one of the many Italian film music composers of the time but instead uses pre-existing music by Verdi and Bruckner.Footnote 5 The choice, somewhat at odds with what one might expect for a period melodrama from the early 1950s, reveals that Visconti juxtaposes two key works of Verdi and Bruckner as opposed, political instruments, one representing the cause of the Risorgimento and the other the Austrian suppression of Venetia.

Disregarding the historical fact that the Teatro La Fenice was closed from September 1859 until after the Venetian annexation to the Kingdom of Italy in November of 1866,Footnote 6 Senso begins in the middle of a performance of Verdi’s Il trovatore in ‘Spring of 1866. The last months of the Austrian occupation of Venice’.Footnote 7 After Manrico’s famous cabaletta ‘Di quella pira l’orrendo foco’ (‘The horrid flames of that pyre’) towards the end of the third part, the chorus enthusiastically joins in with a call to arms. At the end of the stretta ‘All’armi, all’armi …’ a riot breaks out, with patriotic Venetian audience members throwing red, green and white pamphlets and tricoloured flower bouquets from ‘the gods’ down onto the Austrian officers standing strappingly in the stalls in their white, smart uniforms. They are further exposed to cries of ‘foreigners out of Venice’, ‘General La Marmora is on the march’ and ‘Long live La Marmora. Long live Italy’. This beginning foreshadows the two central ingredients with which Visconti shapes his melodrama of passionate love, conceit, deception and betrayal: an operatic aesthetic and politics.

With Senso, Visconti sought to realize the nineteenth-century, melodramatic opera he was unable to direct in a theatre until shortly after the première of the film at the 15th Venice International Film Festival in late summer of 1954.Footnote 8 In 1952, a year before the preparatory work on Senso, the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino in Florence and the Teatro San Carlo in Naples offered him the opportunity to stage an opera; however, none of these three prospects materialized. Visconti’s first encounter with directorial engagement for the opera stage occurred during the screenwriting process in February 1953, when he and his future assistant director of Senso, Franco Zeffirelli, were both appointed as assistant directors for a production of Il trovatore at La Scala, which was conducted by Antonino Votto and featured Maria Callas as Leonora.Footnote 9

The correlation is evident: in April 1953, diverging from the beginning of Camillo Boito’s novella with the same title written around 1882 and influenced by his work at La Scala, Visconti and his screenwriter on Senso, Suso Cecchi D’Amico, sketched the above-described opening sequence at La Fenice which – pun intended – sets the stage for the operatic, Verdian conception of the remainder of the film.Footnote 10 They dramatized Boito’s novella for the screen in the vein of a Mascagni-style verismo opera on the topics of seduction, jealousy and betrayal. Boito’s rational and collected Livia becomes, in the hands of Cecchi D’Amico and Visconti, a romantically obsessed donna who is eventually scorned. The adored, somewhat stoic male lead from the novella is transformed in the film into an Italian opera stock character, an ‘immature and irresponsible rake who preys upon women for sex and money’.Footnote 11 Inspired by the organization of nineteenth-century opera narratives, Cecchi D’Amico and Visconti further adopted Il trovatore’s somewhat unconventional four-part structure as a paradigm, dividing Senso’s plotline into four distinct sections.Footnote 12 Each of these sections ends with a climactic event. The first part establishes the conflict: Venice is under Austrian occupation, while the Risorgimento movement is about to face the Third Italian War of Independence. Livia is introduced as an aristocratic Venetian siding with the revolutionists, including her cousin, Marquis Roberto Ussoni.Footnote 13 Franz, on the other hand, represents a member of the Austrian occupiers.Footnote 14 Visconti and Cecchi D’Amico situate the first crucial action of the film at a prominent point of the conclusion to Part 1, paralleling Il trovatore. As the first part of the opera closes with Count di Luna challenging Manrico to a duel, so does the La Fenice sequence end with Ussoni issuing the same challenge to Franz. However, the duel does not take place, as the Austrian authorities apprehend Ussoni on the spot. Part 2 is devoted to the first encounter between Livia and Franz and the development of their passionate love affair. This part ends dramatically, with Ussoni’s preparation for defeating the Austrians. He entrusts to Livia a strongbox containing a considerable sum intended to fund the volunteers enlisted for the imminent Battle of Custoza.

Part 3 takes place in the ancestral villa of the Serpieri family in Aldeno, close to Trento,Footnote 15 where Livia and her husband escape to avoid the turmoil of war. Franz secretly visits Livia, who betrays the revolutionists by surrendering the funds reserved for the Venetian militia. Franz (mis-)uses the assets to obtain forged certification from a military surgeon as a means to be discharged from his army duties. By ending Part 3 with a climax – as they had done with Part 2 – Visconti and Cecchi D’Amico thus mirror the conclusion of Part 3 in Il trovatore: Manrico’s highly dramatic cabaletta ‘Di quella pira’ (Part 3, scene ii), as a call to arms, fulfils a similar dramaturgical function as the Battle of Custoza between the Austrians and the Italian Army of the Mincio. The denouement occurs in Part 4 with Livia’s arduous journey to Verona, where she finds Franz drunk, with a prostitute, before denouncing him to an Austrian general. This last part ends with Franz’s execution after having been court-martialled for desertion. Again, the parallel construction of the ending of Senso to the one of Il trovatore is evident: Il trovatore concludes with the guillotining of Manrico and the colpo di teatro of Romani Azucena, who reveals to Count di Luna that he has just ordered the execution of his long-lost brother.

One would reason that after the opening sequence at the Teatro La Fenice Visconti would continue to integrate Verdi’s music into the rest of the film. In a reversal, however, he changes the musical style and dedicates the remaining 100 minutes to Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony (1881–3, revised 1885),Footnote 16 which is ‘generally seen as the pinnacle of the composer’s oeuvre’.Footnote 17 The symphony’s late Romantic aesthetic is hardly associated with Verdi but instead with Wagner, who was comprehensively admired by Bruckner.Footnote 18 If Senso can indeed be compared to an opera, as outlined above, is the model, then, less Verdian and perhaps more Wagnerian?Footnote 19 The film then navigates the anachronistic aesthetic terrain between a visual world of nineteenth-century staging in the style of a Verdi opera, exaggerated verismo acting style and a post-Wagnerian music.

This essay discusses Visconti’s reliance on Verdi’s aesthetic in terms of the narrative, dramaturgical and visual aspects when shaping Senso, and on Bruckner’s grandiose vision regarding the sonic world of the film. Visconti appropriates Bruckner’s music to represent Austrian hegemonic power in a political and religious sense. Bruckner’s devout Catholicism, which is particularly noticeable in the reuse of a memorable motif from the Adagio of his Seventh Symphony in his Te Deum (1881–4) with the added text ‘Non confundar in aeternum’, is deceptive, as Franz epitomizes an all-embracing hedonistic lifestyle. Associated with the Austrian and Venetian aristocracy in Senso, Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony thus embodies music of deceit, as opposed to Verdi’s Il trovatore, which represents the music of idealism. The latter is linked to the liberal bourgeoisie, which invested its hopes in Italy’s unification as a means of establishing a competitive social countermodel to the abiding, anti-mercantile, feudalistic structure propagated by the declining aristocracy. Verdi, as secular music, reflected the new nation’s support for the desired separation of State and Church. Contrary to the bourgeois class and with the advantage of historical distance, Visconti understood Verdi’s music within the context of Senso as indicative of a failed idealism which predicted a revolution that did not take place. Millicent Marcus accordingly argues that in a post-Risorgimento (and also in a post-Fascist and post-Second World War) world, Verdian melodrama no longer functions as a proper warning to its audience.Footnote 20

This premiss about the political ineffectiveness of Verdi’s music after the Second World War leads to the main argument of this article, which examines the correlation between the historic reception of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony and its narrative function in Senso. The appropriation of Bruckner’s symphony for this 1954 Italian film serves as a constant reminder of the consequences brought about not only by the Austrian superpower in northern Italy in the nineteenth century, but also by a series of successive events in the fragile post-war Italian political climate. These included the victory of the centrist Christian Democracy in the 1948 general election at the expense of the defeat of the Left, the eight-year leadership of Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi culminating in the hegemony that the party obtained in the early years of the 1950s, and most importantly the deliberate disregard by the Christian Democrats of the role played by the Resistance in the last years of the Second World War. Influenced by the political situation of the early 1950s, Visconti frequently proposed a ‘double-reading of the film’, referring on the one hand to the poorly executed Italian unification engineered by the ruling class without popular support and on the other hand to the Left, which was pushed to the sidelines in the post-war years by the politically dominant Christian Democracy.Footnote 21 After the Office of Censorship requested that Lux Film cut a sequence that overtly showed Visconti’s reading of the Risorgimento as a historic period controlled by the elite,Footnote 22 two residual narrative elements survived in Senso; they both allude to the failed revolution and the unbroken social superiority of the ruling class. One element is the opening sequence set in the Teatro La Fenice, which examines the parallels with the plot of Il trovatore as a botched revolution of the people against the Spanish rulers in the fifteenth century, and the other is the portrayal of the Risorgimento as the unsuccessful attempt at engineering the unification of Italy from 1848 to 1866 through a true revolution of the people.

A third, and arguably the most important, element is Bruckner’s music, which stresses that the revolution did not take place. The Seventh Symphony, with its – to some extent – rather problematic reception history,Footnote 23 reiterates in Visconti’s subtle audio-visual montage the reality that the reactionary government in Italy would prevail. Since the Seventh Symphony is the leading music in Senso from the sequence after the Teatro La Fenice until the end, this use of Austrian art music highlights that the members of the educated upper class are in charge and not the partisans, patriots, non-aristocrats or middle- to lower-class people. Interpreted through Visconti’s Marxist ideology,Footnote 24 Bruckner is, therefore, an indicator that the hegemony of the elite ultimately remained in place, unchanged and unaltered. The Seventh Symphony is indeed the music of political stagnation; Bruckner is Franz’s music and gradually also becomes Livia’s. This music further symbolizes the survival of Livia’s aristocratic class; as a representative of the Austrian monarchy, it finally opposes the ‘Risorgimento ideal of “movimento popolare”’ and therefore ensures the preservation of this very class ‘as “conquista regia”, free from the true revolutionary threat that participatory democracy would entail’.Footnote 25

Bruckner and the tradition of classical Hollywood film scoring

As much as Visconti’s choice of Bruckner’s music is puzzling from an aesthetic standpoint, its appropriation appears to be an equally courageous decision from a commercial point of view considering the Austrian composer was virtually unknown to a broader classical music audience in Italy and elsewhere in the early 1950s.Footnote 26 Contrary to the situation in Germany and Austria, only a few isolated concerts and radio broadcasts had featured Bruckner’s symphonies in Italy before the release of Senso. Footnote 27 Intended as a commemoration, the first public Italian performance of the Seventh Symphony’s Adagio took place under the baton of Arturo Toscanini in Turin two months after the composer’s passing in October 1896. Within the next 20 years, Bruckner’s symphonies (or selected movements thereof) were presented in a concert setting in Italy only eight times, seventeen times in the interwar period, and eleven times from the end of the Second World War to the release of Senso. This list reveals that the seventh was the most popular of Bruckner’s symphonies with eight performances in the interwar years and five after the Second World War.

As Italian – and presumably also any other non-Austrian or non-German – spectators would essentially have been unfamiliar with Bruckner’s music at the time Senso was released, the Seventh Symphony prompted no extramusical connotation or references to prior listening experiences and therefore functioned as pure film music in the style of any studio-era Hollywood score, such as those written by Max Steiner, Franz Waxman, Erich Wolfgang Korngold or Miklós Rózsa.Footnote 28 Influenced by Bruckner, among others, these composers were deeply indebted to a late Romantic aesthetic and brought this specific musical idiom with them to Hollywood. As perpetuated numerous times by critics of serious music, the contributions to Hollywood of these European-born composers were often regarded as utilitarian, imitative and unoriginal, music that merely accompanied the images.Footnote 29 By giving preference to ‘real’ late Romantic music and having Bruckner descend from Mount Olympus to the level of Steiner, Waxman and Korngold, Visconti enhances the melodramatic intensity of Senso with this ‘absolute music’. He follows – or better, co-creates – a trend defining the preferred musical language for film melodramas of the 1950s, the same genre that Douglas Sirk perfected within the Hollywood studio system.Footnote 30

In Senso, Visconti remained faithful to the concepts of mainstream film music aesthetics from the 1930s to the 1950s. Classical Hollywood film-scoring techniques of the 1940s and 1950s promoted short, memorable motifs which were often used as leitmotifs. To apply this compositional method to Senso, Visconti faced the challenge of tailoring Bruckner’s colossal symphony to the specific circumstances related to the nature of film. How could the Seventh Symphony, with its organic construction (to use a term that Ruth Solie has convincingly contextualized for nineteenth-century music)Footnote 31 and its long-winding melodies – such as the first expositional theme of the Allegro moderato movement modelled along the lines of Wagner’s ‘endless melody’ – be suitably adapted for the screen? In fact, Visconti’s first choice for Senso was not Bruckner but the first theme of the third movement of Brahms’s Third Symphony.Footnote 32 Noted film composer Nino Rota,Footnote 33 who was employed as the film’s music editor, explained to Visconti that up to the moment the second theme enters, the Brahms worked well. From this point on, however, the second theme required expansion.Footnote 34 After informing the director that he was unable to add newly composed material to Brahms, Rota convinced Visconti that Bruckner had written ‘kilometre-long’ passages which were ideally suited to the musical necessities of Senso. Footnote 35 Rota justified his choice by underlining that, ‘If you have sequences which go on for twenty minutes, you must find a composer who doesn’t change the mood for twenty minutes: that’s Bruckner.’Footnote 36 As an experienced film composer, Rota understood that he could only adapt Bruckner for Senso by extrapolating a few memorable motifs from the enormous symphony.Footnote 37 He extracted passages with two principal themes and one subordinate theme from the first movement (Allegro moderato) and two themes from the second movement (Adagio: Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam).Footnote 38 What remained of the immense symphony in the final cut of the film was an abbreviated version, with most cues disregarding the proper chronological order in relation to Bruckner’s intended sequence of musical events (see Table 1).

Table 1 Music Cue List for Senso (Excerpts are from Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony unless otherwise stated)

| Part 1: Teatro La Fenice, Venice | ||||

| Sequence 1: Night at the Teatro La Fenice | ||||

| I.1 | Verdi: Il trovatore | Part 3, scene iv (main-title) | Manrico, Leonora, then Manrico alone; then the armed militia | 0:00:34 |

| I.2 | Verdi: Il trovatore | Part 4, scene i | Ruiz, Leonora | 0:10:17 |

| Part 2: Encounters between Livia and Franz | ||||

| Sequence 2: Night in Venice (Ghetto and fountain) | ||||

| II.1 | Allegro | 1–15 (1st subject, phrase i) | A1 | 0:20:26 |

| II.2 | Adagio | 29–70 | E | 0:22:54 |

| II.3 | Adagio | 75–92 | D1; D2 | 0:28:38 |

| Sequence 3: Livia returns to Franz four days later | ||||

| II.3 | Music continues | (0:29:40) | ||

| II.4 | Adagio | 37–44; 53–92 | E (Franz takes off Livia’s veil) | 0:32:26 |

| Sequence 4: Livia and Franz in the rented room at the Fondamente Nuove | ||||

| II.4 | Music continues | D1; D2 | (0:32:33)(0:34:57) | |

| II.5 | Allegro (Livia cuts off lock for Franz) | 189–209 | B | 0:37:33 |

| Sequence 5: Franz leaves Livia | ||||

| II.6 | Schubert: ‘Der Lindenbaum’ | 0:40:29 | ||

| II.7 | Allegro (Remembering: Livia finds her lock; Franz has left) | 193–7 (development; 2nd subject) | B | 0:43:32 |

| Sequence 6: Livia and Ussoni | ||||

| II.8 | Allegro (Livia returns home) | 189–209 | B | 0:46:18 |

| II.9 | Allegro | 233–76 (dramatic opening: operatic moment) | Avar. | 0:47:38 |

| II.10 | Allegro | 1–25 (1st subject, phrases i and ii) | A1+2 | 0:51:59 |

| Part 3: Livia and Franz at Aldeno | ||||

| Sequence 7: Franz at Aldeno | ||||

| III.1 | Allegro | 185–218 | B | 0:56:29 |

| III.2 | Adagio | 1–61 | D1; D2; E (1:05:51) | 1:02:03 |

| Sequence 8: Livia and Franz at Aldeno | ||||

| III.3 | Adagio | 98–118 | Development material; D2 (1:19:50) | 1:18:02 |

| Sequence 9: Livia betrays the revolution | ||||

| III.3 | Music continues | (1:18:30) | ||

| III.4 | Adagio (attacca): | 177–93 (Ausbruch, cadence). The bars 185–93 represent the Trauermusik for Wagner, here linked with the climactic moment of Livia handing over the money to Franz | D2 (second phrase; cadential, like an exclamation mark; operatic moment; like the destiny is decided) | 1:21:11 |

| III.5 | Allegro | 25–50 (repeat of 1st subject, phrases 1 and 2; bars 42–3: Parsifal quotation: ‘Abendmahlmotiv’) | A1 (var.)+2 (var.) | 1:23:39 |

| Sequence 10: The Battle of Custoza | ||||

| III.6 | Allegro | 391–400 | A1 (interlude between two battle scenes back at Aldeno with Livia) | 1:31:32 |

| III.7 | Allegro | 12–23 | A2 (continuation of interlude at Aldeno) | 1:32:57 |

| Part 4: Verona | ||||

| Sequence 11: Livia’s departure for Verona | ||||

| IV.1 (operatic) | Allegro (attacca): | Montage with music in the style of an operatic overture: 193–210 (= II.5; II.7; II.8; III.1; IV.6 [betrayal]); 233–48 (dramatic, operatic moment [deception] = II.9); 103–22; 123–49 (montage with music in the style of an operatic overture) | B; Avar.; Bvar. (transitional); C | 1:37:08 |

| Sequence 12: Livia in Franz’s flat (end of the delusion) | ||||

| IV.2 | Adagio | 23–9 | D2 (with ominous final chord; stinger; operatic) | 1:40:59 |

| IV.3 | Adagio | 199–210 | D1 (dark) | 1:45:49 |

| IV.4 | Adagio | 37–42 | E (Franz tears off Livia’s veil; see also II.4): reminiscent moment; remembrance of the past | 1:47:15 |

| IV.5 | Adagio | 1–11 | D1(Franz feels sorry for himself; he receives money from women); D2 (Franz realizes that he is a deserter; the end of Austria is close) | 1:50:48 |

| Sequence 13: Livia denounces Franz | ||||

| IV.6 | Allegro | 193–210 | B | 1:56:36 |

| IV.7 | Adagio | 19–29 | D2 (with ominous final chord) | 1:59:01 |

| Sequence 14: Franz’s execution | ||||

| IV.8a | Adagio (attacca): | 179–82 (final credits) | D2 (cadential) | 2:01:48 |

| IV.8b | Allegro | 413–43 (final credits) | A1 (var.) | (2:02:14) |

Key to passages from Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony:

Allegro moderato

Exposition

A1 = First subject, phrase i (bars 1–11). Theme of optimism and certitude.

A2 = First subject, phrase ii (bars 12–20 and 21–4).

A1 (var.) = First subject, phrase iii (bars 25–33).

A2 (var.) = First subject, phrase iv (bars 34–51).

Bvar. = Second subject (bars 103–23, sixth fugue entry). Theme of transition: abandonment, travelling, returning.

C = Third subject (bars 123–64). Fanfare.

Development

B = Based on second subject (bars 185–211).

Avar. = ‘False’ recapitulation (bars 233–76).

Adagio: Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam

D1 = Threnody for Wagner (bars 1–4). Sombre destiny and death; motif foreshadows the tragic end of the illicit love affair.

D2 = ‘Non confundar’ motif (bars 4–9). Decisive; light falls into darkness.

E = Ternary song form (bars 37–60). Idyllic theme.

The Risorgimento in its last months and historical parallels with the years after the Second World War

In order to understand why and how Visconti features Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony as the hegemonic, aural superpower of suppression throughout Senso, a closer look at the historical circumstances of the last months of the Risorgimento and its critical historical reception up to the years immediately after the Second World War is warranted. Visconti sets Livia and Franz’s love affair against the backdrop of the Third Italian War of Independence. This penultimate step to Italy’s unification is much less glorious and heroic than was generally presented during the late nineteenth century up to the late Fascist years. By 1866, Italy had already been a constitutional monarchy for five years; the only two territories not yet annexed to the young Kingdom of Italy were Venetia and Rome. Apart from the South Tyrol, Trieste, Istria and several strips of land along coastal Dalmatia, Venetia was the last region on the Italian peninsula in the hands of the Austrians. The land between the Italian-annexed Lombardy and Venice was heavily protected by the Quadrilatero. This intricate defence system of four forts forming a quadrangle with the garrisons of Peschiera, Mantua, Legnago and Verona – the last of which housed the Austrian army’s headquarters – was made up of the most elaborate structures of fortification in Europe. Owing to the ‘hemmed in or cocooned’ topographical situation behind the Quadrilatero, the core events of the unification ‘largely passed Venice and Venetians by’.Footnote 39

Founded in 1861, the Kingdom of Italy was, at its core, an extension of the Piedmontese Kingdom of Sardinia. It represented an expansion of vastly diverse, annexed, geographic regions of the Italian peninsula in terms of mentality, history, economic development and political conviction. Owing to its divergent formation, the young nation faced political and financial challenges. The cashflow issue was inelegantly solved by raising taxes on the peasants and by secularizing monasteries and churches to payroll the army.Footnote 40 In fact, the Kingdom of Italy had assembled a considerable, yet largely ineffective army which was grafted onto the former five Piedmontese divisions.Footnote 41 This new army, which comprised 350,000 unruly soldiers conscripted from every newly annexed province, from Sicily to Lombardy, symbolized the unstable foundations of the recently established nation. The oversized army was occupied primarily with keeping the several disobedient units of Francesco Bourbon’s restless brigands in the south under control and with patrolling the north-eastern border along Venetia.

On the other hand, and more disturbingly, after Count of Cavour’s untimely demise in 1861, four provisional governments, which were located in two capitals (Turin: 1861–5; Florence: 1865–71), fell before the Piedmontese general Alfonso La Marmora took office in September 1864. Morale in the new kingdom reached a low; between 1861 and 1865, the possibility of an army coup loomed, threatening to topple the House of Savoy. After the collapse of his coalition of conservatives and moderates in 1865,Footnote 42 La Marmora was barely able to form a new government in the aftermath of the October election. At this point in time, his only option to stay in power was to promise the annexation of Venetia and Rome as part of the irredentism project (the wish to ‘redeem’ all Italian-speaking parts into one nation, including the outposts in the Alps and along the Mediterranean). He saw his opportunity in early April of 1866 when the minister president of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck, offered King Victor Emmanuel II the chance to form a coalition with the Kingdom of Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War. As a reward, Prussia would consent to the Kingdom of Italy annexing Venetia. On 24 June 1866, they attempted their first advance against the Austrian Imperial Army and its ally, the Venetian army, at Custoza, which ended in a disastrous outcome for the much larger, yet disorganized, Italian army. Events, however, soon took a turn in favour of a united Italy. Only a few days later, on 3 July, the Austrian Empire was defeated by the Prussians in the Battle of Königgrätz (Sadová, Bohemia). The Austrians were coerced into relocating troops from the Veneto to Vienna, which allowed the Italians to resume their offensive.

After the Italians captured parts of Venetia, the peace treaty – signed in Vienna between Prussia and Austria on 12 October – stipulated that Austria must surrender the whole of Venetia and Mantua to Napoleon III. Derek Beales and Eugenio F. Biagini analysed this moment as Austria’s ‘final admission that Habsburg rule south of the Alps was no longer sustainable and had become a source of weakness rather than strength’ for the monarchy.Footnote 43 Seven days later, the emperor of France ceded Venetia to Italy in exchange for Savoy and Nice. In a referendum on 21 and 22 October 1866, the Venetians overwhelmingly voted for the annexation of Venetia to the Kingdom of Italy. The somewhat unheroic fact is that Italy did not win a battle leading to the annexation of Venetia; rather, the kingdom obtained the territory through fortuitous, historic circumstances involving the Austro-Prussian and Franco-Italian relationships which were, ultimately, unrelated to the Third Italian War of Independence.

In the concluding years of the nineteenth century, historical revisionism began and culminated before the Second World War in a rather bleak narrative that questioned the benefits the unification contributed to the people of the Italian peninsula. Influenced by Vincenzo Cuoco’s study of the 1799 Neapolitan Revolution, the social critic and precursor of Fascism Alfredo Oriani (La lotta politica in Italia (‘The Political Struggle in Italy’), 1892), the liberal Piero Gobetti (Risorgimento senza eroi (‘Risorgimento without Heroes’), 1926) and the liberal, idealist philosopher, historian and politician Benedetto Croce tellingly influenced in turn the interpretations of the Marxist Antonio Gramsci and the neo-Hegelian, idealist philosopher and Fascist politician Giovanni Gentile. Both Gramsci and Gentile read the outcome of the Risorgimento as a failure.Footnote 44 Against Croce’s view of the Risorgimento as the beginning of a national awareness of civic rights and duties, Gramsci and Gentile argued that the unification of Italy was not due to the glorious fight of the Garibaldians for the liberation of the north and south from foreign occupiers, but rather that Garibaldi was a political puppet used by Cavour to shape the unified Italy into the ‘fabric of a constitutional monarchy’ governed by the Savoy dynasty under Victor Emmanuel II.Footnote 45 Gramsci and Gentile interpreted the Risorgimento as a failed popular revolution: despite the idea of trasformismo (a flexible centrist coalition keeping the extreme Right and Left under control), the social structure in the united Italy did not change. The hopes of the bourgeoisie for a more just society and the effacement of class differences were shattered, for the ruling class still had the upper hand and continued ‘securing its own economic and political power’.Footnote 46 The Risorgimento was thus incomplete, and would remain so until the revolution truly occurred. For Gentile, the last stepping stone in the fulfilment of the Risorgimento was Mussolini’s Fascism; for Gramsci, a Marxist revolution. In fact, for Gramsci, the class struggle throughout Italy could only be overcome by the establishment of a socialist or communist government in Italy.

Decisively influenced by Gramsci’s Marxist interpretation of the unresolved Risorgimento, Visconti drew a parallel between the recent events in Fascist Italy during the last years of the Second World War and the first years of the young democracy. He was not alone with his ‘view of the Resistance as a “second” Risorgimento’.Footnote 47 This anti-Fascist narrative found wide support among socialist and communist intellectuals in the post-war years and ‘hinged upon the idea of the Resistance as a national and patriotic war of liberation, supported by the entire populace rallying around the regular troops and partisans’.Footnote 48 According to Angela Dalle Vacche, Visconti wanted to show in Senso that ‘the outcome of the Risorgimento had little to do with the ideal of national unity. It depended, instead, on shrewd political calculations, indifferent to the senseless sacrifice of human lives.’Footnote 49 The partisans, of whom Visconti himself had been a member,Footnote 50 were influenced by the Communist Party and aimed to arrange an official alliance with the Anglo-American commanders, which was refused. The Anglo-American joint forces instead signed an agreement with the Italian army to protect its members from post-war trials in exchange for full support securing German-held territories.Footnote 51 The Resistance movement lost out to the privileged class of army members, not unlike the Garibaldians who, during the Risorgimento, gave in to the ruling class.

Visconti, a member of the Italian Communist Party, was well aware of the parallels between the Risorgimento and the Resistance. He also understood that the agreement between the Italian army and the Anglo-American forces was the foundation for the victory of the centrist Christian Democracy party in the first general election of the young republic in 1948. Bypassing the concept of trasformismo, Prime Minister De Gaspieri formed a cabinet without including any communist or socialist members. The Left, ‘who had fought against Fascism and helped establish the republic’, felt betrayed.Footnote 52 Visconti made this betrayal in Senso fully noticeable through the flooding of the soundtrack with Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony, which ‘becomes the musical presence on the soundtrack’,Footnote 53 as noted by Deborah Crisp and Roger Hillman.

Livia and Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony

Crisp and Hillman further comment that, ‘The film’s action is motivated by the Austrian domination of the Veneto region, and the Italian characters act largely in response to the public and private moves of Austrian characters and institutions.’Footnote 54 This astute observation does, however, not relate the whole story. The film’s central narrative strategy is indebted to the notion that the Austrian domination is primarily expressed through Bruckner’s music. By means of varying moods, the Seventh Symphony – as an emblem of the Austrian supremacy over the north Italians and as an enormously oppressive and overpowering sonic force – provides symbolism regarding Livia’s fixation on Franz, a crucial plotline which constitutes the essential controlling entity of the narrative. At the story’s macrolevel, the inundation of the soundtrack with Bruckner highlights the dominance of the Austrian monarchy over the idealistic, yet disorganized, Italian cause for unification led by the Italian bourgeoisie. At the microlevel, Bruckner’s music supports Franz’s seduction of Livia and his efforts to win her heart to satisfy his own sexual desire. The massive symphony does not, surprisingly, stifle the intimate love story told on screen. On the contrary, it elevates the illicit relationship to monumental proportions: it lifts the story of the two lovers to a higher level, conveying to the audio-viewerFootnote 55 that more is at stake than just the destiny of this dishonest couple, namely the fate of a territory with ambitions for national sovereignty. Livia and Franz are thus representatives of their two larger causes, and each embodies in Senso a pars pro toto.

The narrative trajectory shows how Livia is increasingly led away from her opportunistic Venetian husband, who collaborates with the Austrians, and also from her idealistic cousin, who fights for a unified Italy, and this growing separation results in bringing her – seduced through Bruckner’s music – into closer proximity to her Austrian lover, Franz. In line with her growing lack of interest in the unification of Italy, Livia initiates a strong fixation on Franz. This fixation also underlines Visconti’s invitation for an alternative reading: the Risorgimento as an allegory of the Fascist era and its subsequent demise. This metaphor for the seductive yet dangerous power of Italian Fascism is amplified in Senso through Bruckner’s dominant music: Franz emerges as a symbol of the Fascist delusion that seduced the Italian people, personified here by Livia.Footnote 56 Franz, as an allegory of the Fascist regime, deceives, violates and ultimately betrays her before facing the same destiny as Benito Mussolini did: death through execution.

Visconti enacts this metaphor of the Fascist regime as a seductive lure through the thinly veiled cover of the Risorgimento. In this society, Livia represents the quintessential aristocratic Venetian woman. Contrary to the majority of women on the Italian peninsula in the middle of the nineteenth century, she was not illiterate but was well educated and thus able to advance the cause of Italian unification.Footnote 57An Austrian law issued only within Lombardy and Venetia allowed her, as the landowner of a villa on the terraferma, ‘to vote in local elections by proxy, through a male delegate’: this was in contrast to other parts of Italy, where aristocratic women had no ‘active political rights’.Footnote 58 In all other regards, Livia acts against the set of moral norms expected of a virtuous, exemplary, esteemed and upper-class Venetian woman. She shuns the traditional ‘criteria of female “respectability”’, such as ‘religiosity, obedience to father and husband, and deference to conventional sentimental priorities’.Footnote 59 As is the case with her husband, who closely collaborates with the Austrian occupiers (as indeed many aristocratic Venetians did),Footnote 60 her abandonment of the Italian revolutionaries and her succumbing to the Austrian occupiers are mirrored in her changing statements. At the beginning of the film, she proudly declares to Franz that she is a ‘true Italian’ (at 0:24:24); her patriotic pronouncement is, however, underscored by the music of the enemy, by a passage of the Adagio, and thus comes across as lukewarm. This very passage of the Adagio relates to a somewhat later moment in the film when Franz makes flirtatious advances. During this first encounter with Livia, he hopes that his initial coquettish pleasantry might lead to an intimate love affair. The Adagio does not only announce the success of his seduction but also that Livia is about to betray the revolutionary cause and her wish for a unified Italy. This disloyalty to the greater cause for the sake of her own selfish interest is mirrored towards the end of the film with her denunciation of Franz to the Austrian authorities. She reports to the Austrian General Hauptmann in defeat that she is a Venetian, that is to say a mere subject from a city under Austrian occupation (at 1:55:35). The absence of both Bruckner and Verdi at this point demonstrates that both the eager idealism for a unified Italy and her amorous passion for the Austrian lieutenant have been completely eroded.

Livia’s deliberate disobedience and ruthlessness in taking advantage of her privileged status as an aristocratic member of society make it no coincidence that Visconti closely relates her behaviour to the Seventh Symphony, which depicts Austrian supremacy and aristocracy. Almost without exception, Bruckner’s symphony appears only during sequences in which Livia is present. According to film historian Tomaso Subini, ‘Music underlines the lived dimension of Livia, being the [dimension] of love, [and] not the one of patriotism.’Footnote 61 Indeed, a closer look at the shaping of the film’s narrative reveals that after the opening sequence at the Teatro La Fenice, the plot is almost exclusively related from Livia’s perspective. The audio-viewer never leaves her side, except during the Battle of Custoza – tellingly, the only sequence in the film without music. Following the narrative strategy of Boito’s novella, Visconti reveals the plot from Livia’s point of view as she delivers her personal thoughts and feelings in occasional voiceovers which are generally underscored by Bruckner’s music.Footnote 62 Boito’s first-person narrative by which she conveys her actions and feelings is replicated by the director in the cinematic realm by means of an explicit and operatic language in terms of mise-en-scène, cinematography, sets, costumes, make-up and a highly expressive acting style.

The persistent tension between a nineteenth-century, opulent Italian operatic staging style and a Wagnerian aesthetic expressed through Bruckner’s music remains unresolved throughout the film. The two clashing aesthetic conceptions mirror Livia’s conflicting feelings, as shown by the music. Like an opera singer, she appears to hear the music. This assumption is rooted in the fact that she responds emotionally to Bruckner’s symphony and that her thoughts and actions are guided by it. To use film-music terminology, Bruckner’s music is neither non-diegetic nor metadiegetic, let alone diegetic; nor does it occupy the in-between state of Robynn Stilwell’s ‘fantastical gap’.Footnote 63 From her own, highly subjective point of view, Livia acknowledges the music in the same fashion as Bruckner scholar Ernst Kurth described experiencing the composer’s music. For Kurth and for Livia, the music emerges and originates from energies within; the premisses for such a hearing experience are ‘the pressing psychic impulsive forces within us, which first reach for “matter” by actualizing, through an act of striving, the sensuous perceptibility’.Footnote 64 Adapted to the specific situation in Senso, the Seventh Symphony appears as a megalomanic power demonstration of the Austrian Empire achieved through the music’s ‘acoustic exaltation and augmentation’.Footnote 65 Influenced by this sonic weight, Livia approaches the music with a deeply emotional, devoutly passive attitude which forces her to surrender to the seductive sound of the symphony.Footnote 66 Bruckner’s music is thus used as a ‘spiritual weapon’ to assert Austria’s ‘spiritual superiority’.Footnote 67 In the political realm, Bruckner’s music confirms the hegemonic claim that is linked to an Austrian national consciousness and an urge to erect borders in order to define the ‘Other’, which, of course, is the subjugated Venetia.Footnote 68 In Senso, the Seventh Symphony retains its various designations which had gradually been crystallized through the historical reception of Bruckner’s music during the composer’s life.Footnote 69 Such attributions are based on Bruckner being a devout Catholic and having been predominantly apolitical, facts that Visconti efficaciously borrows to describe astutely the Austrian superpower and Franz.

The Adagio of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony

Three case studies of core sequences with Livia and Franz, featuring Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony, reveal how the music functions as the expression of the inner seductive power that drives Livia into her obsession with Franz. The focus of these case studies is three sequences which include the music from the symphony’s second movement. In the Adagio: Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam (very solemnly and very slowly), Bruckner’s ‘most famous and most admired movement’,Footnote 70 the passionate affair between Livia and Franz evolves from blossoming to complete collapse. Two of the examined sequences are concerned with the rekindling of the clandestine liaison in the ancestral villa at Aldeno and one with the final collapse of the relationship in Franz’s rented flat in Verona, which he cohabits with a young prostitute.

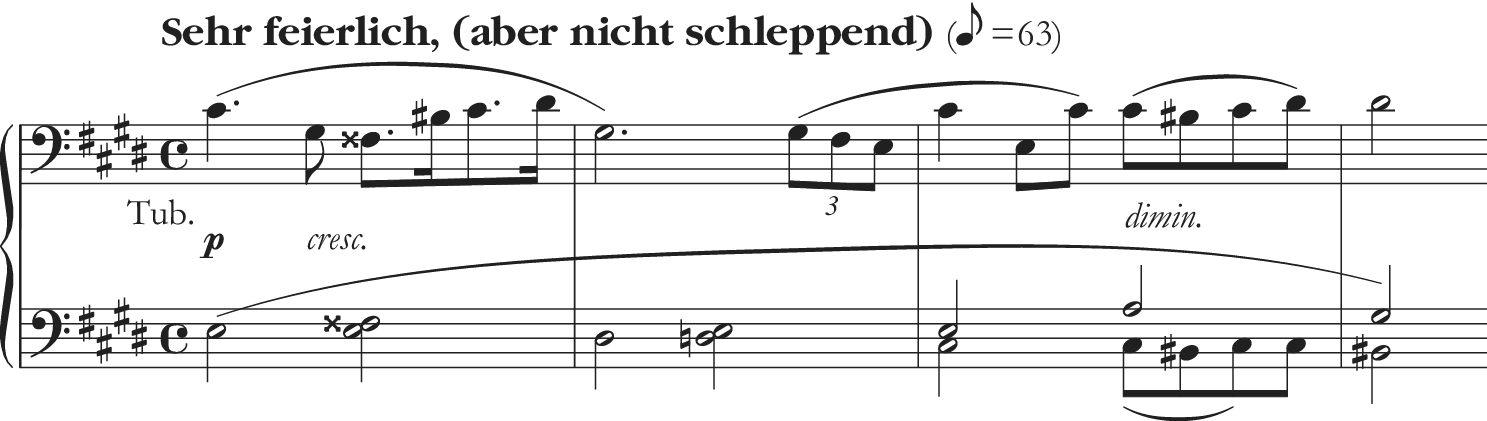

A brief analysis of the Adagio discloses that Bruckner shaped the movement in an ABA1B1A2 rondo form which can also be interpreted as a sonata form, with AB as the exposition, A1B1 as the development, and A2 as the recapitulation with coda.Footnote 71 The A section comprises a theme with two distinct motifs. The first motif is generally regarded as the most Wagnerian-influenced passage in the entire movement (bars 1–4; see Example 1); one reason for this assessment is that Bruckner changed the orchestration of these bars after he learnt of Wagner’s passing in Venice on 13 February 1883.Footnote 72 In the autograph score, Bruckner scratched out the original instrumentation for the first four bars of the Adagio, replacing the trumpets and trombones with four Wagner tubas (first used in the Ring cycle), which Bruckner reportedly intended as an invocation of a threnody for the ‘Master’.Footnote 73 The following bars present a juxtaposing, second motif, confident and promising with its assertive ascending, diatonic gesture (bars 4–9; see Example 2). Bruckner reused and expanded this motif in the final movement of his Te Deum to the final words, ‘non confundar in aeternum’.Footnote 74 The contrasting, elegiac and contemplative theme in the B section is in the dominant key and written in a ternary song form in three periodically shaped eight-bar sections (bars 37–60).

Example 1 Bruckner: Symphony no. 7, Adagio, bars 1–4. Reproduced from: Symphonien von Anton Bruckner, Neue Ausgabe für Klavier zu vier Händen von Otto Singer, 3 (Leipzig: C. F. Peters, n.d.), p. 29. Bruckner’s original tempo marking reads: ‘Sehr feierlich und sehr langsam’.

Example 2 Brucker: Symphony no. 7, Adagio, bars 4–9. Reproduced from: Symphonien von Anton Bruckner, Neue Ausgabe für Klavier zu vier Händen von Otto Singer, 3, p. 29. The slurs and accent markings are Otto Singer’s. Singer also changed Bruckner’s sehr markig to molto marc.

Visconti’s reinterpretation of the two memorable motifs of the Adagio’s A section provides a clue for how to read the recurring sombre death motif and the hopeful ‘non confundar’ motif as a spark for Livia’s impulsive, often irrational actions in Senso. Stephen Parkany interprets the ‘entire movement’ in terms of the ‘associations of the principal motifs’ as ‘a great Trauermusik to Wagner […] combined with a fervent prayer for the salvation of his pagan soul’. According to Parkany, the deeply devout and Catholic Bruckner ultimately aimed to absolve Wagner’s ‘pagan soul’ in the Adagio.Footnote 75 The Adagio’s repurposing in Senso creates a multilayered web of significance. On the one hand, the film offers a forthright homage to Bruckner’s Trauermusik by associating it directly with the place where the ‘venerated Master’ died 17 years after the events take place in Senso. The close correlation between the Trauermusik and Bruckner’s mourning for Wagner infuses the film’s ambience with an overpowering sense of Wagner’s presence, colouring the intimate moments between the illicit couple. On the other hand, the Trauermusik foreshadows the solemn outcome of Livia and Franz’s story. Franz’s demise through execution is thus already inscribed into the story from the first notes of the Trauermusik.

In contrast, the ‘non confundar’ motif bestows Livia, who is misled by Franz, with temporary, yet misguided, clarity in making hasty decisions. Even though it is fairly certain that neither Visconti nor Rota was aware that Bruckner reused this passage in his Te Deum, the haunting characteristics of this motif must have acted for the two as an invitation to place it at key plot moments in the narrative. Presumably motivated by its highly memorable melodic structure, its exposed position in the Adagio and its overtly dramatic contour, Visconti reserves the ‘non confundar’ motif for pivotal moments in Senso to accentuate narrative climaxes. The compositional link between the Adagio and the Te Deum – an Ambrosian hymn that expresses the central creed of the Catholic faith – emphasizes that the final verse, ‘In te, Domine, speravi: non confundar in æternum’ (‘In thee, O Lord, do I put my trust: let me never be put to confusion’Footnote 76) also reverberates in the Adagio, confirming the devotee’s unwavering trust in God. Bruckner, as a devout Catholic, chose a prominent place for the ‘non confundar’ motif that appears towards the end of the movement. Through a masterful control of orchestral textures, the motif continues to swell until it reaches an exalted, almost delirious, climactic moment and thus highlights for the listener with great clarity the central, profound importance of this verse as an emblem for genuine Catholic devotion. In the context of Livia and Franz’s short-lived, stormy affair, the Christian thought turns cynical. With Livia’s adultery opposing all Christian values, the ‘non confundar’ motif assumes an additional, moralizing dimension beyond the significance Visconti may have intended to express with this motif in Senso. It underlines Livia’s complete abandonment of her Catholic faith at the cost of solely relying on her voluptuous desire and narcissistic self-interest. In her altered mental state, she fails to perceive the motif as a deceptive signal and is certain – from a misguided, hardly ethical perspective – that she will do the right thing. What she believes to be the right thing, however, is precisely the wrong thing within a strict Christian code of conduct.

Aldeno: Bruckner, Hayez and Livia’s disavowal of the allegory of ‘violated Italy’

A pivotal moment anchors Bruckner’s Adagio as a political device in Senso, occurring during Livia’s secret encounter with Franz at the ancestral estate at Aldeno. Visconti emphasizes this eminently important narrative event by underscoring the sequence with the longest, uninterrupted musical cue in the film (at 1:02:03). The cue, which comprises the first full 61 bars of the Adagio, includes the two opening motifs and the idyllic, songlike theme of the B section. Franz’s nocturnal intrusion into Livia’s boudoir in his polished, snow-white uniform resembles a stock action from a run-of-the-mill Viennese operetta (at 1:01:29). The almost inaudible entrance of Bruckner’s Adagio signals that Livia continues to be driven by her inner compulsion.Footnote 77 In conflict with Bruckner’s Catholic message embedded in the Adagio, Visconti associates the beginning of this movement with Franz’s hedonistic world. Livia is torn between two forces: Franz wants to stay and continue the relationship, and Livia wants him to leave and end the affair.

In order to avoid the conventional, somewhat hackneyed shot–reverse shot technique, the mise-en-scène of this longer sequence replicates the manner as one perceives the action in an opera house. A panorama shot, for example, shows the whole room from a bird’s-eye view emulating the viewing experience from an opera box on to the stage. The setting resembles a quintessential stage design of a nineteenth-century Italian opera with Franz reclining on a chaise longue and Livia facing the other direction while sitting in front of a yellow dressing table. Visconti took the cue for selecting this gaudy colour directly from Boito’s novellaFootnote 78 and employed it to support the artificial, fictional world of opera he wished to create. Another opera-influenced shot depicts Livia sitting front-on to the camera, like a leading character on an opera stage. Her face is softly illuminated by an oil lamp, while Franz creepily approaches from behind and wins her over by caressing and cuddling her (bars 19–22 of the Adagio). Visconti marks Livia’s change of mind by precisely synchronizing the beginning of the ‘non confundar’ motif (at bar 23) with Livia’s capitulating to Franz’s artful seduction. Amplified by Bruckner, Livia submissively turns towards Franz and passionately embraces him. The seducing forces, which continue to possess the power to ‘hypnotise with music’Footnote 79 and successfully affect Livia’s mindset, have taken total control of her actions. For the first time in the whole sequence, she looks at Franz and imploringly invites him to stay. The ‘non confundar’ motif underlines her impulsive change of mind. Seemingly deceived in her judgement, she obeys the musical motto: ‘let me never be put to confusion’.

The musical Steigerung (augmentation towards a climax)Footnote 80 via sequences (from bar 23 onwards), which is visually mirrored by a camera pan from left to right, accentuates Franz and Livia approaching a closet in her boudoir in a close embrace. Analogous to the Steigerung and the camera pan, the music is swiftly faded up on the soundtrack to mark the onscreen action as particularly significant at this moment in the film. Precisely synchronized with the first climax of the movement (bars 27–9), Franz and Livia passionately kiss (Figure 1). This is an extraordinary moment for two reasons. Firstly, the ‘cluster sound’ marked fortissimo constitutes the subdominant with an added sixth (in relation to C♯ minor) that Bruckner has strategically spared after bar 9 until this moment in order to reach ‘the effect of harmonic completion’. Secondly, this ‘over-dimensioned cadence’Footnote 81 neatly coincides with a visual quotation: a tableau vivant of Francesco Hayez’s most celebrated painting, Il bacio (‘The Kiss’, 1859; Figure 2).Footnote 82 This carefully prepared narrative build-up towards the tableau vivant of Hayez’s painting, intensified by the Steigerung in Bruckner’s Adagio and the carefully executed camera pan, cannot be coincidental. Indeed, Visconti shapes this crucial moment in the plot development by recontextualizing Hayez’s painting through Bruckner’s music. The figure of Livia in this shot reminds Giovanna Faleschini Lerner of ‘the statue of Italia piangente with which Canova adorned the tomb of the patriot-writer Vittorio Alfieri’.Footnote 83 Antonio Canova’s allegory of Italy, which he created half a century before the beginning of the Risorgimento, however, suggests Italia turrita in mourning: a young woman with a crown embodying a stylized, ancient, towered city, which was an oft-used allegory for the Italian peninsula since late Roman antiquity, representing the proud national symbol of Italy. Hayez recoded Italia turrita for the years of the Risorgimento with the second version of his painting La meditazione (L’Italia nel 1848) (1851), in which the young woman with a dishevelled, forbidding facial expression and uncovered right breast holds a book in her hand entitled Storia d’Italia. She epitomizes the allegory of Italy as a betrayed, violated woman, an image strongly tinged by the Catholic doctrine of permitted female behaviour in nineteenth-century Italian society. Hayez’s young woman is no longer the immaculate counterpart of the holy Madonna; her virginity has been taken by the Austrian rulers in a heinous act classified in the ecclesiastic legal system as praesumitur seducta, a term which defines a woman’s destiny as ‘innocent victim of male lust’.Footnote 84 The cross in her left hand is thus simultaneously a sign of ‘religious penitence’ and of ‘contemporary martyrdom’.Footnote 85 In fact, this horrendous allegory reminds its onlookers of words expressed by the influential proponent of unification Giuseppe Mazzini: ‘Your homeland appeared to you one day in your dreams as a sister dishonoured by violence, as a mother who has lost her children, and weeps.’Footnote 86

Example 3 Bruckner: Symphony no. 7, Adagio, bars 177–80. Reproduced from: Symphonien von Anton Bruckner, Neue Ausgabe für Klavier zu vier Händen von Otto Singer, 3, p. 29.

Figure 1 Still from Luchino Visconti’s Senso (1954). Livia and Franz’s kiss at the Aldeno ancestral estate as tableau vivant of Francesco Hayez’s Il bacio (1859) (at 1:05:11).

Figure 2 Francesco Hayez, Il bacio (1859), oil on canvas, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan. Public domain.

Clearly influenced by Hayez’s La meditazione and more relevant to the present discussion is Andrea Appiani il Giovane’s Venezia che spera (‘Venice, which hopes’, 1861). The canvas shows a half disrobed, unkempt woman with a desperate look. Located on her right side is the Lion of St Mark and a cloak with an ermine collar and on her left is a crown which has fallen to the ground. The woman is, of course, an allegory of the betrayed and dishonoured Venice oppressed by foreign tyranny. The personality of Visconti’s Livia, however, could not be further from the allegorical woman seen in Venezia che spera. She resolves the depicted choice given to the young woman in Hayez’s Il bacio, ‘the conflict between civic duty and emotional attachments’,Footnote 87 in favour of dedicating her complete, emotional devotion to the inimical Franz. It is no surprise that Visconti chooses, in his pessimistic recounting of the last months of the Risorgimento, to turn Italy – as the ‘priestesses of the violated patria’, the ‘custodians of the heart and the honour of the “nation”’, suggesting the ‘classical notions of maternity and “national sacrality”’Footnote 88 – into an image of deceit, egotistical self-interest and betrayal. For him, such an image accentuates the notion of the Risorgimento as a failed revolution and ultimately as a movement aimed to preserve solely the concerns of the aristocratic class.Footnote 89

Visconti reinterprets Hayez’s painting with two narrative devices: the mise-en-scène and the music. He replaces the painting’s background of a stone wall in a large medieval hall with a common armoire. The open closet with Livia’s wardrobe visible, which is within a nineteenth-century context a quite intimate display, alters Hayez’s message. The painter’s intention of showing a parting couple set in noble, medieval surroundings, the man about to execute an important mission with his dagger while his woman patiently awaits him at home, is transformed by Visconti, who presents a lewd upper-class boudoir. Visconti confirms his reinterpretation with his next shot. Marking an ellipsis, it displays the surface of Livia’s dressing table with beauty potions, implying that the love has been consummated. The reframing of Hayez’s painting discloses that Livia has advanced from an aristocratic, respected woman to a willing courtesan, just as the Italian people would do more than 60 years later – in Visconti’s opinion – by prostituting themselves to Fascism.

Bruckner’s Adagio – as a means of effacing the political message of Il bacio, which signals optimistic confidence for a liberated Italy – supports the reinterpreted painting. If Visconti had inserted Verdi’s ‘All’armi, all’armi …’ at this climactic moment as an ‘ideological call to arms’,Footnote 90 in Anna Villani’s words, the message would have been very different. Verdi would have lent support to the highly political, revolutionary call of Hayez’s Il bacio; instead, Bruckner affirms that Livia deliberately chooses to betray the cause of unification and to accept Austrian ruling over Venetia. Visconti undoubtedly highlights this impulsive decision by synchronizing the first climax of the Adagio movement with the tableau vivant. With Bruckner going against Hayez, Visconti reveals that Livia does not represent the violated allegory of Venice but a willing subject effortlessly submitting herself to the deceptive allure of the occupier. She does not passively endure her destiny as the young women do in Il bacio, La meditazione and Venezia che spera, but instead she actively (re)acts to the events affecting her; she is thus responsible for her own actions. Livia has a moral choice as an aristocratic Venetian woman either to support the cause of Italian unification or to surrender her heart to an Austrian officer. She chooses the latter.

The film thus invites the audio-viewer to interpret this kiss as a political statement which is emphasized by the enticing power of Bruckner’s ‘non confundar’ motif,Footnote 91 leading Livia to surrender to Franz’s seduction. Bruckner redoubles Visconti’s intention of depicting the Austrian superpower as Eros beguiling the compromised, non-unified, corrupt and conquerable Venetian aristocracy in order to dominate it. As a pars pro toto, Livia embodies the Venetian aristocracy which seems to prefer to live under Austrian rule instead of becoming part of the new Italy. In this sequence, Visconti lays bare, as a metaphor and with the support of Bruckner and Hayez, the mechanisms of such a deliberate desire for Austrian submission, for tolerating the ruler one knows.

Aldeno: The ‘non confundar’ motif and betrayal of the revolution for blind love

A crucial turning point, which still takes place at Aldeno, occurs shortly after the kiss. In this sequence, Bruckner’s Adagio continues to control Livia’s capability to make presumably the ‘right’ decision. Hidden in the estate’s granary, Franz suggests to Livia the possibility of obtaining a medical dispensation.Footnote 92 His strategy to make her an accomplice in his risky undertaking bears fruit in one of the following sequences (at 1:18:32), when she revisits the possibility of Franz receiving a medical exemption from his military service to avoid his separation from her and dodge combat, and possible death. During the transitional section of the Adagio’s ‘development’ (bars 111–14), Franz feigns surprise by turning the tables and pretending that she proposes he do such a contemptible act. He manipulates her willingness to go along with his devious scheme by first doubting the feasibility of the plan and then coming round to it by naming a sum needed to bribe an army doctor. The music is complicit with Franz and supports his insincere behaviour with a sequenced, densely contrapuntal, forward-pushing transitional passage. While he tells her that it is a question of the price, the second, ascending motif of the A section begins. The final words of the Te Deum ‘non confundar in aeternum’ motivate Livia’s actions. The ‘non confundar’ motif implies her eagerness to go through with his plan. With the unaccompanied, ‘released’ first violin motif (bars 116–17), which Kurth described as ‘resounding out into the void’,Footnote 93 Livia asks how much money is needed. At this crucial moment, the seductive power of the music, generated by Bruckner’s Adagio, completely controls her ability to make a presumably ‘non-confounded’ decision. Livia’s impulsive resolution, which contradicts the message of the music, pulls the two lovers down into a dark abyss.

The harmful consequences of her imprudent judgement immediately take shape. Prompted by Livia’s unexpected but decisive gaze almost directly into the camera, the ‘non confundar’ motif in its famous cadential appearance, marking the movement’s climax, accompanies her action of misusing the funds entrusted to her by her cousin Ussoni and handing them over to Franz in order for him to bribe an army doctor (bar 177; see Example 3). The cadential figure of the ‘non confundar’ motif, which until now has appeared only in the much less bombastic orchestration discussed above (when Livia takes the lead from Franz and reiterates to him the idea of his plan), now thunders on the soundtrack in its hyperdramatic variation strategically placed towards the end of the Adagio. The triple-forte outbreak of the whole orchestra, supported by timpani, triangle and cymbal crash,Footnote 94 takes complete charge of Livia’s feelings and controls and enables her decisive stride through several rooms away from her lover and the camera towards the strongbox containing the money.

In a stunning marriage of music and image, the powerful cadential tutti, led by the Wagner tubas and other brass instruments, reinforces the striking image of the hurrying Livia, as she opens two sets of double doors to reveal three large rooms of the villa (see Figure 3).Footnote 95 At this point, music and image engage in an audio-visual alliance, which Michel Chion calls ‘synchresis’. He describes this phenomenon as the ‘forging of an immediate and necessary relationship between something one sees and something one hears at the same time’.Footnote 96 This moment in the film represents a perfect example of ‘synchresis’ because of the ‘spontaneous and irresistible weld produced between’ the mise-en-scène, the cinematography, the acting style and, of course, the music, which are all engaging to form a perfect union of ‘mutual reinforcement’.Footnote 97 In this sense, the release of the music as a moment of ‘disappearance of the thematic material within the general orchestral sound’Footnote 98 is visually mirrored by expanding the confined space into a large, open one as a metaphor for having found a solution to prolong the clandestine and adulterous love affair. This is a literal moment of ‘opening doors’, of keeping the illicit affair alive, once more, for Livia’s own pleasure, and at the expense of the more noble cause of the unification.

Figure 3 Still from Luchino Visconti’s Senso (1954). At Aldeno, Livia fetches the strongbox containing the funds designated for the volunteer soldiers for the imminent Battle of Custoza (at 1:21:28).

This culminating plot moment, delineated by the cadential characteristics of this climactic passage of the Adagio, represents not only a dramaturgical exclamation mark but also recalls a Verdian operatic momentFootnote 99 – but with Wagnerian-inspired music instead. In combination with a striking mise-en-scène featuring borrowed elements from the world of opera staging, Visconti consciously places the ‘non confundar’ motif at this moment in the film to accentuate the turning point in the narrative. Livia betrays the cause of the Risorgimento by deciding to squander the money reserved for paying the Venetian soldiers of La Marmora’s Italian army; it is in fact a double betrayal, for she uses the money to bail an Austrian officer, Franz, out of his patriotic duty to fight for his country. However, contrary to the idealism and anticlericalism of the Risorgimento movement, Bruckner’s – in this case – reactionary ‘non confundar’ motif continues to depict the present in a decisively Catholic manner as a ‘never fulfilled past-cum-future’ until the arrival of the Resurrection and the Second Coming of Christ.Footnote 100 Against the deeply symbolic meaning of the music and the idealized political cause, the ‘non confundar’ motif, linked with the Te Deum, which lingers in the film as a vestige of Bruckner’s devout Catholic faith, can be interpreted here as a sign of hypocrisy. Franz and Livia are most likely both Catholics; their moral compass as members of the Austrian and Venetian ruling class ought to have guided them according to the Catholic doctrine of sexual behaviour, which was more or less directly derived from St Augustine’s writings. This century-old structure of defining gender in society is knowingly based on a hypocritical, patriarchal system of double standards for women and men. Acts of adultery committed by men – in particular, by members of the aristocracy – were tolerated in society and could be conveniently undone through confession, penance and absolution administered by the Church. Women, on the other hand, were constrained to protect their virginity through strict chastity before marriage, following the example of the Virgin Mary. Once women were wedded, the Catholic church only allowed them sexual activities with their husbands for the sake of procreation, and by no means for pleasure and desire.Footnote 101 Women’s extramarital amorous activities were criminally prosecuted and societally condemned as an act of harlotry. The only individual with the legal right to file a civil and/or criminal prosecution against an unfaithful woman was the respective husband.Footnote 102

Livia, however, knows that her much older husband would refrain from initiating a trial against her owing to her elevated social status and his own impeccable reputation in Venetian society. For this reason, she has the luxury of temporarily rejecting her Catholic upbringing; she instead behaves like a hedonistic narcissist driven by her own selfish interest and sexual desire. The double betrayal of her faith and patriotism is subtly alluded to by Bruckner’s music, the deceptive meaning of which at this climactic moment is already present in its musical structure. The ‘pure sound’ that ‘comes to seem more and more of the essence’Footnote 103 is not a C major chord in root position but the chord in second inversion. This unstable harmonic structure matches Kurth’s assessment that the chord ‘staggers’ owing to ‘its own abundance of weight’. According to Kurth, the chord carries its own ‘downfall in itself’.Footnote 104 This gigantic moment in the Adagio is, therefore, built on an unstable foundation; the structural fragility in the music announces that things are not as they seem. On a microlevel, Livia is completely convinced that she has reached a point of ‘non-confoundment’, and that things with her and Franz will turn into a blissful union after his discharge from the army. In the film’s finale in Verona, which takes place after the Battle of Custoza, Livia’s hopeful certainty of a successful outcome of her new relationship will, however, be bitterly disappointed owing to the system of aristocratic social mores still dominated by Catholic reasoning. On a macrolevel, the unstable C major chord thus juxtaposes the tension between the ecclesiastical system and the anticlerical aspirations of the Risorgimento. The striving for an antireligious liberation advocated by the engineers of the unification movement and later by the Marxists remained in the post-Risorgimento era as much an illusion as it would in the immediate post-Second World War period, after the occurrence of a series of ‘successive failures to secure the progressive rationalism’ proposed by the secular forces in the country.Footnote 105

Verona: Livia’s denunciation and Franz’s execution

The ‘non confundar’ motif continues to dominate the final moments in Verona: Livia’s visit to her lover’s flat, her denunciation and Franz’s execution. At this point, the seductive forces have transformed the dynamics from a benevolent power of passionate love into an unmitigated release of full destruction. First, the ‘non confundar’ motif seals Livia’s ‘non-confounded’ decision to visit Franz at his flat in Verona, despite Franz’s letter warning her that a journey to Verona might be too dangerous. Livia arrives at Franz’s flat, expecting to see him alone, but instead meets him drunk with a prostitute. Visconti stages this sequence as a disastrous encounter between Livia, the prostitute in her undergarments, and Franz, unshaven and carelessly dressed in a robe sitting ruffled in an untidy, crammed and tastelessly furnished sitting room. Bruckner’s colossal Adagio clashes with this petty bourgeois setting. Accompanied by the first motif of the A section (Wagner’s Trauermusik), the prostitute, Clara, offers Livia a glass of wine. This simple gesture represents a jarring contrast to the sweeping, noble threnody dedicated to Wagner. Having bailed out Franz with the money reserved to finance the participation of the Italian battalions at the Battle of Custoza, Livia now realizes that while this very battle was fought he spent the time with a prostitute. Distraught at the thought of this, his miserable state and his rejection of her, Livia suffers a complete breakdown. The four Wagner tubas of the threnody motif tellingly announce Livia’s decision, which she makes at this moment of greatest delusion, to denounce Franz and to take his final destiny into her own hands. Wagner’s threnody thus mutates into the one of Franz.

After the sequence of Livia’s denunciation of Franz to the Austrian General Hauptmann in Verona, Livia, bewildered, aimlessly strolls through the nocturnal streets of Verona, madly shouting for Franz.Footnote 106 She is harassed by drunken Austrian soldiers emboldened after having won the Battle of Custoza. Indeed, it was virtually impossible for an upper-class woman in Venetia in the middle of the nineteenth century to promenade the public streets alone,Footnote 107 and Visconti was well aware of this societal taboo. With his shot of Livia leaving the garrison alone and being molested by Austrian soldiers, he implied that she was no longer a respected, aristocratic woman of the Venetian ruling class and an ardent supporter of the unification movement, but had instead become a traitor to the national cause and a common courtesan betraying her husband’s and cousin’s trust. On the soundtrack, we do not hear an Austrian song of victory, as originally planned, but the ascending, sequenced ‘non confundar’ motif, the Steigerung to the first climax of the movement (bars 19–29), which Visconti used earlier to highlight the tableau vivant of Hayez’s Il bacio. Here, this identical passage assumes a very different significance and acts in a Verdian manner as a reminiscence motif. It highlights the trajectory from embrace and kiss in Aldeno to denunciation, despair and madness in Verona. Dalle Vacche observes the significance that ‘Livia acquires a pathological identity as soon as she cannot be the female alter ego of any male character’. After the disastrous outcome for the army of the Kingdom of Italy at the Battle of Custoza, she is completely ‘outside history’ and is instead ‘engulfed in a melodrama so personal that it degenerates into madness’.Footnote 108

The sequence, with Livia’s feelings alternating between self-pity, bitter anger and erotic longing for the denounced lover, is a prototypical operatic trope. Susan McClary has demonstrated that the ‘dramatic subject of madwomen’ can be encountered in female protagonists from Monteverdi’s Lamento della ninfa and Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor to Strauss’s Salome and Schoenberg’s Erwartung. Footnote 109 McClary argues that while madwomen in literature are usually silent, the addition ‘of dramatic music has offered the extraordinary illusion of knowledge beyond the lyrics, beyond social convention’. Bruckner’s Adagio accordingly provides the audio-viewer in Senso ‘license to eavesdrop upon [Livia]’s interiority’. In a quintessentially operatic theatricality, the Adagio conveys that the ‘spectacle of madness’Footnote 110 originated with the kiss at Aldeno – as a manifestation of overt eroticism – and ends in the streets of Verona in complete madness as an excess of female sexuality. Elaine Showalter attributes such an excess to the central nineteenth-century medical concern of insanity as the quintessential female malady.Footnote 111 The image of Livia looking as dishevelled as the woman who represents as an allegory battered and subjugated city of Venice in Appiani il Giovane’s patriotic painting Venezia che spera, rubs uncomfortably against the soundtrack which features the highly heroically charged passage of Bruckner’s Adagio with the sequenced, short ‘non confundar’ motif building towards the first climax of the movement. Within the context of Livia’s depiction as the quintessential nineteenth-century operatic madwoman, the motif has lost its positive, uplifting connotation; instead, it falsely signals to Livia that she has done the ‘right thing’, as in the sequence with Franz in Aldeno. For the audience, however, it implies here a tragic swansong, stressing Livia’s mental state as being governed by complete desperation, madness and absolute contempt for her former lover. Her actions have been everything but patriotic, and her psychological condition is everything except ‘non-confounded’. This concluding passage of the Adagio’s first theme has turned cynical since its appearance during the kiss at Aldeno, highlighting that Livia’s ‘non-confounded’ determination has given way to complete and utter confusion.

Franz’s nocturnal execution is sombrely accompanied by occasional snare drum calls and a refrain that during the First World War was frequently added by German soldiers and amateur choirs to the well-known soldiers’ song Der gute Kamerad (‘In Battle He Was my Comrade’, 1809), after each of the three stanzas.Footnote 112 The original meaning of Ludwig Uhland’s poem emphasizes a soldier’s sense of duty and his military obedience to his superiors and peers. At the beginning of the First World War, the added refrain refers to the soldiers’ merry reunion back home, a hopeful wish which was reinterpreted after the defeat in the Great War as a more sombre reunion in the hereafter.Footnote 113 At least since the First World War, Der gute Kamerad has further attained a symbolic meaning honouring the heroism of fallen soldiers. In the context of Franz’s execution, all these praiseworthy values are absent. Franz was neither obedient nor dutiful, having instead become a coward deserter. Recalling the song’s meaning, his peers may thus feel no need to mourn his less-than-heroic death. None of the present soldiers would likely wish to reunite with him in the hereafter.

After Franz’s execution, the singing soldiers are abruptly cut off by the Adagio’s apex, which resolutely concludes the film. The reprise of the ‘non confundar’ motif in its cadential appearance sanctions his death as the final consequence of Livia’s action, which she initiated at Aldeno in her seemingly ‘non-confounded’ state enticed by the triple-forte climax of the Adagio (bar 177).Footnote 114 Kurth interprets the movement’s pinnacle as a point of release (Erlösung) after the long build-up to this culminating moment. Parkany specifies that Kurth understands redemption ‘not merely in the sense of “release”’ but in the sense of Christian ‘redemption’.Footnote 115 Such a notion of redemption is, however, entirely absent at the end of Senso. The film cynically concludes in total disaster, far removed from the concept of redemption. The complete disorder is indicated by the C major chord in its second inversion which does not signal a stable finale but instead a deceiving one built on shaky grounds. This unstable chord implies that redemption is a Christian thought unknown to the world of Senso. In a somewhat over-articulated, moralizing fashion, the climax of Bruckner’s Adagio and the dark images shot at night with the barely visible Austrian soldiers carrying away Franz’s body underline at the film’s end that Livia’s and Franz’s behaviours are regulated by an indoctrinated Catholic interpretation of gender relationships and motivated by entitled and egotistical aristocratic privileges, which are fundamentally opposed to the anticlerical, progressive programme of the Risorgimento. Visconti’s pessimistic message with Bruckner’s ‘non confundar’ motif and the volatile final chord deceivingly signalling closure affirms that Livia’s class will prevail. Despite the desperate uprising of the bourgeois class, the members of the aristocracy will continue to conduct themselves under the new government of the Kingdom of Italy as they did under the Habsburgs, who have been their political rulers yet simultaneously their socially equal allies for almost 60 years.

Conclusion

The film’s opening sequence at the Teatro La Fenice brings together Venetian aristocracy, officers of the Austrian occupiers and ordinary people of the Italian middle class under the gods. The fragmented performance of Verdi’s Il trovatore, as a mini-opera, and the organized response to the music by the Italian middle-class spectators convey an idealism that is sincere, straightforward, stoic and brave but which is ultimately deemed a failure. The pro-unification theatre-goers politicize Verdi’s music as a spiritual weapon to announce to the Austrian members of the audience the inevitable liberation of the city from its oppressors. Their idealism is, however, swiftly stifled. After all, for Visconti, the Risorgimento was a failed revolution resulting in the fact that the Italian aristocracy continued to be as much in power as it was before the unification.