Introduction

The Nazis constructed a network of over 44 000 concentration, extermination, labour, prisoner-of-war (POW) and transit camps across Europe, imprisoning and murdering individuals opposed to Nazi ideologies and those considered racially inferior (Megargee & White Reference Megargee and White2018). Information about these sites varies due, in part, to Nazi endeavours to destroy the evidence of their crimes (Arad Reference Arad1987: 26; Gilead et al. Reference Gilead, Haimi and Mazurek2010: 14; Sturdy Colls Reference Sturdy Colls2015: 3). Public knowledge regarding camps that were built on British soil in the Channel Islands is particularly sparse, not least because they were partially demolished and remain “taboo” (Carr & Sturdy Colls Reference Carr and Colls2016: 702). Sylt was one of several camps built on the island of Alderney (Figures 1–2), and first operated as a labour camp (to exploit prisoner labour), before becoming a Schutzstaffel (SS) concentration camp (intended to imprison political enemies and opponents to the regime) in March 1943.

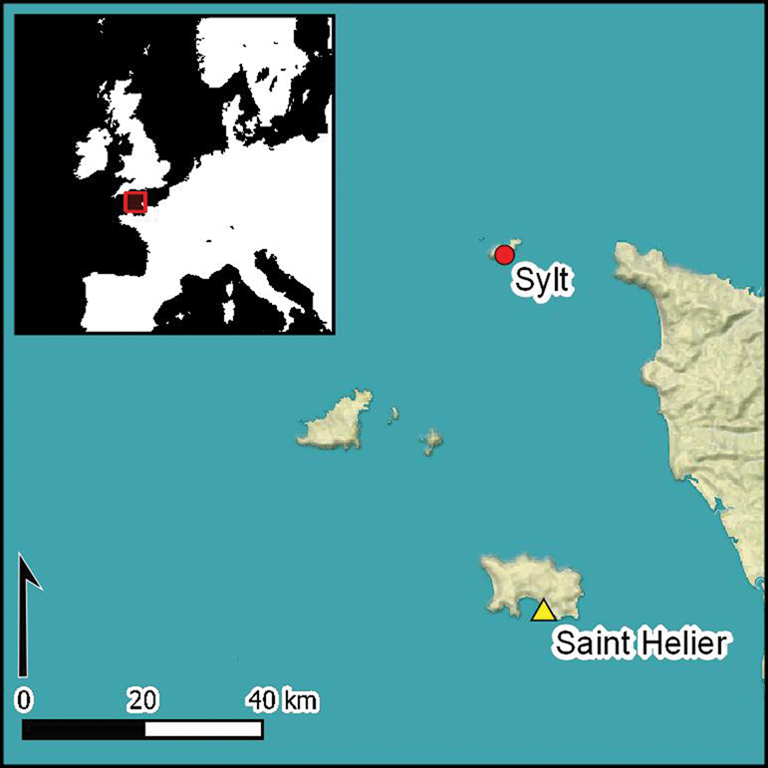

Figure 1. Maps of the Channel Islands, showing Alderney's position approximately 15–20km off the northern coast of France (images: Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University).

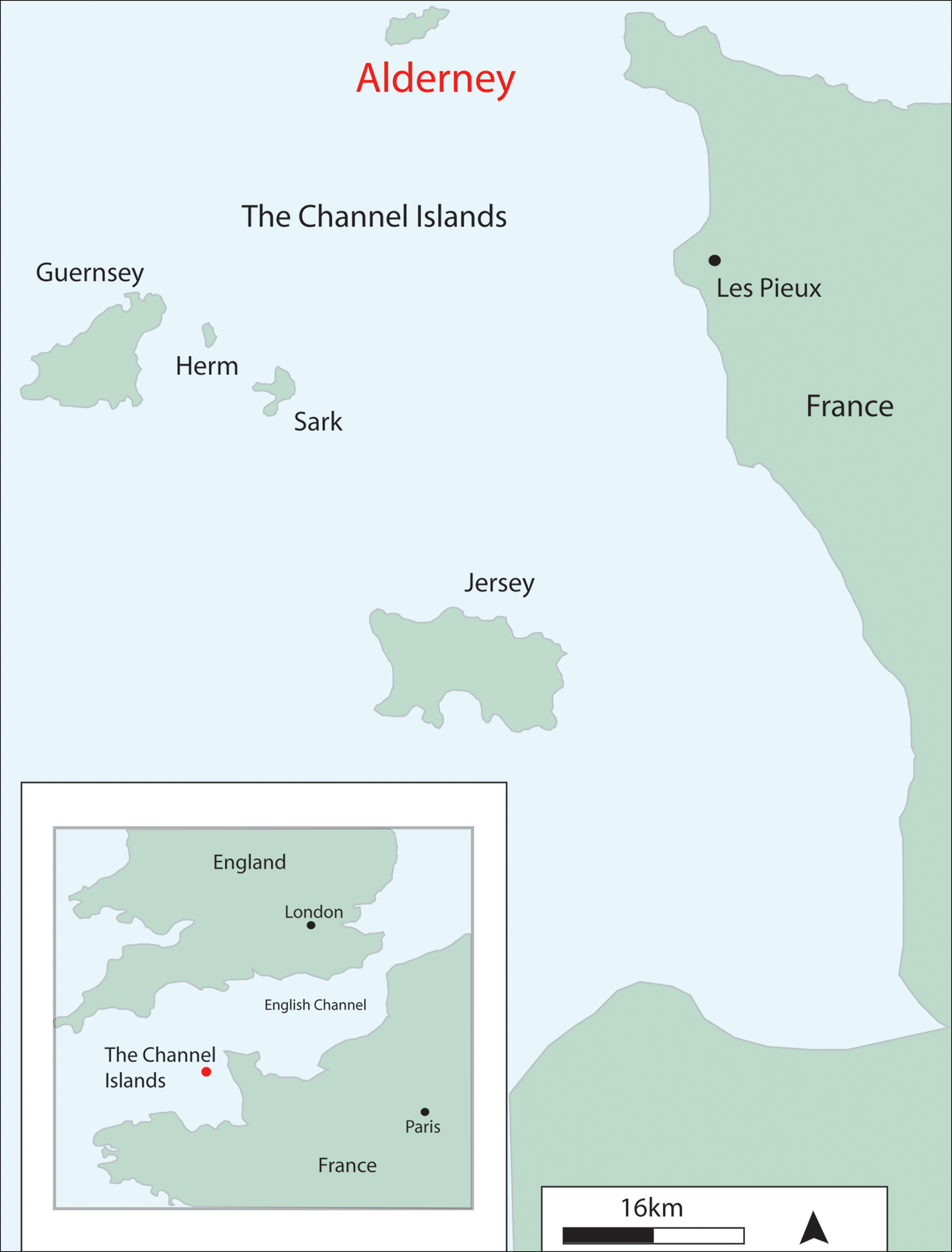

Figure 2. The island of Alderney and the location of Helgoland, Norderney, Borkum and Sylt camps (images: Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University).

The literature describing Sylt often claims that the camp was “destroyed”, “dismantled” or “burnt”, leaving only gateposts, a few bunkers and an underground tunnel (Packe & Dreyfus Reference Packe and Dreyfus1971: 59; Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 36; Steckoll Reference Steckoll1982: 182; Bonnard Reference Bonnard1993: 72; Sanders Reference Sanders2005: 205) (Figure 3). Aside from the few visible traces, the only other marker in the landscape acknowledging the site's former function is a memorial plaque erected in 2008 at the request of former prisoners (Carr Reference Carr2012: 102; Figure 3A). Today, the site hosts a disused building constructed in the 1960s to house airport direction-finding equipment, and is covered with dense vegetation (Pinnegar Reference Pinnegar2010: 3). The former camp area is privately owned by several landowners, some wishing to protect it, others not sharing this enthusiasm for its wartime history. Although the site was designated a conservation area in late 2017, its physical condition remains unchanged in 2019 (The States of Alderney 2017).

Figure 3. UAV photogrammetry of the site of the former labour and concentration camp of Sylt in 2017, and the memorial plaque installed in 2008 by a survivor on the camp gateposts (marked A) (images: Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University).

Between 2010 and 2017, the Centre of Archaeology at Staffordshire University undertook historical and archaeological investigations at the Sylt labour and concentration camp as part of the ‘Alderney Archaeology and Heritage Project’ (Centre of Archaeology 2018). Through comprehensive historical research and the development and application of non-invasive archaeological methodologies, our aim was to map and characterise the extent and nature of Sylt in order to:

1) Document the site accurately (preservation by record).

2) Determine what physical traces of the camp survive today.

3) Provide new insights into the relationships between architecture and the experiences of those housed there.

Research questions include: how did the camp evolve over time and how did this affect the inmates' experiences? How did the architecture of the camp allow the SS to maintain control over the inmates? To what extent has the camp been destroyed (intentionally or by later decay or damage), and how might this influence future protection measures? Given the current condition of the site and attitudes towards it, how might archaeological investigations contribute to heritage management and education? This article addresses these questions and seeks to demonstrate the valuable contribution that an interdisciplinary approach can make when researching sites of past atrocities.

Historical background

Alderney (4.8 × 2.4km in extent) is the most northerly of the Channel Islands, an archipelago of five islands between England and France (Clarke Reference Clarke2008: 19; Figure 1). Following the ‘Battle of France’ in early summer 1940, the British Government decided that the Channel Islands were too difficult to defend against Nazi invasion and evacuated 1432 islanders from Alderney on 23 June 1940 (Archive 1 1940; Bonnard Reference Bonnard1993: 5). On 2 July 1940, the Luftwaffe landed on Alderney, encountering no resistance. Thus, the island's ‘occupation’ was a propaganda coup of tactical value to the Nazis: Alderney was supposedly the “last stepping stone before the conquest of mainland Britain” (Bonnard Reference Bonnard1991: 21). As part of Hitler's ‘Directive on the fortification and defence of the Channel Islands’ (1941; Stephenson Reference Stephenson2013: 57), Alderney became one of the most heavily fortified landscapes in Western Europe, and was incorporated into the Atlantic Wall, the system of coastal defence along its western coast (Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 3).

By 1942, Alderney's population comprised mostly paid and unpaid foreign workers under the governance of the Organisation Todt (OT), a civil and military engineering group responsible for supplying labour to the Third Reich. While these workers came from more than 30 countries, most were Eastern Europeans—described as ‘Russians’ in Nazi documents, but coming from Ukraine, Poland, Russia and other Soviet territories (Sturdy Colls & Colls Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsin press). Most were forced or slave labourers, or they had ‘volunteered’ under duress. Many were considered political enemies of the Third Reich, although there was also a large contingent of French Jews (Luc Reference Luc2010). The OT housed the workers in the Helgoland, Norderney, Borkum, Sylt and Citadella camps constructed around the island (Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 6), alongside several smaller, unnamed camps (Sturdy Colls & Colls Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsin press) (Figure 2). Helgoland housed around 1500 forced Eastern European labourers; Norderney around 1500 Eastern European, French (mostly Jewish), Czech, Dutch and Spanish forced workers, alongside German volunteers; and Borkum housed between 500 and 1000 mostly German volunteers (Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 6).

Sylt forced labour and concentration camp: an overview

Located to the south of Alderney's airfield, adjacent to a cliff road, Sylt was constructed to house 100–200 Eastern European political prisoners, who arrived in August 1942 (Archive 2 1947). Under the command of the OT, these prisoners were responsible for fortifying Alderney's defences and, ultimately, the Atlantic Wall (Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 31; Bonnard Reference Bonnard1991: 63).

The limited testimonies that describe life in Sylt labour camp highlight the severity of the atrocities committed, even in this early period. Former Helgoland camp prisoner Georgi Kondikov, for example, described Sylt as “the most terrible camp [which] everybody was afraid of” (Bonnard Reference Bonnard1991: 50). This reputation was attributed to the camp's architecture—barracks exposed to the windy weather—and the treatment of prisoners by OT staff. Former Sylt prisoner Cyprian Lipinski explained how, during forced labour duties, “we were beaten with everything they could lay their hands on […] most of these beaten people died of wounds they had received” (Archive 3 1945–1948). Each prisoner was assigned to a labour company and forced to undertake heavy construction work for 12 hours per day. They were inadequately dressed and undernourished. Daily rations consisted of black coffee for breakfast; a thin soup and a loaf of bread between five prisoners for lunch; and a relatively thicker soup with butter for dinner (Archive 3 1945–1948). The OT did not administer medical treatment at Sylt: sick prisoners who were able to walk were sometimes permitted to visit the hospital at Norderney (Archive 4 1945–1948). One-fifth of the camp's inmates reportedly died between August 1942 and January 1943 (Sanders Reference Sanders2005: 200; Sturdy Colls & Colls Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsin press).

In March 1943, Sylt was transformed from a labour to a concentration camp through an exchange in command between the OT and the SS Totenkopfverband (Death's Head Unit). The latter was a Nazi paramilitary organisation in charge of concentration-camp operations, specialising in acts of dominance and brutality (Sanders Reference Sanders2005: 197). The OT prisoners in Sylt were transferred to the Helgoland and Norderney camps to make space for incoming prisoners of the SS (Archive 4 1945–1948).

In September 1942, the SS formed a series of Baubrigaden (building brigades) in Germany and, in March 1943, SS Baubrigade I was transported to Alderney (Archive 5 1942). Just over 1000 prisoners arrived via the German concentration camps of Sachsenhausen and Neuengamme. Sylt was designated a sub-camp of the latter (Megargee Reference Megargee2009: 1361). Treated as slave labourers, the prisoners comprised approximately 500 Russians and Ukrainians, 180 Germans, 130 Polish, 60 Dutch, 20–30 Czech and 20 French nationals, most of whom were classed as political prisoners (Archive 4 1945–1948). As Fings (Reference Fings2009: 135) states, “the SS-Baubrigaden consisted, as a rule, of male non-Jewish prisoners”, although some sources suggest that a small number of Jews were present in the camp (Sturdy Colls & Colls Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsin press). Later, Sylt also received approximately 135 OT prisoners who had committed perceived crimes (Archive 2 1947). SS prisoners were distinguishable from other labourers because they wore distinctive SS concentration camp blue-and-white-striped pyjama uniforms (Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 32; Freeman-Keel Reference Freeman-Keel1995: 62). Prisoners were identified by a number and coloured triangular symbols worn on their uniforms to show their offence/group (Archive 2 1947). They were subjected to hard labour, poor rations and harsh punishments from their overseers. If a prisoner died, the SS issued the Sylt doctor with a pre-printed death certificate, which often labelled the cause of death as ‘faulty circulation’ or ‘heart failure’ (Archive 4 1945–1948). Island doctors were frequently not permitted to view dead bodies, but were instructed by the SS to sign the death certificates (Archive 4 1945–1948). According to the death register at Neuengamme concentration camp, the official number of deceased SS inmates at Sylt was 103 individuals (KZ-Gedenkstätte Neuengamme 1943–1944). This, however, represents a minimum number, especially as several alleged shootings do not appear in this register (Sturdy Colls & Colls Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsin press).

Between 70 and 80 SS guards ultimately oversaw Sylt, resulting in tight control and harsh conditions for the prisoners (Fings Reference Fings2009). SS-Untersturmführer Maximillian List, the first Camp Commandant and head of the Baubrigade, was succeeded by SS-Obersturmführer Georg Braun in March 1944. Both men were long-serving members of the Nazi party; List “ordered the security to treat the prisoners harshly” and Braun was “brutal to excess” (Archive 6 2007; Archive 7 undated). Certain prisoners were assigned the role of ‘kapo’ by the SS, which required the supervision of, and disciplinary action against, other inmates (Archive 4 1945–1948; Bonnard Reference Bonnard1991: 33). The kapos ensured that work was conducted to standard and, if considered unsatisfactory, they would inflict punishment. This approach created hierarchies and mistrust within the camp.

Previous investigations at Sylt

Declassified intelligence documentation concerning Sylt shows that multiple investigations took place in 1945, following the British liberation of Alderney. The first two-day investigation by Brigadier Snow, Major Haddock and Major Cotton revealed that Sylt was initially constructed to house Eastern European prisoners, and in 1943 was “controlled by the S.S. for political, homosexual, conscientious objectors etc., prisoners of all nationalities” (Archive 2 1947). Eyewitness testimonies detail the atrocities at Sylt, specifically beatings, dog attacks and shootings (Archive 8 1945–1948). The investigation also discovered a false-bottom coffin at the site of the OT and SS worker cemetery on Longy Common, and documented rumours of mass graves (Archive 3 1945–1948; Sturdy Colls & Colls Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsin press). The dismantlement of Sylt by the Germans was also described, including how materials were re-used by them for “defence works” (Archive 9 1945).

In June 1945, at the request of the British War Office, Major Pantcheff assumed control of the investigations. Alderney was also visited by a Russian investigative team led by a Major Gruzdev. These various investigations culminated in approximately 3000 interviews with survivors, witnesses and members of the German forces. Pantcheff's investigation also documented brutality and murder, terrible working conditions, details concerning the SS staff, the operational deployment and departure of Baubrigade I, illnesses, medical treatment and the deceased (Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 29). Pantcheff, however, also stated that “German records in Alderney were so confusing, that one cannot but doubt whether those traditionally so renowned for meticulous and efficient administration were in this instance really aiming for clarity” (Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 70). The only known plan of Sylt was produced in 1945 and verified by members of the German forces on Alderney, and photographs were taken of the camp (Figure 4). By focusing investigations primarily on the SS operations rather than the OT, however, significant information was missed regarding activities at Sylt prior to 1943.

Figure 4. Photograph of the Sylt concentration camp taken in 1945 (© Trustees of the Royal Air Force Museum).

After the Second World War, the existence of Sylt became public knowledge through media reports, resulting in rumours about a death camp on Alderney (Megargee & White Reference Megargee and White2018: 1362). To quash these claims, the findings from Pantcheff's 1945 investigation were published in 1981, but presented a less atrocious version of events compared to the original investigation. Although the 1945 investigations highlighted the extent of atrocities at Sylt and identified those responsible, no prosecutions took place. Prisoner nationalities were simplified (reducing most victims to ‘Russian’) and, eventually, claims regarding the brutality were watered down (see Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981 compared to Archive 6 2007). This was partly guided by the British Government's desire to hand over the investigations to the Russian government in 1945, and to forget about the crimes perpetrated on the island, a view shared by many in the local government and population of Alderney (Sturdy Colls Reference Sturdy Colls2012; Sturdy Colls & Colls Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsin press).

Methodology

Historical research and archaeological fieldwork were undertaken at Sylt between 2010 and 2017 to establish the condition of the site and to elucidate disparities between the source materials. This study examined material from numerous archives around the world to document the history of the site, to identify fieldwork survey areas and to interpret the resulting data. Although historical sources provide a valuable resource, Nazi documentation can be misleading due to deceit, biased writing or missing documents (Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 70; Myers Reference Myers2008: 234). Archaeological investigations are therefore crucial, as they can complement and supplement historical records through the identification of surviving physical evidence.

Non-invasive methods were employed during the archaeological fieldwork, including systematic fieldwalking, remote sensing, geophysical survey and vegetation clearance, which confirmed areas of significance, revealing archaeological features, surface topography and surface finds (for example, through vegetation indicators). These discoveries confirmed the need to record surviving features threatened by erosion. A combination of differential kinematic global positioning systems, total station recording, ground-penetrating radar, resistance survey, photogrammetry and light detection and ranging (lidar) were used to record the position of vegetation indicators, depressions and structural remnants accurately. These non-invasive methods permitted the scanning and visualisation of extensive areas, even through high-density foliage (Sturdy Colls Reference Sturdy Colls2015: 172; Abate & Sturdy Colls Reference Abate and Colls2018: 130). Diverse datasets resulting from desk-based assessments and fieldwork have allowed the development of 3D models that demonstrate Sylt's evolution between 1942 and 1945, and provide a useful resource for heritage management.

Mapping the evolution of Sylt's architecture

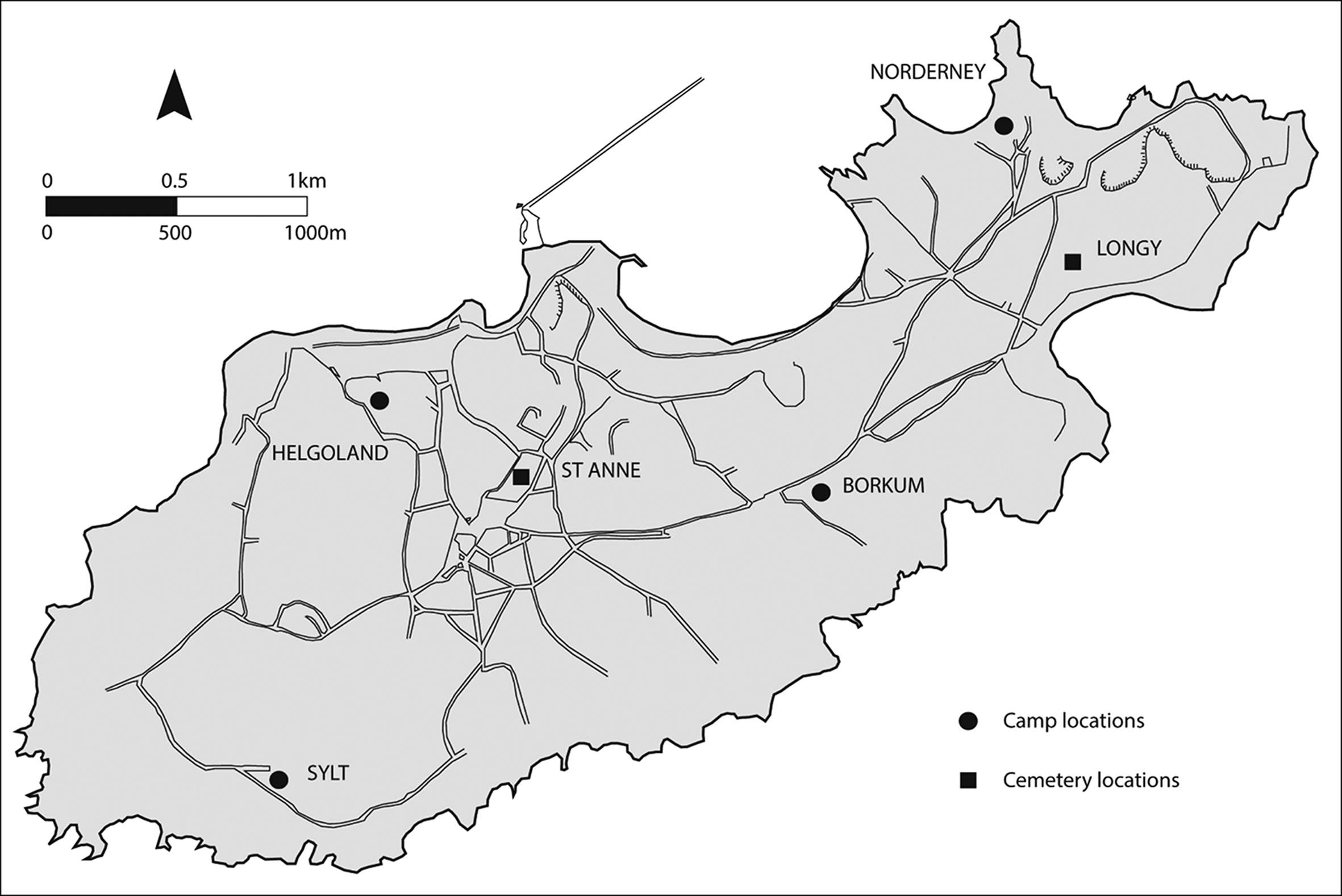

Sylt's gradual development can be reconstructed from documentation held in archives, aerial reconnaissance, maps and plans (Figures 5–6; National Collection of Aerial Photography Archive 1 1942; National Collection of Aerial Photography Archive 2 1943; National Collection of Aerial Photography Archive 3 1944). By August 1942, Sylt comprised five barracks that were reportedly constructed by political prisoners and French ‘volunteer’ labourers, under the supervision of the OT. The camp security consisted of guarded gateposts and “its perimeter [was] surrounded by coiled concertina barbed wire” (National Collection of Aerial Photography Archive 1 1942; Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 6) (Figure 6A). Aerial photographs show that by January 1943, the camp had tripled in size ahead of the arrival of the SS (National Collection of Aerial Photography Archive 2 1943) (Figure 6B). In March 1943, however, when the Baubrigade I prisoners arrived, they described the camp as unfinished, reporting that only four barracks were usable, even though aerial images show that many more buildings were present (Kukuła Reference Kukuła2003: 11; Archive 10 1945). Some prisoners had to sleep outside for two months while construction continued (Bonnard Reference Bonnard1993: 175).

Figure 5. 3D reconstructions of Sylt for: A) 1942; B) 1943; C) 1944; D) 2017 (images: J. Kerti).

Figure 6. 2D plans showing the development of Sylt for: A) 1942; B) 1943; and C) 1944, based on aerial photographs (images: Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University).

By August 1943, the camp had been extended to 25 structures, which included SS buildings and the Commandant's Tyrolean-style accommodation (Figure 6C; National Collection of Aerial Photography Archive 3 1944). Aerial photographs confirm the presence of a newly constructed “barbed wire fence [with] watchtowers at the corners” and a main gate, which witnesses report displayed the words “SS-Lager Sylt” (Kukuła Reference Kukuła2003: 11). The camp was divided into two separate compounds—prisoner and SS sections—via a stone-covered wall and gateposts (both of which were recorded during the archaeological survey), and featured a central roll-call square (Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 29; Bonnard Reference Bonnard1991: 75). Desk-based assessments and fieldwork reveal that in early 1943, the eastern boundary wall of the prisoners’ compound ran parallel to the cliff road that initially surrounded the camp. There were also reinforced stone walls surrounding the SS orderly room and quarters. Exposing and mapping the position of steps, gateposts and surviving sentry posts illustrates the various routes in and out of the camp (Figure 7).

Figure 7. 2D plans showing: A) the function of each structure; and B) remnants recorded during archaeological investigations (images: Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University).

These heightened security measures helped to control the prisoners and are consistent features of other European concentration camps (Jaskot Reference Jaskot2002). The security measures also had a psychological effect, reminding prisoners that they were confined to designated spaces, with consequences for attempted escapes. This mental torment was probably exacerbated by the island's terrain and remoteness, which limited the opportunities to escape should prisoners breach the camp boundaries. Several accounts describe how escaped prisoners often returned to Sylt when they realised how difficult it was to obtain food and transport once outside the camp (Archive 9 1945). For sport, the SS guards sometimes used dogs to force prisoners through security fences. The prisoners were then shot for attempting to ‘escape’ (Archive 2 1947; Bonnard Reference Bonnard1993: 68). The SS documented many such executions as ‘suicides’ (Bonnard Reference Bonnard1993: 175).

Accounts describing the camp's boundaries and gateposts also frequently mention that these spaces were used to inflict punishment on prisoners. Several such accounts describe the surviving stone wall supporting the barbed wire fence around the prisoners’ compound as the location of brutal treatment. The German corporal Otto Tauber, for example, recalled how four men were bound to the barbed wire fence atop the wall and whipped for killing and eating a lamb (Archive 4 1945–1948). The gateposts were also a favoured place for the SS to perpetrate and display brutality. A former Norderney prisoner explained: “at Lager Sylt we saw a Russian, he was just hanging, strung up from the main gate. On his chest he had a sign on which was written: ‘for stealing bread’” (Archive 11 undated). Others were left hanging for days and whipped or had cold water poured over them all night until they died (Archive 9 1945; Archive 10 1945). Bodies were left to hang as a warning to others not to commit crimes (Archive 11 undated). Even the German garrison on Alderney were aware that Sylt was a brutal camp, to which access was restricted. While visiting Sylt in 1943, Taubert explained that “no one [in the Wehrmacht] was allowed to enter the inner [prisoner] compound”, and German Lieutenant D.R. Schwalm stated that “access to the camp was only allowed with the permission of the camp-leader and then only in his presence” (Archive 4 1945–1948).

Surviving traces of camp buildings

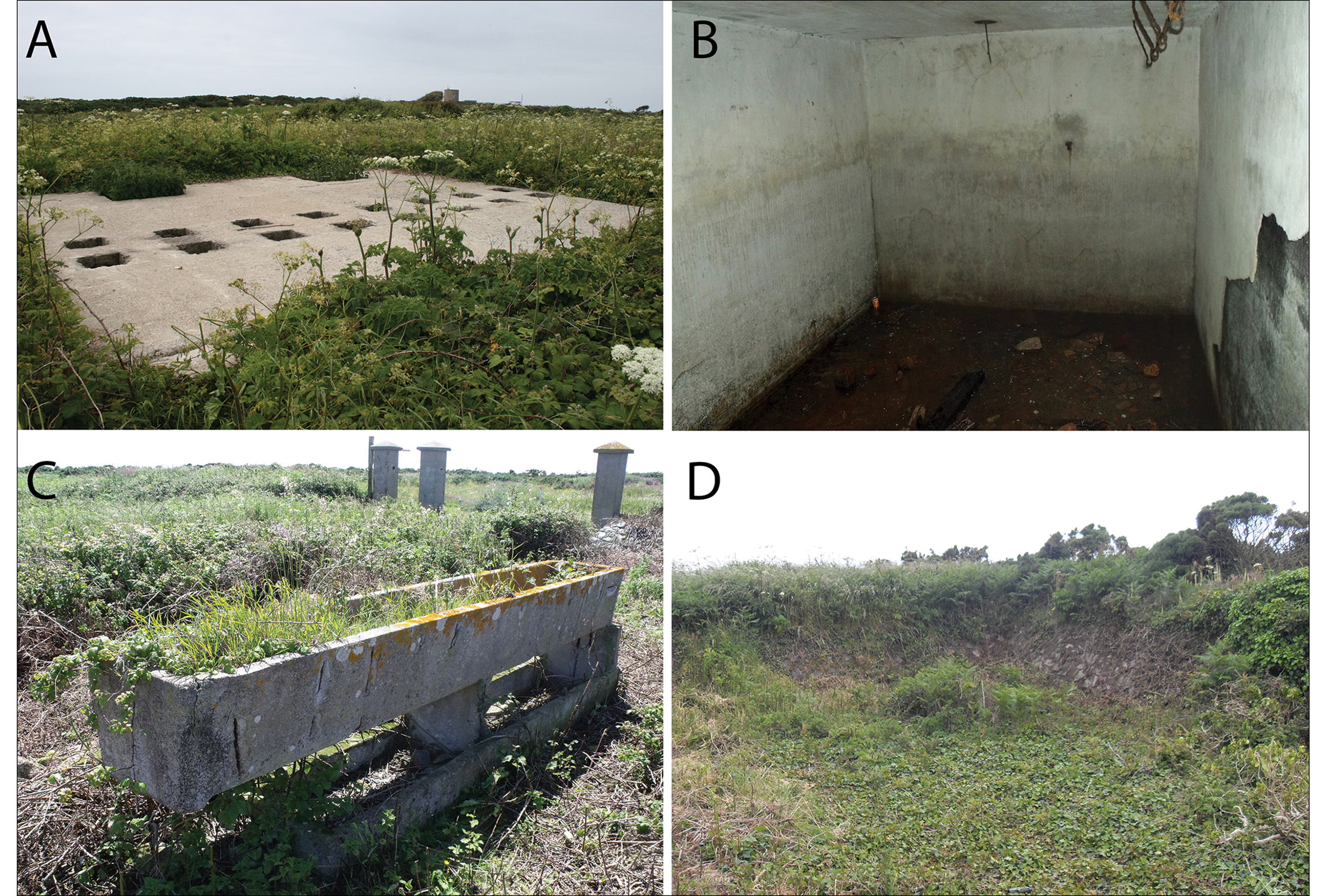

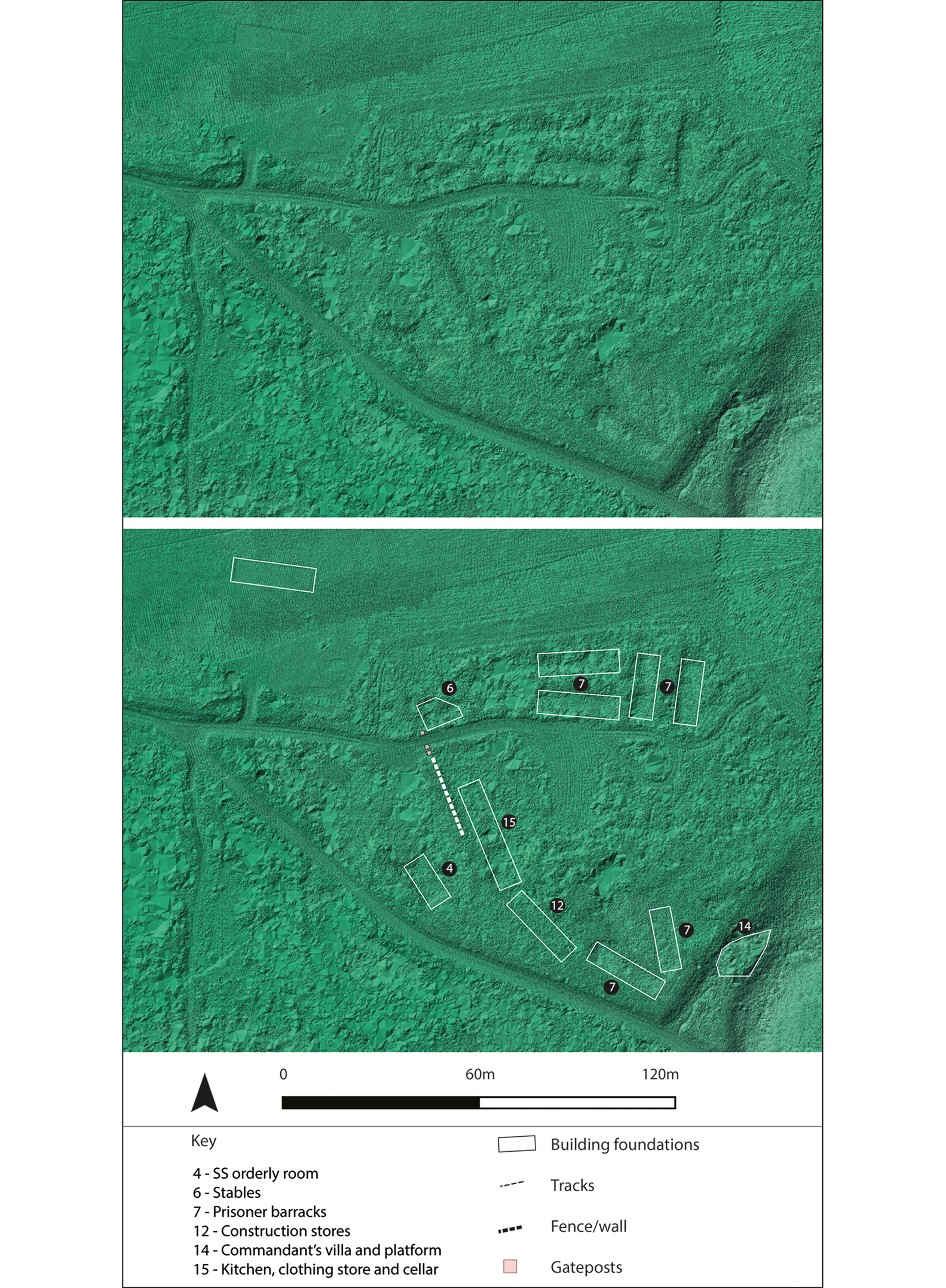

Within the camp boundaries, archaeological fieldwork has revealed an abundance of extant evidence (Figure 7B). Since 1945, the locations of the SS quarters and washrooms have been incorporated into Alderney's airport; the remaining structures are on privately owned land. Thirty-two surface features were recorded, including four boundaries, five structures within the SS sections, two in the Commandant's and 21 in the prisoners’ sections. Notable structures hidden under vegetation in the prisoner area include the toilet block and bathhouse, stables, and a kitchen with an accompanying subterranean cellar. Remains of the SS canteen, workshops and guardroom were revealed in the SS area (Figure 8D). Sentry posts, gateposts and the remnants of the camp fences also survive. The lidar and geophysical survey data reveal extensive evidence surviving beneath the ground's surface, including the foundations of prisoner and SS barracks, the sickbay and construction office (Figure 9).

Figure 8. A) The toilet block; B) prisoner kitchen cellar; C) stable block; D) the SS orderly room (photographs: Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University).

Figure 9. Lidar survey data showing the surviving traces of the Sylt camp in 2017 (FlyThru and Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University).

The prisoner barracks survive as shallow depressions, with buried concrete foundations and associated stairs leading down from ground level. The wooden barracks, which have long since been removed, measured 28 × 8m, each barrack housing approximately 150 prisoners. Given that a large private room reportedly existed for the kapo who resided in each building, each barrack allowed for a maximum of only 1.49m2 of space per person, resulting in extreme overcrowding (Figure 7; Archive 9 1945; Bonnard Reference Bonnard1993: 175). Witness testimonies describe that the conditions in the barracks, coupled with the inadequate provision of sleeping materials, provided a breeding ground for lice (Steckoll Reference Steckoll1982: 75). During the SS's command of Sylt, an outbreak of typhus, spread by lice and poor sanitary conditions, killed between 30 and 200 prisoners (Archive 2 1947; Archive 4 1945–1948). The toilet block, uncovered in 2013, was equally undersized and basic (Figure 8A), although the presence of soap dishes and other objects that survived on the surface suggest that the prisoners had basic personal hygiene provision. The sickbay, located at the rear of the camp and operated by the prisoners, was a simple wooden building. It functioned with inadequate medical equipment and knowledge (Pantcheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 33; Figure 7A). By contrast, the stables for the horses of the SS are well built, with foundations and a concrete trough surviving in good condition (Figure 8C).

Sylt had two eating areas, one for the prisoners and one for the guards. The foundations of both were recorded during archaeological survey (Figure 7). Measuring 22.48 × 12.19m, the SS canteen was larger than the prisoner kitchen, even though far fewer individuals ate there. The prisoner kitchen foundations were recorded over three separate platforms measuring, in total, 19.50 × 6.03m, with several drain or water access points positioned around the foundations. A clothing storeroom also existed within this space, and a subterranean storeroom, which survives with in situ fixtures for food storage, was located to the south-east, next to the foundations (Pancheff Reference Pantcheff1981: 28; Kukuła Reference Kukuła2003: 11; Figure 8B).

Historical sources confirm that the SS used food to enforce dominance and control. Prisoner rations, for example, were stolen by SS guards, who either ate, sold, traded or kept the supplies; island soldiers could acquire cheap meals at Sylt's SS canteen as a result (Archive 9 1945; Bonnard Reference Bonnard1993: 175). Sylt's Commandant, List, was investigated by German military police, who discovered “chests full of sugar, lard, dripping, bacon” (Bonnard Reference Bonnard1993: 175), and German seaman Franz Dokter explained that “almost every day a wangle took place to pass on the prisoners’ rations from the KZ [concentration camp] cookhouse to the SS canteen” (Archive 9 1945). SS entertainment events held at Sylt often served food stolen from prisoners, something that was never questioned by the German officers (Archive 8 1945–1948). One of the prisoner kitchens also became a killing site when, as former Sylt prisoner Wilhelm Wernegau recalled, the cook was strangled by the SS because they did not like his food (Steckoll Reference Steckoll1982: 79; Bunting Reference Bunting1995: 188).

In general—and in contrast to the prisoner area—the archaeological survey revealed that the SS enhanced their areas of the camp to live in comfort and socialise. Many SS structures were constructed from reinforced concrete, and their foundations were excavated below ground level with surrounding stone walling to protect them from the weather and air raids (Figure 8D). The terrace that formerly housed the Commandant's villa is located outside the south-east perimeter of Sylt. In 1944, after the abandonment of Sylt, the villa was moved to Longy Common for use as a private dwelling (Bonnard Reference Bonnard1993: 73). Its original position on lower terrain, facing away from Sylt, gave the villa picturesque views towards the English Channel. Behind the villa was a tunnel that ran underneath the eastern boundary wall into a building, probably a bathhouse, in the prisoners’ compound (Figure 10). Before reaching this building, the tunnel joined a subterranean room. While the existence of these features is well documented, their purpose is less clear. Many hypotheses have been formulated, including an air raid shelter for the Commandant; a quick access point in and around Sylt; or a space through which women could be taken into a brothel within the villa (Sturdy Colls & Colls Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsin press). The date of the tunnel's construction remains unclear, although aerial reconnaissance suggests that it was probably built between February and August 1943 (Sturdy Colls and Colls Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsin press).

Figure 10. Photogrammetry of the tunnel and subterranean room, which connected the Commandant's house to the camp; bottom right) photograph of tunnel (images: Centre of Archaeology, Staffordshire University). The photograph at the bottom right has been updated due to a permissions issue. A notice has been published online and will be included in the next issue.

Photogrammetry and virtual reality visualisation of the subterranean room and tunnel facilitated the documentation of a furnace, traces of pipework, ventilation fixtures, light fittings, marks (such as a handprint and tool marks) and a chute leading from the foundation above (see the online supplementary material (OSM)). All these features were otherwise difficult to record in the field due to poor lighting and, in the case of the ventilation fixtures, the height of the subterranean room (Figure 10). These findings suggest that the subterranean room housed a heating system serving the Commandant's villa and nearby kitchen. It is, however, unclear whether it also serviced the prisoners' bathhouse and the guards’ washrooms, or whether it provided hot water, heat or both. Although it was sealed by substantial doors at either end, the existence of the tunnel is curious, as it seemingly compromised the camp's tight security by providing an entrance and exit connecting the prisoners' compound to the outside of the camp. Although the archaeological survey could not confirm what the tunnel was used for, the discovery of regularly spaced light fittings within suggests that, whatever the tunnel's purpose, it was in frequent use.

Conclusion

The investigation presented in this article is the first of its kind to be undertaken at Sylt labour and concentration camp since government-led inspections in 1945, and the first to use archaeological methods. Walkover survey, vegetation clearance, photogrammetry and lidar allowed surviving evidence to be located, mapped and preserved by record; the combination of these data with historical sources enhances the narrative of events by demonstrating how the architecture, aesthetics and the conduct of the guards of the camp influenced the lives of the inmates and their overseers. Reconstructions offer the opportunity to explore how Nazi dominance and control evolved over time between 1942 and 1944 and its aftermath in 1945. Our work differs from the 1945 investigations—and many other studies of Nazi camps—in that it does not focus on a single period in the camp's history. We recorded consistencies and changes in the way that the camp functioned between the OT and SS periods, challenging the ‘official’ narrative by demonstrating that Sylt's inmates consistently faced terrible living and working conditions. The research highlights that, although in many ways it looked different, as its form was influenced by the surrounding landscape, by mid 1943, Sylt possessed many of the physical characteristics and operational traits of other SS camps in Europe. This is consistent with Sylt forming part of the wider Nazi concentration camp network (Sturdy Colls & Colls Reference Sturdy Colls and Collsin press).

The historical and archaeological study also addressed the fact that the significance of the camp and its setting had become, and remains, ambiguous. The apparent lack of surviving above-ground remains and the perception that Sylt was destroyed were central to discussions in 2015 about its inclusion in the Register of Historic Buildings and Ancient Monuments. During a meeting in March 2015, for example, a committee member stated that “if there were buildings or something there worth conserving, I might have a different opinion; but there is nothing, apart from a broken old wash trough […] and a load of brambles” (Kelly Reference Kelly2015: 41). Archaeological survey has now demonstrated that considerable traces of the camp survive, both above and below ground, enabling us to rewrite the narrative around the destruction of the camp and challenging the notion that there is nothing ‘worth’ conserving.

In December 2017, Sylt was formally listed as a conservation area and it is hoped that our research and resulting 3D models (for an example, see the OSM) will provide useful tools for decision-makers engaged in heritage management, and for any future memorialisation plans at the site. The future of Sylt remains uncertain. Although some members of the local government and community are enthusiastic about developing it into a memorial, there is also fear that this focus on slave labour will show the island in a negative light (Alderney Press 2017: 15). The application of an interdisciplinary suite of non-invasive methods and the resulting visualisations and new knowledge generated have therefore facilitated access to a site that otherwise remains difficult to approach, both physically and politically. While this situation prevails, it is hoped that the historical and archaeological findings outlined here will act as temporary substitutes until more extensive, on-site information and commemorative elements are available, and will raise awareness of an internationally important site that forms part of our collective history.

Acknowledgements

Staffordshire University, the University of Birmingham and the Smithsonian Channel funded this project. Thanks are also due to the Kay-Mouat family for granting access to their land; Aaron Bray, Martin Lunt and Alex Snowden from the States of Alderney for on-site assistance; Alderney Airport staff for assisting with the UAV surveys; numerous staff members and students from Staffordshire University and the University of Birmingham (especially Dante Abate, Tim Harris, Richard Harper and Ruth Swetnam); FlyThru for the lidar and drone surveys; and SnapTV and Fluid Pictures for assistance with the reconstructions.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.238.