Introduction

Adolescence is a key period for the development of sexual and gender identity (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dawes and Plocek2021; Katz-Wise et al., Reference Katz-Wise, Budge, Fugate, Flanagan, Touloumtzis, Rood, Perez-Brumer and Leibowitz2017; Savin-Williams and Ream, Reference Savin-Williams and Ream2007). Within this stage of development, some young people begin to identify with minoritised sexual orientations (e.g. lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, pansexual, and other non-heterosexual orientations; LGBQ+) and/or gender identities (e.g. binary and non-binary transgender identities, different from their sex assigned at birth; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dawes and Plocek2021). For gender- and/or sexuality-minoritised (GSM) adolescents, the combination of having a socially oppressed identity/orientation, alongside the typical developmental stressors, mean that GSM adolescents are at increased risk of adverse mental health outcomes, including self-harm and suicide, compared with cisgender and heterosexual individuals (Adelson et al., Reference Adelson, Stroeh and Ng2016; Butler et al., Reference Butler, Joiner, Bradley, Bowles, Bowes, Russell and Roberts2019; Hendricks and Testa, Reference Hendricks and Testa2012; Kapatais et al., Reference Kapatais, Williams and Townsend2022; King et al., Reference King, Semlyen, Tai, Killaspy, Osborn, Popelyuk and Nazareth2008; Meyer, Reference Meyer2003; Raifman et al., Reference Raifman, Charlton, Arrington-Sanders, Chan, Rusley, Mayer, Stein, Austin and McConnell2020).

One cluster of mental health difficulties associated with self-harm and suicide is borderline personality disorder (BPD). BPD is characterised by a pervasive difficulty with emotion regulation, impulsivity, self-harm behaviours, relationship functioning, and identity instability (Bohus et al., Reference Bohus, Stoffers-Winterling, Sharp, Krause-Utz, Schmahl and Lieb2021). A diagnosis of BPD in adolescent populations is to be provided with due consideration, as many of the symptoms of BPD are normative for adolescence and there are concerns about protecting young people against associated stigma (Kaess et al., Reference Kaess, Brunner and Chanen2014; Swales, Reference Swales2022). However, emerging symptoms of BPD in adolescence are associated with increased chronicity of adult BPD symptoms and have a significant impact on quality of life (Chanen et al., Reference Chanen, Sharp and Hoffman2017; Winograd et al., Reference Winograd, Cohen and Chen2008). Therefore, cautious early identification and intervention in adolescent populations is recommended to prevent longer-term mental health difficulties (Chanen et al., Reference Chanen, Sharp and Hoffman2017; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Muehlenkamp and Jacobson2008; Swales, Reference Swales2022).

Symptoms of BPD have been found to be higher in GSM populations compared with cisgender-heterosexual groups (Anzani et al., Reference Anzani, Panfilis, Scandurra and Prunas2020; Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Sharp, Kalpakci, Choi and Temple2016; Rodriguez-Seijas et al., Reference Rodriguez-Seijas, Morgan and Zimmerman2021). This higher representation might be explained in part by the overlap between typical struggles of GSM individuals and the BPD symptom criteria, combined with clinicians’ potential misinterpretation of culturally normative behaviours (Rodriguez-Seijas et al., Reference Rodriguez-Seijas, Morgan and Zimmerman2021; Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Sharp, Kalpakci, Choi and Temple2016). Examples of culturally normative behaviours may include identity fluidity, self-expression considered different from the mainstream, and more diverse ranges of sexual/romantic behaviours and relationships, which may be judged as indications of identity and relationship instability within the BPD construct. Another argument is that GSM individuals are heavily exposed to minority stress and traumatic events, such as childhood abuse (Warren et al., Reference Warren, Goldsmith and Rimes2022). On top of everyday stressors, this may contribute to the development of difficulties associated with BPD (Pantalone et al., Reference Pantalone, Sloan, Carmel, Pachankis and Safren2019).

The latter notion fits with Linehan’s (Reference Linehan1993) biosocial theory of how BPD symptoms develop. This model suggests that a person probably has temperamental vulnerabilities to an emotion sensitivity (as one example) and/or early characterological differences (i.e. childhood gender ‘non-conformity’; Grove and Crowell, Reference Grove, Crowell and Swales2019), which increases their risk of invalidation in the environment and/or adverse or traumatic life events. A developmentally invalidating environment is one that dismisses and fails to acknowledge the validity of an individual’s internal experiences. This can also be an environment which punishes self-expression, over-simplifies problem solving, and reinforces emotion-escalation to get needs met (Grove and Crowell, Reference Grove, Crowell and Swales2019; Pantalone et al., Reference Pantalone, Sloan, Carmel, Pachankis and Safren2019). This model posits that chronic invalidation and its transactions with personal ‘vulnerabilities’, may prevent the development of adaptive emotion regulation strategies, all of which can result in emotion dysregulation and corresponding pervasive dysregulation in other areas of life (e.g. behaviours, relationships, identity, and cognitions; Linehan, Reference Linehan1993).

Congruent with minority stress theory (Hendricks and Testa, Reference Hendricks and Testa2012; Meyer, Reference Meyer2003), the biosocial model offers a potential explanation as to why GSM adolescents may be at increased risk of emotion dysregulation, self-harming behaviours, and other difficulties associated with BPD. This may be due to increased exposure to a socially oppressive environment which likely communicates and encourages the internalisation that GSM identities and experiences are invalid and unacceptable (Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Sharp, Kalpakci, Choi and Temple2016; Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Berke and Shipherd2017). Socio-political oppression and traumatic experiences constitute extreme invalidating experiences, which can result in traumatic invalidation (Cardona et al., Reference Cardona, Madigan and Sauer-Zavala2022; Harned, Reference Harned2022), all of which can cause further deterioration in coping resources, increased distress, as well as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, even in the absence of a ‘Criterion A’ traumatic event (Cardona et al., Reference Cardona, Madigan and Sauer-Zavala2022; Grove and Crowell, Reference Grove, Crowell and Swales2019; Harned, Reference Harned2022; Hatzenbuehler, Reference Hatzenbuehler2009; Reuter et al., Reference Reuter, Sharp, Kalpakci, Choi and Temple2016; Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Berke and Shipherd2017).

Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT; Linehan, Reference Linehan1993) is a third-wave cognitive behavioural therapy that is effective in reducing emotion dysregulation, self-harm, suicidality, and other symptoms associated with BPD (Johnstone et al., Reference Johnstone, Marshall and McIntosh2022; MacPherson et al., Reference MacPherson, Cheavens and Fristad2012). DBT is also recommended by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence for young people experiencing emotion dysregulation and self-harming behaviours (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022). The evidence for the effectiveness of DBT for GSM youth is in its infancy. One small-scale study found similar outcomes for sexuality-minoritised youth compared with heterosexuals (Poon et al., Reference Poon, Galione, Grocott, Horowitz, Kudinova and Kim2022). Retrospective disaggregated analyses of randomised controlled trial data for DBT in adult populations also found that sexual minority status did not have a relationship with outcomes (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Halvorson, Lehavot, Simpson and Harned2023). No studies have investigated disaggregated outcomes for gender-minoritised youth.

Early efforts have been made to apply Linehan’s (Reference Linehan1993) adult biosocial model to gender and sexuality minority stress to explain why GSM individuals may be more likely to experience psychological distress and/or BPD-related symptoms (Camp, Reference Camp, Semlyen and Rohleder2023; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2021; Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Whicker and LeMaire2019; Pantalone et al., Reference Pantalone, Sloan, Carmel, Pachankis and Safren2019; Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Berke and Shipherd2017; Tilley et al., Reference Tilley, Molina, Luo, Natarajan, Casolaro, Gonzalez and Mahaffey2022). Qualitative research has further explored how DBT can be applied to supporting transgender and non-binary youth (Tilley et al., Reference Tilley, Molina, Luo, Natarajan, Casolaro, Gonzalez and Mahaffey2022). Two studies have also adapted aspects of the DBT skills training group for GSM adults and found the adaptions to be acceptable (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2021; Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Mirabito, Kirkman and Shaw2021).

No study has yet explored the experiences of GSM adolescents in a standard DBT programme (i.e. one which has not been specifically adapted for GSM-associated needs), nor sought the advice of young GSM people about how DBT may apply to their needs. This is important as there is a dearth of research looking at the experiences of GSM adolescents in psychological therapies, such as DBT. This is despite findings that GSM individuals have poorer experiences of and face significant barriers to accessing mental health care (Bindman et al., Reference Bindman, Ngo, Zamudio-Haas and Sevelius2022; Dunbar et al., Reference Dunbar, Sontag-Padilla, Ramchand, Seelam and Stein2017; Foy et al., Reference Foy, Morris, Fernandes and Rimes2019; Hafeez et al., Reference Hafeez, Zeshan, Tahir, Jahan and Naveed2017; UK Government Equalities Office, 2018; McDermott, Reference McDermott2016; Pachankis, Reference Pachankis2018; Williams and Chapman, Reference Williams and Chapman2011). In addition, there is some evidence for worse outcomes for sexuality-minoritised adults compared with heterosexual individuals in mental health services (e.g. Rimes et al., Reference Rimes, Ion, Wingrove and Carter2019). It is therefore not yet clear how acceptable standard DBT is for GSM adolescents or whether there are GSM-associated treatment targets that may be important to consider in DBT. Therefore, this project aims to understand:

-

(1) Whether GSM adolescents receiving DBT experienced difficulties relating to their sexual and gender identity in their everyday lives, and which of these they thought were important to include in DBT (whether it was targeted or not).

-

(2) Adolescents’ perceptions of how well DBT met their needs as GSM individuals and how effective the approach was for supporting them with GSM-associated difficulties.

-

(3) Suggestions for improvements in how DBT could better support GSM young people.

Method

Ethical considerations

The South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust Clinical Governance CAMHS Audit and Service Evaluation committee provided ethical approval for this study. Young people provided informed consent to take part. Parent/carer participation was not required for participation in this study, with the exception of if participants were below the age of 16 years old and thus needed parent/carer consent for participation. Where consent was required from parents/guardians, participants were informed that parents/guardians would become aware of the research focus in order for them to provide consent. Therefore, young people could decide whether to participate knowing that this may reveal information related to their sexual or gender identity to parents/guardians.

The research team and service context

The research team consisted of a range of professional backgrounds, including two senior clinical academic psychologists, two senior DBT therapists (one clinical psychologist and one systemic psychotherapist), and one clinical psychologist training to be a clinical academic psychologist. Support was provided by an assistant psychologist to complete some interviews.

A description of the first author’s characteristics and relevant context is included to provide insight into the lens and experience that shaped their analysis of the data. At the time of writing, their gender identity was non-binary (male assigned sex; he/they pronouns) and sexual identity was queer/gay. Their cultural and ethnicity-related background was predominantly working-class White British, with a proportion of the family from Roma-Gypsy roots. The important socio-political environment in their younger years, as a developing queer person, were shaped by Section 28 (Local Government Act, 1988), which prohibited the promotion of ‘homosexuality’ in schools; the latter end of the AIDS epidemic; and other anti-LGBTQ+ legislation and social norms. These contexts, alongside familial mental health struggles and trauma, are the foundational experiences for their work and interpretation of data within this project.

This study was conducted in a national and specialist DBT service for adolescents, based in the UK’s Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS; NHS). This out-patient DBT programme is based on the DBT model for adolescents (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Rathus and Linehan2006; Rathus and Miller, Reference Rathus and Miller2015). All core modes of DBT are provided including weekly individual therapy sessions, weekly skills teaching groups for young people and a separate group for parents/carers, telephone coaching, family sessions as needed, and a weekly team consultation meeting. Parent and carer interventions are informed by the DBT for parents, couples and families model (e.g. Fruzzetti, Reference Fruzzetti and Swales2019). This service context has deviations from the original DBT for adolescents model, such as a separate parent/carer group rather than multi-family skills group, to allow implementation in a tier-4 national health service context (see Camp et al., Reference Camp, Hunt and Smith2023 and Smith et al., Reference Smith, Hunt, Parker, Camp, Stewart and Morris2023 for further explanation). Further details of this service context can be found in Camp et al. (Reference Camp, Hunt and Smith2023).

It is of note that the proportion of GSM young people who are referred and assessed as suitable for this national DBT programme is high, 63–65% and 11–17%, respectively, compared with the proportion in the UK population (Camp et al., Reference Camp, Hunt and Smith2023; Camp et al., Reference Camp, Durante, Cooper, Smith and Rimesin press; Office for National Statistics, 2021a, 2021b). As DBT is largely principle driven, there is scope and flexibility to include experiences relating to GSM identities and minority stressors in aspects of the programme. However, these are reliant on the young person or therapist bringing these topics and are guided by a treatment hierarchy stipulating life-threatening and therapy-interfering behaviours as the priority before quality-of-life-interfering difficulties are addressed (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993). Therefore, no specific adaptation was made to this programme for GSM-associated needs, although there is scope to work on these potential needs if the young person and therapist identifies it as a treatment target on the hierarchy or as a key controlling variable related to those targets.

Participants

Fourteen GSM young people who were undergoing the DBT programme took part in this study. Young people were invited to take part in the study if they identified as GSM and were in the DBT programme at the time of recruitment (October 2021 to August 2022) and had completed at least the first six months of the DBT programme (thus they had completed each skills group module). Twenty-three young people were suitable to take part in this study and were invited. Five did not respond to initial offers of participation, thus it is not possible to know the reasons for not opting in. Two declined participation due to not feeling ready to discuss aspects of their sexual and gender identity, and two initially opted in but did not respond to subsequent invitations to interviews for unknown reasons.

Design and procedure

This study employed a qualitative design guided by the reflexive thematic analysis model (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021). Young people who met the inclusion criteria were identified by checking responses to sexual orientation and gender identity questions at assessment, checking treatment stage via service-held records, and asking allocated clinicians to identify suitable candidates. Consent to be contacted by the first author was requested by their allocated therapist. If consent was provided, the first author contacted the young person to provide further information about the study and if they were interested in taking part, and sought informed consent for participation. Participants below the age of 16 years provided assent and their parents/carers were contacted, with their permission, to gain informed consent. Following informed consent, participants were invited to a 20- to 40-minute interview facilitated on video conferencing software. The software recorded and transcribed the interviews. Participants were asked to choose a pseudonym to de-identify their data and then were asked the most appropriate labels to describe their sexual orientation and gender identity. The semi-structured interview asked questions pertaining to their experiences in DBT as a GSM young person and about GSM-related factors associated with their mental wellbeing. Prompting questions were asked as needed. The topic guide was developed by the lead author in consultation with the remaining authors and a young GSM person in the DBT programme. Participants were given a £10 voucher as recompense for their time and invited to access support from their DBT therapist via telephone coaching if needed after the interview. The first author conducted most of the interviews; however, an assistant psychologist, under supervision of the first author, conducted interviews with three participants who were working with the first author clinically.

Reflexive thematic analysis

A reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021) approach was used. Data were analysed with an experiential orientation and essentialist approach to privilege the language chosen by the young people to describe their experiences. Similarly, an inductive ‘data-driven’ approach was used for the generation of codes and themes based on the data. Latent coding approaches were used when the meaning of the data was not clear. However, as the familiarity with the data increased, a more critical, constructionist and deductive orientation/approach increased, informed by the first author’s knowledge of the DBT model and psychological models explaining mental health disparities in GSM individuals. Influential models for the first author included the minority stress (Meyer, Reference Meyer2003; Hendricks and Testa, Reference Hendricks and Testa2012), psychological mediation frameworks (Hatzenbuehler, Reference Hatzenbuehler2009), models detailing a social justice lens on scientific endeavours in this area (e.g. Pachankis, Reference Pachankis2018), and self-acceptance models (Camp et al., Reference Camp, Vitoratou and Rimes2020; Camp et al., Reference Camp, Vitoratou and Rimes2022). The first author also has particular interests in frameworks adapting DBT and similar models to minoritised groups (e.g. Pantalone et al., Reference Pantalone, Sloan, Carmel, Pachankis and Safren2019; Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). A reflexive log was kept by the first author throughout data collection and analysis in order to track idea development and the relationship with their personal and professional characteristics. This log often featured the linking between data, the aforementioned theories, and the first author’s context (see above), with attempts to refer back to the explicit meaning of the data. The first author noted, within their log, many experiences of relating personally to the experiences of participants, seeing common themes often detailed in minority stress theories, and being reinforced by participants to disseminate the learning to clinicians and researchers to improve practice.

The data analysis followed the six phases outlined by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2021). Phase 1: data familiarisation was undertaken by the first author by listening to the interviews and checking over software-generated transcripts, and then re-listening to each participant at least twice in random order. Phase 2: the initial generation of codes was completed on the transcripts by the first author and then reviewed with each transcript. All codes were then checked alongside their assigned data to ensure that the codes were accurate reflections of the data. Phase 3: codes began to be sorted together based on collective meaning at the code level, collapsing these into initial candidate themes. Phase 4: a process of re-engaging with the codes and data for the entire dataset informed revisions of the candidate themes, alongside consideration of the theme boundaries, quality, coherence and interactions. Mind maps were used to help review the data at the over-arching theme and theme level. This was done with the support of co-authors and an independent researcher. Phases 5 and 6: themes were then defined, named, and arranged together in an early draft results section alongside supporting quotes from the data. This writing process allowed for further opportunities to re-check codes and data and revise themes. At this stage an independent researcher checked over the themes and quotes, and referred back to the codes and data, to provide detailed feedback. A second draft was created based on the feedback. The results section was then reviewed by two GSM young people with lived experience of undergoing DBT and the remaining four authors in various iterations, and revisions were made based on their feedback. The results underwent multiple revisions within this phase.

Results

Sociodemographic variables and sample attrition

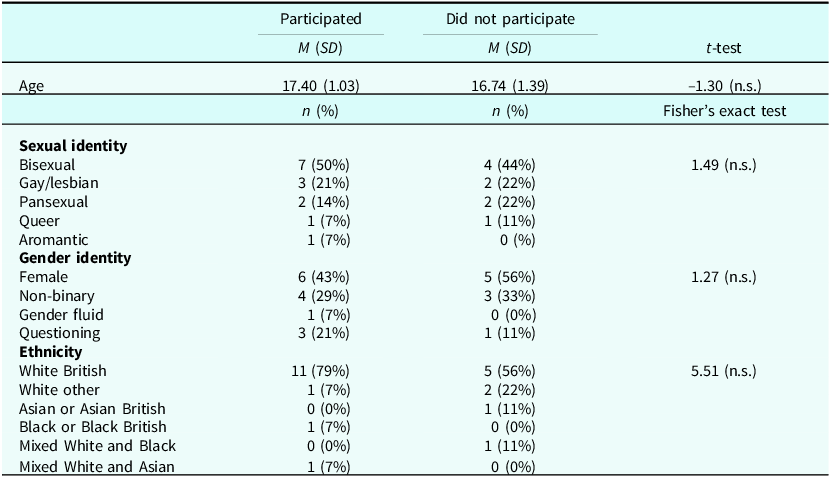

Sociodemographic variables are presented in Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics did not significantly differ between those who participated and those who did not, but there was emerging variability in more young people from minoritised ethnicities not participating (see Table 2).

Table 1. Sample sociodemographic variables

Table 2. Sample attrition characteristics

n.s., not statistically significant at p=<.05; 100% of both groups were female sex assigned at birth.

Thematic analysis results

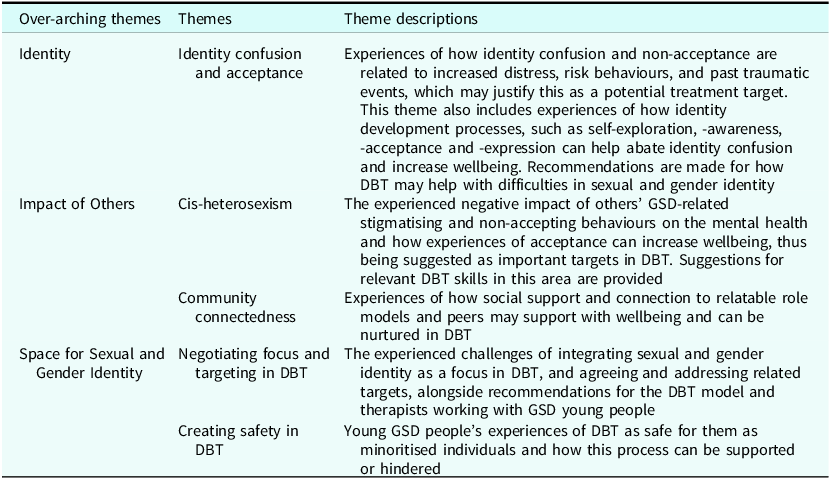

A summary of the themes and subthemes are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Theme summary

Over-arching Theme 1: Identity

The ‘Identity’ over-arching theme organises the experiences of GSM young people in relation to confusion and arising distress associated with sexual and gender identity alongside potential self-discovery and -acceptance processes that may reduce distress and confusion. These were highlighted by participants as helpful to target within DBT.

Theme 1A: Identity confusion and acceptance

Ten of the 14 young people reported experiencing distress and confusion in relation to their sexual and gender identity while in DBT and felt that this was important to target in therapy. Gender identity was often associated with more confusion and distress compared with sexual orientation, as illustrated by Sage: ‘… I’ve been completely comfortable with my sexual orientation. It’s more … gender identity that … confused me and … made my mood change…’. Some cited sexual- and gender-identity-related confusion and lack of self-acceptance as a contributor to psychological distress (Ellis: ‘Because, for a long time I didn’t have… [self-acceptance] and It was very, very distressing’). Others described this as contributing to risk behaviours (i.e. self-harm, eating-disordered, and sexually-risky behaviours) to cope via distraction, self-punishment or generally. This was articulated by Sawyer: ‘I found both [sexual and gender identity]… equally confusing and that sort of drove me to focus more on … disordered behaviours at the time and … using self-harm as distraction or becoming … deeper into disordered eating’.

Some young people described that identity-confusion and -non-acceptance was related to the internalisation of stigma and self-invalidation. Aoife said: ‘I think [I worked on]… shame [in DBT]. Whether it’s like internalise[d] … homophobia or difficulties with accepting yourself, how that might link into … self-harm and -punishment and … those feelings are quite difficult to cope with’. Participants also hypothesised that their identity confusion was associated with past traumatic events. Experiences of sexual and emotional trauma were reported to increase confusion with sexual and gender identity, including struggling to know whether sexual and gender identity was a product of trauma. For example, Avery said:

… I can’t tell if [asexuality is] something … to do with like my current … mental state …, or whether this is like a part of myself that I would need to accept … I know some other people who also gone through similar… [traumatic] sexual experiences in the past and … now we’re in a similar position where …

Others described how their sexual and gender identity can change to dissociate from past versions of themselves that were the victims of the trauma, and that desired identity changes sometimes functioned to better protect the self from others (e.g. more masculine identity expression may be less vulnerable to harm compared with feminine). However, this was thought to further increase identity confusion; see example by Phoenix: ‘… I think my … switching gender or like my unstable … how I view my identity … [is] linked to… trauma… because it’s like I’m trying to … dissociate from … how I was at that period of time’.

Participants discussed how identity confusion could also be linked to attractions, sexual behaviours, and relationship types, and the resulting judgements of what this means for their sexual and gender identity. For example, Koda described the experience of having sexual or romantic attractions to the opposite sex, and this resulting in them questioning their sexual orientation and judging themselves as not truly being bisexual or pansexual, thus contributing to the pain of identity confusion:

… If I feel attracted to a man, I’m suddenly like, what if I’m faking it and I’m actually straight and then I feel attracted to women and it’s like I’m actually lesbian and now I don’t know what to do.

The young people described how an incongruence between how they understand and express their sexual and gender identity, such as through their appearance, also increased confusion and distress. Learned majority-held ideas about stereotypical gender expression further contributed to gender-identity confusion, and made gender identity harder to accept; Kit said: ‘I feel like there’s a very strict idea of like being transgender … I don’t know, even though I am non-binary, [if] I can call myself transgender as I still present very femininely’. Sage also described, in the context of pregnancy, their experience of how an incongruence between their ideal gender expression and how their changing body caused distress and difficulties with self-acceptance:

I got pregnant and then that made things … difficult because I’ve just been so confused, because my body is … doing all these changes and … I can’t like express how I want to express … Some days … I’ll get really upset … Identifying as non-binary has given me … gender dysphoria … I feel really down because I’ll look at myself and I’m like: oh, I look horrid. I don’t want to look like this and so that will just make me feel more depressed or my anxiety will be higher.

The young people acknowledged that it may be beyond the scope of DBT to provide some of this support; however, they felt there was a role for DBT in supporting them with accessing the appropriate support and navigating the system.

Participants suggested skills that they found or thought to be helpful for managing the pain of identity confusion. One suggestion included building tolerance and acceptance of not knowing their sexual and gender identity entirely, or that things may change over time, using dialectical thinking (e.g. to move away from ‘black and white thinking’) and reality acceptance; Phoenix said:

I guess coming to terms of the fact that I don’t have to be [at] like either end of the spectrum and … not thinking too harshly about … knowing, like, my gender or sexuality … So like thinking … I’m like fine not knowing … Just like all those skills, that like involve … acceptance … I don’t know if it would go as far as like as radical acceptance, but just like … noticing how I am feeling … com[ing] to terms with the fact that I don’t really need to … know.

Mindfulness of thoughts was also recommended to help diffuse from identity-confusion and internalised-homophobic thoughts, exemplified by Remy:

Whenever I thought about … negative thoughts and I would just pretend that it was like someone that I thought was really stupid … I think especially when it comes to like internalised homophobia … or doubting the way that you view your sexuality and gender identity, that would definitely help.

Participants recommended validation that identity confusion is normal and understandable (e.g. Koda: ‘[it is important to] validate … how confusing [sexual and gender identity] could be or validating that it’s normal to feel some negative thoughts associated with it, but it doesn’t mean … [it’s] true’), as well as pausing and checking the facts when noticing identity confusion to help disengage from this process and check in with wise mind (e.g. Jordan: ‘every time I question myself, I stop and I say “why am I questioning myself”; that’s something that [DBT therapist] taught me: to stop and check it over, and hang out with my wise mind’).

Exploring and building awareness of one’s sexual and gender identity, and self-accepting these parts of the self, were often cited as possible antidotes to identity confusion and associated distress, to managing stigma experiences, and for disclosing identity to others where there are concerns about non-acceptance by others. For example, Jordan said: ‘For people to have such a negative impact on [my sexuality] and see how damaging it is … In accepting my sexuality … it helped me accept myself a lot because it’s a big part of who I am …’. Participants also described how DBT had or could support with the development of self-acceptance and -awareness, with aspects such as self-confidence and self-expression being cited as important mechanisms to target. For example, Avery said: ‘DBT … gives you … the confidence to go out there and discover who you are. And, as you discover … your sexual orientation … you naturally become more confident in yourself and who you are … you feel more comfortable to … accept them…’. Generally, participants noted that improving self-acceptance, self-awareness, and authentic self-expression is likely an important focus in DBT for GSM young people and would likely decrease distress. For example, when asked what things associated with sexual and gender identity were important to target in DBT, Cyrus said: ‘acceptance … of your own identity’.

The participants offered specific suggestions of DBT skills that may be useful for improving self-acceptance, including: mindfulness to improve self-understanding and reality acceptance for accepting sexual and gender identity; self-soothe to support recovery from experiences of not self-accepting and of self-invalidation; and acting opposite to unwarranted shame associated with sexual and gender identity. For example, Ellis described using a number of DBT skills to help improve self-acceptance:

[I recommend]… a bit of self-acceptance, bit of radical acceptance, a bit of self-soothe as you’re feeling horrible and … dysphoria is really sticking to you … Self-soothe or the opposite action [skill] … That was really good … If you’re feeling shame … over, like dysphoria.

Finally, the participants explained how DBT interpersonal effectiveness (e.g. DEARMAN; an assertiveness skill in DBT; Linehan, Reference Linehan2015) and emotion regulation skills (e.g. wise mind values) could be used in relationships to assert their sexual and gender identity and related needs, and to act with self-respect and -acceptance. For example, Avery said:

I feel as though … when you have to do [DEARMAN and FAST], you have to really trust yourself … and the more you … do that, the more you trust like different areas of yourself and your identity … who you are…. [Also], figuring out what my values are, like to know who I am better and I think things like that really helped me … feel a lot more comfortable in myself …

Over-arching Theme 2: Impact of Others

The ‘Impact of Others’ over-arching theme captures the ways in which relationships can potentially impact on the mental wellbeing of GSM young people, both generally and in the context of being in a DBT programme.

Theme 2A: Cis-heterosexism

Participants reported experiencing a spectrum of cis-heterosexism, from the subtle to the overt. On the more subtle end, some experienced indirect and potentially unintentional communications of prejudice, erroneous assumptions, or a lack of understanding (otherwise referred to as microaggressions). For example, in relation to sexual identity, Jordan discussed the stress of encountering a past clinician (outside of DBT) who assumed they were heterosexual and how this made further discussions around sexuality difficult:

… [My previous clinician] was like: I assume … you’ve got a boyfriend … I then had to explain that that’s not my preference and she then assumed I was bisexual because I said preference … it was frustrating … After that conversation it just kinda was left unspoken …

Others experienced stigma and presumptions about their sexual identity, including that identifying as bisexual would mean they are more likely to engage in infidelity or be promiscuous. Remy said: ‘Stigma around being bisexual … because … you could go down different options and … people [are] like: oh, you might cheat. That’s caused serious problems’. Some participants talked about others communicating to them that being less obviously ‘queer’ would be more socially acceptable and that less overt self-expression would be preferred to avoid cis-heterosexism. For example, Amari said: ‘People who … don’t voice [their sexual and gender identity]…, ’cause you do get people who are homophobic…, [and] I do feel like they get more accepted than people who … make it their entire personality…’. Participants also described others making assumptions about gender identity and mis-gendering with incorrect pronouns, as well as sexuality-based assumptions such as a non-heterosexual identity meaning they will not have children. For example, Kit said: ‘I’ve been in … a relationship with a guy and … [he said] I don’t see you as a women, but then consistently used the wrong pronouns … [This left me] wondering like, does this person accept me…’.

The participants also described stress caused by having to explain their identity to others and feeling invalidated by a lack of understanding about their identity. For example, Haze said: ‘There’s a problem … trying to explain what [gender fluid and pansexual] mean … because people [are] like: oh so you [have sex with] pans … and what about animals?’. Participants also highlighted the damaging effect of having normative identity confusion, related to GSM, pathologised. Some experienced the diagnosis of BPD and related ‘identity disturbance’ as invalidating. Aoife said: ‘… I sometimes feel I’ve been made to feel like my experiences [regarding my gender and identity disturbance] aren’t really real [and instead are]… more a symptom of… [the borderline] personality disorder diagnosis’.

Participants described how non-acceptance and invalidation by others caused emotional pain and made it harder to feel they could access social support. Conversely, they reported that feeling accepted and understood by others was an important factor for their wellbeing and part of their vision for a better society. Participants felt that minoritised sexual orientations tended to be more accepted and understood by others compared with minoritised gender identities. For example, Aoife said: ‘the bisexual label is more easy for people to tolerate than the fact that I might be interested in having different pronouns’. Others felt rejected by religious ideology; Koda said: ‘… I start thinking: what if I am going to go to hell, or like: … this is really bad … It’s mostly just religion … I don’t believe in God, but I still believe that God might hate me’. Participants also described that a lack of parent/carer involvement in DBT made it difficult for them to feel understood and accepted by their parent(s)/carer(s), and thus made them less accessible for support. Sage said:

[the lack of my parent/carer lack of involvement in DBT] made it … more difficult to talk with them about [sexual and gender identity]… if I can’t go home and be accepted, like, then that … made me feel a bit like oh well … I shouldn’t be like this … It was … just really frustrating because … it potentially would have helped [my parents/carers] to understand my identity … better and how to be accepting and not as judgemental …

Participants reported experiences of direct verbal and physical aggression by others. Examples of verbal aggressions included slurs when showing affection in public with a same-sex partner or generally in school. Jordan said: ‘To go out in public with someone that I love and I’m with … when people make slurs and comment, you just want to shake them …’. Participants also reported being outed non-consensually and experiencing bullying due to their sexual and gender identity. Remy said: ‘I got outed in secondary school and that caused a lot of problems because I was in a very homophobic environment … I did get a lot of homophobic things thrown at me’. In addition, some reported experiences of physical aggression and discrimination by others, including being segregated from others due to sexual orientation and being sexually harassed in order to disprove their minority sexuality. For example, Jordan said:

I was bullied at school … I was jumped and the teachers banned me from swimming … [and] changing with the girls because I was the only known lesbian … [Also], there is … someone the same age as me. He’s been harassing me because I refused to have any sexual contact with him [after] I told him I was a lesbian …

Generally, participants suggested these experiences increased psychological distress and difficulties trusting others, thus felt they were potentially important to work on in DBT.

Others endorsed how it was often the expectations and worry about others’ rejection, judgements and stigma-related behaviours that caused distress, even if they did not have direct experiences. These fears negatively impacted wellbeing and prevented the disclosure of sexual and gender identity to others. For example, Ellis said:

[I have] worries about what if … I fall in love with someone who’s like: I don’t like you because you’re non-binary … I worry about all the different stuff that people can do if you’re openly queer. I just worry about making friends and going to work and getting a job and … what if I can’t … adopt children because I’m non-binary …

Participants highlighted a range of DBT skills that can be helpful for managing cis-heterosexism, and the concurrent anticipation of these. Some reported ‘checking the facts’ when experiencing negativity to remind themselves that others’ opinions are not fact. For example, Asriel said: ‘The fact checking when it comes to negativity and people pro and conning your sexuality … really helps… [to remind yourself that] peoples’ negativity isn’t fact’. Participants also reported using the skills group to gain peer support from other young people. Jordan said: ‘It helps me a lot to see the other young peoples’ views on it … Keeping down my anxiety about something bad happening because of our sexuality [in public] … Skills [group] did help a lot with … that’. They also suggested pros and cons for considering whether to come out despite the risk of others’ reactions. Amari said: ‘… pros and cons … [if] I’m coming out to somebody … [and to consider] their reactions …’. Some suggested assertiveness skills (i.e. DEARMAN) to challenge things like transphobia and advocate for acceptance by others, as emphasised by Ellis: ‘[I recommend] … DEARMAN for … confront[ing] people like when they’ve been transphobic’. Others suggested cope ahead plans and reality acceptance skills (i.e. half smile and willing hands, which are body-based changes to increase reality acceptance and willingness; Linehan, Reference Linehan2015) when necessary to tolerate non-acceptance by others. For example, Haze suggested: ‘… half smile and willing hands [would be useful] … when you’re trying to explain … the meaning of pansexual and gender fluid, … to … help deal with their … ignorance …’, and Koda said: ‘If … you think you might be dealing with someone or …, if it’s a family member who isn’t accepting then the cope ahead skill could be useful’. More support around coping with bullying and discrimination and a desire for more psychoeducation on the link between stigma and mental ill-health was also suggested to optimise DBT for GSM adolescents; Aoife said: ‘[I recommend] Just thinking about the … impact that … homophobia or transphobia … can have, how it can link into, like the abandonment and rejection thing’.

Theme 2B: Community connectedness

Many participants described how feeling connected to other GSM people and having a sense of belonging was important for their wellbeing and normalising their experiences as GSM young people. Amari explained:

When I was first … discovering [my sexual orientation]… I did feel relieved once I … found there’re other people like me and I … felt … at peace where I stand … I think there should be like some offering [to support with this in DBT] because quite a lot of people are in the [GSM community] … and … go through these issues …

Meeting GSM peers in the DBT skills group was experienced as supportive and recommended as useful for other GSM young people in distress. For example, Remy said: ‘In the group it was just very nice … to see that other people related to me … and that there was a really nice and comfortable space for me to talk about … [sexual and gender identity]’. Participants reported on the importance of seeing ‘queer” role models, both in their families, where there was GSM representation; in public; and in the DBT team. It was remarked that some young people, including Ellis, would like to see more GSM DBT therapists:

… I found that a lot of the [therapists] are like cis-gendered or heterosexual. So maybe if there was some … queer or … transgender or non-binary [therapists] in DBT… [I’d] be like: well if they can do the job, I can do a job …

Over-arching Theme 3: Space for Sexual and Gender Identity in DBT

The final over-arching theme, ‘Space for Sexual and Gender Identity in DBT’, includes young peoples’ experiences of how space and safety was created for GSM young people in DBT, alongside their recommendations for how this could be improved.

Theme 3A: Negotiating focus and targeting in DBT

Young people had varied experiences of navigating whether and how to bring sexual- and gender-identity-associated targets to DBT while operating in the context of a hierarchy of treatment targets, to what degree standard DBT skills applied to minority-related needs, and whether therapists were able to respond to these needs effectively.

Participants experienced the presence of higher-order priority targets in DBT, such as life-threatening and therapy-interfering behaviours, as reducing the space available for GSM-related issues. Some noted that this was appropriate given that DBT was not specifically for GSM-related concerns. Others reflected that the hierarchy of treatment targets made space for GSM-associated difficulties seem unavailable, even if the young person wanted it and felt that they were key contributors to distress. Participants suggested that supporting young GSM people to understand how they can get to sexual- and gender-identity-related difficulties may enhance motivation to decrease risk behaviours, to progress onto lower-order targets. Aoife said:

… because of that [treatment] hierarchy, … I wasn’t really able to … talk about [sexual and gender identity] because other issues were always taking the forefront … I think even when [risk behaviours] weren’t so bad, if they hadn’t been prioritized so much, I would have been able to talk about [sexual and gender identity]… [I recommend therapists’ ask] a question of if you want to think of [what you’d like to cover in] the next three weeks … that you maybe wouldn’t have … an opportunity to speak about, we can make time for that …

Most young people reported feeling that there was not enough focus on identity generally, and sexual and gender identity specifically, in DBT. They reported wanting more focus in this area, given the perceived importance for GSM young people. Phoenix said: ‘just like more on the identity disturbance stuff, like trying to investigate whether … I am non-binary or not…’. Some also reported that the lack of focus in DBT on sexual and gender identity had resulted in them experiencing continued difficulties in this area. Sage said: ‘Because I haven’t really focused on [sexual and gender identity]… I still got all those issues…’. Participants thus suggested that DBT therapists would benefit from training in working with sexual- and gender-minority identities to improve their ability to support this group; Remy said: ‘[I recommend] educating [therapists] about … different gender identities and the different sexualities … I think that would definitely be helpful’.

Some participants described how even with less focus on sexual- and gender-identity-associated needs in DBT than desired, that the skills can sometimes be applied indirectly and are applicable regardless of identity. For example, Sage said: ‘… I don’t think the skills really discriminate … the skills are skills … Just because I identified different ways doesn’t mean I can’t use the same skill as someone else who identifies differently …’. Some also identified that by working on managing co-occurring difficulties, such as fear of abandonment and self-harm, some problems associated with sexual and gender identity reduced indirectly, although core problems may remain unaddressed. Aoife said:

… I think my … fear of abandonment and using self-harm to cope with [was] helped because that’s … what [DBT] … aims to target. But I don’t think that it necessarily like helped my … experiences of feeling confused with [my sexual and gender identity]… I just didn’t really have those chats and so it didn’t really address my experiences of it.

Participants felt that the lack of GSM-specific skills and attention paid to applying DBT skills to these issues may be barriers to using DBT to address their minority-related needs. For example, Avery said: ‘I think people would think to apply [some skills to sexual and gender identity], but I think just because it’s … not mentioned at all … people might not even think to’. To improve space for sexual and gender identity in DBT, participants recommended explicitly applying skills and principles to GSM-related issues and using GSM examples in teaching content. Jordan said: ‘I feel like the aspect of sexuality could be bought into [skills teaching] … more … So, it’s not: if you’re out with your boyfriend … It’s: out with my girlfriend’. Participants also recommended providing additional skills/content and resources targeting specific areas related to GSM experiences, including more on managing bullying related to GSM, navigating romantic and non-romantic relationships as a GSM person, coming out to others, the relationship between cis-heterosexism and other difficulties, and more focused on identity confusion and development. For example, Asriel said: ‘I think … more specific skills [for sexual- and gender-identity-related difficulties] … Maybe for like being bullied in school or … trouble with family … [and] problems of like confidence in themselves …’.

Participants reported feeling that being asked by therapists about and inviting a focus on sexual and gender identity, identity confusion, pronouns, and preferred names was helpful for them knowing that there was space for these topics, even if they did not take this up. Kit said: ‘I think [my therapist bringing up sexual and gender identity] was more helpful because I don’t think I was going to bring it up and … if I didn’t, I would have like worried about it, but not brought it up’. Participants also reported that asking about and inviting this focus was pertinent from the first point of contact and in all modes of DBT, where this seemed appropriate. Ellis said: ‘During … all parts [of DBT], but especially in individual [sessions] … therapists just … saying like: we can talk about [sexual and gender identity]…’. Doing so in one mode of treatment was thought to make it easier to bring sexual and gender identity to other modes. Participants also suggested that questions around sexual and gender identity should be done so in a manner that communicates that it is optional. For example, Phoenix said: ‘Yes [therapists should ask about sexual and gender identity], but … there might be someone who isn’t ready to talk about it … [so it is important] to have like option to talk but not being forced to’. Participants also described how putting questions about sexual and gender identity on sociodemographic questionnaires at assessment may decrease the burden of coming out to the DBT team; Sage said: ‘… [because sexual and gender identity] was on the forms … it doesn’t feel as though I have to like come out’. Furthermore, participants recommended that opportunities are taken to check back in about sexual and gender identity at regular intervals, with an acknowledgement and acceptance from therapists that identity may change over time. It was experienced by some as dismissing when their therapist did not take up opportunities to bring in sexual and gender identity, especially when this was brought up by the young person. For example, Aoife said:

… when I would quite passively bring something up [related to sexual and gender identity] and … it wouldn’t be … elaborated on by my individual therapist, I’d experience that as unhelpful and because I wasn’t getting to talk about things that I … felt like I needed to … it’s just that kind of experience of dismissal …

Theme 3B: Creating safety in DBT

The ‘Creating safety in DBT’ theme contains experiences and suggestions pertaining to how DBT was made to feel safe for GSM young people and where this could be improved. Most participants described DBT as a safe space for bringing issues related to sexual and gender identity. They expressed feeling accepted, supported, not judged, and generally like the therapists and peers were open and less prone to making assumptions than previous experiences of services, which helped the space feel safe. They particularly felt that DBT had been a safer space compared to with previous therapies and services. See exemplar by Jordan:

… I think … ’cause [DBT is] … a non-judgemental zone. Like you don’t get looked at … with pity or disgust or judgment. It’s a very open … space and I feel that is beneficial for so many people that don’t have that safe space with the people their close to. I feel it … helps them be more open and free … Everyone is very welcomed as … their selves.

On the other hand, some participants reported worries about therapists’ and other young peoples’ (e.g. in skills group) judgements and possible rejection. They cited this as a barrier to feeling safe in DBT, as they were unsure of the prejudicial beliefs held by others. Remy said: ‘… I guess the first [worry]… [is] if you bring [your sexual and gender identity] up [to the DBT team] yourself, you’re … in that … position where you’re … almost … judged’.

Participants also described how safety can be increased by making clear the parameters of confidentiality regarding their sexual and gender identity. Some feared that they may be accidently ‘outed’ to their parents/carers by their therapist or dissemination of their sexual and gender identity on reports. They suggested therapists ask who young people are comfortable with knowing about their sexual and gender identity, and clarifying where related data will be stored or disseminated. Some also reported fears that they may be overheard when discussing sexual and gender identity if accessing DBT from home or other locations. Safety could be improved here by checking that they are somewhere they cannot be overheard, to help them weigh up if it is safe to disclose to their clinician. For example, Aoife said:

… [I was] less able to … talk about [sexual and gender identity] … because of the … confidentiality thing. Would [my parents/carers] hear? … I would feel more able to talk about it if I was … reassured … that there wouldn’t be a[n] … accidental outing … situation … I guess also … making sure that … [my sexual and gender identity] won’t end up on the report home or … in A&E …

Despite worries about others’ prejudice, some reported that participating in skills group with other young people, who they experienced as accepting and open, helped create a safe space for them to bring topics related to sexual and gender identity, and access shared experience and peer support. Some participants, mostly those who reported being out to accepting parents/carers, suggested that they felt the parent/carer interventions within the programme (e.g. parent/carer skills group) made the space feel safer for them to bring sexual and gender identity to DBT. This was because they felt their parents/carers would have increased skills in how to validate and support them; see quote by Koda:

I think it was good that my parents were involved in DBT … I think it probably would have made it … easier to bring stuff relating to sexuality and gender identity with them, had it come up, because … they would have been more educated about validation and stuff, but it didn’t come up … and my parents are already very accepting …

There were suggestions that if there was more content regarding the link between sexual and gender identity and distress in the parent/carer intervention, this potentially would have made them feel safer to bring issues related to sexual and gender identity to their parents/carers and to DBT.

Finally, many described the importance of therapists getting gender pronouns right to help cultivate a safe space for issues related to sexual and gender identity in DBT. For instances where incorrect pronouns were used, particularly highlighted in previous mental health service, this caused distress and made them feel that the space was less safe. For example, Sage said:

… DBT was … a safe space because I could come here and right away …, we will use the right pronouns … Whereas it was more difficult for other people … and they weren’t as good at … getting the pronouns right …, and so that was a bit stressful and that was negatively impacting … my mental health as well.

The participants also encouraged the use of safety signals such as the presentation of pronouns, including those inside and outside of the gender binary, in clinicians’ email signatures; Amari said: ‘Throughout DBT there’s just been … subtle hints that … this is a safe space … [like] at the end of my individual therapist’s email, that had her pronouns there’.

Discussion

This study sought to understand the experiences of GSM adolescents in a DBT programme regarding how the intervention met their GSM-associated needs and which minority-related difficulties were important to target in treatment. The experiences of the GSM young people are articulated via three over-arching themes: Identity, the Impact of Others, and Space for Sexual and Gender Identity in DBT.

GSM-associated targets and intervention tasks

Targets related to identity confusion and self-acceptance

Participants highlighted a number of identity-related dilemmas, such as identity confusion and acceptance, which had an impact on wellbeing and were considered as important for targeting in DBT, congruent with identity development and minority stress research (Camp et al., Reference Camp, Vitoratou and Rimes2020; Camp et al., Reference Camp, Vitoratou and Rimes2022; Cass, Reference Cass1979; Hendricks and Testa, Reference Hendricks and Testa2012; Meyer, Reference Meyer2003). It may also be particularly important to focus on identity in DBT for adolescents given the importance of this developmental stage for identity evolution and acceptance (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Dawes and Plocek2021; Katz-Wise et al., Reference Katz-Wise, Budge, Fugate, Flanagan, Touloumtzis, Rood, Perez-Brumer and Leibowitz2017; Meyer, Reference Meyer2003; Savin-Williams and Ream, Reference Savin-Williams and Ream2007). There may also be unique challenges to reducing identity confusion for those who experience plurisexual attractions. For example, some participants identifying as bisexual or pansexual experienced increased sexual-identity-related confusion depending on whether they were attracted to someone of the same or different gender, similar to dilemmas highlighted in past research (Dyar et al., Reference Dyar, Feinstein, Schick and Davila2017).

Many experienced gender diversity as harder to accept and felt less acceptable to others, compared with sexuality diversity, congruent with existing research (e.g. Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Gower, Nic Rider, McMorris and Coleman2019). This may particularly highlight the impactful transactions between societal expectations and the internalisation of these expectations, on sexual- and gender-identity expression, which contributed to identity confusion and non-acceptance. Therefore, interventions targeting identity confusion would likely benefit from considering and integrating the wider socio-political context.

Participants highlighted possible tasks and corresponding DBT skills/principles for reducing difficulties with identity confusion and self-acceptance, which are presented in Table 4 alongside suggestions informed by the literature (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2021; Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Whicker and LeMaire2019). DBT interventions for GSM identity confusion and self-acceptance may need to increase self-awareness, -exploration, -confidence and -expression, as well as decrease identity-related shame and distress, and the potential impact of traumatic invalidation. If past trauma is associated with identity confusion and distress, it may be that corrective learning procedures will be helpful to include in DBT (e.g. DBT-prolonged exposure therapy; Harned, Reference Harned2022). This may be particularly relevant given the high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in GSM groups (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Berke, Scholl, Ruben and Shipherd2020). DBT-prolonged exposure therapy has the scope to include target PTSD symptoms after ‘Criterion A’ trauma events as well as traumatic invalidation, and provides specific treatment recommendations for working with GSM individuals (Harned, Reference Harned2022). Generally, therapists will likely need to employ higher levels of validation when supporting GSM young people with identity-related tasks, to counteract the impact of the cis-heterosexist invalidating environment. An acceptance of the complex nature of identity development, its fluidity over time, and the client as they are in the moment will also likely be needed. Therapists should educate themselves on relevant experiences for GSM youth, to avoid pathologisation or invalidation, while at the same time holding themselves in the frame of fallibility.

Table 4. Identity confusion and self-acceptance treatment strategies

Tasks and suggestions informed by participant feedback and previous research (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2021; Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Whicker and LeMaire2019). Tasks and skills/principles are not in any particular order. Skillset indicators: CM, Core Mindfulness; WMP, Walking the Middle Path; ER, Emotion Regulation; DT, Distress Tolerance.; IE, Interpersonal Effectiveness; O, treatment strategies/principles outside of the DBT behavioural skills principle; DBT-PE, DBT Prolonged Exposure Therapy (Harned, Reference Harned2022).

Targets related to the Impact of Others

Participants reported various experiences of cis-heterosexism towards their GSM identity globally and towards specific GSM identities, such as anti-bisexual stigma and transphobia. These experiences negatively impacted wellbeing, similar to findings in previous research (Brewster and Moradi, Reference Brewster and Moradi2010; Cardona et al., Reference Cardona, Madigan and Sauer-Zavala2022; Dyar et al., Reference Dyar, Feinstein and Davila2019; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Gower, Nic Rider, McMorris and Coleman2019; Hendricks and Testa, Reference Hendricks and Testa2012; Meyer, Reference Meyer2003). Participants highlighted that GSM adolescents in DBT likely need support to cope with cis-heterosexism, given the negative impact on their wellbeing. At the same time, this is to be balanced with empowering minoritised people to advocate for their needs and a more accepting social environment (Camp, Reference Camp, Semlyen and Rohleder2023; Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). This is to prevent an over-emphasis on the minoritised individual being responsible for managing oppression by others. Where the environment is too powerful, however, as should always be assumed in the context of cis-heterosexism, it is likely necessary for others to intervene. This is similar to recommendations for applying DBT for GSM people (Camp, Reference Camp, Semlyen and Rohleder2023; Tilley et al., Reference Tilley, Molina, Luo, Natarajan, Casolaro, Gonzalez and Mahaffey2022) and in anti-racist DBT competencies (Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). Therefore, DBT therapists, alongside parents and carers, will likely need to consider how to consult to the young people in how to effectively manage cis-heterosexism by others, as well as to intervene in the environment as needed to protect them from harm.

Furthermore, young people highlighted the importance of connectedness to similar and accepting others for their wellbeing. This finding is congruent with research highlighting that increased connection and participation with the GSM community and allies improves wellbeing and resilience for GSM individuals (e.g. Ceatha et al., Reference Ceatha, Mayock, Campbell, Noone and Browne2019). Connection to similar others was thought to be facilitated in DBT via the skills group, similar to adapted DBT for sexuality-minoritised adults (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2021). Therefore, promoting connectedness for young GSM people in DBT is likely important, in relation to opportunities available for this in the skills group and in agreeing treatment targets, especially with those for whom social disconnection may be a significant problem.

Relevant intervention tasks and applicable DBT skills/principles for reducing the impact of cis-heterosexism and increasing connection to others are suggested in Table 5, informed by the findings of this study and corresponding literature (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2021; Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Whicker and LeMaire2019). For DBT therapists supporting GSM adolescent in this area of work, it will be important to consider safety when operating within cis-heterosexist environments (Tilley et al., Reference Tilley, Molina, Luo, Natarajan, Casolaro, Gonzalez and Mahaffey2022). This may be a particular consideration when using assertiveness skills to challenge anti-GSM behaviours or when completing exposure tasks within cis-heterosexist contexts (Harned, Reference Harned2022). Problem solving by the therapist and client may be needed to navigate safety concerns, and the therapist may need to make an intervention in the environment to improve safety if needed.

Table 5. Cis-heterosexism and community connectedness treatment strategies

Tasks and suggestions informed by participant feedback and previous research (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2021; Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Whicker and LeMaire2019). Tasks and skills/principles are not in any particular order. Skillset indicators: CM, Core Mindfulness; WMP, Walking the Middle Path; ER, Emotion Regulation; DT, Distress Tolerance; IE, Interpersonal Effectiveness.

The application of DBT for GSM adolescents

Participants in this study highlighted how the use of the DBT model and the BPD diagnosis may invalidate GSM young people via the potential for pathologising normative identity confusion. Rathus and Miller (Reference Rathus and Miller2000) identify the pathologisation of normative behaviours versus normalising pathological behaviours as a key dialectical dilemma for those working with adolescents in DBT. For this reason, some do not consider it acceptable to use the BPD label for people below 18 years of age, while others feel early diagnosis is important for early intervention (Chanen et al., Reference Chanen, Sharp and Hoffman2017; Swales, Reference Swales2022). Additionally, clinician-bias when diagnosing BPD in GSM individuals may mean GSM people are more likely to be erroneously diagnosed based on normative behaviours within their subculture (Rodriguez-Seijas et al., Reference Rodriguez-Seijas, Morgan and Zimmerman2021). Therefore, to minimise additional negative impacts when conducting assessments with young GSM people, careful consideration and consultation to the client may be needed to explore the applicability and pros and cons of diagnosis (particularly BPD); and also, to offer some choice around whether this framework is used to describe their difficulties.

DBT currently has a number of principles and skills which can be applied to working with identity- and cis-heterosexism-related difficulties, such as those suggested by the participants in this study and previous research (e.g. Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Whicker and LeMaire2019; Tilley et al., Reference Tilley, Molina, Luo, Natarajan, Casolaro, Gonzalez and Mahaffey2022; see Tables 4 and 5). Many young people felt that there were applicable DBT skills for GSM-associated difficulties. However, a lack of specific application and skills for the sexual- and gender-identity-related targets may have reduced space and applicability of DBT principles to these needs. Therefore, DBT therapists should consider with their clients which aspects of diversity are important to integrate into their therapy, and make efforts to apply the appropriate DBT principles (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2021; Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Whicker and LeMaire2019; Tilley et al., Reference Tilley, Molina, Luo, Natarajan, Casolaro, Gonzalez and Mahaffey2022). These findings also highlight a potential need for some tailored skills and psychoeducation for GSM-associated difficulties, where they cannot be easily met by existing DBT principles. This has been highlighted as a gap in traditional DBT by previous research, which has offered some potential solutions for different GSM populations (see Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2021; Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Mirabito, Kirkman and Shaw2021; Tilley et al. Reference Tilley, Molina, Luo, Natarajan, Casolaro, Gonzalez and Mahaffey2022 for details).

While not explicitly mentioned in Linehan’s (Reference Linehan1993) original biosocial theory, GSM experiences such as those highlighted in the present study, could be conceptualised as part of invalidating environments that contribute to the development of emotion dysregulation and related problems in GSM adolescents. Later iterations of the biosocial model have elaborated on the role of the wider socio-political invalidating environment for minoritised groups (e.g. Camp, Reference Camp, Semlyen and Rohleder2023; Grove and Crowell, Reference Grove, Crowell and Swales2019). Early versions of considering how to apply the DBT model to GSM adult populations also exist (e.g. Camp, Reference Camp, Semlyen and Rohleder2023; Pantalone et al., Reference Pantalone, Sloan, Carmel, Pachankis and Safren2019), although no known attempt has been made to do this for GSM adolescents. Further updates to the biosocial theory, specifically for GSM adolescents, may thus be warranted alongside the integration of other areas of minoritisation (e.g. Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022).

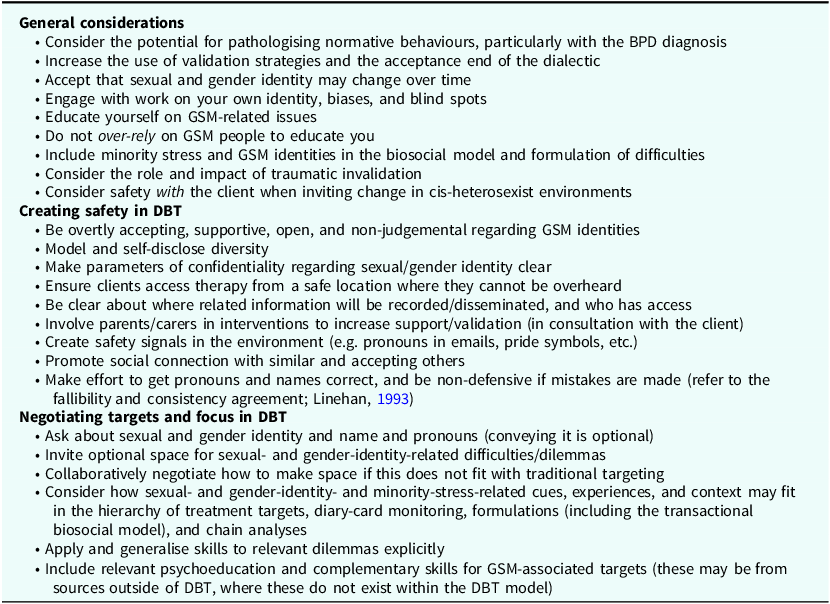

Participants highlighted a number of ways in which a focus on sexual and gender identity in DBT could be better negotiated by DBT therapists (see Table 6 for a summary of suggestions informed by participant feedback). Nonetheless, it may be difficult for GSM-related difficulties to be incorporated into the treatment. This is because there is a high threshold for integrating difficulties into the ‘quality-of-life’ targets, such that these often need to be associated with clinically severe mental ill-health or severely destabilising behaviours (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993). This may represent a dilemma for therapists attempting to support GSM adolescents in DBT where they perceive GSM-associated dilemmas to be important to target and at the same time these difficulties may not meet the thresholds for targeting in ‘stage 1’ DBT (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993). Alternatively, therapists could consider other strategies for covering this content in DBT if the young person is endorsing them as significant. Options may include targeting these difficulties if they exist as key ‘links’ on the chain of events resulting in higher-order (i.e. life-threatening and therapy-interfering) targets; collaboratively supporting the identification of minority stressors in chain analyses; tracking relevant experiences on the diary card; validating relevant experience and linking to the biosocial model; the use of secondary targeting to navigate GSM-associated dilemmas; or agreements to work towards these targets once traditional ‘stage 1’ treatment targets are met, should there be the scope. It may also be relevant for DBT to create clearer pathways for working on GSM-associated targets that do not meet threshold for ‘stage 1’ targeting. This could be in a similar fashion to the integration of PTSD interventions, traditionally a ‘stage 2’ intervention, into ‘stage 1’ DBT (Harned, Reference Harned2022). Flexibility in targeting could also be implemented if it would increase the acceptability of DBT to this population. Therapist awareness of GSM-associated dilemmas and difficulties in their societal context are likely needed to improve their abilities to validate and observe when a relevant issue may arise in treatment, which may benefit from using frameworks which support them to consider power and privilege in their work (e.g. Burnham, Reference Burnham and Krause2012; Hays, Reference Hays2001). This is similar to recommendations for culturally-sensitive care for GSM groups (British Psychological Society, 2019) and congruent with the suggestions by participants in this study.

Table 6. Recommendations for DBT therapists supporting GSM young people

Suggestions informed by participant feedback and previous research (Camp, Reference Camp, Semlyen and Rohleder2023; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Norona, Yadavia and Borsari2021; Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Whicker and LeMaire2019; Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Berke and Shipherd2017; Tilley et al., Reference Tilley, Molina, Luo, Natarajan, Casolaro, Gonzalez and Mahaffey2022). Recommendations are not in any particular order.

Many participants reported feeling that DBT was safe for them as GSM youth and that this was an improvement compared with previous psychological interventions. Young people additionally reported that creating safety in DBT remained important and can be achieved by therapists in various ways (see Table 6). Studies suggest that GSM young people face significant barriers to seeking support in health services (Bindman et al., Reference Bindman, Ngo, Zamudio-Haas and Sevelius2022; Dunbar et al., Reference Dunbar, Sontag-Padilla, Ramchand, Seelam and Stein2017; McDermott, Reference McDermott2016; Williams and Chapman, Reference Williams and Chapman2011). Research also suggests that GSM youth have an understandable vigilance and sensitivity towards stigma and rejection, which may add further barriers to disclosing identity to therapists (Baams et al., Reference Baams, Kiekens and Fish2020; Kiekens et al., Reference Kiekens, Baams, Feinstein and Veenstra2023), similar to the findings of this study. Therefore, improving safety and acceptability of DBT for GSM adolescents is important.

It may be particularly pertinent to ensure safety symbols are present in documents/materials and clinic environments to communicate that DBT is safe, as suggested in previous research and guidelines (e.g. British Psychological Society, 2019; Diamond and Alley, Reference Diamond and Alley2022; Skerven et al., Reference Skerven, Whicker and LeMaire2019). These could include: pronouns in therapists’ email signatures, asking about sexual and gender identity on sociodemographic information, groups guidelines that encourage respect and connection, and visible pride symbols (for further examples, see Diamond and Alley, Reference Diamond and Alley2022). While it is important to ensure safety signally, therapists are inevitably going to make mistakes in these areas at times. Where this occurs, it would be useful for therapists to refer to the fallibility and consistency agreements (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993) to maintain self-compassion and non-defensiveness, as well as to share this with clients when making appropriate repairs and validating related distress. Creating safety, in the experiences of these GSM adolescents also seems primarily to be achieved in the relational context between the young person, the team of therapists, and others in their personal system. Social signals of safety are important for reducing the impact of stigma (Diamond and Alley, Reference Diamond and Alley2022). Additionally, concerns regarding confidentiality of sexual and gender identity have been highlighted elsewhere as a barrier to accessing services (Dunbar et al., Reference Dunbar, Sontag-Padilla, Ramchand, Seelam and Stein2017; Williams and Chapman, Reference Williams and Chapman2011), and thus may be an important area to clarify in DBT.

Strengths and limitations

This study represents the experiences of 14 GSM young people. The analysis was supported by two further GSM youth, alongside checking by an independent researcher, which constitutes strengths of the methodology. However, the analysis was largely completed by the primary author. Therefore, findings are to be understood largely as their contextual interpretation of the data, with input from the remaining authors, independent researchers, and the two GSM youth. Findings are also from a specialist NHS DBT context with deviations from the original DBT for adolescents’ model (for details, see Camp et al., Reference Camp, Hunt and Smith2023), which may impact the generalisability to other settings and populations. Young people meeting inclusion criteria for DBT usually have significant problems with emotions, identity and relationships. Therefore, GSM young people with less severe difficulties may have different views on what contributes to their distress and what is needed in therapy. It is also of note that there was low representation of certain intersectionally-diverse groups in this sample, including people from ethnicity- and race-related minoritised groups, age, and those assigned male at birth or with a male gender identity. Only one participant was below 16 years of age, which means that findings may not be generalised to younger GSM groups in DBT.

Research into the experiences of GSM young people in DBT and related interventions is in its infancy and represents an important area of study given the poor experiences, higher mental health difficulties, and over-representation in DBT settings (Camp et al., Reference Camp, Hunt and Smith2023; Camp et al., Reference Camp, Durante, Cooper, Smith and Rimesin press; Harned et al., Reference Harned, Coyle and Garcia2022). Future research could focus on the implementation and evaluation of these recommendations, the potential development of specific and/or adapted DBT skills/principles for GSM-associated dilemmas, and to explore and increase anti-oppressive and culturally sensitive competencies in clinicians working with GSM young people. This could be combined with effectiveness and efficacy studies to compliment the early work in this area (e.g. Poon et al., Reference Poon, Galione, Grocott, Horowitz, Kudinova and Kim2022).

Conclusion

GSM young people felt issues related to identity confusion and acceptance, alongside how to cope with and change cis-heterosexist behaviours and reactions by others, contributed to their distress and thus were important to target in DBT. Participants also reported that it was important for DBT therapists to provide support and promote a sense of safety in order to help bring sexual- and gender-identity-related issues into therapy. These represent important recommendations for DBT therapists when supporting GSM adolescents.

Key practice points

-

(1) Therapists to be aware of support needs for GSM young people in DBT including: identity confusion and non-acceptance, hostility from others, and the challenges of bringing sexual- and gender-identity-related issues to therapy, as well as the need to connect with similar others and to build self-acceptance.

-

(2) Therapists to balance supporting GSM young people to cope with cis-heterosexism, while also remembering that in some situations it may be appropriate for the therapist (and/or others in their system) to intervene (e.g. with the young person’s school), in consultation with the client, to address cis-heterosexist events as the oppressive environment is likely too powerful for the minoritised individual to do this alone.

-