Although studies of Mozart's embellishments have been associated primarily with the early-music movement in the second half of the twentieth century, questions concerning the relationship of text, performance and improvisation in the composer's oeuvre have plagued performers and scholars for more than two centuries. As early as 1834, the violinist and pedagogue Pierre Baillot broached the topic of Mozartean embellishment, taking as his point of departure the varied repetitions in the slow movement of the ‘Dissonance’ Quartet, k465:

In the next example, far from wanting to embellish the melody, the violinist must play only the notes that are written, with all the charm that they have. . . . The ornamentation provided by the composer will then stand out in all its elegance and expression.Footnote 1

Nearly one hundred and eighty years later, Baillot's sentiments were echoed by the fortepianist John Irving, who found the slow movement of Mozart's Piano Sonata k309 to be ‘something of a paradox’:

Whenever I play it (the opening 16 bars, for instance), I fail to engage with its notated text satisfyingly in the way I would ideally wish – namely, to embellish it. The problem is that Mozart seems to have written in all the embellishments already, leaving no room for the player to intervene.Footnote 2

Baillot and Irving take opposing views of the relationship between performer and musical notation: one submits proudly to the dictates of the composer's text, whereas the other does so reluctantly. Yet both share the view that Mozart's written works are not simply carefully developed compositions, but records of his preferences for performance – in particular, for the style of embellishment that should be applied in his slow movements. His notation, with its highly developed expressive specificity, seems to enshrine crucial features of the improviser's art.

Over the past five decades, this view has become orthodoxy among specialists in eighteenth-century performance practice. It is generally accepted that the many notated embellishments in Mozart's works are prescriptions for performance not only of the movements in which they are embedded, but of the rest of his output as well. To Katalin Komlós, Mozart's piano variations are a ‘treasure house’ of decorative figures that can be reused in more sparsely notated passages.Footnote 3 Robert Levin, known for weaving his own embellishments from the melodic fabric of Mozart's written works, suggests a more systematic approach based on the same premise. He encourages would-be improvisers to study the rondos and slow movements for which the composer provided decorations, aligning the various thematic repetitions and thus absorbing Mozart's own protocols for melodic variation.Footnote 4 This mindset has proven so successful in shaping our understanding of Mozartean performance practice that in 1989 the fortepianist Malcolm Bilson, then partway through recording his Mozart concerto cycle, stated flatly that ‘we already know pretty much all there is to be found out about ornamentation in the eighteenth century. Unless somebody finds a compact disk of Mozart playing the fortepiano, I don't think we're going to find anything else.’Footnote 5

If Bilson's claim seems implausible, it has since been validated in practice if not in theory. Although new sources for the study of Mozart's embellishments have occasionally surfaced, most famously a manuscript leaf containing decorations for the Adagio of the Piano Sonata in C minor, k457, the information such sources convey does not differ radically from what was previously known based upon other sonata slow movements, including those of k284, k309 and k332.Footnote 6 Likewise, although some pianists are more daring than Bilson in their textual interventions, those who attempt to emulate Mozart's embellishments do so using largely the same vocabulary that Bilson pioneered in his cycle. Perhaps most importantly, over the past three decades no conceptual revolutions have destabilized prevailing views of the field. Current notions of the function of embellishment in the composer's musical language, as well as the kinds of evidence admitted in reconstructing his improvisations and the criteria according to which such evidence is used, are generally understood today in terms no different from those implicit in Baillot's treatise.

Even so, isolated murmurs of concern are occasionally heard. Eva Badura-Skoda, for instance, has noted that the sheer variety of Mozart's embellishment figures complicates the task of recycling gestures between works,Footnote 7 while Simon Keefe (echoing an earlier sceptical statement by David Grayson) has suggested that the too-careful emulation of Mozart's practices might limit the creative freedom of modern-day performers.Footnote 8 These worries are mainly practical, yet the prospect of deriving knowledge of Mozartean embellishment based on the composer's written texts is vulnerable to criticism on theoretical grounds as well. Those who advocate selecting and reusing embellishments seem to hold two conceptions of musical notation that are mutually incompatible. On the one hand, we are told that the composer's texts are incomplete, and thus in need of intervention by performers. According to this view, notation does not provide a trustworthy indication of either Mozart's intentions or his actual practices. On the other hand, those same notated texts are treated as the basis for further elaborative decoration. Levin and others have attempted to resolve this problem by noting that the use to which Mozart expected his texts to be put would in large part dictate their specificity – in other words, the reliable texts, written for pedagogical purposes or publication, can be used to enhance the notational density of the often-sketchy texts Mozart prepared for his own use.Footnote 9 Even allowing for this nuance, however, theoretical obstacles remain. For instance, we may wonder whether embellishments gleaned from slow movements written in the mid-1780s can be applied straightforwardly to works in quicker tempos, or to those written at different stages of the composer's career. There is also the question of how exactly the gestures should be reused: whether their inclusion in Mozart's texts, and by extension in his performances, was random, or whether an overarching logic governed his musical decisions when creating embellishments. Although this question seems to carry us some distance away from the embellishment gestures themselves, in reality the issue of higher-order musical principles is inseparable from that of local detail. As Leonard Meyer argues in Style and Music,

one can list and count traits – say, the frequency of sforzandi in Beethoven's music or the number of deceptive cadences in Wagner's operas . . . but if nothing is known about their functions (structural, processive, expressive, and so on), it will be impossible to explain why they are there, how their presence is related to other features observed, or why their frequency changes over time. Such traits may even serve as reasonably reliable ‘identifiers’ of Beethoven's or Wagner's style, yet contribute nothing to our understanding of how the style functions.Footnote 10

The gestures that make up Mozart's vocabulary of embellishments may be subjected to rigorous and thorough study, yet these studies do not in themselves reveal the protocols and preferences that guided Mozart's hands and mind when he worked.

In this article I reopen the case of Mozartean embellishment. My purpose is to provide not only an up-to-date account of the problems that beset the study of Mozart's embellishing figurae, but also an overview of his melodic style as it operates on the broader levels to which Meyer refers: the structural, the processive and, most of all, the expressive. I begin with a brief critical assessment of the composer's model embellishments, which have formed the basis for virtually every study to date, yet which may reveal less about his practices than is generally believed. I then turn to a different body of evidence, exploring the structural implications of repeated, decorated themes throughout Mozart's oeuvre. I end by considering the rhetorical and aesthetic dimensions of embellishments: their relation to the expressive scope of a passage, their capacity to suggest something of the composerly persona embedded in the work and their broader import for our understanding of Mozart's style. If, as a subject of modern-day investigation, Mozartean embellishment has most often been considered from the perspective of historical performance, I hope to show that it is a topic of musical and aesthetic interest in its own right.

Sources for Mozartean Embellishment: Models, Compositions and Drafts

The starting-point for virtually every investigation of Mozartean embellishment is the set of models Mozart produced between approximately 1773 and 1785. These include decorated variants of three contemporary arias (two of his own and one by J. C. Bach); insertions for the Piano Concerto k451 (composed for his sister) and the Piano Sonata k457 (for his pupil Therese von Trattner), both of which survive in manuscript; published variants for the Piano Sonatas k284 and k332; and, possibly, handwritten embellishments for an as-yet-unidentified Adagio in F major. With the possible exception of this last specimen (the origins of which remain mysterious) and the published variants (whose pedagogical status remains unclear), these models were intended to aid performers who lacked the skills necessary to improvise decorations of their own.Footnote 11

Such sources have been accorded significant weight in the literature, yet their textual histories, particularly those of the keyboard models, suggests that they offer a less reliable picture of Mozart's practices than is often claimed. One problem involves the provenance and date of the relevant sources. Although the keyboard works that formed the basis for these models were composed over nearly a decade, between 1775 and 1784, all of their embellished variants originated in 1784.Footnote 12 They therefore offer a snapshot of Mozart's style at a single moment in his creative development, but say little about long-term trends in his practices. Mozart's earlier embellishments, for voice, would seem to balance the documentary record, but these introduce complications of their own, particularly given the many contemporary conventions governing word-painting, the depiction of operatic drama and the setting of Italian prosody. A further problem is that these models decorate only slow movements, and are therefore of uncertain relevance to works in other tempos. Finally, the instrumental models generally apply only to isolated portions of movements – a mere six bars in the case of k451. The decorations for k457 sidestep this problem somewhat, since they demonstrate progressive elaborations that become more complex with each recurrence of the rondo theme. Yet even these amount to little more than twenty bars of material, applied to only one of the movement's many themes. If they shed some light on the types of free variation that might be conjured within a recurring melody, they say little about Mozart's expectations for other passages in the movement, or indeed for works in other tempos, forms or genres.

The musical content of these models, too, is enigmatic. On the one hand, the models suggest something of the extravagance with which Mozart hoped performers would depart from his texts. In the embellishments for k451 (shown in Example 1) the departures reshape the melody, altering the intervallic span of leaps and obscuring the original material beneath added scales and arpeggios, even while preserving the Sol–Fa–Mi schema that underpins both the melody and the embellishments. On the other hand, this decorative freedom borders on randomness. It is difficult to identify any consistent relationship between the embellishments and the tune they adorn – and this in turn complicates the process of extrapolating any broader technical or aesthetic protocols from the passage. In some cases, the k451 embellishments conform to the shape and scope of the original, departing only modestly. This is true, at least, for the first two bars. Yet beginning in the following bar, Mozart's departures become more daring. What began as a leap of a sixth is embellished as an ascending octave, overshooting the notated melody before returning to dovetail with the phrase's original shape. In the next ascent, in bar 60, an arpeggio is converted into a decorated scale whose semiquavers mask the drawn-out alla-breve syncopation of the original. The embellishments then briefly track the melody again before diverging further when a simple descending third is replaced by a lyrical upward leap. Though this model has often been touted as an important piece of evidence in understanding Mozart's improvisatory practices, its significance could equally be construed as lying in the general sense of creativity and imagination its decorations convey, rather than in any specific aspect of their content or structure.Footnote 13

Example 1. Mozart's embellishments for Piano Concerto in D major k451/ii, Andante, bars 56–63 (Neue Mozart-Ausgabe [NMA] series 5, group 15, volume 4, ed. Marius Flothuis (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1975)). All examples used by permission

Other embellishments include those found in the first editions of the Piano Sonatas k284 and k332. However, it is not clear whether these constitute pedagogical models in the same respect as k451 and k457, or whether they should be considered as self-contained compositional variants. Whereas Mozart's sister Nannerl, Maria Therese von Trattner and any other pupils and colleagues who worked directly with Mozart would have had the luxury of comparing the embellished variants to the sparse notations in the original texts, and may therefore have been able to analyse the relationship between original melody and embellished version, those members of the general public who purchased editions of k284 and k332 would have enjoyed no such convenience. Not only do the editions not provide a side-by-side juxtaposition of the embellished and unembellished versions of the themes, they do not even give any explicit indication that the embellishments are to be understood ‘as’ embellishments. From the perspective of consumers, the decorated variants are themselves the only printed version of the text. It therefore seems unlikely that in composing them Mozart's aspirations would have been primarily pedagogical. By 1784 he was poised to become a prolific publisher, and the communicative acumen that informed his public concerts would certainly have extended to his printed editions as well.Footnote 14 If the embellishments in the first editions of k284 and k332 were meant in part to guide the performance styles of those who bought and played these works, they were probably also meant to show off his composerly ingenuity, and as such were most likely prepared using criteria other than performative instruction.

Other sources in which Mozart's preferences for embellishment can be glimpsed include the many slow movements and rondos in which progressive elaborations are introduced during melodic repetitions. Examples include the slow movements of the Piano Sonata k309 and the ‘Dissonance’ Quartet, k465, both mentioned at the outset of this article, as well as the slow movement of the Violin Sonata k481, the Rondo k494 (later repurposed and expanded as the finale of the Piano Sonata k533) and the Rondo k511. It is unclear whether Mozart considered these embellishments as fulfilling the same pedagogical function as his more explicit models; but whatever his intentions, such works do hold pedagogical import exceeding that of the variants discussed above. By presenting the unembellished version of the theme at the outset and then moving through a series of alternatives, Mozart makes it easy to compare and analyse different versions of each theme.

The sources I have described so far constitute the entire body of evidence used in most studies of Mozartean embellishment. However, the composer's oeuvre contains countless other works whose repeated themes undergo progressive elaboration – not within the formal plan of a rondo, but simply during the routine unfolding of musical argument. Although these ‘extrageneric’ embellishments are not marked off from the surrounding musical material, they follow the same contextual logic as the more explicit models, by introducing melodic variation into already established themes.Footnote 15 This, it is worth noting, is precisely the problem facing performers who wish to embellish Mozart – namely, how to use melodic additions to alter a phrase that has been codified and notated in advance. Such instances of melodic variation occur in all possible contexts throughout Mozart's oeuvre, most often in the solo keyboard works, but also in genres where no simulation of performed embellishment is taking place (for instance, in a symphonic phrase embellished by an entire violin section). These decorations suggest some of the criteria Mozart would have used in the course of both notating and improvising his embellishments.

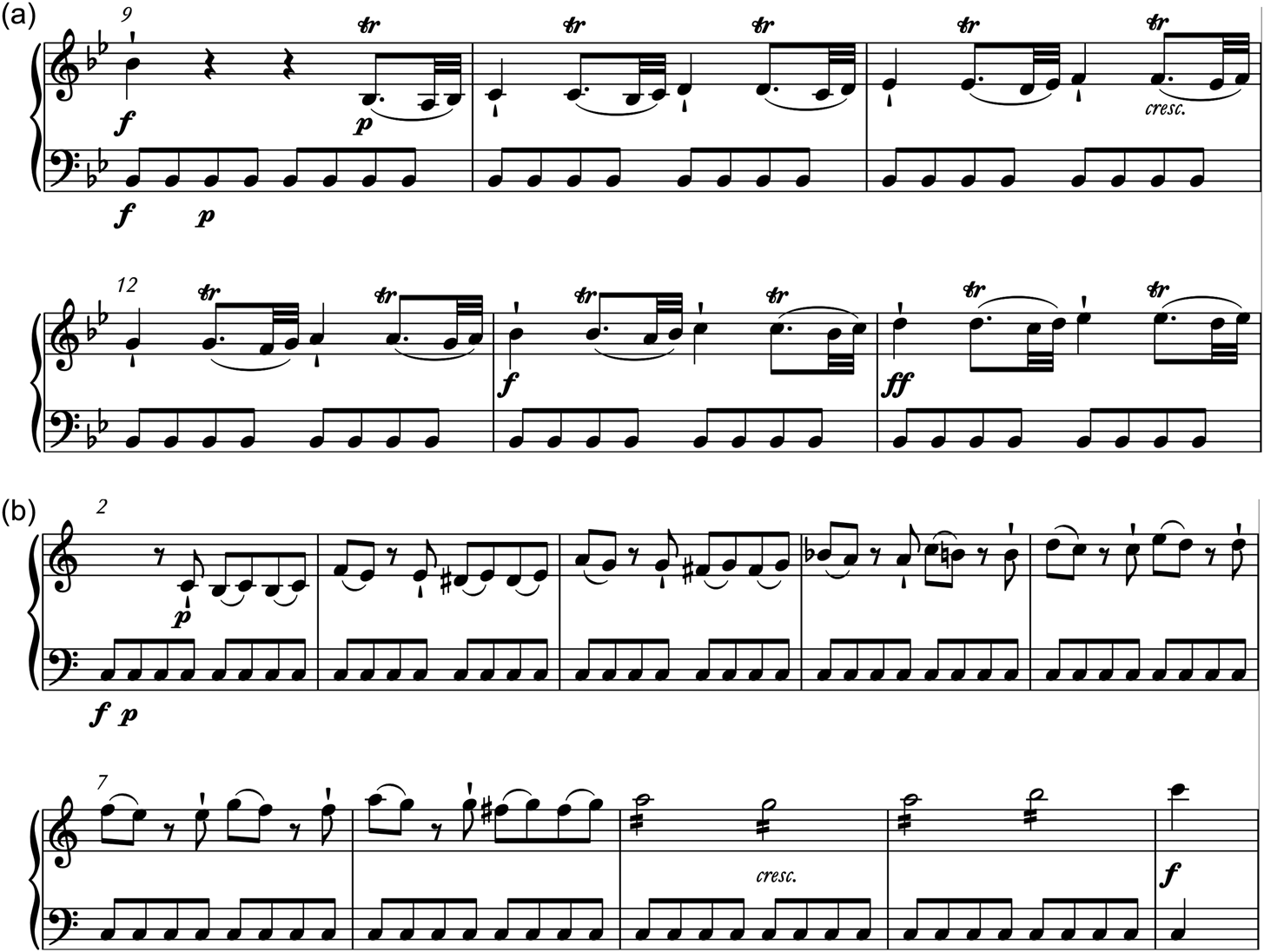

Broadly speaking, extrageneric embellishments occur in two structural contexts in Mozart's oeuvre: either across large-scale formal repetitions (such as the return of a rondo theme or, more often, when a melody introduced during an exposition is varied in the recapitulation) or on a more local level, when themes are repeated in closely juxtaposed phrases or periods. Both types of melodic variation can be found in works of all genres and over the entire course of the composer's career, from his earliest minuets to his late operas. Of these, the local embellishments have traditionally been overlooked in the critical literature, yet they demonstrate the full range of Mozart's art as a decorator, from the elaborate, ornate figuration nested in the Adagio from the Piano Variations k264 (Example 2a) to the more modest interventions juxtaposed throughout the first movement of the Piano Sonata k330 (Example 2b).Footnote 16

Example 2. Embellishments in juxtaposed phrases: (a) Piano Variations in C major k264, variation 8, Adagio, bars 1–3 and 9–11 (NMA series 9, group 26, ed. Kurt von Fischer (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1961)); (b) Piano Sonata in C major k330/i, Allegro moderato, bars 1–10 (NMA series 9, group 25, volume 2, ed. Wolfgang Plath and Wolfgang Rehm (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1986)

All of Mozart's notated embellishments – those composed into his models as well as those distributed throughout his other written works – provide a highly consistent picture of his practices as a decorator. Even so, it is clear that the formal context in which each figure occurs has some bearing on its rhetorical function. Embellishments are ultimately vehicles for the display of virtuosity, either by a soloist, whose elaborate textual interventions show off both technical prowess and improvisatory wit, or by a composer, who flaunts an inventive capacity to find melodic riches even in the simplest of tunes. For either a performer or a composer to show off by embellishing, however, the gestures must be recognized by listeners as being superadded. This, in turn, means that Mozart's expectations concerning his audiences’ sophistication and musical memory would most likely have played a role in his crafting of embellishments. During thematic returns in rondos, listeners even casually familiar with contemporary norms would probably be aware when a familiar theme was reintroduced; however, it is unlikely that on a first hearing they could be counted on to recall the precise contours of the original theme. As a result, embellishments added in rondos would need to compensate by advertising their presence through sheer density. Conversely, when embellishments occur in more closely juxtaposed phrases, the increase in melodic complexity would be more readily apparent, and the embellishments could explore subtler thematic alterations. In the first movement of the Sonata k330 (Example 2b) varied repetitions are so frequent, and occur in such close succession, that although the added figures are modest, the cumulative effect is one of a constantly shifting musical foreground in which each theme has barely been presented before it begins to transform. The same is true even in works whose themes are presented at slightly further remove, so long as they remain plausibly within the range of the casual aural memory. In the first movement of the Sonata k332, nearly every theme from the exposition is given in a simpler form before being restated in a more ornate version.Footnote 17

That Mozart was aware of the rhetorical potency of these juxtaposed variants is clear from the fact that he developed them in the earliest stages of compositional planning. From a modern-day vantage point, this may seem counterintuitive: because embellishments are associated with performance and improvisation, it is tempting to think of them as being afterthoughts in the creative process, established only after the structural fundaments of a work had been concocted and notated. Yet the presence of embellishments throughout Mozart's surviving drafts, sketches and fragments reveals that he often weighed the aesthetic implications of melodic decoration at the same time that he shaped the other elements of his compositions. Local embellishments are present in many of the drafts that Mozart left unfinished, including the divertimento fragment k288, the violin-sonata movements k372, k403 and k404, the string-quintet movement k514a and an insertion aria for soprano, k580. Some fragments consist of only two or three partly notated phrases, yet even the most abortive efforts often contain embellishments (Examples 3a and 3b). Embellishments are also included in many discarded sketches for works Mozart did eventually finish, such as false starts for movements within the Piano Concertos k453, k488, k491, k503 and k537 (Examples 3c and 3d), as well as in unfinished drafted versions of opera arias. It seems that embellishment formed an important element in Mozart's initial conception of each melody, even before it was clear to him just how – or indeed whether – those melodies would fit into a finished composition. Because the notational style of the fragments with embellishments does not differ from the notational style of his finished compositions, it seems likely that in many finished works as well, embellishments were committed to paper before Mozart had settled details of accompaniment, texture and even overarching form.

Example 3. Embellishments from Mozart's sketches: (a) Fragment of a string quintet, k514a, bars 29–37; (b) Fragment of a divertimento, k288/i, Allegro, bars 30–39 (both NMA series 10, group 30, volume 4, ed. Ulrich Konrad (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 2002)); (c) Piano Concerto in C major k503, sketch (discarded) (NMA series 5, group 15, volume 7, ed. Hermann Beck (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1959)); (d) Piano Concerto in D major k537?, sketch (discarded) (NMA series 5, group 15, volume 8, ed. Wolfgang Rehm (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1960))

A Musical Profile of Mozart's Embellishments

Because much of the literature on Mozartean embellishment is given to broad defences of the modern-day practice of departing from the composer's texts, little has been said on the musical characteristics of Mozart's gestures. Some aspects of his practice certainly evolved over the course of his career, and many gestures comprising individual embellishments are tailored to the movements in which they occur. Even so, it is possible to locate a number of features that remain consistent across his embellishment gestures.

First, Mozart's embellishments are all highly circuitous in their melodic shapes. Embellishments do not simply fill intervallic gaps between two pitches – they meander, changing direction multiple times while passing from one note of the original melody to the next.Footnote 18 This indirection occurs on multiple levels of musical structure. It can be seen most simply in the elaboration of individual intervals – for instance, when the ascending scalar figure that begins the Adagio variation of k264 (Example 2a) is embellished with a gesture that changes direction twice, first leaping down from c2 to c1 and then from c2 to g1 before arriving at the end-point of the original scale.Footnote 19 Melodic indirection can also apply at the level of entire phrases, when embellishments move against the composite shape of a given melody.Footnote 20 In many cases, these broader instances of indirection occur alongside octave transpositions (as in the embellished variation from the last movement of k284). Mozart generally uses such transpositions to prepare virtuosic scalar flights from the lower registers of the piano to the upper reaches of the instrument's range.

A second unifying feature of Mozart's embellishments is the liberal use of expressive melodic chromaticism. This represents one of the ways in which they align with and amplify his musical language as a whole, which is habitually and pervasively chromatic. In some cases, the chromatic alterations are slight, absorbed into the vocabulary of turns, trills and grace notes. Elsewhere, however, Mozart's chromaticism is deliberate and marked. Chromaticism is often linked to the affective profile of a passage, which is redefined through the insertion of local dissonances that add colour and alter a phrase's affective scope, either by suggesting its light, comic character (as in the flippant chromatic grace notes added in the last movement of the Piano Sonata k279) or by imbuing it with a depth and complexity more usually found in the composer's lyrical slow movements.

The third consistent feature of Mozart's embellishments is their use of measured divisions rather than the free runs, unmeasured tirades and other Italianate graces found in earlier eighteenth-century practice (familiar from the diminutions attributed to Arcangelo Corelli, Giuseppe Tartini and Pietro Nardini). Even those embellishments that sweep quickly across a large portion of the keyboard, such as the hemidemisemiquaver figures in the Adagio variation from k284, are woven from the same types of rhythms found throughout his compositions more generally – and indeed, even the gestures in k284 share scalar contour, affective sensibility and technical scope with various figures that are not embellishments, including much of the filigree in the Adagio variation from the Sonata k331. Although Mozart does occasionally wriggle free of this measured regularity, his departures are exceptions to an otherwise consistent norm, and generally occur only when the flow of metrical time slackens: within Eingänge, for instance. Aside from such free passages, Mozart's notated embellishments are so rhythmically staid that they tend to avoid even simple combinations of duplets and triplets within individual gestures, a device used by both Haydn and Beethoven in order to heighten the rhapsodic freedom of their soloistic embellishments in sonatas and concertos.

I have described these features of Mozart's embellishments in strictly technical terms. Yet each carries implications for the broader issues of expression and rhetoric. In particular, Mozart calibrates his use of all three features to maximize each passage's theatrical effect – that is, to heighten the implication of showiness. This is perhaps most readily clear in the use of melodic indirection. By introducing flamboyant changes of shape into his melodies, Mozart evokes a compositional and performative persona whose creative ingenuity seems virtually limitless. The series of repeated upbeats in the slow movement of the Violin Sonata k481 (Example 4) exemplifies this decorative alchemy, showing off a dazzling succession of ways that the opening gesture – a rudimentary descending triad – can be constantly reinvented and reshaped, yielding complexities that would be unavailable if the sole purpose of the embellishments were to connect two notes by the most efficient, direct means available. Although some of the decorated upbeats from k481 do precisely this, accomplishing the task with only one or two isolated changes of direction, the most characteristic introduce multiple digressions within the melodic foreground. Even more, many such decorations seem not only angled to the display of compositional inventiveness, but calculated for performative effect as well, laying the groundwork for gentle play against listeners’ expectations. In the final iteration of the k481 theme, one upbeat sustains a ‘wrong’ note a seventh higher than the original melody before, at the last moment, scrambling down to the intended point of arrival. Mozart successfully manoeuvres the embellishment to its destination, but only after playing up the delay and relishing the moment of suspense.

Example 4. Mozart, Violin Sonata in E flat major k481/ii, Adagio, upbeats to bars 1, 5, 13, 35, 39, 65, 69, 76, 80 and 88 (NMA series 8, group 23, volume 2, ed. Eduard Reeser (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1965))

The other technical elements of Mozart's decorations also contribute to this air of showmanship. The use of chromaticism does so by blurring the structural functions of each note and, as a result, creating a complex haze that loosens the perceived relations between original melody and embellishment, and between embellishment and harmonic structure.Footnote 21 Even Mozart's metrical regularity contributes to his aesthetics of display, since against the constraints of timing and rhythmic evenness, the on-time arrival of embellishment gestures on the correct metrical pulses seems all the more impressive, especially if an audience believes that the performer is improvising. The introduction of new melodic direction and complex chromaticism occurs without undermining the metrical integrity of each phrase.

Patterns of Decoration in Mozart's Embellishments

This sketch, though brief, has moved swiftly from the familiar framework in which Mozart's embellishments are described, in terms of individual notes and gestures, to that of overarching aesthetic function – a topic I examine more fully below. That the relevant explanations involve multiple levels of specificity and abstraction itself suggests one reason that a focus on local figurae rather than higher-order protocols is unjustified. The expressive import is not determined by gestural content alone. Equally important is the way the gestures are deployed alongside each other, both within individual phrases and over the course of each movement as a whole.

Pacing of embellishments within individual phrases

In many of Mozart's rondos and rondo-like slow movements, the unfolding of embellishments follows the expected trajectory, with the density of figuration increasing with each thematic iteration. This is not always the case: in the Rondo in A minor, k511, for instance, one statement of the theme dispenses not only with added embellishments but even with the turns that adorn the melody on its first appearance. A similar stripping-away of figuration occurs in the final thematic statement in the rondo-finale of the Sonata k533. For the most part, however, figuration increases when a theme is reintroduced.

Yet within individual phrases, Mozart's practices are somewhat more complex. Although each iteration of a rondo theme does generally bring added embellishments, these are rarely distributed evenly throughout the phrases in which they occur. Generally, new embellishments are added only to half of each phrase at a time. In the slow movement of the Sonata k457, the melodic material of bars 1–2 is repeated in bars 4–5 (Example 5a and 5b). However, embellishments are added only in bar 4, whereas bar 5 simply restates material from bar 2. The embellishments added in bar 4 are striking for their density and variety. Over a mere four beats, Mozart draws upon a range of techniques including melodic indirection, divisions, repeated notes, changes of articulation, local graces (in this case, a turn) and an added upbeat. This variety is condensed into the smallest possible space; despite the ample room for further elaboration in the next bar, Mozart retains the plainer contours from the theme's earlier appearance. The same holds throughout the remainder of the movement. In bars 20–21 (Example 5c), the material presented in bars 4–5 is repeated with embellishments. This time, decorations are applied only to gestures originally appearing in bar 5 rather than to material from bar 4. This pattern does eventually break down, since the figuration, constantly accumulating, inevitably spills into other portions of the phrase. None the less, in most repetitions here and in other works, new embellishments are added in only half of a phrase at a time.

Example 5. Mozart, Sonata in C minor, k457/ii, Adagio: (a) bars 1–2; (b) bars 4–5; (c) bars 20–21 (NMA series 9, group 25, volume 2, ed. Plath and Rehm)

Which half of a phrase receives embellishments is itself subject to variation. In k457, decorations are generally (though not always) applied to the first rather than the second half of each phrase. In the Rondos k494 and k511, the earliest embellished reprises focus not on the first bars of the theme, but on the second or third. The underlying logic of this choice is not entirely apparent, but one possible correlation involves tempo. k494 and k511 are comparatively faster than the Adagio from k457, and the themes therefore derive some of their forward momentum from their rhythmic gestures. Excessive embellishment in the first bar might obscure the emblematic rhythm of the rondo theme, and with it the works’ structural rhetoric. In k457, on the other hand, the very concept of momentum seems at odds with the slow tempo and gentler expressive profile. Here it is the embellishments rather than the rhythmic motives that establish the qualities of lyricism and grace, and it is perhaps for this reason that Mozart front-loads them in the thematic returns. In any case, the pattern of embellishing only one portion of a phrase at a time is maintained in movements such as these, irrespective of tempo or form. Maximum variety is applied within the smallest feasible subsection of each phrase.

This pattern does not hold, however, during closely juxtaposed motivic repetitions woven throughout the musical fabric of other works. In these cases, embellishment is sustained throughout each phrase as a whole, rather than in only a portion of each phrase. This approach can even be seen in rondo movements such as k457 and k511, in embellished versions of melodies other than the movements’ primary themes. Such versions are inserted wherever the texture will allow, with little sense of deliberate pacing. As with the choice of which half of a phrase to decorate, this decision may have been largely random – or perhaps it may be linked to the rhetorical functions of juxtaposed embellishments described briefly above. In a formal thematic return, the repetition will be marked, and the purpose of decoration will be to impress listeners with florid density, a goal Mozart most readily achieved by squeezing as many gestures as possible into a small portion of each phrase. In closely juxtaposed repetitions, the task is not to obscure the phrasal contours with a superfluity of embellishment, but to sustain a more deliberate increase of melodic density.

Motivic unity within embellished passages

In Mozart's variation sets, each individual variation tends to draw upon a particular technical or musical device: hand-crossing, melodic divisions, triplets, modal shifts, harmonic elaboration and so forth. The same logic occasionally applies to embellishments in the composer's rondos and slow movements. The Andante from the Piano Sonata k309 demonstrates the variation-like distribution of embellishments throughout a non-variation movement. With every thematic return, a different style of decoration is applied: first grace notes (bar 17), then demisemiquaver divisions (bar 20), then semiquaver triplets (bar 28), then rhythmic elaborations (specifically, Lombard rhythms) and added scales (bar 45), then doubled octaves in the right hand (bar 48). This continues through the movement, with subsequent repetitions introducing divisions in both the right and left hands, voice exchanges between the hands and broken octaves. Each of these elaborative devices is confined to its own phrase; grace notes and doubled octaves, for instance, are never mixed in a single reprise.

Yet the slow movement of k309 is unusually strict in the organization of its embellishments. Few of Mozart's other embellishments evince a comparable degree of planning. None the less, a developmental logic of the melodic surface can often be glimpsed, even where the composer seems to eschew explicit figural unity. In the Rondo k494, one iteration of the theme initially replaces a descending stepwise figure with leaps, and then embellishes a further, internal repetition of the same figure with semiquaver divisions (Examples 6a and 6b). The decorations here represent an instance of internal, progressive elaboration. The faster embellishments are not decorations of the original figure so much as decorations of the decorations presented in the previous bar. A glance at the Rondo as a whole shows that such nested embellishments amount to a developmental principle used throughout the piece, with similar juxtapositions and increases of local density occurring in three subsequent phrases (one of which is shown in Example 6c). What seems at first glance to be a haphazard accretion of elaborative complexity is, in fact, a series of internal increases of figural density that unfold with a careful logic. This suggests yet another point of divergence from the variation genre, an environment whose increases of complexity are comparatively methodical, with most elaborative alterations sustained across a theme that lasts anywhere from eight bars (k455) to forty-four (k613). In contrast, the increase of density in embellishments is surprisingly rapid – yet it is largely as a result of these internal intensifications that Mozart is able to ratchet up the gestural density so quickly without sacrificing the coherence that attends each movement as a whole. Embellished returns begin by drawing on rhythmic values that are already familiar from previous phrases while simultaneously preparing the ear for the incremental increase of speed that will take place in subsequently repeated gestures.

Example 6. Mozart, Rondo in F major, k494, Andante: (a) bars 1–3; (b) bars 45–47; (c) bars 89–91 (NMA series 9, group 25, volume 2, ed. Plath and Rehm)

Comparable organizing principles operate not only on the level of the individual phrase, but at the level of the period as a whole. The clearest of these is a chiasmus-like pattern that links the embellishments introduced at the outset of a period to those introduced at the end, while taking a different approach in the middle where the two phrases meet.Footnote 22 In k494 (Example 7a), one thematic appearance presents tied syncopations followed by chromatic divisions (bars 83ff); this is answered by a phrase in which chromatic divisions are introduced, followed by tied syncopations (bars 89ff). Similar structures occur in k511 (Example 7b). The final thematic return from bar 151 is presented first with leaps and turns, followed by stepwise, portato divisions. The next phrase, from bar 155, reverses this pattern, beginning with those stepwise divisions before reintroducing leaps and turns. This pattern, used consistently throughout Mozart's rondos, suggests a tightly controlled balance of unity and contrast similar to that governing the pacing of embellishments within individual phrases. On the one hand, local variety is maximized through the juxtaposition of disparate embellishment styles – a rhetorical effect that Mozart may have valued particularly for its simulation of inventive, improvisatory freedom, as the player, having initially set out embellishing in one style, seems to follow a momentary whim by pursuing a different mode of elaboration. Having introduced a hint of digressiveness into the embellishment, however, Mozart counterbalances this impulse with a return to the original decorative strategy. He thus lends coherence to each period, if only in hindsight.

Example 7. Embellishment chiasmus: (a) Rondo in F major, k494, bars 83–94; (b) Rondo in A minor, k511, Andante, bars 151–157 (NMA series 9, group 27, volume 2, ed. Wolfgang Plath (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1982))

Pacing across multiple phrases

In works with a repeating theme, embellishments from the first repetition of that theme tend to become the musical backdrop for all subsequent repetitions. The turn that graces the first two notes of k494, the divisions added to the first two notes in the Adagio from k457 and the turn presented in bars 10 and 14 of the second movement of the Piano Concerto k466 – all of these are given in the first embellished recurrences of their movements’ principal themes, yet they also recur in most if not all subsequent appearances of that theme, regardless of other figuration added along the way. Likewise, in the slow movement of the Violin Sonata in E flat major k481 the gestures presented in bars 13–14 are elaborations of the embellishments in bars 5–6 rather than of the originals in bars 1–2. The same can be said even of the embellishments in bars 84–87, which are related in melody, structure and rhythm to those presented in bars 11–12 rather than to the simpler originals in bars 9–10. In such cases, it is tempting to consider the first-time melodies as ‘de-embellished’ versions, whose more fully decorated identity is actualized only upon repetition.Footnote 23 Considering the length of the k457 and k481 slow movements, it is striking that the pattern is sustained to the end of each work, with even the final embellishments maintaining their structural and stylistic ties to the first variants rather than to the myriad other possibilities Mozart might have conjured instead. Here, as before, the rhetorical effect of decorative variety is carefully offset by a more staid, deliberate progression from one thematic repetition to the next.

This structural protocol, in which subsequent embellishments are developed out of those presented in the first repetition of a theme, is not limited to rondos, but also governs the use of embellishments in some binary and sonata-form movements. In the Sonata k330, for instance, the first bar of the second theme is written as a quaver with a chromatic grace note. One beat later, the figure is embellished as two semiquavers. When the theme repeats in the following phrase, the semiquaver version is given first, before the figure undergoes further elaborations. The same pacing is evident in Mozart's published embellishments for the Sonata k332. The descending arpeggio in bar 29 is embellished one bar later with a descending scale. When the theme returns in bar 33, the embellished version is repeated before further decoration is introduced. The same applies to Mozart's works for other instruments and in other genres. In the Andante from the ‘Haffner’ Symphony, k385, a descending arpeggio in semiquavers (bar 23) is embellished four bars later with demisemiquavers, and when the passage recurs at the end of the movement Mozart proceeds directly to demisemiquavers (bars 72 and 76) rather than restating the original arpeggio in semiquavers first. Likewise, in the Piano Trio in G major k496 a bar-long figure from the exposition (26) is treated with embellishments in juxtaposed recurrences (28–29), and it is to this elaborated version that the recapitulation immediately moves (138). The same occurs in the slow movement of the String Quintet k593, as well as in various opera arias.Footnote 24

Mozart's Aesthetics of Embellishment: Character, Virtuosity and Play

For Mozart, the structural precepts that guided embellishment served a high-order communicative function. We have already seen hints of the various ways in which the deployment and pacing of embellishments might hold aesthetic or communicative significance, shaping listeners’ experiences of a work. We can now explore the nature of this significance in more detail and follow its implications through a wider range of interpretative issues.

The first point of significance, one I have already introduced, involves the function of embellishments as a signal of virtuosity. I have already suggested some reasons that this is the case, among them the simple fact that a greater density of notes often implies a greater level of display on the part of a performer. The embellishments Mozart composed into his concertos and arias always serve the relatively straightforward purpose of differentiating the soloist from the accompanying forces on these familiar grounds. This function, however, also points beyond the evocation of virtuosity and towards the expressive character the soloist embodies when performing a concertante work. Embellishments do not only add notes; they also alter the affect of the soloist's line, and in doing so they suggest a degree of expressive autonomy that outstrips that of the ensemble. In the Piano Concerto k453, the first violins present the initial theme in bars 1–4, which is then repeated one step higher, but otherwise unaltered, in bars 5–8. When the soloist enters at the end of the ritornello, the structure of the phrase is maintained, but the added decorations – both as a lead-in to the theme and during the thematic repetition itself (79–82) – immediately mark off the soloist as an individual musical agent who operates in collaboration with the ensemble but remains expressively distinct. The motive presented in the violins at the outset of the movement is ambiguous in its expressive profile; it is not yet clear whether the gentle stabs of melodic chromaticism are playful, beseeching or searing. For the soloist, however, the passage is firmly entrenched in the comic – a designation that arises almost entirely through the embellishment gestures, whose circling gruppetti seem to have fun at the expense of what was previously a more neutral utterance.

As already noted, however, virtuosic displays are not only the province of soloists. They also suggest a virtuosic compositional presence embedded within the music. This presence has little to do with instrumental or vocal ability as such, and instead flaunts the composer's creativity, imagination and powers of melodic invention. Embellishment is an act through which the composer lavishes expressive riches on a melody, and reveals the depths concealed even within the simplest of tunes.Footnote 25 In some works, the embellishments themselves define the nature of the compositional persona, which attempts ceaselessly to impress listeners through sheer melodic technique. This is particularly true in works whose embellishments draw attention to themselves, either through flamboyance during formal repetitions, or through the constant shifting of melodic substance during more closely juxtaposed passages. When the presence of embellishments becomes sufficiently regular as to be predictable, then with every thematic recurrence Mozart dares his listeners to predict just what inventive bounty he will spin out this time. The thematic returns in the Rondos k494 and k511, and the phrase-by-phrase motives decorated incessantly throughout the first movements of k330 and k332, all show Mozart at his most restless. Topic theorists have traditionally seen these works (particularly the first movement of k332, the classic case study for scholars from Allanbrook to Hatten) in terms of disparate rhetorical stances that unfold with each successive phrase.Footnote 26 However, alongside the cluttered succession of topics and styles suggested by these analyses, the constant focus on embellishment also brings with it a more sustained perspective that binds the many expressive states into a coherent whole. The embellishing composer is a constant, watchful presence: every new theme is treated with the same elaborative ingenuity that structures the other phrasal repetitions as well.

The compositional persona I have attributed to Mozart in this case is indicative of a general interpretative mode associated with embellishment. To hear the aesthetic thrust of a work as arising through the use of embellishments is to hear in it a more thoroughgoing sense of restlessness than might otherwise be apparent. Mozart does not wait for a performer to improvise additions after a composition is complete. Instead, he actively probes the melodic foreground of the movement, tinkering with its shapes and exploring the ever-shifting relationship between melody and expression. The result is not simply a sensitivity to variety of the surface; it is also a more deeply embedded sense of musical process and progress. Embellishments establish an arrow of time, a forward propulsion by means of which each bar, each motive, each thematic repetition is like the previous one, only more so: more ornate, clearer in its affective scope and more elaborately laden with melodic invention. This sense of linearity and progress complements the directional ‘arrow’ that has been located in other parameters of Mozart's style – for instance, the relative strength and weakness of the various cadences arrayed one after the other in his larger formal plans.Footnote 27 Yet whereas such non-melodic devices are located on a deep level of structure and may elude some casual listeners, embellishment operates within a parameter of the music that closely defines the trajectory of a work in the ears of listeners – and, not coincidentally, in the formal planning of many eighteenth-century composers.Footnote 28 All of this means that embellishments do not simply constitute a locus of affective layering that gives each iteration of a melody its unique expressive character. They also serve as rhetorical anchors for a work's formal and expressive path as it unfolds from first phrase to last.

So far, I have invoked the concept of ‘character’ primarily as a metaphorical expedient for describing the expressive processes that unfold in Mozart's melodies. However, the use of embellishment also calls up more concrete manifestations of the same ideas. This function is deployed with particular clarity in Mozart's chamber works, where melodic lines played by individual performers often serve to depict various modes of social interplay. In the Violin Sonata k454, the pianist and violinist participate in a number of musical dialogues that unfold specifically through an exchange of embellishments. Both players build upon each other's decorations in the slow introduction to the first movement as well as in the thematic reprise of the second movement: two good-natured conversations that prefigure a more flamboyant battle of virtuosity staged in the final phrases of the sonata's last movement.Footnote 29

The designation of musical character is, of course, at its most concrete in the realm of opera – and here too embellishments often serve in both the evocation of musical personae and the depiction of various dramatic situations, particularly those involving spontaneity or improvisation among the characters on stage. In both the Act 1 and Act 2 finales of Die Zauberflöte, Papageno's attempts to play his magic glockenspiel are animated by virtuosic divisions. Indeed, so profligate are the glockenspiel's embellishments in the Act 2 finale that they ultimately spill over the boundaries of melody and give rise to a variation in which the tune is carried by the wind instruments. Tamino's eponymous flute, too, embellishes in the Act 1 finale, though its decorations are not as extensive as those produced by Papageno's glockenspiel. Embellishment also serves as a signifier of improvisation in Così fan tutte. When Despina dons her disguise as a notary in the Act 2 finale and devises a marriage ceremony in quasi-patter, each of her phrases is set against a background of orchestral embellishment during which a single chord progression is repeated with increasingly complex figuration. Here, it is not only the onstage character who participates in the feigned improvisation, but the orchestra as well. Every facet of the musical texture is angled towards the display of dramatized spontaneity, the embellishments serving as its rhetorical marker as well as the primary vehicle for development and motion.Footnote 30

If embellishment serves Mozart as a signifier for musical characters and dramatic situations, it is also implicated in various forms of musical narrative. We have already seen that, on a purely technical level, embellishments suggest an arrow of time: a local telos by which various iterations of a theme become successive and additive rather than parallel. Yet the plot-like unfolding of musical compositions and embellishments need not arise only across successive phrases in the large-scale development of a movement, but may also be found within the contours of individual lines. For instance, embellishments may disrupt expectation by introducing deviations into familiar melodic lines. The fundamental linearity of melody – that sense of internal causation whereby each note seems to ‘move towards’ the next, and which binds each melody into a coherent whole – is a musical phenomenon that itself can be exploited and disrupted through the digressiveness of embellishments. It is interesting to note that this aesthetic facet of embellishment is mirrored in Mozart's development as a melodist more generally. Mozart's early compositions feature countless passages such as the drawn-out ascent from the Symphony k22 (Example 8a), where the eight-year-old composer establishes a consistent pattern and follows it for two octaves. By 1775, however, Mozart had begun to cultivate a more circuitous language, one in which the attributes of his indirect, chromatic embellishments had been absorbed into the fabric of his melodic writing as a whole. This development is epitomized by a parallel passage in the overture to Il re pastore (Example 8b) whose superficial similarity to k22 makes the differences all the more striking.

Example 8. (a) Symphony in B flat major k22/i, Allegro, bars 9–14, first-violin and bass parts only (NMA series 4, group 11, volume 1, ed. Gerhard Allroggen (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1984)); (b) Il rè pastore, overture, Molto allegro, bars 2–11, first-violin and bass parts only (NMA series 2, group 5, volume 9, ed. Pierluigi Petrobelli and Wolfgang Rehm (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1985))

Both gestures occur at the outsets of their works; both ascend at least an octave and a half, and both rely on a similar orchestral effect – a coordinated crescendo, characteristic of the Mannheim school, which provoked more excitement than perhaps any other gesture used by virtuoso eighteenth-century orchestras.Footnote 31 Yet against these constants, an aesthetic gulf separates the passages. The symphony is diatonic, whereas the overture is chromatic. The symphony is rhythmically regular, whereas the overture is jagged and varied. In the overture, after three iterations of the initial quaver pattern, Mozart simultaneously alters the length of the cellular motif and introduces chromaticism by lowering the leading note. He maintains the new, quicker version for another octave, until, just as the scale seems to approach its peak, he lengthens the pattern once again and introduces a change of melodic direction which further delays the anticipated arrival. Such passages are of a piece with Mozart's embellishments, which wend their way through melodies by introducing a tangle of new shapes and sub-shapes and meander through a series of harmonic implications and expressive shadings on the way to their destination. Although it has become a cliché of Mozart scholarship to praise the guileless simplicity of his tunefulness, with Scott Burnham even comparing Mozart's melodic shapes with the ‘lines of grace and beauty’ developed by William Hogarth,Footnote 32 Mozart's devious and digressive melodic style seems rather more of a piece with the famous plot-line diagram from Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy, completed just a decade before the onset of Mozart's maturity (Figure 1).Footnote 33 In both Mozart's embellishments and Sterne's narrative, disruptions to the linearity of the surface are elevated to the level of an artistic trope – though in Sterne's case, both the content and presentation of the diagram are resolutely comical, whereas the circuitousness of Mozart's embellishments is just as often deployed in the service of expressive lyricism.

Figure 1. (a) Embellishments from k481, second movement; (b) Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, nine volumes, volume 6 (Becket & DeHondt, 1762), 152

This is not to say that Mozart's embellishments never enhance the comedic effect of a passage. They do, as do his melodies more generally. David Huron has theorized that musical humour in a plethora of contexts arises from a small selection of techniques, including implausible delay, incompetence cues and excessive repetition, to name three features relevant here.Footnote 34 The Mannheim crescendo in the Pastore overture aims at a musical arrival-point which, though well in sight, proves difficult to reach – an echo of my appraisal of the final embellished iteration of k481 (see Example 4), which flirts with a failure to conform to the original melodic shape before, at the last moment, scrambling so as to preserve the expected alignment. Embellishments also occasionally participate more explicitly in musical humour, as in Ein musikalischer Spass, among whose many pratfalls is the violinist's awkward attempt to bring off an embellishment unsuited to string writing.Footnote 35

We may go still further, and posit that embellishment is, quite literally, a playful game for Mozart. That is, many of Mozart's embellishment procedures mirror what the philosopher Bernard Suits has identified as constituent components of the ludic mentality. According to Suits's classic account of the subject, gameplaying occurs when players introduce a series of constraints that serve as obstacles to the achievement of an arbitrary goal.Footnote 36 In a game of chess, for instance, each player's arbitrary goal is to seize the opponent's king. In the absence of any rules, the most efficient way to do so would simply be to grab the piece at the outset and declare victory. Yet the essence of chess lies not in the mere realization of this goal, but in its pursuit in light of the game's rules. Players must adhere to strictly defined laws governing the possible movements of each piece, and it is only within these constraints that a game of chess takes place. Suits points out that this definition can be generalized beyond the realm of traditional board games. He takes as an example the story of a fictional commuter with two possible paths home: one short and direct (the ‘efficient’ route), and the other circuitous (and thus ‘inefficient’). The commuter might choose a path for any number of reasons: in the case of the shorter route, to save time; in the case of the long route, perhaps to enjoy the scenery. In this example, the commute is not yet a game – but this is changed if an arbitrary goal is introduced along with an external constraint. The goal might be to arrive home early, with the constraint being that the commuter must take the less efficient route; the goal might even be to reach home later, with the constraint being that the commuter must take the more efficient route and yet not arrive too early. In either scenario, the commute becomes a one-player game.

This account of games applies directly to Mozart's music. Before turning to embellishments in particular, a broader analogy will clarify the relevant comparisons. Suits's scenario finds an exact counterpart in the account of Mozart's retransitions developed by Leonard Meyer.Footnote 37 Mozart's retransitions often begin with a circle progression that implies a specific path towards the recapitulation. Although Mozart tends to deviate from the established pattern before reaching the destination, the recapitulation generally arrives just when it would have had the original pattern been maintained. In effect, Mozart sets up an efficient if banal means to reach a predetermined goal at a given time, and then deviates so as to explore a more interesting and circuitous route to the same destination – with the external constraint that the detour must take precisely as many bars as the efficient route would have taken.

Embellishments participate in the same type of gameplay, on two levels. The first level is concrete, as suggested by the musical content of the figures themselves. Embellishments, like Mozart's retransitions, draw upon notions of route, destination and time frame – not in their formal or structural implications, but in the nature of their melodic shapes and the gestural process that gives rise to them. Because the original, unembellished version of a melody dictates structural and functional points that embellishments must track, the act of embellishing can be understood as a ludic challenge to composer or improviser. The music must arrive at a specific melodic destination at a given metrical point in a phrase, but must also introduce deviations along the way, complicating the path from one note to the next. Some of these deviations might take the form of new, chromatic shadings which the player must navigate, but others are more firmly performative, related to the introduction of virtuoso instrumental or vocal techniques which make a phrase not only more complex but more difficult to execute.

The second level involves not the content of the gestures, but the practice that gives rise to them. The most efficient way to produce a melody conforming to a particular set of precepts is, of course, to compose it in advance rather than to improvise and risk failure. That Mozart adopted a highly prescriptive system of notation when preparing works for publication suggests that he was fully capable of codifying his texts when he so wished, and this means that when he employed skeletal notation he did so by choice – perhaps to save time, but perhaps also for the private, improvisatory challenge such passages would present.Footnote 38 It is interesting to recall that Mozart often hid his improvisatory excursions behind the pretence of reading finished compositions, for instance by putting blank pages on the music desk while improvising the keyboard part to the Violin Sonatas k379 and k454. If this represents a kind of gameplay, it is one Mozart probably pursued for private pleasure. Indeed, even the use of decoy pages would raise the improvisatory stakes, since a failure to invent appropriate music would be all the more egregious if the performer seemed to be reading from a written score.

These issues of character, drama and narrativity return us to the realm of performance and interpretation, where this study began. At the outset, I expressed concern at the tendency to interpret Mozartean embellishment in terms of notes and individual gestures, without a view of the broader aesthetic ramifications of such gestures as they are used throughout his oeuvre. It is now possible to see why. Embellishing is, ultimately, an exercise not so much in the simple addition of notes as in the interpretation of a musical text. Some embellishments illuminate a passage's affect, as do the humorous gruppetti from k453. Others disrupt, pushing against the prevailing character of a phrase or recasting it entirely. In all cases, decisions about how to embellish, as well as an analysis of embellishment, must stem from an interpretative understanding of the music into which they are inserted, and, most of all, from an awareness of the compositional voice whose presence guides the work in question.

The ideas explored in the previous pages, despite the variety of theoretical approaches I have employed, all converge on a handful of points. Verbatim repetitions are eschewed at the formal, phrasal and melodic level, while local motives are used in such a way as to heighten the playfulness and digressiveness suggested by each phrase. In hindsight, it is clear that the criteria described so briefly here are reflected throughout the embellishment protocols enumerated earlier. The fact that Mozart tends to embellish only half of a phrase at a time rather than risking the monotony of pervasive variation; the fact that the embellishment chiasmus facilitates the juxtaposition of unlike gestures while maintaining an overarching phrasal coherence; the fact that embellishments accumulate at different paces within interlaced phrase units – all of these demonstrate the ingenuity with which Mozart applies a criterion of unpredictability to his embellishments. Indeed, he even cultivates this aesthetic on the largest of scales, in the development of entire movements. A glance at the embellishments applied to the opening upbeat of k481 (again see Example 4), for instance, shows a process calculated to maximize variety. The first three iterations increase rhythmic density, with the third introducing melodic indirection and chromaticism. In the fourth, the rhythm slackens and the chromaticism vanishes. Semiquavers are reintroduced in bar 38, but these, too, are removed from the following return. Bar 68 imitates bar 12, but bar 75 veers away, this time introducing triplets. Only the final two iterations seem straightforwardly additive, yet it is here that Mozart flirts most daringly with large-scale digressiveness and the threat of failure.

Whatever meaning we derive from these embellishments – their tightly structured unpredictability, the creative ingenuity they evince – we do so by virtue of the broader explanations we adopt when approaching Mozart's texts. Surprise and unrest may not come readily to mind when first examining this repertory, yet such expressive designations provide an organizing lens through which to understand Mozart's works and the gestures that populate them. An overarching explanatory framework of the type suggested by Meyer has not seemed necessary for analyses of Mozartean embellishment; indeed, on some level, Bilson may have been correct in his claim that we know everything there is to know about the individual figures that constitute Mozart's decorative vocabulary. Yet it is only through the search for structural, processive and expressive explanations that the interpretation of Mozart's embellishments can proceed: that the figures can be related to the original melodies they adorn, and that the protocols guiding their use can be discerned. If in this article I have proposed new ways to think about the functions of embellishment, the next step is to apply these ideas back to the world of performance inhabited by Baillot, Irving and Bilson, and to discover what further interpretative depths are available when approaching Mozart's embellishments anew.