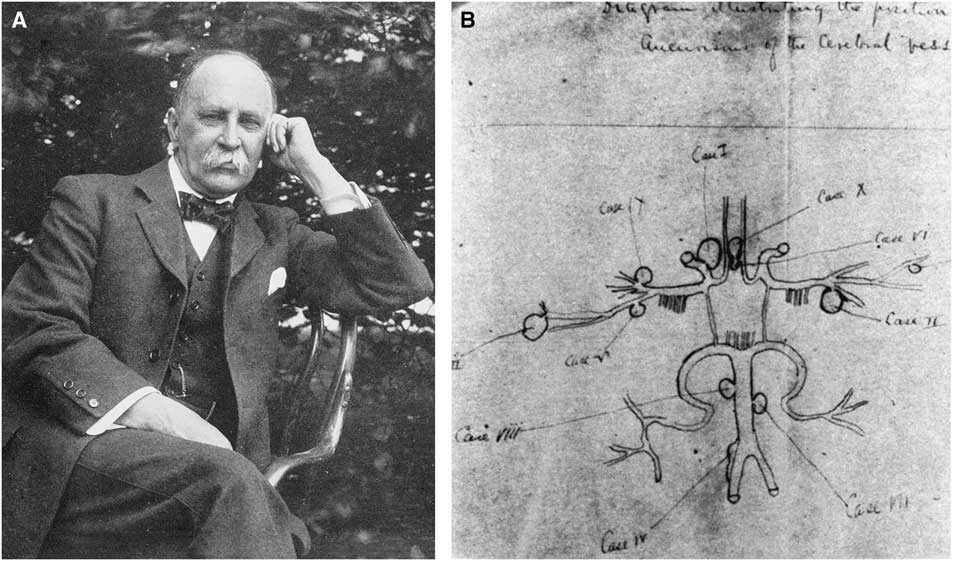

Early Canadian interest in vascular disorders of the brain was first demonstrated by William Osler (1849–1919; Figure 1A). Born in Bond Head near Toronto, Dr. Osler obtained his MD degree at McGill University in 1872. He was appointed to a post in medicine and pathology there in 1873. In 1886, he wrote on intracranial aneurysmsReference Osler 1 based on a series of approximately 1,000 autopsies (1875–1885). An unpublished sketch found in 1928 by W.W. Francis showed 10 aneurysms—two of the basilar trunk and the remainder in the anterior circulation (Figure 1B).Reference Feindel 2 In an editorial in 1889,Reference Osler 3 Osler considered intracranial hemorrhages as “suitable for operative interference,” as well as abscesses and neoplasms. William Lougheed, writing in Youmans’s textbook,Reference Lougheed and Barnett 4 praised Osler’s accurate postmortem description of an intracerebral hematoma from a ruptured middle cerebral artery aneurysm.Reference Osler 5 Osler recognized transient ischemic attacks—such as episodic aphasia, paralysis, and visual disturbancesReference Osler 6 —including that of his friend, Dr. George Ross, mentioned in his 1892 textbook. In 1874, Osler was possibly the first to recognize platelets as a distinct component of blood and that they aggregated in shed blood together with strands of fibrin, but he did not elucidate their origin or role in cerebrovascular disease.Reference Cooper 7 , Reference Osler 8 In his textbook, he wrote about cerebral arterial occlusions but felt they were of embolic origin, rather than thrombotic, and described cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

Figure 1 (A) Photograph of Dr. William Osler, circa 1912. Reproduced from Wikimedia Commons. (B) Osler’s complete sketch of cerebral artery aneurysms. Reproduced with permission from Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;254:255.

Later, as professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins, Osler met and influenced Harvey Cushing, then a surgical resident under William Halsted, professor of surgery. Osler, more than Halsted, encouraged Cushing’s pursuit of neurosurgery, and indirectly that of Walter Dandy and later Wilder Penfield. Cushing wrote the chapter on “Diseases of the Nervous System” for the sixth edition of Osler’s textbook The Principles and Practice of Medicine, and also a Pulitzer Prize–winning biography of Osler in 1925.

Operative treatment at that time was by Hunterian ligation of the cervical carotid arteries. The first to clip the neck of a posterior communicating aneurysm was Walter Dandy in Baltimore in 1937, using a McKenzie “silver clip.”

Kenneth McKenzie (1892–1964, born in Monkton, Ontario, MD Toronto, 1914, son of a physician) was the first “dedicated” neurosurgeon in Canada. After serving in World War I, then working three years in general practice and general surgery, he obtained a fellowship with Cushing in Boston in 1923–1924. He returned to Toronto and modified the Cushing silver clip in 1927.Reference McKenzie 9 He devised an instrument to punch out a uniformly V-shaped clip from a flat wire, and special clip holders to apply them. This was in contrast to the U-shaped Cushing clip. McKenzie claimed that the Cushing clip could close at the tips, but not reliably or completely at its proximal part, and possibly did not totally occlude the vessel. He felt that the V-shaped clip was more likely to accomplish this. McKenzie’s V-shaped clip was the forerunner of the present day hemostatic vascular clip. While used to control bleeding from vessels in general, it is not known if these had been used for cerebral aneurysms until Dandy’s report in 1944.Reference McKenzie 9 , Reference Dandy 10 The Olivecrona clip was a modification of McKenzie’s clip, adding proximal wings to the blades and permitting opening of the clip for readjustment. Charles Drake mentions that both McKenzie in Toronto and William V. Cone in Montreal (born 1897 in Iowa, MD Iowa, 1922, associated with Wilder G. Penfield as cofounder of the Montreal Neurologic Institute 1934) had excised aneurysms, as reported in 1938 at the annual meeting of the Harvey Cushing Society.Reference Drake 11 Cone’s experience was probably an anterior communicating aneurysm.Reference Johnson 12 Until retirement in 1952, McKenzie’s career in Toronto firmly established neurosurgery as a specialty in Canada. He began the first neurosurgical residency program in Canada and trained Frank Turnbull, Harry Botterell, William Lougheed, and Charles Drake, among others. McKenzie was president of the Cushing Society in 1936–1937 and also of the “Senior” Society of Neurological Surgeons in 1948–1949. During the 1940s and 1950s, surgical treatment of the cervical and cranial vasculature made steady progress. McKenzie apparently said that aneurysm surgery was a game for younger surgeons, and he then left it to his juniors in Toronto to pursue.Reference Drake 11

Interest in the planned surgical treatment of vascular diseases of the brain increased after the introduction of angiography by Egas Moniz in 1927, exposing the cervical carotid artery directly. Frank Turnbull (1904–2000, MD Toronto, 1928) reported on percutaneous carotid angiography in 1939,Reference Turnbull 13 three years after Loman and Myerson. Turnbull, the first neurosurgeon to practice in Western Canada (Vancouver), was president of the Harvey Cushing Society in 1949–1950.

E. Harry Botterell (1906–1997, born in Vancouver, MD Manitoba, 1930) began training in Winnipeg and Montreal and went to Toronto in 1932, teaching physiology under Charles H. Best (honored with Nobel Prize winners Frederick Banting and John McLeod for the discovery of insulin in 1923; in the 1930s, Best also pioneered in the isolation and clinical use of heparin), and anatomy under J. C. Boileau Grant (of the Atlas of Anatomy). He became a resident under W.E. Gallie (who described a technique for C1–C2 fusion) and between 1934 and 1935 was a house physician at Queen’s Square in London, England. From 1935 to 1936, Botterell did a research fellowship in neurophysiology at Yale under Dr. John Fulton and worked with A. Earl Walker (1907–1995, born in Winnipeg, MD Alberta, 1930, later professor of neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins; known for the Dandy–Walker and Walker–Warburg syndromes) and D. Denny Brown on cerebral and cerebellar physiology. He returned to Toronto in 1936 to work with McKenzie. Botterell served with the Royal Canadian Army during World War II. He visited Sir Geoffrey Jefferson in Manchester and was likely influenced by Jefferson’s views on intracranial aneurysms. He succeeded McKenzie as head of the section in 1952. There had been a few planned aneurysm operations under McKenzie, but their number increased greatly during Botterell’s tenure.

In a landmark paper in 1956Reference Botterell, Lougheed, Scott and Vandewater 14 and again in 1958,Reference Botterell, Lougheed, Morley and Vandewater 15 Botterell and his associates W.M. Lougheed and T.P. Morley described the first practical gradation of subarachnoid hemorrhage and discussed its relationship to surgical outcome. The Botterell scale consisted of five grades. In addition, these were the world’s first reports of hypothermia, hypotension, and intermittent interruption of the carotid and/or vertebral arteries to improve the results of aneurysm surgery. They also discussed the timing of surgical intervention (early, preferably within a week), the effect of the size and site of the aneurysm, patient age, and the presence of massive intracranial bleeding. Hypothermia to 30ºC by external cooling together with a “lytic cocktail” (meperidine, promethazine, and chlorpromazine) was used without cardiac arrest. They recognized that hypothermia did not eliminate vasospasm but provided major protection from anoxia. Their results also reflected an early “outcome score.” Their experience with this technique began in May of 1954, based on the work of Wilfred Bigelow, a cardiac surgeon at the Toronto General Hospital.

The Hunt and Hess scale (1968), based on 12 years of experience, made further minor modifications, including a grade 0 for an asymptomatic aneurysm. The major prognostic value of the Hunt and Hess scale was that the grading was done just before the operation rather than at the time of presentation. The Hunt and Hess scale gave proper attribution to the Botterell scale, with only minor additions, but surprisingly has relegated the Botterell scale to obscurity.

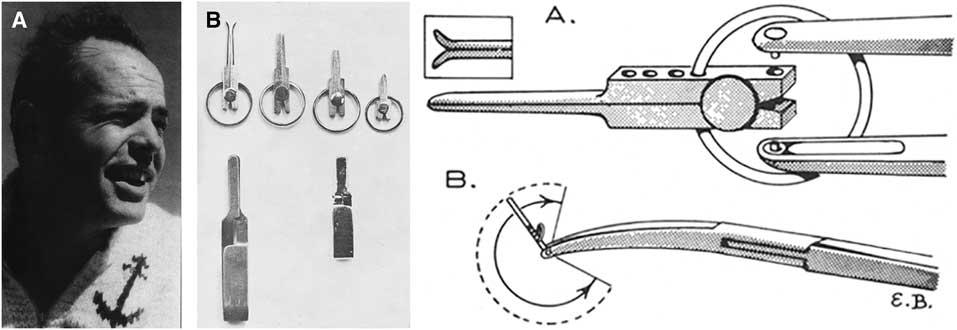

William M. Lougheed (1923–2004, born at Toronto General Hospital, son of a physician practicing in Toronto; MD Toronto, 1947; Figure 2A) began training at the Toronto General Hospital with cardiac surgeons Gordon Murray and Wilfred Bigelow, but he fell under the spell of neurological surgery and learned the craft from McKenzie and Botterell.Reference Findlay 16 It was Bigelow’s investigations into cardiac surgical procedures using hypothermia that intrigued Lougheed about cerebral operations using reversible arrest of circulation and hypothermia. He spent two years in Boston with Dr. William Sweet studying cerebral responses to anoxia under hypothermia.Reference Lougheed and Kahn 17 They found that the dog brain could tolerate cerebral anoxia and a reduced metabolic rate at temperatures of 25ºC for as long as 22 minutes of circulatory arrest. Systemic hypothermia was preferred to cooling only the brain. In 1955, with Drs. Sweet, White, and Brewster, he reported the first two neurosurgical patients ever to be operated on under hypothermia.Reference Lougheed, Sweet, White and Brewster 18 The first was a hemispherectomy for recurrent glioblastoma with temporary occlusion of both common carotid arteries, and the other was for a large arteriovenous malformation, with bilateral carotid and vertebral occlusion. The laboratory and clinical experience then led to the use of these adjuncts in operating on intracranial aneurysms with Botterell after his return to Toronto in 1954. While they showed that complex aneurysms could be operated on with greater facility, outcomes were not necessarily optimal. They also did not provide definitive evidence as to timing of operations, although they preferred early operation based on the Botterell scale. During Lougheed’s stay in Boston in 1953, he assisted Drs. Hamlin and Sweet in operations to reopen occluded or stenosed cervical carotid arteries by end-to-end anastomosis.Reference Hamlin, Sweet and Lougheed 19 The better-known reports of Eastcott, Pickering, and Robb (possibly influenced by C.P. Symonds’ knowledge of the investigations of C.M. Fisher), Cooley, DeBakey, and others spurred the expansion of carotid surgery in the 1950s.

Figure 2 (A) Photograph of Dr. William M. Lougheed, circa 1960. Reproduced with permission from Findlay JM.Reference Findlay 16 (B) Left: Lougheed clip, as designed by Mr. Harry S. Kerr, in several sizes (top row), with the Schwartz clip (lower left) and Mayfield clip (lower right). Right: Drawing of (A) tip of clip holder and the clip; (B) angular rotation of the clip and bifurcated ski-board tips. Reproduced with permission from Lougheed and Khodadad.Reference Lougheed and Khodadad 31

Lougheed amassed a large series of carotid endarterectomies (over a thousand). He established a research laboratory at the Banting Institute and with Dr. Mary I. Tom (neuropathologist at Toronto General Hospital) starting in the mid-1950s, devised a model of subarachnoid hemorrhage by transpalatal injection of blood through a burr hole into the basal cisterns of a dog using a dissecting microscope.Reference Lougheed and Tom 20 Because of difficulty using the operating microscopes of those times (a Zeiss OpMi-1) that had a binocular eyepiece for the operating surgeon but only a monocular eyepiece on a sidebar for the assistant, Lougheed was instrumental in the development of a more maneuverable split-beam “diploscope” by Zeiss, which allowed binocular vision for the assistant directly across from the operating surgeon, making assistance more effective.Reference Lougheed and Marshall 21 He was Canada’s first neurosurgeon to utilize the microscope extensively, and among the world’s first micro-neurosurgeons. He pioneered microsurgical techniques and was in frequent contact with Dr. R.M.P. Donaghy in Burlington, Vermont. Together with G. Khodadad, Lougheed reported on their laboratory experiences in microvascular reconstruction, using contact cement, Teflon grafts, suture and stapling techniques, as well as non-suture anastomosis.Reference Khodadad and Lougheed 22 - Reference Khodadad and Lougheed 24 The non-suture technique consisted of threading the vessels to be anastomosed end-to-end through a cylinder and ring-shaped clip, allowing for intima-to-intima contact without a foreign body in the lumen.Reference Gentili, Lougheed, Yoshijima, Hondo and MacKay 25 A modification of this device also allowed for end-to-side anastomosis. Although many hundreds of these procedures were performed on animal models and on human cadaver vessels, they did not replace microvascular suture anastomosis. Based on this expertise, and on reports of previous middle cerebral artery embolectomy (see Jacobson et al.,Reference Jacobson, Wallman, Schumacher, Flanagan, Suarez and Donaghy 26 Chou,Reference Chou 27 and ScheibertReference Scheibert 28 ), Lougheed reported in 1965 the successful removal of an embolus in the internal carotid artery bifurcation extending into the proximal anterior and middle cerebral arteries.Reference Lougheed, Gunton and Barnett 29 In 1971, he reported the first successful saphenous vein graft from the common carotid to the supra-cavernous internal carotid artery in a woman with a completely occluded cervical internal carotid.Reference Lougheed, Marshall, Hunter, Michel and Sandwith-Smyth 30 He had failed on two previous attempts because of extensive atherosclerosis in the intracranial internal carotid.

Lougheed found that the aneurysm clips available in the early 1960s were not always of the variety, length, and shape he desired. Therefore, with Harry S. Kerr, a Toronto jeweler, he devised a smaller clip with a proximal C-shaped spring inserted into indentations in the hub, allowing rotation of the clip to different angles, and the ability to adjust blade tension by altering the position of the C-spring on the hub (Figure 2B).Reference Lougheed and Khodadad 31 He was among the first to use temporary proximal artery occlusion to assist in clipping aneurysms, and was a proponent of early operation (within 24 hours) in patients with good scores.

Dwight Parkinson (1916–2005, born in Idaho, MD McGill, 1941) trained at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota) and began his career at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg in 1950. Parkinson contributed to the anatomy and treatment of carotid-cavernous fistulae. He published the results of cadaveric dissections of the carotid artery and its branches in the cavernous sinus.Reference Parkinson 32 He asserted that the cavernous sinus was not a simple endothelium-lined cavity like other intracranial venous sinuses, as commonly believed, but a space (lateral sellar compartment) containing a “parasellar venous plexus” encapsulated in dura, which the carotid artery with its periadventitial sympathetic plexus and abducent nerve traversed in association with the oculomotor, trochlear, trigeminal nerves (ophthalmic division), in the roof and lateral wall (illustrations in Pernkopf’s atlas dating back to 1954 had indeed shown a venous plexus surrounding the carotid artery).

He also laid to rest the traditional teaching that there were no branches of the internal carotid artery until it emerged from the cavernous sinus. In 1964, after failure of conventional treatments of traumatic fistula, he directly approached the cavernous carotid artery to obliterate the arteriovenous connection and preserved patency of the internal carotid, under hypothermia and cardiac arrest.Reference Parkinson 33 The approach was through “Parkinson’s triangle” in the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. This was the first reported direct approach into the cavernous sinus and pointed the way for later attacks on intracavernous neoplasms and aneurysms. For the obliteration of arteriovenous malformations, Parkinson developed simultaneous biplane stereoscopic angiography, including its intraoperative use.Reference Parkinson, MacPherson, Childe, Middlecote, Morrow and MacEwan 34 He emphasized clipping the feeding vessels and the draining veins as close to the “fistula” as possible, and excising the malformation completely to prevent recurrent bleeds.Reference Parkinson 35 He described the arterial appearance of the draining veins before general usage of the term “red veins.” He commented on the futility of deep X-ray therapy to obliterate these malformations. According to Yasargil,Reference Yasargil 36 Parkinson had used an operating microscope in the laboratory in the late 1950s.

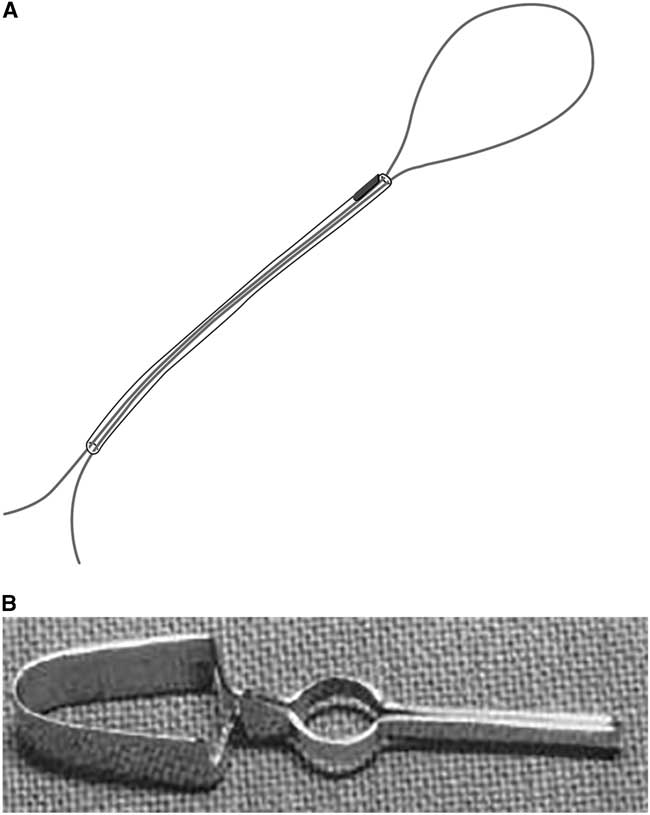

Charles G. Drake (1920–1998, born in Windsor, Ontario, MD Western Ontario, 1944) received his training with McKenzie and Botterell, straying from an initial interest in internal medicine. In 1949, as McKenzie’s resident, he drained an intracerebral hematoma to clip a middle cerebral branch aneurysm on one of Botterell’s patients, following repeated bleeds. In 1951, as a resident, he published a short note on the use of a polyethylene tube attached to the needle for percutaneous carotid angiography, in order to stabilize the needle during contrast injection. Following Drake’s residency, McKenzie arranged for him to visit Jefferson (Manchester), Dott (Edinburgh), Hugh Cairns (Oxford), and Herbert Olivecrona (Stockholm). He conducted research on the “primunculus” in the anterior cerebellum with John Fulton at Yale. McKenzie encouraged Drake to start a neurosurgical service at the University of Western Ontario in London. In early 1959, after cadaveric dissections and with McKenzie’s blessing, he successfully clipped a basilar bifurcation aneurysm.Reference Drake 37 In later discussions on the treatment of giant intracranial aneurysms,Reference Drake 38 Drake described the use of his tourniquet for graduated occlusion of the neck of the aneurysm or the main trunk bearing the aneurysmal sac (Figure 3A). This consisted of a 3-0 polypropylene suture threaded through a fine polyethylene tube brought to the scalp through a separate stab incision. A small clip at the end of the tube marked the position of the distal tube, and after a trial occlusion, the proximal end was buried under the scalp or fascia with another small clip. Because of inadvertent inclusion of vessels in the immediate proximity of the aneurysmal neck, he devised a fenestrated clip (Drake-Kees, modified Mayfield clip) in 1969, which allowed sparing these vessels (Figure 3B). This also allowed him to clip wide-necked aneurysms in tandem fashion. In Del Maestro’s account,Reference Del Maestro 39 Drake had been contemplating how to clip a basilar bifurcation aneurysm in a patient referred by J.L. Poole of New York. After damaging several Mayfield clips in vitro, he telephoned Frank Mayfield in Cincinnati about creating an aperture in the proximal part of the clip to accommodate the posterior cerebral artery. A few days later, three fenestrated clips of varying length fabricated by George Kees Jr. arrived, allowing Drake to successfully clip the aneurysm. Kenichiro Sugita, after Drake demonstrated these clips to him, was able to modify them further in Japan. These clips were subsequently used on aneurysms in various other locations, preserving arteries and nerves in the fenestration.

Figure 3 (A) Artist’s rendering of Drake’s tourniquet (by M. Foldenauer). (B) Photograph of Drake fenestrated clip, also referred to as modified Mayfield clip. Reproduced with permission from Drake CG. Management of aneurysms of posterior circulation. In: Youmans JR (ed.), Neurological Surgery, Vol. 2. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1973: 792.

Dr. Drake was the chairman of a group of six internationally recognized neurosurgeons who established the World Federation of Neurological Surgeons Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Scale in 1988. It was a blend of the previous scales of Botterell, Hunt and Hess, the Glasgow Coma Score (1974), and the Glasgow Outcome Scale (1975). It was intended to be simple, reliable, and designed to estimate patient prognosis, evaluate treatment by various techniques, and quantify neurologic status between bleed, preoperative, and postoperative periods.Reference Drake, Hunt and Kassell 40

Drake also utilized extracorporeal circulation and profound hypothermia to operate on aneurysms.Reference Drake, Barr, Coles and Gergely 41 Initial experience with deep hypothermia (15ºC) and cardiac arrest did not prevent bleeding from the brain, and they were later abandoned for profound hypotension and delayed operation. He stated that the advantages of operating on a soft aneurysm in a dry field with a slack brain prevented many complications. Drake early recognized the need for follow-up arteriography, and together with neuroradiologist J.M. Allcock began to routinely evaluate the degree of postoperative occlusion of the neck and sac of aneurysms and patency of vessels in their proximity.Reference Allcock and Drake 42 This also provided further exploration and study of arterial spasm.Reference Allcock and Drake 43 In their paper of 1965,Reference Allcock and Drake 43 they stated that it might be reasonable to try to maintain blood pressure at or above the patient’s normal range after clipping, to alleviate the effects of vasospasm. Although in 1951 A.E. Ecker and P.A. Riemenschneider had described arterial spasm as a result of subarachnoid hemorrhage,Reference Ecker and Riemenschneider 44 little had been written since. Drake’s contacts as a resident with J. Richardson and H. Hyland,Reference Richardson and Hyland 45 neurologists at Toronto General Hospital who were interested in subarachnoid bleeding (but more in medical management than in surgical intervention), later marked his association with neurologist Henry Barnett in establishing a combined neurosciences unit at the University of Western Ontario. Drake’s juniors—Gary Ferguson (1941–2011, MD Western Ontario, 1965) and Sidney Peerless (1936–, MD University of British Columbia, 1961)—further explored the use of various extracranial to intracranial anastomoses for vascular disease, even dementia. In 1985, an international study group effectively dismissed the value of this procedure for ischemic disease, although there can be no doubt of the value in selected instances of cerebral ischemia and planned occlusion of cerebral vessels for vascular or neoplastic disorders. London (Ontario) became an internationally renowned center for neurovascular surgery. Drake’s associates, Sidney Peerless and Gary Ferguson, succeeded him as chief of neurosurgery in London. Ferguson remained there. Peerless trained in Toronto with T. Morley and W.M. Lougheed, came to London after a fellowship in Zurich with Yasargil, and later moved to Miami. With Neal Kassell, he was a principal author of a paperReference Kassell, Peerless, Durward, Beck, Drake and Adams 46 on the largest series of patients treated for vasospasm using volume expansion and induced hypertension. Peerless, working in Vancouver, was reported to have performed the first EC–IC bypass in Western Canada.

After World War II, C. Miller Fisher (1913–2012, born in Waterloo, Ontario, MD Toronto, 1938), began a rotation at the Montreal Neurologic Institute, coming to the attention of Wilder Penfield. Fisher spent 1948 to 1950 as a fellow there, and a year at Boston City Hospital with Raymond Adams. He was the neuropathologist at Montreal General Hospital from 1950 to 1954. He performed more than a thousand autopsies and explored the cervical carotid and intracranial arteries. Arteriography for stroke had been abandoned for a few years in Montreal after serious side effects following use of Thorotrast.Reference Estol 47 He subsequently went to Boston and performed another thousand or more autopsies. Fisher’s studies led to the recognition of transient monocular blindness (he preferred this term to amaurosis fugax), transient ischemic attacks, embolism from atrial fibrillation to the intracranial vessels as different from occlusion from atherosclerosis-related thrombosis, and cervical carotid occlusion from plaques, and dissection, associated with various cerebrovascular syndromes. He also investigated the role of anticoagulants as treatment as well as the association of hypertension and atherosclerosis in cerebrovascular disease. These studies resulted in banishing so-called “vasospasm” as a cause of these ischemic episodes and its treatment by sympathectomy. In 1951,Reference Fisher 48 Fisher stated, “Someday vascular surgery will find a way to bypass the occluded portion of the artery during the period of ominous fleeting symptoms. Anastomosis of the external carotid artery or one of its branches with the internal carotid artery above the area of narrowing should be feasible.” He further stated that “the carotid plaque, because of its strictly focal extent, should be amenable to a surgical bypass procedure.” On the basis of that article, Carrea et al.Reference Carrea, Molins and Murphy 49 in Buenos Aires performed end-to-end anastomosis of the internal to the external carotid artery in 1951, with a report in 1955. Fisher also described the “string sign” on cerebral arteriography and the subclavian steal syndrome. In a paper in 1980,Reference Fisher, Kistler and Davis 50 he explored the relationship of cerebral vasospasm to the thickness and location of subarachnoid blood on a CT scan, also intraventricular and intraparenchymal blood. The severity of vasospasm and the resulting ischemic deficits correlated with the thickness of subarachnoid blood, and when clots were localized in the region of a given artery with deficits related to the distribution of that artery.

Henry J. M. Barnett (1922–2016), born in Newcastle on Tyne, coincidentally in the same year and town as another neurologist (John Walton, who published a book on subarachnoid hemorrhage and aneurysms), graduated from Toronto in 1944 and trained in Toronto and in England, at Oxford and at Queen’s Square, encountering Hugh Cairns in Oxford and Charles Symonds in London. He spent 1952 to 1969 in Toronto. In 1973 he wrote a monograph on syringomyelia, and particularly from trauma, before the advent of MRI. He was closely associated with Drake, first in Toronto and from 1969 in London, Ontario. There, he and Drake worked at Victoria Hospital and in 1969 cofounded the first multidisciplinary neurosciences unit at the University of Western Ontario. He succeeded Drake as chairman of the combined department from 1974 to 1986. Almost a hundred years after Osler’s discovery of platelets, his research proved the benefit of aspirin in stroke compared to other antiplatelet agents, especially in males. 51 In later writings, he indicated that females would also benefit from aspirin. He explored the value of endarterectomy in carotid stenosisReference Morgenstern, Fox, Sharpe, Eliasziw, Barnett and Grotta 52 , Reference HJM and Taylor 53 based on a consistent classification of stenosis (North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial). He and neuroradiologist Allan Fox showed that the preventative effects of endarterectomy were apparent for stenosis of 70% or more, and also in “moderate” stenosis with multiple other risk factors. Symptomatic patients over 75 years of age, with hemispheric symptoms, not just amaurosis, and good collateral circulation were also suitable candidates. Together with Peerless, he wrote on nine patients who developed strokes after uneventful cervical internal carotid occlusion, from turbulent flow in the internal carotid stump releasing emboli into the external carotid and its collaterals feeding the intracranial internal carotid, or perhaps emboli from common carotid or external carotid plaques.Reference Barnett, Peerless and Kaufmann 54 In an international multicentre study, 55 and in another paper with Fox, Peerless, and V. Hachinski,Reference Barnett, Fox and Hachinski 56 they demonstrated the failure of external-to-internal carotid bypass procedures to reduce the risk of ischemic strokes and decrease dementia. Barnett also investigated cerebrovascular accidents from emboli in mitral valve prolapse, and wrote on cerebral venous thrombosis and cranial nerve palsies related to aneurysms. In a paper with Lougheed,Reference Barnett, Wortzman, Gladstone and Lougheed 57 he described “external carotid steal” from the internal or vertebral arteries as causing cerebral ischemic events.

John Allcock (1920–2001) was born in Sheffield, England, and graduated from the Medical School at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, England, in 1942. He became a neuroradiologist in London, Ontario, in 1960, retiring in 1978. With Drake, he played a major role in expanding angiography both pre- and postoperatively in order to explore the completeness of aneurysm clipping and, in particular, vasospasm. He is said to have suggested the idea of the (Drake) tourniquet to determine the feasibility of proximal arterial occlusion in aneurysms. Toward the end of his career in London, Ontario, he encouraged endovascular techniques in cerebrovascular disease, and was responsible for recruiting Gerard Debrun (from 1978 to 1981) and Fernando Vinuela (resident and fellow 1974–1979, then faculty from 1980 to 1986). Both worked extensively in balloon occlusion of aneurysms and fistulae, and in embolizing arteriovenous malformations before moving elsewhere.

Allan J. Fox graduated from McGill in 1970 and joined Allcock in 1976. He played a large role in the indications for operating on carotid occlusion and endovascular treatment of aneurysms. As part of the NASCET study, with Barnett, he defined the degrees of internal carotid stenosis, stratifying which groups were more likely to benefit from endarterectomy.Reference Fox 58 He wrote on operating as opposed to stenting and angioplasty for carotid stenosis. He and Barnett described “near occlusion” of the internal carotid and the “string” sign with regard to risk of ischemic events. He also had a prominent role in the IC–EC bypass study.

Arterial vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage has been extensively investigated and written about by Bryce K.A. Weir (1936–, born in Edinburgh, Scotland, MD McGill University, 1960), R. Loch McDonald (MD University of British Columbia, 1985; residency in Toronto, then with Weir in Edmonton), and J. Max Findlay (University of Toronto, trained with A. Hudson, T. Morley, and W.M. Lougheed, and then Weir). Weir trained at the Montreal Neurologic Institute and also in New York. He and his trainees, McDonald and Findlay, have written extensively on the mechanisms of vasospasm.Reference Macdonald and Weir 59 , Reference Weir 60 At the University of Alberta, Weir produced a consistent model of subarachnoid hemorrhage in cynomolgus monkeys and evaluated the effects of nimodipineReference Espinosa, Weir, Boisvert, Overton and Castor 61 - Reference Weir 64 and intracisternal recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) to reduce vasospasm by lysis of subarachnoid blood. They investigated numerous substances in cerebrospinal fluid released by hemolysis of erythrocytes and felt that oxyhemoglobin was the most likely spasmogen.Reference Espinosa, Weir, Shnitka, Overton and Boisvert 63 Impairment of cerebrovascular innervation was not thought to play a significant role.Reference Macdonald and Weir 65 Their histological studies indicated that vasoconstriction seen in vasospasm results in secondary smooth muscle damage, with subsequent migration of smooth muscle cells into the intima, and ultimately their proliferation. They believed that vasospasm abated after radiologic spasm due to longstanding smooth muscle constriction, not vessel wall thickening. In clinical trials,Reference Findlay, Macdonald and Weir 66 they found that rtPA did reduce the clinical effects of vasospasm in 19 of 20 patients. There was one case of extradural hemorrhage (probably unrelated), and one patient died from symptomatic vasospasm after failure to adequately lyse the subarachnoid clot. They evaluated the benefits of using tirilazad (a 21-aminosteroid that inhibits lipid peroxidation), which produced better results in the model than in patients. They showed that the removal of subarachnoid clots by lysis or mechanical removal had its best results when utilized within 48 to 72 hours after the bleed. Chemical clot lysis was preferable to mechanically suctioning clots due to the risk of small vessel injury in the latter procedure. They tried the use of intraventricular rtPA. WeirReference Weir 67 , Reference Weir, Grace, Hansen and Rothberg 68 explored the time course of vasospasm related to the bleed. Subsequent papers discussed the role of nimodipine and rtPA in treatment of vasospasm. There was clinical improvement, even if angiographic vasospasm was not reversed or prevented. McDonald et al.Reference Foroohar, Macdonald, Roth, Stoodley and Weir 69 in 2000 analyzed various factors associated with outcome after operation, and concluded that better results were obtained with smaller drops in systolic and mean arterial pressures during the operation compared to preoperative levels in ruptured aneurysms, and a higher intraoperative diastolic pressure in unruptured aneurysms. Younger age and better Hunt/Hess and Fisher scale scores were major factors for better results, but hypothermia did not make much difference. On the other hand, Farrar et al.Reference Farrar, Gamache, Ferguson, Barker, Varkey and Drake 70 from Drake’s group induced reduction of mean arterial pressure to 30–40 mm for brief periods and found this to be well-tolerated. McDonald and colleagues in 2001 reported on the successful use of rtPA and heparin by local infusion to treat thrombosis of the superior and inferior sagittal, straight, and both transverse sinuses, and the vein of Galen and internal cerebral veins by transfemoral catheterization in a 34-year-old man.Reference Yamini, Loch Macdonald and Rosenblum 71 The patient had an uneventful recovery. Interestingly, both Weir and later McDonald were chairmen of neurosurgery at the University of Chicago and Findlay for a short time in London, Ontario, and then Edmonton.

One cannot forget the efforts of neurologists Herbert Hyland and John C. Richardson of Toronto, who were encouraged by McKenzie to investigate subarachnoid hemorrhage and intracranial aneurysms, resulting in a paper in 1941.Reference Richardson and Hyland 45 Canada’s first neuroradiologist, Arthur E. Childe of Montreal and later Winnipeg, encouraged these endeavors. In 1969, W.G. Beattie published a comprehensive review of Canadian contributions to microvascular surgery.Reference Beattie 72

Conclusions

Canada, with its relatively small population, has been exceptional in the range of its contributions to cerebrovascular neurosurgery: from the autopsy and clinical studies of Osler, Fisher, and Barnett; the “minimal” treatment of vascular disease with aspirin; the unprecedented exploits of the neurosurgeons from loupes to the operating microscope; and then to less invasive endovascular therapies by interventional neuroradiologists collaborating with neurosurgeons. One of the most noteworthy achievements was the binding together of the diverse neuroscience specialties into a combined department in London. It has been a remarkable journey of a hundred years and more.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the support of Dr. Stephen Lownie of Western University, London, Ontario, in reviewing this article, and to thank Tom Cichonski for editorial assistance and Megan Foldenauer for her illustration.

Disclosures

The authors of this manuscript certify that this manuscript, or any similar manuscript, has not been published previously in whole or in part, and is not under consideration elsewhere. The authors further certify that this manuscript is a unique submission and is not being considered for publication by any other source in any medium.

The author has no conflicts of interest to report, and there were no financial associations with any of the drugs, materials, or devices mentioned in this manuscript.

Statement of Authorship

As principal author, Dr. Ramnath made all substantial, direct, intellectual contributions to the work, in collaboration with Dr. Lownie.