Introduction

The term ubāna tarāṣu (to extend the finger and point) is the idiom commonly used by scholars to describe a specific gesture depicted in many second and first-millennium Assyrian visual representations, most of which portray the Assyrian king. Footnote 1 The depicted gesture involves the right hand raised at a level roughly between the chin and nose of the performer and held rounded in a fist except for the extended index finger. The linguistic identity of this visual expression was proposed at the beginning of the last century and, because of the analogy of the raised right hand attested in texts during prayers, it was initially interpreted as a gesture of prayer.Footnote 2 This textual approach was later dismissed and attempts to understand its meaning were built on visual evidence only. This led to a variety of interpretations: was the gesture a blessing, kissing, finger-snap, a command, a manner of speech, or a sign of divine recognition of one’s dominion? These readings were thoroughly discussed and questioned by Ursula Magen (Reference Magen1986: 53), who resumed the textual lens to unveil the significance of the pointing finger gesture. Building on Kassite, Middle-Assyrian, Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian written sources, Magen argued that the interpretation of the ubāna tarāṣu as a gesture of prayer stricto sensu cannot be sustained and that most of the texts indicate, rather, the meaning of either a healing or ominous gesture. Combining these sources with visual evidence depicting the Assyrian king pointing his finger at divine symbols, she identified the gesture with the linguistic expression ubāna tarāṣu and argued that it stands for a “gesture of speech” (“Sprechgestus”) in a positive communication between man and deity, where the latter is asked by the king for an answer, which in some cases is expected in a kind of oracle (egerrû) expressing the positive or negative will of the gods.Footnote 3

Magen offered a very compelling argument for the ubāna tarāṣu gesture and, to date, it represents the most exhaustive interpretation, covering a broad array of both textual and visual occurrences. Her reading was therefore taken as valid by later scholars and recent contributions dealing with the depiction of the pointing finger gesture largely adopt her view.Footnote 4 At the same time, a general ambiguity in scholarship still persists, the gesture being inconsistently regarded as a visual expression of homage, prayer, or adoration.Footnote 5

The ambiguity is further increased by the fact that Assyrian texts do not explicitly define the gesture when they describe the erected monuments bearing an image of the king pointing the finger. Compared to the well-known idiom appa labānu (“to stroke the nose”), which is used to describe the image of the Assyrian king touching his nose or placing his hand directly in front of the face, the pointing of the finger is never labelled as ubāna tarāṣu.Footnote 6 Further to this, Assyrian royal inscriptions seldom provide ekphrastic descriptions of monuments and, beyond those explicitly stating that the king is depicted touching his nose, the image of the king is said to have been crafted in the stance of supplicant (musappû) with reference to steles (narû),Footnote 7 or in order to constantly ask requests (mūterrišu) for the sake of his life, mainly with reference to statues.Footnote 8 These incidents should be conceived as textual references to the royal image rather than to the actual stance or gestures performed by the king.

The absence of specific labels used by scribes to define such a widespread gesture is rather surprising, since Assyrians were keen to describe behavioral stances and gestures. A good example of this is the appa labānu.Footnote 9 Also, the textual sources collected by Magen include many kinds of witchcraft and incantations for either auspicious and inauspicious purposes and do not highlight a specific meaning intrinsic to the pointing of the finger.Footnote 10 In fact, the linguistic expression is embedded within a context concerning fortune or misfortune but does not appear as an essential gesture for their performance. In other words, the pointing finger appears to be a more simple deictic gesture than a gestural tool carrying powerful effects on something or someone.

Taking the gesture as a simple deictic device, I would like to consider this widespread Assyrian visual motif by analyzing all the attestations available, with a special focus on rock reliefs and steles of the second and first millennium BCE. I will also give special attention to those where text and image are preserved and clearly legible.Footnote 11

Deictic Gestures

Irrespective of the significance that texts or scholars may attach to it, the pointing finger is a gesture. A gesture can be described in many ways, but its basic meaning is a movement or set of movements of body parts, especially the arms, the hands or the head, that partakes “of these features of manifest deliberate expressiveness to the fullest extent”.Footnote 12 A gesture is intentionally communicative, and it may or may not convey meaning. Discovering a gesture’s meaning is not as simple as one may expect: gestural behavior is not to be considered as innate, but a product of human culture and thus varies according to the social and cultural context that has produced it. This implies that there is not always a universality of gestures. At the same time, some gestures can be thought to be somewhat universal because they acquired symbolic connotations throughout their social history and thus do have a cross-cultural extension.Footnote 13 In an attempt to avoid any biased approach, in this discussion the pointing finger is analyzed without any concealed meanings and values being taken into account but identifying its functional tasks. A gesture is indeed intrinsically functional before it is intrinsically meaningful.

The pointing finger, subsumed within the category of deictic gestures, is therefore a gesture that has the function of pointing at something or someone. In short, it has a target. “Pointing is pointing”, Bühler (Reference Bühler2011: 102) states, “and never anything more, whether I do it mutely with my finger or doubly with finger and a sound to accompany the gesture”. In order to express communication essentially and immediately, pointing was defined as the “foundational building block of human communication”, being ubiquitous, a uniquely human behavior, a versatile communicative device, and able to create further types of signs.Footnote 14 Deictic gestures are performed to direct a recipient’s attention towards a specific referent in one’s environment (whether close or further away). The target is concrete and most pointing gestures therefore indicate a space or location, an object or a person that is currently visible or a direction toward a real entity that is not yet visible. Scholars have distinguished between three subcategories of deictic gestures: 1) specific deictic gestures, when the performer points at one particular object with the purpose of referring to this particular object; 2) generic deictic gestures, when the performer points at an object to evoke the whole class of items the object belongs to; and 3) deictic gestures referring to the function of the object, when the performer draws attention to the function of the object being pointed at.Footnote 15 All these three subcategories do not have any intrinsic content, but help us to interpret the situation within which the deictic gesture is produced. In this regard, the act of pointing must be also seen as a situated interactive activity that contains at least two participants, one of whom is trying to establish a particular space as a shared focus for the organization of cognition and action. Within such a field, there must therefore be a body visibly performing an act of pointing; a concrete entity that is the target of the point; the orientation of relevant participants toward both each other and the target that is the locus of the point; and the larger activity within which the act of pointing is embedded.Footnote 16 In addition to these elements, one must also consider that the pointing gesture fulfils an important supportive role in bringing about communication when it is accompanied by a gaze, both of the viewer and of the performer. Deictic gestures help viewers to identify the target by guiding their gaze to its region, helping to establish a joint focus of attention between performer and viewer.Footnote 17 Thus, as the performer’s hand moves up and unfolds into an extended pointing gesture, he/she attracts the viewer’s gaze and brings it in line with the arrow created by the performer’s arm and the pointing finger. At the same time, the performer’s gaze may follow the target he/she is pointing at, so that the gaze and gesture work in tandem to highlight the pointed target. In short, the viewer’s attention is caught not only by the pointing finger but also by the performer’s gaze if this is in line with the gesture. Such a joint communicative act shifts the viewer’s gaze from the gesture and the performer to the concrete entity “to be looked at”.Footnote 18

Having set out these theoretical premises, the obvious questions are: on Assyrian monuments, what is the performer of the gesture pointing at with his finger and gaze? Is it possible to identify the target that the performer wants the viewer to look at? The survey conducted on all the well-preserved monuments, most of which are steles and rock reliefs, allows three groups of targets to be distinguished, depending on their physical locations: textual, if the pointed object is within the text; contextual, if the pointed object is outside the monument (landscape or physical object); and iconographic, if the pointed object is within the image. The discussion will proceed on the basis of both a quantitative and a qualitative analysis.

Textual Target

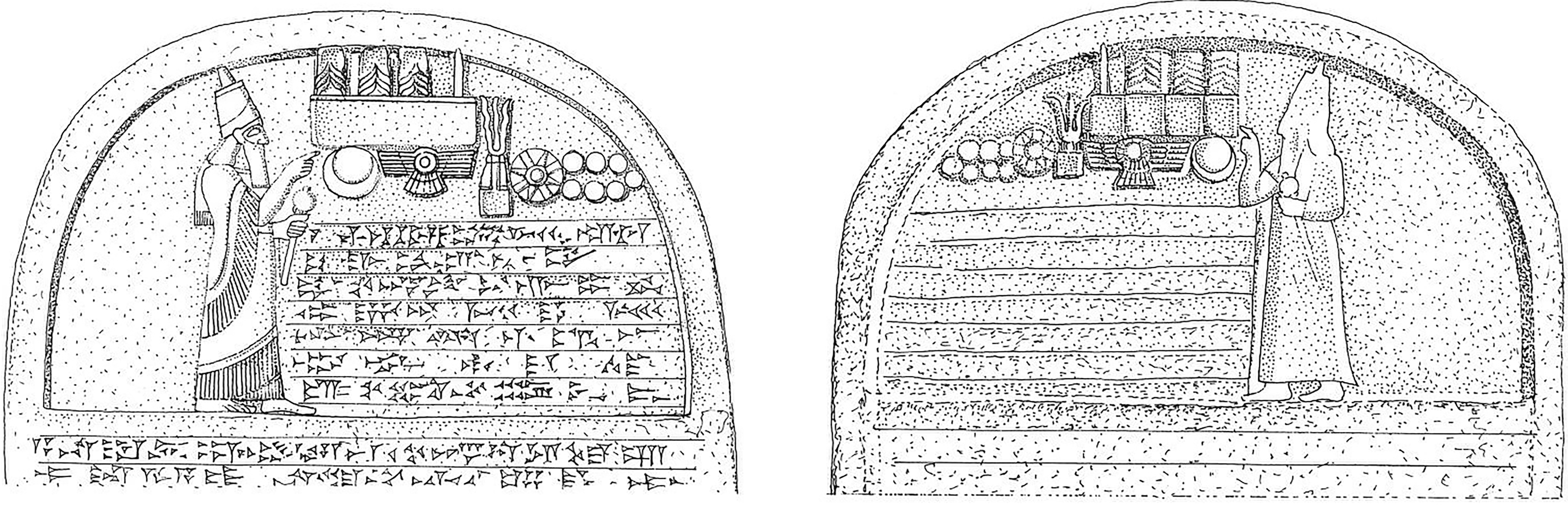

To begin with, images and inscriptions carved by Tiglath-pileser I (1114–1076) and Shalmaneser III (858–824) on the cave walls of the Dibni Su springs at the site of Birkleyn in Eastern Turkey, which are known as the “Source of the Tigris” monuments and labelled Tigris 1 to 5, present some compelling examples of textual targets.Footnote 19 Two rock reliefs are located at the exit of the river tunnel, on the rock face to the right of the river, seen in the direction of flow. This means that both kings stand to the left, looking out of the cave in the direction of the river’s flow. Or, in other words, both confront a visitor who is following the river against the current towards the cave. The inscription is to the left of the relief, so that the kings face the text. Irrespective of the stylistic features of each royal portrait, on which other scholars have already commented, in both the Assyrian king holds a mace in his left hand and makes a pointing gesture with his raised right hand.Footnote 20 To my knowledge, Börker-Klähn (Reference Börker-Klähn1982: 177–178) was the only scholar who noted that Tiglath-pileser I seems to point at the inscription. More interestingly, on closer inspection, both kings use their pointing finger and their gaze to draw the viewer’s attention to specific and paramount information within the text, which either identifies or qualifies the king. In particular, Tiglath-pileser I (Fig. 1, Tigris 1, above) points at the two lines (four and five) which identify the owner of the work.Footnote 21 Shalmaneser III’s gaze and hand point respectively at the first and second line of the inscription (Fig. 1, Tigris 2, below), which contain the name of the king and qualify him as the great king and the strong king.

Fig. 1. Tiglath-pileser I and Shalmaneser III’s rock reliefs (Schachner Reference Schachner2009: figs. 184 and 189)

On a huge stele of Ashurnasirpal II from Kalhu (Fig. 2), sometimes called the “Nimrud Monolith” or “Great Monolith”, the king’s figure stands in front of the divine symbols and the text is engraved on all sides of the monument and the obverse. The text begins with an invocation of various deities and a lengthy passage consisting of the royal name and epithets of the king. Then it proceeds with a description of the first five campaigns.Footnote 22 The king is apparently pointing his finger at the divine symbols. However, a closer look reveals that Ashurnasirpal II is pointing at two brief phrases in two different lines (sixteen and seventeen) that draw the reader’s attention to the king as a weapon of the gods and the gods as helpers of the king.

Fig. 2. Detail of the stele of Ashurnasirpal II (© The Trustees of the British Museum; Museum number 118805)

Another link between the pointing finger and text is found on the rock relief of Shalmaneser III, located on the west bank of the Euphrates near the Kenk Gorge (Kenk Boğazı), north-east of Gaziantep (Fig. 3). In this example, the king points at two phrases in two different lines (four and five) that contain two geographical references: the sea, which is part of a description of the territorial extension of Shalmaneser III’s conquests, and the land of Suhme. If one wants to include the gaze, then the king looks at his royal titles (line three).Footnote 23

Fig. 3. Kenk Gorge rock relief of Shalmaneser III (Taşyürek Reference Taşyürek1979: fig. 1)

The stele of Shamshi-Adad V (823–811) from Kalhu is another example. The royal image occupies the whole front face, and the text is inscribed on the two sides and the rear.Footnote 24 Looking at the stele, the inscription begins on the right side, then moves to the back, and ends on the left side. The stele was discovered in the Nabu temple, although it had probably been moved from the Ninurta temple, since it is dedicated to Ninurta. The forefinger of the king points at two lines (fourteen and fifteen) of column iv, which mention the conquest of some cities as targets of his Babylonian campaign, the most significant military venture of Shamshi-Adad’s career.Footnote 25

Because of its fragmentary status, the link is less certain between the pointing finger gesture of Tiglath-pileser III (744–727) on the rock relief of Mila Mergi, Iraq, and the inscription. The right hand of the king is entirely destroyed. According to Postgate (Reference Postgate1973: 50), who prepared the published copy of the inscription and image from the original, photographs, and squeezes, “it seems as though he may have had two fingers pointing directly upward, with the remaining fingers and thumb clasped round their base, but it is equally possible that this is deceptive, and that one or more of the fingers is pointing forwards, as for example the Tell Abta stele”. From a more recent picture of the relief, the forefinger appears slightly bent.Footnote 26 Combining the first drawing and the recent photos, it seems that the forefinger is specifically pointing at line eight, where the word LUGAL (MAN, šarru) was restored. If this reading is correct, Tiglath-pileser is highlighting his own role as the king of Assyria. It might also be possible that he is pointing at the whole sentence where the word LUGAL is included, which states that “[the goddess Ištar], lady of battle (and) war, the lady who loves [the king, her] favor[ite], the one who subdues recalcitr[ant (adversaries)” (RINAP 1 37: 8). However, the poorly preserved right hand limits our ability to draw further conclusions and leaves much room for speculation.

Another partially fragmentary example is the stele of Sargon II (721–705), found to the west of the old harbor of Kition on the southern coast of Cyprus. The monument shows the king Sargon in profile, who holds a mace in his left hand and raises his right hand, apparently pointing his finger. He is depicted as looking at eight symbols to his right representing Assyrian gods. The inscription on the front is an invocation of the very same deities. However, the king does not point his finger at the divine symbols but at the right side of the stele, the one that contained column ii. Rather than pointing at a specific word or phrase, here it seems that the whole column ii is the real target of the pointing finger. This would not seem a random choice, since column ii is the part of the inscription which indicates the identity of the king who erected the stele and describes his most significant political and military achievements.Footnote 27

A specific deictic gesture is performed by Sennacherib (704–681) on the series of rock reliefs carved on the face of Judi Dagh (called Nipur in Akkadian) in eastern Anatolia near the Tigris River (Fig. 4). Here, Leonard W. King found eight sculpted panels, six of which have inscriptions and carved figures of the king (labelled as nos. I, II, III, IV, V, VII by King), and the remaining two of which were smoothed in preparation for engraving but were left unfinished (nos. VI and VIII). Of the six panels, the king usually faces the inscription, except for Panel III, where the king turns his back to the main body of the text. The position of the royal image in relation to the inscription varies: on Panels II, IV, V it is to the right of the panel and faces to the left; on Panel I, it is to the left of the panel and faces to the right; and on Panel VII it is carved in the centre of the panel with the inscription, much defaced, engraved on each side of the king.Footnote 28 In the case of Panels I, II, IV, and V, the image and text are both preserved. In these cases the figure is making the gesture performed by the Assyrian king, which is clearly the pointing finger, and interestingly he also specifies the line of the text which the gesture points at.Footnote 29 Specifically, on Panel I, the king points at line four (reference to divine support) of the text, although it must be said that in this case King (Reference King1913: 78) states that the inscription begins “on a level with the king’s forehead, his thumb pointing to l. 4 of the text”. Since this is an awkward gesture, for the gesture was always performed with the forefinger, it is likely that King confused thumb and forefinger and erroneously described the gesture. On Panel II, the king points at line twelve (list of disobedient lands), and on Panels IV and V, he points at line one (list of deities).Footnote 30

Fig. 4. Details of the Judi Dagh reliefs of Sennacherib (King Reference King1913: pls. XII, XV, XXII, XXVI)

Contextual Target

A remarkable example of this category is the stele of Adad-nirari III (810–783), erected on his behalf by his official Nergal-eresh (Fig. 5). The stele was found in the shrine of a temple at Tell al-Rimah, Iraq, standing beside the podium in the cella, with its face flush with the front of the podium. The king stands facing right towards the podium with his right hand raised and his forefinger pointing. In the field on either side of the king’s head is a series of eight divine symbols. The inscription is carved just below the king’s belt. The inscription opens with a dedication to the god Adad, suggesting that the monument was dedicated to him.Footnote 31 Notably, the king does not point his finger either at the divine symbols or at the text, but rather at a target outside the stele. The most likely target is the divine statue that once stood on the podium to the right of the stele. According to the excavation report, it is not certain that this was the original position of the stele. However, if the stele was in situ, then the temple was dedicated to Adad and the statue on the podium could represent Adad. This would imply that the king pointed his finger at the divine statue. In addition, the divine symbol located just above the pointing finger is that of Adad, represented in the form of a lightning fork and mounted on a two-stepped pedestal.

Fig. 5. Stele of Adad-nirari III from Tell al-Rimah (left; photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed), stele in situ (right; Oates Reference Oates1967: pl. XXXIIa)

A very similar example is a fragmentary stele of Adad-nirari III from Tell Sheikh Hamad (Dur-Katlimmu, Syria) dedicated by Nergal-eresh.Footnote 32 The king stands in front of the divine symbols and points his finger, but neither at the divine symbols nor at the carved inscription. The exact findspot of the stele fragments is not certain. However, the inscription inscribed on the left side of the stele states that the monument was dedicated to the god Salmanu. Since the Tell al-Rimah stele was found in situ inside the cella of the temple and beside the podium that once held the statue of the god, it is possible that the Tell Sheikh Hamad stele was set up in a similar position inside the Salmanu temple.Footnote 33 This interpretation is supported by the curse formulae at the end of the inscription and addressed to whoever “discards this image from the presence of Salmanu (or puts it into another place)” (Radner Reference Radner2012: 273). This textual reference suggests that the finger of the king was originally pointed at the statue of the deity that once sat on the podium.

Along the same lines is the stele of Mushezib-Shamash, governor and builder of a fortified city who erected a stele, now fragmentary, which was found near Urfa in southern Anatolia and that can be dated to around the 8th century BCE.Footnote 34 The image carved on it shows a figure in relief, turned to the left, who performs the pointing gesture.Footnote 35 The inscription engraved on the monument states that the monument was erected by Mushezib-Shamash for his own life and placed in front of Adad.Footnote 36 The stele was found in a village (Anaz) and its original location remains uncertain. However, based on the previous examples, it seems likely that the monument was erected within a temple, perhaps dedicated to Adad, and placed next to the statue of the god.

Within this category, the three rounded-topped stone steles found at Nineveh and erected by Sennacherib on the creation of a royal road represent another good example (Fig. 6). Both the text and the image are virtually identical on each stele: the king stands in front of a set of divine symbols with his right hand performing the pointing gesture and holds a mace in his left hand. The inscription begins just below the divine symbols and the king’s body and covers the front face of the monuments.Footnote 37 The king’s finger is apparently pointed at the deities. However, the inscription does not refer to any specific deity to whom the steles are dedicated, nor do the number of divine symbols depicted correspond to the number of deities mentioned in the text. Instead, the central topic of the inscription concerns the creation of a royal road by means of widening existing streets and by erecting steles as boundary markers on both sides of the road. This indicates that the reason for the erection of the steles is not the celebration of a deity but of a royal road. It is therefore likely that the king is pointing at the royal road rather than at the divine symbols. In fact, Sennacherib states that he erected the steles “on each side, opposite one another” (RINAP 3/1 38: 19b–21) and for this reason it is interesting that the king looks in different directions depending on whether the stele was on one side or on the other.

Fig. 6. Examples 1 and 2 of Sennacherib’s steles (Börker-Klähn Reference Börker-Klähn1982: figs. 203–204)

Finally, I will tentatively include in this category one of the “Source of the Tigris” monuments left by Shalmaneser III. Beyond the rock relief already discussed (see above), Shalmaneser III crafted another rock relief with an inscription (Tigris 4) at the entrance of a second cave, on the rock face to the right. Although the one royal portrait does not differ from the others, here the king turns to the left and thus looks into the cave rather than at the person entering. In addition, the king remarkably turns his back to the inscription.Footnote 38 Schachner (Reference Schachner2009: 189, 210) explained this oddity by supposing that the inscription was added later than the relief, since the first cuneiform characters overlap with the figure. Without doubt, this is one possible reason and perhaps the most likely one. At the same time, if one relies on the pointing finger gesture and the examples analyzed so far, it is not too far-fetched to believe that the king was deliberately carved to the left of the inscription in order to draw attention to the interior of the cave, so as to point out that he was able to enter inaccessible rivers and mountains which led to the making of a monument there. This would reflect what the inscriptions (Tigris 2 and 4) state: “Kühner, schonungsloser König, der mit der Waffe tötet, der seine Feinde verfolgt und unzugängliche Flüsse und Berge wie Ruinenhügel der Sturzflut gebieterisch betritt” (Schachner Reference Schachner2009: 191). On this basis, the king is literally pointing at the place, and thus at the physical context, which he was able to reach.

Iconographic Target

A first example that fits this category is a stele from Saba’a, south of the Jebel Sinjar, Iraq, dedicated by Nergal-eresh on behalf of Adad-nirari III (Fig. 7). The royal portrait and divine symbols are on the top part of the stele while the text is inscribed below. Although surrounded by divine symbols in the front and above, the king is pointing specifically at the symbol of Adad only. This is in line with the inscription, which opens with a long dedication to the god Adad.Footnote 39 This implies that the royal image is aimed at drawing the attention to the god to whom the monument is dedicated.Footnote 40

Fig. 7. Adad-nirari III’s stele from Saba’a (photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed)

A similar example is a stele discovered at Tell Abta, a site on the Wadi Tharthar in Iraq. The stele was erected by Bel-Harran-beli-usur, a palace herald active under Shalmaneser IV (782–773) and Tiglath-pileser III.Footnote 41 The left side of the stele is occupied by the divine symbols on the top and the inscription below. To the right stands the portrait of the official who faces left and points with his raised right hand at the divine symbols (Fig. 8). The target of the deictic gesture are the divine symbols. This is consistent with the inscription, which points out that “these mighty lords gave me instructions and at their exalted command and with their firm assent I set out to build a city in the desert” (RIMA 3 A.0.105.2: 10–11).

Fig. 8. Stele of Bel-Harran-beli-usur (photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed)

These two examples shed light on the rationale lying behind a monument where the pointing finger gesture makes its first appearance, the so-called altar of Tukulti-Ninurta I (1233–1197) (Fig. 9). This cult pedestal, along with two other altars, was found in a room of the Ishtar Temple at Assur.Footnote 42 On one side of the pedestal, the figure of the king appears to be shown twice, first approaching and then kneeling in front of a monument, which is a representation of the very same object on which it is carved. On top of this pedestal in the representation stands a rectangular object with what appears to be a vertical stick placed at its centre. The objects on the pedestal have been interpreted as either a tablet and a stylus or the door of a temple, although Bahrani (Reference Bahrani2003: 185–201) has convincingly argued that both may stand for Nusku and his role as dream-bearer. This suggests that what is represented on the altar and what once sat on the real altar was a representation of the god Nusku. The king performs the same gesture in both moments, and his finger is pointed at the altar in both cases. This complies with the prayer engraved on the monument, which focuses on the altar and the god Nusku: “Cult platform of the god Nusku, chief vizier of Ekur, bearer of the just sceptre, courtier of the gods Aššur and Enlil, who daily repeats the prayers of Tukulti-Ninurta” (RIMA 1 A.0.78.27: 1–3).

Fig. 9. Altar of Tukulti-Ninurta I (cdli.ox.ac.uk)

The same rationale probably lies behind one of the so-called Karabur reliefs, located to the southeast of Antakya, and the worn Kurkh Monoliths of Ashurnasirpal II and Shalmaneser III. On the Karabur relief, the god occupies the entire height of the niche and faces right confronting a beardless human figure, probably depicting an Assyrian governor. The latter’s right hand is raised in blessing and in the left hand he holds a lotus-flower. The figure of the Assyrian governor is much shorter than that of the god and stands on a raised platform facing to the left and performing the finger-pointing gesture with his raised right hand.Footnote 43 In the absence of an inscription and relying on the above-discussed examples, one may surmise that the target of the gesture is the deity at whom the beardless figure points his finger.

Somewhat similarly, Ashurnasirpal II on the so-called Kurkh Monolith points at the divine symbols which are the same as those mentioned in the first lines of the inscription.Footnote 44 It is possible that Shalmaneser III on his Kurkh Monolith pointed at the divine symbols depicted in front of his face.Footnote 45

Discussion

The examples examined so far suggest a different interpretation of the pointing finger gesture, namely as more of a simple deictic gesture than a gesture loaded with religious meanings. As such, the deictic gesture was not carved randomly, it was carefully adapted to each monument. The target of each pointing gesture is almost always clear, and the expressiveness of the gesture also allows a distinction of the target pointed at, whether this is in the text or image close at hand or in the distant environment (context).

The next step is to attempt to single out and postulate the rationale lying behind each monument. A classification of the type of deictic gesture performed (specific, generic, or referring to the function/purpose of the object) is also proposed.

It seems clear that both Tiglath-pileser I (Tigris 1) and Shalmaneser III (Tigris 2, Fig. 1) direct both the viewer and the reader’s gaze to a specific part of the text (specific deictic gesture) that offers information on the identity of the owner. Such a need to identify the king makes sense when the relief is seen within its context, outside the homeland, in a peripheral geography charged with great significance. In this respect, in his comprehensive examination of the “Source of the Tigris” as a symbolic and commemorative landscape, Harmanşah (Reference Harmanşah2007: 180) notes that similar places “constituted loci for the display and its material embodiment, becoming places through which local histories were negotiated and written”. Assyrian kings repeatedly visited this place, and their visits involved a multiplicity of commemorative activities that encouraged the site to welcome their stories and histories. It was therefore essential to mark such a far-off rural landscape and describe the identity of the individual whose achievement was celebrated by means of text and image. Conscious of the non-portraiture role of the royal image, identity could be provided only by means of text. The pointing gesture thus acted as a bridge between text and image by indicating the line that contained the identity of the monument’s owner.

Conversely, monuments erected in the homeland may have been used to convey more complex messages, as the stele of Ashurnasirpal II from Kalhu shows (Fig. 2). The few specific words produced by the king and his gesture (specific deictic gesture) underscore the basic idea that the Assyrian king is the link between deities and humans. This frequent and prominent aspect is often emphasized in other forms and expressions in the so-called Standard Inscription of the same king, which is carved over and over on the wall slabs of his royal palace.Footnote 46 Being defined as the “weapon of the great gods” (kašūš ilāni rabûti), the king is likened to the weapons which he was provided with by the deities.Footnote 47 At the same time, the textual reference presents the king as the divine weapon, and the great gods as his helpers. The image conveys the same message: the king is located just below the divine symbols and does not hold any weapon, because he is the weapon of the gods. This notion is thus expressed both linguistically and visually, and the dialogue between text and image is made possible by the pointing finger which bridges the two media and communicates a significant message.

On the Kenk Gorge rock relief of Shalmaneser III (Fig. 3), the king highlights the textual reference to the sea, which is defined in the inscription as “of the setting sun” (ša šulum d šamši) i.e. the western sea, the name assigned to the Mediterranean.Footnote 48 Shalmaneser reached the Mediterranean Sea in his first regnal year (858), emulating his father Ashurnasirpal II and his ancestor Tiglath-pileser I who was the first Assyrian king to reach the Mediterranean Sea.Footnote 49 Such an act of emulation was already started with the campaign to the above-discussed “Source of the Tigris” and sealed with the carving of his rock relief next to that of Tiglath-pileser I. This might be the reason why the king is pointing his finger at such an important and symbolic achievement (specific deictic gesture), the aim being to inform learned viewers and later kings and help them connect his venture to a tradition of great kings.

A more complex picture emerges from the analysis of the Judi Dagh rock reliefs of Sennacherib (Fig. 4), where the king’s forefinger highlights specific lines within the text (specific deictic gesture). Although the inscriptions show some variations, they are largely duplicates. This implies that this series of reliefs was carved all at once during the campaign conducted by Sennacherib against a number of villages situated on the peaks of Mount Nipur (Judi Dagh). These are defined in the engraved text as “non-submissive lands (and) disobedient people of the mountains” and “an obstinate force that did not know how to respect (any) authority” (RINAP 3/2 222: 10–11, 19–21). The need for protection from such rebellious people might be the reason why the reliefs were located at inaccessible spots.Footnote 50 However, the reason why the same monument was replicated is less clear. It is possible that this was done to guarantee the presence of the royal image in every corner of the mountain where the villages were situated. Alternatively, the slight variations among the monuments, including the different textual targets, suggest that they might be trying to tell a story, perhaps by marking the salient moments of the military actions, in which the king’s ability to climb the difficult mountain is particularly emphasized in the text: “Like a (fierce) wild bull, [I took] the [lead of t]hem (the soldiers in my camp). Where it was too difficult for (my) chair, I leapt forward on my (own) [two feet] like a mountain goat. Wh[ere] my knees became extremely tir[ed], I sat down up[on] the mountain rock and drank cold water from a water skin to (quench) my thirst” (RINAP 3/2 222: 39b–43). Also, the rock reliefs might reflect the narrative of the actual chase of the escapees by the king and his soldiers: “… I surrounded, conquered, (and) devastated those … Their escapees [(…)] upon the peak[s of Mount] Nipur …. I pursued their … on the peaks of the mountains” (RINAP 3/2 222: 44–48a).

Based on this hypothesis, I am tempted to consider anew the interaction between royal image and inscription, with the finger pointing at specific lines within the text, as a conscious intention on the part of the scribes and stone carvers to tell the narrative of that campaign. The incompleteness of the two remaining reliefs and the poor preservation of some of the engraved inscriptions hinder an overall evaluation. However, it is interesting to observe that in Panel I the pointing finger gesture indicates that the deities make the king’s weapons prevail over all enemies; then, on Panel II the gesture goes on by pointing at the line that begins the list of the enemies pursued by the king in the campaign; and finally, on Panel IV, which is said to be “the highest panel on the mountain” (King Reference King1913: 80), the pointing finger is addressed at the first line containing the list of deities, as though the highest point was the closest to the divine world. The ascending movement, from the description of the campaign (lines fours and twelve on panels I and II, respectively) to the names of the deities who bestowed the victory on the king (line one on panels V and IV), can also be traced in geographical terms, with Panel I located just below the crest of one of the lower great ridges of the mountain and Panel IV at the highest point of the main ridge.Footnote 51 The learned viewer and reader could thus be led by the reliefs toward the actual movement of the Assyrian army and follow the historical reasons for the campaign by reading the lines pointed at by the gesture of the king.

The deictic gesture performed by the king can point at an object to evoke the whole class of items the object belongs to (generic deictic gesture) and not simply this particular object. Shamshi-Adad V, for instance, points at a group of campaigns he undertook. The column pointed at by the king is the one that contains the narrative of the campaign against Babylonia, the most significant military venture of Shamshi-Adad V’s career.Footnote 52 It is therefore reasonable to think that the king is drawing the reader’s attention not to a specific object within the text but more generally to the column recounting the most important event of the king. However, since the stele was presumably located in a temple, the pointing finger may be being directed at a dais or a statue representing the dedicatee, as other examples show.

In much a similar way, the so-called Cyprus Stele of Sargon II would adhere to this “tradition” of interplay between deictic gesture and text, where the king points at the column offering the identity of the king and his main political and military achievements (general deictic gesture). Nevertheless, such a reading is hypothetical and speculative, since neither the exact findspot where the stele was found nor the location where it was originally erected are known.Footnote 53 Therefore, other hypotheses should be considered. For instance, the king’s gesture of the pointing finger could have been used to draw the viewer’s attention to a spot outside the stele. On this point, relying on the text only, Radner (Reference Radner, Rollinger, Gufler, Lung and Madreiter2010: 432–433) restored the passage related to the original location as follows: “I erected (the stele) [facing Mount] Baʿal-harri, a mountain [towering ab]ove the country of Adnana”. According to this information, the mount should be located on Cyprus and might be identified with the mountain range around Mount Stavrovouni, situated to the northeast of Kition and overlooking the entire coastal plain, with a view of the Lebanese coast. But rather than being placed on top of the mount, the stele was most likely placed opposite the mountain peak which is visible from Kition itself. This may have implied that the king faced the mountain and thus pointed at the mountain as the main target of his gesture.

A more direct connection between the deictic gesture and the target can be traced to the category of monuments, where the target is clearly in the faraway environment, in the context where it was erected or carved. This is the case with the Tell al-Rimah stele (Fig. 5), which can be fully understood in its original context only: the image of the king, by pointing his finger at the podium and implicitly at the divine symbol, informed any temple visitor that the king dedicated the stele to a specific deity, namely Adad. In other words, the gesture served as a vehicle to communicate the meaning and function of the stele (deictic gesture referring to the function of the object). In a similar way, the deictic gesture depicted on the steles of Nergal-eresh from Tell Sheikh Hamad and the stele of Mushezib-Shamash from Urfa aimed at explaining the function of and the reason for the erection of the monuments. In this context, the rock relief of Shalmaneser III from the “Source of the Tigris” (Tigris 4) and the steles of Sennacherib from Nineveh (Fig. 6) show that the target of the pointing gesture was not necessarily a divine symbol or statue but could be a landscape or a royal road. By means of the deictic gesture, the king easily grasped the attention of any passer-by as to the real reason of the erection of these steles, namely the conquest of a distant place or the construction of a new royal road.Footnote 54

Finally, in some instances the deictic gesture is pointed at specific visual elements that immediately give reasons for the erection of a monument. On the Saba’a stele (Fig. 7) the royal image aims at drawing the attention to the god to whom the monument is dedicated and thus to the reason for its erection (deictic gesture referring to the function of the object). The Tell Abta stele (Fig. 8) shows an interaction between deictic gesture, image and text which is even more complex. The text engraved on the monument begins with a list of deities, whose features and powers are described in detail; then, it proceeds with a presentation of Bel-Harran-beli-usur, who received from the mentioned gods instructions on the foundation of a new city, a description of the building activity, and concludes with blessings and curses.Footnote 55 Now, in the light of the inscription content, the reason why the pointing finger gesture is intentionally directed at drawing the viewer’s attention to the divine symbols appears clear. The order in which the divine symbols are arranged on the monument is the same as the one in the inscription: moving from the left to the right, both the reader and the viewer encounter the god Marduk / spade, Nabu / stylus, Shamash / winged disk, Sin / disc incorporating crescent, Inanna/disc incorporating star. Then, the reader and the viewer come across the stele’s owner, who is introduced in the text just after the deities and is represented on the stele next to the divine symbols. At this point, the reader and the viewer may easily grasp the connection between deities and Bel-Harran-beli-usur, since the text explicitly states that “these mighty lords” – the ones pointed at by the forefinger – gave instructions. The building activity is finally commemorated by the erection of the stele, that is, the one on which the text is inscribed, on which the images of the gods are engraved, and which was in the divine abode. Taken altogether, it is clear that it is such a connection that the pointing finger is visually expressing: Bel-Harran-beli-usur points and gazes at the deities to explain 1) that they are the ones who bestowed on him favor and approval to build a new city, and that, as a consequence of this act, 2) he erected the monument that the viewer is looking at. In other words, the palace herald aims at catching the attention on the dedicatee of the monument, namely the gods (specific deictic gesture).

This reasoning can be extended to the altar of Tukulti-Ninurta I (Fig. 9). Without reading the inscription on the monument, the reason for the erection of the monument is made clear by Tukulti-Ninurta himself, who, in both instances, points his right finger towards the pedestal to indicate the dedicatee of the altar (deictic gesture referring to the function of the object). Moreover, according to the inscription, the king dedicated the altar and appointed the god Nusku to pray daily the prayers of the king. This entails that, paraphrasing the inscription, the forefinger acts as a deictic gesture to say that “this cult platform was dedicated to the god Nusku and this god Nusku is the one who daily repeats my prayers”. The visual effect is that the image depicted is highly expressive: there is no need for the viewer to read the content of the inscription to unveil the reason why the monument was erected, but it was sufficient to gaze at the image to understand that it was dedicated by an Assyrian king to a specific god for a specific reason.

Taken altogether, these examples emphasize the entanglement of relationships between texts, contexts, and images, leading one to speculate on the existence of standard specific rules that were adopted and adapted by scribes and stone-carvers each time.

Intentionality and Readability

The role of texts, contexts, and images in the examples examined so far is in most cases straightforward but requires an understanding of the conventions determining the viewing. What determines the mode of reading is the symbolic system that happens to be in effect, which in this context seems to have been the deictic gesture pointing at a significant target within the inscribed text, the context where the monument was located, or the carved image. The deictic gesture became somehow a convention or matter of habit that Assyrians were probably keen to exploit as a visual device to communicate. The intentionality of the pointing finger gesture seems clear, based on a statistical analysis of the evidence collected. The abundant ways in which the royal portrait and the inscribed text were physically and conceptually brought together might lead one to suspect that in some instances the interaction occurred casually.Footnote 56 However, many examples show that the finger gesture is pointed at specific and unambiguous targets (e.g., divine symbols, divine statues) which unavoidably turns it into a deictic gesture used to draw the observer’s attention to specific elements.

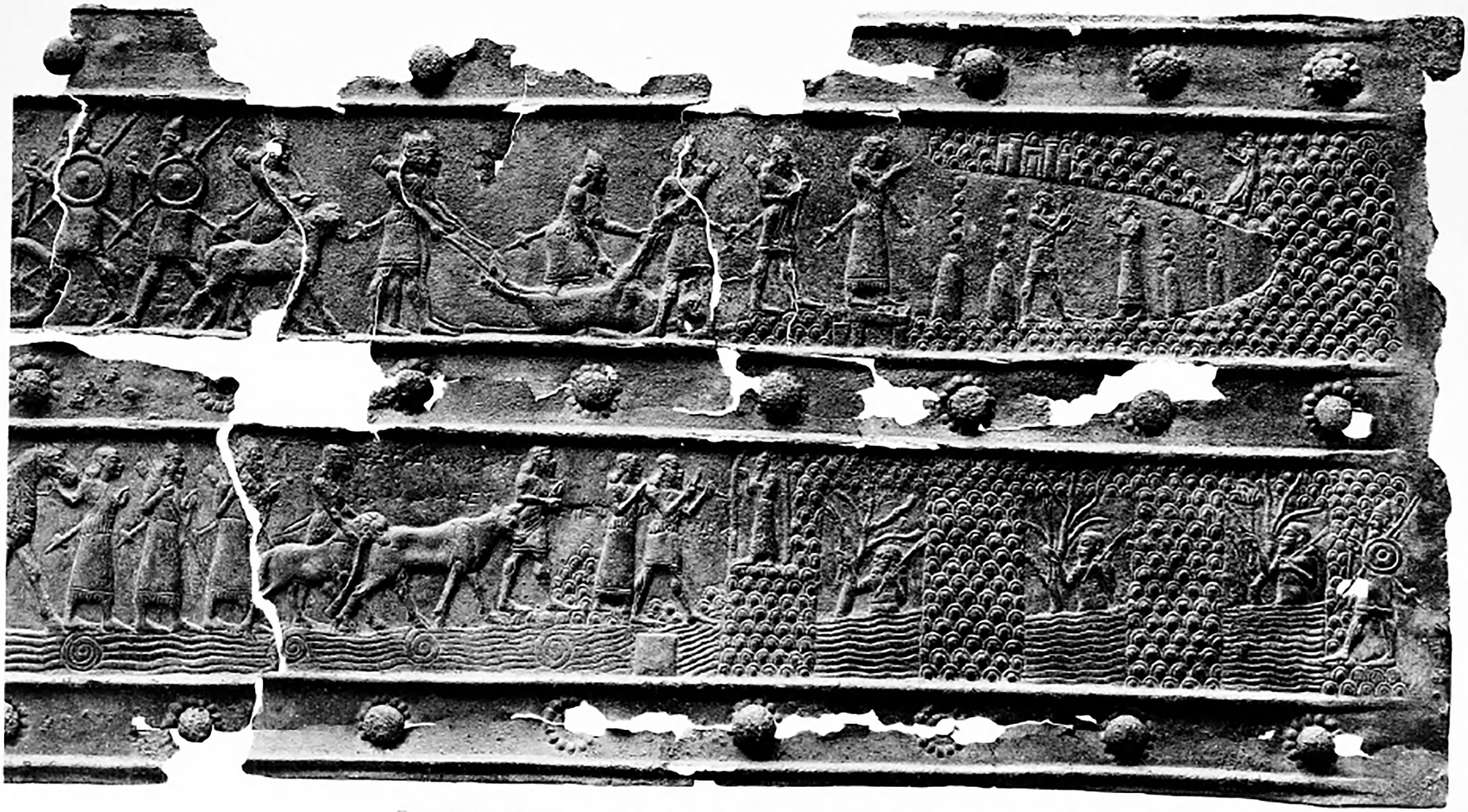

The intentionality lying behind the interactions between deictic gesture and specific targets is further supported by the fact that Assyrian monuments were the product of an intense cooperation between various workers (masons, engravers, scribes). In this respect, it is sufficient to look at the bronze band reliefs that fastened the monumental timber gates from the city of Imgur-Enlil (Tell Balawat) of Shalmaneser III. In particular, the episode narrated on the upper and lower registers of relief 10, identified as Shalmaneser III’s visit to the “Source of the Tigris”, culminates in the ceremonial carving of the king’s images and inscriptions (Fig. 10). The outstanding details of this scene lie not only in the representation of a specific place and the series of sacrificial animals, but especially in the physical and functional proximity of the figures who are carving the monuments. The content of these images is crystal-clear: the two groups of figures are essentially composed of professionals belonging to the class of scribes and stone-carvers who are cooperating to carve the royal portrait and the accompanying inscription. The identity of each professional cannot be ascertained with certainty, but written sources inform us that in the making of official art the professional involved was certainly literate and had skills to prepare sketches as models for making images. Similarly, the task of drafting content and composing inscriptions was the work of scribes (ṭupšarru). The execution was then performed by the stone-carver (parkullu), the sculptor (urrāku), and the engraver (kapšarru).Footnote 57 Some of these figures are certainly depicted in the bronze band and are distinguished by their function and dress. As to the actions performed, it seems clear that there is a supervisor who is giving instructions to the professional with the hammer and chisel. In the upper register, the cooperation is even more complex, given the presence of a further scribe who is supervising the work of the stone carver. Taken altogether, the scene clearly presents the figures involved in the making of a monument and entails a clear division of productive labor. It comes as no surprise then that the king’s finger was intentionally made to interact with specific selected elements.

Fig. 10. Detail of relief panel 10 of the gates of Shalmaneser III, Tell Balawat (Imgur-Enlil) (King Reference King1915: pl. 59)

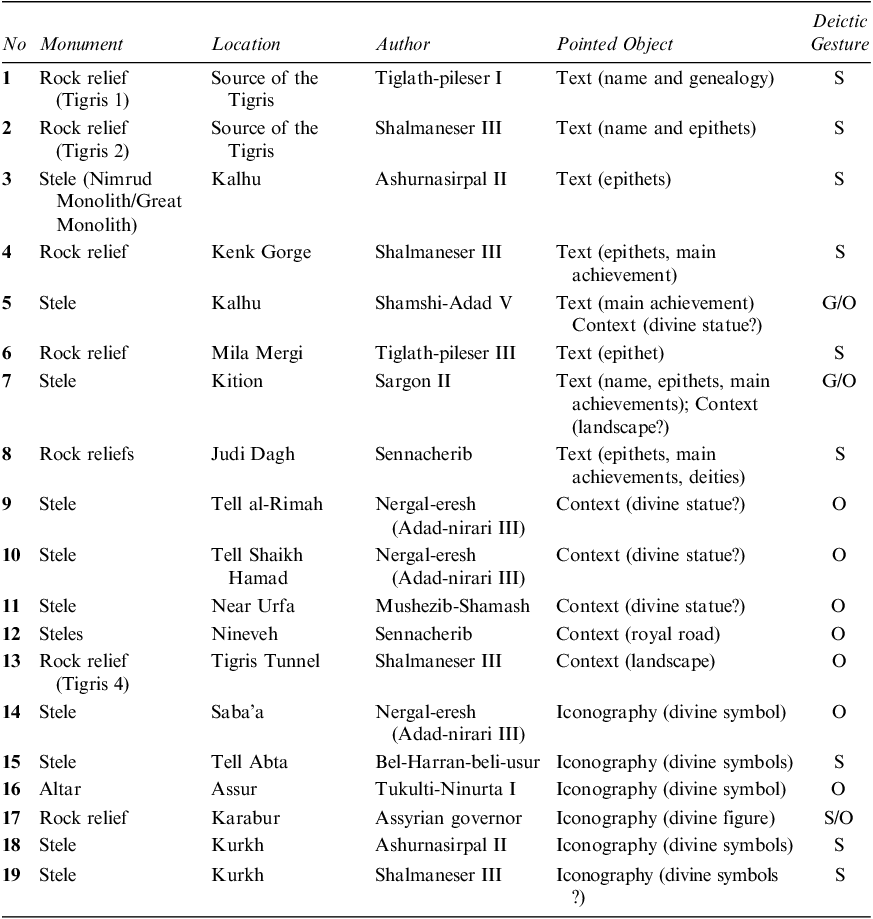

The interactions are manifold. A brief look at Table 1 brings out the various ways through which the pointing finger gesture interacted with textual, contextual, or iconographic elements. The choice of one or the other may have depended on several reasons. But in general, one may assert that interactions between text and image required a close cooperation between scribes and stone carvers. Alternatively, it may be possible that the absence of well-trained workers or the lack of time may have hindered complex works. This might be the case with the four steles erected by Assyrian officials on behalf of their kings, where the selected target of the pointing gesture is a contextual or iconographic element. These four examples also bear scribal mistakes and oddities within the text, suggesting that there were no experts to elaborate a more complex dialogue between text and image.Footnote 58 The Kurkh Monoliths also do not show a clear correlation between the pointing finger and elements in the text or in the image, a point which might be explained by the fact that both monoliths were carved hastily, given the several errors made by the scribe during their execution.Footnote 59 This indicates that lack of time could lead to clumsy choices and mistakes and, by contrast, that polished works required a well-thought-out work plan.

Table 1: Specific (S), generic (G) deictic gesture or referring to the function of the object (O)

Notwithstanding the clear division of productive labor, the monuments were nevertheless perceived in isolation, with their texts, depictions and context all present for the viewer’s examination. In this respect, one wonders whether a contemporary observer was able to catch all the interactions detected. The question of readability is thus at stake and requires some speculation. The issue of the audience in this environment is essential and would require an in-depth examination of each case. As a general view, one may postulate that, as for palace reliefs and inscriptions, the audience of steles and rock reliefs could be grouped into those which were situational, targetted, and temporal.Footnote 60 The situational audience is represented by the group of persons who either visited or randomly came across the monument; the target audience is represented by a specific group that the Assyrian king and his retinue on campaign singled out as the group(s) which was supposed to see the royal portrait and read the inscription; and, finally, the temporal audience includes the future generation, especially rulers and princes as well as deities. A situational audience is not easy to identify, whereas the target and the temporal ones often coincide and are explicitly mentioned in textual sources. In fact, carved inscriptions on steles and rock reliefs often call upon “scholars” (ummânu), “scribes” (ṭupšarru), “diviner” (bārû), and the king’s posterity (a future prince) as the expected readers who could read and change the content of the inscription. It is not by chance that the expressions used imply verbs of “seeing” (amāru) and “reading” (šasû) and the requests include not to change or chisel away words.Footnote 61 This entails that this group of persons was expected to reach even far-off monuments, carefully inspect the inscription, and grasp the targets of the pointing finger gesture accordingly.

Other Examples and Concluding Remarks

It is the hope of this paper that the new reading of the alleged ubāna tarāṣu as a simple deictic gesture will encourage other scholars to start an in-depth review of all Assyrian monuments, including palace reliefs and seals, to identify a higher number of connections between the deictic gesture and its targets. In this regard, one may expect a more complex cooperation between scribes and stone-carvers in the royal palaces, and thus more well-thought-out connections and interactions. A couple of final examples may be useful in this respect.

In the famous motif of the king standing at both sides of the stylized tree in the Northwest Palace at Kalhu (labelled as B–23, and B–13), and employed on seals by elite individuals throughout the empire, the king on the right points his finger at the divine symbol, whereas the king on the left points at the stylized tree.Footnote 62 This change of target supports the notion that the gesture performed by the king did not imply any prayer or act of adoration, but served as a deictic gesture to draw the attention of the observer to the divine symbol and the stylized tree. But there might be more to this gestural iconography. The two reliefs were situated respectively behind the throne dais and in the alcove where the throne was occasionally placed. This implied two visual effects: the king, when seated on the throne, covered the stylized tree, with the consequence that he became the target of the deictic gesture. As to the divine symbol, this likely represents the sun-god Shamash.Footnote 63 If we now look at Ashurnasirpal II’s royal inscriptions, the pointing finger and its interaction with the symbol of Shamash and with the king himself is conspicuous: Ashurnasirpal II states that, in his accession year and his first regnal year, “the god Šamaš, judge of the (four) quarters, spread his beneficial protection over me (and), having nobly ascended the royal throne, he placed in my hand the sceptre for the shepherding of the people”. In another text, he presents himself as “unrivalled king of the universe, king of all the four quarters, sun(god) (d šam-šu) of all people”.Footnote 64 These textual references associate Shamash with the king quite directly and make the deictic function of the gesture clear: the king points his finger at Shamash to underline that he is protected by the god, and points his finger at himself in the flesh because he considers himself Shamash. The pointing gesture thus clearly conveys the visual message that Ashurnasirpal II controls and orders over the known world, just as the god manifests the light of his rule over the world.

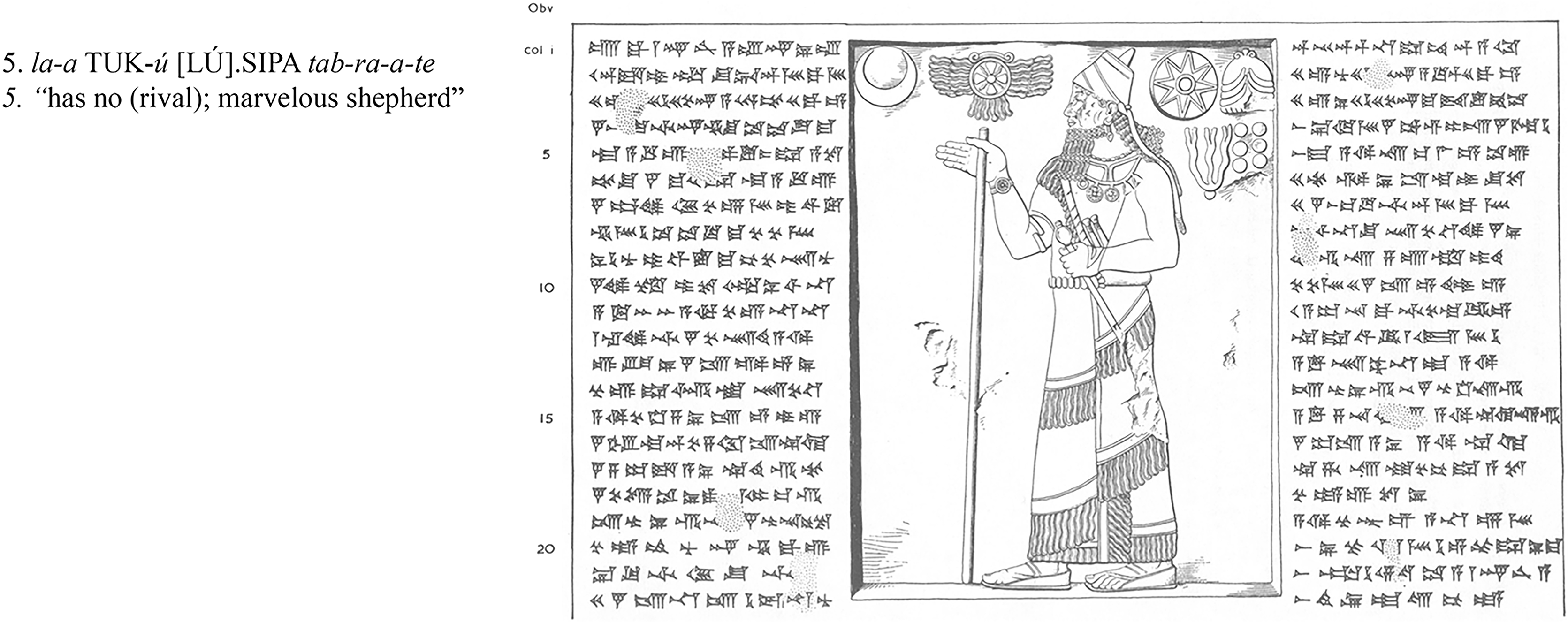

A further example from Ashurnasirpal II’s reign is represented by his famous Banquet Stele. On the top of the monument the king holds a sceptre in his left hand and the long staff in his right opened hand, performing the gesture of salutation. In a previous analysis I have argued for a correspondence between the verbal epithet “shepherd” and the representation of the king holding a long staff, thus suggesting that the long staff truly symbolizes the shepherding role of the Assyrian king and his paternalistic attitude towards his flock.Footnote 65 This thesis can be confirmed by the close interaction between text and image that scribes and stone carvers decided to create. Although the king does not perform the pointing gesture, his hand is nevertheless pointed at line five within the text where the epithet “marvelous shepherd” is located (Fig. 11).Footnote 66 In a sense, both king’s gaze and hand direct the viewer and reader’s gaze to the left column and, more specifically, to the line where the king is properly presented as shepherd.

Fig. 11. Detail of the Banquet Stele of Ashurnasirpal II (Wiseman Reference Wiseman1952: pl. VII)

Other examples can be found throughout Assyrian imagery and the assumption that bodily expressions could act as deictic gestures in communication may subvert the perception we have of the Assyrian gestural world as having exclusively religious connotations (e.g. as necessarily consisting of prayer or adoration gestures toward deities). There is no reason to relabel the visual idiom, and the linguistic expression ubāna tarāṣu may well have been used to describe the pointing finger gesture. I also do not want to rule out the possibility that the gesture could have had a range of meanings, as suggested by other authors. Nevertheless, all existing evidence points to the association of the ubāna tarāṣu with a simple deictic gesture, loaded with more practical implications. The inescapable conclusion, that the pointing finger gesture was used to direct the viewer’s attention, highlights the need for a more holistic and unbiased view of Assyrian monuments.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/irq.2024.16

Acknowledgments

I owe Joshua Jeffers a debt of gratitude for his help, expertise, and long conversations on the issue of gesture and meaning, which lay the foundations for the writing of this article. My thanks also go to Holly Pittman for productive conversation and for sharing with me her insightful ideas on image/text relations. Finally, Grant Frame graciously supplied information and support in the understanding of Assyrian royal inscriptions.