1. Introduction

Innovation activities, such as R&D investments, are pivotal for income per capita and long-run productivity growth (Aghion and Howitt, Reference Aghion and Howitt1992; Grossman and Helpman, Reference Grossman and Helpman1991; Romer, Reference Romer1990). Hence, the importance of identifying the drivers of innovation activities cannot be overemphasized. Consistent with this idea, there is now a growing body of literature examining the relationship between social trust and innovation activities (e.g. see Akçomak and ter Weel, Reference Akçomak and ter Weel2009; Doh and Acs, Reference Doh and Acs2009). However, this literature has paid little attention on mechanisms through which social trust can affect innovation activities. This paper is an attempt to fill this gap.

In this paper, I identify two potential mechanisms – access to credit and reduction in relational risks – through which social trust can affect R&D investments. The importance of these mechanisms is based on the well-established literature suggesting that access to credit and effective contract enforcement, which are relational risks reducing, incentivize R&D investments (Agénor et al., Reference Agénor, Canuto and Jelenic2014; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Martinsson and Petersen2012; Khanna and Mathews, Reference Khanna and Mathews2016; Seitz and Watzinger, Reference Seitz and Watzinger2017). Accordingly, the mechanisms considered in this paper evaluate how social trust encourages R&D investments by enhancing access to credit and reducing relational risks. Specifically, the first mechanism examines the role of social trust in overcoming moral hazard and adverse selection problems and, therefore, reducing the firm's cost of external capital. On the other hand, the second mechanism examines the role of social trust in reducing ex-post holdups and risks of expropriations if the firm makes relationship specific-investments.

To test these ideas, I exploit inter-industry differences in the levels of external finance dependence and exposure to relational risks. In particular, I make two identification assumptions that enable me to exploit these inter-industry differences in identifying the effect of social trust on R&D investments. First, because higher levels of social trust reduce the firm's cost of external capital, firms located in trust-intensive societies will have more access to the requisite capital to fund promising R&D projects. While this may be true across firms, it should apply more forcefully in industries that depend more on external finance, given the greater efficiency of capital allocation. Second, because higher levels of social trust reduce relational risks, it should disproportionately benefit firms that are more vulnerable to relational risks. I evaluate these mechanisms by testing whether more external finance dependent and relational risks vulnerable industries exhibit disproportional higher R&D intensities in trust-intensive countries compared to those industries in low-trusting countries.

The approach I utilize to evaluate these mechanisms is closely related to the difference-in-difference methodology that Rajan and Zingales (Reference Rajan and Zingales1998) use to identify the causal connection between financial development and industry-level growth. Using this method, I can test the hypotheses by examining how the interaction of country-specific indicator of social trust level (T it) and industry-specific indicators of external finance dependence (x s) on the one hand, and exposure to relational risks (r s), on the other hand, affect industry R&D intensities. If the interaction term $\quot \lpar {T_{it} \times x_s} \rpar {\rm \;}\quot$![]() enters positively in the estimated equation, it suggests that, on average, more external finance dependent industries have relatively higher R&D intensities in trust-intensive countries. Similarly, if the interaction term $\quot \lpar {T_{it} \times r_s} \rpar {\rm \;}\quot$

enters positively in the estimated equation, it suggests that, on average, more external finance dependent industries have relatively higher R&D intensities in trust-intensive countries. Similarly, if the interaction term $\quot \lpar {T_{it} \times r_s} \rpar {\rm \;}\quot$![]() enters positively in the estimated equation, it suggests that on average, industries that are more exposed to relational risks have relatively higher R&D intensities in trust-intensive countries.

enters positively in the estimated equation, it suggests that on average, industries that are more exposed to relational risks have relatively higher R&D intensities in trust-intensive countries.

As an empirical measure of industry R&D intensities, I use the ratio of R&D expenditure to value-added. Following the existing literature (e.g. see Bottazzi et al., Reference Bottazzi, Da Rin and Hellmann2016; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liu and Wang2016; Levine et al., Reference Levine, Lin and Xie2018; Pevzner et al., Reference Pevzner, Xie and Xin2015), I measure social trust as the proportion of a country's population in a year that ‘agrees’ with the statement in the World Value Survey: ‘Most people can be trusted.’ External finance dependence is measured using the industry external finance dependence initially computed by Rajan and Zingales (Reference Rajan and Zingales1998). The index measures for each industry, the share of capital expenditures not financed with cash flows from operations. Because firms depend on external finance to fund their activities, including R&D, they are prone to financial frictions in the credit market, which, as I argued, decreases with higher levels of social trust. Lastly, I use Nunn's (Reference Nunn2007) ‘contract intensity index’ as a proxy for an industry's vulnerability to relational risks. The index measures for each industry, the proportion of intermediate inputs which are not traded on active markets. Because these goods are not traded on active markets, they require relationship specific-investments to be made, thereby exposing the R&D investing firm to potential ex-post holdups.

Results from the empirical analyses confirm that social trust increases R&D intensities. When we examine the pathways linking social trust and R&D investments, the results are consistent with the hypothesis that more external finance dependent and relational risks vulnerable industries exhibit disproportional higher R&D intensities in trust-intensive countries. These results are robust to several robustness checks. Hence, the results underline access to credit and a reduction in relational risks as pathways linking social trust and R&D investments. Calculating the sizes of the effect of either of the mechanisms shows a sizeable impact. For instance, the baseline result suggests that a one standard deviation expansion in the social trust level will increase R&D intensities by 1.5 percentage point for an industry at the average external finance dependence and by 4.8 percentage point for an industry at the average relational risk exposure.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows; Section 2 presents an overview of the previous literature; Section 3 develops the hypotheses; Section 4 discusses the research methodology; Section 4 presents the empirical results, while Section 5 concludes.

2. Related literature

Social trust is the expectation within a community that people will behave in honest and cooperative ways and the extent to which human interactions are governed by the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness (Levine et al., Reference Levine, Lin and Xie2018; Putnam, Reference Putnam2000). These expectations usually narrow the set of possible actions, thus reducing the uncertainty surrounding the actions of economic actors (Sako, Reference Sako, Lane and Backmann2002). According to Bjørnskov and Méon (Reference Bjørnsko and Meòn2015: 318), social trust reflects the average trustworthiness of people and thus the likelihood that they abide by both formal rules and informal social contracts. It also implies that firms can apply longer time horizons when making investment decisions, which allows them to invest in riskier, but potentially more productive processes (ibid). Consistent with these views, several studies have examined the effects of social trust on economic growth. Evidence from these studies suggests that higher levels of social trust increase economic growth (for a review of literature, see Bjørnskov, Reference Bjørnskov and Uslaner2018).

In light of this evidence, the trust literature has analyzed the effects of social trust on different economic variables in an attempt to explain how social trust affects economic growth. Among others, extant studies have analyzed the effects of social trust on investments in human and physical capital (Dearmon and Grier, Reference Dearmon and Grier2011; Knack and Keefer, Reference Knack and Keefer1997), productivity (Bjørnsko and Meòn, Reference Bjørnsko and Meòn2015), stock market performance and financial development (Guiso et al., Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2004, Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2008; Pevzner et al., Reference Pevzner, Xie and Xin2015), and international trade (Roy et al., Reference Roy, Munasib and Chen2014). Studies have also examined how social trust affects economic growth by strengthening formal institutions (Bjørnskov and Méon, Reference Bjørnsko and Meòn2015). Whereas the respective literature on how social trust can affect economic performance is well-established, the relationship between social trust and innovation only gained the interest of scholars in recent times.Footnote 2

Studies examining the relationship between social trust and innovation activities can be broadly classified into two groups. The first group includes studies that examine the relationship between social trust and innovation activities at the regional level (e.g. see Akçomak and ter Weel, Reference Akçomak and ter Weel2009; Miguélez et al., Reference Miguélez, Moreno and Artís2011), while the second group include studies that examine the relationship at the country level (e.g. see Dakhli and De Clercq, Reference Dakhli and De Clercq2004; Doh and Acs, Reference Doh and Acs2009). In both groups, the number of patent applications is usually employed to proxy innovation activities, while social trust is measured using the percentage of survey respondents who agree to the question, ‘most people can be trusted.’ Evidence from these studies suggests that social trust is positively associated with innovation activities at the regional and country level. Underpinning this empirical regularity is that social trust is a more effective and cost-efficient way of reducing transaction costs, solving moral hazard problems, and encouraging information exchange between economic actors, which are pivotal for innovation activities (Akçomak and ter Weel, Reference Akçomak and ter Weel2009).

However, empirical investigations about the nexus between social trust and innovation activities have only examined the linear relationship between social trust and innovation activities. This leaves one speculating about the potential factors that can explain the positive association between social trust and innovation activities. The current paper attempts to fill this gap by evaluating two potential mechanisms – access to credit and reduction in relational risks – through which social trust can affect R&D investments.

3. Hypothesis development

The theoretical underpinning of this study builds on the well-established literature suggesting that access to credit and effective contract enforcement, which are relational risks reducing, incentivize R&D investments (Agénor et al., Reference Agénor, Canuto and Jelenic2014; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Martinsson and Petersen2012; Khanna and Mathews, Reference Khanna and Mathews2016; Seitz and Watzinger, Reference Seitz and Watzinger2017). On the one hand, R&D is a cost-intensive activity, often requiring external financing because R&D investing firms easily exhaust their internal funds (Agénor et al., Reference Agénor, Canuto and Jelenic2014; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Lai and Chen2017).Footnote 3 On the other hand, investments in research projects often require collaboration with multiple parties or making relationship specific-investments. These expose a firm to ex-ante and ex-post holdups or outright intellectual property expropriation, which can discourage investments in research projects. My goal is then to evaluate how social trust, which reflects the average trustworthiness of people in a society, can encourage innovation activities by enabling access to credit and reducing relational risks. The motivation for this builds on the conventional view that trust underlies virtually all economic activities (Arrow, Reference Arrow1972; Knack, Reference Knack2001; Knack and Keefer, Reference Knack and Keefer1997); and two prominent pathways it achieves this, as often emphasized in the literature, are access to alternative sources of credit (Bottazzi et al., Reference Bottazzi, Da Rin and Hellmann2016; Duarte et al., Reference Duarte, Siegel and Young2012), and a self-enforcing contract (Knack and Keefer, Reference Knack and Keefer1997; Lyons and Mehta, Reference Lyons and Mehta1997).

Firstly, higher levels of social trust can reduce a firm's cost of external capital by reducing moral hazards and adverse selection problems. The intuition is that in a trust-intensive society, being opportunistic (i.e. moral hazard) goes contrary to society's moral values, and it usually attracts social sanctions and stigmas. Therefore, borrowers in such a society would have a lower likelihood of default as they are bounded by high moral standards, while credit lenders would be more willing to lend to borrowers from such a society because of a reduced concern over opportunistic behavior. High social trust levels can also ease access to credit by reducing information asymmetries between borrowers and credit lenders (i.e. adverse selection). Pevzner et al. (Reference Pevzner, Xie and Xin2015) and Jha (Reference Jha2019) both argue and empirically show that firms in trust-intensive societies are less likely to manipulate their financial reports. Consequently, credit lenders perceive their financial reports as more credible and are more likely to lend to them. The preceding arguments are consistent with plethora of studies indicating that higher levels of social trust increase a firm's access to external capital (Bottazzi et al., Reference Bottazzi, Da Rin and Hellmann2016; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liu and Wang2016; Duarte et al., Reference Duarte, Siegel and Young2012; Levine et al., Reference Levine, Lin and Xie2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Firth and Rui2014) or the supply of bank credit (Cruz-García and Peiró-Palomino, Reference Cruz-García and Peiró-Palomino2019; Guiso et al., Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2004).

The preceding discussion suggests that to the extent higher levels of social trust reduce a creditor's concerns about the various dimensions of borrowing firm riskiness, the creditor would be more willing to lend to borrowers in a trust-intensive society. This suggests a positive association between social trust and innovation activities. However, because the causal mechanism that leads to this effect goes through credit access, it is natural to expect that any observed impact of social trust will vary depending on the relative dependence of firms on external capital in funding their operations. Therefore, social trust should have a relatively stronger impact on innovation activities of borrowers in industries that are more reliant on external finance in funding their operations. The first hypothesis therefore is:

Hypothesis 1: Higher levels of social trust will promote innovation activities in industries that are more dependent on external finance.

Secondly, social trust as an informal institution mitigates relational risks that may lead to underinvestment in new research projects. Seitz and Watzinger (Reference Seitz and Watzinger2017) argue that when active markets for inputs do not exist or firms are unable to write enforceable contracts with input suppliers, firms might be unwilling to invest in the development of a new product if a supplier delivering an essential input can ex-post extract all the rents resulting from a successful research effort. While they centered their argument around formal contract enforcement, the prevailing wisdom is that informal institutions such as trust is an integral part of a country's overall contracting environment and it either complements or substitutes formal contract enforcement mechanisms where governments are either unable or unwilling to provide one (Guiso et al., Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2004; Knack and Keefer, Reference Knack and Keefer1997; Mccannon et al., Reference Mccannon, Asaad and Wilson2017). To the extent that social trust reflects the average trustworthiness of people and the likelihood that they abide by both formal rules and informal social contracts (Bjørnskov and Méon, Reference Bjørnsko and Meòn2015), it would offer similar gains as formal contract enforcement. This conclusion is in line with studies suggesting that social trust encourages economic activities by reducing opportunistic behaviors (Carlin et al., Reference Carlin, Dorobantu and Viswanathan2009; Cline and Williamson, Reference Cline and Williamson2019; Lyons and Mehta, Reference Lyons and Mehta1997).

The preceding discussion suggests that social trust encourages innovation activities by reducing ex-ante and ex-post holdups, and opportunisms that may arise in relationship specific-investments. This suggests a positive association between social trust and innovation activities. However, because the causal mechanism that leads to this effect goes through contract enforcement, the marginal effects should be higher for those firms that depend more on relationship specific-investments because they are more exposed to ex-ante and ex-post holdups, and expropriation risks. Therefore, social trust should have a relatively stronger impact on innovation activities of firms in industries that are more vulnerable to relational risks. The second hypothesis therefore is:

Hypothesis 2: Higher levels of social trust will promote innovation activities in industries that are more exposed to relational risks.

Finally, it is worth noting that while the preceding hypotheses relate to two specific mechanisms linking social trust and innovation activities, there are other mechanisms such as information sharing, group formation, and coordination. For instance, while several studies have demonstrated that information sharing enables firms to enhance innovation performance and reduce redundant learning efforts (Wang and Wang, Reference Wang and Wang2012), team members and organizations outside the bounds of the firm require the existence of trust to respond openly and share their knowledge. Because social trust reflects the average trustworthiness of people and thus the likelihood that they abide by both formal rules and informal social contracts (Bjørnskov and Méon, Reference Bjørnsko and Meòn2015), it signals the employer about how workers will behave when entrusted with certain information. Regarding group formation, while studies have demonstrated that work autonomy leads to better firm innovation performance (e.g. see De Spiegelaere et al., Reference De Spiegelaere, van Gyes, De Witte and Van Hootegem2015), van Hoorn (Reference van Hoorn2017) argues that work autonomy only pays off if it is accompanied by a certain amount of trust which the principal can infer from the local trustworthiness. Furthermore, social trust as a cooperative norm may serve to reduce the uncertainties and monitoring costs faced by entrepreneurs and thus promote innovation activities. It is also possible that social trust affects innovation activities by strengthening the effect of formal institutions.

4. Data and estimation equation

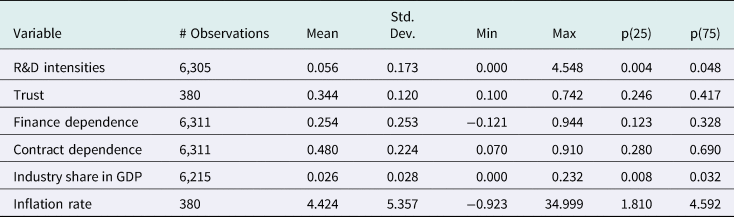

The four most essential variables in my empirical analysis are R&D intensities, measures of industry external finance dependence and exposure to relational risks, and data on social trust. R&D intensities are calculated as the ratio of industry R&D expenditure to value-added at the 2-digit International System Industry Classification Revision (ISIC Rev.) 3.1. Data on R&D expenditures come from the OECD Analytical Business Enterprise and Research database, while data on industry value-added comes from the OECD Structural Analysis (STAN) database. Owing to missing observations on industry R&D expenditures for many countries, and because data on industry external finance dependence and relational risks vulnerability are available for only 21 manufacturing industries, the analysis is restricted to an unbalanced panel comprising 21 manufacturing industries in 20 countries over the period spanning 1990–2008. For the remaining few missing observations, I use linear interpolations to fill them up. The basic summary statistics of the R&D intensities are reported in Table A1 in the appendix.

Data on industry external finance dependence and exposure to relational risks come from Maskus et al. (Reference Maskus, Milani and Neumann2019) and Seitz and Watzinger (Reference Seitz and Watzinger2017), respectively. Both variables are calculated from the US data. The variables are country and time-invariant but vary across industries. The external finance dependence was computed as the ratio of capital expenditures less cash flow from operations for all publicly-listed US firms in the Compustat database over the periods 1990–1999. The value for the median firm in each industry is then taken as the industry's external finance dependence value. By construction of this index, it follows that while firms with higher cash flow can use internal funds to finance capital expenditures, including R&D, the same cannot be said about firms with lower cash flow, which makes them depend more on external finance. Hence, more external finance dependent industries should respond more to changes in the variables affecting the credit market, such as the trust level.

As an indicator of industry exposure to relational risks, I use Nunn's (Reference Nunn2007) ‘contract dependence index,’ which has been aggregated at the 2-digit ISIC Rev. 3.1 by Seitz and Watzinger (Reference Seitz and Watzinger2017). The index measures for each industry, the proportion of intermediate inputs which are not traded on active markets.[1] To compute the index, Seitz and Watzinger (Reference Seitz and Watzinger2017) combine the 2002 United States Input-Output Use Table with data on whether these intermediate inputs are reference-priced or sold through an organized exchange. They then aggregate the inputs at the 2-digit ISIC Rev. 3.1 level. Because these inputs are not traded on active markets, they require producers to make relationship specific-investments which are relational risks increasing. Such risks include either exposure to ex-post holdups or outright expropriation of intellectual property. Table A2 in the appendix lists the industries together with the indicators on contract and finance dependence.

As it is evident by now, the external finance dependence and relational risks vulnerability indicators are not specific to an industry's R&D intensity. Ideally, it would be better to use an industry's measure of external finance dependence that is specifically for expenditures related to R&D and relationship specific-investments that are directly targeted at R&D. While this is a limitation of this study, it does not compromise the central message of the paper because these indexes capture the overall industry external finance dependence and exposure to relational risks.Footnote 4 Further, the indexes are not country-industry specific. While this is due to the lack of comparable cross-country data to compute such indexes, the empirical framework adopted in this paper treats the external finance dependence and relational risks vulnerability as technological components of an industry. That is, it is for technological reasons that, say, the textile industry depends more on external finance to fund its operation than the food products and beverages industry. In this case, what matters is only the ranking of industries along these technological characteristics. An added advantage of this approach is that it ensures the industry characteristics are not endogenous to the macroeconomic dynamics of a country. Nevertheless, this assumption is not without criticism.

Ciccone and Papaioannou (Reference Ciccone and Papaioannou2016) have argued that using a country's industry technological characteristics for other countries is more likely to result in a benchmarking bias, which can shift estimates downwards or upwards. A downward bias occurs when the benchmarking of industries is subject to random measurement error. In contrast, an upward bias may occur because the resulting industry benchmark is more accurate only for countries that are institutionally more similar to the benchmark country (van Hoorn, Reference van Hoorn2017). To alleviate these concerns, van Hoorn (Reference van Hoorn2017) relied on industry technological characteristic that is obtained from a diverse number of countries rather than a single country. While I do not pursue this approach in this paper, an avenue for future work would be to examine whether the results reported here hold when using industry technological characteristics that are obtained from a diverse number of countries.

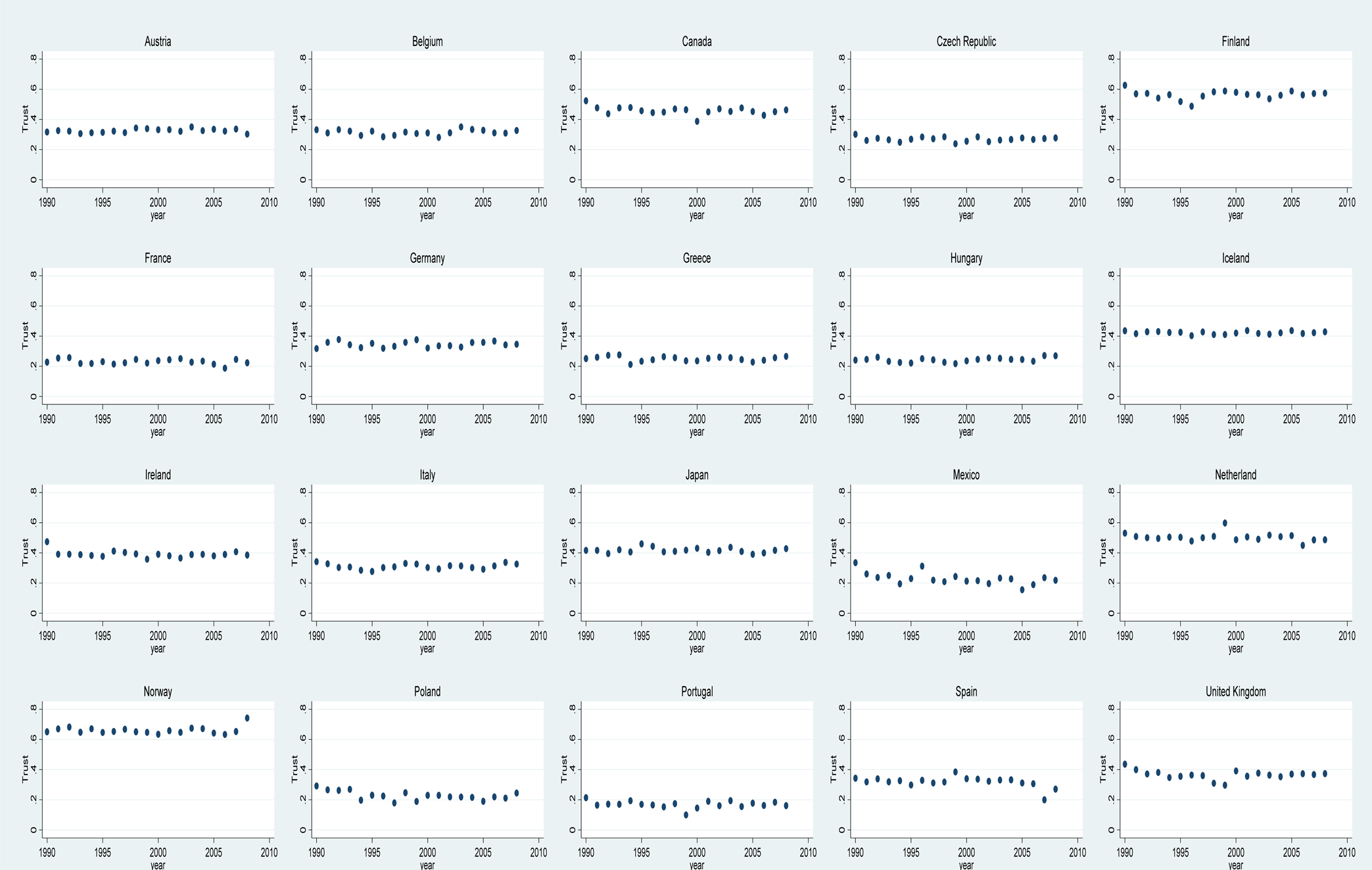

Finally, for the social trust level, I use the perception-based trust indicator from the World Value Survey (WVS), which has become the standard trust indicator. It is measured as the proportion of a country's population that ‘agrees’ with the statement, ‘Most people can be trusted.’ Different studies have employed this variable to evaluate the effect of informal institutions on different socioeconomic outcomes (Bottazzi et al., Reference Bottazzi, Da Rin and Hellmann2016; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liu and Wang2016; Levine et al., Reference Levine, Lin and Xie2018; Pevzner et al., Reference Pevzner, Xie and Xin2015; Zak and Knack, Reference Zak and Knack2001). The variable is directly taken from the CANA Dataset (Castellacci and Natera, Reference Castellacci and Natera2011).Footnote 5 However, the original data comes from the WVS, a cross-country based survey data that is collected since 1981. The basic summary statistics of the trust variable are reported in Table A1 in the appendix, while Figure A1 in the appendix shows the intra-country variation in the trust variable. We only observe small within-country variations in the trust variable. This is in line with the earlier argument of Bjørnskov (Reference Bjørnskov2007) that trust scores are relatively stable over time.

In what follows, to test the hypothesis that more external finance dependent and relational risks vulnerable industries experience higher R&D intensities in trust-intensive countries compared with those industries in low-trusting countries, results based on estimating variations of the following equation will be presented:

where R si,t is the R&D intensity in industry s in country i, δ s is the industry fixed-effect. δ i and δ t are country and year fixed-effects, respectively. T it is a country's social trust level. x s and r s are measures of industry external finance dependence and exposure to relational risks, respectively. In the baseline regression, I follow Maskus et al. (Reference Maskus, Milani and Neumann2019) and control for the industry share in GDP computed as industry production divided by GDP. I also account for a country's macroeconomic environment using the country inflation rate. Data on annual industry production comes from the OECD STAN database, while data on GDP and inflation rate come from the World Development Indicators.

Based on the hypotheses developed in section 3, γ and φ are the parameters of interest and are expected to be positive and statistically significant at all times. A positive γ suggests that trust-intensive countries have, on average, higher R&D intensities in industries that are more dependent on external finance. On the other hand, a positive φ suggests that trust-intensive countries have, on average, higher R&D intensities in industries that are more exposed to relational risks. This identification strategy builds on the seminal work of Rajan and Zingales (Reference Rajan and Zingales1998).

In the robustness section, I further control for several variables. First, I control for the overall development of a country using its income per capita. Original data used to compute this indicator come from the Penn World Table version 9. To isolate the effect of social trust from formal contracting institutions, I use the rule of law index from the World Governance Indicator. Data on the variable is only available from 1996. Between the periods 1996–2002, the data is only available on 2 years interval. To minimize missing observations in these periods, I take averages such that the observation, say, in 1997 is the mean value between 1996 and 1998, and so on. I also control for the level of patent rights protection in a country since R&D often yields intangible assets which are protected by patents. For this, I use the Ginarte and Park (Reference Ginarte and Park1997) index. The index is available on 5 years interval for a number of countries beginning in 1960. To minimize losing observations, I extrapolate the observations such that the values, say, in 1990 is the same for 1991 until 1994 while the value in 1995 is the same in 1996 until 1999, and so on. Maskus et al. (Reference Maskus, Milani and Neumann2019) found that (formal) financial development matters decisively for R&D investments. Accordingly, I use the financial development index from the IMF database to proxy the overall financial development of a country. I also use it to isolate the effect of the formal financing channel from the informal financing channels. To distinguish the effect of social trust from other country characteristics, I control for the level of human and physical capital in each country. Data on both variables come from the Penn World Table version 9. Finally, I also control for other industry characteristics, including skill and capital intensity and asset tangibility. This is to minimize potential industry confounding factors that may bias the results. Data on these variables come from Seitz and Watzinger (Reference Seitz and Watzinger2017) and Maskus et al. (Reference Maskus, Milani and Neumann2019).

5. Empirical results

This section proceeds in two sub-sections. The first section presents the baseline regression results, while the second section presents the robustness check results.

5.1 Baseline results

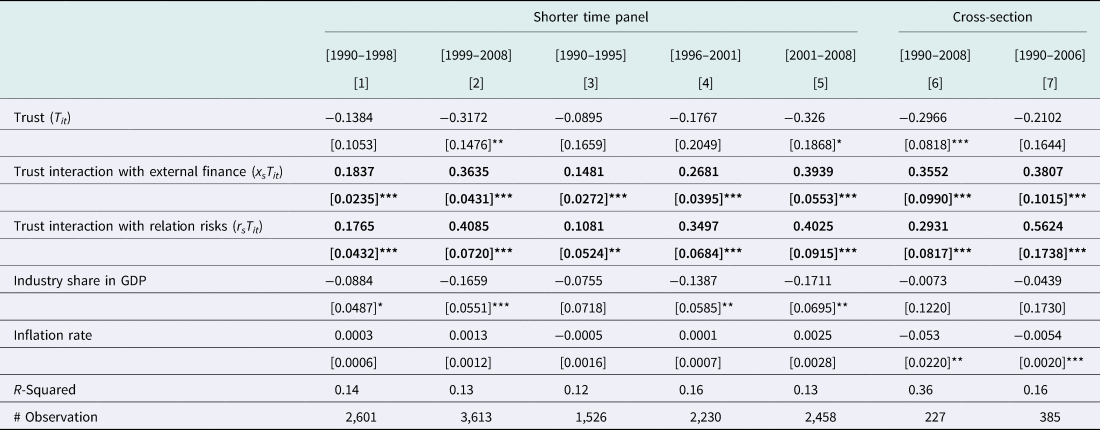

Table 1 displays the baseline result on the effect of social trust on R&D intensities. The dependent variable for each reported regression in the table is the industry R&D intensity. Before exploring the pathways linking social trust and R&D intensities, I first conduct a preliminary analysis by estimating the average effect of social trust on R&D intensities. Specifically, I regress industry R&D intensities on social trust, excluding the interaction terms comprising ‘social trust and industry external finance dependence,’ and ‘social trust and industry relational risks vulnerability.’ Column 1 shows the result. The coefficient estimate of social trust is positive and statistically significant at 1 percent. The magnitude of the coefficient estimate in the column suggests that a one standard deviation expansion in the social trust will increase R&D intensities by 1.07 percentage point.

Table 1. Trust and R&D investments: baseline results

* p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01.

Robust standard errors in squared brackets. Each column contains an unreported country, year, and industry fixed-effects.

This result is somewhat consistent with the existing literature, which documents a positive association between social trust and innovation (e.g. see Akçomak and ter Weel, Reference Akçomak and ter Weel2009; Doh and Acs, Reference Doh and Acs2009). However, it extends the literature by providing empirical evidence on the effect of social trust on R&D investments, which is an innovation input, other than using patent counts that have been the approach of previous studies. Along this line, the result contributes to the broader literature examining how social trust affects the real sector (Bjørnskov and Méon, Reference Bjørnsko and Meòn2015; Dearmon and Grier, Reference Dearmon and Grier2011; Zak and Knack, Reference Zak and Knack2001). This literature has analyzed the effect of social trust on productivity, financial development, and investments in physical and human capital. The result adds to this literature by underlining R&D investments as another pathway that social trust can affect the real sector.

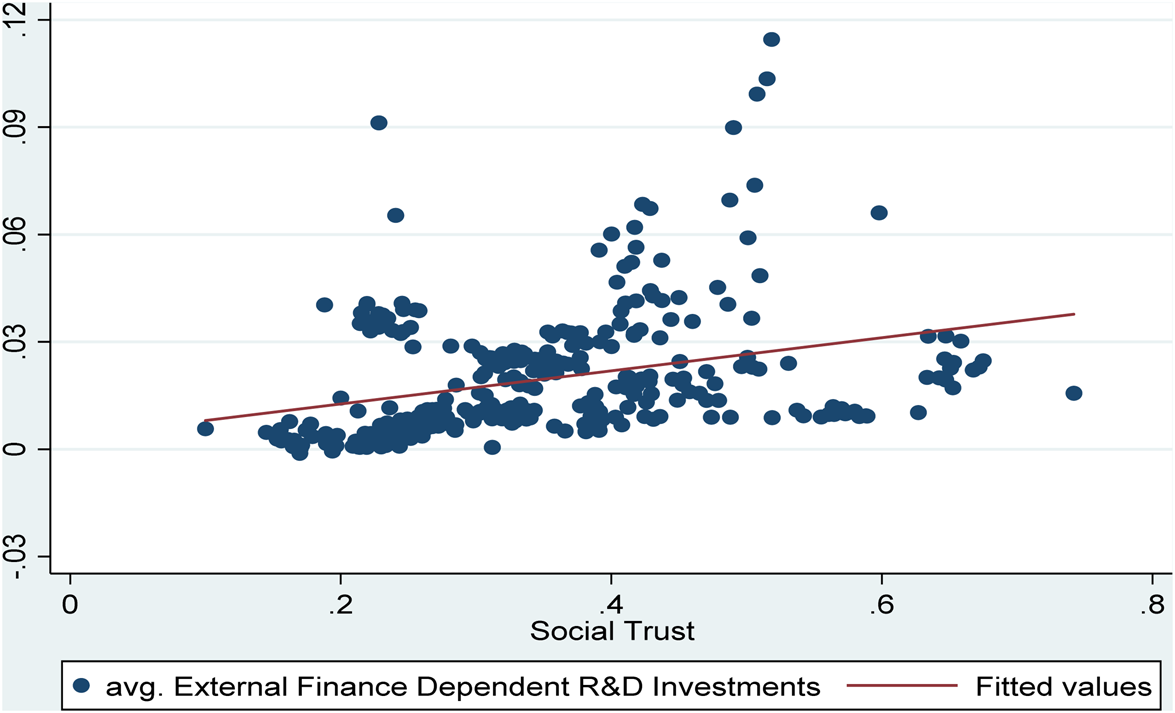

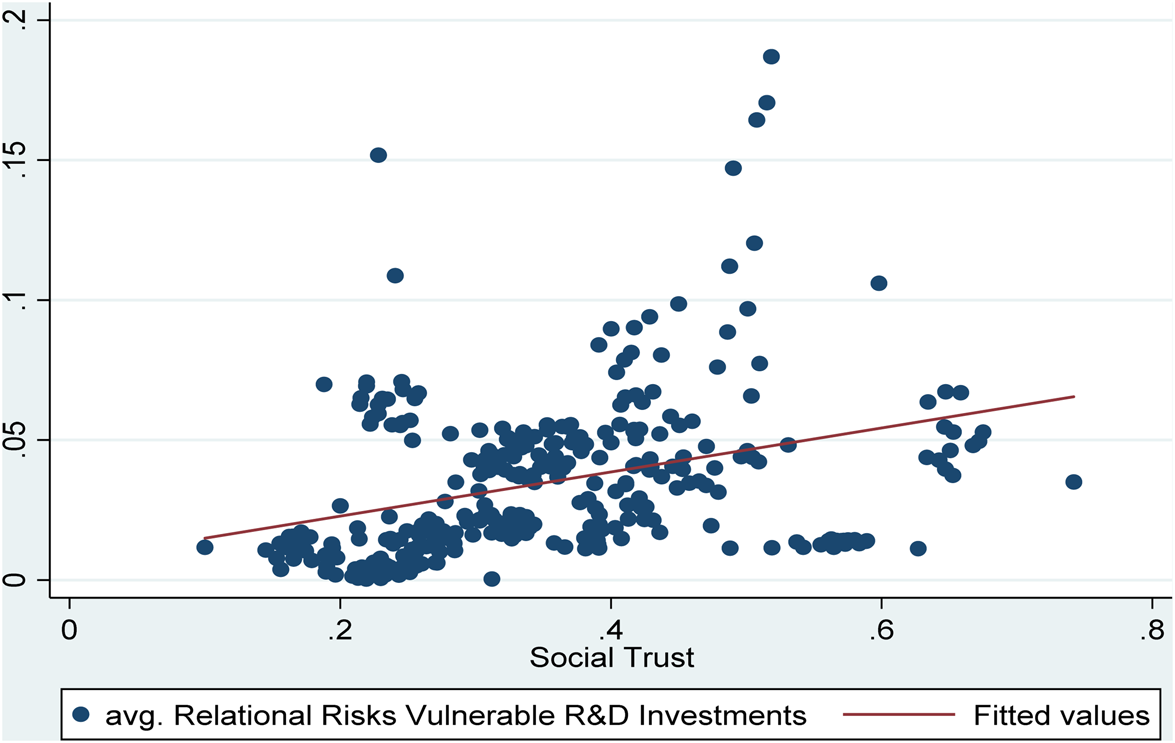

Next, to identify the two potential mechanisms through which social trust can affect R&D investments, I first provide some facts from the disaggregated industry-level data to offer basic insights. For this purpose, I calculate for each country in each year, its direct ‘external finance dependent R&D intensity’ and ‘relational risks vulnerable R&D intensity.’ The former is calculated as the share of each industry's R&D intensities for country i weighted by that industry's external finance dependence index. Similarly, the latter is calculated as the share of each industry's R&D intensities for country i weighted by that industry's relational risks vulnerability index. Figure 1 plots the average ‘external finance dependent R&D intensity’ against the social trust level for all countries in the dataset. Figure 2 repeats the same exercise, but this time focusing on the ‘relational risks vulnerable R&D intensity.’ The two graphs show a positive relationship between the variables examined. Figure 1 suggests that average ‘external finance dependent R&D intensities’ tend to be higher in trust-intensive countries, while Figure 2 suggests that average ‘relational risks vulnerable R&D intensities’ tend to be higher in trust-intensive countries.

Figure 1. Trust and ‘External Finance Dependent R&D Intensity.’ The graph shows the pattern between social trust and average ‘external finance dependent R&D intensities’ for 20 OECD member countries over the period spanning 1990–2008.

Figure 2. Trust and ‘Relational Risks Vulnerable R&D Intensity.’ The graph shows the pattern between social trust and average ‘relational risks vulnerable R&D intensities’ for 20 OECD member countries over the period spanning 1990–2008.

Turning now to the empirical investigation, Columns 2–5 of Table 1 report the results on the two mechanisms. I begin by regressing industry R&D intensities on social trust and its interaction with industry external finance dependence in Column 2 and exposure to relational risks in Column 3. In both columns, the coefficient estimates of x sT it and r sT it are positive and statistically different from zero at all conventional levels. These suggest that more external finance dependent and relational risk vulnerable industries experience a relatively faster increase in R&D intensities in trust-intensive countries. In Column 4, I jointly include both interaction term variables in a single regression and find that the initial results still hold. Importantly, the estimated coefficients of the interaction terms enter with the same statistical significance level and almost the same magnitude as when included one at a time. This suggests that the two interaction terms identify distinct economic mechanisms through which social trust affects R&D intensities. The result on the interaction term comprising social trust and external finance dependence is consistent with the underlying argument that higher levels of social trust reduce a firm's cost of external capital, which impedes access to credit. On the other hand, the result on the interaction term comprising social trust and industry relational risk vulnerability is consistent with the argument that social trust mitigates ex-post holdups or outright intellectual property expropriation that can discourage a firm's research efforts.

The results are also economically meaningful. Based on the coefficient estimates of x sT it and r sT it in Column 4, a one standard deviation expansion in the social trust will increase R&D intensities by 1.5 percentage point for an industry at the average external finance dependence (0.254) and by 4.8 percentage point for an industry at the average relational risk exposure (0.48). Taking into account the cross-country variations in social trust, the result further suggests that, the R&D intensity for an industry at the average external finance dependence will increase by 2.16 percent in a country with social trust level at the 75th percentile (0.417) compared to a country with social trust level at the 25th percentile (0.246). In the same way, the R&D intensity for an industry at the average relational risk exposure will increase by 6.86 percent in a country with a social trust level at the 75th percentile compared to a country with a social trust level at the 25th percentile. To provide further context, consider moving from a country at the 75th percentile of social trust level to a country at the 25th percentile. This will widen the gap in R&D intensities between the industries on the 25th (ISIC 21 – Paper & Paper Products) and 75th (ISIC 32 – Radio, TV & Communication Equipment) percentiles of external finance dependence by 1.75 percent. Similarly, it will widen the gap in R&D intensities between the industries on the 25th (ISIC 18 – Wearing Apparel and Fur) and 75th (ISIC 33 – Medical, Precision, and Optical Instruments, Watches and Clocks) percentiles of relational risk exposure by 5.86 percent.

5.2 Robustness checks

The baseline results support the hypothesis that ‘more external finance dependent and relational risks vulnerable industries experience higher R&D intensities in trust-intensive countries compared with those industries in low-trusting countries.’ This section conducts some robustness checks on the mechanisms linking social trust and R&D investments. To conserve space, I will only report coefficients that are reported in the baseline result.Footnote 6

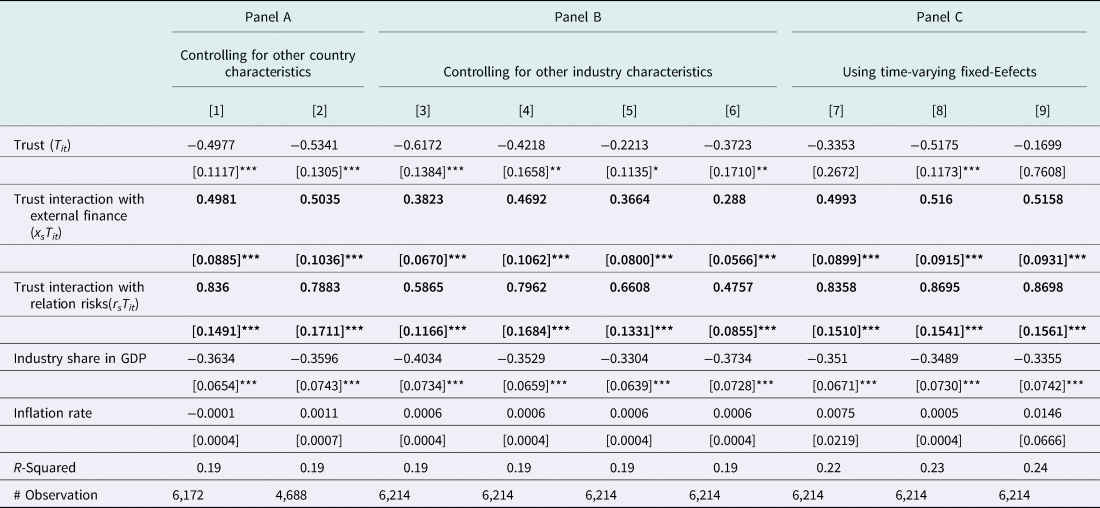

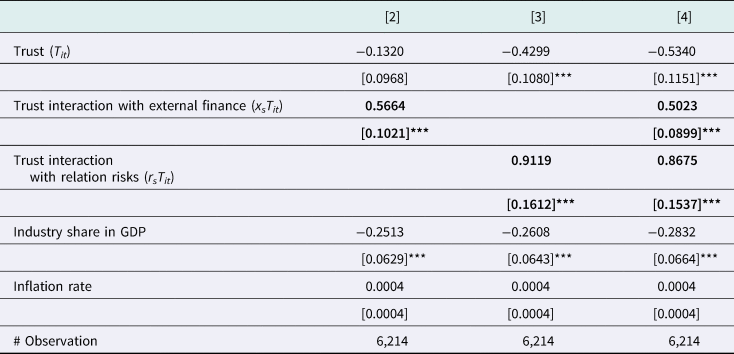

5.2.1 Additional control variables

As argued elsewhere (Kroszner et al., Reference Kroszner, Laeven and Klingebiel2007; Rajan and Zingales, Reference Rajan and Zingales1998), the empirical approach adopted in this paper is less susceptible to omitted variable bias or model misspecification due to the battery of country, industry and year fixed-effects that are controlled for in the model. However, to ensure that other confounding factors do not drive the baseline result, Table 2 displays the results when I account for additional control variables both at the country and industry level. Panel A emerges when I control for additional country-level variables. Column 1 controls for patent rights protection, financial development, and human capital, while Column 2 further controls for formal institutional quality using the rule of law index. Because of missing observation on some countries' patent rights protection indicator, the observation in Column 1 falls to 6,172 from its previous value of 6,214 in Table 1. Also, due to the lack of observations on the rule of law index between the periods 1990–1995, the number of observations in Column 2 falls to 4,688 from its previous value of 6,172 in Column 1. Notwithstanding, the coefficient estimates of x sT it and r sT it are consistently positive and statistically different from zero in Columns 1 and 2. The results are consistent with those reported in the baseline result in suggesting that more external finance dependent and relational risk vulnerable industries experience higher R&D intensities in trust-intensive countries compared with those industries in low-trusting countries.

Table 2. Trust and R&D investments: controlling additional variables

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Robust standard errors in squared brackets. Columns 1–6 contain unreported country, industry, and year fixed effects. Column 7 contains unreported industry, year, and time-varying country fixed effects. Column 8 contains unreported country, year, and time-varying industry fixed effects. Column 9 contains unreported year, and time-varying country and industry fixed-effects.

While the analysis so far focuses on industry external finance dependence and relational risks as two pathways social trust can affect R&D intensities, it may well be that either of these characteristics correlates with other industry characteristics. If this is the case, the baseline result will be spurious. Accordingly, Panel B emerges when the social trust indicator is interacted with other industry characteristics such as skill intensity (Column 3), asset tangibility (Column 4), and capital intensity (Column 5). These serve to isolate the two mechanisms from any other potential channels through which social trust may be exerting an influence on R&D intensities. Column 6 jointly controls for these additional industry characteristics that are interacted with social trust. In all cases, the coefficient estimates of x sT it and r sT it are positive and statistically significant at one percent. These results are thus in line with the baseline result.

Finally, Panel C emerges when I use more severe fixed effects to capture potential omitted time-varying variables at the country and industry level. Column 7 replaces country fixed-effects with country-year fixed-effects to control for country time-varying factors that may affect R&D intensity. In contrast, Column 8 replaces the industry fixed-effect with industry-year fixed effects to control for potential influences of time-varying industry factors on R&D intensities. Column 9 jointly controls for both time-varying country and industry fixed-effects. In Columns 7–10, the coefficient estimates of x sT it and r sT it are consistently positive and statistically significant at one percent. The result is, therefore, consistent with the baseline results and conclusion.

5.2.2 Is the effect of social trust distinct from other country characteristics?

The social trust level in a country may capture other characteristics of a country, such as the overall economic development or quality of formal institutions. To investigate whether the relationship I find is distinct from any other country or industry characteristic, I interact a variety of other country and industry characteristics with the industry external finance dependence and relational risks vulnerability indexes. The results for this exercise are reported in Table 3. I begin by including two interaction terms comprising ‘industry share in GDP and industry external finance dependence’ and ‘industry share in GDP and industry relational risks vulnerability’ in Column 1. Column 2 includes two interaction term variables comprising ‘inflation rate and industry external finance dependence’ and ‘inflation rate and industry relational risks vulnerability.’ In both cases, the coefficient estimates of x sT it and r sT it continue to be positive and statistically different from zero.

Table 3. Trust and R&D investments: distinguishing the effect of trust

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Robust standard errors in squared brackets. The columns contain unreported year, country, and industry fixed effects.

Next, Column 3 includes two interaction terms comprising ‘financial development and industry external finance dependence,’ and ‘financial development and industry relational risk vulnerability.’. The interaction terms are introduced to isolate the effect of social trust that may be driven by a country's level of (formal) financial development.Footnote 7 Column 4 includes two additional interaction terms comprising ‘the rule of law indicator and industry external finance dependence,’ and ‘rule of law indicator and industry relational risk vulnerability.’ This serves to isolate the effect of social trust level from picking any effect that may be driven by the formal contracting institutional quality. Column 5 includes two additional interaction terms comprising ‘per capita GDP and industry external finance dependence’ and ‘per capita GDP and industry relational risk vulnerability.’ The income per capita is used here as a catch-all term for a country's level of development. Hence, the included interaction terms serve to isolate the effect of social trust that may be due to the overall development level of the country. Column 6 jointly includes the interaction terms in columns 3–5. In all the columns, the coefficient estimates of x sT it and r sT it continue to be positive and statistically different from zero and are therefore consistent with the baseline results.

5.2.3 Different samples

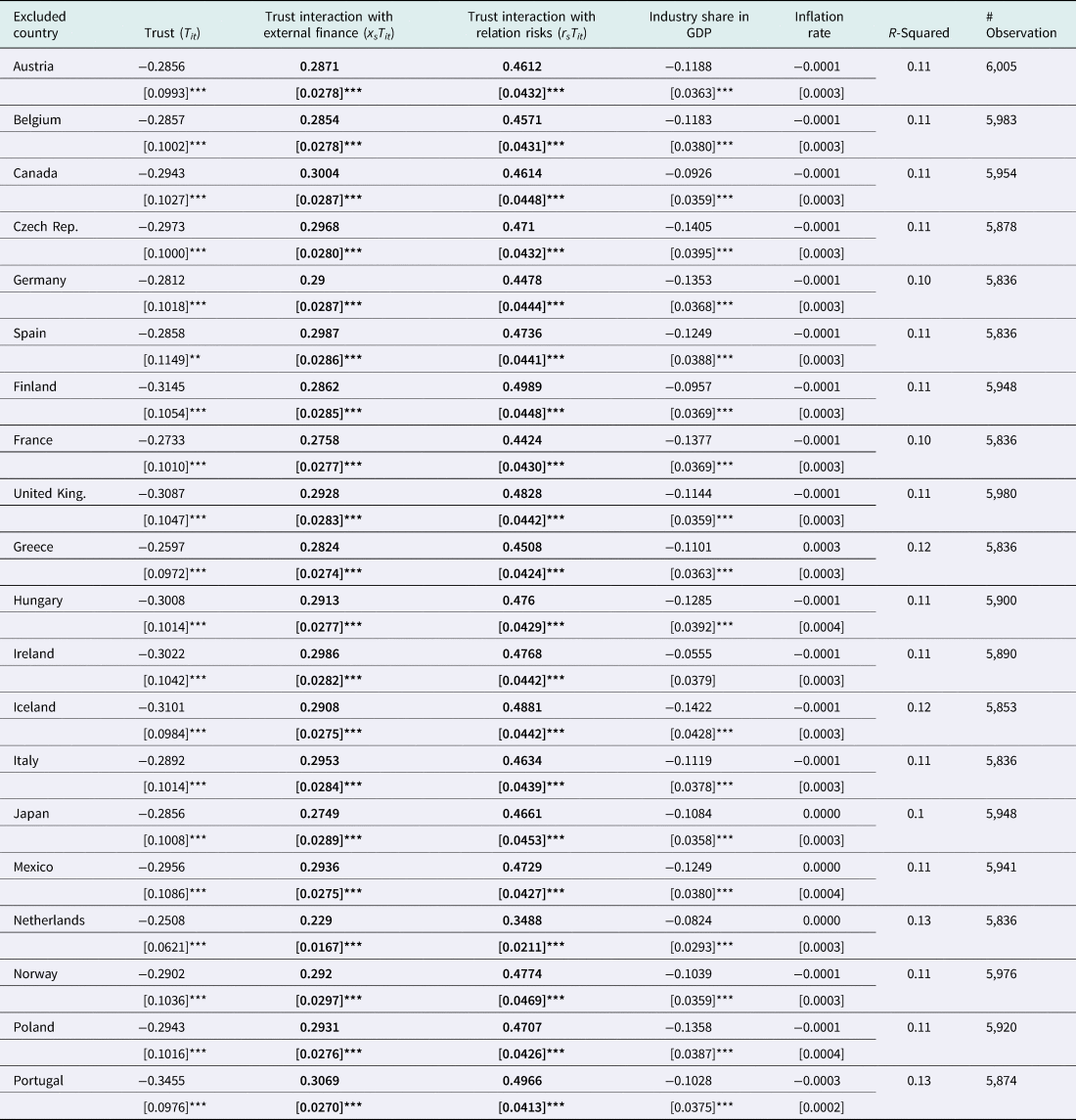

This section tests the robustness of the baseline result to changes in the sample. I begin by testing whether any particular country drives the result in the sample. To this end, I perform 20 different regressions, excluding one country at a time. Table 4 reports the result of this exercise. Each row represents an independent regression. The column titled ‘excluded country’ indicates the country that was excluded when performing the regression. In each case, the coefficient estimates of the variables of interest continue to be positive and statistically different from zero, which are consistent with the baseline result. Therefore, these results further suggest that any specific country effect does not drive the baseline result. It is also reassuring that the results are not influenced by the few missing observations we filled-up using linear interpolations.

Table 4. Trust and R&D investments: testing for country effect

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Robust standard errors in squared brackets. The rows contain unreported year, country, and industry fixed effects.

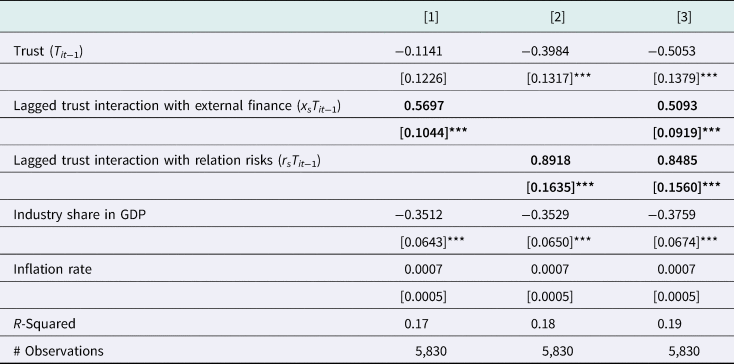

Next, I divide my sample into two using the mid-year, 1999, as the cut-off and reevaluate the effect of social trust on R&D intensities. Columns 1 and 2 in Table 5 report the results for the two periods: 1990–1999 and 1999–2008. Secondly, I divide the sample into three non-overlapping periods: 1990–1995, 1996–2001, and 2001–2008. Columns 3–5 in Table 5 show the results of this exercise. In all cases, the coefficient estimates of x sT it and r sT it. continue to be positive and statistically different from zero at all conventional levels. These results suggest that the baseline result is time-independent.

Table 5. Trust and R&D investments: shorter time panel and cross-sectional analysis

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Robust standard errors in squared brackets. The columns contain unreported year, country, and industry fixed effects.

So far, the analysis used panel data. More so, a longer panel data series was achieved by filling in some missing observations for the data on R&D intensities. To ensure that the results are neither artifacts of the panel structure of the data nor driven by the few missing observations which were filled-up,Footnote 8 I transform the data into a time-invariant cross-sectional data by taking the sample averages. I achieve this in two ways. First, I take the averages of the variables over the periods 1990–2008. Second, because some countries in the sample do not have observations in 2008, I also take the averages of the variables over the periods 1990–2006. Columns 3 and 4 report the results of this exercise. In both columns, the initial results remain unchanged.

5.2.4 Zero censoring

The empirical analysis so far used the OLS to estimate the baseline equation. However, as can be observed in Table A1, the minimum R&D intensity for some countries is zero, which may lead to bias due to zero censoring. To ensure that this bias does not drive my baseline result, Table 6 reports the result when I re-estimate the baseline equation using the Tobit model, which is censored at zero. Collectively, the results are not different from those reported in Table 1 in qualitative terms.

Table 6. Trust and R&D investments: Tobit model

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Robust standard errors in squared brackets. The columns contain unreported year, country, and industry fixed effects. Note that results are not marginal effects.

5.2.5 Endogeneity

Until now, the empirical analysis has been silent about the endogeneity issue. This is because I do not consider it a concern in my model. As noted in section 5.2.1, the adopted empirical approach reduces potential endogeneity problems. Among others, this is due to the battery of industry, country, and year fixed-effects the model allows. Also, section 5.2.1 controlled for the time-varying industry and country factors, which further addresses concerns of omitted variable bias. Secondly, while it is clear from the analysis that R&D intensities are affected by the social trust level, it is unlikely that social trust at the country level would be affected by R&D intensities at the 2-digit industry level.Footnote 9 This alleviates any concern of reverse causality. A competing argument here would be that through repeated interactions, such as R&D collaboration, norms of trust, and reciprocity are formed. While this argument is compelling, it is unclear whether this would transform into a nationwide trust since not all R&D activities can impact on social trust, and for those that can, we are unsure about the direction of the impact (Xie et al., Reference Xie, Zhang, B. and Zhan2019).Footnote 10 Thirdly, the empirical approach adopted in the study traces out the effect of trust on R&D intensities by exploring exogenous variations in industry technological components which are interacted with the social trust level. Notwithstanding these, Table 7 reports the result when contemporaneous values of R&D intensities are regressed on a period lagged values of social trust. As can be seen in the table, the results in the columns are consistent with the baseline results.

Table 7. Trust and R&D investments: lagged values of trust

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Robust standard errors in squared brackets. The columns contain unreported year, country, and industry fixed effects.

6. Conclusion

There is a growing literature examining the effects of social trust on innovation activities. This paper contributes to this literature by evaluating two potential mechanisms – access to credit and reduction in relational risks – through which social trust can affect R&D investments. I test these mechanisms within the empirical framework developed by Rajan and Zingales (Reference Rajan and Zingales1998) by evaluating whether more external finance dependent and relational risks vulnerable industries experience higher R&D intensities in trust-intensive countries compared with those industries in low-trusting countries. The results provide robust evidence in support of the hypothesis: social trust influences innovation activities by easing access to external finance and reducing relational risks. Hence, the result underlines access to credit and a reduction in relational risks as causal pathways linking social trust and R&D investments.

This paper also makes a broader contribution to the literature examining the impact of trust on investment decisions but has mostly focused on investments in human and physical capital (e.g. see Dearmon and Grier, Reference Dearmon and Grier2011). The empirical analysis provides evidence on the effect of social trust on R&D investments, hence showing another way social trust can influence the real sector of the economy. From a policy perspective, the results underline the importance of social trust, as an informal contracting institution, in encouraging R&D investments, which are pivotal for income per capita and long-run productivity growth. Hence, the paper also contributes to the broader literature examining the effect of social trust on economic growth. Bjørnskov (Reference Bjørnskov and Uslaner2018) argued that social trust could affect economic growth by affecting: (i) the rate of innovation or productivity growth; (ii) the rate of factor accumulation; (iii) institutions and policies that in turn affect relevant growth factors; and (iv) the elasticity of substitution. This paper offers empirical support for the innovation channel.

Appendix

Figure A1. Trust variation over time

Table A1. Basic summary statistics

Table A2. Basic industry characteristics