On 14 January 1562, the third Mughal emperor Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar (r. 1556–1605) set off westward from the imperial city of Agra on a hunting expedition. It eventually took him to Ajmer. In this town in western India Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti (d. 1236), one of the earliest and most revered Sufi saints of South Asia, lies buried. Originally from Khurasan, Muinuddin had arrived in western India around the time of the Ghurid invasions at the close of the twelfth century. Since his death, his shrine in Ajmer had emerged as a major site of pilgrimage among Muslims as well as Hindus. By the fourteenth century, it had started attracting important sultans and Sufis, who undertook difficult overland journeys to offer prayers to the Sufi master.Footnote 1 During his trip to Ajmer, the Mughal emperor visited the dargāh, offered his prayers to the Sufi, and distributed alms and other gifts among the people there.Footnote 2 As it turned out, this would be the first of his many visits to the shrine; in the 18 years between 1562 and 1579, he would visit Ajmer as many as 17 times. Instead of treating these pilgrimages as mere acts of piety, which has been the conventional way of interpreting them, this article highlights their importance as a site for the performance of kingship and as a mechanism of empire formation. It points out that aside from allowing the young emperor to publicly legitimise his rule through Islamic markers of power and authority, the visits to Ajmer also allowed him to forge alliances with local chieftains, participate in fresh military campaigns, consolidate imperial control over central and western India, carry out important functions of surveillance and governance, and perform various symbolic aspects of peripatetic kingship in a public setting. In all, the pilgrimages played a central role in the making of the Mughal Empire under Akbar—something that has not been adequately recognised by historians so far.

The conventional treatment of these pilgrimages as acts of piety has resulted in their analysis mainly in relation to the changing religious environment at Akbar's court. In one of the first discussions on the subject, Iqtidar Alam Khan interpreted them as a manifestation of the emperor's religious conservatism during the 1560s and 1570s. According to Khan, this was primarily aimed at placating the Indian Muslim chieftains whose numbers were increasing in the Mughal official ranks during this period. This public display of devotion to Islam, he pointed out, was matched by Akbar's military hostility against the Hindu Rajput groups of western India. Yet, a major rebellion by a part of the Muslim nobility in 1580–1581 revealed that the emperor's efforts at projecting himself as a champion of the Muslim communities had failed. For Khan, this prompted a subsequent shift in imperial ideology, marked by a move away from Islam towards a more universalist conceptualisation of imperial authority.Footnote 3 Muzaffar Alam situates the pilgrimages within the larger context of Akbar's interactions with various Sufi groups and the formation of the ‘Akbari dispensation’. More specifically, he interprets these visits as a manifestation of the emperor's proximity to the more heterodox Chishti Sufis during roughly the first half of his reign—something that he contrasts with his alignment with the more orthodox Naqshbandi Sufis during the second half.Footnote 4 More recently, Catherine Asher has briefly commented on the nature of piety and the charitable works of Akbar and his successors at and around the shrine of Muinuddin Chishti.Footnote 5 In a more detailed analysis, Motiur Rahman Khan highlights some of the important aspects of Akbar's pilgrimages. He argues that offering gifts and sponsoring new buildings at the shrine, as well as intervening directly in its administration, helped the emperor to emerge as the spiritual head of the place. In turn, this helped Akbar garner religious legitimacy for his reign.Footnote 6

In spite of this rich body of scholarship, historians are yet to fully appreciate the contribution Akbar's pilgrimages to Ajmer made in the larger process of Mughal empire-building. The existing body of literature overwhelmingly engages with the issue from the perspective of religion. Yet even this analysis of the religious dimensions of the pilgrimages is far from exhaustive. Some of the emperor's activities at the shrine and most of his actions in the course of his travels to and from Ajmer have gone unnoticed. The first two sections of this article address this historiographical lacuna, thereby contributing to our understanding of the pilgrimages as acts of piety. In the first section, I explore the nature and implications of the emperor's devotion, giving special attention to his actual journeys—especially those undertaken on foot, his acts of offering specific gifts derived from military campaigns at the shrine, and the issue of the performance of miracles. This discussion is complemented by the second section, which widens the scope of the present body of scholarship by situating the case of Ajmer within the wider sacred geography of Islam in early modern northwestern India. It analyses the significance of the fact that Akbar's pilgrimages to Ajmer were often preceded or followed by visits to other important Sufi shrines in Delhi, Pakpattan, and Nagaur as well as by the despatch of official ḥajj expeditions to the Islamic Holy Lands in the late 1570s.

Going beyond the existing historiography, I further argue that although they were spectacular demonstrations of imperial devotion to Islam, this does not fully explain the importance of these pilgrimages. By acting as important means of bringing about territorial expansion and imperial consolidation as well as performing kingship in all its complexities, these pilgrimages were, in fact, a form of statecraft and governance. These political, military, and performative dimensions of the pilgrimages remain largely unexplored until now, and this is what the next two sections of the article analyse. The first among these discusses the geopolitical importance of Ajmer. It shows how the emperor's frequent visits to the town were a means of conducting military operations in and strengthening imperial hold over western and central India. It also discusses the strategic role Ajmer played in the geopolitics of the ḥajj expeditions. The next section takes a close look at his various actions in the course of his travels to reflect on the role of imperial mobility as a means of performing various material and symbolic functions of rulership. It discusses how this form of mobility was a way for the sovereign to explore the realms, forge political alliances, produce infrastructure, improve the conditions of the subjects, bring his governance close to the people, and project himself as a caring, just, and powerful monarch.

The final section of the article addresses the question of why the pilgrimages stopped abruptly in 1579. I explain this in terms of a paradigmatic shift that took place around 1580 in the empire's strategic priorities as well as Akbar's conceptualisation and performance of kingship. In a new paradigm of kingship inaugurated around 1580, the relationship between political power and faith was redefined; kingship itself became sacred, millennial, and universal. I argue that it was because of this shift that public displays of devotion by the sovereign—like his visits to the Ajmer shrine—lost their relevance as legitimisers of royal power. Overall, the main argument that runs through the article is that the emperor's frantic pilgrimages to Ajmer in the 1560s and 1570s were central not just to his engagements with religion, but also to the larger processes of the formation of empire and the production of kingship. As spectacular acts of piety, they enabled the young emperor to derive legitimacy from the embodied charisma of the Sufi master and to cast his own image as a pious Muslim king. His acts of devotion in and around the shrine—like undertaking pilgrimages to other Sufi shrines, meeting living saints, and sponsoring ḥajj expeditions—contributed to this process. At the same time, the pilgrimages to Ajmer also facilitated imperial governance, military expansion, building of alliances, and the public performance of sovereignty. All this helped Akbar seal his reputation as a military leader and an able ruler. Away from the imperial cities, they comprised a complex form of peripatetic kingship that the Mughals came to master in early modern South Asia, one that fused various material and symbolic functions of monarchy into one complex and dynamic—yet seamless—performance.Footnote 7

Pilgrimage, piety, and the making of an imperial shrine

Interactions between Sufis and Muslim kings in South Asia date back to the early thirteenth century, which saw both the migration of the first Sufis to and the rise of political Islam in the subcontinent. Several prominent Sufi masters (mashā’ikh) appeared in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and their tombs subsequently became important centres of devotion and pilgrimage. During their lifetimes, major Sufi saints often shared complicated relationships with reigning sultans. On the one hand, sultans would be anxious to assert their temporal power as the source of governance, justice, and patronage, while on the other hand, Sufis would be intent on demonstrating their spiritual power through acts of miracle-performance and renunciation. Desirous of imposing their authority over the same territory (wilāyat), their interactions were often marked by ambivalence at best and public antagonism at worst during this period. This was especially true of the Chishti Sufis. Instances of royal pilgrimages to Sufi shrines were rare.Footnote 8

However, by the late fourteenth century, Amir Timur Gurgan—the Turkish warrior-conqueror ancestor of the Mughals—started widely sponsoring Sufis and their shrines in post-Mongol Central Asia. Timur subjugated his power to the spiritual authority of Sufi shaikhs; the latter, especially that of the Naqshbandi Sufis, were one of the main sources of his legitimacy as a Muslim monarch. The descendants of Timur continued this tradition of venerating and patronising Sufi shaikhs—especially the Naqshbandi Sufis—in the fifteenth century.Footnote 9 Following their relocation to North India, the Timurids under Babur (r. 1526–1530) continued the tradition of patronising Sufis, but gradually shifted their focus away from the Naqshbandis, who were more popular in Turan and Khurasan. Instead, Humayun (r. 1530–40, 1555–56) extended his support and devotion to the Shattari silsila, which had a strong presence in North India.Footnote 10 Under Akbar, the focus of this patronage shifted again and centred—especially during the first half of his rule—on the Chishti order. His pilgrimages to and patronage of the shrine of Muinuddin Chishti in Ajmer needs to be understood in the context of the markedly increased importance of Sufi shrines in the early modern world. Within South Asia, Sufi masters who had once competed with sultans over matters of authority and power were long dead; by the sixteenth century, their shrines emerged as major sites of pilgrimage and centres of royal patronage.Footnote 11 In the contemporary Safavid and Ottoman empires too, patronising major Sufi shrines became an integral part of imperial culture. Akbar's devotion to the Ajmer shrine was hence not an exception; rather, it exemplified a tendency common to most early modern Islamicate polities in Asia in terms of the relationship between royal power and spiritual authority.Footnote 12

For Akbar, the pilgrimages to the Ajmer shrine marked one of the many forms of his engagements with the Chishti order.Footnote 13 Upon his triumphant entry into Delhi, Babur had already made pilgrimages to the Chishti shrines of Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki and Nizamuddin Auliya in that city. As for Akbar, associating himself with the Chishti silsila was driven by the great popularity of this order in South Asia and the prospect of projecting himself as an ideal Muslim monarch in the South Asian context by his association with this particular order.Footnote 14 In 1562, he visited the dargāh of Muinuddin Chishti for the first time. A few years later, he came in contact with Shaikh Salim Chishti, a living saint of the same order, in the village of Sikri near Agra. Desirous of a son, Akbar prayed to Salim Chishti, who blessed the emperor with offspring. When Akbar's first son was born shortly thereafter, he named him Salim in thanksgiving to the saint. He later named another son Danyal, after Shaikh Danyal, a khādim (religious functionary) at the Ajmer shrine. Akbar also co-opted several living members of the Chishti family—mainly descendants of Salim Chishti—into the imperial household and officialdom. Some of these members eventually held important offices in the imperial administration and led Mughal armies in military campaigns.Footnote 15

All this occurred alongside the 17 pilgrimages to Ajmer in a span of 18 years. The choice of this particular Chishti shrine as the object of the emperor's devotion and patronage was probably guided by Muinuddin's unique aura as the progenitor of the silsila in South Asia. In addition, Bruce Lawrence argues that Akbar probably ruled out the three important Chishti shrines in Delhi because of the close association of that city with earlier Muslim rulers. Instead, he was interested in finding alternate centres of devotion close to his own political base—Agra. In a way, this was provided by his discovery of Salim Chishti at Sikri. After Salim's death in 1571, the emperor had a marble tomb constructed for the saint and built a new capital city named Fatehpur around it. Through Salim, the emperor also forged a connection with the former's spiritual predecessor—Baba Farid of Pakpattan, another venerated Chishti saint. It was in this context that Lawrence explains Akbar's devotion to the Ajmer shrine as one that was close to both Agra and Fatehpur Sikri and that allowed the emperor to harness the embodied spiritual sovereignty of Muinuddin Chishti.Footnote 16 To this, one can add that keen as he was on expanding the frontiers of his fledgling domains southward and westward, Akbar probably found Ajmer a convenient base for future military operations in western and central India. I will discuss soon how the pilgrimages to Ajmer indeed helped the emperor expand his empire and consolidate his authority in these parts. These strategic considerations too must have had a role in the selection of the shrine.

In the course of the pilgrimages, the emperor's piety was manifested in two main ways—his journeys to Ajmer and his actions at the dargāh. As to the first, the aspect that commanded the greatest symbolic significance was that the emperor would usually cover at least a part of the journey on foot. This was to demonstrate his complete submission to the spiritual authority of the Sufi master. In 1568, following the conquest of Chitor, Akbar walked the entire distance from Chitor to Ajmer in fulfilment of a vow he had made at the outset of the siege.Footnote 17 In 1570, he walked from Agra to Ajmer on foot as thanksgiving for the birth of his first son.Footnote 18 While such instances of walking the entire way were uncommon, from 1572 onwards Akbar established a tradition of covering at least the last stage of the journey of foot. For instance, in early 1574, he rode from Fatehpur Sikri towards Ajmer. He encamped 12 karohs away from Ajmer and walked the remaining distance.Footnote 19 A remark by Arif Qandahari, a contemporary chronicler, indicates that it might have been expected—and indeed customary—for the members of the Mughal nobility to walk this distance alongside the emperor.Footnote 20 In many cases, the chroniclers mention Akbar going to the shrine directly from the road, his body still dusty and grimy from his journey.Footnote 21 Because of the number of times such descriptions figure in the chronicles, this—both as a physical act and as a literary device—seems to be a trope to demonstrate the total subjugation of imperial power to Sufi authority.

The high level of devotion symbolised by the emperor's pilgrimage on foot was also reflected in the occasional snide remark that his actions elicited. The description of such an incident comes from Abdul Qadir Badauni, a contemporary observer who himself was a conservative Sunni Muslim and a harsh critic of what he saw as Akbar's heretical experiments with religion. Narrating the emperor's journey to Ajmer in 1579, Badauni says:

On the 25th of Shaban, at the distance of five kos from the town, the Emperor alighted and went on foot to the tomb of the Saint [Muin-ud-din]. But sensible people smiled and said, It was strange that His Majesty should have such a faith in the Khwajah of Ajmir, while he rejected the foundation of everything, our Prophet, from whose ‘skirt’ hundreds of thousands of saints of the highest degree like the Khwajah had sprung [sic].Footnote 22

It is impossible to tell if this sarcasm at Akbar's ostensible neglect of the Prophet and his simultaneous displays of devotion to a Sufi was indeed a remark made by orthodox Muslim members of the emperor's entourage or a masked personal criticism by Badauni himself. Either way, it was symptomatic of the scepticism in the conservative circles around the sincerity of Akbar's public demonstrations of Muslim piety and displays of devotion for heterodox ascetics. This kind of failure to establish himself as a pious Muslim monarch might have contributed to the emperor refashioning his imperial ideology from 1580 onwards.Footnote 23

The public display of piety on the road was complemented by equally spectacular acts of religiosity in Ajmer. Circumambulating the shrine was one of the routine ways of displaying piety. Another means of demonstrating his devotion was the frequency of Akbar's visits to the dargāh during his residence in the town: he often undertook these visits on a daily basis. Qandahari mentions that during his visit in 1570, ‘[T]he keepers of the shrine were asked to read the Fatiah [sic]’, presumably in the name of the emperor.Footnote 24 Akbar also sponsored the construction of religious buildings in Ajmer as a means of displaying his commitment to the welfare of the shrine. For instance, in 1569, he ordered the construction of the red sandstone mosque, known today as the Akbari Masjid.Footnote 25 Finally, offering gifts was another way of displaying both the submission and power of the Mughal monarch at the dargāh. On the first count, offering gifts to the Sufi master comprised an act of devotion. The submission of gifts in this case symbolised subversion of the giver's authority to that of the recipient. This mirrored the way in which Mughal commanders expressed their submission to the emperor by offering him gifts by way of nazr and pīshkash.Footnote 26 But on the second count, this act was also one of the emperor projecting himself as a benevolent paternalist benefactor, especially to the functionaries and devotees of the shrine. It was perhaps also an occasion for the emperor to publicly display his wealth and allow others to partake in it. In both Akbar's actual actions at Ajmer and their narration in contemporary chronicles, one can discern these two different but related meanings of the act of him offering gifts at the dargāh.

Aside from the alms and gifts in general, imperial offerings also included objects that carried special significance as political symbols. For instance, the emperor presented a brazen cauldron on his visit to the shrine in 1568 following his capture of the fort of Chitor.Footnote 27 Commemorating his victory over the Sisodiyas of Mewar at this siege, this cauldron was designated as the dīg-i Chittor kūshā (Chitor-conquering mortar).Footnote 28 Before the commencement of the siege, Akbar had made a vow. As mentioned earlier, he walked from Chitor to Ajmer in fulfilment of this vow following the success of the siege. First his journey on foot, then the prayers at the dargāh, and finally the offering of the cauldron together comprised Akbar's thanksgiving to the Sufi master for the military success.

Another similar example comes from 1576, when the emperor visited Ajmer for thanksgiving for Mughal success against the Afghan chieftain Daud Khan Karrani. Before the commencement of the campaign, the emperor had visited the shrine in 1574 to pray for its success. Upon his visit in 1576, he presented Daud's kettledrums—a symbol of the now-vanquished chieftain's political power—at the shrine. Nizamuddin mentions that Akbar had kept these kettledrums aside from the rest of the spoils of this campaign as a tribute to the Khwaja.Footnote 29 Since kettledrums were counted as a marker of political power, prestige, and even sovereignty, their seizure amounted to an act of political subversion of Daud. Akbar's submission of his kettledrums at Ajmer signified the further subjugation of the power of the Afghan chieftain to that of the Sufi master, with whose blessing the Mughal Empire seemed to be expanding at this point. Articulating this last point, Nizamuddin writes that Khwaja Muinuddin ‘always had given help and victory to this fortunate badshah [Akbar], who had always been helped by God’.Footnote 30

One of the foundations of the spiritual authority of Muinuddin in particular and Sufi shaikhs in general is the ability to perform miracles (karāmat) and foresee the future (firāsat).Footnote 31 Yet, even as Akbar submitted himself completely to the authority of Muinuddin, he himself started embodying these qualities over time.Footnote 32 Let us consider one example. Nizamuddin mentions that, following his visit to Pakpattan in 1577, Akbar's entourage was plagued by excessive rains. To remedy this, the emperor got himself a mirror, exhaled on it three times, and then put the mirror on the fire.Footnote 33 This immediately stopped the rain. Soon after this, the sound of a kettledrum was heard. Without knowing the source of this noise, Akbar said that it was Yar Muhammad Naqqarchi who was beating the drums. Nizamuddin notes with astonishment that this prediction was verified.Footnote 34 Under Akbar, the embodiment of such supernatural and mystical qualities became an increasingly integral part of the vocabulary of Mughal sacred kingship. In as much as the emperor subverted his own authority to Sufi power in the pursuit of legitimacy, imperial power gradually came to legitimise itself by embodying the attributes of Sufi authority.Footnote 35

Overall, religion is undoubtedly one of the primary categories that help us understand the meanings of Akbar's pilgrimages to Ajmer. However, as this section shows, matters were more complex than simply the emperor trying to garner support of orthodox Muslim sections of his aristocracy by showing his devotion to the Sufi saint. Akbar's actions en route to Ajmer as well as at the dargāh highlight the performative aspects of Mughal kingship, where both gestures and actions in the real world and their representation in the literary domain legitimised—and even produced—rulership. They also give us important insights into the military culture of the times, where the military success of the emperor came to be seen as a product of the blessings of Muinuddin Chishti in particular and Sufi masters in general. However, to fully comprehend the religious significance of these pilgrimages, we need to look at the Ajmer shrine not in isolation, as scholars have often done in the past, but situate it within the broader sacred geography of Islam in the northwestern part of South Asia. It was not the isolated importance of Ajmer, but rather its embeddedness within this larger sacred geography that helps us appreciate the religious meanings and functions of the emperor's journeys and actions. It is the nature of this embeddedness that the following section explores.

Sacred geography and Islamic kingship

Akbar's journeys to and from Ajmer reveal a multipolar network of religious sites, of which the shrine of Muinuddin was the nodal point. Interestingly, most of these sites housed important Sufi dargāhs of the Chishtiyya order. I have already mentioned Akbar's discovery of Shaikh Salim Chishti in the village of Sikri, about 35 kilometres outside his capital city in Agra. Following the saint's death in 1571, Akbar built a marble mausoleum for him at Sikri. He then erected an entire palace complex around that mausoleum. Complete with a huge congregational mosque, a massive gateway (Buland Darwaza) facing an impressive staircase, extensive residential quarters, and administrative buildings, this was Fatehpur Sikri—Akbar's ‘city of victory’. It served as Akbar's primary imperial base from 1571 to 1585. This was a remarkable amalgamation of imperial might and Sufi charisma.Footnote 36 During most of the 1570s, this site served as the starting point of Akbar's pilgrimages to Ajmer and often also the final destination of his journeys. Straddling the political and spiritual realms, Fatehpur hence occupied a unique place in Akbar's empire.

Another prominent site in this geography was Delhi. Akbar visited the city at least five times—in 1569, 1570, 1576, 1577, and 1578—on his way to or from Ajmer. As the erstwhile political centre of Turkish and Afghan sultanates of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the city had an enormous political aura even during the sixteenth. For Akbar, however, the attraction was mainly spiritual. The city houses three major Chishti Sufi shrines from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries: those of Shaikh Bakhtiyar Kaki, Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya, and Shaikh Nasiruddin Chiragh-i Dehli. Mughal texts somehow do not mention these shrines specifically while narrating Akbar's visits to Delhi, but allude in general to the emperor visiting such tombs during his trips to the city. He would also visit the monumental tomb of his father Humayun, which was built with imperial patronage throughout much of the 1560s. Its construction near the dargāh of Nizamuddin Auliya highlighted the spiritual association that the emperor was given in his afterlife. What is remarkable is the way in which contemporary writers narrate Akbar's visits to the Sufi shrines and the tomb of his father in one breath, even using the same word zīyārat (pilgrimage) to describe these journeys.Footnote 37 For the emperor, the journey itself to Delhi—or as contemporary texts often call it, Hazrat-i Dehli—was an act of pilgrimage, one that comprised smaller individual pilgrimages to the different sacred sites of Sufi spirituality and dynastic memory.

Alongside the lavish imperial urban setting of Delhi, two small towns attracted the emperor during these pilgrimages. One was Pakpattan, located in Punjab at a distance of a little more than 200 kilometres from Multan. It was the site of the dargāh of the thirteenth-century Chishti saint Shaikh Fariduddin Ganjshakr, or Baba Farid. During the years under focus here, Akbar went to Pakpattan twice, once in 1570 and again in 1577. In 1570, he went there from Ajmer and on to Lahore afterwards.Footnote 38 In 1577, he travelled to Pakpattan from Ajmer, and headed to Agra thereafter.Footnote 39 On both occasions, he visited the shrine, offered his prayers, and distributed gifts among those present. Qandahari says that when Akbar reached Pakpattan on 27 February during the second visit, a group of Muslim scholars from the imperial entourage kept vigil with him throughout the night.Footnote 40 The other major Chishti shrine that also featured twice in the emperor's pilgrimages during this period was that of Shaikh Hamiduddin Nagauri in Rajasthan. In late 1570, the emperor travelled to Nagaur directly from Ajmer, going to Pakpattan thereafter. In mid-1572, he visited Nagaur again, this time also from Ajmer and travelled in the direction of Gujarat afterwards. Contemporary sources mention him praying and distributing gifts at the shrine both times.Footnote 41

Other towns and holy men of somewhat lesser stature also figured in the course of Akbar's pilgrimages. When the emperor was stationed at Dair near Fatehpur in 1574, he was visited by Khwaja Abdush-Shahid, a grandson of the famous Naqshbandi Sufi Shaikh Nasiruddin Ahrar.Footnote 42 Nizamuddin finds it worthwhile to add that Akbar was extremely respectful towards the Khwaja and even gave him permission to ride straight into the palace without dismounting—the latter being the common way of showing respect to the emperor.Footnote 43 In 1568 and 1577, the emperor visited Shaikh Nizam at Narnaul.Footnote 44 In 1568, as his entourage proceeded from Ajmer to Agra by way of Mewat, he separated himself from the main camp and travelled to Narnaul to visit the Shaikh.Footnote 45 In 1577, he visited Narnaul again, this time on his way to Delhi from Ajmer. Badauni says that the Shaikh himself came out to meet the emperor. Nizamuddin Ahmad mentions that Akbar distributed many gifts to mark the occasion and that the assembled Sufis danced and entered into a state of mystical trance.Footnote 46 Passing through Punjab in 1577, Akbar stopped at Hansi, where he found the shrine of Shaikh Jamal Hanswi. He offered prayers and gifts at the dargāh.Footnote 47 Finally, in 1572, Akbar visited the tomb of Sayyid Husain Khing-sawar, a descendant of Imam Zainul Abidin and a possible disciple of Muinuddin, on the hill of Ajmer.Footnote 48

These various sites—Fatehpur, Ajmer, Delhi, Pakpattan, Nagaur, as well as the lesser shrines—together comprised an expansive and layered sacred geography of Sufi Islam in sixteenth-century northwestern India. Ajmer was the focal point of this network; no other shrine received as many visits from the Mughal emperor. Through his annual visits, demonstrations of piety, building activities, and—as I will discuss later in this article—taking over the administration of the dargāh, Akbar effectively converted the place into an imperial shrine. But at the same time, his visits to the other dargāhs demonstrated his larger commitment and devotion to Sufi Islam during this phase of his reign. All contemporary texts emphasise Akbar's charitable works at the shrines. Aside from the visits to the shrines, he also engaged in other public displays of his devotion to Islam. For instance, Qandahari records that during his visit to Delhi in 1576, Akbar offered prayers on the occasion of Id at an Idgah built by Tatar Khan.Footnote 49

There was one final piece in this sacred geography that we need to note—the Islamic Holy Lands. The later years of Akbar's pilgrimages to Ajmer coincided with his sponsorship of ḥajj expeditions from 1576 to 1580.Footnote 50 I discuss the strategic significance of these expeditions in the next section. Here, it suffices to say that during the second half of the 1570s, Akbar clubbed his acts of piety in and around Ajmer with a new display of devotion and magnanimity by arranging the imperial ḥajj expeditions. While at Ajmer in early 1577, he sent Sultan Khwaja, the then Mir Hajj, to Mecca and Medina with gifts, money, and an order to construct a hospice (khānqāh) there. The emperor also declared that everyone was welcome to take part in this pilgrimage at state expense.Footnote 51 In late 1577, he appointed Shah Abu Turab as Mir Hajj from his mobile camp on the way to Ajmer from Fatehpur Sikri. He also sent Itimad Khan Gujarati to head to Mecca with a lot of money, presumably to be distributed there.Footnote 52 The Ajmer shrine itself also became entangled in the ḥajj itinerary. In 1581–1582, for instance, Mughal imperial women like Gulbadan Begum and Salima Sultan Begum stopped at Ajmer on their way back from the Holy Lands to offer prayers and gifts at the dargāh.

This throws light on the various intersections of the pilgrimages of Akbar to Ajmer and those of other members of Mughal court society and subject population to the Islamic Holy Lands in the late 1570s. For Akbar, patronising the ḥajj for others augmented his own pilgrimages to Ajmer. Mughal chroniclers say that the needs of statecraft prevented him from going on ḥajj himself. Yet, in one memorable performance in early 1577, he mimicked the act of the ḥajj on a small scale. Badauni writes that after despatching his officials to organise the pilgrimage, he—en route to Ajmer—walked a small distance ‘with bare head and feet, and dressed in the Ihram, and in every respect clothed like a pilgrim, and having shorn his head a little’.Footnote 53 We are told that the crowd let out a cry at this, presumably fearing that the emperor was renouncing his kingship and becoming a pilgrim. At this, Akbar ‘showed himself moved by their devotion’ and stepped back into the shoes of the ruler.Footnote 54 Through this brief performance, Akbar enacted and legitimised his inability to go on the ḥajj because of his commitments and responsibilities to his subjects. Instead, Ajmer continued to remain his ultimate spiritual destination. At some level, however, this was probably not that much of a compromise. As P. M. Currie points out, by the time of the Mughals, Ajmer itself had come to be recognised as ‘a second Mecca’. This likeness between the sacrality of the two sites was produced by modelling several religious rituals of the Chishti dargāh after the rituals pilgrims would undertake at the holy city.Footnote 55 Thus for Akbar, the journeys to Ajmer were not really a trade-off for the ḥajj; they were, in fact, comparable to the ḥajj, if only a surrogate one.

This discussion helps contextualise Akbar's pilgrimages to Ajmer within the larger fabric of his engagements with Islam in general and Sufism in particular during the first part of his reign. We have already noted in the previous section how his actions projected imperial power and military success as flowing out of the blessings of Muinuddin Chishti. The discussion in this section situates this imperial attitude within the wider devotional context. While Muinuddin remained the most important figure for the emperor throughout this period, it is clear that devotion to other Sufi saints—alive or dead—as well as to the Islamic Holy Lands held an important position in the way royal authority was conceptualised and articulated. They indicate that during the 1560s and 1570s, Sufism in particular and Islam in general framed Akbar's kingship as he strove to garner legitimacy by projecting himself as an ideal Muslim monarch. Yet, the strong religious dimension of these pilgrimages should not obscure the very important material functions that they fulfilled. For the nascent Mughal Empire under Akbar, Ajmer held tremendous strategic significance. The next section discusses how Akbar's pilgrimages to the shrine also facilitated the process of empire-building in terms of military campaigns, administration, and governance.

Pilgrimage, military strategy, and imperial expansion

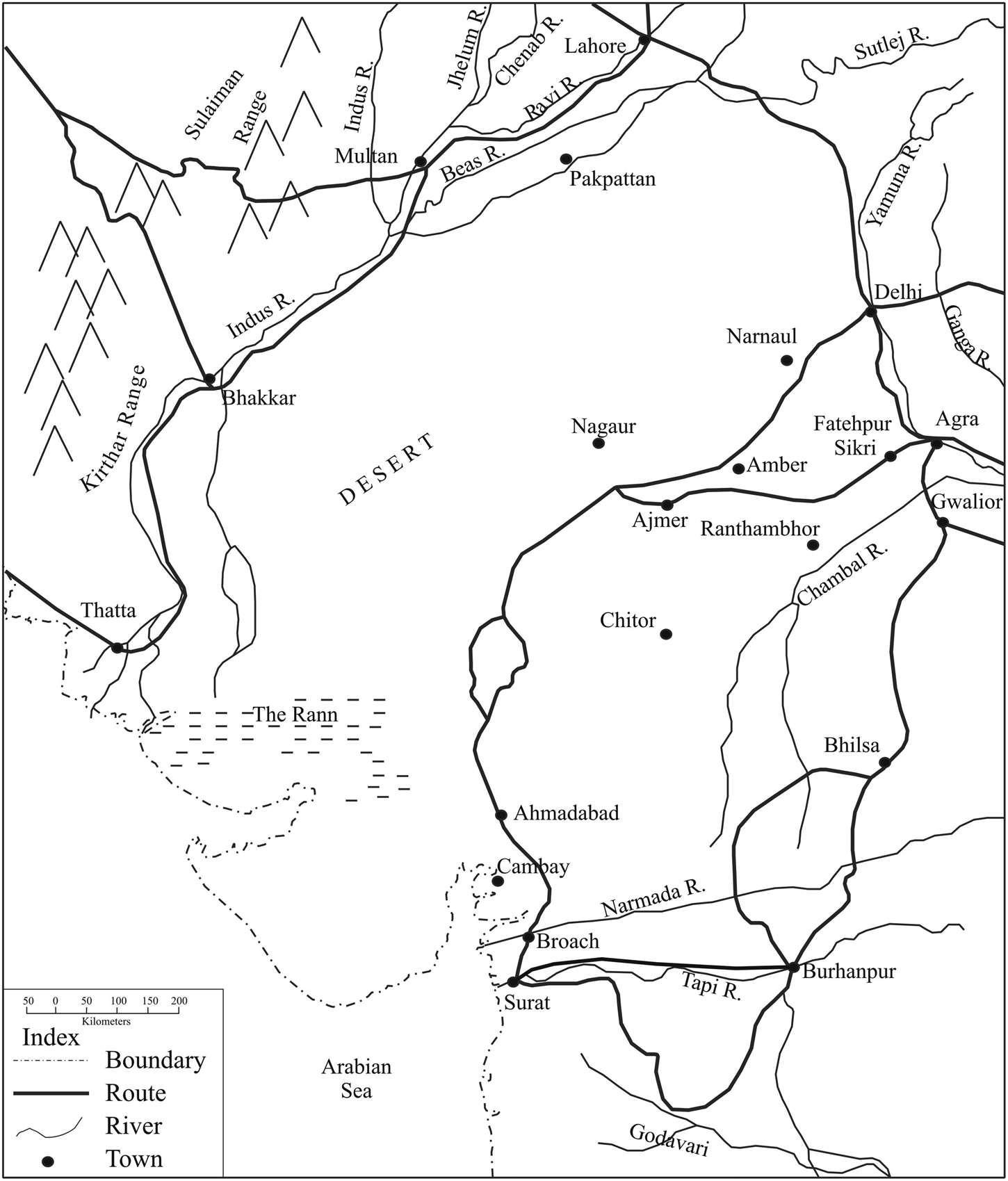

For Akbar's nascent empire, Ajmer held great strategic importance (see Figure 1). This emanated primarily from its location as a major nodal point of land routes in western India. It lay on one of the two major roads connecting the imperial cities of Delhi and Agra with the city of Ahmadabad and the port of Surat in the Gujarat littoral. In the seventeenth century, a road from Agra to Ajmer, which many European travellers took, passed first southwestward and then westward through important manufacturing towns like Bayana and Hindaun. However, Jean Deloche points out that this was merely a branch of the main imperial route that passed from Agra westward through Fatehpur Sikri, Khanua, Toda Bhim, and Bamskoh to reach Amber, and then headed southwestward to Kishangarh and Ajmer. Although this was a slightly ‘torturous’ road, its layout was probably shaped by the political importance of the Rajput principality of Amber which allied with the Mughals in 1562. To the northeast, Ajmer was connected to Delhi by a road that passed through Sambhar, Amarsar, and Rewari.Footnote 56

Figure 1. Map of Ajmer. Source: The author.

From Ajmer, the main road to Gujarat passed westward in an arcuate alignment through Merta, Pipar, Siddhapur, Palanpur, Bhinmal, and Jalor over the arid parts of Rajasthan to the west of the Aravalli Hills. Branch roads connected this road to the important Rajput principality of Jodhpur. It has been pointed out that this road was aligned in a way that gave maximum access to water and grazing resources. Immediately to the west of Ajmer, the road ran alongside the river Luni, and in many other stretches, it was serviced by wells.Footnote 57 South of Jalor, the road bifurcated, one stretch passing through Sirohi to the east of Mount Abu and the other to the west. They reunited at Magarvada to proceed southward to Ahmadabad, Baroda, and Surat. In all, this road between Delhi and Agra at one end and Ahmadabad and Surat at the other was one of the two main routes between the upper reaches of the Ganga-Yamuna Basin and the Gujarat littoral.Footnote 58

Occupying a pivotal position on this route, Ajmer gave easy access to multiple regions. Through Ahmadabad, it was linked to Gujarat in the southwest; through Agra it was connected with the Gangetic Basin in the east; and through Delhi, it was linked with the Punjab Plains in the north. Secondary routes connected it with Malwa in the southeast and Sind in the west. Hence controlling this town was of key importance to the emergent Mughal Empire under Akbar. In addition, Ajmer's central location in Rajasthan allowed anyone in control of this town easy access to all the other parts of this region. Looking to expand his authority over Rajasthan in particular, and western and central India in general, it was essential for the young emperor to gain control of Ajmer.

Nothing reflected the Mughal awareness of the strategic value of Ajmer more than Akbar's repair and expansion of the existing fort there. The emperor initiated a major overhaul of the existing fortifications in 1570, a process that lasted for three years. Aside from the military fortifications, palaces and residential quarters were also erected in the town. During the 1570s, the emperor regularly took up residence in these buildings. In addition, imperial commanders were ordered to sponsor the construction of buildings in and around the town.Footnote 59 Abul Fazl remarks, ‘[B]y the blessing of the noble advent such a grand city arose in a short space of time as could not be seen in the imaginative mirrors of magical geometricians.’Footnote 60 John Richards argues that through these actions, Ajmer emerged as part of a ‘protective framework for Mughal imperial power’ in North India, along with the cities of Agra, Allahabad, and Lahore.Footnote 61

Throughout the 1560s and 1570s, Akbar's pilgrimages to Ajmer were entangled with his military operations across Rajasthan. These operations began with him sending troops to subdue the fort of Mirtha—then under the control of Rao Maldeo of Marwar—during his very first visit to Ajmer in 1562. The command of the expedition was given to Mirza Sharafuddin Husain, who held land assignments in the Ajmer area.Footnote 62 The fort fell to the imperial army after bitter fighting.Footnote 63 The subjugation of Mirtha and eventually the pacification of Marwar secured the western flank of Ajmer. On the same trip, Akbar forged a matrimonial alliance with the Kachhwaha Rajput kingdom of Amber to the north of Ajmer. After their acquisition, Mirtha and Amber featured regularly in Akbar's itineraries around Ajmer. Next, the emperor turned to secure its southern flank. To this end, he personally led successful sieges against two major Rajput forts—Chitor (1567–68) and Ranthambhor (1569)—which were under the control of the Sisodiya Rajputs of Mewar and the Hada Rajputs of Bundi respectively.Footnote 64 On both occasions, he visited Muinuddin's shrine for thanksgiving following his victories.Footnote 65

These operations bore fruit. In 1570, the Rajput principalities of Bikaner and Jaisalmir accepted Mughal suzerainty, with their rulers offering their niece and daughter respectively in marriage to the Mughal emperor. The one major polity that continued to defy Mughal overtures and threats was the Mewar. Yet, for the Mughal state, subjugating Mewar was vital in order to secure the road that connected Ajmer with Gujarat. Hostilities between the Sisodiya Rajputs of Mewar and the Mughal Empire reached a climax in 1576. That year, a Mughal army under Man Singh inflicted a defeat on Rana Pratap Singh of Mewar on the fields of Haldighat but failed to apprehend him. As the Rana fled to the forests of the Aravallis, imperial forces occupied his kingdom.Footnote 66 Later that year, Akbar visited Ajmer. While he was there, he received the victorious Man Singh and bestowed rewards on him. In October that year, he visited Gogunda in Mewar, thereby marking the ultimate subjugation of the principality and its ritual incorporation into the Mughal realm.Footnote 67 Following his visit to Ajmer in 1577, the emperor again marched towards Gogunda. He also despatched troops to ward off the attacks carried out by the fugitive Rana on the freshly conquered territories of the empire.

From the despatch of troops against Mirtha in 1562 to the counter-insurgency operations against Rana Pratap Singh in the late-1570s, the period of the most intensive Mughal military operations against the Rajput principalities of western India coincided neatly with the years of Akbar's pilgrimages to Ajmer. As I have argued, this was no coincidence; Akbar consciously used the strategic location of the sacred town to conduct these operations. Aside from major campaigns, the emperor constantly sent troops in different directions on plundering raids or counter-insurgency operations. In early 1576, for instance, he sent troops under Taiyyib Khan against the Rajput chieftain Chandar Sen of Marwar.Footnote 68 By the end of the 1570s, Mughal hold over most of Rajasthan had been firmly established; consolidation occurred either through the use of military force, as in Chitor, Ranthambhor, and Haldighat, or through alliance-building, as in the cases of Amber, Bikaner, and Jaisalmir.

To the east of Ajmer, the erstwhile sultanate of Malwa under Baz Bahadur fell to Mughal armies in 1561. On several occasions during his visits to Ajmer, especially in the 1570s, Akbar attended to administrative matters relating to the governance of this adjoining province. For instance, in 1572, he made administrative changes in Malwa on his way from Ahmadabad to Ajmer. On this occasion, Muzaffar Khan was given the charge of the sarkars of Sarangpur and Ujjain in Malwa.Footnote 69 Following his visit to Ajmer and then Gogunda in 1576, the emperor proceeded to Malwa himself, seemingly en route to Fatehpur.Footnote 70 Finally, during his trip to Mewar in 1577, Akbar received commanders who had come to visit him from the province. He eventually landed up in Dibalpur in Malwa himself and from there sent troops southward against Asirgarh and Burhanpur in Khandesh.Footnote 71 Given that there was no imperial highway connecting Ajmer directly with Malwa, these communications between Rajasthan and Malwa must have been carried out using secondary land routes.Footnote 72

Even more importantly, Ajmer played a central role in facilitating the Mughal conquest of Gujarat in 1572–1573 and counter-insurgency operations in that region thereafter. In mid-1572 on his way to invade Gujarat, Akbar stopped at Ajmer to pray.Footnote 73 Badauni mentions that while in Ajmer, the emperor bestowed the administrative responsibilities of Jodhpur on Rai Singh of Bikanir. The latter was also given the mandate of proceeding towards Gujarat and securing the road linking Ajmer and Ahmadabad against potential attacks from Rana Pratap Singh of Mewar.Footnote 74 Nizamuddin too says that the emperor charged Rai Ram, Rai Singh, and others at Jodhpur with keeping this road open.Footnote 75 This indicates the high premium placed on the western route between Agra and Ahmadabad as the main channel of Mughal operations in Gujarat in 1572. It also highlights the importance of Ajmer as the launchpad of this invasion, especially as a forward station from Fatehpur Sikri. The emperor despatched troops under Mir Muhammad Khan, who held administrative charges in Nagaur, Ajmer, and Jodhpur, to advance towards the northern frontiers of Gujarat.Footnote 76

Following his successful campaign in Gujarat in 1572–1573, Akbar stopped at the Ajmer shrine in May 1573 for thanksgiving on his way back to Fatehpur. He was back again in about three months, this time on his way to Gujarat to mount a swift counter-insurgency operation against a strong challenge to the recently established Mughal dispensation there. This was a part of his famous lightening march on the back of a she-camel, where he took his adversaries by surprise by travelling from Fatehpur to Ahmadabad in just nine days.Footnote 77 Nizamuddin says that the emperor reached Ajmer, offered his prayers—presumably for his success in the impending operations in Gujarat—and then set off from the town on the same day.Footnote 78 It is noteworthy that even during this swift counter-insurgency operation, the emperor found it worthwhile to stop at Ajmer to pray at the shrine. This tells us about the importance Akbar ascribed at this point to the blessings of the Sufi master in securing military victories. Later that year, the emperor again briefly visited the shrine, this time on his way back from Gujarat to Fatehpur. Once he set off from Ajmer, he despatched Todar Mal to Gujarat to settle the revenue of that province.Footnote 79 In subsequent years, trips to Ajmer continued to be occasions for the emperor to receive intelligence and visitors from Gujarat and dispense of administrative measures for that province.

Aside from the heavy military traffic in 1572–1573, the road from Agra to Ahmadabad through Ajmer rose in importance during the four years since 1576, when the pilgrimages to Ajmer became a way for Akbar to launch and coordinate the ḥajj expeditions. Starting in 1576, these expeditions were made possible by the conquest and pacification of the Gujarat seaboard by 1573. I have already discussed in the previous section the significance of these expeditions in terms of Akbar's public display of devotion to Islam. In the context of the present discussion on imperial strategy and expansion, what needs to be pointed out is that these expeditions comprised a form of inter-imperial rivalry, involving no less than four major powers. Giancarlo Casale points out that by launching these expeditions as an imperial undertaking, pouring enormous amounts of money into their execution, making huge donations of gifts (ṣadaqāt) at Mecca and Medina, and sending imperial women along with other devotees on these expeditions, Akbar used them to challenge the geopolitical ambitions of the Ottoman emperors in the Indian Ocean and their political rhetoric about being the leaders of the Muslim community by virtue of their control of the Holy Lands.Footnote 80 Jorge Flores adds that Mughal participation in this contest for emerging as the leading Muslim monarch was also directed towards the Uzbek Khanate.Footnote 81 Finally, these expeditions were also about the Mughal Empire holding its own as the sponsor and protector of Muslim pilgrims against the Christian naval forces of the Portuguese maritime empire, who would habitually attack sea-faring ḥajj pilgrims from South Asia.Footnote 82

A detailed discussion of this inter-imperial rivalry is beyond the scope of this article. What is important for us to note is the role Ajmer played in all this. Once again, its importance emanated from its key location on the Agra-Ahmadabad road that connected Fatehpur Sikri—the imperial capital, and Surat—the port of departure for the ḥajj expeditions. This is the road along which the expeditions were mobilised and then despatched. However, since Rana Pratap Singh continued to be a threat to imperial forces in the Mewar region, even after his defeat at Haldighat, the imperial ḥajj caravans needed to be closely guarded as they passed through this region. It was Akbar's pilgrimages to Ajmer that made this imperial supervision possible without affecting the routine governance of the empire. For instance, after despatching the caravan for ḥajj in 1577, the emperor marched towards Gogunda himself. He ordered Qutbuddin Muhammad Khan and Raja Bhagwant Das to remain at Gogunda, and sent Qulij Khan and others to accompany the caravan up to Idar near Ahmadabad. Nizamuddin adds that these troops were instructed to plunder the Rana's territories in the course of their journey. Akbar's fears about the security of the ḥajj caravan were not unfounded; some Rajputs did attack the caravan near Idar, but were defeated. As Qulij Khan besieged the fort of Idar, on reaching the town, he sent Taimur Badakhshi with around 5,000 cavalry to accompany the caravan until it reached Ahmadabad. Eventually, as a confrontation emerged with the Portuguese in Surat, where the latter would not allow the Mughal vessels to sail, the emperor coordinated the resolution of the situation by sending Quilij Khan and Kalyan Rai to Surat from his mobile encampment.Footnote 83

Finally, Akbar's travels amid the network of Chishti shrines brought him into proximity with other regions and provided opportunities for invading them. One example is the invasion of Bhakkar in the Lower Indus Basin in early 1571. That year, Akbar went from Ajmer to Nagaur and then to Pakpattan, returning to Ajmer eventually. When he reached Hisar Firoza near Delhi, he despatched Muhibb Ali Khan to subjugate the principality of Bhakkar which was then under the control of Sultan Mahmud. Muhibb Ali Khan was given a land assignment in Multan, a standard, and a kettle-drum. The emperor also instructed the ṣūbadār of Multan to extend any help that the Khan might need.Footnote 84

All this reveals that, for Akbar, the pilgrimages to Ajmer were not just an act of piety. Rather, his stays in and travels around Ajmer in the 1560s and 1570s served as a means of territorial expansion and imperial consolidation in western and central India. The importance of Ajmer in Mughal geopolitics was also reflected by Akbar's renovation of the fortress there and the way it functioned as a base for the emperor to coordinate military expeditions in Rajasthan and Gujarat. Also important was the role of the road between Ajmer and Gujarat in the course of westward military expansion. This supports my earlier arguments about the importance of routes of communication as a crucial site and means of Mughal empire-building.Footnote 85 In the next section, we turn from the issue of war and expansion to understanding how the visits to Ajmer were occasions for Akbar to carry out imperial administration and governance as well as to perform the myriad symbolic functions of Mughal peripatetic kingship.

Pilgrimage, governance, and peripatetic kingship

Jos Gommans argues that royal mobility was a means of exercising power in the Mughal Empire.Footnote 86 Akbar's pilgrimages demonstrate this function of royal mobility in action. As the abode of the sovereign, the mobile imperial court was the prime seat of political power. As such, Akbar's journeys to and from Ajmer did not signify a break from regular administration; rather, they were an integral part of it. This section explores some of the ways in which Akbar's journeys around Ajmer emerged as a means of imperial governance and performance of kingship.

One major activity the emperor engaged in during his pilgrimages was to build alliances with local chieftains. The prototype for this was laid down during his very first pilgrimage. In 1562, Akbar set out from Agra, hunting on the way. When he reached Sambhar, one of his commanders, Chaghatai Khan, brought in the message that Bihari Mal, the king of a small Rajput principality called Amber, had requested an audience. Eventually Bihari Mal met Akbar, seemingly along with his son Bhagwant Das. They were inducted into the imperial officialdom and showered with gifts. During his return journey from Ajmer to Agra on the same trip, the emperor again stopped at Sambhar, this time to seal the alliance by marrying Bihari Mal's eldest daughter. Following more meetings between Akbar and the political elite of Amber, Man Singh, the son of Bhagwant Das, was made an imperial commander. As the emperor rushed to Agra soon after this, Man Singh and other Rajputs accompanied his entourage.Footnote 87

This was the first—and one of the most enduring—of the many alliances Akbar forged with the Rajput lineages of western India. Following a successful siege of the fort of Ranthambhor, the defeated Rai Surjan Hada of Bundi surrendered to the victorious emperor. On the eve of the emperor heading to Ajmer to give thanks for the successful siege, he gave the Rajput chieftain an audience, pardoned his offences, and inducted him into imperial service.Footnote 88 In 1570, two other matrimonial alliances were forged at Nagaur, where the emperor had halted on his way from Ajmer to Pakpattan. He married the daughter of Rawal Har Rai, the king of Jaisalmer, and the niece of Rai Kalyan Mal, the ruler of Bikaner. Even as Rai Kalyan Mal was allowed to return to his kingdom, his son was made a part of the imperial entourage.Footnote 89 There is a fair amount of literature on the cultural and political dynamics of these Mughal-Rajput alliances and political marriages.Footnote 90 Yet, few scholars have highlighted their important spatial dimension—many of these alliances were forged in the course of Akbar's visits to Ajmer. The trips to the Sufi shrine hence were an important means to fulfil one of the most crucial functions of itinerant kingship—incorporating local groups into the imperial body politic.

Royal mobility was also a means of imperial surveillance. Whenever the emperor would pass through an area, commanders and zamindars of the nearby territories were expected to demonstrate their loyalty to him by paying visits and offering gifts. This was also true for Akbar's visits to Ajmer. For instance, the emperor travelled to Banswara and Dungarpur from Ajmer in 1577 to supervise the pacification operations following the Mughal conquest of Mewar the previous year. Nizamuddin records that the chieftains of these areas paid visits to the emperor and presented him with gifts, and were in turn showered with imperial munificence.Footnote 91 The emperor also gave select commanders a chance to demonstrate their allegiance by hosting and entertaining him. For instance, when he reached Dipalpur on his journey from Ajmer to Pakpattan in 1570, he was met by Mirza Aziz Koka, who held a revenue assignment in the area. The Mirza petitioned for the emperor to rest at his house and the emperor agreed. The Mirza threw a grand feast in honour of the emperor and presented him with lavish gifts assembled from all around the world.Footnote 92 From there, Akbar went to Lahore, where he was hosted by Husain Quli Khan.Footnote 93 These examples indicate that imperial travels around Ajmer were occasions for the emperor to test the allegiance of his commanders and the chieftains in western India. For these people, visiting the emperor at his mobile court and offering tribute—especially in terms of items perceived to be valuable or exotic—was a means of expressing and confirming one's submission to imperial authority. The emperor often reciprocated by bestowing gifts and honours back on them. Hosting the emperor in one's residence was a rare honour, something that doubtless increased the political and social capital of the host. At the other end of the spectrum, failing to meet the emperor when he was passing through one's territory could count as a serious—indeed punishable—offence.

An important facet of imperial governance in the course of these journeys was the production of infrastructure. More specifically, it amounted to the improvement of the main imperial road between Agra and Ajmer. Badauni notes that in 1574, the emperor ordered the construction of residential buildings at every stage of this road and the erection of kōs mīnārs (pillars marking every kōs). Apparently Akbar also ordered these pillars to be decorated with stags’ horns acquired during his previous hunts.Footnote 94 European travellers to North India in the seventeenth century, like Nicholas Washington and William Finch, noted the presence of these kōs mīnārs. They also noted that Akbar had constructed more than one type of living quarters at regular intervals on these roads for the use of common travellers as well as imperial visitors.Footnote 95 I have argued elsewhere that road-building was a key aspect of Mughal military campaigns and territorial expansion.Footnote 96 Akbar's investment in the Agra to Ajmer route at a time when the Mughal state was making rapid inroads into western India reflects the importance it attached to the act of building roads and creating associated infrastructure.

The production of infrastructure also took other forms, ones that allowed the emperor to play the role of the benefactor of people in the course of his pilgrimages. One such instance comes from Narnaul. On Akbar's visit there from Ajmer in late 1570, the notables of the town petitioned the emperor to address a water crisis they were experiencing. They pointed out that due to one of the three tanks of the town silting up, the availability of water had decreased drastically. This had forced many inhabitants to migrate elsewhere. Contemporary texts say that Akbar intervened immediately. He ordered the tank to be dredged. The operation was headed by the imperial bakhshīs, who made the measurements and deployed soldiers to do the work. The task was soon completed. Akbar named it Shukr Talao or the Tank of Thanksgiving.Footnote 97 This incident enabled Akbar to show the benefits of Mughal imperialism to the subject population. The subjects sought and received a direct intervention from the emperor. By deciding to have the tank dredged, deploying his workers, and getting the work done, the latter made a tangible contribution to the lives of the people. Beyond the confines of constricted, localised imperial palace complexes and as a part of imperial pilgrimages, this incident provided the emperor with an opportunity to put on a public performance as the caring paterfamilias that imperial chronicles were always intent on portraying Mughal emperors as.

Imperial governance also found its way into Ajmer itself. In 1570, Akbar directly intervened in the management of the shrine in response to a dispute that had arisen about the division of the gifts offered there. Abul Fazl explains that while a group headed by one Shaikh Husain asserted descent from Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti and hence claimed the entirety of the gifts offered to the latter, others raised questions about the authenticity of Husain's lineage and, hence, his claim to the gifts. Akbar's response was to institute an inquiry, which eventually identified that the genealogy of Husain's group to be false. He then bestowed the charge of administering the shrine to one Shaikh Muhammad Bukhari. The emperor also sorted out other administrative matters of the shrine, like the finances devoted to the maintenance of pilgrims and the construction of religious buildings.Footnote 98 In effect, what this dispute did was to give the emperor an excuse to intervene in the internal matters of the shrine. It allowed him to project himself as the dispenser of justice, something that lay at the very heart of Mughal kingship. It also enabled him to emerge as the supreme arbiter—even the protector—of the shrine. His devotion incorporated the shrine and all its affairs within the ambit of imperial administration and converted it into an imperial shrine, at least for the time being.Footnote 99

There were also other acts of dispensing justice on the road. Nizamuddin mentions one such incident from Akbar's journey from Fatehpur to Ajmer in 1574. Cognizant of the damage the passage of a huge army could cause to the adjoining agricultural fields, the emperor ordered his officials to stand guard next to farmland to make sure that crops were not harmed as the army marched by. He also declared that any peasant who had suffered loss in this way would be compensated by the state. He is said to have instituted a practice whereby imperial officials would investigate and estimate the loss of individual peasants and compensate them by deducting the amount from the revenue demands assigned to them. Nizamuddin adds that in some extraordinary cases, the emperor ordered imperial officials to be present on the spot with bags of money so that peasants whose crops had been damaged could be compensated immediately.Footnote 100 Whether or not these measures were actually followed in practice, the fact the emperor passed these orders indicates the importance that he placed on his image as a benevolent, paternalistic, and just ruler.

Aside from these specific actions of the emperor at various sites in and around Ajmer, the imperial camp housed the mobile court from where routine governance and administration of the empire was carried out without interruption even in the course of the pilgrimages. A significant part of this was receiving and despatching military commanders, and delegating to them various responsibilities. For instance, on his way from Ajmer to Gujarat in 1572, Akbar despatched Man Singh to Idar to pursue the sons of Sher Khan Fuladi.Footnote 101 We find Haji Habibullah arriving from the ‘country of Firang’ and producing various novel artefacts when the emperor was encamped at Sarai Bauli on his way from Delhi to Pakpattan in late 1577.Footnote 102 On his way from Ajmer to Gogunda, Akbar was busy with setting up military outposts (sing. thāna) across the region.Footnote 103 He also coordinated military campaigns and administration in faraway provinces. While at Ajmer in 1576, for example, he received intelligence from Bengal about the activities of Daud Khan Karrani, who had recently been defeated by Mughal forces, and despatched a farmān with instructions for his commanders posted there.

Another activity that allowed Akbar to fulfil the myriad symbolic functions of kingship in the course of his journeys to and from Ajmer was hunting.Footnote 104 The emperor often hunted during his military expeditions; the pursuit of game in these cases was understood to signify his pursuit of his adversary.Footnote 105 Similarly, the frequency with which he hunted en route to Ajmer and other Sufi shrines seems to have signified his pursuit of spiritual objectives. This association between the two was established the very first time the emperor visited Ajmer. As mentioned earlier, he set out from Agra towards Fatehpur early in 1562 on a hunting expedition. On the way, he reached Mandhakar to discover a few minstrels singing devotional music in praise of Khwaja Muinuddin. A chronicler says that it was this incident that triggered in the emperor a strong desire to visit the shrine of the Sufi master.Footnote 106 This is what eventually brought Akbar to Ajmer for the first time.

This spiritual discovery in the course of a royal hunt was far from an exception; rather, it points to an important function of imperial hunts in the Mughal world—its deep associations with mystical experience.Footnote 107 As for Akbar, contemporary chronicles mention several instances of actual mystical experiences in the course of hunting expeditions around Ajmer. In fact, the hunt was often an occasion for the emperor to have spiritual experiences and display miracles in a public setting. Nizamuddin notes the occurrence of such an incident in 1571, as Akbar was hunting on the way from Ajmer to Agra by way of Pakpattan. While the hunt was in progress, Akbar went into a strange state of trance.Footnote 108 Once he emerged from it, he ordered the hunt to be stopped and the game that had been cornered in the qamargāh be released. He ordered the erection of a building and the founding of a garden at the spot where ‘Divine grace had descended on him’.Footnote 109 He also distributed money to the poor. Finally, he shaved his head and many of his courtiers followed suit.Footnote 110

What is significant is that the emperor had this mystical experience on the same trip in which he visited most of the major Sufi shrines of northwestern India, including those in Ajmer, Delhi, Pakpattan, and Hansi. He also met Shaikh Nizam Narnauli in person at Narnaul. I have already mentioned that in the course of his pilgrimages to Ajmer, Akbar gradually started to embody many of the attributes of Sufi authority himself. In this context, one is tempted to surmise that it was not entirely a coincidence that Akbar had this mystical experience on the same trip that he visited so many Sufi shrines. Rather, deeply immersed in Sufi devotion, this was a perfect occasion for him to publicly display the markers of Sufi authority that he had come to embody himself. The royal hunt, rife with spiritual associations, was a perfect site for this performance. Ebba Koch compares such spiritual experiences of Akbar in the course of hunting expeditions with protagonists of Sanskrit epics, who often had similar spiritual awakenings during their visits to the forest.Footnote 111

In general, hunting expeditions also allowed the Mughals to perform other functions of kingship. The imperial hunts undertaken in the course of the pilgrimages exemplify this. As Abul Fazl mentions repeatedly, hunting expeditions were a means for the emperor to explore the realms and to get in touch with his subjects directly. This is exemplified by an incident from 1577 narrated by Nizamuddin Ahmad. Having hunted all day on his way from Ajmer to Delhi, the emperor spent the night at the house of a village headman in Palam. Later, he declared that whenever he would take up accommodation with one of his subjects, he would reward them with tax-free land grants (madad-i ma'ash).Footnote 112 This was yet another way for the emperor to show his caring rulership to his subjects in the course of his pilgrimages. Hunts also presented the emperor with opportunities to display his munificence. In 1570, for instance, he hunted wild asses on his way from Ajmer to Pakpattan. Having traversed a long distance on foot in chase and having killed 13 asses, he ordered the animals to be brought to the camp by carts and then their flesh to be distributed among the imperial attendants and commanders.Footnote 113 Finally, hunting expeditions allowed the emperor to publicly display his imperial might and majesty. One way of doing this was killing big game, which itself was an imperial prerogative. As these acts were later narrativized by imperial chroniclers, these performances also made their way into the literary space for posterity. Let us consider one example. In 1572, Akbar hunted a lion on his way to Ajmer. The chronicler Arif Qandahari makes the description of this incident an occasion for extolling the greatness of the emperor. He writes that ‘the emperor confronted a mighty lion before whom even the (Babar) lion of the jungle bends his head like a cat. The lion-throwing emperor threw it down with the point of his lance.’Footnote 114 In this narrative, the literary hyperbole used to describe the lion helps accentuate the enactment of imperial charisma—the greatness of the emperor lay in the fact that the lion he hunted was extraordinary, one that put all other lions to shame.

Thus, the journeys around Ajmer comprised an important aspect of Akbar's kingship and governance. From forging alliances and creating infrastructure to performing as a just and caring ruler, the various actions undertaken in the course of these imperial itineraries played a key role in solidifying the young emperor's position as an able monarch. Beyond the confines of the imperial palaces, the public setting of the pilgrimages made his actions accessible to sizeable sections of his imperial subjects and allowed them to witness, experience, and benefit from his kingship. Hunting expeditions, with their mystical undertones, provided a rich site for the performative aspects of Mughal kingship.Footnote 115

End of the pilgrimages and a new form of kingship

As much as the frequency of Akbar's pilgrimages—17 times in 18 years—is remarkable, what is equally noteworthy is the fact that these visits stopped altogether after 1579. Never again did the emperor visit the shrine that had kept his attention riveted for almost two decades. What was the reason behind this? And what does this tell us about Akbar's relationship with the Sufi dargāh and the significance of the pilgrimages within his project of empire-building? To some extent, this can be explained by the changing strategic priorities of the empire in the early 1580s. By the close of the 1570s, the process of imperial expansion and consolidation in western and central India had reached a level of maturation. Consequently, the need to continue to use Ajmer as a strategic base decreased drastically. The city that replaced Ajmer in this regard for much of the 1580s and 1590s was Lahore. The emperor moved there in 1585—at around the same time as the death of his half-brother and political rival Mirza Muhammad Hakim and the Mughal annexation of Kabul. Akbar devoted the following years to consolidating the imperial hold over this important frontier city and coordinating counter-insurgency operations against Afghan tribal populations of the neighbouring regions. He also used his stay in Punjab to supervise the conquest of Kashmir in 1586 and Thatta in 1591–1592. It was only in 1598, with the relaxation of the Uzbek threat against Kabul, that the emperor finally moved from Lahore to Agra. This indicates that, just like the pilgrimages to Ajmer took place partly because of the emperor's urge to expand imperial authority over western and central India, so their end in 1579 was to some extent the result of the profound shift in the geopolitical landscape of the empire, whereby the political and military centre of gravity had shifted to the northwestern frontier.

While this explains the imperial abandonment of the Ajmer shrine, it does not explain why the emperor did not adopt a different shrine conveniently close to his new base, Lahore. In fact, in the years that he spent in Punjab, he rarely visited the shrine of Baba Farid in Pakpattan. If Akbar's devotion to the Ajmer shrine signified his devotion to Islam—something also reflected by his sponsorship of the ḥajj expeditions from 1576 to 1580—then did their end in around 1580 indicate that the emperor had turned his face away from the faith? Is this why he also abolished jizīya for the second time in 1580? This is what Iqtidar Alam Khan argues. As mentioned earlier, for him, Akbar's public demonstrations of his devotion to Islam were motivated by his desire to placate his Indian Muslim nobility. Khan suggests that the rebellion by a part of the Muslim aristocracy in 1580 disillusioned Akbar about the value of this confessional investment and brought about a shift in imperial ideology that now increasingly became more universalist in its approach.Footnote 116

Yet, this argument does not explain why, at around the same time and afterwards, Akbar continued to engage with Islam, albeit in more complex ways. The maḥẓar of 1579 already proclaimed him as the supreme arbiter in matters of Islam, using markers of authority from orthodox Islam as imperial attributes. A case in point is the use of titles like Amir ul-Muminin—a title used earlier by the caliphs—to designate the emperor.Footnote 117 In 1582, Akbar commissioned the writing of Tārīkh-i Alfī, which Bruce Lawrence argues was meant to project the emperor's rule as the divinely mandated culmination of the expansion of political Islam during its first millennium.Footnote 118 Akbar's performance of miracles, creation of the imperial cult around himself in the mould of a Sufi order (which later came to be known as dīn-i Ilāhī, especially among his critics), and Abul Fazl's use of the Sufi category of insān-i kāmil (the perfect man) to describe him reflect appropriations of the markers of Sufi authority to characterise imperial authority.Footnote 119 Finally, as Azfar Moin points out, Akbar also increasingly presented himself as the ‘millennial sovereign’—the long-awaited renewer of Islam (mujaddid) who was expected to appear at the completion of the Islamic millennium in 1591–1592.Footnote 120 These continued engagements with Islam contradict Khan's suggestion that Akbar turned his face away from the faith after 1580.

Rather, what these engagements signified was a new kind of relationship that was forged between rulership and faith. The initial political paradigm of the 1560s and 1570s was marked by a complete subversion of imperial power to the authority of both scriptural and mystical Islam. In the new paradigm that began in around 1580, there emerged a more selective and pragmatic engagement with Islam within a larger ideological paradigm of universalist and cosmopolitan sovereignty, framed by the notions of ṣulḥ-i kul and millennial kingship. The emperor now no longer needed to bow down to any Islamic authority to legitimise his rule; instead, he embodied all the qualities—and hence the authority—of the caliph, the Sufi, and the mujaddid, and rose above them all at the same time. By declaring himself as the saint of the age, he positioned himself above the laws of Islam. In contrast to the model of Islamic kingship that Akbar had created for himself by venerating Sufis and sending ḥajj expeditions earlier in his reign, this signified a new form of kingship that was universal, millennial, and sacred—one that would be continued throughout the mid-seventeenth century by his son Jahangir (r. 1605–1627) and grandson Shah Jahan (r. 1628–58).

Aside from selectively using Islamic markers of authority, this new universal form of kingship freely drew upon a range of Perso-Islamic, Turco-Mongol, Indic, and biblical notions of authority and symbols of power. It borrowed heavily from Persian akhlāqī norms of kingship—canonised in the twelfth century by Nasiruddin Tusi and based on pre-Islamic Iranian political philosophy, which envisioned the king as the fountain of justice, order, and harmony.Footnote 121 It made ample use of the Turco-Mongol ancestry of the dynasty, especially Timurid cultural heritage, political charisma, and markers of authority.Footnote 122 It deployed Indic forms of sacred performance like the jharokha darshan, wherein the emperor would appear every morning at a window of the imperial fort to be viewed by his subjects in a ritual that mimicked the Hindu religious practice of devotees viewing a deity.Footnote 123 Finally, it appropriated the biblical, Greek, and Perso-Arabic ideals of Solomon, Orpheus, and Majnun respectively to model the Mughal sovereign as the just ruler of the natural world, one who brought about harmony and peaceful coexistence among natural forces that are habitually inimical to each other.Footnote 124 This universal and sacred kingship found expression in dynastic chronicles and biographies like Abul Fazl's Akbarnama, which depicted the emperor as a divinely ordained, justice-dispensing, paternalist ruler of the whole world.Footnote 125 Under Jahangir, it was conveyed most vividly through visual images, like the allegorical portraits that conveyed the emperor's control over both space and time by positioning him on a globe or an hourglass respectively.Footnote 126 Shah Jahan's expression of the sacrality and universalism of Mughal kingship took its most brilliant form in architecture, exemplified by the case of Taj Mahal that presented the emperor's mausoleum as a monumental imperial abode situated amid the gardens of paradise.Footnote 127

In this new ideological paradigm inaugurated around 1580, the spiritual status of the living emperor overshadowed the mystical authority of the dead Sufi. Having briefly enjoyed the status of an imperial shrine—comparable to the status of the shrine of Imam Reza at Mashhad for the Safavids—Ajmer was now overshadowed in sacrality by both the imperial court of living Mughal emperors and the monumental tombs of deceased ones.Footnote 128 Instead of displaying devotion at Sufi shrines, the emperor now laid down the norms of devotion that he expected from his nobility. Badauni points out that in 1581, Akbar outlined four degrees of this devotion—willingness to sacrifice one's property, life, honour, and religion.Footnote 129 It was this redefinition of Mughal kingship that rendered public displays of devotion to Islamic authority—like the pilgrimages to the Sufi shrines and the ḥajj expeditions—superfluous after 1580.

It is in this milieu of the late sixteenth century that Abul Fazl narrated a particular incident in his official biography of the emperor. This was about a group of people from the Ajmer shrine telling Akbar about a dream they had had. In this dream, Khwaja Muinuddin himself had appeared to tell these people to prevent Akbar from visiting the shrine when he was en route to Ajmer in 1568. The Sufi master had explained that ‘If he [Akbar] knew the amount of his own spirituality he would not bestow a glance on me the sitter-in-the-dust in the path of studentship.’Footnote 130 As Azfar Moin reminds us, dreaming as well as interpreting dreams was a social phenomenon central to religious, political, and cultural life in the early modern world. Seen as a ‘social fact’, dreams were considered to be a means for people to connect with other-worldly beings and gain knowledge otherwise unattainable. As such, dreams—like astrology—helped people to give meaning to the world around them. Hence, they had tremendous ideological power as propaganda tools.Footnote 131 Seen in this light, Abul Fazl's narrative of the dream from the late sixteenth century proclaimed Akbar as one with a much higher spiritual status than the revered Sufi master Muinuddin—ironically the same figure who had earlier been the focus of the emperor's devotion for almost two decades. But now, in the transformed ideological paradigm of the post-1580 period, the tables had turned.