Introduction

Since the birth of Irish civilisation some ten thousand years ago, a tradition of song has greeted new dawns and celebrated life. Haunting voices over mountains, valleys, and lakes, carry with them ancient tales we now cherish. This poetry of song is part of who we are. It is in our souls. We live and breathe it, and nowhere is this more true than in Celtic Woman. Footnote 1

Although heterogeneity has always been a hallmark of the Celtic music scene, as Martin Stokes and Philip Bohlman (Reference Stokes, Bohlman, Stokes and Bohlman2003, pp. 6–10, 17) observed nearly two decades ago, the genre is frequently associated by both marketers and fans with a long-standing history of musical traditions. ‘Celtic music’ borrows tunes and traditions from various Celtic cultures – Irish, Scottish, Cornish, Galician, and the like – and mixes them with other musics both exotic and familiar.Footnote 2 Best known to American audiences through the mega-shows Riverdance (1995) and Celtic Woman (2005), the genre in both its large and smaller idioms trends toward toe-tapping reels and vocal ballads, with an eclectic ‘Celtic’ instrumentarium of harp and pipes (Uilleann or Scottish), fiddle, the tin whistle and its ilk, the Bodhrán and other percussion, accordion, guitar, lute and other instruments as available and desired.

Abundance in instruments and in stage resources of choreography and lights, fancy clothes and performative elegance marks the Celtic music genre as the glitzier cousin of Irish Traditional Music and its practices. Indeed, marketing materials for Celtic music frequently provide a nod towards an imagined continuity of folk traditions, as when the women performers of Celtic Woman, quoted in the epigraph, call up a mystic and magical age of Irish civilisation with its ‘new dawns’ and ‘haunting voices’. They situate this imagined musical past in a regional (and presumably Irish) topography, and make claims of connection, ‘our souls’ resonating to acoustical phenomenon. Yet, to this ‘folk’-derived, or at least folk-allusive repertoire, performers might add a mixture of songs from Enya (Irish), Ennio Morricone (Italian) or Jay Ungar (American) alongside historic and newly composed repertoire based on ‘classic’ poetic and musical literature – Englishmen such as Shakespeare or Alfred, Lord Tennyson; Irishmen William Butler Yeats and composer Michael William Balfe; or classics from the Western Art Music canon such as the Gounod/Bach ‘Ave Maria’ (1859) or Gabriel Fauré's ‘Les Berceaux’ (1879). Wong Zhi Xuan and Loo Fung Ying (Reference Wong and Ying2022, pp. 1–3) confirm the importance of eclecticism to the genre; for them, cultural hybridity forms a central tenet of Celtic music and its transformations in ways that intersect with its commercial potential on the global market.

Within this transnational stylistic environment, Celtic performers like Loreena McKennitt (Canada), the Ensemble Galilei (a predominantly American ensemble), and Méav (Ireland) found their own marketing strategies aligned to broader Celtic and World Music narratives. Their careers, like those of their musical peers, are marked by an emphasis on folk music, geography-as-culture, and the ‘fair maiden’ topos so often applied to female performers of the idiom. In their systematic review of Celtic music scholarship, Wong and Ying invite us to consider women as a special category within the Celtic music phenomenon, for they observe that Celtic musical identity is gendered, as well as layered with occupational, citizenship and religious situations (Wong and Ying Reference Wong and Ying2022, p. 2). These smaller musical acts, however, have received limited scholarly attention, despite an enormous fan base, extensive ticket sales and record sales in the millions. Each of these three performing groups has shaped a musical identity within the ‘Celtic realm’ that includes a predictably heterogenous repertoire that mixes traditional and ‘found’ or newly created repertoire. Each has also engaged productively with Shakespeare explicitly – through borrowed and adapted texts for McKennitt and Méav and through titles and liner-note explanations for Ensemble Galilei. They shift those Shakespearean texts into the world of the miniature, what Richard Burt refers to as a kind of ‘remediation’ where ‘Shakespeare’ has been both reduced and modified to fit into a shorter musical genre (Burt Reference Burt and Burt2007, p. 4). Thus, they bring what is sometimes deemed an archetypically ‘English’ resource, Shakespeare, into a ‘Celtic’ – and thus apparently non-English – folk idiom in ways that play with the twinned concepts of tradition and of timelessness.

This kind of engagement between modern creative artists and past playwright (and his associated oeuvre) matters because the resultant intertextuality is a thread susceptible to analytical unpicking. The presence of an intertextual connection creates a space of potential discovery for the audience, one that can add a sense of fun by way of that meaningful moment of surprised recognition to the experience of the piece. Nor is this recognition simply a neutral observation. Christy Desmet, for instance, explores the ethical ramifications of appropriation. She sees its import as falling in ‘the tension between taking and giving that characterizes dialogic interactions. The value of appropriation lies in showing us a different connection, a previously unacknowledged resemblance, between two texts or persons’ (Desmet Reference Desmet, Huang and Rivlin2014, p. 55). By looking at both ends of the relationship between Celtic music and Shakespeare, we should come away with a richer understanding of each. Alexa Huang and Elizabeth Rivlin would agree, for they point out that ‘appropriations raise ethical questions with a special intensity because they display self-awareness about their enmeshment in intertextual relationships and their interdependence with other texts’ (Huang and Rivlin Reference Huang, Rivlin, Huang and Rivlin2014, p. 5). In other words, they see such moments of appropriation as an acknowledged dependence on the side of the modern partner and a moment of potential illumination for the originating partner in what Diana Henderson calls ‘diachronic collaborations’.

Popular music studies have found this kind of assessment to be useful underpinnings to scholarly analysis. Wes Folkerth, for instance, asks ‘how these references inform the musical work, and how they in turn speak back to the play’ (Folkerth Reference Folkerth and Burt2007, p. 367). And Adam Hansen's foundational work on Shakespeare's presence in the popular music realm commands us ‘to give meaning and context to how and why popular musicians in different times and places have made Shakespeare their contemporary’ (Hansen Reference Hansen2010, p. 5). Starting from a different place, Siglind Bruhn asks us to consider such ‘transmedializations’ in the context of musical ekphrasis, in which music as a ‘responding media’ does more than set the words to melody; an ekphrastic response ‘reflects or comments on aspects of the source text’, often without including the words themselves (Bruhn Reference Bruhn2008, p. 9).

Understanding stems not only from recognition of the connection, in other words, but also from the meaning(s) attached to such trans-temporal collaborations. There is a paradox inherent in this process of adaptation for the Celtic repertoire studied here, of course. Celtic performers ‘make the old new again’ by pairing it with new music, but that music is itself heard and described by fans as being in an old, antique musical style. In other words, the old and the faux-old are put in dialogue in this repertoire.

Given the popular nature of the Celtic music genre, a large and vocal community of fans and of critics has engaged with this repertoire. Craig Dionne and Parmita Kapadia remind us that ‘con-texts are themselves texts and must be read with’ for purposes of comprehension. They see the world of reception as acts of detecting and digesting (Dionne and Kapadia Reference Dionne, Kapadia, Dionne and Kapadia2008, p. 7). I agree, and thus approach this repertoire of Shakespearean allusions within Celtic music with two strategies. First, I provide close readings of Shakespearean works for select female Celtic performers: Loreena McKennitt (Reference McKennitt1991, Reference McKennitt1994), what was then the ‘six women’ of Ensemble Galilei (2000), and Méav (stage-name of Méav Ní Mhaolchatha) (Reference Méav2002). I ask what Shakespeare is ‘doing’ in the song or instrumental number and, dialogically, what the contemporary musical work is ‘doing’ for Shakespeare. Second, I examine the reception of these works by engaging in a deep reading of newspaper criticism and of fan-generated materials.

The material that serves here as the basis for this assessment of Celtic music's reception is quite varied. Reviews and concert previews are readily accessible through data aggregators such as Music Periodical Index, ProQuest and NexisUni as well as links through artist sites and some of the fan-generated websites, where curating reviews was quite common in the 2002–2010 span. Fan materials, on the other hand, come in different flavours depending on the performer. Fan feedback for Loreena McKennitt's works is drawn from the more than 400 comments that accompany 16 instantiations of her Shakespearean works on YouTube. Ensemble Galilei, in contrast, have fan reviews on Amazon.com and a robust community presence on Facebook, but their YouTube presence reflects only their more recent recording activity and there are only four YouTube comments on items from their Shakespearean album. Méav's social media presence is different yet again, being centred largely on fan-generated websites and discussion boards. Those sites were clearly impacted by the impact of mega-show Celtic Woman; Méav was one of its founding performers and clearly benefited from the increased visibility that came with the act's success. The meavforum.com site, for instance, had more than 20,000 posts across 2000 topics, and the Méav community also has a lively presence on Celtic woman sites such as celticwoman.com, celticwomanforum.com and celticwomanforum.net. To respect fan privacy, I have cited here only comments from open, not subscription, forums, although my reading has been informed by the many enthusiasts (and a few detractors) who have communicated their thoughts online.

Defining Celtic music and Celtic identities

Celtic music as a category lacks a clear definition, although marketers have tended to group it with folk music or world music, themselves nebulous categories. Described by Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin as ‘a genre for which there are no clear definitions, no precise territorial markers, no detailed chronologies and few musicological taxonomies’ (Reference Ó hAllmhuráin and Newton2013, p. 187), Celtic music seems to exist somewhere between marketing ploy and musical style. Given its idioms and its folk materials of ballads, dances and generalised airs, it quite clearly overlaps with other repertories, most notably that of Irish Traditional Music (often referred to with the short-hand label ITM) with which it is often conflated (Chapman Reference Chapman and Stokes1994; Thornton Reference Thornton1998; Stokes and Bohlman Reference Stokes, Bohlman, Stokes and Bohlman2003; O'Flynn Reference O'Flynn2009). Both genres are, of course, shaped by economic realities and market imperatives. Both benefitted from the rise of the so-called Celtic Tiger era of Irish economic successes, and both intersect with traditional musical practices. Scott Reiss (Reference Reiss, Stokes and Bohlman2003, pp. 158–9) argues, however, and I agree, that ITM is grounded in a preservationist approach to the repertoire and its face-to-face musical practices, and that Celtic music, if it has a specific identity, is grounded more firmly in practices of modernisation, commercialisation and transformation. That is, ‘Celtic’ music is not ‘Irish’, although they share an overlap of tunes and timbres.

For one thing, ‘Celtic’ identity lacks the regional grounding and localising practices of ‘ITM’. Tunes from different regions fit comfortably cheek-by-jowl in a Celtic performance, whereas an ITM session is more likely to draw on localised body of familiar tunes. Moreover, ‘Celtic’ repertoire, with its heterogeneous eclecticism, seems more centrally to be about its showy elements; it is an experience with dancers and sets, costumes and choreographies in ways that are at odds with the consumption of more traditional forms of folk traditions in Ireland or elsewhere. And above all, Celtic music can be noted for being inclusive of a variety of diasporic practice. As Ó hAllmhuráin articulates, ‘The Celtic diaspora is intensely diffuse and is characterised by multiple layers of cultural hybridity and transculturation’ (Reference Ó hAllmhuráin and Newton2013, p. 191). In other words, the Celtic repertoire takes advantage of the geographical dispersal of nominally ‘Celtic’ populations to forge a style that borrows generously from an array of progenitor musical styles. Just as the instrumental resources might include Scottish instruments alongside more traditionally Irish ones, the choice of source for tune and text reflects a broad umbrella understanding of ‘the Celtic peoples’.

Given the trans-national and often diasporic nature of Celtic identities, it is perhaps unsurprising that the women of the three Celtic music groups examined here relate to their own Celtic identities in varying ways. Loreena McKennitt is Canadian, and thus part of the Celtic diaspora. From the beginning of her career, she self-consciously claimed her Celtic heritage and described her music as ‘eclectic Celtic’ to those who would listen. She was conscious of a mixture of styles in her works, but, as Javier Campos Calvo-Sotelo has explored at length, she was also certain that her exploration of global sounds was fitted into a broader context of Celtic and neo-Celtic culture. Her encounter with the breadth of Celtic culture at the 1991 Venetian exhibit, for instance, led her to understand that ‘there's a whole stretch of history that is an extension of who you are’ (McKennitt, as quoted in Calvo-Sotelo Reference Calvo-Sotelo2017, p. 377). Roger Levesque and others have shown how McKennitt took travel as an educational tool, ‘seeking out Celtic connections in surprising places’, and then capitalised on this knowledge by translating her findings into musical form (Levesque Reference Levesque2007, p. D1; Howell Reference Howell1994, p. C1). McKennitt, in other words, brings an acknowledged transnational understanding to the Celtic music phenomenon.

In contrast, the ‘six women’ of Ensemble Galilei who collaborated on their Shakespearean album, Come, Gentle Night (2000), came from more diverse backgrounds, primarily from America. Liz Knowles, for instance, hails from Kentucky, and the early part of her career in New York City included both baroque music and Irish fiddle work with such groups as the John Whelan Band and Cherish the Ladies. Her role as a fiddler for Riverdance situates her as one of the central performers of the Celtic music scene. Sarah Weiner, in contrast, has focused primarily on the baroque side of her career, having trained as an early music performer at Oberlin Conservatory and at the Early Music Institute of Indiana University. As they proclaim on their website, ‘Founded in 1990, Ensemble Galilei is an ensemble of players from both classical and Celtic backgrounds, playing Irish and Scottish airs and dance tunes, early and medieval music, and original compositions’ (Ensemble Galilei, https://egmusic.com/). That intermixing of ‘early and medieval’ music and ‘Irish and Scottish airs and dance tunes’ points toward a blending in performance of period-specific antique style sourced authentically with the more generalised sense of antiquity of the folk traditional language. Indeed, their founder Carolyn Surrick reported:

The group was founded on the idea that making music is more important than the genre. And the ideal is to make music with like-minded people. Some of the ensemble's members have a Celtic background and some have an early-music background. But we all believe that it's not enough just to play music. You need to play from the heart. That's why we're together. (Surrick, as quoted in Reichel Reference Reichel1999)

For Ensemble Galilei, in other words, it wasn't so much personal heritage, but style and synergy that drew the group together in their crossover Celtic ventures. Moreover, these parallels of style are important to fan reception, judging by the corpus of fan commentary that praises newer musical numbers while speaking to the evocation of ‘a time long gone’.

Lastly, Méav Ní Mhaolchatha, who goes by the mononym Méav, is Irish-born and trained. Her early success with the Irish choral group Anúna from 1994 to 1998 overlapped with the group's performances in Riverdance: The Show, and she served as well as vocalist for tours of Lord of the Dance. Thus, she was already at the centre of the Celtic craze when she left the world of ensemble work for several years to focus on her solo career, issuing her first solo album, Méav, in 1999, and a second, Silver Sea, in 2002. Thus, all three groups related to the Irish–Celtic spectrum in different ways. Their shared musical idiom, in other words, reflects neither shared geography nor shared politic. What unites them is what Shannon Thornton describes as their spot in ‘festivals and record bins’ (Thornton Reference Thornton1998, p. 262).

Setting Shakespeare as Celtic music

There is a certain irony in the selection of an author frequently ascribed with consolidating English colonialism as a source of poetic inspiration for an idiom inflected by Irish identity. Scholarly research on colonial and post-colonial Shakespeares demonstrates both the imposition of Shakespeare as an educational tool in non-English environments and an enthusiastic adoption of his works by locals in a variety of environments (Loomba and Orkin Reference Loomba and Orkin2002; Dionne and Kapadia Reference Dionne, Kapadia, Dionne and Kapadia2008). Shakespeare's connections to Welsh language and culture in particular have garnered significant attention in recent years. Megan Lloyd (Reference Lloyd2007), for instance, highlighted the Elizabethan audience's familiarity with Welsh language and its political undertones as a crucial context for Shakespeare's numerous allusions to Welsh characters and places in his plays. Building upon this foundation, the collection of essays edited by Willy Maley and Philip Schwyzer (Reference Maley and Schwyzer2010) broadened their scope of inquiry to consider the familial, educational and cultural dimensions of Welsh and Celtic identities within the Shakespearean context. Whether Shakespeare himself had Celtic ancestry (potentially through a Welsh grandmother) or simply absorbed a culture rich in centre-to-borderlands references, his incorporation of Celtic characters and motifs from various regions (Welsh, Scottish, Irish, Breton, etc.) provides a compelling backdrop for contemporary interpretations of the evolving political landscape (Maley and Schwyzer Reference Maley and Schwyzer2010; Maley and Loughnane Reference Maley and Loughnane2013; Cull Reference Cull2014).

The complexity of Celtic, and particularly Irish, claims on Shakespeare stems in part from what O'Neil characterises as ‘conquest, cultural difference, and national identity’ (O'Neil Reference O'Neil, Maley and Loughnane2013, pp. 247, 249). Yet, as Richard English has articulated, ‘Irish people's experience has been more complicated than simply to have involved, or been defined by, resistance to British influence or power’ (English Reference English, Burnett and Wray1997, pp. 145–6; see also Eagleton Reference Eagleton1998, pp. 312–14). Andrew Murphy, for instance, has traced the ways in which Shakespeare's work was repurposed for the needs of the Irish nationalist movement in the early 20th century (Murphy Reference Murphy and Holland2015), and Declan Kiberd has spoken to the ideas of subversive rereadings (p. 271) and reinvented ones (p. 281) in a reminder that the intersections of Shakespeare's works and Irish/Celtic readers are never as simple as an insider/outsider binary. Indeed, Emer McHugh (Reference McHugh2023) makes this point explicit in the context of performance: ‘the appropriation and adaptation of Shakespeare in an Irish context is not, and never has been, a politically neutral act: it is charged with the histories of imperialism, cultural hegemony, and colonial violence’. Like Shahmima Akhtar's examination of the (highly scripted) Irish presence at world's fairs of the 19th and 20th centuries, we could see Celtic music as a platform for the Irish (and other Celts) ‘to authenticate and curate their own selfhood in public spaces’ (Roundtable 2021; Akhtar Reference Akhtar2023).

Thus, the adoption of Shakespearean texts by Celtic music creators invites close attention to the multifaceted relationship between literature, identity and the cultural product being put on display. By revelling in reciprocity (pace Clare and O'Neill Reference Clare and O'Neill2010, p. 14), it invites an assessment of the artistic and creative processes involved in incorporating Shakespearean themes, motifs or language into Celtic music, and equally asks us to consider the impact of these adaptations on the reception and understanding of both Shakespeare and Celtic culture. In short, following the lead of Folkerth and of Hansen, we can ask what these musicians DO with Shakespeare, and what is done to Shakespeare in that process.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the differences in the performers’ backgrounds, there are three different strategies at play. McKennitt approaches her compositions as scene development, reshaping Shakespearean forms in a structural as well as a transmedial way. Ensemble Galilei's represents a more commercial approach, for they were invited to move into the space by a record label seeking to capitalise on Shakespearean popularity at the time of the hit movie Shakespeare in Love (1998), as Craig Zeichner observed at the time (Reference Zeichner2000, p. 335). Méav's offerings, in contrast, invoke Shakespeare as commonplace – a quotation or reference that fits into a sampling that is framed on the front-end by a song from Irish singer-songwriter John Spillane and on the back by a Frenchman's arrangement of a Kurt Weill tango – with works in French, Irish, English and Scottish Gaelic fitted in between.

Loreena McKennitt's engagement with Shakespeare began early, for her unusual career trajectory included an apprenticeship with the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon in England as well as a stint acting in and composing for Ontario's Stratford Festival productions (Krewen Reference Krewen1992a, p. D7; Van Rhijn Reference Van Rhijn2002, pp. 60–63). That cultivation of dramatic sensitivity may help to explain her choice of texts. In ‘Prospero's Speech’, she opts for the renowned epilogue rather than one of the many vocal songs from The Tempest, while in ‘Cymbeline’ she chooses to adapt a song text that was actually spoken in the original play. In both settings, she invites a rethinking of the Shakespearean text.

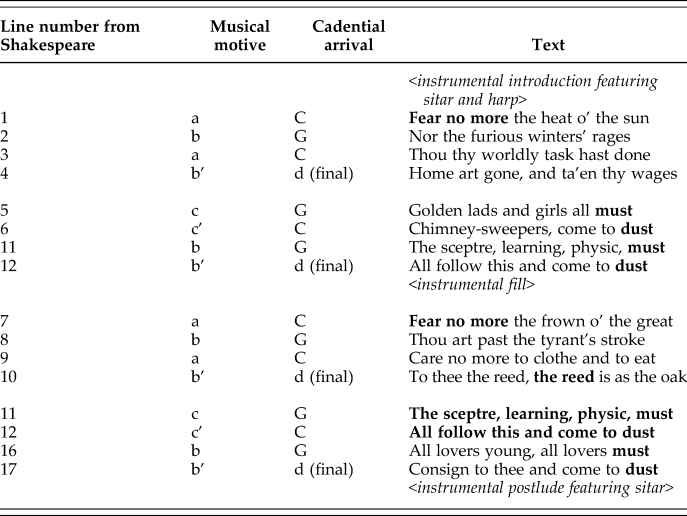

In ‘Cymbeline’, for instance, she adopts a kind of verbal repetition that differs from the keyword repetition built into the Shakespearean construct. (Compare Tables 1 and 2.) What was in Shakespeare a set of four spoken sestets (with ‘Fear no more’ and ‘come to dust’ as the framing verbal devices of the first three stanzas) becomes paired quatrains, the second of which uses the increased intensity of rhyme (must – dust – must – dust) as well as higher musical register to drive towards the conclusion. In addition to pivoting from dialogue to a single speaker or singer, McKennitt omits Shakespeare's last sestet altogether and rearranges line order to create her faster-seeming second quatrain in each paired repetition. This shifts the meaning of the scene. Rather than a wish for the absence of fear and the arrival of bodily dissolution, as articulated by Polydor and Cadwal in memory of their beloved companion Fidele, McKennitt's version asks us to consider the transitory nature of acts of healing, of learning, of power and might, all of which prove to be ephemeral. This makes sense as a recasting from scene to song; rather than end with a graveside blessing, the song now applies more universally, for all of us, not just the song's target, will someday face oblivion.

Table 1 'Fear No More', from Shakespeare's Cymbeline, Act IV scene 2. Bold indicates verbal repetition.

Table 2 Form and borrowing in McKennitt's ‘Cymbeline’

McKennitt also introduces a verbal repetition of Shakespeare's lines 11 and 12, absent in the original, and does so in ways that reposition them musically. The first time, they are set as cadential lines, coming down to the comforting arrival on the final at the end of the higher-tessitura quatrain.Footnote 3 The power of this resolution is highlighted by the quatrain's use of paired parallel lines. The exploration of the mode's upper tessitura, which starts with an ascending fourth (the largest upward gesture of the song), is immediately matched through a parallel phrase. McKennitt then pivots to repeat the familiar closure melodies (b and bʹ), pairing the open cadence with its closed answer. Notably, the return of familiar ambitus, tessitura and melodic phrase, and its immediate varied restatement is matched to the speeded-up arrival of rhyme in the quatrain. We experience both melodic and verbal compression.

The second time she visits these lines, however, McKennitt repositions them. Although the words reappear verbatim, the lines are no longer set as closure to the ideas presented but instead matched to the urgent upward gestures that starts the second quatrain's music, and cadence inconclusively below the final. Since there is a single quarter note from which the sudden leap emerges in place of the double anacrusis of most phrases of the song, and since the word ‘sceptre’ stands out in height of pitch and rhythmic placement as a kind of double emphasis, we seem to be invited to hear this line and its textual partner from a new perspective. We are prompted to ask – both in song and retrospectively in Shakespeare – if it is the act of striving, rather than its inevitable endpoint, that is the cause of the singer's pain. Indeed, this reconstituted quatrain becomes a listing of losses: sceptre, learning, physic, all lovers young, all lovers in toto, in sum all things ‘must … come to dust’. Just as the experience of the end of the first half of the song offered a compression through tighter repetition, this second half of the song reminds us that it is also an intensification, the things to be lost and the loss itself coming faster and repeatedly.

For McKennitt, Celtic musical elements complement the meditative nature of each text. The presentation is predominantly syllabic, with a few small ornaments to decorate cadences. It adopts a narrow musical ambitus – mostly holding to less than an octave – and neo-modal presentation based on d but with b-flat – a transposed aeolian. Harmonically, we find heavy use of the subfinal (c), both melodically as the point of arrival for the cadences of the first and third line, and harmonically, for the second line arrives on the fourth scale degree, G, set to a harmonically unstable C major triad. Not until the end of the quatrain do we arrive on the final itself, with a cadence from above. ‘Prospero's Speech’ works similarly but employs a falling-third cadential gesture. The absence of leading tone-based harmonies in both songs clearly shifts us out of the normative tonality of much popular music and into the folk/antique idiom. McKennitt's setting invokes one further aspect of framing, for the instrumental prelude and postlude of ‘Cymbeline’ feature sitar and harp, superimposed, as Folkerth puts it ‘over low synth drone’ (Folkerth Reference Folkerth and Burt2007, p. 370). This mingling of Eastern and Western idioms lays out the melodic elements that will become the vocal line, but also provides an unstated meaning: multiple musical idioms can conjoin to make a broader musical whole. Calvo-Sotelo (Reference Calvo-Sotelo2017) traces such crossovers of Western and non-Western styles to McKennitt's broader views of ‘Celtic’ as a global and sometimes diasporic phenomenon, one reflected in her travel-based explorations of what she considered to be Celtic elements.

McKennitt's use of Shakespeare forms part of her broader strategy of literary borrowing. Known for employing lyrics from Dante, William Butler Yeats, Shakespeare and St John of the Cross, among others, these literary figures become an important part of the critical reception of her works. Critic Nick Krewen, for example, argues:

considering some of her lyrical partners brandish such last names as Blake, Tennyson, Keats and Shakespeare, you could be forgiven if you felt as if you were in a bit of a time warp … McKennitt's approach is to take traditional Celtic folk songs or literary works, and adapt them to her own music without sacrificing the mood or dignity of their historic significance. (Krewen Reference Krewen1992b, p. D1)

Likewise, reviews of her fifth album, The Mask and Mirror (1994), such as those in Toronto's Words & Music ([Anonymous] 1994, p. 13) and in Melbourne's The Age (Gibson Reference Gibson1994, p. 4), mentioned her poetic indebtedness to Shakespeare and others at significantly more length than her musical innovations. That is, her poetic indebtedness to these historic authors, and not her Celtic sound-world, becomes the focus of critical attention. Fans too capitalised on these literary antecedents, sharing the borrowed lyrics, giving their context, and occasionally linking them to a personalised experience of the song. Fans observe that ‘it's Shakespeare's play turned into music!!’ (M. Ellis, 11 March Reference Ellis2010) and proceed to explain the context of the song. ‘The lyrics are about passing from this life, how all people, from the beautiful to the lowly, must pass from this world, it's [sic] pleasures and hardships, and their bodies turn to dust’, says billybareblu (4 November 2017). ‘It's a reminder of the inevitability of death, and how even the most beautiful things (like young love) are destined for the same fate’, offers George Stark (5 March Reference Stark2020). Like the critics, these fans find the music ‘amazing’ and ‘moving’, but they do not comment in detail on the song's structure – not even on its unusual length. They do, however, draw parallels between the two sides of this transcoded relationship: ‘I wonder if Shakespeare's words affected his audience in the same way this song does for its fans’ muses Steve Eisler (12 October Reference Eisler2021). Such comments are notable not only for their presumption that literary exegesis is important to song meaning but also for the way that other fans respond. Across the repertoire of what we could call McKennitt's trans-temporal collaboration – her borrowings from poets of the past – it's the game of spot-the-source that is most likely to result in upvoting by other fans. This suggests that a literary reception is shared among these avid listeners, and, equally, that fans may be better prepared to discuss literary considerations of the songs and their contents than they are to respond to musical choices in more than a visceral way. They admire the music, but they do not discuss it at any length.

* * *

If McKennitt crafted music to function at the level of the structured scene, the women of Ensemble Galilei entered into the project of developing an entire Shakespearean CD at the suggestion of their new record label, Telarc (Felter Reference Felter2000, p. C1). Their album, Come, Gentle Night, then, reflects a strategy of research and reflection. While they were aware of the legacy of more modern Shakespearean settings ranging ‘from Mendelssohn to Brubeck’, as performer and founder Carolyn Anderson Surrick recounted in interviews of the time, they were interested in finding a 16th- and 17th-century repertoire that fitted the dramas. To support that quest, they ‘played through hundreds of tunes searching for jigs, lute songs, reels and country dances that might have accompanied the dramas’ (Sherman Reference Sherman2000, p. 8). The resulting album is entirely instrumental. Much like Such Sweet Thunder, the jazz instrumental numbers of Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn studied by Stephen Buhler, Shakespearean allusions of Come, Gentle Night can be found only in the titles, the liner note descriptions and the musical gestures that might call to mind significant moments in the plays. In all, the Ensemble Galilei album includes 34 musical numbers across 19 short sets – what Buhler might call ‘vignettes’ (Buhler Reference Buhler2005, p. 2). Of these, 14 of the Ensemble Galilei items come from partbooks and early prints (five are from Playford 1651, and five more from later Playford editions, for instance); another nine items come from a mix of works by early modern composers and traditional repertory; and 11 are newly composed (or heavily recomposed) by members of the ensemble.

The chronologically diverse repertoire for Ensemble Galilei ties into the question of pastness and periodisation. Notably, many of their sets cross chronological boundaries, mixing 16th-century and traditional numbers. The Midsummer Night's Dream set, for instance, draws on an anonymous Scottish tune from Thomas Wode's Part Books, dating to the later 16th century, a Hornpipe from Playford 1701 and the Third Act Tune from Purcell's Fairy Queen of 1692. In this neo-modal environment, similarities in style outweigh the obvious differences in musical language, inviting the listeners to experience a seamless fusion of past and present musical expressions.

Like the titles and verbal evocations that make Bruhn's musical ekphrastic repertory ‘patently representational’ (Bruhn Reference Bruhn2001, p. 565), the liner notes and titular references of Come, Gentle Night draw on 10 of Shakespeare's plays and a sonnet. The allusions are clearest, predictably, in the newly composed repertoire, which typically uses a fragment from the play as dance title. The combination of strathspey and reel by Deborah Nuse, ‘But Let Them Go/Ladies, Sigh No More’, both derive from Much Ado About Nothing. Both catch-phrases derive from Balthasar's song from Act 2 Scene 3, although the musical order is inverted, with the bid to release concerns about men's constancy (line 5 of the song) coming musically before the song's principal injunction to ‘Sigh no more’ (line 1). It isn't the ordered representation that matters here but rather the quotational one. The two sections, both in a major key, serve as ‘blithe and bonny’ music that the ladies of the play are called upon to deliver. The strathspey can easily be distinguished from the reel even by non-experts, for in addition to a shift of melody type and move away from the scotch snap, the drone drops out and we simultaneously change from Scottish small pipes to fiddle. There are many ways to be happy, suggests the music, in keeping with a key takeaway of the play: that fulfillment and joy can be found in trust and transparency in relationships. In other numbers from the disc, a traditional tune might be matched to a more direct Shakespearean citation; the jig and reel that draw on the traditional tune ‘Jack's Health’ (known elsewhere as ‘Bolt the Door’) are matched to Othello's musings about his age, ‘Vale of Years’, in a thematically as well as musically sensible linkage.

Ensemble Galilei's approach to the musical landscape is not designed as a drop-in solution for Shakespeare productions, for it is neither reconstructive nor a testament to a once-historic performance. Instead, the group focuses on combinative sets that link several tunes together. Indeed, these tracks seem to function as ekphrastic responses to the plays, for they touch on key moments and moods rather than matching up with the musical needs as outlined in stage directions. The same could be said for the Ellington and Strayhorn suite examined by Buhler or the ekphrastic examples of Bruhn's various studies. Borrowed from the Greek word for ‘description’, ekphrastic works rephrase something in another art form. Transmedial and interpretive, they come at the first artwork's principles with a different set of artistic tools. For Ensemble Galilei, the use of Scottish pipes with simple harp accompaniment for the Irish Lament captures something important of Ophelia's circumstances, for instance, and the interweaving of the contrapuntal – and slower – recorder line at the end of the song resonates with the heroine's increasingly complex woes. Shakespeare would not have thought to use such instrumentation, but we as listeners can draw uncomfortable parallels of Celtic sorrows (such as colonial oppression, famine or more personal griefs that may have motivated the original lament tune) and dramatic ones familiar from our memory. In other words, by connecting an anonymous lament from the period of Tudor incursions into Ireland with the narrative of Ophelia, a character entangled in a realm where external pressures force her away from her genuine emotions and disrupt her grip on sanity, Ensemble Galilei do more than merely pinpoint a shared emotional tone. Instead, they appear to highlight the devastating outcomes of power conflicts and their impact on the innocent. In this way, Celtic musical ekphrasis is akin to its orchestral and chamber music relatives, in that the transmedial re-presentation is transformative, and in Bruhn's words, ‘changes the viewer's focus [and] guides our eyes toward details and contexts we might otherwise have overlooked’ (Bruhn Reference Bruhn2001, p. 560).

Come, Gentle Night also incorporates a trans-temporal dimension to its transformative reinterpretations, displaying a consciousness of the present in the way it proffers new pieces alongside the old. This element intrigues critics. Washington Post reviewer Mike Joyce, for instance, reports that their music was ‘drawn from ancient English, Scottish and Irish traditions, untarnished by time and brimming with melodic charm and rhythmic verve’, and sees the result as an ‘enchanting album [in which] Ensemble Galilei imagines what the music that filled the Globe Theater in Shakespeare's day might have sounded like’ (Joyce Reference Joyce2000, p. 7). His vocabulary plays with ideas of time. These tunes are ‘ancient’, ‘untarnished by time’ and thus with their achronometric branding might attach themselves to ‘Shakespeare's day’ in the audience's understanding, with ‘ancient’ and ‘Shakespeare’ blending into a weirdly non-specific past. Other reviewers offered praise but were more aware of the need for chronological generosity. ‘If some mid-to-late-17th-century choices were a stretch for the Bard of Avon, who died in 1616, the tunes all worked beautifully together’, reported Sarah Bryan Miller in a typical review. It was the stylistic familiarity of ‘folk melodies from the British Isles’, along with a sense of stylistic appropriateness for the words, and not historical accuracy, that carried the day (Miller Reference Miller2000, p. D2). This positive response generally extended to the items newly composed for the album; these were seen to ‘honor the Bard and his words’ (Joyce Reference Joyce2000, p. 7). Fans responded positively too: ‘The music of this CD is as full of passion, grief, joy, humanity, humor, play and pathos as Shakespeare's own body of works’, claimed Tinker. ‘Ensemble Galilei pours their hearts and talents into the various pieces, whether they are resurrecting traditional works, or birthing new ones’ (Tinker, amazon.com review, 27 July 2000).Footnote 4 Indeed, critics and fans alike agreed on the positive linkages between Celtic style and Shakespearean ethos. As critic Bob Crimeen put it, ‘Producing a sound that is pure Celt, these New World women piece together music from four centuries to create a musical patchwork that would have made the Bard beam had Ensemble Galilei been the Globe Theatre's resident instrumentalists’ (Crimeen Reference Crimeen2000, p. 84).

* * *

Unlike Ensemble Galilei and their ekphrastic Shakespeare miscellany, Méav gives us Shakespeare as an exemplum, one text among an array of others ranging from a Kurt Weill song to Faure's ‘Les Berceaux’ to Scottish and Irish traditional airs. She includes Shakespeare's ‘Full Fathom Five’ (The Tempest I.2) on her second solo album, Silver Sea, as one of six English offerings alongside three Irish, two French and two mixed-language songs. As the vocalist–composer said in an interview at the time of the album's release, ‘I chose all the tracks on Silver Sea myself, and produced it myself, so it feels more personal to me than the first one now’ (Elliot Reference Elliot2002). She characterised the album as ‘a mixture of traditional, modern and classical melodies’, and noted that ‘I like sounds that seem as to have been around for a long time, even if they haven't’ (Wynne Reference Wynne2002, p. 26). As an artist, in other words, she is drawn to the same kind of temporal and stylistic eclecticism as were Ensemble Galilei.

The response to Méav's Shakespearean setting – like that to her album – was positive. Seeking to position Méav's new music for her Korean fans in advance of her 2002 tour, critic Elizabeth Pyon (Reference Pyon2002) found that two songs of the album and related tour stood out: ‘Full Fathom Five’ and ‘I Dreamt That I Dwelt in Marble Halls’ – the one based on Shakespeare and the other a song borrowed from Balfe's The Bohemian Girl (1843) that hearkened back to Enya's popularity with the same piece a generation earlier. Likewise, self-identified ‘Irish listener’ Annie of Dublin gave a long response which shows her awareness of the work's literary background as well as her fondness for the music:

Full Fathom Five – This is a special track, as it is Méav's own creation. She composed the lilting, haunting melody, which suggests very vividly the slightly sinister quality that the sea can have. Her choice of lyric is intriguing too, as she uses an ancient Shakespearean text from ‘The Tempest’ which describes the watery grave of a drowned man, and which is apparently the origin of the phrase ‘sea-change’. Both in music and voice this song flows, and has a sense of lullaby that I love. (Annie of Dublin, n.d.)

For Annie, the connection with Shakespeare draws us into ‘ancient’ times, and fits in a world in which Shakespeare (our verbal hero) generates words and phrases. She's interested in his verbal coinage of ‘sea-change’, and summarises the content of the lyric. Her musical assessment is emotive: the music lilts; it's haunting; it flows; it is like a lullaby. Other fans characterise the song as ‘mystical’.

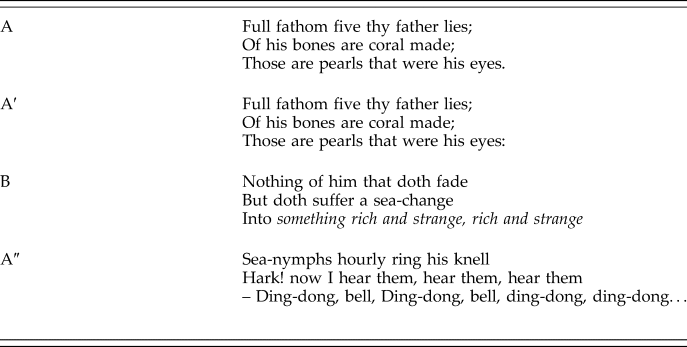

An analytical assessment shows that the song, for all its appeal, is melodically simple, largely bounded within an octave plus lowered subfinal for cadences. The Dorian tune is centred on the final, with which it starts and ends, and on the confinal where it spends much of its time in longer-held notes. The vocal line starts with a leap from final to confinal, for instance, and then fills in; the arched shape of line two moves up to a flat-7 to octave arrival at its peak for the word ‘coral’ before falling back to the confinal. The final phrase of the tercet dips below for another flat-7 to final cadential gesture, absent the markers of leading tone-to-tonic resolution of most pop, as if to emphasise its modal nature and harken back to the (traditional? Shakespearean?) idioms of folk or historicised music-of-the-past. This is superimposed over an ostinato harp accompaniment that evokes the waves of the sea.

Rhythmically, harmonically and texturally however, the song is more complex than it might seem at first hearing. Tensions between an implied compound duple metre for the first phrase with triple metre for the second play out in the melody, and the slight swing in the vocal rhythm further deflects a firmness of metrical anticipation. Likewise, the sudden cadential move at the end of the first tercet foreshortens Shakespeare's quatrain, deferring his fourth-line rhyme until after the initial tercet is both verbally and melodically repeated. The juxtaposition of voice and harp generate harmonic complexities as well, although the ear forgives the many unresolved dissonant intervals by virtue of the combination of implied pedal and ongoing ostinato throughout the majority of the song. Like the melodic language, the static nature of the accompaniment coupled with the independence of the lines (an independence that evidently overrides the need for contrapuntal resolutions) and the absence of leading-tone functionality draw us further into a musical context that invokes past musical styles. Texturally, too, Méav highlights vocal imitation, which hearkens back to past idioms, although it is always inexact. The second iteration of the first tercet (Aʹ on Table 3) introduces this imitative overlay, in a digitised and seemingly canonic writing, although the ‘pearls’ of the text elicit a slight ornamentation in the lead voice that differentiates the two lines melodically. The shift in the two voices’ relationship sets up the more animated rhythm which prepares for the ‘sea-change’ and the contrasts of harmony for the words ‘rich and strange’. The melodic outline of the very beginning returns for the Sea-nymphs of what is constructed into a final tercet. The nominally canonic voices share back and forth the various motives in a three-part stream, though of variable distance. The statement and two echoes of ‘ring his knell’ are separated at the distance of a measure, but rhythmically tighter echoes of rising and falling fourths for ‘hear them’ are spaced only a beat apart, the act of Ariel's hearing emphasised through proximity and reiteration as well as by upward leap. The piece ends with a fade-out on the ‘ding-dongs’ of the verbally referenced bell.

Table 3 Méav's setting of ‘Full Fathom Five’, Ariel's song from The Tempest, I.2

We, audience to the Celtic piece, may think of Gonzalo's ‘humming,/And that a strange one too, which did awake me’ or of Caliban's explanations of the isle as ‘full of noises’, but in its Shakespearean context, Ferdinand diegetically hears only the words of the song, seeing neither Ariel, its singer, nor the things he evokes: not bones, nor eyes, nor pearls, nor coral, nor even bells to explain this music which ‘crept by me upon the waters,/Allaying both their fury and my passion/With its sweet air’. Ferdinand has been willing to follow the sound of these songs – along with barking and rooster crows – and they have brought him some measure of calmness after the tumult of the storm. And yet, like ‘Cymbeline’, this song falls within a Shakespearean moment of deception. Despite Ariel's claims, Ferdinand's father is not dead, nor will his bones become coral. Although he – they – will be changed by events on the island, it is not into the bones of a shipwreck victim but into a more human character with deepened empathy. Moral growth rather than decay will be forthcoming. Méav's context focuses on the magic of the moment. The harp and naïve, breathy voice coupled with melodic simplicity, the harmonic wash generated by the ostinato and the imitative chase of voices signal an innocent playfulness, rereading Ariel not as fearsome but winsome in nature – a tease, not a terror.

These various Shakespearean settings offer an element of what I think of as ‘restitutional creativity’. Shakespeare is the inspiration for these Celtic remakes, but the musicians are not just quoting old ballads from within the plays. Nor do they centre their musical language in that English folk tradition adapted for Shakespearean usage by musicians such as Cecil Sharp or Laura Marling, even though that tradition sits more properly within a Shakespearean lineage (Hansen Reference Hansen, Wilson and Cooke2022). Instead, the artists of the Celtic idiom seek to cut across cultural differences to repossess the Shakespearean nugget. Indeed, I believe that in part this restitutional creativity of these Celtic creators is pushback on critics who emphasise the glitz and glamour of the acts at the expense of musicality or cultural positioning of the artists themselves. The use of a dozen or so lines of text in the songs point to direct borrowing, yes, but even when the words are present, they are reshaped by structural displacements to create a coherent and metonymic whole. As we have seen, both McKennitt and Méav quote the words of Shakespeare in near-verbatim form. Nevertheless, they deliberately chose an inexactness of structure as the space in which to create the balanced short-forms of song. It is not a replication (pace Hutcheon Reference Hutcheon2006) of the Shakespeare text, but instead a collaborative reframing of it. The Ensemble Galilei artists too use the spaces of the plays and the ideas invoked, but they neglect the poetic element except as title or allusion. Shakespeare, then, is a source of generative musical creativity, but the Celtic music creators respond not just to the texts but to the spaces and gaps that the plays provide.

Moreover, for critics and for fans, the merger of Celtic musical idioms with Shakespearean texts and contexts proves a satisfying choice, ‘old’ sounds matched to ‘old’ poetry. Given the tensions of colonial and post-colonial identities, however, a more nuanced reading emerges from performers’ choice of deliberately archaic language. This stylistic choice, which transports the listener to a different time period, serves at least in part as a kind of cultural reclamation. By infusing the popular idiom with musical elements (such as modes, rhythms or melodic contours) of bygone eras, the performers of these Celtic works point towards an alternative aesthetic narrative, one that challenges presumptions of cultural superiority.

Archaic style, in other words, asserts a declaration of cultural sovereignty, emphasising the richness and depth of Celtic heritage while simultaneously questioning the homogenising effects of colonialism. It does so in three ways. First, it asserts an equality of the Celtic and the Shakespearean traditions, resisting reductive colonial narratives that may have cast Celtic culture as backward or inferior in comparison with the grand Shakespearean corpus. This kind of cultural reclamation puts the performers’ own cultural heritage on a par with the voice of Shakespeare for this modern-day audience. Second, the merger of Celtic music and Shakespearean texts becomes not only a creative reinterpretation but also a vehicle for deconstructing and reconstructing the historical and cultural forces that have shaped identities. In essence, the act of merging Celtic music and Shakespearean texts becomes a vehicle for artists and audiences to explore and challenge the historical and cultural factors that have shaped their identities, offering a more complex and nuanced understanding of both the past and the present. Finally, the resultant hybridity can be seen as emphasising the diversity and resilience of ‘Celtic’ cultures. The old-fashioned styles posit a continued relevance of an independent non-colonialist identity, replacing a narrative in which those former times become a creative wellspring despite colonial oppression. Using antique Celtic idioms instead of English folk borrowings can be read as a complex act of resistance.

Fandom and the Celtic conundrum

Desmet reminds us that an audience co-creates the awareness of borrowings. This is certainly true for the repertoire by these three Celtic groups, as we have seen. Fans share their identification of the allusion or source of inspiration, name-dropping Shakespeare and putting on display their personal familiarity with the plot, character or circumstance that provides a context for the piece. Like critics, they seem to prefer the literary game of identification over any consideration of analytical elements such as song form or even instrumentation. Fans do, however, acknowledge what they believe to be emotional parallels between the music and its model; they claim such parallels as a sign of positive linkages between the two works of art.

What, we might ask, is at stake in such claims? Why does this game of listening-as-identification matter to this audience – these fans? It is, I would argue, in part a question of demonstrating belonging in the fan group itself. Johnathan Pope, for instance, reminds us that ‘fan’ is an active identification (Pope Reference Pope2020, p. 5). While Pope examined a different community of fans – those contributing Shakespearean ‘fanfic’ in online forums – the construct of his group's identity has similarities with our group of Celtic music fans. Both engage through written communication in social media spaces. Both wax enthusiastic about the topic at hand in ways that may seem over-the-top to outsiders: to ‘squee’, as Pope says. After all, to be a fan is, as Mark Duffett frames it, ‘to find yourself with an emotional conviction about a specific object’ (Reference Duffett2013, p. 30). And both groups trade in a kind of constructed expertise in the target subject matter. For Celtic music fans, then, the personal anecdotes regarding their encounters with a particular musician, the more esoteric details of observational engagement – details of costume, dance step, or fiddle lick – and comparisons across the repertoire are coinage in the realm of fan-group belonging. And such things work. The more detail is provided, the more likely the post is to be upvoted or added to through others’ commentary.

To understand what this engagement ‘does’ to Shakespeare, it is important to recognise that for both Pope's fanfic contributors and our Celtic music fans, it is the ‘circumstances of plots, specifics of characters, not the beauty of [Shakespeare's] poetry’ that seem to matter most (Pope Reference Pope2020, p. 124). We have moved what we might call Shakespeareanness to a symbolic, even totemic touchstone, pointing toward a connectedness that transcends temporal barriers. As Hansen observed for popular music in general (and psychedelia in particular), ‘citing a totemic, canonical, dead white male’ was part of an ethos of turn-of-the-century cultural mixing, with references to Shakespeare emerging ‘in fractured, half-remembered ways’ (Hansen Reference Hansen2010, p. 98). For Celtic music fans, it is possible to be equally enthused about the wordless allusions of Ensemble Galilei, the textually restructured scenes of McKennitt, and the evocative and regularised song-setting of Méav, for all are taking place in a realm of connectedness. As Desmet established, originator, appropriator, and observer form a triad. She asks, ‘Under what circumstances and in what physical, psychological, or cultural conditions, does the resemblance between one work and another “click,” convincing us that they are engaged with each other?’ (Desmet Reference Desmet, Huang and Rivlin2014, p. 54). In the Celtic music environment studied here, one gains credentials as a fan by displaying that awareness of that connectedness.

A second element that fans address is a temporal construct coded variously as nostalgic, antique or old. Of course, Celtic imagery is, in our modern iteration, conventionally mapped to the olden days; the Celtic knot and Celtic cross with their medieval overtones are frequent adornments to Celtic branding more generally. Celtic music, with its similar coding of neo-modal and de-rhythmicised ‘antiquity’, fits comfortably not just with the folk idioms and ideas of ‘tradition’ but with a sense of Shakespeare too as timeless. This is serious-seeming nostalgia. We are provided with dreamy music to go with a chronologically distant author. The almost incantatory nature of McKennitt's Shakespeare songs, for instance, exists in a different rhythmic and metric space than the other, more energetic numbers on the same albums.

Similarly, when critics of Come, Gentle Night like Joyce reference ‘what the Globe might have sounded like’, they afford the album a chronological generosity in which Henry Purcell and the 1715 death of Pawky Adam Glen are superimposed over a Shakespeare contemporaneous with Henry VIII (!) and with the 20th-century offerings of new musical material. Likewise, with Bob Crimeen's evocations of a beaming bard, Shakespeare is evoked as a happy collaborator in the ghostly temporality of a stylistic musical now. For Celtic music in particular, the power of the metaphor of timelessness, evoked in the epigraph and narrated by fans and critics alike, situates the music against a mythology of folk culture of a foggy, imprecise past.

In her examination of the constructed identity of Irishness in the context of Chicago's Columbian Exposition of 1893, Shahmima Akhtar has observed that ‘nostalgia is not always about the past; it can be retrospective but also prospective in the sense that it held the potential to display what a future Ireland could look like’ (Akhtar Reference Akhtar2023, p. 551). So, too, the engagement of fans with Celtic music and its connection to Shakespeare reflects a temporal nostalgia that speaks both to the past and a sense of a potential shared future. Fans derive a sense of pride from their knowledge of the seeming ‘pastness’ of the Shakespearean allusion, yet they equally cherish the dynamic nature of the musical soundscape, where modernist iteration and historic instantiation of a Shakespearean moment can coexist in their listening experience. Furthermore, a triumphant Celtic musicscape integrates ‘Shakespeare’ as a common, diasporic, shared legacy – the Celtic element within Shakespeare now matched to the externalities of a Celtic style. For fans, in other words, the fascination with Celtic music and its intertwining with Shakespeare embodies a duality like that experienced by Akhtar's fairgoers; their enjoyment of this Celtic Shakespeareana reflects not only a yearning for the past but also an aspiration towards an imagined future shaped by a shared Celtic cultural heritage. The music and its text, the energy of the performers, and the excitement of the audience coalesce around a vision of a globally approachable Celticism.

Conclusion

Popular music studies of Shakespearean settings have tended to focus on the large-scale appropriations such as the musical (Dash Reference Dash2010; Sanders Reference Sanders2007) or the small allusive gestures of quotation and citation – parallels in naming (Juliet in Buhler Reference Buhler and Burt2002; Ophelia and Desdemona in Buhler Reference Buhler and Shaughnessy2007) and allusive reference to Shakespeare in genres ranging from pop, rock, and rap (Hansen Reference Hansen2010) to jazz (Buhler Reference Buhler2005) and beyond. Celtic performers’ use of whole lyrics excerpted from Shakespeare and of an assortment of chronologically diffuse dance numbers seems on the surface an unremarkable, even traditionalist approach to appropriation. Yet the use of formal restructurings and ekphrastic evocations alongside the shift of musical idiom into a distinctively Celtic-folk realm functions to remap the original lyric into a new interpretive world. These transmediated Shakespearean offerings do not form a particularly radical act of appropriation. They lack the overt political overtones of the English folk reconfigurations in nationalist English productions of Shakespeare discussed by Hansen (Reference Hansen, Wilson and Cooke2022), for instance. Nevertheless, fans tell us that their intertextual indebtedness is part of the attraction of these pieces; the lure of the familiar (and the opportunity to play the identification game) is an element that adds aesthetic pleasure to their reception. Furthermore, the deliberate disconnect of Celtic/Irish rather than English folksong traditions opens a space for a colonial-resistant reading of these texts, a pairing of the traditions as equal, with Celtic autonomy on display alongside ‘Shakespeareanness’. As suggested above, the force of ‘Shakespeare’ and his many associations does not subsume the ‘Celtic’, but is, instead, in dialogue with it.

Similarly, the archaicising musical elements – admittedly familiar from a number of popular genres – are particularly poignant in combination with the textual linkages to Shakespeare and its import for diachronic collaboration in the Celtic music environment. We can recognise in such collaborations the creation of an overlap of timeline, a tangible reach to the past as an active element of the present day. Shakespeare is imagined as an auditor for the repertoire; his presence at the Globe Theatre and our presence in the listening venue for the current performance are equated. Guido Strässle (2 August Reference Strässle2021), for instance, judges McKennitt's ‘Prospero's Speech’ to be jenseits von Raum und Zeit (‘beyond space and time’). The music – performed and often crafted by the contemporary musician – is deemed ‘ancient’, a word used almost as loosely as is ‘tradition’. In these songs and dances, in other words, fans claim to see the folk narrative of timelessness enacted both through an engagement with a poetic past and through a musical language that has itself claims to what (for them) is an unmeasured ‘pastness’. In much the same way that neo-Gothic architecture informs the American college campus, the neo-modal idioms of these Celtic pieces resonate with a (newly generated) folk tradition that is in the process of being actively constructed in these ‘new offerings’ since they share the programme with pieces found on any number of Irish Traditional albums. This, in other words, is not an inherited past but a created past, one that we can see enacted by the musicians through their careful staging of the antique within these broader heterogeneous concerts and videos.

These Celtic Shakespearean settings also inhabit the world of the miniature, working collaboratively with Shakespeare on both ekphrastic and metonymic dimensions. Our musical Shakespearean worlds are short, roughly 2–6 minutes in length. As discussed above, the songs and dance sets rely on mood-setting and evocation more than character and speech-rhythms. The slow melancholic iterations of Ensemble Galilei's ‘Winter's Tale Set’, for instance, gradually warm up into the more lilting language of carol and of flirty English country dance to provide the story's happy ending. Yet while we get moments from the story arc, we have no specifics of the play's characters, nor the moment of the enlivening of the statue, nor even reference to the play's famous stage direction, ‘exit, pursued by a bear’ (The Winter's Tale, III.3). It is the auditor who must supply these bits of story from memory or consultation. Similarly, McKennitt's use of The Tempest as basis for ‘Prospero's Speech’ calls upon the audience's familiarity with Prospero's epilogue and its request for the ‘indulgence’ to ‘set me free’ – an applause which acknowledges the whole of the play, or perhaps the whole of concert, given its shifted circumstance. Yet she chooses not to name the Island, Naples, nor even the forgiveness that allows for the resolution of the play; those are the audience members’ details to supply.

In an environment in which Celtic music is a consumer-focused genre, centred on ‘record bins’ and musical sales, perhaps controversy and post-colonialist take-downs of the empire and its associated poet would be inappropriate. The language of reviewers often criticises the glibness of these performances, designed to entertain rather than to provoke. In a world of ticket-sales and public television specials, the studied neutrality of the performances, more glamour than substance, nevertheless spoke to an audience that engaged with and enjoyed the musical and textual variety of these modern-day variety shows. When she introduced ‘Cymbeline’ in her live performances, McKennitt chose to provide the song with its context in the Roman-Celtic tensions of historic England. However, having evoked the conflict, she immediately moves on to what she situates, implicitly, as cultural mediator. In her words: ‘I'd like to leave the last word to Shakespeare’. Yet we should remember that while Shakespeare may have the last word, what we do with that word, and the musical world it inspires, is in fact a function of the intersection of songwriter, performer and audience. It is, in other words, a negotiated truth. For that is the reality of this commercially popular, even glitzy Celtic music repertoire. Its appeal may be inspired by its sources, be they traditional or inherited, but the meaning it creates is in the ear of the listener.