Introduction

The nature of urban transformation in North Africa in the late antique and medieval periods has dominated scholarship for the past three decades. The traditional orthodoxy held that the so-called ‘granary of Rome’ in north-east Africa, which had experienced a period of unparalleled urban prosperity under Roman rule, began to unravel in late antiquity and had disappeared almost entirely in the middle ages (Lepelley Reference Lepelley1979; Baratte Reference Baratte, Panzram and Callegarin2018). A far more complex picture of the late antique city has emerged in recent years. Scholars now broadly agree that the fourth and fifth centuries were a time of urban prosperity in much of Africa, though the degree and timing of public investment, church-building and the abandonment of pagan buildings varies considerably at different sites (Thébert and Biget Reference Thébert and Biget1990; Leone Reference Leone2007: 45–166; Reference Leone2013). The Byzantine period is now seen as having more continuity from a prosperous Vandal period than previously believed, and the seeming ‘deurbanization’ and fragmentation of towns, their industrialization with oil presses and disruption with burials, are now frequently pushed back to the seventh century or later in North Africa (Leone Reference Leone2007, 167–280; Stevens and Conant Reference Stevens and Conant2016).

Far more controversial is the question of urban life after the Arab conquest of Carthage in 697/8 with scholars divided on how to interpret the evidence for the eighth century, largely on disciplinary lines. Medieval archaeology in Tunisia is still in its infancy in comparison to Roman or late antique archaeology and it continues to prove very challenging to identify seventh–ninth century activity (Fenwick Reference Fenwick2020, 7–30). Nonetheless, by mapping towns with direct or indirect archaeological or written evidence for early medieval occupation, scholars have identified some broad regional patterns in long-term urban success and failure in the early middle ages (see Fenwick Reference Fenwick2013; Reference Fenwick, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019, 138–42; Reference Fenwick and Hitchner2022). The medieval urban network was based on that of the late antique period: only two new towns were founded – Kairouan and Tunis – in the eighth century and as a result, large, populous Romano-Byzantine towns at strategic points across North Africa continued to thrive and serve as important medieval centres. Alongside this urban continuity, there is a significant and undeniable scale of loss of total numbers of towns by the ninth or tenth century. Some regions were affected more than others. Proconsularis, extremely densely urbanized in antiquity, had far fewer towns in the middle ages than in late antiquity and notably even Carthage, the capital, was reduced to very little in this period (Stevens Reference Stevens, Stevens and Conant2016; Fenwick Reference Fenwick, Panzram and Callegarin2018). Small towns in the north of Tunisia seem to suffer disproportionately compared to other regions – a trend that appears to be confirmed by recent excavations. Work at Chimtou, Bulla Regia, Uchi Maius, Dougga, Althiburos, Abthugnos and Zama Regia suggests a complicated picture of urban collapse, continuity and re-settlement (Thébert and Biget Reference Thébert and Biget1990; Gelichi and Milanese Reference Gelichi and Milanese2002; Ferjaoui and Touihri Reference Ferjaoui and Touihri2003; Touihri Reference Touihri, Nef and Arcifa2014; von Rummel Reference von Rummel, Stevens and Conant2016; von Rummel and Möller Reference von Rummel, Möller, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019). Nonetheless, though many of these sites were occupied in some way in the ninth or tenth century, these settlements had either lost their municipal function or were not sufficiently important to be noted as towns in the accounts of the Muslim geographers. In Byzacena and Numidia, in contrast, where urban sites largely cluster along the main east–west routes or on the coast, there is a less sharp drop in total numbers of urban sites (see e.g. Stevens Reference Stevens, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2020). Further to the east, in Tripolitania, where the major urban centres were always constrained to the coast and good anchorages, there is no evidence of early medieval abandonment.

Such regional trends of urban continuity, abandonment and re-occupation suggest that there may also be clear regional distinctions in urban investment and building trends, as has been identified for the Numidian and Roman periods (Scheding Reference Scheding2019a; Ardeleanu Reference Ardeleanu2021). As yet, a lack of sites with both well-documented late antique and medieval levels has prevented nuanced comparison of urban investment at the regional scale. This article therefore offers a preliminary examination of regional change from the fourth to the eleventh century through a comparative analysis of a zone within the Central Medjerda Valley in north-west Tunisia, which was densely urbanized in antiquity, but is poorly understood in the middle ages. The region is currently the focus of the joint Tunisian-British-German project ISLAMAFR: Conquest, Ecology and Economy in Islamic North Africa: the Example of the Central Medjerda Valley, which seeks to understand the economic and social transformations triggered by the Muslim conquests and subsequent regime changes. In this article, we focus on a stretch of the upper Central Medjerda which contains two of the most comprehensively studied archaeological sites in Tunisia: Bulla Regia and Chimtou. Both sites are depicted in the scholarship as exceptional Roman towns: Chimtou for its marble quarries, and Bulla Regia for the uniqueness of its elite, subterranean housing. This narrow focus has stymied discussion of how these neighbouring towns and surrounding lesser known, but still significant, settlements may have undergone similar or disparate changes over time. We first place these towns within their regional setting, including the characteristics of the landscape and a shared early history of settlement. We then compare the urban transformations of Bulla Regia and Chimtou, as well as details from the largely unexcavated settlement of Bordj Hellal, according to a series of themes: public investment, religious investment, housing investment and ceramic networks. By adopting a diachronic and regional perspective, the discussion pulls out the many ways in which the trajectories of the towns converge and diverge.

Geography and settlement

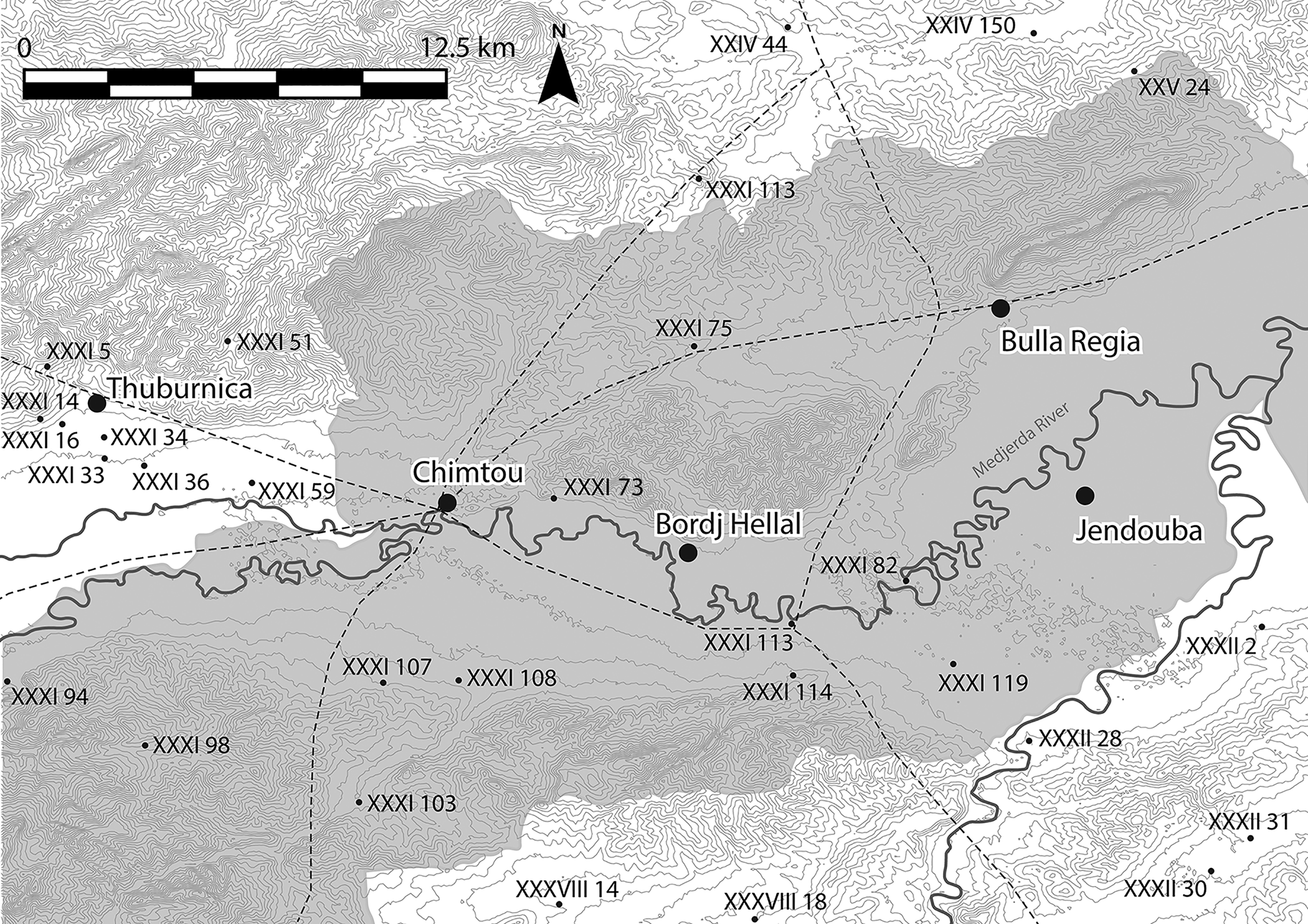

The Medjerda Valley was of fundamental importance in the Roman and medieval periods for producing agricultural surplus. In antiquity and the middle ages, the valley was an important axis of transport and communication between Carthage/Tunis and Hippo Regius (Annaba) and Cirta/Constantine further west, and it contains a dense network of towns and smaller settlements that can be studied in the light of their medieval development. The fertile belt of the Central Medjerda plains extends west to the high mountains of the Feija forest, and to the east, including the major regional centre of Vaga/Béja as well as smaller towns such as Belalis Maior/Henchir el-Faouar and Balta (Bahri Reference Bahri1999, Cambuzat Reference Cambuzat1986). The region therefore has great potential to explore the impact of regime change, mobility and environmental change on urbanism. In this article, our focus is on the sector stretching from the plain of Ghardimaou in the west to the plain of Bou Salem in the east (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A map of the key settlements and transport network in the Central Medjerda Valley. Late antique and medieval sites from the Atlas archéologique de la Tunisie are noted with their gazetteer number (J.A. Dufton).

Climate and landscape

The cities of Chimtou, Bulla Regia, and Bordj Hellal are located at the edge of the Central Medjerda Valley, a tectonic depression that is bounded by the Kroumir Mountains to the north and the Dorsal Mountains in the south. The climate corresponds to the Mediterranean subtropics with hot and dry summers and rainy winters, though there are significantly annual variations. The Oued Medjerda is a dynamic and significantly meandering watercourse that has shifted considerably over time (Zielhofer and Faust Reference Zielhofer, Faust, Howard, Macklin and Passmore2003, 206–14). The principal settlements of Chimtou, Bulla Regia and Bordj Hellal are all located at an altitude of around 170 masl which offered a certain protection against floods. Medjerda sedimentation rates are sensitive to wider North Atlantic climate behaviour and the North Atlantic cooling that occurred from 4.7 ka onward is reproduced in the local sedimentation profile (Faust et al. Reference Faust, Zielhofer, Escudero and Diaz del Olmo2004, 1772–73; Faust and Wolf Reference Faust and Wolf2017, 62–63). Sedimentation patterns are characterized by periodic flooding events coming from the Oued Medjerda and its tributaries; in contrast, the slopes of the mountains are strongly affected by erosion processes. In the Roman period these sediments show landscape stability, indicated by soil formation and the incision of the Medjerda River. During late antiquity, however, sedimentation rates show evidence of extreme flooding and active morphodynamics were a predominant factor (Zielhofer and Faust Reference Zielhofer, Faust, Howard, Macklin and Passmore2003, 213–14).

Settlement history

The Central Medjerda Valley falls at the intersection of important routes from north–south and east–west and was subject to extensive activity from at least the early first millennium BC. At Chimtou, evidence of settlement dates back to the eighth century BC (von Rummel et al. Reference von Rummel, Stevens and Conant2016, 101). The town became an oppidum civium Romanorum on the creation of the Roman province of Africa Nova in 46 BC (Pliny, Natural History, 5.4.29). Whether these towns functioned as a formal designation of colonization or simply places where many Roman citizens had immigrated is debated (Aounallah Reference Aounallah2010, 45–47; Shaw Reference Shaw1981, 451). Chimtou was elevated to colonia Iulia Augusta Numidica Simitthus under Augustus (CIL VIII, 1261, 22197). This was accompanied by an influx of Roman colonists, urban expansion, and large-scale quarrying of Numidian marble (Ardeleanu et al. Reference Ardeleanu, Chaouali, Eck and von Rummel2019). Previous excavations at Chimtou have centred on the Roman city and the quarry camp. Medieval ceramics and settlement have been identified in various areas of the site, but it remains unclear whether the site was continuously occupied (von Rummel and Möller Reference von Rummel, Möller, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019).

Bulla Regia follows a similar trajectory. It was established no later than the fourth century BC according to ceramic evidence (Ardeleanu Reference Ardeleanu2021, 75–93, 435), but may well have been settled far earlier. From 152 BC onwards, the site was one of five towns marked by their royal status. Orosius (Historia adversus Paganos, 5.21.14) notes the return of the Numidian king Hiarbas to Bulla before his capture and execution by Pompey in 81 BC. Bulla became an oppidum liberum at the creation of Africa Nova in 46 BC (Pliny, Natural History, 5.2.22). The town was elevated to municipium under Vespasian, and to colonia under Hadrian; these promotions were connected to Bulla's wealth, as evidenced by the number of senators and equestrians it provided to Rome during this period (Thébert Reference Thébert1973). Bulla Regia continued to be occupied until at least the fourteenth century (Broise and Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993; Thébert Reference Thébert1983).

Far less is known about other settlements in the region. A third important town, the site of Bordj Hellal also has a pre-Roman phase, attested by black-glazed ceramics visible in the spoil of recent clandestine excavations as well as three large stelae with Libyan inscriptions on display today in the museum of Chimtou (Ghaki Reference Ghaki1997). The site may be Roman Thunusuda, though this remains debated. Thunusuda is mentioned in milestones at Sidi Acem, 3 km east of Chimtou (CIL VIII, 22193, dated AD 350–53), and Sidi Meskin found 7 km from the first milestone and 7 km south of Chimtou (CIL VIII, 22194, dated AD 360–63). If the identification of Bordj Hellal as Thunusuda is correct, the settlement was once again recorded as an oppidum civium Romanorum (Pliny, Natural History, 5.4.29), signalling at least some early Roman presence at a pre-Roman settlement, and was promoted to colonia by the fourth century AD (Desanges et al. Reference Desanges, Duval, Lepelley and Saint-Amans2010, 263). Bordj Hellal was fortified under Justinian in the sixth century (Carton Reference Carton1891, 214–19; Durliat Reference Durliat1981, inscriptions 1 and 2; Pringle Reference Pringle1981, 185–87) and medieval glazed ceramics and a possible mosque suggest it was an important medieval centre. The city of Thuburnica (Henchir Sidi Ali ben Gassem) shares a similar history, including a pre-Roman origin and an early mention as oppidum civium Romanorum (Pliny, Natural History, 5.4.29). The town saw the settlement of veteran colonists in the first century BC, first under Marius and again under Caesar (Quoniam Reference Quoniam1950; Ardeleanu Reference Ardeleanu2021, 10, 26 f., 45, 47). Thuburnica was also fortified at an unknown later date; its walls reuse early Roman tombstones and bases (Carton and Chenel Reference Carton and Chenel1891, 164–66 with Byzantine date and Pringle Reference Pringle1981, 402 with fourth-century date). Its later history is unknown and the site today is inaccessible due to a military installation there.

The region was also occupied by smaller settlements and farmsteads with presses, cisterns and wells, many of which were recorded by Carton (Reference Carton1891). Most are no longer visible; however, epigraphic evidence confirms his picture of a productive rural landscape closely linked to the towns. Inscriptions from Bulla Regia suggest that some early Roman rural landowners are identifiable with the town's elite (Antit et al. Reference Antit, Broise and Thébert1983; Thébert Reference Thébert1992). A comparable situation is evident at Chimtou, where some prominent families of the town are also attested in inscriptions from surrounding small farmsteads (and possible villae-settlements) (Quoniam Reference Quoniam1953; Ardeleanu Reference Ardeleanu2021, 49). A large imperial estate, the Saltus Philomusianus, was located roughly equidistant between Bulla Regia and Chimtou (CIL VIII, 14603; Khanoussi Reference Khanoussi1997). Faouzi Ghozzi's (Reference Ghozzi2006) recent survey of the area to the east and north of Bou Salem, immediately outside our area of interest, confirms the vibrancy of rural settlement into the medieval period. He identified late antique and medieval ceramic evidence at several sites, including agricultural sites with olive presses, a rural church, ‘Byzantine’ fortifications and glazed ceramics of Aghlabid and Hafsid date. The geographer Al-Bakrī mentions ‘Fahs Boll’ (the plain of Boll) as amongst the best wheat-producing regions of all Ifriqiya (Al-Bakrī 1913, 54–137, 115–16, 139), and some scholars have suggested this toponym refers to the territory of Bulla Regia (Cambuzat Reference Cambuzat1986), though this remains contested (M'Charek Reference M'Charek1999). Certainly, although our sector of the Medjerda is largely overlooked by medieval geographies, the fertility and agricultural prosperity of the broader region and its regional capital of Béja is well-attested (Bahri Reference Bahri1999; Al-Bakrī, 1913, 120). The overall perception of the Central Medjerda is therefore one of extensive settlement activity, including several towns and numerous smaller rural sites in late antiquity and the early middle ages.

Comparing urban change in late antiquity and the middle ages

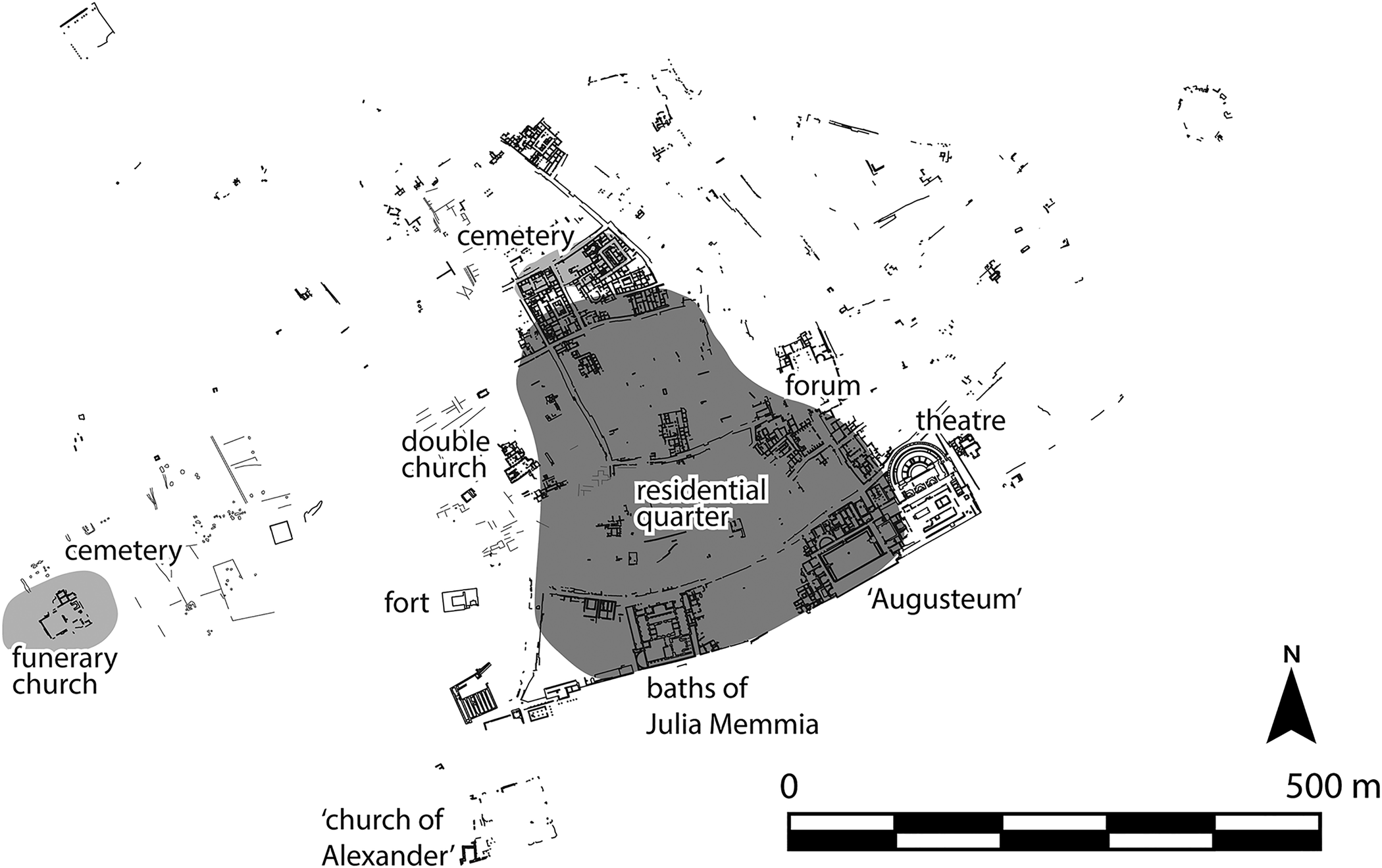

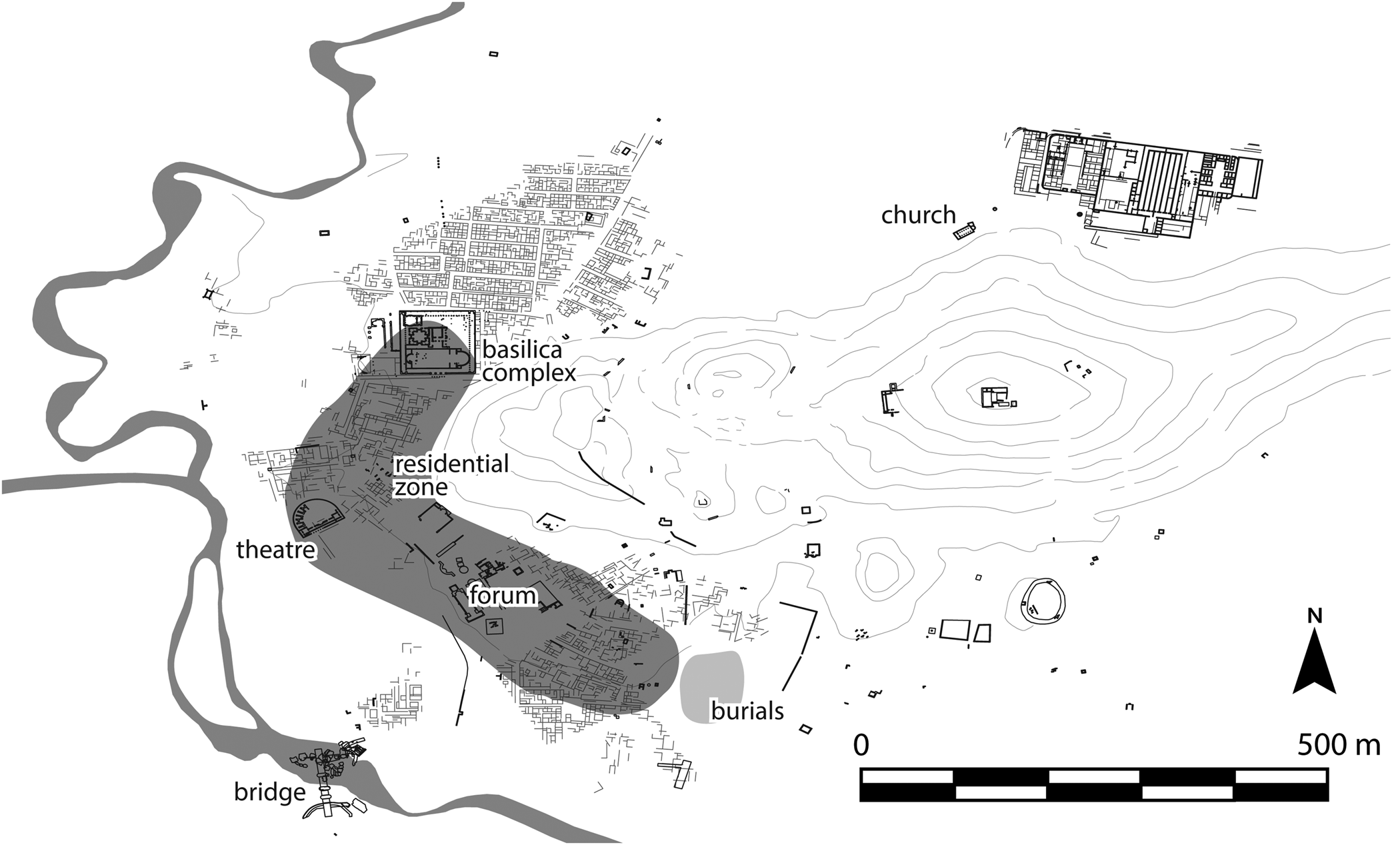

The towns of the region shared important pre-Roman and Roman characteristics, indicative of an evolving micro-regional urbanism across the Central Medjerda Valley (Scheding Reference Scheding2019a; Ardeleanu Reference Ardeleanu2021, 435–39). Urban trajectories in the late antique and early medieval period are much more ambiguous due to a traditional research focus on the Numidian and Roman phases. Our knowledge of Bulla Regia owes much to the work of Yvon Thébert, who challenged the conventional narrative of urban collapse and sporadic squatter occupation in huts (‘gourbisation’) for North Africa based on his work at the site (Figure 2). Thébert's sondages in the baths of Julia Memmia and elsewhere provide some of our best evidence for continuous occupation at the site (Broise and Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993, 95–148); sadly, neither the ceramics nor the full results of these excavations from the 1970s and 1980s have yet been published. Our knowledge of the late development of Chimtou is based primarily on the re-analysis and excavation of two areas, initially opened in the late 1970s and 1980s by Friedrich Rakob and Christoph B. Rüger (Figure 3). The first is a residential area north-east of the forum where a deep sondage, over 8 m in depth, revealed successive layers of occupation from the first millennium BC to the medieval period, while the second area centres on a temple in the north-west of the city occupied into the medieval period (Khanoussi and von Rummel Reference Khanoussi and von Rummel2012, 184–92; von Rummel and Möller Reference von Rummel, Möller, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019, 178–95). In contrast, both Bordj Hellal and Thuburnica are only cursorily documented. However, the extant fortifications at both provide a tantalizing suggestion of medieval occupation at these sites too.

Figure 2. Plan of Bulla Regia showing late antique and early medieval activity and key buildings mentioned in the text (J.A. Dufton).

Figure 3. Plan of Chimtou showing late antique and early medieval activity and key buildings mentioned in the text (J.A. Dufton).

These disparate fieldwork histories make it difficult to assess whether urbanism in the region continued along a similar trajectory, or if the fate of each city diverged significantly. This includes the extent to which settlements contracted or were abandoned in the medieval period, or not, when parts of each city may have been fortified or abandoned, and how local and regional networks of production and distribution have changed through this period. The following text provides a thematic consideration of different types of investment (public, religious, and residential) and draws out new parallels between the sites in the Central Medjerda in this challenging period.

Public investment

There is considerable evidence for public investment and an active municipal life in the fourth and fifth centuries. Our best confirmation comes from Bulla Regia, where there was significant spending on civic monuments in the fourth century as well as repurposing of spaces and buildings. The forum was of particular focus and continued to be the centre of public display. The civic basilica on the forum's eastern flank was repaved in the fourth century (Quoniam Reference Quoniam1952, 460–72) and two inscriptions found in the sanctuary of Apollo describe the restoration of aedes publicas between 286–305 (CIL VIII, 25520) and the restoration of a tabularium by a proconsul in 361 (CIL VIII, 25521). During the fourth century, the temple of Apollo was used as a sort of collecting place, where many honorific bases and statues were transferred or newly erected (e.g. CIL VIII, 25528, fourth century; CIL VIII, 25524, dated AD 330–40; CIL VIII, 25525, dated AD 326–32; see also Quoniam Reference Quoniam1952, 466) and attest to the continuous functioning of the ordo decurionum in the town (Beschaouch et al. Reference Beschaouch, Hanoune and Thébert1977, 83–88). Other refurbishments of public structures and displays also took place in the fourth century. The orchestra of the theatre was repaved (Quoniam Reference Quoniam1952, 460–72), and a new portico was added to the enormous esplanade in the south–west of the town (Broise and Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993, 169 f). Fourth-century emperors and proconsuls were still honoured by statues, including Helena, mother of Constantine (Cherbonneaux Reference Cherbonneaux1952), two bases for Constantine II and Gratian from the forum area (AE 1953, 85, dated AD 337–40; AE 1953, 87, dated AD 367–83), a base for Constantine II found 6 km from Jendouba (AE 1949, 26, dated AD 317–37), and bases from the baths of Julia Memmia and other contexts (ILAfr 456, dated AD 324–37; AE 2002, 1676, dated AD 339–40). A statue base dedicated to Constantius Chlorus (AD 293–305) was found near the theatre, possibly pointing to a continuous public use of the esplanade (Ksouri Reference Ksouri2012, II, 221–22).

At some point in the long late antiquity, many of the temples and arches were dismantled. In the forum, at least one temple (the possible Capitolium?) was razed to its podium and an arch was removed. Another arch west of the south–western esplanade (Broise and Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993) and the two twin temples on the same plaza were destroyed and their staircases replaced by a late paving (Beschaouch et al. Reference Beschaouch, Hanoune and Thébert1977, 23). The eastern temple's podium was reused as a press, similar to the reuse of the Capitolium in Thuburbo Maius (Leone Reference Leone2007, 230). To the south–west of the theatre, on esplanade A, two temples (C′ and D) were completely razed to the ground, while temples A, B, C″ and E as well as the temple of Isis, saw dismantling down to their podia (Ksouri Reference Ksouri2012; Ardeleanu Reference Ardeleanu2021, 169–84). The date of these destructions is not clear, but it is tempting to connect them to the closing of pagan temples in the late fourth to fifth centuries. Their partial reuse might be even later.

New investment in bath structures also took place in this period. A bath was installed in the north-eastern corner of the so-called Augusteum and the central western room was repaved (partially with spolia) in the later third or fourth century (Hanoune Reference Hanoune1991, 367; Reference Hanoune1993, 483; Reference Hanoune, Morlier, Bailly, Janneteau and Tahri2005). The baths of Julia Memmia (Broise and Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993, 385; Thébert Reference Thébert2003, 134), the baths to the west of the theatre (Beschaouch et al. Reference Beschaouch, Hanoune and Thébert1977, 73; Thébert Reference Thébert2003, 134), and the theatre itself all continued to be used for their original function until at least the end of the fifth century. However, early reports suggest that parts of the baths of Julia Memmia were already used for storage and habitation during the fifth century (Carton Reference Carton1909, 583). Héron de Villefosse (Reference Héron de Villefosse1914, 476) mentions many late Roman amphorae with tituli picti, one lead reliquary with a cross and three belt buckles of Vandalic date in one room of the baths.

At Chimtou, a series of epitaphs and an inscription for the restoration of the theatre in AD 376/377 (CIL VIII, 25632) indicate that the city had a lively urbanity at the end of the fourth century/beginning of the fifth century. The same is shown by a technically sophisticated late antique turbine mill built in the ruins of the Trajanic bridge over the Medjerda river (Röder and Röder Reference Röder, Röder and Rakob1993, 95–102; Hess et al. Reference Hess, Müller and Khanoussi2017, 63–67) and activities in the marble quarry until at least the fourth century (CIL VIII, 14600). An early fifth-century hoard of 1647 gold solidi in the east of the city, uncovered during the construction of the museum (Baldus and Khanoussi Reference Baldus and Khanoussi2014), confirms that enormous wealth was present, even though the hiding and especially the non-retrieval of the hoard may reflect crisis. The wealth of the town is further attested by the construction of a monumental new Christian complex of a basilica and baptistery in the fourth or early fifth century. This was built over a large temple, probably for the imperial cult, which preserved parts of the former temple podium and two accessible vaulted rooms. Together with the scale of construction, this suggests some kind of state involvement (see discussion below).

From the sixth century, the public monuments underwent diverse types of transformation. At Bulla Regia, the baths of Julia Memmia were given over to habitation and industry in the sixth or early seventh century (Thébert Reference Thébert2003). The so-called Augusteum was also repurposed at some point in late antiquity: the large basilica was abandoned, the baths collapsed and were partly reused for presses, and signs of habitation and several late tombs were uncovered in the north-western corner of esplanade B (Hanoune Reference Hanoune1990, 500; Reference Hanoune1993, 483, 486, fig. 38). Perhaps in the same period, though the dating is inconclusive, parts of the city were fortified. Defensive walls are still visible at the theatre in the south–east (Figure 4) and fully blocked bays further secured this building (Beschaouch et al. Reference Beschaouch, Hanoune and Thébert1977, 100; Pringle Reference Pringle1981, II, 500; Ksouri Reference Ksouri2012, I, 138, fig. 112). The southern façade of the town, which acted as a wide esplanade in the early Roman period (Broise and Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993, 372–77; Scheding Reference Scheding, de Ligt and Bintliff2019b, 359–60), may also have been reinforced in some manner: the doors and openings in many of the buildings lining the frontage were blocked at some point and there are also indications of later rebuilding. The existing wall and natural change of elevation would have made this a pragmatic solution. In the south–west of the site, a substantial fortification wall of spoliated ashlar blocks with a narrow postern entrance blocked the wide, paved street running north–south alongside the massive, unexcavated south–western baths. Its construction is contemporary with the so-called sixth-century Church of Alexander, which filled the south–west corner. The enceinte continues to the east and seems to englobe the entirety of the south–western baths (as in Tissot Reference Tissot1881, pl. V). It is tempting to see this also as a Byzantine fortification, similar to the fortification of the baths at Mactar (Leone Reference Leone2007, 262). Finally, a small fortified blockhouse was built at some point on the west end of the primary east–west street (Pringle Reference Pringle1981, II, 500; Saladin Reference Saladin1892, 430). It is unclear at this point what relation these fortifications have, if any, to the town enceinte with towers depicted on early plans (e.g. Carton Reference Carton1890, fig. 1; Winkler Reference Winkler1895, pl. XIV). For many years, this wall was thought to be a phantom; however, traces of it (in two construction techniques) were identified on the north and east of the site in the 1970s (Antit et al. Reference Antit, Broise and Thébert1983, 137–41).

Figure 4. Fortification of the theatre at Bulla Regia (J.A. Dufton).

A comparable fate befell the public buildings at Chimtou. As we have seen already, a systematic dismantling of a temple took place in the late fourth or early fifth century to build a monumental new church complex. Many other public buildings were also systematically dismantled at some point in late antiquity, probably from the sixth century or later, to reuse the materials elsewhere. This is most clearly visible in the case of an honorific arch and nymphaeum in the forum which were dismantled down to their foundations, while a temple on the plaza's southern end was razed to its podium (Ardeleanu Reference Ardeleanu2021, 427–28). A sixth-century lime kiln found north-east of the forum gives insight and a secure chronology for the dismantling process in this zone. Marble architectural elements, sculpture and inscriptions were found within the kiln, ready to be transformed into lime (von Rummel and Möller Reference von Rummel, Möller, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019, 191). The kiln was in the northern apse of a probable civic building which had been almost entirely dismantled and given over to industrial activity; another smaller kiln of unclear purpose with pisé walls was installed 2 m to the south-west in a room opening to the forum. The conversion of the sanctuary of Saturn on the Djebel Bou R'Fifa (itself a conversion of the pre-Roman victory monument) into a small Christian church also dates to this period (Rakob Reference Rakob1994, 1–38, part. 36–38). A similar methodical deconstruction occurred at the theatre, the amphitheatre, an arch in the north of the city, the temples for Caelestis and the Dii Mauri and the monumental arch leading to the northern temple of the former imperial cult. The scale of dismantling in Chimtou is impressive, though its chronology and the fate of the stone and lime remains unclear.

Large-scale dismantling of public buildings is frequently associated with the construction of Byzantine fortifications, and yet there is no evidence of a state-mandated Byzantine fortification at Chimtou. For this reason, earlier research has assumed a comparatively early decline of the city, related to the abandonment of the quarry at the beginning in the fifth century (Baldus and Khanoussi Reference Baldus and Khanoussi2014, 9–10). However, a substantial late antique wall of spoliated material running along the southern, western and northern flank of the so-called city hill may relate to quarrying activity rather than fortification (for the wall see Röder Reference Röder and Rakob1993, 21, 42). It is, however, possible that some of the monuments of Chimtou were stripped and transported to the neighbouring site of Bordj Hellal, where a large sixth-century enceinte of 7.25 ha was constructed to protect the settlement (Figure 5). Two inscriptions (one in Latin, one bilingual Greek/Latin) commemorate the construction of the walls, which were erected under the orders of Solomon, most likely as part of a significant fortification programme during his second prefecture in 539–42 (Durliat Reference Durliat1981; Pringle Reference Pringle1981, 185–87; Toutain Reference Toutain1893, 470; Figure 6). The walls were built in the standard construction technique of Byzantine fortifications and consist of a rubble core faced with ashlar blocks, which included reused architectural elements, columns and funerary inscriptions. Roughly pentagonal, the fortification had fifteen towers and perhaps a gate flanked by towers on the south–eastern side (Carton Reference Carton1891, 216–18). Denys Pringle (Reference Pringle1981, 185) suggests that the exposed nature of the site at Chimtou presented challenges for fortification; coupled with the decline of the marble trade, this may have favoured a shift of settlement to the more strategic, easily defended location of Bordj Hellal.

Figure 5. Plan of the fortifications at Bordj Hellal (H. Indgjerd).

Figure 6. Fragmentary inscription commemorating the fortification of Bordj Hellal (J.A. Dufton).

It is striking that the main access routes and street grids continued to be largely respected. At Bulla Regia, the important east–west axis was kept clear as were other streets, though there is evidence of partial encroachments by houses and shops in some zones, suggesting a narrowing of streets. Other streets may have been blocked entirely in the medieval period, as in the case of the street near the baths of Julia Memmia which was blocked by habitations, silos and workshops. At Chimtou, the encroachment onto public spaces and streets by arguably late antique or early medieval burials also underlines the shifting perception of public areas. The east–west roadway was maintained (as evidenced by late milestones); however, the bridge on the road connecting Chimtou to Sicca Veneria (El Kef) was destroyed by flooding at some point before the fifth century – if the mill in the ruins of the bridge is indeed of Vandalic date. Streets in the forum area, at the north temple and between the museum and dig house were probably affected by expanding houses and subsequently by burials and medieval structures. For example, two groups of simple cist tombs (all for inhumations, amongst them also child burials) are still visible today on the street between the museum and the dig house, as well as in the road running south of the monumental arch and staircase of the former sanctuary of the imperial cult (Figure 7). Similar burials are known from many other sites of late antique and early medieval North Africa, such as Carthage (Leone Reference Leone2007) or Hippo Regius (Ardeleanu Reference Ardeleanu2019).

Figure 7. Undated burials and houses inserted into an existing thoroughfare at Chimtou (P. von Rummel).

At both sites, the political centres (fora and esplanades) were maintained and restored in the fourth and probably the fifth century. Their partial destruction and abandonment during the late fifth and sixth century was mitigated by the creation of new foci – especially religious complexes and fortifications – at different locations within the cityscapes.

Religious investment

The region had a substantial Christian population by the late fourth century. Bulla Regia has the earliest evidence of Christianity with a bishop attested as early as 256 (Sent. Episc. 61), whereas bishops are first attested at Chimtou, Thunusuda and Thuburnica at the Council of Carthage in 411. The inhabitants of Bulla Regia were famously rebuked by Augustine just before Easter in 399 for attending the theatre and holding lavish spectacles too frequently. According to Augustine, the people of Bulla should have imitated the citizens of neighbouring Chimtou where nobody entered the theatre (Sermons 301A 9). His comparison of the two cities, as well as the large number of bishops known for Bulla Regia, has led some to interpret Chimtou as a smaller and less important city (Markus Reference Markus1990, 116; Rebillard Reference Rebillard and Vessey2012, 52). Whether we can detect a difference in the treatment of public spectacle buildings, as suggested in Augustine's sermon, remains an interesting question, one that is complicated considerably by the remains of the churches identified at Bulla Regia and Chimtou.

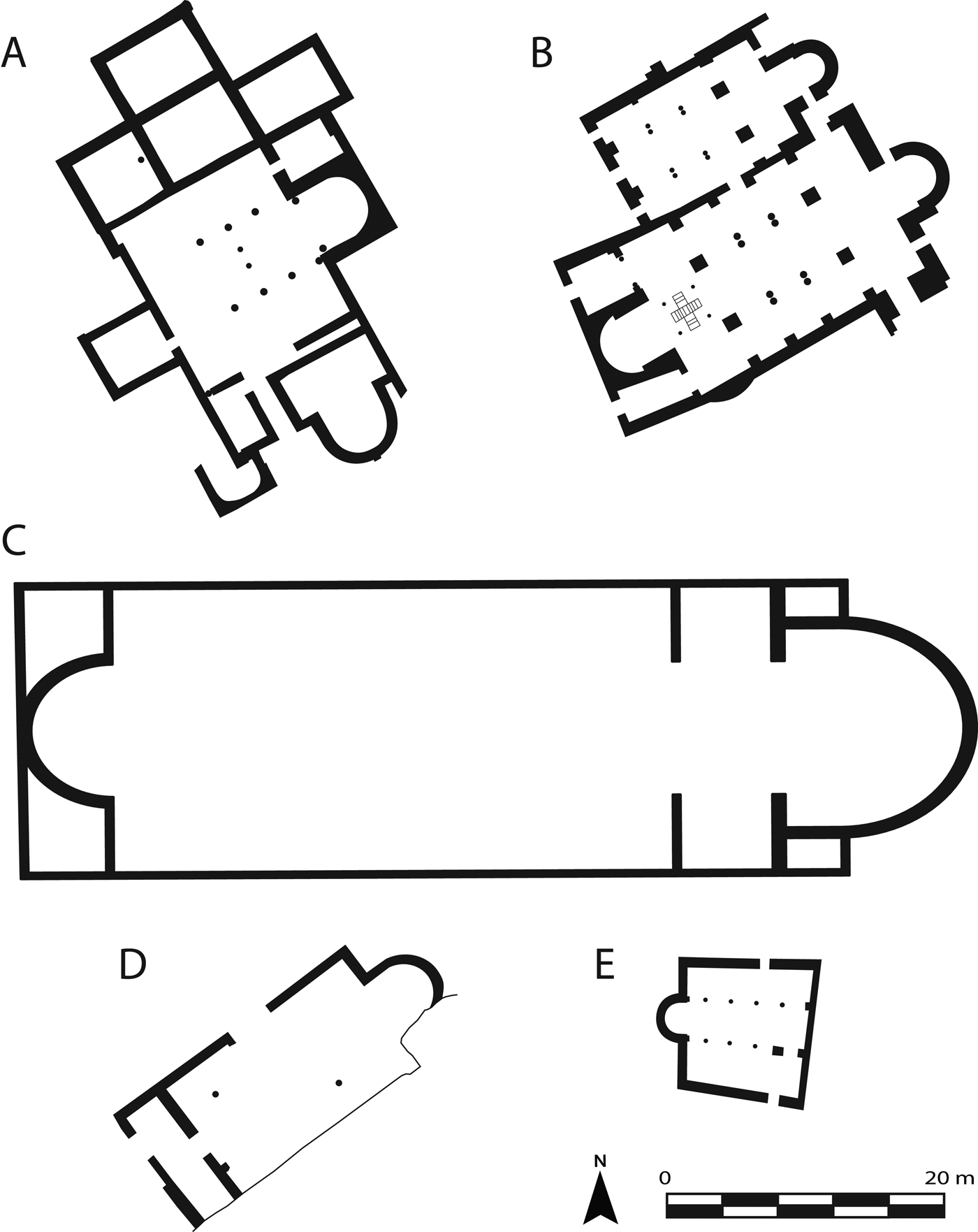

Multiple churches built in the fourth–fifth centuries have been excavated at Bulla Regia (Figure 8). The earliest of these was likely a funerary church erected on the western edge of the pagan cemetery, possibly over an earlier mausoleum (Chaouali et al. Reference Chaouali, Fenwick and Booms2018; see Figure 8A). This complex contains the church itself, a series of funerary chapels, a walled funerary enclosure, and an extensive cemetery with over 300 recorded burials, including two bishops, Armonius and Procesius (Chaouali Reference Chaouali, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019). The church has three naves with a semi-circular apse and the mosaic tomb coverings stylistically suggest a construction date of the mid-fourth to fifth century. A possible episcopal complex consisting of two churches (Basilica 1 and 2) in the west of the city also most probably dates to around this period (Duval Reference Duval1969, Reference Duval1971, 41–51; see Figure 8B). Another possible (and disputed) church was identified in 1922 to the north of the nymphaeum in the north-east baths: excavations, now backfilled, revealed a presbyterium, a ciborium, and three naves separated by colonnades, the central of which was paved in mosaics with a funerary area outside (Carton Reference Carton1922, 332–33; Beschaouch et al. Reference Beschaouch, Hanoune and Thébert1977, 79). Further evidence for the Christian population in the fourth and fifth centuries comes from a mosaic decorated with the four rivers of Paradise and a biblical inscription (Genesis 28, 17) in House 10, probably dating to the fifth century (Hanoune Reference Hanoune1983).

Figure 8. Composite plan of churches at Bulla Regia and Chimtou (J.A. Dufton). (A) Funerary church at Bulla Regia (after Chaouali et al. Reference Chaouali, Fenwick and Booms2018). (B) Double basilica complex at Bulla Regia (after Baratte et al. Reference Baratte, Bejaoui, Duval, Berraho, Gui and Jacquest2014, f. 16–6). (C) Large basilica at Chimtou constructed on earlier temple. (D) Church at Chimtou overlooking the labour camp (after Baratte et al. Reference Baratte, Bejaoui, Duval, Berraho, Gui and Jacquest2014, f. 13–5). (E) Small church at Chimtou installed atop the earlier Temple of Saturn (after Baratte et al. Reference Baratte, Bejaoui, Duval, Berraho, Gui and Jacquest2014, f. 15–5).

At Chimtou, an enormous Christian complex (Church 3) was erected in the late fourth or early fifth century on the location of (and built using the blocks from) an earlier pagan temple and walled enclosure (von Rummel and Möller Reference von Rummel, Möller, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019, 193–95; Figure 9). The first phase of construction was probably contemporary to the dismantling of the temple and included a basilica, a quadrilobal building which probably served as a baptistery, a monumental building with niches which was probably a mausoleum, and a new building of unknown function built over the razed podium of the temple. Two contemporary furnaces for iron smelting presumably made iron nails or other materials required for the major rebuilding and construction works. A reused console with Christogram and alpha/omega found 50 m further east of the civic basilica in the forum (Saladin Reference Saladin1892, fig. 31) might indicate a religious transformation of some building(s) in the forum area. However, there is currently no evidence for the transformation of the forum basilica or the possible macellum situated north of the forum into a church (see Béjaoui Reference Béjaoui1989, 1932–37).

Figure 9. Plan of the late-fourth or early-fifth century Christian complex at Chimtou (S. Arnold).

There is significant evidence of new churches being built, remodelled or expanded in the sixth century after the Byzantine reconquest of Africa – a particularly interesting development given the Justinianic fortification of Bordj Hellal as well as the Byzantine episcopal investment in this region that Anna Leone (Reference Leone2011) has identified. The second phase of the two-basilica episcopal complex at Bulla Regia is dated to the sixth century on the stylistic basis of its mosaics (Duval Reference Duval1969, 226–34). This transformation inverted the structure, with the construction of a new apse with synthronos to the north-east. The original altar was replaced with a cruciform baptismal font, new mosaics laid, and two cupolas added over each apse. It is presumably also in this period that the second smaller church on the same plan was built; the mosaics are in a similar style (Duval Reference Duval1969). At the same time, the funerary church was repaved in stone covering and closing off the interior of the church for burial (Chaouali et al. Reference Chaouali, Fenwick and Booms2018). The so-called ‘Church of Alexander’ at Bulla Regia also dates to the sixth or seventh century. This enigmatic building was first recorded by Carton (Reference Carton1915b), who noted a door lintel inscribed with Psalm 120 (line 8) and a variety of finds, including a Byzantine cross dedicated by the priest Alexander and a reliquary. However, the religious function of this building has been much debated.

At Chimtou there is similar evidence for restructuring of existing buildings and new church construction in the Byzantine period. A second phase of remodelling in Church 3 is dated to the sixth century based on the style of its mosaics. The construction of two small churches at Chimtou is also dated to the Byzantine period on mosaic style. The first was a small, well-preserved building cut into the lower slope of Jebel Bou R'Fifa, situated to the west of the labour camp (Church 1; see Figure 8D). The structure included a three-naved basilica oriented east–west, with an eastern apse, mosaics in the quadratum populi, and a front porch (Béjaoui Reference Béjaoui1989, 1932; Rakob Reference Rakob1994, pl. 10D). Its location within or next to an earlier cemetery suggests a funerary function, supported by two burials cut into the floor (Béjaoui Reference Béjaoui1989, 1935). On the summit of Jebel Bou R'fifa, a small, trapezoidal church was installed in the heart of the temple of Saturn, itself a replacement of the Numidian monument (Church 2; see Fig. 8E). This structure had a western apse and three naves with a central altar, and was again paved with mosaics (Rakob Reference Rakob1994, 37, fig. 5, 15, 16).

The fate of the Christian communities in the Central Medjerda in the early medieval period and the impact of the spread of Islam remains uncertain. The last mention of a bishop at Chimtou occurs in 646 (Maier Reference Maier1973, 201), as is also the case at Thuburnica (Maier Reference Maier1973, 219). At least two of the churches came to an end in the seventh century or later. At Chimtou, the large basilica was abandoned in the second half of the seventh century and subsequently collapsed, as is apparent from a massive layer of debris containing large quantities of interlocking tubes from the vaults of the church. At Bulla Regia, both the Church of Alexander and the outlying funerary church were destroyed by fire in the late seventh century or later; in the latter a funerary chapel was used for storing broken columns (Chaouali et al. Reference Chaouali, Fenwick and Booms2018). In contrast, a possible bishop of the eighth century (Mesnage Reference Mesnage1912, 50) and a series of later tombs cut through the mosaic floor of the two-basilica episcopal complex at Bulla Regia also indicate that Basilica 1 continued to be used for burial into at least the eighth century; one of these tombs, a child burial contained Umayyad copper coins (Duval Reference Duval1969, 229). As yet, no mosques have been identified at either site, and the ruins of a possible mosque in the centre of the fortifications of Bordj Hellal have yet to be documented and dated.

We can therefore see similar patterns in religious building activity. At both Bulla Regia and Chimtou, all known pagan temples were dismantled or transformed during the long late antiquity. Churches were installed initially at least on the peripheries of towns, rather than within the earlier civic foci. The extensive restoration and extension of churches in the sixth century suggests a degree of investment following the Byzantine conquest and demonstrates the persistent power of Christian communities in this region which continued into the early medieval period.

Residential investment

Together with investment in public and religious architecture, the fourth and fifth centuries saw considerable elite investment in private property across North Africa, particularly the addition of large reception rooms or semi-private baths that held an important communal function for urban populations (Thébert Reference Thébert, Duby and Ariès1985; Ellis Reference Ellis1988; Bullo and Ghedini Reference Bullo and Ghedini2003; Leone Reference Leone2007, 51–60). The best evidence we have for these transformations comes from Bulla Regia, where a long history of excavation has focused on the unique subterranean housing and over twenty houses of varying sizes have been excavated (Beschaouch et al. Reference Beschaouch, Hanoune and Thébert1977; Thébert Reference Thébert1972; Hanoune Reference Hanoune1980; Bullo and Ghedini Reference Bullo and Ghedini2003, 33–72). Ascertaining the precise chronology of residential investment is problematic and based primarily on stylistic dating of mosaics and architectural characteristics. Nonetheless, taken collectively there is clear evidence for ongoing elite investment until at least the late fourth or early fifth century. For example, the Maison de la Chasse was first constructed in the early third century through the combination of two earlier lots within a single insula (Thébert Reference Thébert1972, 41; Bullo and Ghedini Reference Bullo and Ghedini2003, 51); roughly contemporary developments at the two properties of the Maison No. 1 (Hanoune Reference Hanoune1980, 5–7; Bullo and Ghedini Reference Bullo and Ghedini2003, 55–57) and the Maison du Paon (Hanoune Reference Hanoune1980, 76; Bullo and Ghedini Reference Bullo and Ghedini2003, 54) imply a period of elite regeneration of the wider neighbourhood beginning in the third century (see Dufton Reference Dufton2019). From the fourth century the Maison de la Chasse was expanded again, in this case purchasing a third lot and inserting a distinctive apsidal reception hall (Thébert Reference Thébert1972, 40–41; Reference Thébert1983, 103; Bullo and Ghedini Reference Bullo and Ghedini2003, 51). Further phases of development at this property in the fourth century added a small bath complex and latrine, accessible from the western street frontage (Thébert Reference Thébert1972, 40–41; Reference Thébert, Duby and Ariès1985, 330). A similar pattern of expansion and refurbishment also featured heavily at other houses at Bulla, such as the enlargement of the peristyle at the Maison No. 3 (Thébert Reference Thébert1972, 44; Hanoune Reference Hanoune1980, 47; Bullo and Ghedini Reference Bullo and Ghedini2003, 66), the addition of new mosaics in the Maison de la Nouvelle Chasse in the fifth century, or the merging of two earlier properties into the Maison No. 7 (Hanoune Reference Hanoune1980, 55–58; Bullo and Ghedini Reference Bullo and Ghedini2003, 62), amongst other examples (see also Leone Reference Leone2007, 61). The quick infilling of a bathhouse built into the street at the Maison de la Chasse further shows the continued maintenance of civic infrastructure and the upholding of property laws by the local authorities (Thébert Reference Thébert, Duby and Ariès1985, 331).

A similar pattern might reasonably also be expected at the sites of Chimtou and Bordj Hellal, but a lack of excavation in residential neighbourhoods makes it more challenging to identify. At Chimtou, only some descriptive observations of early explorers were dedicated to the town's houses (Saladin Reference Saladin1892, 398–400). However, geophysical survey has revealed insulae in the north of the site and to the west of the museum. Some presumably had a late antique or medieval phase, and the presence of economic activities in both areas is indicated by anomalies pointing to large kilns. The road running south–north between the museum and the dig house was not only used for burial (see above), but was encroached upon by housing. Though excavations of the later 1980s and 1990s are undocumented, two rooms of a house with caementicium walls and possibly late antique mosaics expand over the street's pavement (Figure 7). The early fifth century hoard was found in the same area (see above) suggesting a degree of elite wealth and residential investment in this area of Chimtou in this period. Two or three other rooms on the same street consist of spoliated material (shafts, pillars, blocks) built in very rudimentary fashion, suggesting the area continued to be occupied into late periods.

From the sixth century, the evidence for residential life becomes more fragmentary at Bulla Regia due to the removal of later stratigraphy in early excavations. The most notable transformation occurred in the north-west residential area. Occupation at the Maison de la Chasse and the Maison de la Nouvelle Chasse continued into the sixth century; at some point after this date, however, the triclinium of the smaller Maison de la Nouvelle Chasse was reused for burial (Beschaouch et al. Reference Beschaouch, Hanoune and Thébert1977, 64 f.; Thébert Reference Thébert1983, 114). Further burials across the street at the Maison No. 1, Maison No. 9, and Maison No. 10 indicate that this neighbourhood became a sort of cemetery (Broise and Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993, 387; Hanoune Reference Hanoune1980, 5; Thébert Reference Thébert1983, 113–14; see also Leone Reference Leone2007, 242–43). Scattered evidence from elsewhere similarly points to a contraction of the elite, subterranean housing. For example, a mid-seventh century hoard of seventy Byzantine gold coins recorded at the Maison du Trésor was deposited in the lower level of the house, within a plug of earth and stone inserted to block a door into the oecus (Quoniam Reference Quoniam1952, 472). Other houses, such as the Maison d'Amphitrite, may have been continuously used into the medieval period (Carton Reference Carton1911, 9).

Our best evidence for medieval housing comes from in and alongside the baths of Julia Memmia. Over twenty silos were cut into the street between the baths and the eastern of the ‘twin temples’ and must have been associated with nearby residential activity in the baths and on the streets. These contained a wide array of materials, including ceramics of the ninth/ tenth century and perhaps later (Broise and Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993, 163–67). Suggestions of later occupation are also visible at other parts of the site. For example, postholes and silos cut into the eastern side and the southern basilica of the so-called Augusteum suggest these areas were used for habitation, taking advantage of the standing walls of the earlier structure (Hanoune Reference Hanoune1990, 500, fig. 27, with ‘Arabic’ date; Reference Hanoune1992, 562, fig. 32). Traces of medieval activity were also recorded in the (presumably repurposed) caldarium of the small baths in the Maison de la Chasse (Broise and Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993, 395). Walls observed in various excavated sections, such as across the street to the north of the eastern extension to the baths of Julia Memmia and in the eastern side of the trench for a partially excavated peristyle house (Figure 10), are consistent with this pattern of sustained occupation in the core of the settlement. A coin hoard found in the theatre, containing 260 silver dirhams and dating to the second half of the twelfth century (Boulouednine Reference Boulouednine1957), implies occupation at the site continued well into the middle ages.

Figure 10. Probable medieval housing observed in section of excavated areas at Bulla Regia. (A) Across the street from the baths of Julia Memmia. (B) In the trench section of an excavated Roman peristyle (J.A. Dufton).

Chimtou also has extensive evidence for medieval occupation. Medieval structures with storage silos have been excavated in the forum area and to the north of the ancient city, and it seems likely that there was a large, continuous medieval settlement stretching at least from the forum to the basilica complex. Early reports mention late houses on the forum (Toutain Reference Toutain1892a, 339, with unproven Byzantine date) and walls built of spolia in its west and north-west (Toutain Reference Toutain1893, 469), as well as other habitations associated with metal/ceramic production within the orchestra of the theatre (Toutain Reference Toutain1892b, 368; Reference Toutain1893, 468–69). Medieval buildings also covered at least the northern and eastern flanks of the forum (Rakob Reference Rakob and Rakob1993, 3 mentions Fatimid ceramics) and probably also the civic basilica. A pottery kiln was excavated in the early twentieth century in a reused building just north of the civic basilica (Toutain Reference Toutain1893, 467–68), which was also apparently used to store architectural elements. Within this room a hoard of 18 gold coins from AD 954–64 (all from the Al-Mansouriya mint near Kairouan) was found.

In contrast to Bulla Regia, it is unclear whether Chimtou was continuously settled or was abandoned and subsequently reoccupied (von Rummel Reference von Rummel, Stevens and Conant2016). Excavations to the north-east of the forum suggest a rupture in occupation in this zone at least: the zone seems to have been abandoned by the seventh century and covered with a thick layer of erosion deposits onto which new structures were built between the ninth to eleventh centuries. Of these, two medieval domestic rooms have been excavated (Figure 11). The one-storied structures were rectangular, aligned east–west and built of rubble stone and spolia from the ruins of the Roman town with flat roofs made of wood and clay (Figure 12). Some walls still use a rudimentary opus africanum technique, but only with an earthen mortar. Different phases of use were observed within these buildings, often in rapid succession. Floors were partially paved and partially of beaten earth and had associated hearths, hand mills and small dump pits. Outside the structures were a dozen storage silos in the form of deep (up to 4 m), pear-shaped and oval storage pits, similar to silos recorded to the west of the baths of Julia Memmia at Bulla and comparable to storage pits at other Central Tunisian sites (e.g. Ferjaoui and Touihri Reference Ferjaoui and Touihri2003, 92–94; Touihri Reference Touihri, Nef and Arcifa2014, 134–37). Archaeobotanical analysis by R. Neef (DAI) from Silo 4 (dated 1185+−30) and a refuse pit (SE 202, dated 1105+−30 BP) revealed crops (triticum aestivum/durum), fragments of pine, tamarix and olive tree (von Rummel and Möller Reference von Rummel, Möller, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019, n. 30, 33). Because only two rooms (P and D) were excavated fully, it is unclear whether they were isolated structures or part of a medieval courtyard house with silos in the courtyard, a form well-documented elsewhere at Sétif and Zama (Fentress Reference Fentress1987; Ferjaoui and Touihri 2005, 89–94).

Figure 11. Plan of the medieval residential activity around the forum at Chimtou (DAI/INP, Chimtou-Project).

Figure 12. A medieval house at Chimtou to the north-east of the forum (DAI Rome, neg. D-DAI-ROM-RAK-01487).

The different state of research impedes direct comparison between Chimtou and Bulla, but the continuous occupation of wealthy urban residences seems likely at both sites during the fourth and fifth centuries. The influx of industrial/artisanal structures and of burials into residential areas from at least the sixth century onwards is attested (even if unevenly), perhaps suggesting a fragmentation of urban fabrics into smaller neighbourhoods. Traces of domestic activity are harder to spot from the seventh century onward, but they are present. At Bulla Regia the occupation of domestic quarters and the transformation of former civic monuments into habitation/artisanal zones seems more continuous. Chimtou – at least on the basis of current excavations – shows traces of rupture within the late seventh/eighth century before a ninth-century reoccupation. Whether this reflects our inability to accurately date eighth-century material or means that the site, or parts of it, were abandoned for a certain time remains an open question. Even so, the size of excavated houses, the presence of several coin hoards as well as the presence of glazed wares (see below) point to a certain degree of wealth and connectivity within the Central Medjerda Valley in the ninth century and later.

Ceramics and the regional economy

Ceramics offer some insight into the degree to which towns in this region were integrated into regional and inter-regional trade networks in antiquity and the middle ages. Unfortunately, only limited analysis of material culture has taken place thus far, focusing on the ceramics of Chimtou (see von Rummel and Möller Reference von Rummel, Möller, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019 for full details and references). From the third century at the latest, the ceramic repertoire at Chimtou reflects an increasing ‘regionalism’ of the market with a drop-off in the quantity of imported ceramics. The market consists almost exclusively of locally or regionally produced finewares, storage containers and cooking wares, with very few imported items, such as Mid Roman Amphorae 1b (Vegas Reference Vegas and Rakob1994, 168). This pattern has been identified at other inland sites (Bonifay Reference Bonifay, Mattingly, Leitch, Duckworth, Cuénod, Sterry and Cole2017). By the sixth–seventh century, there are typological and technical evolutions (Figure 13). This may reflect the introduction of different cooking or dining practices, as can be seen for example in the use of bigger plates and a new series of cooking vessels. However, new forms continue to coexist with old ones, such as mortars or casseroles, which do not evolve functionally but solely from an aesthetic point of view (see below). They suggest the continuity of earlier dining and cooking traditions, but changing tastes.

Figure 13. A sample of representative ceramics from the late antique and medieval periods at Chimtou and Bulla Regia (DAI/INP, Chimtou-Project and INP/UCL, Bulla Regia Project).

Most African Red Slip tablewares were produced locally or in the hinterland of Chimtou, though a small number of plates (e.g. Hayes 107, 108 and 109, late variations) of ARS D produced in northern Tunisia were imported, as were probably a series of flanged bowls (a variant of Bonifay 32) of unknown production location. Sixth–seventh century mouldmade lamps (Atlante X) and wheelmade African Red Slip ware (‘Type Vandale’) (Bonifay Reference Bonifay, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019, 301–302, fig. 2) were probably also locally or regionally produced. Commonwares (bowls, basins, jugs and large jars) were produced locally/regionally but are similar typologically to those produced at Carthage and elsewhere. A few types, such as the flanged bowls/mortars produced in quantity into late antiquity (Bonifay Reference Bonifay and Lavan2013, 550; Fentress Reference Fentress2021, 163–68), show slight differences in execution compared to coastal regions. Cooking wares were limited to a few specific forms and dominated by handmade ‘Calcitic Ware’ (Peacock Reference Peacock, Fulford and Peacock1984, 11, Fabric 1.3; Polla et al. Reference Polla, De Vos, Ischia, Gialanella and Capelli2007, 603–9) and wheelmade ‘Rouletted Kitchen Ware’ (RKW) (after Andreoli and Polla Reference Andreoli, Polla, Vos Raaijmakers and Maurina2019, 179). A new introduction was the late fifth/early sixth century painted jars, jugs and bowls with geometric, vegetal and occasional zoomorphic decorations, which also goes together with a new light red paste. These were common at inland sites, but also at Carthage and along the Tunisian coast (e.g. Andreoli and Polla Reference Andreoli, Polla, Vos Raaijmakers and Maurina2019, 234). Though no detailed studies have yet been published for Bulla Regia, the ceramic profile is similar in late antiquity (pers. obs. of material in site reserves). Wheelmade RKW and painted ceramics (dated to late fifth/sixth–seventh centuries) are characteristic of late antique contexts, including in the Church of Alexander (Carton Reference Carton1915b, 122–25), the funerary church (Chaouali et al. Reference Chaouali, Fenwick and Booms2018, 195) and the baths of Julia Memmia (Broise and Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993, 95).

By the ninth century, analysis at Chimtou and Bulla Regia has identified distinct shifts in the ceramic repertoire caused by different consumption patterns and dining habits. Common late antique types such as flanged bowls or mortars disappeared. The shift towards larger vessels – already partly observed in the sixth century – that are also used as tablewares continues. So called Maâjnas replaced pans and casseroles and new large basins and filter jugs occurred in large quantities. Cooking ware was exclusively handmade, however, a few jars were still made in ‘Calcitic Ware’ – a technique that might bridge the seeming gap between late antique and medieval pottery assemblages. The almost complete absence of imported amphorae continued at Chimtou (von Rummel and Möller Reference von Rummel, Möller, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019, 209), with the exception of one rim that could be attributed to an imported amphora D'Angelo E1/2 from Sicily.

Strikingly, there is evidence at both sites of a significant intra-regional trade in lead-glazed tablewares (cups and bowls) produced largely in the region of Kairouan in the late ninth and tenth centuries. The late ninth–tenth century yellow ceramics of Raqqada (‘jaune de Raqqada’) are extremely distinctive, with their mustard-yellow lead glaze and their abstract designs in green (copper) and brown (manganese) (Daoulatli Reference Daoulatli1995, 72; Gragueb Chatti Reference Gragueb Chatti2013, 268). Their production required the mastery of new and technologically challenging glazing techniques, as well as the acceptance of new forms and decorative styles by consumers. The new technique was accompanied by a decorative repertoire of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures (especially birds) and the addition of certain Arabic formulae. Significant amounts of ninth–thirteenth century glazed ceramics have been found at Bulla Regia, particularly in the excavations of the baths of Julia Memmia (Broise and Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993, 394; Thébert Reference Broise and Thébert1993, 119, fig. 145) and the theatre (Ksouri Reference Ksouri2012, 140, Photo 88). A particularly splendid intact bowl of the so-called ‘jaune de Raqqada’ type dating to the late ninth or early tenth century has been published (no precise findspot given) which depicts a stylized peacock and repeats in Kufic script the term al-malik (sovereignty) twice (Louhichi Reference Louhichi2010, 71). At Chimtou, small amounts of Sabra al-Mansuriya glazed ware were found in the forum excavations (von Rummel and Möller Reference von Rummel, Möller, Bockmann, Leone and von Rummel2019, 208), including a large bowl of brown decoration and greenish glaze produced in the eleventh or twelfth century (published in Möller et al. Reference Möller, Pamberg, Touihri, Khanoussi and von Rummel2012, 33, fig. 21.5). These glazed ceramics were widely diffused across Africa and Sicily and are attested in almost all Tunisian medieval assemblages (Gragueb Chatti Reference Gragueb Chatti, Anderson, Fenwick and Rosser-Owen2017).

The majority of ceramic forms, however, seem to be produced locally or regionally in both late antiquity and the middle ages, as suggested by the composition of fabrics and clay. Thus far no kilns or wasters have been identified at Chimtou, but pottery kilns – no longer visible – were identified at Bulla Regia by Carton in both the north-east baths (Carton Reference Carton1915a, 185, f.) and the baths of Julia Memmia which he dated to the medieval period (Carton Reference Carton1909, 583, Reference Carton1922, 333). Our ongoing petrographic analysis of the different commonwares, cooking wares, finewares (ARS) and glazed ceramics should demonstrate which forms and wares were produced locally, and which were imported from other regional production sites in the late antique and medieval periods.

Conclusion

Approaching urban transformation from a micro-regional perspective offers new insights into settlement dynamics in late antiquity and the early middle ages, as well as identifying priorities for future research. Though our analysis of the Central Medjerda Valley rests primarily on the better-studied urban sites of Chimtou and Bulla Regia, it has established a regional baseline for these sites which can be compared to other towns in the immediate region and elsewhere in the Medjerda Valley as new data emerges. Comparison of Chimtou and Bulla Regia has highlighted several striking similarities in their late antique and medieval urban trajectories. Both were flourishing in the fourth and fifth centuries and there is significant evidence of investment in, and repair of, public buildings, the construction of churches and elite housing at both sites. In the same period, however, some buildings – particularly pagan temples – seem to have been targeted as sources of well-cut stone and marble and dismantled. This trend continues in the sixth century when there was significant new church construction and renovation at both sites, as well as further dismantling and repurposing of public buildings, including baths. This sixth-century building activity probably reflects Byzantine investment after the reconquest, which is also attested in the region by the Justinianic fortifications at Bordj Hellal as well as an increase in the number of bishops in the region (see Leone Reference Leone2011 for the latter). The overwhelming picture is of a dynamic urbanism featuring cities under constant development, with evidence of contemporaneous investment, transformation and abandonment across individual sites.

There are also some important differences: Chimtou seems to undergo much more systematic and large-scale dismantling and despoliation of its public monuments (temples, theatre, amphitheatre) than Bulla Regia, which as we have suggested, may reflect state involvement. However, this does necessarily indicate – as often argued – that Chimtou was much reduced after the abandonment of the imperial quarries. The recent discovery of the (perhaps martyrial) monumental church complex, constructed in the late fourth/early fifth century and renovated in the sixth century, as well as the new churches probably constructed in the sixth century, complicates the picture significantly. The scale and expense of this complex shows that Chimtou remained a focus of investment and an important Christian centre, even though it has fewer attested bishops than Bulla Regia where, as yet, only churches on a much smaller scale have been found. Similarly, while both Thuburnica and Bordj Hellal have large enceintes (the latter, securely-dated Justinianic wall built in standard Byzantine construction technique), there is no evidence of fortification at Chimtou, and Bulla Regia possesses a series of scattered fortifications which seem to protect the main east–west road of the town.

In the medieval period, further similarities have been identified. Both towns were certainly much reduced from their fourth–fifth century extent but had much more widespread medieval occupation into the twelfth–thirteenth century than was previously thought, even as it remains unclear whether Chimtou was abandoned in the eighth century and then reoccupied. In both cases, while the overall size of the towns contracted, habitation clustered into a nucleated settlement in the same place as the original pre-Roman core. Though only limited excavation has been conducted, medieval houses seem to be of similar construction types and associated with silos, artisanal or agricultural activity in the form of presses and hand mills. Though these smaller medieval settlements appear more agricultural in nature, their inhabitants were integrated into larger trade networks as is attested by access to glazed ceramics and the presence of some substantial medieval coin hoards. Further excavations are needed to establish the extent and layout of these medieval settlements, as well as the fortified settlements of Bordj Hellal and Thuburnica which may have served as medieval settlements of some size.

Our findings at Bulla Regia and Chimtou raise important questions about urbanism and settlement patterns in the region after the Arab conquests. As yet, we know very little about the early medieval history of the most important towns in the region such as Béja (Vaga) and El Kef (Sicca Veneria) which are described in some detail by the Arab geographers and continue to be occupied today. Certainly, smaller towns are occasionally mentioned in passing, such as Balta, to the north of Bou Salem, which has sizeable remains, including a ‘Byzantine fort’ (AAT XXV, 8); its walls provided refuge during the rebellion of Abu Yazid against the Fatimids (Cambuzat Reference Cambuzat1986, 50–1). Dougga also continued to be a medieval centre, probably without interruption, gaining new baths outside the citadel in the ninth or tenth century, though its medieval layers continue to be overlooked by archaeologists. Elsewhere in Tunisia, at sites such as Jama (Zama Regia) and Henchir es Souar (Abthugni), there is evidence for continuity of occupation at smaller urban sites, particularly inside the walled zone of the sites, but not continuity of municipal function (Touihri Reference Touihri, Nef and Arcifa2014; c.f. Bartoloni et al. Reference Bartoloni, Ferjaoui, Kerim Abiri, Milanese, Ruggeri and Vismara2010, 2022 who suggest a period of abandonment between the seventh and ninth centuries). In the broader Medjerda region, stratigraphic excavations at Uchi Maius and Althiburos show a similar patten to Chimtou with clear signs of abandonment in streets and public areas between late antique layers and later medieval reoccupation of the ninth or tenth century (Gelichi and Milanese Reference Gelichi and Milanese2002; Kallala and Sanmartí, Reference Kallala, Sanmartí, Kallala and Sanmartí2011, 43). At Musti there is a deep layer of colluvium visible between the late antique and medieval housing lining the street in the lower town (pers. obs.). The old forum at Uchi Maius has a similar abandonment layer separating a lime kiln in the late sixth–seventh century from housing of the tenth–twelfth century. Here, however, the entire town may not have been abandoned, but instead reduced to the walled citadel at the high point of the site, which seems to have been occupied in the eighth–ninth century before being given over to similar housing to that found in the forum and Milanese (Reference Milanese2003, 31) notes that the contexts of the transitional period are characterized by slipped ceramics, probably dating to the seventh–ninth century. In all these cases, stratigraphic excavations have only been conducted on a fraction of the site and new work in other zones, particularly in residential areas, may well complicate this picture as it has at Bulla Regia and Chimtou.

This article has demonstrated the potential of revisiting in detail the reports of earlier excavations. There is much to be done, however. Dating the late antique and medieval transition remains one of the greatest challenges for scholars of this period. Targeted excavations of different areas of sites in conjunction with systematic radiocarbon dating programmes can establish chronological sequences for urban development, as well as establishing chronological benchmarks for diagnostic material culture. Non-invasive survey techniques, such as geophysics and UAV (drone survey), offer further potential to fill in lacunae in our understanding of site plans, while careful topographic and photogrammetric recording of standing buildings can, as we have shown, provide new insights into later building phases. However, sites do not stand alone in their landscape, and extensive survey (ideally with test-pitting) is essential to integrate rural and urban settlement into a coherent micro-regional narrative. Finally, we must expand this type of analysis to other zones of the Medjerda Valley to understand the dynamics of regional change, particularly in areas where there is firm evidence of intensive medieval occupation, such as around the regional centre of Béja (Vaga). It is only through a comparative regional approach that we can fully appreciate the complexities of late antique and medieval urban life and fully interrogate some of the presumed differences between late antique and medieval cities in North Africa.

Acknowledgments

This article was written within the project ISLAMAFR-Conquest, Ecology and Economy in Islamic North Africa: The Example of the Central Medjerda Valley, a tri-national project conceptualized and directed by Moheddine Chaouali, Corisande Fenwick and Philipp von Rummel. The project is funded through a joint-scheme between the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) (Grant no: AH/T012692/1) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (Grant no: RU 1511/4-1). The project remains indebted to Prof. Faouzi Mahfoudh, Director of the Institut National de Patrimoine for his support. We thank Elizabeth Fentress, Victoria Leitch and the referees for their helpful comments.