Introduction

In 1845, Sir John Franklin in command of Her Majesty’s Ships (HMS) Erebus and Terror entered the Canadian Arctic with 129 men on board for what was expected to be the completion of discovery and transit of “The Northwest Passage.” The ships captained by Captain Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier (Terror) and Commander James Fitzjames (Erebus) were provisioned for 3 years and contained the latest technology of their day (Cyriax, Reference Cyriax1939).

By 1848, having not heard anything from the expedition, the Admiralty responding to concerns of family and friends of the crews sought to rescue the crews. Over the next several years, British and American search and rescue expeditions resulting in nearly 40 ships scoured the Canadian Arctic in search of news of the expedition (Cyriax, Reference Cyriax1951; Gillies Ross, Reference Gillies Ross2002; Schwatka & Stackpole, Reference Schwatka and Stackpole1965; Wright, Reference Wright1959). In 1850, graves and relics were found on Beechey Island indicating that the expedition had overwintered at that location in 1845–1846 (Beattie, Reference Beattie1987). In 1854, Inuit testimony given to Dr John Rae of the Hudson’s Bay Company indicated that many white men had died of starvation along the shores of King William Island (KWI) and west of the Back River (formerly Great Fish River) (Fig. 1). Critically, Rae was told that members of the crew had resorted to cannibalism in their struggle for survival (McGoogan, Reference McGoogan2003). Not until members of the Fox Expedition (1857–1859), captained by Francis Leopold McClintock, reached the shores of KWI that definitive news of the fate of the expedition was discovered (M’Clintock, Reference M’Clintock1860). In a written record recovered from Victory Point, it was learned that the Franklin Expedition had become trapped in the ice of Victoria Strait in September of 1846 (Fig. 1). Marginal notes made to the record in 1848 indicated that Franklin had died on 11 June 1847, and in April 1848, the remaining 105 men had deserted their ships and were headed for the Back River (M’Clintock, Reference M’Clintock1860) (Fig. 1). It is likely that many turned back to reman the ships, but ultimately none of the crew survived (Woodman, Reference Woodman1991).

Fig. 1. Map of Nunavut and King William Island. The Franklin’s Expedition left England in Spring 1845, and according to the Victory Point cairn note, “Having wintered in 1846–1847 at Beechey Island, in lat. 74 43′ 28″ N., long. 91 39′ 15″ W., after having ascended Wellington Channel to lat. 77°, and returned by the west side of Cornwallis Island.” The accepted dates of the wintering at Beechey Island was 1845–1846 as learned from the grave markers of three members of the crew. Later the ships proceeded towards King William Island and the “H.M.S ships ‘Erebus’ and ‘Terror’ wintered in the Ice in lat. 70 05′ N., long. 98 23′ W.” (Victory Point Note). On 22 April 1848, the ships were deserted, and the crews commenced a journey towards Back River. The possible path of travel by crew after abandoning Erebus & Terror is presented in the red dashed line. Evidence also suggests that at least some of the crew attempted a return to the ships after an initial abandonment in 1848 (purple dashed line). Sŭ-pung-er reported travelling from Pelly Bay to Cape Felix, and then along the coast to find materials belonging to White men. The reported route of travel by Sŭ-pung-er and his uncle is presented in the green dashed line. The map is replicated with minor alterations from Gross and Taichman (Reference Gross and Taichman2017).

The American Charles Francis Hall, in 1860, launched the first of two expeditions to recover any remaining Franklin Expedition survivors, relics and papers (Hall, Reference Hall1865). Unfortunately, Hall was not able to reach KWI during his 1860–1862 expedition; however, he did befriend an English-speaking Inuit couple named “Ipirvik, E-bier-bing, Ei-bier-bing or Joe” and “Too-koo-li-too, Too-kee-li-too or Hannah.” Together, Ipirvik, Too-koo-li-too and Hall would travel together on all three of Hall’s expeditions. Hall returned to the Arctic in 1864, where during the next 5 years, with Too-koo-li-too and Ipirvik’s help, he interviewed Inuit who had encountered members of the Franklin crews and/or collected and traded for relics of the Franklin Expedition (M’Clintock, Reference M’Clintock1881). Hall recorded the testimony in his travelling notebooks and private journals and in letters sent to his sponsors. Unfortunately, Hall died prior to publishing the findings of his second expedition, and it was left to J.E. Nourse to compile Hall’s vast works (1879) (Nourse, Reference Nourse1879). Many of the journals, relics and ethnographic items which Hall collected from his travels and were retained by him are housed in The Archive Center of the National Museum of American History (NMAH), or in the Museum Support Center of the Smithsonian Institution (Washington, D.C.). A considerable number of other Franklin Expedition relics that Hall collected were given to Franklin’s widow, Lady Jane Franklin, upon his return to the US (Hall, Reference Hall1869; Walpole, Reference Walpole2017).

In the spring of Reference Hall1866, Hall conducted interviews with a native Pelly Bay on the Boothia Peninsula, Nunavut named Sŭ-pung-er (variously written Su-pung-er, Su-pŭng-er and Sū-pŭng-er in Hall’s journals). On Friday, 4 May Reference Hall1866, at Hall’s 40th Encampment on the ice of the sea of Ak-koo-lee (Near Pelly Bay, Lat. 68F8-00-00 N, Long. 88F8-17′-15″ W), Hall learned through Too-koo-li-too serving as interpreter that three winters prior, Sŭ-pun-ger and his uncle had visited KWI in search of objects left by the Franklin crew including wood and metal (Fig. 1) (Hall, Reference Hall1866; Hickey, Reference Hickey1984; Savelle, Reference Savelle1985). Sŭ-pung-er told Hall that he had found an underground site or “vault” on KWI, which Hall believed contained expedition records and a grave (Hall, Reference Hall1866). The site has become known as the Sŭ-pung-er’s vault, Franklin’s vault or Franklin’s grave (Hall, Reference Hall1866; Nourse, Reference Nourse1879; Woodman, Reference Woodman1991). Sŭ-pung-er’s testimony included the description of an unusual wooden marker described as a “pillar, stick or post” which was constructed by the Franklin Expedition. Through Too-koo-li-too serving as interpreter, Sŭ-pung-er stated that the shape of the pillar was “peculiar” to the Inuit. Sŭ-pung-er indicated that the wooden “pillar” that marked the location of the site was securely fastened in the ground, and it could be seen from the shore (Hall, Reference Hall1866). Sŭ-pung-er revealed that he and his uncle had tried to remove the pillar for its wood (Hall, Reference Hall1866). The most critical parts of the testimony are as follows (Hall, Reference Hall1866):

“Friday May 4th 1866.

“40 th Encamp on the ice of the sea of Ak-koo-lee.”

“Obs. ± Notes of the day.

It is now VII h -20 m PM & really I have so much to note I am at a loss where to begin. Several most important facts have been communicated to me to-day two of wh. [which] are as follows: First – Some four years ago one of the men of the Pelly Bay nations in whose village we are encamped, whose name is Su-pŭng-er visited Kee-ik-tung (King Williams Land) [Hall referred to King William Island as King William Land] + passed from one end (the south end) to the other (the N. end) in summer when the snow was entirely off the ground. He was accompanied by his father’s brother. Their object was to search for things that once belonged to the white men who had died on + in the neighborhood of King William’s Land.”

“Through Too-Koo-li-too + E-bier-bing as interpreters Sŭ-pung-er has told me many interesting incidents relative to this journey….”

“I then asked Too-Koo-li-too to have Su-pung-er describe that place on the ground he + his uncle found when near the North extreme of King William’s Land + wh. [which] had attracted their particular attention. He said that near the sea ice was a large tupik [tent] of same kind of material as that now covering the habitation of E-bur-bing & Too-Koo-li-too…”

“A little way inland from this tupik wh. [which] was not erect but prostrate he & his uncle came to place where they found a skeleton of a Kob-lu-la (white man) some parts of it having clothing on while other parts were without any it having been torn off by wolves or foxes. Near this skeleton they saw a stick standing erect wh. [which] had been broken off – the part broken off lying close by. From the appearance both he and his uncle thought the stick, or rather small pillar or post, had been broken off by a Ni-noo (polar bear). On taking hold of that part of the wooden pillar wh. [which] was erect they found it firmly fixed – could not move it a bit. But what attracted their attention the most on arriving at this pillar was a stone - or rather several large flat stones lying flat on the sandy ground & tight together. After much labor one of these stones was loosened from its carefully fixed position + by great exertions of both nephew & uncle the stone was lifted up a little at one edge just sufficient that they could see that another tier of large flat stones firmly + tightly fitted together was underneath. This discouraged them in their purpose wh. [which] was to remove the stones to see what had been buried there for they was quite sure that something valuable was underneath. On my asking Su-pung-er to take a long handled knife wh. [which] I handed to him, + mark out on the snow about the shape + size of the spot covered by these flat stones, he at once did as I desired - & the spot marked was some 4 feet long + two feet broad. The pillar of wood stood by one side of it - not at the end but on one side. The part of the stick or pillar standing was about 4 feet high as indicated by Su-pung-er on my person + the whole height on replacing the part broken off six feet from the ground. As nephew + uncle were in want of wood they spent a good deal of time in digging the part erect loose. It was deeply imbedded set in the sand. The shape of this stick or pillar was a peculiar one to these natives. The part in the ground was square. Next to the ground was a big ball + above this to within a foot or so of the top the stick was round. The top part was about 3 or 4 inches square. No part of it was painted – all natural wood color.”

This passage provides the most critical information we learn regarding the pillar/stick/post. It was a piece of wood, naturally coloured of approximately 4 feet high tall (Hall, Reference Hall1866). A 2-foot-long, 3- or 4-inch square piece was found broken off of the top of it which was lying nearby. The part of the pillar which was in the ground was stated to be square, and next to it was a ball-shaped structure and, above this, to within a foot or so of the top of the pillar, was round. The pillar was of sufficient strength that Sŭ-pung-er and his uncle surmised that a polar bear must have broken off the piece which was lying nearby. When the Inuit tried to remove the pillar, they found it was strongly fixed in the ground. Whether Sŭ-pung-er and his uncle succeeded in removing the object was not explicitly stated, but implied. Regardless, they did spend considerable time at the activity.

The testimony continues:

“As soon as Sŭ-pung-er had completed his description about the stones fitting how carefully they had been placed so as to make it impossible for any water to get between them, Too-koo-li-too said to me with a joyful face, ‘I guess I can tell just what this is for – for papers!’ And, said I, I think so too. - Time + again Sŭ-pung-er said that the stones were just as if they were tied together. My conclusions are that the stones were laid in cement and that they cover a vault of the precious documents of the Franklin Expedition or the greater part of them.”

At Hall’s request, Sŭ-pung-er drew the structure he saw on KWI; “Su-pung-er has on this page at my desire just been marking out with my pen the vault covered with stone. It is a very crude draft. As Nuk-er-zhoo (who entered in at the time Su-pung-er was making it) placed his finger on this plan before the ink had dried [unclear] defacing it I will have Su-pung-er make another & then proceed to describe it.” The drawing and an interpretation of the structure are presented in detail in Gross and Taichman, suggesting the pillar, the broken piece and the ball-like structure comprised of a Cross Triumphant (Gross and Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017). Sadly, a second drawing has not been located. The three-dimensional representation of the vault and what was underneath the large flat covering stones on the ground resembles a contemporary burial vault. Hall also requested that Sŭ-pung-er mark out the “size of the spot covered by these flat stones, he at once did as I desired & the spot marked was some 4 feet long + two feet broad” on Friday, 4 May 1866. On 4 June 1866, further describing the vault, Hall record that Su-pun-ger stated that he and his uncle “found a hole of the depth from the feet up to the navel + of a length more than a man’s height + wider than the width of a man’s shoulders + this was all nicely walled with flat stones placed one above another, flatwise. (Hall, Reference Hall1866).”

Today, the location of the vault and the pillar that Sŭ-pung-er described have remained a mystery (Gross, Reference Gross2018; Woodman, Reference Woodman1995). Sŭ-pung-er believed he was at “Victory Point” and indicated this location to Hall on a map (Fig. 1). Yet the area around Victory Point and the nearby Crozier’s Landing where in 1848 the crews came ashore have been searched repeatedly over many years by professional and privately organised individuals (Coleman, Reference Coleman2020; Gross, Reference Gross2012, Reference Gross2018; Potter, Reference Potter2016; Stenton, Reference Stenton2014, Reference Stenton2018; Trafton, Reference Trafton1991; Woodman, Reference Woodman1995).

Many have speculated that Sŭ-pung-er’s or Franklin’s vault or grave may have been the burial site of a high-ranking officer, perhaps even Sir John Franklin himself (Gross and Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017; Kamookak, Reference Kamookak2017; Potter, Reference Potter2016). It has also been argued that the site was the location of documents deposited as a haven to ensure their safety after the ships were abandoned, or both. To date, the site has not been identified and its very existence questioned (Cyriax, Reference Cyriax1969; Potter, Reference Potter2016). In fact, Hall’s friend and confidant Captain C.B. Kilmer met Sŭ-pung-er and describes his observation in a letter as “The native who told the story, is a rather hard customer and I have but little faith in anything he says” (Kilmer, 1868). The mystery surrounding Sŭ-pung-er and his testimony continues.

The recent discovery of the HMS Erebus and Terror, in 2014 and 2017, has cast new interest on the Franklin Expedition and its mysteries (Eschner, Reference Eschner2018; Kuta, 2023; Shapton, Reference Shapton2016). The story of the discovery of a “vault” by Sŭ-pung-er, reported by Hall, has become the subject of public interest in recent years, and any clue or artefact which could provide clarity to the mystery is therefore of great value. In fact, as Dr. Russell Potter once stated: “For some, it’s even more of an ‘Arctic Grail’ than Franklin’s ships, and with Erebus and Terror found, it’s the one thing that has evaded searchers the longest: the fabled tomb of Sir John Franklin (Potter, Reference Potter2018).” Herein, we describe a model of the pillar marking the vault site, made by Sŭ-pung-er, which Hall brought back from the Arctic and was included in Hall’s list of relics.

Results

While seeking clues to the location of the Sŭ-pung-er’s vault site, the Archives Center at the National Museum of American History was visited during the period of 2016–2018. During subsequent transcription of Hall’s works, a notebook containing a list of Sir John Franklin’s Relics that Hall had brought back from the Arctic and a list of relics delivered to Lady Franklin on 13 August 1870 were examined (Hall, Reference Hall1869). To our knowledge, the lists have never been made public.

The Sir John Franklin Relics Notebook of Hall’s consists of 22 pages (Hall, Reference Hall1869). In most instances, Hall wrote across two pages in the notebooks where, on the left-hand pages, are listings of the relics, his catalogue numbers and their descriptions (Fig. 2a, b). On the adjoining page, Hall included the disposition of the item. For items that he provided to Lady Franklin, Hall included the dates delivered to her possession (Fig. 2a, b). In at least one case, Hall signified that an item went to “G.” While he does specifically indicate who or what “G” stands for, it likely signifies Henry Grinnell, one of Hall’s major benefactors who supported his explorations. For items that he provided to the Smithsonian Institution, he enclosed the letter “S” in brackets (“S”) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2. Hall’s Partial List Sir John Franklin Relics compared to Smithsonian Catalogue book. Images and cutouts of pages illustrating Hall’s notation of the wooden model of a pillar found on King William Land (Island) by Supunger (Sŭ-pung-er). (a) Hall’s Journals Listing Franklin Relics (b) Pages 15, 16 of Halls Journal Listing Franklin Relics (Hall, Reference Hall1869). (c) Expanded view of pages 15 and 16. (d) Illustration of where Hall’s Franklin Relics were entered into the Smithsonian Museum’s Catalogue and described. (e) Expanded view of the catalogue page showing item 10126, #68 entered.

The notebook records 77 items which Hall considered worthy of labelling. Many of the items were derived from Parry’s 1824–1825 and Ross’s 1829–1833 expeditions. Amongst those related to the Franklin Expedition, 21 were presented to Lady Franklin on either 12 or 13 August 1870. Grinnell received a long strip of copper marked with the Queen’s broad arrow on 22 January 1871. The remaining relics deposited by Hall into the Smithsonian Institution were ascribed to the Franklin Expedition. Among these and others were a table fork with the crest of an eels head and laurel branches (Franklin’s crest), small fragments of a clinker-built boat with iron nails embedded in them possibly derived from the Boat Places (NgLj 2 and NgLj-3) in Erebus Bay (Stenton, Reference Stenton2018; Stenton, Keenleyside, & Park, Reference Stenton, Keenleyside and Park2015) (Fig. 1), and piece of a brass tube or curtain rod possibly derived from Crozier’s landing (Fig. 1).

Most interestingly, Hall’s notebook is the indication of a relic labelled as No. 68. This item was described by Hall as a “wood model of wood pillar found on KWL (King William Land) by Supunger” (Fig. 2a–c) (Hall, Reference Hall1869). Evidently, this item was logged into the Smithsonian’s Museum Catalogue 3, Anthropology 8301–14100 as item 10126. In this case, the Smithsonian description was described as “Stick found by Eskimo in ground near Victory point, whittled by white men” and was received from Capt. C.F. Hall on 2 February 1871 (Fig. 2d, e). This item matched the description that Sŭ-pung-er provided on 6 May 1866 as a “stick, or rather small pillar or post,” of which part was buried in the ground (Hall, Reference Hall1866).

On 20 and 21 March 2023, arrangements were made to visit the Smithsonian Museum of American History to identify and photograph the Hall relics and where possible correlate them with the list in Hall’s notebook. In many cases, the relic labels were attached by a thin white string and paper hang tag of approximately 35 x 22 mm. In select cases, Hall fashioned the labels by hand and used brown ink to demarcate the identity of the items. Not all the items, however, retained their labels, such that only the string has been retained. Of the 77 items listed in Halls Relic Book deposited to the Smithsonian, only 12 could be identified specifically by their numbered tags, but a total of 28 could be identified based on their appearances, description or tags subsequently provided by the Smithsonian at some later date.

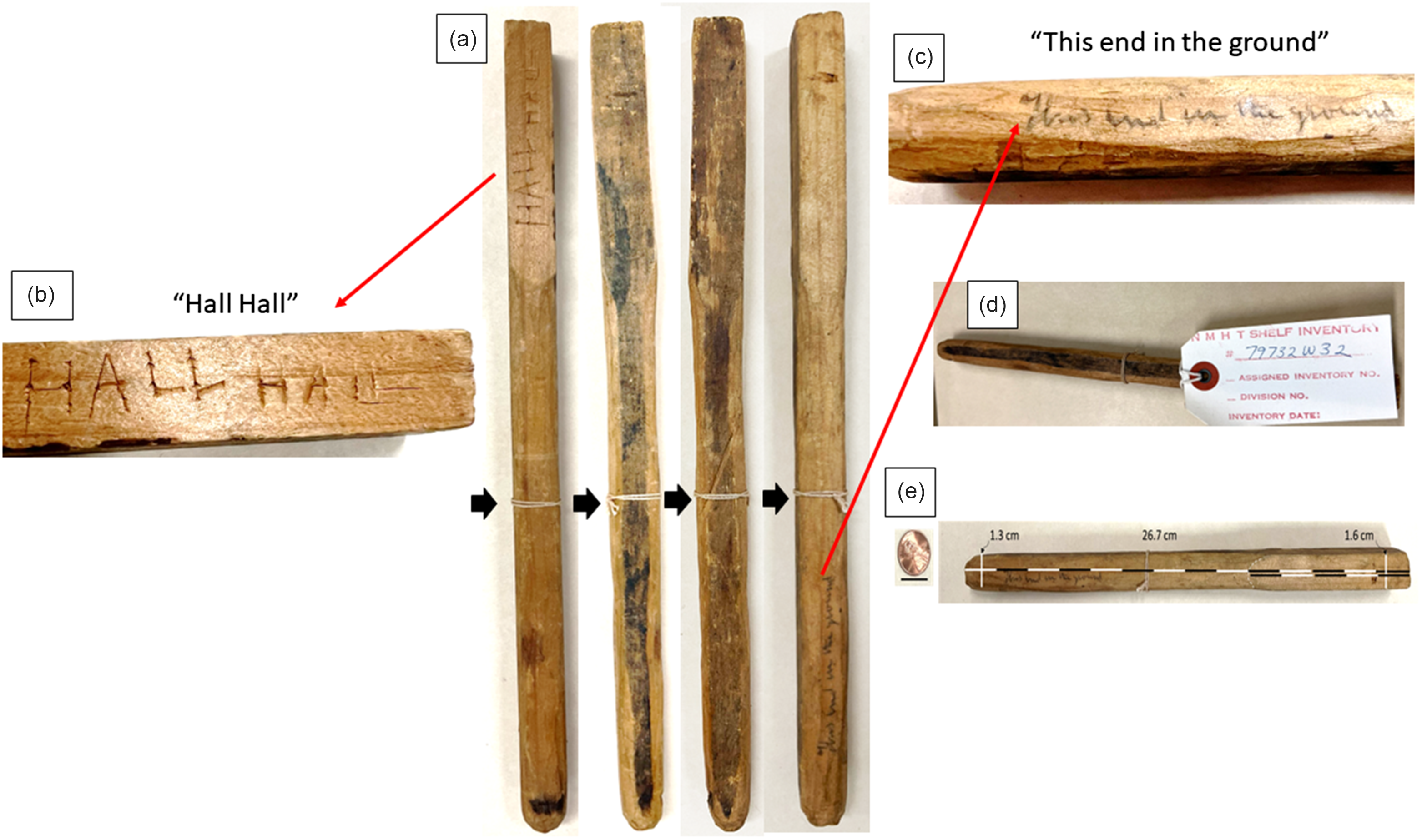

The miniaturised model of the pillar or post, found at the vault site, which was replicated by Sŭ-pung-er, was readily apparent among the collection. A light-coloured piece of wood approximately 26.7 cm long was identified as it clearly was handmade and resembled a pillar (Fig. 3). The object at its thickest point was square in shape and 1.6 cm wide. At the opposite end, it tapered to a rounded blunt point of 1.3 cm wide. The squared part extended 9.52 cm of the object’s length. The wood was likely pine or of similar softwood and, while not painted, had a darker patina in the centre of each side running the length of the object. A white string, which had evidently held a label, was present tied around the middle of the model, but unfortunately, the label itself was missing (Black arrows, Fig. 3). On one side of the square portion of the model are the words “Hall Hall.” These words appeared to be pressed into the wood by the point of a knife. Near the rounded end of the object was an inscription written in pencil: “This end in the ground.” Based on the similarity in handwriting with other documents in the Hall Collection at the Smithsonian Institute, it is likely that the notation was made by Hall himself.

Fig. 3. Model of pillar or stick found on KWI by Sŭ-pung-er demarcating the Franklin Vault. Sŭ-pung-er’s model of the pillar found on King William Island located to the side of the vault observed by Sŭ-pung-er and his uncle in approximately 1863. (a) All four sides of the model are shown. Inserts of the carvings of (b) “Hall Hall” and (c) handwriting of Charles F. Hall in pencil “This end in the ground.” (d) Inventory tag currently on the artefact. (e) Sizing of the artefact. Black arrows point to the string originally placed by Hall to identify the relic.

Perhaps the most dramatic illustration of the providence and importance of the model placed on it by Hall himself was its inclusion in a publication on 23 October 1869, in Harpers Weekly. The article includes a list of relics that Hall brought back from KWI including “a portion of one side of a boat, clinker-built and copper-fastened, a small oak sledged-runner reduced from the sledge on which the boast rested, part of the mast of the Northwest Passage ship, chronometer box, with its number, name of the maker and the Queen’s broad arrow engraved on it. Two long heavy sheets of copper, three and four inches wide, with counter-sunk holes for screw-nails…” Included with the article is a diagram entitled “Relics Found by Captain Hall In His Arctic Exploring Expedition.” On the top right-hand corner, second from the right, is the model of the pillar, with its tag. Interestingly, the spelling of the words “Hall Hall” are backwards (Fig. 4). The article, however, makes no mention of the model, post or pillar.

Figure 4. Illustration of Hall’s Franklin Expedition relics. (a) Illustration of the providence and importance of the model, which were placed on it by Hall himself, was its inclusion in a publication on 23 October 1869 in Harper’s Weekly. (b) Enlargement of the pillar relic orientation as presented in Harper’s Weekly. (c) Corrected model and its orientation of the drawing of the relic. (d) Comparison of Sŭ-pung-er pillar to image presented in Harper’s Weekly.

Discussion

An objective assessment of the model is revealing. The first intriguing aspect is both Hall’s and the Smithsonian’s description of the artefact itself. As mentioned previously, Hall wrote in his Franklin Expedition relics journal “Wood model of wood pillar found on KWL (King William Land) by Supunger” (Fig. 2a–c). In the Smithsonian’s Museum Catalogue 3, Anthropology 8301–14100 item 10126 was described as “Stick found by Eskimo in ground near Victory point, whittled by white men” (Fig. 2). This matches many of the descriptions Sŭ-pung-er provided on 6 May 1866, as a “stick, or rather small pillar or post” of which part was buried in the ground and marked the site that Sŭ-pung-er and his uncle found 4 years previous to 1866. Specifically, the words chosen to describe the object as a model of the “pillar” or “stick” are so precise that there can be little doubt that they correspond to the object described in 1866 (Hall, Reference Hall1866). Furthermore, the item listed in both catalogues, while they were not identical in description, clearly describe a similar object, which could only refer to the pillar and the numbering system in both Hall’s Franklin Relic Notebook (Hall, Reference Hall1869) and the Smithsonian Museum Catalogue indicating the item was originally marked as #68. In addition, this item was noted in Hall’s notebook as having been deposited in the Smithsonian Institution as signified by the letter “S” in his relic’s notebook. Critically, no item matching this description or numbering appears in any list of items provided to Lady Jane Franklin from Hall. The list provided to Jane Franklin is also housed in the same folder in the Archives Center 2157.105–107. One interesting note is that whoever authored the entry in the Smithsonian’s Museum Catalogue likely considered the artefact to be an original relic rather than a model reconstruction based on the phrasing.

Hall wrote as part of his 1866 interview with Sŭ-pung-er that “The part in the ground was square.” Yet, the blunt end of the model bears the inscription “This end in the ground.” Hall met with Sŭ-pung-er at least twice: once in 1866 and a second time in 1869. For a limited time in 1866, they travelled together. To our knowledge, there is no mention in Hall’s journals where he requested the manufacture or received a model of the pillar, which Sŭ-pung-er made. Yet in 1866, Hall did request that Sŭ-pung-er draw in his notebook a diagram of the vault and to lay out its size on the ground (Gross and Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017). It would be consistent with these other actions, at the request of Hall, that the model would have been generated in 1866. It is also likely that Hall wrote the note on the side of the model at or near the time of its construction. However, it is also possible that Sŭ-pung-er generated the model in 1869. If the model were constructed in 1869, Sŭ-pung-er might have led Hall to believe that the rounded blunt end belonged in the ground at that time. Hall was travelling during his trip to KWI in 1869 when he again met Sŭ-pung-er and would not have had his notebooks from 1866 with him at the time to assess concordance. A third possibility is that the translation of the testimony that Hall received from Sŭ-pung-er may have been faulty in 1866. This would have resulted in Hall’s recording the part in the ground as being the square part. It is also important to note that part of the original description, in 1866, of the pillar included the following phrasing “The top part was about 3 or 4 inches square.” Thus, there appeared to be a square portion of the pillar at both ends of the structure, and therefore this model is in keeping with the square part, which was in the ground originally, but may not have been visible prior to its extraction.

It is important to recognise a difference between the 1866 testimony that Sŭ-pung-er provided to Hall, the model is the ball structure; “Next to the ground was a big ball.” There is no indication of a ball generated on the model. One may speculate that this was too difficult to fashion from the evidently milled and squared 26.7 x 1.6 cm piece of wood stick which Hall likely provided for the project. The reason for this deviation is obvious. It would have required a second piece of wood to make. If this second piece were brought back to the US and deposited into possession of the Smithsonian Institution, one might expect to find a second piece of wood in which the blunt end or possibly, the square end could fit into. It is not difficult to conceive that an artefact “wood model of wood pillar found on KWL (King William Land) by Supunger” or “Stick found by Eskimo in ground near Victory point, whittled by white men” could have been confused for an artefact of daily living made by the Inuit and therefore housed separately from the Franklin Expedition relics collection as part of Hall collections of ethnographic or cultural materials. Interestingly, there are several rounded specimens in the Museum Support Center which house the Hall collections of ethnographic items which could be the matching piece. An example of this is an item labelled as a snow-cane or “shug-un” tip of a snow probe (USNM Number E10276-0) which is used for probing for air holes in ice and under the snow to detect the presence of seals. To prove this theory, however, would require reuniting these items. Examining the model photographs, the end labelled “This end in the ground” is rounded. It is possible that there was a language barrier between Sŭ-pung-er and Too-koo-li-too such that “Next to the ground was a big ball + above this to within a foot or so of the top the stick was round” might have been more intended as “The end towards/next to the ground was rounded off, like a big ball + above this to within a foot or so of the top the stick was round.” If true, the “big ball” might have been a way of describing what the one end of that wooden model looks like. As likely, it is possible that Hall himself misinterpreted the translation of Too-koo-li-too, his interpreter. A final possibility is that Sŭ-pung-er told different versions to Hall on different occasions. Perhaps Sŭ-pung-er did not remember what he had said in 1866 the first time he related the details of the pillar to Hall and when he subsequently carved the model.

A third deviation from what Hall recorded as a “stick or pillar” regards the broken piece of the pillar; “A little back (inland) from this tent, was where his uncle 1 st found a large piece of wood - a post or pillar sticking up + this drew his uncle’s attention to something by it. The pillar was broken off. They both thought it had been broken off by a Ni-noo [Polar bear].” As the standing piece of the pillar was ∼ 4 feet in height, while the top portion within a foot or two had broken off, this leads to interesting speculation. In a prior publication, it was posited that Sŭ-pung-er thought the top piece of the pillar was broken off by a polar bear because it required great strength to break at a height of ∼ 4 feet (Gross and Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017). If true, this could suggest that the pillar may have been a large wooden cross with the weakness being where the cross member was joined to the main part of the shaft (Gross and Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017). If the “big ball’ at the base existed (see previous paragraph for description), it may have represented an orb. Together these pieces might have represented a “Victory Cross” or the “Cross Triumphant,” a most fitting symbol to stand beside the grave of an English Knight if Sir John Franklin were interred beneath it (Gross and Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017). Unfortunately, neither the squared portion of the model nor the rounded portions of it indicated a cross-piece or any other pieces that were broken off the model.

An additional puzzling aspect of the piece is why the model was engraved with Hall’s name twice. It seems unlikely that Hall would have done so himself. Hall typically penned his name in script rather than with block lettering. It is far more likely that Sŭ-pung-er himself used a knife to press engrave Hall’s name into the softwood as a gift for his benefactor. Perhaps copying Hall’s writing. Hall was a generous host to Sŭ-pung-er, supplying him with wood, food and firearms over time. It is also curious that in the Harper’s Weekly diagram of 23 October 1869, it shows the model displaying the “Hall Hall” inscription side rather than the side indicating which end goes into the ground. Perhaps most perplexing is why the engraver displayed the name “Hall” backwards. This cannot be ascribed to a reversal in the engraving process as two other pieces in the diagram are labelled with writing in the correct orientation (Water Proof Hall 250 No 12 [H]e read” and “R102” (Fig. 4). However, it might simply have been a mistake. Further adding to the interest is why this relic was included in the Harper’s Weekly diagram in the first place. It must have signified an object of great importance in Hall’s mind, which becomes more understandable when one considers Hall’s self-stated mission: to recover survivors or documents from the Franklin Expedition. Anything which could assist in the recovery of the documents, such as a signpost marking their location or marking the burial site of a high-ranking officer, was likely significant from Hall’s point of view.

Despite a high level of interest in the Sŭ-pung-er testimony for some Franklin researchers, many searches have failed to identify the site (Coleman, Reference Coleman2020; Gross and Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017; Trafton, Reference Trafton1991; Woodman, Reference Woodman1995). For that reason, some have questioned its existence (Cyriax, Reference Cyriax1969), but even if the “vault” Sŭ-pung-er described does exist and is found, the testimony suggests that it may not contain a wealth of information about the expedition as Sŭ-pung-er described to Hall that it contained water, mud, and sand and a clasp knife and human bones were nearby. Indeed, the entire topic, and anything related to Sŭ-pung-er, is speculative until an archeologic site is discovered. That said, there are several major findings presented in this paper: (i) the finding of a notation in Hall’s journal that there is a model made by Sŭ-pung-er himself of the pillar is a novel and interesting feature of the story regarding the vault. (ii) The identification of a model is, in and of itself, a step in the direction that there may have been a site on KWI. (iii) If a site is located on KWI, it might be argued that the site is not the vault site if the pillar hole reported by Sŭ-pung-er, which is off to the side, is square not round (Gross and Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017). This paper could be useful in that regard. (iv) There has been much speculation that the pillar was a Cross Triumphant (Gross, Reference Gross2018, Reference Gross and Taichman2017). The model may be the bottom part of a Cross Triumphant, or not. (v) The paper describes a relic of the Franklin Expedition, albeit a model. This relic although seen only in a drawing previously is unusual and begs the question of what else is there in the collections which is novel enough to warrant scientific inquiry.

Summary

There is little doubt that Hall and others believed that the testimony which Sŭ-pung-er provided was truthful and described an architectural feature on the Western coast of KWI that was significant (Gross and Taichman, Reference Gross and Taichman2017). Hall wrote in his Reference Hall1866 notebook that “As soon as Sŭ-pung-er had completed his description about the stones fitting how carefully they had been placed so as to make it impossible for any water to get between them, Too-koo-li-too said to me with a joyful face, ‘I guess I can tell just what this is for – for papers!’ And, said I, I think so too. (Hall, Reference Hall1866).” Sadly, the key to finding the feature was the pillar or stick that Sŭ-pung-er and his uncle likely removed in their search for wood which could be seen inland from the shoreline. The location of this site has been, and continues to be, one of the most sought-after for both its significance and as a potential bonanza of information about the expedition. Any clue, or artefact, which could provide clarity as to the site’s nature, is therefore of great value. Herein, we describe a model of the pillar which once may have stood over the grave of a high-ranking naval officer, perhaps Sir John Franklin himself, or over the location of a vault of expedition papers. If either were located, they might prove invaluable in our understanding of the accomplishments and the challenges that the expedition faced in executing their orders to transit the Northwest Passage. The fact that this artefact has been in plain view since 1869 in Harpers Weekly, but not recognized for what it is, is surprising. Its presence and the meaning of the model provide clarity and continued mystery surrounding the Franklin Expedition.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks their families and friends for enduring endless hours of banter regarding the Franklin Expedition and the Northwest Passage. The author is grateful to Susan Taichman-Robins (Philadelphia, PA, USA) and Tom Gross (Hay River, Northwest Territories, Canada) for their helpful discussions and for their ongoing collaborative activities. Mr. Joe Hursey and staff, Charles Francis Hall Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History (NMAH), and Smithsonian Institution were helpful in providing context to the Hall papers. We thank Johnathan Moore and John Ratcliffe, underwater archaeologists of the Underwater Archaeology Team, Archaeology, Collections and Curatorial Branch, Parks Canada Agency, Ottawa, Canada, for initially supplying digital images of Hall’s relics journals. Logan Zachary is to be commended for his suggestion to track down the Hall relics and for the suggestion to put these findings into print, and for extremely helpful discussions. Most particularly, the author thanks Dr Stephen Loring and Jennifer L. Jones of the NMAH for serving as able guides through the Franklin Relics and ethnographic materials. The author also thanks the unnamed reviewers for their assistance in improving the paper.

Competing interests

The author declares none.