6.1 Introduction

Social scientists and policy-makers care deeply about their ability to draw clear causal inferences from research – and justifiably so. But descriptive accuracy also matters profoundly for the success of this enterprise. Correctly identifying relevant parties, choice points, and perceptions, for example, strongly impacts our ability to understand sources of influence on development outcomes, successfully disrupt and overcome obstacles, and identify scope conditions. The challenge is how to tease out this kind of information in interview-based qualitative research.

This chapter draws on a decade of experience in developing policy implementation case studies under the auspices of a Princeton University program called Innovations for Successful Societies in order to highlight ways to address some of the most common difficulties in achieving descriptive accuracy. The program responded to a need, in the mid-2000s, to enable people leading public sector reform and innovation in low-income and low-middle-income countries to share experiences and evolve practical wisdom suited to context. To develop reasonably accurate portrayals of the reform process and create accurate after-action reports, the program carried out in-depth interviews with decision-makers, their deputies, and the other people with whom they engaged, as well as critics. The research employed intensive conversation with small-N purposive samples of public servants and politicians as a means of data collection.Footnote 1 In the eyes of some, this interview-generated information was suspect because it was potentially vulnerable to bias or gloss, fading or selective memory, partial knowledge, and the pressures of the moment. Taking these concerns seriously, the program drew on research about the interaction between survey design and respondent behavior and evolved routines to boost the robustness of the interviews it conducted.

6.2 Background

Accuracy is related to reliability, or the degree of confidence we have that the same description would emerge if someone else reviewed the data available or conducted additional interviews.Footnote 2 Our methods have to help us come as close as possible to the “true value” of the actual process used to accomplish something or the perceptions of the people in the room where a decision took place. How do we ensure that statements about processes, decisions, actions, preferences, judgments, and outcomes acquired from interviews closely mirror actual perceptions and choices at the time an event occurred?

In this chapter, I propose that we understand the interview process as an exercise in theory building and theory testing. At the core is a person we ask to play dual roles. On the one hand, our interviewees are a source of facts about an otherwise opaque process. On the other hand, the people we talk to are themselves the object of research. To borrow the words of my colleague Tommaso Pavone, who commented on a draft of this chapter, “The interviewee acts like a pair of reading glasses, allowing us to see an objective reality that is otherwise inaccessible.” At the same time, however, we are also interested in that person’s own perceptions, and subjective interpretations of events, and motivations. “For example,” Pavone said, “we might want to know whether and why a given meeting produced divergent interpretations about its relative collegiality or contentiousness, and we might subsequently probe how the interviewee’s positionality, personality, and preferences might have affected their views.”

In both instances, there are many potential confounding influences that might blur the view. Some threats stem from the character of the subject matter – whether it is comparatively simple or causally dense (in Michael Woolcock’s terms, i.e., subject to many sources of influence, interactions, and feedback loops; see Chapter 5, this volume), whether it is socially or politically sensitive, or whether the person interviewed is still involved in the activity and has friends and relatives whose careers might be affected by the study. Other threats emanate from the nature of the interviewee’s exposure to the subject matter, such as the amount of time that has elapsed since the events (memory), the extent of contact (knowledge), and the intensity of engagement at the time of the events. Still other influences may stem from the interview setting: rapport with the researcher, the order and phrasing of questions, whether there is a risk of being overheard, and the time available to expand on answers, for example.

Our job as case writers is to identify those influences and minimize them in order to get as close as possible to a true account, much as we do in other kinds of social science. And there are potential trade-offs. A source may be biased in an account of the facts, but, as Pavone suggested in his earlier comments, “he may be fascinating if we treat him as a subjective interpreter,” whose gloss on a subject may reveal how decision-makers rationalized intense investment in a particular outcome or how they responded to local norms in the way they cloaked discord.

The following section of this chapter treats the pursuit of descriptive accuracy as an endeavor very closely aligned with the logic used in other types of research. Subsequent sections outline practices we can mobilize to ensure a close match between the information drawn from interviews and objective reality – whether of a process or of a perspective.

6.3 The Interview as Social Science Research

An interview usually aims to take the measure of something, and any time a scientist takes a measurement, there is some risk of error, systematic or random. We can try to reduce this problem by modeling the effects of our instruments or methods on the information generated. The goal is to refine the interview process so that it improves the accuracy and completeness of recall, whether of events and facts or of views.

First, let’s step back a bit and consider how theory fuels qualitative interviewing, for even though we often talk about this kind of research as inductive, a good interview is rarely free-form. A skilled interviewer always approaches a conversation self-consciously, with a number of key ideas and hypotheses about the subject and the interviewee’s relationship to that subject in mind. The inquiry is exploratory, but it has a strong initial deductive framework.

This process proceeds on three dimensions simultaneously, focused at once on the subject matter; the interviewee’s preferences, perceptions, and biases; and the need to triangulate among competing accounts.

Theory and interview focus.

The capacity to generate good description draws heavily on being able to identify the general, abstract problem or problems at the core of what someone is saying and to quickly ask about the conditions that likely set up this challenge or the options likely tried. At the outset, the interviewer has presumably already thought hard about the general focus of the conversation in the kinds of terms Robert Weiss outlines in his helpful book, Learning from StrangersFootnote 3 – for example, describing a process, learning how someone interpreted an event, presenting a point of view, framing hypotheses and identifying variables, etc. In policy-focused case studies, we begin by identifying the broad outcomes decision-makers sought and then consider hypotheses about the underlying strategic challenges or impediments decision-makers were likely to encounter. Collective action? Coordination across institutions? Alignment of interests or incentives (principal–agent problems)? Critical mass? Coordination of social expectations? Capacity? Risk mitigation? Spoilers? All of the above? Others?

Locking down an initial general understanding – “This is a case of what?” – helps launch the conversation: “As I understand it, you faced ___ challenge in order to achieve the outcomes the program was supposed to generate. How would you characterize that challenge? … This problem often has a couple of dimensions [fill in]. In what ways were these important here, or were they not so important?” Asking follow-up questions in order to assess each possible impediment helps overcome problems of omission, deliberate or inadvertent. In this sense, accuracy is partly a function of the richness of the dialogue between the interviewer’s theoretical imagination, the questions posed, and the answers received.

The interview then proceeds to document the steps taken to address each component problem, and here, again, theory is helpful. The characterization of the core strategic challenges spawns a set of hypotheses. For example, if the key delivery challenge is the need for collective action, then we know we will have to ask questions to help assess whether the outcome sought was really a public good as well as how the decision-maker helped devise a solution, including (most likely) a way to reduce the costs of contributing to the provision of that public good, a system for monitoring contributions, or whether there was one person or organization with an exceptional stake in the outcome and therefore a willingness to bear the costs. In short, the interview script flows in large part from a sense of curiosity informed by theory.

Theory also helps us think about the outcomes we seek to explain in a case study and discuss in an interview. In policy-relevant research we are constantly thinking in terms of measures or indicators, each of which has an imperfect relationship with the overarching development outcome we seek to explain. A skilled interviewer comes to a conversation having thought deeply about possible measures to evaluate the success or failure of an action and asks not only how the speaker, the interviewee, thought about this matter, but also whether any of these plausible measures were mooted, understanding that the public servants or citizens involved in a program may have had entirely different metrics in mind.

Often the outcomes are not that easy to measure. Nonetheless, we want something more concrete than a personal opinion, a thumbs up or thumbs down. To take one example, suppose the aim of a case study is to trace the impact of cabinet management or cabinet design on “ability of factions to work together.” This outcome is not easy to assess. Certainly, we want to know how people themselves define “ability to work together,” and open-ended questions are initially helpful. Instead of nudging the interviewee’s mind down a particular path, the interviewer allows people to organize their own thoughts.Footnote 4 But a skilled interviewer then engages the speaker to try to get a better sense of what it was about people’s perceptions or behavior that really changed, if anything. In the abstract it is possible to think of several possible measures: how long it took to arrange meetings to coordinate joint initiatives, how often requested meetings actually took place, how often the person interviewed was included in subcabinet deliberations that involved the other political parties, whether the person interviewed felt part of the decision process, whether the deputy minister (always from the other party in this instance) followed through on action items within the prescribed timeframe, whether there was name-calling in the meeting room or fistfights, etc.

An interviewer also wants to figure out whether the theory of change that motivated a policy intervention actually generated the outcomes observed. Again, theory plays a role. It helps to come to an interview with plausible alternative explanations in mind. In the example above, maybe power-sharing had little to do with reducing tension among faction leaders. Instead, war weariness, a shift in public opinion, a sharp expansion of economic opportunity outside government that reduced the desire to remain in government, the collapse of factional differences in the wake of demographic change, the personality of the head of government – any of these things might also have accounted for the results. A skilled interviewer devises questions to identify whether any of these causal dynamics were in play and which facts would help us understand the relative importance of one explanation versus the others.

Let me add a caveat at this point. Theoretically informed interviewing leads us to the kinds of descriptive detail important for analysis and understanding. However, it is also crucial to remember that our initial frameworks, if too narrowly defined, can cause us to lose the added value that interviews can generate. As Albert Reference HirschmanHirschman (1985) noted years ago, paradigms and hypotheses can become becoming a straightjacket (‘confirmation bias’), and the unique contribution of interview-based research is that it can foster a dialogue that corrects misimpressions. Openness to ideas outside the interview script is important for this reason

For example, understanding the source of political will is important in a lot of policy research, but sometimes the most important outcome the lead decision-maker wants to achieve is not the one that most people associated with a policy know about or share. Say we want to use interview-based cases to help identify the conditions that prompt municipal public works programs and other city services to invest in changes that would improve access to early childhood development services. It soon becomes clear that the mayors who had made the most progress in promoting this kind of investment and collaboration sought outcomes that went well beyond boosting children’s preparedness for preschool, the initial supposition, and, moreover, each wanted to achieve something quite distinctive. For some, the larger and longer-term aim was to reduce neighborhood violence, while for others the ambition was to diminish inequality or boost social capital and build trust. The open-ended question “Why was this program important to you?” helps leverage this insight.

Theory and the interview process

. Interviewing employs theory in a second sense as well. To reveal what really happened, we have to weed out the details people have remembered incorrectly while filling in the details some never knew and others didn’t consider important, didn’t want to highlight, or simply forgot. Therefore, in the context of an interview, it is the researcher’s job not only to seek relevant detail about processes, but also to perceive the gaps and silences and use additional follow-up questions or return interviews to secure explanations or elaboration.

In this instance, the researcher navigates through a series of hypotheses about the speaker’s relationship to the issue at hand and knowledge of events. A few of the questions that leverage information for assessing or weighting answers include:

“You had a peripheral role in the early stages of these deliberations/this implementation process, as I understand it. How did you learn about the rationale for these decisions? [Co-workers on the committee? Friends? Briefed by the person who led the committee or kept the minutes? Gleaned this information as you began to participate?] How would you say that joining the deliberation/process/negotiation late colored your view of the issues and shaped your actions, or did it not make much difference?”

“You were involved in a lot of difficult decisions at the time. How closely involved were you in this matter? Did you spend a lot of time on it? Was it an especially high priority for you, or was it just part of your daily work?” “Given all the difficult matters you had to deal with at the time, how greatly did this issue stand out, or is it hard to remember?” (Level of knowledge helps the interviewer weight the account when trying to integrate it with other information.)

“The other people involved in this decision/process/negotiation had strong ties to political factions. At least some of them must have tried to influence you. At what stages and in what form did these kinds of pressures arise?” “Were some voices stronger than others?” “How would you say these lobbying efforts affected your decision/work/stance?”

“As I understand it, you took a decision/action that was unusual/worked against your personal interest/was sure to be unpopular with some important people. How would you characterize your reasons for doing so?”

The information these questions leverage helps the case writer assess the likely accuracy of an account, in at least three ways: First, it helps us understand whether someone was in a position to know or heard about an action secondhand. Second, it helps us assess the integrity of a response – for example, does a statement run contrary to the speaker’s obvious personal interests and is it therefore more believable? Third, it can also help spot purely opportunistic spin: Is the view expressed consistent with the speaker’s other actions and attitudes, or is at odds with these? Can the person offer a clear story about this divergence, or did this perception or preference evolve in association with a promotion, an election, or some other event that may have influenced behavior?

Theory and ability to arbitrate among competing statements.

The third task of interview-based case research is to meld information garnered from different conversations and other types of sources in order to triangulate to the truth. This too is a theory-driven enterprise. Every time there is a clash between two assertions, we ask ourselves the familiar refrain “what could be going on here?” (hypothesis formation, drawn from theory), “how would I know?” (observable measures), and “by what method can I get this information?” (framing a follow-up question, checking a news report, consulting a register, etc.).

We may weigh the account of someone who joined a process late less heavily if it clashes with the information provided by those closer to a process, but it could be that the latecomer is less vulnerable to groupthink, has no reputation at stake, and offers a clearheaded story. Maybe we know the person was brought in as a troubleshooter and carried out a careful review of program data, or that the person is highly ambitious, eager to appear the hero who saved a failing initiative that, in fact, had not performed as badly as stated? Career paths, reputational information, and the written record – for example, longitudinal performance data – can all assist in making sense of disparate accounts.

This thought process may have to take place in the context of an interview as we listen and form follow-up questions, but it can also fuel exit interviews or second conversations designed both to provide another occasion to relate events remembered after the first encounter and to afford a chance to react to divergent information or ideas others may have voiced. This is the task of the exit interview.

To stress that skilled interviewing is theory-driven does not mean social scientists do a better job than journalists. Journalists might call the same kind of thought process “intuition” or “savvy,” but, when asked to step back, be self-conscious, and break down the mental exercise involved, the reality of what they do differs little from how social scientists or historians proceed in their work. The editor who tells a cub reporter, “I smell a rat” upon hearing the sketch of a story is positing an alternative hypothesis to test the adequacy of a description. Employing a general model built on experience, the editor pushes the reporter to use evidence to identify what the people described in the reporter’s draft are really doing.Footnote 5 A reporter’s intuition is equivalent to a social scientist’s skill in quickly framing plausible hypotheses and crafting a follow-up question that will yield the evidence to arbitrate among conflicting accounts – conducting social science inquiry “on the fly.”

Regardless of the interviewer’s own background, skilled interviewing places a premium on preparation. Even if the interviewer does not have a full-blown research design, it is crucial to have a preconversation sketch that frames hypotheses about the subject matter of the case and alternative plausible explanations; specifies the role the interviewee played in these events and the level of knowledge or type of gloss that relationship might produce (or at least does so with as much care as possible at this stage); and summarizes what archival sources say about the story line. This practice helps frame the questions that will tease out the evidence that disconfirms, modifies, or corroborates different versions of a story mid-conversation as new facts and observations emerge.

6.4 Improving Recall and Specificity

Solid, substantive preparation alone does not generate the requisite level of detail and accuracy needed in a policy case study. The skilled interviewer also has to overcome barriers to cognition. The people we interview are busy. They often work in a language different from ours. They may not understand what a study is about and what kinds of information the interviewer seeks. Further, like the rest of us, they forget and they tire. As a result, their answers to questions may vary from one interview to the next, making the descriptions we assemble less reliable.

Survey researchers have struggled with these challenges for decades.Footnote 6 They have investigated how people answer questions and how to improve accuracy in responses. Their reflections are helpful for those who do qualitative interviews.

1. One fairly obvious starting point or maxim is to make sure that the interviewee understands the purpose of the project or study and can perceive the level of detail expected. It is common for someone to ask quizzically, “Why would anyone be interested in what I did?”

Helping a speaker understand the intended audience improves motivation and accuracy. With respect to policy-focused interviews, asking someone to help a peer learn from a program’s experience usually changes an interviewee’s mental stance, and enables the person to hone in on the kind of subject matter sought and the level of operational detail needed. In the Princeton program we often used the phrase, “The purpose is to help your counterparts in other countries learn from your experience” in the invitation letter and follow-up, as well as in the lead-in to the interview itself. We also emphasized that “the aim of the case study is to profile the reform you helped design, the steps you took to implement the new system, and the results you have observed so that others can learn from you.” Periodically, we reiterated these points. When an interviewee can imagine a conversation with the person who will use the information, answers are more likely to be specific. It also becomes easier to induce someone to be compassionate and speak honestly about the real problems that arose during a process, so that the target group of readers don’t go astray or fail to benefit from the experience.

2. A second maxim is to ensure questions are clear so the interviewee does not have to struggle with meaning. A long, rambling question that requires energy to parse can sink an interview. By contrast, a simple, open-ended “grand tour” question is often a good place to begin, because many people are natural storytellers, become engaged, and start to focus their comments themselves when given this latitude. In his ethnographic interview classic, for example, Spradely suggests asking “Could you describe what happened that day?” or “Could you tell me how this office works?” Subsequent questions can focus on the elements of special relevance to the subject and may include prompts to reach specific subject matter or the requisite level of detail.Footnote 7

3. In framing questions, we try to avoid ambiguous or culturally loaded terms that increase the amount of mental calculation an answer requires.Footnote 8 How much is “usually” or “regularly”? “Big”? How many years is “young” or “recently”? It may be better to ask, “About how often did that happen during that year?” or “How many times did that happen that year?” Novice interviewers often refer to seasons as they pinpoint the time of an action, but of course these vary globally, so the references merely confuse (moral: benchmark to events or national holidays).

Similarly, we try to eliminate questions that require the interviewee to talk about two different things – the “double-barreled question” or compound question. “Did that step reduce error?” is clear, but “Did that process reduce error and delay?” asks about two dimensions that may not be related, yet it seems to require one answer. In this instance, it does not take much effort to sort out the two dimensions and in an interview context, as opposed to a survey, that is feasible. However, a speaker will have a slightly tougher time with a compound question about a preference, motivation, or interaction: “Was the main challenge to compensate those who would have to alter their farming practices and to help the community monitor illegal deforestation?” “Was this group an obstacle to winning the vote in the legislature and a source of public backlash?” Simple questions and quick follow-ups usually elicit better information than complex questions that ask for views on two or more things at once.

4. The passage of time influences the ability to remember information and potentially also makes it hard to check the reliability of a description. In the 1980s, studies of physician recall found that memory of specific patient visits decayed very rapidly, within two weeks of a visit.Footnote 9 Norma Bradburn and her colleagues reported that about 20 percent of critical details are irretrievable by interviewees after a year and 60 percent are irretrievable after 5 years.Footnote 10 The ability to remember distant events interacts with the salience or importance of the events to the interviewee and with social desirability. A well-received achievement that occurred two years earlier may be easier to remember than something that did not work very well or was not considered important at the time. Using “probes,” or questions that fill in a little detail from archival research, can help break the mental logjam.

Phrasing that takes the interviewee carefully back in time and provides reminders of the events that occurred or the locations in which they occurred may improve recall. Specific dates rarely have the same effect (imagine trying to remember what you were doing in August three years ago). Recall can improve during the course of an interview or after the interviewer has left.

The passage of time may also alter perceptions. Views change, and the interviewee may subconsciously try to harmonize interests, attitudes, or opinions. As in a historical account, what the principal actors knew at the time they recognized a problem and decided what to do is very important to capture accurately, and it may take some extra effort to trigger memory of initial perceptions and how these changed. Here is an example from a series of cases on the 2014 West Africa Ebola Outbreak Response.Footnote 11

Example: Effects of time on accuracy (two interviews conducted in late 2015 about the Ebola response):

Interview 1: Question: “How useful was the US military response to improving logistics capability?” “The US timing was all wrong. The military built emergency treatment centers that were never used because the epidemic ended by the time the centers were ready. The US military action was irrelevant.”

Interview 2: Question: “Let’s go back to August and September 2014 when the outbreak escalated dramatically in Liberia. Could you talk about the impact of the US military on logistics?” “In September 2014, the models said the number of people infected would rise to over a million. The US military prepared for that eventuality. Later the epidemic declined and the ETUs [emergency treatment units] weren’t used, but in the end what seemed to matter to the public was the visible sign that a big power cared, which generated a psychological boost. We hoped the military would be more useful in moving lab materials around but they had instructions not to enter areas where an outbreak had occurred so they just dropped us at the edges of these areas and then we made our way from there.”

There is some truth to both statements but the timestamp in the second question elicited a more complete answer that helped resolve tensions among accounts.

5. Memory of actions taken in a crisis atmosphere, when people may have worked intensely on many different fronts, tends to be less good, emerges in a highly fragmented form with high levels of error, or acquires a gloss. Said one ISS interviewee who had worked intensely on a disaster response, “As we talk, I can feel PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] coming back.” Words tumbled out, and the interviewer had to piece together the order in which actions occurred.

In these circumstances, it is helpful to plan one or more return interviews. Between sessions, people will tend to remember more, though their memories may also start to embellish or spin the account. Questions that contain specific information about the circumstances and ask for a reaction may help alleviate that problem. For the researcher, the challenge then becomes integrating the different versions of an event to ensure that they synchronize accurately.

6. Research on how respondents react to surveys suggests that question order can make a big difference in the responses people offer.Footnote 12 Although there is not parallel research on long-form qualitative interviews, it stands to reason that some of the same issues arise in this slightly different context, although it is easier for the interviewer to circle back and ask for views a second time than it might be in a survey, providing a possible corrective.

In designing and modifying the informal script that structures the interviews, it may help to consider how the sequence or juxtaposition of particular questions might influence what people say by inadvertently priming a particular response. For example, if one question focuses attention on the influence an interest group brought to bear on a decision, the answer to an unrelated question may place heavier emphasis on interest groups than it would have in a different question lineup. Sometimes the best cure for this type of spillover is to acknowledge it directly: “We have talked a lot about interest group influence. I want to change the topic and focus on ____, now. Although there may have been some interest group influence, most likely other things were important too, so I encourage you to step back and think about what shaped this decision, more broadly.” An alternative is to shift to a different, more minor topic – or recommend a brief break – before returning to the line of questioning.

In policy research, political or social sensitivity may lead to self-censorship. To lessen this response, while also respecting the risks a speaker faces, it is sometimes possible to sequence questions so that they enable the speaker to articulate a problem in a diplomatic way, threading the needle: “I imagine that people who had invested in that land were upset that the city wanted to build a road there. Did any of those people ever speak about this problem in public? Did any of them ever come here to express their views? I see in the newspapers that politician X owned some land in that area – was he part of the group that objected? Did the program change after this point?”

Pacing sensitive questions may necessitate extra care in order to prevent the interviewee from calling an end to the conversation or from shifting to highly abbreviated responses. If the point of an interview is to acquire information about a particular stage of a negotiation, then it may be better to proceed to that point in the conversation before posing sensitive questions about earlier matters – and then loop back to these other sensitive issues when asking about results or reflections toward the conclusion of the conversation. By that point the interviewer has had a chance to build credibility and signal facility with some of the technical details, making it more likely the speaker feels s/he has had a fair chance to explain actions and views, while also realizing the interviewer is unlikely to be satisfied with a stock answer. Ethics rules that require returning to the speaker for permission to use quotes or identifying information can also assist willingness to speak, provided the speaker trusts that the interviewer will indeed live up to this commitment. (Note that this research ethics commitment runs counter to the standards in journalism, where the emphasis is on conveying publicly important information in real time and not allowing the holders of that information to act as censors.)

Ending on a more positive note is also helpful, both for the well-being of the interviewee and for maintaining the goodwill that makes it possible to return to the conversation later: “You accomplished __, ___, and ____. When you think back on this episode are there other things that make you especially proud/happy/satisfied with the work/____?”

7. Offer the right kinds of rewards. Because it takes a lot of mental energy to respond to questions and because there is no immediate tangible reward, an interview has to generate and sustain motivation. Usually, helping someone understand the important purpose and specific focus increases interest. Most people also want some sense that they are responding with useful information. If they don’t have this sense, they will drop out.

There is a fine line between leading, on the one hand, and nondirective feedback that merely sustains a conversation. A leading question suggests correct answers or reveals the researcher’s point of view. This type of feedback reduces accuracy. By contrast, there are neutral forms of feedback that can motivate and lead the interviewee to persist in answering questions. Reference Cannell, Miller, Oksenberg and LeinhardtCannell, Miller, and Oksenberg (1981: 409–411) suggest a set of four responses that ISS has also found helpful:

“Thanks, that’s useful, OK.”

“I see. This is the kind of information we want.”

“Thanks, you have mentioned ___ things …”

“Thanks, we are interested in details like these …”

Speakers often model the length of their responses on the interviewer’s behavior. Rewarding specificity in a response to an open-ended question early in the interview with “Thanks, we are interested in details like these” can send the right signal (assuming detail is in fact what we want).

6.5 Integrating Streams of Evidence, Arbitrating Differences

In survey research, social scientists aggregate data from multiple respondents by analyzing central tendencies, assessing variance, and then evaluating the influence of causal factors on responses to questions using some type of regression analysis. Although less concerned with central tendencies and average effects, qualitative case study research also has to integrate multiple streams of information from interviews – information about views as well as processes. This stage of the research can catch and reconcile discrepancies or spin, but it can also become a source of error if the researcher incorrectly judges one account to be more truthful than another, with little basis in fact or little transparency about the reasons for privileging a particular point of view.

Arbitrating among conflicting streams of evidence takes place in journalism every day, and the adages journalists follow are equally applicable in social science research. Editors and reporters term the failure to resolve a contradiction or a clash of perspectives as “he said, she said” journalism.Footnote 13 Columbia University journalism professor Jay Rosen, who led the charge against “he said, she said” reporting, offered an illustration. In this instance, a US National Public Radio reporter described a controversy over new reproductive health regulations and said that one group portrayed the rules as “common sense” while another saw them as designed to drive clinics out of business. The reporter laid out each group’s claims and moved on. Rosen cried foul and said the reporter had an obligation to offer a more complete description that gave the reader some sense of the evidence underlying the seemingly disparate claims. This imperative has grown stronger as quality journalism has tried to combat disinformation.

Rosen’s remedies were exactly those his social science counterparts would have offered: hypothesis formation, measurement, and follow-up questions. In this instance, Rosen said, the reporter could have compared the new regulations to those already in place for similar procedures in the same state and to regulations in other jurisdictions so the reader could see whether the claim that the new rules were “common sense” had some basis in fact. The reporter could have read the safety report to see whether the accident or infection rates were especially high compared to related procedures. In short, Rosen argues, the researcher’s obligation to the reader is to resolve discrepancies when they involve matters that affect the reader’s ability to make a judgment about the core subject matter of the case. The reader’s mind should not buzz with further questions, and the description must have all the components necessary to understand the intervention described, including those an expert would consider fundamental.

Discrepancies in streams of interview evidence can arise from many sources, including differences regarding when two people became involved in a process, the roles they played and the knowledge available to them in each of these roles, and the life experiences or technical skills they brought to the job. That is, disagreements do not always arise from deliberate spin. Here are three examples of descriptive or reporting challenges drawn from ISS case study research and the intellectual process these challenges triggered.

One: Superficially discrepant timelines (case about the Liberian Ebola Outbreak response coordinationFootnote 14):

Question: When did Liberia adopt an incident management system for responding to the Ebola outbreak?

Interview 1: CDC Director Tom Frieden persuaded President Ellen Sirleaf to support an incident management system for coordinating the Ebola response. (From archival record: This meeting took place on or around August 24, 2014, on Frieden’s visit to the country.)

Interview 2: A CDC team visited Monrovia the third week in July 2014 and began to work with officials to set up an incident management system. (From archival record: The president appointed Tolbert Nyenswah head of the incident management system on August 10.)

Thought Process: The interviewer seeks accuracy in describing a sequence of events. At first blush it might seem that one subject just remembered a date incorrectly, but the archival evidence suggests that the dates of the events cited are indeed different. What else could be going on? One hypothesis is that something happened in between the two periods that required the president to revisit the choice of approach. An interviewer in strong command of the timeline might then frame a follow-up for interviewee 1: “Could you clarify the situation for me? I thought that the president had earlier appointed someone to head an incident management system. Did the first effort to launch the system fail or flounder?” For interviewee 2: “I understand that later the president and the head of the CDC discussed whether to continue the system in late August. Did anything happen in mid-August to shake the president’s confidence that the IMS was the right approach?”

Two: Superficially discrepant information about states of mind or relationships: (case on cabinet coordination in a power-sharing governmentFootnote 15)

Interview 1 (with someone who was in the meeting): “The dialogue process helped resolve stalemates and we emerged from these sessions in a better position to work together.”

Interview 2 (with a knowledgeable observer who was not in the meeting): “The dialogue process just helped the parties delay taking steps to meet the goals they had jointly agreed to. The leaders argued for long periods.”

Thought Process: In this instance, the researcher wants to know whether tensions among political parties in a unity government were lower, about the same, or higher after resort to an externally mediated “dialogue” mechanism. There are three challenges. First, few people were in the room and the perceptions may vary with knowledge. Second, “tension” or “trust” among political parties is something that is “latent” or hard to measure. Third, delay and levels of distrust could be related in a wide variety of ways. Delay might have increased trust or decreased it.

In this instance, the researcher would likely have to return to the people interviewed with follow-up questions. One might venture several hypotheses and ask what evidence would allow us to rule out each one, then frame questions accordingly. Did the number of matters referred to mediation go down over time? Did the number of days of mediation required diminish over time? Did deputy ministers perceive that it became easier or harder to work with colleagues from the other party during this period? Did progress toward pre-agreed priorities stall or proceed during this period?

If what went on in the mediation room is confidential, then the researcher has to frame questions that rely on other types of information: “Comparing the period before the mediation with the weeks after the mediation, would you say that you had more purely social conversations with people in the opposite party, fewer, or about the same? Was there a new practice introduced after the mediation that affected your ability to have these conversations?”

Three: Insufficient detail; “the mind does not come to rest” and the reader is left with an obvious, big, unanswered question. This challenge arises frequently. For example, the Princeton ISS program ran into this issue in trying to document the introduction of a public service delivery tracking system in the Dominican Republic.Footnote 16

Interview 1 (with an officer responsible for tracking action items in a ministry): “At first we added data to the tracking system each month but after a few months everything slowed down and we added information only every three or four months.”

Interview 2 (with an officer responsible for overseeing the central recording process): “Some ministries didn’t report at all. They never added information to the tracking system.”

Thought process: There is a discrepancy between the two statements, but in both instances it is clear that work had ground to a halt. The issue is when and why. Was the new system unworkable in all ministries or just some? Further, was the system impossible for most to use, or was there something else going on? One could ask a general question, “Why did that happen?” – an approach that often yields surprising answers. But hypotheses and follow-ups might also help winnow out plausible from less-plausible explanations. Did a few ministries try to report and then give up and join the others in noncompliance, or did a few continue to report? Then to the rationale: Was there no progress to report? Was there no penalty for not reporting? Was it hard to find the time to file the report? Did the software break down, or was there limited electrical power to run the system? Was someone designated to acquire and upload the information, or was no one really in charge of that function? Were the instructions hard to follow? Did the minister care or say anything when reporting slowed or halted? Did anyone from the president’s office/delivery unit call to ask why the report was slow? Was there pressure to delay the reports? Why?

If there are no data available to resolve a contradiction or settle a logical subsidiary question, then the researcher can say so. Andrew Bennett has proposed valuing evidence from different interviews according to kind of schedule of plausibility.Footnote 17 Attach an estimate or “prior” to the possible motives of each interviewee who provides evidence and weigh the evidence provided accordingly. If someone offers evidence that clearly does not make that person “look good,” one might have more confidence in the other information offered. “Social psychologists have long noted that audiences find an individual more convincing when that person espouses a view that is seemingly contrary to his or her instrumental goals,” Bennett suggests; “For similar reasons, researchers should follow established advice on considering issues of context and authorship in assessing evidence. Spontaneous statements have a different evidentiary status from prepared remarks. Public statements have a different evidentiary status from private ones or from those that will remain classified for a period of time.”

6.6 Selection Bias

The protocols used to select interviewees are always a potential source of error, whether in survey research or in qualitative interviewing. In process-tracing case studies, we choose the people to interview instrumentally. That is, we want information from people who have direct knowledge of a process. But there is a consequent risk of interviewing only people from a single political party; from the group tasked with the daily work of carrying out a program; or from one ethnic, religious, or economic group affected. This problem may not always be damning. It may be partly contingent on the question asked: for example, there may be circumstances when the only people who are in a position to know about a series of actions are indeed people from the same small group. However, if the aim is to know how others perceived a decision or a program, or whether people thought a process was representative – or whether beneficiaries viewed the program in the same way policy-makers did – it goes without saying that we need the views of a broader group of people.

Avoiding selection bias in interview-based research can prove challenging, especially in less open societies. At ISS, which has focused on governmental reform, researchers typically spend much of their time securing an accurate description of a change in structure or practice and its implementation. Usually the only people with that information are those in government who actually carried out the daily legwork. In some settings, these people are likely to have a party affiliation and come only from one political party. They also may not know how the “clients” – the country’s citizens – view what they do. Because of this, the research program made it standard practice to include in its interview lists:

people most likely to be critical of the reforms we profile (we try to identify such people by looking at local newspaper editorials and headlines, speaking on background with journalists, etc.)

counterparts from another political party where these exist (predecessors in the same role, for example)

civic leaders or university researchers who work closely with the intended beneficiaries or clients

public servants who worked on the project in different locations

the “victors” and the “vanquished” – the people whose views prevailed and those whose views did not.

Where there are few civic groups it may be particularly difficult to identify people who are close to the views of clients and users and can generalize reliably about perceptions and experiences.

Problem: Critics won’t speak (case study on extension of civilian oversight of the military)

Interview 1: The defense minister in the political party that recently came to power says, “We retrenched several thousand soldiers and gave them severance pay. There was no serious objection to the new policy. Some of the senior military officers believed the policy was the right thing to do and supported it.”

Missing Interview: From archival sources we know that a political party led a protest against this very policy. Neither the officers of that political party nor the identifiable leaders of the protest assented to an interview, however.

Remedy: There are some partial solutions for countering selection bias that arises from this sort of “missing actor” problem. One is to try to induce people who will speak on the record to be self-reflective. For example, Jeffrey Berry suggests that the researcher “ask the subject to critique his own case – Why aren’t Democrats buying this?” or to say, “I’m confused on one point; I read ….”Footnote 18 Another approach is to draw on the publications the critics have authored. These may not get at the real reasons for the criticisms the groups raise, but they may provide enough information to represent the view, and enough detail for the researcher to use to seek a reaction from those who will go on the record.

Another kind of selection bias can arise in new democracies or more authoritarian political systems: self-censorship. In this situation, because of concerns about vulnerability or because of traditions that discourage openly critical comments, everyone interviewed offers a “careful” or biased response. The question is how to break through the reserve without jeopardizing any participant’s safety. One possibility is to identify fractures within the political party – a committee or wing or leadership group that genuinely wants to know how well something works and is willing to talk about suspected problems. We can then use these to frame questions that don’t require an interviewee to criticize but instead just ask for steps taken when X happened. Phrasing questions so that they don’t force one person to impugn another can also help: “If you had to do this over again, what would you do differently?” “If you could advise your counterpart in another country how to do _____, what special advice or tips would you want to convey?”

The act of “getting in the door” can create selection bias problems too.Footnote 19 The first people to respond favorably to requests to interviews may be people who are distinctive in some way – those who feel empowered, younger people, people who have aspirations in electoral politics and see a way to lend some credibility to their campaigns. To guard against this kind of bias, it is important to step back periodically and to ensure that the list of those who responded favorably to interview invitations includes people who were involved with what we seek to document but don’t have the same profile as others.

6.7 Conclusion

Qualitative case studies are a form of empirical research. Facts are the currency in which they trade. As such they are potentially vulnerable to the same kinds of problems that bedevil quantitative research, from low measurement validity to data collection techniques that bias the views or accounts surveyed or introduce error. This chapter offers a schema for thinking about these challenges in the context of preparing interview-based process-tracing case studies, along with a few partial solutions to some common problems.

One implication of the observations offered here is that careful interview preparation yields a high return with respect to the accuracy and completeness of a process-tracing case study. That means 1) knowing the subject well enough to frame thoughtful hypotheses and measures in advance, and to build these into draft questions; 2) establishing a timeline and “prestory” from news sources, operations reports, or preliminary “informant” interviews; 3) learning about the backgrounds of the people central to the policy initiative; 4) identifying representatives of the beneficiary groups as well as likely critics or people who had special vantage points; and 5) understanding options tried in other, similar settings or in other periods. This background preparation then shapes the development of interview scripts, useful for thinking hard about clarity, narrative flow, question sequence, and other matters that impinge on the quality of the information elicited. Although the interview itself is a conversation, not (usually) a series of survey questions read off a schedule, the development of the written script sharpens the interviewer’s ability to elicit the information required, while maintaining a positive rapport with the speaker.

A second implication is that we have to be transparent about the basis for arbitrating differences that emerge across interviews. Sometimes the prose can say what the reader needs to know: “Staff members involved at the beginning of the project, when the initial pilot failed, remembered that ____. But those who joined later, after the first results of the revised program started to emerge and neighborhood resistance had dissipated, had a different view of the challenges the government faced.” In other instances, a discursive footnote of the sort that Andrew Moravcsik (Chapter 8, this volume) proposes may be the best way to help the reader understand the judgments the author made.

A third implication of this analysis is that the purported differences in ability to rely on quantitatively analyzed survey data, on the one hand, and qualitative interview data, on the other, are vastly overstated. The main difference between the two has more to do with whether frequencies or distribution of perspectives across populations matter to the aim of the project. If they do, then survey data may have greater value. But if the aim is to elicit understanding of strategic interaction or a process, then purposive interviewing will tell us more. In both contexts, however, the same concerns about eliciting accurate responses apply and some of the same remedies prove useful.

7.1 Introduction

In the lead article of the first issue of Comparative politics, Harold Lasswell posited that the “scientific approach” and the “comparative method” are one and the same (Reference LasswellLasswell 1968: 3). So important is comparative case study research to the modern social sciences that two disciplinary subfields – comparative politics in political science and comparative-historical sociology – crystallized in no small part because of their shared use of comparative case study research (Reference Collier and FinifterCollier 1993; Reference Adams, Clemens, Orloff, Adams, Clemens and OrloffAdams, Clemens, and Orloff 2005: 22–26; Reference Mahoney and ThelenMahoney and Thelen 2015). As a result, a first-principles methodological debate emerged about the appropriate ways to select cases for causal inquiry. In particular, the diffusion of econometric methods in the social sciences exposed case study researchers to allegations that they were “selecting on the dependent variable” and that “selection bias” would hamper the “answers they get” (Reference GeddesGeddes 1990). Lest they be pushed to randomly select cases or turn to statistical and experimental approaches, case study researchers had to develop a set of persuasive analytic tools for their enterprise.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that there has been a profusion of scholarship discussing case selection over the years.Footnote 1 Reference Gerring and CojocaruGerring and Cojocaru (2015) synthesize this literature by deriving no less than five distinct types (representative, anomalous, most-similar, crucial, and most-different) and eighteen subtypes of cases, each with its own logic of case selection. It falls outside the scope of this chapter to provide a descriptive overview of each approach to case selection. Rather, the purpose of the present inquiry is to place the literature on case selection in constructive dialogue with the equally lively and burgeoning body of scholarship on process tracing (Reference George and BennettGeorge and Bennett 2005; Reference Brady and CollierBrady and Collier 2010; Reference Beach and PedersenBeach and Pedersen 2013; Reference Bennett and CheckelBennett and Checkel 2015). I ask a simple question: Should our evolving understanding of causation and our toolkit for case-based causal inference courtesy of process-tracing scholars alter how scholars approach case selection? If so, why, and what may be the most fruitful paths forward?

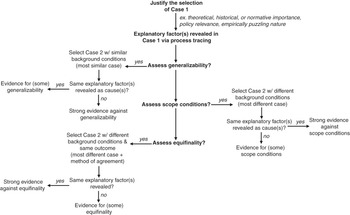

To propose an answer, this chapter focuses on perhaps the most influential and widely used means to conduct qualitative research involving two or more cases: Mill’s methods of agreement and difference. Also known as the “most-different systems/cases” and “most-similar systems/cases” designs, these strategies have not escaped challenge – although, as we will see, many of these critiques were fallaciously premised on case study research serving as a weaker analogue to econometric analysis. Here, I take a different approach: I argue that the traditional use of Millian methods of case selection can indeed be flawed, but rather because it risks treating cases as static units to be synchronically compared rather than as social processes unfolding over time. As a result, Millian methods risk prematurely rejecting and otherwise overlooking (1) ordered causal processes, (2) paced causal processes, and (3) equifinality, or the presence of multiple pathways that produce the same outcome. While qualitative methodologists have stressed the importance of these processual dynamics, they have been less attentive to how these factors may problematize pairing Millian methods of case selection with within-case process tracing (e.g., Reference Hall, Mahoney and RueschemeyerHall 2003; Reference TarrowTarrow 2010; Reference Falleti, Mahoney, Mahoney and ThelenFalleti and Mahoney 2015). This chapter begins to fill that gap.

Taking a more constructive and prescriptive turn, the chapter provides a set of recommendations for ensuring the alignment of Millian methods of case selection with within-case sequential analysis. It begins by outlining how the deductive use of processualist theories can help reformulate Millian case selection designs to accommodate ordered and paced processes (but not equifinal processes). More originally, the chapter concludes by proposing a new, alternative approach to comparative case study research: the method of inductive case selection. By making use of Millian methods to select cases for comparison after a causal process has been identified within a particular case, the method of inductive case selection enables researchers to assess (1) the generalizability of the causal sequences, (2) the logics of scope conditions on the causal argument, and (3) the presence of equifinal pathways to the same outcome. In so doing, scholars can convert the weaknesses of Millian approaches into strengths and better align comparative case study research with the advances of processualist researchers.

Organizationally, the chapter proceeds as follows. Section 7.2 provides an overview of Millian methods for case selection and articulates how the literature on process tracing fits within debates about the utility and shortcomings of the comparative method. Section 7.3 articulates why the traditional use of Millian methods risks blinding the researcher to ordered, paced, and equifinal causal processes, and describes how deductive, processualist theorizing helps attenuate some of these risks. Section 7.4 develops a new inductive method of case selection and provides a number of concrete examples from development practice to illustrate how it can be used by scholars and policy practitioners alike. Section 7.5 concludes.

7.2 Case Selection in Comparative Research

7.2.1 Case Selection Before the Processual Turn

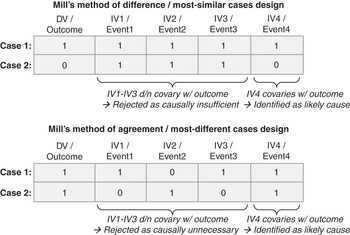

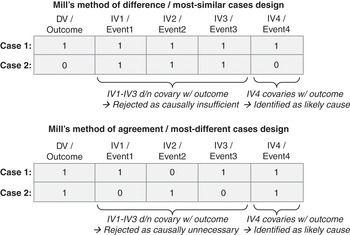

Before “process tracing” entered the lexicon of social scientists, the dominant case selection strategy in case study research sought to maximize causal leverage via comparison, particularly via the “methods of agreement and difference” of John Stuart Reference MillMill (1843 [1974]: 388–391).

In Mill’s method of difference, the researcher purposively chooses two (or more) cases that experience different outcomes, despite otherwise being very similar on a number of relevant dimensions. Put differently, the researcher seeks to maximize variation in the outcome variable while minimizing variation amongst a set of plausible explanatory variables. It is for this reason that the approach also came to be referred to as the ‘most-similar systems’ or ‘most-similar cases’ design – while Mill’s nomenclature highlights variation in the outcome of interest, the alternative terminology highlights minimal variation amongst a set of possible explanatory factors. The underlying logic of this case selection strategy is that because the cases are so similar, the researcher can subsequently probe for the explanatory factor that actually does exhibit cross-case variation and isolate it as a likely cause.

Mill’s method of agreement is the mirror image of the method of difference. Here, the researcher chooses two (or more) cases that experience similar outcomes despite being very different on a number of relevant dimensions. That is, the researcher seeks to minimize variation in the outcome variable while maximizing variation amongst a set of plausible explanatory variables. An alternative, independent variable-focused terminology for this approach was developed – the ‘most-different systems’ or ‘most-different cases’ design – breeding some confusion. The underlying logic of this case selection strategy is that it helps the researcher isolate the explanatory factor that is similar across the otherwise different cases as a likely cause.Footnote 2

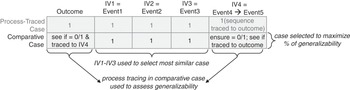

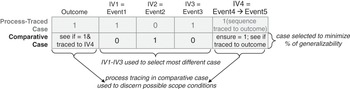

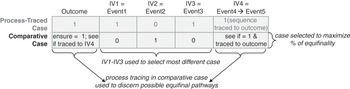

Figure 7.1 Case selection setup under Mill’s methods of difference and agreement

Mill himself did not believe that such methods could yield causal inferences outside of the physical sciences (Reference MillMill 1843 [1974]: 452). Nevertheless, in the 1970s a number of comparative social scientists endorsed Millian methods as the cornerstones of the comparative method. For example, Reference Przeworski and TeunePrzeworski and Teune (1970) advocated in favor of the most-different cases design, whereas Reference LijphartLijphart (1971) favored the most-similar cases approach. In so doing, scholars sought case selection techniques that would be as analogous as possible to regression analysis: focused on controlling for independent variables across cases, maximizing covariation between the outcome and a plausible explanatory variable, and treating cases as a qualitative equivalent to a row of dataset observations. It is not difficult to see why this contributed to the view that case study research serves as the “inherently flawed” version of econometrics (Reference Adams, Clemens, Orloff, Adams, Clemens and OrloffAdams, Clemens, and Orloff 2005: 25; Reference TarrowTarrow 2010). Indeed, despite his prominence as a case study researcher, Reference LijphartLijphart (1975: 165; Reference Lijphart1971: 685) concluded that “because the comparative method must be considered the weaker method,” then “if at all possible one should generally use the statistical (or perhaps even the experimental) method instead.” As Reference Hall, Mahoney and RueschemeyerHall (2003: 380; 396) brilliantly notes, case study research

was deeply influenced by [Lijphart’s] framing of it … [where] the only important observations to be drawn from the cases are taken on the values of the dependent variable and a few explanatory variables … From this perspective, because the number of pertinent observations available from small-N comparison is seriously limited, the analyst lacks the degrees of freedom to consider more than a few explanatory variables, and the value of small-N comparison for causal inference seems distinctly limited.

In other words, the predominant case selection approach through the 1990s sought to do its best to reproduce a regression framework in a small-N setting – hence Lijphart’s concern with the “many variables, small number of cases” problem, which he argued could only be partially mitigated if, inter alia, the researcher increases the number of cases and decreases the number of variables across said cases (Reference Lijphart1971: 685–686). Later works embraced Lijphart’s formulation of the problem even as they sought to address it: for example, Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and PolsbyEckstein (1975: 85) argued that a “case” could actually be comprised of many “cases” if the unit of analysis shifted from being, say, the electoral system to, say, the voter. Predictably, such interventions invited retorts: Reference LiebersonLieberson (1994), for example, claimed that Millian methods’ inability to accommodate probabilistic causation,Footnote 3 interaction effects, and multivariate analysis would remain fatal flaws.

7.2.2 Enter Process Tracing

It is in this light that ‘process tracing’ – a term first used by Reference HobarthHobarth (1972) but popularized by Reference George and LaurenGeorge (1979) and particularly Reference George and BennettGeorge and Bennett (2005), Reference Brady and CollierBrady and Collier (2010), Reference Beach and PedersenBeach and Pedersen (2013), and Reference Bennett and CheckelBennett and Checkel (2015) – proved revolutionary for the ways in which social scientists conceive of case study research. Cases have gradually been reconceptualized not as dataset observations but as concatenations of concrete historical events that produce a specific outcome (Reference MahoneyGoertz and Mahoney 2012). That is, cases are increasingly treated as social processes, where a process is defined as “a particular type of sequence in which the temporally ordered events belong to a single coherent pattern of activity” (Reference Falleti, Mahoney, Mahoney and ThelenFalleti and Mahoney 2015: 214). Although there exist multiple distinct conceptions of process tracing – from Bayesian approaches (Reference Bennett, Bennett and CheckelBennett 2015) to set-theoretic approaches (Reference Mahoney, Kimball and KoivuMahoney et al. 2009) to mechanistic approaches (Reference Beach and PedersenBeach and Pedersen 2013) to sequentialist approaches (Reference Falleti, Mahoney, Mahoney and ThelenFalleti and Mahoney 2015) – their overall esprit is the same: reconstructing the sequence of events and interlinking causal logics that produce an outcome – isolating the ‘causes of effects’ – rather than probing a variable’s mean impact across cases via an ‘effects of causes’ approach.Footnote 4

For this intellectual shift to occur, processualist social scientists had to show how a number of assumptions underlying Millian comparative methods – as well as frequentist approaches more generally – are usually inappropriate for case study research. For example, the correlational approach endorsed by Reference Przeworski and TeunePrzeworski and Teune (1970), Reference LijphartLijphart (1971), and Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and PolsbyEckstein (1975) treats observational units as homogeneous and independent (Reference Hall, Mahoney and RueschemeyerHall 2003: 382; Reference MahoneyGoertz and Mahoney 2012). Unit homogeneity means that “different units are presumed to be fully identical to each other in all relevant respects except for the values of the main independent variable,” such that each observation contributes equally to the confidence we have in the accuracy and magnitude of our causal estimates (Reference Brady and CollierBrady and Collier 2010: 41–42). Given this assumption, more observations are better – hence, Reference LijphartLijphart (1971)’s dictum to “increase the number of cases” and, in its more recent variant, to “increase the number of observations” (Reference King, Keohane and VerbaKing, Keohane, and Verba 1994: 208–230). By independence, we mean that “for each observation, the value of a particular variable is not influenced by its value in other observations”; thus, each observation contributes “new information about the phenomenon in question” (Reference Brady and CollierBrady and Collier 2010: 43).

By contrast, practitioners of process tracing have shown that treating cases as social processes implies that case study observations are often interdependent and derived from heterogeneous units (Reference MahoneyGoertz and Mahoney 2012). Unit heterogeneity means that not all historical events, and the observable evidence they generate, are created equal. Hence, some observations may better enable the reconstruction of a causal process because they are more proximate to the central events under study. Correlatively, this is why historians accord greater ‘weight’ to primary than to secondary sources, and why primary sources concerning actors central to a key event are more important than those for peripheral figures (Reference TrachtenbergTrachtenberg 2009; Reference TanseyTansey 2007). In short, while process tracing may yield a bounty of observable evidence, we seek not to necessarily increase the number, but rather the quality, of observations. Finally, by interdependence we mean that because time is “fateful” (Reference SewellSewell 2005: 6), antecedent events in a sequence may influence subsequent events. This “fatefulness” has multiple sources. For instance, historical institutionalists have shown how social processes can exhibit path dependencies where the outcome of interest becomes a central driver of its own reproduction (Reference PiersonPierson 1996; Reference PiersonPierson 2000; Reference MahoneyMahoney 2000; Reference Hall, Mahoney and RueschemeyerHall 2003; Reference Falleti, Mahoney, Mahoney and ThelenFalleti and Mahoney 2015). At the individual level, processual sociologists have noted that causation in the social world is rarely a matter of one billiard ball hitting another, as in Reference HumeHume’s (1738 [2003]) frequentist concept of “constant conjunction.” Rather, it hinges upon actors endowed with memory, such that the micro-foundations of social causation rest on individuals aware of their own historicality (Reference SewellSewell 2005; Reference AbbottAbbott 2001; Reference Abbott2016).

At its core, eschewing the independence and unit homogeneity assumptions simply means situating case study evidence within its spatiotemporal context (Reference Hall, Mahoney and RueschemeyerHall 2003; Reference Falleti and LynchFalleti and Lynch 2009). This commitment is showcased by the language which process-sensitive case study researchers use when making causal inferences. First, rather than relating ‘independent variables’ to ‘dependent variables’, they often privilege the contextualizing language of relating ‘events’ to ‘outcomes’ (Reference Falleti, Mahoney, Mahoney and ThelenFalleti and Mahoney 2015). Second, they prefer to speak not of ‘dataset observations’ evocative of cross-sectional analysis, but of ‘causal process observations’ evocative of sequential analysis (Reference Brady and CollierBrady and Collier 2010; Reference MahoneyGoertz and Mahoney 2012). Third, they may substitute the language of ‘causal inference via concatenation’ – a terminology implying that unobservable causal mechanisms are embedded within a sequence of observable events – for that of ‘causal inference via correlation’, evocative of the frequentist billiard-ball analogy (Reference Waldner and KincaidWaldner 2012: 68). The result is that case study research is increasingly hailed as a “distinctive approach that offers a much richer set of observations, especially about causal processes, than statistical analyses normally allow” (Reference Hall, Mahoney and RueschemeyerHall 2003: 397).

7.3 Threats to Processual Inference and the Role of Theory

While scholars have shown how process-tracing methods have reconceived the utility of case studies for causal inference, there remains some ambiguity about the implications for case selection, particularly using Millian methods. While several works have touched upon this theme (e.g., Reference Hall, Mahoney and RueschemeyerHall 2003; Reference George and BennettGeorge and Bennett 2005; Reference LevyLevy 2008; Reference TarrowTarrow 2010), the contribution that most explicitly wrestles with this topic is Reference Falleti, Mahoney, Mahoney and ThelenFalleti and Mahoney (2015), who acknowledge that “the application of Millian methods for sequential arguments has not been systematically explored, although we believe it is commonly used in practice” (Reference Falleti, Mahoney, Mahoney and ThelenFalleti and Mahoney 2015: 226). Falleti and Mahoney argue that process tracing can remedy the weaknesses of Millian approaches: “When used in isolation, the methods of agreement and difference are weak instruments for small-N causal inference … small-N researchers thus normally must combine Millian methods with process tracing or other within-case methods to make a positive case for causality” (Reference Falleti, Mahoney, Mahoney and Thelen2015: 225–226). Their optimism about the synergy between Millian methods and process tracing leads them to conclude that “by fusing these two elements, the comparative sequential method merits the distinction of being the principal overarching methodology for [comparative-historical analysis] in general” (Reference Falleti, Mahoney, Mahoney and Thelen2015: 236).

Falleti and Mahoney’s contribution is the definitive statement of how comparative case study research has long abandoned its Lijphartian origins and fully embraced treating cases as social processes. It is certainly true that process-tracing advocates have shown that some past critiques of Millian methods may not have been as damning as they first appeared. For example, Reference LiebersonLieberson’s (1994) critique that Millian case selection requires a deterministic understanding of causation has been countered by set-theoretic process tracers who note that causal processes can indeed be conceptualized as concatenations of necessary and sufficient conditions (Reference MahoneyGoertz and Mahoney 2012; Reference Mahoney and VanderpoelMahoney and Vanderpoel 2015). After all, “at the individual case level, the ex post (objective) probability of a specific outcome occurring is either 1 or 0” (Reference MahoneyMahoney 2008: 415). Even for those who do not explicitly embrace set-theoretic approaches and prefer to perform a series of “process tracing tests” (such as straw-in-the-wind, hoop, smoking gun, and doubly-decisive tests), the objective remains to evaluate the deterministic causal relevance of a historical event on the next linkage in a sequence (Reference CollierCollier 2011; Reference MahoneyMahoney 2012). In this light, Millian methods appear to have been thrown a much-needed lifeline.

Yet processualist researchers have implicitly exposed new, and perhaps more damning, weaknesses in the traditional use of the comparative method. Here, Reference Falleti, Mahoney, Mahoney and ThelenFalleti and Mahoney (2015) are less engaged in highlighting how their focus on comparing within-case sequences should push scholars to revisit strategies for case selection premised on assumptions that process-tracing advocates have undermined. In this light, I begin by outlining three hitherto underappreciated threats to inference associated with the traditional use of Millian case selection: potentially ignoring (1) ordered and (2) paced causal processes, and ignoring (3) the possibility of equifinality. I then demonstrate how risks (1) and (2) can be attenuated deductively by formulating processualist theories and tweaking Millian designs for case selection.

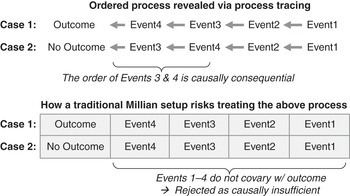

Risk 1: Ignoring Ordered Processes

Process-sensitive social scientists have long noted that “the temporal order of the events in a sequence [can be] causally consequential for the outcome of interest” (Reference Falleti, Mahoney, Mahoney and ThelenFalleti and Mahoney 2015: 218; see also Reference PiersonPierson 2004: 54–78). For example, where individual acts of agency play a critical role – such as political elites’ response to a violent protest – “reordering can radically change [a] subject’s understanding of the meaning of particular events,” altering their response and the resulting outcomes (Reference AbbottAbbott 1995: 97).

An evocative illustration is provided by Reference SewellSewell’s (1996) analysis of how the storming of the Bastille in 1789 produced the modern concept of “revolution.” After overrunning the fortress, the crowd freed the few prisoners held within it; shot, stabbed, and beheaded the Bastille’s commander; and paraded his severed head through the streets of Paris (Reference SewellSewell 1996: 850). When the French National Assembly heard of the taking of the Bastille, it first interpreted the contentious event as “disastrous news” and an “excess of fury”; yet, when the king subsequently responded by retreating his troops to their provincial barracks, the Assembly recognized that the storming of the Bastille had strengthened its hand, and proceeded to reinterpret the event as a patriotic act of protest in support of political change (Reference SewellSewell 1996: 854–855). The king’s reaction to the Bastille thus bolstered the Assembly’s resolve to “invent” the modern concept of revolution as a “legitimate rising of the sovereign people that transformed the political system of a nation” (Reference SewellSewell 1996: 854–858). Proceeding counterfactually, had the ordering of events been reversed – had the king withdrawn his troops before the Bastille had been stormed – the National Assembly would have had little reason to interpret the popular uprising as a patriotic act legitimating reform rather than a violent act of barbarism.

Temporal ordering may also alter a social process’s political outcomes through macro-level mechanisms. For example, consider Reference FalletiFalleti’s (2005, Reference Falleti2010) analysis of the conditions under which state decentralization – the devolution of national powers to subnational administrative bodies – increases local political autonomy in Latin America. Through process tracing, Falleti demonstrates that when fiscal decentralization precedes electoral decentralization, local autonomy is increased, since this sequence endows local districts with the monetary resources necessary to subsequently administer an election effectively. However, when the reverse occurs, such that electoral decentralization precedes fiscal decentralization, local autonomy is compromised. For although the district is being offered the opportunity to hold local elections, it lacks the monetary resources to administer them effectively, endowing the national government with added leverage to impose conditions upon the devolution of fiscal resources.

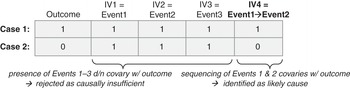

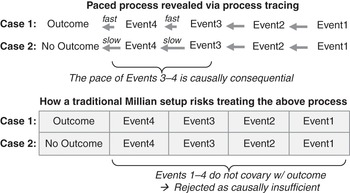

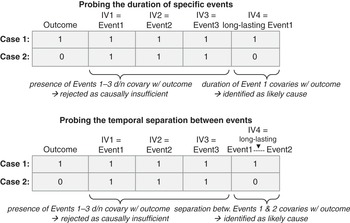

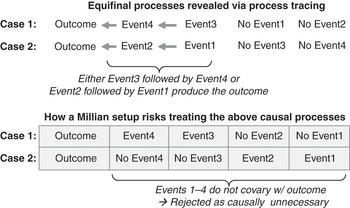

For our purposes, what is crucial to note is not simply that temporal ordering matters, but that in ordered processes it is not the presence or absence of events that is most consequential for the outcome of interest. For instance, in Falleti’s analysis both fiscal and electoral decentralization occur. This means that a traditional Millian framework risks dismissing some explanatory events as causally irrelevant on the grounds that their presence is insufficient for explicating the outcome of interest (see Figure 7.2).