Introduction

Addressing issues around race, ethnicity and culture in therapy can often elicit difficult emotions for therapists. In our experience of delivering training on Developing Cultural Competence with CBT therapists we have found that many therapists lack the confidence to ask questions about a service user’s ethnicity, culture or experiences of racism in case they make mistakes or offend the person. Few are provided with the time and space in supervision to reflect upon these issues and develop their confidence and skills. Due to the lack of training and support that most CBT therapists have received in this area, we think many therapists are not aware of either the importance of exploring these issues in therapy or of their own skills gaps. Commitment and investment is needed by therapists, by service managers, by Clinical Commissioning Groups, as well as at research and policy levels to make real progress to address these issues.

This article will look at placing race, ethnicity and culture into some form of context and to create a shared understanding of these terms for CBT therapists. It aims to help therapists and service managers conceptualize how they can start working more effectively with service users from different cultural backgrounds by offering some best practice guidance. It also discusses the need to further develop ethical guidelines for CBT therapists in the UK and to indicate some areas where further research is required. For the purpose of this article, when we talk about therapists, this also includes supervisors and clinical leads as they also have clinical caseloads.

Many of the ideas shared in this article are from our own extensive experiences of working with Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities and the feedback we have received from the workshops we have developed and delivered alongside another CBT colleague to trainee and qualified CBT therapists on developing cultural competence in CBT, drawing on research findings where they are available.

The training we deliver is typically a one-day interactive workshop exploring ideas of ethnicity, implicit biases, and culturally sensitive and culturally adapted therapy, and how they can be taken into consideration in therapy sessions. The authors themselves are from diverse backgrounds, BAME and LGBTQ communities. Workshop participants have also been from various backgrounds including white British, LGBTQ and BAME communities. Many participants have worked in primary care Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services, but some therapists have also worked in secondary care, voluntary sector and private practice. From November 2017 to October 2018, over 150 CBT therapists participated in workshops to develop cultural competence in CBT including developing cultural competence for CBT supervisors. We reviewed 38 feedback forms from two workshops we recently delivered, one in September 2018 and one in October 2018. Thirty-one of the 38 participants found the workshops ‘very helpful’ or ‘helpful.’ We hope to review the workshops in more detail in a future article.

The Equality Act (2010): race, ethnicity and culture

Race is one of the protected characteristics in the Equality Act (2010). It refers to a group of people defined by their colour, nationality, ethnic or national origins which may not be the same as their current nationality (UK, HM Government, 2010). Religion or belief (or a lack of), is a separate protected characteristic of the Equality Act (2010).

The terms race and ethnicity are commonly seen as interchangeable, but they have different connotations and usage. From the 17th century in Europe the term race was grounded in beliefs of biological differences between groups, such that skin colour and other physical features, indicated essential differences in abilities and character traits (Beck, Reference Beck2016). These beliefs were used to justify power hierarchies, and provide grounds for exclusion. For example, in apartheid in South Africa and racial segregation in the USA the concept of race was used to justify discrimination. Since the mid-20th century, research in genetics and social sciences have discredited these beliefs and societal changes have led to race being seen as more of a social construct (Beck, Reference Beck2016), but it remains a ‘loaded’ term.

Ethnicity can be seen as ‘a dynamic and subjective definition of one’s self in relation to a range of factors including language, geographical origin, skin colour, political preferences and religious and cultural practices’ (Loue, Reference Loue2006; cited in Beck, Reference Beck2016, p.8). It can also refer to a group of individuals who share a common and distinctive culture passed through different generations (Zenner, 1996; cited in Jandt, Reference Jandt2017).

Ethnicity can therefore be seen as a much broader social construct than race. For example, people who have migrated to the UK from other countries may still relate their ethnic identity to their country of origin, whereas their offspring, whilst sharing similar physical characteristics, may identify themselves as having a different ethnicity.

Cultures provide ways of interpreting the environment and the world, as well as relating to other people (Jandt, Reference Jandt2017). Damasio sees culture in an evolutionary context; our world and our environment is so complex and varied that social networks and cultures develop to regulate life and help us survive (Damasio, 2010; cited in Jandt, Reference Jandt2017).

Definitions of culture have changed over the years. In the 19th century the term culture was synonymous for Western civilizations with Western nations believing their way of life was superior (Jandt, Reference Jandt2017). The idea that all societies pass through different developmental stages was made popular by a British anthropologist, Sir Edward B. Tylor (1871; cited in Jandt, Reference Jandt2017). These stages began with ‘savagery’, progressed to ‘barbarism’, culminating in Western ‘civilisation’ (Jandt, Reference Jandt2017). However, Jandt (Reference Jandt2013; p.5) states: ‘To recognize that other peoples can see the world differently is one thing. To view their interpretations as less perfect than ours is another.’ This is where we believe racism and discrimination stems from.

Jandt (Reference Jandt2017) writes that traditionally culture was referred to as a ‘group’s thoughts, experiences, and patterns of behaviour and its concepts, values and assumptions about life that guide behaviour and how those evolve with contact with other cultures’ (Jandt, Reference Jandt2017). Hofstede (1994; cited in Jandt, Reference Jandt2017) categorized these into symbols, rituals, values and heroes. Symbols refer to verbal and non-verbal language. Rituals are the collective social activities within a culture and can sometimes be influenced by religious beliefs and practices. Values are about principles and standards of behaviour, what is good or bad, normal or abnormal. These values are present in the majority of members belonging to a culture. Heroes are real or imaginary characters who serve as role models within that culture, for example heroes in cultural myths.

There are various ways in which culture is transmitted. Gong (Reference Gong2010) talks of there being three forms of cultural transmission. Vertical transmission is where one member of one generation talks to a biologically related member of another generation, for example parents through to offspring. Horizontal transmission is where individuals of the same generation communicate, for example peer interactions. Oblique transmission is where any member of one generation talks to any non-biologically related member of a later generation, for example through interactions with adults and institutions in one’s society or community. Some of these individuals may have a shared identity with both the country they consider to be their own and also their parent’s country of birth and/or parent’s faith. They will be recipients of vertical, horizontal and oblique cultural transmissions. These different interactions will shape and form how someone makes sense of these experiences, and how they see themselves, others and the world.

Despite the definition of race being broad in the Equality Act (2010), often people still focus on the physical characteristics of individuals when talking about race, implying a static concept, something which is fixed and cannot be changed. Therefore, for the purpose of this article, we will focus more on ethnicity and culture. Ethnicity is broader in definition and encompasses physical characteristics amongst others. It is more fluid and subjective. The work of Tariq Modood is important in this area.

Modood et al. (Reference Modood, Beishon and Virdee1994) write: ‘Ethnic identity, far from being some primordial stamp upon an individual, is a plastic and changing badge of membership. Ethnic identity is a product of a number of forces: social exclusion and stigma and political resistance to them … the boundaries of groups are unclear and shifting, especially when groups seek to broaden an ethnic identity or to accommodate membership in a number of overlapping groups. And this leaves out the broader social, economic and political forces.’

Ethnic diversity in Britain is a complex, multi-dimensional social and cultural issue. It poses deep challenges and opportunities to the practice of psychotherapy. This is particularly true when psychotherapy is taking place between people with ethnic identities that are labelled as ‘black’ or ‘white.’ As Lago and Thompson (Reference Lago, Thompson and Palmer2002; p. 4) ask: ‘Given that relations between black and white groups over several centuries have been typified by oppression, exploitation and discrimination, how might contemporary relationships within counselling be transformed into creative (rather than further damaging) experiences?’

Understanding the current social and political climate as it impacts on the experience of service users and therapists

It is a running joke amongst many Asians that they are often asked, ‘Where are you from?’ When the person replies with which part of the UK they are from, they will be asked again ‘No, where are you really from?’ Again after giving the same answer, they will then be asked, ‘Where are your parents from?’ If someone is an offspring of a migrant, they will automatically be given the same ethnic label as their parents’ origin of birth, despite their experiences being similar to their white counterparts. This can be a confusing experience for service users who have always considered the UK to be their country and have felt part of society, and are now made to feel like the ‘Other’. Naturally thoughts of being rejected by those you consider as your own may elicit difficult emotions and force people to re-evaluate their identity.

It is important that therapists are aware that regardless of what service users might identify as their ethnic identity, there may be certain experiences that will be influenced by their physical appearances, which includes their skin colour and facial features, and how they choose to dress. For example, British-born Muslim females who choose to wear the hijab, or Sikhs who choose to wear a turban, both religious head coverings, despite identifying as British, have English as their first language, work with and socialize outside of work with white British people, have been known to face both verbal and physical abuse because of how they look and how they choose to dress.

Therapists also need to be aware of the impact the rise in Islamophobia, anti-Semitism and other forms of racism has on service users. Even Members of Parliament (MPs), in what is considered to be a reputable profession, have been criticised. The Conservative party has been criticised for Islamophobia in its party, and the Labour party for anti-Semitism.

Issues such as austerity and Brexit and how they are portrayed in the media, along with a rise of far-right groups and activities, will have an impact on how the majority view minority groups.

One example is that after the EU referendum, the Polish community suffered verbal and physical attacks against migrants in public places, at work and in schools (‘Poles in UK fear spike in hate crimes’, The Guardian, 2017). The hate crimes are often under-reported or not reported as they take place in different organizational contexts and workplaces. Often people from minority groups do not want to take the risk of reporting as they would risk losing their jobs and livelihood. This causes additional mental health problems (‘Anxious Poles in the UK won’t report hate crimes’, The Guardian, 2017).

Recent policy changes in Britain linked to the rise in anti-immigration, nationalistic and racist sentiments have had a massive impact, as seen in the experiences of the Windrush Generation whereby their identities of being British citizens have been challenged (‘In Praise of David Lammy’, GQ Magazine, 2018) and they have been denied NHS treatment (‘Londoner denied NHS cancer care’, The Guardian, 2018), as well as losing their jobs and homes (‘It’s inhumane: the Windrush victims’, The Guardian, 2018). This demonstrates how government policies themselves are responsible for creating structural inequalities in our society and the NHS itself. Furthermore, it is the government agenda that influences what services are delivered, and to whom.

These societal changes are creating fear in large groups of individuals from different backgrounds while the majority community is perhaps experiencing intensified guilt and shame. This fear is then perpetuated by sharing of information on social media. A recent example of this is ‘Punish a Muslim Day’ letter that was widely circulated online. The letter was based upon a points system. ‘Verbally abuse a Muslim’ would earn someone 10 points, ‘Pull the headscarf off a Muslim woman’ would earn someone 25 points, ‘Throw acid in the face of a Muslim’ was 50 points, ‘Beat up a Muslim’ was 100 points, ‘Torture a Muslim using electrocution, skinning, use of a rack’ was 250 points, ‘Butcher a Muslim using gun, knife, vehicle or otherwise’ was 500 points, ‘Burn or bomb a mosque’ would be 1000 points and ‘Nuke Mecca’ would earn 2500 points (‘Man arrested for “Punish a Muslim day” letters’, Metro, 2018).

Some of the hate crimes mentioned in the letter have already been committed and have (rightly) received exposure in the media. Paul Moore was jailed for life in March 2017 for running over a 47-year-old Muslim woman and a 12-year-old Muslim girl in Leicester. The judge said they were targeted for wearing Islamic clothing (‘Man jailed for life’, The Guardian, 2018). In October 2018, 35-year-old David Parnham pleaded guilty at the Old Bailey to 15 offences, including soliciting to murder and staging a bomb hoax after he was charged with sending the ‘Punish a Muslim Day’ letters. He could receive a life sentence after he encouraged recipients of his post to attack ethnic minorities and would donate £100 to charity for each killing (‘Lincoln man admits sending “Punish a Muslim Day” letters’, BBC, 2018). Two Muslim cousins were victims of an acid attack. Although the intent is unclear, the perpetrator was white. Again given the current climate, many Muslims see this as a hate crime. One of the victims himself saw this as a hate crime in an interview he gave to Channel 4 news (‘Acid attack on two Muslim cousins’, The Guardian, 2017). In April 2018 the BBC reported that John Tomlin was sentenced for 16 years for the unprovoked attack (‘Beckton birthday acid attacker’, BBC, 2018).

From April 2017 to March 2018, there was a 40% rise in religious hate crime, with over half of religiously motivated attacks directed at Muslims. Jews were the next most commonly targeted group (Dearden, Reference Dearden2018). The Guardian reported that there were 1382 anti-Semitic incidents recorded nationwide in 2017 by the Community Security Trust, a rise of 3% in comparison with 1346 in 2016 (‘Antisemitic incidents in UK at all-time high’, The Guardian, 2018).

There has been an increase in attacks on faith institutions like mosques and synagogues. A mosque in Newton Heath experienced three suspected arson attacks in three years (‘Manchester mosque left gutted’, The Guardian, 2017).

In September 2018 armed officers were deployed by the Counterterror police as the Jewish community marked Yom Kippur, the Jewish new year (‘Armed police deployed in counterterror operation’, The Independent, 2018). What should have been a happy occasion may also have created anxiety in the Jewish community.

In light of these recent incidents, it is understandable why people from BAME communities may be afraid and that this is something to take into consideration in therapy sessions. As an example, one of the authors was encouraging a service user with post-traumatic stress disorder, following an assault, to go outside alone as part of the treatment. However, the service user was scared after they heard about the acid attack mentioned above. Asking a victim of assault to go out alone when there are threats, whether they are real or perceived, towards their ethnic group can inadvertently cause them more distress. Understanding and exploring these factors are important and can affect the therapist’s understanding of the service user’s problems. It is important that the formulation should take service users’ cultural background into account, as well as their communities (Persons and Davidson, Reference Persons, Davidson and Dobson2001).

Developing culturally sensitive practice as CBT therapists

We will explore some emerging areas of good practice drawing on experience, the literature and the evidence base. This is a developing area requiring further investment in research.

Culturally adapted and culturally sensitive CBT

Beck (Reference Beck2016) distinguishes between culturally adapted CBT (CA-CBT) and culturally sensitive CBT (CS-CBT). CS-CBT is more similar to the CBT provided to the majority of white service users, but is adapted on a case-by-case basis by therapists and service users, and includes discussion of issues of ethnicity and culture. However, CA-CBT is adapted for specific ethnic groups and for a specific disorder (Beck, Reference Beck2016). The active components of CBT are retained, but the language, examples and metaphors are culturally specific. The therapy incorporates cultural values and practices, and there is additional emphasis on context for the service user, such as their economic situation, experiences of discrimination and migration history. An example of a CA-CBT is Ghazala Mir’s adaptation of the Behavioural Activation (BA) approach for Muslim communities, which is widely available online (Mir et al., Reference Mir, Kanter, Meer, Cottrell, McMillan and House2012). A BA treatment manual and self-help booklet have been developed to be used by the service user and therapist (Shabbir et al., Reference Shabbir, Mir, Meer and Wardak2012). The self-help booklet contains teachings from the Islamic faith; for example, on page 8 there is a subheading: ‘Tie your camel: do your part.’ It goes on to say, ‘Change starts with the individual. There is a cause and effect of our actions and we cannot change things unless we ourselves make an effort to change.’ To elaborate on this, they share the following story:

‘One day Prophet Muhammad (pbuh – peace be upon him) noticed a Bedouin leaving his camel without tying it. He asked the Bedouin, ‘Why don’t you tie down your camel?’ The Bedouin answered, ‘I put my trust in Allah’. The Prophet then said, ‘Tie your camel first, then put your trust in Allah.’

This example can be used to motivate service users to be active participants in therapy, something which is encouraged in standard CBT. However, the information used to facilitate this process comes from the individual’s religion, Islam in this example. Similar teachings may also be derived from other religions to help service users with different faiths. Therapists will need to have some knowledge of those religions. To help with this, we recommend using the Chaplaincy service most NHS trusts have, as well as developing relationships with local faith organizations.

In their research Mir et al. (Reference Mir, Meer, Cottrell, McMillan, House and Kanter2015) found that the use of religious teachings in therapy were of more value to Muslim service users than standard approaches; however, therapists required more support than was anticipated to deliver the interventions. This is an example of the need for investment of resources and support for therapists to build their confidence when working with diverse communities.

The importance of getting culturally sensitive therapy right is illustrated in an example raised at our ‘All Cards on the Table’ workshop in November 2017. One of the authors raised the example of working with a Tamil group, and the local IAPT service. The IAPT service had carefully translated the computerized CBT program ‘Beating the Blues’ into Tamil. When a video of this was shown at the Temple the reaction was immediate. The example given of behavioural activation was getting out and about by going the pub. Community leaders were not happy with this advice and did not want to engage with the training. It is important to work from the framework of the BAME service users rather than making assumptions that they would wish to engage in similar activities as the mainstream culture.

When is a good time to explore someone’s ethnicity and culture?

We highly recommend reading Beck’s (Reference Beck2016) ‘Transcultural Cognitive Behaviour Therapy in Anxiety and Depression: A Practical Guide’. Chapter 2 discusses service users’ perspectives on how to raise and discuss issues related to ethnicity and culture, different experiences and values; when to raise these issues, such as during assessment and formulation; and the impact of this on the therapeutic relationship. Beck (Reference Beck2016) emphasizes the importance of therapists becoming comfortable with raising these issues and skilled at following the lead of service users who raise the issue by asking additional questions. In general he recommends that these issues are raised early in the therapy but after the initial rapport has been established.

One example came up recently during our training events. During a lecture on Working with Diversity in CBT, trainee IAPT high-intensity therapists from the University of Nottingham discussed goal setting as a good opportunity to explore religion, ethnicity or culture. For example, if the service user would like to re-engage with certain religious or cultural practices, this would be a perfect opportunity to explore the importance of these practices and what they mean to the service user.

At recent Developing Cultural Competence workshops, therapists have discussed many examples of how and when they raise these issues in a relaxed and open way with service users. Some skilled therapists described bringing these issues into the discussion early on, saying things like ‘We look very different, you and I, what will it be like for you working with someone like me?’ Others mention being tuned in to noticing important opportunities to respond to in ways that open up underlying issues and concerns. For example, one of the authors, a white therapist, gave an example of working with a black British service user who was worried about the way her teenage son behaved when angry. She expressed concern for his safety and said, ‘He’s going to be a big man’. The therapist reflected back, ‘A big, black man’, opening up an opportunity for discussion of the service user’s worry that her son needed to be extra careful with anger management to avoid triggering mainstream stereotypes of black men.

Therapists often feed back that it is the wealth of stories and experience shared in a non-judgemental way at the workshops which helps them to pick up new skills and gain confidence.

BAME therapist working with white service users with prejudicial views

If BAME therapists are working with white service users who hold prejudicial views, we strongly advise discussing this in supervision. Therapists should feel safe and protected when working with any service user. If the therapist feels comfortable, they can explore these views with the service user. In our experience, service users often have these views because of the socio-economic problems they are experiencing, and are feeling frustrated or have a lack understanding of other cultures due to having little or no contact with them. Their perceptions of minority groups may be influenced by the media narrative that immigrants are a strain to the UK economy. We would recommend not directly challenging their views, but developing a good therapeutic relationship and understanding of how and why these views have developed. Often we find that at the end of therapy, these views have shifted due to the therapeutic relationship, even though that was not the focus of therapy.

We had some encouraging feedback from a participant at the end of our ‘All Cards on the Table’ training in November 2017: ‘If a patient says racist things I take it personally and get anxious. But now, if anyone says anything racist I will ask them why’.

Therapists’ own prejudices and implicit biases

When working with service users from different ethnic or cultural backgrounds, it is important for therapists to be mindful that their own prejudices and stereotypes do not interfere in the therapy process. We all have implicit biases, which occur when our associative brain makes incredibly quick judgements and assessments of people and situations, often without us realizing. Our biases are influenced by our background, cultural environment and personal experiences (Greenwald and Kriege, Reference Greenwald and Kriege2006).

Instead of coming from the viewpoint that we do not have any prejudices, as that can make the therapist defensive and interfere with the therapy process, we recommend therapists start with acknowledging their own implicit biases. Then whilst having this conscious awareness and with a sense of curiosity, they can explore service user’s experiences and identity. Understandably where there are constraints on the number of sessions that can be offered, therapists may feel pressured to rush this process. However, they should allow for extra time in sessions for this, as this can enhance the therapeutic relationship and facilitate therapy itself.

White therapist working with a service users from a BAME background: dealing with difficult emotions that may arise in the therapist

As we have learned in our Developing Cultural Competency workshops, addressing issues around ethnicity and racism in therapy can sometimes trigger difficult emotions for white therapists, such as anxiety, guilt and shame. Anxiety about making mistakes can lead to avoidance behaviours, so some therapists report avoiding mentioning issues of racism, ethnicity or culture with BAME service users in case they make mistakes.

The Five Areas model given in Fig. 1 demonstrates what may happen when a therapist encounters a BAME service user or someone they perceive to be ‘different’ from them. As Brown (Reference Brown2008, p. 56) says in a case study about a white therapist working with a black client, ‘We avoid empathetic connection by convincing ourselves that we can’t really understand experiences we haven’t actually had’.

Figure 1. Impact on therapist Five Areas model.

Feelings of shame and guilt may arise linked to the therapist’s awareness of their own relative social privilege in relation to ethnicity (McIntosh, Reference McIntosh1989). A white therapist hearing a service user describing experiences of racism may experience feelings of shame and guilt. These emotions are linked to the need to belong. They tend to be triggered when we sense a possible rupture in a relationship linked to who we are (shame), or what we have done (guilt), or to what a group we belong to has done. In a general way they are adaptive in that they motivate us to repair relationships and take time out to reflect and re-evaluate on our or our group’s behaviour (Tangney et al., Reference Tangney, Miller, Flicker and Hill1996). However, the immediate response to these emotions in the therapist is likely to be a degree of emotional withdrawal, and self-focus leading to a reduction in empathy for the service user which is not helpful in a therapy session. One of the authors attended a racism and mental health event organized by Kids of Colour (http://kidsofcolour.com), an organization in Manchester for young BAME people to explore their experiences of race, identity and culture in modern Britain. The author learned that racism was affecting these young peoples’ mental health, yet it was not being explored in therapy when the young people sought help. It is understandable why these young people and others may perceive the lack of exploration of their experiences of racism, which have contributed to the deterioration of their mental health, as racism or that the particular type of therapy being offered to them is not suitable for their ethnic or cultural background. As Brown says, ‘Ultimately feeling shame about privilege actually perpetuates racism’ (Brown, Reference Brown2008, p. 59). There is large body of research indicating that compassion and empathy are a good solution to the paralysing impact of shame and guilt (Brown, Reference Brown2008; Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2010).

It is helpful for the white therapist to become skilled at recognizing and using their ‘self CBT’ skills to tolerate uncertainty, self-soothe and move through their own feelings of guilt and shame if they arise during therapy, focusing on reaching for their empathy and understanding of the client’s experience (Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Kennerley, McManus and Westbrook2010, p. 458). Given the nature of these emotions it is essential that there is a safe and secure supervisory relationship, where the therapist can be confident in their supervisor’s skills at providing this space for learning (Beck, Reference Beck2016, p. 163). Receiving supervision from colleagues with cultural competence will be important to enable therapists requiring support to develop these skills. In our experience, providing safe, non-judgemental training settings is also important for therapists to recognize their avoidance, question these beliefs and learn from challenging experiences. The Five Areas Model in Fig. 2 demonstrates being able to work with BAME communities despite experiences difficult feelings of anxiety, shame and guilt.

Figure 2. Managing impact on therapist Five Areas model.

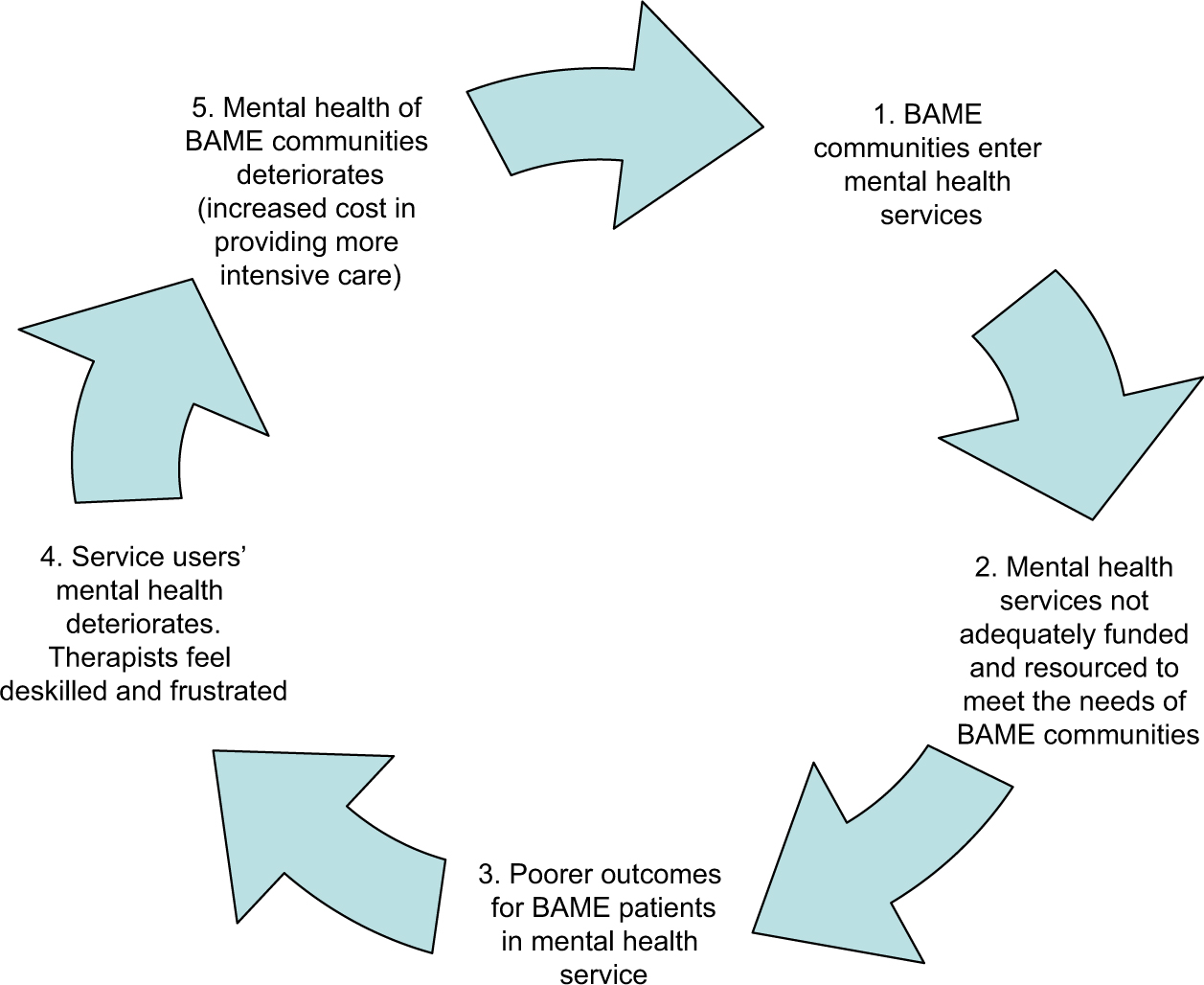

Figure 3. Vicious cycle of not adequately funding and resourcing mental health services for BAME communities.

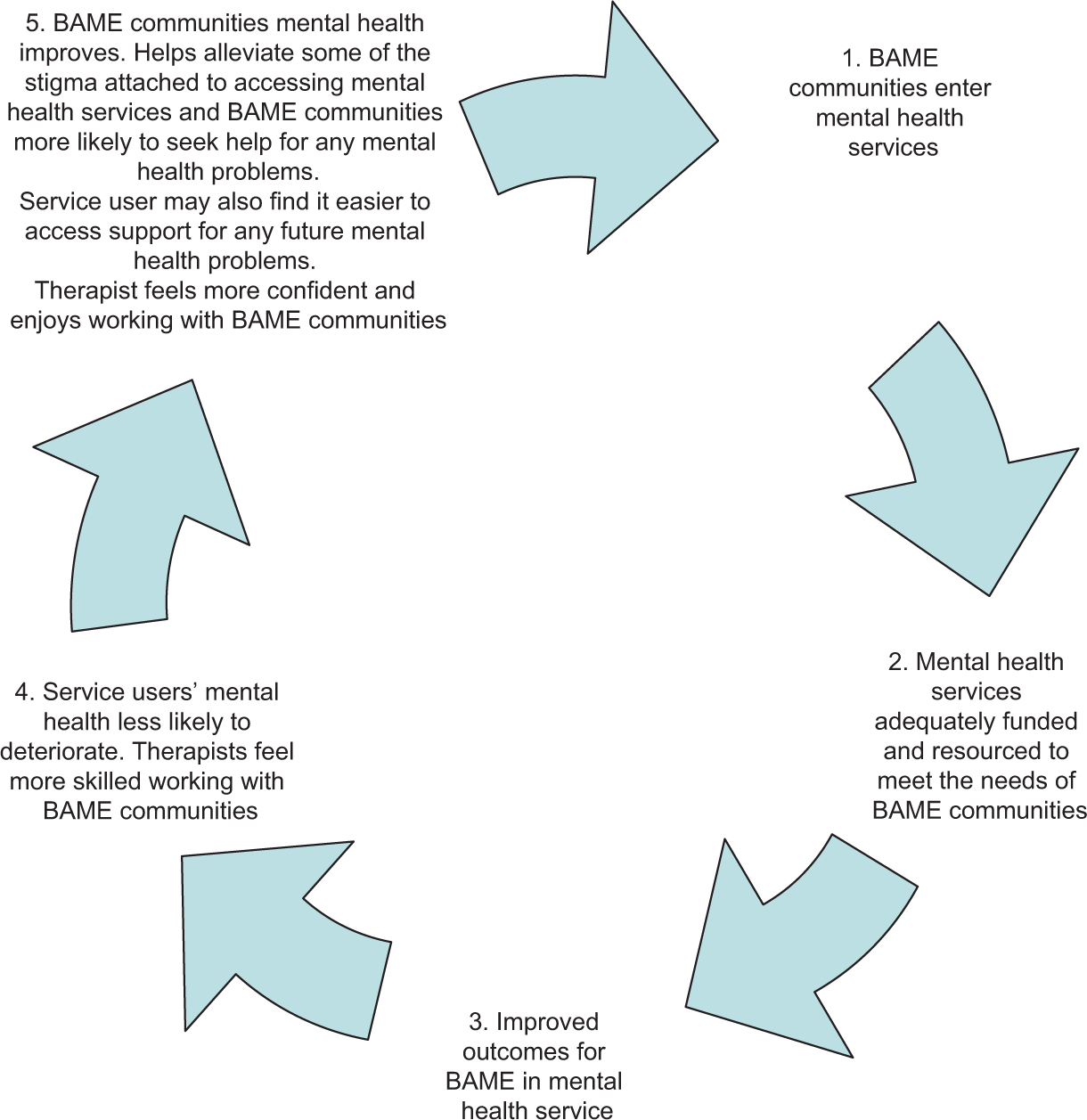

Figure 4. Virtuous cycle of adequately funding and resourcing mental health services for BAME communities.

We suggest white therapists who mainly work with white service users speak to their managers about creating opportunities to work with service users from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and seek cultural competency training so they can improve their confidence and skills and overcome any avoidance.

The role managers of local services can play to support staff

We are mindful that to meet service demands, service managers can sometimes place a cap on the number of sessions therapists can offer service users. However, service managers are responsible for the wellbeing of their staff. They need to be aware of the issues discussed in this article as these issues will be affecting their staff who work with service users from different cultural backgrounds. This could be white therapists working with BAME service users or BAME therapists working with white service users. We would like to take this opportunity to remind managers that NICE (2009; 1.5.3.2) guidance makes recommendations for the number of sessions that should be offered for different presenting problems; for example, it recommends ‘For all people with depression having individual CBT, the duration of treatment should typically be in the range of 16 to 20 sessions over 3 to 4 months.’

Service managers have a responsibility to ensure all staff are supported to work with service users of different ethnicities and cultures through providing access to interpreters, translated materials, Continuing Professional Development (CPD) workshops and culturally competent supervision, It is also important to allow more time in therapy sessions (especially when working through interpreters) because as well as dealing with service users’ mental health problems, the issues discussed in this article have to be explored. This will enhance both the service users’ and therapists’ experience of therapy. Positive experiences are likely to instil confidence in therapists to work with service users from different ethnicities and cultures. They are also likely to instil confidence in service users in mental health services, and could help to break down the stigma associated with seeking support for mental health problems.

We recognize that it is important to utilize therapists’ skills to help inform practice; however, in the spirit of promoting equality, managers also need to ensure that the responsibility of working with diverse communities is evenly distributed between BAME and non-BAME therapists. Gurpinar-Morgan et al. (Reference Gurpinar-Morgan, Murray and Beck2014) conducted qualitative research with BAME service users in Manchester who had successfully worked with cognitive behavioural therapists from white majority backgrounds. One of the themes they identified was working with ethnically similar and ethnically dissimilar therapists. They found that some service users may find it easier to discuss experiences such as racism, and cultural and religious practices with ethnically similar therapists, whilst others would prefer ethnically dissimilar therapists as they might believe that ethnically similar therapists make more assumptions about them. Therefore, there is no hard or fixed rule to match BAME therapists to BAME service users.

BAME therapists involved in BAME mental health development work

In many services we are mindful that often it is the BAME therapists who are allocated referrals of BAME service users because of their own ethnicities, while white colleagues may have little or no contact with BAME service users. BAME therapists in this position may come to feel responsible for the quality of service being provided to these service users, and struggle to deliver the best possible care, often without adequate support and resources from the service or their managers. We believe this area requires further investment and research to enable therapists to deliver therapy to as good a standard as is provided to white British service users. An example of this came up at one of our recent workshops. Two BAME therapists expressed concern about lower recovery rates for BAME service users in their services and were tasked to look into this; however, they were not allocated time in their roles to develop relationships with local community organizations in order to try and address the issue.

Services also need to be mindful that not all BAME therapists will want to work exclusively with BAME communities. The different expectations some services place on BAME therapists may limit the therapists’ professional development in other areas. We believe this can be seen as indirectly discriminating against BAME therapists and disadvantages them in comparison with their white colleagues (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2016).

Where services expect BAME therapists to be involved in service development work with local communities, managers need to be aware that these therapists also need to be supported to have access to additional learning resources and time. This could include translated literature, training and attending conferences, so that the learning can be brought back into services and evidence-based interventions can be tailored to the needs of service users from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

Service managers need to allocate funding, think flexibly and not be scared to be creative and develop different ways of working with different communities; for example, a BAME working group which one of the authors was involved in, performed an award-winning play to different communities in Urdu and English (‘Mental health support for minorities wins top prize’, Pennine Care NHS Foundation Trust, 2016). The play was to educate communities about what depression is and how it can have an impact on individuals and their families, and what support they could receive. Following on from this work, the access rates improved in the service.

CBT is often seen as a Westernized concept and it is important to develop resources to make it accessible to other communities. Lucy Maddox, BABCP’s Senior Clinical Advisor has made a series of podcasts on the BABCP website called ‘Let’s Talk About CBT’. One of the Podcasts (Maddox, Reference Maddox2018) is about an outreach event one of the authors of this article was involved with in Glasgow at the start of BABCP’s annual conference. In this podcast, an Islamic scholar Shaykh Abdul Aziz Ahmed gives his perspective on Muslim mental health. At the event, Shaykh Abdul Aziz used an 800-year-old Islamic text which has similar teachings to what we consider to be CBT for white Western communities.

Whilst we agree that promotional campaigns help raise awareness of mental health issues in the BAME community, this is not enough. We have often heard that some therapists are allowed to do some outreach work, and so services show an improvement in access rates, but we are concerned if there is no follow-through to deliver ongoing high quality of care. Doing some outreach work to improve access rates is one thing, delivering a high-quality service and moving service users to recovery is another. A recent example of this is when one of the authors questioned a therapist about what was offered to BAME communities in their service after the initial contact was made. They replied they had been trying look into this for a few years on their own and this part of their service had yet to be developed. The author advised them to share the responsibility with their service manager and to focus on their own personal development.

We strongly advise BAME therapists to reflect upon their own work, and think about whether the issue raised here is applicable to them. If so, we would advise them to discuss this with their supervisors, clinical leads and managers. We would also advise them to ask their white therapist colleagues to share responsibility and be involved in any work to improve access and recovery of BAME service users.

Some steps towards addressing structural inequalities in CBT services

The Equality Act 2010 sets a duty for sector service providers to: eliminate discrimination, harassment and victimization; advance equality of opportunity; and promote good relations between communities (UK, HM Government, 2010).

The Francis report was published in 2013 after serious failings at Mid Staffordshire Hospital. One of its main findings was that patients should always be put first and be protected from avoidable harm and any deprivations of their rights, and anything done by the NHS and those associated with it should be informed by this (Francis, Reference Francis2013). Mental health service providers need to remember this.

There has been evidence of inequalities in mental health services for decades. For example, the Policy Studies Institute report on Ethnicity and Mental Health: Findings for the National Community Survey (Nazroo, Reference Nazroo1999), reported that many more Afro-Caribbean men were hospitalized with schizophrenia than people from the white population, and that twice as many young Asian women committed suicide as young white women.

Butt et al. (Reference Butt, Clayton, Gardner and Huijbers2015) summarizes ways that BAME communities have significantly poorer mental health outcomes and poorer experience of services. BAME service users are often under-represented in primary care mental health services, and often have worse outcomes, leading to them being portrayed as ‘hard to reach’, and to deterioration in their mental health. They are over-represented in secondary care mental health services. Only after we address structural inequalities and the recommendations here are implemented, can we then start to consider whether the BAME community is hard to reach; until then we are of the opinion that no community is hard to reach.

The King’s Fund is a charity working in England who provide a public reference library specializing in health and social care resources to promote the best possible health and care for all. They undertake regular literature reviews in key areas. For their reading list on barriers to access to mental health services for BAME service users, see The King’s Fund (2016), or search their online library (The King’s Fund Library Catalogue, 2018). There is also a strong potential to mine the IAPT dataset for valuable information on outcomes for BAME service users in the IAPT services (NHS, 2018). Currently Lynne Carter, a Knowledge Mobilization Research Fellow and her colleagues at the University of Sheffield are reviewing such data (Carter, Reference Carter2018); however, her findings are yet to be published. We are mentioning this work as it will be of interest to those with an interest in inclusion in mental health.

In the areas of developing cultural competencies, there seems to be a stronger framework of training and research in the USA than the UK. For example, training courses for counsellors in ‘multicultural competencies’ have been well established for some time (Palmer, Reference Palmer, Palmer and Laungani1999). The competencies include: knowledge of own and other cultures; skills in multi-cultural counselling; and awareness of one’s own deep cultural influences. There is substantial research into their effectiveness. For example, Castillo et al. (Reference Castillo2007) ran a quantitative study with 74 first year MA students, predominantly white, who were training to be counsellors. At the end of their training, the 40 who were attending multi-cultural counselling classes showed a significant reduction in implicit racial bias and increase in awareness of cultural influences compared with the other 44, who had received equivalent training but without a multi-cultural focus. The before and after measures used were the Race-IAT (Race Implicit Association Test) (Greenwald et al., 1998; cited in Castillo, 2007) and the MCI (Multicultural Counselling Inventory) (Sodowsky et al., 1994; cited in Castillo, 2007). We suggest that there is a need for more research to help develop best practice standards for training in the UK.

One of the tools for setting minimum standards in psychotherapy is the code of ethics of the professional bodies, such as BABCP. This guides therapist training, criteria for accreditation and CPD. The preamble for the code of ethics for The American Counseling Association has diversity centre stage. It states:

‘The American Counselling Association is an educational, scientific, and professional organization whose members work in a variety of settings and serve in multiple capacities. ACA members are dedicated to the enhancement of human development throughout the life-span. Association members recognize diversity and embrace a cross-cultural approach in support of the worth, dignity, potential, and uniqueness of people within their social and cultural contexts.’ (American Counseling Association, 2014, p. 2).

The British Association of Counsellors and Psychotherapists ethical framework (BACP, 2016) also includes a substantial section on diversity, including promoting the valuing of diversity, avoidance of discrimination, and working sensitively with issues of identity.

In contrast, the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies, (BABCP, 2017) Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics of the BABCP seems more uni-dimensional. It says:

‘You must not allow your views about a service user’s sex, age, colour, race, disability, sexuality, social or economic status, lifestyle, culture, religion or beliefs to affect the way you treat them or the advice you give. You must treat service users with respect and dignity. If you are providing care, you must work in partnership with your service users and involve them in their care as appropriate.’ (BABCP, 2017, p. 6).

In our view there is a need to develop stronger professional, ethical guidelines in the area of working with diversity for CBT therapists in the UK. The guidelines need to be more proactive to equitably engage with BAME service users with a clear and strong emphasis on therapists to be more proactive to enable this to happen.

Summary

To summarize, we have provided an overview on the terms race, culture and ethnicity to provide a shared understanding of these terms for CBT therapists. We have recommended using the terms ethnicity and culture as race may be considered to be outdated, despite it being used in the Equality Act (2010) as one of its protected characteristics (HM Government, 2010). We have also provided best practice guidance for BAME and white therapists, as well as service managers, to enable them to work more effectively with service users from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds, for example to consider the current socio-political context. We have placed emphasis on evenly distributing work between BAME and non-BAME therapists, and providing access to resources including translated materials, training and supervision to deliver culturally competent care to BAME service users. We encourage therapists to recognize and question their own avoidance behaviours and implicit biases, and recommend that for therapists to do this effectively they will need training and supervision delivered in skilled, safe and non-judgemental settings.

Ultimately, we believe the responsibility of ensuring that equality is embedded in mental health services lies with all involved with the service users care. This includes commitment and investment from therapists, supervisors, clinical leads, service managers, Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and NHS England, otherwise the BAME mental health agenda will continue to be like a hamster in a wheel, making little progress (Fig. 3).

This article is intended to be a resource to enable services to break away from this cycle (Fig. 4). We hope it provides useful guidance to deliver culturally competent services and therapy to mental health service users, regardless of their ethnicity and culture, and will pave the way for further investment in research and improvements to practice in this area.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the BABCP’s Equality and Culture Special Interest group and other therapists who attend our workshops. Their contributions and feedback continue to enlighten us and provide us with the motivation to continue to talk about issues of inequality in mental health services for BAME service users.

Financial support

No financial support was received for this study.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval was not needed for this article.

Key practice points

(1) To support CBT therapists to conceptualize key terms such as race, ethnicity and culture which may be used synonymously with BAME communities.

(2) To develop CBT therapists’ confidence to work with BAME communities and have an awareness of the current political context which may be affecting service users’ mental health.

(3) Service managers need to work alongside commissioners to fund their services adequately to enable them to deliver training, provide support (supervision, etc.) and resources (including allocating time to do outreach work and translating materials). This will enable their staff to work effectively with BAME communities.

(4) To remind CBT therapists and service managers of their duty of care towards working with all diverse communities as is expected under the Equality Act (2010), and renew their commit towards improving outcomes for BAME communities.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.