The Postgraduate Education and Training Board (PMETB) was established by the General and Specialist Medical Practice (Education and Qualifications) Order, approved by parliament on 4 April 2003 to develop a single, unifying framework for postgraduate medical education and training across the UK. The Order placed a duty on the Board to establish, maintain and develop standards and requirements relating to all aspects of postgraduate medical education and training in the UK.

The remit of the Board, which is accountable to parliament but will act independently of government, covers basic and higher specialist training (although it is likely that this distinction will cease to exist following the unified training grade proposed by Modernising Medical Careers (Department of Health, 2003, 2004)). However, the remit does not cover undergraduate medical education, nor that of pre-registration doctors, which remains the responsibility of the General Medical Council and universities.

The PMETB will replace the Specialist Training Authority (STA) and the Joint Committee on Postgraduate Training for General Practice (JCPTGP). It went ‘live’ in September 2005 but it already commenced its role in Specialist Registration under Articles 11 and 14 in July 2005, although at the time of writing precise details have not been issued. The PMETB website went online on 18 November 2004. (A description of the aims, visions and values of the Board can be found at http://www.pmetb.org.uk). Further documents of interest include Postgraduate Medical Education and Training (Department of Health, 2001) and Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board: Statement of Policy (Department of Health, 2002).

There are major implications for every aspect of the planning, delivery, evaluation and assessment of education for psychiatrists.

Original policy aims

In reviewing relevant government publications since the The NHS Plan (Department of Health, 2000) and developments in medicine and medical regulation during that period, certain themes or aims appear. These include the desire to change or ‘ modernise’ the institutions of medicine and, indeed, all professional healthcare. A further aim of increasing and empowering patient and public involvement in postgraduate medical education was strongly endorsed in the Bristol inquiry (Reference KennedyKennedy, 2001). Finally, there was the aspiration to harmonise what was seen by some to be a ‘diverse collection of historical arrangements’ and bring them together under a single organisation with collective responsibility.

Structure of the PMETB

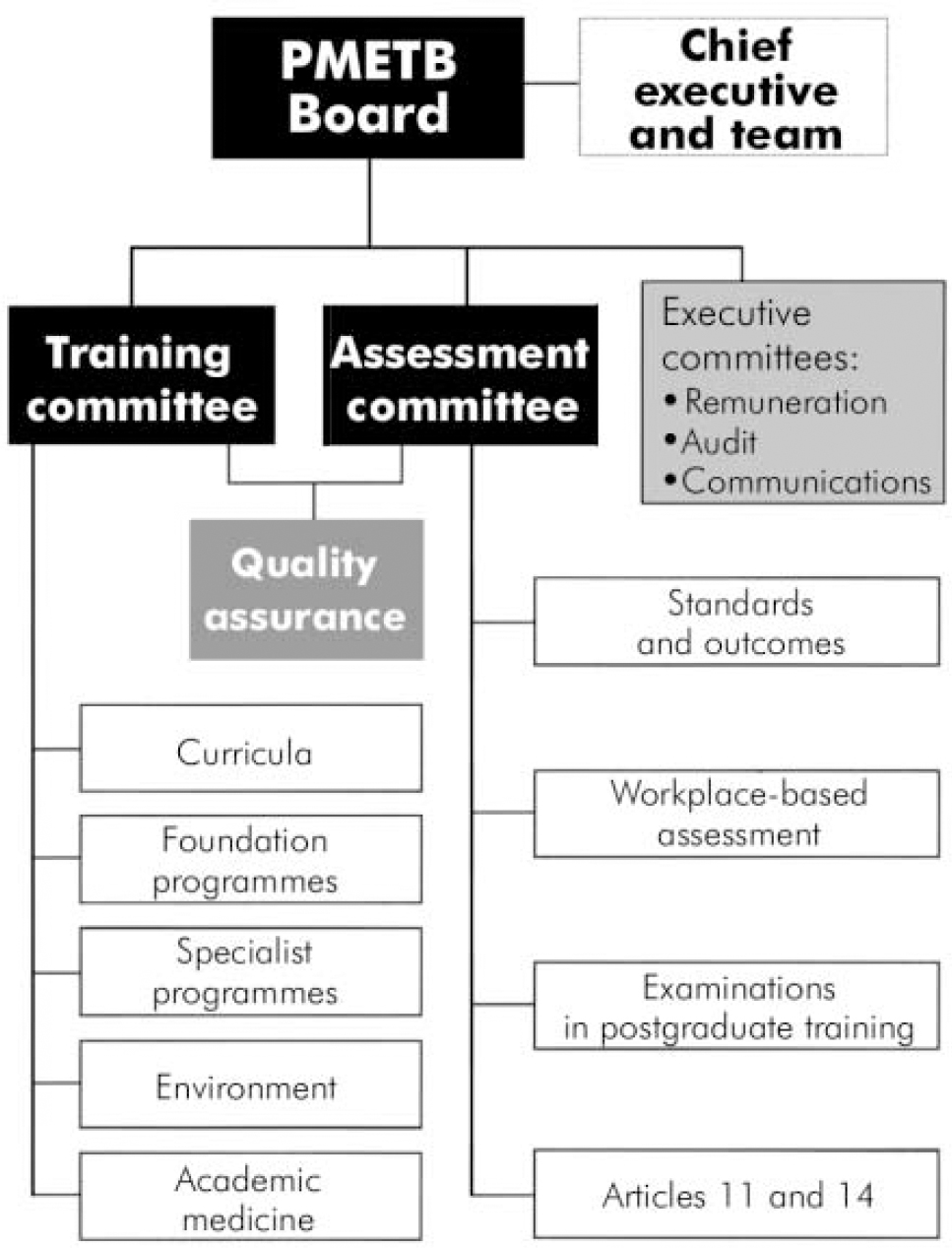

Figure 1 shows the current board, committee and operating structure for the PMETB. There are two statutory committees advising the Board on training and assessment. Through these it will determine the requirements for all organisations that provide postgraduate medical training and examinations, which of course, includes all the Royal Colleges. Several members of the Royal College of Psychiatrists have been invited on to the PMETB committees but will serve in their own right and not as formal representatives.

Fig. 1.

The operating structure of the Postgraduate Education and Training Board. ▪, Statutory bodies;

![]() , other committees, subcommittees;

, other committees, subcommittees;

![]() , joint committees. (Reproduced from PMETB Structures and Committees.)

, joint committees. (Reproduced from PMETB Structures and Committees.)

Role and responsibilities of the PMETB

The Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board will be responsible for the establishment, maintenance and monitoring of standards and quality in postgraduate medical education. It will be responsible for all postgraduate medical education and assessment of doctors completing postgraduate training. The specific responsibilities of the Board include: approval of postgraduate medical education and training programmes and courses; accreditation of postgraduate education (training systems and trainers); quality assurance of the postgraduate medical education and training system, ensuring that assessment and examinations undertaken are reliable, valid and fair; the issue of certificates of completion of training (CCT); and the assessment of equivalence of the qualifications, training and experience of doctors seeking a statement of eligibility to apply for entry to the Specialist or General Practice Registers of the General Medical Council.

This means that the Royal Colleges will no longer have independent control over training, curricula, examinations, CCT decisions and approval visits. Rather, they will work with the PMETB within the parameters of service level agreements that have been drawn up in part.

Vision of the PMETB

The PMETB's stated vision is:

‘to achieve excellence in postgraduate medical education, training, assessment and accreditation throughout the UK to improve the knowledge skills and experience of doctors and the health and healthcare of patients and the public’.

Its values include independence, collaboration and inclusiveness, responsiveness, ensuring diversity and a readiness to tackle difficult issues.

There are some clear educational requirements. These include an emphasis on workplace learning and assessment that focuses on performance, i.e. what a doctor actually does rather than merely theory, increasing responsibility being invested in the trainee for their own learning and assessment and, of course, lay involvement in the latter processes.

Looking beneath the surface we can already see the emergence of expectations around curricula and assessment. These have appeared in the form of papers available at the PMETB website (http://www.pmetb.org.uk). It can be anticipated that proposed College curricula and examinations will be assessed against the published vision. Therefore, the curriculum will require:

‘a statement of the intended aims and objectives, content, experiences and outcomes of an educational programme including: a description of structure… and a description of expected methods of learning, teaching, feedback and supervision’.

Service level agreements

The PMETB has been working with the Royal Colleges since February 2005 to develop service level agreements. The service level agreement outlines areas of work that the Board will require Colleges and faculties to undertake in order to meet its legislative requirements. The five areas are:

-

(a) CCTcertification (Article 8),

-

(b) equivalence arrangements (Article 11/14 applications),

-

(c) appeals (Article 21),

-

(d) other certificate applications (certificates under European Directive 93/16/EEC as the UK competent authority), and

-

(e) standards and quality assurance.

For example, the process of CCT application will be provided by the PMETB but Colleges will make the CCT recommendation. Therefore the Colleges will enrol trainees, maintain training files, conduct specialty specific assessment programmes and collect assessment: the Record of In-Training Assessment (RITA) forms. They will gather the required information and send the recommendation with supporting documentation to the Board. Perhaps not greatly different to the current system if one substitutes the Board for the Specialist Training Authority (STA).

However, turning to the potential agreements around standards and quality assurance, a new and different world emerges. The position for curricula and assessment is outlined above. Quality assurance relates to what is now known as hospital visiting or accreditation or approval process. The PMETB will now be responsible for quality assurance of training that leads to a CCT and visits must be conducted by a Board-appointed panel. A visiting panel must include a lay visitor, but not necessarily a trainee, and must be conducted under the Board's procedure. Approval will be at Deanery level with programmes or faculties being the primary components. A draft report template was first published in March 2005, this has been subject to revision and development. The College has had the opportunity to test in the field. A schedule of visits for the initial 6 months of the PMETB's existence has been agreed as a transition to potential new arrangements that were consulted upon in the late summer.

The other areas detail similar arrangements for work to be carried out on behalf of the PMETB for which the College will be remunerated.

Conclusion

The establishment of the PMETB is one of a number of initiatives for change in medical education that are currently emerging. Others include Modernising Medical Careers (Department of Health, 2003) and the European Working Time Directive (http://www.incomesdata.co.uk/information/worktimedirective.htm). Its role, responsibilities and membership is clearer than some. These educational initiatives are occurring at the same time as changes in service, such as payment by results, are likely to increase the tension between service and education. The specialty of medical education must develop at an increasingly rapid pace. Such questions as the relationship between service quality, patient outcome, patient safety and training will be asked and will require considered responses as the relationship of governance - educational, clinical and corporate - is explored.

The Board has a variety of potential positions. It must certify the completion of specialist training for all doctors including general practitioners, it must have clear processes for certifying equivalence under Articles 11 and 14. It has to act as a regulator across the entirety of medical education. It may act as an advocate for medical education in the potentially difficult times to come as the National Health Service fundamentally changes with foundation trusts, independent treatment centres and the above payment by results. It may act as a promoter of good practice in the field of medical education and thus greatly assist the necessary professionalisation of this activity. It must work in partnership with a vast range of professional and non-professional bodies, patients, public and politicians. The rhetoric of true partnership working will be tested to the full.

What then will the advent of the PMETB signify? It has arisen from the Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry wherein Kennedy expressed surprise that no single body held responsibility for the education and accreditation of doctors in the UK. The emergence of such a body represents a huge potential change. A number of questions need to be asked. The ambitions are high, there is a clear focus on outcome rather than process, and the time scales are less clear. The capacity and resource at not only PMETB but also at all levels in medical education will require robust definition if the potential benefits are to be realised. Unfortunately, failure to achieve may not result in a stand still position but could give rise to the very opposite of what is desired (and required), that is, a dilution and lowering of standards by marginalising those who have been crucial to their development and maintenance for many decades, such as the Royal Colleges.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.