A. The EU Rule of Law Crisis and the Need for Working Rule of Law Indices

In the past few years, the rule of law has been declining in many countries of the world, Footnote 1 including several Member States of the European Union. Footnote 2 The fear that more stable democracies could take such a turn is pervasive in public debate and scholarly discourse. Footnote 3 The study of legal rules, nevertheless, yields only partial insight into the state of the rule of law. In particular, in cases of erosion of the rule of law, the main problem is the slow demise of the normativity of constitutional law, that is, the growing chasm between the constitution and constitutional reality.Footnote 4 Amendments to formal legal acts say little about what and how things will change. If we do not want to remain blind to erosion, besides considering the formal rules, we must also examine the de facto conduct of addressees of these rules and the narrative accompanying it. The latter includes the social mentality or the political rhetoric regarding constitutional institutions. Footnote 5 Fine-tuned constitutional law doctrine is always capable of identifying a de facto breach of the general requirements of the rule of law by the addressees of constitutional rules. However, the question regarding the gravity of such breaches cannot be captured with the standard tools of legal doctrine alone. In order to fully grasp reality, one should also resort to rule of law indices.Footnote 6 Unfortunately, the existing rule of law indices, as we will see later in this Article, are not particularly helpful for the EU’s current needs for different reasons.

While we are not in a position to offer a miraculous solution to the EU rule of law crisis in this Article, we wish to point to an important and so far largely overlooked element to diagnose rule of law defects. In this Article we argue that rule of law indices, if well designed,Footnote 7 can be a powerful tool to detect ills in the rule of law of Member States. The introduction of the EU Justice Scoreboard (EUJS) in 2013 has already been an important step in order to lay the ground for an EU-wide analysis. It was primarily designed to address “the negative growth spiral” after the 2008 economic and financial crisis.Footnote 8 For this reason, the EUJS is currently too concerned with the financial guarantees and the infrastructure of the judicial system, instead of a holistic analysis of the rule of law. Since 2020, however, the EUJS also informs the Annual Rule of Law Report to be presented by the European Commission.Footnote 9 In this Article, we suggest how the EUJS should be further developed into a proper rule of law index because this would make the EUJS a considerably more useful tool in the EU rule of law crisis. The EUJS could not only play an important role in providing reliable data for political debates, but it could also inform the “Regulation on a general regime of conditionality for the protection of the Union budget”—which links the protection of the budget of the Union to the generalized deficiencies of the rule of law in the Member States— adopted on 16 December 2020.Footnote 10

B. Why Measure Legal Systems? The Use of Rule of Law Indices

There is a large number of indices that all measure legal systems.Footnote 11 This can be explained by four factors. First, one single number can easily sum up complicated questions,Footnote 12 so that non-professionals and the press can also use it.Footnote 13 We should not underestimate this explanatory character, because this simplification can also contribute to democratic accountability. Second, indices are often also considered as external measures in debates about evaluating reforms or the performance of the government.Footnote 14 Because of this, international organizations and NGOs use indices in order to foster and propagate best practices by comparing numbers of different countries. Exemplary countries usually score at the top of the scale set up by these organizations.Footnote 15 A side-effect of this approach can be seen, for example, when a government solely changes a policy in order to change its score on a scale, without treating the real problem.Footnote 16 Third, as already noted in our introductory part, rule of law indices can show the de facto situation—that is, law in action rather than law in books—they can also show the extent of improvements and deteriorations, and very importantly: These results cannot be discredited as “simply one opinion.” Rule of law indices aggregate a large number of data including many expert opinions—if done well—in a transparent and controllable way.Footnote 17 Fourth and finally, economists need quantitative data in order to test political-economical correlations, for example between the rule of law and economic performance, therefore, the characteristics of legal systems need to be quantified.Footnote 18

The challenge is that in all these cases we want to measure a phenomenon that is not directly observable, like the rule of law for example.Footnote 19 Fortunately, statistics has several methods to handle this, and over the coming pages we will present this approach, without delving too deep into the mathematical details. We focus on the measurement of the rule of law, but the fundamental methodological problems are similar in the case of other indices measuring legal systems too.Footnote 20

Quantification is not part of the traditional toolbox of a lawyer,Footnote 21 and the attitude of lawyers toward statistical methods is also ambiguous, to say the least.Footnote 22 On occasions they underestimate the indices because of the extent of simplification—or even discredit them, based on some unlikely outcomes—but at the same time they also admire the unintelligible mathematical models. In the present Article, we would like to find the golden mean between these two extreme approaches, by using the indices as important tools and as additional information for the better understanding of the overall view, while also treating them with precaution and critique.

A remark on terminology: By indicator we refer to a single number or feature, and by index we refer to composite indicators.

C. Methodological Steps

In this part we present the methodological questions based on the legal literature and on the OECD Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators (2008).Footnote 23 The main rule is that the design of the index must be transparent, and the methodological choices must be grounded, otherwise the indices are likely to serve pre-established policies.Footnote 24

First, we must note that some steps of index-building presuppose a thorough knowledge of legal doctrine, for example, conceptualization, and other steps require expertise in working with quantitative data, for example handling and aggregating data. As there are very few experts who excel at both fields, index-building is usually carried out via team-based work, based on the cooperation of legal experts and data experts, even if they sometimes speak entirely different languages.

I. Conceptualization

Before starting the construction of the index, we should clarify what we want to measure.Footnote 25 Babbie, quoting Kaplan, places measurable things into three categories: 1) Direct observables like the number of seats in a parliament, 2) indirect observables, like the minutes of corporate board meetings which only convey indirect information on what actually happened, 3) and constructs or theoretical creations, such as IQ, or government performance.Footnote 26 Lawyers have a special expertise in the latter field: one of the main parts of a lawyer’s work relates to conceptual analysis.Footnote 27 If we want to measure the rule of law, we have to define it.

The exact meaning of the rule of law as a term is, however, contested.Footnote 28 It is mostly defined as a list of requirements or legal techniques that aim at inhibiting the arbitrary use of state power.Footnote 29 Most characteristically, authors differentiate between formal-procedural (or thin) and material-substantive (or thick) requirements.Footnote 30 Somewhat simplistically, the formal-procedural side includes such aspects as the stability of legal rules, compliance, and fair enforcement, whereas the material-substantive side includes foremost fundamental rights, as well as checks and balances. It is not possible and not necessary to enter into debates over the meaning of the rule of law here.Footnote 31 Instead, taking into account the goal of our Article, we need to be aware of the structure of the concept as a list of requirements, and its anti-arbitrariness as a defining goal.

The various concrete definitions that are used by the various rule of law indices are usually based on legal-doctrinal opinions. If the majority of this legal-doctrinal professional community (constitutional lawyers of the relevant discourse, for instance) find the definition acceptable, for example, because it is based on authoritative legal documents, the definition seems to be appropriate.Footnote 32 We can, of course, encounter numerous terminological debatesFootnote 33 about the concept of the rule of law, and because of the contested nature of values, we cannot expect a full consensus on this matter.Footnote 34 The general advice, however, is that we should use a mainstream definition—when possible—with a small grain of caution. Because of the contested nature of the concept of the rule of law, the difficult task of finding a “common” opinion among experts can be shortcut by reference to official documents, for example, by the EU, the UN, the Council of Europe, or the European Commission.

Consequently, some indices diverge concerning the exact definition used, a problem that we will discuss later. Legal indices usually measure the de facto characteristics of a system, so a wellcrafted and substantively appealing law with a corrupt, oppressive, or ineffective implementation will underscore on these scales.Footnote 35

II. Selecting Data

Once it is clear what shall be measured, the data for this measurement has to be found. The quality of a given legal system cannot be measured directly. Therefore, proxies (approximate data) have to be used: The opinion of experts or that of the public—soft data—or approximate facts—hard data—for example, the number of registered crimes, the budget of the courts, frequency of the modification of laws, frequency of the condemnation of a State by an international court of human rights.Footnote 36

The main concern about expert opinions is the choice of experts and the subjectivity of their opinions. This is an especially sensitive problem in politically polarized countries.Footnote 37 As a partial remedy a transparent selection method is preferable. For instance, in a country with inter-ethnic tensions, the proportion of the experts should reflect the overall ethnic distribution. Alternatively, the use of as many experts as possible, by random sampling or with the participation of every available expert, is an appropriate way to address the challenge of selecting experts known as selection bias.Footnote 38 A further problem is that in case of general questions, which is often characteristic of legal indices, it is not easy to find an expert who is up-to-date in every field. For example, criminal procedure, which is an important constituent of the rule of law, is usually not well known by constitutional lawyers.Footnote 39 In several countries, participation brings risks for the expert too, if for example, he or she criticizes the current regime, even if anonymity is granted, obtaining unbiased reports will be more complicated.Footnote 40 However, an obvious advantage of acquiring an expert opinion is that wide opinion polls are expensive, hard data are not always available from every single country, and some questions can only be answered by experts.

An important advantage of using opinion polls in the general population is that they also takes into consideration the situation of vulnerable groups. Even though opinion polls can also be biased, if they are professionally taken then the situation of these groups can be better represented than in expert opinions and in hard data. A further advantage of survey data is that it can also enlighten the differences between hard data and reality.Footnote 41 Unfortunately, however, opinion surveys are expensive, and the questions are limited—as the general population cannot answer very specific questions. Sampling and measurement in no-go zones (in European countries it is less of a problem) and among vulnerable groups is also complicated. Public opinion is also very fluid, especially if it is influenced by the news.Footnote 42 A further critique is the limited possibility of cross-country comparison, due to divergent historical mentalities.Footnote 43

Although the use of hard data is objective, the scope of measurement is very limited. A large proportion of our questions cannot be measured even by using proxy hard data. It can also occur that while something is measurable by hard data, there is no data from a given country. We must also be cautious when using available data for four reasons: 1) Sometimes they are corrupted by the authorities, for example, the police sometimes discourage the victims of small crimes where there is a limited probability of success, in order to ameliorate statistics. 2) Sometimes, the measured value has an impact on the question only in extreme cases, for example, the budget of courts on the rule of law. 3) And sometimes, it is not at all obvious whether a boost of an objective value has a positive or a negative effect on the phenomenon—the high efficacy of public prosecutors can be indicative of an authoritarian judiciary tradition, while low efficacy can be indicative of incompetent prosecutors. 4) Finally, the partial nature of the data, in other words, objective data is only available on certain special questions, not on all questions which can lead to arbitrary selection.

Some indices combine the different sources, making the results more robust, see for example, the WJP-Index below, and the data sources are also cross-checked, via a method known as triangulation.

III. Statistical Analysis

There are different types of data: yes or no (binary data: 1 or 0), points on a given scaleFootnote 44 (ordinal data, for instance, the experts of the Freedom House evaluate the questions on a scale ranging from 1 to 7), percentages (metric data, for example, trust in institutions in the Eurobarometer), etc. In order to put all the data in one final index, we have to normalize (homogenize) them.Footnote 45 For cross-country comparison, we have to adjust the data according to the size of the given country.Footnote 46

There are several statistical methods for dealing with missing data. We can simply delete the whole row of data, for instance if an expert only answers twenty-four out of twenty-five questions, we can delete all of his or her answers, or we can just leave out the unanswered question. The problems are that: 1) The missing data are usually non-random, for example, some experts are afraid of answering several questions—in this case, simply disregarding the missing answer can bias the result; 2) deleting data can also decrease the reliability of the result—that is an increasing standard error.Footnote 47 Therefore, if the quantity of missing data is more than five percent, we can use imputation.Footnote 48 If, for example, an expert answered only twenty-four out of twenty-five questions, we can deduce her or his twenty-fifth answer by imputing this answer based on the other answers given by the expert. Or we can use the mean of the answers of the other experts, eventually belonging to the same cluster, based on the similar answers. We can also use a variety of other, more complicated statistical methods, and while each of these methods has a different advantage and inconvenience, we can reduce the bias of the outcomes based on these methods.

We must separately examine the non-arbitrary selection of the indicators, on which the indices are based.Footnote 49 Indices based on many but bad indicators—meaning indicators which are actually irrelevant for the concept to be measured—are called “indicator rich but information poor.”Footnote 50 We can test this issue by using multivariate analysis. We examine the relation between the indicators, and the effect of them on the final outcome, in other words on the value of the rule of law index. Besides, we always have to test the influence of the individual variables on the final outcome, in other words, examine the robustness.Footnote 51

We must also deal with outliers, meaning, the observations distant from other observations. In many cases, these result from measurement errors. Here too, we can use several statistical methods to handle the problem: We can simply delete the values, use imputation techniques, or introduce a natural logarithm, for example, to increase the goodness of fit. Of course, there are some real outliers too. We have to take them into consideration.

Weighting is an important question too. On the one hand, we can sum up the data with the same weight, but some characteristics are more important than others, for instance, concerning the rule of law, it is more important that the police cannot shoot innocent civilians arbitrarily, than the duration of a legal procedure.Footnote 52 On the other hand, it is not easy to find an objective method for weighting—due to a lack of knowledge, and consequently, due to a lack of consensus between experts.Footnote 53 When testing indices without weight, using multivariate analysis, we are only able to change them by adding or deleting indicators. In the case of weighted indicators, we can change the weight too, without deleting the indicator. The underlying method of weighting must be clear and explicit too.Footnote 54 In several cases, weighting can be implicit too: If for instance, we build in strongly correlated indicators into the index, this also results in the weighting of the given question.

In order to lower the influence of extreme values on the final index (considering the example above: in order to avoid overscoring legal systems where the police can kill innocent people, but where other institutions are working well), we can use a geometric mean instead of an arithmetic mean. This allows for greater comparability, that is the state with the arbitrary police but with a good performance on other scales will not perform better than a similar (slightly underperforming) state without such an extreme value.Footnote 55 Instead of using means, we can also use factor analysis, but the description of this method is beyond the framework of the present study.Footnote 56

We can also build sub-indices from indicators. This is useful because 1) it can diminish misunderstandings and biases, occurring in the case of using isolated indicators, and 2) we can measure the complex and multi-faceted characteristic of the institutional functions.Footnote 57 We can even build dimensions from sub-indices. These are on a higher level of abstraction than the indicators, but on a lower level compared to the final index—for example, in the case of the rule of law, the efficiency of the justice system, or that of the police. We also can statistically test the relation between the dimensions,Footnote 58 also in order to measure the effect on the final index. Here we can use factor analysis as well or principal component analysis or Cronbach’s alpha test.Footnote 59 Thereafter, we can correct the list of indicators, or the weights and the classifications into sub-indices, so that they measure similar but not identical things, with an existent but not full correlation. While building up the final index, we have to allow for the possibility of decomposition too, so that we can deduce from it the basic data and indicators.Footnote 60

IV. Presenting, Interpreting, and Comparing Results

The results are better represented in charts, but textual information is also needed for their interpretation. We have to keep in mind that the numbers in themselves can only represent the correlation.Footnote 61 In order to establish a causal relation on the basis of this, the content needs to be considered further.

Visualization of the results with graphs, for example, can be instructive, too. These can influence (or manipulate) the interpretation and understanding, too.Footnote 62 The results of an analysis extended to multiple countries can be represented on a map, or the countries can be classified into clusters. If there are other indices on the same question, we should compare them with our index, and we should also explain the differences.

D. International Indices on the Rule of Law

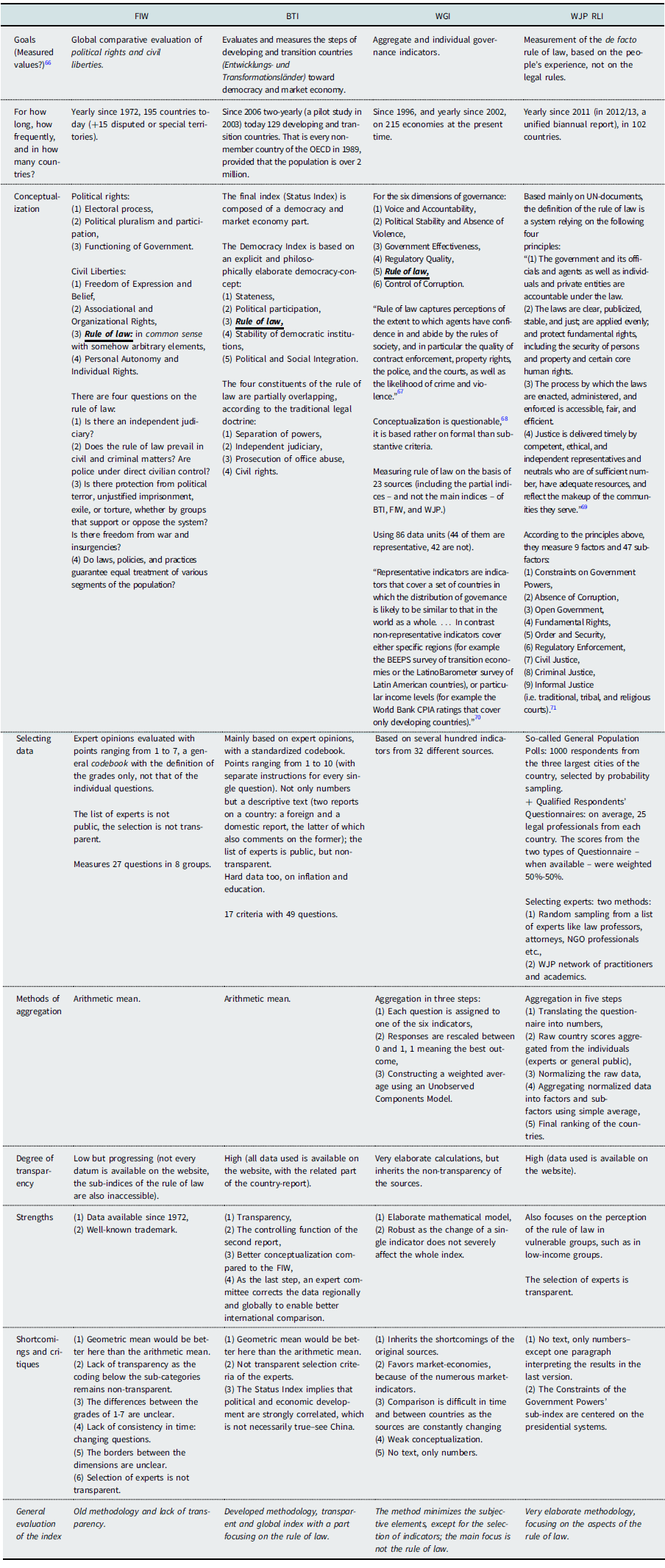

Here, we present four internationally recognized indices on legal systems.Footnote 63 These are the indices of the Freedom House (“Freedom in the World,” FIW), the Bertelsmann Stiftung (“Bertelsmann Transformation Index”, BTI), the World Bank (“Worldwide Governance Indicators,” WGI), and the World Justice Project (“Rule of Law Index,” WJP RLI).Footnote 64 We have chosen these four indices because they are internationally the most well-known ones, and their critical analysis is also helpful for improving the EUJS. In order to give a clear-cut picture, we represent the similarities and differences in a chart.Footnote 65 In the four indices, we also present the measurement of the rule of law, in order to point out the differences in conceptualization.

The Freedom House index—although it deserves praise for pioneering work, having been established already in 1972 and its almost universal coverage—is methodologically a dinosaur (unclear conceptualization, questions are partly overlapping, partly lack coverage; even the simple awareness of methodological problems seems to be missing). It also fundamentally lacks transparency, as, for instance, it is unclear who the experts are and how they are chosen.

The Bertelsmann Transformation Index, in contrast, features a sophisticated methodology. The transparent and global index also elaborates on democracy with a part focusing on the rule of law. However, for our purpose, the index is troublesome, as it does not include western European countries and thus, does not provide for an EU-wide standard which, however, is an indispensable prerequisite in order to measure the rule of law in all EU Member States with regard to Article 2 TEU in the EU. Using the BTI would bear the danger of double standards accusation, and rightly so. Nevertheless, the improvement of the EUJS could profit from the methodology of the BTI.

Similarly, the index of the World Justice Project is also a methodologically sophisticated project. Yet, the WJP index explicitly states that time series cannot be built based on it, as the questionnaire of the index is slightly changing year by year. This is a severe limitation. Nevertheless, if an index has the limitation of providing only static information—instead of displaying evolutionary developments—we can still compare the results of the various EU Member States, and we can also compare it to static benchmarks.

A virtue of the Worldwide Governance Indicators of the World Bank is that it minimizes the subjective elements, except for the selection of indicators, some of which, however, are only available for money. The main focus is, however, not on the rule of law, and the results stem from other indices and indicators, therefore the WGI necessarily inherits the methodological problems of the original indices and indicators that it aggregates. A further problem is that the countries are given a “percentile rank,” which means that a country can easily “improve” in the ranking if many other countries deteriorate in the actual absolute quality of the rule of law values; or the other way around: It can place lower in the ranking if many other countries actually improve their quality of the rule of law.

E. How to Develop the EUJS into an Index that can be Applied in the EU Rule of Law Crisis

I. The Unsuitability of Existing Indices for the EU Rule of Law Crisis

The assessment of the existing indices above has shown that none of them are—albeit for different reasons—suitable for replacing the EUJS as they stand. While the Freedom House Index is outdated, the Bertelsman Index simply does not cover the EU Member States. The World Justice Project’s methodology changes over time and therefore, does not allow an assessment of changes of the rule of law. The Worldwide Governance Indicators are not suitable either, as some Member States’ results might look deceptively improving—without an actual improvement—due to the nature of the percentile rank of this index.

Finally, a generic legitimacy problem for the the EU with all mentioned indices is that they are done by external bodies. The EU should be able to set its own official standards, and not just rely on partly US-based NGOs. This NGO-objection does not apply to WGI. Before we can look into how to improve the EUJS, informed by the presented indices’ strengths, we will look at the EUJS’ current state of affairs.

II. The EUJS as it Stands

The EUJS is an initiative from the European Commission which was presented for the first time in March 2013.Footnote 72 Since 2013, annual reports are published on the independence, quality, and efficiency of justices systems of EU Member States.Footnote 73 The 2020 EUJS “will also inform the Annual Rule of Law Report to be presented by the European Commission.”Footnote 74 It is, therefore, our proposal to further develop the EUJS into a rule of law index that should actually meet this new planFootnote 75with a specific section devoted to judicial independence.

The data for the EUJS largely stems from the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) of the Council of Europe (CoE).Footnote 76 The CEPEJ was established in 2002 and uses some 170 qualitative and quantitative indicators on the efficiency and quality of justice.Footnote 77 It is composed of 47 experts from all CoE Member States.Footnote 78 Further, the data is received from national contact persons and a range of other sources.Footnote 79

This plethora of sources is an issue of concern as various sources increase potential shortcomings, and a homogenous dataset cannot be guaranteed.Footnote 80 Especially the heavy reliance on data from CEPEJ reports, which in turn bases its information on a questionnaire often answered by national correspondents within the ministries of justice, does not provide for objective data.Footnote 81 Criticism extends to the informal “group of contact persons on national justice systems” which is an expert group of the Commission, established in 2013.Footnote 82 Also, this group is comprised of officials of Member States, namely one person from the judiciary and one from the Ministry of Justice. Beyond that, this group must be criticized for a lack of transparency.Footnote 83 Furthermore, the data gathered from the European Network of Councils for the Judiciary (ENCJ) depends on the basic functioning of the Member States’ rule of law. The substitution of independent judges with party loyalists obviously infiltrates such national sources of data too. Finally, the lack of some data due to the reluctance of some Member States to provide the data is a serious shortcoming of the EUJS,Footnote 84 which is a consequence of the design choice to request the data from the Member States—instead of generating the data independently by using experts.

The EUJS originally had a very limited scope and was designed as a general information tool that enhances the effectiveness of Member States’ justice systems. It is only since 2020 that the EUJS shall also provide information on the state of the rule of law in the EU Member States.Footnote 85 This becomes crucial as current Commission President von der Leyen has also announced a new European rule of law mechanism which requires annual reports on the state of the Rule of Law across the EU.Footnote 86 On September 30th 2020 the first Annual Rule of Law Report consisting of country specific qualitative analyses has been published by the European Commission.Footnote 87 Indeed, the aim “to strengthen common values and the rule of law”Footnote 88 also featured very prominently as a top priority of the Finnish presidency.Footnote 89 While the European Parliament has urged to establish an EU mechanism for democracy, the rule of law, and fundamental rights already, in June, 2015,Footnote 90 it now seems that the European Commission understands the urgency of the situation and has initiated such a European mechanism.Footnote 91 While this Rule of Law Report consists of a country-specific qualitative analysis of the major developments in Member States, according to Didier Reynders, current European Commissioner for Justice, it shall “benefit[…] from the quantitative analysis of the Scoreboard where the reader can zoom in on national justice systems and information about their independence, quality and efficiency.”Footnote 92 In addition to previous editions of the EUJS, and “in response to the current need for more comparative information for the annual Rule of Law Report and for the monitoring of the National Recovery and Resilience Plans” the Commissioner states that “this year’s edition goes further. There are new indicators on the digitalisation of justice systems, on the independence of national supreme court judges, on the autonomy of prosecution services and on the independence of lawyers and bars.”Footnote 93

Despite this rather optimistic trend, there is still a pressing need to methodologically equip the EUJS in order to serve its important purpose. So far, the EUJS still is a rather limited tool focusing on so-called hard data without delving into a deep analysis of the context and background of the rule of law. It focuses on, for example, the “efficiency of justice systems” by looking at the caseload and estimated length of proceedings, or the assessment of the “quality of justice systems” by the criteria of accessibility to justice systems and adequate financial and human resources.Footnote 94 This is problematic, as thereby, the EUJS misses what we described above as an essential element of the rule of law—the informal aspect of “law in action”. Therefore, while we do not claim that all the criteria in the current EUJS are meaningless, it is nevertheless necessary that the EUJS extends its scope by actually measuring judicial independence and further important benchmarks of the rule of law. Instead of only highlighting basic features and figures of a justice system.Footnote 95

The EUJS, as it stands, only measures whether a justice system is generally capable of delivering justice. It does not measure, however, whether it is actually working as an independent judiciary. Consequently, the outcome of the EUJS for a specific Member State might well be a high justice score, as the justice system is well equipped with staff and computers, despite actually not guaranteeing the rule of law due to arbitrary and biased results. Therefore, the EUJS cannot detect whether a Member State actually does not want to guarantee an independent rule of law. Or to put it directly, bad justice can be very effective. And while “the 2020 EU Justice Scoreboard shows updated indicators in relation to legal safeguards on the disciplinary proceedings regarding judges,”Footnote 96 it is rather misleading to include figures on the “perceived independence of courts and judges among the general public”Footnote 97—particularly when thinking of biased media—instead of referring to expert opinions.Footnote 98 This verdict still holds true despite the improvements made in the EUJS 2021 referred to above by Commissioner Reynders.Footnote 99

In addition, the focus of EUJS does not meet the broad understanding of the rule of law report published by the Commission. While the latter acknowledges the importance of informal rules for the rule of law, the former relies on formal rules:

The guarantees of structural independence require rules, particularly as regards the composition of the court and the appointment, length of service and grounds for abstention, rejection and dismissal of its members, in order to dispel any reasonable doubt in the minds of individuals as to the imperviousness of that court to external factors and its neutrality with respect to the interests before it.Footnote 100

Surprisingly, the EUJS openly admits this shortcoming: “The figures presented in the Scoreboard do not provide an assessment or present quantitative data on the effectiveness of the safeguards. They are not intended to reflect the complexity and details of the safeguards. Having more safeguards does not, in itself, ensure the effectiveness of a justice system.”Footnote 101 Addressing this directly, we disagree with this self-imposed limitation. This actually unnecessarily limits the performance of the EUJS for its newly found purpose to inform the Commission and other EU organs on the actual state of affairs of Member States’ justice systems concerning the rule of law. Rightly, the 2020 and the 2021 EUJS state that “[u]ltimately, the effective protection of judicial independence requires a culture of integrity and impartiality, shared by magistrates and respected by the wider society.”Footnote 102 This can be depicted in a proper rule of law index. How this can be done, will be dealt with in the next section.

As the institutional shell of the EUJS already exists, it offers a chance of developing into something more useful in the current rule of law crisis: a rule of law index.Footnote 103 In the current shape, the EUJS is, similarly to other actions taken by the EU in the rule of law crisis, more a Sisyphus-like exercise, instead of a serious and reliable tool to measure the rule of law.Footnote 104 As another illustration of this rather harsh critique, we would like to point again to the 2019 EUJS which refers to “[t]he importance for Member States to ensure the independence of national courts, as a matter of EU law.”Footnote 105 However, instead of basing a lack of independence on the findings of the EUJS, the report has to refer to “the recent case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union.”Footnote 106 In this vein, the report points for instance to the fact that “the Court has clarified that the requirement of judicial independence also means that the disciplinary regime governing those who have the task of adjudicating in a dispute must display the necessary guarantees in order to prevent any risk of it being used as a system of political control of the content of judicial decisions.”Footnote 107 The 2020 EUJS did not change that. While the 2021 EUJS “contains new indicators on authorities involved and status of candidates for the appointment of Supreme Court judges”,Footnote 108 these new figures do not display actual independence of judges.Footnote 109 The EUJS still is not an adequate tool to address the rule of law crisis.

III. The Steps Necessary to Improve the EUJS

So what shall be done? How could we improve the EUJS? The best examples for our purposes are BTI and the WJP. We should therefore approximate the EUJS to those indices.

1. As we have seen, the main advantage of the rule of law indices is that they can aggregate a list of data into a single number—or a few numbers. So far, the EUJS cannot offer a single numerical value that would inform us about the rule of law in the Member States. Viviane Reding stated that the EUJS “is not a beauty contest. It’s not about ranking national justice systems.”Footnote 110 Whereas it is true, that the main purpose is not to make a ranking, without a single number, the EUJS remains a half-hearted effort, and thus, merely a pretended action in the rule of law crisis. A ranking is just a side-effect of the overarching final numerical values—the index. It is nevertheless an essential tool. If the EUJS does not provide clearcut figures based on a sophisticated conceptualization, for instance, journalists will do so—without a defendable concept. The most recent rule of law report from the Commission has been scanned for how often the terms “concern” and “serious concerns” appeared in each country’s report on a specific Member State. This leads to a Member State ranking.Footnote 111 It is of utmost necessity to clearly highlight if a Member State does not fulfill the requirements of the rule of law—and we also need to know by how much it falls short. All Member States have the obligation to guarantee Article 2 TEU values. The equality does not extend to severe shortcomings on which we must turn a blind eye just for the sake of keeping everyone happy. There is no way around this uncomfortable truth.

2. Independent expert opinions should be the primary data source for the EUJS.Footnote 112 The obsession of EUJS with hard data, such as the length of proceeding, is a dead end. Qualities of a legal system cannot be measured based solely on hard data. It is not enough to only include surveys of the general public and companies on the independence of the judiciary—which is albeit not detrimental—in the EUJS either. In addition, especially in countries with the rule of law issues, it is also questionable whether the information, hard data, provided by the respective government is reliable. To improve the EUJS significantly, it would be important to include expert opinions, similarly as in the case of all rule of law indices—the WGI is using secondary data, some of which are based on expert opinions. As for the experts, their selection should focus on credentials that ensure independence: For example, scholarly achievements, if there are no doubts about the independence of the judiciary—higher judicial position, or alike.

3. Many questions that we are interested in cannot be answered based on hard data, for which the EUJS seems to have a very strong preference; maybe because it wants to look “objective.” Rule of law indices are not “objective” in the sense that the results would emerge automatically from the data.

3.1 First of all, we need to clarify what we want to measure, and to do this, we must make certain conceptual choices. These conceptual choices have to be justified. The WJP and BTI both made sophisticated conceptual choices. They clearly lay out what they mean by the “rule of law.” This groundwork is missing for the EUJS. You can either borrow the conceptual choices from the two named indices, or you can develop a new, probably very similar, one based on the treaties, especially Art 2 TEU, further EU documents such as the most recent 2020 Commission report on the rule of law, and case law of the CJEU. This is not particularly complicated—as the goal is not to come to terms with the one and only perfect solution, but a working concept. It is also doable in a couple of months with a number of experts and scholars. Even the Venice Commission, or the CEPEJ, can be involved, or their past documents can be used for this purpose.Footnote 113

Therefore, the major shortcoming of the EUJS—in contrast to the most promising methodologically designed Bertelsmann Transformation Index—is the following: although the EUJS has been established in the wake of the already ongoing EU rule of law crisis, its current objective is not appropriate for providing valid data in order to make conclusions about the true quality of the rule of law in the EU Member States. The EUJS “focuses on litigious civil and commercial cases as well as administrative cases in order to assist Member States in their efforts to create a more investment, business and citizen-friendly environment.”Footnote 114 This does not track what is actually problematic. To put it bluntly, instead of statistically displaying the availability of computers to national courts, it would be important to measure the independence of the judiciary, not in the perception of the general public or companies, but by the assessment of independent experts,Footnote 115 or even more the quality of the rule of law writ large.

Consider this example: According to the 2019 EUJS, “the 2018 European Semester, based on a proposal from the Commission, the Council addressed country-specific recommendations to five Member States relating to their justice system.”Footnote 116 These five Member States did not include Hungary or Poland but rather included Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Portugal, and Slovakia.Footnote 117 This is noteworthy as the EUJS itself is meant to inform the European Semester. And indeed, this changed, as in “the 2020 European Semester, the Council, on Commission’s proposal, addressed country-specific recommendations to eight Member States relating to their justice system,” namely Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Portugal, and Slovakia.Footnote 118

3.2 The method of aggregation should necessarily be based on certain choices, which need to be made on the basis of conceptualization. Sometimes there are several possible ways, but one must be chosen, and reasons must be given for the choice. Again, transparency is key.

3.3 The experts that will deliver the opinions should be numerous, and they should be selected in a transparent way. The selection method of WJP is that experts, who are unpaid, are selected on a random basis from very large lists, including all members of the bar, whereas each selected expert should have the possibility of recommending new ones. The V-Dem Project, specialized on measuring democracy, has a country coordinator for every country who selects experts—who are offered a small amount of payment—based on predetermined criteria. There are different ways to make the selection of experts, but in any case, this needs to be done in a transparent way. You can also call these experts the “Copenhagen Commission” if you prefer.Footnote 119

F. By Way of Conclusion: Limitations and Perspectives of an Improved EUJS

It is important to acknowledge that quantifiable findings in themselves cannot provide the basis for automatic action.Footnote 120 Instead, the results need to help prudent doctrinal analysis by providing weights to violations of the rule of law requirements. An improved EUJS could also play a more central role in the political discourse, helping in agenda-setting and it could pressure recalcitrant Member States, and those politicians from other countries who try to defend the indefensible for reasons of party alliances.Footnote 121 It could help to determine whether a “serious and persistent” breach of the rule of law exists according to Article 7(2) TEU and help courts in finding whether “general or systemic deficiencies” in the rule of law of a Member State are present.Footnote 122

Reliable data can also inform the “Regulation on a general regime of conditionality for the protection of the Union budget” which has been adopted on 16 December 2020.Footnote 123 For instance, the principle of a proportionate financial measure enshrined in the new EU rule of law mechanism could be informed by an improved EUJS drawing on rule of law indices. Thereby, the sensitive matter of determining the amount could be supported also by quantitative data. This is important, because the Commission will face high political pressure when acting under the new rule of law mechanism. Having the possibility to rely on an improved EUJS which presents clear data on rule of law breaches in EU Member States based on independent expert opinions, would significantly strengthen the position of the Commission against charges of politically motivated action.Footnote 124

Proper measurement of the rule of law at the EU level is necessary because arguably all current governments of EU Member States will claim that they actually follow the rule of law standards in their respective countries. This, however, is doubtable, to say the least. An EU-wide index can provide for very valuable and largely neutral, or at least with respect to the EU Member States, comparable data on such claims. In order for the EUJS to accomplish such a task, the above-suggested improvements are necessary.