The Novallas Bronze, datable to the second half of the 1st c. BCE, preserves part of an important document composed in the Celtiberian language but written using the Latin alphabet. Its discovery has provided new data that have produced a radical shift in our understanding of the process of dissemination of the Latin alphabet and language among the Celtic populations of inner Spain.Footnote 1

We currently know of almost 500 Celtiberian inscriptions, although this number is reduced to some 200 if we eliminate from the calculation those pieces with such short texts that they scarcely offer linguistic information.Footnote 2 The majority of those documents use the so-called Palaeohispanic script, a particular system of writing derived from the Phoenician abjad which, around the 8th c. BCE, was adopted by the Tartessians (who were settled around the mouth of the Guadalquivir River) and later spread among various populations in the south and east of Spain.Footnote 3

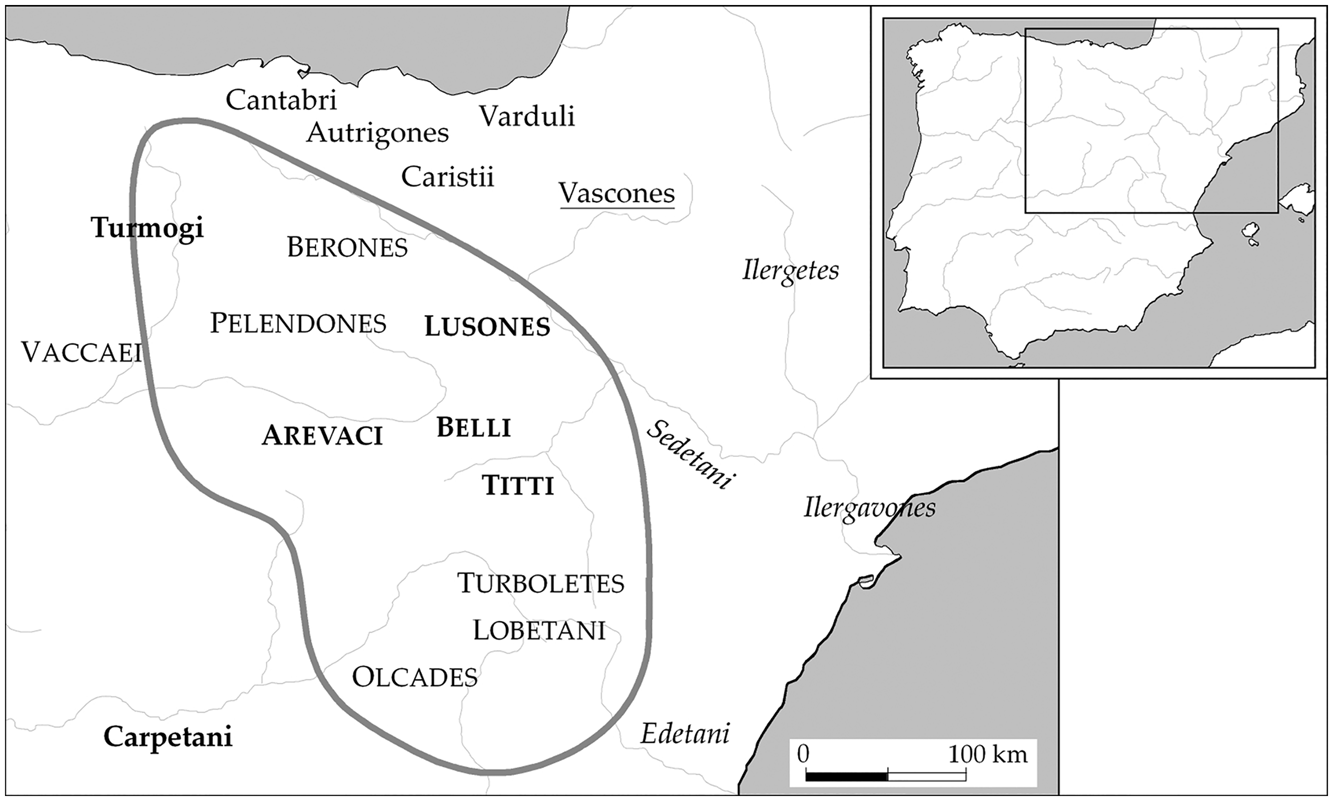

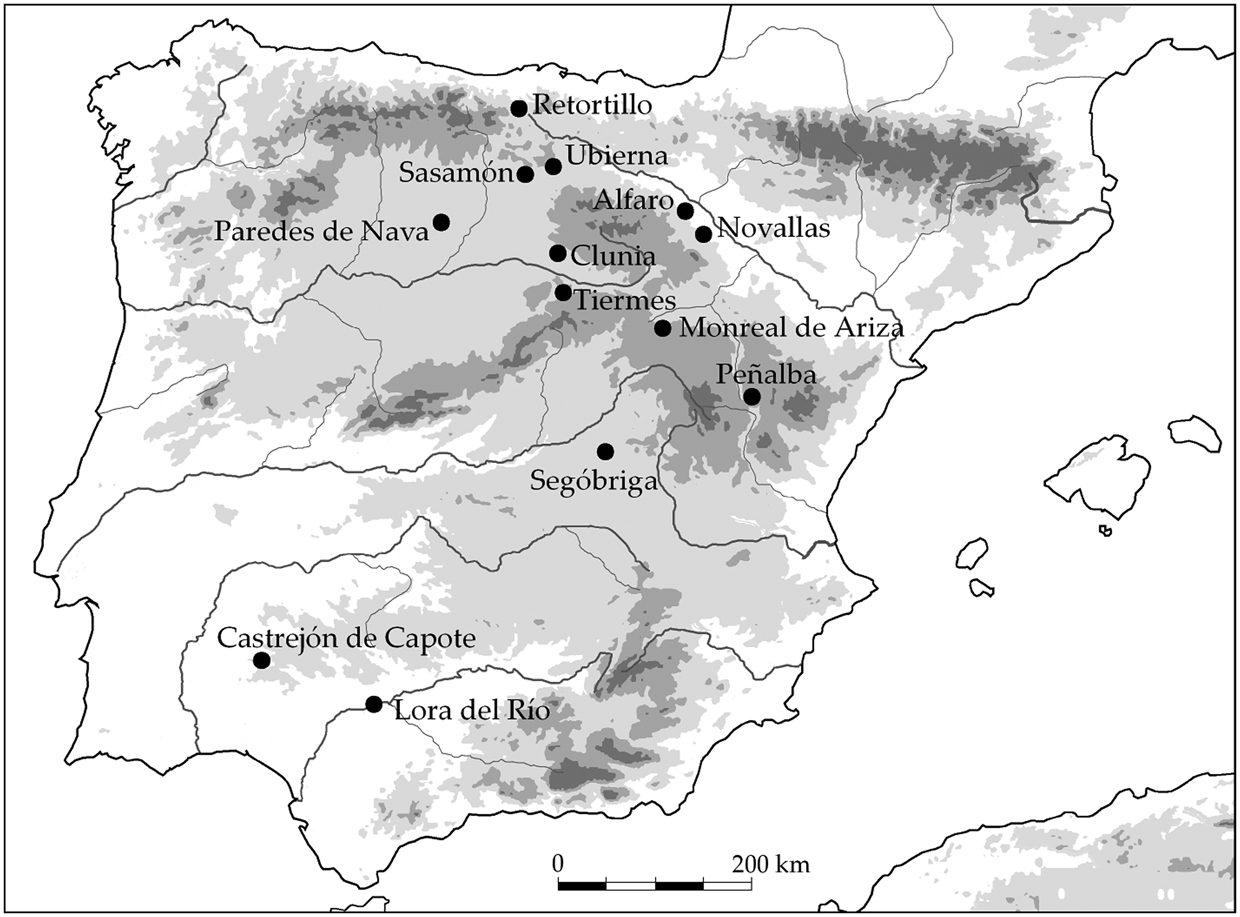

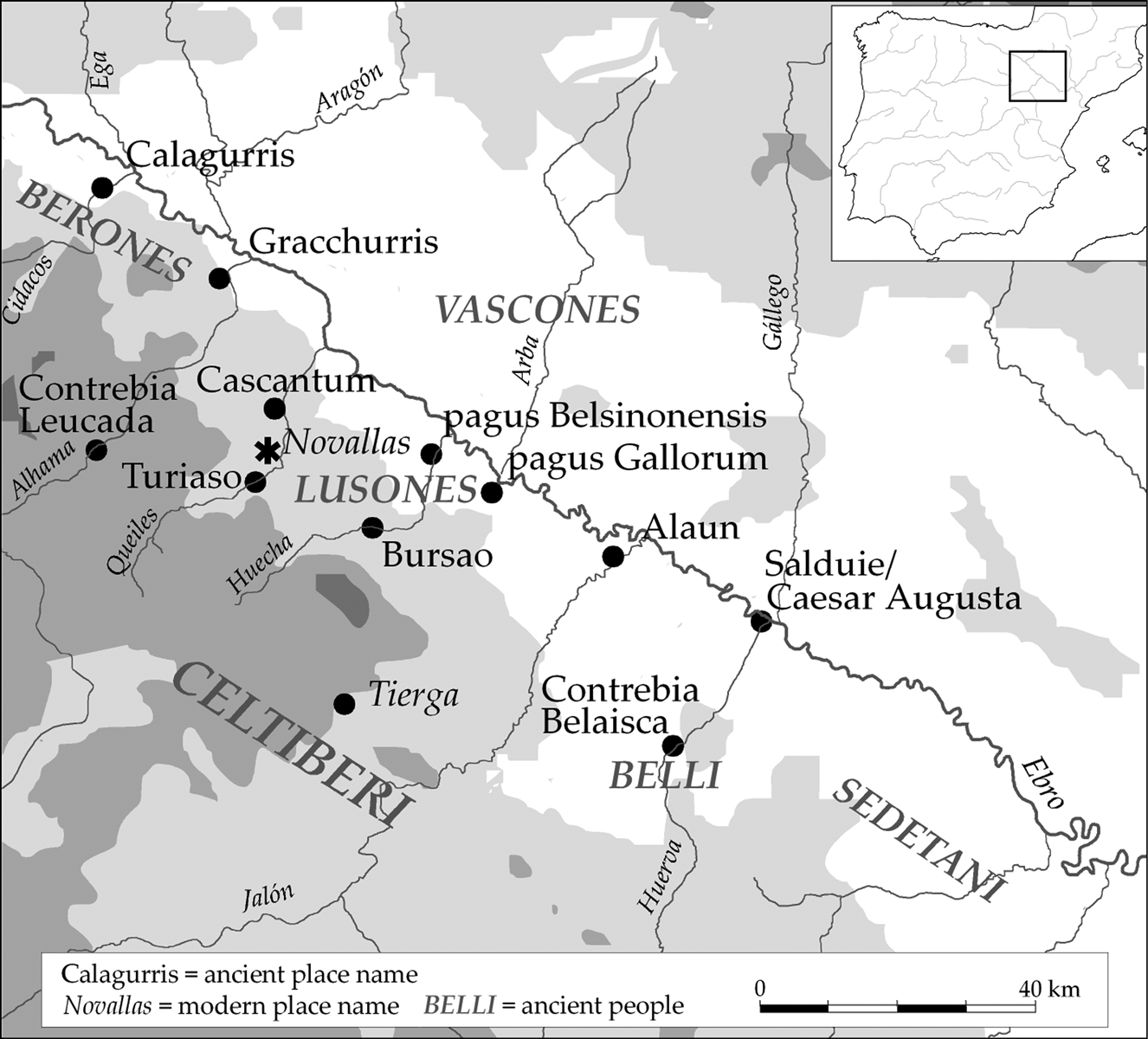

It is likely that the Celtiberians adopted the Palaeohispanic script, in its east Iberian version, as early as the 3rd c. BCE, although the majority of Celtiberian inscriptions can be dated to the late 2nd and 1st c. BCE. The script's distribution corresponds to the territory occupied by peoples whom ancient authors identified as “Celtiberi,” an exogenous term created perhaps by the historian Fabius Pictor, with the meaning “Celts of Iberia” (Fig. 1).Footnote 4 The term refers to the peoples of Celtic language who settled around the Iberian System mountain range near the headwaters of the Tagus, Douro, and Ebro rivers, and against whom the Romans fought fiercely throughout much of the 2nd c. BCE.Footnote 5 It is likely that other peoples in the interior of Spain, especially from the northern Meseta and the Cantabrian coast, spoke languages very close to that documented in the Celtiberian inscriptions. Unfortunately, however, their use of writing was rare, so we have very little information available on the subject.Footnote 6

Fig. 1. Celtiberian-speaking area according to the findspots of written documents and names of autochthonous peoples in northeast Spain according to various sources. Bold, uppercase letters (e.g., Belli) indicate Celtiberian peoples mentioned in ancient literary sources. Plain, uppercase letters (e.g., Pelendones) are peoples considered Celtiberians only by some ancient authors. Bold, lowercase letters (e.g., Carpetani) are other Celtic-speaking peoples. Names in italics (e.g., Sedetani) are Iberian-speaking peoples. Vascones: Vasconic-Aquitanian-speaking people. (Drawing by M. C. Sopena.)

Celtiberian epigraphy includes not only private texts, such as inscriptions on pottery and small objects, but also documents that were official and/or intended for public display – in particular, some epitaphs,Footnote 7 coin legends,Footnote 8 tesserae hospitales,Footnote 9 and, especially, inscriptions on bronze tablets.Footnote 10 Despite the Celtiberian inscriptions’ distinctive character, practically all of them postdate the Roman conquest and are inspired to a greater or lesser extent by Roman models. For this reason, Celtiberian epigraphy should paradoxically be considered an early example of Romano-provincial epigraphic culture.Footnote 11 Within the repertoire of Celtiberian inscriptions, there is a small group of documents that were written using the Latin alphabet.Footnote 12 It is to this limited collection of documents that the Novallas Bronze should be added, and it is, in fact, the longest of all the Celtiberian-Latin texts known to date.

Discovery and description

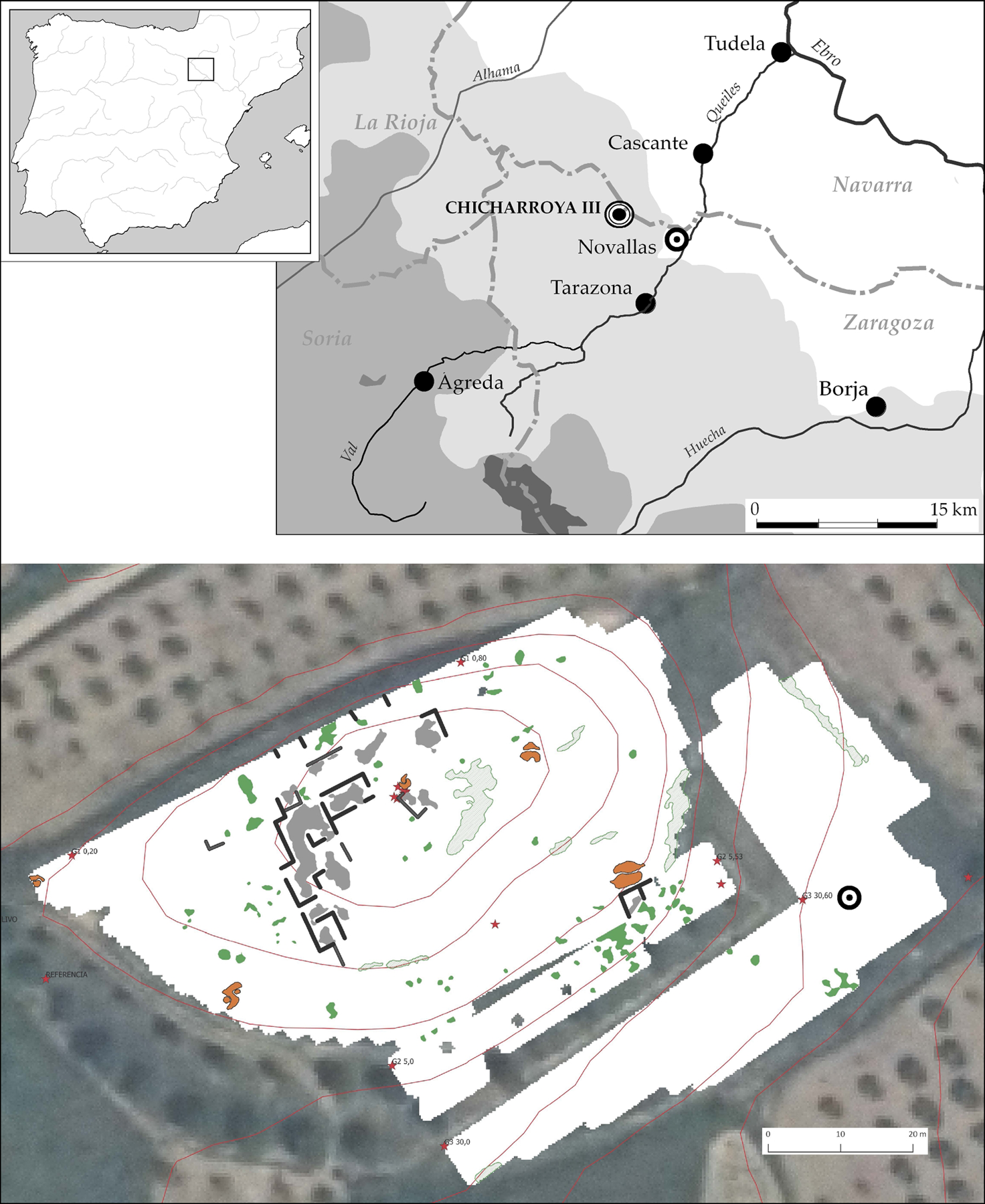

The Novallas Bronze was discovered by chance in the early 21st c. at the Chicharroya III site (Fig. 2), which is in the district of Novallas (Zaragoza). Several archaeological excavations were subsequently undertaken on the site between 2017 and 2019, which led to the discovery of different structures devoted to wine production and associated with a Roman villa in use from the middle of the 1st c. CE until the Late Antique period.Footnote 13

Fig. 2. Location of the archaeological site of Chicharroya III and plan of the remains of the Roman rural villa. The circle at center right shows the approximate findspot of the bronze. (Drawings by M. C. Sopena and H. Arcusa.)

The research undertaken on site confirms that the zone in which the Bronze was found has been obliterated by recent agricultural work, which means that no archaeological strata have been preserved intact. In any case, the site has not provided evidence of occupation earlier than the middle of the 1st c. CE. This fact suggests that the Novallas Bronze arrived at the villa of Chicharroya III to be reused once its original function was obsolete, as occurred, for example, with the Agón Bronze – dated rather later – which was also recovered in a rural settlement where it was to have been melted down in order to reuse the metal.Footnote 14

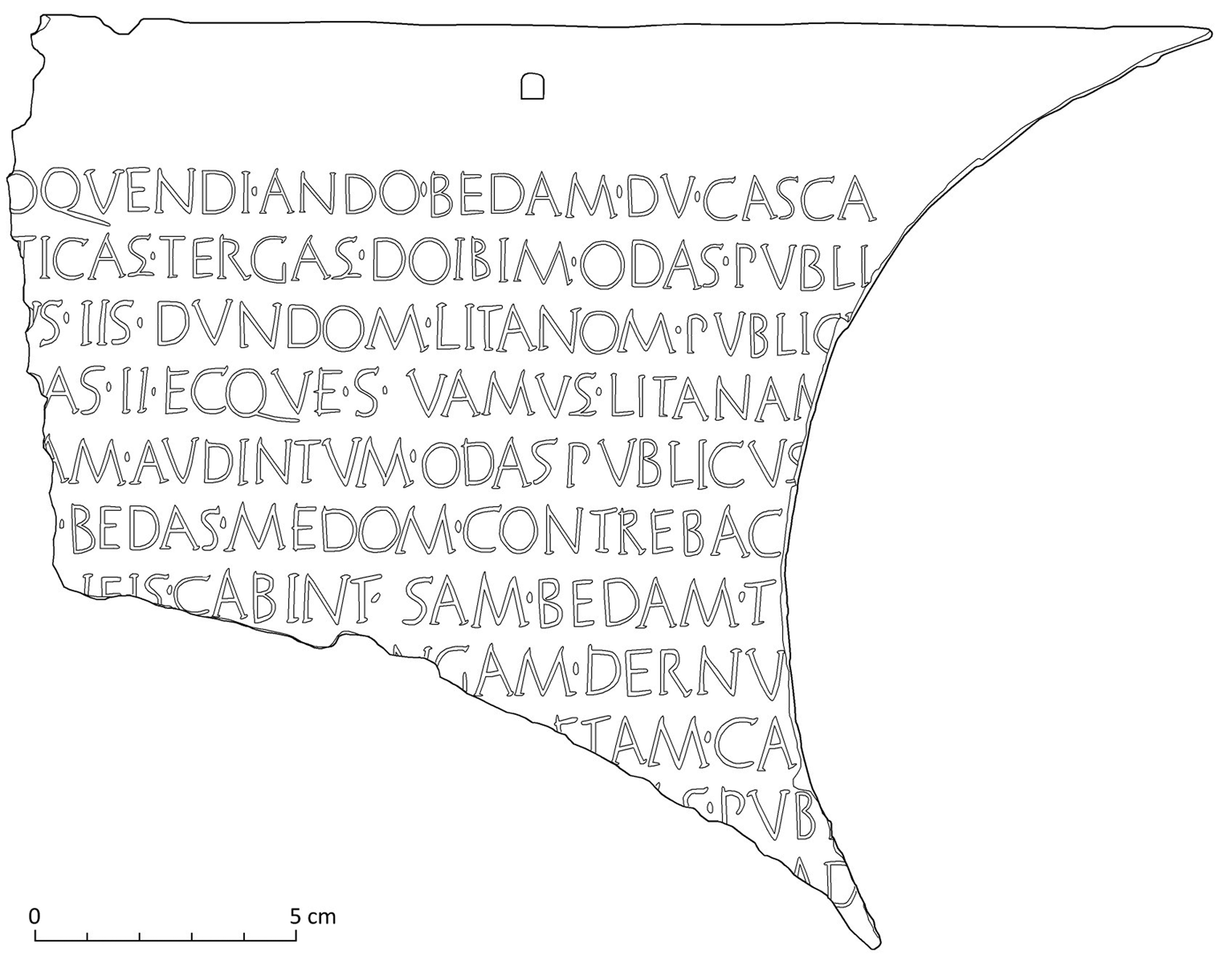

The piece has been kept at the Zaragoza Museum since 2012. It is a fragment of a bronze plaque of irregular shape (Figs. 3–4). It measures [18.1] cm in height by [22.5] cm in width and 0.2 cm in thickness (incomplete measurements are in brackets). The upper edge is original, whereas the other three have been cut. The right side was cleanly cut, and its edge has a carefully beveled finish. In contrast, the left and lower edges were carelessly cut and they have an irregular appearance.

Fig. 3. The Novallas Bronze. (Courtesy Museo de Zaragoza.)

Fig. 4. The Novallas Bronze. (Drawing by M. C. Sopena.)

Between the first line of the text and the upper edge, there is a margin of 1.5 cm. Approximately 1 cm from the upper edge and 9.5 cm from the left side, there is a deformity on the surface of the piece, similar to a rivet, but which nevertheless does not pierce the bronze sheet. Next to it is a square hole 0.5 cm wide, designed to allow the sheet to be fastened with a nail.

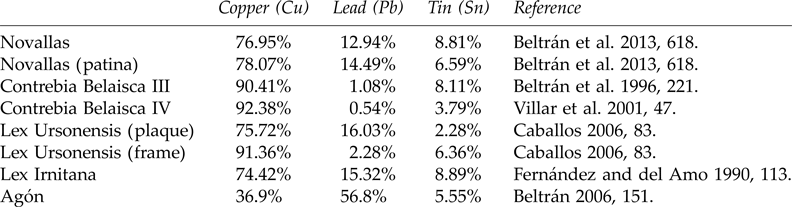

Surface analysis of the piece has identified the presence of salts, chlorides, and malachite on the plaque – a consequence of having been buried for a long time.Footnote 15 Traces of carbons have also been identified, as well as the formation of corrosion oxides, both cuprite and tenorite, the latter the result of exposure to a source of intense heat. Metallographic analysis confirms that the bronze has a ternary composition of copper, lead, and tin, with small percentages of iron, nickel, and antimony.Footnote 16 It shows a percentage of lead higher than the Celtiberian inscriptions in Palaeohispanic script from Contrebia BelaiscaFootnote 17 and closer to that of some Hispanian Latin inscriptions – such as the Lex Ursonensis, perhaps inscribed in the Augustan or Tiberian period,Footnote 18 and the Lex Irnitana, from the Flavian periodFootnote 19 – although still less than the Hadrianic-period Agón Bronze,Footnote 20 which stands out precisely because of its high lead content (Table 1).

Table 1. Results of the metallographic analyses of the Novallas Bronze, the Celtiberian bronzes from Contrebia Belaisca III and IV, the Agón Bronze, the Lex Ursonensis (plaque and frame), and the Lex Irnitana.

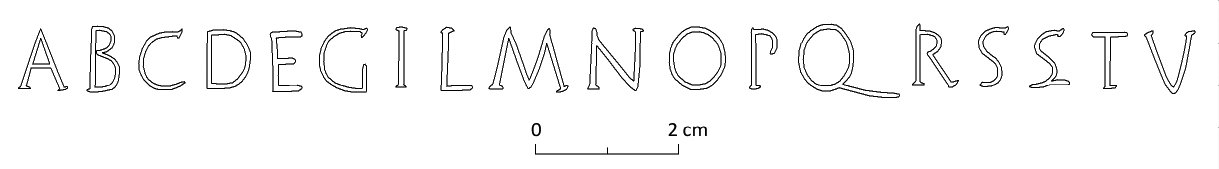

The preserved text is arranged across 11 lines and includes a total of 40 words, some incomplete. It is written in excellently produced Latin capitals made through incision, which measure between 0.7 and 0.9 cm high. The alphabet used has some Late Republican palaeographic features, among which the most obvious are the M with open angles and the circular O, as well as the open P and R (Fig. 5). Some letters, however, possess slightly more evolved features that belong to a period a little further on – in particular, the C, D, and Q. Notable is the appearance of a particular type of S with a horizontal stroke on its bottom edge, which we here transcribe as Ś. All these elements allow us to think that the inscription should be dated around the last years of the Republic or the beginnings of the Augustan period.

Fig. 5. The alphabet of the Novallas Bronze. (Drawing by M. C. Sopena.)

There appears to be word segmentation at the end of the lines. This seems certain in the sequence PVBLI- in the second line and probably also in the CASCA- of the first. Word segmentation between two lines is a relatively late habit that is not documented in Latin legal epigraphy in bronze before the Caesarean period.Footnote 21

The cut on the left side affects all the lines of the text, so it makes it difficult to determine the number of letters lost. In contrast, the cut on the right side only affects the text from the third line, whereas the ends of the first two appear complete. The fact that to the right on the upper part of the bronze a space is preserved of up to 7 cm – much greater than the 1.5 cm of the upper margin – suggests that the text had at least a second column, without dismissing the possibility that it could have had another to the left, judging by the position of the mounting hole, which is usually placed at the center of a plaque.

Text and commentary

[---]OQVENDI ⋅ ANDO ⋅ BEDAM ⋅ DV ⋅ CASCA

[---]TICAŚ ⋅ TERGAŚ ⋅ DOIBIM ⋅ ODAS ⋅ PVBLI

[---]VS ⋅ IIS ⋅ DVNDOM ⋅ LITANOM ⋅ PVBLIC̣+[-1-]

[---]+AS ⋅ II ⋅ ECQVE ⋅ S ⋅ VAMVŚ ⋅ LITANAṂ [-1-2?-]

5 [---]ẠM ⋅ AVDINTVM ⋅ ODAS PVBLICVS [-2-]

[---] ⋅ BEDAS ⋅ MEDOM ⋅ CONTREBAC[-2-3-]

[---]+ẸIS ⋅ CABINT ⋅ SAM ⋅ BEDAM ⋅ T[-3?-]

[---]++GAM ⋅ DERNV[-2-3-]

[---]ẸTAM ⋅ CA+[-2-3-]

10 [---]S ⋅ PVBḶ[-1-2-]

[---]ẠD[-1-2?-]

------

3. The crux (i.e., the remnant of a letter that is impossible to identify) corresponds to the start of a line that was probably oblique, which, given the context, could belong to a V.

4. The crux could correspond to a D and, with less confidence, to an O. Before VAMVŚ the spacing is slightly wider. The reconstruction of LITANAṂ is plausible from a morphological perspective.

7. The crux could correspond to an N or an I. The next letter could also be F, but this is excluded for phonetic reasons and for its rarity in Celtiberian. Before SAM, the spacing is slightly wider.

8. The first crux seems to correspond to an A or an M, in which case, the second crux should be read I: [---]AIGAM or [---]MIGAM. The possibility cannot be excluded that the two cruces correspond, less plausibly, to an N: [---]NGAM.

9. The crux presents an angular shape that can only belong to an E or F.

11. The initial strokes could also correspond to an M.

Our knowledge of the Celtiberian language remains very limited. This, together with the text's fragmentary state of preservation, makes it difficult, for the moment, to offer a completely satisfactory interpretation of the inscription. There are few terms whose meanings can be established with confidence.Footnote 22 It is likely that the sequence CASCA- corresponds to the ancient city of Cascantum, identified with the modern town of Cascante, situated in the vicinity of Novallas.Footnote 23 Less confidently, the term TERGAŚ could be interpreted as the ablative singular of a nominative *TERGA. This may be related to the Celtiberian city that minted bronze coins at the end of the 2nd c. BCE with the legend terkakom written in Palaeohispanic script,Footnote 24 which some authors identify with the modern municipality of Tierga, situated 50 km south of Novallas.Footnote 25 CONTREBAC[-2-3-] seems to be related to the form kontebakom, attested in Palaeohispanic script,Footnote 26 an adjective formed by the suffix -āko-, from a substantive contrebia, the etymology of which seems clear: kom- (“together”) + *treb- (“to live, habitation”) + *-yā collective suffix.Footnote 27 We know three Celtiberian cities called Contrebia: Contrebia Belaisca,Footnote 28 Contrebia Carbica,Footnote 29 and Contrebia Leucada.Footnote 30 The latter is located where the modern town of Inestrillas is, 30 km north of Novallas. There is nothing to confirm that the word on the bronze refers to any of these cities, however, because it could also simply be a common adjective.

Some sequences can be interpreted as Latin loans. [---]OQVENDI, which is hard to explain from a Celtiberian perspective, could correspond to a Latin gerund or gerundive, perhaps loquendi or one of its compounds.Footnote 31 PVBLICVS also seems to be a Latin loan, given the disappearance of the original *p in initial position in almost all ancient Celtic languages and, in particular, in Celtiberian.Footnote 32 On two of the three occasions on which this word is repeated, it is associated with the term ODAS, with which it appears to agree in gender and case, and in which the original *p has in this case disappeared.Footnote 33 It has been suggested that the sequence ODAS PVBLICVS could be an imitation of the Latin sequence pedes publicos,Footnote 34 although in fact this sequence is only documented from the medieval period.Footnote 35 The sequence II ECQVE S could also be borrowed from Latin, if II and S can be understood as a numeral and the abbreviation of semis. ECQVE bears all the appearance of a copulative coordinating conjunction,Footnote 36 so the complete sequence seems to be the equivalent of the Latin expression duo et semis. In this respect, the form IIS that appears in the line immediately above could be identical to the former one and equivalent to the Latin abbreviation of sestertius,Footnote 37 which is documented for the first time, without a horizontal stroke, in fractions of the denarius, which were minted at the end of the 3rd c. BCE.Footnote 38 Both cases could be references to the Roman unit of measurement, the pes sestertius, which had already been recorded in the Twelve Tables.Footnote 39

Other words also allow for reasonable, but not always conclusive, interpretations. For example, LITANOM and LITANAṂ could be interpreted as respectively masculine and feminine accusatives of an adjective with three endings with the meaning “wide”Footnote 40; VAMVŚ seems to be the ablative singular of an adjective in superlative degree, “the highest”Footnote 41; whereas DVNDOM recalls the Latin form dandum – gerund or gerundive of the verb dăre, “give” – although in this case, maybe it is better to consider it a Celtiberian form, derived from the proto Indo-European root *deh3- or *deh3u-, also attested in the Lusitanian word DOENTI.Footnote 42

It is impossible to reach a wholly satisfactory conclusion about the content of the Novallas Bronze, and even less to propose a translation, bearing in mind, moreover, its fragmentary state of preservation: its lines are incomplete at their start and, in the majority of cases, also their end. All that can be asserted confidently is that it is an official text, written in Celtiberian language, of a good size, and intended to be displayed in a public space. It is likely, given its characteristics, that it was issued by the local authorities in turiazu or kaiskata ‒ the two cities closest to where it was discovered ‒ in the final decades of the 1st c. BCE.

It is possible that duo et semis, in association with the adjectives LITANOM and LITANAṂ (“wide”), could be related to the Roman concept of ambitus and iter limitare – that is, the space of two and a half feet that every owner was supposed to leave between two buildings or two fields, as recorded in the Twelve TablesFootnote 43 and in the Lex Mamilia.Footnote 44 It is therefore reasonable to propose the hypothesis that the Novallas Bronze contained a legal text that regulated the space it was necessary to leave empty around a road, a canal, or public property – although for the moment, it is impossible to confirm these possibilities.

The Novallas Bronze in the context of Celtiberian epigraphy

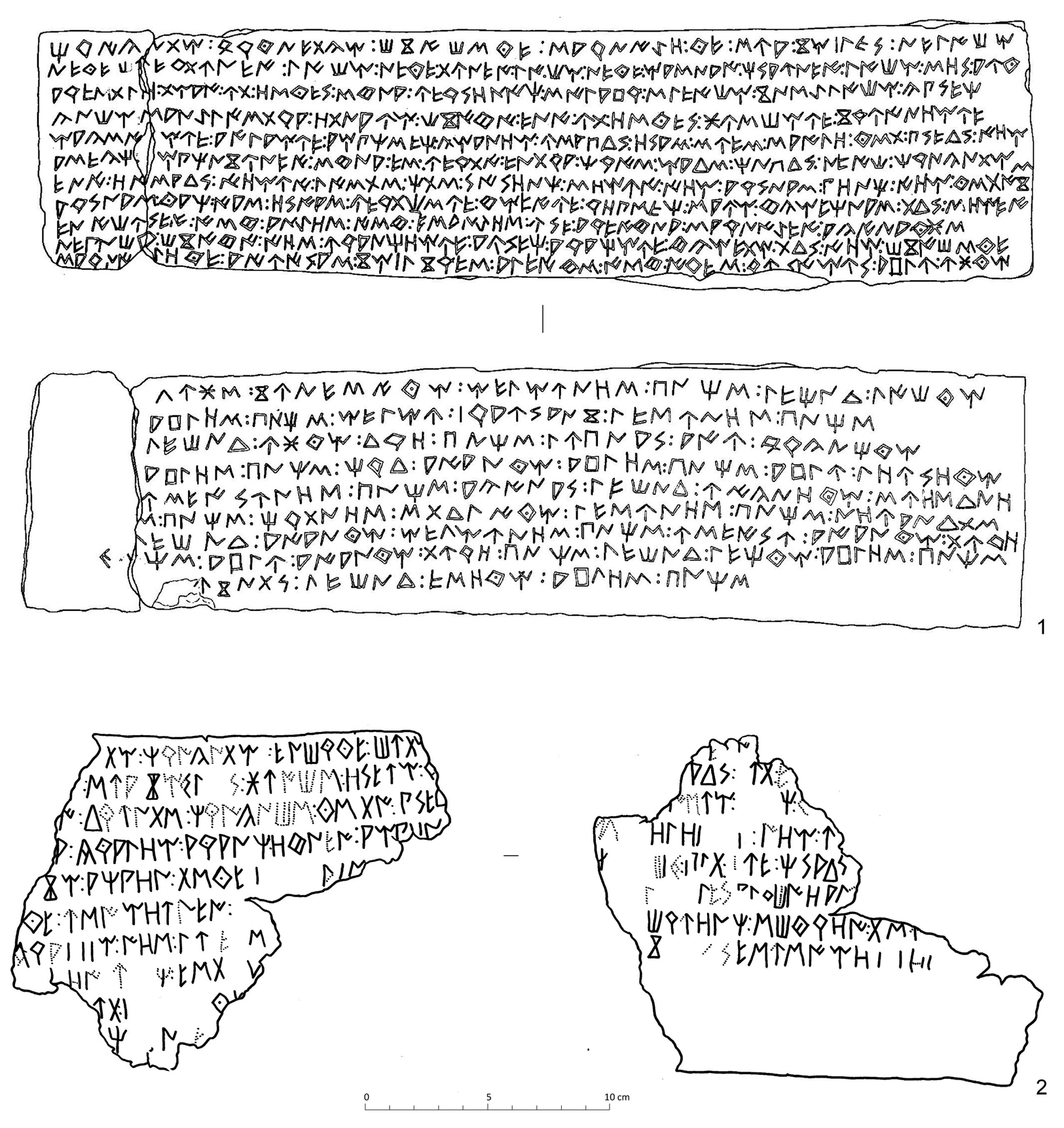

Inscriptions on bronze tablets can be considered one of the most characteristic elements of Celtiberian epigraphic culture. We currently know of four Celtiberian inscriptions on medium or large bronze tablets. Three of them were recovered in Contrebia Belaisca (Botorrita), from where the famous Tabula Contrebiensis also comes. The latter tablet, written in Latin, records the verdict of legal action fought between the Iberian city of Salduie (Zaragoza) and the Vasconic city of Alaun (Alagón) over the construction of a canal. The verdict was delivered by the Senate of Contrebia Belaisca itself and sanctioned by the governor of the province of Hispania Citerior, C. Valerius Flaccus, in 87 BCE.Footnote 45

Two of the bronzes from Contrebia are opisthographic, although it is not possible to determine whether the texts on the back and the front belong to the same document or – more probably – are examples of the support being reused (Figs. 6.1 and 6.2).Footnote 46 Nor is there unanimity about the interpretation of their content, although in both cases it seems clear that these are legal texts with highly formulaic content.Footnote 47 The third Contrebia bronze, also called the Great Bronze because of its large size (52 × 73 cm), records a long list of names arranged over four columns, preceded by a two-line heading.Footnote 48 It is by far the longest inscription within the Celtiberian epigraphic corpus. Once again, our limited understanding of the Celtiberian language impedes identification of its nature, although there is no doubt that this is an official document, the layout of which is clearly inspired by Roman models.Footnote 49

Fig. 6. Celtiberian inscriptions on bronze from Contrebia Belaisca. (1) MLH IV K.1.1 = BDH Z.09.01. (Drawings by B. del Rincón.) (2) BDH Z.09.24. (Drawings by C. Jordán.)

The collection is completed by the Luzaga Bronze (Guadalajara), which is slightly smaller than those recovered in Contrebia Belaisca (15 × 16 cm).Footnote 50 We are likewise unable to understand its content, although everything indicates that it, too, is an official text that, according to some researchers, could correspond to an agreement involving two cities:Footnote 51 arekorataFootnote 52 and *lutia, perhaps the same Luzaga where the piece was discovered.Footnote 53

To the four “great” Celtiberian bronzes we can add another four pieces produced on sheets of smaller dimensions.Footnote 54 None of them exhibits mounting holes, so it is not possible to determine whether they were intended for public display (as were those discussed above), or if these were portable documents whose functions were closer to those of tesserae hospitales, among which there are occasional examples bearing relatively extensive texts.Footnote 55

All these documents were written in Palaeohispanic script and can be dated approximately between the final decades of the 2nd c. BCE and the first decade of the 1st c. BCE. In fact, it is very likely that all of them predate the end of the Sertorian War, the point after which inscriptions in this type of script become increasingly rare.Footnote 56 In this context, the Novallas Bronze constitutes an unexpected novelty. It is at least half a century later than the other Celtiberian bronzes, and it is the only one written using the Latin alphabet.

The Novallas Bronze and Celtiberian epigraphy written in the Latin alphabet

Around the first half of the 1st c. BCE, the Celtiberians began to use the Latin alphabet to write their own language. At that point, they had already been using the Palaeohispanic script for over a century, having adopted it from the Iberians of the Mediterranean coast perhaps in the late 3rd c. BCE, if not before.

The Celtiberian-Latin epigraphic repertoire numbers barely 40 documents (Fig. 7).Footnote 57 Half of those texts belong to the group of inscriptions incised on a rock wall of the open-air sanctuary of Peñalba de Villastar (Teruel),Footnote 58 where several Latin inscriptions have also been documented,Footnote 59 among them a verse from Virgil's Aeneid, which allows us to date the group to the early decades of the 1st c. CE.Footnote 60 Peñalba has also provided the second-longest Celtiberian-Latin inscription after the Novallas Bronze, with seven lines of text and a total of 18 words.Footnote 61 The remaining corpus of Celtiberian-Latin inscriptions is very small; we have only 8 tesserae hospitales,Footnote 62 2 inscriptions on gravestones,Footnote 63 2 coin legends,Footnote 64 and several graffiti on pottery and other small objects.Footnote 65

Fig. 7. Findspots of Celtiberian inscriptions written in the Latin alphabet. (Drawing by M. C. Sopena.)

Until the discovery of the Novallas Bronze, the use of the Latin alphabet to write the Celtiberian language appeared to be occasional, characteristic of a transitional period in which Latin started to prevail as an official language and the use of autochthonous languages became progressively restricted to increasingly marginal spheres. This perception has now been radically modified. Not only does the Novallas Bronze confirm the survival of Celtiberian as a public and official language at the end of the 1st c. BCE, but it also provides evidence that the use of the Latin alphabet was not something sporadic – on the contrary, it can be considered the result of a careful and systematic endeavor to adapt it. This endeavor even had as a consequence the creation of a new letter, following a process also attested among the Umbrians and the Gauls.Footnote 66

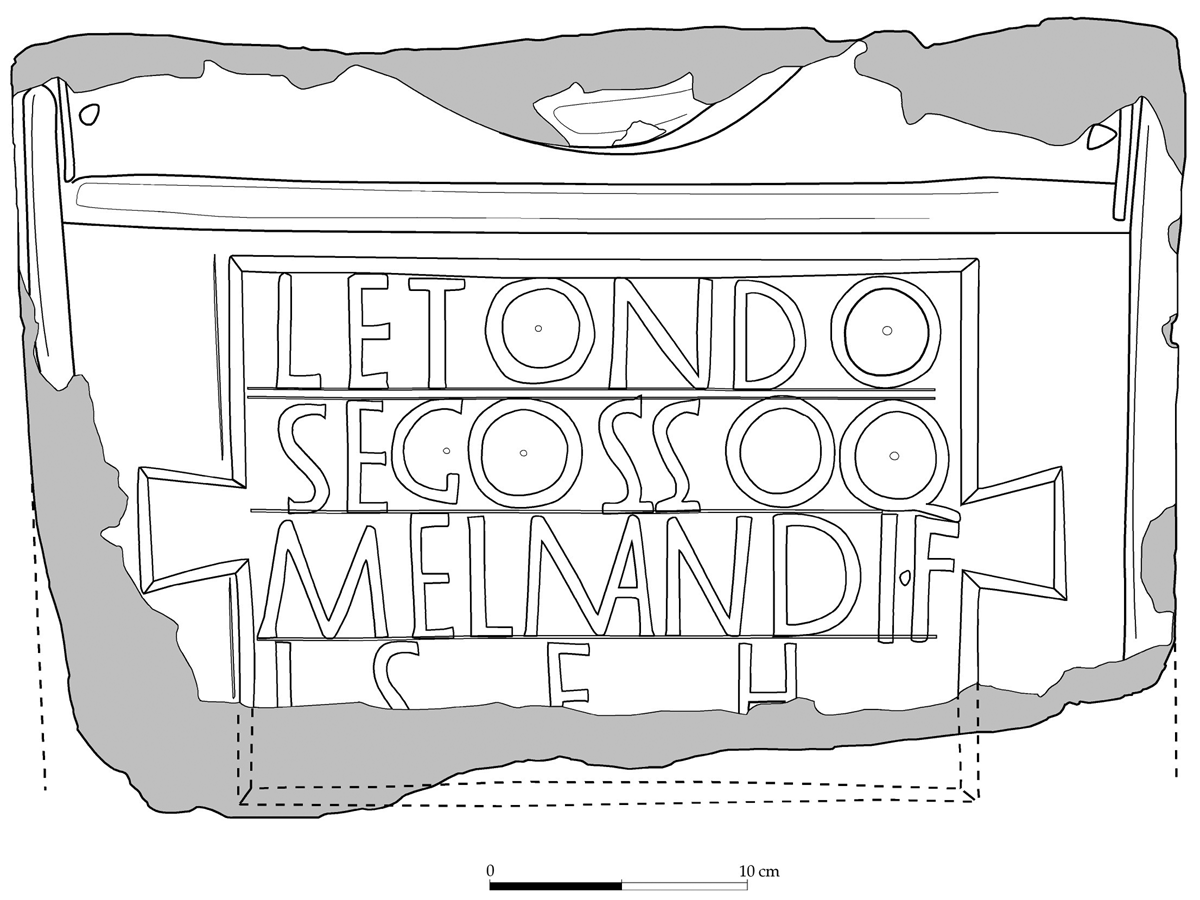

The letter Ś corresponds to a fricative or affricate sound that could embrace [θ], voiceless interdental fricative; [ð], voiced interdental fricative; [ʦ], voiceless dental-alveolar affricate; [ʣ], voiced dental-alveolar affricate; and even other sounds.Footnote 67 Following its identification on the Novallas Bronze, its presence has been confirmed in two of the Celtiberian-Latin inscriptions from Peñalba.Footnote 68 It is also documented in several Latin inscriptions from the Imperial period, in which it is used in the transcription of a gentilic adjective and various autochthonous proper nouns (Fig. 8).Footnote 69 The survival of this sign in Latin epigraphy from the interior of Spain until at least the early 2nd c. CE confirms that the adoption and adaptation of the Latin alphabet by the Celtiberians was a more significant phenomenon than we had suspected. In fact, it gives the impression that its use must have been more prevalent than the limited number of documents implies and suggests the existence of more widespread and systematic forms of teaching writing than has been believed.Footnote 70

Fig. 8. Fragment of a stele from Buenafuente del Sistal (Guadalajara), now at the National Archaeological Museum, Madrid. The second line of text bears a Celtiberian family name abbreviated in the genitive plural: Segośśoq(um). (CIL II 5790. Drawing by M. C. Sopena.)

The historical and territorial context

Although we do not know the exact spot where the Novallas Bronze was displayed, nor are we able to determine its contents with precision, the territorial context of its provenance offers some clues that enable us to evaluate it better as a historical document. The municipality of Novallas is situated in the central valley of the Queiles River, which rises among the slopes of the Moncayo Massif and discharges into the Ebro by the Navarran city of Tudela (Fig. 9). The Queiles formed part of the geographical space to which the Graeco-Latin authors refer with the term Celtiberia, the northern limit of which was in the Middle Ebro Valley.Footnote 71 According to Appian, in the early 2nd c. BCE, the Celtiberian populations that were settled alongside the Ebro were members of the Lusones.Footnote 72 Upriver of the Ebro, in the region of the current province of La Rioja, were the Berones, a Celtic people whom the ancient authors never included among the Celtiberians.Footnote 73 Downriver, around the mouths of the Jalón and Huerva Rivers, lived the Sedetani, who were not Celtic but Iberian.Footnote 74 The Vascones were settled on the left bank of the Ebro, but with some cities also located to the south of the river.Footnote 75

Fig. 9. The Queiles and Middle Ebro Valleys in the second half of the 1st c. BCE. (Drawing by M. C. Sopena.)

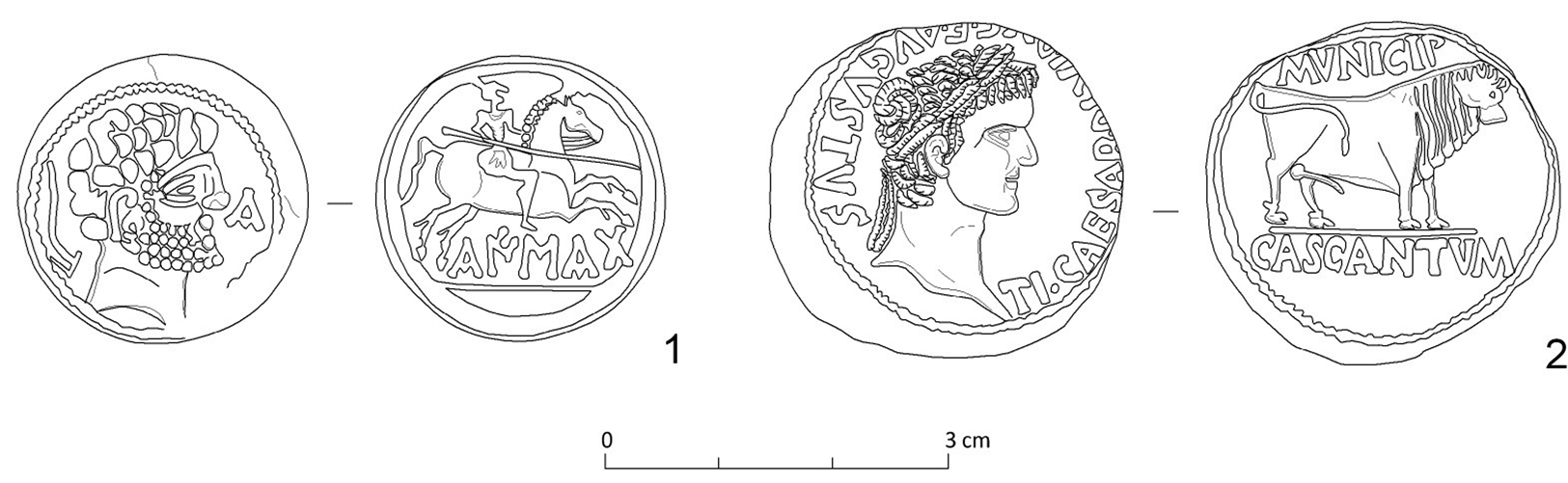

The Queiles Valley has provided very few ancient inscriptions.Footnote 76 The most representative Palaeohispanic documents are perhaps the coin legends from turiazu (Fig. 10.1–2)Footnote 77 and kaiskata (Fig. 11.1),Footnote 78 which from a numismatic perspective can be considered Celtiberian,Footnote 79 even if there are some doubts about the linguistic adscription of the toponym kaiskata-Cascantum.Footnote 80 The Celtic character of the language spoken in the territory was confirmed by the stone found in the 18th c. in the vicinity of Tarazona, composed in the Celtiberian language and written in Palaeohispanic script.Footnote 81

Fig. 10. Coins from turiazu/Turiaso. (1) Silver denarius. Obverse: bearded male head with torc, and letter ka. Reverse: mounted lancer, legend turiazu (MLH I A.51.1 = BDH Mon.51.1); (2) Bronze fraction. Obverse: female head wearing a galea, and letter ka. Reverse: galloping horseman, crescent moon, and star, legend turiazu (MLH I A.51.1 = BDH Mon.51.1); (3) Bronze as. Obverse: female head, legend Silbis. Reverse: horseman raising his arm, legend Turiaso (RPC I 401); (4) Bronze as. Obverse: head of Augustus, legend Imp(erator) Augustus p(ater) p(atriae). Reverse: corona civica, legend mun(icipium) Turiaso (RPC I 405). (Drawings by M. C. Sopena.)

Fig. 11. Coins from kaiskata/Cascantum. (1) Bronze unit. Obverse: bearded male head with plow behind it and letter ka. Reverse: mounted lancer, legend: kaiskata (MLH I A.49.1 = BDH Mon.49.1); (2) Bronze as. Obverse: head of Tiberius, legend Ti(berius) Caesar diui Aug(usti) f(ilius) Augustus. Reverse: bull, legend: municip(ium) Cascantum (RPC I 425). (Drawings by M. C. Sopena.)

Rome came into contact with the Queiles Valley a little after the end of the Second Punic War, with various military campaigns that culminated in the defeat of the Celtiberians by the troops of the praetor Ti. Sempronius Gracchus at the Battle of Mons Chaunus, perhaps the Moncayo mountain itself,Footnote 82 and the foundation in 179 BCE of the city of Gracchurris – modern Alfaro in La Rioja.Footnote 83 From this point, the Ebro Valley became the principal access route into the interior of the Peninsula, and the territory around the Moncayo Massif became a transition zone between the area controlled directly by Rome and the Upper Douro where Numantia was situated, which would be the object of periodic military campaigns until 133 BCE.Footnote 84

In this period, corresponding to the so-called Late Celtiberian (3rd to 1st c. BCE), there is evidence in the Queiles Valley of a significant increase in the number of settlements that, in the middle course of the river, organized themselves around the oppidum of Turiaso. This was probably situated below the old town of Tarazona, which at that time, acquired fully urban characteristics, as the intensity of its mint from the second half of the 2nd c. BCE indicates.Footnote 85 Something similar occurred downriver, around Cascantum, which in the second half of the 2nd c. BCE also had a mint, although with a much smaller volume of emissions.Footnote 86

The model of territorial occupation that followed the Roman conquest is related to the implementation of new production strategies oriented toward obtaining surpluses of grain, wine, and perhaps oil – destined to be distributed locally and regionallyFootnote 87 – and with the development of intense mining and metallurgic activity associated with the exploitation of seams particularly rich in iron ores that lay in the foothills of the Moncayo.Footnote 88

This landscape changed radically in the 70s BCE. The area provided one of the main theaters for the confrontation between Sertorius and the troops of the Senate, and many cities that took part on one side or the other suffered serious damage.Footnote 89 Among those most affected were Contrebia Leucada (Inestrillas), Calagurris (Calahorra), Gracchurris (Alfaro), Bursao (Borja), and Cascantum itself.Footnote 90

The consequences of the war against Sertorius explain the radical restructuring that occurred across the region in the final days of the 1st c. BCE, coinciding with the unfolding of the Cantabrian Wars. At this point, a profound redevelopment of the network of rural settlements began, some of which by then already corresponded to the typology of the villae rusticae that became characteristic of the region over the next two centuries. The settlement of Chicharroya III itself, where the Novallas Bronze was discovered, belongs to this series of new farms.Footnote 91

The transformation of the rural landscape was probably associated with the construction of waterworks intended to further the development of intensive agriculture supported by irrigation. The famous Lex rivi Hiberiensis, recovered in the municipality of Agón in the neighboring Huecha Valley, regulated the operation of an irrigation canal as it passed through the pagus Gallorum (Gallur), which belonged to the colony of Caesar Augusta (Zaragoza), and the pagus Belsinonensis (Mallén), which formed part of the municipium of Cascantum.Footnote 92 The law is from the Hadrianic era, but it is possible that it reflects a reality that, at least partially, could date back to the early Imperial era, the point at which ‒ in the wake of the foundation of Caesar Augusta ‒ expensive water infrastructure projects were commissioned, intended to extend the ground that was to be irrigated in various places on the right bank of the Middle Ebro Valley.Footnote 93 It is in this context of profound changes in the organization of the territory that Turiaso and Cascantum were each granted their status as municipium.

Turiaso attained the status of municipium under Roman law in the Augustan era, as Pliny relates and its coins confirm.Footnote 94 In the 20s BCE, an exceptional emission of bronze asses was issued, perhaps intended to celebrate its legal promotion. This emission bears on its obverse a female head accompanied by the legend Silbis, which has unanimously been identified as a local aquatic deity, whereas on the reverse is depicted an equestrian statue, probably Augustus, accompanied by the legend Turiaso (Fig. 10.3).Footnote 95 After a hiatus of almost two decades, the mint resumed its activities around 2 BCE and, until the end of Tiberius's reign, regularly issued bronze asses and fractions that incorporated the types and legends characteristic of the Hispano-Roman coins of this period (Fig. 10.4).Footnote 96

It has been proposed that Turiaso's early elevation to municipium could have been related to a hypothetical stay by Augustus in the city, during which he perhaps recovered from the illness that affected him in 26 BCE, during the initial campaign of the Cantabrian Wars.Footnote 97 There is no way of confirming this attractive hypothesis,Footnote 98 despite that fact that in Tarazona, remains have been discovered of what could be a sanctuary related to a water cult – perhaps under the protection of the same goddess Silbis, who is reproduced on the coins – in which an exceptional carnelian bust of Augustus was recovered, which is perhaps a sign of the city's special connection with the princeps.Footnote 99

Cascantum was a smaller city than Turiaso. Pliny mentions it among the communities governed by Latin law, but it is difficult to determine the date of its promotion.Footnote 100 Its status as a municipium is confirmed by the few coins that it emitted in the Tiberian era, which incorporate the usual iconographic elements in municipal Hispano-Roman emissions, accompanied by the legend municip(ium) Cascantum (Fig. 11.2).Footnote 101 It is possible that the change in its legal status occurred a little after Turiaso's, perhaps after the end of the Cantabrian Wars. As we have seen, this is the point at which, following the foundation of the colony Caesar Augusta around 15 BCE, the right-hand bank of the Middle Ebro Valley started to undergo a process of profound reorganization. This probably included the promotion to municipium of other cities in the area, such as Gracchurris (Alfaro, La Rioja) and Osicerda (La Puebla de Híjar?, Teruel).Footnote 102

It is likely that, given its characteristics, the Novallas Bronze could have been displayed in one of these two cities. All indications suggest that its text contains a legal document in which, it seems, various cities were implicated, among them perhaps Cascantum itself. The text's chronology allows us to place it within a complex historical moment in which the Roman authorities implemented a profound territorial reorganization that culminated in the conversion of the ancient Celtiberian urban nuclei into municipia. We barely know the main strands of this complex process, which probably took a long time. It is tempting to think that the Novallas Bronze could have been directly related to these shifting circumstances in which, as some cities became municipia, they had to redefine their relationship with their neighbors who had not, and who continued to use Celtiberian as their official language.

Final thoughts

Our knowledge of the Celtiberian language remains very limited, despite the notable advances achieved by the research undertaken in recent decades ‒ research stimulated by the discovery of a cluster of singularly important inscriptions that have significantly augmented the slender repertoire of texts preserved in that language.

What we do know is that the Novallas Bronze belongs to a time of rapid and profound political and economic changes in inner Spain. This period witnessed both the final breakup of those characteristic features of autochthonous societies that had survived the initial phase of Roman conquest and the development of the new model of Romano-provincial society that would characterize the Julio-Claudian period. In this context, this new inscription allows us to sense a much more complex reality than we had until now been able to suppose, in which the old local language, Celtiberian, demonstrated an unexpected vigor at the very moment when the process of Latinization already appeared irreversible.

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken within the framework of the recently created Institute for Research into Heritage and Humanities (IPH) at the University of Zaragoza and the Hiberus Group of the Aragón autonomous government. More specifically, it was developed through the research projects “El final de las escrituras paleohispánicas” and “Escritura cotidiana. Alfabetización, contacto cultural y transformación social en Hispania citerior entre la conquista romana y el final de la Antigüedad,” both funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, and in which M. J. Estarán, J. Herrera, G. de Tord, and A. González have participated, as well as the authors. We would like to register our thanks to H. Arcusa for the information about the excavations in recent years at the site of Chicharroya III; to J. J. Bienes and J. A. Hernández, who played key roles in the recovery of the Novallas Bronze; and to I. Aguilera, director of the Zaragoza Museum, for the resources provided for studying the piece.