Introduction

Although political scientists tend to focus on responsiveness under formal accountability mechanisms, such as elections, many important political organizations do not fit this mold. For instance, interest groups and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are not subject to external or internal accountability mechanisms uniformly across countries (Wapner, Reference Wapner2002). The internal accountability mechanisms that do exist, through boards of directors for instance, are not always transparent or impartial enough to operate as a sufficient source of accountability (Ebrahim, Reference Ebrahim2003). This is especially true among a set of political, non-governmental organizations: hierarchical religious groups (Haynes, Reference Haynes2001). In the absence of elections or other formal accountability mechanisms, do centralized religious leaders have incentives to be responsive to members' political concerns over time, and why?

Effective interest groups, including religious organizations, secure members and their resources to expand networks and coordinate political activities (Iannaccone, Reference Iannaccone1992; Finke and Stark, Reference Finke and Stark1998). For their part, members of centralized religious organizations also want their leaders to be responsive to their preferences (Calfano, Reference Calfano2009; Trejo, Reference Trejo2009). If followers receive responsiveness, they should be more likely to trust and support the organization. Yet, if members do not receive responsiveness, they can always “vote with their feet” and sanction the religious organization by exiting or reducing support (Chesnut, Reference Chesnut2003). Religious groups are often limited, however, in the actions that they can take to be responsive. So, an effective strategy is to provide symbolic responsiveness through the distribution of public messages that relate to the preferences of their members (Calfano et al., Reference Calfano, Oldmixon and Gray2014; Smith, Reference Smith2019). By speaking out on issues that members believe are important, centralized religious leaders may be able to maintain or increase organizational trust and participation.

To analyze whether centralized leaders of religious organizations supply responsiveness through their public messages and whether that supply is driven by the expectation that members provide legitimacy and resources in return, I examine one of the largest and oldest religious organizations that has few formal internal or external accountability mechanisms: the Roman Catholic Church. I argue that centralized religious leaders that weaken their support among members risk their organizations', and their own, political strength. The central leader of the Church, the Pope, should therefore have strong incentives to tailor his messages to represent his members' concerns.

First, I evaluate the impact of global Catholic public opinion on papal rhetoric to show that the Pope is responsive to Catholics' preferences over time using a unique data set of papal speeches, messages, and letters. The findings suggest that when an issue gains saliency among a greater proportion of members worldwide, the Pope dedicates a greater proportion of his rhetoric to that issue. The converse, however, is not empirically verified; papal rhetoric is not a reliable predictor of Catholic public opinion, which implies that papal rhetoric may not systematically influence Catholics' aggregate priorities over time.

Second, I explore the underlying incentive for the Pope to be responsive though there are few, if any, formal accountability mechanisms to sanction his non-responsiveness. Given the reliance of the Church on its members, I hypothesize that the main motivation of the Pope to be responsive is driven by an expectation that members are more likely to increase their organizational trust and participation when they receive messages that reaffirm their political concerns. As such, members who already agree with the Church on political issues and have a greater existing willingness to participate, by definition, receive and expect responsiveness given their frequent interaction in church activities. I anticipate that these dedicated members should be more likely to react positively to papal responsiveness by exhibiting a greater willingness to participate in the organization.

I conduct original nationally representative survey experiments of Catholics in Brazil and Mexico to test this argument. The results suggest that dedicated members are more likely to expect responsiveness, and when it is provided, they are more likely to increase their participation and their perception of how much responsiveness the Church provides. Less active members, on the other hand, are less likely to exhibit high levels of trust and participation in the Church, regardless of which papal statements they receive. In fact, less dedicated members who receive responsive messages are less interested in attending services and volunteering in the future than less dedicated members who do not receive responsive messages. To the extent possible, I examine how this heterogeneous treatment effect between frequent and infrequent attendees is driven by disagreement between respondents' and the Church's political advocacy or preferences.

The two complimentary analyses support a comprehensive argument that builds on previous work detailing how the demand of followers shapes the Church's supply of political activity in the religious marketplace (Iannaccone, Reference Iannaccone1991; Gill, Reference Gill1998; Djupe and Neiheisel, Reference Djupe and Neiheisel2019). Importantly, however, I contribute an alternative perspective that outlines when and how centralized religious leaders, like the Pope, act in accordance with their own followers' political preferences to maintain and extract support, rather than concentrate on the ability of religious leaders to influence members' political preferences.

Responsiveness in centralized religious groups

A central assumption of representational democratic theory is that elections are the primary mechanism through which members or constituents can hold organizational leadership accountable, which motivates leaders to be responsive.Footnote 1 Yet, even when there are theoretically strong motivations for group leaders to be responsive, models of elite behavior still typically focus on the ability of leaders to influence members by disseminating information, framing debates in the media to influence members' preferences, and acting as group representatives (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992; Clifford and Jerit, Reference Clifford and Jerit2013). Unelected central leaders should exert even greater control over other internal actors and lower leaders because those centralized leaders generally benefit from higher degrees of access (Hafner-Burton and Montgomery, Reference Hafner-Burton and Montgomery2010).

This is precisely how centralized religious organizations, such as the Catholic Church, are believed to operate.Footnote 2 The Catholic Church functions as any other interest group; it fulfills its organizational objectives on as broad a scale as possible to influence internal actors such as parishioners, priests, and cardinals, as well as external actors such as national governments (Huntington, Reference Huntington1973). The Church carries out its organizational objectives using a large bureaucracy (the Roman Curia) which is charged with the administration of the Catholic Church (Valuer, Reference Valuer1971).

As messengers of the centralized church, rank-and-file Catholic clergy are thought to be highly constrained in their ability to express any political preferences that oppose the Church's preferences, though they do have some options to preserve their voice (Trejo, Reference Trejo2009; Holman and Shockley, Reference Holman and Shockley2017; Hale, Reference Hale2018). For instance, clergy across Christian denominations in the United States talk about the issues that are important to them and the central organization, but then talk about the issue in ways that cater to their congregation (Boussalis et al., Reference Boussalis, Coan and Holman2021). Clergy may take on delegate roles and act against their preferences (Calfano, Reference Calfano2009), but generally, clergy express preferences close to the central institution (Calfano and Oldmixon, Reference Calfano and Oldmixon2018).

As evidence of their effort, local religious leaders have been shown to influence followers' preferences and behavior (Djupe and Calfano, Reference Djupe and Calfano2013; Paterson, Reference Paterson2018; Smith, Reference Smith2019), as well as their willingness to contribute to public goods and participate politically (McClendon and Riedl, Reference McClendon and Riedl2016; Rink, Reference Rink2018; Spenkuch and Tillmann, Reference Spenkuch and Tillmann2018; Condra et al., Reference Condra, Isaqzadeh and Linardi2019; McClendon and Riedl, Reference McClendon and Riedl2020).Footnote 3 Therefore, in the context of the Catholic Church, the standard model of accountability and responsiveness hypothesizes that papal rhetoric positively predicts Catholic public opinion. This is because the Pope is viewed as a leader of opinion, of both clergy and followers, and he has few formal incentives to be responsive to Catholics' current political concerns, which wax and wane.Footnote 4

Even elections, however, are limited in their ability to select or sanction agents simultaneously and followers can only induce accountability if representatives receive utility for their responsiveness (Fox and Shotts, Reference Fox and Shotts2009). Accordingly, though centralized religious leaders may not be fearful of electoral punishment, they still have strong incentives to act upon their supporters' preferences to maintain power and legitimacy (Stedman, Reference Stedman1964). Given the dispersed structure of the Catholic Church and other religious groups, such leaders still rely on their members for resources such as organizational trust, participation, and financial support which incentivizes unelected leaders to be responsive and compete for members (Finke and Stark, Reference Finke and Stark1992; Hofrenning, Reference Hofrenning1995a).

Trust in an organization is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for members to participate in and support a political organization. Leaders in democratic or undemocratic institutions must sustain organizational trust among their supporters because trust allows the organization to make decisions without the use of coercion or continual need for approval (Gamson, Reference Gamson1968). More precisely, organizational trust is considered an integral component of specific and diffuse support, such that high trust can increase specific/short-term support (Easton, Reference Easton1965). Continual high specific support from increased levels of trust then leads to high diffuse support. This process of diffuse support refers to the willingness of individuals to grant legitimacy to the organization (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington1998). Therefore, low levels of trust can potentially constrain the capacity of leaders to act in the short-term, as well as the long-term through a reduction of organizational legitimacy. In this sense, the support of members both directly and indirectly impacts organizational accountability through “mechanisms leading to punishment through hierarchy, supervision, fiscal measures, legal action, the market, and peer responses” (Grant and Keohane, Reference Grant and Keohane2005). This is especially problematic for religious organizations that face members' willingness to exit the organization based on congregational political agreement (Djupe et al., Reference Djupe, Neiheisel and Sokhey2018).

Since organizational trust is largely an evaluation of performance, it depends on the perceived responsiveness of the leader to satisfy the expectations of its supporters (Miller, Reference Miller1974). Leaders must be continually concerned with how their behavior impacts organizational trust, given the preferences of their supporters, because high responsiveness precipitates high levels of organizational trust in a cyclical nature (Keele, Reference Keele2007). Responsiveness, however, does not necessarily entail that leaders' public messages exactly match their members' preferences. Rather, in the context of religious groups, followers want their “group to work for political goals which they feel are consistent with their religious faith” (Hofrenning, Reference Hofrenning1995b, 37). In other words, to maintain organizational and positional power, centralized religious leaders should provide symbolic responsiveness through their “acts, speeches, and gestures” (Edelman, Reference Edelman1964, 188).

Even though the Pope has daily briefings from cardinals, bishops, and staff to achieve this goal and optimize his information flow about the international workings of the Church (Winfield, Reference Winfield2018), he cannot perfectly understand and express the concerns of every Catholic. How does the Church, therefore, remain responsive to a population that includes the Catholic Charismatic Renewal and Liberation Theology? While the Vatican has limited control over what local priests say or do (Warner, Reference Warner2000; Holman and Shockley, Reference Holman and Shockley2017), the Pope articulates the overall strategic direction of the Church. He attempts to discuss broad issues that rise the latter of the Roman Coria and largely uses non-informative communication, which can be impactful through salience and framing (Mullainathan et al., Reference Mullainathan, Schwartzstein and Shleifer2008). The Pope has already been shown, for example, to allocate a larger portion of his speech to “political” issues during times of international crisis (Genovese, Reference Genovese2015, Reference Genovese2019), as well as alter Church policy in response to public dissatisfaction (Gill, Reference Gill1998).

Importantly, I argue that the motivation of the Pope, and other unelected centralized leaders, to provide symbolic responsiveness is driven by the expectation that members increase their participation because diffuse support leads to higher organizational commitment and lower motivation to leave or exit the organization (Tan and Tan, Reference Tan and Tan2000).Footnote 5 Members' continued organizational commitment, consequently, is a function of their past and current organizational commitment. Supporters that receive responsiveness and develop organizational trust should be more likely to build, and then maintain, that trust. Therefore, I anticipate that Catholics who receive responsive papal messages are more likely to increase their organizational participation.

This particularly applies to individuals who are “core members” who frequently participate in the organization because they are the most likely members to receive responsiveness and accumulate goodwill toward the organization given their high existing levels of support. By definition, members who participate more frequently should be more likely to expect responsiveness because if the Pope is consistently responsive, core members are likely accustomed to it. Thus, when core members receive responsiveness, I hypothesize that they should be the most likely to increase their support given their high existing support.

In sum, although followers of centralized religious groups have few formal mechanisms through which to hold leaders accountable, the reciprocal relationship between an organization and its followers to maintain institutional support should incentivize unelected centralized leaders to be responsive to supporters' preferences. The motivation of centralized leaders to be responsive is largely driven by their reliance on members for their support and material resources, and the reaction that followers have to responsiveness. Members who are more involved in the organization should be more likely to have received responsiveness in the past due to their participation, expect responsiveness in the future, and react positively to responsiveness.

Research design

I test my theory using evidence from observational data and survey experiments. In study 1, I examine whether the Pope is responsive to Catholic public opinion. I develop a yearly measure of papal rhetoric to quantify his responsiveness to Catholics' global political concerns. I utilize a collection of over 10,000 original papal documents that I electronically gathered from the Vatican's digital archives. I perform an automated content analysis of the papal statements with accompanying regressions that model the relationship between the proportion of public rhetoric that the Pope dedicates to a given topic and the proportion of Catholics who are concerned about the same political issue.

In study 2, I field nationally representative online survey experiments of Catholics in Mexico and Brazil. The survey experiments assess how members react when the Pope provides political responsiveness, including how members' existing support and political agreement with the Church conditions the impact of responsive messaging. The two countries are home to the two largest populations of Catholics in the world, and they represent a sizable portion of Catholics worldwide, particularly among developing nations.Footnote 6 More importantly, given the strength of their collective voice, if Catholics in these two countries react positively to responsiveness, it lends support to the hypothesis that Catholics more generally exhibit similar behavior and that there is a motivation for the Pope to provide responsiveness to maintain support.Footnote 7 This multi-method approach rigorously assesses the empirical implications surrounding the supply and consumption of political responsiveness from centralized religious leaders.

Study 1: is the Pope politically responsive?

To evaluate whether the Pope is responsive to Catholics' political concerns, I analyze the relationship between papal rhetoric and Catholic public opinion from 1995 to 2014. The corpus of papal rhetoric is composed of 10,445 official public statements made by the Pope, including general audiences, speeches, masses, letters to public officials and dignitaries, homilies, angeluses, and apostolic letters.Footnote 8 These statements are communicated to Catholics worldwide, often directly from the Pope himself or through news media.

For example, Pope Francis released a post-synodal apostolic exhortation (Amoris laetitia or Joy of Love) addressing family care in 2016 (Holy See Press Office, 2016). A post-synodal apostolic exhortation is a papal response to the Synod of Bishops (an advisory body for the Pope) that shapes interpretation and encourages behavior but does not define Church doctrine. This seemingly obscure communication received international news coverage and analysis (Al-Jazeera, 2016; Goodstein and Yardley, Reference Goodstein and Yardley2016; Sherwood, Reference Sherwood2016), which is indicative of the media coverage for even relatively minor papal messages. As such, I use headlines from news articles about the Pope's statements in study 2 to replicate how many Catholics are informed about what the Pope says. Further, the vast scope of the corpus ensures that the measure of overall papal rhetoric captures more than just a small subset of statements that are intended for a specific audience. In total, the volume of documents helps accurately represent the totality of papal rhetoric created for public consumption during the observed period.

The documents are classified using the supervised learning algorithm ReadMe (Hopkins and King, Reference Hopkins and King2010), which relies on a hand-coded “training” set of papal documents from each category and year. The training set was hand-coded by randomly and uniformly sampling documents from each year in the observed period. Approximately 5% of the total corpus (as well as nearly 5% from each yearly corpus) is included in the training set, which matches the suggested number of hand-coded documents (Hopkins and King, Reference Hopkins and King2010). The Supplementary Materials provide details on the estimated topics of papal rhetoric, including examples of hand-coded documents, the retrieval process, and the automated content analysis.

The training set is used to estimate the proportions of papal rhetoric dedicated to each topic by year. I classify papal documents into five exhaustive categories, which is a requirement of the supervised algorithm: religious matters/other, socio-political issues, violence/conflict, human rights, and the economy. These categories were chosen to exactly match the topic categories of Catholic public opinion data to directly test whether papal responsiveness varies across issue areas.

To measure which topics Catholics are most concerned with, I compile information about the relevance of political topics to Catholics in a series of World Values Survey instruments between 1995 and 2014. The combined data set on Catholic public opinion includes data from the World Values Survey (2014), Americas Barometer (2014), Latino Barometro (2014), Afro Barometer (2014), Asian Barometer (2014), and the Euro Barometer (2014) data sets. The Supplementary Materials provide information about the number of Catholics included in the combined data set by country-year and survey-year, as well as the yearly percent of worldwide Catholics represented in the measure of public opinion.Footnote 9

First, I merge all regional surveys that ask respondents which political issue is most salient or important to create a measure of Catholic public opinion by topic and year. Second, I identify organization members (i.e., Catholics) by their self-identified religious denomination. I then select a survey item from each survey-round that asks respondents which issue is most important to measure the aggregate concerns of Catholics. In the combined data set from 1995 to 2014, the total number of Catholic respondents surpasses 400,000 from 86 different countries.

For each country, in each year, I take the proportion of Catholics who believe a given topic is the most important, weighted by their relative “voice” in the Church as a proportion of Catholics worldwide. Consider Brazil, which had about 65% (123 million) of its population self-identify as Catholic in 2010. If 50% of Brazilian Catholics, for example, believed that the economy was the most important political issue, then the amount contributed to public opinion is equal to (percent of Catholics in Brazil concerned with the economy) × (Brazil's Catholic population/worldwide Catholic population;) or (0.5) × (123 million/1.1 billion) = 0.055.Footnote 10 The global measure of public opinion on a given issue is the summation of the weighted “voice” from each country in the combined data set. I standardize these summed topic proportions of public opinion by the amount of Catholics surveyed in a given year, such that the percentages from all topic categories sum to one for each year. The measure of Catholic public opinion can thus be interpreted as the relative number of Catholics surveyed in a given year that believe topic x is the most important issue.

There are two limitations of the public opinion data. First, there is some variation in question-wording and answer options across surveys. For instance, in the World Values Survey respondents in 2014 were asked: “If you had to choose, which one of the things on this card would you say is most important?”. Respondents could only select from four vague and broad categories, which related to: violence/conflict, socio-political issues, economy, and human rights. Conversely, the Latinobarometro in 2005 asked respondents a slightly different question: “In your opinion, which would you consider to be the country's most important problem?”. The choice set for respondents was also different. Therefore, I classify issues such as terrorism and crime as violence/conflict, education and environment as socio-political issues, poverty and unemployment as economy, and freedom of religion or speech as human rights. In the analysis, I match these four categories of public opinion to their corresponding categories of papal rhetoric, excluding the outcome category for religious matters because there is no analogous category in the public opinion data.

Second, the number of respondents surveyed as a proportion of the total Catholic population varies by year because the cross-national coverage of the surveys on which I base this measure changes every year. In nearly every year the Catholics surveyed represent at least 30% of the total Catholic population worldwide. Though I cannot compile a completely representative survey of Catholics over time, I argue this subset represents the best indicator of worldwide Catholic public opinion available, and it provides a strong signal as to which political issues Catholics are concerned with generally that the Church, and the Pope, should be aware of.

Model estimation

The outcome of interest is the estimated proportion of papal speech dedicated to a given topic in a given year, which is composed of four categories (violence/conflict, economy, human rights, and socio-political issues). Each topic category j lies within the interval zero to one, and all categories sum to one for each year t (after including the estimated proportion of papal rhetoric dedicated to religious matters). As such, the unit of observation (y i) is a single topic proportion (j) in a single year (t) of papal rhetoric. Since there is one observation for each topic in one year, there are four observations for a given year. Catholic public opinion is represented as x i, which is the proportion of Catholics that believe issue j is the most important in year t.

Additionally, I include control variables to account for economic and political events that may be related to papal rhetoric and Catholic public opinion. It is difficult to find and measure global events that influence both papal rhetoric and Catholics' concern on the same issue. To maintain a parsimonious model, I add two causally prior indicators: (1) the logged number of battle-related deaths in the world (from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, Pettersson and Eck, Reference Pettersson and Eck2018) and (2) global economic growth (from the World Bank, 2014) for each year of the analysis. This is not an exhaustive set of potential predictors of papal rhetoric, but the inclusion of these variables in the model helps alleviate concerns that the direct association between Catholic public opinion and the propensity of the Pope to discuss political issues is due to the occurrence of international economic or military crises.

I perform a multi-level regression model using ordinary least squares (OLS) for several reasons. First, the secondary predictors that are causally prior to Catholic public opinion and papal rhetoric must be measured at the year-level, and they are invariant for all observations during the same year. In other words, the control variables are equal across all topic groups within a given year.

Second, to account for the possibility that the Pope is heterogeneously responsive to public opinion across issue areas, I vary intercepts (α) and slopes (β), also known as “random effects,” for each public opinion topic category j. This, theoretically, accounts for the fact that the Pope may try to connect with different interests and audiences in different contexts. In multi-level models, “random effect intercepts” for each topic are calculated as that topic's intercept deviation from the global intercept (Bosker and Snijders, Reference Bosker and Snijders2011, 349). To ensure that each topic has its own starting point, or intercept, and is not calculated in relation to the overall effect of Catholic public opinion on papal rhetoric, I remove the global intercept and estimate separate intercepts for each topic (Gelman and Hill, Reference Gelman and Hill2006, 349). Moreover, since all topics sum to one for each yearly observation, estimating a single model with all j topics would induce perfect collinearity because the predictors are exact linear combinations of each other (Gelman and Hill, Reference Gelman and Hill2006, 255). This specification examines the average, “fixed” effect of Catholic public opinion on papal rhetoric.Footnote 11

The second set of models investigates the reverse causal process: is Catholic public opinion responsive to papal rhetoric? I estimate, therefore, the same multi-level regression model using OLS, but papal rhetoric is used as a predictor (x i) of Catholic public opinion (y i). These models also allow for varying intercepts and slopes by topic as in the first set of models. For both sets of model specifications, I also estimate regressions that include lagged terms of the primary covariate (t–4, …, t–1) to capture any possible delayed covariation in the relationship.

Study 1 results: the Pope responds to members' concerns

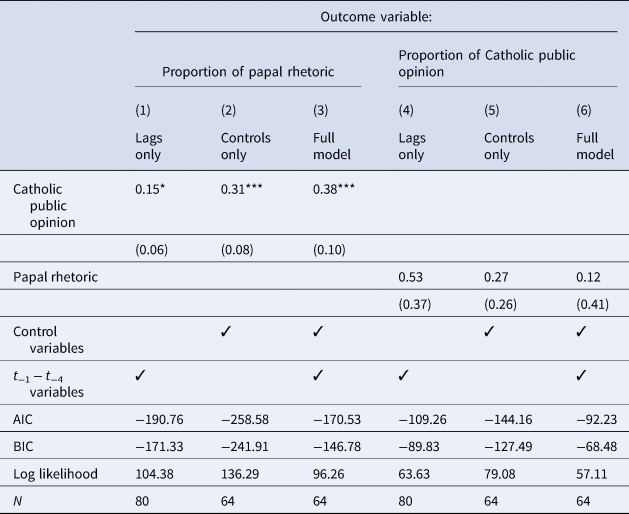

Table 1 provides initial evidence that the Pope is responsive to Catholics' political concerns as measured by aggregate public opinion. The estimated pooled coefficient of current Catholic public opinion is positive and statistically different from zero in each model (columns 1–3), indicating that when a greater portion of Catholics are concerned about a given issue, papal rhetoric dedicated to the same topic also increases. For instance, consider column 1 from Table 1 which uses only the contemporaneous value of Catholic public opinion and its lags (t–4, …, t–1) to predict papal rhetoric. The estimated coefficient indicates that a change in 1% in Catholic public opinion on issue x j is associated with a simultaneous change of 0.15 in the proportion of papal rhetoric dedicated to issue x j.

Table 1. The variation in current papal rhetoric is positively associated with the variation in current Catholic public opinion

Notes: The fixed coefficient estimates from an OLS multi-level regression are shown with standard errors in parentheses. Statistical reliability is reported as *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. The outcome variable in columns 1–3 is the proportion of papal rhetoric dedicated to a given topic in a given year. The outcome variable in columns 4–6 is the proportion of Catholic's that believe a given topic is the most important in a given year. Additional covariates include $x_{t_{{-}1}}$![]() through $x_{t_{{-}4}}$

through $x_{t_{{-}4}}$![]() (Catholic public opinion in columns 1–3, papal rhetoric in columns 4–6), the logged number of battle-related deaths in the world, global economic growth. The full table with all of the estimated coefficients is reported in the Supplementary Materials.

(Catholic public opinion in columns 1–3, papal rhetoric in columns 4–6), the logged number of battle-related deaths in the world, global economic growth. The full table with all of the estimated coefficients is reported in the Supplementary Materials.

The full model, column 3 in Table 1, accounts for existing levels of global violence and economic prosperity in addition to the temporal trend of Catholic public opinion. Given a 1% change of Catholic public opinion on a certain issue, the Pope is estimated to dedicate 0.38 percentage points more of his rhetoric to the same issue, on average. This is a substantively meaningful effect since the average change of Catholic public opinion between successive years is only 6 percentage points, which constitutes approximately a 2.28 percentage point change associated in papal rhetoric. The Pope only shifts 2.32 percentage points each year, on average, within a given topic. Since the Pope dedicates most of his time to religious content and this proportion of his speech is relatively stable, such a shift represents a meaningful portion of his political rhetoric.

Columns 4–6 in Table 1 investigate the reverse causal process: is Catholic public opinion driven by the proportion of papal rhetoric devoted to a given topic? In each model, papal rhetoric is not a reliable predictor of Catholic public opinion, which lends further evidence to the notion that Catholic public opinion leads papal rhetoric. The lagged coefficients were also not statistically reliable in any of the estimated regression models. As such, we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the relationship between papal rhetoric and Catholic public opinion is zero.

I cannot better model the effect of Catholic public opinion by issue area with this analytical strategy because the “random” effects of the multi-level models ignore the inherent negative correlation between topic categories in both the outcome and input variables. I fully acknowledge that responsiveness may be (and likely is) largely driven by the interactive effect between issue area and Catholic public opinion. I attempt to account for this in the research design in study 2, and I discuss the low correlation between Catholics' political preferences by issue area and their dedication to the Church in the Supplementary Materials.Footnote 12

There may also be a concern that the Pope is responsive to public opinion more generally, rather than responding specifically to Catholic public opinion. To address this, I create an indicator of total public opinion and “non-Catholic” public opinion for each topic for each country-year. The sample of countries is the same for both indicators of total and Catholic public opinion. Ultimately, the indicator of total public opinion is highly correlated with Catholic public opinion (r = 0.92, α = 0.05). This is not necessarily surprising given that the countries included in the sample generally have a large proportion of Catholics. However, when Catholic public opinion is replaced with total public opinion or non-Catholic public opinion exclusively, the relationship between public opinion and papal rhetoric is no longer statistically reliable. The results, which are included in the Supplementary Materials, further suggest that if the Pope is responsive, he is being responsive to Catholics' mass preferences and not merely following general trends in international public opinion.

In total, these results provide only correlational support for the hypothesis that the Pope is responsive to the concerns of his followers. Despite the variety and volume of papal data, the observed period is far too narrow to make any definitive causal claims about the direct or lagged effect of Catholic public opinion on papal rhetoric. And, the periods for each Pope are also too small to make any meaningful inferences about individual Pope's rhetoric. These findings, however, support the theoretically derived implication that the Pope, an unelected centralized leader, should still be responsive to his followers' concerns. Next, I outline the design and results of the survey experiments to show that the Pope's motivation to be politically responsive is likely driven by his followers, especially dedicated supporters, who react positively to symbolic responsiveness.

Study 2: does papal responsiveness increase support?

The survey was conducted by the international polling firm Respondi, and it was carried out among a nationally representative quota sample from each Brazil and Mexico (approximately N = 2,500 in each country for a total N = 5,000). Respondi employs a combination of online and offline recruitment methods to ensure that the panels can be used for conducting representative surveys (Respondi, 2015). The two samples are nationally representative by age, gender, and region derived from census data to ensure that the sample margins match those in the target populations. Respondents who participated in the online survey experiment all self-identified as Catholic. Respondents were provided ethical compensation for their services at a rate of $12 per hour, and the average response time was approximately 10 minutes. The Supplementary Materials include tables, figures, and further description of the two samples.

Survey experiment design

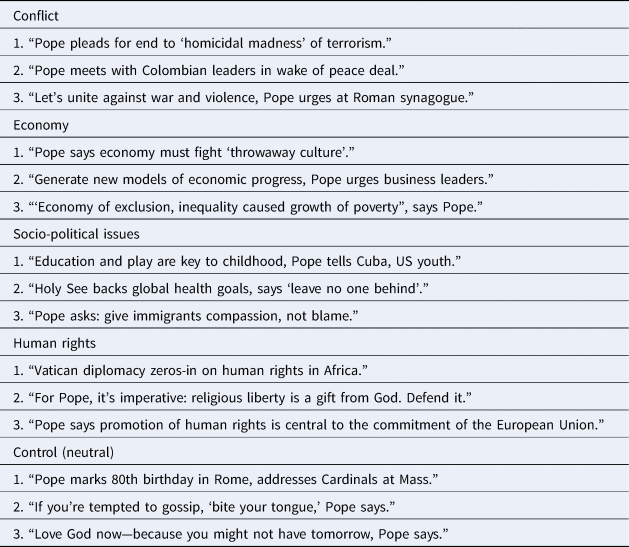

The experimental manipulation presents participants with three selected news headlines outlining recent statements made by the Pope that match the topic categories used in study 1 (conflict, human rights, socio-political issues, economy, and control/religious matters). The three news headlines associated with each of the five topics are found in Table 2. These messages are meant to represent the typical language content and phrasing used in the media regarding the Pope's statements. Further, the statements are political in nature because we are interested in how Catholics react to non-religious responsiveness, not recitals of scripture, and whether that has deleterious effects for the Church.

Table 2. News headlines summarizing papal rhetoric for each issue area

Notes: The survey was translated from English to Spanish (for Mexican respondents) and Brazilian Portuguese (for Brazilian respondents). The original survey experiment was back-translated by two native speakers for each language. The translated versions of the survey experiment text that respondents viewed are available in the Supplementary Materials.

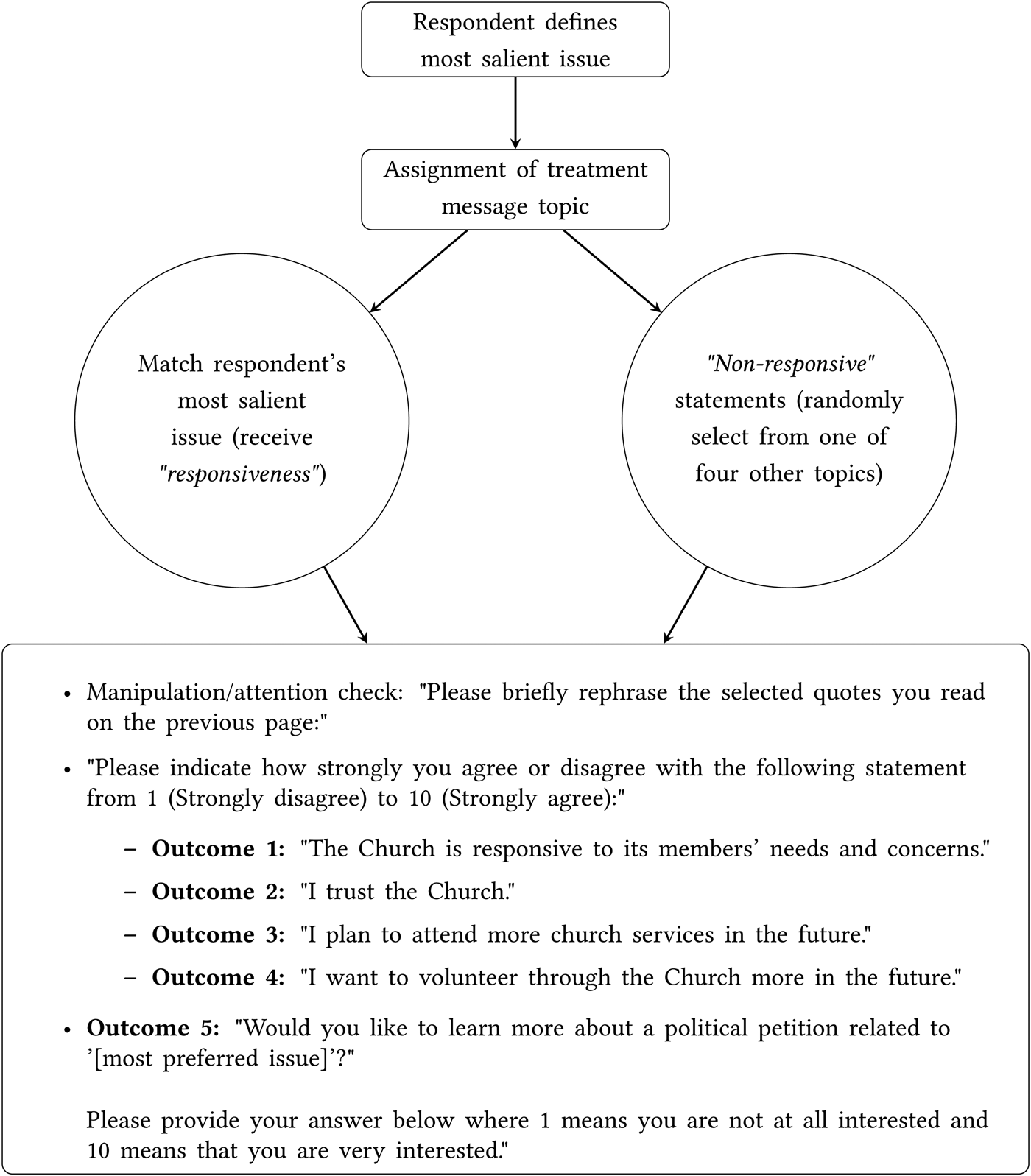

To isolate the effect of papal responsiveness on respondents' organizational attitudes and support, respondents are randomly assigned to receive news stories about either (1) a topic that they believe is most important (the “responsive” treatment), or (2) one of the four other issue areas (“non-responsive”). Within those respondents that receive “non-responsive” messages, there is an even probability of assignment to each topic, so it is possible to examine if one topic has an especially negative impact on respondents' preferences and behavior. The random treatment assignment is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Respondent assignment to treatment and outcome responses for survey experiment of Catholics.

Before viewing the news headlines, respondents provide pre-treatment information regarding their age, gender, region of residence, and political preferences among issues similar to the news treatments. I also ask respondents on a scale from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (10) whether “The Church should advocate on issues related to [insert most salient issue from previous question]” to capture if participants have a disagreement with the Church regarding their most concerning issue. After viewing the news headlines, respondents answer an open-ended manipulation check to determine how attentive they are to the experimental task (Ziegler, Reference Ziegler2022). Then, participants express the degree to which they think the Church is responsive, the degree to which they trust the Church and the degree to which they anticipate increasing their organizational as well as political participation.

All of the outcome questions that gauge respondents' levels of organizational trust and participation are presented in the bottom section of Figure 1. The order in which the outcomes are presented is randomized. The outcome responses are designed to represent real-world actions that respondents can take across different forms of organizational trust and participation to test the limits of members' anticipated support from responsiveness.

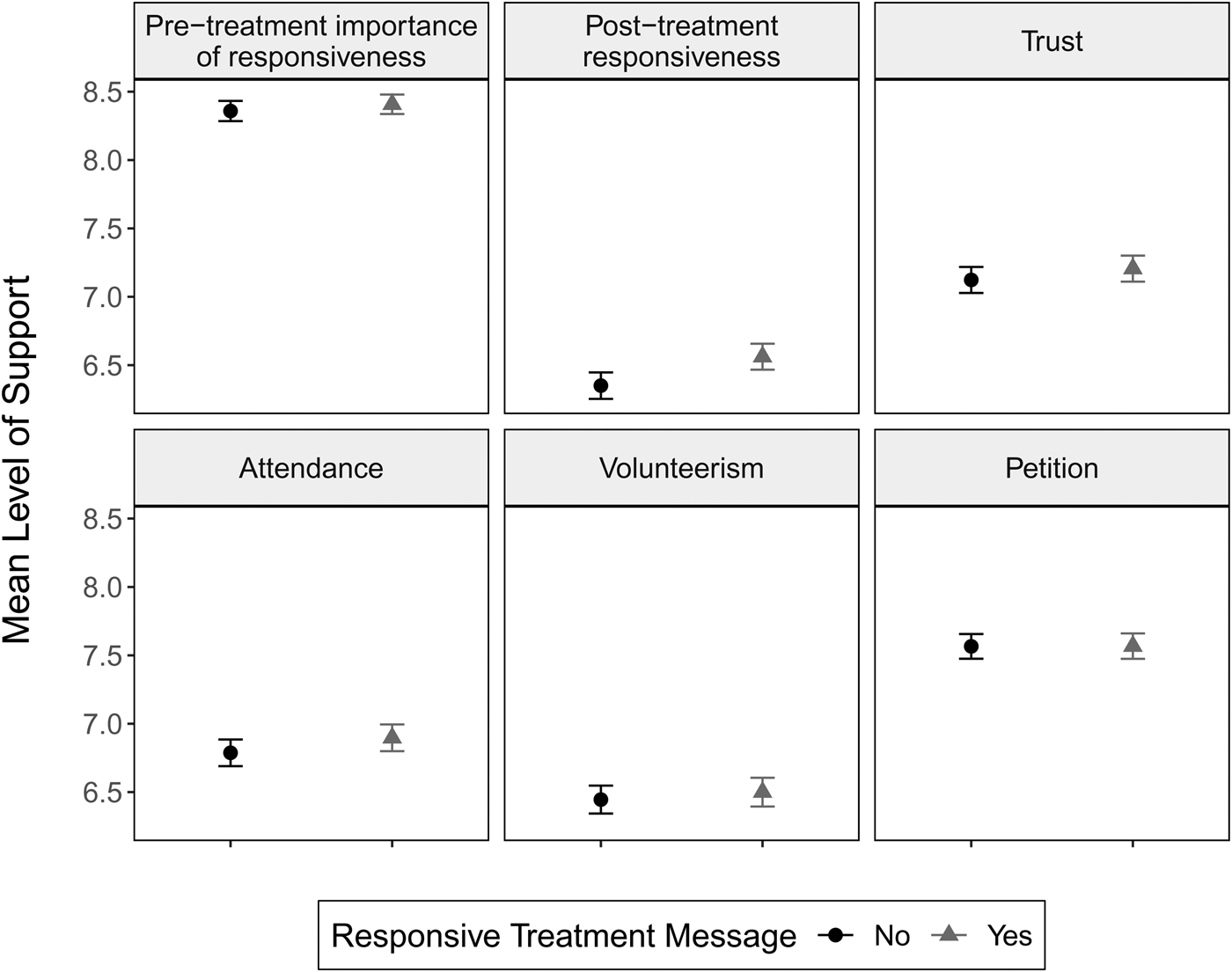

Study 2 results: responsiveness increases Catholics' support

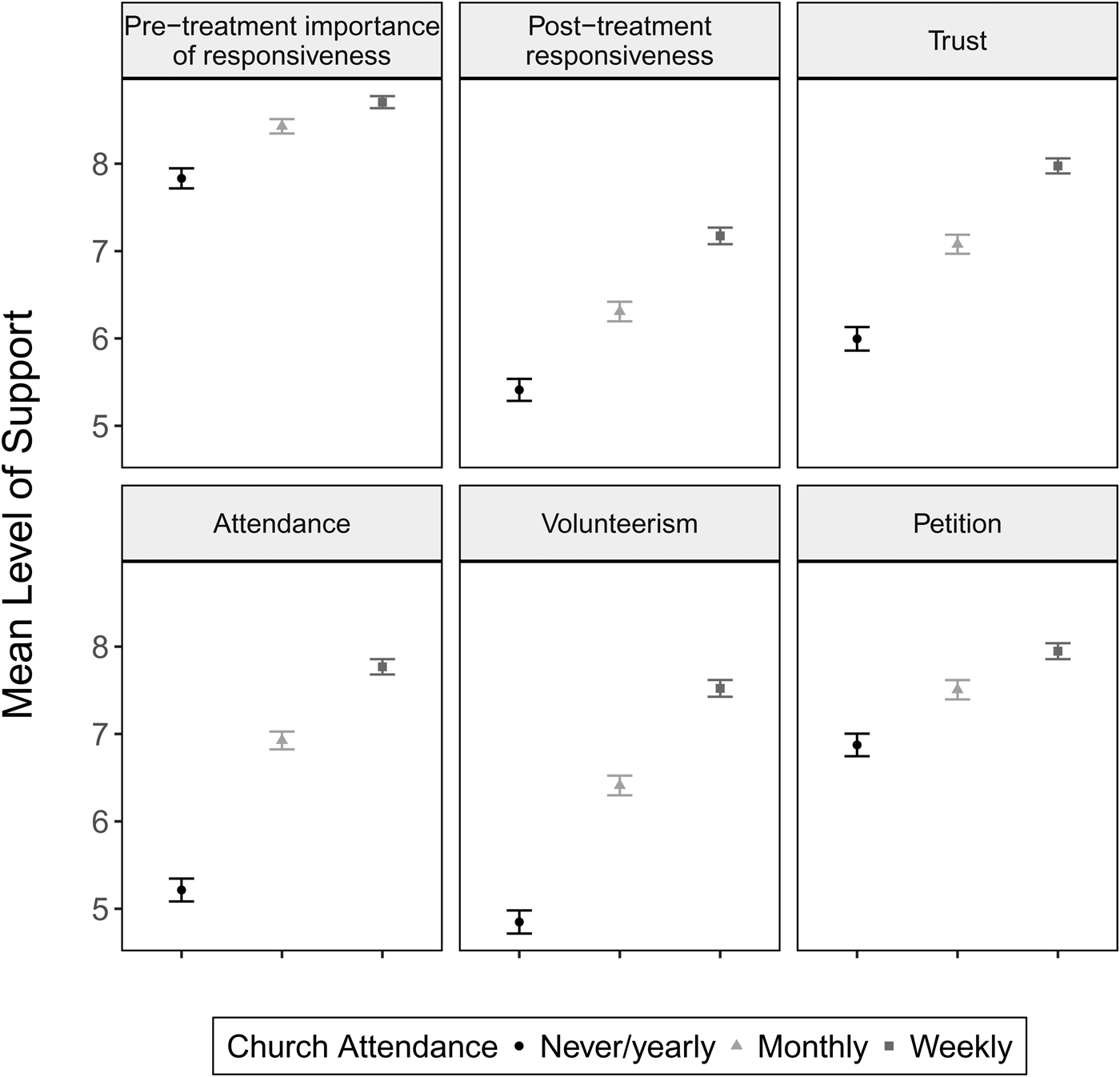

The unconditional mean response of each treatment group for each outcome question is shown in Figure 2. Each panel of Figure 2 represents one survey question, the last five of which were asked post-treatment. The average level of support by respondents who received the “responsive” treatment is represented by the grey triangles. To establish a baseline demand for responsiveness, and to ensure that the textual treatments were in fact assigned randomly, the far left column of Figure 2 shows that there is not a reliable difference in the perceived importance of responsiveness prior to viewing the news headlines between respondents that receive responsive messages and respondents that do not receive responsive messages.

Figure 2. Catholics, in general, are more likely to increase their organizational trust and participation when they receive politically responsive statements from the Pope.

Notes: The unconditional, pooled means are displayed with 95% confidence intervals. For all outcomes, the number of respondents asked was 5,006. Some respondents did not answer every outcome, but the missingness does not exceed 3% in any of the treatment groups for any response question.

The middle panel in the top row of Figure 2 shows that respondents who receive papal responsiveness increase their perception of how responsive the Church is by 0.21 points, on average. Based on a two-tailed t-test, the null hypothesis that the difference in means equals zero can be rejected at the 95% confidence interval. Similarly, respondents that receive papal responsiveness, on average, agree more strongly with the statement that “I trust the Church” by 0.08 points. The mean difference between respondents that receive papal responsiveness and those that do not is also positive for the within-organization behavioral outcomes, such as whether respondents are interested in attending church services in the future and volunteering through the Church. Importantly, however, internal responsiveness from the Pope does not seem to induce outward external political participation, as seen in the last column of Figure 2.

Though the marginal treatment effect appears to increase organizational trust as well as participation, it is not possible in all of the outcome variables to reject the null hypothesis that the average response for respondents that receive non-responsive messages is greater than or equal to the average response for those that receive responsive messages (one-tailed t-test α = 0.05, H 0: x Treatment ≥ x Treatment; H a: x Treatment < x Treatment). This may be due to a lack of precision, a null effect, or a heterogeneous effect driven by respondents' existing support.Footnote 13 Though a statistically reliable difference may be difficult to detect overall, the survey is designed to investigate the heterogeneous effect of Catholics' prior support and participation for the Church on organizational trust and participation when they receive papal responsiveness.

As such, Figure 3 reports the conditional group means by attendance. Catholics who attend church services more frequently are more likely to expect responsiveness from the Church and lend greater overall support, in comparison to less frequent attendees. In the top left panel of Figure 3, when asked “On a scale from 1 (Not at all important) to 10 (Extremely important), how important is it to you that the Church responds to the needs and concerns of its members?”, Catholics that attend church weekly are more likely to place greater importance on responsiveness than those that attend monthly, and even more so than those that attend yearly or never. This trend holds for all the outcome questions.

Figure 3. Members that attend church services more frequently exhibit higher levels of organizational trust and support, on average, regardless of whether they receive responsive papal messages or not.

Notes: The conditional, pooled means by attendance rate are displayed with 95% confidence intervals. For all outcomes, the number of observations is limited to complete cases, which results in N = 4,431. The measure of church attendance is a three-group factor [never/yearly, monthly, weekly].

To test for a non-linear treatment effect, I estimate an OLS regression model with an interaction between respondents' anticipated organizational support and the amount of time that they already spend at church. I also estimate the models with other pre-treatment characteristics that may alter the direct effect of responsiveness on respondents' organizational trust and participation. This includes traits such as age, gender, duration of membership, expected responsiveness from the Church, desired advocacy by the Church, as well as their political preferences.

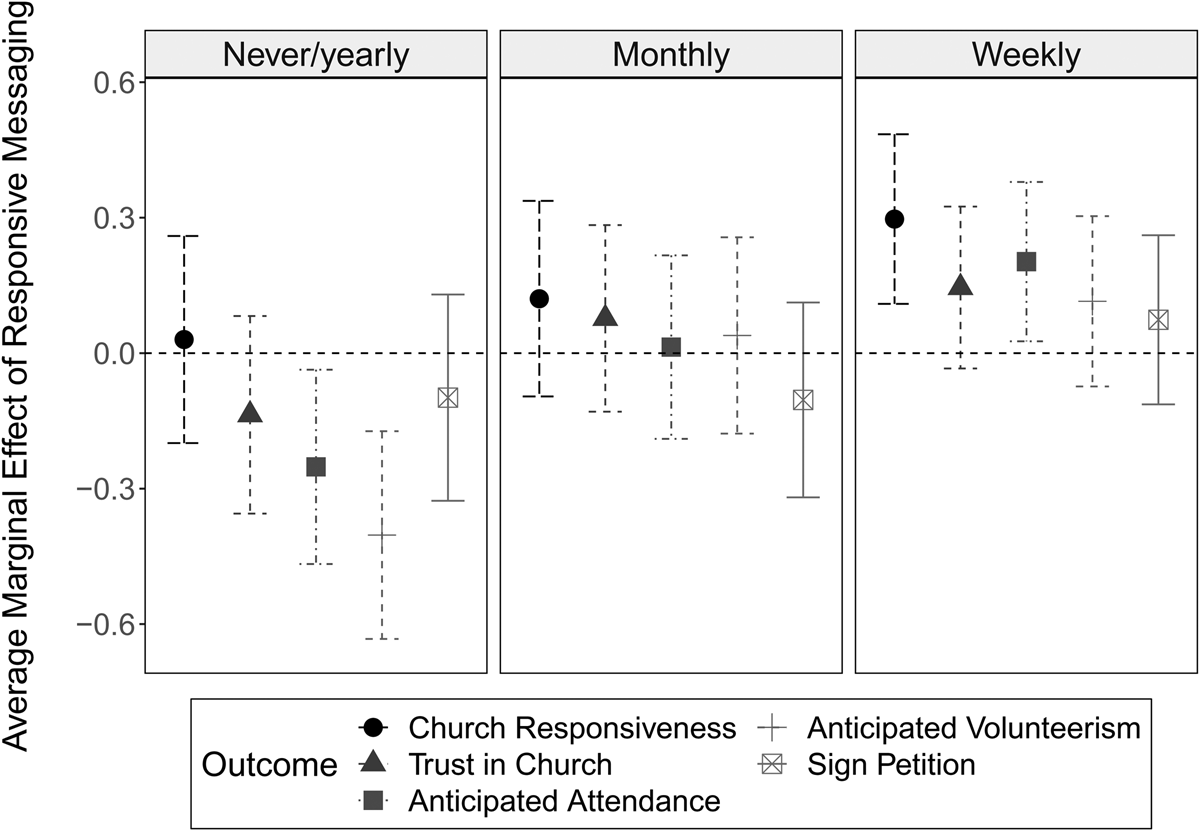

For ease of interpretation, I plot the average marginal effect of responsive papal statements by respondents' church attendance in Figure 4. First, dedicated members (those that attend church weekly) are more likely to state that the Church is responsive when they receive responsive messaging. These respondents are represented in the far right column of Figure 4, and perceived post-treatment responsiveness is the first outcome and point in the far right column. Dedicated members are also more likely to increase their anticipated future attendance of Church services, which is vital for individual parishes, and the central apparatus, to maintain financial and political strength. When asked how strongly respondents agree with the statement, “I plan to attend more church services in the future,” members that attend church services weekly are more likely to increase their support if they receive responsiveness.

Figure 4. Dedicated, core members increase their perceived organizational responsiveness, trust, and participation when they receive responsiveness from the Catholic Church.

Notes: The point estimates represent the average marginal effect of responsive papal messaging (“responsive” news headline treatment) on organizational trust and participation outcomes interacted with respondents' attendance. 95% confidence intervals are displayed. As a robustness check, I re-estimate the regression model with an index of post-treatment church involvement based on a principal component analysis (PCA) of the five outcome questions. The results, which are presented in the Supplementary Materials, depict a similar story: anticipated involvement in the Church increases with papal responsiveness, but papal responsiveness does not positively or negatively impact anticipated political involvement. A table of the full estimated coefficients from the regression model is presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Holding all of the respondents' pre-treatment characteristics and preferences constant at their pooled sample means, the estimated average treatment effect of receiving papal responsiveness is associated with a 0.44 point increase in the strength of their anticipated attendance of church services. Although the marginal treatment effects are not statistically distinguishable from zero at the 95% confidence interval, the estimated coefficients for the other behavioral outcomes are all positive. These findings suggest that respondents' are more willing to view the Church as responsive, and more willing to participate in the Church, when they receive responsive papal statements.

Interestingly, among Catholics that attend less frequently (monthly and never/yearly), the average respondent did not view the Church as any more responsive when they received responsive papal rhetoric. In fact, infrequent attendees (displayed in the far left column of Figure 4) were less likely when they received responsiveness to trust the Church, less willing to attend church in the future, less willing to volunteer through the Church, and less willing to sign a petition on an issue respondents' deem salient.

While the impact of responsiveness should be greater among dedicated members, it is surprising to find that less dedicated members actually decrease their support and participation when they receive responsiveness. One explanation is that when passive members see that the Pope is responsive, it signals that the Pope already prioritizes that issue and action is unnecessary (Levine and Kam, Reference Levine and Kam2017; Butler and Hassell, Reference Butler and Hassell2018). If this is the case, members who agree with the Pope, not members that disagree, should be less likely to support the Church when they receive responsiveness.

Another possible explanation, however, is that individuals' pre-treatment political preferences may not be aligned with those of the Pope. In other words, respondents may not want the Church to be responsive to their concerns because they disagree with the Church regarding that issue. It may be that if a respondent disagrees with the Pope along a given issue dimension, and a respondent receives a message on that issue, the respondent may actually have a negative reaction and discount their organizational participation and trust. This disagreement, moreover, may be the reason why they attend church less. If this is the case, members that disagree with the Pope, not members that agree, should be less likely to extend support to the Church when they receive messages on their “most important” issue. I attempt to distinguish between these mechanisms by utilizing a survey item that measures whether individuals agree with the Church on the issue that they were randomly assigned to view as part of the treatment assignment.

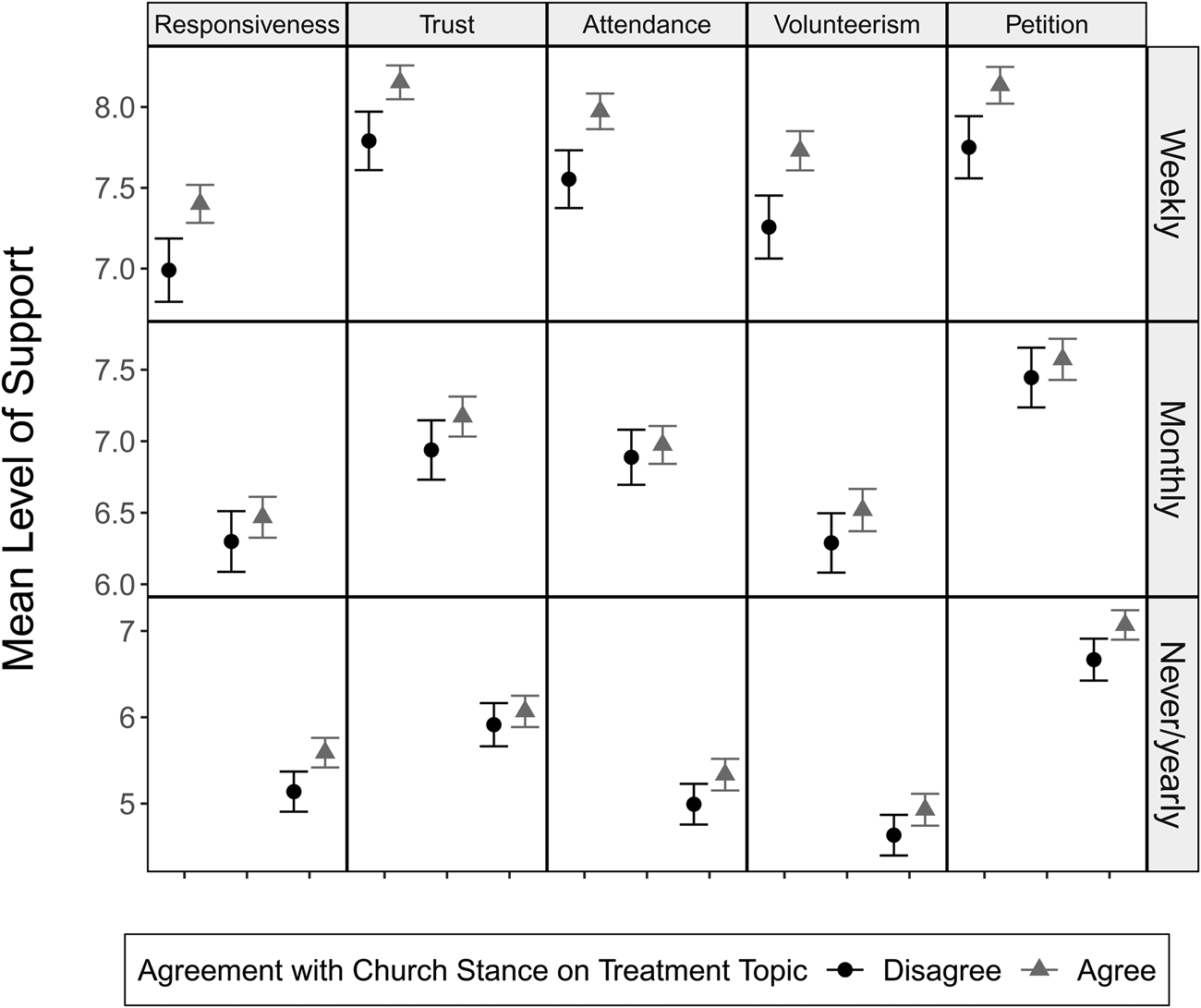

The conditional means by issue agreement are presented in Figure 5. Respondents, in general, decrease their support when they receive papal statements that do not match their stated preference position on that given policy dimension. The columns of Figure 5 represent the five outcome questions, and the rows group respondents by their self-declared church attendance. The mean level of support extended by participants that agree with the Church regarding the issue that they viewed are represented by the grey triangles, while those that disagree are displayed by the black points in Figure 5. Unsurprisingly, the largest difference in support between those that agreed and disagreed with the Church regarding the news headlines they viewed is among respondents that attend weekly (top row of Figure 5). Still, less dedicated members increase their support when they receive messages from the Pope that take positions they potentially agree with, though the difference in means is not always statistically reliable.

Figure 5. Members, on average, reduce their support when they receive papal messages they disagree with.

Notes: The conditional, pooled means by issue agreement are displayed with 95% confidence intervals. For all outcomes, the number of observations is reduced because not all respondents supplied their position preferences (N = 4,195). A respondent is “in agreement” with the Church when they indicate in the pre-treatment policy preferences a similar position to the Church. For instance, the Church certainly agrees with the statement that we should “promote and defend human rights.” If a respondent “Agrees” or “Strongly agrees” with that statement, they are “in agreement” with the Church.

As such, I take into account members' issue saliency by interacting respondents' issue agreement with, (1) whether that issue is of high priority to respondents (responsive to their concerns), and (2) respondents' organizational commitment. I re-estimate the regression models with an interaction between the treatment (papal responsiveness), church attendance, and whether respondents agree with the Church along the issue dimension that the papal statements discuss.

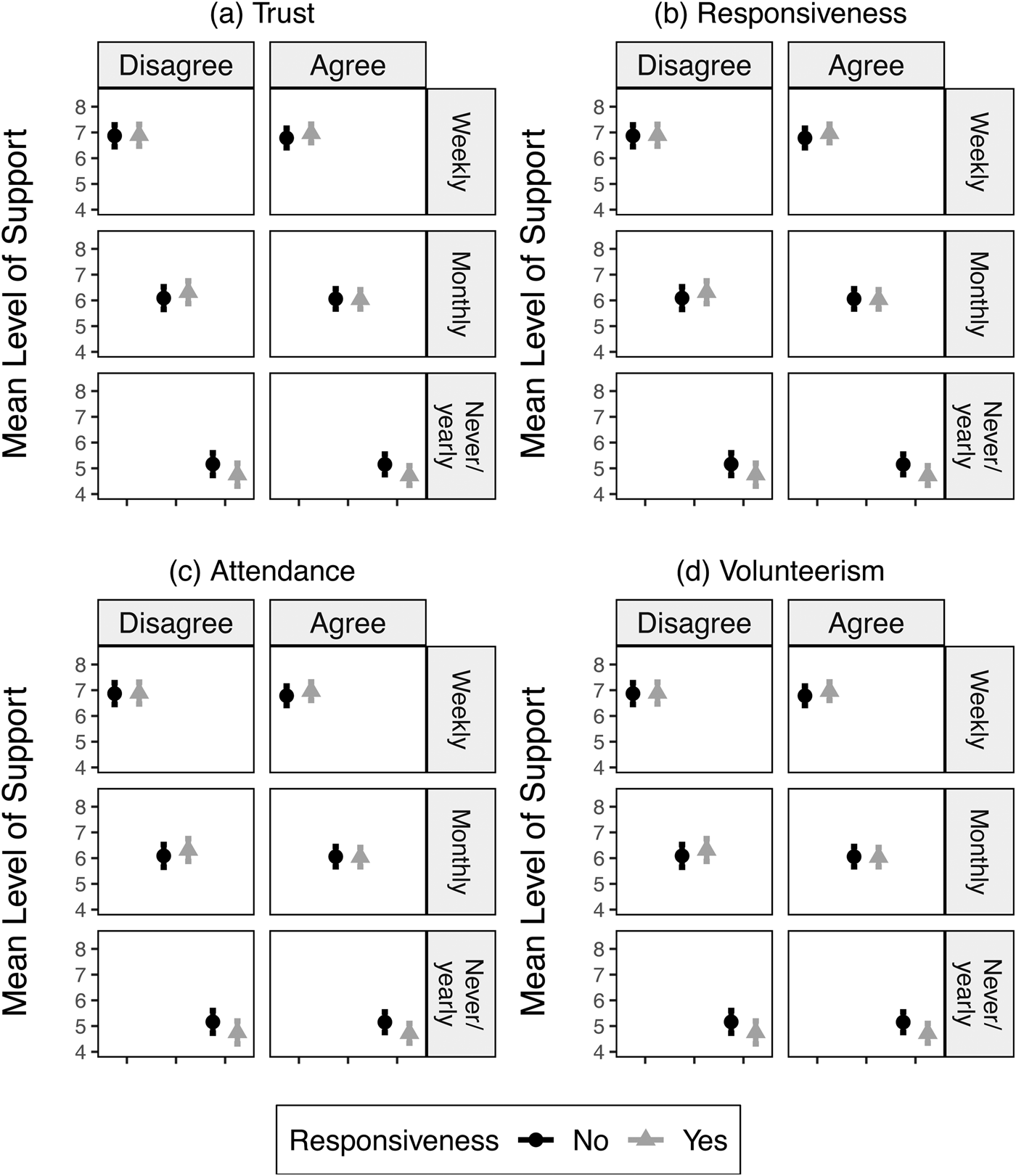

Figure 6 highlights the heterogeneous effect of responsiveness when accounting for whether individuals agree or disagree with the Church on their most salient issue. Each panel in Figure 6 displays one outcome, distinguishing between those respondents that agreed or disagreed with the news headlines they read (in the columns) by their self-reported attendance (in the rows). The results suggest that the strength of agreement with the Church on an issue may condition the impact of responsiveness on the propensity of respondents' to increase their organizational support. Nevertheless, none of the within sub-group comparisons were statistically differentiable from each other.

Figure 6. Marginal effects of the triple interaction between church attendance, responsiveness, and agreement with papal statements.

Notes: The point estimates represent the average marginal effect of responsive papal messaging (“concordant” news headline treatment) on organizational trust and participation outcomes by respondents' duration of membership (using the full categories) in the Catholic Church. 95% confidence intervals are displayed. The groups were also not statistically distinguishable from each other in the last outcome (“Petition”), which was omitted. Tables of the estimated coefficients are found in the Supplementary Materials.

It appears that those members that attend Church frequently and disagree with the message they viewed do not decrease their trust and participation if they receive a message on an issue they deem important. Dedicated members may, therefore, be more likely to extend goodwill toward the Church when they disagree with the Pope, or even adjust their preferences to reflect the Pope's rhetoric. In this sense, it is not clear if dedicated members actually change their opinions, but it at least appears that they are willing to set those opinions aside for the Church.

Conversely, infrequent attendees do appear to negatively react to messages that they deem salient and that they are in disagreement with the Church. This suggests that their lack of religious participation may be connected to their disagreement with the Church. Yet, infrequent participants that receive messages that they view as important are less likely in general, regardless if they agree with the Church, to support the Church. As such, this trend may be driven by infrequent participants who believe that the Pope should not be engaged in political speech.

However, there is minimal evidence that respondents' desire for the Church to advocate politically is linked to church attendance (r = 0.138 [0.107, 0.169]). In the Supplementary Materials, I re-estimate the regression model to include an interaction between respondents' desire for the Church's advocacy, attendance, and responsive messaging. Though infrequent attendees who believe the Church should not advocate politically extend less support to the Church when they receive “responsive” messaging in comparison to “non-responsive messages,” the differences are not statistically distinguishable. The overall results of study 2 confirm that members' aggregate positive reaction to responsiveness is primarily driven by dedicated members that extend their already high support when they receive responsiveness. The findings are in line with Djupe and Gilbert (Reference Djupe and Gilbert2008) who note that “disapproval does not threaten the integrity of the organization if the primary benefits are provided adequately to members” (57).

Implications beyond religious groups

Given the important role of interest groups and NGOs in global politics, especially religious groups, the unelected leaders of these centralized organizations are typically thought to have tremendous power over supporters' preferences and behavior. I argue, however, that even when there are few formal accountability mechanisms, there are still incentives for centralized religious leaders to be responsive. In the case of the Catholic Church, I provide evidence from observational data and survey experiments that suggests the Pope is prompted to discuss and legitimize issues that members believe are important because dedicated Catholics respond positively to messages that address their concerns.

Though the Catholic Church is only one example, the findings establish implications for future research on the ability of non-governmental groups to represent broad interests in international politics. While many view interest groups as an efficient vehicle to aggregate political preferences, not all scholars have viewed interest groups as beneficial for representation or political responsiveness. In fact, interest group liberalism suggests that diffuse public interests are not reflected in governmental outcomes when authority is delegated to administrative agencies that rely on interest groups in which politicians associate (Lowi, Reference Lowi1979). The theory and results paint a less pessimistic portrait: leaders are responsive, but primarily because members provide resources to the organization.

This responsiveness, however, is most likely limited given the reputational and credibility costs of leaders. In instances when there are extreme changes in public opinion, it may not be feasible or credible for leaders of large, diverse interests to make rapid organizational changes. Voters, for instance, have been shown to respond adversely when candidates change positions over time. In fact, voters who place higher importance on issues are “more, not less, tolerant of candidates who espouse inconsistent positions over time” (Tomz and Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012). This may be consistent with the finding that dedicated Catholics actually increase support when they receive statements on a topic they deem important, but it is a topic in which they disagree with the Church.

Moreover, the depth, scope, and independence of internal regulation vary significantly by organization and sector. The ability or willingness of organizations to hold themselves accountable lies along a “spectrum of accountability mechanisms within which NGOs, especially large NGOs, operate” (Nelson, Reference Nelson2007). For instance, Transparency International has strong internal accountability measures between members, boards, and executives; it selects the governing Board of Directors through national chapters and individual members. Conversely, the organizational leadership of BRAC, one of the largest NGOs in the world, is quite autonomous and there are minimal accountability mechanisms for members (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Hopper and Wickramsinghe2011). Given the size and breadth of the Church's organizational structure, the Pope may be more constrained in the position he takes than leaders of smaller NGOs. However, the Pope may also be less constrained in the issues he prioritizes so symbolic responsiveness may be most useful. Since dedicated members are the most likely to provide additional support when the Pope provides responsiveness, the Pope may be able to speak more freely about topic, but less freely about position.

As such, these findings may then represent a lower bound of organizational responsiveness. One may expect more responsiveness in an organization that has elections for leadership and greater internal and external oversight. Moreover, accountability may be lower in religious organizations more generally because members may not care to hold leaders accountable; they may be motivated to maintain their organizational trust and participation because of their long-held religious associations or beliefs. Though the theory and findings do not provide definitive answers for all organizations across the spectrum of accountability, they prompt new expectations regarding responsiveness for centralized organizational leaders that do not face credible or repeated elections.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048324000105

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Michael Bechtel, Constantine Boussalis, Sarah Brierley, Matthew Gabel, Federica Genovese, Tony Gill, Sera Linardi, Guillermo Rosas, Amy Erica Smith, Margit Tavits, Guadalupe Tuñón, and Carolyn Warner for their comments, as well as participants of the Harvard Experimental Political Science Graduate Student Conference, IRES Graduate Student Workshop, NYU CESS Experimental Political Science Conference, Midwest Workshop in Empirical Political Science II, and seminar participants at Washington University in St. Louis for constructive feedback. Thank you to Ana Barrios, Frank Morejon, Patrick C. Silva, and Juliana Wakim Viola for translation services.

Financial support

This project was supported in part by funding from the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics, as well as the Department of Political Science at Washington University in St. Louis. The experimental studies were approved by the Internal Review Board at Washington University in St. Louis (ID 201805040) in May 2018.

Competing interests

The author has no conflict of interest to report.