INTRODUCTION

Optimal care of people with cancer incorporates the effective management of physical, psychological, social, and existential/spiritual well-being, and strives to alleviate suffering. Our recent systematic review investigating the experience and management of suffering in cancer (Best et al., Reference Best, Aldridge and Butow2014) concluded that spiritual suffering is defined as “an all-encompassing, dynamic, individual phenomenon characterized by the experience of alienation, helplessness, hopelessness, and meaninglessness in the sufferer that is difficult for them to articulate. It is multidimensional and usually incorporates an undesirable, negative quality.” Surrogate terms, antecedents, and consequences of suffering were described and recommendations were made to address spiritual suffering in cancer patients. However, a reliable means for assessing suffering is needed in order to achieve this goal.

Potential barriers to recognition of suffering in cancer patients include the difficulty patients have in articulating their suffering, either due to an inability to find the appropriate vocabulary or an unwillingness to burden others (Boston et al., Reference Boston, Bruce and Schreiber2011; Cherny et al., Reference Cherny, Coyle and Foley1994; Younger, Reference Younger1995). Assistance may be needed to voice the conflict, which is known to be beneficial for the sufferer (Blinderman & Cherny, Reference Blinderman and Cherny2005). However, healthcare workers may not be able to identify patient distress or may be unwilling to acknowledge it due to the biopsychosocial paradigm of Western medicine that ignores the spiritual (Arman et al., Reference Arman, Rehnsfeldt and Lindholm2004; Ferrell, Reference Ferrell1993). Healthcare staff may fail to respond to suffering even if they recognize it (Rodgers & Cowles, Reference Rodgers and Cowles1997), perhaps because of their own death anxiety (Kahn & Steeves, Reference Kahn and Steeves1995). Patients may wait for a cue that never comes or just assume that the staff are too busy to listen (Strang, Reference Strang1997). Some sufferers feel a lack of a “safe space” in which to discuss their fears (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Chamberlain and Khuri2004). This situation highlights the need for reliable tools for assessment of suffering that are not dependent on patients finding the opportunity to voice their distress.

Information about the assessment of suffering in the context of cancer is not easily accessible, nor have the relative benefits and disadvantages of the available assessment tools been compared. (Rodin, Reference Rodin2003). Previous reviews of the assessment of suffering have been limited to the psychological aspects of distress (Carlson & Bultz, Reference Carlson and Bultz2003; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Waller and Mitchell2012; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, McClement and Chochinov2006) or focused on the end-of-life setting (Krikorian et al., Reference Krikorian, Limonero and Corey2013). To address this gap in the literature, we undertook a systematic review of measures of spiritual suffering in people diagnosed with cancer, including currently treated, palliative, and survival populations.

METHOD

Search

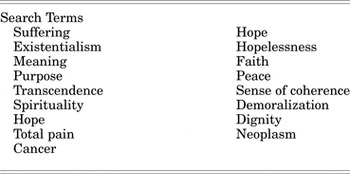

Between April and June of 2012, a systematic search of the literature was conducted to identify all English-language studies published between 1992 and 2012 that focused on assessment of suffering in cancer patients. The following databases were systematically searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, and PSYCINFO. To ensure a sufficiently broad range of conceptualizations of suffering, the search strategy was drafted using an iterative process. Results from preliminary searches were employed to develop a list of concepts identified in the literature as synonymous with suffering, or potentially measurable “symptoms” of suffering and their antonyms (see Tables 1 and 2). The identified search terms (see Table 3) were entered in each of the databases listed above.

Table 1. Terms used synonymously with “suffering”

Table 2. Potentially measurable “symptoms” of suffering (and their “opposites”)

Table 3. Search terms

In order to be included, reports had to: (1) be published in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) focus on adults (aged 18 years and above) who had been diagnosed with cancer; (3) report on outcomes relevant to the review question (i.e., assessment of suffering in cancer patients); and (4) assess tools/instruments that measured either suffering or one of its synonyms or symptoms (as listed in Tables 1 and 2).

Reports were excluded if they: (1) focused on children with cancer, parents of children with cancer, other carers of patients with cancer, or adult survivors of childhood cancers; (2) focused on suffering in patient groups with and without cancer, unless the results were reported separately for cancer patients, or unless the sample was predominantly cancer patients (e.g. 95% or more); (3) were books, book chapters, dissertation abstracts, or conference abstracts; (4) utilized or reviewed measures of interest without reporting the psychometric properties of the instrument; or (5) focused predominantly on spiritual or existential “issues” or “concerns.” Articles fitting within this last category were closely reviewed to determine whether they simply explored spiritual or existential aspects of life that might be impacted (positively or negatively) by a cancer diagnosis and might or might not lead to suffering, or whether they were in fact reporting on “distress,” ”pain,” “crisis,” “anguish,” or another synonym of “suffering.” There are a number of existing review papers that explore the former group of papers (Bresnahan & Merrill, Reference Bresnahan and Merrill2000; Henoch & Danielson, Reference Henoch and Danielson2009; Sulmasy, Reference Sulmasy2006). For these reasons, only the second group of papers were included in the present review.

All retrieved articles were reviewed against the selection criteria, and manual searches were conducted to identify any additional relevant articles not retrieved by the systematic search. Articles that employed or reviewed measures of interest without reporting the psychometric properties of the instrument (and therefore excluded from the search) were separately reviewed to generate a list of additional measures for which instrument development/validation studies were subsequently sought. We attempted as far as possible to include initial and key publications pertaining to the psychometric properties of an instrument, particularly if it was reported in the cancer context. Papers summarizing psychometric properties for a measure across multiple studies were deemed eligible for inclusion if no specific studies in the cancer context were available.

A flowchart presenting the results of the literature search is presented as Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of literature search.

Data Extraction

For each instrument/validation study the following data were extracted by LA and MB:

-

1. Properties of the measure: mode of administration; number of items; response scale; scoring.

-

2. Details of the initial and key validation samples.

-

3. Details of the item development process.

-

4. Information on any domains/subscales.

-

5. Information on reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change.

Criteria for Evaluating Outcome

Individual assessment tools (not studies) were evaluated by LA and MB according to Fitzpatrick et al.'s (Reference Fitzpatrick, Davey and Buxton1998) criteria—namely, appropriateness (is the content of the instrument appropriate to the questions asked?), reliability (does the instrument produce results that are reproducible and internally consistent?), validity (does the instrument measure what it claims to measure?), responsiveness (does the instrument detect changes over time that matter to patients?), precision (how precise are the scores of the instrument?), interpretability (how interpretable are the scores of the instrument?), and acceptability (is the instrument acceptable to patients?). Data pertaining to the psychometric properties of individual measures were extracted, as this was deemed the best way of presenting evidence about the appropriateness of each outcome measure. Evaluations were completed and reviewed individually first, then discussed as a group until consensus was reached. Psychometric properties were rated according to whether the bulk of the available evidence was supportive (+), not supportive (–), or whether assessment of the property had either given contradictory results or not been assessed (?).

RESULTS

Systematic searches of the literature resulted in identification of 90 articles presenting information about 58 measures, which appeared to assess either suffering or one of its synonyms or symptoms. The constructs examined by the eligible measures were: suffering, hopelessness/demoralization, hope, meaning, spiritual well-being, quality of life where a spiritual/existential dimension was included, distress in the palliative care setting and pain, distress or struggle of a spiritual nature. The psychometric properties of the selected measures are set forth in Table 4.

Table 4. Psychometric properties of identified assessment tools

*Key cancer validation sample (where applicable) reference and details listed.

+ =Bulk of the available evidence supportive of construct validity/responsiveness to change of the instrument, – = bulk of available evidence does not support this property, ? = this property has not been assessed or contradictory results.

Suffering

Two measures of suffering for which psychometric properties are available were identified: the Mini-Suffering State Examination (MSSE) (physician completed) (Aminoff et al., Reference Aminoff, Purits and Noy2004) and the Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure (PRISM) (patient completed) (Büchi et al., Reference Büchi, Buddeberg and Klaghofer2002).

Mini-Suffering State Examination (MSSE)

The MSSE is a brief clinician-administered measure of suffering that may be particularly useful with end-stage cancer patients who experience difficulties communicating their needs and/or expressing their suffering (Adunsky et al., Reference Adunsky, Aminoff and Arad2008). It was originally developed in the context of dementia (Aminoff et al., Reference Aminoff, Purits and Noy2004), but preliminary work has been done to explore its psychometric properties in the context of cancer (Adunsky et al., Reference Adunsky, Aminoff and Arad2008).

Content validity is dependent on the clinical judgment of the scale's designers, and there is no indication of further work seeking confirmation of appropriateness and comprehensiveness of items. The 10 items included on this scale do not necessarily encompass the full range of, nor even the most pressing dimensions of, suffering in cancer patients at the end of life, suggesting that this tool may be a useful starting point for measuring some types of suffering, but that further work exploring its content validity may be required.

Reliability overall appears adequate, though some of the items are fairly subjective (e.g., “suffering according to medical opinion” and “not calm”), and this was reflected by lower levels of observer agreement (κ = 0.62 and 0.64) on ratings for these two items (Aminoff et al., Reference Aminoff, Purits and Noy2004).

Construct validity of the scale has been assessed in the context of dementia through correlations with comfort assessment in dying with dementia, but information on validity in the context of cancer is lacking at present. The scale appears responsive to change in the context of cancer, making it a potentially useful tool for monitoring patients and exploring the impact of interventions over time.

Clinician administration is both a strength and a limitation of this measure. It allows consistent assessment of all patients at the end of life, taking into account communication difficulties and avoiding burdening patients. However, clinician administration may also result in biased assessments, especially if clinicians responsible for the care of patients over time overestimate the impact of treatment.

Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure (PRISM, PRISM–R1 and PRISM–R2)

The PRISM was originally intended as a measure of adjustment to illness, but qualitative analyses of content validity suggested its applicability as a measure of suffering (Büchi et al., Reference Büchi, Sensky, Sharpe and Timberlake1998). The advantages of this measure include its brevity, simplicity, and ease of use (Büchi et al., Reference Büchi, Sensky, Sharpe and Timberlake1998). In addition, by not specifying items and domains, it allows for a more subjective assessment of suffering due to illness, however patients might individually define this (Wouters et al., Reference Lehmann, Oerlemans and van de Poll-Franse2011; Wouters et al., Reference Wouters, Reimus and van Nunen2008). Content validity has been explored in a number of qualitative studies (Büchi et al., Reference Büchi, Buddeberg and Klaghofer2002; Wouters et al., Reference Wouters, Reimus and van Nunen2008), and there is evidence for reliability and validity (Büchi et al., Reference Büchi, Buddeberg and Klaghofer2002), although the lack of a gold-standard measure of suffering means that considerable work is necessary to satisfactorily validate this measure (Büchi et al., Reference Büchi, Buddeberg and Klaghofer2002). There are two revised versions of the measure, the PRISM–R1 and PRISM–R2 (Wouters et al., Reference Lehmann, Oerlemans and van de Poll-Franse2011), which provide additional information about the perceived severity of illness and incorporate a slightly revised response format.

The PRISM–R2 has been employed in the context of cancer survivorship, and evidence on the validity of the measure in this context has been presented (Wouters et al., 2011). The PRISM and its variants have been administered both face to face (Büchi et al., Reference Büchi, Buddeberg and Klaghofer2002; Reference Büchi, Sensky, Sharpe and Timberlake1998; Wouters et al., Reference Wouters, Reimus and van Nunen2008) and via mail (Wouters et al., 2011; Wouters et al., Reference Wouters, Reimus and van Nunen2008), although it has been suggested that people with lower levels of education experienced some problems completing this more abstract measure, and face-to-face administration may be preferable (Wouters et al., 2011). The scale's developers also raise the possibility of administering the measure via computer (Büchi et al., Reference Büchi, Sensky, Sharpe and Timberlake1998).

Considerable work has been done exploring the psychometric properties of the PRISM, and it shows some promise as a more subjective measure of suffering, perhaps especially in the context of face-to-face clinical work. Care should be taken in determining an appropriate mode of administration, and more work on definitional validity is recommended.

Recommendation

The PRISM has more evidence of validity and reliability than the MSSE, though more definitional clarity is required. Furthermore, it allows a nondirective approach and provides a quantitative score for serial assessment.

A single “Are you at peace?” item (Steinhauser et al., Reference Steinhauser, Voils and Clipp2006) was identified as a measure of spiritual well-being and its validity assessed against other measures of spiritual well-being (see below). However, the authors referred to it as not only a measure of spiritual well-being but also a way of identifying suffering, so this measure should also be considered in the context of measures of suffering. Peace is one of the constructs measured by the FACIT–Sp (see below) in its three-factor version (Canada et al., Reference Canada, Murphy and Fitchett2008; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Canada and Fitchett2010) and could also be considered in this context.

Hopelessness/Demoralization

Seven instruments measuring hopelessness/demoralization were identified: the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Weissman and Lester1974); the despair subscale of the Cancer Care Monitor (CCM) (Fortner et al., Reference Fortner, Okon and Schwartzberg2003); Jacobsen et al.'s Demoralization Scale (Jacobsen et al., Reference Jacobsen, Vanderwerker and Block2006); Kissane et al.'s (Reference Kissane, Wein and Love2004) Demoralization Scale; the Hopelessness Assessment in Illness (HAI) Questionnaire (Rosenfeld et al., Reference Rosenfeld, Pessin and Lewis2011); a clinician-administered single-item screening instrument for hopelessness (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Graham and Viola2004); and the Subjective Incompetence Scale (SIS) (Cockram et al., Reference Cockram, Doros and de Figueiredo2009). The HAI and Kissane et al.'s Demoralization Scale are the most promising for assessing hopelessness and demoralization, respectively, in the advanced cancer context. Both, however, are relatively new measures and require further exploration of their psychometric properties. Other tools may be optimal depending on the research question.

Hope

Five measures assessing hope were identified. These included the Adult Dispositional Hope Scale (ADHS) (Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Harris and Anderson1991); the Herth Hope Scale (HHS)/Herth Hope Index (HHI) (Herth, Reference Herth1991; Reference Herth1992); the Hope Differential (HD)/Hope Differential–Short (HDS) (Nekolaichuk & Bruera, Reference Nekolaichuk and Bruera2004; Nekolaichuk et al., Reference Nekolaichuk, Jevne and Maguire1999); Miller's Hope Scale (MHS) (Miller & Powers, Reference Miller and Powers1988); and the Nowotny Hope Scale (NHS) (Nowotny, Reference Nowotny1989). Based on its brevity, frequency of use, and the availability of validation data in the cancer context, the HHI is optimal as a measure of hope. Note that all the measures listed have relatively high levels of internal consistency, implying that some items may be redundant.

Meaning

Some 20 scales were identified that measured meaning: the Chinese Cancer Coherence Scale (CCCS) (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Ho and Chan2007); the Constructed Meaning Scale (Fife, Reference Fife1995); the meaning/peace subscale of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT–Sp) (Canada et al., Reference Canada, Murphy and Fitchett2008; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Canada and Fitchett2010; Peterman et al., Reference Peterman, Min and Brady2002); the Illness Cognitions Questionnaire (ICQ) (Evers et al., Reference Evers, Kraaimaat and van Lankveld2001); the Internal Coherence Scale (ICS) (Kroz et al., Reference Kroz, Bussing and von Laue2009); the Life Attitude Profile (LAP)/Life Attitude Profile–Revised (LAP–R) (Reker, Reference Reker1992; Reker & Peacock, Reference Reker and Peacock1981); the Life Evaluation Questionnaire (LEQ) (Salmon et al., Reference Salmon, Manzi and Valori1996); the Meaning in Life questions (including the Benefit Finding Scale [BFS]) used by Tomich and Helgeson (Reference Tomich and Helgeson2002); the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ) (Steger et al., Reference Steger, Frazier and Oishi2006); the Meaning in Life Scale (MILS) (Jim et al., Reference Jim, Purnell and Richardson2006); the Meaning in Suffering Test (MIST) (Starck, Reference Starck1983); the Perceived Meanings of Cancer Pain Inventory (PMCPI) (Chen, Reference Chen1999); the Personal Meaning Profile (PMP) (Wong, Reference Wong1998); the Positive Meaning and Vulnerability Scale (Bower et al., Reference Bower, Meyerowitz and Desmond2005); the Purpose in Life (PIL) Test (Crumbaugh & Maholick, Reference Crumbaugh and Maholick1964); the Purposelessness, Understimulation, and Boredom (PUB) Scale (Passik et al., Reference Passik, Inman and Kirsh2003); the Schedule for Meaning in Life Evaluation (SMiLE) (Fegg et al., Reference Fegg, Kramer and l'Hoste2008); the Sense of Coherence (SOC) Scale (Antonovsky, Reference Antonovsky1993); the Sources of Meaning Profile (SOMP)/Sources of Meaning Profile–Revised (SOMP–R) (Reker, Reference Reker1996); and the World Assumptions Scale (Janoff-Bulman, Reference Janoff-Bulman1989). The optimal measure of meaning will vary depending on the purpose and context of the assessment. However, for assessing the spiritual dimension of global meaning, the FACIT–Sp should be considered optimal, and the LAP–R should be considered a strong candidate when exploring the relationship between global meaning and other variables. Optimal measures for assessing situational meaning will vary depending on the specific context and the construct to be assessed.

Spiritual Well-Being

A total of 11 measures assessing spiritual well-being were identified. These included a short “Are you at peace?” item (Steinhauser et al., Reference Steinhauser, Voils and Clipp2006); the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT–Sp) (Canada et al., Reference Canada, Murphy and Fitchett2008; Murphy et al., Reference Murphy, Canada and Fitchett2010; Peterman et al., Reference Peterman, Min and Brady2002); the JAREL Spiritual Well-Being Scale (Hungelmann et al., Reference Hungelmann, Kenkel-Rossi and Klassen1996); a Linear Analogue Self-Assessment (LASA) item for spiritual well-being (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Piderman and Sloan2007; Locke et al., Reference Locke, Decker and Sloan2007); the Peace, Equanimity, and Acceptance in the Cancer Experience (PEACE) Scale (Mack et al., Reference Mack, Nilsson and Balboni2008); the Self-Transcendence Scale (STS) (Reed, Reference Reed1991; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Burton and Griffin2010); the Spirit 8 (Selman et al., Reference Selman, Siegert and Higginson2012); the Spiritual Health Inventory (SHI) (Highfield, Reference Highfield1992); the Spiritual Perspective Scale (SPS) (Reed, Reference Reed1987); the Spirituality Transcendence Measure (STM) (Leung et al., Reference Leung, Chiu and Chen2006); and the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) (Ellison, Reference Ellison1983; Sherman et al., Reference Sherman, Xiang and McSherry2005). The FACIT–Sp may be optimal for assessing spiritual well-being in the cancer context. Its advantages include its development and validation in a large cancer population, its brevity, the frequency with which it is used in the context of cancer, and the substantive data available about its psychometric properties and to facilitate interpretation.

Quality of Life

Nine multidimensional measures of quality of life that included a spiritual/existential dimension were identified. These included the Hospice Quality of Life Index (HQLI) (McMillan & Weitzner, Reference McMillan and Weitzner1998); the Long-Term Quality of Life (LTQL) instrument (Wyatt et al., Reference Wyatt, Kurtz and Friedman1996); the McGill Quality of Life (MQoL) Questionnaire (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Mount and Bruera1997; Reference Cohen, Mount and Tomas1996); the Quality of Life at the End of Life–Cancer (QUAL–EC) Scale (Lo et al., Reference Lo, Burman and Swami2011); the Quality of Life Concerns in the End of Life (QoLC–E) Scale (Samantha et al., 2005); the Quality of Life for Cancer Survivors (QoL–CS) Scale (Ferrell, 1996); the Quality of Life Index (QLI)/Quality of Life Index–Cancer Version (QLI–CV) (Ferrans, Reference Ferrans1990; Ferrans & Powers, Reference Ferrans and Powers1985, Reference Ferrans and Powers1992); the Skalen zur Erfassung von Lebens Qualitat bei Tumorkranken–Modified Version (SELT–M) (van Wegberg et al., Reference van Wegberg, Bacchi and Heusser1998); and the World Health Organization's Quality of Life Measure (WHOQoL–100) Spirituality/Religion/Personal Beliefs (SRPB) subscale (den Oudsten et al., Reference den Oudsten, van Heck and van der Steeg2009; WHOQoL, 2006). For multidimensional quality-of-life measurement incorporating an existential or spiritual domain, the MQoL questionnaire or FACIT–Sp appear optimal because substantive data are available about psychometric properties and interpretation in the cancer context.

Distress in the Palliative Care Setting

Two measures specifically assessing distress in the palliative care setting were identified: a clinician-administered single-item screening instrument for assessing desire for death, the Structured Interview for Symptoms and Concerns (SISC) (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Graham and Viola2004), and the Schedule of Attitudes toward Hastened Death (SAHD) (Rosenfeld et al., Reference Rosenfeld, Pessin and Lewis2011; Reference Rosenfeld, Breitbart and Stein1999). The latter questionnaire appears promising for assessing desire for death in the context of advanced cancer, though further validation in a larger sample is recommended.

Pain, Distress, or Struggle of a Spiritual Nature

Two measures assessing pain, distress, or struggle of a spiritual nature were identified: the Existential Loneliness Questionnaire (ELQ) (Mayers et al., Reference Mayers, Khoo and Svartberg2002) and the Spiritual Distress Scale (SDS) (Ku et al., Reference Ku, Kuo and Yao2010). Further research validating these measures in larger cancer samples is necessary before either of these measures can be recommended.

DISCUSSION

Our review revealed that a number of instruments are suitable for measuring the various analogues of suffering but that challenges remain in this field, in part as a function of the complexity of suffering itself. Definitions of suffering and clear articulation of the aspects of suffering targeted by individual measures are essential. The multidimensional and individual nature of suffering should be taken into account when considering its assessment, as should its variance dependent on culture and context (Cassell, Reference Cassell1982; Wein, Reference Wein2011). Many authors have noted the importance of context, including cultural, historical, and social factors that impact on the meaning an individual gives to an experience (Barton-Burke et al., Reference Barton-Burke, Barreto and Archibald2008; Chio et al., Reference Chio, Shih and Chiou2008; Williams, Reference Williams2004). Holistic assessment rather than a narrow focus on individual symptoms is recommended.

Further, it was evident from the review that information about the strengths, limitations, and psychometric properties of available measures for the specific use proposed should always be consulted when choosing an assessment tool. Such information will enable users to make an informed decision about the appropriate measure for any specific purpose, and/or may identify measures that might be further developed and assessed for validity. Lack of a gold-standard measure of suffering means that considerable work is necessary to satisfactorily validate these measures (Büchi et al., Reference Büchi, Buddeberg and Klaghofer2002).

Due to the individual nature of suffering and the manifold potential sources involved (Best et al., Reference Best, Aldridge and Butow2014), being able to assess both the personal elements of suffering for the patient as well as the objective would be advantageous. Measures to assess suffering may therefore be particularly useful if they include a subjective component (e.g., the PRISM, the SMiLE, the Hope Differential–Short, and the single item “Are you at peace?”); they may need to be supplemented by open questions and alertness to the nonverbal and verbal cues of the patient. Care should be taken in determining the appropriate mode of administration, and face-to-face administration would be considered preferable in populations with varying educational levels.

The distress of cancer patients who are suffering will often take a toll on their reserves that will make lengthy assessment tools burdensome in the clinical context. Further research should be conducted into the psychometric properties and usefulness of single-item measures of suffering, with potential use for clinical application as a screening tool and door-opener for discussion of patient concerns (Bayes et al., Reference Bayes, Limonero and Barreto1996). Potentially useful items include “Are you at peace?” and “How long did yesterday seem to you?” (Bayes et al., Reference Bayes, Limonero and Barreto1996).

Despite the numerous measures available for the assessment of suffering and its synonyms and symptoms, more work is needed to validate these tools in the cancer milieu. However, the wide range of assessment instruments currently under development will allow the clinician to focus on specific aspects of suffering to suit their clinical context.

LIMITATIONS

There are a number of limitations to the current review that should be acknowledged when interpreting results.

First, the search strategy adopted for our review was designed so as to allow for the synthesis of common elements across a number of concepts highlighted in the existing literature as potentially synonymous with suffering. Including existential and spiritual suffering/distress allowed due attention to be paid to an important and often overlooked dimension of suffering. The review authors believe that this broad synthesis of the common elements of these constructs enhances our understanding of the nature of suffering in the context of cancer; however, these concepts are not always seen as identical. The potentially useful nuances of each individual concept have therefore not been fully explored in this review.

Second, the search for measures focused on a list of “synonyms” and “symptoms” of suffering generated by an iterative review of the literature. This strategy allowed for the consistent inclusion of any measure targeting hope, meaning, or spiritual well-being; this appeared the most reliable and parsimonious of the possible search strategies identified.

Third, holistic care in the cancer context involves not only the patient but also the family as the unit of care. The suffering of families and carers is deserving of attention; however, feasibility constraints precluded addressing this important issue within the scope of the current review.

CONCLUSION

This report reviews research published between 1992 and 2012 to identify validated tools that measure spiritual suffering or its symptoms in cancer patients. Some 90 articles were identified that yielded information about 58 measures. The constructs examined were: suffering, hopelessness/demoralization, hope, meaning, spiritual well-being and quality of life where a spiritual/existential dimension was included, distress in the palliative care setting, and pain, distress or struggle of a spiritual nature. The psychometric properties of these measures were compared. The PRISM shows promise as a direct measure of the burden of suffering due to illness, in terms of ease of use, and the possibility of capturing individual aspects of suffering. A number of other measures with promising psychometric properties are now available to measure the particular dimensions of spiritual suffering.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project received funding from the Australian Government through Cancer Australia.