1 Introduction

In this article we explore the range of aspectual and quantificational readings that are available to two kinds of deverbal nominalizations in English, conversion nouns and -ing nominals. By quantificational readings, we mean the ways in which conversion and -ing nominalizations are construed as either count or mass (a kick, too much kick, a kicking, too much kicking). By aspectual interpretations we mean the ways in which we construe nominalizations as referring to on-going or unbounded events, as in (1), or as completed or bounded events, as in (2), among other distinctions that we will discuss in what follows:

(1) Swimming became a life-long habit for her.

(2) She enjoys a swim every morning.

Although this is not a subject that has received extensive treatment in the literature, observations and predictions concerning the aspectual and quantificational interpretations of various nominalizations have occasionally figured in philological literature (Biese Reference Biese1941), philosophical literature (Mourelatos Reference Mourelatos1978), in reference works (Grimshaw Reference Grimshaw, Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011; Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013), in the non-generative and cognitive/functional literature (Langacker Reference Langacker1987, Reference Langacker1991; Brinton Reference Brinton, Bertinetto, Bianchi, Higginbotham and Squartini1995, Reference Brinton1998; De Smet & Heyvaert Reference De Smet and Heyvaert2011; Park & Park Reference Park and Park2017; Maekelberghe Reference Maekelberghe2017; Heyvaert, Maekelberghe & Buyle Reference Heyvaert, Maekelberghe and Buyle2018), and in the generative canon, including Grimshaw (Reference Grimshaw1990), Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2001) and Iordachioaia & Soare (Reference Iordăchioaia, Soare, Bonami and Cabredo-Hofherr2008), among others. To our knowledge, however, there has not been a thorough and comprehensive study of quantificational and aspectual readings of nominalizations in English, so it is worth assessing the descriptive and theoretical claims that have been made in passing and beginning to develop a coherent picture both of the facts and of their theoretical implications. This is what we set out to do here.

Our findings are based on a corpus study of 106 verbs which display both conversion and -ing nominalizations, many of them in both singular and plural. We study the range of readings available for the conversion and -ing forms of those verbs in context, looking at up to 300 tokens each of singular and plural conversion forms and singular and plural -ing nominalizations, a total of over 57,700 instances of nominalizations in context.Footnote 2 In section 2 we first review some of the literature in which questions of aspectual and quantificational interpretation of conversion and -ing nominalizations has figured; this will set the stage for the main research questions that we intend to tackle in what follows. In section 3, we set out the quantificational and aspectual categories we propose to look at and the terminology we use to designate them. Section 4 describes the methodology by which we extracted, cleaned and coded data from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) and the British National Corpus (BNC). We present our findings in sections 5 and 6. Section 5 looks at the quantificational properties of referential nominalizations. Section 6 looks at quantificational and aspectual properties of eventive nominalizations. Section 7 offers a brief assessment of the theoretical implications of our findings.

Our conclusion will be that the quantificational properties and aspectual interpretation of both conversion and -ing nominalizations are not rigidly or even loosely determined by the form of the nominalization, nor by the aspectual properties of the base verb. Of those two factors, the interpretation of the base verb plays a stronger role in quantificational and aspectual readings. But we will argue that an even stronger role is played by factors arising from the context in which conversion forms and -ing nominalizations are deployed. For example, we find that quantificational properties of conversion and -ing forms are not rigidly fixed, but rather are signaled in context, with many conversion and -ing nominalizations exhibiting both count and mass interpretations. We find as well that sometimes differences in quantification give rise in turn to differences in aspectual interpretation. The aspectual interpretation of conversion and -ing nominalizations can also be influenced by the presence of temporal and quantificational modifiers, by surrounding tenses, as well as by encyclopedic knowledge.

2 Theoretical background and claims in the literature

Although there has certainly been research in the past on the aspectual and quantificational interpretation of nominalizations in English and other languages, this has not been a particularly active area of research, nor one that has been explored in a particularly systematic way. Earlier literature comments on relationships between eventive versus referential interpretation and count versus mass quantification, or between aktionsart and quantification, and occasionally on form of nominalization (different affixes, conversion) and aspect or quantification. To the extent that a coherent picture has emerged, it is that most researchers believe that conversion and -ing have different semantic properties, roughly that conversion has a perfectivizing or packaging function and tends towards count quantification and referential readings while -ing tends towards an imperfectivizing function, favoring mass quantification and eventive interpretations. In contrast, we will show in what follows that conversion and -ing are not distinguished in these ways, and that they behave quite similarly in terms of aspectual and quantificational readings. Indeed, what will emerge most clearly from our study is that conversion and -ing are both subject to substantial coercion in context that makes them amenable to a wide range of eventive and referential readings, mass and count quantification, and bounded and unbounded aspectual interpretations.

One of the first studies we can find of aspectual interpretation in English nominalization, specifically between conversion and -ing forms, is Biese (Reference Biese1941). Biese suggests that there is ‘a very clearly marked difference in meaning between the two types of formation’ (Reference Biese1941: 311), -ing nouns denoting on-going action or habits and exhibiting mass quantification, conversion noun expressing a ‘definite beginning and end’ and being associated with count quantification. Some three decades later, Mourelatos (Reference Mourelatos1978) remarks on a possible connection between the aktionsart of the base verb, the form of nominalization (-ing versus conversion) and the quantificational interpretation of the nominalization, suggesting that state and activity verbs yield mass-quantified nominalizations, whereas accomplishments and achievements yield count-quantified ones (see also Filip Reference Filip and Binnick2012: 736). Brinton (Reference Brinton, Bertinetto, Bianchi, Higginbotham and Squartini1995, Reference Brinton1998) considers in much more detail the way in which the aktionsart of the verbal base might affect the overall quantificational and aspectual interpretation of the nominalization (Reference Brinton, Bertinetto, Bianchi, Higginbotham and Squartini1995: 39):Footnote 3

In English, both Latinate derivational suffixes and the native zero affix serve to perfectivize or package the aktionsart of the verb, much as the simple tense does in the verbal domain, with events presented as bounded wholes, activities treated as either indeterminately or determinately bound, and states remaining inherently unbound. The gerund serves to imperfectivize or grind the aktionsart of the verb, much as the progressive does in the verbal domain, resulting in unbounded situations. The mass or count quality of the deverbal noun depends, then, not just upon the aktionsart of the base verb, but also upon the aspect features of the deverbalizing device, the zero affix producing count nouns except in the case of states, the gerund always producing mass nouns,…

According to Brinton (Reference Brinton, Bertinetto, Bianchi, Higginbotham and Squartini1995), -ing has a preference for bases that denote activities. When -ing attaches to accomplishments or achievements it highlights the process leading up to the implied endpoint. Although the aktionsart of the base verb has some effect on bounded/unbounded readings for Brinton, she nevertheless maintains that there is a rough correlation between the means of nominalization (-ing, conversion, ATK affixes) and the aspectual and quantificational reading of the nominal.Footnote 4 In a subsequent paper, Brinton (Reference Brinton1998: 49) makes a stronger claim, namely that conversion ‘is a means of converting the situation into an event (an accomplishment, achievement, or semelfactive) by adding the feature of telicity; this is a shift from mass to count.’ That is, conversion does not package an event, but rather supplies an implied endpoint or telos. Boundedness is in principle independent of telicity (Reference Brinton1998: 59).

Further comments on the aspectual and quantificational characteristics of nominalizations can be found in several reference works. Grimshaw (Reference Grimshaw, Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011: 1304) notes that -ing nominalizations can be telic, at least for change of state verbs and suggests further that state verbs lack -ing nominalizations entirely (Reference Declerck2011: 1310). Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: 214) suggest that conversion nominalizations that express instantaneous aspect always have count quantification, and typically do not also allow non-count readings (a chant/two burps, but *some chant/some burp). A non-count reading is frequently preferred for the corresponding -ing nominalization (some chanting/some burping).

Researchers within cognitive/functional frameworks have touched on several of the themes we will explore in our study. Langacker (Reference Langacker1991), for example, associates -ing nominals with mass quantification. Park & Park (Reference Park and Park2017) recognize that conversion and -ing nominals can have both referential and eventive interpretations, their observations on aspect generally being in line with the other studies we review here: -ing nominals are generally imperfective/unbounded and mass-quantified, although Park & Park do note that with the addition of an appropriate determiner (what they call ‘grounding’), count-quantification is made possible (Reference Park and Park2017: 727). Maekelberghe (Reference Maekelberghe2017) and Heyvaert, Maekelberghe & Buyle (Reference Heyvaert, Maekelberghe and Buyle2018) compare what they call nominal gerunds (our -ing nouns) to verbal gerunds (phrases like her eating the apple). Among other things, their quantitative studies show that nominal gerunds are frequently either neutral or ambiguous with respect to boundedness, but that when they express that distinction, they can express either a bounded or unbounded reading.Footnote 5, Footnote 6

Aspectual and quantificational aspects of nominalizations have not been the subject of extensive attention within generative literature, but they do receive passing mention in several works. Grimshaw's (Reference Grimshaw1990) seminal work on argument structure and event nominalization is only tangentially of interest to us here. Although she does not touch in any depth on issues of aspectual interpretation, Grimshaw does claim that -ing nominalizations are invariably complex events and that complex event nominalizations do not pluralize and cannot appear with an indefinite determiner (Reference Grimshaw1990: 54–6). The latter is a hallmark, of course, of mass quantification, so we might infer that for Grimshaw, -ing nominalizations should be mass-quantified.

Working within a Distributed Morphology framework, Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2001: 51) deals more directly with issues of aspect in nominalization. She briefly considers the relationship between form of nominalization and potential readings, observing that -ing nominalizations tend to be interpreted as imperfective and are less felicitous with accomplishments and achievements (telic eventsFootnote 7) than with activities. Borer (Reference Borer2013: 162) argues that eventive -ing is a functional element which produces atelic (in her terms ‘homogenous’) nominalizations. Iordachioaia & Soare (Reference Iordăchioaia, Soare, Bonami and Cabredo-Hofherr2008) are primarily concerned with nominalization patterns in Romanian, but their argument is nevertheless relevant here as they raise the possibility that particular types of nominalization might correlate with telicity. In Romanian, the infinitive selects for bounded events and does not change boundedness, whereas the supine takes any sort of base and gives rise to an unbounded interpretation. The infinitive behaves like a count noun, but the supine does not. Both Alexiadou (Reference Alexiadou2001) and Iordachioaia & Soare (Reference Iordăchioaia, Soare, Bonami and Cabredo-Hofherr2008) present syntactic analyses of nominalizations in which the effects of aspect on nominalization are attributed to the presence of functional projections like AspP internal to the DP.

What emerges from this brief review of the literature is that the aspectual and quantificational behavior of -ing and conversion nouns have not been studied in a comprehensive, thorough way. We suspect that there is a great deal more to be said on this subject: although we might expect there to be some relationship between the means of nominalization (conversion vs -ing), the quantificational characteristics (count vs mass) of the noun, the aktionsarts of the base (state, activity, accomplishment, achievement) and the aspectual reading of the nominalization (bounded, unbounded, telic, atelic, etc.), we have yet to untangle this complex web of potential relationships. What has been lacking in the literature is a systematic descriptive study of the expression of aspect and quantity in various types of nominals, looking at nominalizations as they occur in context. What we will try to show in what follows is that the picture that emerges from a careful corpus analysis is both simpler and more complex than the studies reviewed above have suggested. It is simpler in that conversion and -ing turn out not to be so different in their aspectual and quantificational properties after all. It is far more complex, however, in that the ultimate readings of conversion and -ing nominalizations appear to result from a complex interplay of the semantics of their bases and coercion by a wide range of contextual factors.

3 Matters of definition

Up to now we have been using terms like ‘aktionsart’, ‘telicity/atelicity’, ‘bounded/unbounded’ and so on as if they were transparent in meaning, but this is far from the case. Different authors use the terms in slightly different ways, so we must be clear from the start how we will understand and use them. We begin with more straightforward and standardly used terms like ‘count’ versus ‘mass’ and ‘referential’ versus ‘eventive’. We then move to relatively well-understood (but nevertheless sometimes still controversial) terms for aktionsarts (state, activity, accomplishment, achievement, semelfactive) and their relationship to concepts like durativity, telicity and boundedness. We end, finally, with establishing what we mean by ‘aspect’ in nouns, where there has been far less clear discussion and in particular what we mean by ‘bounded’ and ‘unbounded’ when we refer to the readings of nominalizations.

Count nouns are nouns that can occur with the indefinite determiner and with numerals and quantifiers such as many. Mass nouns resist indefinite determiners, do not occur in the plural and prefer quantifiers such as much or some (Huddleston & Pullum Reference Huddleston and Pullum2002: section 3.1). It is also uncontroversial that although nouns like squirrel and water are typically conceptualized as count and mass respectively, count nouns can almost always be coerced into mass readings and mass nouns into count readings:

(3) (a) There was some squirrel in the Brunswick stew.

(b) Please pick up three waters and a coffee.

We will assume that simplex nouns often have a default quantification: squirrel is default count and water default mass, but can be coerced into the non-default quantification given the right context.Footnote 8

It has also been widely noted that nominalizations may have two different kinds of readings. One is the reading that is variously referred to as the ‘result’, ‘referential’ or ‘R’ reading. With this reading, the nominalization denotes the outcome or product of the event or a participant in the event (agent, patient, instrument, location, etc.). The ‘eventive’ or ‘E’ reading, in contrast, denotes the event or state itself. The two readings are illustrated in (4):Footnote 9

(4) (a) The examination was ten pages long. (referential)

(b) The examination of the patient took over an hour. (eventive)

We now turn to distinctions that pertain to the semantics of the verbal bases on which nominalizations are derived. Filip (Reference Filip and Binnick2012: 721) defines lexical aspect as ‘a semantic category that concerns properties of eventualities (in the sense of Bach Reference Bach and Cole1981) expressed by verbs’. These characteristics are ones that contribute to (but do not entirely determine) what Filip calls aspectual classes or aktionsarts, following the work of Vendler (Reference Vendler1957) and many others.Footnote 10 The literature on aktionsarts typically distinguishes four or sometimes five different kinds of situations (where ‘situation’ is a term that covers events and states),Footnote 11 typically states, activities, accomplishments, achievements and semelfactives.Footnote 12 Our understanding of aktionsarts largely follows that of such theorists as Smith (Reference Smith1991), Brinton (Reference Brinton, Bertinetto, Bianchi, Higginbotham and Squartini1995, Reference Brinton1998) and Filip (Reference Filip and Binnick2012) in considering each aktionsart as a composite of more primitive conceptual categories.

• States are distinguished from events (activities, accomplishments, achievements, semelfactives) by requiring no input of energy to persist (Comrie Reference Comrie1976: 49). They do not imply change or transition and they involve no endpoint, either temporal or instrinsic. Events all involve some input of energy.

• Activities are events that do not involve transition or change. They are durative rather than punctual, and they do not imply an intrinsic endpoint (that is, they are atelic).

• Accomplishments involve some transition or change, and like activities are temporally durative. Unlike activities, they imply an intrinsic endpoint (they are telic).

• Achievements also involve transition or change and imply an intrinsic endpoint, but they are temporally punctual.

• Semelfactives are punctual, like achievements, but do not imply a transition or change, nor do they imply an intrinsic endpoint.

(5) gives the lexical categorization of some verbs:

(5) (a) states: love, fear, know

(b) activities: dance, push, float

(c) accomplishments: cook, wash, cover

(d) achievements: arrive, explode, find

(e) semelfactives: flash, blink, cough

Since we will be discussing deverbal nominalizations of a wide range of verbs, we begin with the assumption that just as nouns may have a default quantification, verbs may have a default lexical aspect, in other words the lexical semantic contribution of the verb to phrasal or sentential aspect. We must be clear that these are default classifications of the lexical aspect of verbs. It is well known that various features of context – presence or absence of temporal modifiers, prepositional phrases, the quantification of objects or subjects – can change the aspectual interpretation of the verb (or verb phrase, or sentence). For example, although the default lexical aspect of push is an activity, with the addition of a prepositional phrase expressing a goal, a sentence in which it occurs can be construed as an accomplishment, as in (6) (Verkuyl Reference Verkuyl1972):

(6) We pushed the car into the garage.

We will assume that the lexical semantics of verbs may supply facets of meaning that contribute to aktionsarts and will distinguish in what follows between lexical aktionsarts and contextually induced aktionsarts.Footnote 13

We now turn to the rather vexed notion of ‘boundedness’. Several works in the literature on nominalization and aspect make use of the terms ‘bound(ed)’ and ‘unbound(ed)’. The literature suggests that some insight is to be gained by applying the term cross-categorially to both nouns and verbs. Looking first at the nominal domain, count nouns are often described as being intrinsically bounded and mass nouns as unbounded (Talmy Reference Talmy and Rudzka-Ostyn1988; Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1991; Brinton Reference Brinton, Bertinetto, Bianchi, Higginbotham and Squartini1995, among others). When a mass noun is coerced to a count noun, the process is sometimes known in the literature as bounding, or alternatively ‘packaging’ (Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1991; Brinton Reference Brinton, Bertinetto, Bianchi, Higginbotham and Squartini1995). Talmy (Reference Talmy and Rudzka-Ostyn1988: 179) uses the term ‘portion-excerpting’. Coercion in the opposite direction – from count to mass – is sometimes known as ‘debounding’ or more frequently as ‘grinding’.

The terms bounded and unbounded are also used in the verbal domain, with boundedness sometimes equated with perfectivity or completed events and unboundedness with events that lack an arbitrary temporal endpoint, for example, progressives or continuative events (Brinton Reference Brinton, Bertinetto, Bianchi, Higginbotham and Squartini1995: 32, citing Paprotte Reference Paprotte and Rudzka-Ostyn1988: 459; Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1991: 19). But elsewhere the term ‘bounded’ has been used in the verbal domain as equivalent to telic (Declerck Reference Declerck1979; Smith Reference Smith1991: 26; Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1991: 20). In other words, boundedness and telicity are sometimes linked and even entirely conflated.

We believe that equating or conflating telicity and boundedness is a mistake. Here we follow Depraetere (Reference Depraetere1995), who points out that telic events are not inevitably temporally bounded, and suggests that, ‘A sentence is bounded if it represents a situation as having reached a temporal boundary, irrespective of whether the situation has an intended or inherent endpoint or not. It is unbounded if it does not represent a situation as having reached a temporal boundary’ (Reference Depraetere1995: 3). Depraetere offers the examples in (7) to show that an atelic predicate can be bounded if an arbitrary temporal endpoint is designated, as in (7a), or a telic predicate can be unbounded if an endpoint is implied, but not reached), as in (7b):

(7) (a) Judith played in the garden for an hour.

(b) John was opening the parcel.

The important point for our purposes is that an intrinsic endpoint and a temporal endpoint may coincide, but a lexically implied intrinsic endpoint does not inevitably necessitate an actual temporal endpoint. Endpoints may be implied, even if they are not reached.Footnote 14

We now come to the thorniest point in our consideration of terminology, how the terms ‘bounded’ and ‘unbounded’ should be deployed in discussing the aspectual characteristics of deverbal nominalizations. If we concentrate only on the status of a noun as count versus mass, deverbal nominalizations might simply be considered bounded when they show count-quantification and unbounded when they show mass-quantification. On the other hand, because they have verbal bases, we might expect that nominalizations might also imply the presence or absence of temporal endpoints, that is, bounding in the verbal sense. And of course the lexical aspect of their verbal bases might contribute an implied intrinsic endpoint, complicating matters still further. How do we tease apart nominal boundedness from verbal boundedness, temporal endpoints from intrinsic endpoints, and so on? To our knowledge, none of the literature we have cited in section 2 has taken on this terminological and conceptual tangle.

Theoretically we might have no problem here, if it were the case that bounding in the nominal domain always correlated with bounding in the verbal domain, with count nominalizations always expressing temporal boundedness and mass nominalizations always expressing temporal unboundedness. But this is not what we find. Consider the examples in (8). All contain eventive -ing nominalizations based on verbs that are accomplishments or achievements:

(8) (a) American Artist 1999: ‘My backgrounds often consist of reds, blues, and yellows, so too much BLENDING can create a muddy appearance,’ the artist concedes. (mass/temporally unbounded)

(b) American Artist 1991: He managed this through a carefully muted gradation of tones and a BLENDING of outline edges, accomplished through dry-brush work. (count/temporally bounded)

(c) American Artist 2006: With oils a further BLENDING can be accomplished with a soft sable brush; with pastels a stump, a flesh-colored pastel pencil, or your finger can be used. (count/temporally unbounded)

(d) Science News 2006: The smooth patches indicate that the south-polar area has undergone recent FRACTURING or upheavals. (mass/temporally bounded)

In (8a), we observe mass quantification (too much blending). In terms of temporal construal, we understand blending to refer to an event the temporal bounds of which are not implied or not important, in other words unbounded in the verbal sense – the emphasis is on the process of mixing colors, not the resulting color. Although the verbal base of the -ing form is telic, both the quantification and the temporal aspect match in terms of being unbounded, which is what we would expect if bounding in the nominal domain and bounding in the verbal domain were linked. In (8b), we again have a match between bounding in the nominal domain (the -ing form is count) and bounding in the verbal domain (the blending event is completed, as suggested by the past tense verb accomplished in the following clause), again as we would expect if bounding in the nominal domain and bounding in the verbal domain were linked. But such linking seems not to be inevitable. In (8c), the quantification is count (bounded in the nominal domain), but no temporal endpoint is implied; here, even though blending is the subject of accomplish, the modal can suggests potentiality rather than completion. The aspectual interpretation is therefore unbounded and does not match the quantification. Finally, in (8d) we again have a mismatch: in the nominal domain we have mass quantification, but in the verbal domain we have clear temporal boundaries. The fracturing has ended, as the present perfect form of the preceding verb (has undergone) suggests.

What such examples point to, for us, is the conclusion that analogies that have been drawn between bounding in the nominal domain and bounding in the verbal domain run into difficulties precisely in the case of deverbal nominalizations. Since our goal in what follows is to understand the factors that contribute to the quantificational and aspectual construal of nominalizations rather than to develop a theory of links between quantification and aspect per se, we will settle here for using a set of descriptive terms for various readings: count versus mass, which we will use in the conventional sense, and bounded versus unbounded, by which we mean having or lacking linguistically relevant temporal boundaries. We will return in section 6 to the question of what we mean by boundedness in nominalizations and whether temporal bounding in the construal of nominalizations is actually a unitary concept.

4 Methodology

Our dataset comprises a total of over 57,700 instances of nominalizations in context, which were extracted from COCA and BNC. Most of the nominalizations appear in both singular and plural (e.g. blend, blends, blending, blendings). The conversion forms and -ing nominalizations in our dataset are based on 106 verbs, which are given in table 1. We chose 98 verbs from the 1,000 most frequent verbs listed in the COCA frequency list that exhibited both verb-to-noun conversion and -ing nominalizations; equal numbers of verbs were chosen from all frequency ranges. These were supplemented with 8 low frequency verbs which are not represented in the COCA frequency list. We then checked the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) to make sure that in each noun–verb conversion pair, the verb was attested earlier than the noun rather than the other way around.

Table 1. Verbs by class

For each verb, we extracted from COCA up to 300 tokens each of singular and plural conversion forms and singular and plural -ing nominalizations. Where there were fewer than 300 tokens in COCA, we supplemented with tokens from BNC up to 300. In some cases, even with the addition of examples from BNC, we did not reach 300 tokens, so from the start we did not always have equal numbers of tokens for each verb. The original data we extracted from COCA and BNC comprised well over 60,000 examples.Footnote 15

We then applied standard cleaning procedures and eliminated examples that were proper nouns, typos or misspellings, or words in a foreign language. We also eliminated examples that exhibited such a high degree of lexicalization that the nominalization was rendered not useful for our study (e.g. cast meaning ‘actors’, change meaning ‘coins’). The inevitable result of the cleaning procedure was that we were left with unequal numbers of tokens for each nominalization type, some types having large numbers of tokens that had to be eliminated and other types having a larger number of useable examples. The result was a database of approximately 57,700 items which we felt would be sufficient to turn up the sort of readings we were looking for.

Two further points should be noted about our database. First, large though it was, it was not designed with the idea of doing statistical analysis in mind, since we did not seek to have equal numbers of tokens for each kind of nominalization (conversion vs -ing, singular vs plural), or equal numbers of verbs for each aspectual class, and so on. This was not a problem for our goals, as we were looking for what kinds of readings conversion and -ing nominalizations could express rather than how often they expressed those readings, but it does preclude us from doing the sort of statistical analysis that some readers might desire. In what follows, we will concentrate on qualitative semantic analysis rather than quantitative analysis, and leave quantitative research to further study.

Second, to find the sorts of readings we were looking for, we needed to hand-code the data in several categories, as explained below. This involved reading and annotating each example individually, a lengthy and time-consuming process. Some of the readings we were looking for are subtle and infrequent, and no procedure of spot-checking or machine coding could possibly have suited our aims. Coding was based on the judgments of the two authors. The examples we cite in what follows are ones where the authors agree that the reading in question is plausible, although other readers might find alternative readings possible as well. Ideally in a study of this sort, one might wish for a larger number of coders as well as a check of inter-rater reliability. However, since our goal again was to establish the possibility of a range of readings for conversion and -ing nominalizations rather than to quantify how often they occur, we did not aim for this stricter standard.

We coded our data as follows. First, we classified our 106 verbs according to the standard aktionsarts (Vendler Reference Vendler1957; Smith Reference Smith1991; Filip Reference Filip and Binnick2012): states, activities, accomplishments, achievements and semelfactives, as seen in table 1. Twenty-one of our verbal bases belonged to more than one class, usually because they exhibit multiple senses (for example, cast as used in fishing or in sculpting). We also classified our conversion forms and -ing nominalizations into those with a referential reading and those with an eventive reading. For those nominalizations with eventive readings, we also coded for boundedness.Footnote 16 Instances with bounded readings were also coded for completive reading or package reading, a distinction that we will elucidate in section 6.2.Footnote 17 Finally, we coded our data with respect to the mass/count distinction. For example, hires in (9a) is referential and count, whereas hires in (9b) is eventive, bounded/package and count.

(9) Referential versus eventive

(a) Atlanta Journal Constitution 2012: Two recent HIRES are introduced. One presents a slide show about a fortune-cookie-making machine he designed, cracking wise throughout. Another acts out a comedy sketch about a fictional crazed caller (Referential, Quantification: count)

(b) Associated Press 2012: The Washington Post this past week compiled a list of military contractors, hospitals and universities that are delaying HIRES and bracing for cuts (Eventive, Boundedness: bounded/package, Quantification: count)

In (9a) hires designates the people hired, rather than the act of hiring. (9b), on the other hand, focuses on instances of the act of hiring, that is, our ‘bounded-package’ reading. Both examples have the conversion nominalization in the plural, and are therefore count-quantified.

5 Findings: referential interpretations

5.1 Referentiality

Contrary to what is sometimes claimed in the literature (e.g. Grimshaw Reference Grimshaw1990), both conversion forms and -ing(s) nominalizations appear with referential readings. In particular, conversion forms lend themselves readily to referential interpretations. Only eight conversion forms derived from the 106 verbs in our dataset did not exhibit referential readings, either in the singular or plural: blink, embrace, flash, kiss, lack, shove, stir and swim. What might emerge as somewhat more surprising, however, at least 33 of our verbs in our dataset have -ing nominalizations with clear referential readings in either the singular, the plural, or both (10):

(10) -ing forms with referential readings: accountings, assisting, bending, blending(s), casting(s), catching, climbing, covering(s), cutting(s), dancing(s), dividing, drawing(s), drippings, finding(s), finishing(s), fixings, heating, holding(s), kicking, meltings, mixings, offering(s), returning, rising(s), sailing, spinning(s), stepping, surrounding(s), takings, tastings, washing(s), winnings, worryings

(11) gives examples of conversion forms with referential readings, and (12) presents referential -ing nominalizations.

(11) Referential conversion nominalizations by aktionsart

(a) State hope ‘the thing that one hopes’

Atlantic Monthly 1999: The history of African-Americans since the discovery of the New World is the story of their encounter with technology, an encounter that has proved perhaps irremediably devastating to their HOPES, dreams, and possibilities.

(b) Activity climb ‘the place one climbs’

Backpacker 1994: We do this all the way to the base of the CLIMB. This process, the verbal evaluation of potential pitfalls and the subsequent analysis of appropriate responses, is standard operating procedure for mountaineers.

(c) Accomplishment display ‘the stuff that's displayed’

Astronomy 1998: My favorite DISPLAY, though, was a collection of Lowell's original sketches of Mars.

(d) Achievement find ‘the thing one has found’

Astronomy 2006: True to Haag's nature, he outdid even these collecting accomplishments. His greatest FIND was not made in the field but given to him wrapped in a brown card-board box.

(e) Semelfactive drip ‘a small drip-like quantity’

Ploughshares 2005: ‘That's just wrong,’ Bob said, stepping away and sipping a sad little DRIP of tequila.

(12) Referential -ing nominalizations by aktionsart

(a) Activity accounting ‘a document about accounts’

The Antioch Review 2001: You never saw statements concerning your inheritance, did you? Never received annual ACCOUNTINGS?

(b) Accomplishment bending ‘the place that has a bend’

Technology Review 2002: This prototype has flexible, hinged blades; in strong winds, they bend back slightly while spinning. The BENDING is barely perceptible to a casual observer, but it's a radical departure from how existing wind turbines work-and it just may change the fate of wind power.

(c) Achievement finding ‘thing one has found’

Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness 2006: A second interesting FINDING is the apparent confusion over the causes of these infectious diseases and the struggle within the medical community to find treatments for them.

(d) Semelfactive dripping ‘substance that has dripped’

Science News 2006: At the older camp, the group found that manganese, phosphorus, and strontium concentrations in soil were an order of magnitude higher under the drying racks than in soils outside the camp. DRIPPINGS from the fish probably caused the difference.

The examples in (11) and (12) show clearly that there is no strict correlation between type of nominalization (i.e. conversion, -ing) and a referential reading. It follows that we should expect to find doublets where the conversion form and the corresponding -ing form might have precisely the same referential reading. And we do indeed find such doublets, as the examples in (13) illustrate:Footnote 18

(13) Minimal pairs of conversion and -ing nominals with referential readings

(a) cut/cuttings

San Francisco Chronicle 1992: Thirteen of the train's estimated 100 passengers suffered minor injuries, including CUTS, bruises and back strain.

Ebony 2000: in the Bible's book of Leviticus 19:28, God tells Moses: ‘Ye shall not make any CUTTINGS in your flesh for the dead, nor print any marks upon you.’

(b) finish/finishing

USA Today 2015: The Ared 5000 stretch fabric is waterproof (absolutely guaranteed to keep the wet out) and water repellent (the fabric FINISH is such that it won' t retain moisture and water simply rolls off the jacket);

Forbes 1990: Final FINISHING on the gun is called ‘French grey’.

(c) melt/melting

Chicago Sun-Times 2006: Three to a serving (about the size of a golf ball), the arancini sported a mellow MELT of mozzarella under a crusty golden shell.

The Kenyon Review 2006: She snapped off her glasses and drained the MELTINGS of her Bloody Mary and placed the cup back in its bezel.

5.2 Referential -ing and quantification

One interesting finding that emerges clearly from our study is that it is especially common for -ing forms to be interpreted referentially when they occur in the plural, and in fact, several plural forms (surroundings, coverings, drippings, holdings, winnings and mixings) are always referential in our data. In some cases, the referential -ing forms show the same meaning in both the singular and the plural forms, as the examples in (14) show:

(14)

(a) covering/coverings

Military History 2005: Finally he would add a waterproof COVERING of thin leather, bark or snakeskin.

Saturday Evening Post 1993: You want bulbs without deep scars, but small nicks and loose paperlike COVERINGS (tunics) are acceptable.

(b) casting/castings

Inc. 1995: We used to fall behind schedule because our planning failed to account for the resting time a CASTING requires between steps.

Black Enterprise 1990: While the Flint, Mich., operations continue to produce painted and metal parts for the Big Three auto manufacturers, the New Haven plant will manufacture cylinder heads, exhaust manifolds and grey iron CASTINGS for Chrysler Corp. and General Motors' Diesel-Allison Division.

In (14a), for instance, coverings is the plural form of covering with the meaning ‘a layer that covers something’. In a similar vein, cutting in (15a) and cuttings in (15b) have the same meaning, i.e. something that has been cut off (e.g. a part of a plant). In (15c), however, the plural cuttings appears with the reading ‘an injury made when the skin is cut with something sharp’. This reading is similar to the conversion form cuts and does not appear with the singular cutting.

(15) cutting/cuttings

(a) Horticulture 1992: Firm the moss around the CUTTING to protect it until it roots.

(b) Harpers Magazine 1993: His wife walked in from outside, carrying some CUTTINGS.

(c) Ebony 2000: ‘Ye shall not make any CUTTINGS in your flesh for the dead, nor print any marks upon you.’

We also find, however, that there are plural -ing forms that are quite distinct in meaning from the corresponding singular -ing forms. Consider the examples in (16):

(16) Sunset 2009: Meanwhile, make gravy: Pour DRIPPINGS into a clear measuring cup, using a fat spatula to scrape off browned bits stuck to pan.

Backpacker 2004: Assemble a Dagwood-style tortilla wrap with FIXINGS like cheese, salami, hummus, and fresh bell peppers.

The Kenyon Review 2006: She snapped off her glasses and drained the MELTINGS of her Bloody Mary and placed the cup back in its bezel.

The Virginia Quarterly Review 2005: I kettled water and thrashed about for some MIXINGS.

Associated Press 2002: They'd rob a few people, have a few laughs, spend their TAKINGS on booze and drugs.

Forbes 2003: Thanks to boom-time WINNINGS, they have the money to seed a new crop of startups, helping Silicon Valley – which might better be dubbed ‘the Bust Belt’

The examples in (16) suggest that not all plural -ing nominalizations are based on the singular -ing form. That is, there is no singular dripping that corresponds to the sense of drippings in (16), nor are there examples of taking or winning with the meaning ‘things/stuff which are won or taken’. Similarly for fixings and meltings, both of which lack singular counterparts with the same referential meaning. What this suggests to us is that -ings might be in the process of becoming a nominalizing affix in its own right with a collective flavor: examples like winnings, takings, meltings and drippings always have a collective reading and denote the internal argument of the verb.Footnote 19

We now turn to the question of whether referential conversion and referential -ing nominalizations show any correlations in terms of count or mass-quantification. Our data show clearly that no such correlations exist. Thus, it is not necessarily the case that there is a correlation between referential -ing nominalizations and mass interpretation, on the one hand, and referential conversion nouns and count interpretation on the other hand (cf. Brinton Reference Brinton, Bertinetto, Bianchi, Higginbotham and Squartini1995). This of course does not mean that any -ing nominalization or conversion form can receive either a count or a mass interpretation. For example, in our data beat is always count and hurt is always mass-quantified. In more detail, conversion nouns often receive mass interpretations: 50 of 106 verbs are found with mass quantification. The vast majority of -ing nominals (90 of 106) can receive count interpretations. Twelve of those 90 -ing nominals only occur with count interpretations (accounting, beating, bursting, covering, displaying, embracing, finding, offering, revealing, staying, surrounding, transferring). Examples of conversion forms and -ing nominalizations with count and mass interpretations are given in (17):

(17)

(a) State Conversion count

Arts Education Policy Review 1997: I have no DOUBTS, therefore, that the aesthetic education program produced by LCI over the years must have a beneficial effect on the students who are exposed to it. Conversion mass

Backpacker 1995: There is some CONCERN, however, about women on birth control pills and altitude. -ing count

Review of Contemporary Fiction 2009: And as for small difficulties and WORRYINGS, prospects of sudden disaster, peril of life and limb; all these, and death itself, seem to him only sly, good-natured hits, and jolly punches in the side bestowed by the unseen and unaccountable old joker.

(b) Activity Conversion count

Backpacker 1996: The intake hose is long, which makes it versatile, and an adjustable FLOAT keeps the intake from resting on the mucky bottom of a creek or river. Conversion mass

Skiing 1995: Exaggerating the upward motion of a pole plant helps to unweight the skis and allows for a bit of FLOAT in the end of the turn (an old powder ploy), and keeping your hands up will also help protect your face from unfriendly branches or angry squirrels. -ing count

The World & I 1998: Her hair had tinges of a lighter rust color, little SPINNINGS of paint along her neck. -ing-mass

Mother Jones 2010: While stallions sent to long-term HOLDING are gelded, their wild brethren continue to reproduce.

(c) Accomplishment Conversion count

Atlantic Monthly 1998: Intellectual property is knowledge or expression that is owned by someone. It has three customary domains: copyright, patent, and trademark (a fourth FORM, trade secrets, is sometimes included). Conversion mass

American Craft 1999: As a child of artists and an art student from age ii, he had no non-art CHAT, so he consciously began accumulating entertaining stories. -ing count

The ravening 2008: He recognized it now-herbal and clean, a BLENDING of rosemary and lavender-all manner of herbs-a fragrance of the wild-of the wood-of the earth, mysterious and evocative. -ing mass

American Artist 1992: As far as warping or BENDING goes, Masonite typically curves, especially in the larger sizes.

(d) Achievement Conversion count

NYTimes 2015: Gate to the Forbidden City for being the only foreigner to compete -- notwithstanding a FINISH that placed me somewhere around 1,120th, an hour or more behind the winners. Conversion mass

Mother Jones 1997: But indeed there stood my mother with four German tourists, large and blond and gleaming in their sweat-streaked khakis, expensive cameras and voluptuous leather travel bags draped around them like fresh KILL. -ing count

Magazine Antiques 1998: His decorative FINISHINGS had been incorporated into McKim, Mead and White buildings routinely for the past decade. -ing mass

Technology Teacher 2009: The main components of a prosthesis for the lower limb are: socket, liner (interface between the skin and the socket), knee (in prostheses for tight amputation), adapters, feet, and cosmetic FINISHING (Reykjavik, 2005).

(e) Semelfactive Conversion count

Fantasy & Science Fiction 2010: Harris had you by eleven seconds. If you'd kept close, you would have toasted him at the end. The kid thinks he has a KICK, but he doesn't. Conversion mass

Prevention 2000: Dieting can contribute to bad breath, as can postnasal DRIP. -ing count

Mother Earth News 2011: In a large skillet over medium heat, heat an additional quarter cup of bacon DRIPPINGS or vegetable oil, then add the drained beans, a couple of spoonfuls at a time. -ing mass

Physical Educator 1996: With the softball example, locomotor skills such as skipping and hopping and manipulative skills such as punting and KICKING do not have to be taught since these skills are not related to the goal of playing softball.

Referential readings are rather rare for stative verbs, and we found no clear examples of referential mass-quantified -ing nominalizations based on state verbs.

6 Findings: eventive interpretations

Just as we find referential interpretations with both conversion and -ing nominalizations, we find eventive intepretations with both means of nominalization, counter to what Grimshaw (Reference Grimshaw1990), for example, claims. The -ing nominalizations typically allow an eventive reading, but what might be seen as more surprising, considering claims in the literature (e.g. Grimshaw Reference Grimshaw1990), is that conversion nouns are frequently eventive in interpretation as well. Of our 106 verbs, we find only a handful that never seem to express eventive readings in their conversion nouns, either in the singular or plural, namely, cover, form, heat, mix and stink. Some conversion nouns express eventivity only in the singular; for example, psych-states like doubt, fear, hate, hope, worry tend to work this way. We illustrate with a representative selection of verbs:

(18) Eventive conversion nominalizations by aktionsart

(a) State (hate)

Newsweek 1991: What he got instead was HATE, based simply on the color of his skin.

(b) Activity (float)

Field and Stream 2007: A good three-day, two-night FLOAT with camping, plenty of smallies, and a few whitewater challenges runs about 35 miles from a speck on the map called Twickenham to another tiny spot called Clarno.

(c) Accomplishment (repair)

Science News 1993: Each walk is supposed to last six hours, but the teams may stay out an hour or two longer if they find themselves in the middle of a critical REPAIR, Hoffman notes.

(d) Achievement (kill)

Esquire 2003: He's calm, almost stoic in the KILL.

(e) Semelfactive (knock)

Child Life 1999: Just then there was a KNOCK at the door, and a voice in the darkness called, ‘Open in the name of His Excellency, George Washington!’

(19) Eventive -ing nominalizations by aktionsart

(a) State (hate)

Newsweek 1991: His HATING began early in life.

(b) Activity (float)

Understanding Children 1992: (BNC): Further evidence of young children's tendency to psychologize comes from a series of studies in which Piaget (1929, 1930) interviewed children about the causes of various phenomena, such as dreams, the origin of the sun and the moon, the weather, the nature of air, the movement of the clouds, the FLOATING of boats, and the workings of a steam-engine.

(c) Accomplishment (repair)

American Spectator 2006: Religion will be effectively expelled from one of the areas where it is most needed, which is the REPAIRING of damaged human relations.

(d) Achievement (kill)

Mother Jones 2005: Pollard soon discovered that he had either been out of the state or in jail at the time of the KILLING, and found a taped statement from one of the witnesses confessing that she had made up her story.

(e) Semelfactive (knock)

Harpers Magazine 1999: A loud KNOCKING on the door interrupts Grandioso's elegiac monologue.

It is clear, then, that there is no consistent correlation of conversion with referentiality and -ing nominalization with eventivity.

6.1 Eventivity and quantification

We have also failed to find any consistent correlation between quantification and type of eventive nominalization (that is, conversion versus -ing). As we saw in section 2, there have been sporadic claims in the literature that conversion nouns tend to be count-quantified and -ing nominalizations mass-quantified (Mourelatos Reference Mourelatos1978; Brinton Reference Brinton, Bertinetto, Bianchi, Higginbotham and Squartini1995).Footnote 20 Although there may be a weak tendency in this direction in the sense that some conversion nominals only occasionally yield mass readings and some -ing nominals only occasionally yield count readings, it nevertheless seems more the norm than the exception for conversion nominalizations and -ing nominalizations to be found with either count quantification or mass quantification. Indeed, of the 106 verbs that we examined, there are only 10 whose singular conversion and -ing nominalizations consistently exhibit the correlation claimed in the literature (count ~ conversion//mass ~ -ing nominalization): chop, dance, drink, fix, hit, pass, poke, run, slam and swim. This number drops to four if we look as well at plural nominalizations (chop, dance, drink and swim), as the ability to occur in the plural automatically signals count-quantification. Again, we provide some representative examples, arranged by lexical aktionsart:

(20)

(a) State: hate Conversion count

Smithsonian 1992: He trusts no one but himself; never concedes -no matter how far behind he may be and hates his opponents with an all-enduring HATE. Conversion mass

Bicycling 2003: They're ruthless, full of HATE, and they'll do anything they can to keep us off the mountain. -ing count

BNC Fiction 1991: A sudden hatred came over her; a cold, bitter HATING of everything that lived and breathed. -ing mass

Showbiz Tonight 2011: Now, Wendy, this isn't goofing around hating. This is real HATING. Where is it coming from?

(b) Activity: push Conversion count

Atlantic Monthly 1993: For it to do so required a plan, a PUSH, an exercise of central power.

Conversion mass

Sporting News 2006: Though Cofield hasn't generated a lot of PUSH, his play has gotten increasingly stronger on the line and he isn't often moved backward.

-ing count

Essence 1993: There were no fists, no slaps, just a continual PUSHING, he of her, against the wall as if to pin her there and capture or extinguish the source of her resistance, and her continued pushing against him…

-ing mass

Analog Science Fiction & Fact 2010: There's been some PUSHING of our limits, but nothing serious.

(c) Accomplishment: change Conversion count

Health & Social Work 2006: A significant CHANGE in the new regulations is that all disclosures for the purpose of general marketing require prior authorization. Conversion mass

Education 2006: As part of the processes of language change, sometimes the original meanings of native words and other borrowed lexical items may undergo semantic CHANGE; some words may lose their original meanings, become obsolete, archaic, rare, or even just disappear. -ing count

Atlanta Journal Constitution 1991: Maybe there will be a historical CHANGING of sports teams' names in 1991. -ing mass

Journal of Information Systems 1992: Whereas traditional rule-based systems require constant CHANGING of the rules to adapt to new situations, a system that reasons from first principles can apply the underlying causal model to the new situations to arrive at solutions.

(d) Achievement: fracture Conversion count

Orthopaedic Nursing 2002: In the case of a FRACTURE, the periosteum is injured upon impact. Conversion mass

Christian Century 1996: These church parties lent the church local forms and regional identities which produced chronic national tensions, and some splinter movements, but no wholesale FRACTURE. -ing count

Essence 1992: ‘A violation of the father-daughter relationship leads to a FRACTURING of the psyche for both people’, says Phillips. -ing mass

Natural History 1999: Lyell recognized that catastrophes usually leave their signature, for extensive outpourings of lava or widespread FRACTURING of strata by earthquakes resist erasure from the geological record.

(e) Semelfactive: flash Conversion count

Astronomy 1995: These observations imply that both ideas were right: Galileo apparently saw both the meteorlike FLASH of a comet fragment entering Jupiter's atmosphere and then the appearance of the fireball from the explosion. Conversion mass

Newsweek 1990: Assimilating bits of Scorsese, Spielberg and Sam Peckinpah's balletic gift for carnage, Joanou gives us more than stylistic FLASH. -ing count

Natural History 1990: The snout tapping is exaggerated and repeated frequently, producing a very conspicuous FLASHING of the male's bright flanks and underbelly. -ing mass

Paris Review 1997: ‘Look at the snug snug corners and the shiny, dapper sides!’ he sang, turning one in the sunlight so as to lose himself in an ecstasy of metallic FLASHING.

Of our 106 verbs, there are roughly 30 that exhibit full paradigms such as those illustrated above.

Is there anything more to be said about the quantification of conversion and -ing nominalizations? Clearly, individual conversion or -ing nominalizations may have preferences with respect to quantification. So pay is always mass, desire is frequently mass, but can be count, and chat favors count, but is sometimes mass. Similarly, beating is always count, blending can be either count or mass, and chatting is always mass. It is not clear at this point whether there is anything systematic about these quantification patterns, but what does emerge clearly is that quantification is not fixed for the form of nominalization (conversion or -ing) as a whole.

6.2 Aspect in conversion and -ing nominalizations

As we saw in section 2, to the extent that questions of aspectual interpretation in conversion and -ing nominalizations have been pursued in the literature, the claim has generally been that conversion nominalizations have a more bounded/package/instance/portion/perfective interpretation and -ing nominalizations an unbounded/ongoing/imperfective interpretation. In other words, the assumption in the literature has been that the type of nominalization predicts the aspectual reading. Our data suggest that this simple correlation, as with the quantificational correlations we explored above, does not obtain. Rather, what we find is a much more nuanced matter: it appears that both conversions and -ing nominals can be either unbounded or bounded, and indeed that bounded in the nominal sense has two distinct ‘flavors’ that we can discern, either of which can occur with conversion or -ing nominals.

Let us first make clear both what we mean by ‘flavors’ of boundedness and how we determined the boundedness of particular exemplars. At the end of section 3, we raised the question of what we mean by aspectuality in nominalizations and proposed that we would discuss nominal aspectuality in terms of boundedness, where we mean by bounded ‘implying a linguistically relevant temporal boundary’ and by unbounded ‘not implying a linguistically relevant temporal boundary’. We proposed, following Depraetare (Reference Depraetere1995), to disassociate temporal boundedness from telicity, so that an event could be both unbounded and telic or bounded and atelic. In classifying our data we deemed a reading to be bounded if it implied that a temporal endpoint had been reached. We further determined a reading to be bounded-completive if the focus was on the endpoint or right temporal boundary of the event – the point of culmination or completion. On the other hand, we counted a reading as bounded-package if the nominal was conceptualized as a whole from beginning to end with a clear temporal endpoint but without particular emphasis on that endpoint. Often such examples could be paraphrased as ‘an instance of V or V-ing’. Finally, we deemed it to be unbounded if the context surrounding the nominalization suggested an emphasis on the internal progress of the event rather than on the beginning or the end. Our decisions whether to count a particular nominal as expressing an unbounded, bounded-completive, or bounded-package reading were based largely on elements of context: the tenses of surrounding verbs, the nature of accompanying modifiers, modals and modifiers of various sorts, and encyclopedic knowledge. We will return to the role of context in suggesting (or determining) the readings of nominalizations in section 6.2.2.

We illustrate these readings in (21) and (22), all of which contain nominalizations of the verb kill, (21) the conversion form and (22) the -ing form:

(21) Conversion

(a) Unbounded reading

Bioscience 2002: At the peak of the KILL, we counted only 18 carcasses at the site where thousands had died after Bonnie.

(b) Bounded reading (completive)

Sports Illustrated 1993: The grebes contained a level of selenium three times greater than that found in birds in 1989, and selenium poisoning is seen as a contributing factor in the massive KILL.

(c) Bounded reading (package)

Boys Life 2004: ‘Now we have a real chance for a KILL,’ River said.

(22) -ing nominalization

(a) Unbounded reading

E: The Environmental Magazine 1998: Defenders has said all along that the biggest threat to wolf recovery would be illegal KILLING, and illegal killing is what results if the public isn't engaged.

(b) Bounded reading (completive)

America 2006: The reaction of the pope's representative in Anatolia to Santoro's KILLING, however, suggests that the anti-Christian violence was about much more than the cartoons.

(c) Bounded (package)

Rolling Stone 2006: And for kids who played any part in a KILLING, what awaited them was the world's most draconian verdict: mandatory life in prison without parole, also known as LWOP.

The differences in reading are subtle, but we think significant. In the (a) examples the nominalizations suggest events in progress, processes whose beginning and endpoints are irrelevant; in (21a) the noun phrase ‘At the peak of …’ suggests the on-going nature of the event, as does the modifier ‘all along’ in (22a). These are therefore unbounded in our sense. In both the (b) and (c) examples the temporal boundaries of the events are relevant; the nominalizations are therefore bounded in our terminology. We believe, however, that the (b) and (c) examples are not bounded in exactly the same way. Note that the verb kill has an implied endpoint; kill is a lexically telic verb. That implied endpoint is carried over to the nominalization, but it is not always the focus of the nominalization in context. In the (b) examples, we do find a focus on the endpoint: the ‘massive kill’ in (21b) is a done deal, the endpoint has been reached and is the focus, as is also the case in (22b), where it is Santoro's deadness that the Pope is reacting to. In the (c) examples, the nominalization in each case is interpreted more as ‘an instance of verb-ing’; the event is temporally packaged, looked at as a whole; the focus is not on the implied endpoint. The bounded reading in the (b) examples illustrate the bounded-completive reading and the ones we find in the (c) examples the bounded-package reading.

What is notable here is that the availability of the readings clearly does not follow from the type of nominalization (conversion or -ing), since all three readings are available in both sorts of nominalization. Indeed, if either reading is available for the conversion or -ing nominalization on a given verb, we might expect that it is possible for the readings of conversion and -ing nominalizations in some cases to be indistinguishable. In other words, we might expect to find doublets. And indeed we do:

(23)

(a) gurgling/gurgle

The Grim Grotto 2004: The three Baudelaires sighed, and for a few moments the siblings sat quietly on the toboggan and listened to the GURGLING of the stream.

Christian Century 1993: The GURGLE of waste water and the chemical stench punctuated Sister Susan Mika's description of the harsh living and working conditions along the border.

(b) hiring/hire

ESPN 2017: Since the HIRING of Scott Perry as general manager in July, New York has changed course on the asking price for Anthony and has been pushing for a return of assets that Houston is unable to provide.

Sports Illustrated 2016: So Scarlet Knight fans should be happy with the HIRE of Ash, who served as Urban Meyer's defensive coordinator at Ohio State for the past two seasons and led the Buckeyes to consecutive top-20 finishes in total defense.

So we can set aside the existence of a simple correlation between type of nominalization and aspectual reading. But we must still ask some further questions about aspectual interpretation. First, are all three aspectual interpretations always available with both conversion and -ing forms? Do we find unbounded, bounded-completive and bounded-package readings as freely for all verbs as we do for the verb kill? Is there any relationship between the lexical aspect of the base verb and the potential aspectual readings of the conversion and -ing forms? We turn to these questions in the following sections.

6.2.1 The effect of lexical aktionsart of the base

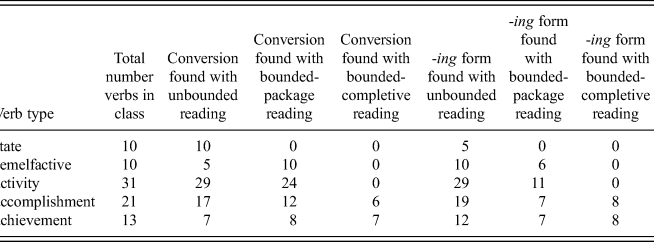

One clear factor in determining the range of aspectual readings available in conversion and -ing nominalizations seems to be the lexical aktionsart of the base verb. We summarize our findings in table 2, where we show the total number of verbs we examined for each aktionsart and how many of those verbs exhibited the unbounded, bounded-completive or bounded-package reading in either their conversion nominalization or their -ing nominalization.

Table 2. Aspect and aktionsartFootnote 21

So, for example, of the 31 activity verbs we examined, we found conversion examples for 29 of them which we deemed to display an unbounded reading, 24 with a bounded-package reading, but none with a bounded-completive reading. For those same 31 activity verbs, 29 of them exhibited unbounded readings for their -ing forms, 11 displayed bounded-package readings, but none of them exhibited a bounded-completive reading. Note that the 29 verbs found with an unbounded reading in their conversion nominalization are not necessarily the same 29 verbs found with an unbounded reading in their -ing nominalization, although of course there is substantial overlap.

Some patterns that emerge in table 2 are not particularly surprising. For example, if the base is a state verb, the interpretation of both the conversion nominalization and the -ing nominalization is always unbounded.Footnote 22 For nominalizations with activity verbs as bases, either unbounded or bounded-package readings are possible. What we never find are bounded-completive readings either for the conversion nominalization or the -ing nominalization. Semelfactives behave exactly as activities do. For nominalizations whose bases are lexical accomplishments and achievements, we again find both unbounded and bounded-package readings, but for some nominalizations bounded-completive readings are available as well. The most important finding here is that the bounded-completive reading is only available if the base verb is an accomplishment or achievement, in other words, if the base verb has an implied endpoint. Note that kill (illustrated in (21) and (22) above) is rare, in that it shows the full paradigm, that is, all three readings for both the conversion and -ing nominalization. As we saw with quantification, individual nominalizations can be idiosyncratic about which of the three readings they favor. It nevertheless emerges quite clearly that the lexical aktionsart of the verbal base has some influence on the range of aspectual readings that conversion and -ing nominalizations can display.

The form of the nominalization, on the other hand, appears at best only weakly to affect the availability of readings. As table 2 suggests, either conversion or -ing nominalizations easily express the unbounded reading. The bounded-package reading occurs with either kind of nominalization as well, but somewhat more consistently with conversion nominalizations than with -ing nominalizations. Given that all three of the readings can be found with either conversion or -ing nominalizations, however, we cannot claim that the readings are to be attributed directly to the type of nominalization.

6.2.2 The relationship between context and reading

We now turn to the question of the relationship between context and the aspectual and quantificational interpretations of nominalizations. We find that there are several contextual factors that influence whether a given conversion or -ing nominalization can be read as bounded or unbounded: the adjectives that modify the nominalization, the presence or absence of an of-PP complement to the nominalization, the tense of surrounding verbs, and whether the nominalization is count-quantified or mass-quantified. In addition, there are cases where it appears that the reading follows from encyclopedic knowledge, rather than purely grammatical contextual factors.

6.2.2.1 Modification

Adjectives like constant, prolonged, sustained, steady, long, continuous and the like can induce or enforce unbounded readings in both conversion and -ing nominalizations. This unbounding is straightforward when the nominalizations are based on states, activities, or accomplishments. However, the nominalizations may be read as unbounded and iterative if they are based on achievements or semelfactives. (24) illustrates these readings for -ing nominalizations and (25) for conversion nominalizations:

(24)

(a) Unbounded -ing nominalization (ordinary unbounded)

Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development 1997: Any unfavorable biomechanics that prevail during performance of the Biering-Sorensen test are also likely to exert an effect during everyday activities, because in tasks that involve prolonged BENDING and lifting, the upper body must always be supported in addition to any external load.

(b) Unbounded -ing nominalization (iterative unbounded)

World Literature Today 1998: After ten minutes of continuous KNOCKING Danny realized that it wasn't a passing train going choo-choo.

(25)

(a) Unbounded conversion (ordinary unbounded)

New York Times 1997: But in Guangdong Province in southern China, there has been a slow SPREAD of so-called open churches, Roman Catholic communities that give fealty to Rome rather than to the Patriotic Association.

(b) Unbounded conversion (iterative unbounded)

Houston Chronicle 1992: The only interference: the constant FLASH from camera bulbs and the few fans with the temerity to speak up.

6.2.2.2 Of-PPs

Of-PPs, which correspond to the internal/object argument of the verb can, on the other hand, induce telicity and therefore make bounded-completive readings possible in nominalizations based on activity verbs if the object of the preposition of is definite and singular. This of course corresponds to the observations of Verkuyl (Reference Verkuyl1972, Reference Verkuyl1993, Reference Verkuyl1999) that telicity can be induced in activity verbs by the addition of an object which is singular and definite.

(26) -ing nominalization with of-PP and bounded reading

Denver Post 1998: Paul saves Misty from drowning during the SWIMMING of the channel between Assateague to Chincoteague.

(27) Conversion nominalization with of-PP and bounded reading

Backpacker 2011: One says that the extra fabric prevented him from being able to see his feet during a CLIMB of the Great White Icicle in Utah.

Note that in the example in (27) the count-quantification of the conversion nouns also helps to suggest the bounded reading, as we will discuss in section 6.2.2.4 below.

6.2.2.3 Verb tense

It also appears that surrounding verb tenses can influence whether a given instance of conversion or -ing nominalization be read as bounded or unbounded. Consider the examples in (28), all nominalizations of the accomplishment verb burn:

(28)

(a) Conversion/past tense/bounded-package

Conservationist 1992: It is probable that this area remained in a somewhat open condition for the first 60 years following the initial BURN.

(b) Conversion/non-past tense/unbounded

Popular Mechanics 2003: This will slow the idle and provide a longer, hotter BURN.

(c) -ing nominalization/past tense/bounded-completive

CBS_Sixty 1996: This former Area 51 worker says the open-pit BURNING was executed with extraordinary security.

(d) -ing nominalization/non-past tense/unbounded

BNC Other Pub 1990: Friends of the Earth desperately needs your help now to prevent the greatest man-made ecological catastrophe yet known: the systematic BURNING of the Amazon Rainforest.

In (28a), the past tense of remain suggests that we read the conversion noun burn as temporally bounded, an instance of burning that has already happened. In (28b) the tense is non-past and suggests a process rather than a completed event. Similarly for the -ing nominalizations, in (28c) the past tense suggests a completed event, (28d) an on-going process with no temporal boundaries in view. Note that our point is not that verb tense determines the reading, just that in some instances it contributes to the reading.

6.2.2.4 Quantification

Another contextual factor that contributes to our reading of nominalizations as bounded or unbounded is whether they are count-quantified or mass-quantified in a particular context. Recall that we argued in section 6.1 that quantification is not correlated with the form of nominalization (conversion or -ing). Either conversion forms or -ing nominalizations can be count or mass, with nominalizations of some verbs showing preferences for one sort of quantification or the other and nominalizations of other verbs being rather freer in their choice of quantification. For those that are rather free in their choice of quantification, we sometimes find that count quantification can contribute to a bounded reading whereas mass quantification of the same nominalization contributes to an unbounded reading. Consider the examples in (29) and (30):

(29) Conversion

(a) Massachusetts Review 1996: Once or twice he made love to Mimi with a BURN of wintry anger that scared him.

(b) Associated Press 2002: The vaporizing of air conditioning was also a sign of some BURN.

(30) -ing nominalization

(a) BNC Fiction 1993: A low pall of smoke hung over the nearby buildings; there had been a dawn funeral, a BURNING.

(b) Science News 1990: Those agencies, which once emphasized the destructive potential of forest fires with publicity campaigns featuring such symbols as Smokey the Bear, today recognize that the forest can actually benefit from some BURNING.

In the (a) examples, the count-quantification helps to suggest a bounded-package reading. The (b) examples have mass quantification and are more comfortably read as unbounded. Again this correlation between count-quantification and bounding, mass-quantification and unbounding is a tendency rather than a hard and fast correlation.

In fact, the ability to occur in the plural is a hallmark of count quantification, and pluralization can lead to an unbounded iterative reading for both conversion and -ing nominalizations, especially if they are based on semelfactive verbs. For example, with a semelfactive verb like knock, pluralization results in an interpretation of repeated action regardless of whether we have a conversion or an -ing nominalization:

(31) Fantasy & Science Fiction 2001: I could hear my breathing and the clicks and KNOCKINGS as the trees contracted with the night.

People 1996: Her KNOCKS turned into pounding; her voice became furious.

What this suggests, again, is that elements of context are instrumental in building the ultimate construal of any given nominalization.

6.2.2.5 Encyclopedic knowledge

Finally, we come to the role of encyclopedic knowledge in influencing the reading of nominalizations as bounded or unbounded. Consider the example in (32):

(32) Science News 1998: Ongoing volcanic eruptions, the SHIFTING of the continents due to the movement of tectonic plates, and other large-scale makeovers have erased Earth's original surface.

The verb shift is typically a lexical achievement. It usually has an implied endpoint, and we might therefore be inclined to interpret the -ing nominalization as bounded. Further, the tense is present perfect, also nudging us towards a bounded interpretation. But for the geologically savvy, the knowledge that continents are always undergoing infinitessimal changes in position, pushes us in the direction of an unbounded interpretation.

Similarly, we might expect the conversion noun stir to have an unbounded reading, as it does in (33a), but the context in (33b) suggests that what is involved is a single motion of the wings, that is, a bounded reading.

(33) (a) Lethal Rider 2012: His mind was whirling in a STIR of a thousand thoughts, and he couldn't focus.

(b) San Francisco Chronicle 1990: One of the latest developments in physics is chaos theory, with its story that the STIR of a butterfly's wings could set in motion a chain of events resulting in a storm on the other side of the planet.

The bounded reading in the case of (33b) depends on the general context available in the discourse about physics, rather than in any strictly grammatical feature of the sentence in which stir is used.

7 Theoretical implications

We have found that there is no correlation between the type of nominalization (conversion or -ing) and its reading as referential or eventive: most conversion and -ing nominalizations have the potential for either interpretation. It also seems clear that verbs of any lexical aktionsart can occur as either conversion or -ing nominalizations. We find as well that there is no correlation between type of nominalization and mass or count quantification: conversion nominalizations can be count or mass as can -ing nominalizations. Nor is the type of nominalization tied to either bounded or unbounded readings, where by bounded we mean having a clear temporal endpoint: conversion nouns may be bounded or unbounded as may -ing nominalizations. However, we do find some effect of the aspectual class of verbal bases on the range of potential aspectual readings, in the sense that only nominalizations based on accomplishments or achievements have the potential to display bounded-completive readings. And finally, a range of contextual features can affect the aspectual reading of both conversion and -ing nominals, including temporal modifiers, verb tense, quantification and encyclopedic knowledge.Footnote 23