Introduction

The presence and influence of peripheral elites in West European national political institutions is frequently handled by the press. Newspapers from different countries regularly focus on the geographic origin of cabinet ministers or on the regional politicians present at the head of national parties. But, oddly enough, those features are explored separately, without any general theoretical framework able to orient those fragmented researches.

Though consistent studies have addressed those questions in other geographical areas (Farmer Reference Farmer1985; Goati Reference Goati1997), the West European case has remained relatively unhandled. This intellectual myopia may explain the two main biases present in most of publications. On the one hand, most newspapers’ articles fail to avoid the “palimpsestic syndrome” identified by Merton (Reference Merton1965). This bias supposes the constant reinvention of the wheel – in this case, the rediscovery of regional minority networks in the central state institutions – and a lack of knowledge accumulation in this field. On the other hand, the lack of a comprehensive vision of this issue tends to feed flashy titles alerting about the influence of the “Scottish Raj,” the “Tartan mafia,” and the “Cosa Scotia” in London (The Guardian, March 18, 2005; Daily Mail, September 4, 2008; The Economist, October 26, 2013), the “Breton lobby” and the “Corsican connection” in Paris (New York Times, May 18, 2012; Le Monde, July 20, 2013), the Catalan and Galician pressure groups in Madrid (El País, October 17, 1987; La Voz de Galicia, July 2, 2010), or the “Bavarian power” in Berlin (Politico, October 16, 2018).

This introduction assumes that those topics represent the different expressions of a single political phenomenon. This issue is of great interest for political science since it shows the importance – real or imagined – of some territorial groups in national politics, and, as such, it deserves a specific treatment based on a scientific methodology. For this reason, the experience of the panel “Peripheral Elites in the Central State’s Apparatus” held at the General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research in Wroclaw (Poland) in September 2019 motivated this special issue proposal. Concretely, this article investigates those regional communities in West European countries’ central institutions through a review of the publications in this field. Such a task is complex since international comparisons must use comparable units of analysis based on robust concepts able to travel from one context to the other. So, how to define notions such as “peripheral elites” and “central state apparatus”?

To a large extent, the concept of peripheral elites draws on the legacy of the Stein Rokkan’ studies on the process of state formation in Western Europe (Eisenstadt and Rokkan Reference Eisenstadt and Rokkan1973; Rokkan and Urwin Reference Rokkan and Urwin1983). This historical dynamic involved the concentration of power in some territories at the economic, cultural, and military-administrative levels. This dynamic has later been strengthened by the process of European integration (Stefanova Reference Stefanova2014). The consequence of the state-building process was the creation of peripheries with a different degree of integration with respect the center: pure peripheries (strongly dependent and assimilated like Wales, Brittany, Wallonia, or Andalusia) and failed cores (that almost reached their independence over time and where a substantial feeling of distinctiveness remains such as Scotland, Catalonia, Basque Country, South Tyrol, or Flanders). The present study focuses on both dimensions.

In the same way, the concept of central state apparatus was adopted for enlarging the scope of this review. At first sight, this concept has a Marxist connotation and Gramsci (Reference Gramsci1975) himself discussed the concept with regard to the center-periphery dimension in his Notebooks from Prison (Mussi and Goès Reference Mussi and Goés2016). In line with the Gramscian concept of hegemony, Althusser (Reference Althusser1970) developed the concept of ideological state apparatus (e.g., school, family, mass-media, churches, or laws) in opposition to the repressive state apparatus (judiciary, police, and armed forces) for explaining the source of alienation in post-industrial societies. Nevertheless, in the present context, state apparatus must be understood as a neutral and quick way to encompass the whole central state institutions into a single definition – that is, judiciary, legislative, and executive along with their bureaucratic branches.

In accordance with this approach, this literature review was led from May 2018 to June 2020 through two main datasets: JStor and Ingenta Connect. It presents those results in six sections. The ways in which peripheral elites get access to central institutions are analyzed in the first section. In the second one, we introduce the literature about the presence of peripheral elites in the state apparatus, before stressing the different networks representing the interests of peripheries in the city capitals in section three. Fourth, this article points out the various career orientations of peripheral elected officials. This leads us to question their policy influence in different fields. Lastly, a short section tackles the phobias provoked by the rise of peripheral elites occupying central political positions, before proposing a general framework designed for orienting future research on this topic and to introduce the different papers composing the special issue.

Access to National Politics

According to the literature, the access of peripheral elites to national politics can be represented as a continuum between two mechanisms according to their degree of institutionalization. On the one hand, the clientelist networks based on individual relationships can help regional politicians to get access to power within the central state institutions. Following the tradition of the 19th century’s political patronage, territorial barons can favor the rise of local elected officials at the central level by using their personal influence. This was especially true in centralized countries such as France and Italy, as shown by Tudesq (Reference Tudesq1964) in his study on the grands notables (political barons) under the July Monarchy, or in the analysis of Musella (Reference Musella1984) on the agrarian policy in Italy (but see also: Caciagli Reference Caciagli1977; Gribaudi Reference Gribaudi1980). To a certain extent, this central-local nexus survived over time when Grémion (Reference Grémion1976) proposed his model of “peripheral power” to depict the interactions between local and central politicians through the intermediation of French préfets.

On the other side of the continuum, the appointment of peripheral elites at the central level can also be regulated by consociational arrangements planned by the constitution. In territories such as Switzerland, Northern Ireland, or Belgium, the selection of cabinet ministers relies on political party, religious, and language criteria. But those systems of peripheral representation must not be considered as isolated cases. Even the majoritarian cabinets aim to represent peripheral elites. This is particularly visible in the Canadian federal government where the Francophones are always present (Whittington and Van Loon Reference Whittington and Van Loon1987), in Italy where the special statute regions are represented (Dogan 1989), or in the United Kingdom through the appointment of Scottish and Welsh ministers (Elliott Reference Elliott2018).

Eventually, in contemporary democracies, political parties can be considered as an instrument of peripheral representation lying between those two poles (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2014). Political parties largely control the recruitment of state’s elites through the promotion of politicians coming from their local electoral fiefs. This is the case of the Corsican leaders promoted by the Gaullist party in France since the 1950s (Martinetti and Lefèvre Reference Martinetti and Lefèvre2007), or the Scottish deputies and ministers belonging to the Labour Party before the devolution (McLean, Gallagher, and Lodge Reference McLean, Gallagher and Lodge2013). But this picture would not be complete without taking into consideration the influence of region-wide parties. Actually, several political formations operating at the sub-state level can impose their candidates to central institutions. The first mechanism relies on the complementarity between a state-wide party and its local branch (e.g., the Christian Social Union in Bavaria and the Christian Democratic Union of Germany, or the Socialists’ Party of Catalonia and the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party in the rest of Spain) (Münch Reference Münch1999; Roller and Van Houten Reference Roller and Van Houten2003). Another modality can occur when a government of coalition includes a regionalist partner such as the Lega Nord in 1994. The success of this coalition allowed the Lombardian and Venetian leghisti to become elected officials at the national level (De Winter Reference De Winter, de Winter and Türsan1998).

Presence in Central Institutions

Most studies have focused on the gender, ethnicity, and social class of elected officials by crossing two dimensions: a quantitative account of minority groups and an analysis of their relevance within the representative institutions (Philips Reference Philips1995). However, this “descriptive representation” can also be handled from a territorial perspective (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). From this viewpoint, the three branches of state power have been subject to scrutiny. For what regards the executive and public administration, the geographic origin of ministers, secretaries of state, general directors and their staffs has been widely discussed in Europe and outside (Blondel and Thiébault Reference Blondel and Thiébault1991; Dowding and Dumont Reference Dowding and Dumont2009; Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1994). Those studies have demonstrated the importance of the territorial selection at the central level. As a matter of fact, despite the inexistence of a “magic formula” for appointing cabinet members as in Switzerland, there is an unwritten rule known as the cuota catalana in Spain that traditionally imposes at least one Catalan minister in the cabinet (Cuenca Toribio and Miranda García Reference Toribio, Manuel and García1987). Likewise, even in unitary states as France, the recruitment of Breton ministers has been constant since the Fourth Republic, while in Italy more than 60 ministers from Lombardy have been part of every national cabinet since the start of the Second Republic in 1994.

Secondly, the composition of the judiciary power has also caught much attention, especially in countries where constitutional quotas impose to represent the different segments of society. In Switzerland, Cyprus, or Belgium, the professional background of constitutional judges is taken into consideration along with their language community of origin. The criteria followed for appointing justices in those countries demonstrates the aim to reinforce the territorial representation in order to avoid any criticisms against the objectivity of judges (Choudhry Reference Choudhry2007; McCrudden and O’Leary Reference McCrudden and O’Leary2013).

Finally, national parliaments have also generated a considerable scientific interest. Obviously, lower chambers are supposed to represent the whole population(s) of a given country, including the peripheral areas. This explains the rise of research on the presence of peripheral nationalist parties and/or national minorities within national parliaments (Jolly Reference Jolly2015). But not all the deputies compete for representing their community of origin. This is why the analysis of “parachute” candidates – that is, the candidates presented by a party in a constituency distinct from their place of birth – can say a lot about the territorial dynamics of parliamentarian representation and national integration. For instance, Steinhouse (Reference Steinhouse2005) and Berry (Reference Berry2013) have pointed out the overrepresentation of parachuted Scottish deputies in English constituencies at the British general elections. According to some authors (Elliott Reference Elliott2018), this would demonstrate the high integration of Scots in British politics, as integral components of the electoral system.

Networks in City Capitals

The issue of presence leads to observe the representation of peripheral elites out of the official political institutions. Most researches have shown the capacity of those communities to rebuild their regional connections in city capitals. Historically speaking, religious and charity organizations were the main entry doors for new comers. For instance, the ScotsCare, the London Welsh Centre, or the Service social breton supported immigrants arriving to London or Paris since the 19th Century. Those spaces of socialization allowed the diaspora’s members to interact together far away from their homeland. They also showed the robustness of the exiled community with respect to their host society, and they worked as an instrument of defense and affirmation of the identity of their members (Dufoix Reference Dufoix2008). In some cases, those connections have been formalized through public-funded regional cultural centers in the city capital as the Centro Gallego de Madrid, the Basque Euskaletxea in Paris, or the Casa delle Associazioni Regionali in Rome.

Beyond this “bonding” dimension, some of those institutions also aimed to go a step further by building bridges with the rest of the local society. This is the case of the well-established Dîners celtiques where Breton businessmen meet their French counterparts. The same could be said about the Caledonian Society (one of the most enduring Scottish institutions in London), the Scottish Business Network, and the Wales in London Association. More recently, the Corsican lawyers’ Association des Corses du Palais opened its doors in Paris. It followed the previous examples of the Cercle Sampieru and the several Corsican masonic lodges present in Paris (as the Fraternelle Pasquale Paoli, for instance). In Spain, the Fòrum Pont Aeri has also consolidated as an institution representing the Catalan business milieu – along with politicians – to meet the economic and political Spanish elites in Madrid (El País, November 20, 2014; Lucas Reference Lucas2011; Nouzille Reference Nouzille2011; Steinhouse Reference Steinhouse2005).

Career Orientation Paths

The role of peripheral politicians in national politics is often criticized. On the one hand, national mass media are likely to consider them as the Trojan horses of vested local interests within the central state apparatus. On the other hand, peripheral electors usually believe that their representatives stop caring about their place of origin after they get a national political position. This tension between localism and centralism lies at the core of the political orientation of peripheral elected officials. As Keating (Reference Keating1978) pointed out in a seminal paper about the role of Scottish deputies at the House of the Commons, those members of parliament can be more or less state or region-oriented. But those territorial allegiances are much more fluctuant than it might be assumed at first glance.

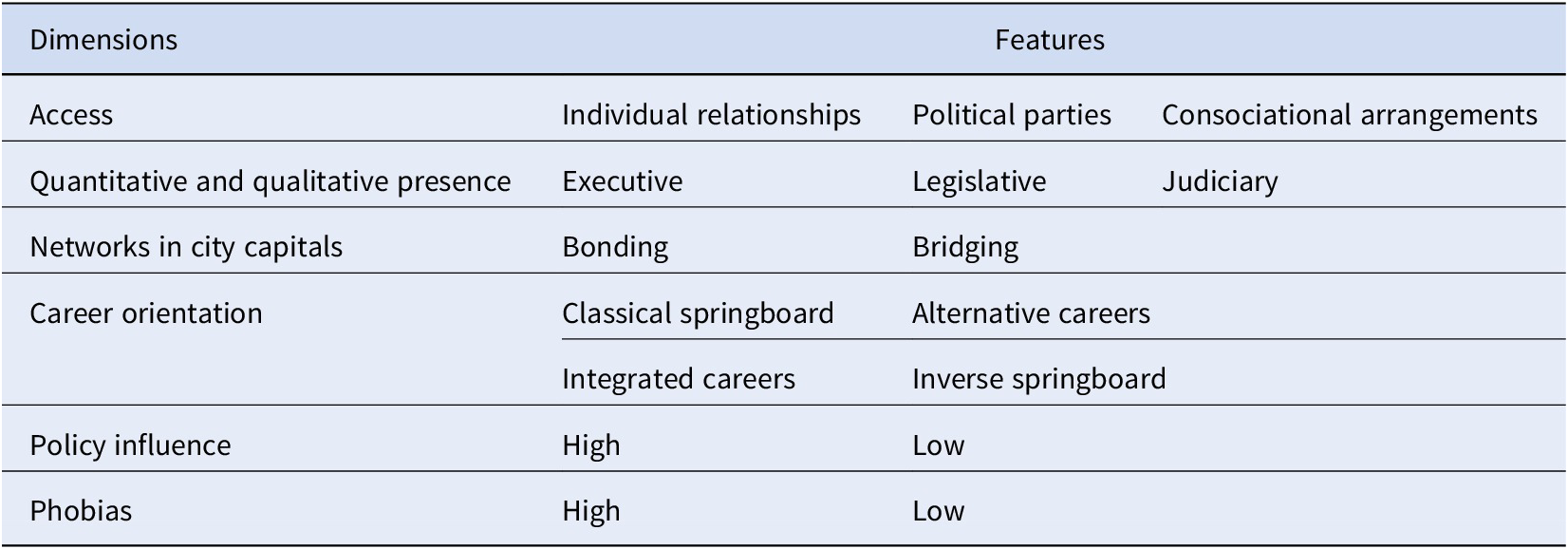

According to Borchert and Stolz (Reference Borchert and Stolz2003), political careers are based on individual strategies within a given structure of opportunity. Peripheral politicians move from one position to the other at the state and sub-state levels according to their availability, accessibility, and attractiveness. In a book published in 2000, Francis and Kenny (Reference Francis and Lawrence2000, 3) considered the political career as a succession of jobs based on two “ambition principles” leading to pursue higher offices. According to those authors, politicians aimed “to increase their territorial jurisdiction” and “to increase the size of their electoral constituency.” Nevertheless, while it is obvious that top political positions are to be found in capitals like Paris, London, Stockholm, Madrid, Rome, or Berlin, this typology does not constitute an iron law. As Table 1 illustrates, different patterns can be identified.

Firstly, the “classical springboard” cell includes the cases of peripheral politicians following the steps described by Francis and Kenny, from a local office to a national position in the city capital. For instance, in France, the United Kingdom, or Belgium, most cabinet ministers and deputies progressively hold offices at the local level in order to reach national positions (Van de Voorde Reference Van de Voorde2019). Secondly, the concept of “alternative careers” depicts the cases of clear separation between region-oriented elected officials and their national counterparts. In practice, the circulation of elites from local to national areas (and vice versa) is difficult to stop; but literature on local government has shown that the access to national politics was more difficult in some states, such as the Nordic countries (Wolman Reference Wolman2008). Alternatively, the existence of strong and attractive regional institutions, as in Italy, can provide an incentive to “integrated careers,” that is, those consisting in jumping from one office to the other or holding multiple offices at the same time, independently of their territorial level (Verzichelli Reference Verzichelli2010). Finally, the attractiveness of political positions at the regional level can convince national-oriented candidates to run for elections in the periphery (“inverse springboard”: e.g., Manuel Fraga, the former Francoist minister and founder of Alianza Popular who became president of Galicia in Spain) (Genieys Reference Genieys2004).

Policy Influence

Evaluating the power and influence of peripheral minority representatives within the central state institutions is complex as there is no natural way to measure those phenomena. As such, power is a dynamic and multidimensional notion. Typically, it can be depicted as the hard or soft control exerted on resources (extraction and sharing), persons (in order to oblige someone to do something that he/she otherwise not do), or even situations (by imposing or blocking the agenda) (Dahl Reference Dahl1957). This issue is central for assessing the capacity of peripheral elites to influence the national policy process (Mazzoleni and Müller Reference Mazzoleni, Müller, Mazzoleni and Müller2016).

In terms of policy approach, the publications tackling the influence of peripheral elites on national policies show a large range of potential situations. At first sight, it is commonly assumed that peripheral politicians aim to defend their territory of origin for reinforcing their electoral basis (Boix Reference Boix1998; Pasquier Reference Pasquier2015). Indeed, this is the classical complaint addressed to the Corsican, Basque, or Scottish politicians in office who have been able to get and/or to retain fiscal “privileges” for their respective regions. The limits imposed to the value added tax, the existence of a specific fiscal regime, or the Barnett formula, respectively, have imposed a conception of peripheral elected officials as successful rent-seekers operating for their political fiefs according to a pork barrel logic.

However, this vision is clearly partial. Firstly, not all peripheral elites struggle for their territory of origin, and most of them are rather state-oriented (Basile Reference Basile2018). Secondly, other researches have demonstrated that the peripheral elites who defend their local interests are not always so successful. For example, it is worth noting the incapacity of the Breton national ministers under the presidency of François Hollande to tame the crisis of bonnets rouges (red caps) in 2013 in France. Such a protest appeared initially in Brittany when farmers and agri-food industry workers revolted against a new eco-tax on freight transportation by trucks (Cole and Pasquier Reference Cole and Pasquier2015). Similarly, the Catalan nationalist deputies in Madrid were unable to stop the activation of article 155 in Catalonia between 2017 and 2018. In the name of the concept of federal loyalty, this constitutional article allowed the Spanish central government to take the control of regional institutions after the organization of the 2017 referendum of independence. As a result, the Catalan executive lost its grip on Catalan politics for a couple of months (Lafuente Balle Reference Balle and María2018).

So, how to deal with those contradictory evidences? In order to understand the structural conditions of peripheral influence, it is necessary to have a look at the sociology of policy elites. As Nay and Smith (Reference Nay, Smith, Nay and Smith2002) have demonstrated, the power of peripheral elites in national policies depends mainly on their capacity to adopt a position of gatekeepers despite the constraints imposed by the opportunity structure. This means that when those actors are able to activate their regional and central networks at the same time, they can take advantage of them. By the same token, such a role of center-periphery intermediary can be more or less institutionalized depending on the existence of a ministry for administering those territories (such as the Office of the Secretary of State for Scotland). In sum, it seems that being the main interlocutor between local interests and the city capital institutions is a sine qua non condition to become a relevant territorial policy actor.

Central and Peripheral Phobias

The literature has also shown that the rise of peripheral elites can stoke up the fear of the main population about the balkanization of their country. Though those fears are sometimes based on biased representations exalted by mass-media, it is undeniable that they exist. Then, to quote a few, the (supposed) power of Scottish ministers, the (hypothetical) influence of Corsican top-level civil servants, or even the (theoretical) hidden agenda of Catalan deputies have boosted a certain resentment against those minorities. The dynamic of fear usually follows the same trend (Stenner Reference Stenner2005). After a long period of union (since 1707 in Scotland, 1768 in Corsica, and 1714 in Catalonia, for instance) the largest community of people of the host state discovers that some elected officials coming from the periphery have accumulated a relevant amount of power at the central and/or regional level(s). Following a logic of metonymy, those isolated politicians are assimilated to their regions of origin and said to represent a threat for the national sovereignty. This finding sounds the alarm vis-à-vis any attempt to break up the territorial unity of the country.

At this point, three elements should be emphasized to understand this process. Firstly, the different degrees of Scotophobia, Catalanophobia, Corsicaphobia, or others do not depend on a single issue; they rather represent the products of complex contexts. Secondly, they are not new phenomena since those waves of resentment started with the inclusion of those peripheral territories to their state of reference. Thirdly, all those phobias share a common ground: the fear of disunion and the reaffirmation of the center. In England, for instance, there is little doubt that the inclusion on the agenda of the English question and the growth of English nationalism are by-products of the devolution process launched by Tony Blair and Gordon Brown (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Lodge, Henderson and Wincott2012). In Spain, the “balcony politics” consisting in displaying the Spanish flag as a symbol of Spanishness against the 2017 Catalan referendum of secession also provoked a mistrust with respect Catalan politicians – independentist or not (New York Times, October 7, 2017). In France, the demonization of Corsican elected officials – especially those related with independentism – also relies on a biased perception of the aim and real power of those actors within the French institutions. Those latent phobias arose once again after the 2015 victory of Corsican nationalists at the regional elections (Le Monde, December 14, 2015). In Italy, ministers and Prime Ministers coming from the mezzogiorno have regularly triggered harsh criticism and controversies from Lega’s politicians and Northern political elites (Carboni Reference Carboni, Mammone and Veltri2010). Recently, the fact that the new Conte government formed in August 2019 was composed by 12 Southern ministers over the 22 in total has unleashed unprecedented criticism from the previous government coalition member, the Lega. To sum up, the periods of emergence of peripheral independentism can (re-)activate the resentments against peripheral elites by obliging them to choose which side they are on.

Structure of the Special Issue

At this stage, this short overview about peripheral elites in state central institutions can be handled in three ways. Firstly, it can be read as a literature review, that is as a descriptive assessment of the main trends structuring this scientific field. Secondly, it also can be used as a tool for orienting future research programs dealing with the rise of elected officials coming from the margins of the state. As we shown, at least six features can be taken into account to understand such a phenomenon (access, presence, network, career orientation, influence, and phobia) in order to start to build a general theory, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Six dimensions of peripheral elites in central state apparatus.

Source: The authors’ own elaboration.

Thirdly, this introduction can also be considered as a roadmap to read the papers composing this special issue. Those articles were conceived as a major contribution toward a better understanding of minority elites in central state institutions. They are organized in three parts. The first three analyses present research findings from West European countries. Dandoy’s paper takes into account the Belgian case. This author argues that most studies have put to the fore the relevance of ethnic divisions at the regional level in Belgium. Nevertheless, local-provincial cleavages still structure this political system. In order to demonstrate the importance of localism, Dandoy observes the dynamics linked to the presence of ministers from small and peripheral provinces and their cultural claims in the Belgian cabinet. The second country explored for the purpose of this special issue is Switzerland. In his analysis, Müller focuses on cantons. He demonstrates the persistence of ethnic-cultural differences over time and their impact on Swiss contemporary politics by comparing their presence in the federal government and the results of local referendums. The last article of this section is the product of a research about the nature of Italian national ministers. The authors – Tronconi and Verzichelli – explore the change that occurred over the last decades within the state government. The traditional territorial representation of all regions – and especially the special statute ones – has been replaced by the recruitment of policy experts. This dynamic has pushed peripheral elites to follow their political career in decentralized institutions rather than at the national level.

The second thematic block centers on specific regional cases. Fernández Rivera, Harguindéguy and Rodríguez Teruel aim to understand who the Catalan ministers are and which function they perform in the Spanish central government. Drawing on an original dataset of cabinet ministers from 1977 to 2021, and a subset of Catalan ministers, the authors stress the frequent interference of Catalan regional formations in the appointment process, the historical under-representation of Catalan ministers, and their traditional role of intermediaries between central state and Catalan regional institutions. Lastly, Pasquier and Cole reflect upon the case of Brittany in contemporary France. The Breton political model is commonly identified as being based on cross-partisan consensus and regional advocacy, a post-war model of public action that was built upon inter-war failure of a more assertively nationalist movement. Pasquier and Cole question the political capacity of this peripheral territory to reactivate this singular peripheral model of action nowadays.

The last section of the special issue includes two original articles proposing new approaches for analyzing peripheral elites in terms of public policy (Terrière) and parachuted candidates (Domínguez and Portillo Pérez). The former article investigates the minister portfolio preferences of regionalist parties defending the interest of territorial minorities. Through a quantitative dataset comparing several countries since the Second World War, Terrière shows how regionalist parties focus on issues belonging to their territorial core business during their first legislature in central government (i.e., the defense of their cultural particularity) and how they broaden their main interests in consecutive legislatures. The latter proposal of Domínguez and Portillo Pérez, and analyzes how the inclusion of parachuted deputies (i.e., those not born in their constituency) can affect the territorial representation since most of them are from the Madrid’s region. Through an original dataset, the authors evaluate the capacity of resistance of the constituencies with a different feeling of belonging (e.g., Basque Country and Catalonia) to favor local candidates.

Financial support

UPO-FEDER (Government of Andalusia) Grant 1380883.

Disclosures

None.