Impact statement

Plastic products used throughout the agricultural sector provide many benefits, but their usage and disposal come with environmental trade-offs ‒ including large amounts of waste and pollution. A report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO, 2021) set the stage to initiate the preparation of an international voluntary code of conduct (VCoC) on the sustainable use and management of plastics in agriculture. The use of plastics in agriculture, including in fisheries and aquaculture, is also considered during negotiations of the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment. Despite research advances, knowledge gaps persist concerning the short- and long-term implications of plasticulture. Agronomists, farmers and the industry emphasise the benefits of using plastic-based production systems for increased yields, resilience and efficiency, while environmental scientists and organisations raise concerns about negative environmental implications resulting from certain practices and improper waste management. This dialectic is mirrored in the debate surrounding the policymaking in this area where opposing views are sometimes expressed. Understanding and solving, where possible, counterposed concerns is key to the effective implementation of future regulation. This paper systematically collects and summarises the current perspectives from different stakeholders and provides an essential background highlighting the existing knowledge gaps that influence such diverse standpoints. As a result, it serves as an important document to initiate and stimulate a constructive dialogue, which will prove instrumental in policymaking within this field.

Background

Agricultural plastics at a glance

Plastic is an important commodity for the agricultural sector enabling innovation in production systems oriented to higher efficiency and crop reliability. In terrestrial agriculture, new options for protected cultivation systems, made possible by the introduction of plastic films, micro-irrigation systems and other plastic-based technologies, have enabled more efficient production to be partly decoupled from climatic and geographic constraints (FAO, 2021; EIP-Agri, 2024). In fisheries and aquaculture, plastic-based nets, lines and floaters, among other plastic devices, are critical for cost-effective, high-efficiency, industrial-scale operations. The consistent positive trend in the global demand for plastic in agricultural applications – increasing with a compound annual growth rate of 6.2% during the forecast period 2023–2030, reaching 10.6 billion USD in 2022 and expected to surpass 17 billion USD by 2030 (Data Intelligence, 2023) – confirms the success of this sector and the rapid assimilation by farmers internationally.

The term ‘agriplastics’ (AP) refers to any products made from plastic that are used in the production, harvesting, storage and primary distribution (e.g., from farm to wholesale) phases of terrestrial agriculture, forestry, fisheries and aquaculture (FAO, 2021). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), there were in 2021 12.5 million tonnes of AP used globally, of which 10.2 million tonnes are used for crops and livestock, 2.1 million tonnes for fisheries and 0.2 million tonnes for forestry (FAO, 2021), with an expanding trend that will possibly result in an increase of 50% between 2018 and 2030.

While some works have initiated the effort of establishing inventories of typologies and tonnages of AP at the global and regional levels (Briassoulis et al., Reference Briassoulis2013; Sundt et al., Reference Sundt2018; Cleanfarms, 2021; FAO, 2021), data on AP stocks, usage, geographical distribution, distribution along agricultural value chains and end-of-life (EoL) processes remain scant and fragmentary. APs are a source of pollution that can pose a risk to soil and aquatic ecosystems (e.g., de Souza Machado et al., Reference de Souza Machado2019; Schwarz et al., Reference Schwarz2019; Huang et al., Reference Huang2020; Kruger et al., Reference Kruger2020; Briassoulis, Reference Briassoulis2023), to vegetable crop and farmed animal health (e.g., Pizol et al., Reference Pizol2017; Qi et al., Reference Qi2018; Rillig et al., Reference Rillig2019; Galyon et al., Reference Galyon2023; Zantis et al., Reference Zantis2023) and thus, by extension, for farm productivity (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang2020; UNEP and GRID-Arendal, 2021; Wu et al., Reference Wu2022). The use of plastics in agriculture generates a large volume of waste (Briassoulis et al., Reference Briassoulis2013; Morsink-Georgali et al., Reference Morsink-Georgali2021; Koul et al., Reference Koul, Yakoob and Shah2022; Hachem et al., Reference Hachem, Vox and Convertino2023) distributed across the broader environment, which impacts terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems. Damaged, degraded, discarded or inappropriately used AP contaminate soils, freshwaters and marine waters represent a serious threat for the Earth system and economy (including at the farm level) (Vox et al., Reference Vox2016; FAO, 2021; UNEP and GRID-Arendal, 2021; Mihai et al., Reference Mihai2022).

FAO has initiated the development of a VCoC on sustainable use and management of plastics in agriculture, which if adopted will guide stakeholders to prevent or reduce the accumulation of agricultural plastic waste (APW) and plastic pollution associated with the food and agriculture sector. It is broadly acknowledged that a multi-actor and cross-sectorial approach is essential to adequately address sustainable solutions for agriculture and food systems and to catalyse innovations in AP product design, production practices, policy instruments, capacity building and financing. It is of the utmost importance that experiences and perceptions, especially of farmers developed through the everyday use of agricultural plastics and food production, are mapped and understood alongside technological opportunities and constraints, coinciding these with scientific research on soil health and plant production. In this way, a broader understanding of the status of knowledge on plastic agricultural uses, benefits, costs and impacts on environmental and human health will be developed and used as terms of reference to work towards social, environmental and economic sustainability in food production systems.

Against this background, the aim of this article is twofold: (1) summarising the state-of-the-art of the AP environmental discourse, reviewing scientific knowledge on the sources and effects of plastic pollution from the use of AP (with the latter, especially focusing on the emerging concern of plastic pollution impacts on terrestrial environments), and (2) reinforcing the science–policy interface by mapping knowledge demands and initial suggestions provided by stakeholders to understand and address negative impacts. The review builds on four components: (i) an analysis of the scientific literature available thus far on the sources and ecological and environmental impact of AP-derived debris; (ii) the inputs of 68 international experts (with geographic competence covering both high-income and low-income regions) gathered via an online focused survey – the International Survey on Agricultural Plastics’ Perspectives and Knowledge Gaps – administered by the International Knowledge Hub Against Plastic Pollution (IKHAPP, 2023) from 19 May to 9 June 2023 and by email; (iii) dialogues conducted within a group of agronomists, engineers, environmental scientists and toxicologists clustered around two large European research projects: PAPILLONS and MINAGRIS (MINAGRIS, 2023; PAPILLONS, 2024); and (iv) dialogues with industry and farmer representatives, also conducted as part of the aforementioned projects.

The ‘background’ section provides a review of APs, their uses, characteristics and their role as sources of pollution. The section ‘Environmental concerns of agriplastics’ delves into the problem of the generation and management of waste from AP as well as the ecological and potential agricultural problems posed by the accumulation of plastic debris in the environment (with a closer look into the recently emerging evidence of plastic impacts in terrestrial agriculture). Finally, the section ‘Knowledge gaps on agriplastics from a multi-actor perspective’ summarises the perspectives of the stakeholders.

While the first and second sections of this paper have a broad scope covering elements pertaining to all types of agriculture (i.e., terrestrial agriculture, forestry, fisheries and aquaculture), the multi-actor perspective analysis provided in section ‘Knowledge gaps on agriplastics from a multi-actor perspective’ of this paper deliberately focused on stakeholders specifically within the value chain of terrestrial agriculture. This narrower scope was adopted considering terrestrial agriculture and forestry represent over 80% of the plastic global demand for agriculture and that, unlike for fisheries and aquaculture, limited international debates have been so far conducted among stakeholders in the terrestrial farming and forestry sector.

Types and benefits of agriplastics for different agricultural sectors

In 2021, the world plastic production reached 390.7 Mt., with agricultural application representing around 3% of the total demand (Plastic Europe, 2022). The widespread diffusion of plastic in agricultural production stems from the multiple technical and economic benefits it offers. Plastic can be formulated in a variety of chemical blends or produced as multilayer structures with specific mechanical and physical characteristics and functionalities. While plastic can be used at any stage of agricultural production, specific technologies have emerged whereby plastics have enabled the definition of entirely new production systems in both terrestrial and aquatic agriculture, as well as in fisheries. An initial (and not exhaustive) taxonomy system for AP is proposed in Table 1 (based on Sundt et al., Reference Sundt2018; FAO, 2021; Briassoulis, Reference Briassoulis2023).

Table 1. Draft nomenclature and classification system for main uses of plastics in agriculture

The deployment of AP in terrestrial agriculture is now expanding beyond common ancillary uses (such as for containers of seeds, crop and agrochemicals) to new materials and components at the base of entirely new and highly efficient production systems. In particular, in the context of protected cultivation systems, the use of plastic covering films, micro-irrigation systems and protection nets is in expansion in both developed (e.g., APE Europe, 2024) and developing (e.g., NCPAH, 2022) countries. These components can help to achieve a cost-effective control over environmental factors, including soil properties, pest control, water and agrochemical usage and runoff, protection from extreme weather, control over solar radiation and reduced soil erosion (Kader et al., Reference Kader2017; Briassoulis, Reference Briassoulis2023). This has resulted in an expansion of the production of several important crops beyond their traditional geographical or temporal boundaries, also providing farmers with the opportunity to link to new and broader markets (FAO, 2021).

Plastic usage in most fisheries and aquaculture has also brought about several benefits. Plastic has been a core commodity for the manufacturing of gears owing to the low cost, flexible manufacturing, high resistance and light weight. Plastic is used for the manufacturing of nets and other fishing gear, including cages, buoys, ropes and floaters, among others. Boxes and packaging material made of plastic are used for the transportation, conservation and distribution of fish products. The use of plastic in these applications reduces logistical and maintenance costs and extends the lifespan of essential tools, ultimately leading to increased yields and economic gains.

International policy documents (e.g., EEA, 2019) have listed precision farming, organic farming and agroecology as the production strategies that will enable sustainable and resilient agriculture with a reduced environmental footprint and the capacity of facing the negative effects of climate change. According to the narrative of some actors operating along the plastic supply chain (APE Europe, 2021), AP is indicated as key to endorse these strategies.

Agriplastics composition and their environmental performance

The most important polymeric compositions of AP are low-density polyethylene, linear low-density polyethylene, polypropylene and, to a lower extent, ethylene vinyl acetate, high-density polyethylene (HDPE), polycarbonate, polymethyl methacrylate, glass-reinforced polyester and polyvinyl chloride. Beyond composition, the characteristics and durability of a product depends on its geometrical properties (e.g., the thickness of a plastic film or the section of a fishing line or net line), use of chemical additives in the formulation, climate (mainly related to exposure to solar UV radiation) and management. Resistance to mechanical stress and ageing is key for reducing the chance of pollution. For instance, mechanical stress during deployment or collection of conventional mulching films or other thin or excessively degraded agricultural films can result in losses typically of up to 30% of the total recoverable volume (EUNOMIA, 2021). Degradation and embrittlement during use, disposal or as the result of mismanagement are critical for pollution generation, along with practices in which plastic is abandoned or deliberately disposed in the environment. Early signs of degradation include discoloration, surface cracking and brittleness. These signs typically occur before the material reaches rupture and fragmentation. For example, covering films in protected cultivation systems progressively lose their mechanical and radiometric properties due to their limited thickness, their prolonged exposure to UV solar radiation, interaction with chemical pesticides, wind and hailstorms and variations in air temperature and relative humidity (Schettini et al., Reference Schettini and Vox2014). Similar considerations also apply for plastics used in fishery and fish farming; in this case, other aspects, such as biofouling, can play a substantial role in determining the durability of the materials. Understanding the useful operational lifespan of given AP is key for sound management and for avoiding pollution.

Chemical additives in AP formulations are important factors influencing environmental performance. Some substances used as plastic additives have been indicated as harmful for the environment and human health (Wang et al., Reference Wang2013; Blaesing and Amelung, Reference Blaesing and Amelung2018; Hahladakis et al., Reference Hahladakis2018; Wiesinger et al., Reference Wiesinger, Wang and Hellweg2021) and data on ecological and human toxicity of many of the several thousand chemicals used in different plastic products are not currently available (Hahladakis et al., Reference Hahladakis2018). Open literature sources reporting information on chemical additives in AP formulations are absent due to intellectual property protection aspects.

Beyond representing an environmental concern, lack of disclosure on chemical composition has implications for impact life cycle assessments and recyclability (Carney Almroth and Slunge, Reference Carney Almroth and Slunge2022; Geueke et al., Reference Geueke2023). Because several APs are used in outdoor settings, chemicals that can delay UV-induced photooxidative processes are commonly used. These include UV absorbers (converting high-frequency radiation into thermal energy) and UV stabilisers (preventing free radicals’ formation or acting as scavengers for free radicals). Beyond photo-stabilisers and filters, chemical additives are typically used as process aids for the manufacture of products or to achieve other desired optical or mechanical properties.

Growing awareness on the environmental impacts of plastic debris sourced by agricultural practices, as well as the accumulation and the problematic management of large quantity of generated waste, has prompted advances in the use of polymeric materials which can degrade in the environment and/or in composting facilities. While degradable plastic includes a heterogenous family of materials, they have generically been presented by manufacturers as more environmentally friendly options in the context of reducing or even zeroing waste generation, while (in the case of materials generated from biomasses) bolstering the circularity of organic waste. Biodegradable or compostable plastics represent a minority, yet expanding, share of the AP market, especially in the area of protected cultivation systems in terrestrial agriculture (e.g., mulching films). Biodegradable (in soil and/or composting facilities) polymers used in AP applications include polylactic acid (PLA), sometimes used in blends with fossil-based (recently also bio-based) polybutylene adipate terephthalate (PBAT), and blends or composites of PBAT with natural materials like starch or cellulose. Other biodegradable polymers common in agricultural applications are polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) and polycaprolactone. Beyond mulching films, biodegradable plastics are used for seed coatings and the formulation of slow-release agrochemicals – which can utilise a broader range of polymers – as well as compostable (e.g., PLA-based) binders and clips (Briassoulis, Reference Briassoulis2023).

The use of biodegradable plastics has also been indicated as an alternative to conventional polymers for fishing and fish farming gears (or specific parts of these products), to possibly mitigate the impacts of abandoned, lost or discharged fishing gears. These uses are, however, still at the development stage (INdIGO, 2024).

Material degradability can be achieved considering non-biological processes. For example, similar to biodegradable mulching films, oxo-degradable materials (especially mulching films) were also introduced to overcome EoL costs. These materials are typically produced from conventional polyolefins with the addition of pro-oxidant compounds such as transition metal salts (such as iron, cobalt or manganese salts). These additives catalyse the oxidation of the polymer chains when the plastic is exposed to radiation and heat, for example, during use. This process weakens the polymer structure and makes it more susceptible to fragmentation. At the end of their useful operational time, these materials rapidly disintegrate into small particles which accumulate in soil (Yang et al., Reference Yang2022).

Whether produced from fossil C or from biomass, the use of degradable plastics in agriculture results in the addition of compounds from chemical syntheses (including polymers, monomers and chemical additives present in the formulation) to the environment. This has raised concerns among environmental scientists and environmental organisations about possible ecological impacts. In some countries, there has been an effort to establish industrial and regulatory standards aimed at reducing the risks of adverse effects on ecosystem health or compost quality. These standards typically set the requirements for the material degradation rate under laboratory conditions and indicate the limits for the typology and amounts of the chemical additives used in the formulation. Some standards also introduce requirements for basic eco-toxicological testing. For example, the ASTM D6400 standard by the American Society for Testing and Materials specifies the requirements for compostable plastics, and it includes criteria for biodegradation in soil environments. The European standard EN 17033 defines requirements for biodegradable in soil mulch films and includes criteria for biodegradation in soil, basic ecotoxicity and thresholds or limitations for heavy metals and other toxic or persistent substances. Finally, the EN 13432 focuses on requirements for packaging recoverable through composting and biodegradation to enable circular use of digestates, which may then be used in agriculture as soil amendments.

Environmental concerns of agriplastics

Sources, drivers and fate of pollution from agricultural plastics

Plastics used in agriculture represent a driver of pollution across local, regional and global scales. Fisheries have been directly pointed as important contributors to marine plastic litter: industrial trawls, purse-seine and pelagic longline fisheries have been estimated to utilise 2.1 Mt. of plastic. Accidents leading to the loss of these gears generate between 28 and 99 kt/year of marine debris (Kuczenski et al., Reference Kuczenski2022). These estimates exclude abandoned and intentionally discarded gear at sea. A metadata analysis from 2019 indicated that 5.7% of all fishing nets, 8.6% of all traps and 29% of all lines are lost around the world each year, indicating total losses to be in the range of several hundred kilotonnes (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Hardesty and Wilcox2019).

Fish farming activities also represent a source of marine debris and microplastics. Global-scale emission inventories from these sectors are not available, nor accurate global figures of the plastic demand by aquaculture. Several studies have, however, provided estimates of plastic pollution emission from fish farming activities at the local or regional level. For example, annual emissions of plastic debris from floating oyster farms in Asia have been estimated in the order of 100 g/m2 of the farm area (Tian et al., Reference Tian2022). Similarly, a study conducted in the Atlantic coast of France evidenced that 70% of the plastics collected from beaches were characteristic of aquaculture materials (Bringer et al., Reference Bringer2021).

The sound management of large volumes of APW is a critical issue for most types of modern farms (Skirtun et al., Reference Skirtun2022; Briassoulis, Reference Briassoulis2023) that have to deal with poorly recyclable waste, inadequate infrastructures for waste storage and segregation at farm level, and lack of waste collection and management schemes. APW can be heavily contaminated by foreign materials (e.g., sand, soil, organic matter, biofouling and possibly by veterinary drugs, chemicals, pesticide residues and fertilisers), which represents an obstacle for recycling. Mismanagement and illegal practices such as the dumping of APW, abandoning or discharging fishing or aquaculture gears at sea, the burial of waste in the farm soil or open burning are unfortunately common phenomena (Briassoulis et al., Reference Briassoulis2013; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Hardesty and Wilcox2019).

The negative consequences of the improper disposal of APW in fields and landfills include (i) aesthetic pollution and deterioration of the landscape and its social and economic value, (ii) threats to domestic and wild animals, (iii) blocking of water flow through drainage pipes and channels and (iv) overload of landfills with an immediate environmental and economic impact. Burying APW in fields induces degradation of soil quality and irreversible soil contamination. The uncontrolled burning of APW will release harmful airborne toxic substances and semi-combusted plastic particles and other types of dusts. These emission can be a source of hazardous substances (Velis and Cook, Reference Velis and Cook2021).

Some farming practices can also intentionally introduce plastic debris to the farm environment and beyond (Ng et al., Reference Ng2018). For example, oxo-degradable and very thin mulching films were introduced to overcome the problems and costs associated with post-use handling of plastic-based mulching, as these materials can be intentionally left to physically degrade in the field (Yang et al., Reference Yang2022). Oxo-degradable mulching films have been banned in some countries (EU, 2019), but they are still an available option for agriculture in many regions. Similarly, thin-film mulching with no post-use recovery has been a common practice in some countries, leading to cases of extreme soil contamination (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu2022). China, for example, has recently introduced regulations that require farmers to collect and recycle mulching film (Li et al., Reference Li2021d).

Biodegradable in soil plastics (used mostly for the production of mulching films, seed and agrochemical coatings and plant clips) also represent an option for overcoming waste management costs. Following complete degradation in soil, mulching films are converted to carbon dioxide and microbial biomass preventing the irreversible accumulation of plastic debris in soils, composts or other environments (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Lee and Lee2023c). This occurs at a relatively low rate (e.g., the specification for degradability in soils typically require a period of 2 years for the complete degradation under laboratory conditions), leading to a temporary and reversible accumulation of plastic debris (including microplastics) in soil. If application rates are higher than the rate of degradation (which is a typical situation), relatively high amounts of these debris can be present in soils on a regular base. This situation is accentuated in cold or dry climates, as these conditions can substantially slow down the degradation of plastics (Nizzetto et al., Reference Nizzetto2024).

Other AP applications resulting in intentionally sourcing microplastics to the environments include polymer-based controlled-release fertilisers, fertiliser additives, plant protection products using capsule suspension and seed coatings, especially when they are based on conventional plastics. In the context of European agricultural and horticultural sectors, these materials are listed among the activities resulting in the largest intentional releases of microplastics to the environment (ECHA, 2020).

While other sources can contribute plastic pollution to agricultural soils (Hurley and Nizzetto, Reference Hurley and Nizzetto2018), the relative importance of AP-related sources depends on the type of farm, agricultural practices and possible mismanagement.

Emerging insights and knowledge gaps on impacts of plastic pollution in terrestrial agricultural ecosystems

While the effects of plastic debris (including those deriving from fisheries and fish farming activities) and microplastic in marine environments are well documented in terms of impacts, the study of the source, exposure and effects of plastic pollution in terrestrial environments is a much more recent undertake. This section, therefore, is dedicated specifically to review the state of knowledge on risk posed by this pollution in terrestrial agroecosystems.

Recent scientific evidence has substantially increased the awareness on soils as major recipients of plastic pollution and on the impacts on soil properties and biota (Hurley and Nizzetto, Reference Hurley and Nizzetto2018; Z. Zhang et al., Reference Zhang2022b). Pollution of soils by residues of AP from terrestrial agriculture has already been confirmed in several studies across the globe (Chia et al., Reference Chia2022; H. Zhang et al., Reference Zhang2022a; Z. Zhang et al., Reference Zhang2022b). Typically, the highest levels of plastic residues in soils, globally, are reported for farmlands in China, where the majority of studies have focussed thus far, while a substantial paucity of observations exists for other parts of the world. In China, a high level of variability both within and across different locations has been observed (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu2022). Soil plastic pollution derived from AP tends to resemble the original material physically and chemically in several ways. For example, residues of thin films used in protected cultivation systems typically retain morphological characteristics of the film (e.g., the original film thickness). Microplastics left from polymeric encapsulation of controlled release fertilisers will resemble hollow plastic shells (Katsumi et al., Reference Katsumi2021) and residues from geotextiles may occur as individual fibres (Gustavsson et al., Reference Gustavsson2022).

The fate of AP residues once they enter a soil environment remains uncertain (R. Qi et al., Reference Qi2020a). For instance, two studies found, in one case, that >99% of particles were retained (Schell et al., Reference Schell2021) and, in another case, that >99% of particles were transported elsewhere (Crossman et al., Reference Crossman2020). Factors such as the particle characteristics (size, density and morphology), the properties of the soil (density, texture and moisture dynamics) and the context of the local environment (aspect and slope of the field, meteorological and climatic conditions and the activity of soil invertebrates) are all likely to play an important role. Soils and climatic conditions that facilitate export of particles may represent a pathway for contamination of water bodies (e.g., Katsumi et al., Reference Katsumi2021; Jiao et al., Reference Jiao2022), whilst soils that retain particles may accumulate these from successive inputs and be subject to progressively increasing stress and impacts (Hurley and Nizzetto, Reference Hurley and Nizzetto2018; Huang et al., Reference Huang2020).

Physicochemical properties of soils may be altered by the occurrence of plastic pollution, such as changes in soil pH (e.g. Boots et al., Reference Boots, Russell and Green2019; Y. Qi et al., Reference Qi2020b; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu2022), soil aggregation processes and aggregate size and stability (e.g., de Souza Machado et al., Reference de Souza Machado2019; Lozano et al., Reference Lozano2021), soil porosity (e.g., Jiang et al., Reference Jiang2017) and soil moisture dynamics, including hydraulic conductivity, water holding capacity and surface desiccation (e.g., Wan et al., Reference Wan2019; Y. Qi et al., Reference Qi2020b). Biological processes occurring in soils can also be affected by plastic pollution, including changes in the community structure, and functioning of soil microbial consortia and concomitant changes in soil enzyme activity or biogeochemical cycling (e.g., Y. Huang et al., Reference Huang2019b; Fei et al., Reference Fei2020; Rong et al., Reference Rong2021). Many of these effects are likely to mediate other changes, such as altered availability of nutrients or altered sorption processes or cation exchange capacity caused by changes in soil pH and microbial functioning (e.g., Y. Qi et al., Reference Qi2020b; Rong et al., Reference Rong2021).

Animals living in the soil also interact with and are affected by AP residues. Ecotoxicological studies have reported changes in the number of individuals, feeding behaviour, reproduction, growth and mortality (Li et al., Reference Li, Song and Cai2020; Wei et al., Reference Wei2022). Small plastic particles can affect soil fauna by adhering to them, potentially causing surface damage, or altering their movement, or as a result of ingestion, where particles may cause internal blockages or impart direct toxicity (Chang et al., Reference Chang2022). In many cases, soil fauna that ingest AP residues may also be effective in excreting these particles, causing minimal to no damage (Büks et al., Reference Büks, Loes van Schaik and Kaupenjohann2020). However, toxicological responses described in the literature include histopathological damage, oxidative stress, DNA damage and metabolic disorders (e.g., Rodriguez-Seijo et al., Reference Rodriguez-Seijo2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen2020; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng2020).

Plants may also be affected by the presence of small plastic particles in soils (Zantis et al., Reference Zantis2023). This includes changes in seed germination, the growth of roots and shoots and the total plant biomass (e.g., Boots et al., Reference Boots, Russell and Green2019; Gong et al., Reference Gong2021; Lozano et al., Reference Lozano2021; Li et al., Reference Li and Huang2021a). Measurements of biomolecular stress indicators reveal differences related to exposure to micro- or nanoplastics (Zantis et al., Reference Zantis2023). This includes impacts such as oxidative stress (e.g., Wu et al., Reference Wu2021; Li et al., Reference Li and Wang2021b) and changes in antioxidant enzyme activity (e.g., Jiang et al., Reference Jiang2019), photosynthetic efficiency (e.g., Gao et al., Reference Gao, Liu and Song2019) and plant metabolism (e.g., Wu et al., Reference Wu2021; Li et al., Reference Li and Wang2021b). These changes may be caused by the potential uptake of very small plastic particles or physical implications of the presence of larger particles, such as blocking of seed pores, roots or hindering the uptake of water or nutrients (Zantis et al., Reference Zantis2023). In addition, small plastic particles may alter plant production and quality through indirect effects, such as the different potential alterations to the soil environment discussed above. Whilst several studies report negative effects, some studies that investigate the impact of micro- and nanoplastics on plant production or quality identify both positive or negligible changes in a wide array of different endpoints (Zantis et al., Reference Zantis2023).

Despite a growing body of research, it remains difficult to conclude on safety thresholds quantitatively defining the risk posed of plastic pollution on soils. Remarkably, an initial appraisal focused on comparing metadata across studies on both occurrence of plastic pollution in soils and the levels observed to cause negative impacts on soil properties and plants, shows an overlap (Qiu et al., Reference Qiu2022), suggesting that several agricultural soils might already be within the risk zone for experiencing the negative effects of plastic pollution.

Knowledge gaps on agriplastics from a multi-actor perspective

The design, production, use and EoL management of APs are shaped by, and co-produce, a complex socio-political landscape. Policy drivers in this field branch into concerns over climate change, biodiversity loss, food security, human health and economic development. As such, multiple actors and interests are involved and will be impacted in different ways by future changes in the regulatory landscape. It is therefore important to understand the experiences, concerns and interests of the implicated stakeholders. Understanding the underlying needs and motivations of AP users and the knowledge and technology gaps identified by policy practitioners, industry and organisations promoting environmental and/or food security concerns are essential to guide research and develop effective regulation.

Based on an initial scoping exercise in the EU, conducted through the PAPILLONS research project (PAPILLONS, 2024), four grouped stakeholder perspectives were set forth. These perspectives have been co-developed by the authors and European stakeholder organisations following a series of bilateral meeting and multi-stakeholder fora (PAPILLONS/MINAGRIS, 2024). Furthermore, to address a global scope, we gathered and compiled the inputs of 68 international experts (with geographic competence covering both high-income and low-income countries) via an online qualitative exploratory survey – the International Survey on Agricultural Plastics’ Perspectives and Knowledge Gaps – using the International Knowledge Hub Against Plastic Pollution (IKHAPP) platform (IKHAPP, 2024) and in some cases by interaction through email. This approach does not pursue statistical representativeness of the results but aimed at collecting comprehensive views from the experts. The survey was co-designed by scientists and experts associated with the PAPILLONS research project and administered by IKHAPP from 19 May to 9 June 2023. The survey responses were analysed by thematic coding of the data. Two matrices were built – that is, the knowledge gaps matrix – from a multi-actor perspective which distinguishes between five gaps categories concerning: science, policy and governance, management, innovation, sustainable products and practices, as well as human health and landscape value (see Table 2), and the actions matrix – which differentiates between three actions categories, namely (1) lay the foundation of sustainable management of agricultural plastics, (2) strengthen demand for sustainable products and practices and (3) unlock the innovation potential (see Table 3).

Table 2. Knowledge gaps – multi-actor perspectives

Table 3. Actions – multi-actor perspectives

As a result, the perspectives provided by stakeholders working in the European agricultural value chain were fine-tuned with the survey results (see Supplementary Appendix 1 – Anonymized Survey results) as well as evidence gathered via desktop research.

Perspectives from farmers

For farmers, there are a variety of shared motivations and concerns defining the choice of production practices, with the primary being increasing yield and reliability of production in an efficient manner. In addition to this, many farmers are motivated by concerns for cultural heritage and local food products (Daugstad et al., Reference Daugstad, Rønningen and Skar2006; Tekken et al., Reference Tekken2017), cultural landscapes (Akagawa and Sirisrisak, Reference Akagawa and Sirisrisak2008; Murillo-López et al., Reference Murillo-López, Castro and Feijoo-Martínez2022), animal welfare and human–animal relations (e.g., Skarstad and Borgen, Reference Skarstad and Borgen2007; Lien, Reference Lien2015) and economic profits (e.g., Cary and Wilkinson, Reference Cary and Wilkinson1997). These drivers are obviously also at play concerning whether and how farmers acquire and use AP and adopt various forms of EoL management.

Through the online survey, inputs from farmers, agricultural business representatives and farmer union representatives were collected. Five of these were based in Europe, two in Latin America and one in Africa. All highlighted the benefits of plastics for preserving food quality and enhancing productivity, but shared concerns on the increasing amounts of APW and lack of proper waste management infrastructures. This aligns with the broader literature on plastic waste management, where the current infrastructures across the world are unable to effectively handle accumulated plastic waste (UNEP, 2015). While it often appears as a more pressing issue in the Global South and economies with high growth rates, persistent inequalities exists in global waste trade as unprofitable plastic waste with materials with low recyclability have been often exported to countries with less strict waste management regulations (e.g., C. Wang et al., Reference Wang2019a; Havas et al., Reference Havas, Falk-Andersson and Deshpande2022). This illustrates the global character of plastic waste management in spite of international convention tending to limit the phenomenon.

Farmer representatives in the survey called for publicly available and intelligible research data on the long-term effects of plastic use on soils, the natural environment and farm productivity. They also advocate for more collaborative dialogue and for incorporating stakeholder knowledge for effective policy development, favouring measures that move at least part of the costs for waste collection and management away from them.

As outlined in section ‘Types and benefits of Agriplastics for different agricultural sectors’, the many advantages of AP are appealing for farm efficiency. Initial scoping interviews from Norway raise the concern on soil health and microplastic to the agenda, as farmers are increasingly becoming aware of the impacts of microplastics (or microplastics in combination with toxins/chemical additives) on soil health. While all interviewed Norwegian farmers who used biodegradable mulching film felt it was a necessity for agricultural efficiency and reduction of pesticide use, they expressed concerns over increasing microplastics contents and chemical contaminants in soil. The farmers requested more research into soil and plant health impacts, as well as trustworthy, neutral and accessible information about farm inputs and products like mulching film.

Beyond efficiency and food safety, many decisions and management practices on a farm are done with consideration for the welfare and sustainability of the environment. Farmers are intricately tied to their natural surrounding and environment, and many develop a grounded and embodied relation with their land, soil, plants and animals. APs can be used to protect the environment from other harms. As an example, concerns over the environmental impact of waste from commercial fish farming and disease control and fish welfare have led to innovations in closed containment systems, like the Marine Donut built in HDPE (Marine Donut – Floating Closed Containment System, n.d.).

Based on the authors’ interactions with producers and farmer organisations across Europe, a general and increasing awareness about the problems of APW accumulation and the potential for soil pollution by plastics was noted. For farmers and rural producers, two main challenges are emerging: optimisation/minimisation of plastic use and the recycling of used agricultural plastic. A survey conducted between July and October 2020 in Ireland, highlighted that over 85% of farmers fear the consequences regarding the amount of plastic waste generated by farming activities (King et al., Reference King2023).

The European Union has proposed a series of measures that may minimise plastic usage at the farm level such as (i) have farm inputs delivered in bulk to avoid plastic packaging, (ii) adopt agricultural techniques that do not use plastic (e.g., alternative hay storage system in cattle production) and (iii) reuse the plastic on the farm (EIP-Agri, 2024). According to the narratives collected by the authors from European farmer organisations, a one-size-fits-all solution cannot be considered, as there are varying opportunities and constrains to be considered based on environmental conditions, farm size, production type and practice and existing infrastructure and technology, as well as available finances, knowledge and labour. Across the European Union, farmers’ associations are addressing the question of how to improve APW management (EIP-Agri, 2024). A field study in Almeria, Spain, proved a direct relationship between the price of the raw materials needed to produce plastic and the volume of recycled plastics. Overall, recycling post-consumer plastic products is costly and time-consuming for farmers; therefore, to incentivise best practices for waste management, it is necessary to facilitate and harmonise the EoL management of APW (Castillo-Díaz et al., Reference Castillo-Díaz2021).

Perspectives from industry and industry associations

The industry perspective summarised here is sourced by 16 respondents from the digital survey. These were representatives from plastic industries, fertiliser and agrochemical manufacturers, waste managers specialised in APW and industry associations, as well as compost and biogas manufacturer associations. Among them, four have global operations, six are based and operate in the European Union, two are from North America, two have operations in South America and two are from Asia and Australia. These data are complemented by a detailed synthesis provided by Agricultural Plastics Environment (APE) Europe on the European AP industry position and perspective.

Respondents have generally highlighted that industries are key stakeholders in the current and future design, promotion and management of AP and plastic alternatives, including in the context of addressing solution to prevent pollution and waste accumulation. They underscore that the technical competence, capacity for innovation and access to capital are key for moving towards a more sustainable use and management of AP and APW, including through the design of circular solutions.

For APE Europe, AP only represent part of the climate and environmental impacts of agricultural activities. They highlight how for a small investment in plastic, farmers may reduce the input of pesticides or fertiliser and the use of energy and water, while simultaneously increasing the quality and quantity of the farmed product. Thus, APE Europe calls for a holistic understanding of the environmental consequences associated with possible changes in agricultural practices, like reducing the use of AP or using plastic alternatives. This perspective resonates with the responses collected through the survey, where 16 of the respondents were classified as belonging to the plastic industry and industry associations promoting the use of AP.Footnote 1 The respondents identify the unique quality of AP to preserve food quality and safety, provide durable and water-proof packaging for inputs and push climatic and environmental boundaries for agricultural production.

The respondents’ views show a level of variability regarding whether AP can produce detrimental consequences for the environments, soil health and human health. Some considered AP to have little or low negative consequences as long as they are handled correctly, whereas some respondents were concerned with potential toxic leakages from plastic products, and with microplastics found in human bodies and the environment. Overall, the respondents called for more research on the quantities and fates of plastic in soil and agricultural environments. In addition to this, bio-based and biodegradable products are mentioned by the survey respondents, with some considering them as a potential sustainable substitution for conventional AP, while others called for more research into their possible contribution to microplastic accumulation in soil and potential increase in CO2 emissions as the plastic degrades.

Across the survey responses, and aligning with APE Europe’s views, proper management of APW remains a key priority. The industry is aware of the problems caused by dumping or burning of AP and do not wish to be associated with these practices. Thus, some explicitly call for improved waste management schemes possibly involving all economics actors of the AP value chain. In particular, based on experiences across different European countries, APE Europe calls for an integrated approach, where producers commit to develop AP designs that ease recycling and minimise pollution, and where the producers take responsibility for regenerating polymer granules from waste and using them in new products. They highlight the important role traders and trade cooperatives have in disseminating good practices to AP users.

Technical and economic efficiency is important for proper EoL management of AP. EoL management is costly, and often APW has a negative value (according to APE). Instead, national collection schemes in Europe are often financed following the extended producer responsibility (EPR) principle, by adding a levy to the selling price to cover EoL management cost. In the survey results, the industry respondents are positive towards increased recycling requirements and encourage governments to develop policy and measures that promote proper EoL management and increase the use of recycled materials in AP products.

Finally, survey respondents in industry sector call for more research collaborations that should include AP users more directly. Collaborations may also be with waste management companies and product developers, to improve recycling technologies and the use of recycled material in AP products. As an example of such collaboration in research and development, APE Europe reports the results achieved from programmes such as RAFU, launched by A.D.I. VALOR and the French Committee for Plastics in Agriculture, to improve the recyclability of mulching films and develop safe biodegradable products (A.D.I.VALOR – Agriculteurs, Distributeurs, Industriels pour la VALORisation des déchets agricoles, n.d.. Similar programmes may provide grounded insights and cross-stakeholder understanding if launched in other agricultural and geographical regions. Finally, and beyond recycling, industry actors also call for research into plastic fate and impact on environments and human health, including research on biodegradable and bio-based products.

Perspectives from the environmental NGO sector

A total of six NGOs provided narratives and perspectives. Three of them are based in the European Union, one from the United States and two from Africa, covering topics such as broader plastic pollution, waste management and conservation. Organisations operating both at national and international levels were represented. In addition to the respondents to the online survey, the authors have collected information and perspectives directly from representatives of the Plastic Soup foundation and the Environmental Investigation Agency (IEA), an EU-based and a UK-based environmental NGO, respectively, both running strategic work on AP and APW at international and global levels. The NGO sector generally considers plastic-intensive agricultural practices as a threat to agriculture, the environment and human health, and advocates for the adoption of, or transition to, environmentally friendly and nature-based alternatives in farming. These should be endorsed by policy and instruments that include economic incentives. It was indicated that the costs of transition to environmentally sustainable practices should not be a burden towards specific groups of farmers but the result of a distributed effort, including at the international level.

In countries where AP-intensive production systems are already diffused, farming transitions to a lower plastic footprint will require sustainable production practices alternatives, effective recycling schemes and the certainty that institutional bodies and governments will support the process through tailor-made funds and programmes. There is an awareness that change will be costly and time-consuming, with possible short-term implications for both producers and consumers. These challenges affecting the transition must not be a reason for delayed action considering that the costs of inaction are currently not quantifiable. At the same time, a call for a better understanding of the environmental, agricultural, economic and human health costs of plastic pollution from the use of AP need to be prioritised by scientific research.

Moving away from AP-based practices may be particularly challenging for farmers in countries and regions where AP-intensive practices are at an initial development stage and in rapid expansion, typically substituting more traditional farming practices. These farmers need access to complete and objective information on the problem and costs concerning APW management and soil pollution in order to make informed decisions on how to orient investments in new production systems. NGOs can play a pivotal role considering their capacity in spreading awareness, mobilising resources and influencing policymakers to shape decision-making processes. The concerns and focus of environmental NGOs are shifting from the marine environment, where initial attention was placed by researchers on marine debris, to the broader plastic pollution problem including also on the use and misuse of plastics by the industry and consumers and accumulation of plastics in the food chain.

Within the European Union, the level of awareness on the challenges related to microplastics is growing steadily, in the wake of the announcement by the European Commission of the ambitious Farm to Fork strategy and EU Soil Strategy. Some NGOs called for EU institutions to leverage the discussion for the development of the EU ‘Soil Monitoring Law’ to contribute to the overall objective of reducing the amount of microplastic released into the environment by 30% by 2030. Despite the ambitious efforts of many of the EU initiatives, NGOs reacted negatively to the proposal on ‘Soils Monitoring and Resilience Directive’, calling for improvements and for more ambition to fully address the challenge at the EU level, including integrating in the proposal a list of key pollutants. The NGO sector has also questioned the effectiveness of several proposed substitutes for high-risk agricultural plastic products.

A first draft of the EU Soil Monitoring Law released in 2023 did not consider miroplastic pollution in soil. Following the dialogue and inputs provided by PAPILLONS project researchers with members of the environment committee of the EU parliament, a request of amendment to include soil plastic pollution in the law has been brought forward and assimilated in a new draft being currently negotiated.

The urgency for a strong political action towards plastic pollution has been highlighted during the Plastic Health Summit in 2023, where the Plastic Soup Foundation discussed the plastics treaty and re-stated that the short-term gains for farmers from agricultural plastics products do not outweigh the long-term consequences. This NGO has also provided a presentation on biodegradable polymers, which it has, according to them, been unproperly labelled as a one-size-fits-all solution. Biodegradable polymers are designed to be broken down by microorganisms, so they should not contribute to microplastic degradation. However, the NGO claims that the tests do not fully reflect all soil and environmental conditions in which these materials are used, claiming that test requirements from existing standards (e.g., degradation tests in an ‘ideal’ environment for microorganism activity and therefore biodegradation: at 25°C, in a humid and oxygen rich conditions and only on one soil type) (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang2020) are insufficient to guarantee full degradation in real operation conditions, resulting in the accumulation of plastic debris in the environment.

The EIA, a UK-based advocacy organisation, has been working on AP since 2018, especially in the context of EU and UK supply chains. As part of their work, they documented diffuse cases of APW mismanagement including illegal waste handling practices that highlights farmer challenges in sustainably using AP and the serious environmental impact this can produce. Concerns about EoL management has also been expressed by several respondents to the digital survey that called for a better understanding of the AP life cycle and the waste management process in agriculture, including in both developed and developing countries. The proposals for actions are to improve the formal record keeping of AP use, by environmentally sound management of waste. Overseas and African NGOs have prioritised investments in research and innovation with the aim to improve both technologies for sustainable use and EoL practices and develop new management tools.

Awareness and understanding of plastic pollution impacts on the environment and food security need to be urgently reinforced. Ambiguity on this aspect is reflected by the uncertainty and scepticism surrounding the effectiveness and rapid implementation of policy strategies aiming at zero-plastic pollution to date. The NGO sector advocates for enhanced traceability and transparency for the EoL management of agricultural plastics (e.g., by means of digital tracking technologies, and mandatory reporting of AP volume sales and processed APW), as well as for the development of new waste management models and compact/cost-effective technologies for recycling and reuse, specifically tailored for the agricultural sector which could be deployed locally or even at the farm level. Raising awareness and inducing behavioural changes among farmers are also seen as necessary measures to improve assimilation of plastic pollution reduction measures. Finally, NGOs remark that, internationally, policymakers should define plastic reduction targets for the agricultural sector, and at the same time provide complete and assimilable (by farmers) assessments of the economic viability and cost-effectiveness of sustainable alternatives to AP.

The environmental scientists’ perspective

The research community has focused on investigating both the sources (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Lee and Cha2023a) and potential effects of plastic debris including micro- and nanoplastics on aquatic and terrestrial environments (Chia et al., Reference Chia2021). While historically the research focus has been on marine pollution, in recent years, research has provided evidence that plastic pollution in terrestrial environments (and especially agricultural soils) is an environmental concern capable of affecting ecosystem quality, including soil fertility and agricultural performance. This section reports the perspectives of the environmental science community regarding knowledge gaps and priorities for future regulation. This synthesis reflects responses from researchers participating in the IKHAPP survey as well as the positions of a group of environmental scientists from 37 research institutes in Europe and China, including ecologists and toxicologists clustered around two large international research projects (PAPILLONS/MINAGRIS, 2024), as well as the insights from recent scientific literature (Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann2023) and policy briefs (The Scientists Coalition for an Effective Plastic Treaty, 2024).

The ongoing debate has highlighted several knowledge gaps that the research community should urgently address to inform environmental and agricultural policies and ensure sustainable agricultural practices. A first major knowledge gap is represented by the paucity of data on the amounts of plastics that are intentionally or unintentionally introduced into agricultural soils through practices such as the application of compost products or biosolids that may be enriched with microplastics or irrigation from plastic contaminated surface waters, as well as the use and waste handling of AP products. Such an assessment should be quantitative and global in scope, enabling a comparison between different sources, which can help to prioritise pollution reduction measures. A concerted effort to consolidate confidence in assessments of spatial distribution of microplastic plastic pollution in agricultural soil is therefore necessary.

Researchers have also highlighted that insufficient empirical studies exist focusing on the long-term effects of the accumulation of debris from the fragmentation of APs on soil health, soil biodiversity and related soil ecosystem services under different soil conditions (e.g., temperature and moisture) and soil types (Baho et al., Reference Baho, Bundschuh and Futter2021). Scientific works have emerged during the last 3 years documenting interactions between soil microbiomes and soil fauna and micro- and nanoplastic pollution (Huerta Lwanga et al., Reference Huerta Lwanga2016, Reference Huerta Lwanga2017; de Souza Machado et al., Reference de Souza Machado2018, Reference de Souza Machado2019; Liu et al., Reference Liu2019; Wan et al., Reference Wan2019; Fei et al., Reference Fei2020; Selonen et al., Reference Selonen2020; R. Qi et al., Reference Qi2020a; Baho et al., Reference Baho, Bundschuh and Futter2021; Ya et al., Reference Ya2021), highlighting adverse effects on the viability of organisms and important ecological functions at environmentally plausible levels of contamination in soils (de Souza Machado et al., Reference de Souza Machado2018; Selonen et al., Reference Selonen2020). Despite this, actual risk assessment approaches lack an accurate framing of exposure scenarios (especially in terms of the typology, characteristics and representativeness of the particles used as test materials) and tend not to take chronic risks (such as effects on biodiversity and soil fertility) into adequate consideration. This concern is applicable to both conventional and bio-based or biodegradable plastics. According to environmental scientists, assessments of the long-term effects resulting from the use of biodegradable polymer as alternatives in AP applications (e.g., biodegradable mulching films) lack sufficient characterisation (Kapanen et al., Reference Kapanen2008; Ardission et al., Reference Ardission, Tosin, Barbale and Degli-Innocenti2014; Martin-Closas et al., Reference Martin-Closas, Botet and Pelacho2014; Bandopadhyay et al., Reference Bandopadhyay2018, Reference Bandopadhyay, Sintim and DeBruyn2020; Serrano-Ruíz et al., Reference Serrano-Ruíz, Martín-Closas and Pelacho2018; Sintim et al., Reference Sintim2019; F. Huang et al., Reference Huang2019a; Balestri et al., Reference Balestri2020; Campani et al., Reference Campani2020; Iqbal et al., Reference Iqbal2020; Magni et al., Reference Magni2020; Schöpfer et al., Reference Schöpfer2020; Souza et al., Reference Souza2020; Zimmermann et al., Reference Zimmermann2020; Chen et al., Reference Chen2021; de Souza et al., Reference de Souza2021; Ding et al., Reference Ding2021; Serrano-Ruiz et al., Reference Serrano-Ruiz, Martin-Closas and Pelacho2021; Mazzon et al., Reference Mazzon2022), while the requirements for biodegradability and environmental safety introduced by current standards are not adequate to fully ensure safe and controlled application in all bioregions and climates. Technical assessments of biodegradation are conducted under standard laboratory conditions – a scenario that is not relevant for many locations.

Furthermore, the transport of macro-, micro-, or nanoplastics by wind, water and bioturbation may transfer fragments of biodegradable and conventional AP from the fields in which they are applied to other areas, where conditions may be inadequate to achieve rapid biodegradation for biodegradable AP and no degradation for conventional AP such as aquatic environments (Tsuji and Suzuyoshi, Reference Tsuji and Suzuyoshi2002; Li et al., Reference Li2014a; Lambert and Wagner, Reference Lambert and Wagner2017; Sashiwa et al., Reference Sashiwa2018; Dilkes-Hoffman et al., Reference Dilkes-Hoffman2019; Nakayama et al., Reference Nakayama, Yamano and Kawasaki2019; X.-W. Wang et al., Reference Wang2019b; Chamas et al., Reference Chamas2020; Anunciado et al., Reference Anunciado, Hayes, Wadsworth, English, Shaeffer, Sintim and Flury2021). No data on biodegradability in sediments or water (e.g., ground and surface waters) are required for certification in some parts of the world.

The lack of accessible data on the composition and long-term effects of chemical plastic additives used in AP products represents a serious concern for environmental scientists, as chemical additives in plastic may represent a conspicuous fraction of the total mass of the products both for conventional and biobased/degradable materials (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Lee and Cha2023b). Environmental scientists argue that the current fragmentary knowledge on the use and degradation/ageing of AP can result in an incorrect estimation of the ecological risks posed by these chemicals.

Uptake of micro- and nanoplastics by crops and their accumulation in the terrestrial food chain has been proven in recent studies (Bosker et al., Reference Bosker2019; Sun et al., Reference Sun2020, Reference Sun2021; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou2021; Li et al., Reference Li2021c; Lian et al., Reference Lian2022; Zantis et al., Reference Zantis2023). Still, the risk for human health by such uptake processes has not been studied and remains unknown. The associated risk for consumers should be quantified and considered within future risk assessments before AP-based practices that can cause pollution are incentivised. This should also consider indirect, knock on and systemic-level effects, resulting in, for example, reduced soil fertility and agricultural yields and, therefore, risks to global food security, in addition to any direct toxic effects.

Similarly, still limited knowledge about the interaction of APs with other organic pollutants intentionally (e.g., pesticides) or unintentionally (e.g., veterinary drugs) released in agricultural soils (Hüffer et al., Reference Hüffer2019; Dolar et al., Reference Dolar2021; Sun et al., Reference Sun2021; Varg et al., Reference Varg2021; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang2021; Li et al., Reference Li2021c; Hanslik et al., Reference Hanslik2022; Lajmanovich et al., Reference Lajmanovich2022; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou2022). Pesticides and veterinary drugs are regularly present in agricultural soils and are expected to interact with both conventional and biodegradable plastics. Studies on the transport of plastic residues with adsorbed pesticides and the related risks for environmental and human health are limited.

Acknowledging the available body of evidences and the existing knowledge gaps the environmental research community remarks that soil and sediment pollution by non-degradable micro- and nanoplastics is poorly reversible (Chia et al., Reference Chia, Lee and Cha2023b), while soil is a non-renewable resource. Food production practices that result in continuous releases of plastic debris and their chemical additives, however small, should be critically evaluated and disincentivised. In the context of agricultural practices that cause soil plastic pollution, policy should take into consideration the ecological, agricultural and potential human health risks posed by an underlying increase in soil and water body pollution and the potential transfer of plastic debris or their chemical additives into food over the medium and long term. Hence, scientists recommend that policy developments incorporate the definition of sustainability criteria that holistically consider long-term impacts of this pollution in natural and agricultural environments.

The use of degradable, biodegradable or compostable plastics as alternative materials should follow strict criteria related to safety and sustainability by design. The use of any materials that do not achieve complete degradation should be prevented. A revision of the current standards for certifying biodegradability is needed, particularly regarding their suitability to represent the range of environmental conditions in which biodegradable AP are (and will be) used. The sustainability of long-term continuous use of biodegradable AP should be considered. Scientists have highlighted the importance for authorising the use of biodegradable and compostable plastics under a regulatory frame based on risk assessment and management (PAPILLONS, 2022).

The definition of a risk assessment system regulating the use of AP (both conventional and biodegradable) that release plastic debris and associated chemical additives to soil or crops should be considered by regulation. This could, for example, be framed under the risk assessment frame in a similar way as is done for chemical management regulation (e.g., The European Union Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemicals, the EU Pesticide regulation and others). Concerning aspects related to use and management of APs, environmental scientists advocate for regulations that demand the creation and maintenance of inventories of AP use (of both conventional and biodegradable plastics) and management across the entire life cycle as a tool to enable control over the potential sources of pollution and agricultural plastic generation. This includes the need for form of open or targeted disclosure concerning additives used in AP, solid and clear labelling schemes describing composition, usage and waste management practices and labelling/licencing schemes that can help ensuring best practices and traceability of the materials throughput their life cycle.

Industry and/or retailers should be actively involved in the maintenance of these records at the national or subnational level. Tracking the usage of different AP regulation should impose that conventional plastic products must be removed from fields and disposed properly before excessive ageing and weathering may induce fragmentation and result in pollution. It is possible to predict the useful lifetime of a given material based on factors such as the climate of the area or the cultivation techniques employed, as well as the material properties of the AP product. Farmers must not use the plastic products beyond that time. Technologies to maintain a detailed census of AP in use and track their deployment time are available (e.g., microchips, barcodes and integrated databases). In addition, instruments to promote mechanisms for a widespread system of collection, storage, management and recycling of AP waste should be urgently introduced to avoid further additions of plastic pollution to soils. EPR schemes could form part of this initiative. At the same time, regulation should disincentivise international trade of AP waste unless there is a verified guarantee that the recipient countries are capable of effectively processing these materials through the formal economy sector with due safeguarding of labour and environmental standards. Closing the loop of the AP life cycle within small geographic units will be necessary to promote circularity, control and economic sustainability of waste management and, possibly, recycling. While redesigning, recovering, reusing and recycling are all important steps to improve sustainability of AP-based practices, regulation should also take into consideration the options of reducing and preventing such practices. For example, policy should design instruments whereby plasticulture should be endorsed in a given area only when the social and environmental benefits (and not only the economic benefits) exceed the social and environmental costs, whereby this assessment should take into consideration not only the long-term ecological and agricultural impacts of soil plastic pollution caused by the practices but also the impact on the quality of life and landscape value of the area (PAPILLONS and MINAGRIS, 2022).

Aspects linked to the resilience of food systems should be considered when designing policies for AP. Plastic is mostly manufactured from non-renewable raw materials. Agriculture heavily relying on AP is therefore inherently non-sustainable on the long term unless full circularity is achieved in the sector. In addition, the price of fossil fuels is highly volatile, and this can have implications on the cost-effectiveness of AP-based production systems, with possible implications for food security. This aspect counterbalances some of the benefits on improved production efficiency enabled by AP. Accordingly, while the benefits and usefulness of AP are not questioned, policy incentives should somehow also benefit, in each agricultural region, group of farmers that minimise plastic use in their activities or, more in general, that minimise chemical inputs in their production systems while embracing nature-based solution and regenerative farming practices. This would ensure food system resilience and the maintenance of truly sustainable traditional practices and knowledge to be deployed in case of failure of modern plastic-intensive approaches.

Policy demands, opportunities and stakeholder contributions for a sustainable use of AP

Policies to address the environmental implications of AP could be articulated along a range of options. The FAO report (FAO, 2021) has advocated for a holistic approach to address negative implications of plasticulture and to guide analysis during the development of the VCoC. This is embodied by the ‘6R’ framework listing Refuse, Redesign, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle and Recover as elements for consideration in the definition of best practices. Given the interlinkages with food security aspects and farm economy, addressing the problem posed by AP represents a major and difficult endeavour where industries, regulators, farmers, waste management and scientists will all have an important role. According to the inputs from the stakeholder survey, the specific actions that policymakers and governments should consider and implement can be clustered around three groups of interventions: (1) Lay foundation of sustainable management of agricultural plastics, (2) Strengthen demand for sustainable products and practices, including considering plastic-free practices in production, and (3) Unlock innovation potential. A synthesis of these actions per group and actor is provided in Table 3.

As for laying the foundation of sustainable management, policy could focus on the establishment of mandatory recording of official and spatially resolved data for AP use and waste generation (the disclosure of which is now prevented by market protection aspects) and the establishment of mandatory management schemes specifically for APW, which in turn should stimulate circularity. Policy instruments should include financial viability provisions for the development of infrastructure for waste management and recycling.

As for actions that can further strengthen the demand for sustainable alternatives and practices, they range from: support for large-scale pilots (time and area) of alternative plastic materials to vet their effectiveness, with controls, towards implementing alternatives at national scales, and with subsidy schemes for implementation and infrastructure development; co-funding schemes for biodegradable mulches with proven effectiveness and safety; tax reductions for farms that adopt sustainable plastic management practices; premium prices on products sale for the farms that adopt sustainable practices; development of certification schemes, awards/recognition schemes – to setting up framework agreements between public authorities and the sector, defining objectives, criteria of performance and implementing a monitoring system adapted to the local situation to ensure sustainable practices goals are achieved. Jointly endorsing innovative designs for the sustainable use of modern AP-based production system and nature-based solutions is essential for the resilience of food systems. By maintaining such a diversity in production practices expressed in all regions, policy could simultaneously tackle the elements of reduction/rejection and redesign (included in the 6R framework; FAO, 2021), by spatially diversifying practices.

Finally, the task of creating the framework conditions for unlocking the innovation potential expressed by all economic parties, include: develop robust national and international approaches on the content, use and disposal of agricultural plastics paying attention to the specificity of the regions; entice practitioners towards the development of alternatives by facilitating new markets creation through customised financial mechanisms depending on existing local practices, crops and socioeconomic conditions; subsidise businesses where designed solutions address the full life cycle of agricultural plastics; adopt regulations and financial incentives to promote circularity of agricultural plastics; and finance R&D for new materials that do not affect soil and plant ecosystems.

The sustainable use and management of plastics in agriculture presents a unique challenges and opportunities compared to other sectors linked to a number of factors such as: (i) dispersed nature of plastics use and pollution, often in remote locations; (ii) significant gaps or entirely lacking plastic waste management infrastructure forcing farmers to resort to open burning or uncontrolled dumping; (iii) agricultural plastics like mulch films and greenhouse covers are often contaminated with soil, pesticide residues or plant matter, making recycling more difficult and costly compared to cleaner plastic waste streams; (iv) low residual value of used agricultural plastics provides little economic incentive for farmers to collect and recycle the waste, unlike more valuable plastic waste streams; (v) costs of proper collection, cleaning and recycling of agricultural plastics can be prohibitive for farmers with limited resources; (vi) lack of clear regulations and EPR schemes; and (vii) plastics including plastic waste national regulations often do not or not adequately cover the unique challenges of APW management. For these reasons, the application of a sector-specific approach using voluntary instruments, such as the VCoC under development by the FAO, or the inclusion of sector-specific approaches in the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, is favoured by many stakeholders.

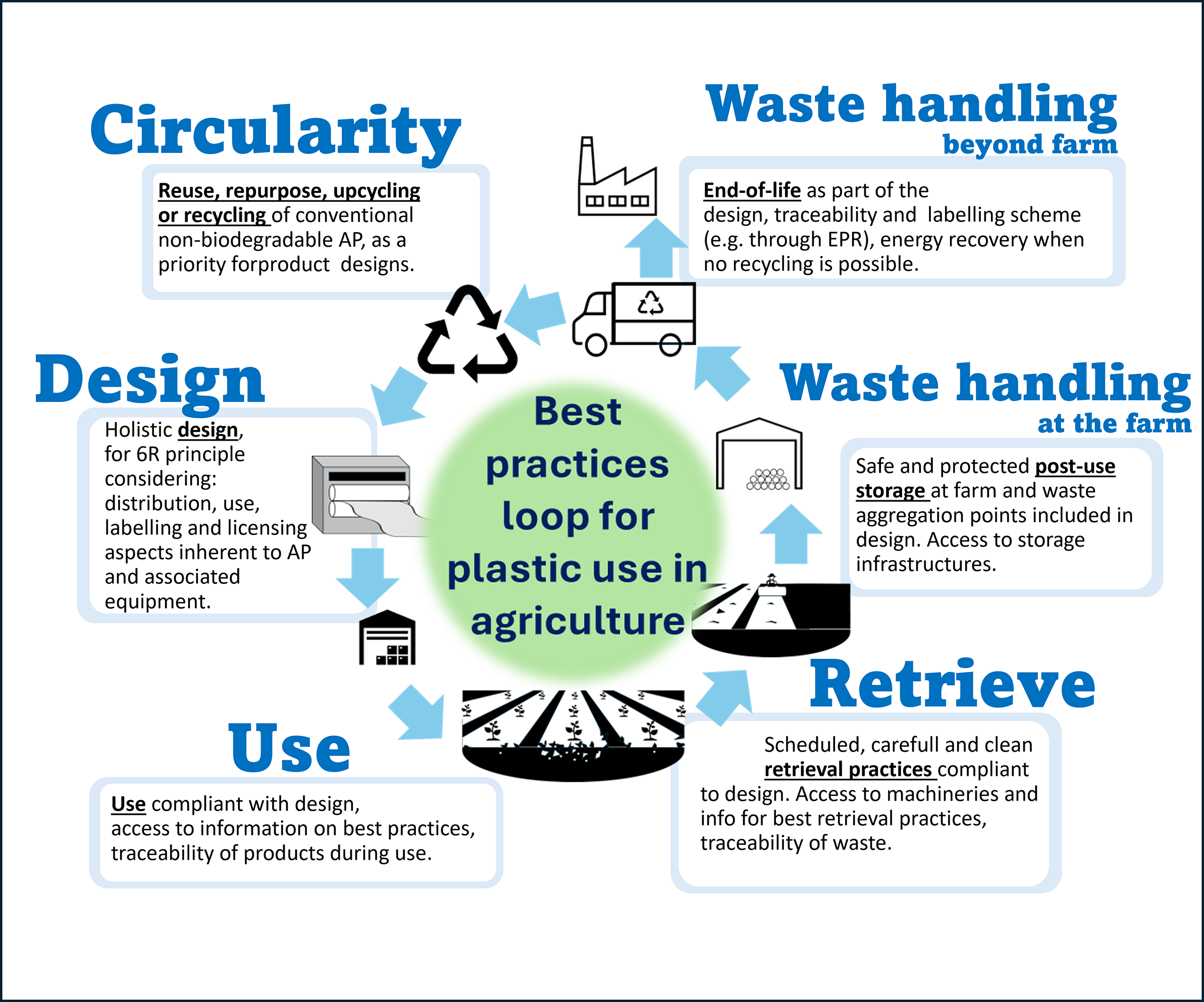

The stakeholder perspectives presented here reveal a shared concern among all actors for the potential impacts of AP on environmental health and agriculture, as well as a common view over the usefulness of circularity-oriented solutions. Figure 1 summarises a circularity model as a possible synthesis of inputs collected from the different stakeholders involved in this analysis. According to this framework, best practices could be implemented at each stage of the value chain thanks to collaborative efforts, whereby holistic design plays a steering role also for downstream stages. These solutions should involve all main actors along the food production chain whereby the design, labelling, traceability, control over environmental safety standards and deployment of infrastructures and schemes for waste management are centralised, and whereby the cost of transition is fairly distributed along the food value chain.

Figure 1. Best practices loop: an agriplastics management model elaborated considering information and insights provided by the stakeholders.

Considering these diverse aspects, understanding and solving counterposed standpoints among stakeholders is key to effective policymaking and to establishing a collaborative dialogue to stimulate the innovation. Figure 2 illustrates a model for innovation in the sector, which can be used as a frame to enable collaboration among stakeholders towards co-design and testing of new products and solutions. The model addresses four key pillars of innovation: knowledge building, awareness and behaviour change, prototyping and demonstrators. Scientific findings should be assimilated as part of this process and represent the fulcrum for a constructive dialogue, paving the way for the co-creation of sustainable solutions, behavioural change, and the accelerated uptake of innovations in the sector.

Figure 2. A co-design and co-development framework proposed to accelerate sustainability-oriented innovation in the area of agriplastics.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2024.34.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2024.34.

Acknowledgements