The remains of a nineteenth century BC Egyptian mudbrick fortress at Uronarti, Sudan. This orthorectified image was produced using a 3D model created from a series of kite aerial photographs. © Laurel Bestock and Christian Knoblauch.

Early Europeans who visited the Maranhão region of northern Brazil during the seventeenth century described the use of camboas (fish traps) by indigenous groups. Local communities today also attribute these traps to past indigenous populations. Their precise chronological and cultural origin, however, is unknown. The fish traps are made of locally sourced materials including plinthite and petroplinthite. © André Colonese.

In December 2014 the International Monetary Fund announced that a long-anticipated milestone had been passed and that China had overtaken the USA to become the world's largest economy. Given the size of the Chinese population, numbering 1.4 billion people (or almost 20% of all those alive today) that is perhaps no surprise, and in terms of individual living standards, China has some way to go before its citizens achieve the same average income level as those of western Europe or North America. But the growth of the Chinese economy has already been echoed in the expansion of its archaeology, and articles on the prehistory and early historic societies of China have featured regularly in recent issues of Antiquity. The current issue is no exception, and in particular includes an article about one of the rather puzzling episodes in the Chinese past: the overseas voyages of the Ming admiral Zheng He (see below pp. 417–32). Between 1403 and 1433, Zheng He led seven imperially sponsored missions, each of them on a massive scale, around the coasts of Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, reaching as far afield as Aden and East Africa.

Prefiguring the European voyages of exploration later in the same century, these Chinese voyages began to forge stronger maritime links and join the different parts of the world together into a single system. A key node in these voyages, visited by Zheng He's fleet on four separate occasions, was the island of Hormuz at the entrance to the waterway known as the Persian or Arabian Gulf. Direct archaeological evidence of these visits survives in the form of Chinese pottery collected from Hormuz, including sherds of the classic imperial Ming blue-and-white porcelain. Lin Meicun and Ran Zhang in their article explore the wider significance of this material for Chinese overseas relations in the early fifteenth century. The Ming blue-and-white porcelain may indeed have been part of Zheng He's diplomatic gifts to local rulers. Alongside these valuable wares, however, are poorer quality wares that testify to commercial trade, perhaps conducted against imperial orders by members of Zheng He's expedition. In the event, direct Chinese involvement in the Gulf endured for only a few decades, and by early on in the following century, Hormuz was under Portuguese control. The Chinese pottery nonetheless stands as a timely reminder that the Europeans were by no means the first foreign power to recognise the strategic importance of this vital waterway and to start spreading their influence overseas.

Rescuing damaged sites

Move north from Hormuz and one enters the troubled region of Iraq and Syria, where the ongoing human tragedy is accompanied by widespread devastation of the archaeological heritage. Reports suggest that ISIS is engaged in (or encouraging) systematic looting of archaeological sites in order to fund its operations. Major ancient cities such as Nineveh and Nimrud are within the area that they control, while in Syria to the west, sites such as Palmyra are under threat not only from looting but also from military operations. Sad to say, it is difficult to see this situation improving any time soon.

These conflicts leave archaeological sites damaged and pockmarked, with structures and sculptures removed and sold, or destroyed. Yet vital evidence can sometimes survive. An example of what can be achieved is presented by the Roman and Byzantine village of Hosn Niha in the Biqa' valley of Lebanon. This fell within one of the hotspots of the Lebanese civil war, and it was believed that little remained of the settlement on the hillside below the temple sanctuary. Bulldozers had been used in the hunt for saleable antiquities, and some areas had been entirely destroyed. For Paul Newson and Ruth Young, however, the destruction of Hosn Niha presented both a challenge and an opportunity (‘The archaeology of conflict damaged sites: Hosn Niha in the Biqaʾ Valley, Lebanon’: below pp. 449–63). What archaeological evidence can be salvaged in these circumstances? Should sites such as this be studied, or given up for lost and ignored?

In 2011 and 2012, Newson and Young led a systematic survey of the remains, recording houses, quarries and tombs, and collecting and mapping the distribution of different pottery types across the site. Much of this material had been brought to the surface by the bulldozing itself, and it was clear that the core of the ancient settlement had been largely destroyed. Around its edges, however, the survey brought to light new structures, and allowed an overall assessment to be made of the settlement and its surrounding features. As the authors conclude, warfare in this region is continuing to take a major toll on the archaeological record, but their survey shows that even sites that have been very badly damaged have the potential to tell us about human activity in the past. With conflict continuing, this is a lesson we may all need to learn for the future.

A fragile survival from the past

Damage of a different kind hit the news recently when Greenpeace activists laid out a message “Time for Change! The future is renewable” next to the elaborate humming bird that is one of the most famous images of the ‘Nazca lines’ in the Peruvian desert. The aim of the activists was to put pressure on world leaders gathered in Lima to discuss a new agreement on climate change, but they had not thought carefully about the location they had chosen. A recent article in Antiquity described this as “one of the world's most fragile archaeological landscapes” (Ruggles & Saunders ‘Desert labyrinth: lines, landscape and meaning at Nazca, Peru’ Antiquity 86 (2012), 1126–140). Ruggles and Saunders note that one of the most surprising features of the Nazca lines is how little they have been damaged; movement across this landscape when the lines were being made and used must have been strictly controlled. Even a slight divergence from the prescribed pathways would have left traces that would still be visible today, 2000 years later. In order to preserve the Nazca lines, access to the area has in recent decades been strictly controlled by the Peruvian authorities, and visitors view them from above in short aerial tours from one of the neighbouring airports. All the more ironic then that activists seeking to draw attention to the fragility of the earth's environment have, unintentionally, damaged it in this way.

The complexity and the exceptional preservation of the Nazca lines combine to make them one of the most intriguing legacies of pre-Columbian South America. It is the thinly populated arid environment that is largely responsible for their survival. Unusual preservation is not always on this scale, however, nor in such a remote and spectacular setting. Shortly after reading about the Nazca episode, I had opportunity to revisit a much smaller but still striking example of unusual preservation at Greensted in Essex, not far outside the London suburbs and within the commuter belt—until its closure in 1994 the station at nearby Chipping Ongar marked the terminus of the London underground Central Line. A narrow side road from Chipping Ongar leads past the few houses of Greensted to the Church of St Andrew, the sole surviving example of an early medieval timber church in England. It claims to be the oldest wooden church in the world.

St Andrew's Church at Greensted in Essex, showing the eleventh century timber walling of the nave. Photograph: Judith Roberts.

Akin to most medieval churches, St Andrew's has been extensively modified. When told that a building is Anglo-Saxon in date the sceptical archaeologist always questions which particular part of the building is meant. There were major changes to the church over the years, not least in the nineteenth century, but the original timberwork is striking in appearance and impossible to miss. Split oak trunks form the side walls and the western end wall. Grooved and tongued to make a continuous weatherproof structure, they are raised off the ground and rest today on a brick plinth, but are thought to have been originally set directly in a bedding trenchFootnote 1 . Over the centuries, their lower ends rotted away, and the Victorian restorers chopped off the decayed material, which makes it hard to say how tall they once were. But we do know they are old: dendrochronology in the 1990s dated them to 1053 +10–55 years (British Archaeology December 1995) (i.e. somewhere between 1063 and 1108—shortly before or after the Norman Conquest). Roof, chancel and tower are later additions, but most of the timbers are clearly original, if truncated, and despite the many modifications they are a striking reminder of how many early European churches must have looked.

Profiling the profession

How are we as archaeologists seen by outsiders? “The Hollywood image of the dashing adventurer bears little resemblance to the real people who, armed with not much more than a trowel and a sense of humor, try to tease one true thing from the rot and rubble of the past.” So we read in the opening pages of a recent book that seeks to give insight into who archaeologists are and what they do, across a whole range of contexts. In Lives in ruins: archaeologists and the seductive lure of human rubble, Marilyn Johnson offers a detailed and generally sympathetic account that puts flesh on the bone. She takes us through a number of settings—fieldwork, conferences, university programmes—to show the variety of the things with which archaeologists have to contend. Underpinning it all is the dedication that drives us as practitioners, and not far behind that are the slim and uncertain rewards that many archaeologists accept, at least in the early stages of their careers. The rewards lie elsewhere.

Johnson's account offers many familiar and memorable moments—the cash-strapped excavation projects in overseas settings, the conference discussions, the struggle to save things before they are destroyed. Not surprisingly, perhaps, we learn that archaeologists see the world in a different way. On a conference excursion to Machu Picchu, for example, we are told how “you can tell the archaeologists, of course, by their photos. The tourists' photos feature people in front of mountains, terraces, stone structures, sundials. The archaeologists wait until the people move away to take theirs: they want the terrace, the stone wall, the lintel, the human-made thing, all sans humans.” Trying to photograph crowded sites is a problem with which I am sure most of us will be familiar.

This is a readable and enjoyable account of the dedication and enthusiasm of which our profession should rightly be proud. One feature emphasised by Johnson is archaeologists' sense of responsibility—towards preserving or recording the remains; towards their field teams and the local communities they work among; towards protecting cultural heritage in times of conflict. If one of her chapters is subtitled ‘Taking beer seriously’ another carries the by-line ‘Mission: respect’.

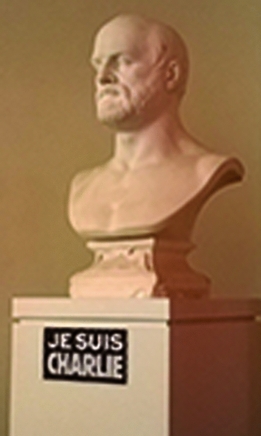

The bust of Charles Quicherat, first professor of archaeology at the École Nationale des chartes at Paris, in the aftermath of the 7 January attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices. Photograph: Nathan Schlanger.

In this context, it was not surprising to learn that the recent murders in Paris triggered responses from students of archaeology. In the École nationale des chartes, the bust of its first professor of archaeology, Jules Quicherat (1814–1882), was festooned with the message “Je suis Charlie”. Nathan Schlanger has recently become the latest holder of the chair established for Quicherat. He writes: “Venerable institutions have venerable traditions. At the École nationale des chartes in Paris, established in 1821 to promote the critical study of history, this striking bust has endured generations of student pranks designed to enliven the erudite surroundings. Since the 7 January 2015, it serves to broadcast a vital republican message of freedom, tolerance and determination.” Archaeologists may not always be well paid, but the subject remains as relevant as ever.