Introduction

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a trans-diagnostic, contextual cognitive behavioural therapy that seeks to improve well-being through processes that promote steps toward valued actions, whilst reducing the impact of unhelpful psychological processes of cognitive fusion and emotional and behavioural avoidance (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006). The overall aim is to increase psychological flexibility in the face of unwanted distressing thoughts and emotions (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson2012). There is now a significant body of treatment outcome research suggesting that the integration of acceptance, mindfulness and compassion-focused principles within cognitive behavioural therapies is effective in improving well-being and quality of life (A-Tjak et al., Reference A-Tjak, Davis, Morina, Powers, Smits and Emmelkamp2015; Ruiz, Reference Ruiz2010). Despite substantial literature for the efficacy of these interventions across a range of disorders, there is only a limited evidence base into the generalizability of these findings and applicability to different BME populations in a UK context.

Cultural and socio-demographic factors influence the way people experience distress, symptom expression and help seeking behaviours (Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Aslam, Palinski, McCabe, Johnson, Weich, Singh, Knapp, Ardino and Szczepura2015; Furnham and Malik, Reference Furnham and Malik1994; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri, Harris, Underwood, Thagadur, Padmanabi and Kingdon2013). Cultural modifications are therefore necessary and important considerations when attempting to demonstrate the clinical and cultural competency of a treatment approach for diverse communities in terms of inclusion of cultural knowledge, therapeutic process and equitable service delivery (Tseng, Reference Tseng2004).

Cultural adaptation is the ‘systematic modification of an evidence-based treatment or intervention protocol to consider language, culture and context in such a way that it is compatible with the client's cultural patterns, meanings and values’ (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009, p. 362). A critical aspect of culturally adapting an intervention to the needs of a particular community is the integration of both ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ approaches. The Ecological Validity Model (EVM) proposed by Bernal et al. (Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995) is based on a bottom-up community-engagement approach and advocates building collaborative relationships with community stakeholders in order to increase the social validity (i.e. acceptability) of the adapted intervention. They suggest that culturally adapted interventions are more effective when there is congruence between the cultural perspective of the community and the properties of a particular therapeutic intervention, with poor response to treatment possibly indicative of poor social validity (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995; Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009; La Roche and Lustig, Reference La Roche and Lustig2013).

Empirical support for this proposition, derives from a meta-analysis of 76 studies, which found a weighted average effect size of d = .45, indicating a moderately strong benefit of culturally adapted interventions in client improvements across a variety of conditions and outcome measures (Griner and Smith, Reference Griner and Smith2006). Literature exploring aspects of adaptations indicate that factors such as ethnic matching, provision of interventions in the client's native language and adaptations tailored to a specific cultural context are more efficacious, with an increased likelihood of enhanced engagement, retention and satisfaction (Griner and Smith, Reference Griner and Smith2006). Delivery within a local community setting enhances accessibility and consultation with individuals familiar with the clients’ culture and being inclusive of support resources that are available within collectivist cultural contexts (e.g. spiritual traditions, extended family) also facilitated positive outcomes (Griner and Smith, Reference Griner and Smith2006). In addition, a recent systematic review on therapeutic interventions and communications with BME communities concluded that the cultural adaptation of western psychological therapy models improved therapeutic outcomes when there was an emphasis on empowerment (Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Aslam, Palinski, McCabe, Johnson, Weich, Singh, Knapp, Ardino and Szczepura2015).

Currently, within the ACT literature there are several types of culturally adapted ACT interventions and successful evaluations facilitating positive outcomes across diverse, non-western populations, such as in Iran, India and South Africa (e.g. Hoseini et al., Reference Hoseini, Rezaei and Azadim2014; Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Lee, Roemer and Orsillo2013; Woidneck et al., Reference Woidneck, Pratt, Gundy, Nelson and Twohig2012; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Hong, Zane and Oanh2011; Lundgren et al., Reference Lundgren, Dahl, Melin and Keis2006, Reference Lundgren, Dahl, Yardi and Melin2008). Other research has also found that ACT training workshops in Sierra Leone were both culturally applicable and accessible (White and Ebert, Reference White and Ebert2014; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, White, Ebert, Mays, Nardozzi and Bockarie2016). This growing body of literature explores the efficacy of adapting ACT for non-western collectivist cultures and coupled with the wider literature on cultural adaptations, highlights the need to explicitly incorporate cultural content, context and values relevant to the client's well-being into the intervention (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009; Griner and Smith, Reference Griner and Smith2006).

Cultural adaptation of ACT to a Turkish-speaking context

The Turkish diaspora in Europe consists of three main groups: Kurdish, mainland Turks and Turkish Cypriot communities (Eylem et al., Reference Eylem, van Bergen, Rathod, van Straten, Bhui and Kerkhof2016). These groups migrated to Europe for different historical and political reasons (Enneli et al., Reference Enneli, Modood and Bradley2005). Besides the cultural, ethnic and religious differences between these groups, they share commonalities such as language and collectivist values (e.g. duty, roles, relatedness, interdependence, familism, community) based on their history of interaction (Eylem et al., Reference Eylem, van Bergen, Rathod, van Straten, Bhui and Kerkhof2016; Kuzulugil, Reference Kuzulugil2010). Experiences and expressions of distress are thus formulated in terms of a shared knowledge and shaped by cultural, sociopolitical and historical contextual factors (Eylem et al., Reference Eylem, van Bergen, Rathod, van Straten, Bhui and Kerkhof2016).

ACT is a highly pragmatic, experiential and collaborative therapeutic approach based on connecting people to important values and using this information to guide therapeutic process and promote flexible and purposeful living (Masuda, Reference Masuda and Masuda2014). The emphasis on values and context are two central tenets of the ACT model that offer potential for cultural adaptability for Turkish-speaking communities given their collectivist structure and many experiences of distress being located in contextual circumstances (Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Lee, Roemer and Orsillo2013; Woidneck et al., Reference Woidneck, Pratt, Gundy, Nelson and Twohig2012) such as familial relationships (e.g. marital and/or inter-generational conflict) and collective experiences of loss, displacement, being a refugee, war and genocide. This is congruent with the philosophical orientation and contextual therapeutic stance of ACT (Masuda, Reference Masuda and Masuda2014; Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda and Lillis2006), which then teaches mindfulness and acceptance processes and skills (such as present moment awareness and defusion) to change an individual's relationship to unwanted internal experiences (painful thoughts, feelings, memories and sensations) rather than changing the experience itself. Furthermore, ACT uses the behavioural change process of ‘committed action’ (in the service of values) to open up choices that may help to overcome hopelessness and foster a greater sense of empowerment, meaning and purpose. Thus, the clinical utility of ACT for Turkish speaking clients may be in helping to enhance their sense of personal agency and emotional resilience through developing psychological flexibility in response to distress so people learn how to live well in the presence of difficult life circumstances.

Service context

The ‘Psychological Therapies Alliance’ (PTA) was implemented by the City and Hackney Clinical Commissioning Group to integrate care pathways between statutory and third-sector providers of psychological and psychosocial interventions and increase equity of access for BME communities (City and Hackney Clinical Commissioning Group, 2015). Developing specific provision involving collaboration with targeted communities has been highlighted in the literature relating to the importance of cultural adaptations outlined above (Bhui and Olajide, Reference Bhui and Olajide1999; Bhui et al., Reference Bhui, Bhugra and McKenzie2000, Reference Bhui, Aslam, Palinski, McCabe, Johnson, Weich, Singh, Knapp, Ardino and Szczepura2015). This recognizes the important role of third-sector partnerships in the development and delivery of therapeutic services, with subsequent implications for clinical practice in terms of accessibility and utilization of talking therapy services for BME communities.

As a highly trusted third sector organization, Derman provides a range of health-related services to Kurdish, Turkish, Turkish Cypriot and Eastern European Turkish-speaking people (mainly asylum seekers and people from refugee backgrounds) in Hackney and plays a central role as a bridge between community members and statutory services. They have invaluable knowledge of the physical and mental health needs of the local communities they serve and are often the first line of assistance to those seeking help.

The City and Hackney BME Access Service (ELFT) is located within secondary care and works in close partnership with key third-sector organizations and internal stakeholders to address barriers to accessing appropriate talking therapies among local BME communities. The service is based on the Centre for Ethnicity and Health's Community Engagement Model (Fountain et al., Reference Fountain, Patel and Buffin2007) and employs a community psychology approach that aims to meet the mental health needs of under-represented groups through equitable access, improved service experience and outcomes.

The PTA commissioned this partnership initiative in line with national government directives on BME positive practice guidance (promoting joint working between statutory services, local third-sector organizations and faith groups; Department of Health, 2009) and in relation to previous research forming part of the national community engagement NIMHE Mental Health ProgrammeFootnote 1 which recommended improving the provision and quality of culturally appropriate talking therapies for Turkish-speaking communities (Tas et al., Reference Tas, Guden, Tekin, Guler, Doner and Kalen2008). A project between the City and Hackney BME Access Service and Derman was therefore established to pilot the development and delivery of a culturally adapted ACT group intervention, with the over-arching purpose of improving the acceptability and accessibility of talking therapies within these communities.

Aims of the ACT group

(1) To explore the cultural flexibility of the ACT model and produce a culturally relevant adaptation of an existing ACT group therapy protocol (‘ACT – Promoting Mental Health and Resilience’; Livheim, Reference Livheim2014) that is responsive to the therapeutic needs of participants from Turkish-speaking communities.

(2) To assess the acceptability of the culturally adapted version of the ACT group format for members of the Turkish-speaking communities.

(3) To measure if the culturally adapted ACT group intervention improved psychological well-being amongst Turkish-speaking participants.

Method

Cultural adaptation framework

The ecological validity model (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Bonilla and Bellido1995) was chosen to guide the process of modifying an existing ACT treatment protocol as this framework allowed the core principles of ACT to be retained but with adequate flexibility for cultural adaptation, thereby preserving validity to the original treatment (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri, Harris, Underwood, Thagadur, Padmanabi and Kingdon2013). The ecological validity model delineates eight dimensions to consider when culturally adapting an intervention. These include the use of appropriate language, persons (cultural similarities/differences between the client and clinician which shape the therapeutic relationship), metaphors (symbols and concepts), content (cultural knowledge), concepts (treatment concepts that are culturally congruent), goals (that support adaptive cultural values), methods (cultural enhancement of treatment methods) and context (consideration of acculturation, social context).

Consultation

The therapeutic protocol described here is based on the 7-session ‘ACT – Promoting Mental Health and Resilience’ group therapy framework developed by Livheim (Reference Livheim2014) and adapted by the City and Hackney BME Access Service in collaboration with Derman. The main structure of the original Livheim ACT group format was maintained but different elements were distilled for cultural appropriateness and accessibility.

The process of adaptation was informed by two 3-hour community consultations with Derman. Nine participants attended the first session and seven attended the second. Participants included the chief executive officer of Derman, mental health advocates, counsellors, support workers and administrative staff. Consultations allowed space for a detailed discussion of the main components of the Livheim ACT group programme to be carefully examined for cultural relevance and produced a number of important suggestions incorporating cultural understandings of mental health and well-being within a Turkish-speaking cultural context.

Turkish-speaking cultures are rich in proverbs, poems, songs and stories and so efforts were made to link cultural knowledge to key ACT concepts and practices by using cultural bridging techniques such as culturally relevant metaphors, values, traditions, common folk stories (e.g. the ‘farmer and the horse’), cultural imagery and inspirational role models.

For example, images of the revered Sufi poet and philosopher Mevlânâ (Rūmī) were used to represent the embodiment of openness, kindness and compassion to life's experiences, self and others. Popular teachings and poems (e.g. ‘The Guest House’; ‘Come, Come, Whoever You Are’) were used to illustrate core ACT processes and mindfulness skills (contact with the present moment, acceptance, self as context, defusion) and cultivate a welcoming stance toward all internal experiences (Mirdal, Reference Mirdal2012).

Culturally familiar, non-technical language and video material from popular Turkish media were also used to explain therapeutic concepts. For example, a short film showing a successful Turkish businessman living with blindness from birth was used to inspire perseverance and persisting in the service of chosen values.

A culturally syntonic translation of the material was made and the completed 7-session adapted group therapy format was written up in both English and Turkish. The final group protocol combined didactic elements, group discussion, role plays and experiential group exercises (e.g. mindfulness [mindful eating with Turkish delight], life compass, ‘passengers on the bus’, Chinese finger traps). The culturally adapted ACT group protocol was renamed: ‘Farkındalık ve Şevkatle Kabullenme’ (‘Acceptance with Mindfulness and Compassion’).

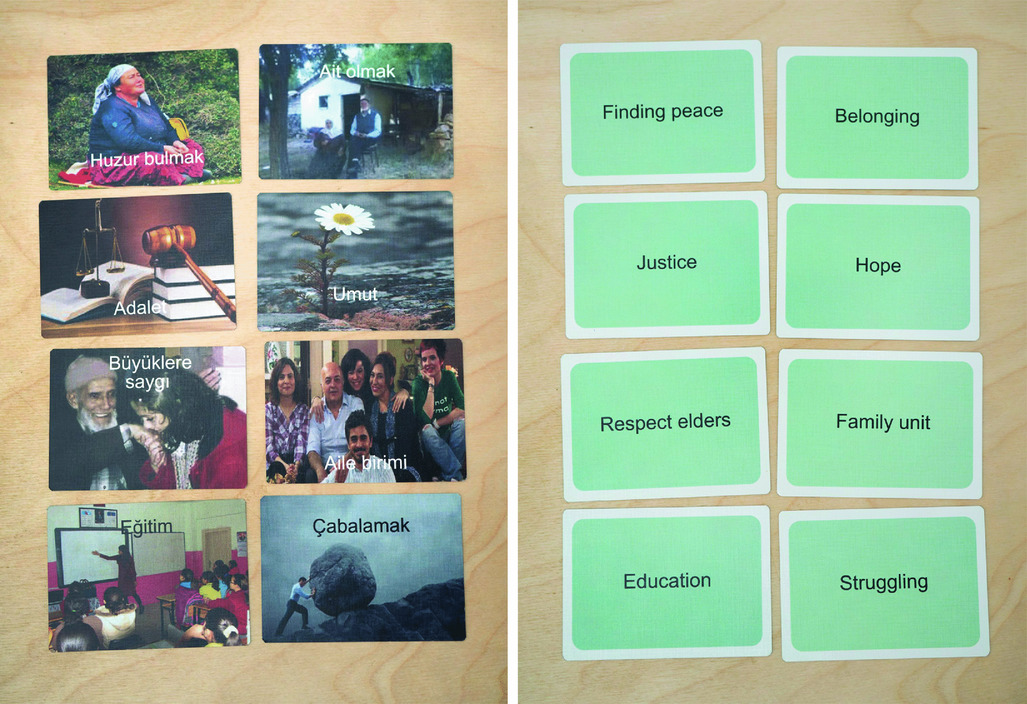

The adaptation process also produced shared resources so that the group could be delivered in both statutory and voluntary sectors in the future to support sustainability. Resources included collectivist value cards specifically developed for Turkish-speaking contexts. For example, the cultural value ‘Çabalamak’ (‘Struggling’) is imbued with the qualities of courage, perseverance and strength to overcome difficulty. See Fig. 1 for details. Two audio CDs containing acceptance, mindfulness and compassion focused exercises recorded in Turkish were also provided to support home practice.

Figure 1. Turkish collectivist ‘value cards’

Design

The study implemented a mixed-method analysis with a one group pre/post-test design to examine the effectiveness of the culturally adapted ACT group and a descriptive approach was implemented to assess the usefulness, relevance and acceptability of the group from qualitative feedback.

Procedure

The ACT group consisted of 2-hour weekly sessions over 8 weeks. The group was co-facilitated by the (English speaking) BME Access Service clinical psychologist and bilingual mental health coordinator from Derman. The group was predominantly delivered in the Turkish language and a bilingual advocate provided additional language support within the group by translating group material from English to Turkish and Turkish to English for the clinical psychologist. The final session was used for completing post-intervention measures and provided an opportunity to collate service user satisfaction feedback. The ending of the group was celebrated with food and participants were awarded with a certificate for completing the group and given copies of the CDs with acceptance and compassion exercises.

Sampling and recruitment

Referrals were received via the City and Hackney mental health network (City and Hackney MIND), from GPs, other local authorities or self-referral, and group participants were randomly selected from Derman's mental health waiting list. Clients identified as appropriate were offered the option of attending the ACT group. Those who agreed were jointly assessed for suitability by the BME Access Service clinical psychologist and mental health coordinator from Derman.

Group inclusion criteria

The target group population were Turkish-speaking men and women representing the Turkish diaspora (Kurdish, Turkish and Turkish Cypriot) who access Derman services, aged between 18 and 65 years. Participants needed to be motivated to attend group therapy for issues related to stress, anxiety and low mood.

Clients were excluded from the group if they:

• Were experiencing acute symptoms of psychosis;

• Had a diagnosed learning disability;

• Presented with ambivalence or low motivation to engage in group work;

• Historically had a high ‘did not attend’ rate;

• Presented with a primary problem of gambling, drugs, alcohol;

• Were in early stages of bereavement and presenting with acute grief.

Setting

The ACT group was delivered in a spacious group meeting room within the community setting of Derman, a venue that was considered to be a safe and accessible space for community members.

Group participants

The group was closed and a total of eight participants were recruited. The main presenting difficulties of participants were: relationship problems (marital, intergenerational), chronic pain, anxiety, depression, low self-esteem and long-standing health problems.

Measures

Three pre- and post-test measures were used to evaluate psychological well-being, which were standardized measures across the service context. All measures were translated into Turkish and verbally administered:

• A shortened version of the CORE (CORE-OM; Barkham et al., Reference Barkham, Bewick, Mullin, Gilbody, Connell and Cahill2013) measuring levels of psychological distress.

• The depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke and Spitzer, Reference Kroenke and Spitzer2002), which measured depression symptoms and severity.

• The GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe2006) measuring common anxiety symptoms and severity.

Two patient-rated experience measures were used to capture the views and experiences of participants: the Most Important Event (MIE) questions were asked after each session: ‘What was the most important/helpful thing that happened here today?’ and ‘What was the least important/unhelpful thing that happened here today?’. Responses were recorded verbatim, providing qualitative feedback from each session. These questions were chosen as they linked to previous literature on methods for identifying what is helpful for clients and assessing therapeutic factors in group therapy associated with client outcomes (Berzon et al., Reference Berzon, Pious and Farson1963; Bloch et al., Reference Bloch, Reibstein, Crouch, Holroyd and Themen1979; Lieberman et al., Reference Lieberman, Yalom and Miles1973; Yalom, Reference Yalom1975).

Secondly, a brief service user satisfaction questionnaire was developed and administered in the format of an evaluation interview at the end of the group intervention (session 8). Participants were also offered a reflective space in this session to review the group as a whole and provide individual feedback.

Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS version 22.

Quantitative analysis

Paired t-tests were performed to compare pre- and post-test measures, as data met assumptions of normality. Effect sizes were then calculated, as outlined by Lakens (Reference Lakens2013). As Cohen's d has been shown to give a slight bias in effect size within small sample sizes (Borenstein et al., Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein2009; Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Lee, Roemer and Orsillo2013; Lakens, Reference Lakens2013), a more conservative measure of effect size was calculated using Hedges’ gav or grm (as recommended by Lakens, Reference Lakens2013). This Hedges correction can be interpreted with Cohen's convention of effects sizes.

Given the small sample size, individual level change was assessed with reliable change indices (RCI), where change is reliable when greater than might be expected by chance, given the reliability of the measure. Where reliable change was detected, further analyses were performed to determine what percentage of reliably improved scores could also be considered clinically significant. Criterion C of Jacobson and Truax (Reference Jacobson and Truax1991) was used to define clinically significant change (CSC) as a person's score being in the ‘clinical’ range pre-treatment and below the clinical cut-off post-treatment.

The quantitative data from the service user satisfaction survey were collated to present frequency feedback.

Qualitative analysis

A thematic analysis was conducted on the data derived from the MIE questions every session, the qualitative responses on the service user satisfaction survey and the verbatim recording of the reflective group discussion post-intervention. The thematic analysis followed steps outlined in Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006), which included six steps: ‘familiarization, searching for themes, review of themes, definition and naming, and production of the report’. Emergent themes were discussed with another independent rater to check that they were grounded in the data and reduce the risk of idiosyncratic readings of the data being sustained.

Results

One participant dropped out due to obtaining paid employment; therefore their data was omitted and the results section describes data for the remaining seven participants.

Group attendance

The group was well attended, with attendance above 70% for each session.

Demographics

All participants were first generation (i.e. born outside the UK), their ages ranged from 42 to 62 years (average age approximately 55 years) and the majority of participants were female, married and from Turkish and Turkish Cypriot ethnic backgrounds. The average length of time participants were known to Derman was approximately 4.5 years and the majority of the participants had used the counselling and group activity services at Derman.

Treatment outcomes

The results indicate a statistically significant improvement in psychological distress (p = 0.003), depression (p = 0.014) and anxiety (p = 0.041) scores following the group (see Table 1). The mean decrease for depression scores was 6.79 (5.21) with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 1.97 to 11.61. The mean decrease for psychological distress scores was 13.14 (7.03) with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 6.64 to 19.65. The mean decrease for anxiety scores was 6.86 (7.01) with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.37 to 13.34. The magnitude of these changes were categorized as large, with effect sizes ranging from 0.90 to 2.03 (see Table 1).

Table 1. Pre- and post-intervention scores on all outcome measures and associated test of difference

*Significant at p ≤ 0.05; **significant at p ≤ 0.01; ‡indicates effect size g av.

Individual level analyses of reliable change indices and clinically significant change

Table 2 shows the percentage of participants whose changes in scores can be considered reliable. For the CORE-10, all seven participants scored above clinical cut-off at baseline, and 85.7% showed a reliable improvement on this measure of psychological distress post-intervention. For both the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 measures, all five participants who scored above the clinical cut-off at baseline indicated a reliable improvement in both depression and anxiety post-intervention (71.4%). There was no reliable deterioration on any of the measures.

Table 2. Reliable change for outcome measures by severity; and reliable and clinical significant change on outcome measures

Further analyses were carried out to determine what percentage of reliably improved scores could also be considered as clinically significant changes (CSC). For the CORE-10, 42.8% (n = 3) of participants showed both reliable and clinically significant improvement, meaning that following the group they fell below the clinical cut-off for experiencing psychological distress (see Table 2). For the other three participants whose scores reliably improved on the CORE-10 but did not meet criteria for CSC (did not fall below clinical cut-off range), their scores moved from the severe range to either the moderate (n = 2) or the moderate–severe range (n = 1).

Table 2 shows that 28.6% (n = 2) of participants showed both reliable and clinically significant improvements on the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7, meaning that post-intervention their scores fell below the clinical cut-off for depression and anxiety. For the other three participants whose scores reliably improved on the PHQ-9 but did not meet criteria for CSC (did not fall below clinical cut-off range), two participants’ scores moved from the severe range to either the moderate (n = 1) or the moderate–severe range (n = 1), and one participant's scores reduced within the severe range for depression. For the GAD-7, of the three participants whose scores reliably improved but did not meet criteria for CSC (did not fall below clinical cut-off range), two participants’ scores moved from the severe range to moderate (n = 2) and one participant's scores reduced within the severe range for anxiety.

Descriptive information from the service user satisfaction survey

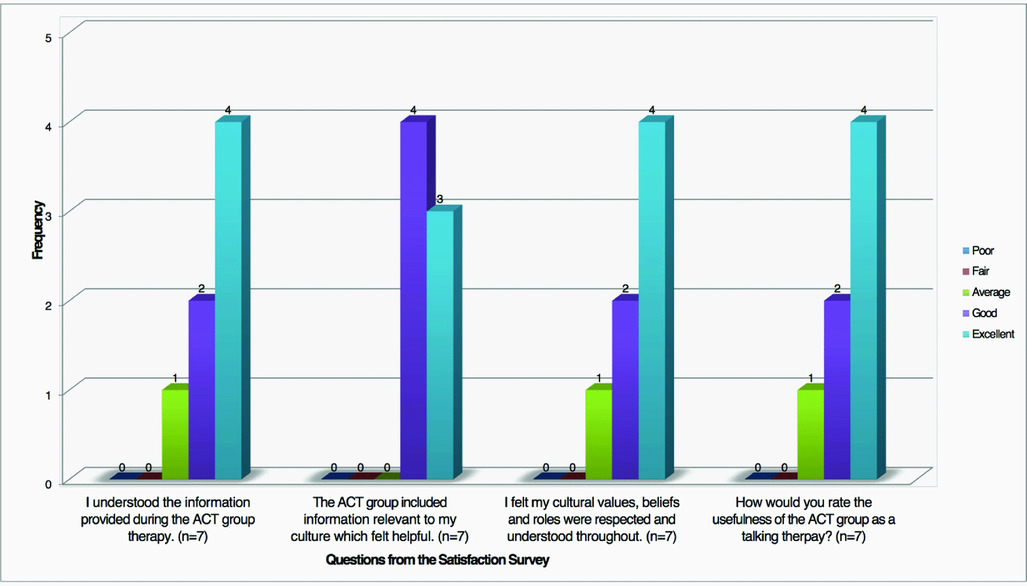

All seven participants reported finding it helpful to talk about their problems and most participants said they understood the information provided in the group. The majority of participants thought that the ACT group was ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ at including relevant cultural information in a helpful way and agreed that aspects of their culture (roles, values and beliefs) were respected and understood. Similarly, the group was rated highly for usefulness as a talking therapy by the majority of participants, except one who rated it as average usefulness. See Fig. 2 for details.

Figure 2. Frequency of responses to questions from the Service User Satisfaction Survey

Thematic analysis

The thematic analysis identified three over-arching meta-themes (with relating sub-themes) which were:

• Group Process (sub-themes: Interpersonal factors; A safe space)

• Change Factors (sub-themes: Emotional transitions; New perspectives; Different actions)

• Reflections/Considerations (sub-themes: Group feedback; Interpreting language; Use of metaphor)

The text identifies quotes that encapsulate the themes and Table 3 presents additional indicative quotes of the themes identified.

Table 3. Themes and indicative quotes

Theme 1: Group Process

This theme consisted of two sub-themes linked to aspects of attendance in a therapeutic group.

Interpersonal factors

All participants commented on various interpersonal processes as being some of the most important aspects of the group. The relationships that developed appeared to link with feeling valued, accepted and connected with others. Five participants highlighted that ‘sharing and being listened to’ were integral within the group. Four participants appreciated hearing the stories and views of others, as it allowed them to reflect on their own experience. The idea of identifying with someone else's story, not feeling alone and learning from others was highlighted by six participants and appeared to be ‘powerful’ within the group and associated with ‘sharing’.

‘The most important part of the group for me was the connection. The relationships in the group, sharing our stories, listening to each other . . . ’ [Participant A]

‘. . . the group process of hearing other peoples’ opinions and listening to them sharing their problems is important as it helps me to think about what I experience.’ [Participant D]

A safe space

There were also various indicators that the group created a safe space, where people felt able to experience emotions and to fully participate (derived from six participants’ comments). This safety seemed to arise from developing relationships between group members, the therapeutic alliance with facilitators and task structure (group sharing and some 1:1 work) where people could experiment with their degree of comfort in sharing personal or difficult material.

‘For me also, the group process was very powerful. Being listened to and attended to and I felt a sense of freedom – it felt safe to talk and be accepted . . . Gave me a feeling of being valued and I felt appreciation for the group space you created . . .’ [Participant F]

‘I felt that I was in safe hands. Special thanks to {facilitator names}.’ [Participant B]

The interpersonal dynamics and group space created an environment where individuals felt connected, validated and comfortable to express themselves and learn from each other. Although this emerged as a positively slanted theme, all members of the group did not hold this view. One participant mentioned that although they found it helpful to talk about their ‘problems’, at times they worried about the group not being ‘confidential or safe enough’ in relation to fears of exposure within the community setting. However, overall it did suggest that this is a generally accessible intervention.

Theme 2: Change Factors

This theme consisted of three sub-themes linked to changes within emotion, thoughts and behaviour.

Emotional transitions

Five participants identified accessing emotion as a key feature of the group. The group facilitated the discovery of more positive emotions, which participants found liberating, either in the actual experience itself or in knowing that this emotion can exist within them. Some of the most frequent emotions identified by all participants were ‘compassion, kindness and enjoyment/happiness’:

‘I realized I was carrying a lot of anger too but not any more as I was able to access human kindness today and this made me aware of where I am.’ [Participant G]

‘. . . it was a releasing feeling and it was so good to notice that I don't live with hatred anymore and I actually have compassion and kindness in me. The experience I had with this person made me feel like I wasn't human anymore – I felt like a monster – but the compassion exercise helped me to reconnect with my humanity and this was powerful and healing . . .’ [Participant C]

Six participants commented on accessing new emotions towards others in their lives, with five participants linking this to people whom they had difficult feelings towards. This enabled participants to notice other aspects of their experience, and relate to these individuals or memories in a different way. This appeared to assist participants to believe that they could move forward from the confines of their difficulties:

‘I still feel the feeling of compassion for this person since the last session – it was such a strong feeling and I went through the most powerful emotional process – I had to leave the session. It shifted something . . .’ [Participant F]

Four participants also indicated that they felt more able to relate differently to some emotions, suggesting acceptance of difficult feelings. These participants identified a relationship between accessing new or different emotions (e.g. compassion) and deepening their capacity to experience other difficult feelings. The mindfulness and compassion exercises stood out as useful to all participants, as a facilitator to ‘being’ with feelings, as well as being with their thoughts and fostering new ideas associated with the ‘problems’ themselves.

‘. . .problems I tried to change it to thinking about positive things. But that didn't work either because I still felt angry. Digging in to my problems doesn't help. But the mindfulness practice helped me to be able to be with my problem, and relate to it in a different way. . .’ [Participant C]

‘. . . I used to have so much anger and hatred I could not feel or connect with compassion but now I am learning to be with my anger and live with it and also feel compassion.’ [Participant F]

New perspectives

All participants’ responses highlighted new understandings of their difficulties, which were often summaries of the journey of their ‘problems’ and their relationship to them. A new ‘awareness’ seemed to emerge involving patterns of functioning in the moment, what maintained difficulties and how problems impeded individuals from moving forward in life:

‘I dedicated my whole life to my son and I only ever thought about him, always him, my life was consumed by my son and his problems . . . Before, I couldn't concentrate when talking to friends; I was always distracted by my thoughts and worries for my son. I didn't go out or have any social contact for 2 years . . .’ [Participant B]

All participants reflected that the group enabled them to look ‘at things from a different perspective’. This facilitated shifts to a narrative that was more positive, hopeful or understanding and accepting of their current situation and the future. The view of not being alone in experiencing difficulties (identified by six participants) appeared to be powerful amongst the group and this collective experience seemed to provide participants with a sense of strength:

‘Feeling that I am not the only one suffering with my problems is most important thing for me. . .The group is helping me feel that I am not alone with my problems.’ [Participant C]

Five participants also identified a new acceptance of difficulties or past events. There appeared to be a letting go of a fight to change others or themselves, to being able to live with the experience of distress or the problem and still engage with things they valued. There was an evident change in five participants’ sense of personal agency, seeing themselves as more able to ‘deal with’ the difficulties they faced in life. These ‘new understandings’ appeared to foster a feeling of empowerment and increase emotional resilience, which helped to move participants into a position from which they could become unstuck, view other possibilities and experience value in life again.

‘. . . but thanks to these sessions I feel I can deal with my problems – I can live with my problems – and still have some quality of enjoyment to my life. . . The group gave me something: the realization that I can have problems but still enjoy my life’. [Participant A]

Overall, participants’ responses clearly outlined various types of new or reinvigorated perspectives and emotions, which were nurtured from participating in the group. All participants identified various group tasks acting as catalysts (e.g. life compass, value cards exercise), by providing some ‘direction, focus and clarity’, in their reflections and identification of their difficulties, values, new understandings and connection with emotions. In addition, four participants commented on experiencing particular shift moments within the group that illuminated these new views or emotions:

‘. . .I had a moment of eureka, realizing that even when I don't do anything, and don't make a decision – that's still making a choice.’ [Participant B]

These ‘shift’ moments were described as an experience that created the foundation for new possibilities of ‘living life’ despite experiencing difficulties.

Different actions

When reflecting on the experience of the group, six participants started to reconnect with previous values, value-based activities or started something new (i.e. an activity, ‘making time for things’ or strategies to cope with experiences):

‘Group helped me reconnect with the good things in life that I used to do before I became ill – such as buying flowers and exercising more. . .’ [Participant E]

The group appeared to encourage participants to actively do something different associated with their values, interests and enjoyment, or managing difficulties. These activities also linked with new perspectives about being ‘able to deal with stress’ and other difficulties in life, which included having some time to attend to one's own needs.

Theme 3: Reflections/Considerations

Group feedback

All participants often reported a favourable emotion towards attending the group, towards specific sessions or tasks and the environment the group created:

‘. . .I'm very happy to be here.’ [Participant A]

The feedback from all participants suggests that the ACT group was seen as helpful, with four participants interested in more sessions or attending future groups of this kind. All participants expressed that ‘all of it’ or ‘bits of everything’ were useful and there was a suggestion (from five participants) that each session provided something additional to further their understanding. There was a clear interest in building on concepts and further work around emotions, with four participants highlighting compassion and anger. The group seemed to be an enjoyable experience, with participants appreciating the group process, indicating this format as an acceptable intervention.

Interpreting language

Two participants reflected on the difficulties of interpretation for the group. This was associated with preference, a disrupted connection to the group material and other participants, and an inhibited experience of emotional safety when sharing personal events:

‘I did not like the fact there were two languages. Perhaps something was lost in translation or I did not feel connected to the group, there was no flow in conversation, for example I was about to share something sensitive and felt like I was interrupted as it had to be translated . . .’ [Participant D]

This was a significant comment, given the opposing views of the majority of participants who indicated strong attachments and confidence in sharing ‘sensitive’ material within the group. It highlights the complex process of translating and the possible difficulties in cultivating a group alliance within this context. Although the majority of participants did not comment negatively on the effect of translating, it is a valuable consideration given the process of translating in a group setting with multiple people and perspectives.

Use of metaphor

Six participants shared how the use of tasks, involving practical exercises, cultural stories, metaphors and hearing other peoples' experiences and stories were important in being able to think about their situation in a manageable way:

‘I slowly understood how the value cards related to the life compass – how they connected. And that was the most important thing for me.’ [Participant A]

‘The farmer and horse story – there is a necklace in Turkey with words inscribed: good things bring sadness afterwards and bad things bring good things afterwards.’ [Participant E]

This suggests that the use of particular tasks and concepts within ACT was accessible and aided a connection to cultural narratives and new ideas.

Discussion

This pilot project set out to explore the cultural flexibility of the ACT model for Turkish-speaking communities living in an inner London borough. There are no consistent guidelines in the literature for modifying interventions using cultural adaptation frameworks (Rathod, Reference Rathod2017). Thus the acceptability of the adapted ‘Acceptance with Mindfulness and Compassion’ ACT group was based on the extent to which it took into account participants’ social world, cultural values, context and reality, its ability to respond to the therapeutic needs of participants, and cultural relevance, as indicated by patient-reported outcome data. Due to the pilot status of this explorative study, only tentative conclusions can be drawn.

The results demonstrated an overall positive effect of the culturally adapted ACT intervention. Participants showed significant improvements on measures of depression, anxiety and psychological distress. In terms of qualitative data, the thematic analysis suggested that the group was experienced as enjoyable, useful, and would be an accessible and acceptable format for ongoing therapeutic work for Turkish-speaking communities. Although pilot in nature, these results are consistent with the growing body of research suggesting the efficacy of culturally adapted ACT interventions in both client improvements and the acceptability and accessibility across cultures (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez2009; Griner and Smith, Reference Griner and Smith2006; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, White, Ebert, Mays, Nardozzi and Bockarie2016; White and Ebert; Reference White and Ebert2014; Woidneck et al., Reference Woidneck, Pratt, Gundy, Nelson and Twohig2012).

This study reports large effect sizes for the group, which is in line with other studies which indicate that ACT interventions yield between a small-to-large effect size varying by study design, across psychological difficulties and for client groups from ‘non-dominant cultural and/or marginalized backgrounds’ (Forman et al., Reference Forman, Herbert, Moitra, Yeomans and Geller2007; Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Lee, Roemer and Orsillo2013; Johns et al., Reference Johns, Oliver, Khondoker, Byrne, Jolley, Wykes, Joseph, Butler, Craig and Morris2016; Powers et al., Reference Powers, Zum Vörde Sive Vörding and Emmelkamp2009; Vøllestad et al., Reference Vøllestad, Nielsen and Nielsen2012). However, although Hedges’ correction was used to calculate a more conservative effect size due to a small sample size, these Hedges’ measurements (gav or grm) are not completely unbiased in calculating effect size (Cumming, Reference Cumming2012; Lakens, Reference Lakens2013) and wide confidence intervals mean that the findings are interpreted tentatively.

At an individual level, the improvements observed were reliable (between 71.4 and 85.7%), although fewer participants experienced both a reliable and clinically significant reduction in symptomology (between 28.6 and 42.8%). This indicates that the intervention is promising but may need further modification, as there is not a strong enough indication that it leads to clinically significant symptom reduction (scoring below clinical cut-offs for a diagnostic difficulty). However, it is an encouraging start, especially given participants’ reliable symptom reduction within the clinical range and the potential effects this may have on quality of life. Further analysis is required with a larger sample and control group, particularly as null findings should be interpreted carefully in pilot studies due to small sample sizes and regarded as inconclusive as opposed to evidence of an absence of effect (Altman and Bland, Reference Altman and Bland1995; Thabane et al., Reference Thabane, Ma, Chu, Cheng, Ismaila and Rios2010).

From the qualitative analysis, the important themes identified involved noteworthy emotional experiences and changes in one's perspectives on the understanding of their difficulties, the presence of emotions and on future possibilities. Some of these areas appear to reflect ACT aims of changing an individual's relationship to unwanted internal experiences rather than changing the experience itself and promoting psychological flexibility around ‘stuck’ places (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson2012). This appeared to empower individuals in the group to make different choices despite experiencing hardship and identify valued action to engage in within this new view. Secondly, being part of the group appeared to be very powerful (e.g. hearing, connecting and learning from other people's stories), with the significance of these interpersonal processes potentially both in line with the values of collectivist cultures and being facilitators of change (Yalom, Reference Yalom1975). The results suggest that key ACT practices such as mindfulness and acceptance potentially encouraged participants to be more aware, non-judgmental and willing to reconnect to the parts of their lives that matter to them (i.e. values such as perseverance, compassion, forgiveness, belonging and interconnectedness) which also promoted recovery. Furthermore, the group context supported participants to connect with resources in the face of adversity, step towards psychological flexibility and learn more effective ways of responding to distressful internal experiences. These findings support the potential usefulness of the ACT model with Turkish-speaking communities, as well as the supportive function of being part of a group (e.g. not feeling alone) and compassion eliciting exercises (that are related – but not integral to – an ACT model).

Limitations

This is a pilot study and so the robustness of the findings is limited by a number of factors, including a small sample size and lack of control group, which means it cannot fully ascertain whether the ACT interventions were key to the improvements found. However, given the context of the pilot, it provides an opportunity to inspire the provision of culturally competent care in clinical practice. It also warrants larger standardized research utilizing control groups and implementing follow-up measures to determine whether the small improvements found in this study would be maintained and to help to further understand the potential benefits of acceptance-based interventions for Turkish-speaking communities in the UK.

Furthermore, there may have been other effects not measured within the study, e.g. compassion and acceptance, which may be of consideration given that these areas were reflected in the themes identified and within the ACT approach. The measures used in the current study were not ACT specific, but based on psychopathology, which was a pragmatic service related decision based on the requirement to be compliant with the IAPT Framework for assessing outcomes (Gyani et al., Reference Gyani, Shafran, Layard and Clark2013). Future research could include a range of different ACT appropriate measures that would enable us to detect effects in specific ACT domains. Analysis using these measures may also be able to assess potential mechanisms of change, proposed by ACT interventions more widely.

Notwithstanding the above limitations, the findings from this pilot study suggest some value in tailoring ACT to the cultural needs of Turkish-speaking communities in the UK. Given the context of the BME Access Service, it is useful to assess and report on interventions implemented to share and inspire potential clinical practice relating to the accessibility and equity of service provision across diverse populations. Overall, the current study underlines the importance of community consultation and partnership working in the development of culturally responsive and accessible therapeutic interventions for BME communities in East London.

Main points

Based on these preliminary findings, the partnership project has made successful steps in meeting its stated aims of:

• Developing a culturally relevant adaptation of Livheim's (Reference Livheim2014) ACT group therapy protocol.

• Demonstrating that the ACT model may be amenable to successful adaptation across different cultural settings. This finding supports the clinical utility of ACT as a potentially effective, culturally acceptable therapeutic approach for Turkish-speaking communities living in an urban UK setting in supporting psychological well-being.

• Promoting community collaboration and the need to provide culturally relevant and accessible psychotherapies for ethnically diverse populations.

Given the current climate of funding constraints and a drive to develop models of best practice, there is an ever-increasing need to carry out further evaluative research that explores culturally adapted psychological interventions, contextually tailored to the specific needs of different BME communities. The clinical usefulness of the current pilot study may serve to support future partnerships in developing creative and innovative adaptations appropriate to different cultural contexts, as well as encouraging larger research initiatives. This may further improve the cultural competency of service provision, leading to more equitable access to talking therapies, enhanced service user experience and better recovery outcomes for BME communities across both statutory and voluntary sector organizations in the UK.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Derman as the partnership organization for their contribution to this project and assistance with community consultation, recruitment and delivery of the group, and Feyza Özcan Balaban for additional language support. Thanks are due to Dr Shanaya Rathod for helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. Finally, thanks to all the participants for their involvement.

Ethical statement

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA. This project constituted service-related research that evaluated an aspect of service provision not requiring ethical approval.

Conflicts of interest

Aradhana Perry, Chelsea Gardener, Joseph E. Oliver, Çiğdem Taş and Cansu Özenç have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Financial support

This project was supported by the City and Hackney Clinical Commissioning Group Psychological Therapies Alliance in East London.

Learning objectives

(1) To explore the cultural applicability of the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) model to psychological distress in non-western Turkish-speaking communities.

(2) To highlight the importance of community consultation and partnership working with third-sector organizations in the development of culturally relevant and accessible therapeutic interventions.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.