6.1 Pick a Century

See if you can identify which of the following comes from the twentieth century, and which from the twenty-first.

1. Students continue to arrive on college campuses needing remediation in basic writing skills.

2. What’s happening in the United States is that the universities have, in effect, given up on the [secondary] schools.

3. Many high school teachers have simply stopped correcting poor grammar and sloppy construction.

If you guessed a reverse order, you are correct. The first passage appeared in The New York Times in 2017, while passage two, also from the twenty-first century, appeared in Australia’s The Age in 2007. Passage three appeared in 1975 in the famous Newsweek article you read about in myth 5.

Across fifty years, the passages repeat a twofold lament: Student writers are showing up to college unprepared, and secondary schooling is to blame. If secondary schools did their job, college students would not need any help with correct writing in college. Writing instruction, it follows, is a burden that colleges should not have to bear.

In these complaints, we can see earlier myths at work. The first five myths give us a limited version of correct writing, regulated by schools and tests, which most students can’t do. This myth further suggests that secondary schools are to blame. If only secondary teachers would teach correct writing, so this myth goes, it would be mastered before students go to college.

One of two presumptions underpins this myth. Either secondary and postsecondary writing are sufficiently similar that students who learn secondary writing will meet college requirements easily. Or, if secondary and college writing are different, then intelligent writers will easily adapt to meet new college demands after secondary writing. Either way, the message is: Writing development is linear and finite, basically intact by students’ late teens.

In a way, writing should be mastered in secondary school is not a separate myth, but a different, mythical way that previous details come together. We’ve seen much of this myth’s origin story already, in other words, because we’ve seen how written English exams, designed and interpreted by university educators, shaped early ideas about secondary writing. We also know from earlier myths that different tasks lead to different writing choices, so we know we have to consider typical secondary and college writing tasks to consider this myth. We will bring these threads together to fill out this myth’s context.

6.2 Context for the Myth

6.2.1 Early university educators and tests define secondary writing ability

Several myths so far show how university leaders and tests influenced early ideas about secondary learning. Horace Mann’s tests in the 1840s and 50s suggested secondary student ability should be measured through individual, timed writing and correct writing errors, then used in public rankings and college admissions. England’s local examinations in the 1850s meant that university educators defined secondary student writing achievement, even for those students not pursuing university education. Harvard examiners, beginning in the 1870s, designed written English exams and wrote about the results in persuasive reports. Those Harvard reports fueled the establishment of mandatory general English composition courses designed to remediate secondary writing, first at Harvard and later at hundreds of other institutions.

Both England’s local examination reports and the Harvard reports directly addressed secondary student writing. Regarding the first local examinations in 1858, Cambridge examiners remarked that “little attempt had been made by [secondary] instructors to excite the interest of their pupils.” The examiners’ solution, as we saw in myth 4, included “regularly recognised examinations.” In the Harvard examiner report of 1892, B. S. Hurlbut expressed alarm at “the number of persons who are sent out annually from our high schools unable to express their thoughts with a fair degree of clearness, unable to write passably good English,” which led him to “but one conclusion…: there is something fundamentally wrong in the method of teaching English in the secondary schools.” In 1896, Harvard’s three earliest English examiners (Hill, Briggs, and Hurlbut) underscored their conclusion, also the conclusion of the Committee of the Board of Overseers, “that the Secondary Schools need to pay more attention to English.”

Reports like these communicated several assumptions at a time when education and written English literacy were expanding, and before the time that secondary examinations became standardized in the twentieth century. These assumptions overlap and follow from one another (picture a Russian assumption doll), but we can identify them one at a time. One assumption was that university educators knew what it meant for secondary students “to write passably good English,” and another was that timed, externally-designed tests could measure it. A third assumption was that the end of secondary school was a definitive time for measuring said English. We’ve seen these assumptions reflected in exams in earlier myths: any college entrance exam task, on Thucydides, Mr. Darcy’s Courtship, or otherwise, implies that a timed writing task at the end of secondary learning can represent the student’s past secondary writing, and the student’s future writing ability. Exam tasks like these, particularly with high stakes such as secondary graduation or college admission, also make it so that brief writing tasks are essential for secondary student success. We will see related ideas about writing tasks and exams persist in this myth’s contemporary context, where we turn next.

6.2.2 Secondary Writing Tasks Tend to Be Brief, Persuasive, and Rigidly Organized

6.2.2.1 Secondary Writing Is Brief

Educational research across the US, UK, and Australia shows that many secondary students write brief responses in school. Genrally, they do not regularly write more than a paragraph at a time or regularly practice substantial analysis or interpretation.

Secondary English courses sometimes serve as the exception, offering more extended writing and instruction than other courses, though this trend places pressure on secondary English teachers and can limit writing instruction across the curriculum. Secondary students report that they write most in English classes, even though they would benefit from writing guidance across all of their courses.

6.2.2.2 Secondary Writing Includes Few Genres

When they write more than a few sentences, secondary students often write in a handful of genres only. In English courses, brief tasks include timed, on-demand writing, especially in the past decade, while in other subjects, brief writing tends to appear in worksheets or one-sentence questions. Particularly in standardized writing exam tasks like those in myth 4, secondary students tend to write timed argumentative, analysis, or narrative essays (sometimes emphasizing literature) more often than summaries, case studies, or reports. We’ll look at a few contemporary examples.

For the UK GCSE, two recent tasks required argumentative writing: Students wrote a persuasive letter to a newspaper about their view of whether the UK drinking age should be increased to 21, and students wrote a “lively review” of a film, TV programme, or book. Less overtly persuasive tasks include the Cambridge A Levels English examples in myths 4 and 5 (analyzing a speech, and writing a diary entry).1 Those tasks required reading argumentative writing but responding with analysis and narrative, which are less argumentative – and further right on the continuum – than open letters.

In the US, standardized exams regularly emphasize persuasive arguments. For the ACT in 2018, students needed to write “a unified, coherent essay about the increasing presence of intelligent machines” and were told to “clearly state your own perspective on the issue and analyze the relationship between your perspective and at least one other perspective.” Similarly, the 2008 California High School Proficiency Examination (CAHSPE) included this task: “Some people believe that high school classes should not begin before 9:00 a.m. Do you agree or disagree? Write an essay clearly explaining your opinion.” A similar example, the 2016 Common Core State Standards (CCSS) Argument/Opinion task, asked students to write an essay in response to the question, “Should your school participate in the national ‘Shut Down Your Screen Week’?”. Although the CCSS includes both “persuasive writing” and “informative/explanatory writing,” both emphasize the writer’s argument in the task and the evaluation criteria.

Australia’s STAT tasks, as we saw in myth 4, also emphasize persuasive argumentative essays;, for instance, about a public issue (the role of education) or personal sense (romance versus friendship). Finally, for earlier secondary students, Australia’s NAPLAN exams include persuasive tasks, such as “Some people think the country is the best place to live. Others think it is better to live in a city. What do you think? … Write to convince a reader of your opinions.”2 As we saw in myth 5, there can be good reasons to narrow criteria according to what writing needs to do in a particular context. Along these lines, there can be good reason to limit genres. But, as we also saw in myth 5, limited does not make something correct, and student practice with different genres goes beyond the domains and parameters of standardized tests.

6.2.2.3 Secondary Writing Follows Template Organization

Secondary students are often introduced to template formulas to organize their writing. For example, a template in the UK is “PEEL,” or point, evidence, evaluation, link. A common template in the US is the five-paragraph essay, with an introductory paragraph ending in a thesis, three main idea paragraphs addressing one example each, and a concluding paragraph that restates the thesis. These templates are often used in standardized exam preparation, because they can be used quickly in timed essay writing.

6.2.3 Exams Impact Secondary Teaching Conditions

The long reach of standardized exams extends beyond writing tasks and templates, to secondary curricula and teaching as well. Frustrated teachers report that teaching is devalued because of “heightened pressure to perform on standardized testing” and that officials have placed more importance on data and results than on students’ needs and learning.3 Teachers face pressure to make time for exam practice and to tailor their teaching to templates used in standardized writing exams.

Indeed, even secondary teachers who love their students are often driven away from the profession by standardized tests. In the UK and Australia, around 30 percent of schoolteachers leave within five years.4 In the US, more than 50 percent of teachers quit teaching before retirement.5 Meanwhile, education jurisdictions such as Finland, which place less emphasis on standardized tests, report teacher attrition rates below 5 percent.

In a negative cycle, standardized tests and teacher attrition fuel one another. Standardized tests and the use of test results in top-down school policies are common reasons that secondary teachers leave teaching. In turn, this makes working conditions worse, because high teacher dropout and low student achievement often fuel one another.

6.2.4 Secondary and Postsecondary Writing Are Different

New college students encounter several important differences between secondary and postsecondary writing. While secondary writing often emphasizes timed and argumentative essays, postsecondary writing often requires sustained inquiry and substantial revision over days or weeks. Rather than overt arguments, postsecondary writing is usually expected to be open-minded, written for a reader looking for information rather than opinions. And rather than only persuasive or narrative essays, postsecondary writing regularly requires explanatory genres such as reports and research reviews. Indeed, the farther along they are in college, the less likely students are to write argumentative essays.

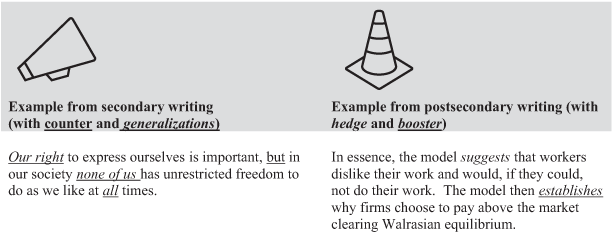

This brings us, again, to the fact that different tasks mean different writing. Secondary and postsecondary tasks are different, so their writing patterns are different. Secondary writing, often in response to persuasive argumentative tasks, includes significantly more boosted, generalized, interpersonal language patterns. Postsecondary writing, often in response to explanatory tasks, includes more hedged, informational language patterns. Developmental maturity may contribute to more hedges and fewer generalizations in college writing, since postsecondary students have more education and life experiences than secondary students. Still, the differences go far beyond maturity, as evidenced by divergent patterns in different writing tasks even at the same level. Secondary writing is different enough from postsecondary writing that it is no simple feat to transition between the two, even as this myth suggests otherwise.

6.3 The Myth Emerges

Bolstered by earlier myths, and without clear attention to differences between secondary and postsecondary writing, this myth emerges. With it comes a limited view of writing development.

6.4 Consequences of the Myth

6.4.1 We Limit Writing Development

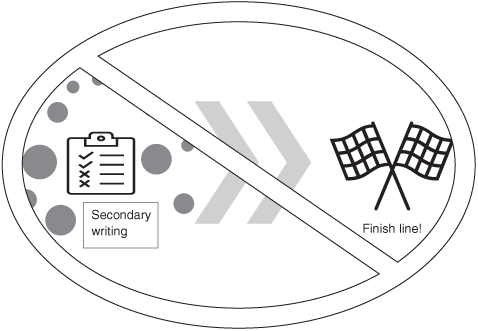

The myth that writing should be mastered in secondary school suggests that writing development is linear and finite. Visualized in Figure 6.1, this view of writing development implies a line with an end point at the end of secondary school, as though writing is learned once and for all by then (see Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Writing development is not a line

This larger consequence entails more specific consequences listed in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Consequences of myth 6

| Once we believe Writing should be mastered in secondary school, then… | … We get (more) confusing references to grammar |

| … Students don’t have explicit support for writing transitions | |

| … We misunderstand college writing courses | |

| … We miss opportunities for writing support |

6.4.2 We Get (More) Confusing References to Grammar

As in earlier myths, several headlines related to this myth use terms such as spelling, grammar, and writing interchangeably. Some statements specifically blame secondary teachers for students’ spelling, punctuation, and capitalization, but they refer to these choices as grammar or writing. Rarely are these terms explained or separated.

For instance, spelling is a headline problem in the 2007 news article noted in the opening passages. Titled “Can’t write can’t spell…,” the article argues that Australian students and teachers “fail to grasp the English language.” This leads to “the big question,” the article says, which is really a series of questions:

[W]ho is ultimately responsible for those teachers and students who fail to grasp English language somewhere along the way? Is it the education system for not teaching the teachers; the teachers’ approach to teaching; an evolving English curriculum that never quite attains perfection; students’ own lack of aptitude; or their need for tailored teaching?

The article speculates that “there has been less emphasis placed on grammar and language structure over the past 10, 15 years in teacher training.”6 The article does not aim to explain or illustrate what is missing, or what grasping English language means. It does not, for instance, offer examples for “grammar, punctuation, and spelling,” beyond stating they are related to the ability “to write sentences.”

In another example, Maclean’s coverage of Canadian university language entrance exams is summarized in a 2010 article titled “University students can’t spell,” with the subheading “Profs say high schools aren’t teaching grammar.” Yet the “writing horrors being handed in” appear to be related to conventions, especially spelling, rather than grammar: “emoticons, happy faces, sad faces, cuz [rather than because]” as well as a lot written as one word and definitely spelled with an a (defanitely).7 Since emoticons are perceptually salient but proportionally rare, we might well wonder how often these errors are taking place. But we’ll get to that in myth 8.

In one more example, “Cult of Pedagogy” blog author Jennifer Gonzalez titles a 2017 post “How to Deal with Student Grammar Errors” and notes that in using the term grammar, she is “broadly referring to all the conventions that make writing correct: spelling, punctuation, usage, capitalization, and so on.”8 As we’ve seen in other myth chapters, this use of grammar to refer to conventions or usage preferences – rather than what is grammatically possible and meaningful in English – is common. In this myth, sources furthermore imply that secondary students can learn grammar once and for all, before college courses.

6.4.3 Students Don’t Have Explicit Support for Writing Transitions

Because different tasks require different writing, it is not easy to transition from one task to another. It is, specifically, difficult to transition between secondary and college writing, each of which entails its own contexts and tasks. Students who have practiced argumentative secondary essays, for instance, will not automatically adapt (or disregard) relevant writing patterns in college writing. Indeed, that is why linguists who study academic writing variation say that students should write a range of writing assignments, not just argumentative essays, in high school and early college.

This myth makes the transition between secondary and postsecondary writing harder, because it assumes secondary students should be able to move from one part of the continuum to another without support. The myth glasses justify paying little explicit attention to similarities and differences between secondary and college writing.

Without attention to similarities and differences between secondary and college writing, secondary writing templates can inhibit rather than help students. Templates such as the five-paragraph essay, for instance, are valued in exam culture because they are efficient to evaluate. They may also provide useful scaffolding and help reduce anxiety for secondary students when they are new to writing multi-paragraph essays. But unless those students explore what makes cohesion in a five-paragraph essay different than cohesion in a college paper, the template can thwart rather than help them when they get to college.

6.4.4 We Misunderstand College Writing Courses

This myth makes us misperceive college writing as remediation, instead of ongoing writing development. If we believe that writing can be mastered in secondary courses, we can believe college writing courses are catch-up classes, or classes for only some students, rather than classes that help all students transition to new writing practices.

College composition courses are often misperceived along these lines. As we saw in this myth’s context, composition courses are especially prevalent in the US, where they are required for most college students based on the influence of Harvard’s late nineteenth century composition exams and courses.

The use of secondary courses and standardized exams to exempt students from college composition courses similarly suggests secondary writing can stand in for postsecondary writing. One example is the common practice of using secondary advanced placement (AP) English exam results in this way. Another example is the use of standardized exams taken before college, such as the SAT or Accuplacer, to exempt students from college writing courses.9

Assigning English for Academic Purposes (EAP) courses only to non-native English writers reinforces these misconceptions. EAP writing courses provide explicit support in postsecondary writing. But they are commonly required only for international or additional-language students. This practice sustains the false idea that native English students do not need explicit writing instruction as they take on new postsecondary tasks.

6.4.5 We Miss Opportunities for Writing Support

When we view writing as linear and finite, we make struggles with postsecondary writing the fault of students and their prior schooling. We miss the point that postsecondary writing tasks are new for new college students, and we miss opportunities to draw explicit attention to similarities and differences between one part of the writing continuum and another. We miss the possibility of EAP or other explicit writing instruction for all kinds of students. Likewise, in cases where some students “test out” of college writing courses, we miss chances for more writing practice and feedback as students encounter new writing tasks.

The related myth that writing should be developed in English courses places undue pressure on English departments and instructors. It often overlooks the fact that disciplinary training in literature is not the same as training in English language. In turn, we miss opportunities to raise students’ conscious awareness of how writers in different disciplines use language similarly and differently.

6.5 Closer to the Truth

6.5.1 Spelling Memorization Is Different from Writing Development

To get closer to the truth, we can first circle back to spelling, in this case, secondary spelling. As we saw in myth 1, conventional English spelling is an awesome mess dating back to the fifteenth century, and it requires memorization and practice. Memorizing spelling rules is not the same thing as practicing and developing writing, so references to grammar and writing that really mean spelling and punctuation are misleading. Spelling can also be strongly influenced by timed writing in standardized exams.

6.5.2 Writing Development Is a Spiral, not a Line

As long as writers keep writing, their writing development continues. In the process, some writing choices are harder or easier depending on the context and task. For both children and adults, choices that seem simple in a familiar writing task are harder in an unfamiliar or high-stakes task. Put another way, students writing their first few college research papers will not be able to focus equally on all their writing choices, because they need a lot of bandwidth for any topic and genre details that are especially unfamiliar.

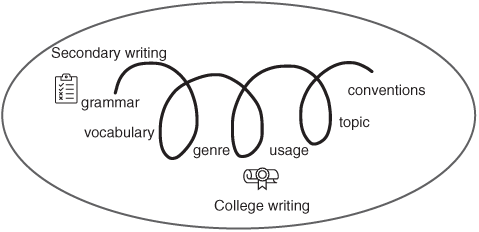

In sum, writing development is a spiral (as in Figure 6.2) rather than a line (recall Figure 6.1). And in the spiral of writing development, the different elements – topic ideas, organizational choices, vocabulary, and so on – do not come together at once. As we develop as writers, they come together at different times, on a spiral like the one in Figure 6.2. New writing tasks and contexts require practice, again and again, to bring everything together.

Figure 6.2 Writing development is a spiral

Thus headlines misrepresent writing development when they suggest that secondary students who struggle with college writing have missed something. Closer to the truth is that writing development is a continual spiral, across the full lifespan. Even successful writers, at all levels, must write repeatedly in new contexts and tasks to fulfill new writing expectations.

6.5.3 College Courses Demand new Writing

Painting college writing courses as remedial doesn’t help, because it suggests that writing development can be, and should be, intact at the end of secondary school. The 2007 news article in the opening passages, for instance, suggests US composition courses exist because universities have “given up” on secondary education. Claims like these place responsibility on secondary schools and students rather than on ongoing writing resources in all schools and workplaces.

Closer to the truth is that college writing is different than secondary writing. This isn’t to say that all college composition courses are effective. As you can already tell, I’m of the mind that such courses should spend more time exploring language patterns on a wider writing continuum. But it is to say that labeling college writing as remedial is not accurate, nor useful for students or instructors, because college writing is new for new college students.

To help students, college writing instruction can support language exploration that draws explicit attention to similarities and differences between secondary and postsecondary writing. Along similar lines, because college EAP courses support writing transitions through explicit instruction, they can help support students from all language backgrounds transition between secondary and college writing. We should not assume that such transitions are neutral nor equally valuable for different students. But we can offer more bridges between different kinds of writing to make the transitions better supported and more transparent.

6.5.4 We Need to Build Metacognitive Bridges

Better alignment across secondary and postsecondary writing would make the transition easier between them. But bridges between the two can help regardless. Even with their current differences, explicit attention to their similarities and differences can help students transfer their writing knowledge from secondary to postsecondary writing.

Writing metacognition, which we can think of as writing analysis and self-awareness, specifically helps writing transitions. In particular, writing research shows two kinds of metacognition support writing transitions:

Analysis of relevant writing strategies

Awareness of some relevant steps and prior experiences

This would mean, for instance, that a college student writing a college Biology lab report for the first time would need:

Attention to strategies typically used in Biology lab reports

Attention to experiences they can draw on, and what they need, to make choices regarding strategies typically used in Biology lab reports

We can continue this example by using the writing continuum. Writing metacognition would be helped by attention to typical strategies in Biology lab reports – typical cohesion strategies (e.g., formatted sections and rhetorical moves), typical connection and focus strategies (e.g., directions to tables or calculations; sentence subjects emphasizing experiment steps), and usage norms (e.g., correct writing spelling and usage preferences, and subject-verb-object order used across the continuum). It would also be helped by attention to how these strategies are similar or different than ones the writer had used before. Transitioning between old and new writing tasks is helped by this kind of attention to similarities and distinctions, both in individual student reflections and in students’ discussions with other students.

Because most writers have to write across the continuum, metacognition across different writing is more useful than mastery of one kind of writing. Students can analyze strategies across the continuum, in all kinds of writing they do, in order to metacognitively reflect on what makes distinct writing tasks different and similar.

6.5.5 Language Patterns Provide Bridges

We’ll build metacognitive bridges here by noting differences between secondary and postsecondary writing. This is especially fun for me (nerd alert), because I’ve spent the past decade analyzing language patterns in secondary and postsecondary writing using large databases of student writing.10

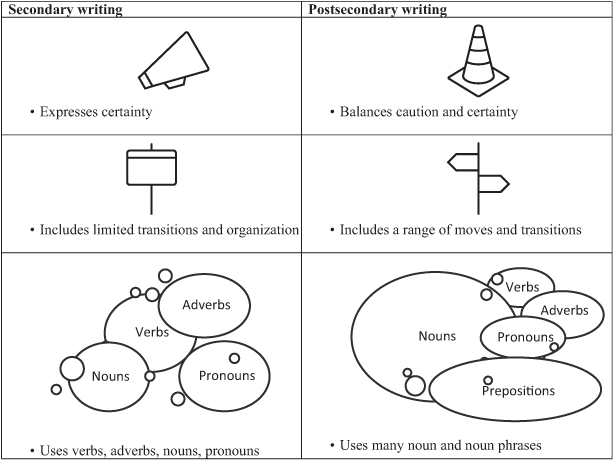

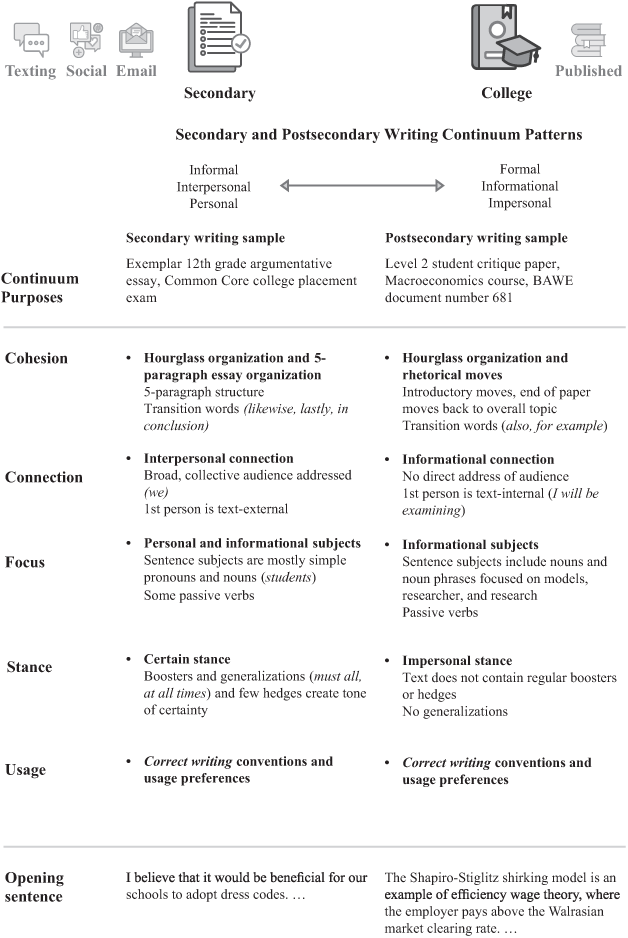

In particular, I’ve found three language patterns, shown in Table 6.2, that distinguish college writing (and published academic writing, too) from secondary writing:

Civility versus certainty: Secondary writing favors certainty and counters, while college writing balances caution and certainty and concessions and counters.

Cohesion versus few transitions: Secondary writing includes few transitions, while college writing shows a range of transition words and moves for leading readers.

Compression versus few noun phrases: Secondary writing includes few noun phrases and a mix of nouns, verbs, adverbs, and pronouns, while college writing favors dense noun phrases.

Table 6.2 Secondary and postsecondary writing patterns

Table 6.3 Secondary and postsecondary stance patterns

Table 6.4 Secondary and postsecondary cohesion patterns

These patterns appear in Table 6.2, and we’ll address them one at a time, with example passages before adding them to the writing continuum.

6.5.5.1 Secondary Writing Expresses Certainty, while Postsecondary Writing Balances Caution and Certainty

Postsecondary writing includes regular cautious choices such as hedges (perhaps or might) and concessions (Author X is correct that…), along with choices that show certainty, such as boosters (definitely or demonstrates) and counters (nonetheless, Author X does not account for…).

By contrast, secondary writing tends to include more boosters and counters, and fewer hedges and concessions. A college instructor used to postsecondary writing can find secondary writing overstated or aggressive as a result.

A balance of caution and certainty can be what instructors mean when they say correct writing is “impartial” or “objective.” A secondary student accustomed to using boosters in persuasive secondary writing or interpersonal social media writing may perceive these as part of emphasizing their ideas regardless of what they are writing.

When secondary students express a lot of certainty, this doesn’t mean they can’t write. It means they have less practice writing farther to the right on the continuum, with a balance of caution and certainty. We’ll add this information to our language continuum below, as part of stance and connection patterns.

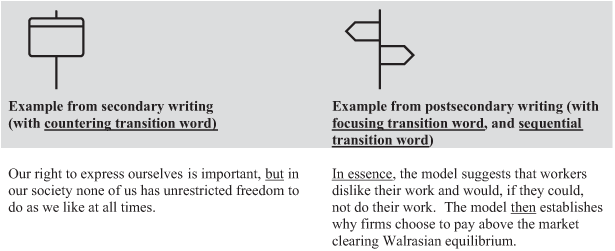

6.5.5.2 Secondary Writing Uses a Few Cohesive Strategies, while Postsecondary Writing Includes Diverse Cohesion11

Cohesion indicates a piece of language is a unified whole, instead of a collection of unrelated words or sentences. Postsecondary writing includes many forms of cohesion, from cohesive words (in other words, however) to cohesive moves (introductory moves, known-new moves).

By contrast, secondary writing uses a narrower set of cohesive strategies. Secondary writers especially use counters such as but and however, and more rigid, template moves, such as PEEL (point, evidence, evaluation, link) or paragraphs in five-paragraph essays.

A range of cohesive ties and moves is often what college instructors mean when they say correct writing is “well organized.”

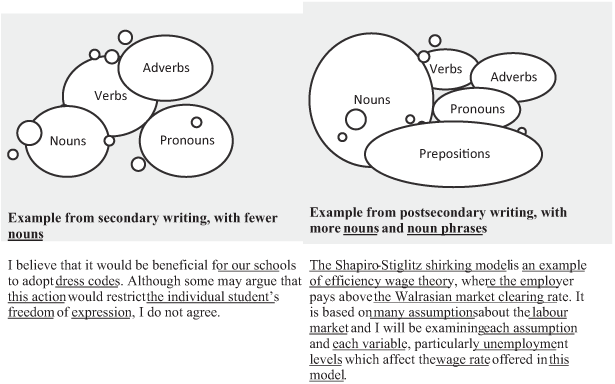

6.5.5.3 Secondary Writing Uses Verbs, Nouns, Pronouns, and Adverbs, while Postsecondary Favors Noun Phrases

Most of the writing on the continuum, including secondary writing, favors a balance of parts of speech (or lexical categories). Alternatively, as we know from myth 1, the far right of the continuum favors nouns, in phrases that include additional prepositions and nouns. Linguists call this compression, because it compresses information into phrases, rather than spelling it out in longer clauses.12 Here’s an underlined example of a dense noun phrase: College writing expected in postsecondary courses and characterized by compressed phrases can be challenging for new students.

Like other writing on the right of the continuum, postsecondary writing uses a lot of dense noun phrases and independent clauses. Secondary writing includes simpler nouns, as well as more verbs and dependent clauses beginning with words like when and because. These contrasting noun patterns are shown in Table 6.5.

Table 6.5 Secondary and postsecondary noun patterns

Compression can be what instructors mean when they say that correct writing is “concise” and “formal.”

6.5.6 Secondary and Postsecondary Writing Are on a Continuum

To bring these together, we’ll add discussion of cohesion, civility, and compression patterns to secondary and postsecondary writing on the continuum shown in Table 6.6.

Table 6.6 Secondary and postsecondary writing continuum

In this case, we can see that both secondary and postsecondary writers fulfill the continuum purposes of cohesion, connection, focus, stance, and norms. But they do so in different language patterns, in response to different tasks and contexts. Thus secondary writing tends to be more informal, personal, and interpersonal, while postsecondary writing tends to be more formal, impersonal, and informational. These are overall patterns, which may vary (or slide along the continuum) depending on the writers, tasks, and contexts, but they allow us to draw explicit attention to similarities and differences.

More paragraphs of these secondary and postsecondary examples appear below. As in earlier chapters, marginal notes and annotations draw attention to cohesive moves and transition words (in bold), connection markers [in brackets], passive verbs [[in double brackets]], hedges in italics, and boosters and generalizations in bold and italics.

6.5.6.1 Secondary Writing Example

[I] believe that it would be beneficial for our schools to adopt dress codes. Although some may argue that this action would restrict the individual student’s freedom of expression, [I] do not agree. [Our right to express ourselves] is important, but in [our society none of us] has unrestricted freedom to do as [we] like at all times. [We] must all learn discipline, respect the feelings of others, and learn how to operate in the real world in order to be successful. Dress codes would not only create a better learning environment, but would also help prepare students for their futures.

Five-paragraph hourglass essay cohesion, personalized connection, certain stance:

The writer opens with an introductory paragraph with a thesis, using the first person to offer a personalized reaction and boosted, generalized claims

Perhaps the most important benefit of adopting dress codes would be creating a better learning environment. Inappropriate clothing can be distracting to fellow students who are trying to concentrate. Short skirts, skimpy tops, and low pants are fine for after school, but not for the classroom. T-shirts with risky images or profanity may be offensive to certain groups. Students should express themselves through art or creative writing, not clothing. With fewer distractions, students can concentrate on getting a good education which can help them later on.

Informational focus, balanced stance:

The writer moves to body paragraph and idea 1, which is focused on learning distractions and includes hedged and boosted claims

Another benefit of having a dress code is that it will prepare students to dress properly for different places. When [you] go to a party [you] do not wear the same clothes [you] wear to church. Likewise, when [you] dress for work [you] do not wear the same clothes [you] wear at the beach. Many professions even require uniforms. Having a dress code in high school will help students adjust to the real world.

Explicit cohesion and interpersonal connection:

The writer moves to body paragraph and idea two, with explicit transitions and several uses of the second person

Lastly, with all the peer pressure in school, many students worry about fitting in. If a dress code (or even uniforms) were required, there would be less emphasis on how [you] look, and more emphasis on learning.

Explicit cohesion and interpersonal connection:

The writer moves to body paragraph and idea three, with an explicit transition and more use of second-person pronouns

In conclusion, there are many important reasons our schools should adopt dress codes. Getting an education is hard enough without being distracted by inappropriate t-shirts or tight pants. Learning to dress for particular occasions prepares us for the real world. And teens have enough pressure already without having to worry about what they are wearing.

Explicit cohesion and certain stance:

The writer explicitly moves to the conclusion and closes with boosted claims

6.5.6.2 Postsecondary Writing Example

The Shapiro-Stiglitz shirking model is an example of efficiency wage theory, where the employer pays above the Walrasian market clearing rate. It [[is based on]] many assumptions about the labour market and [I will be] examining each assumption and each variable, particularly unemployment levels which affect the wage rate offered in this model. [I will show] how the model establishes an equilibrium and also what empirical evidence there is to support to support it.

Explicit cohesion, informational stance:

The writer uses introductory moves (territory, niche, writer contribution to the niche) to open the paper, and the paragraph includes text-internal first-person and noun phrases that focus on information

The Early Classical economists believed that in market equilibrium, unemployment did not exist and that the markets cleared. If unemployment did exist, it was purely voluntary and caused by wage rigidities. Another theory of unemployment suggested is one of efficiency wages which offers an explanation of involuntary unemployment, even at equilibrium. The ShapiroStiglitz shirking model is one such an example. In essence, it suggests that workers dislike their work and would, if they could, not do their work. The model then establishes why firms choose to pay above the market clearing Walrasian equilibrium.

Explicit cohesion, informational connection, impersonal, balanced stance:

This paragraph includes development moves (topic, example, analysis), focuses on information, and uses boosters and hedges

The shirking model [[is founded upon]] many assumptions, of which the first one is that workers dislike their work and if the firm was completely unable to monitor their work, they would choose not to do it. The second assumption is that workers either shirk, or they work at effort level e (i.e., it is a discrete variable); there is only one level of effort and this cannot be higher or lower. If they do shirk, the model assumes that they [[are dismissed]].

The other main assumptions are that all workers and firms are identical; the probability of being dismissed due to reasons other than disciplinary ones, b, is 1 in the long term; and the level of unemployment benefits given out, w, is treated as an exogenous variable.

It has always been difficult to observe each individual’s effort to ensure that they do not shirk, but in more recent times it has proved increasingly so. Teamwork, use of initiative and flexibility have become more important skills in the workplace, but the quantity of effort [[put into these]] is very difficult to measure in comparison to, for example, the speed of a production line. …

Explicit cohesion, impersonal, boosted stance:

The writer uses transitions to signal new assumptions and several boosters to convey a certain stance focused on information

Judging from exemplary student writing such as these two examples, shifting from secondary to postsecondary writing entails moving from more interpersonal, informal, personal writing to more informational, formal, impersonal writing. Students accustomed to focus, cohesion, connection, stance, and usage in secondary writing or in any writing farther to the left on the continuum will not necessarily have practice or familiarity with reading and writing postsecondary writing. These are reasons why secondary standardized writing exams cannot represent how secondary students will do in their postsecondary writing.

Closer to the truth is that correct writing reinforced by myths 1 through 5 is not learned once, in secondary school, and then finished. Secondary writing is different than postsecondary writing. Each one requires practice, and moving between them requires transitioning between the patterns in each one.

Closer to the truth is also that many educators who work with student writers – designing writing assignments, evaluating writing, and offering feedback – have not explicitly studied differences between secondary and postsecondary writing. They may not have studied connections between the writing their students know and the writing they expect from them, making it harder for them to build metacognitive bridges for students.

Closer to the truth is that writing development is not linear or finite. It is an ongoing spiral, in which different writing knowledge comes together at different times when writers encounter new tasks. Closer to the truth is that we can create metacognitive bridges through explicit attention to similarities and differences across the writing continuum. These bridges can help support transitions between parts of the continuum.

We can start by not assuming that writers will easily transition from one writing context or task to another. And we can continue by exploring language patterns within and across contexts.

The next chapter addresses our penultimate myth, that college writing ensures professional success. That myth shares a similar premise with this one: that writing used on one part of the continuum will easily translate to another part of the continuum. We are more ready to recognize that myth after this one. We can see how the assumption that writing development is linear and finite fuels both myths, and we can recall that transitioning from one writing context to another is challenging, particularly without bridges.