This article emerges from concerns that without understanding the human workplace dynamics of aid, poverty reduction may remain an elusive goal (Narayan, Pritchett, & Kapoor, Reference Narayan, Pritchett and Kapoor2009). Dominance, justice and identity have been mooted as the human dynamics most critical for optimizing the effectiveness of development work (MacLachlan, Carr, & McAuliffe, Reference MacLachlan, Carr and McAuliffe2010). This study assessed the relative contributions that host national aid workers’ perceptions of these three issues make to local capacity-building, operationally defined as the sense of empowerment among host national employees in development projects (Spreitzer, Reference Spreitzer1995).

Empowerment

There are four key cognitive assessments involved in the empowerment process (Thomas & Velthouse, Reference Thomas and Velthouse1990); competence (self-efficacy in relation to your job); self-determination (where you locate the origin of your actions); meaning (the value you place on a work goal); and impact (the sense of making a difference in your workplace). These four components of empowerment were empirically affirmed through confirmatory factor analysis by Spreitzer (Reference Spreitzer1995) on two separate American samples of employees (N = 393; N = 128). This conceptualisation of empowerment is the most widely cited model of psychological empowerment in the literature (Spreitzer, Reference Spreitzer, Cooper and Barling2008), with overall Cronbach's alphas ranging from .62 to .97.

The Western context in which much of the theorising of empowerment has taken place may limit its generalisability to other settings. Several studies in non-Western settings, including the Philippines, have failed to report the adequacy of the four-dimensional model of empowerment (Avolio, Zhu, Koh, & Bhatia, Reference Avolio, Zhu, Koh and Bhatia2004; Ergeneli, Sag, Ari, & Metin, Reference Ergeneli, Sag, Ari and Metin2007; Hechanova, Alampay, & Franco, Reference Hechanova, Alampay and Franco2006). However, factor analytic support has been found in China (Aryee & Chen, Reference Aryee and Chen2006; Hui, Au, & Fock, Reference Hui, Au and Fock2004). Due to the lack of published research exploring empowerment in non-Western contexts, the present study seeks to explore (a) whether Spreitzer and colleagues’ conceptualisation of psychological empowerment is valid in the Philippines; and (b) which contributing constructs matter most in building local employee empowerment in aid organisations in the Philippines.

Perceived Social Dominance

The first of the antecedents considered in the present study is perceived social dominance. Perceptions of social dominance arise where hierarchical social relations occur. Those with power may both devalue target others and view themselves more favourably (Kipnis, Castell, Gergen, & Mauch, Reference Kipnis, Castell, Gergen and Mauch1976). Ironically (given the egalitarian aspirations of many in the aid sector), these outcomes are common for expatriates in aid contexts (MacLachlan, Reference MacLachlan1993). Further, expatriate-local relations in aid organisations may also be understood in these terms (MacLachlan et al., Reference MacLachlan, Carr and McAuliffe2010); expatriates commonly form the hegemonic group, while locals, as a result of colonisation and historical racism, are often lower down the hierarchy. Consequently the present study focuses on the perceptions of, and impacts of social influence upon, local employees.

In hierarchical organisations, some people seek to establish and maintain the hierarchy through discriminative behavior (Sidanius & Pratto, Reference Sidanius, Pratto, Sniderman, Tetlock and Carmines1993). Such behaviour is likely to cause perceptions of social dominance and consequently lower levels of empowerment for those lower down the hierarchy (Essed, Reference Essed, Goldberg and Solomos2002). Expatriates may unconsciously maintain the status quo (dominating the hierarchy) rather than empowering local employees. However, employees at all levels of an organisation may hold attitudes that either strengthen (hierarchy-enhancing) or work against (hierarchy-attenuating) social dominance (Sidanius, Pratto, van Laar, & Levin, Reference Sidanius, Pratto, van Laar and Levin2004).

Consequently, where perceptions of social dominance in the organisation are high, levels of empowerment are likely to be low (Coates & Carr, Reference Coates and Carr2005; Pratto et al., Reference Pratto, Liu, Levin, Sidanius, Shih and Bachrach2000). It is worth noting that the present focus on perceptions of social dominance at the institutional level is at least partly a response to suggestions that research into social dominance has disproportionately focused on the individual (Sidanius & Pratto, Reference Sidanius and Pratto2003; Turner & Reynolds, Reference Turner and Reynolds2003).

However, it is unclear how social dominance might operate in different cultural settings. Individual social dominance orientation was found to be relatively consistent across samples taken in Canada, Taiwan, Israel and to a lesser extent China, in correlating with sexism, ethnic prejudice and conservatism (Pratto et al., Reference Pratto, Liu, Levin, Sidanius, Shih and Bachrach2000). Other research supported cross-cultural validity in Sweden, Australia and Russia (Sidanius & Pratto, Reference Sidanius, Pratto, Sniderman, Tetlock and Carmines1993; Sidanius, Pratto, & Brief, Reference Sidanius, Pratto and Brief1993) as well as cultural subgroups within the United States (Sidanius, Pratto, & Rabinowitz, Reference Sidanius, Pratto and Rabinowitz1994). However, little research has been conducted in lower-income, high-poverty contexts, such as the Philippines, and even less focused on perceptions of institutional social dominance.

Social Identity

Social dominance has the potential to undermine pride in identity. Social identity develops through evaluation of the characteristics of salient groups; both those one belongs to and those one does not belong to. These characteristics may include prestige (hierarchical dominance), ethnicity, or competence (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Hatch and Schultz2004). In turn, there are a number of consequences of strong (or weak) social identity, including increases (or decreases) in levels of empowerment (Amiot, Terry, Wirawan, & Grice, Reference Amiot, Terry, Wirawan and Grice2010; Brown, Reference Brown2000; Sheldon & Bettencourt, Reference Sheldon and Bettencourt2002).

In the aid and development context, host nationals will often engage in social comparison in order to preserve the integrity of their group identity (Carr, Ehiobuche, Rugimbana & Munro, Reference Carr, Ehiobuche, Rugimbana and Munro1996). Where the ingroup has a collectivist culture, such as in the Philippines (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, Reference House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman and Gupta2008), these effects are likely to be stronger (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Ehiobuche, Rugimbana and Munro1996). Indeed, the present context of expatriate:local relations means ethnicity is likely to be highly salient in shaping the social identity of respondents (Toh & Denisi, Reference Toh and Denisi2007; Varma, Toh, & Budhwar, Reference Varma, Toh and Budhwar2006).

One of the results of successful ingroup identity preservation is an increase in self-esteem felt by the members of the ingroup (Abrams & Hogg, Reference Abrams and Hogg1988). Empirical evidence supports a significant correlation (r = .5; p < .001) between self-esteem and empowerment as a whole (Menon, Reference Menon2001, p. 171). Thus, if host nationals’ social identity is negatively valued, social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Hatch and Schultz2004) would predict low levels of empowerment among Filipino aid employees.

As with empowerment and social dominance, social identity theory has been developed mainly in a Western setting (Bond & Hewstone, Reference Bond and Hewstone1988). In social identity theory, the out-group must be reasonably comparable (Hogg, Terry, & White, Reference Hogg, Terry and White1995). Western expatriates may not be sufficiently similar to provoke outgroup comparison by locals (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Ehiobuche, Rugimbana and Munro1996; Coates & Carr, Reference Coates and Carr2005) in the Philippines. Additionally, any differences may be viewed as legitimate, in which case efforts to improve self-esteem (the motivation for group identity formation) may not occur (Brown, Reference Brown2000). Local employees may internalise their own identity as inferior and less deserving. This possibility (which is consistent with social dominance theory) is a provocative one.

Organisational Justice

The third contributor to employee empowerment considered in this study is organisational justice. Being treated fairly (justice) is a necessary requirement for decent work, as enshrined in United Nations Millennium Development Goal 1b (United Nations, 2010, p. 8). Ironically, as MacLachlan et al. (Reference MacLachlan, Carr and McAuliffe2010) have pointed out, this ideal is far from being realised in many aid and development organisations themselves.

Justice at work was initially focused on the effect of unfair rewards on employees (Homans, Reference Homans1961). This kind of justice (distributive) is about how just rewards are perceived to be in relation to those received by other salient groups of employees (Adams, Reference Adams and Berkowitz1965; Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1987). Perceptions of justice were also found to be greater where people had greater control over the processes that affected them at work (procedural justice; Thibaut & Walker, Reference Thibaut and Walker1978). Appropriate monitoring has been found to communicate procedural justice (Niehoff & Moorman, Reference Niehoff and Moorman1993). Criticisms of the lack of monitoring in aid work (Wenar, Reference Wenar2006) are therefore of potential concern.

In 1986, Bies and Moag suggested that interactional justice (the way that people are treated in their interactions within the organisation), was distinct from procedural or distributive justice (Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1990). This distinction is important in the present context, because the way Filipino aid workers are treated within their organisations may be the most significant aspect of justice for them, because of the importance placed on interpersonal harmony within cultures high in collectivism (Beugr, Reference Beugr2002; Crosby, Reference Crosby, Cummings and Staw1984).

When local employees experience low levels of distributive justice in their work environment (e.g., pay inequality), a wide range of outcomes, such as lowered job satisfaction, performance and organisational commitment may occur (Carr, Chipande, & MacLachlan, Reference Carr, Chipande and MacLachlan1998; Cohen-Charash & Spector, Reference Cohen-Charash and Spector2001; Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter, & Ng, Reference Colquitt2001; McAuliffe, Manafa, Maseko, Bowie & White, Reference McAuliffe, Manafa, Maseko, Bowie and White2009). These suggestions have recently been substantiated in a large (N = 1,290) study across six countries in Africa, Oceania and Asia, where host national professionals reported both disparate levels of remuneration between locals and expatriates and a sense of relative injustice and demotivation (Carr, McWha, MacLachlan, & Furnham, Reference Carr, McWha, MacLachlan and Furnham2010).

It is worth noting that the theoretical structure of justice remains contested. In a meta-analytic attempt at clarification, Cohen-Charash and Spector (Reference Cohen-Charash and Spector2001) affirmed the existence of distributive, procedural and interactional justice. However, other theorists (Colquitt et al., Reference Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter and Ng2001; Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1990) argued that interactional justice included two aspects, namely how information was communicated (informational justice) and how well people were treated by others (interpersonal justice). While a four-dimensional conceptualisation of justice has been found to fit the observed data better than the three-dimensional approach (Colquitt, Reference Colquitt2001), I note that the goodness of fit of all models tested was poor to mediocre.Footnote 1 I find Bies’ (Reference Bies, Greenberg and Colquitt2005) approach informative; he believes in the two components of interactional justice, but also states that whether it is one component or two does not matter. In this study I have used a version of Niehoff and Moorman's (1993) three-dimensional justice measure similar to that adapted by McAuliffe et al. (Reference McAuliffe, Manafa, Maseko, Bowie and White2009).

Demographic Variables

In addition to the psychological antecedents (perceived social dominance, social identity and perceptions of organisational justice) that form the focus of this study, it is also important to acknowledge that differences in numerical group size (Doms & van Avermaet, Reference Doms, van Avermaet, Moscovici and Avermaet1985; Latané, Reference Latané1981), age (Kanter, Reference Kanter1979; Spreitzer, Kizilos, & Nason, Reference Spreitzer, Kizilos and Nason1997) or gender (Hochwälder & Brucefors, Reference Hochwälder and Brucefors2005; Spreitzer et al., Reference Spreitzer, Kizilos and Nason1997; Zani & Pietrantoni, Reference Zani and Pietrantoni2001) may also influence levels of empowerment.

Focusing Questions

This exploratory study, rather than proposing hypotheses to be tested, explored first, whether the constructs outlined above would be substantiated in the Philippine context; and second, which of the antecedents made the most difference to self-reported empowerment amongst the Filipino aid employees that responded to the survey.

Method

Participants

A total of N = 98 Filipino aid sector employees responded to a survey invitation circulated via email by the administrators of several development associations and organisations in the Philippines (86 in English and 12 in Tagalog, the two official languages of the Philippines). Of the N = 82 participants who indicated their gender, 24 (29%) were male and 58 (71%) were female. The mean age was 35.5 years, ranging from 20 to 66 years old. The mean length of employment in the aid sector was 10.9 years, ranging from 4 months to 39 years. Respondents were highly qualified, with 52% holding an undergraduate degree and a further 38% holding a graduate degree of some kind. Analysis of respondent computer internet protocol address ownership and geographical location revealed a diverse pattern of respondents from around the Philippines.Footnote 2 The sample was sufficiently varied and was adequate for exploratory research, although response rate could not be calculated.

Measures

For empowerment, perceived social dominance, social identity, justice and social desirability (provided the items factor analysed into a predicted pattern) item scores were added together and divided by the number of items to obtain mean scores per item per factor (composite scores). Factor analyses are outlined in the Results section.

Empowerment

Empowerment was measured with the multidimensional measure (Items 1–12 in Appendix) developed by Spreitzer (Reference Spreitzer1995). Spreitzer (Reference Spreitzer1995) reported using confirmatory factor analysis that the overall measure taps into four underlying and interrelated constructs that together represent empowerment: meaning, competence, self-determination and impact. These constructs were both scored separately and added together to constitute empowerment, depending on the focus of analysis.

Perceived social dominance

Following Coates and Carr (Reference Coates and Carr2005), a measure of perceived social dominance (Items 49–62 in Appendix) was adapted from Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, and Malle (Reference Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth and Malle1994). In the item wording, the original phrases ‘some people’ and ‘others’ were replaced with ‘local workers’ and ‘expatriates’ in order to make the intended referent groups explicit. This local adaptation follows a recommendation from Pratto et al. (Reference Pratto, Liu, Levin, Sidanius, Shih and Bachrach2000).

Social identity

Social identity was assessed using by a 10-item measure (Items SI-33–SI-42 in Appendix) adapted from Ellemers, Kortekaas, and Ouwerkerk (Reference Ellemers, Kortekaas and Ouwerkerk1999). To maintain consistency, the same seven-item Likert scale, as in the previous questions, was used in this measure. Item wording was made more explicit in this study compared with the original measure, replacing ‘the group’ with ‘being Filipino’ or similar.

Organisational justice

Organisational justice was measured by a 20-item measure (Items 13–32 in Appendix) originally developed by Niehoff and Moorman (Reference Niehoff and Moorman1993). McAuliffe et al. (Reference McAuliffe, Manafa, Maseko, Bowie and White2009) adapted the original measure, altering the wording of all items from individual sentences to a stem and clause format, but evaluating each item on a 5-point Likert scale. The present study uses a wording identical to McAuliffe, et al. (Reference McAuliffe, Manafa, Maseko, Bowie and White2009), with a reinstatement of Niehoff and Moorman's (1993) original 7-point response scale for consistency with other measures.

Demographics

A number of single questions asked respondents to provide demographic information (see Appendix A), including age, gender, years of experience working in the aid sector, job title and highest qualification. Two questions asked respondents to estimate the local: expatriate ratio of (1) salaries and (2) numbers of employees in their organisational network.

Social desirability

A measure of social desirability bias was presented together with the social identity measure. Six items (Items SD-43– SD-48 in Appendix) taken from Fischer and Fick (Reference Fischer and Fick1993) were presented approximately alternately with those measuring social identity. Originally, the response options to these items were dichotomous (T/F). To maintain consistency with the social identity items with which these social desirability items were presented, response options ranged from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree). Responses > 4 were recoded T while responses < 4 were recoded F. Responses of exactly 4 were recoded as missing.

Procedure

All data was collected at a single point in time via a single online survey. Significant effort went into improving the quality of measure items where rewording from the original took place, in line with recommendations from Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). The survey was provided in both English and Tagalog, the most widespread indigenous language in the Philippines, after consultation with a cultural advisor and pilot testing. Following recommendations outlined by Brislin (Reference Brislin, Triandis and Berry1980) and Bontempo (Reference Bontempo1993), the survey was translated and back-translated by separate translators. Discrepancies between the original English version and the back-translated English version were resolved in consultation with a third bilingual consultant. See the Appendix for the English questionnaire. The Tagalog survey is available from the author.

Protocol for factor analyses

Exploratory principal axis factoring with direct oblimin rotation was used to assess the factor structure of the multi-item measures. A Harman test (Harman, Reference Harman1976) was used to assess whether a single second-order factor was also justified in each case. Where items cross-loaded evenly and significantly on more than one extracted factor, or did not load significantly on any factor, these were removed and the analysis was re-run without them (where items were deleted on either basis, this is noted on each relevant factor solution table below). Once a stable and clear factor solution had been obtained (factors required eigenvalues > 1), items on each factor were summed and divided by the number of items to provide a composite and comparable variable for each factor, for each measure (Spicer, Reference Spicer2005).Footnote 3 Where factor loading patterns were similar to those reported by the measures’ authors, the present study continues to use the original factor labels, in order to maintain consistency with the relevant theory. Where the factor loadings differed from those originally reported, the label used derives from the meaning of the items loading on that factor in this study.

Protocol for regression analyses

Variables were included if they correlated significantly (p < .05) with the target variable for each regression (Table 5). The univariate normality of each variable was verified by checking its histogram. Bivariate homoscedascity and linearity of each variable in relation to the target dependent variable was also verified by checking a scatter-plot. As this was exploratory research, not enough was known about the relationships being explored to predetermine the order of entry into regression analyses. Therefore, simultaneous entry of variables into regression analyses was used. Once variables were all entered into the analysis, multicollinearity was checked by ensuring that the tolerance statistic was above 0.4 (Spicer, Reference Spicer2005). Where this was problematic, the ‘offending’ variable(s) was removed and the analysis was re-run. For each regression, the histogram of standardised residuals was checked to verify multivariate normality and to identify outliers. Where outliers were identified, they were removed and the analysis re-run without them. If the consequent model fit was improved, the outliers remained excluded, otherwise they were returned to the analysis (Spicer, Reference Spicer2005). Multivariate homoscedascity and linearity were verified by checking the scatter-plot of standardised residuals vs. standardised predicted values.

Results

Assessing Construct Performance: Factor Analyses

Empowerment

The analysis resulted in four meaningful factors: meaning (α = .799); competence (α = .831); self-determination (α = .909); impact (α = .830) (Table 1). The factor correlations were moderate and all items loaded on the first unrotated factor. Two of the rotated factors show negative loadings. However, all the unrotated factor intercorrelations (Table 5) were both positive and of more modest magnitude than the rotated loadings (Table 1). This suggests the negative loadings resulted from the oblique rotation used in the factor analysis. I therefore cautiously followed Spreitzer (Reference Spreitzer1995) in constructing a composite measure from all items representing the overall construct of empowerment (mean = 6.162; S.D. = .58; α = .866), although I acknowledge such a composite is only modestly supported given these findings.

Table 1 Factor Solution for Empowerment Measure

Note. Loadings <.3 have been suppressed, in accordance with Burt and Banks’ (Reference Burt and Banks1947) formula.

KMO = .820. Bartlett's sphericity p < .000.

Direct oblimin rotation used.

Perceived social dominance

The analysis resulted in three meaningful factors,Footnote 4 which in Table 2 I have labeled ‘inequality’ (α = .881), ‘expatriate attitudes’ (α = .839), and ‘equality’ (α = .813).

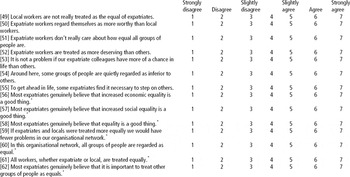

Table 2 Factor Solution for Perceived Social Dominance Measure

Note: Item ‘Most expatriates genuinely believe that it is important to treat other groups of people as equals” was removed from factor solution as it cross-loaded (> .4) on two factors. Item “It is not a problem if our expatriate colleagues have more of a chance in life than others” was removed from factor solution as it did not load significantly on any factor.

Loadings < .3 have been suppressed, in accordance with Burt and Banks’ (Reference Burt and Banks1947) formula. KMO = .782. Bartlett's sphericity p < .000.

Direct oblimin rotation used.

** Item reverse scored

Social identity

The analysis found 2 factors, which in Table 3 I have labeled ‘positive Filipino identity’ (α = .853); and self-categorisation (α = .698). It appears that two of the original factors reported by Ellemers, et al. (Reference Ellemers, Kortekaas and Ouwerkerk1999) (‘group self-esteem’ and ‘commitment to the group’) have collapsed into a single underlying ‘positive Filipino identity’ factor in this study (Table 3).

Table 3 Factor Solution for Social Identity Measure

Note. Item “I would rather belong to another ethnic group (other than Filipino)” removed from factor solution as it cross-loaded (> .4) on to more than one factor.

KMO = .877. Bartlett's sphericity p < .000

Direct oblimin rotation used.

** Item reverse scored

While this factor structure differs from that found by Ellemers, et al. (Reference Ellemers, Kortekaas and Ouwerkerk1999), the correlation between the two extracted factors (.601) affirms social identity as an overarching construct in the present context (mean = 6.08; S.D. = .971; α = .880).

Organisational justice

The three factors found (Table 4) matched those reported by both Niehoff and Moorman (Reference Niehoff and Moorman1993) and Spreitzer (Reference Spreitzer1995); interactional justice (α = .948); procedural justice (α = .951) and distributive justice (α = .810). The factor correlations in this sample are moderate, indicating neither multicollinearity nor lack of cohesion amongst the factors. As discussed in relation to the empowerment factor solution above, and for the same reasons, I interpreted the negative factor loadings for the procedural justice items as an artifact of the oblique rotation used. All items in the original measure also loaded on the first unrotated factor, indicating shared variance with an overall underlying construct of organisational justice (mean = 5.835; S.D. = .781; α = .950).

Table 4 Factor Solution for Organizational Justice Measure

Note. Item “I am satisfied with. . .my pay” was removed from factor solution as it cross-loaded (> .4) on to more than one factor.

KMO = .894. Bartlett's sphericity p < .000.

Direct oblimin rotation used.

Social desirability

KMO (.539) and Bartlett's sphericity (p < .004) test results indicated the social desirability data was marginal for factor analysis.Footnote 5 The initial communalities were low (five of the six < .160) and reliability was poor (α = .464). The responses to this measure did not match the expected pattern, for example, on one item, “I am always courteous, even to people who are disagreeable,” almost everyone strongly agreed, indicating almost universal strong social desirability bias, according to the norms of the measure (Crowne & Marlowe, Reference Crowne and Marlowe1960). I believe this reflects Filipino cultural preferences regarding maintaining social harmony (Sison, Reference Sison, Werhane and Singer1999), more than a tendency or bias to give socially desirable answers in a survey. Given these significant validity issues, this measure was not used further.

Correlation Analyses

The most striking features in Table 5 are the moderate but statistically significant correlations found between work justice as a whole, and all four facets of empowerment (competence = .325, p < .01; self-determination = .482, p < .01; meaning = .382, p < .01; impact = .477, p < .01).

Table 5 Correlation Matrix

Note. All nonsignificant coefficients were omitted. Coefficients significant at p < .01 in bold.

Headings in ALL CAPS designate composite variables.

** p < 0.01. * p < 0.05.

Numerical ratio and salary ratio had both insufficient spread and a large number of missing values. No significant correlations between level of education or gender and any of the target variables were observed. Hence these four variables were omitted from both Table 5 and further analysis.

The Predictors of Empowerment: Regression Analyses

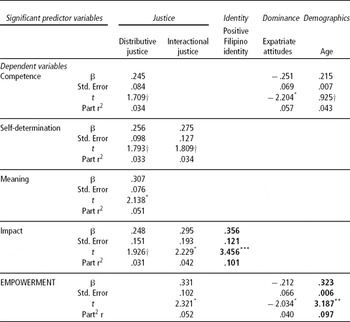

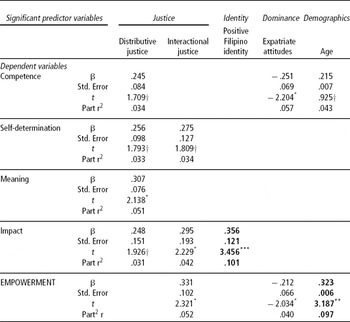

What predicts employees’ sense of competence?

Respondents’ perceptions that expatriates believed in equality in their workplace were uniquely associated with feeling more competent in their work (part r2 = .057; p < .05). Being older (part r2 = .043; p < .1) and perceiving higher levels of distributive justice (part r2 = .034; p < .1) were also uniquely related to respondents’ sense of competence. The overall model tested (F[5, 65] = 4.058; p = .003) accounted for .179 (adjusted R 2) of the total variance in competence (Table 6).

Table 6 Significant Predictors of Facets of Empowerment (Competence, Meaning, Self-determination & Impact) as well as EMPOWERMENT as a whole

Note. All nonsignificant coefficients were omitted. Coefficients significant at p < .01 in bold.

Headings in ALL CAPS designate composite variables.

***p < .001. **p < .01. *p < .05. † p < .1.

What predicts employees’ sense of self-determination?

Being treated fairly in personal interactions (interactional justice) was uniquely associated with a sense of self-determination (part r2 = .034; p < .1). Receiving just rewards (distributive justice) also contributed to this facet of empowerment (part r2 = .033; p < .1). The overall model tested (F[4, 69] = 7.062; p < .001) accounted for .249 (adjusted R 2) of the total variance in self-determination (Table 6).

What predicts employees’ sense of meaning?

Only perceptions of just reward systems (distributive justice) were uniquely associated with respondents’ sense of meaning in their work (part r2 = .051; p < .05). The overall model tested (F[8, 59] = 3.917; p = .001) accounted for .258 (adjusted R 2) of the total variance in meaning (Table 6).

What predicts employees’ sense of impact?

Having a sense of positive Filipino identity was uniquely associated with feeling that you have impact on your work (part r2 = .101; p < .001), as were perceptions of interactional justice (part r2 = .042; p < .05). The overall model tested (F[6, 63] = 9.211; p < .001) accounted for .417 (adjusted R 2) of the total variance in impact (Table 6).

What predicts empowerment as a whole?

Being older was most strongly associated with feeling more empowered (part r2 = .097; p < .01), followed by perceptions of interactional justice (part r2 = .052; p < .05) and expatriate attitudes towards equality (part r2 = .040; p < .05). The overall model tested (F[7, 59] = 6.564; p < .001) accounted for .371 (adjusted R 2) of the total variance in empowerment (Table 6).

Post Hoc Analyses

The finding that positive Filipino identity (a facet of social identity) predicted separate facets of empowerment, but not empowerment as a whole (Table 6), suggests that a moderation effect may be in play. Could positive Filipino identity moderate the relationship between interactional justice and empowerment?

Protocol for moderation exploration

Suitability for moderation analysis was verified by checking the univariate normality, bivariate homoscedascity and bivariate linearity of each variable. Univariate correlations between the parent variables (interactional justice, distributive justice and positive Filipino identity) were also examined. Multicollinearity and multivariate normality, homoscedascity and linearity were assessed to be satisfactory. Both the parent variable and the moderator variable were centered before entry to the analysis. The parent variable and the potential moderator were entered together into the first step of the analysis. The product of the centered parent and moderator variables was entered in to the second step of the analysis (Jose, Reference Jose2008).

Does positive Filipino identity moderate the relationship between interactional justice and empowerment?

As Filipino identity becomes more positive, the relationship between interactional justice and empowerment becomes weaker, reflected in the relatively shallower slope of the line in where positive Filipino identity is high (Jose, Reference Jose2008). The model including the product of positive Filipino identity and interactional justice (F change [1, 74] = 4.332; p = .041) explained significantly more variance (adjusted R 2 = .294) in impact than the simple combination of positive Filipino identity and interactional justice (F change [2, 75] = 14.741; p < .001; adjusted R 2 = .263).

Overall pattern of observed relationships

Figure 2 graphically shows the observed significant relationships from Table 6 between the predictor variables and (a) the components of empowerment (dotted lines), and (b) empowerment as a whole (solid lines). Standardised beta weights are indicated on the relevant line in the model. Additionally, the moderating influence of positive Filipino identity on the relationship between interactional justice and empowerment is shown with the irregularly dashed line.

Discussion

Key findings

The pervasive impact of justice on empowerment

Perceptions of justice had by far the most numerous effects on empowerment. The priority of interactional justice over other forms of justice in predicting empowerment is striking (Figure 2), supporting prior observations that interpersonal harmony may be more important than distributive justice in collectivistic societies (Beugr, Reference Beugr2002; Crosby, Reference Crosby, Cummings and Staw1984) such as the Philippines.Footnote 6

Consistent with other research (Carr, et al., Reference Carr, Chipande and MacLachlan1998; MacLachlan, et al., Reference MacLachlan, Carr and McAuliffe2010; McAuliffe, et al., Reference McAuliffe, Manafa, Maseko, Bowie and White2009), higher levels of distributive justice were related positively to all aspects of empowerment amongst Filipino aid employees (Table 6; Figure 2). This adds to the evidence linking justice with satisfaction, effectiveness and productivity (McAuliffe, et al., Reference McAuliffe, Manafa, Maseko, Bowie and White2009; McWha, Reference McWha2010). However, distributive justice did not predict empowerment as a whole (Table 6). This is somewhat perplexing, and is perhaps a methodological artifact, given the modest strength of the results in terms of effect sizes and statistical significance. Research with larger samples could help to clarify this finding.

The absence of any significant unique relationships between procedural justice and empowerment is intriguing and suggests further research would be useful. Perhaps transparent process is less salient in the Filipino context, or is less important than being treated fairly in personal interactions.

The significance of age and experience

Age closely followed interactional justice as a significant predictor of empowerment (see Figure 2). As expected (Kanter, Reference Kanter1979; Spreitzer, et al., Reference Spreitzer, Kizilos and Nason1997), older employees with longer tenure felt more empowered. Given the high correlation between age and years experience in the aid and development sector (.801), this seems likely to reflect mainly the greater competence that experience brings.

How social identity contributes to empowerment in the workplace

The general prediction arising from social identity theory is that positive social identity should give rise to higher levels of empowerment (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Hatch and Schultz2004). This is broadly supported by the positive relationships observed between these constructs in the present study (Table 5). More specifically, a significant link between positive Filipino identity and a sense of having an impact in their workplace (Figure 2) was observed. Positive Filipino identity was also found to moderate the influence of interactional justice on empowerment (Figure 1; Figure 2); those with a stronger Filipino identity were less negatively affected by injustice in personal interactions. Given this moderation effect was observed in a sample who reported generally strong Filipino identity (mean = 6.288; S.D. = 1.019), the converse implication may be more disturbing: Employees with a weaker sense of Filipino identity may be particularly vulnerable to disempowerment as a result of unfair interpersonal interactions.

Figure 1 Moderation of the relationship between interactional justice and empowerment by positive filipino identity.

Figure 2 Observed predictors of empowerment and its components

Note. Solid lines = main effects; Dashed lines = component effects; Irregularly dashed line = moderation effect

Although positive Filipino identity, a component of social identity, was the strongest predictor of employee's sense of impact (β = .356; p < .001) it failed to emerge as a significant direct predictor of empowerment more generally (Table 6). This may be because its influence is mostly indirect, moderating the way other antecedents (for example interactional justice) affect empowerment. Alternatively this may reflect weakness in the composite empowerment variable in this study.

How social dominance contributes to empowerment in the workplace

Social dominance theory predicts that employees who perceive their organisational network to be hierarchy-enhancing will experience less empowerment than those in hierarchy-attenuating contexts (Sidanius, et al., Reference Sidanius, Pratto, van Laar and Levin2004). There is some support for this in the negative correlations between the various aspects of perceived social dominance and aspects of empowerment (Table 5). However, social dominance as a coherent construct is not well supported in the present study. This was somewhat surprising given the comprehensive effects of social hierarchies documented elsewhere (Goodwin & Operario, Reference Goodwin and Operario1998; Pratto, et al., Reference Pratto, Liu, Levin, Sidanius, Shih and Bachrach2000), including in the aid and development context (MacLachlan, et al., Reference MacLachlan, Carr and McAuliffe2010). Perhaps the items measuring perceptions of (in)equality were more difficult to estimate accurately compared with those items referencing expatriates’ attitudes.

What was clear was that where local employees perceived expatriate attitudes towards equality to be less negative, they felt more empowered (Figure 2). More specifically, perceptions of expatriate beliefs about equality have the potential to impact local employees’ sense of competence at work.

How the Philippine context affected the constructs measured in this study

Empowerment and its four components (competence, self-determination, meaning and impact) were supported strongly by the obtained factor solution. It may therefore be meaningful to discuss empowerment in the Philippines in the terms outlined by Spreitzer (Reference Spreitzer1995; Reference Spreitzer, Cooper and Barling2008). Likewise, the structure of justice as distributive, procedural and interactional justice (Cohen-Charash & Spector, Reference Cohen-Charash and Spector2001; Niehoff & Moorman, Reference Niehoff and Moorman1993) was supported in this Philippine context. Social identity also appears to be validated in the present context, although the distinction between self-esteem and group commitment (Ellemers, et al., Reference Ellemers, Kortekaas and Ouwerkerk1999) was not supported.

However, contrary to expectations about the stability of social dominance across cultures (Pratto, et al., Reference Pratto, Liu, Levin, Sidanius, Shih and Bachrach2000), the structure of perceived social dominance as a coherent unidimensional construct was not supported. Instead, three clear factors (inequality, expatriate attitudes and equality) were observed in the present study. It may be that the rewording of items in this measure which took place in order to focus respondents on expatriate-local dynamics in their organisational network caused this change in the observed factor structure of perceived social dominance.

Policy Implications

A number of tentative implications for development practice can be identified. The significant role of justice perceptions supports calls for attention to pay equity and wider issues of justice made previously by a number of researchers (Carr, et al., Reference Carr, Chipande and MacLachlan1998; MacLachlan, et al., Reference MacLachlan, Carr and McAuliffe2010; McAuliffe, et al., Reference McAuliffe, Manafa, Maseko, Bowie and White2009; McWha, Reference McWha2010). Training for both expatriates and locals regarding the importance of justice in interpersonal interactions could be helpful. Further, expatriate attitudes towards equality clearly matter. Thus raising awareness of this during expatriate preparation for overseas assignments could benefit local employees. Lastly, the potential buffer effect of strong Filipino identity against injustice provides a rationale for efforts that aim to strengthen positive identity amongst local employees in aid organisations in the Philippines.

Limitations and Improvements

Little is known about the representativeness or response rate of the sample. A degree of self-selection is likely to have occurred. The small sample size means both the factor and regression analyses should be treated cautiously as exploratory findings. Researchers based in the Philippines may have been able to take advantage of more robust sampling techniques including distributing fixed numbers of surveys to potential respondents at their physical workplace. As with all self-report-based studies, there is likely to be a difference between how respondents actually feel and how they report their feelings. Common method variance may have been partly responsible for the relationships observed between the variables,Footnote 7 although the generally very high levels of reliability observed on all measures may mitigate against this possibility (Laschinger, Finegan, Shamian, & Wilk, Reference Laschinger, Finegan, Shamian and Wilk2004).

Differences between English and Tagalog survey respondents were observed on 8 of the 64 items. Given both the large number of potential items, and the small number of respondents who responded in Tagalog (N = 12), the observed differences seem relatively unconcerning. The rigorous process of translation, back translation and consultation regarding the two language versions of the questionnaire (Brislin, Reference Brislin, Triandis and Berry1980) minimised the possibility of serious confounding as a result of language difference.

Suggestions for Further Research

First, the importance of interactional justice in comparison with distributive justice in the Philippines and other more collective-oriented societies seems critical. While pay equity is clearly an important issue, the role of justice in interpersonal interactions may be more important than previously thought, and there is little research on the subject within the context of aid work.

Second, the lack of coherence of social dominance in the present study was surprising. In direct contrast to the assertions of Pratto, et al. (Reference Pratto, Liu, Levin, Sidanius, Shih and Bachrach2000), social dominance as a theoretical construct fared the least well of all the measures used in the present study. Perhaps hierarchy and patterns of dominance are taken for granted in the Philippines (de Guzman, Reference de Guzman2011), or perhaps the construct was poorly operationalised in the present study. In any case, more research is needed to explore whether social dominance theory as constituted elsewhere (Sidanius, et al., Reference Sidanius, Pratto, van Laar and Levin2004) is relevant to aid work in the Philippines.

Third, the potential for aspects of social identity, in particular positive ethnic identity, to buffer the effects of (in)justice is potentially of great interest not only in the Philippines, but in many postcolonial settings. A related issue regarding social identity that the present study did not address revolves around the comparative importance of ethnic versus organisational identity. What happens if local employees feel more attachment to (for example) being Filipino than to being employees of a particular organisation? Further research into the contrasting (or complementary) effects of identification with both local employees’ ethnic group and the employing aid organisation would help to shed light on this issue.

Conclusion

The focus on the provision of decent work for all is enshrined in Millennium Goal 1b (United Nations, 2000). Human dynamics such as dominance, identity and justice influence the achievement of this worthy goal. This study contributes significant new clarity to the ways in which these factors influence workplace empowerment, which is central to the very notion of decent work. Amongst aid sector employees in the Philippines, interactional justice is the single largest contributor to perceptions of empowerment, followed by age and expatriate attitudes towards equality. A strong Filipino identity played the largest role amongst the variables in this study in determining the sense of impact local employees feel they can have in their workplace. Further, when the sense of Filipino identity is positive, interactional justice matters less.

If we are to achieve the maximum progress possible towards the Millennium goals, organisations involved in aid work need to be cognisant of the human dynamics of the workplace. Local employees will increasingly form the bulk of the aid sector workforce and thus their empowerment is critical to maintaining a productive and effective workforce. Treating them fairly and fostering conditions which support a strong sense of social identity are key to achieving the goals of individuals and organisations alike within the broad sweep of efforts to reduce poverty on this planet.

Appendix

Questionnaire

NOTE: This questionnaire is available in Tagalog from the author

The questions below focus on your attitudes and beliefs as an employee in aid/development work in the Philippines. As you answer the questions, think about the relationships, patterns and culture within your organisational network. This is the group of people, both international and local, that you would normally expect to work with in your organisation, partnership or project.

The first set of questions is about how empowered you feel in your organisational network.

Choose the response that best reflects how much you agree with these statements.

The next set of questions is about fairness between Filipinos and expatriates in your organisational network. This includes the people you would normally be expected to work with, both local and international, in your organisation, partnership or project.

Choose the response that best reflects how much you agree with these statements.

My manager/supervisor. . .

I am satisfied with. . .

The next set of questions is about your feelings and attitudes in the context of your organisational network.

Choose the response that best reflects how much you agree with these statements.

[*reverse coded]

Please think again about local and international colleagues and the relationships you have within your organisational network. This includes the people you would normally be expected to work with, both international and local, in your organisation, partnership or project.

Beside each statement, select a number from ‘1’ to ‘7’ which represents how strongly people in your organisational network would agree or disagree with the statement.

In this network:

[*reverse coded]

The next two questions ask you to make estimations about your organisational network. This includes the people you would normally be expected to work with, both local and international, in your organisation, partnership or project.

[63] What is the approximate ratio between the numbers of international and local employees in your organisational network? (for example “50% Filipino:50% International”, or “80% Filipino: 20% International”) _______________

[64] What is the approximate ratio between Filipino and international salaries in your organisational network? (for example “Filipino 1:1 International” would mean that Filipino and international salaries are about the same, or “Filipino 1:10 International” would mean that Filipino salaries are about 1/10th or 10% of international salaries) ________________

The final set of questions asks about some information about you.

[65] What is your age in years? ________________

[66] What is your gender?MaleFemale

[67] What is your ethnicity?FilipinoOther

[68] What is your job title? ___________________

[69] What is your highest qualification? ___________________

[70] How many year's experience in the development sector do you have? ______

Thank you for taking part in this survey.

Acknowledgments

This paper presents the main findings of a masteral thesis. The author is grateful to Professor Stuart Carr for his guidance and generous supervision throughout the project. The author is also appreciative of the insightful cultural advice provided by Judith Marasigan de Guzman and the assistance she and her associates in Manila, Philippines provided to the author in contacting suitable survey respondents. The peer reviewers' comments on earlier versions of this paper were also very helpful and much appreciated.