One great advantage indeed of the Embassy is the opportunity it afforded of showing the Chinese to what a high degree of perfection the English nation had carried all the arts and accomplishments of civilized life.

Lord George Macartney, 1793–4On 22 January 1806 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, the London audience could ‘listen’ to the soundscape of China, and could experience vicariously what Lord George Macartney and his entourage would have witnessed during the first British embassy to China in 1793. Elements of Chinese music and ceremony were featured in the five-act opera The Travellers, or Music's Fascination (1806) by the London-based Italian composer Domenico Corri (1746–1825). The opera's main traveller, a Chinese prince named Zaphimiri, is sent abroad by his father, the emperor, who recommends to his son to learn from other countries in order to improve the state of his own country. Leaving China, Zaphimiri's journey takes him to Constantinople, Naples and then Portsmouth, England, the place to which Macartney returned after his embassy's unsuccessful mission in China twelve years prior to the opera's premiere.

The Travellers garnered a notable success at the box office, running for at least twenty-three nights, which means that about 45,000 people saw the opera at Drury Lane.Footnote 1 The popularity of Corri's opera resonates with the attention Macartney's embassy received in the public discourse, with travel accounts, private letters, diaries and numerous satires on the topic. As literary scholar Laurence Williams has shown, the satirical accounts about the embassy in the form of songs, cartoons, poems and epistles served ‘a crucial role in shaping contemporary public reactions to the embassy in the decade following its return’.Footnote 2 This is because an accurate account of the Macartney embassy and its failure was not widely available; the satires filled in the gap, Williams wrote, by ‘weav[ing] together rumours from Canton and information about China from other sources to create speculative fantasies about what had happened in “Pekin”’.Footnote 3

Similar to the satirical works that inspired ‘speculative fantasies’ about the embassy, Corri's The Travellers offers an imaginative operatic response, which balances a kind of ‘fantasy’ with first-hand experience of the embassy, specifically regarding music. Although the embassy returned to England without establishing diplomatic and trade relations, the unsuccessful mission was nonetheless significant in transferring knowledge about China through first-hand experiences. From numerous writings of the embassy's members, including Macartney's own, to the detailed sketches by the official draughtsman William Alexander, the embassy brought empirical knowledge about Chinese customs, manners and culture back to Europe.Footnote 4 Music was one of the main items of exchange, carefully prepared by the embassy, performed and heard throughout their journey in China.Footnote 5 As Thomas Irvine examines in his book Listening to China: Sound and the Sino-Western Encounter, 1770–1839, the members of the embassy's musical experience – or their listening ‘Grand Tour’ – marked a shift in the cultural encounters of the late eighteenth century, in which European observation of other cultures went from ‘a more impressionistic method to the kind of empirical observation we might today call “social science”’.Footnote 6 Such ‘empirical observation’ of the Chinese soundscape found its way directly into contemporary scholarly writings on Chinese music, in particular the work of the British music scholar Charles Burney (1726–1814), who played a key role in preparing the musical exchange of the embassy and disseminating information about Chinese music. Burney's long-standing interest in Chinese music culminated in an entry on ‘Chinese Music’ in Abraham Rees's Cyclopædia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature.Footnote 7

In this article, I show how Burney's engagement with Chinese music connects to the overall dramatic plan and specific musical materials in Corri's The Travellers. The itinerary of the opera's protagonist, Zaphimiri, leaving China and arriving in England is framed similarly to Burney's broader historical project of tracing the development of musical progress, beginning with monody and gradually gaining complexity through harmony and counterpoint, eventually arriving at ‘sophisticated’ and ‘modern’ European compositions. After examining the centrality of music in Macartney's embassy and Burney's involvement, I will show how the soundscape heard by the members of the embassy found its way into Corri's opera via Burney. Thus The Travellers, or Music's Fascination presents a groundbreaking approach to incorporating ‘authentic’ musical material; at the same time, however, the opera's ending celebrates and affirms British culture, suggesting a shift in the British perception of China in response to the failed embassy.Footnote 8 Despite its atypical operatic subject and obscurity on today's operatic stage and in scholarship, The Travellers proves to be a significant work in the nineteenth-century historiography of the Sino-British encounter.

Burney, Chinese soundscape and the Macartney embassy

In December 1793, Lord George Macartney and his embassy left Canton (now Guangzhou) and sailed back to Portsmouth after a disappointing rejection from the Qianlong emperor (1711–99) and his court.Footnote 9 The embassy had been tasked with diplomatic and commercial objectives: Macartney was to deliver King George III's congratulatory message to the emperor for his 83rd birthday, and the funder of the embassy, the East India Company, aimed to enhance trade conditions between China and Britain. As historian Maxine Berg explains, the embassy was carefully prepared with gifts and personnel, intended to demonstrate British technological and scientific advancement, as evident in the quotation from Macartney in the epigraph.Footnote 10 Furthermore, as the letter of George III to the emperor stated, Britain and China were considered equals with ‘the responsibility of overseeing the “peace and security of human kind”’.Footnote 11 The letter expressed an interest in the ‘arts and manners … where civilization has been perfected by the wise ordinances and virtuous examples of their Sovereign’.Footnote 12 Despite the careful planning, the embassy was unsuccessful. Berg argues that the goods and people taken on the embassy did not distinctly demonstrate British progress, and they failed to convey clearly the King's prospect for this mission.Footnote 13 Another explanation for the failure of the embassy, prevalent in nineteenth-century historiography, is Macartney's refusal to perform the traditional ritual of the ‘kowtow’ upon meeting the emperor, involving ‘three full kneelings accompanied by three knockings of the head on the floor (nine times in all)’; instead he bowed on one knee, a miscue that became symbolic of the difference in worldviews.Footnote 14

Regardless of the divergent interpretations of the embassy's outcome, what remains clear is that music was considered to be one of the key items of exchange, even prior to the start of the embassy.Footnote 15 The crucial figure in this preparation was Charles Burney, who played a central role in the selection of musicians to be included in the embassy. In an autograph manuscript, dating to 1792, written ‘for Lord Macartney drawn up when preparing for him a band to attend his Lordp [sic] in his Chinese Embassy’, Burney made the following suggestions:

A band of instrumental musicians, consisting of six performers, would be able to execute the greatest variety of good compositions, and in Europe, give the greatest satisfaction to real judges of the art, if they consisted of two violins, a tenor and violoncello (for quartets) with an oboe and bassoon (for symphonies).Footnote 16

Joyce Lindorff shows how Burney's plans were closely executed, in terms of the number of musicians and instruments that were brought on the embassy.Footnote 17 Not only did Burney supply the embassy with his musical recommendations, but he also sent queries regarding Chinese music.Footnote 18 The embassy returned with some Chinese instruments and information that indeed satisfied Burney's research quest. The information was supplied by the German émigré John (Johann) Christian Hüttner, a member of the embassy, who served as a tutor to the son of Macartney's deputy Sir George Staunton. Acknowledged by Burney as ‘a well-informed musician’, Hüttner played a key role in providing the information that formed the basis of Burney's article on ‘Chinese Music’ in Rees's Cyclopædia; or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature.Footnote 19

In this article, Burney explains China to be ‘the most ancient, extensive, and polished, empire that exists’ and notes that

The Chinese, the most grave, formal, and frigid people on the globe, boasts the [sic] having framed the proportions of musical tones into a regular system 4000 years ago, not only long before the time of Pythagoras, but that of the Egyptian ‘Hermes Trifmegitus megistus’, or the establishment of their mystagogues or priests.Footnote 20

Burney then quotes the work of the French Jesuit missionary Joseph-Marie Amiot (1718–93), who had asserted that ‘the music of China [has] less enchantment than in our own’. Amiot recounted that even those ‘well educated and qualified to compare and judge’ could not appreciate the music he played for them: ‘Les Sauvages, and Les Cyclopes, the most admired harpsichord lessons of the celebrated Rameau, the most beautiful and brilliant solos of Blavet for the German flute, made no impression on the Chinese.’Footnote 21 Amiot suggested that Chinese music is less captivating than European music and this might have been the reasons for the Chinese listeners’ dislike of European music. Similarly, other listeners in China, such as John Barrow, the comptroller of the embassy, heard simplicity in the texture of Chinese music. Barrow observed:

A Chinese band generally plays, or endeavours to play, in unison; and sometimes an instrument takes the octave; but they never attempt to play in separate parts, confining their art to the melody only, if I may venture to apply a name of so much sweetness to an aggregation of harsh sounds. They have not the least notion of counter-point or playing in parts; an invention, indeed to which the elegant Greeks had not arrived, and which was unknown in Europe, as well as Asia, until the monkish ages.Footnote 22

Burney also echoes Barrow's report regarding the lack of Chinese appreciation for European music encountered during the embassy:

His lordship took with him a complete military band of wind-instruments, several of whom were able occasionally, to perform well on the violin and violoncello. But the Chinese seemed wholly unmoved by the perfect execution of the best pieces, of the best composers, in Europe.Footnote 23

The reason for this lack of appreciation, for Burney, stemmed from the deficiency of harmony in Chinese music. As Irvine recounts, Burney then describes the experiment he had instigated with a barrel organ to be taken on the embassy in order to assess the Chinese listeners’ response to European music: ‘As it was well known that … the Chinese had not arrived at counterpoint, or music in parts, the author of this article tried to betray them into a love of harmony, and “the concord of sweet sounds”.’Footnote 24 Made by John Gray in London, the barrel organ was to play a harmonised version of a Chinese tune, ‘Son of Heaven’, a hymn from Amiot's Mémoire sur la musique des Chinois (1779).Footnote 25 Burney then reflects on the outcome of this harmonisation exercise, which, despite a methodical plan, failed to engender any emotional response from the Chinese listeners:

the melody to this hymn being, like our psalmody, entirely composed of flow notes of equal length, it was thought a good foundation on which to build harmony in plain counterpoint and as there are many stanzas to this hymn, a fundamental base only was added to the melody at first; then a second treble; and, afterwards, a tenor; after which a little motion was given to the base, followed by other additional notes to the tenor and base, but always taking care to enforce the principal melody by one of the other parts, either in unison or in the octave. But this had no other effect than try the patience and politeness of the Chinese, who heard it without emotion of any kind.Footnote 26

Realising that harmony and counterpoint had a negative impact on Chinese listeners, who were ‘confused and bewildered’ by it, Burney is compelled to reassess his model of musical progress:

Such are the effects which our harmony has on the ears of the most enlightened Chinese, and indeed on those of all the nations out of Europe, so that the opinion of Rousseau, that ‘our harmony is only a Gothic and barbarous invention, which we should never have thought of, if we had been more sensible to the true beauties of art, and music truly natural’ almost ceases to be a paradox.Footnote 27

This moment in Burney's writing, according to Irvine, is noteworthy for validating Jean-Jacques Rousseau's idea that the progress of music from a simple air to an harmonically rich ‘modern’ music is ‘a story of decline into decadence’.Footnote 28 ‘Burney's moment of hesitation’, explains Irvine, ‘reveals traces in his thought of a discourse opposed to the rise of counterpoint and harmony as indexes of westernized modernity and progress and to the fall of China from exemplar to object of pity’.Footnote 29 As Irvine also notes, this position is also reflected in the writings of Johann Nikolaus Forkel, who recognised the absence of counterpoint in Chinese music, although its culture has remained civilised and cultivated.Footnote 30

The ‘simplicity’ of Chinese music, as observed by European scholars, was not wholeheartedly undervalued by the listeners on the embassy. For example, Hüttner was a keen observer and an open-minded listener to Chinese music and soundscape.Footnote 31 Some of the most revealing descriptions of the embassy's musical encounter come from the early morning ceremony on 14 September 1793 as Macartney and his men were preparing to be presented to the emperor in his summer palace in Jehol (now Chengde). When the Qianlong emperor took the throne, Hüttner reported hearing ‘the most beautiful music’, and Macartney responded to the grandeur of the ceremony: ‘The commanding feature of the ceremony was that calm dignity that sober pomp of Asiatic greatness, which European refinements have not yet attained.’Footnote 32

Macartney and his entourage continued to experience the imperial rituals of Qianlong's court, and after several days, on 18 September, they were invited to one of the main celebratory events – performances of tributary dramas – with the emperor in attendance.Footnote 33 Macartney described the drama to include a combination of recitative and singing, without any instrumental accompaniment. The performance of these dramas was not favourably received by the embassy. However, one of the dramas, Si hai sheng ping (Ascendant Peace in the Four Seas), was newly commissioned by the emperor for the occasion and featured the hero Wenchang, who announces the arrival of envoys from the ‘country of Ying-li-ji [England], gazing in admiration at your imperial majesty’ and ‘sincerely [presenting] its tribute to the court’. Eventually, a storm necessitates that the British envoy return home. As Irvine explains, Macartney did not understand the drama's specific content, merely describing it as ‘a great variety, both tragical and comical … [scenes] acted in succession, though without any apparent connection to one another’.Footnote 34 Although the content was lost on the members of the embassy, it is noteworthy that the commissioned drama made an actual reference to the British guests, and even foreshadowed the unsuccessful outcome of the embassy. Merely three months after witnessing this performance, the embassy headed back to Portsmouth.

Back in England, the embassy had inspired satirical works even before its departure, and according to Williams, they ridiculed the embassy ‘as a costly folly, as an attempt to distract public attention from the struggles for liberty at home, or even as an imperialist plot to invade China’.Footnote 35 When the news of the embassy's unsuccessful outcome reached home in the summer of 1794, satires offered a more critical view of the British that (in Williams's words) ‘the true causes of the embassy's failure might lie in the assumptions, conduct, and national character of British elites’.Footnote 36

Corri's The Travellers, or Music's Fascination can be added to the list of odes, epistles and cartoons presenting diverse perspectives of the embassy. Yet it stands out as a unique work among them.Footnote 37 Although there is no direct reference to the embassy, the opera's presentation of Chinese characters, music and ceremony – especially via Burney – makes the connection to the embassy concrete. By incorporating a Chinese melody and realistic visual representation, the opera reconstructs certain rituals and ceremonies witnessed by the members of the embassy. As such, the opera presents ‘authentic’ Chinese music and ceremony while, at the same time, the opera's overall dramatic plan imparts an emerging imperialist view of the British, as the culturally and musically sophisticates from whom the Chinese are going to learn.Footnote 38 As noted earlier, the main character Zaphimiri, the Chinese prince, is sent on a grand tour-like experience, leaving China, travelling westward to England. Underlining the itinerary and the prince's experience is the opera's main theme – similar to Burney's music history project – to trace the ‘progress of music’.Footnote 39 Thus the final destination of The Travellers can be read as restating one of the embassy's agendas to show British ‘progress’ in the arts and sciences, and rebuking China's harsh dismissal of the embassy a decade earlier in an artistic form with drama and music, similar to the tributary drama witnessed by the members of the embassy.Footnote 40

A Chinese prince on a grand tour from his homeland to Britain

Domenico Corri, like Burney, never travelled to China, but he came to Edinburgh on Burney's invitation in 1771. Born in Rome and trained by Nicola Porpora in Naples, Corri was a composer, conductor, voice teacher and manager of cultural institutions, such as the Theatre Royal in Edinburgh and Vauxhall pleasure gardens (an imitation of the one in London); and he eventually found himself in music publishing. His musical output is modest: six stage works, a handful of vocal works, keyboard sonatas, and, best known, his treatise on singing, The Singer's Preceptor (1810).

His fourth opera The Travellers, with a libretto by Limerick-born Andrew Cherry (1762–1812), received a successful premiere on 22 January 1806 at Drury Lane. Zaphimiri is sent abroad by his father, the emperor, for an educational tour:

My son, your prince, with your concurrence, I design for travel; – to enlarge his mind, and glean from other states, such knowledge of their laws and customs, as might give strength and vigour to our constitution, add decision to our acts, and prune the excrescent branches of our legislature; – convinced that he is still the wisest prince who makes his people happiest.Footnote 41

The emperor's advice for the prince echoes closely the letter of George III Macartney delivered to Qianlong, in which he expressed his eagerness to become ‘acquainted with those celebrated institutions’ of China, ‘which have carried its prosperity to such a height as to be the admiration of all surrounding nations’.Footnote 42

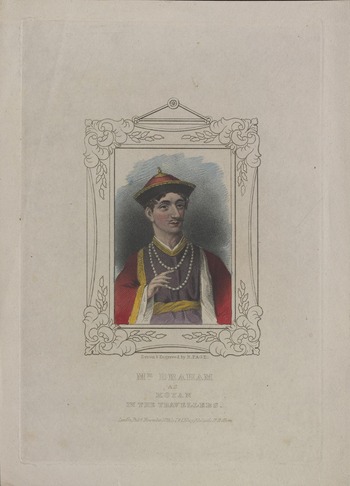

Zaphimiri's journey and experiences mirror those of a typical eighteenth-century European aristocratic male traveller on the Grand Tour, except for the itinerary from East to West.Footnote 43 Unusual for operas of the time, the main character is Chinese and was dressed in a long ornate robe with pointed slippers and a decorative hat, resembling figures depicted in Alexander's sketches produced during his time in China (see Figure 1).Footnote 44 The prince and his entourage leave China (Act I), go to Turkey (Act II), then to Italy (Naples in Act III and Caserta in Act IV), and finally end up in England in Act V. Along the way Zaphimiri gains a wealth of experiences but also gets in trouble – he is imprisoned for entering a harem in Turkey, then flees the country. The prince, as was common on the grand tour, has a tutor and others who accompany him. In fact, the voyage actually gains more significance for the prince's entourage – his tutor Koyan, played in the original production by the great English tenor John Braham, is accompanied by a mother and a sister (Figure 2).Footnote 45 The subplot is as follows: upon arriving at their final destination in Portsmouth, the tutor, his mother and sister are reunited with their English husband/father, from whom they have been separated because he had returned to England even before the birth of the children. At the end of the opera, everyone stays in England – including the Chinese prince. In the final words of the prince, as he explains the reasons for his stay, we can glean a firm acknowledgement of the superior position of Britain:

Thy lover—husband—and thy friend. Let those of my train depart, and bear the tidings to my royal father—here will I stay until his fixed command withdraw me hence. The study of your laws, your policy in peace, wisdom in war—your skill in arts and arms shall be the subjects of my strong enquiry; and, if my native land hereafter should attain pre-eminence amongst the nations of the east, let it be recorded in its future annals—she owes her boasted glory to a firm endeavor to emulate that envied code of golden ethics, which form the basis of a British Constitution.Footnote 46

Figure 1. Sketch of Robert William Elliston (1774–1831) as Zaphimiri (c.1803–6, artist unknown). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Figure 2. John Braham (1774–1856) as Koyan in The Travellers (published in 1823, artist R. Page). © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. (colour online)

The Travellers was well received in London and ‘broke box office records at the time’, Kitson has shown.Footnote 47 One reviewer confirms the opera's success:

Since the Travellers, Drury-lane has exhibited no novelty worthy of notice … . The Travellers, produced in the latter end of January, continues to draw the most crowded houses, and is every night received with applause no less abundant than just. The music of Corri has justly exalted his reputation to that of one of the first composers of the day; he has displayed an originality and force of genius, which many are disposed to envy, and few can excel.—We repeat that Corri's name will, in future, rank high in public opinion.Footnote 48

This prediction, of course, has proven untrue. Today Corri is barely known as a composer. While Corri's music was highly praised in the preceding review, the librettist Cherry received harsher criticism:

This opera of five acts, stands amongst dramas precisely in the predicament of a hog with six legs, amidst the swinish multitude, and John Bull has consequently approached and stared at it with all that fond delight, uncorrupted by judgment, in which he so frequently indulges … . Mr. Corri, the composer, may be considered as the legitimate father of this illegitimate opera. He had imaged the travels, and prepared the music for the different countries, but was at a loss for a poet. He sent into the highways without success—he went to sleep, and dreamed of Mr. Cherry. By him the outline was filled up, to this ready-made music syllables were counted out, and thus this jumble produced. Such are the flights of the genius of modern dramatists and composers!Footnote 49

In fact, Cherry was very much aware of this ‘jumble’ opera and, as mentioned in his apologetic preface, claimed that the somewhat convoluted plot was to fulfil Corri's vision of the opera as featuring the ‘progress of music’:

When Mr. Corri suggested to me his wish to have an opera written wherein the national melody of various kingdoms might effectually be introduced, and the progress of music traced, commencing in China and terminating in England, I considered the undertaking hazardous, and dreaded the innovation upon legitimate drama that must arise from the execution of such a plan; but on reflecting that good music has often had the power to soften even the heart of criticism, and by the exertion of its magic influence frequently obtained fo[r]giveness for incongruities and absurdities of a similar nature, I have ventured to throw myself on the mercy of the public.Footnote 50

Cherry relinquishes his responsibility for this peculiar, unoperatic subject and pleads to the public for music to ‘soften’ any criticism directed at the quality of the drama. We might well agree with Cherry that Corri's request to present the progress of music (from China to England) is not the most dramatically captivating subject. From the little we know about Cherry, he was better known for his acting at the Theatre Royal in Dublin and a 1802 debut at Drury Lane than for his playwriting.Footnote 51 He was not a prolific playwright, though The Travellers was one of two works for the Drury Lane that was published.

In the prologue to the opera, Cherry outlines the destination of the prince, going westward, from China to Turkey to England. In fact, the journey is described as music's progress, with the origin of music being a lyre first sounded in China:

The progress is clearly described as music gaining complexity through harmony. China is described as the ‘origin of sound’, ‘artless’ and natural. This ‘infant’ sound is produced by the lyre and from ‘feather'd songsters’ sweetly-warbling throats’.Footnote 53 The next step on the journey is Turkey, where ‘harmonic art’ is heard, and this is an improved state of music. Though imperfect, the addition of harmony is described as ‘affecting the heart’. A further progress in harmony is emphasised with Italy. Then finally, in England, ‘Art and Science meet’, and they ‘harmonious sweetly float along’ with freedom in that land.

The opera's project of tracing music's progress, with China as the origin point of music, can be clearly linked to Burney's ideas about Chinese music. Burney explains that the Chinese pioneered the musical system long before Pythagoras; however, Chinese music has remained simple, and does not consist of sophistication and ‘musical omnipotence’. The lack of musical complexity signifies the lack of cultural and scientific progress of the ‘ancient’ and ‘polished’ China. Musical decline, or status, equals a nation's decline. Burney writes:

But music, like other ancient arts, has so much depended on the tranquil and prosperous state of the nations by which it has been patronized, that, after being invented, cultivated, and brought to a certain degree of perfection, it has partaken of all the vicissitudes and calamities of states, and has been so totally lost during the horrors of invasion, revolution, and ruin, that if, in a long series of years, prosperity should return, neither its music nor its system is to be found.Footnote 54

Here Burney goes beyond the discussion of music's progress and puts the importance of music in a broader perspective, as a gauge for understanding the history of a nation.Footnote 55 It is no wonder, then, that music's central place in the Macartney embassy subsequently permeated the British public's reception of this significant exchange.

An opera about the ‘Progress of Music’

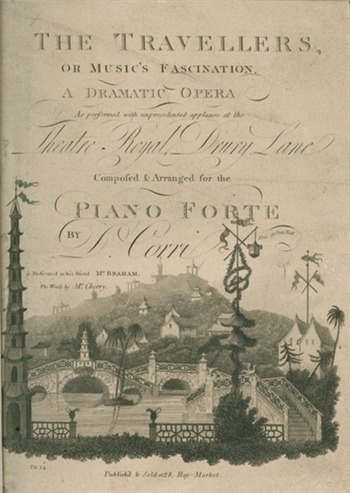

The frontispiece to the vocal score of The Travellers presents a panoramic view, consisting of a hodgepodge of exotic features (Figure 3).Footnote 56 On the distant hill, we see several Chinese pavilions with decorated pinnacles, next to which are quasi-Turkish mosques as well as Italianate villas with gabled roofs, surrounded by both pine trees and more exotic palm trees. At the bottom of the hill are the Chinese single-arched stone bridges, decorated with fretwork, multiple-story pagodas (left and centre) and statues of birds (on the right). We also see, in the foreground, a nine-storey pagoda on the left with ornaments at the top, and a two-storey bell tower on the right, with a lantern and ribbons suspended from the top, which is reminiscent of the tugh, or the Turkish crescent, the symbol of rank of the Ottoman military elite.Footnote 57 In between these two tall structures is an opening in the front fence – decorated with fretwork and two neoclassical vases – which invites the viewer into the landscape. These diverse features of Chinese, Turkish and European landscapes obviously do not belong to one locale but reveal an assortment of various exotic features. This is especially evident when we note that some features have no logical place in the landscape; for instance, the three bridges are suspended over the water without being connected to land or to other bridges.

Figure 3. Title page of The Travellers, or Music's Fascination. Newberry Library, Chicago (VM1503. C825t).

The visual collage of exotic features shown on the frontispiece to the score accurately represents Corri's musical plan for the opera. The overture of the opera similarly presents an encyclopaedic compilation of melodies, as underscored by its title: ‘A characteristic overture—Comprehending the melodies of the different Nations as introduced in the Opera or the Travellers, or Music's Fascination.’Footnote 58 Each section of Corri's overture is designated by a subtitle, identifying the nation to which the music refers, including ‘China’, ‘Turkish march’, ‘Spanish fandango’, ‘Pas Russe’, ‘German waltz’ and ‘Italian, Scotch, Irish, and British airs’. Corri's overture features more of a scholarly, encyclopaedic project, resembling Rousseau's Dictionnaire de musique (1768) or William Crotch's Specimens of Various Styles of Music: Referred to in a Course of Lectures, Read at Oxford & London in giving the melodies of different nations.Footnote 59

In fact, Corri's quasi-scholarly agenda to trace music's development from ancient China to modern England may have been motivated by Burney. The connection between Burney's writing and Corri's opera needs to be first traced back to their initial encounter. In 1770, Burney met the Italian composer Corri in Rome. Burney was captivated by performances of a talented couple, ‘ingenious composer’ Corri and his wife, Alice Bacchelli, whom Burney noted had a ‘brilliancy and variety of stile [sic]’.Footnote 60 This encounter with Burney in Rome led the Corris to move to Edinburgh in 1771 with an invitation from the Musical Society of Edinburgh to conduct concerts at St Cecilia's Hall. When other business enterprises failed, Corri moved to London and began a music publishing company around 1790.Footnote 61

More fascinating than Burney's role in Corri's emigration, however, are the ways that Burney's scholarly interest in China furnished Corri's operatic project and compositional choices. For example, some of the items Burney eagerly waited and received upon the return of the Macartney embassy were Chinese instruments: ‘Another chest of instruments, and a gong were added to the collection by the kindness and liberality of lord Macartney.’Footnote 62 It is well documented that the members of the embassy heard gongs; for example, Sir George Leonard Staunton remarked on the power of the instrument in volume and its ability to be heard at a distance.Footnote 63

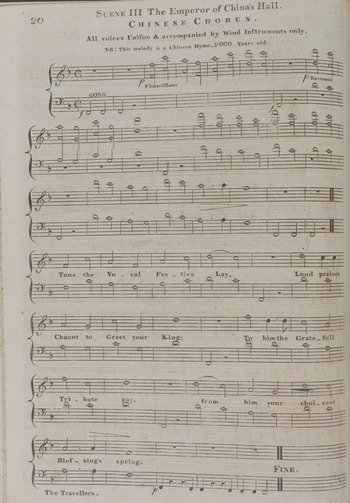

Likewise, Corri's musical evocation of China incorporates the gong. Right at the start of the opera's overture, a gong is featured in the fifth bar. Later in Act I, entitled ‘The Emperor of China's Hall’, three strikes of the gong begin the third scene, which also features a melody, identified as a ‘Chinese Hymn 2000 years old’ and performed by a Chinese chorus with all voices in unison, accompanied by wind instruments and gong (Figure 4). In her fascinating study of the gong, Gundula Kreutzer connects the British vogue for travel and seafaring with the preference for and availability of the gong in a theatrical context: ‘Dramaturgically, this step was likely motivated by precisely the voyaging context in which the British had first encountered the gong.’Footnote 64 Kreutzer explains the result of this connection within the dramatic context of the opera:

Its unlikely plot unabashedly cashed in on the contemporary vogue for exotic travels … In line with the spectacular sets and costumes for which the production became known, this narrative pretext allowed composer Domenico Corri to infuse his score with all manner of exotic musical referents, proudly identified in vocal score and first paraded in the overture.Footnote 65

Figure 4. The Travellers, or Music's Fascination, Act I, scene 3. Newberry Library, Chicago (VM1503. C825t).

Corri's ‘exotic musical referents’ stem from the knowledge supplied by Burney. The provenance of the pentatonic melody, labelled as a ‘Chinese Hymn 2000 years old’, is not identified by Corri, but its source can be traced to Burney's indispensable source for Chinese music, Amiot's Mémoire.Footnote 66 In fact, in his article on Chinese music, Burney describes this hymn as one ‘that is annually sung by the Chinese with utmost pomp, reverence, and solemnity, in honour of their ancestors, in the presence of the emperor’.Footnote 67 In the third part of the Mémoire, Amiot discusses some of the ways in which the Chinese performed their music, including one of the most traditional and sacred rites called the ‘Cérémonie en l'honneur des Ancêtres’.Footnote 68 He reproduces various components of the ceremony honouring ancestors, including a hymn tune transcribed in European notation, a translation of the hymn text and an illustration of the arrangement of musicians and dancers, allowing European readers to better imagine the ritual.

Corri's melody of Act I, scene 3 corresponds to the first part of Amiot's transcription (Figure 4). Amiot's melody is pentatonic and subdivided into eight phrases. As indicated by Amiot, the tempo is slow, très lentement, and the rhythm consists of semibreves. Corri's melody is likewise based on the same pentatonic scale of F, G, A, C and D, and the only change is the reduction of the original eight-bar melody into four phrases by changing the semibreves to minims. While Amiot notates the hymn tune for voices only, he provides instructions for the instruments:

As for the instrumental accompaniment, when the voices sing the word see, one plays one stroke on the hoang-tchoung bell, which is to say F, because the piece is in this key, and the word see is expressed by the note koung, or F.Footnote 69

Corri's opening emulates Amiot's description by scoring three Fs to be played on the gong (Figure 4, bb. 1–2). The exact Chinese instruments are not used by Corri, but his selection of gong, flutes, oboes and bassoons attempts to imitate the original instrumentation, including ‘les cloches’ (bells), ‘les tambours’ (drums), cheng (mouth organ), end-blown flutes and transverse flutes.Footnote 70 Not only does Corri follow Amiot's description for the opening of the piece, but he also conforms to the way in which each verse is set:

At the end of each verse, one plays the lien-kou; at this signal, the voice and all the instruments stop. After a brief rest, one plays once on the l'yng-kou, immediately after that on the hiuen-kou; following that, a second and third stroke on each of the two drums, and after that one gives a stroke on the bell and the voices begin the next verse. It is the same for all the verses.Footnote 71

Corri similarly marks the end of each verse with an F played on the gong, followed by a minim rest (Figure 4, b. 7, b. 12). In addition to the relatively close preservation of Amiot's melody, Corri's designation of the unison chorus, accompanied by wind instruments, maintains the ceremonial performance practice described and illustrated by Amiot.

Furthermore, the ceremonial music Corri features in the third scene of the opera, ‘The Emperor of China's Hall’, might come close to what the members of the embassy heard and experienced. When they encountered the emperor, as described by Macartney and Hüttner, they heard the kinds of music similar to Corri's scene. On 17 September 1793, the emperor's birthday, Macartney writes in his journal:

Slow, solemn music, muffled drums, and deep-toned bells were heard at a distance. On a sudden the sound ceased and all was still; again it was renewed, and then intermitted with short pauses … . At length the great band both vocal and instrumental struck up with all their powers of harmony, and instantly the whole court fell flat upon their faces … . The music was a sort of birthday ode, or state anthem.Footnote 72

Hüttner wrote of a similar experience with more musical detail and emotional reaction: ‘When the emperor had ascended the throne and a religious silence had spread over all, we were surprised by the ravishing sounds coming from the background of the great tent.’ Then he continued with a description, which Irvine calls ‘the power of sublime listening’:

The sweet timbre, the simple tune, the clear mode, the solemn progression of a slow hymn gave, to my soul at least, that vibration which transports susceptible multitudes in unknown regions, but which never can be described by a cold analysis of its reasons.

The lofty rhetoric is balanced with a more concrete description of instruments heard, although initially it was difficult for Hüttner to distinguish the voice from the instruments: ‘I was uncertain for a long time whether I was hearing human voices or the sound of instruments, until the latter were noticed by some of our party. They consisted of stringed instruments and a kind of bamboo panpipes.’ Then Hüttner noted that ‘the hymn resembled the church-tunes of the Protestants, but had no middle voices’.Footnote 73

Although it is not possible to know for sure that the music Macartney and Hüttner heard was the exact melody catalogued by Amiot, and subsequently used by Corri, the efforts of Corri to incorporate an ‘authentic’ musical source is noteworthy.Footnote 74 A similar approach was used for the stage backdrop for the same scenes, with the exterior of the ‘Emperor of China's Palace’ and the ‘Hall of Presence in the Palace’, which were described in the libretto to have been ‘painted from a correct drawing of the palace of Pekin’ and ‘represented at Drury-lane in a correct facsimile of that which appertains to the court of Pekin’.Footnote 75 The embassy's visit of the Qianlong emperor took place in his summer palace in Jehol and not his palace in Beijing; however, given that Alexander produced many vivid sketches of people, landscape, landmarks and encounters during his time in China and their wide circulation as prints and illustrations, it is likely that the set designer of The Travellers used Alexander's drawings as the basis for the first act.Footnote 76 Hence, the incorporation of actual musical and visual sources and empirical knowledge from the embassy sets Corri's opera apart from the vogue for chinoiserie – imitations of Chinese style popular in porcelain, tapestries, wallpapers and garden designs – that was prevalent in eighteenth-century Europe.Footnote 77 The Travellers, then, exemplifies ‘empirical observation’ of the Chinese soundscape and landscape, conveying a changing European attitude towards China.Footnote 78

Imperialistic attitudes in the operatic response to the Macartney embassy

While Corri's effort to incorporate sources, such as the melody from Amiot via Burney and the set design citing a ‘correct facsimile’, demonstrates a keen interest in presenting a ‘realistic’ depiction of China, the opera's ending with the Chinese prince's decision to stay in England adds a further complexity to the interpretation regarding the embassy. The opera's final message could not make more clear the superior position of Britain with the prince who does not return to China. Confirming this point is the final chorus, which sings repeatedly: ‘That all mankind may see in Britons great and free; That England still shall be, protectress of the main and mistress of the world.’ With the dramatic plan that outlines the progress of music that ends in Britain, the opera seems to participate in an emerging ‘imperialist discourse on China’.Footnote 79 Williams explains such a perspective:

If British officials had begun the decade with fantasies of a union between two equal global empires—the Sovereign of the Seas meeting the emperor of the Middle Kingdom—they had by its end moved closer to Macartney's metaphor of China as a rotting tree or anchorless ship, ready for British intervention and direction.Footnote 80

Similarly, historian Krystyn Moon argues that the opera's narrative about tracing the progress of music from ‘lowest’ China to ‘highest’ England previews an imperialist attitude, evident in later writings:

The Travellers, with its exotic settings and an aristocratic protagonist, had all the elements for an elaborate spectacle; however, the role of music makes this production something quite different. By organizing The Travellers as a progression from lowest to highest in musical development, Corri and Cherry created a hierarchy similar to that found in European and American writings on Chinese culture.Footnote 81

Corri's operatic project comes close to restating the embassy's agenda of British advancement, ‘the opportunity it afforded’ as Macartney put it, ‘of showing the Chinese to what a high degree of perfection the English nation had carried all the arts and accomplishments of civilized life’.Footnote 82 With the view of the progress of music paralleling scientific advancements, music with harmonic complexity was considered yet another sign of European progress, and was seen as lacking in the Chinese.Footnote 83

However, beyond the specifics of the opera and its broader theme supplied by Burney, Corri's The Travellers also reflects an ambivalent stance on Chinese music and culture, and circles back to Burney's uneasiness with his scholarly outlook in regard to China. As Irvine argues, Burney was hesitant about ‘the rise of counterpoint and harmony as indexes of westernized modernity and progress and … the fall of China from exemplar to object of pity’.Footnote 84 Unfortunately, there is no record of Burney's attendance of The Travellers, but it is likely Burney saw a performance of the opera at Drury Lane, while he was working on his article on Chinese music, which he started in 1801, but which was not published until 1819. Most significantly, the novelty of Corri's work inheres in the ways in which first-hand experiences of the embassy and Burney's scholarly outlook were melded into a basis for an opera. Furthermore, the opera is, in a way, a belated response to the tributary dramas that entertained the British guests in Jehol and one that specifically acknowledged the Macartney mission and previewed its premature return. Perhaps as an answer to the Qianlong emperor's disappointing dismissal of the British mission and the gifts brought to him, the opera upholds the message of the mission, as Macartney articulated, to demonstrate the British achievements. Above all, it is fascinating to think about how the London theatre-going public in the first decade of the nineteenth century was able to experience and ‘listen’ to Chinese soundscapes and ceremony, via Corri's The Travellers, or Music's Fascination.

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was first presented at the ‘Music between China and the West in the Age of Discovery’ conference at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in May 2018. I am grateful to the conference organisers and participants for their questions and insightful comments, in particular, Thomas Irvine and Joyce Lindorff, as well as to the anonymous reviewers of this journal.