Introduction

In Thailand’s 2019 election, religious questions played an unusually prominent role. Several (minor) parties demanded constitutional change to formally elevate Buddhism to the status of official national religion. One party was investigated by the Election Commission for directly invoking the Buddha in its pursuit of votes. Another was attacked as a threat to the kingdom’s intimate intertwining of sangha (monkhood) and state. A party seeking to represent Malay Muslims in the country’s Deep South advocated for a religion-friendly form of multiculturalism. At the same time, a number of parties, among them the military junta’s proxy party, were conspicuously silent on religion-state relations—not wishing to add religious fuel to Thailand’s already highly polarized politics.

Political parties thus sought to differentiate themselves from one another by staking out distinct orientations vis-à-vis religious identities and institutions. These orientations were grounded in different religio-political ideologies and manifested in a wide range of public policy positions and priorities. This was both unsurprising and surprising. It was unsurprising in relation to the scholarship on Buddhism and politics in Thailand specifically and in Asia generally which has emphasized the role of religion in relation to processes of political legitimation (Jackson Reference Jackson1989, Harris Reference Harris and Harris1999, Reference Harris and Kawanami2016). It was, however, surprising in relation to the conventional wisdom regarding the clientelist and non-ideological character of Thai party politics (Ockey Reference Ockey1994, Reference Ockey2005; Hicken Reference Hicken2013; Kuhonta Reference Kuhonta, Hicken and Kuhonta2014; Chambers and Napisa Reference Paul and Waitoolkiat2020; Ufen Reference Ufen2008, Reference Ufen2012).

To date, the literature on religion and politics and on political parties and elections in Thailand have progressed in mutual isolation. This article seeks to bridge the two by exploring the role of religion in Thai party politics, with a particular focus on the 2019 election. To do so, it analyses the extent to which and how the platforms of Thai political parties contesting the election address religious questions. Particular attention is given to parties that either succeeded in winning seats in the legislature or were highlighted in media coverage of the election campaign as reflecting ‘Buddhist’ platforms or constituencies. Based on an analytical framework that is indebted to recent scholarship on religion and nationalism (Gorski Reference Gorski2017; Soper and Fetzer Reference Soper and Fetzer2018), the article demonstrates that there were striking differences in the extent to which political parties discussed religion in their platforms and election campaigns, and the ways it happened. In short, political parties positioned themselves as either supporters or challengers of Thailand’s monarchy-centred civil-religious nationalism, which I refer to as ‘cosmopolitan royalism’. Thailand’s secular settlement was challenged from two different fronts in the election.Footnote 1 In addition to status quo-oriented parties, voters were presented with diametrically opposed alternatives: Buddhist nationalism and stealthy secular nationalism.

Prior to the 2019 election, these different orientations towards the relationship between religion, nation, and state had found expression as distinct intellectual traditions and, in the case of religious nationalism, as an increasingly prominent social movement. In the run-up to the 2019 election, however, political entrepreneurs ‘particized’ the politics of religio-political difference to an extent that appears unprecedented in recent Thai political history.Footnote 2 While religious nationalist parties failed on one level—winning just a single seat in parliament—they succeeded at another level. Some major parties have moved in a religious-nationalist direction. This is most apparent for the Pheu Thai and the Democrat parties. Others—such as the military junta’s proxy, the Palang Pracharath Party—resisted that temptation. By keeping silent on religious questions, the party presented itself, by default, as committed to the existing monarchy-centred and pluralistic religio-political order.

While the main contribution of the article is empirical and concerned with a single election in a single country, it also introduces and applies an analytical framework to guide the ‘mapping’ of the religious/secular contours of the party-political landscape. This framework could inform scholarship on the interaction of religion, nationalism, and political competition at other times and in other parts of Asia as well. The article is particularly well placed to serve as a point of reference for future research on the interpenetration of the electoral arena and the religious field in other predominantly Theravada Buddhist societies in southern Asia.

The politicization of religion in Thailand

Since the early years of this century, scholars have documented how religious matters have become increasingly politically inflamed—and polarized—in Thailand. This was already becoming apparent under Thaksin Shinawatra’s controversial prime ministership from 2001 until he was toppled by the military in 2006. During these years, a violent Patani Malay-Muslim insurgency erupted in the Deep South (Liow Reference Liow2016, 104–105), triggering a militarization of Thai state Buddhism (Jerryson Reference Jerryson2012), and contributing to the hardening and political radicalization of a distinctive Southern Thai Buddhist identity (Jory and Jirawat Reference Jory and Saengthong2020). The sangha rallied against perceived secularist and Islamist threats (Suwanna Reference Satha-Anand and Cam2003), while splitting over Wat Phra Dhammakaya (a new religious movement accused not only of financial improprieties but also of deviating from Theravada orthodoxy), the succession of the Supreme Patriarch, and Thaksin (McCargo Reference McCargo2012; Katewadee Reference Kulabkaew2013). Santi Asoke, a controversial, heterodox Buddhist movement, played a critical role in the mobilization against Thaksin and his allies (Heikkilä-Horn Reference Heikkilä-Horn2010). The 2006 coup resulted in a military-appointed government that claimed to govern in accordance with dhamma (the Buddha’s teachings), but which failed to resolve any of these conflicts. Indeed, the drafting of a new constitution triggered mass mobilization demanding, unsuccessfully, that Buddhism be declared the national religion. The instigators of the 2014 coup made religious ‘reform’ a priority, but this initiative was met with intense opposition from the sangha establishment (Prakirati Reference Satasut2019, 196–206). It was only after the death of King Bhumibol and the succession of King Vajiralongkorn in 2016 that the government could proceed with significant reforms. These essentially sought to de-politicize and de-bureaucratize religion-state relations by reinforcing and expanding monarchical prerogatives over institutional Buddhism through two amendments to the Sangha Act which invoked ‘ancient royal traditions’. At the same time, the 2017 Constitution introduced novel religious duties for the Thai state, which was now, for the first time, expressly obliged to disseminate ‘the dharmic principles of Theravada Buddhism’ and to ‘prevent the desecration of Buddhism’. While this fell short of the demand from Buddhist nationalists that the new constitution declare Buddhism as the state religion, it represented a controversial step in that direction (Khemthong Reference Tonsakulrungruang2020, 46–48).Footnote 3

These legal changes heralded the adoption, by the junta, of a more muscular approach towards the management of religion. Armed security forces laid siege (literally) to Wat Phra Dhammakaya, while allegedly corrupt and inappropriately ‘political’ monks were purged from the sangha (Borchert and Darlington Reference Borchert and Darlington2017; Katewadee Reference Kulabkaew2019; Larsson Reference Larsson2022). Since then members of the sangha have found it difficult to mobilize in pursuit of favoured causes. As a consequence, monastic networks and organizations at the forefront of Buddhist mobilization, such as those associated with the country’s two state-backed Buddhist universities and the sangha-linked Buddhism Protection Centre of Thailand (BPCT) have been forced to pass the baton to lay persons. A number of organizations and networks have emerged to advocate for cherished Buddhist nationalist causes—such as constitutional amendment—and to alert fellow citizens of alleged nefarious plots to turn the Buddhist kingdom into an Islamic state.

At the same time, and in opposition to both the rise of religious nationalist sentiments and the state’s authoritarian turn in relation to religion, liberals and progressives have insisted that a radical separation of sangha and state is needed if a democratic form of government is ever to be successfully consolidated (Larsson Reference Larsson2017, 552).

In light of this, it would not be surprising if the political opening represented by the 2019 election—after almost five years of severe limitations on all forms of political expression and activity—allowed a wide range of pent-up religious hopes and grievances to seek, and in some instances find, party political expression. Neither, it might be added, would it be surprising, in light of the global return of ‘public religion’ (Casanova Reference Casanova1994), to see the abandonment by conservative political elites of longstanding commitments to secular norms (Hibbard Reference Hibbard2010), the ‘resurgence of religion’s influence on global politics’ (Toft et al. Reference Toft, Philpott and Shah2011, 5), and, more recently, the adoption of ‘hate spin’—religious incitement and offence-taking—as a political strategy in southern Asia (George Reference George2016; Van Klinken and Aung Reference Gerry and Aung2017; Frydenlund Reference Frydenlund, Asbjørn Dyrendal and Asprem2018; Tyson Reference Tyson2021).

Political parties and social cleavages

Families, cliques, and factions rather than political parties have served as the basic building blocks of Thai electoral politics (Ockey Reference Ockey1994, Reference Ockey2015). Through the country’s multiple transitions to democracy, parties have displayed some consistent ideological and sociological differences—pro- versus anti-royalist, centre versus periphery; leftist versus rightist; pro- versus anti-military—but frequent military coups, right-wing repression, and constitutional engineering have prevented the emergence of a stable party system reflecting such politically salient social cleavages (Ockey Reference Ockey2005; Kuhonta Reference Kuhonta, Hicken and Kuhonta2014; Nishizaki Reference Nishizaki2018, 394–395; Prajak Reference Kongkirati2019). Thus, while the 1997 Constitution strengthened political parties, which became more programmatic and more reflective of class and regional cleavages (Hicken Reference Hicken2013), the 2006 and 2014 military coups have sought to reverse these tendencies, deliberately re-engineering constitutions and electoral rules so as to weaken parties by reinforcing incentives for factionalism (Chambers and Napisa Reference Paul and Waitoolkiat2020). In addition, the inclusive nature of official Thai nationalism has also worked against political mobilization on the basis of ethnic differences (Streckfuss Reference Streckfuss2012; Ricks Reference Ricks2019a). Studies of the 2019 election, widely characterized as neither free nor fair, have highlighted the enduring centrality of factionalism, clientelism, and material interests, and the limited salience of social cleavages in Thai electoral politics (Ricks Reference Ricks2019b; Selway Reference Selway2020). As a consequence, in the literature on Thai political parties and the party system, religion is conspicuous by its absence.

There are two minor exceptions. In the 1980s and 1990s, two political factions with religious roots entered the political fray. These were the Wadah faction, representing Malay Muslim constituencies in the southernmost provinces of Narathiwat, Yala, and Pattani, and the Santi Asoke-linked ‘Temple faction’ of the Palang Dharma Party (PDP) (Chambers Reference Chambers2006, 10). While both remain politically active, only Wadah remains in the electoral arena. Chamlong Srimuang, the founder of the PDP and leader of its religious wing, has, since the party’s collapse in 1996, rejected electoral politics in favour of street politics. Occasionally, that rejection has found curious expression, however. In the 2011 election, for instance, the For Heaven and Earth Party, closely associated with Santi Asoke, ran a ‘Vote No’ campaign with the slogan ‘Don’t let animals into parliament’ (Jones Reference Jones2014). These are, however, such marginal phenomena that most recent studies of the Thai political party system and of Thai voting behaviour contain no mention of ‘religion’, ‘Buddhism’, or ‘Islam’ (representative examples include Ockey Reference Ockey2005, Hicken Reference Hicken2013, and Huang and Stithorn Reference Kai-Ping and Thananithichot2018). In light of this overwhelming consensus, it would have been surprising indeed if political parties in the 2019 election had differentiated themselves from their rivals by adopting distinctive religious positions in terms of rhetoric or policy.

Religious, civil-religious, and secular varieties of nationalisms, and their Thai roots

To help organize our thinking about the religious orientation of the parties contesting the 2019 election, this article relies on a conceptual scheme developed in recent studies of the relationship between religion and nationalism (Rieffer Reference Rieffer2003; Gorski and Türkmen-Dervişoğlu, Reference Gorski, Türkmen-Dervişoğlu, Seiple, Hoover and Otis2013; Gorski Reference Gorski2017; Soper and Fetzer Reference Soper and Fetzer2018). This scheme makes a distinction between three different ideal-typical nationalist ideologies which are distinguished by how they imagine the nation’s relationship with religion. Following Soper and Fetzer (Reference Soper and Fetzer2018), the three models of nationalism are labelled ‘religious’ nationalism, ‘civil-religious’ nationalism, and ‘secular’ nationalism.Footnote 4

Religious nationalism and secular nationalism may be thought of as the extreme ends of a continuum. In their most radical versions, religious nationalism seeks to fuse nation and religion, whereas secular nationalism separates the two completely. In between the two poles lies civil-religious nationalism, which advocates for some overlap between religion and nation, while also accepting and appreciating religious pluralism.

Political entrepreneurs inspired by these different ideologies seek to realize what they deem appropriate constitutional arrangements and formal institutional links between religion and state. These range from, in the case of religious nationalism, ‘formal recognition of a religious tradition and multiple connections between that dominant tradition and the state’, to, in the case of secular nationalism, a formal separation and minimal contact between religions and the state. Civil-religious nationalism, finally, is characterized by ‘benign separation’ or ‘pluralistic accommodation where the state recognizes multiple religious traditions’ (Soper and Fetzer Reference Soper and Fetzer2018, 10).

This analytical framework makes it possible for us to place Thai political parties contesting the 2019 elections on a continuum ranging from religious nationalism to civil-religious nationalism to secular nationalism. Party platforms, campaign rhetoric, and policy proposals that impinge on the relationship between religion, on the one hand, and nation and state, on the other hand, provide evidence that allows us to assess whether parties wish to push Thailand in the direction of religious nationalism, secular nationalism, or towards the civil-religious centre.

Before turning to the election, however, it will be useful to briefly describe the sources of these different forms of nationalism in Thailand, as well as the constitutional and institutional status quo—the links between religion and state on the eve of the election. This will allow us to appreciate the significance of the religion-related discourses and policy proposals produced by political parties contesting the election.Footnote 5

Since the introduction of constitutional government in 1932, the dominant strand of Thai nationalism has arguably been one of civil-religious nationalism, characterized by the accommodation of multiple religious traditions.Footnote 6 This nationalism has drawn on both Buddhist scriptures and Western political theory. With regard to the former, it is inspired by the theory of elected kingship found in the Aggañña Sutta (Jory Reference Jory2016, 100–104),Footnote 7 as well as by narratives concerning paternalistic Buddhist kings whose righteousness manifests in their embrace of religious pluralism. With regard to the latter, it has found inspiration in Western liberalism’s commitment to freedom of religion and conscience for individuals as well as to ‘republicanism’ or prachathipatai (Jory Reference Jory and Peleggi2015). This strand of Thai nationalism celebrates kings Ram Khamhaeng (r. 1279–1298), Mongkut (r. 1851–1861), and Bhumibol (r. 1946–2016) as paragons of a form of government that is deemed both enlightened and quintessentially ‘Thai’ in its ability to manifest the teachings of the Buddha in a way that is compatible with liberal and secularist standards of modern ‘civilization’ (Thongchai Reference Winichakul2000, Reference Winichakul2015). Constitutionally, the Thai version of civil-religious nationalism finds expression in the designation of the Buddhist king not as defender of The Faith but rather as satsanupathamphok or ‘upholder of religions’ (section 7 of the 2017 Constitution).Footnote 8 Institutionally, it is manifested in extensive legal and bureaucratic links between the state and ecclesiastic hierarchies (plural), most prominently those headed by the Sangha Supreme Patriarch or Sangkharat (for Buddhism) and the Sheikhul Islam or Chularatchamontri (for Islam).Footnote 9 Accordingly, the word satsana (religion) in the nationalist trinity of chat, satsana, phramahakasat (nation, religion, king) is interpreted as a reference not to Buddhism specifically but rather to the several different religions embraced by Thais. The state’s management of religion has been extensively bureaucratized, with a Religions Affairs Department (RAD) in the Ministry of Culture (ministering primarily to the officially recognized minority religions: Islam; Christianity; Hinduism-Brahmanism; Sikhism) and an Office of National Buddhism (ONB) under the Prime Minister’s Office (Larsson Reference Larsson2018). However, managing Thai religions is also regarded as something of a royal prerogative, in accordance with ‘ancient royal tradition’ (as decreed in the 2016 amendment to the Sangha Act). In short, Thai civil-religious nationalism is fundamentally royalist in conception: ultimately it is the monarch, not any particular religion, that serves as the unifying symbol for a religiously diverse yet ‘Thai’ people (Larsson Reference Larsson2021). I characterize Thailand’s dominant version of civil-religious nationalism as cosmopolitan royalism. It is cosmopolitan in its accommodation and support of multiple religious traditions, and it is royalist because it posits the Thai monarchy as the keystone of the modern nation-state.Footnote 10

Since the 1970s, this monarchy-centred official civil-religious nationalism has, furthermore, been elaborated in ways that impinge on how ‘democracy’ is conceptualized,Footnote 11 namely, as shared sovereignty and mutual dependence of monarch and people—a relationship referred to as ratchaprachasamasai (Connors Reference Connors2008). It is, moreover, manifested in the constitutional phrase which characterizes the Thai political order as a ‘democratic regime of government with the King as Head of State’ (section 2 of the 2017 Constitution).Footnote 12 This has, since the late 1970s, become the political slogan of royalist state ideologues (Kasian Reference Tejapira2016, 227). It is intended to convey that the Thai monarch enjoys a more elevated social position and greater political powers than those typically granted in constitutional monarchies.Footnote 13 The invocation of the slogan in political discourse represents an assertion that democracy in Thailand is a royally guided form of democracy (Somsak Reference Jeamteerasakul2006).Footnote 14 This should be kept in mind when interpreting the constitutional imperative for every Thai citizen to ‘protect and uphold the Nation, religions, the King, and the democratic regime of government with the King as Head of State’ (section 50 of the 2017 Constitution).

This cosmopolitan royalism, predicated on the religious and political hegemony of a Buddhist monarch, constitutes Thailand’s established form of civil-religious nationalism. It is not without rivals.

Thai-style Buddhist nationalism draws primarily on a different image of kingship encountered in the Cakkavatti Sutta and Buddhist chronicles such as the Mahavamsa—that of the Buddhist warrior king with universal aspirations (Sunait Reference Chutintaranond1988; Goh Reference Goh2014).Footnote 15 It also draws on the prophecy of a gradual decline and eventual disappearance of Buddhism from this world. This fuels a perennial anxiety about the ‘crisis’ of Buddhism, which has intensified in Thailand since the late 1980s (Kusa Reference Kusa2007; Katewadee Reference Kulabkaew2013). Buddhist nationalism thus combines celebration of ‘Buddhist’ militancy with fears of an impending apocalypse. King Taksin is a central figure and role model in the Thai Buddhist nationalist tradition (Gesick Reference Gesick and Gesick1983). So too is Phibun Songkhram (prime minister 1938–1944, 1948–1957). Phibun, styling himself as a fascist leader, sought to unify the Thai people in a singular Buddhist identity (Ricks Reference Ricks2008). In pursuit of that goal, Catholics in particular but also Muslims and Protestants became targets of forced assimilation (Reynolds Reference Reynolds2004, 126; Strate Reference Strate2011, 86).

Secular nationalism, finally, is nourished by Western liberal and radical traditions of political thought, ranging from those informing American and French varieties of secularism (Kuru Reference Kuru2007) to Marxist versions of militant secularism and anti-clericalism similar to those that manifested in Cambodia and, to a lesser extent, Laos in the 1970s (Harris Reference Harris2012; Stuart-Fox and Bucknell Reference Stuart-Fox and Bucknell1982). This secularist and anti-monarchical strand of nationalism has few prominent role models in Thai political history, apart, perhaps, from the now-defunct Communist Party of Thailand. The patron saint of the Thai radical tradition, Pridi Phanomyong, adopted an accommodating and supportive approach towards religions throughout his political career, thus illustrating also the attraction of a civil-religious form of nationalism for progressives.

Over the past 30 years, Thailand’s secular settlement has been destabilized by crosscutting pressures emanating from religious nationalist and secularist quarters. This has manifested in an elaboration of the sections impinging on religion-state relations in the 1997, 2007, and 2017 Constitutions. In short, the so-called People’s Constitution of 1997, and the administrative reforms that it mandated, represented a move in a secularizing direction, while the 2007 and the 2017 Constitutions tacked in the opposite direction, towards religious nationalism. In the period leading up to the promulgation of the 1997 Constitution, scholars argued that Thai political elites were becoming increasingly indifferent towards institutional Buddhism as a source of political legitimation (Jackson Reference Jackson and Hewison1997; Kusa Reference Kusa2007). This erosion was reflected, furthermore, in the 1999 National Education Act. If it had been implemented, the Act would have entailed far-reaching reform of the religious bureaucracy. The prospects of revisions to formal religion-state relations ‘caused alarm and panic within the Sangha’, with top ecclesiastics perceiving the new arrangements as a direct challenge to Buddhism’s privileged position within the Thai state, reducing it to one religion among many in the new administrative structure (Kusa Reference Kusa2007, 97). This triggered a reactionary backlash which succeeded not only in stopping these reforms but, furthermore, in reversing course. This can best be illustrated by novel provisions introduced in section 67 of the 2017 Constitution:

The State should support and protect Buddhism and other religions. In supporting and protecting Buddhism, which is the religion observed by the majority of Thai people for a long period of time, the State should promote and support education and dissemination of dharmic principles of Theravada Buddhism for the development of mind and wisdom development, and shall have measures and mechanisms to prevent Buddhism from being undermined in any form. The State should also encourage Buddhists to participate in implementing such measures or mechanisms (emphasis added).

While this section falls short of declaring Buddhism the official state religion, as demanded by religious nationalists, it does establish that Buddhism—of the Theravada variety—enjoys a special position in relation to the Thai state. Among the different Thai religions, Buddhism and its followers are constitutionally designated primus inter pares.

This, then, is the religio-political landscape that political parties going into the 2019 election had to navigate. In addition, they had to negotiate a legal landscape that put limitations on how they might use religious issues to appeal to voters. The 2017 Political Party Act (section 14) prohibited parties from putting forward platforms and policies which ‘may cause division between peoples in the nation’.Footnote 16 Political parties were therefore severely constrained in the degree to which they might deviate from ‘official’ civil-religious nationalism without running the risk of being disqualified for inciting conflict between ethnic and religious communities. In light of this, there were three main ways in which political parties could position themselves.

First, parties could lend support to the civil-religious status quo. Parties satisfied with it could endorse ‘nation, religion, king’ and the ‘democratic regime of government with the King as Head of State’. These are stock constitutional phrases that are repeated, as we shall see, in virtually all Thai party platforms. By committing to them while simultaneously being silent about religious affairs, parties can signal that they support a religio-political status quo in which the king is the chief upholder of religions. Parties fundamentally satisfied with the kingdom’s secular settlement but with ambitions for improving, in some fashion, religion-state relations could complement their displays of loyalty to cosmopolitan royalism with concrete policy proposals designed to benefit religions (plural) by strengthening or reforming the ideological and institutional links between religions and state.

Second, religious nationalists could emphasize the importance of a particular religion while being silent about other religions. They might advocate for a strengthening or elaboration of the state’s ideological and institutional links with their preferred religion. They would not, however, be able to adopt inflammatory rhetoric about religious others without running afoul of the law. In practice, this meant that, at most, parties could put forward vaguely ‘pro-Buddhist’ platforms. However, for legal reasons they had to steer clear of expressing antagonism towards religious minorities.

Third, for radical Thai secularists, advocating for a total separation between religion and state was a theoretical possibility more than a realistic political strategy in a society where the vast majority identify as Buddhists and as religious people. Moreover, secular nationalism would impinge, in a negative way, on the position of the monarch as ‘upholder of religions’. Frontal attacks on religion as such or on the ideological and institutional links between religions and the Thai state would therefore not be an option. But parties could put forward platforms with a ‘secular’ profile by opting to speak about religion as a purely private matter of no public consequence beyond the protection of the religious freedom of individuals. Given the legal and social barriers for the explicit articulation of a political programme of secular nationalism, which would seek to weaken or sever the links between sangha and state (including the throne), we should expect secularist sympathies to find, at most, stealthy expressions in the 2019 election campaign.

Cosmopolitan royalism, Buddhism, and Islam in Thai political party platforms

To what extent and in what ways, then, did political parties contesting the 2019 election address religious questions? To begin answering that question, it is useful to consider how frequently words and phrases that reflect official Thai civil-religious nationalism or impinge on religion-state relations were used in the platforms of different political parties.Footnote 17

As Table 1 makes clear, all but two out of the 31 parties included in the sample make at least one reference to satsana (religion) in their platforms. The exceptions are Palang Pracharath and New Palangdharma. The overwhelming majority of parties that do mention religion, then, make no further reference to any particular religion (such as Buddhism, Islam, Christianity). Belonging to this group, which accounts for a total of 231 seats in the lower house of parliament (out of 500), we find most of the major parties, including Future Forward, Democrat, Bhumjaithai, Charthaipattana, Thai Liberal, New Economics, Puea Chat, and the Action Coalition for Thailand. A number of parties, with a total of 144 members of parliament (MPs), mention Buddhism in their platforms without making any explicit reference to minority religions. Pheu Thai and Chart Pattana belong to this group. Finally, a few parties make explicit reference not only to Buddhism but also to particular minority religions. Prachachat is the only major party in this group of parties, which together have 10 seats in parliament. Three parties—Action Coalition for Thailand, New Palangdharma, and People Reform—which together won seven seats, make reference to a concept that is heavily loaded with religious meaning: dhammacracy (thammathipatai), which may be interpreted as rule in accordance with the universal truths communicated by the Buddha.Footnote 18 These three parties share a connection with the hyper-royalist People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) and its leader Suthep Thaugsuban (for background, see Aim Reference Sinpeng2021).

Table 1 Religion in Thai party platforms, 2019 election: word count

In light of the central role of the monarchy in official civil-religious nationalism, Table 1 also shows the number of times party platforms mention the word kasat (king). Most parties make repeated references to the monarchy. It is noteworthy that one party—Future Forward—does not mention the monarchy even once.

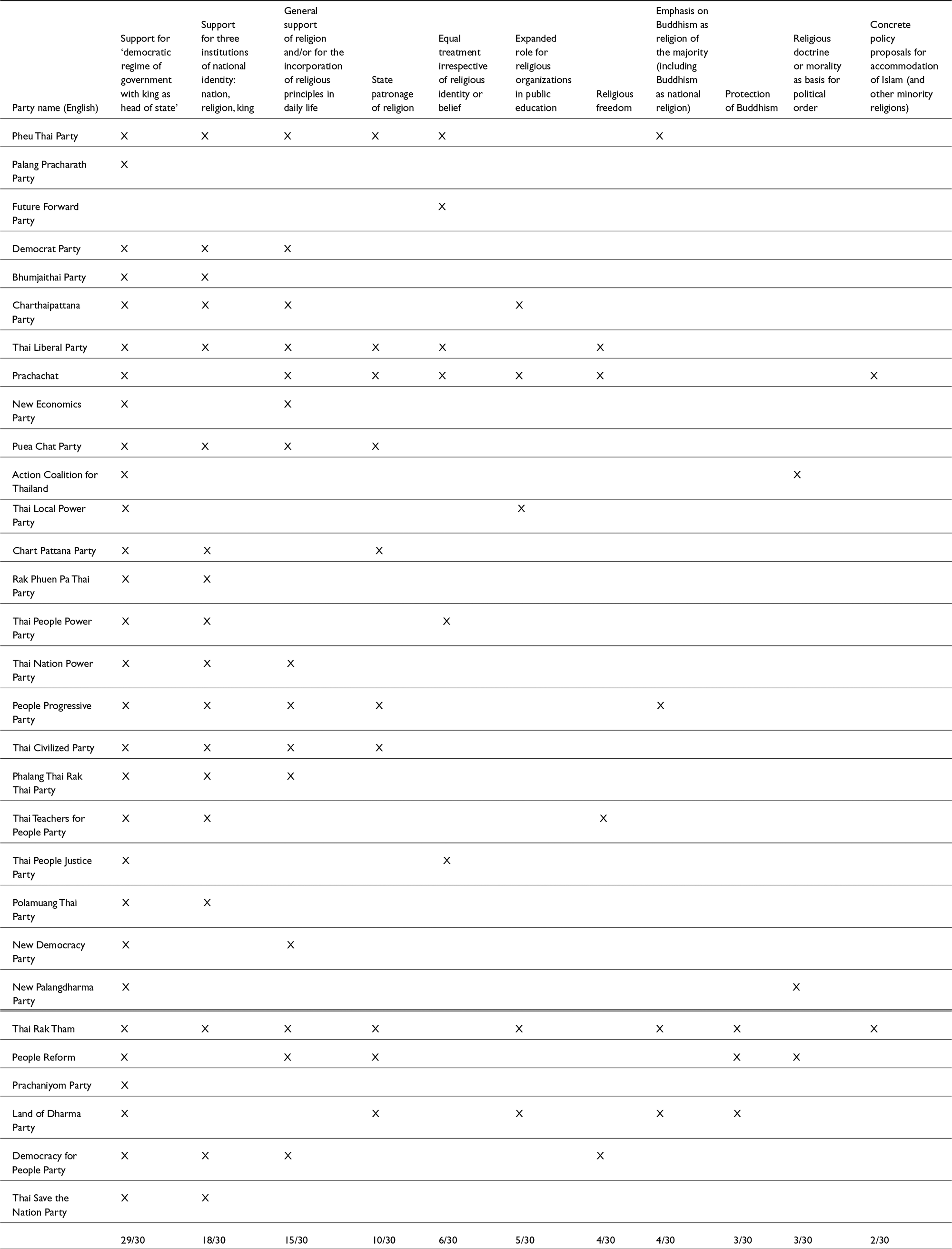

Counting words may provide a rough indication of what importance political parties assign to religion in their platforms. However, to get a sense of their religio-political ambitions, we must also consider to what extent and in what ways these terms are invoked in the articulation of substantive policies. Most commonly, as Table 2 indicates, satsana is invoked by parties (18 out of 29) who simply wish to signal fidelity to the mantra ‘nation, religion, king’. Roughly half of the parties go a bit further than that by indicating general support for religion and piety (15 parties). About a third of the parties emphasize the state’s role as a source of material support for religion (10 parties). Only a small minority of parties put forward more detailed policies and proposals to the electorate. These can be categorized as falling into a secularist group (religious non-discrimination; religious freedom), a religious nationalist group (‘protection’, phithak or pokpong, of Buddhism; Buddhist majoritarianism), and a civil-religious group (promotion of religion in education and religious education; accommodation of Islam and other minority religions; and appeals to ostensibly universal religious morality, centred on conceptions of righteous Buddhist kingship, as the basis for political order). Finally, we may note that these party platforms suggest that ‘nation, religion, king’ has lost its status as the core of Thailand’s civil-religious nationalism. It has been replaced by ‘democratic regime of government with the King as Head of State’—a conception of Thailand’s political order to which all but one of the parties—Future Forward—pledged loyalty.

Table 2 Religion in Thai party platforms, 2019 election: policy elements

To further illuminate how political parties positioned themselves in the 2019 election, the following section will discuss the policy profiles of the different party platforms in greater detail. It will also discuss additional religious elements and links that were highlighted in the course of the election campaign.

Cosmopolitan royalism: Variations on a theme

A number of the major political parties that went on to form the core of the coalition government which took power following the election adopted a minimalist approach to religion. In short, in their party platforms they had said nothing or virtually nothing about religion.

At the extreme end of the spectrum, we find Palang Pracharath, the military proxy party that was created as an electoral vehicle for the 2014 coup group. It did not once mention religion in its party platform. The party did, however, provide clues as to why that might be the case. The party explained that its ideology (udomkan) was a response to the divisions and violent conflicts that had erupted in the country. It would therefore seek to make the country into ‘a liberal and stable democracy that is free from conflict and prospering in every way’. Given that religious issues, especially as regards the Buddhist sangha and coexistence with Malay Muslims in the Deep South, were prominent causes of controversy and conflict during the junta years, it is easy to understand why the party adopted as low a religious profile as possible. Its first priority was to promote and preserve the ‘democratic regime of government with the King as Head of State’. This would in turn provide the basis for the creation of ‘unity among the peoples of the nation’ and ‘public order or good morals’.

Bhumjaithai (meaning ‘Thai pride’) went one step further than Palang Pracharath by pledging that it would ‘honour the institutions nation, religion, king [and] adhere to and maintain the democratic regime of government with the King as Head of State in accordance with the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand’. Satsana gets a mention, but nothing substantive is revealed about the party’s policies concerning religion-state relations. It is noteworthy, however, that the party recruited to its ranks a Pattani politician with an eminent political pedigree: Petchdao Tohmeena, daughter of Den Tohmena, founder of the Malay-Muslim Wadah faction, and granddaughter of Haji Sulong, the Malay-Muslim nationalist leader who was mysteriously made to disappear in 1955. This was a signal as strong as any of the party’s commitment to the religious pluralism of cosmopolitan royalism.

The Democrat Party went one small step further still, by declaring that satsana was among the things it wished to support, alongside education, public health, arts, culture, traditions, good customs, and the security of the citizenry. Interestingly, the party’s platform going into the 2019 election campaign was strikingly different from its previous platform in 2008, which had included numerous references to Islam and also to halal. In the intervening years, the Democrat party had become reluctant to present itself as a party supportive of Islam.

Among the parties that backed Prayuth as prime minister were three that had adopted a distinctive religio-political position: Action Coalition for Thailand (ACT), People Reform Party (PPR), and New Palangdharma Party (NPDP). In their party platforms, these parties all make the pursuit of dhammacracy (thammathipatai) a key component of their ideology. In essence, dhammacracy refers to government by rulers who base their decisions on public interest, truth, rationality, and morality.Footnote 19 It is not associated with any particular form of government or regime type but rather with the righteousness of the ruler.

The discourse on dhammacracy is imbued with particular historical, political, and religious resonances—including but not limited to pre-modern models of righteous Buddhist kingship. Notably, in the mid-1970s the Dhammacracy Party emerged as ‘the most rightist’ political party on the political spectrum: it was closely associated with the arch-royalist Nawaphon movement and the Thai sangha’s leading anti-communist rabble-rouser, Kittiwuttho (Somporn Reference Sangchai1976, 4–5; see also Prajak Reference Kongkirati2008; Ford Reference Ford2017, 260–262). Since the early 1990s, dhammacracy discourse has been revived and popularized by the leading scholar-monk P. A. Payutto (Reference Payutto2006, 10–19). It was subsequently weaponized by conservative and reactionary so-called Yellow Shirts in their struggle to uproot the ‘Thaksin regime’. Finally, it has been incorporated by the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) into Thailand’s 20-year national strategy, which aims to ‘establish a dhammacratic state’ (kansang rat thammathipatai).Footnote 20 By invoking dhammacracy, these three parties thus presented themselves as representatives of a hyper-royalist and ultra-rightist political tradition in which Buddhistic rhetoric on righteous government plays a vital role.

The dhammacratic ideology as articulated by these political parties is strikingly Manichaean. In a genuinely dhammacratic democracy, they posit, only ‘good people’ (khon di) triumph at the ballot box. Apart from protecting the country’s monarchy-centred political order, ACT’s main concern is to reform politics in such a way that ‘evil people’ (khon chua) are unable to rise to power by electoral means. These, then, are the parties for the kingdoms’ self-proclaimed ‘good people’. It is important to note that politics in dhammacratic discourse is conceived of as a struggle between good and evil, rather than as a struggle between Buddhists and religious ‘others’ (as is the case for Buddhist nationalist parties).

The three dhammacratic parties thus align themselves with cosmopolitan royalism by signalling, explicitly or implicitly, commitment to religious pluralism. ACT explains that it is committed to a democratic political system in which the principles of all religions (satsana thang phuang) are integrated. The New Phalangdharma Party’s platform mentions neither Buddhism nor satsana. As its name suggests, it is a spiritual successor to Chamlong Srimuang’s Palang Dharma Party (PDP). Closely associated with a heterodox new Buddhist movement, Santi Asoke, the PDP flourished in the late 1980s and early 1990s on a similar agenda for the moral restoration of Thai politics (McCargo Reference McCargo1997). The NPDP’s silence on religious affairs must be seen in light of its close association with a controversial new Buddhist movement with a long history of conflict and uneasy relations with Thai ecclesiastic and state authorities. While Santi Asoke, which was founded in the 1970s, explicitly rejected the authority of the sangha hierarchy, it has, since joining the anti-Thaksin movement, emerged as one of the staunchest defenders of the traditional Thai establishment (see Heikkilä-Horn Reference Heikkilä-Horn1996, Reference Heikkilä-Horn2010). Given Santi Asoke’s position as a small minority within the country’s large Buddhist majority, prospective NPDP voters have everything to gain from an ideological and institutional framework which—like the civil-religious status quo—continues to tolerate a schismatic Buddhist group like Santi Asoke, even though it is not officially recognized.

PPR does mention Buddhism in its platform, and also invoked the Buddha in its controversial election slogan: ‘Adopting the teachings of the Buddha to solve the troubles of the people is the main task of the People Reform Party’. In the platform, the party declared ‘reform of Buddhism’ to be one of its main goals. The party wanted to ensure that monks follow the monastic law (Vinaya) that temple assets are managed in a transparent manner and that the country’s Buddhists are encouraged to adopt the ‘true’ principles of the Buddha. This reflects a preoccupation with the perceived threat from Wat Phra Dhammakaya to the doctrinal and institutional integrity of the Thai sangha.Footnote 21 Unlike Buddhist nationalists, who emphasize external threats to Thai Buddhism and the sangha, PRP and fellow dhammacrats tend to be concerned primarily with internal threats to Thai Buddhism and in particular, the doctrinal and institutional foundations of the Thai sangha. In contrast with Buddhist nationalists, therefore, the dhammacratic parties do not challenge cosmopolitan royalism or the state’s ideological and institutional links with minority religions.

ACT has a particularly strong connection to the network associated with Buddhadasa (1906–1993), twentieth-century Thailand’s leading Buddhist philosopher (see Jackson Reference Jackson2003). After the 2014 military coup had turned PDRC’s ambitions into a fait accompli, Suthep Thaugsubhan, its front man and former secretary-general of the Democrat Party, and several of his associates ordained as monks at Buddhadasa’s Suan Mokh in Surat Thani province (Dubus Reference Dubus2017, 17). This temple connection remains important to the party. On the ACT’s website, for instance, a quasi-religious vocational college is highlighted as a model for education reform. Bhavana Bhodigun on Samui Island has a close association with the monks at Suan Mokh, and their presence allows the college to incorporate daily sermons and communal meditation sessions into the school’s schedule. Such vocational-cum-Buddhist training is intended to produce the ‘good people’ that the country will need for dhammacracy to flourish.

The leading political parties opposed to the continued role of the military generally aligned themselves with cosmopolitan royalism yet staked out distinctive positions which placed them more-or-less close to the Buddhist nationalist or secularist ends of the ideological spectrum. Most notably, Pheu Thai echoed Buddhist nationalist sentiments when it committed itself to ‘promoting Buddhism as the religion of the majority of the population and other religions as the pillar of morality and ethics’ and for ensuring that ‘the sangha governs itself in accordance with Buddhist principles and the country’s laws’. When Pheu Thai was founded in 2008, its policy platform contained no reference to Buddhism and no reference to the monastic community. Their addition in 2019 arguably signals a desire to attract voters with Buddhist nationalist sympathies. Both before the 2019 elections and in its aftermath, prominent Pheu Thai leaders accused Prayuth-led governments of destroying and degrading Buddhism (Sanook Reference Sanook2016; Thai Post 2020). However, the party did not make substantive religious questions prominent in its 2019 election campaign. Two of the smaller Thaksin-aligned parties which targeted, primarily, Buddhist majority constituencies—Thai Save the Nation Party and Puea Chat Party—adopted positions closer to the status quo by making friendly references to satsana but showing no special concern for Buddhism and the sangha.

Pheu Thai could also signal its commitment to Buddhist identities and institutions in more subtle ways—most notably through its nomination of Sudarat Keyuraphan as the party’s candidate for prime minister. In the preceding decade, Sudarat had engaged in devotional activities which raised her religious profile. These ranged from a pilgrimage to the Thai temple in Lumpini (Nepal) in 2012 to the completion of a doctoral degree in Buddhist Studies at the Mahanikai order’s university in 2018. In the years leading up to the 2019 election, Sudarat had collected a number of awards for services to the faith. Most noteworthy among these was the 2014 World Buddhist Leader from the Bangkok-based organization World Fellowship of Buddhist Youth (WFBY). Sudarat received the award from the acting supreme patriarch, Somdet Chuang, alongside, among others, Wat Phra Dhammakaya’s abbott Thammachaiyo, the Buddhism Protection Centre of Thailand (BPCT), and Anant Asavabhokhin, a billionaire devotee of Wat Phra Dhammakaya and leading financial backer of Thaksin-aligned parties, including Pheu Thai (Khomchatluek 2014). Two years later, the same award was given to Myanmar’s Association for the Protection of Race and Religion (Ma Ba Tha), whose militantly anti-Islamic and anti-Rohingya activities apparently were considered ‘outstanding contributions to the protection of Buddhism’ (Matichon Reference Matichon2016). Through the nomination of Sudarat as the party’s candidate for prime minister, therefore, Pheu Thai gained a front-line figure who had emerged as an associate and ally of prominent lay and monastic proponents of a more muscular and majoritarian form of Thai Buddhist nationalism.

The emergence of a Thaksin-affiliated party with roots in the Deep South—where it won six out of 11 constituency seats—offered one of the most original party platforms with regard to religious matters. The Prachachat Party, founded by the veteran Malay Muslim politician Wan Muhammad Nor Matha out of the remains of the Wadah faction (Daungyewa Reference Utarasint2019, 129), presented a party platform animated by religious concerns—as indicated by the fact that ‘religion’ was mentioned no less than 41 times, Buddhism four times, and Islam eight times. Prachachat’s political programme was centrally concerned with expanding and strengthening the ideological and institutional links between the Thai state and religious communities and organizations. The party supported the development of a ‘multicultural society’ (sangkhom phahuwatthanatham) where religious and other minority identities are respected and supported by the state. The party put forward a raft of concrete policy proposals impinging on religion-state relations. These included expanded state support for Islamic and other religious education; equality in state patronage of religions and religious activities; financial support for religious clergy and officers; expansion of the application of Islamic family law to Muslim communities in areas outside the Deep South; and support for ecumenical activities to promote inter-religious understanding. Prachachat’s policies were not only compatible with cosmopolitan royalism but would, if realized, significantly extend and elaborate its institutional manifestations.

While both Pheu Thai and Prachachat adhere to the overarching religio-political order, there is a stark contrast in their religious sensibilities. While Pheu Thai was positioned to appeal to Buddhist majoritarian sentiments, Prachachat was positioned to appeal to pious Muslims and followers of other minority religions.

Thailand’s cosmopolitan royalism undoubtedly represents the religio-political centre of gravity in partisan politics. In the 2019 elections, most of the major political parties offered no fundamental challenge to dominant ideas and institutions concerning religion-state relations. Even within that relatively narrow range of opinion, however, we can detect some striking contrasts in the extent to which and how party platforms invoked religion and addressed political concerns related to religious life. Generally speaking, the Palang Pracharath, Democrat, Bhumjaithai, and Chartthaipattana parties (which following the election went on to form the core of a coalition government led by Prayuth as prime minister) avoided overt politicization of religion. They did so by either not mentioning satsana (a strategy adopted by Palang Pracharath alone) or by making no references to specific religions such as Buddhism and Islam. Among some of the parties opposed to the continued political influence of the 2014 coup group we find, in contrast, a greater willingness to incorporate religious themes in their platforms. This is indicated by their references to Buddhism and the sangha (Pheu Thai) or to Buddhism and Islam (Prachachat). In so doing these two parties included in their platforms policies that were designed to appeal to voters for whom the status and welfare of institutionalized religion and their representatives—Buddhist monks (Pheu Thai) and Muslim imams, khatibs, and bilals (Prachachat)—were issues of significant concern.

Parties of assertive Buddhist nationalism

At the Buddhist nationalist end of the political spectrum, media reports on the election campaign highlighted two particularly prominent and newly founded ‘Buddhist’ parties: the People Progressive Party (PPP) and Land of Dharma Party (LDP) (Nanchanok Reference Wongsamuth2019). Challenging the religious pluralism of cosmopolitan royalism, both parties contested the election with platforms and campaign rhetoric which advocated for a more complete fusion between Buddhism and the state.

LDP most clearly positioned itself as the champion of the interests of the sangha’s ecclesiastic hierarchy. Its political platform contained a subsection on Buddhism (rather than religion), with 16 policy proposals. Most prominent among them was the demand that Buddhism be declared the national religion. In addition, the party pledged to work to secure the establishment of a Ministry of Buddhism, a state-backed Buddhist Bank (modelled on the Islamic Bank of Thailand which had been established in 2002 by the Thaksin Shinawatra government), a special fund for the protection of Buddhism, and an Institute for Nuns (sathaban mae chi). The party also proposed that laws be enacted for the protection of Buddhism, the empowerment of monks to propose and oppose laws affecting Buddhist affairs, and reform of the National Office of Buddhism. The sangha should also, the party proposed, be empowered to manage itself—such that sangha reform lay in the hands of its members. LDP championed some rather niche issues. For instance, it wanted forest temple abbots and wandering meditation monks (phra thudong) to be officially recognized as, respectively, Royal Forest Department staff and staff assistants. On issues large and small, LDP consistently championed initiatives aimed at achieving a more complete fusion between Buddhism and state.Footnote 22

In comparison with LDP, PPP’s platform was less elaborate and less concerned with the political and bureaucratic interests of the monkhood. It was more concerned with preserving and nurturing religious piety in general. PPP’s majoritarian inclinations could be detected in its insistence that the allocation of state subsidies for religions should be proportional to the religious demography of the population. It was only on the campaign trail that PPP revealed policy preferences that justify its inclusion in the Buddhist nationalist category. Most notably, PPP emerged as an advocate of the establishment of Buddhism as the de jure religion of the state, which would serve, the party promised, as the starting point for a state-backed transformation of Thai society into a more genuinely Buddhist society (Phak Prachaphiwat Reference Prachaphiwat2019a). PPP also advocated for the establishment of a Buddhist bank and for government salaries of up to 9,000 baht per month for temple wardens (waiyawatchakon) (Phak Phrachaphiwat Reference Prachaphiwat2019b, Reference Prachaphiwat2019c). Like LDP, then, PPP also sought to strengthen the ideological and institutional linkages between Buddhism and the Thai state—in ways which implicitly, if not explicitly, challenged the more pluralistic thrust of cosmopolitan royalism.

Both parties were fronted by figures who had emerged as important voices in the religious debates and controversies that had erupted in the wake of the 2014 coup. These included conflicts over the appointment of a successor to the Sangha Supreme Patriarch, military-backed initiatives to ‘reform’ Buddhism, and the ONB’s attempts to stamp out ‘corruption’ within the sangha, including but not limited to alleged financial malfeasance by Wat Phra Dhammakaya and its abbot, Thammachaiyo (see Larsson Reference Larsson2022).

LDP grew out of the Buddhist Association of Thailand (samaphan chaophut haeng prathet thai). The party’s logo was virtually indistinguishable from that of the BAT, and its president, Banjob Bannaruji, was the party’s candidate for prime minister, while its secretary, Korn Midi, was the party’s leader. Since its establishment in 2015 BAT had sought to mobilize Buddhist nationalists for the establishment of Buddhism as Thailand’s national religion. In the years leading up to the founding of LDP, Banjob, based on an impressive record of Buddhist scholarship and close association with the top echelons of the sangha, had established himself as a leading promoter of Buddhism as the national religion, defender of Wat Phra Dhammakaya, and vehement critic of Islamic influences in Thailand. Korn Midi was known as a leader of the Red Shirts in Nonthaburi.

PPP, in turn, was founded by Somkiat Sonlam, a former Pheu Thai MP from Nakhon Sawan; Chaiyanat Yatchimphli, a retired major general and Army chaplain who is well known for his promotion of Buddhism through his leading positions in prominent lay organizations (Foundation of Pali and Dhamma Graduates Association of Thailand; Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University Alumni Association); and Nanthana Songprapha, a former MP from a prominent political family in Chai Nat. All three were reported to have strong connections to Wat Phra Dhammakaya (Khomchatluek 2018, Bangna Reference Bangpakong2019).

Both parties were, as this suggests, founded on the back of important lay and monastic networks. The dismal election results—one party-list seat for PPP, no seats for LDP—revealed the weakness of an electoral strategy built on the assumption that championing the interests of institutional Buddhism and Buddhist networks would mobilize voters. Nevertheless, both parties have been able to convert their electoral failure into political capital. Like many smaller parties, PPP was persuaded to back Prayuth Chan-ocha for prime minister, and PPP party leader Somkiat Sonlam was rewarded with a position as adviser to the prime minister in the Ministry of Culture. PPP’s deputy leader Chaiyanat Yatchimphli was appointed adviser to the House of Representative’s Sub-committee on Religion. In January 2021, LDP leader Korn Midi was appointed adviser to the House of Representative’s Committee on Religion, Art, and Culture.

The most prominent champions of Buddhist protectionism in the 2019 elections have thus been able to secure positions as advisers to the executive and the legislature. This may be interpreted as one manifestation of the constitutional provision concerning ‘measures and mechanisms’ for the protection of Buddhism.

Stealthy secularism

Among the parties contesting the 2019 elections, the Future Forward Party stands apart for its implicit rejection of Thailand’s politically regnant form of civil-religious nationalism—manifested most clearly in the absence in the party’s platform of any explicit reference to section 2 of the 2017 Constitution. The party could therefore be understood as advocating a majoritarian form of democracy—one not conditional on the monarch. The party’s approach to religion-state relations is similarly indirect. The party platform says nothing about the separation of religion and state; it only references religion in the context of declaring support for principles of non-discrimination and respect for diversity of all kinds, including but not limited to religious differences.

Though FFP adopted a low religious profile in its platform, it was unable to avoid the issue in the election campaign. Party leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit’s stance on religion became the subject of considerable controversy. In an interview in 2017, Thanathorn had argued that the Thai state should not provide patronage to Buddhism or any other religion. Thanathorn had explained that the state’s support for Buddhism made the conflict in the Deep South more difficult to resolve because it alienated Malay Muslims. Therefore, Thanathorn argued, ‘the state should withdraw from religious affairs and should not provide patronage to any religion’. The state should simply respect religious freedom and stay out of religious disputes—such as those, Thanathorn noted, over Wat Phra Dhammakaya (Thawephon Reference Khummetha2018). When these comments were brought to the attention of voters, Thanathorn distanced himself from them. He explained that his comments had been taken out of context, that they were made a long time ago, and that they reflected private opinions and not party policy (Prachathai Reference Prachathai2018). But Thanathorn did not clarify the party’s policy with regard to religion-state relations.

FFP became embroiled in further religion-related controversies when Thanathorn adopted a principled stance, based on international human rights norms, in response to questions about the prospect of an influx of Rohingya refugees from neighbouring Myanmar. In April 2018, Thanathorn had criticized the government’s policy of pushing boats with Rohingya refugees back out to sea. He promised that if FFP held the reins of government, it would lend the Rohingya refugees a welcoming hand and work through ASEAN for a permanent solution to the conflict in Myanmar (Thanathorn Reference Juangroonruangkit2018). Thanathorn repeated this position in the run-up to the election, exposing the party to attacks which played on Buddhist-nationalist fears of a Muslim invasion (TNews 2019). As a consequence, potential voters, particular in the North and Northeast, frequently challenged campaigning FFP candidates over what they perceived as the party’s anti-Buddhist attitude.Footnote 23

In a speech to rural voters in Khon Kaen, FFP Secretary-General Piyabutr Saengkanokkul sought to lay these religious anxieties to rest. He observed that FFP’s surge in the polls had resulted in the party being subjected to attacks and slander of all kinds. Worst were the accusations that the party represented a ‘danger’ to Buddhism. Responding to these Piyabutr sought to establish the party’s religious credentials:

They say Khun Thanathorn doesn’t like religion, that he doesn’t want Buddhism. Bah! Thanathorn ordained at a forest temple here in Khon Kaen province! … Next time someone says that the leader of this party is not religious, that this party is not religious, tell them loudly: that’s bullshit! (Anakhot Mai Reference Mai2019, at 3:18–4:22 minutes).

Piyabutr’s rejoinder illustrates how FFP tried to fend of accusations of religious irreverence and lack of concern for the flourishing of institutional Buddhism not by spelling out, in greater detail, its policy preferences concerning the ideological and institutional links between religion and state, but rather by pointing to evidence of the party leader’s religiosity. This reinforced the party’s secular profile: religion was a matter of personal choice, not public policy.

Following the party’s strong performance in the elections, Thanathorn and FFP were subjected to a series of legal challenges. These resulted in Thanathorn being banned from politics for 10 years and FFP dissolved. This, in turn, triggered protests led by students and youth who had flocked to the party, attracted by its progressive policies and social media-savvy campaign. The students demanded political reform along similar lines championed by FFP in the election campaign—but some went much further by demanding the withdrawal not only of the military from politics but also far-reaching reforms of the monarchy (Prachathai Reference Prachathai2020). These demands did not, it is important to note, touch on the monarchy’s role in relation to Buddhism or religion more broadly. However, in an interview on these challenges to the role of the monarchy in Thai politics, Thanathorn highlighted among other ‘undemocratic’ things that needed to be reformed the fact that the Thai king has ‘the power to appoint the head pontiff’ of Thai Buddhism (Rachman Review Reference Review2020, at 09:32–10:27 minutes).

While it is true that the FFP did not contest the 2019 election on an overtly ‘separationist’ agenda, the contents and silences of the party platform as well as comments made by the party leader during and after the election campaign, provide grounds for thinking that FFP, among the parties contesting the 2019 election, was positioned closest to the secular nationalism end of the ideological spectrum. FFP recognized the relevance of religion only in relation to questions of non-discrimination of individuals. Neither particular religions nor general religious piety had any place in the party’s political vision.Footnote 24 In light of Thanathorn’s comments on religion-state relations before and after his adventure with FFP, plus the fact that the party chose—as the only party to do so—to not even pay lip service to cosmopolitan royalism, it seems fair to surmise that the party’s agenda for fundamental political and economic restructuring of the Thai polity might also pose a serious challenge to the existing secular settlement.

Conclusion

On the surface, Thai electoral politics has little to do with religion. Regional, urban/rural, and socio-economic cleavages are more readily apparent as key features of electoral politics. Ideologically, parties are defined primarily by their attitudes towards majoritarian institutions (elections and parliament), on the one hand, and counter-majoritarian institutions (the military, the monarchy, the constitutional court, and the appointed senate), on the other. Yet, as this article has demonstrated, the 2019 election offered voters the opportunity to vote for parties with distinctive religious orientations. In essence, these were choices between different conceptions of Thai nationalism. The vast majority of parties backed the ‘official’ civil-religious nationalism according to which the monarchy is the focus of loyalty for citizens of all faiths and the Thai state acts as patron and protector of religious institutions and organizations belonging to different faiths. This cosmopolitan royalism was challenged from two directions. From the Buddhist nationalist end of the spectrum, some parties sought a greater degree of overlap between the state and Buddhism, at the expense of minority religions. Closer to the secular nationalist end of the spectrum, the FFP adopted an ambiguous stance which nevertheless suggested that it would prefer greater distance between religion and state.

Moreover, it is important to recognize that the overarching category of cosmopolitan royalism hides important differences both within and between the two major blocs contesting the election. Within the pro-military alliance, the main military proxy party ignored religion, while a number of smaller parties appealed to religious sensibilities by invoking dhammacracy—a concept of virtuous Buddhist rule that in the preceding decade had been weaponized in opposition to the alleged corruption of electoral politics by Thaksin-associated parties. Among the latter, we likewise find parties with distinct religious profiles. Most notably, the Pheu Thai platform’s concern for the promotion of Buddhism and sangha self-governance can be interpreted as dog whistles aimed at Buddhist nationalists. The party’s choice of candidate for prime minister is further evidence that the party sought to attract religious nationalists without alienating voters satisfied with the official civil religion. This stood in stark contrast with Prachachart’s pietistic commitment to multiculturalism and the strengthening of the state’s ideological and institutional linkages with Islam in particular.

Further research is needed to establish whether and to what extent Thai voters respond to the parties’ different religious appeals. That said, analysis of survey data indicates that there were significant differences in the religious identities and beliefs of the supporters of the leading parties. Most notably, Palang Pracharath voters were more religiously diverse than voters for Pheu Thai and Future Forward. Close to 16 per cent of voters backing this pro-Prayuth party identified with religions other than Buddhism. The corresponding figure for the Pheu Thai party was a mere 1.2 per cent. The secularist orientation of FFP is reflected also in its support base. Only 2.8 per cent of FFP voters identified as very religious persons, whereas 16.9 per cent of Palang Pracharath voters did so. The very small number of voters who identified as non-religious persons flocked to FFP (Larsson and Stithorn forthcoming). This suggests that the differences in religio-political orientation manifested in the party platforms, policies, and rhetoric analysed in this article may have affected voter perceptions of the different parties.

The political salience of religious matters in Thailand’s 2019 election indicates that Thailand, like Indonesia, has experienced a shift in the ideological centre of gravity from a distinctive model of ‘democratic cosmopolitanism’ (Bourchier Reference Bourchier2019; see also Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2019, 54) towards authoritarianism and religious nationalism. These tendencies were manifested and institutionalized in the 2017 Constitution. The rise of a progressive and stealthily secularist party, the FFP, represented a valiant but perhaps naive attempt to reverse course. The crippling of the secularist challenge through the dissolution of FFP and the simultaneous co-optation of the leaders of the Buddhist nationalist parties by the government and the House of Representatives in the aftermath of the 2019 election suggests that Thailand may continue its slow slide towards a more assertive Buddhist nationalism.

Further research should also incorporate more explicitly comparative perspectives. The conceptual and analytical framework which has informed this article could serve as a model for a wider effort to map the electoral landscape in other Theravada Buddhist societies in southern Asia, as pertains to both the past and the present. While numerous scholars have noted the recent rise of Buddhist nationalism as a salient factor in the electoral politics of both Sri Lanka and Myanmar, no one has, as far as I am aware, sought to describe and analyse in any more systematic fashion efforts by rival political party elites to champion different conceptions of the relationship between religion, nation, and state. Yet how they do so, and with what success, is critical for understanding both stability and change in secular settlements.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Vatthana Pholsena, Andreas Ufen, and the journal’s reviewers and editors for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. The research benefitted from financial support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Program for Research and Innovation within the framework of the project CRISEA (‘Competing Regional Integrations in Southeast Asia’), grant agreement No. 770562/Europe in a Changing World, Engaging Together Globally.

Competing interests

None.