Case-based discussion is one element of the assessment programme for doctors training in psychiatry. It is, in addition, proposed to form part of the evidence used in enhanced appraisal, which is a fundament of the procedure for recertification and revalidation for established psychiatrists. The focus of case-based discussion (or case-based assessment) is the doctor's clinical decision-making and reasoning. The method can be used for both formative (assessment for learning) and summative (assessment of learning) purposes (Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board 2010a).

The assessment

Authenticity is achieved by basing the questions on the doctor's own patients in his or her own workplace. The assessment focuses solely on the doctor's real work and at all times is concerned with exploring exactly what was done and why and how any decision, investigation or intervention was decided upon. A case is chosen with particular curriculum objectives in mind and then discussed using focused questions designed to elicit responses that will indicate knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviours relevant to those domains. Assessors require training, particularly in question design and giving feedback, because case-based discussion is intended to assess the doctor's reasoning and judgement and it is important to guard against it becoming an oral test of factual knowledge or an open discussion of the patient's problems. Case-based discussion in postgraduate medical education, in common with other workplace-based assessments, must always be accompanied by effective feedback to aid performance improvement. Therefore, assessors must also be skilled in offering timely and effective feedback (Reference Brown and CookeBrown 2009).

Case-based discussion can be used for doctors at any level of training or experience. Given its importance, it is vital to describe its origins, why it is an effective method of assessment and how it must be deployed. Therefore, we describe its genesis in medicine and in UK psychiatry and provide guidance on how to use the instrument successfully, before considering its use with established psychiatrists.

Background

Origins of case-based discussion

Case-based discussion is one of a family of workplace-based assessment methods that have developed from an instrument in Canada and the USA called chart-stimulated recall (CSR). In CSR an assessor, having reviewed a selection of patients’ charts (clinical records), discusses with the practitioner data-gathering, diagnosis, problem-solving, problem-management, use of resources and record-keeping to validate information gathered from the records.

This method was shown to have good face and content validity (Reference Jennett, Scott and AtkinsonJennett 1995). In addition, it has been demonstrated that (with sufficient sampling) good levels of reliability (Reference Norman, Davis and LambNorman 1993) and validity with assessor training (Reference Solomon, Reinhardt and BridghamSolomon 1990) can be achieved. Furthermore, in emergency medicine Reference Maatsch, Huang and DowningMaatsch etal(1984) demonstrated concurrent validity in the relationship between CSR scores and results from the American Board of Emergency Medicine examinations.

Reference Jennett and AffleckJennett & Affleck (1998) produced a major literature review on case-based discussion. It includes examples in the literature of chart audit and case (note) review skills being considered as a dimension of clinical competence extending back to the 1970s, for example by Reference Goetz, Peters and FolseGoetz etal(1979).

Work in the USA using CSR as part of the recertification of practising doctors showed scores that were highly correlated with performance in a clinical examination using standardised patients. It also showed that CSR scores distinguished between doctors who had been ‘referred’ because of concerns and those about whom there were no concerns (Reference Goulet, Jacques and GagnonGoulet 2002).

Adoption and development in the UK

Case-based assessment was adapted from original work in Canada and the USA by the General Medical Council (GMC) in its performance assessment procedures. Currently in the UK, case-based discussion is used extensively by the GMC and the National Clinical Assessment Service (NCAS) in their assessments of performance, as well as forming a key component of the assessment framework for foundation and specialty training.

The use of case-based discussion in the foundation programme has been reported by Davies et al in a summary of the workplace-based assessments in postgraduate training of physicians in the UK (Reference Davies, Archer and SouthgateDavies 2009). Their data suggest good levels of reliability for case-based discussion using four, but preferably eight, cases. The authors also established that scores for case-based discussion increased between the first and second half of the year, indicating validity. Early findings from a pilot study by the Royal College of Physicians (Reference Booth, Johnson and WadeBooth 2009) supported the notion of case-based discussion as a valid and reliable instrument in the assessment of doctors’ performance. Further results are now emerging from the Royal College of Physicians following the full introduction of the curriculum and assessment reforms in 2007 (details available from N.B. on request).

The Royal College of Psychiatrists’ curricula for specialty training in psychiatry currently use case-based discussion. In addition, there are a number of variants on the theme used in encounters with simulated or standardised patients (including incognito standardised patients, so-called ‘mystery customers’) in clinical settings in many other specialties and in many different countries. Other variants on case-based discussion can be used away from the workplace in formal examination such as objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) and the Clinical Assessment of Skills and Competencies (CASC).

Context of contemporary postgraduate medical education

Assessment programmes

Before proceeding with further consideration of case-based discussion it is useful to place it within the context of contemporary thought on assessment in medical education. Postgraduate medical education is a growing field with a language, set of terms and, some would say, fashions of its own. It is important to note that contemporary best practice in assessment in medical education is moving in a direction that is significantly different from the traditional model. This issue is discussed in detail elsewhere, particularly in the seminal paper by Reference Van der VleutenVan der Vleuten (1996) and later papers by Reference Van der Vleuten and SchuwirthVan der Vleuten & Schuwirth (2005) and Reference Schuwirth and Van der VleutenSchuwirth & Van der Vleuten (2006a,Reference Schuwirth and Van der Vleutenb). It has also been discussed and developed in a broader context by Reference Holsgrove, Davies, Jackson, Jamieson and KhanHolsgrove & Davies (2007, Reference Holsgrove, Davies, Carter and Jackson2008).

However, put briefly, there are two main issues. First is the point raised in Van der Vleuten's earlier article (1996) that assessment is not a measurement issue intended, for example, to reduce clinical competence into its supposed component parts and express the levels of attainment in numerical terms. Instead, it should be seen as a matter of educational design aimed to assess clinical competence as a global construct. Second, assessments should have a variety of purposes (Reference Southgate and GrantSouthgate 2004; Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board 2010b). These purposes include feedback – not just feedback to the person being assessed, but also to teachers, assessors and other interested parties (Reference Holsgrove, Davies, Carter and JacksonHolsgrove 2008). This philosophy leads us to the concept of a utility model in which assessment programmes are designed, with context-dependent compromises where necessary, to suit a particular set of requirements and circumstances. This model recognises that assessment characteristics are weighted depending on the nature and purpose of the assessment (Reference Van der Vleuten and SchuwirthVan der Vleuten 2005). Reliability depends not on structuring or standardisation but on sampling. Key issues concerning validity are authenticity and integration of competencies; thus, alignment with the curriculum and its aims is essential. In sum, this model suggests that fundamentals of a successful assessment programme are adequate sampling across judges, instruments and contexts that can then ensure both validity and reliability.

The assessment programme designed to support the College curricula includes both formal (MRCPsych) examinations and workplace-based assessments. Case-based discussion is among the workplace-based assessments in that programme and, along with the observed assessment (assessment of clinical expertise – ACE – or mini-assessed clinical encounter – mini-ACE), case-based discussion assesses the very heart of daily clinical performance by a doctor.

Postgraduate medical education – what does this actually mean? What do trainers and trainees need to know?

It is worth considering once more the context in which case-based discussion has appeared. As with many assessments in contemporary medical education, it is important to remember that case-based discussion is attempting to serve both formative (‘How am I doing?’) and summative (‘Have I passed or failed?’) assessment purposes. It is therefore an instrument that can be used to provide assessments both for and of learning (Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board 2010a). The content and application of learning and the outcomes of assessment are defined in the curriculum and so the selection and use of learning and assessment instruments must always be undertaken with the curriculum in mind. This, although apparently obvious, is in sharp contrast to learning and assessment in the past. Consideration of the place of case-based discussion is therefore an exemplar of the need for trainers (and trainees) to be fully aware of the curriculum in setting learning plans with intended learning outcomes that match curriculum outcomes and are subject to continuing assessment that is carefully planned and not simply a spontaneous occurrence.

The importance of the curriculum

The curriculum is not simply an examination syllabus or a list of things that a trainee is supposed to learn. Equally, assessment is no longer solely a series of formal, high-stakes examinations, although the latter remain critical in the setting and monitoring of national and international standards. The Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB), for all its early shortcomings (and these we are left for history to debate), undoubtedly raised the quality of postgraduate medical curricula and assessment. This influence for change should be undiminished – and may be enhanced – by the merger of PMETB and the GMC in 2010. For the individual trainer and trainee (together or alone) the fundamental need is to understand what this instrument can do, how it fits with other assessments into an individual educational programme (remember, the educational cycle includes assessment) and, crucially, how and when to use it for best impact.

The use of case-based discussion – practical guidance

Planning – first stage

The fundamental nature of case-based discussion or assessment is that the doctor's own patients (cases) are used as the starting point for a conversation or discussion that looks into that doctor's applied knowledge, reasoning and decision-making. Case-based discussion is an assessment instrument that probes the doctor's clinical reasoning; it may be described as a structured interview designed to explore professional judgement exercised in clinical cases. Professional judgement may be considered as the ability to make holistic, balanced and justifiable decisions in situations of complexity and uncertainty. Case-based discussion can explore a full range of these issues, such as the ability to recognise dilemmas, see a range of options, weight these options, decide on a course of action, explain the course of action and assess its results. It draws on practical aspects of a doctor's routine clinical activity either in the form of documented observed practice (an ACE or mini-ACE would make suitable materials) or an examination of entries made in the case notes and subsequent discussion of the case. Based on such records of a patient recently seen by the trainee, and to whose care they have made a significant contribution, case-based discussion is conducted as a structured discussion.

A few days ahead of the scheduled case-based discussion, either the trainee gives the assessor two sets of suitable notes or they agree on the discussion stemming from an observed interview. The assessor reads them and selects one for the case-based discussion. The potential curriculum domains and specific competencies should be mapped at the outset. In their initial meetings trainers and trainees will find it invaluable to draw up a blueprint (either prepared themselves or from their postgraduate school) on which to plot their learning plan, including specific learning objectives and assessments. This will ensure full and proper curriculum coverage. Case selection should be kept simple but must enable good curriculum coverage. A grid may be constructed that plots cases, questions from the case-based discussion and curriculum objectives (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 Case-based discussion – example planning grid (the list of objectives is not exhaustive). After National Clinical Assessment Service 2010.

Planning – second stage

The next stage of planning is for the assessor to write out the questions that they intend to ask. This may initially appear over-prescriptive and somewhat obsessional. However, it is critical that the discussion retains its focus and avoids false trails, for example, into discussing the patient's problems or reviewing the notes themselves or turning the case-based discussion into a factual viva. Good practice is to prepare around three questions for each case, preferably covering different curriculum or performance objectives (e.g. as marked with a tick in Fig. 1). The use of three questions will facilitate coverage of more than one competency with the same case. Some thoughts and suggestions on construction of questions are offered in Box 1.

BOX 1 Question guidance

Integration of assessment and investigations

What relevant information did you have available? Why was this relevant? How did the available information or evidence help you? What other information could have been useful?

Consideration of clinical management options

What were your options? Which did you choose? Why did you choose this one? What are the advantages/disadvantages of your decision? How do you balance them?

Communication with patient

What are the implications of your decision? For whom? How might they feel about your choice? How does this influence your decision?

Evidence to support management plan

How do you justify your decision? What evidence do you have to support your choice? Can you give an example? Are you aware of any model, framework or guidance that assists you? Some might argue with your decision – how might you engage them?

Legal/ethical framework

What legal or ethical framework did you refer to? How did you apply it? How did you establish the patient's (service user's) point of view? What are their rights? How did you respond?

Team working

Which colleagues did you involve in this case? Why? How did you ensure that you had effective communication with them? Who could you have involved? What might they have offered? What is your role?

‘Duties of a doctor’

What are your duties and responsibilities? How did they apply to this case? How did you observe them?

The discussion

It is important to ensure that doctors being assessed have time to review the records and refresh their memory before the case-based discussion starts and that the records are present throughout the discussion for reference. Questioning should commence with a reminder of the case and, ideally, the competency and/or curriculum domain that is being covered and should begin in an open fashion. The subsequent discussion is then anchored on this particular case and is clear in its aim of assessment against a curriculum domain or intended learning outcome. This is facilitated by the assessor, who might use prompts such as those in Box 1.

It can clearly be seen that the major contribution that case-based discussion makes to the overall assessment programme is that it allows the assessor to explore clinical reasoning and professional judgement. However, it is important again to distinguish case-based discussion from a traditional viva because a case-based discussion must not be a viva-type interaction exploring the trainee's knowledge of the clinical problem. It must focus on what is in the notes and the trainee's thinking in relation to the diagnosis and management of the case.

Feedback

It is axiomatic that a well-conducted assessment must be accompanied by timely and effective feedback, as has previously been discussed in this journal (Reference Brown and CookeBrown 2009).

Finally

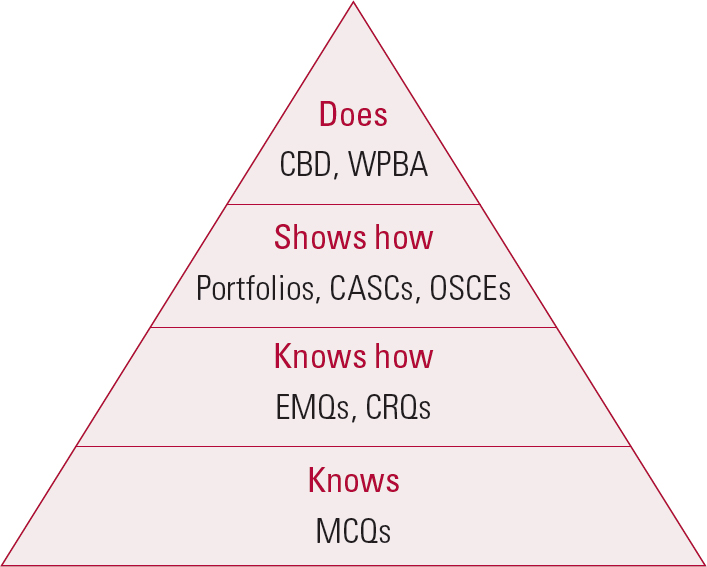

Case-based discussion needs preparation by both trainer and trainee. It is important to select cases carefully and to look at the case before the meeting. Assessors must not attempt to make it up as they go along. The discussion can be quite challenging and a trainer may find an early difficulty in suppressing the urge to say ‘What if … ?’ (the discussion is an assessment of what the doctor did with a particular case, not what they might have done). So, doctors can be asked what they did and why, what evidence they have for that action and even ‘What is your next step?’ However, assessors should not go down the line of hypothetical exploration. Colleagues in all specialties have discovered that case-based discussion needs considerable practice to develop new skills and the discipline not to slip into tutorial or viva modes of questioning. Case-based discussion tests what the doctor actually did rather than what they think they might do (which is what a viva or OSCE might test). Thus, case-based discussion assesses at a higher level on Miller's pyramid (Reference MillerMiller 1990) than most other assessments because it tests what the doctor or trainee did as opposed to what they show or know they can do (Fig. 2).

FIG 2 The hierarchy of skills and related assessment instruments. CASC, Clinical Assessment of Skills and Competencies; CBD, case-based discussion; CRQ, constructed response question; EMQ, extended matching question; OSCE, objective structured clinical examination; WPBA, workplace-based assessment. After Reference MillerMiller 1990.

The discussion and feedback should take around 25–30 minutes, of which about 10 minutes should be reserved for feedback.

Back to the educational (including assessment) programme

Case-based discussion can, and indeed should, be used in conjunction with other assessment instruments, in particular those assessing observed clinical practice (ACE or mini-ACE), written clinical material such as out-patient letters (Reference Crossley, Howe and NewbleCrossley 2001) and the case presentation assessment used in the College curriculum (Reference SearleSearle 2008). Moreover, as well as being a useful assessment instrument, case-based discussion can be an effective learning method using, for example, multimedia adaptation and presentation of cases (Reference Bridgemohan, Levy and VeluzBridgemohan 2005) or interdisciplinary discussion with a personal development plan (PDP) peer group.

Case-based discussion and revalidation

Revalidation is a set of procedures operated by the GMC to secure the evaluation of a medical practitioner's fitness to practise as a condition of continuing to hold a licence to practise (adapted from the Medical Act 1983 (Amendment) Order 2002). A strengthened or enhanced appraisal system, consistently operated and properly quality-assured lies at the core of revalidation procedures. Appraisal must retain a formative element for all doctors, but it will also take account of ‘assessment’. The College is currently proposing that case-based discussion be one of the methods of performance assessment (Reference Mynors-WallisMynors-Wallis 2010). Pilots have been undertaken and the results are awaited but clearly questions remain regarding the full range of considerations. There is obvious validity (as there is in the training situation) because the assessment focuses on professional judgement, which is the bread and butter of the established psychiatrist. However, there are clear concerns regarding the choice, training and continuing accreditation of assessors, which in turn poses questions about reliability. There is a need to carefully consider numbers of cases and sampling across the individual's full scope of practice. These provide a serious challenge to the idea that reasonable and potentially defensible evidence about performance will flow into an appraisal system and thus towards high-stakes decisions on fitness for purpose as a psychiatrist.

Summary

Case-based discussion has developed from its first use in Canada and the USA to become an important part of the assessment of clinical performance. It is an assessment of reasoning, exploring why a psychiatrist took a particular course of action at a particular time. It is authentic, feasible and useful. Its reliability has not yet been formally tested but the evidence suggests that reliability is enhanced by using as many cases and properly trained assessors as possible. Utility is then improved further by the pre-planning of questions and acceptable responses by assessors who fully understand the nature of both the doctor's practice and the relevant curriculum. This presents a clear challenge for those with responsibility for postgraduate medical education and medical management to provide the right high-quality training as a priority, including continuing training for assessors so that these conditions may be met.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Case-based discussion is:

-

a a viva testing the doctor's knowledge

-

b best conducted spontaneously

-

c a method for exploring clinical reasoning

-

d always a pass/fail assessment.

-

-

2 Case-based discussion:

-

a originates from GMC performance procedures

-

b originates from Canada and the USA

-

c is another name for an OSCE

-

d tests at the base of Miller's pyramid.

-

-

3 Questions used in case-based discussion:

-

a should always relate to the case

-

b should be closed in nature

-

c should always allow an element of ‘what if’

-

d should be used to clarify facts.

-

-

4 Case-based discussion:

-

a has proven reliability

-

b is feasible

-

c lacks validity

-

d has no place as a formative assessment.

-

-

5 Case-based discussion:

-

a has taken the place of the CASC

-

b can be a substitute for national examinations

-

c can be a useful learning tool

-

d can provide feedback on teaching.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | c | 2 | b | 3 | a | 4 | b | 5 | c |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.