Plato and Aristotle observed that democracy is difficult to establish and retain in divided societies with salient societal cleavages (Merkel and Weiffen Reference Merkel and Weiffen2012: 388). In modern times, to establish democracy successfully in a divided society has been described as ‘next to impossible’ by John Stuart Mill (Reference Mill1869: 310) and as ‘significantly less frequent’ by Robert Dahl (Reference Dahl1989: 255). However, in his path-breaking 1969 article entitled ‘Consociational Democracy’, Arend Lijphart showed that democracy can in fact survive in divided societies (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1969). Societal heterogeneity per se does not destabilize democracy as groups have to be organized along their divisions. It is only when heterogeneous groups are politicized, mobilized and organized that heterogeneity is transformed into societal cleavages (Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Bormann, Rüegger, Cederman, Hunziker and Girardin2015).

Consociational democracy, which Lijphart later termed power sharing (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1985), has turned into ‘one of the strongest, widely discussed, and influential research programmes in the field of comparative politics’ (Taylor Reference Taylor2009: 1).Footnote 1 At first, the term ‘power sharing’ was used empirically to account for democratic stability in Austria, Belgium, the Netherlands and Switzerland (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977). Later it was prescribed normatively as a solution for all deeply divided societies (Andeweg Reference Andeweg and Wright2015). Lijphart's work represented a paradigm shift by demonstrating the compatibility between democracy and societal cleavages contrary to the claims that justified authoritarian rule as the only way to ensure stability in divided societies (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2006: 119).Footnote 2 Over time, power sharing has become a ‘dominant conflict-solving approach’ (Binningsbø Reference Binningsbø2013: 89) by going beyond its strict focus on consociational cases. Both the consociational and the broader power-sharing strands of literature, however, have been tightly entangled, particularly in cross-national research (Bochsler and Juon Reference Bochsler and Juon2021; Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2015; Kelly Reference Kelly2019; Norris Reference Norris2008; Strøm et al. Reference Strøm, Gates, Graham and Strand2017).Footnote 3

Power sharing has been heavily criticized on normative, theoretical and empirical grounds (Barry Reference Barry1975; Bogaards Reference Bogaards2000; Horowitz Reference Horowitz2014; Lustick Reference Lustick1997; Rothchild and Roeder Reference Rothchild, Roeder, Roeder and Rothchild2005; Spears Reference Spears2002; van Schendelen Reference van Schendelen1985). In response, advocates of power sharing further developed the theory to address some of its theoretical weaknesses (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1981, Reference Lijphart2000; McGarry and O'Leary Reference McGarry and O'Leary2006a, Reference McGarry and O'Leary2006b; Noel Reference Noel2005). Advocates argue that power sharing is the most viable solution for peace and democracy in divided societies (Bochsler and Juon Reference Bochsler and Juon2021; Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Wucherpfennig2017; Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2020; Keil and McCulloch Reference Keil and McCulloch2021; McCulloch and McGarry Reference McCulloch and McGarry2017; McEvoy and O'Leary Reference McEvoy and O'Leary2013).

The literature lacks a study that synthesizes its findings. Previous attempts at synthesizing the literature, while valuable, are either traditional literature reviews (Andeweg Reference Andeweg2000) or based on a small group of studies (Binningsbø Reference Binningsbø2013). The most ambitious attempt to map the literature (Bogaards et al. Reference Bogaards, Helms and Lijphart2019) groups 346 articles identified under specific topics over time without synthesizing the findings of the literature. The puzzling record of power sharing particularly calls for such analysis. According to John McGarry (Reference McGarry2020: 100), power sharing ‘has enjoyed success in some places but not in others, in some places at particular times but not at other times, and with respect to some issues but not all … inconsistent with the views of overly-enthusiastic consociationalists and of their critics, many of whom appear to believe that consociations have nothing to offer’. This review article bridges this gap by synthesizing the findings of the power-sharing literature. For this purpose, we introduce an original dataset, the Power Sharing Articles Dataset (PSAD), which extracts data from 373 academic articles published between 1969 and 2018.Footnote 4

We next introduce the dataset. The subsequent section maps the theoretical and empirical foundations of the power-sharing literature. After that, we synthesize the positive and negative effects of power sharing as reported by the articles analysed here. The next section outlines the factors favourable to the success of power sharing. A final section concludes by developing a research agenda for future research.

Introducing the Power Sharing Articles Dataset

In building the PSAD, this review article uses Hilary Arksey and Lisa O'Malley's (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005) widely cited scoping review methodology (Cacchione Reference Cacchione2016: 116). Our review is guided by this question: what do we know about power sharing from the academic literature in English published between 1969 and 2018? The research question limits our review both temporally and linguistically. The year 1969 is chosen as the starting year because it corresponds to Lijphart's (Reference Lijphart1969) article, considered the ‘classic statement of consociational theory’ (Lijphart Reference Lijphart2008: 3).Footnote 5 We decided to focus on academic articles and exclude books for practical considerations.Footnote 6 There is a trade-off since leaving out some classic texts on power sharing (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977; McGarry and O'Leary Reference McGarry and O'Leary1995) could potentially bias the findings of this review.

Relevant academic articles were identified by searching for consociationalism (and its variants, consociation and consociational) and power sharing (and its variants power-sharing and powersharing) in articles' titles, abstracts and keywords. To ensure maximum coverage of articles, an identical search was done in three major social science databases: Scopus, the International Bibliography of the Social Sciences and Political Science Complete. The search returned 1,133, 1,076 and 962 articles, respectively, giving a total of 3,171 articles. Online Appendix 1 includes the full search terms used.

We shortlisted articles based on five exclusion criteria. First, we excluded 1,439 duplicate articles. Second, we excluded articles with incomplete bibliographic information and book reviews. Third, we excluded articles that are off topic, such as those on authoritarian power sharing or those articles that do not meet our definition of power sharing. We follow O'Leary (Reference O'Leary, McEvoy and O'Leary2013: 3) in defining power sharing as ‘any set of arrangements that prevents one agent, or organized collective agency, from being the winner who holds all critical power, whether temporarily or permanently’. This definition is useful because it goes beyond defining power sharing in terms of its institutional dimensions: grand coalition, proportional representation, cultural autonomy and minority veto (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977). This resonates with the recent literature on power sharing that went beyond its strict consociational focus (Binningsbø Reference Binningsbø2013). Speaking about power sharing in Africa, Nic Cheeseman argues that,

Where political settlements are highly inclusive and permanent, they conform to Lijphart's influential model of consociational democracy in which ethnic diversity is managed by building measures that protect the interests of each community into the foundations of the political system. However, because power-sharing deals in Africa are usually forged amidst insurgency and political crisis, they have typically focused on a more modest agenda: securing a ceasefire, forging agreement on distribution of senior political positions, and scheduling a timetable for fresh elections. (Cheeseman Reference Cheeseman2011: 339–340)

This definition also grounds our understanding of power sharing as an arrangement between social groups within a given society, as originally studied by Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1969). This warrants our fourth exclusion criterion to exclude articles that are transnational, such as articles that take the European Union as the unit of analysis.Footnote 7 Fifth, given our focus on the empirical power-sharing literature, we excluded articles that are theoretical in nature and lack an empirically oriented research question. Applying these five exclusion criteria, the PSAD thus includes a final list of 373 articles.

A team of four researchers and a research team leader carried out the data extraction and analysis. At the project's inception, the research team leader trained the research team as part of a larger team on both the substantive power-sharing literature and on the scoping review methodology. The training included practical exercises on data extraction where extensive feedback was given by the team leader. Data from each article was extracted manually. Included articles in this review were read in full by a designated researcher. Researchers then extracted data from the articles by filling out an online form designed specifically for the data extraction. Two levels of quality control were implemented. First, members of the research team highlighted in a special section of the form when they were unsure about a particular question during data extraction. This was then reviewed by another team member. If the issue remained unresolved, the research team leader took the final decision. Second, the team leader looked at random samples of the extracted data to ensure coding reliability and consistency. While an inter-annotator record was not kept, we estimate the reliability and consistency of the data collection at around 90–95%. For example, 391 articles were initially shortlisted after applying the exclusion criteria. Of these, 18 articles were later excluded during the data-extraction phase for having been found to meet some exclusion criterion. If we generalize the margin of error from this example to the data-extraction phase, the coding reliability and consistency lie at 95.39%.

For each of the 373 articles, we collected data on 23 variables, including bibliographic information (e.g. article title, author, date and journal), theory and concepts (e.g. research question, terms used to describe power sharing, the definition of power sharing used), research design, measurement and contextual information (e.g. names of countries or cases studied, research strategy, time period and method of analysis, how power sharing is measured and power-sharing institutions studied) and empirical findings (e.g. positive or negative effects of power sharing and favourable factors). The next section maps the theoretical and empirical boundaries of the literature.

The theoretical and empirical dimensions of power sharing

The empirical power-sharing literature has been growing steadily over time, with an exponential increase in the last decade. In the first three decades – between 1969 and 1998 – only 42 (out of 373 articles) were published, which more than doubled in the following decade with 99 articles. The fifth decade (2009–18) witnessed an unprecedented increase, with the publication of 232 articles. Certainly, there has been a parallel increase in the publication of social science articles overall, but the exponential increase in articles on power sharing is much higher, as illustrated in Figure 1. The number of articles published in social sciences in the first decade (1969–78) stood at 51,982. This number increased to 154,944 for articles published in the third decade between 1989 and 1998 before reaching an all-time high with 437,992 articles published in the fifth decade (2009–18). In other words, there is a more than fivefold increase in the publication of power-sharing articles between the first and fifth decades compared to only a little less than a threefold increase in social science articles published during that period.

Figure 1. Trends of Publication of Power-Sharing and Social Science Articles (1969–2018)

Source: The authors.

Notes: Power-sharing articles are compiled via the PSAD. Social science articles are retrieved from Scopus, Elsevier's research database, and include articles published in academic journals and written in English.

Scholars have been interested in studying the origins of power sharing (107 out of 373 articles) along with its effects on stability and peace, moderation of societal/ethnic cleavages and democracy (188 articles). Table A2 in the Online Appendix offers an overview of the top five independent and dependent variables in the power-sharing literature. In addition, there have been calls to distinguish between consociationalism and power sharing (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2000). However, the literature has been converging on the interchangeable use of ‘consociationalism’ and ‘power sharing’ in around half of the studies examined, with the other half evenly distributed between the exclusive use of one of those terms. Table A3 in the Online Appendix includes the exact distribution of terms used to describe power sharing.

To date, Lijphart's definitions are the most cited in the literature on power sharing; 158 out of 373 articles adopt his definitions to describe power sharing. The most common definition of power sharing features the four institutional dimensions: namely, grand coalition, minority veto, proportional representation and segmental autonomy (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977: 25). The second common definition focuses on the role of elites in power sharing, viewed as ‘government by elite cartel’ (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1969: 216). Despite the former ‘institutional turn’ in the power-sharing literature by focusing more on the role of institutions, the use of this latter definition reflects the belief of scholars that the agency of political elites is important. Table A4 in the Online Appendix presents the frequency of definitions of power sharing in the literature.

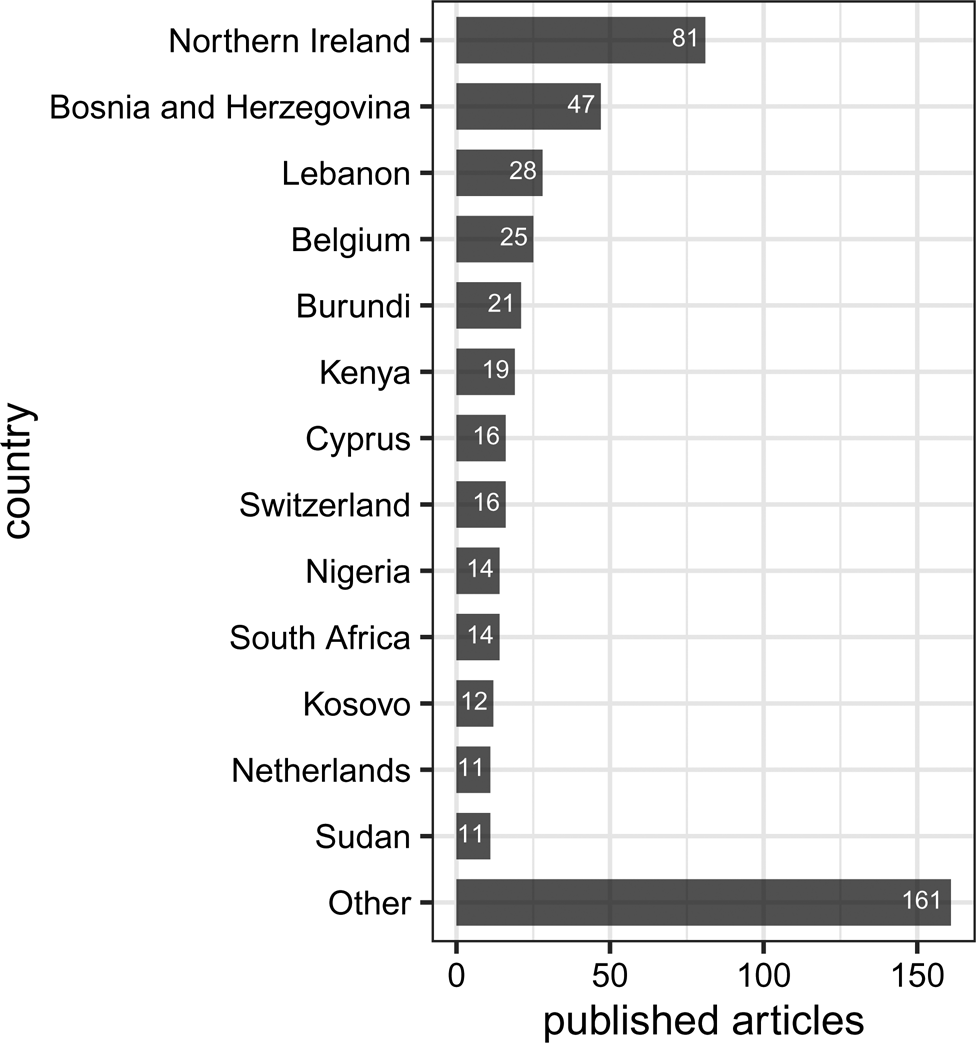

The power-sharing literature is certainly more diverse now through the study of cases across the globe (Bogaards et al. Reference Bogaards, Helms and Lijphart2019). Nevertheless, it is still dominated by studies of cases in Europe and Central Asia (204 articles). Figure 2 presents the most studied cases in the literature. Within Europe, Northern Ireland comes first, followed by Bosnia and Herzegovina (81 and 47 articles, respectively). There is variation in the study of the classic consociational cases – namely Belgium, Switzerland and the Netherlands – which are covered in 25, 16 and 11 articles, respectively. This mapping of the cases studied in the literature is in and of itself a contribution, given the absence of very basic agreement on the countries studied in the power-sharing literature (Dixon Reference Dixon, Jakala, Kuzu and Qvortrup2018). In the words of Helga Binningsbø (Reference Binningsbø2013: 97), ‘it is not quite clear which countries and which time periods are categorized as power sharing cases’.

Figure 2. Most Studied Countries in the Power-Sharing Literature

Source: The authors.

Notes: Articles that study more than one country have been double-counted. Some countries below are included in comparative articles despite not being themselves cases of power sharing. Numbers between brackets below refer to the number of articles in which a particular case is studied. Other articles studied: Afghanistan (1), Angola (3), Armenia (1), Austria (6), Azerbaijan (1), Bangladesh (1), Burkina Faso (1), Canada (7), Catalonia (1), Colombia (1), Comoros (1), Côte d'Ivoire (4), Czechoslovakia (2), Democratic Republic of Congo (8), Estonia (1) Ethiopia (4), European Union (2), Fiji (5), Finland (1), India (8), Indonesia (3), Iraq (6), Ireland (2), Israel (9), Italy (4), Kazakhstan (1), Kyrgyzstan (1), Liberia (3), Macedonia (7), Malaysia (9), Mexico (1), Moldova (1), Mozambique (1), Nepal (1), Pakistan (3), Palestine (2), Philippines (3), Russia (4), Rwanda (11), Serbia and Montenegro (2), Sierra Leone (1), Slovakia (1), Somalia (1), South Sudan (3), South Tyrol (4), Spain (2), Sri Lanka (3), Suriname (1), Syria (2), Tajikistan (1), Tanzania (1), Uganda (2), Ukraine (2), United Kingdom (4), United States of America (1) and Zimbabwe (5).

In terms of research strategies, the literature is dominated by single case studies and small-N comparisons. They are used respectively in 245 and 91 out of 373 studies included in this review. The remaining studies include an increasing share of large-N (27 articles) and finally medium-N cases (10 articles). The methods used in the power-sharing literature parallel the research strategies, with 318 articles using qualitative methods and 50 articles adopting quantitative methods (Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Hug, Schädel and Wucherpfennig2015; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Miller and Strøm2017; Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2003). The covered articles also include a few studies using game theory and formal modelling (Tangerås and Lagerlöf Reference Tangerås and Lagerlöf2009; Tridimas Reference Tridimas2011; Wantchekon Reference Wantchekon2000) and a notable study using computer simulations (Lustick et al. Reference Lustick, Miodownik and Eidelson2004). For more information on research strategies, methods, units of analysis and time periods, see Online Appendix 6.

When it comes to operationalizing power sharing, the PSAD documents only 99 articles providing an empirical measure of power sharing. In fact, Lijphart (Reference Lijphart and Reynolds2002) admitted 20 years ago that operationalizing and measuring power sharing is inherently a daunting task due to the different forms it can take. Our review confirms Lijphart's point. Scholars have not so far been able to operationalize power sharing exactly along the four institutional dimensions: grand coalition, proportional representation, minority veto and segmental autonomy. The most ambitious attempts include operationalizations of the three dimensions (Cammett and Malesky Reference Cammett and Malesky2012) with other operationalizations along two dimensions such as grand coalition and regional autonomy (Cederman et al. Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Wucherpfennig2017, Reference Cederman, Gleditsch and Wucherpfennig2018) or grand coalitions and minority veto (Gates et al. Reference Gates, Graham, Lupu, Strand and Strøm2016; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Miller and Strøm2017; Strøm et al. Reference Strøm, Gates, Graham and Strand2017).Footnote 8

Grand coalition and proportionality are the most studied institutions of power sharing (217 and 216 articles, respectively). Minority veto and cultural autonomy are studied each in 136 and 131 articles, respectively. However, the fact that only one-third of the articles studies cultural autonomy is surprising since it is one of the primary features of power sharing alongside grand coalition (Lijphart Reference Lijphart2008: 38–39). Cultural autonomy allows ethnic groups self-rule over issues of ‘exclusive concern’ (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977: 41). It takes several forms, including federal arrangements and certain rights for religious and linguistic groups as in Belgium or Macedonia (McCulloch Reference McCulloch2014). Our findings thus support recent calls that more emphasis should be put on the study of cultural autonomy (McGarry Reference McGarry, McCulloch and McGarry2017).

To overcome the difficulty of operationalizing the classic institutional features of power sharing, studies show an increasing diversity of approaches. One prominent example is the distinction by Caroline Hartzell and Matthew Hoddie (Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2003) between political, military, territorial and economic power sharing. It has been adopted widely in cross-national analysis (Jarstad and Nilsson Reference Jarstad and Nilsson2018; Joshi and Mason Reference Joshi and Mason2011; Mattes and Savun Reference Mattes and Savun2009). Other operationalizations of power sharing include the proportional ethnic distribution of party members (Shastri Reference Shastri2005), recognition of minority language (Liu Reference Liu2011), the representativeness of government or party coalitions (Conley and Dahan Reference Conley and Dahan2013; Strasheim and Fjelde Reference Strasheim and Fjelde2014), control over fiscal or political decision-making (Brancati and Snyder Reference Brancati and Snyder2011) and ethno-federalism (Charron Reference Charron2009). Table A9 in the Online Appendix presents the detailed operationalizations of 40 quantitative studies. The next section examines the positive and negative effects of power sharing.

The positive and negative effects of power sharing

According to our analysis, 229 of the 373 articles report positive effects of power sharing while only 45 report negative effects. Nineteen report mixed positive and negative effects and 78 report no effects. As outlined in Table 1, the articles reviewed found power sharing to have a positive effect on stability and peace, democracy or democratization, pacification of cleavages and moderation of social groups.Footnote 9 While this generally indicates that power sharing works, it raises an important question: why does it work in some cases but not others?

Table 1. The Positive and Negative Effects of Power Sharing

Source: The authors.

Note: The absolute number exceeds the total number of articles (N = 373) because some articles report more than one positive or negative effect. Seventy-eight articles report no effects and thus are not included in this table. Those articles mostly use power sharing as a dependent variable, including by examining its origins, and are thus not concerned with its effects.

One argument could be that the positive effects are a function of liberal, not corporate, power-sharing systems. According to Allison McCulloch (Reference McCulloch2014: 503), ‘a corporate consociation entails the constitutional entrenchment of group representation’, whereas ‘liberal consociationalism avoids constitutionally entrenching group representation by leaving the question of who shares power in the hands of voters’. Liberal power sharing, also referred to as self-determination as compared to corporate pre-determination, allows for flexibility and adaptability to changes in the salience of ethnicity or to fluctuating strengths of ethnic groups (Lijphart Reference Lijphart and Kymlicka1995). In contrast, corporate power sharing can ‘entrench and institutionalize pre-existing, and often conflict-hardened, ethnic identities, thus decreasing the incentives for elites to moderate’ (Wolff Reference Wolff2011: 1783). Corporate cases include Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burundi, Lebanon and South Tyrol; liberal cases are Iraq, Malaysia and Afghanistan; and hybrid cases encompass Northern Ireland, Macedonia, Kenya and Switzerland (McCulloch Reference McCulloch2014).

Belgium is a classic corporate case given its fixed legislative representation for Flemish and Walloons (60% and 40% respectively) and their equal representation in the cabinet. In contrast, Iraq's liberal power-sharing system has no such fixed representational quotas either in the legislature or in the government. However, there is an unwritten, informal agreement in Iraq according to which the presidency is awarded to a Kurd, the premiership to a Shiite Muslim and the parliament speakership to a Sunni Muslim. In Northern Ireland, a hybrid power-sharing case, Protestant Unionists and Catholic Nationalists do not have fixed shares in government but have mutual veto powers.

In Table 2, we disaggregate the positive and negative effects of power sharing by the corporate, liberal and hybrid systems. The analysis shows that the claimed advantage of liberal power sharing in the literature is to some extent overstated. In other words, power sharing has both positive and negative effects in countries belonging to the various systems.Footnote 10 The articles reviewed demonstrate that the corporate power-sharing systems in Burundi, Belgium and South Tyrol are shown to have predominantly positive effects on stability and peace, moderation of ethnic groups and democratization. This is the case particularly during the earlier power-sharing stages in Burundi (Vandeginste Reference Vandeginste2011) and throughout in Belgium and South Tyrol (Wolff Reference Wolff2004). The record, however, is mixed in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Lebanon. On the one hand, corporate power sharing was reported to have led to peace and stability in both countries (Rice Reference Rice2017; Rosiny Reference Rosiny2015). On the other hand, corporate power sharing was found to lead to political stalemate, exacerbation of ethnic divisions and clientelism along with a low quality of democracy (Hulsey Reference Hulsey2010; Salamey and Tabar Reference Salamey and Tabar2012).

Table 2. The Effects of Corporate and Liberal Power-Sharing Systems

Source: The authors.

Note: Some articles report more than one positive or negative effect and thus are double-counted.

The same is also said about liberal power-sharing systems. The articles reviewed suggest that in Malaysia, for example, power sharing has contributed to stability and peace and moderation of social groups (Jarrett Reference Jarrett2016) while leading at the same time to instability and institutionalization of ethnic cleavages (Segawa Reference Segawa2015). The picture is not very different under hybrid power sharing. In the articles studying Switzerland, Macedonia and Northern Ireland, power sharing was found to have positive effects on stability and peace, moderation of ethnic groups and democracy (Bochsler and Bousbah Reference Bochsler and Bousbah2015; Lyon Reference Lyon2012; McGarry and O'Leary Reference McGarry and O'Leary2016). In Kenya, however, according to the analysed articles, power sharing has a mixed record: stability and peace at the expense of democracy (Cheeseman and Tendi Reference Cheeseman and Tendi2010; Koko Reference Koko2013). This analysis suggests that there might be factors beyond the institutional set-up, be it corporate, liberal or hybrid, that drive the positive and negative effects of power sharing.

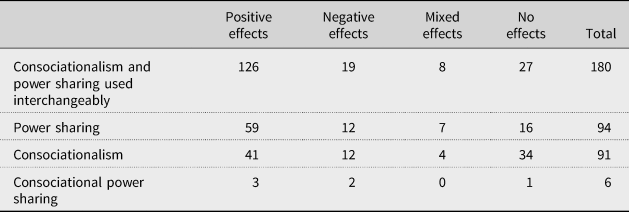

It might be argued that the positive and negative effects of power sharing are rooted in the distinction between power sharing narrowly defined as consociationalism and the wider post-conflict, transitional notion of power sharing (Binningsbø Reference Binningsbø2013; Cheeseman Reference Cheeseman2011). Power sharing, this argument goes, takes many forms and consociationalism is only one of them (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2000). The PSAD allows for such disaggregation by analysing the positive and negative effects based on the terms used in the article: power sharing, consociationalism, the interchangeable use of both terms, and consociational power sharing. As illustrated in Table 3, the terms used to describe power sharing do not influence the generally positive effects of power sharing prevalent in the articles reviewed: 41 articles that exclusively use ‘consociationalism’ report positive effects, compared to 12 articles reporting negative effects and an even lower number (4 articles) reporting mixed effects. A similar pattern is observed when looking at articles that employ power sharing or those where both terms are used interchangeably along with the small number of articles using consociational power sharing.

Table 3. The Effects of Consociationalism and Power Sharing

Source: The authors.

Note: Some articles report more than one positive or negative effect and thus are double-counted.

This finding challenges the argument rooting Iraq's instability, for instance, in its liberal ‘consociational light’ system (Bogaards Reference Bogaards2021b). At the same time, the analysed articles suggest that institutionalizing ethnicity through corporate consociational systems as in Bosnia and Herzegovina is not without its own problems (Bahtić-Kunrath Reference Bahtić-Kunrath2011). In sum, the articles covered in this review highlight that transitional power sharing contributes to stopping violence, but cannot rule out its onset or recurrence – as the case of Colombia or generally in Africa shows (Daly Reference Daly2014; Spears Reference Spears2013). It is also true that post-conflict, transitional power sharing can in some cases drive corruption: ‘since elites within the power sharing arrangement cannot be certain that they will be represented in the post-transitional political order, they have strong incentives to capture as many state resources as possible’ (Haass and Ottmann Reference Haass and Ottmann2017: 69). In sum, the evidence gathered from the reviewed articles suggests that post-conflict, transitional power sharing ensures peace in the short term but has more negative effects in the long run.

This should not be interpreted as the triumph of consociationalism. Consociational institutions did not save Lebanon from its deadly civil war between 1975 and 1990 (Dekmejian Reference Dekmejian1978; Hudson Reference Hudson1997). According to Imad Salamey and Paul Tabar (Reference Salamey and Tabar2012: 510), consociationalism can even lead to ‘greater national fragmentation, and, at best, establish authoritarian enclaves whose populist leaders take the state and sectarian constituencies hostage for their opportunistic interests’. In short, consociational arrangements are also not a panacea.

We now move to examine the geographical dimensions of power sharing. Table 4 illustrates the varying positive and negative effects of power sharing across world regions. In North America, the articles reviewed demonstrate that power sharing has exclusively positive effects in Canada (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2004).Footnote 11 In Europe and Central Asia, power sharing has the second-highest frequency of positive effects in 113 (out of 130) articles, negative effects in 13 articles, mixed effects in 4 articles and no effects in 32 articles. In Africa, argues Andreas Mehler (Reference Mehler2009: 470), power sharing ‘offer[s] no miraculous solutions to complex crisis situations’. Nevertheless, the analysed articles demonstrate that power sharing has a positive effect in 48 out of 70 articles, mixed effects in 9 articles, negative effects in 6 articles and no effects in 7 articles.

Table 4. The Effects of Power Sharing by World Region

Source: The authors.

Note: Some articles report more than one positive or negative effect and thus are double-counted.

The remaining world regions have a mixed record combining nearly equal positive and negative effects. This, as a result, sheds doubt on any regional dimension of power sharing. That power sharing can succeed across the globe, regardless of country or world region, challenges essentialist connotations of power sharing that Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1977) himself pushed against. While a political culture of accommodation between social groups is important for power sharing (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1968a; Steiner Reference Steiner and Taylor2009), such culture is not restricted to a particular geographic region. The next section directs attention to the effect of structural factors on the success of power sharing.

Favourable factors and the success of power sharing

The development of the power-sharing theory has resulted in refining the favourable, structural factors over time. Between 1968 and 1985, Lijphart used 14 different favourable factors with only 4 in common (Bogaards Reference Bogaards1998: 476–477). But after the mid-1980s, Lijphart (Reference Lijphart2008: 5) settled on nine favourable factors, with two considered as the most important: the lack of an ethnic or religious majority and limited socioeconomic inequalities among the different groups. The other seven factors include the number of societal groups, same size of groups, small population size, external threats, overarching loyalties (such as nationalism), geographical concentration of groups, and traditions of compromise and accommodation.

There is, nevertheless, a lack of theoretical clarity on the empirical relevance of the favourable factors. Lijphart (Reference Lijphart2008: 5) argued that the ‘nine conditions should not be regarded as either necessary or sufficient conditions: an attempt at consociationalism can fail even if all the background conditions are positive, and it is not impossible for it to succeed even if all of these conditions are negative’. As a result, van Schendelen (Reference van Schendelen1985: 160) criticized Lijphart's position, arguing that the favourable factors ‘may be present and absent, necessary and unnecessary, in short conditions or not conditions at all’. In the following, we shed some light on the relationship between the favourable factors and power sharing.

Table 5 presents the frequency of favourable factors compared to their contribution to the success of power sharing. Three primary observations are in order. First, the two most important factors in Lijphart's view – namely no majority group and socioeconomic equality – are not among the top factors enabling the success of power sharing, as appears from the analysed articles. Both are reported respectively by 28 and 14 of the articles covered in this review. Majority groups, Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1969: 217) theorized, tend to dominate rather than cooperate with minorities, while low socioeconomic inequality lowers the grievances of poorer groups and reduces the magnitude of risks perceived by the well-off ones (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1985: 124–125). While the data at hand do not entirely negate the relevance of both conditions, it seems plausible to question treating them as superior to the other factors.

Table 5. Favourable Factors and the Success of Power Sharing

Source: The authors.

Note: The absolute number exceeds the total number of articles (N = 373) because some articles report more than one favourable factor. Thirteen articles do not report any favourable factors.

Second, it is significant that 79 articles point towards the geographical concentration of groups as the favourable factor associated most with the success of power sharing. Its significance lies in supporting Lijphart's notion that ‘good fences make good neighbors’ (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977: 140). Such territorial isolation, the argument goes, limits tensions and hostility arising from mutual contact between different groups (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977: 88). This type of geographical concentration has enabled to a large extent the maintenance of stability and peace between the Flemish community (Flanders) and the French-speaking community (Wallonia) in Belgium and between Muslim-Croats and Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Schneckener Reference Schneckener2002: 212).

This challenges the ‘centripetal’ school, which advocates for ‘vote pooling’ (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1993).Footnote 12 Benjamin Reilly (Reference Reilly2002: 157) summarizes this logic, saying that the aim is ‘not to encourage the formation of ethnic parties, thereby replicating existing ethnic divisions in the legislature, but rather to utilize electoral systems that encourage cooperation and accommodation among rival groups, and therefore work to reduce the salience of ethnicity’. This review clearly shows that the success of power sharing, at least in part, depends on isolation, not integration.

Third, the favourable factors based on the covered articles in this review seem to have a combined effect. In other words, rarely does a study ascribe the success of power sharing to one factor. There are exceptions such as attributing the success of power sharing in Malaysia to the traditions of elite accommodation (Mohd Sani Reference Mohd Sani2009; Morris Reference Morris1999). However, this is not the norm. The survival of the Lebanese power-sharing system, John Nagle (Reference Nagle2018) contends, is a function of the reinforcing effects of the following factors: the lack of a majority group, the equal size of groups, a strong sense of national identity and the role of external dangers or threats. In Switzerland a number of factors are reported to have shaped the success of power sharing: a medium number of linguistic groups along with a degree of geographical concentration (Bochsler and Bousbah Reference Bochsler and Bousbah2015; Mueller and Rohner Reference Mueller and Rohner2018). In Burundi the interaction between a small population, an evolving tradition of accommodation, external dangers or threats and the mediating role of South Africa are all claimed to have had a positive effect on power sharing (Vandeginste Reference Vandeginste2009).

To summarize, while many studies covered in this review evoke the importance of favourable factors, only 20 out of 373 articles exclusively focus on how favourable factors shape power sharing. Without exception, they are all either single case studies such as on Pakistan (Mushtaq et al. Reference Mushtaq, Muhammad and Alqama2011) and Rwanda (Njoku Reference Njoku2005) or small-N comparisons (Lemarchand Reference Lemarchand2007; Schneckener Reference Schneckener2002). Unpacking the structural roots of power sharing would increase the theory's predictive power (Bogaards Reference Bogaards1998).

Conclusion: a research agenda

This review article has attempted to analyse the published articles on power sharing over 50 years. The power-sharing literature has been growing since its inception in 1969. The literature witnessed a boom of publications in the last two decades at a rate not matched at the level of the social sciences. Power sharing, therefore, ‘is more alive than ever’ (Bogaards et al. Reference Bogaards, Helms and Lijphart2019: 351). Despite the critique of power sharing as becoming ‘increasingly vague, ambiguous, and even contradictory’ (Dixon Reference Dixon2011: 309), this review demonstrates that power sharing generally has positive effects, regardless of its institutional set-up, post-conflict transitional character and world region. Nevertheless, the findings should be treated with caution for two reasons. First, the review has focused on articles, to the exclusion of books, including some classic texts on power sharing. Second, the findings might be affected by general biases characterizing academic research such as the positive publication bias. The power-sharing literature might thus benefit from a systematic review (Dacombe Reference Dacombe2018) that evaluates the evidence base of all the quantitative studies included in the PSAD.

We use this conclusion to develop a research agenda for future research. The research agenda is mainly based on insights from the reviewed articles. However, the potential areas of research outlined below have neither been fully addressed in classic books on power sharing (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977; McGarry and O'Leary Reference McGarry and O'Leary1995; Norris Reference Norris2008) nor in recent volumes (Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2020; Jakala et al. Reference Jakala, Kuzu and Qvortrup2018; Keil and McCulloch Reference Keil and McCulloch2021; McCulloch and McGarry Reference McCulloch and McGarry2017). First, more research is needed to identify how the agency of political elites is shaped by and also shapes power-sharing institutions and social structures (Bogaards Reference Bogaards, Keil and McCulloch2021a). In his early theorization of power sharing, Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1968a) highlighted the role of elites and even defined power sharing as ‘government by elite cartel’ (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1969: 216). Later on, the literature took an institutional turn by focusing on the four institutional dimensions of power sharing: grand coalition, proportional representational, cultural autonomy and minority veto (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1977). From this institutional perspective, structural conditions are treated as favourable factors while the agency of elites is considered a requirement or a built-in assumption. Treating agency as a requirement, argues Matthijs Bogaards, presupposes the dominance of elites, as strategic actors, over structural conditions such as societal cleavages (Bogaards Reference Bogaards1998: 485). To date, the agency dilemma in power-sharing theory has not been resolved.

Answering the following questions might help bridge this gap. The first question is: why do elites behave similarly under different institutional arrangements or behave differently under similar ones? For example, in Iraq and Lebanon, despite having liberal and corporate power-sharing institutions, respectively, competition between elites has often resulted in gridlock and poor governance outcomes (Abu Ltaif Reference Abu Ltaif2015; Younis Reference Younis2011). Another question is: which institutional and structural configurations shape the decision of elites to cooperate and which ones do not?Footnote 13 In 1990, for example, a major opposition party in Fiji declined to take up its constitutional quota of cabinet posts after elections (Premdas Reference Premdas2002: 34–35). In contrast, the Kenyan elites' commitment to stability prevented the country from disintegration (Kagwanja and Southall Reference Kagwanja and Southall2009). Power sharing incentivizes not only cooperation but also outbidding (McCulloch Reference McCulloch, Crawford and Abdulai2021). Understanding which structural and institutional factors shape elites' actions is of paramount importance.

Second, the articles analysed in this review have primarily focused on the role of elites, to the neglect of citizens. The ability of elites to manage their group members and to ensure their support has been forwarded as a ‘requirement’ for power sharing (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1969: 216). According to McCulloch (Reference McCulloch2014: 512), ‘for consociationalism to work, elites must be able to collectively implement the terms of the peace settlement while still retaining the support of their respective constituents’. This, however, overlooks that elites are sometimes constrained by the demands of their groups (Barry Reference Barry1975). Thus, a useful question to ask is: when can political elites shape the actions of their group members and when do the latter constrain the way their leaders act? Clarifying the various citizen–elite linkages (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt2000) under power sharing is at the heart of this agenda.

Third, power sharing is based on the premise that divided societies have ‘sharp cleavages with no or very few overlapping memberships and loyalties’ (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1969: 208). The assumption is that such societies are composed of mutually exclusive groups based on attributes such as ethnicity, religion or race. In other words, the power-sharing theory overlooks ‘others’ under power-sharing systems (Agarin et al. Reference Agarin, McCulloch and Murtagh2018). Those others include marginalized non-dominant minorities (Agarin and McCulloch Reference Agarin and McCulloch2020; Stojanović Reference Stojanović2018) or women who are usually sidelined in power-sharing agreements (Sriram Reference Sriram2013).

Most importantly, the theory did not predict the emergence of ethnic parties that would appeal to voters beyond their own ethnic group (Murtagh and McCulloch Reference Murtagh and McCulloch2021). Nor did the theory allow for the possibility of the rise of cross-ethnic civic parties and social movements as is the case in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Lebanon and Northern Ireland (Agarin and Jarrett Reference Agarin and Jarrett2021; Deets Reference Deets2018; Milan Reference Milan2019; Murtagh Reference Murtagh2020; Nagle Reference Nagle2016). This begs the following question: why do cross-ethnic social movements emerge under some power-sharing systems but not others? In answering the question, the literature would greatly benefit from applying social movement theory to divided societies, something that has for a long time been neglected (Bosi and Fazio Reference Bosi and Fazio2017). Generally, crossing the ethnic divide is a significant move. The future will only tell if power sharing will be a ‘victim of its own success’ by diffusing the cleavages it was initially designed to manage (Andeweg Reference Andeweg2000: 515) or if citizens who feel marginalized under power-sharing systems will use contentious action to challenge the system from below (Agarin Reference Agarin2021).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2022.26.

Acknowledgements

The authors contributed equally to this article. We would like to thank the following contributors to the initial data collection and analysis: Amélie Vereecque, Björn Alex Scheffler, Jonas Ferdinand Winkel, Margarita Artemenko, Niya Georgieva, Tom Louis Klein, Yuting Tang and Zeina Gehad. For their very helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this article, we are indebted to Matthijs Bogaards, Timofey Agarin and Henry Jarrett. We express our gratitude to Silvia von Steinsdorff for her enthusiastic support to this project since its inception and to the bologna.lab at Humboldt University of Berlin for hosting this research project in its early phases.