Introduction

As Prince Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales and the future King Edward VII, approached his twenty-first birthday, his parents Queen Victoria and Prince Albert planned that he would have his own home in the countryside. This would be in addition to his base in London, Marlborough House, and the hope was that a rural holding would reduce the pressures and intrusions of life in the capital. The royal parents themselves had private homes at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, at Windsor Castle and at Balmoral in Scotland,Footnote 1 and they planned that such a country house would enable a healthy, outdoor lifestyle for the prince, which would suit his enthusiasm for hunting and shooting. From a number of potential properties, the Sandringham Estate in Norfolk on the east coast of England was selected, purchased with the prince’s Duchy of Cornwall income and this became his hunting seat and in due course a country home for his wife and children.Footnote 2 The building and associated land were to remain in the royal family’s hands after the prince ascended the throne and now, in the twenty-first century, they belong to King Charles III. There are many publications available in print and online that describe and discuss the history of the royal connection to, and enjoyment of, the estate but the present study is a new examination of the experiences of ordinary people during Prince Albert Edward’s ownership as Prince of Wales – the tenant farmers and their labourers, servants in the house and estate employees. In the absence of written Sandringham records dating from this period, the national censuses from 1841 to 1911, newspaper articles, illustrations and maps are used here to follow changes in occupations and demography, and a picture is given of the structure and movement of their everyday lives.Footnote 3 It will be seen how the increasing job opportunities associated with the new ownership encouraged migration to the village of Sandringham and its nearest neighbour, West Newton, about a quarter of a mile away. In some ways, the study is similar to the work of Michael Havinden, who researched the nineteenth-century progress of the estate villages of Ardington and Lockinge in Berkshire, which coincidentally were developed by a former equerry to the Prince of Wales.Footnote 4 David Dymond also used a variety of documents to investigate the Suffolk village of Wortham during the nineteenth century.Footnote 5 On the Sandringham Estate the prince’s love of blood sports promoted the employment of gamekeepers and woodsmen.Footnote 6 The household also needed staff, and although initially most of these were imported from other royal houses, local people could find openings and connect with a multitude of diverse persons. As well as this study of people, the natural history of the estate is considered, including how it altered and fostered wildlife of varying forms side-by-side with the developing human aspect of the domain. It contributes a ‘new way of thinking about nature and its relation to our lives’ as advocated by the ground-breaking Norfolk nature writer, Richard Mabey, and to the study of territorial organisations’ effects on landscape put forward by East Anglian academic and writer, Tom Williamson.Footnote 7 Further, it answers the call by Jonathan Finch to enhance understanding of estates by exploring them as inhabited social landscapes.Footnote 8

Background

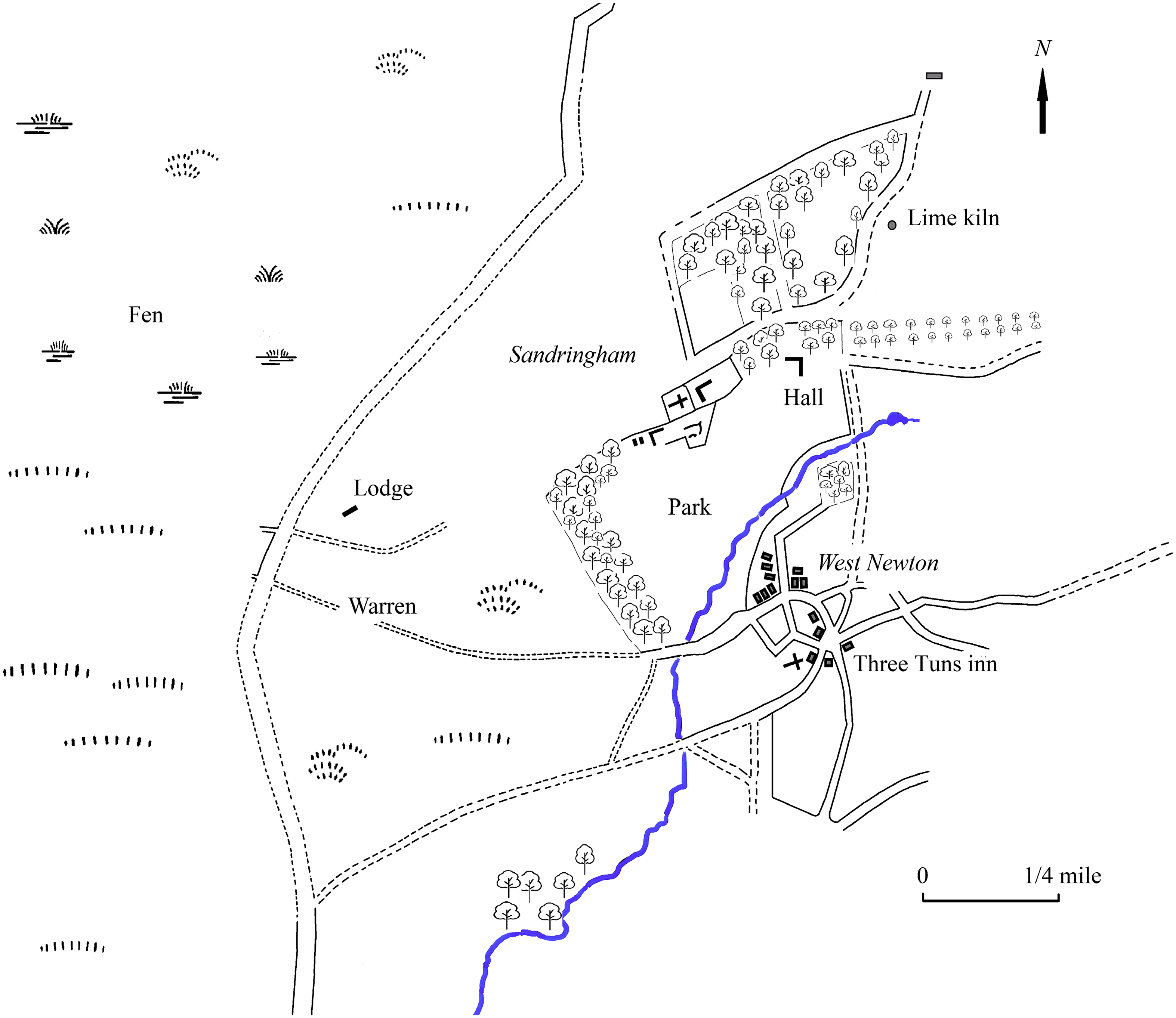

Sandringham merited a listing in the Domesday Book. It was small area that included a meadow, salt pit and about 120 acres of farmland but only one household. West Newton at that time, however, had 41 households, mills, fisheries and salt houses.Footnote 9 The landscape was rich in heathland from which an abundance of ironstone, a source of iron ore, was retrieved.Footnote 10 The two villages stand on sandstone, with chalk and silica sand nearby.Footnote 11 Just a few miles from the sea, William Faden’s Map of Norfolk (1797) shows Sandringham and West Newton separated from the bay known as the Wash by expanses of marsh and fen and there are also patches of common land, heath and higher-lying ground with Sandringham and West Newton both being about 100 feet above mean sea level (Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 12 The nearby river, the Rising, allowed for a flour mill and a paper mill. The wetlands around Sandringham supported a wide range of indigenous plant and invertebrate species, thereby encouraging fish, bird and mammal life.Footnote 13 There were likely to have been occasional ospreys as a few are recorded in places along the Norfolk coast: a ‘beautiful male’ was shot along with a spoonbill in Great Yarmouth in 1818; a ‘fine specimen in full plumage’ was shot by a gamekeeper on an estate about 50 miles from Sandringham in 1844 and a ‘beautiful male’ was shot down a similar distance away in 1847.Footnote 14

Figure 1. View from Sandringham to the north-west over fen and common.

Source: Illustrated London News, 20th December 1871.

Figure 2. Map showing Sandringham and West Newton.

Source: Redrawn from Faden’s Map of Norfolk (1797), Norfolk Record Office.

The landscape of deciduous woodland, with heather and waterways, encouraged wildflowers including bluebell, lily of the valley, gorse, marsh marigold and foxglove, with an associated summer soundscape of insects humming, and the trilling and warbling of seasonal visitors.Footnote 15 Heron and great bustard were recorded in the medieval and early modern periods along with crane, plover, pheasant, partridge, woodcock, hare and rabbit, and the marshy habitat encouraged snipe, curlew and geese.Footnote 16 The richness of the wildlife is reflected in the pursuit of quarry that took place. Foxhunting became established as a regular institution in 1752; in 1780 Henry Fickle was granted a licence to shoot game, and John Rose was convicted of poaching rabbits from the warren in 1843.Footnote 17 In 1856, over forty woodcock were killed when the incumbent of Sandringham entertained friends with a day of shooting.Footnote 18 Field sports, particularly pheasant shooting, probably played a part in the changing appearance of the countryside as evidenced by a comparison of Faden’s Map of Norfolk with Andrew Bryant’s Map of Norfolk (1826), which shows that although the avenue east of the hall was gone, a thick rectangle of deciduous trees was placed just south of that location. Furthermore, a ribbon-like plantation of similar trees about a mile and a half in length was established beyond the existing wood just north of the hall.Footnote 19 Species of tree were multifarious and included oak, ash, elm, maple, hazel, alder, birch and lime.Footnote 20 However, a map of 1836 shows that much of the woodland had been replanted with evergreens and a later timber sale indicates that the coniferous species were larch, spruce and ‘Scotch’ fir.Footnote 21 The map also depicts cultivated arable fields to the east of the Hall, a perfect habitat for hares.Footnote 22

The layout of roads at Sandringham was fairly simple in the early nineteenth century, with a driveway leading off from the highway to Lynn, passing by a lodge and arriving at the entrance to the Hall. At West Newton the situation was more complicated, with a medieval scheme of jumbled byeways and an open space between the inn and the church.Footnote 23 The number of dwellings is unclear from the early maps but an 1854 trade directory lists fifteen houses in Sandringham and fifty-one in West Newton.Footnote 24 Both villages accommodated an Anglican church with the rectors included in the lists of noteworthy residents. There was a smithy and an inn in West Newton and various trades are given including cordwainer, maltster, miller, bricklayer and grocer. Inspection of the 1851 and 1861 censuses gives more details about occupations including three gamekeepers and a warrener, dressmakers, servants, brickmakers and a builder, and many farm workers. There was a ratcatcher, several shepherds, a washerwoman, nurse, schoolmistress and a policeman.Footnote 25

By the mid-nineteenth century the estate infrastructure had become run down to a notable extent.Footnote 26 A farmer taking up a tenancy on the estate in a neighbouring village wrote, ‘[hearing poor reports] I was not prepared for much but my imagination had not stretched to the scene of dirt, ruin and desolation that greeted us’.Footnote 27 Even the seller of the estate to the Prince hoped that ‘the circumstances of the tenantry will be much improved’. The cottages in West Newton were small, some consisting of a single room downstairs and one upstairs and yet accommodating perhaps ten persons.Footnote 28 There were some so-called ‘double cottages’, which were simply a single cottage divided into two.Footnote 29 An advertisement for the sale of one of these ‘double’ cottages described only the garden rather than the living accommodation:

A double cottage in West Newton aforesaid with an orchard and garden ground containing and acre and a half or thereabouts, well planted with fruit trees now in full bearing.Footnote 30

The system of sanitation in labourers’ cottages was ineffective, many of them did not have privies and some of the wells were a mere 2 to 12 feet from the surface meaning that effluent percolated easily into drinking water. An outbreak of typhoid occurred in 1860.Footnote 31 There were, however, a small handful of more well-to-do members of the local residency who appeared on the electoral roll. These included tenant-farmer brothers Abraham and Samuel Cork in West Newton, leatherworker William Fox Clarke who acted as the census enumerator in 1861, and miller Samuel Twaites who lived and worked in West Newton but also owned land and dwellings in a neighbouring village.Footnote 32 The rectors of the two villages were, of course, also registered electors.

The early days of Royal ownership

His Royal Highness Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, decided to buy the Sandringham Estate after a two-hour viewing in February 1862, travelling through the ‘flat and featureless’ fens, past ‘wilder’ sea marshes, heaths and ‘unkempt and solitary’ farmhouses, a ‘silent’ lodge and a view of twisted oaks.Footnote 33 During the course of this first visit, two tenant farmers were introduced to the prince; he inspected the Hall and spent some time looking around farms. Analysis of the 1861 census gives a picture of the demography. Nearly 60 per cent of the 120 residents of the two villages giving an occupation were farm workers, so it is likely that the prince observed some of them. Sandringham village was the location of the Hall, which was the focus of the prince’s visit and there, although agricultural labourer was the most numerous single occupation, the number was equal to that of housemaids and servants combined. A schoolmistress lived in the rectory, as did seven young children with unknown places of birth so the children may have been foundlings. Most of the young residents aged over four years were listed in the census as scholars but it is unclear where they went to school.

Residents in Sandringham and West Newton were mostly born within 20 miles of the estate (onwards referred to as ‘locals’ or ‘locally born’). All of the children aged under twelve years who knew their origin were born locally but 11 per cent of older persons were born more than 20 miles away thus showing a little in-migration. Gamekeeper James Matthews relocated from Suffolk in the late 1840s, married a local woman and produced four children. Farmer Edward Sheringham was born a little over 20 miles away and grew up on a substantial farm about 15 miles from Sandringham and married a Cambridgeshire-born clergyman’s daughter. A different picture was seen with the lower classes as all but two labourers and their spouses were locally born. In the Hall, the housekeeper and one of the servants had relocated from Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire, over one hundred miles away.Footnote 34

There were seventy different surnames, excluding visitors, in the two villages, giving a surname index – which is a measure of number of surnames relative to population – of twenty-two.Footnote 35 However, when examining West Newton and Sandringham separately, they have indices of nineteen and forty-three, respectively. The lower index for West Newton indicates a small number of surnames relative to its size and thus a settlement of limited diversity and few kinship networks. The occupation indexes, which is the number of different occupations relative to the total population, repeat the pattern with six and twenty-two, respectively, showing less job diversity in West Newton. In the two villages there was a total of sixty married couples and in 70 per cent of these parings, both parties were locally born. Only 8 per cent of the pairs included a spouse who was born 50 or more miles away. A picture thus emerges of an estate in which most people are locals, but with a diversity of origin and occupation that was more noticeable in Sandringham village where the influence of the Hall was prominent.

The Prince of Wales concluded the purchase in early 1862 but took possession of the estate upon coming of age in November of that year.Footnote 36 Almost immediately there was speculation about implications for local improvements, including financial benefits. The directors of the East Anglian Railway projected that the area would become popular and that rail traffic would increase.Footnote 37 Initially intended as a base for countryside sport,Footnote 38 the prince took to the field enthusiastically from January 1863, hunting foxes and shooting game. He fired his first gun on 7th January 1863 and enjoyed two days of felling woodcock and pheasant. The following week saw a group of participating followers that was ‘extraordinarily large’, possibly numbering about five hundred, containing ‘all the sporting celebrities and leading notabilities’ of the county. Pedestrians ‘without limit’ were present.Footnote 39 There were security and privacy implications and during Irish Fenian threats towards the royal family, extra police were stationed nearby.Footnote 40 Along with this transformation of county society, there were also changes in the two villages. The total population grew by 37 per cent between 1861 and 1871 but whereas the number of children aged twelve years and under grew by 11 per cent, the number of older individuals grew by a remarkable 41 per cent. More working people were arriving and they hailed from a much more disparate range than earlier, including Scotland, Wales and France, with each accent, perhaps, sounding unintelligible to the other. At the Hall, three local women found employment as servants working alongside fellow household staff from London, Leicester, Hampshire and Hertfordshire. There were five police officers and new occupations included engine fitter, dog keeper, land agent, clerk and errand boy.Footnote 41 There was a London upholsterer who married a local woman and stayed locally for many years. His work in the mansion was seen by an American journalist who was given access:

upholstery of pale blue and brocaded with threads of gold and dark red. Other pieced were of pearl satin wrought with pink and silver. There were many odd chairs and easy chairs with velvet backs and seats hand-embroidered … antimacassar, scarfs and bows upholstered in with the covering.Footnote 42

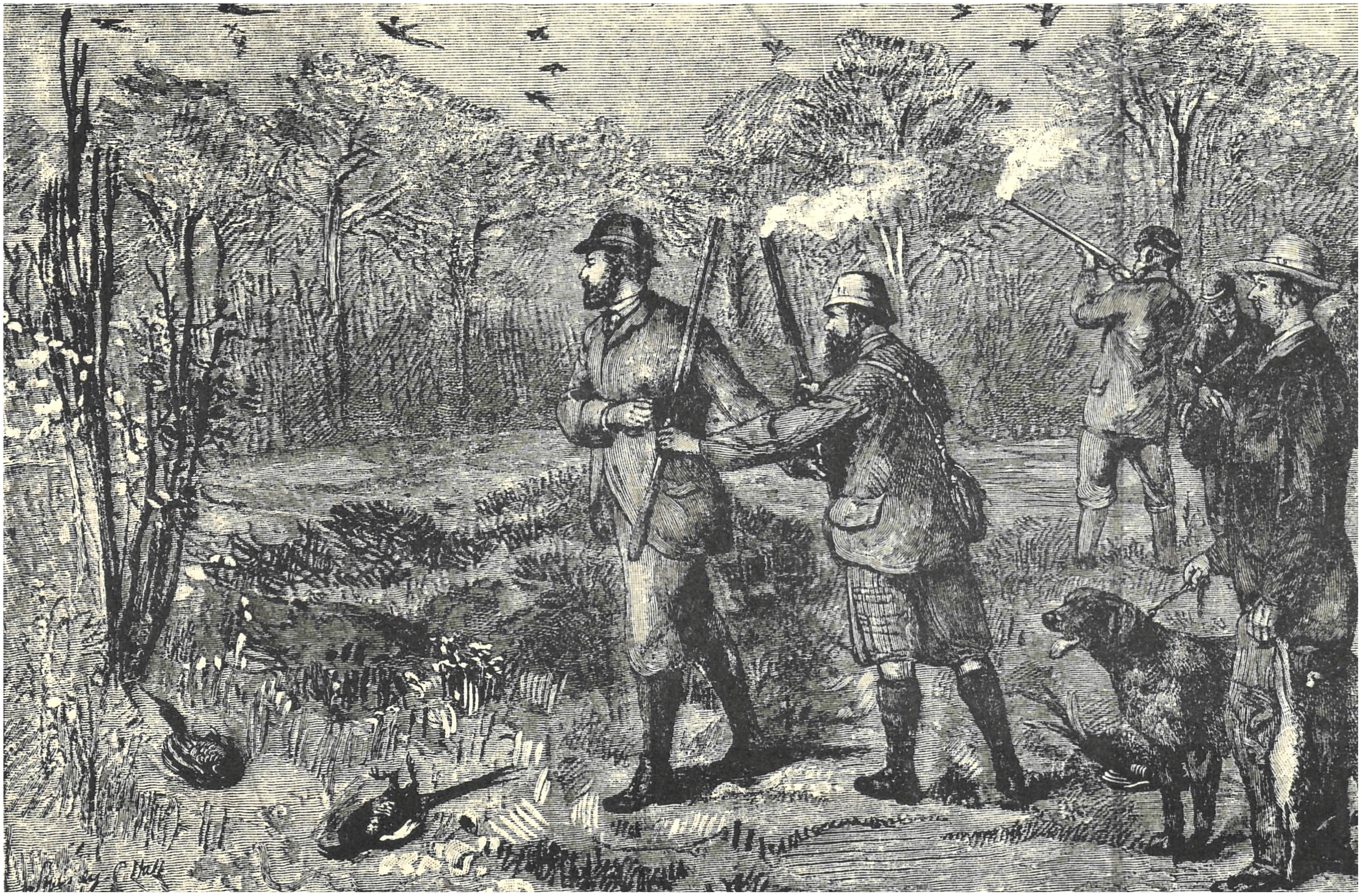

There were seven gamekeepers and a wood warden, following a trend started on the Hertfordshire estate of the first Earl of Verulam to enforce the preservation of game.Footnote 43 An 1865 photograph (Figure 3) shows a team of eleven gamekeepers, the head man carrying a gun the others with staves, and by patrolling the woods and countryside they thus formed an extra security force. One of the men in the photograph, but unidentified, is Goss Overton who later was promoted to head gamekeeper at Windsor showing the movement that was possible between royal estates.Footnote 44

Figure 3. Gamekeeping team, October 1866.

Source: Royal Collection Trust.

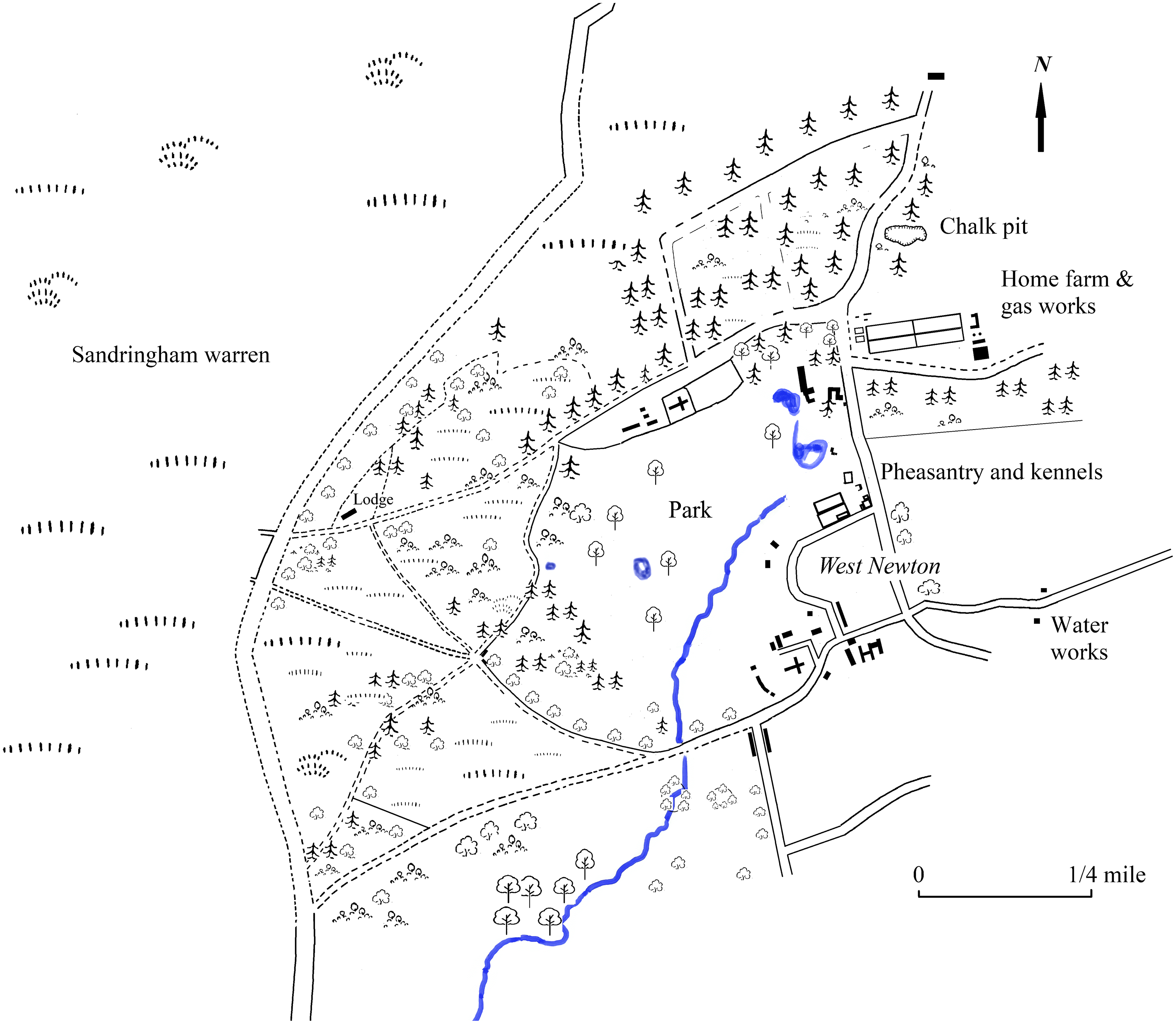

Some of the new-arrival employees obtained lodgings with locals, thereby helping with family finances. For example, the Swedish gamekeeper, John Svensson, lived with shoemaker William Clarke and his family in West Newton. The upholsterer Joseph Rainbow initially boarded at the Three Tuns Inn and the land agent’s clerk – who had moved in from only 15 miles away – lodged with the miller, Samuel Twaite. Most lodgers were agricultural labourers, which was still the most common single occupation and with two females being listed as ‘field workers’, they were 45 per cent of the total workforce who gave an occupation in 1871. In West Newton, the proportion of agricultural labourers was nearly 60 per cent – up from 54 per cent ten years earlier. This limited range of occupations in that village mirrored the restricted diversity of origin shown in the two villages of West Newton and Sandringham with 93 per cent and 52 per cent, respectively, being locals. There were two shepherds, and along with the increase in agricultural labourers, this reflected the prince’s farming activities. His Royal Highness took over the Cork brothers’ farm, established a home farm and kept a variety of breeds of sheep and cattle. There were about 400 acres of arable fields and grassland, and the firm pastures enabled a fast gallop on horseback and would hold the scent of a fox,Footnote 45 essential features of a top-class hunting arena. Deer from Windsor were imported into the park, and a number of exotic species were also brought in but from a much further distance, following a royal ‘kill and capture’ holiday in India in 1876. These included two bears that were kept chained to a pole in a pit near the kennels and shown to visitors.Footnote 46 It has been said that ornamental gardens of the period with their many foreign species, became ‘living maps of the colonies’, Footnote 47 and that the growing of tropical fruit in glasshouses was ‘cultivation of the colonies brought right into the heart of the estate’.Footnote 48 Here in Sandringham we see the exploitation of the Empire in the exhibition of these Asian animals.Footnote 49 The dog enclosure contained a range of speciality animals including Russian wolfhounds, Italian deerhounds, setters, terriers and bloodhounds, all of which displayed the prince’s prime interest in blood sports. Figure 4 shows a plan of the estate, which indicates some of the changes including that the water course had been diverted and new ponds created, and that a small portion of the former arable fields to the east of the mansion – now named Sandringham House – had been replaced with the new home farm, gas works and walled kitchen garden. These newly built features did not provide employment for locals, however, the gardeners initially being from Scotland then later from all parts of England except the local area. The gas fitter was Scottish and it is very likely that these were hitherto Balmoral employees.Footnote 50 It is of note that horses, gardens and industrial installations meant more male employees and a consequent higher wage bill and so this sort of endeavour was possible only for the very wealthy.Footnote 51

Figure 4. Map showing the estate in the early 1880s.

Source: Redrawn from the 1884 Ordnance Survey 6" and 1" maps.

The estate had been used for the pursuit of game for many years prior to the prince’s purchase and was ‘well stocked’ at the time of his first foray in early 1863. It was noted that the great bustard was driven away by plantations in the first half of the nineteenth century,Footnote 52 with these new forestry installations being unfavourable to their preference for extensive areas of flat or rolling arable land with few trees, as seen in Figure 1.Footnote 53 However, to satisfy the royal’s fascination with field sports, notable at a time when the efficient breech-loading gun was coming into use,Footnote 54 further woodland was put in place and at the beginning of 1865 the preserves were ‘better stocked with game than was ever known before’.Footnote 55 Ordnance Survey maps show that many evergreen species were planted, and although the deep shade within these woods is hostile to most wildlife, some bird species such as firecrest and siskin can thrive and were likely therefore to have been attracted to Sandringham. Nightjars can flourish at the plantation/heathland boundary and wildflowers can survive at the edges of the less dense tracks. Mrs Herbert Jones, writing in 1888, listed a variety of flower species in the district including bluebell and lily of the valley in Wolverton Wood, which was a deciduous plantation. However, in the plantations near Sandringham House, which were by the 1880s mostly evergreen, she describes only the ornamental trees bird cherry and crab [apple] ‘peep[ing] out from behind the firs’.Footnote 56 Mrs Jones also observed that wildflowers ‘spoiled the scent for the huntsman’, which could indicate one of the advantages to the prince of the thickly coniferous scene at Sandringham. On the side of biodiversity, evergreen needles – while containing less nourishment than deciduous leaves – persist longer and provide food for invertebrates through the winter months, which in turn support life further up the food chain.Footnote 57 Nevertheless, game birds themselves feed on invertebrate populations, which may have a knock-on effect for other species of bird.Footnote 58 The management of game birds, too, has implications for vertebrates as the feed put out, the protection offered by pens and reduced numbers of predators can encourage small mammals.Footnote 59 ‘Ever-increasing swarms of rats and mice’ were reported in 1911.Footnote 60 Establishment of hedges, coverts and overgrown fences was essentially to provide cover for foxes’ earths and good habitat for game birds,Footnote 61 and Figure 4 shows that many broadleaf trees were left in place or were planted in new areas, particularly lining roads. A newspaper description of the warren can help give a glimpse of the flora present at that time: willow varieties, downy birch, hawthorn, elder, ash and bramble. Furthermore, this sort of habitat is home to grasshoppers, warblers and buntings, and the heather-clad areas provided nesting grounds for curlews and plover.Footnote 62 The mixed nature of the countryside will have been home to many creatures including squirrels, redstart, goldfinch and lesser redpoll, larch tortrix moth, wood ants and stag beetles on decaying wood for example.Footnote 63 Figure 5 shows a newly planted border of evergreens side-by-side with established deciduous trees.

Figure 5. 1865 photograph showing Bachelors’ cottage. In twenty years’ time, the trees would become thick with conifers, which provided a screening effect, shielding the estate from nearby roads.

Source: Royal Collection Trust.

The prince’s overwhelming desire to hunt led to conflict with the local community, seen on sporting estates elsewhere in Britain and leading to considerable agitation in the 1870s.Footnote 64 It is said that at Sandringham, ‘without a by-your-leave to tenants’, new forestry was put across arable fields,Footnote 65 and farmers had to cope with crops being destroyed by rabbits and hares that were preserved for hunting. Furthermore, the beaters and other attendant personnel and vehicles contributed to the destruction of crops.Footnote 66 The warren was moved onto reclaimed land further to the west that used to be fen,Footnote 67 and the original warren was now partly converted into park and partly made into the aptly named Woodcock Wood. Prince Albert Edward attempted to introduce grouse from Scotland onto the warren but the initiative is said to have failed owing to the ‘wrong sort of heather’, and the land being ‘all cultivated and scrubby marsh’ but some black grouse were shot in 1895, which indicates a second attempt that may have had some limited success.Footnote 68

Later changes

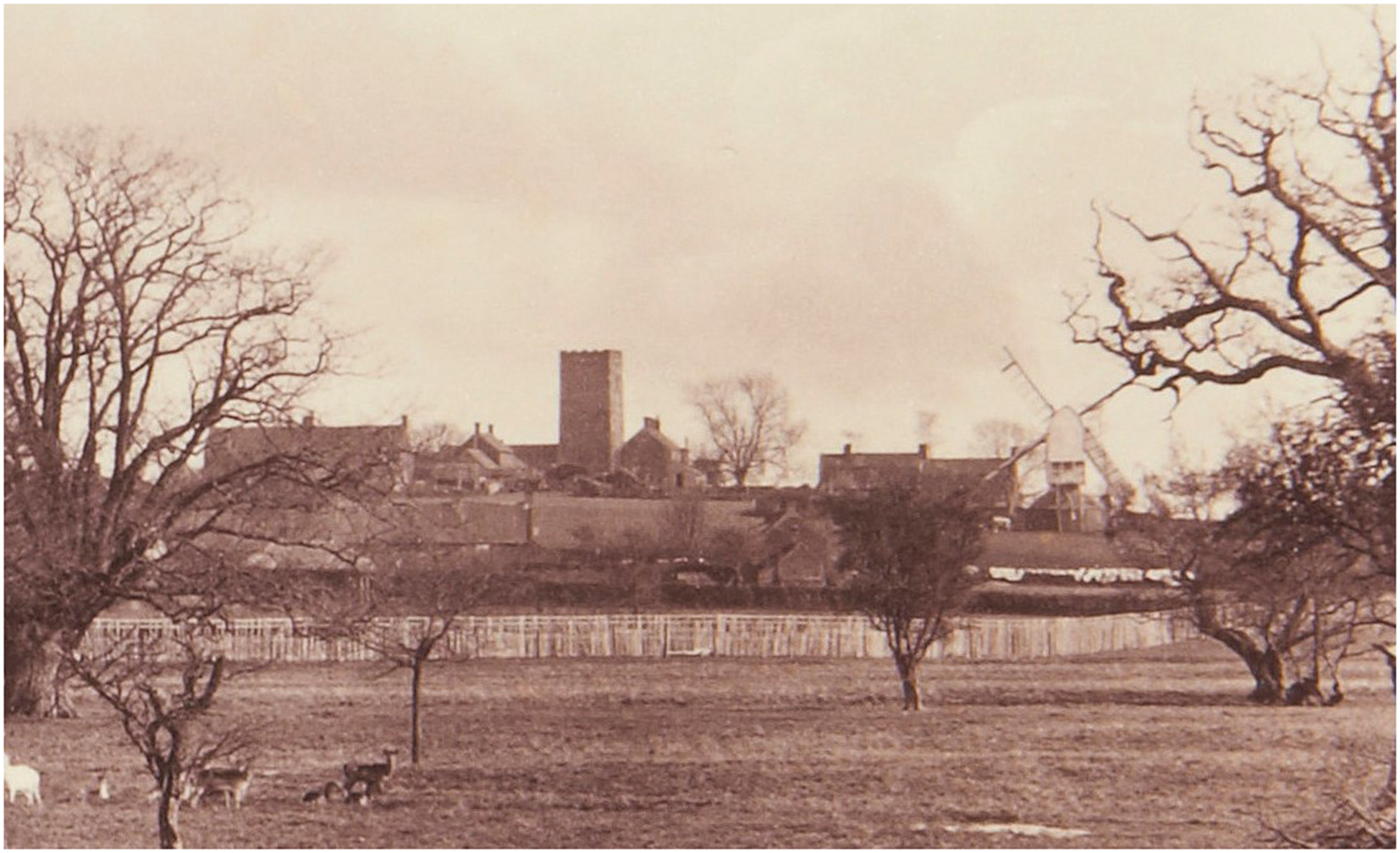

Between the drawing of Bryant’s Map in 1826 and the compilation of the enumerator’s census book in 1841, a windmill had been built just to the west of West Newton church. There are limited records of this structure but a photographer captured an image of it in 1871 (Figure 6). It was to be short lived as in 1875 Samuel Twaite, like the Cork brothers, sold up and moved away and the windmill was demolished.Footnote 69 An impression in dry grass can be seen in aerial photographs and, lying to the south of Sandringham House, its removal enabled the park to be enlarged and the view improved for the royal family.Footnote 70 The picture shows the ‘lofty, wood rabbit-proof fence’, which prevented the mammals from desecrating the new gardens within the park but kept them firmly within the exterior farmland.Footnote 71

Figure 6. View of West Newton from within Sandringham Park showing the park palings, church and windmill.

Source: Royal Collection Trust.

The shoddy cottages were demolished and the medieval layout was changed. This further enabled an extension to the park with replacement cottages erected, following a pattern of demolition and rebuilding established earlier in the century and seen for example at Castle Howard in Yorkshire.Footnote 72 The new model cottages helped to demonstrate the close relationship between the villagers and the estate core,Footnote 73 and the Norwich Mercury gave a description of the first of these new homes:

The cottages are of brick and carr[stone], with slate roofs; the windows and door frames are of English oak the former being of extra size to give an abundance of light to the lofty rooms. The cottages are set back 30 or 40 feet from the road so as to afford a neat garden in the front. The garden for the growth of vegetables extends back in the rear of each cottage about 100 feet. The road, which these cottages face has had an additional 10 or 12 feet thrown into it … Here also what was formerly a barn has been converted into a school room and a house for the mistress with a playground and garden in front.Footnote 74

The new accommodation did not always help the overcrowded and unhealthy conditions. Indeed, the innovative cottages and the increased business and prosperity of the estate seemed to magnify problems. A newspaper reported: ‘to meet the wants of the increased numbers of labourers who have been employed upon the Sandringham Estate since its purchase by the Prince of Wales … the evils have been much increased by the overcrowding by numerous lodgers into the cottages of ordinary residents’.Footnote 75

Similar conditions to those reported over ten years earlier still existed and more outbreaks of disease occurred in the 1870s. Despite increased work opportunities there were many poor people and Prince Albert Edward established traditions of providing payment in kind, in the form of meat and other items to locals. At Christmas and at other times such as royal birthdays, beef, coal, children’s clothing and bread were distributed.Footnote 76 The prince also began to give pensions and grace-and-favour cottages to long-serving labourers or their widows.Footnote 77 Dinah Piggins and Mary Smith, who were labourers’ widows, Sarah Riches who had been the ratcatcher’s wife, former farm labourer James Shipley and dairywoman Frances Barber, all received the grant.Footnote 78 Here the prince was being different to many owners of large estates who gave pensions only to senior staff such as housekeepers,Footnote 79 and it would have looked very poor indeed if widows from a royal estate had to go to the workhouse. There was also the possibility of transfer between royal residences. Norfolk man, James Lincoln, became a plain-clothes detective for the prince at his London home, Marlborough House, and later transferred to Sandringham. Lincoln will have known coachman William Harris who relocated from Sandringham to the London estate. Harris’s five-year-old daughter, who was born in Sandringham in 1866, is shown in the list of staff children at Marlborough House in 1871.Footnote 80 Labourer’s daughter, Ruth Smith, married one of the prince’s chauffeurs in 1894 and moved with him to the royal mews in Windsor. They were in Windsor with stableman Francis Stadden whose offsprings’ places of birth reveal movement between sites. The eldest Stadden child was born in Windsor in 1901, the middle two children were born in Sandringham in 1907 and 1909, respectively, and the youngest was born in Windsor in 1910.Footnote 81

Despite these benefits and higher rates of pay in some instances, illustrated by the rector of West Newton’s stableman defecting to the prince’s employ for a 17 per cent higher wage,Footnote 82 there were tensions, especially relating to game and its preservation for the prince’s field sports. Hares, rabbits and game birds were a blight to farmers with crops being ruined and the farmers facing prosecution if they attempted to remove the animals. A farmer from a neighbouring village formally objected and was vindicated,Footnote 83 but the less well educated were not so able to put forward their feelings. In 1885 labourer John Dye was prosecuted by the prince’s agent for destroying part of a meadow, and this may have been a protest as crop destroying was a well-known form of rural remonstration against unwelcome landlord actions.Footnote 84 A small group of offenders was prosecuted for playing ‘pitch and toss’ on the road in 1871.Footnote 85 This game, also known as ‘knurr and spell’ was a known protest against enclosure, with the pitched game involving a bat and a missile that could be a pretence for destruction of property.Footnote 86 An example of the prince’s control over the estate and the impact on working people’s lives is given by his demolition of the Three Tuns Inn, its replacement by West Newton House and that building’s subsequent use as a virtually teetotal working men’s club. Here locals, upon paying a membership fee, could obtain a maximum of one pint of beer per day; the rector of Sandringham was the president of the management committee and the prince retained the right to commandeer the premises at any time upon giving a week’s notice.Footnote 87 Swearing, betting and gambling were not allowed.Footnote 88 This may have been part of the late nineteenth-century push towards temperance in an attempt to improve local people’s lives,Footnote 89 and any drunken offences would have been unacceptable on a royal estate but this element of the prince’s development of Sandringham will have interfered with locals sharing ‘experiences of work … away from the eyes of their employers’.Footnote 90 There were some instances of drunken revelry being prosecuted in the local courts,Footnote 91 but there is no record of working-class response to the closure of the inn. Nevertheless, after some time the prince removed the one-pint restriction at the working men’s club,Footnote 92 and from this we can deduce that there had been objections or limited uptake of membership. It is said that relations between the Prince of Wales and his tenants were good, and during a visit by Queen Victoria in 1889 a loyal and enthusiastic address was given to Her Majesty.Footnote 93 However, it is of note that those men from West Newton and Sandringham who took part in this presentation were Edward Sheringham, a gentleman farmer, and middle-class Frank and Edmund Beck. The Becks’ supportive words to the Queen paid off, for the Prince of Wales made Frank Beck his Sandringham agent, a job he retained when the prince became king.Footnote 94 In another example of control, Prince Albert Edward even dictated his Anglican employees’ Sabbath activities to an extent as he monitored their church going and insisted on unfailing attendance.Footnote 95 Furthermore, even though household staff received fair wages, some agricultural labourers complained about their level of remuneration, even involving trade unions to campaign on their behalf. Here, the example set by royals to other employers was invoked by the unions as a method of leverage.Footnote 96 The Prince of Wales may have considered his dictates about church attendance and temperance to be a fair exchange of demands as he provided and maintained new cottages, renovated the churches,Footnote 97 provided modern schools, paid employees their wages and gave pensions. As well as these matters, a custom was established whereby The Prince of Wales paid the medical bills of employees and their dependants.Footnote 98 There were some Nonconformist believers on the estate including Wesleyan and Primitive Methodists.Footnote 99 The Prince of Wales took ‘a kindly interest’ in them, providing a pension to one long-term but infirm pastor, and the prince even built a chapel for the Primitive Methodists. This, however, was only after the congregation acquired an old railway carriage for meetings and installed it in a field a few miles from Sandringham House. This could be considered a deliberately provocative act on an estate where good order was paramount – and their method was effective in this case, gaining them new premises.Footnote 100

When the royal party was present at Sandringham House, the population was dramatically altered. A staggering 41 per cent of adults were from outside the local area, comprising mainly household staff and servants from all parts of the British Isles and overseas. The Princess of Wales’s lady-in-waiting was born in Madeira and the prince’s equerry originated in Malta. A footman and one of the police officers were German, the chief cook French.Footnote 101 The 1891 census provides a snapshot of this colourful scene and shows that, nearly thirty years after the prince’s purchase, several maids, men servants and those with roles including telegraph clerk and groom were locally born. A small handful of gardeners and dairywomen were locals, so was the gardener’s boy, and West Newton-born Alfred Harrod had found a job working with the dogs. Some employees were recruited following advertisements in local newspapers.Footnote 102 The prince’s foresight in commissioning the building of sixteen dormitories over the stables showed its value as twenty-six grooms and coachmen were billeted there,Footnote 103 although this arrangement of sleeping quarters might have been considered old-fashioned, as such dormitories in other properties that had survived into the later Victorian period were regarded with moral suspicion and ‘soon got rid of’.Footnote 105 Royal connections further led to vibrant episodes that most working-class people, apart from those living on similar estates, would never see. The Tsarevitch of Russia visited and the King of Portugal shared a sojourn with the Crown Prince of Denmark and a prince of Greece. The Kaiser stayed for a few days at a time when Anglo-German relations were becoming increasingly volatile. On such occasions, huge shooting parties, feasting and musical celebrations took place with celebrities such as Desider Gottleib, a London-based Hungarian bandmaster, or thespian Henry Irving performing for the guests. The Kaiser’s party reputedly shot in a morning a total of 919 pheasants, forty-one partridges, ninety-one hares, 211 rabbits, nine woodcocks and two wood pigeons.Footnote 106 This amount of game was only a small part of the overall total for the season, which was likely to be in the region of several thousand. For example, in the season 1896–7, over 14,000 pheasants were shot by parties that included German and Austrian nobility.Footnote 107 It has been argued that around Britain part of the excitement of shooting was the setting of records, and Prince Albert Edward was not the only owner of a great estate to set up and grow a game department. At Longleat, for example, the Marquises’ of Bath spending on their pheasantry increased by over 1,000 per cent between 1790 and the 1880s.Footnote 108

While images of the royal family are plentiful and easy to find, the working people of the estate are rarely captured. The nature of Sandringham as a famed field sport centre has, however, enabled some of the staff to be pictured and identified. Figure 7 shows an 1885 shooting scene with a late middle-aged dog handler prominently in the foreground. This is likely to be 64-year-old John Elder, who had worked for the royals for many years, initially at Windsor. In the background are two gamekeeper’s carters probably 34-year-old Robert Crisp and 40-year-old Samuel Riches.Footnote 109 The dairywoman in Figure 8 could be Celia Flegg who was living in Princess Alexandra’s model dairy in 1891,Footnote 110 and the kilted man with the gun in Figure 9 was probably Archibald MacDonald who was personal attendant to the prince and who would wear Highland dress whenever possible.Footnote 111 The dog handler in this figure could be 28-year-old William Brunsden who took over when John Elder retired with a pension from the Prince of Wales.Footnote 112 An unknown estate worker is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 7. The Princess of Wales Inspecting Game (1885).Footnote 104

Figure 8. The Princess of Wales’s dairy, c. 1890–1910.

Source: Royal Collection Trust.

Figure 9. The Prince Shooting (1885).Footnote 117

Figure 10. An unknown gardener in Sandringham Park, 1863.

Source: Royal Collection Trust.

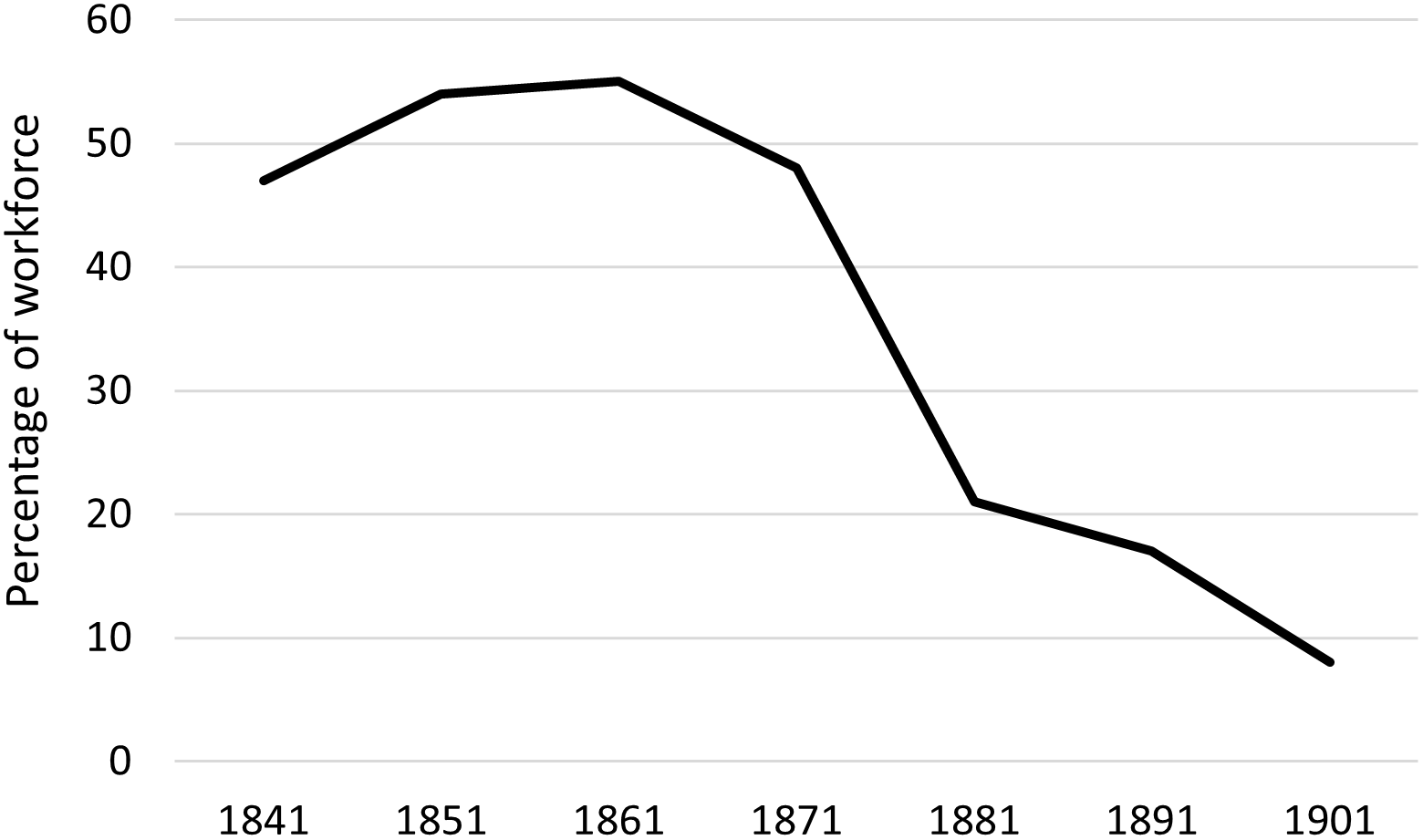

The prince’s and tenant farmers’ investments in new technology were apparent in a number of ways. The proportion of farm labourers fell dramatically after 1871 (Figure 11) and investigation of the census helps to explain why. At a time when the prince and his staff were keeping abreast of new developments in farming including purchasing a revolutionary hay-processing machine and a novel cream separator, and hosting conferences on new methods,Footnote 113 two new occupations appeared, namely ‘teamster on farm’ and ‘horseman on farm’.

Figure 11. Percentage of agricultural labourers in West Newton and Sandringham.

These were the gangs who operated horse-drawn mechanised farm tools such as the plough, hay rake and cultivator.Footnote 114 George Melton, William Ringer, William Painter, James Woodward and John Piggins, for example, had all been farm labourers in 1891 but were horse workers on farms ten years later. Men with specialist competences were needed for the new gas works, water works, electricity-generating plant, stud farm and horse hospital, and skilled women were needed following the Princess of Wales’s establishment of a girls’ technical school. Initially superintended by German-born Fraulein Noedel, here items such as knitted stockings, dresses and embroidered pieces were made. The establishment of this educational facility enabled local women and girls to acquire skills that helped family finances in the long run as well as giving employment to teachers and support staff. Sarah Aves, Mabel Crisp and Edith Harrod gave their occupations as ‘dressmaker/sewer at the technical school’ and Fanny Young was ‘assistant at technical school’.Footnote 115 There was a similar establishment for boys and both ventures produced and sold goods to help raise funds towards school costs, although the princess herself supported the enterprises financially.Footnote 116

The princess was staying at Sandringham in 1901 when she received the news that Queen Victoria had died and she and her husband were now king and queen. The new king made it known that he had no intention of relinquishing the estate upon his accession and the queen consort was said to fully share his affection for Sandringham, stating that ‘she had spent her happiest days there.’Footnote 118

Discussion and conclusions

There are many publications available that discuss the history of Sandringham and which focus solely on the royal experience. This new study sheds light on the lives of estate residents, looking at how occupations and demography changed over the period from when Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, first acquired the holding in 1862 to when his status changed as he ascended the throne and became king in 1901. It shows how the estate, part of a much wider royal portfolio, impacted on this section of eastern England. Furthermore, a parallel investigation into the estate’s ecology was undertaken, which shows how the biome – or community of flora and fauna – followed a similar pattern of change and development.

Mark Girouard has described how new owners of land holdings sought power and prestige but this was obviously not the case for the prince, rather it was having a home away from London, and north-west Norfolk’s potential for prolific field sports that was at the forefront of his intentions. It is in the building of this hunting and shooting environment that we first saw the side-by-side changes that faced the people and the biosphere. When the Prince of Wales bought the Sandringham Estate in 1862 there was immediate speculation about the economic effect the purchase would have on the area. There would be a social premium attached to having royalty in the midst of north-west Norfolk and increased trade and human traffic would have a monetary benefit. Indeed, a revitalised local economy was established, which saw increased numbers of estate gardeners and woodsmen, the planting of acres of evergreen and deciduous trees and the preservation of game types that were detrimental to the fortunes of farmers. New and increased numbers of some species came to live in the new forests of Sandringham, which were favourable as their habitats. These included the nightjar, ‘a great density’ of which was reported on the estate later in the twentieth century,Footnote 119 but the coverts ensured that the great bustard never returned and increased numbers of gamekeepers guaranteed the exclusion of birds of prey.

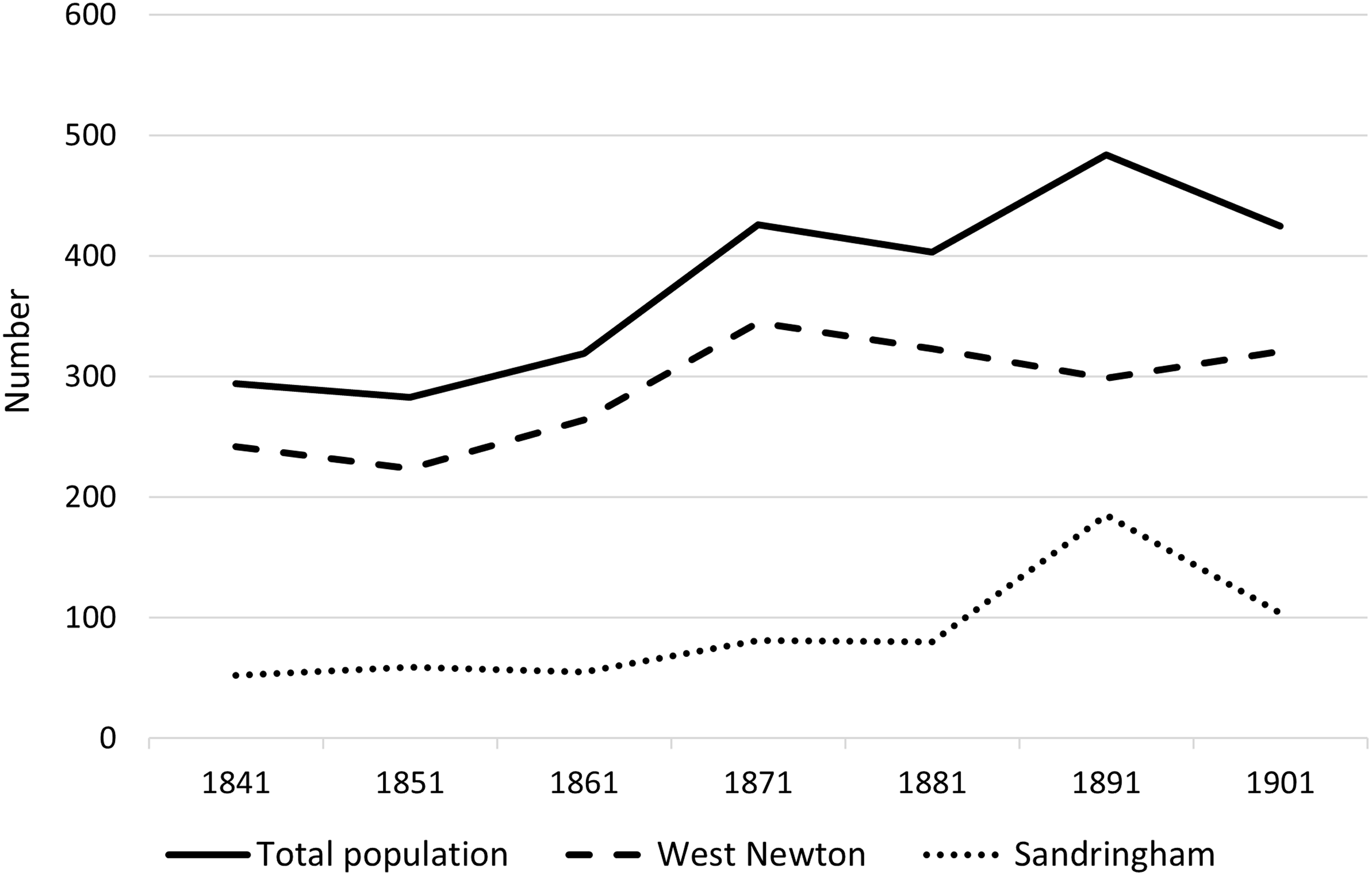

Initially many staff were imported from other royal residences. The number of Scots groundsmen and household staff is of note and Queen Victoria had known Scots-born housekeeper Margaret Stewart since childhood so it is likely that the whole Stewart family was part of one of the royal households.Footnote 120 A study of the 1901 census shows the demographic characteristics existing forty years after the prince’s purchase, and comparisons with the 1861 figures show remarkable changes. Figure 12 shows the general increase in population following the middle part of the century.

Figure 12. Population changes from 1841 to 1901.

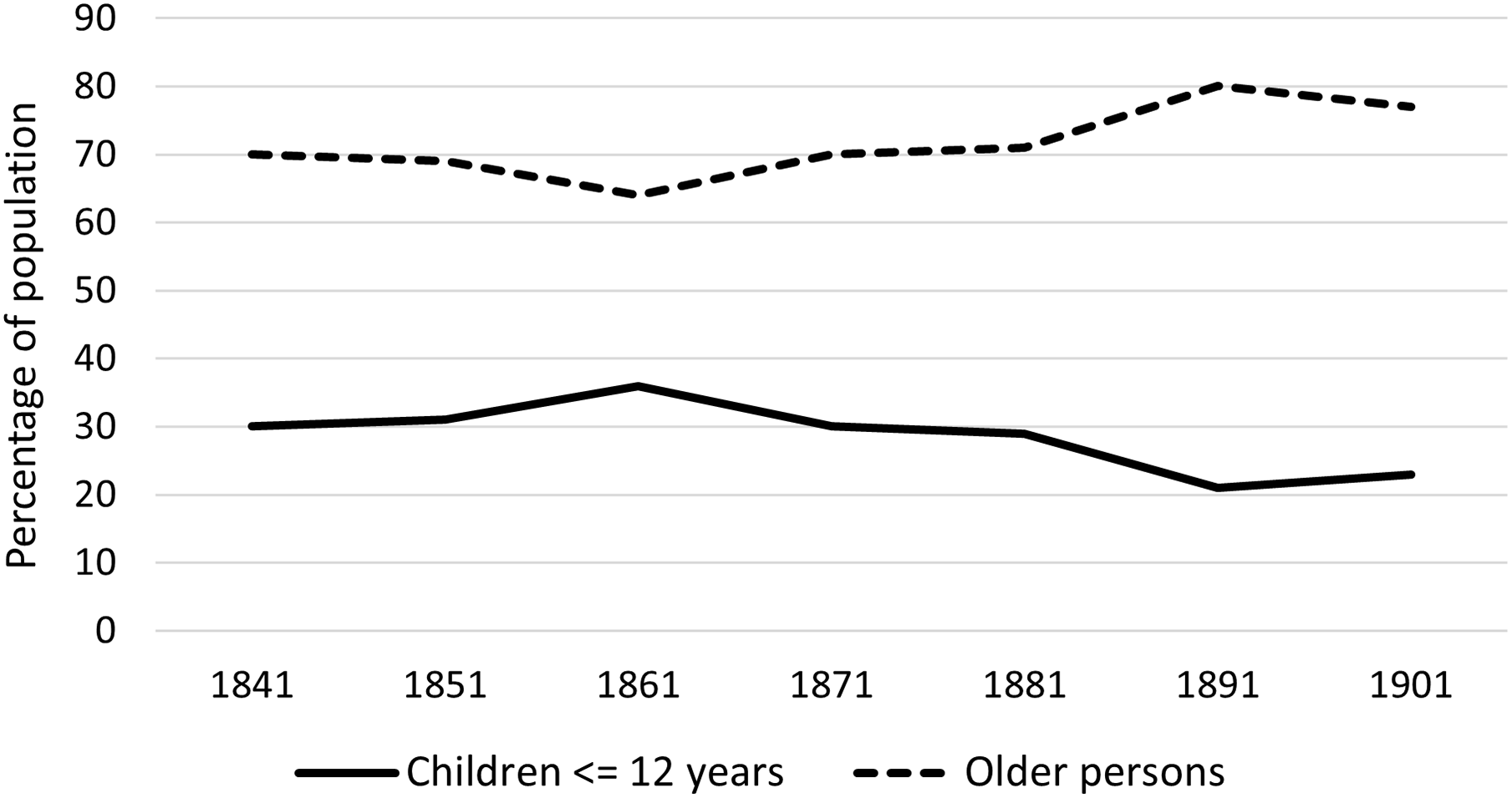

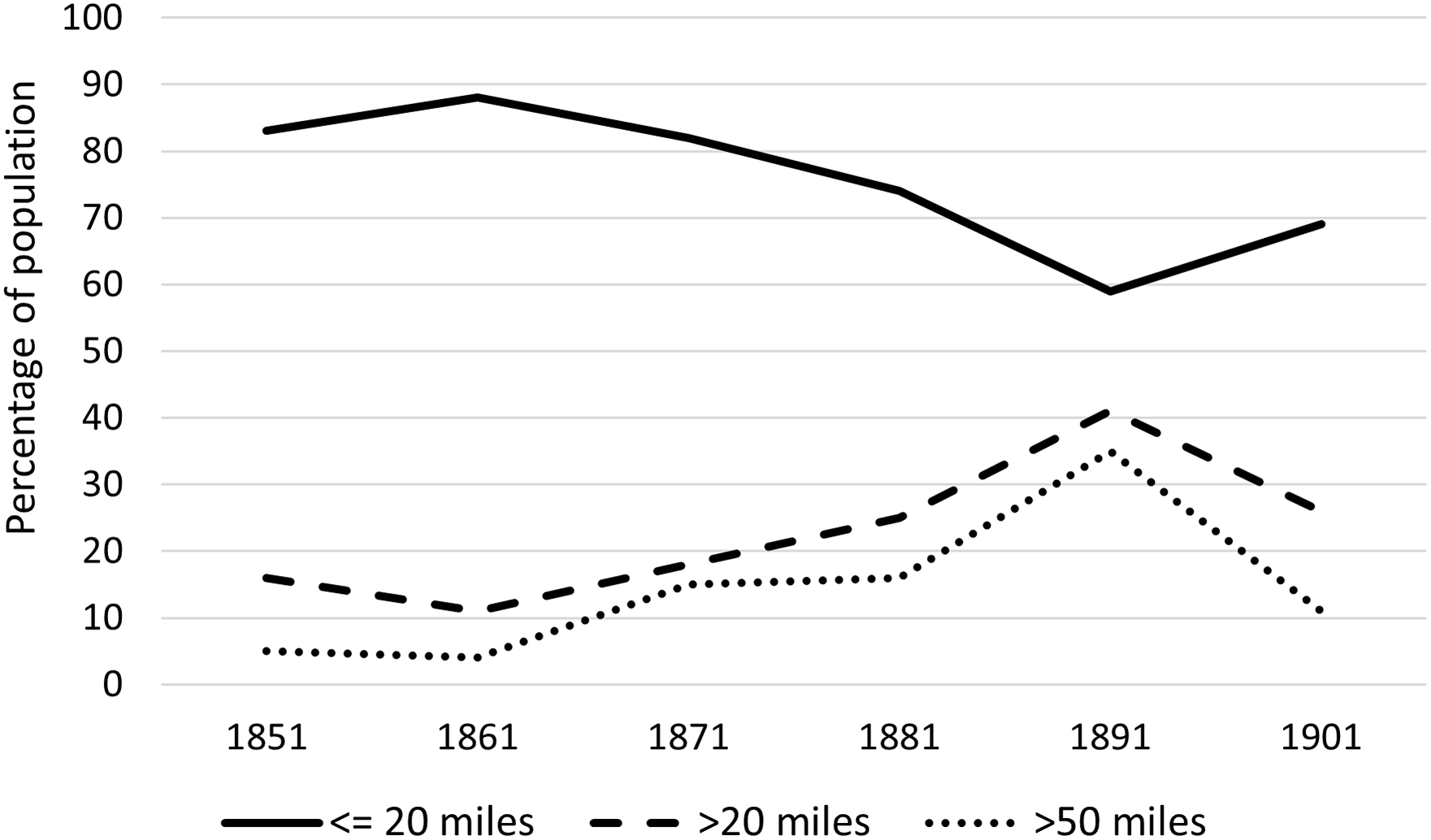

Clear from the graph is the effect on Sandringham of the visiting royal party in 1891 when Sandringham village saw a notable increase in adults. However, when the census was taken two months after the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, the prince was now His Majesty King Edward VII, and there was transition at Sandringham that helps to explain the small increase relative to 1881.Footnote 121 Figure 13 shows the relative percentages of younger and older persons and indicates how the working-age population grew proportionately larger as occupational opportunities increased. Figure 14 gives an indication of migration patterns and shows without doubt that incomers were replacing a sizeable proportion of the earlier local community. This had an effect on marriage patterns; whereas in 1861, in 70 per cent of couples, both parties were locally born, in 1901 this proportion was now 60 per cent. Where previously in a mere 8 per cent of couples, one or both parties was born 50 or more miles from Sandringham, in 1901 it was 27 per cent. This demographic feature has been noticed in communities elsewhere and explained by factors including increased mobility because of new railways and erosion of local customs and prejudices.Footnote 122 It has been shown here how the Sandringham Estate became more open and very much less self-contained after the royal purchase.

Figure 13. Percentage changes of younger and older residents.

Figure 14. Graph showing migration patterns.

The nature of the Sandringham Estate altered enormously because of the novel work-related opportunities that became available. Whereas West Newton was mainly agricultural with a few industrial and service jobs in 1861, by 1901 the village included policemen, stud grooms, employees at the technical schools, servants, a land agent, post office clerk and other postal workers, carpenters, engine drivers and many with horse-handling skills. This explains why, unlike many post-1851 farming communities, West Newton saw an increase in population following the decline of the 1880s.Footnote 123 The overwhelming difference was the new sphere of women’s work. Whereas in 1861 there were few named female occupations, forty years on there were multifarious roles for women, with several at a higher level, for example schoolmistresses and senior staff in the royal household. Local women Rhoda Boughen and Thirza Sherwood were, respectively, teacher at the technical school and cook at Sandringham Cottage, and many local women found work as maids or in the princess’s model dairy. Diverse occupations were even more readily available for men, at higher and lower levels. Training and the acquisition of skills became increasingly available as the royal estate became more established, and a prime beneficiary of this was Alfred Harrod whom we first saw as a dog keeper in 1891. In 1911 he was now a keeper at London Zoo and no doubt his experience with the animals at Sandringham facilitated this transition.Footnote 124 Others who changed roles when royal circumstances altered in 1901 were William Mann who had been postmaster in Sandringham House but became a grocer in Kings Lynn, and John Salmon who left his gamekeeper job in Sandringham and took the same post at the Warnham Court estate in Sussex. Gardener’s boy George Flegg became a police constable in London, and Sidney Crisp, hitherto a servant for the prince’s land agent in Sandringham, became chef at the Duchess of Hamilton’s hunting lodge.Footnote 125 Housemaid Ruth Salmon married a gardener who took a new post in the gardens of the Marquis of Hertford in Warwickshire, and cook Thirza Shearwood married a labourer and stayed local. Both women gave up paid employment. Walter Rutland kept his job as a groom in Sandringham but now listed his employer as Her Majesty Queen Alexandra.

This investigation of the Sandringham Estate has followed the development of the royal holding from its inception. Changes in demography and working practices were very clear but a constant was the prince’s love of and participation in blood sports, which was the basis of the estate’s employment expansion and ecological impact. However, this article is not another presentation of the royal experience at Sandringham. There was more of significance on the estate, and a hitherto hidden history has been revealed in this study, which provides a remarkable and striking view of history ‘from below’ set immediately beside the royal family.