The preceding chapters have shown how welfare workers shape the welfare state by tracing their influence on the development of mental health care in the United States and France. Despite initially similar conditions in the two countries, postwar public mental health employees in America were not able to form coalitions with their managers, while those in France were successful at doing so. This difference produced contrasting cycles of negative and positive supply-side policy feedback in mental health care in the second half of the 20th century – precisely when policy-makers sought to “deinstitutionalize” the mentally ill out of hospitals, partly to reduce costs (see Figure 6.1). While France maintained and expanded the supply of public mental health care services even as psychiatric deinstitutionalization progressed, the absence of political pressure from their American counterparts facilitated the opposite result in the United States. A half-century after the push for deinstitutionalization, the supply of mental health care in France is nearly three times that of the United States (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.1 Supply-side policy feedback model: Effects of public sector worker alliances on the supply of public social services for disenfranchised populations (basic diagram of theoretical argument)

Figure 6.2 Scatterplot of psychiatric beds and community care facilities per 100,000 in 16 high-income democracies, with percentage of health budget allocated to mental health (as available) and line of best fit

Although much can be learned by contrasting these paradigmatic and influential cases, some questions nevertheless remain. To what extent did the generosity of the French welfare state, with its emphasis on state welfare provision, tilt the trajectory of mental health care in that country toward robust public provision? To what extent did the fragmentation of American society – racial and governmental – curtail the possibilities for social solidarity in this policy area? To what extent are these outcomes attributable more to the varying strengths of the labor movements in each country than to the coalitions of public workers and managers in mental health? And, in the case of mental health policies developed in the 1970s and 1980s, to what extent did public managers’ secondary identities as psychiatrists shape their preferences and political influence? The previous chapters have addressed these alternative explanations through both structured comparison and within-case process analysis; however, the evidence has been limited to the French and American cases, that is, to the countries that produced those questions in the first place.

Another way to assess the causal importance of these lingering questions is by testing the argument outside of the primary comparative cases. This chapter offers that analytic check. I examine whether and how coalitions within the welfare workforce shaped policy feedback in mental health care in Sweden and Norway. These two Scandinavian societies share much in common that control for the above explanations: statist welfare provision, ethnic homogeneity, a long history of social solidarity, and a powerful trade union movement (see Mill Reference Mill1874; also Slater and Ziblatt Reference Slater and Ziblatt2013; Tarrow Reference Tarrow2010). Yet when it comes to mental health care, these two cases are polar opposites. Norway’s supply of mental health care is significantly higher than that of Sweden (see Figure 6.2), whose dramatic reduction of psychiatric care in the 1990s in fact paralleled that of the United States earlier in the century. Evaluating the external validity of the argument in these two “shadow cases,” then, can determine its robustness (see Soifer Reference Soifer2020). Moreover, the selection of these two cases can assess whether the argument “travels” across all three “types” of welfare states: liberal (United States), conservative (France), and social democratic (Norway and Sweden) (see Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990). The following pages first introduce Sweden and Norway’s mental health systems and their similar starting points; then present evidence documenting the supply-side policy feedback theory at work in each case; and close by assessing the major alternative explanations, including the counterargument that Norway’s access to rich oil revenues overdetermined the policy outcomes in that country. But as the evidence nonetheless shows, the presence of a coalition between managers and workers in Norway and its absence in Sweden indeed played a role in their diverging approaches to psychiatric deinstitutionalization.

Different Outcomes, Similar Societies

The differences observed between Sweden and Norway in Figure 6.2 emerged only at the very end of the 20th century (compared to France and the United States, where the divergence began decades earlier). In the 1990s, Sweden and Norway each underwent significant reforms in their mental health care sector, with opposite results. Their initial aims matched the deinstitutionalization reforms in other countries, including those of France and the United States in prior decades (see Chapters 4 and 5). As elsewhere, deinstitutionalization in Scandinavia first began in the mid 20th century, when the postwar expansion of the welfare state rendered life outside the “asylum” possible for its residents (see Chapter 2). But it was not until the 1990s that the governments of Sweden and Norway took formal steps to make this process national policy.

Under the 1995 Psychiatry Reform, the Swedish Parliament (Riksdag) amended preexisting legislation (the Social Services Act) to formally devolve responsibility for the nonmedical care of the mentally ill (i.e., social services, such as housing and employment services) from the county to the municipal level. The logic of this decision will be familiar to readers by now, as doing so would allow the country to depopulate its county-level mental hospitals (until then, the default custodians of the long-term mentally ill). To facilitate this transition, the central government provided the municipalities with a short-term implementation grant: 1.2 billion Swedish krona over a two-year period (about $200 million contemporary USD; per OECD 2023; SCB 2023). As a result, the patient population residing in county hospitals plummeted by a third, but relatively few municipalities developed sufficient compensatory social services (Malm et al. Reference Malm, Jacobsson and Larsson2002; Silfverheim and Kamis-Gould 2000). These outcomes have garnered the 1995 reforms a public reputation as a “policy failure,” or in the poignant words of the leading Social Democratic politician Lars Engqvist, a “disgrace for Sweden.”Footnote 1

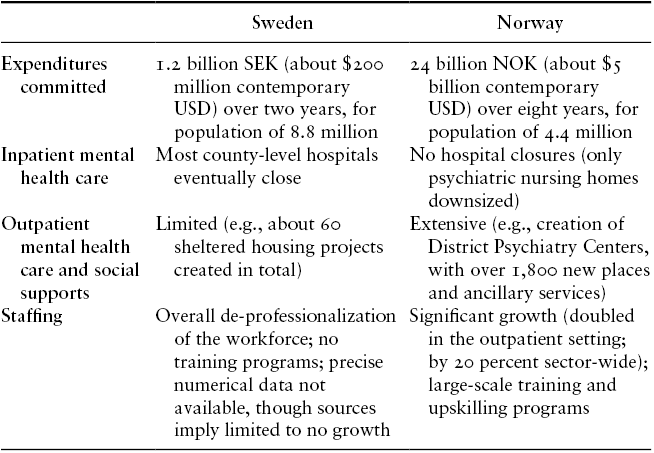

On the heels of that Swedish reform, in 1996–98, the Norwegian Parliament (Storting) opted for a different approach to a similar policy problem. To deinstitutionalize the mentally ill living in its county-level long-term care institutions, Norway repurposed some of those facilities. Psychiatric nursing homes became outpatient “district psychiatry centers” (distriktspsykiatrisk senter). Moreover, Parliament provided ample funds to both county and municipal governments to develop other services for people with mental illness via a decade-long “Escalation Plan.” The funds, which in total amounted to 24 billion Norwegian krone (or about $5 billion contemporary USD; per Norges Bank 2023b; OECD 2023) disbursed over eight years, allowed local governments to develop longer-term plans, including those that required hiring new personnel. The funds would go further in Norway, too, as its population was about half that of Sweden’s. Indeed, the outpatient mental health care workforce doubled during this time (Romøren Reference Romøren, Hatland, Kuhnle and Romøren2018). The effects of this initiative on the supply of mental health care in Norway therefore were quite different than in Sweden’s case. Between 1998 and 2007, inpatient care declined by 1,800 beds (mostly in psychiatric nursing homes), but it was fully replaced – even exceeded – by 1,865 new places in the outpatient district psychiatry centers and a range of new ancillary services. A direct benefit to mental health workers, further, was the rise in staffing levels: about a 20 percent increase overall and doubling in the outpatient setting alone (Romøren Reference Romøren, Hatland, Kuhnle and Romøren2018). Table 6.1 summarizes the main differences between Norwegian and Swedish mental health policy outcomes.

Table 6.1 Divergent results of mental health policy reforms in Sweden and Norway in the 1990s

| Sweden | Norway | |

|---|---|---|

| Expenditures committed | 1.2 billion SEK (about $200 million contemporary USD) over two years, for population of 8.8 million | 24 billion NOK (about $5 billion contemporary USD) over eight years, for population of 4.4 million |

| Inpatient mental health care | Most county-level hospitals eventually close | No hospital closures (only psychiatric nursing homes downsized) |

| Outpatient mental health care and social supports | Limited (e.g., about 60 sheltered housing projects created in total) | Extensive (e.g., creation of District Psychiatry Centers, with over 1,800 new places and ancillary services) |

| Staffing | Overall de-professionalization of the workforce; no training programs; precise numerical data not available, though sources imply limited to no growth | Significant growth (doubled in the outpatient setting; by 20 percent sector-wide); large-scale training and upskilling programs |

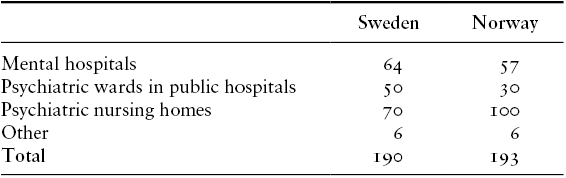

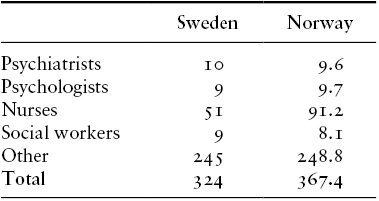

That Sweden and Norway diverged so much on the deinstitutionalization of mental health care is surprising because, prior to these reforms, their systems were very similar. As is evident from Table 6.2, in 1990 the population-adjusted supply of psychiatric care was almost identical in both countries. The distribution of these services varied only slightly. Sweden provided more inpatient care in hospitals (mental and general) than Norway, where psychiatric nursing homes often offered that care instead. Note that the size of the mental health workforce was similar, too (see Table 6.3). Although Norwegian psychiatric nurses outnumbered their Swedish counterparts, the density of other mental health care professionals was about the same in the two countries.

Table 6.2 Supply of mental health care in Sweden and Norway prior to the reforms (vårdplatser, “care places” – or beds and patient spots – per 100,000 population in 1989–90)

| Sweden | Norway | |

|---|---|---|

| Mental hospitals | 64 | 57 |

| Psychiatric wards in public hospitals | 50 | 30 |

| Psychiatric nursing homes | 70 | 100 |

| Other | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 190 | 193 |

Table 6.3 Mental health care workforce in Sweden and Norway prior to the reforms (per 100,000 population in 1989–90)

| Sweden | Norway | |

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatrists | 10 | 9.6 |

| Psychologists | 9 | 9.7 |

| Nurses | 51 | 91.2 |

| Social workers | 9 | 8.1 |

| Other | 245 | 248.8 |

| Total | 324 | 367.4 |

Beyond supplying similar levels of care, the two countries also administered this care in parallel ways. Both Sweden and Norway tasked their counties with administering the medical arm of mental health services, while their municipalities addressed the social arm (e.g., housing, employment support, daytime assistance). Centralized public financing paid for the medical arm of services and municipal taxes financed the social arm.Footnote 2 As for private mental health care, a combination of patient fees and social insurance funds financed the few private services that existed in each of these countries.

When each country set out to reform mental health provision in the early 1990s, their aims were similar too. As in other countries, the advent of antipsychotic medications and critiques of the psychiatric hospital (and professional discipline) had spurred public support for deinstitutionalization (Diseth Reference Diseth2017; Ohlsson Reference Ohlsson2008). Economic constraints also motivated deinstitutionalization in Scandinavia – especially in Sweden, which faced a more severe financial crisis than Norway at the time. Norway would both recover from its crisis more quickly and, around a decade later, benefit from significant oil revenues. I will explore the longer-term impact of these additional resources in greater detail later in this chapter, but at the onset of the two reforms, policy-makers in both countries sought to rationalize mental health expenditures by deinstitutionalizing the mentally ill in similar ways. They embraced the same “sectorization” idea developed in France and attempted in the United States.Footnote 3 Under this idea, people with mental illness would not usually reside in a hospital; they would receive a comprehensive range of medical outpatient, inpatient, and social care services. To provide these services, governments would assign multidisciplinary teams of mental health professionals to a specific geographic catchment area, rendering them jointly responsible for persons living within that area.

The Swedish/Norwegian divergence in public mental health care is surprising for several other reasons. By their initial similarities and eventual differences, these shadow cases can control for alternative explanations for the divergence in US and French deinstitutionalization trajectories.

Consider first the legacy of state welfare provision. Like France, these Scandinavian societies have a large public sector, which they frequently deploy to provide generous health and social services. In fact, these universalistic, egalitarian, social democratic welfare states are usually even more generous than “conservative” France, which often stratifies benefits by social group (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990). Moreover, the private sector tends to play a more important role in French social welfare, especially its health system, than in Scandinavia. But just as this legacy cannot fully account for the mental health policy outcomes observed in France, neither can it explain those in Scandinavia, for Sweden substantially reduced provision in this area in the 1990s.

Second, consider the question of racial and ethnic diversity, an alternative explanation that emerged in the US case. For most of Sweden and Norway’s histories, racial, ethnic, or even religious diversity have not been political flashpoints.Footnote 4 Twenty-first-century measures of social fractionalization affirm the perception of cultural homogeneity. According to Alesina and colleagues’ influential 2003 index, the probability that two randomly selected individuals belonged to different ethnic groups was just 6 percent in both countries (Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat and Wacziarg2003).Footnote 5 Whether in Norway or Sweden, questions of racial and ethnic diversity have not historically cleaved redistributive politics like in the United States, or even France for that matter (notwithstanding the long-standing importance of their Sámi, Romani, and Finnish-speaking populations, especially in Sweden).

More recently, Norway and Sweden have placed a broadly similar emphasis on multiculturalism and protecting the human rights of international refugees, and this has shaped several waves of immigration in both countries (Brochmann Reference Brochmann, Nedergaard and Wivel2018). These groups have included refugees from, for example, the Balkans in the 1990s and the Middle East in the early 2000s. Of the two countries, Sweden has experienced higher rates of migration. Observers of its recent electoral outcomes may wonder if the rise in immigration has reduced social solidarity or increased racial-ethnic animus. Yet scholars emphasize that the political influence of the Radical Right was late and limited in Sweden relative to its Nordic and other West European counterparts (Brochmann Reference Brochmann, Nedergaard and Wivel2018). Perhaps as a result, and most notably, Sweden’s welfare state appears to be especially inclusive of immigrants (Boräng Reference Boräng2018; Sainsbury Reference Sainsbury2012). Compared to the United States, Sweden puzzles again. Historically, Sweden did not suffer from the same ethnic, racial, or social fragmentation; nor has its recent rise in immigration fractured its generous welfare state. Yet it too has struggled to provide expansive public mental health services to its population.

Third, the unitary states of Sweden and Norway have enabled both their statist approach to welfare and their national unity. This stands in stark contrast to the United States, where a highly fragmented federal system has made it difficult to develop generous national social policy, including in mental health. The comparison also controls for the possible effect of federalism on policy outcomes. As we will see, the otherwise unitary Sweden did experience a wave of administrative decentralization around the time of the mental health care reforms. Moreover, the country’s historic emphasis on local government is conceptually like that of the United States – if not in intensity. Nonetheless, I will discuss this parallel in more detail at the end of the chapter and explore whether and how it may have contributed to policy outcomes in Sweden.

Underpinning the social solidarity of Sweden and Norway, too, are their powerful labor and Left political movements, a fourth alternative explanation that emerges from the French case. But this explanation seems unrelated to mental health care outcomes in Scandinavia, where in fact Sweden’s union density (69 percent) is even higher than that of Norway (51 percent) (Kjellberg and Nergaard Reference Kjellberg and Nergaard2022). Membership rates are more comparable, though also greater, in the public sector: About 70 percent of blue-collar government workers are unionized, as are just over 80 percent among white-collar government workers in both Sweden and Norway (Kjellberg and Nergaard Reference Kjellberg and Nergaard2022). These workers play an important role in their countries’ political economies. Centralized collective bargaining institutions remain anchors of the Swedish and Norwegian economies. Although parts of the industrial relations systems have decentralized for private sector workers, wages for public employees are set at the national level (with some limited local wage-setting in Sweden; Andersen et al. Reference Andersen, Ibsen, Alsos, Nergaard, Sauramo, van Gyes and Schulten2015, 148). Moreover, the demands of government employees are often pivotal to national economic negotiations and, increasingly, to party politics. Historically, the Social Democratic party family – Scandinavia’s most important – has depended on a powerful labor movement to propel its long-standing success (Hansen Reference Hansen, Nedergaard and Wivel2018, 93). As the public sector has expanded, so too has the Social Democrats’ reliance on those employed by it. The usual political-economic influence of the Scandinavian welfare workforce, though, cannot on its own explain the supply of mental health care services, as that of Sweden is now less than that of Norway.

Fifth, the reforms in Sweden and Norway occurred in the 1990s, when the management of public mental health services was no longer as tied to the psychiatric profession as it tended to be in the 1970s and 1980s. In both France and the United States, the public managers that oversaw the mental health reforms in their countries were represented by psychiatric associations. To what extent was their influence a function of their medical, and not managerial, identities? The Swedish–Norwegian comparison controls for this alternative explanation because, by the time of their reforms, the managers of public mental health services were not represented by psychiatric associations. In fact, the Swedish Psychiatric Association has publicly and repeatedly deplored its deliberate exclusion from the reforms, while its Norwegian counterpart has claimed only limited involvement (Åsberg to Sandlund 1989 in Riksarkivet 1/1; SPF 1992; interviews with former presidents of both associations). Public mental health managers instead were represented by the associations of county and municipal governments, also known as the largest “employer” associations in Scandinavia. In Norway, the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (Kommunenes Sentralforbund, or KS) represents both county and municipal managers. A similar organization represents these two groups in Sweden as of 2022, but at the time of the reforms they had separate representatives: the Swedish Association of Municipalities (Svenska Kommunförbundet) and the County Council Association (Landstingsförbundet), respectively. This difference was an important one: Although the key managerial representatives in both countries did not double as psychiatric associations, the fragmentation of public managers’ representation in Sweden did contribute to the fragmentation of the welfare workforce, as will be shown.

Given that both countries shared these five initial similarities, why is it that their public mental health care systems eventually diverged? I next examine whether public labor–management coalitions shaped these outcomes. A “method of difference” approach (Mill Reference Mill1874) allows me to search primarily for the presence or absence of this variable (rather than its mechanistic relationship to the outcome, as in the within-case process analyses of Chapters 4 and 5).

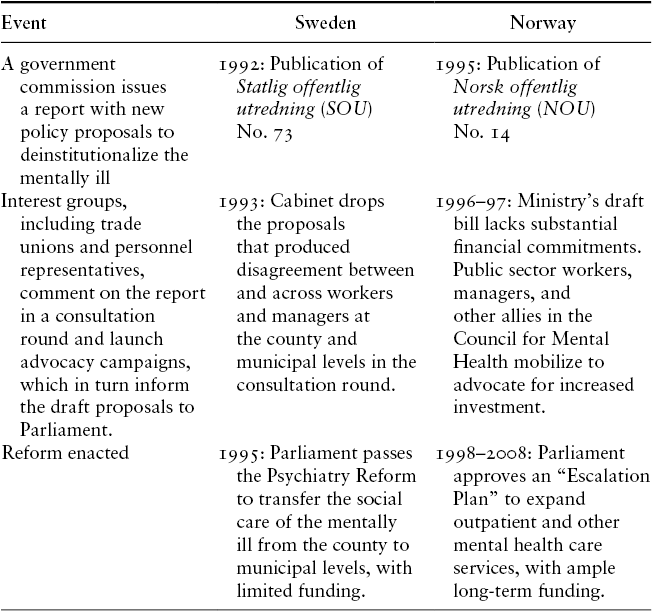

To ensure a comprehensive and parallel survey of the two reforms, I adopt a highly structured empirical strategy, aided by professional translation software and four native Scandinavian-language speakers. We conducted a full review of the secondary literature on Swedish and Norwegian deinstitutionalization, followed by a close reading of the main primary sources that produced each set of reforms: a major governmental report (and any adjacent, minor reports), a set of parliamentary proposals and the subsequent parliamentary debates, and the law that eventually passed. For a guide to these events, see the timelines in Table 6.4.

Table 6.4 Timeline of mental health reform process in Sweden and Norway in the 1990s, with main findings

| Event | Sweden | Norway |

|---|---|---|

| A government commission issues a report with new policy proposals to deinstitutionalize the mentally ill | 1992: Publication of Statlig offentlig utredning (SOU) No. 73 | 1995: Publication of Norsk offentlig utredning (NOU) No. 14 |

| Interest groups, including trade unions and personnel representatives, comment on the report in a consultation round and launch advocacy campaigns, which in turn inform the draft proposals to Parliament. | 1993: Cabinet drops the proposals that produced disagreement between and across workers and managers at the county and municipal levels in the consultation round. | 1996–97: Ministry’s draft bill lacks substantial financial commitments. Public sector workers, managers, and other allies in the Council for Mental Health mobilize to advocate for increased investment. |

| Reform enacted | 1995: Parliament passes the Psychiatry Reform to transfer the social care of the mentally ill from the county to municipal levels, with limited funding. | 1998–2008: Parliament approves an “Escalation Plan” to expand outpatient and other mental health care services, with ample long-term funding. |

To understand the role of trade unions, managerial associations, and other interest groups in these reforms, we read the meeting minutes and correspondence of the committee that produced the Swedish government report, as well as the consultation round documents (remisser). At the time of writing, these documents were not available for the Norwegian report; so we compensated by interviewing four of its authors and using the “snowball” method to identify two major interest group representatives from the Council for Mental Health (Rådet for psykisk helse; on the method, see Mosley Reference Mosley2013). We also interviewed one author of the Swedish report. Furthermore, we interviewed mental health policy experts in each of the two countries (five in Norway, four in Sweden) and the appropriate heads of the Psychiatric Associations (in Sweden, the president of the Swedish Association at the time of the reform; though, in Norway, only her counterpart’s predecessor was available).Footnote 6 To redress interviewees’ possible memory bias, we corroborated what we learned in interviews with the primary text sources just described, scanned Norwegian and Swedish newspapers for additional information, and then noted in the case studies where this possibility might affect the recounting of events. Last but not least, we engaged in a wide range of informal conversations and email correspondence with colleagues, librarians, archivists, and other experts during four months of field research in Scandinavia.

Negative Supply-Side Policy Feedback in Sweden

As in other countries, psychiatric deinstitutionalization had begun in Sweden during the postwar period; but the fiscal strain encountered later in the 20th century prompted the government to speed up the process (Markström Reference Markström, Brunt, Bejerholm, Markström and Hansson2020; Silfverheim and Steffason 2006). In fact, the cost of care in the large county mental hospitals – many of which could host 1,000 patients – had grown more than any other area of health care in the late 1980s (Lindqvist Reference Lindqvist2012). These economic realities, combined with the generalized support for outpatient-oriented psychiatry, prompted the then Minister of Health and Social Affairs, Social Democrat Sven Hulterström, to appoint a Commission of Inquiry in 1989. Its task was to evaluate the mental health care system and formally propose new measures to improve its “efficiency” in an “SOU” report (Statlig offentlig utredning, or Swedish Government Official Report).Footnote 7 This initiative launched the policy-making process that produced the 1995 Psychiatry Reform, with its subsequently negative supply-side policy feedback loop (and ensuing reinforcement over time). This section documents that loop (depicted in Figure 6.3). The absence of a public labor–management coalition first enabled the 1995 Reform and its limited financial support for mental health care (the “feed”), a policy result that in turn further constrained possibilities for workforce advocacy and service expansion (the “back”).

Figure 6.3 Negative supply-side policy feedback in Swedish mental health care, 1992–97

I begin by identifying which reforms the Commission proposed in its 1992 SOU, how the representatives of the welfare workforce viewed each of them during the consultation period, and what the 1993 right-wing Cabinet subsequently proposed to Parliament. Parliament then passed the proposals with little disagreement and authorized their implementation in 1995. In consensus-oriented Sweden, the responses of interest groups to an Inquiry report directly inform the Cabinet’s proposals to Parliament (Petersson Reference Petersson and Pierre2016). As such, none of the Commission’s proposals that produced disagreements between and across labor and management made it to the Cabinet’s Propositions. Only one area – where public sector workers and their managers aligned – did. The result was a reform for public mental health care with very limited financial backing.

Consider the results of the three major policy proposals on which managers and workers disagreed. We can begin with the most consequential one: the Commission’s proposal to formally devolve social services for the mentally ill to the municipalities. To reduce the number of patients living in mental hospitals at the county level, it proposed decentralizing their “custodial” functions to the municipal level (see Chapter 2 and the Appendix). In theory, the municipalities had received this responsibility more than a decade prior under the 1980 Municipal Social Services Act, but in reality few had developed substantial social services for the mentally ill. The Commission proposed to incentivize municipalities to expand social services over a three-year implementation process: First, municipalities would assume the financial responsibility for patients residing in county mental hospitals for more than six months, with the help of an intragovernmental shift of tax credits. This move would allow the municipalities to develop alternative, nonmedical, and hence less expensive social supports, such that, later, municipalities could assume the financial responsibility for all patients discharged from county mental hospitals (SOU 1992:73, 32–33).

Although there was broad consensus about reinforcing the 1980 Municipal Social Services Act, workers and managers at different levels of government disagreed sharply on the specifics of implementation. The six-month residence cut-off was a particularly sensitive flashpoint, in part because of the ideological tension between health professionals and non-health professionals, who argued over whether to require a medical assessment for discharge and whether the cut-off should be shortened to one month.Footnote 8

The question with longer-term consequences was whether the counties should relinquish outpatient mental health services to the municipalities, which in principle only had responsibility over nonmedical social services. If the goal was to deinstitutionalize the mentally ill, municipal-level managers and social care workers argued, they should have “primary responsibility” over the full range of services that would support their lives in the community. Such were the preferences of the Municipal Employers Association (Svenska Kommunförbundet), the Municipal Heads of Social of Services (Foreningen sveriges socialchefer), and the Municipal Employees Union (Sveriges kommunaltjänstemannaförbund, or SKTF). On the other hand, the County Employers’ Association (Landstingsförbundet) and county-employed health care staff (such as the Swedish Medical Association) advocated forcefully to retain county control of medical services.Footnote 9

In response, the Cabinet simply reproduced the status quo. Note that both the politicians and civil servants on the Commission seemed to sympathize with the municipalities. In a 1991 letter to the Health Minister, the Commission’s parliamentary representative, Bo Holmberg, and a lead civil servant authoring the report, Gert Knuttson, argued that the recent changes to elderly care policy made it possible to task the municipalities with more control over the medical aspects of mental health.Footnote 10 Nonetheless, the welfare workforce remained split. Although public labor–management coalitions existed at both the municipal and county level, the two groups stood in opposition to each other. Parliament approved, reinforcing the social service responsibilities of the municipalities and the health service responsibility of the counties.Footnote 11 This decision would further exacerbate the fragmentation of the welfare workforce, with consequences for the long-term supply of mental health care.

A second issue was how much money to allocate to the reform, and through which entities. Here the divide was similar to that of the “primary responsibility” debate. The Municipal Employers Association, the Municipal Heads of Social Services, and the Municipal Employees Union (SKTF) advocated for additional financial support to municipal social services, while the County Employers’ Association and medical staff advocated for more financing at the county level (SOU 1992:73, 495–510; Ds 1993:88, chap. 9). Note that some workers raised concerns about this fragmentation. The SKTF, in a strongly worded letter to the Ministry of Social Affairs, warned about carrying out the reform “with totally inadequate resources and without adequate planning and cooperation between administrators and the various staff groups concerned” (Sture to Petterson in Riksarkivet 1/4). But such warnings would have little effect on public policy.

Noting these conflicts and the emergence of similar ones in other decentralizing policy areas, the Cabinet instead opted to delay their resolution, setting up a parliamentary committee to “find a solution with broad support in the world of local government” (referring to both counties and municipalities; Prop 1993/94: 218, sec. 6.5). Setting aside the structural fiscal questions that would increase funding to either counties or municipalities (or both), the government instead offered a short-term implementation grant of 1.2 billion SEK (or about $200 million contemporary USD), to be paid between 1995 and 1997 (Prop 1993/94: 218, 3). That limited funding would soon make it difficult to expand and develop mental health care.

In a third controversial proposal, the Commission sought to grant people with mental illnesses the legal right to demand services from counties and municipalities by attaching that right to a recent bill passed for people with physical disabilities, the 1992 “LSS.”Footnote 12 Here the positions of public managers, at both county and municipal levels, differed from the health and social care unions that represented their employees. The Municipal Employers Association, the Municipal Heads of Social of Services, and the County Employers Association worried that the “increased social costs” and “economic effects” would be too high if the mentally ill gained this right (Ds 1993:88, 50). Indeed, if the administrative court ruled in a mentally ill person’s favor, counties and municipalities would be legally obligated to provide them with the requested services. Meanwhile, workers (including the Swedish Medical Association) generally supported the Commission’s proposal; the demands of the mentally ill would likely expand their opportunities for work (Ds 1993:88, 52, 36). Unions that represented blue-collar and social workers, those most likely to benefit from this policy change, even favored expanding the benefits’ eligibility rules to broaden the scope of potential clients (see LO and SKAF comments in Ds 1993:88, 52). Taking explicit note of these divisions (Prop 1993/94: 218, sec. 5.3–4), the Cabinet took what Urban Markström refers to as a “wait-and-see” approach (Markström Reference Markström2003, chap. 6). Leveraging rifts in the welfare workforce to avoid public spending increases, the Cabinet claimed it needed “more accurate information on the scope of the law and its financial implications” (Prop 1993/94: 218, 28). As a result, the mentally ill did not gain the legal right to demand services in 1995.

Managers and workers, though, did agree on something: “personal assistants.” The broad support for trialing this new occupational group provides a useful counterfactual. The Cabinet indeed was willing to allocate resources to policies jointly supported by both managers and workers. A concept inspired by the Anglo-American case worker, the personal assistant would offer individualized support to persons with mental illness. That some observers critiqued the idea as a foreign import seemed to make little difference to the welfare workforce (Maycraft Kall Reference Maycraft Kall2010; Ds 1993:88, 58). If enacted with financial support, the personal assistants’ scheme could bring new members to the unions and new funds to employers. The details were vague. Workers and managers wondered about the skill level, legal status, and of course appropriate employer of the personal assistant. In principle the assistants would be employed at the municipal level, though several unions were quick to note that workers at both levels of government, such as county-employed allied health professionals or nurses, could take on this new role as well (Ds 1993:88, 52). The potential flexibility of the personal assistant may have been its selling point to a broad spectrum of workers and managers across levels of government. Responding in the affirmative to their united stance, the government proposition enacted the scheme with a three-year trial period and its own, separate funding to “stimulate [the program’s] development” (Prop 1993/94: 218, sec. 5.3). Furthermore, according to a lead author of the SOU, “the government actually gave more money than we could think of!” Not only did politicians concede to reforms supported by both workers and managers, but it also seems that they did so generously.Footnote 13

Overall, however, the fragmentation of the welfare workforce allowed the 1995 Reform to both restrict the funds available for mental health care expansion and exacerbate existing political divisions. As a result, negative returns to services and the workforce played out over the next decades (part two of the feedback loop). In fact, studies of the 1995 Reform’s implementation suggest that it was difficult for the welfare workforce to unite in favor of expanding services. Among the greatest challenges was that managers and workers could not plan ahead: The temporary grant program provided no long-term funding guarantees, rendering it difficult to hire new personnel or establish a durable operations program. When funding limitations resulted in staff cuts, furthermore, quality of care suffered (see Tidemalm’s 1996 and 2000 studies of a group housing program in Markström Reference Markström2003, chap. 7). The lack of financial security in this policy area thus facilitated those cuts and offered managers and workers few opportunities to redress them.

Not only were workers bereft of generous and secure funding; it also became more challenging to identify to whom they should express their grievances. Confusion was especially rife at the municipal level, since the Reform provided very little guidance on how to develop new social services for the mentally ill, an approach that Wendy Maycraft Kall’s (Reference Maycraft Kall2010) study referred to as central government’s “soft steering” of local policy. As a result, municipalities developed a myriad of approaches to organizing services for the mentally ill. The “managers” of these services, Markström (Reference Markström2003, chap. 8) found, could range from the Municipal Head of Social Services, to a “psychiatric coordinator,” to the director of a service primarily targeted at another client group (such as those with physical impairments). That the political representation of each of these administrators varied, moreover, made it even more difficult for unions to identify potential coalition partners.Footnote 14 Sentiments like this one, uttered by one of his interviewees, aptly captures the confusion of workers: “They have an awful lot of managers … in social services: middle managers and assistant managers and coordinators. It seems to be difficult, you don’t know which manager to go to and who does what” (staff member at a residence support group for people with mental illness, Markström Reference Markström2003, chap. 8, 12). The Reform’s soft steering contributed to the increasing fragmentation and complexity of the management hierarchy, obscuring the coalition possibilities for workers. Moreover, the limited agitation from workers appears to have contributed to what Markström (Reference Markström2003, chap. 8) called managers’ overall “passive” approach to the Reform’s implementation. They had little incentive to take up the funds and expand services.

More generally, the Reform deepened the divide between county-level employers and health workers on the one hand and municipal-level employers and social care workers on the other. Disagreements about whether and how much to allocate to each level of government for the care of the mentally ill continued in the years following its enactment. County-level medical staff have little in common with municipal-level social care staff. What is more, there is a sharp professional divide. Consider what occurred when county-level mental hospitals closed and transferred some former staff to municipal social service employment (often against their will). Numerous studies documented how these workers felt out of place, even devalued, in their new positions and had difficulty finding common ground with employees of other social care institutions (see Johansson and Westin 1997 cited in Markström Reference Markström2003, chap. 7). The de-professionalization of parts of the psychiatric workforce, furthermore, may have weakened the workforce’s political strength. This will stand in sharp contrast with the Norwegian approach discussed in the next section, where significant upskilling took place. Indeed, by de-professionalizing and fragmenting the Swedish welfare workforce, no coalition could successfully advocate for more funding for mental health care from Parliament, reinforcing the negative feedback loop (see Figure 6.3).

Nonetheless, it is worth noting the few local examples where services did expand: In areas where mental health care workers were powerful, managers were keen to ally with them, and the coalition could depend on alternative, and more secure, funding streams. Indeed, the most “ambitious” municipalities tended to be “mental hospital towns,” that is, towns where psychiatric services, and by extension staff, were already present (Markström Reference Markström2003, chap. 2; Markström and Lindqvist Reference Markström and Lindqvist2015). One can infer that the high density of psychiatric employees would have increased the political pressure to expand services in these municipalities after the Reform. Markström (Reference Markström2003) also found ample evidence that the coordination and coalition-building efforts of local management (across both county-level health care and municipal-level social services) contributed to service expansion as well. Due to the ample structural and organizational setbacks in the area, though, these “moral entrepreneurs” often built these coalitions out of sheer goodwill rather than personal self-interest (Markström Reference Markström2019; 2003, chap. 2).

The services best suited to expansion, moreover, were those that could draw on other, more secure financing streams and fewer staff, such as sheltered housing units, or those that had obtained financial support due to an alliance between managers and workers in the first place, such as the personal assistants’ scheme (Markström Reference Markström2003). Even still, only about 60 sheltered housing projects were launched in Sweden as a result of the Reform (in fact the stimulus grant was never even fully used) and the personal assistants’ scheme has experienced only limited growth (Markström Reference Markström2003, chaps. 7–8).

Positive Supply-Side Policy Feedback in Norway

From one standpoint, the genesis of the Norwegian mental health reforms is virtually identical to that of Sweden: A 1995 NOU report (Norsk offentlig utredning, or Norwegian Government Official Report) evaluated the expensive, county-based long-term care system and proposed new policies aimed at reorienting the system toward community-based outpatient and social care services with the help of municipal governments.Footnote 15 Although the NOU included a review of care for the elderly and disabled, significant attention was also paid to the mentally ill. To accommodate the overflow of patients in mental hospitals, Norway had established the aforementioned “psychiatric nursing homes” in the 1970s to house patients with severe and chronic mental illness over the long term, such that by 1990 these institutions had become de facto asylums. The NOU hence proposed repurposing these institutions as outpatient-oriented services, namely “district psychiatry centers,” a concept in fact inspired by the US community mental health centers (NOU 1995: 14, 58–60; interview with the Norwegian civil servant responsible for overseeing mental health financing at the time of the reform).

On the other hand, the strength and unity of the welfare workforce prior to the 1995 NOU report presents a strong contrast to the case of Sweden. Potent advocacy from public sector workers, managers, and their allies was already underway well before the 1995 report went to press. In 1992, the Norwegian public broadcaster NRK (Norsk rikskringkasting) selected the Council for Mental Health – an advocacy group composed of representatives from numerous organizations, including trade unions and professional associations – as its partner in its annual fundraising telethon, TV-aksjonen. Known as the world’s largest fundraising campaign, Norway’s telethon highlights the work of a chosen nongovernmental organization while collecting voluntary public donations for the cause. Although the Council had begun as a research organization in 1985, it drew on the 90 million NOK (over $20 million contemporary USD; per Norges Bank 2023b; OECD 2023) collected from the 1992 civic campaign to complete its transformation into a political lobby. Over the following years, the Council and its members held conferences throughout the country to raise awareness of mental health issues. Crucially, these conferences brought together mental health professionals, their trade union representatives, local administrators and managers, as well as patients and parliamentarians. The combination was potent. Patient stories drew heavy media coverage, while members of Parliament developed closer ties and commitments to the mental health care workforce in their local districts. The Council had thrown mental health into the spotlight while rendering electorally minded politicians accountable to this policy area.Footnote 16

These two factors came together in 1995, producing the first part of a positive supply-side policy feedback loop (see Figure 6.4). The Council – by then, well-resourced both financially and politically – sprang into action upon the NOU’s publication. Its unity was its greatest strength. Although its members did not always agree on policy, the Council required the internal resolution of these debates before expressing a shared preference to the authorities. In the words of its former Secretary General, this protocol allowed the group to have a “clearer and more precise influence” on the reform process.

Figure 6.4 Positive supply-side policy feedback in Norwegian mental health care, 1995–2008

The same quote could describe the organization representing both municipalities and county administrators (KS). In contrast to their counterparts in Sweden, managers at both these levels of government organized together. This organizational structure promoted the joint expression of policy preferences and headed off any fragmentation. Note also that the KS did not formally join the Council for Mental Health. In some ways, the relationship between the KS and the Council resembled that of traditional industrial relations, with managers (KS) on the one side and workers (the Council) on the other side of the negotiating table.Footnote 17 Because only one organization spoke for each end (all public managers and all their employees, respectively), agreements between them were universally beneficial to public employees across all levels of government and types of occupations.

When the Ministry published its proposals to Parliament in 1996–7, the Council continued its pressure, particularly regarding the need for funding, a question that the Ministry had effectively ignored.Footnote 18 Although Norway’s financial crisis was less severe than Sweden’s at the time, its bureaucrats were no more keen to devote significant resources to the reform. The proposals, while in line with the joint preferences of managers and workers, lacked substantial financial commitments. In fact, at the press conference announcing the reform proposals, the then Chair of the Council exclaimed, “But where is the money?!” – a pointed line that has become among the most memorable and repeated by those in attendance.Footnote 19 In response, the Council, its members, and allies in the Ministry undertook a second round of intensive advocacy. Another tour of conferences around the country, combined with active parliamentary lobbying, pressured politicians to both accept the proposals and commit considerable funds to them. “This is the most discussed [Ministerial proposal] ever,” its lead author purportedly exclaimed (interview with former Chair of the Council for Mental Health).

The coalition produced astounding results. The proposals for the usually small and politically insignificant issue of mental health care reform gained unanimous support in Parliament, which publicly commended “the Council for Mental Health and its important work” in the enactment process.Footnote 20 Moreover, the conservative Parliament berated the Ministry for not providing enough funds in its original proposal and pressed for redress:

The [Parliament’s Social Welfare] Committee believes that increased earmarked funding for mental health care will be necessary for many years to come … [and] would like to point out that the [Ministry’s proposal] does not contain calculations and figures that can give a sufficient basis for estimating how much money to allocate to psychiatry in the coming years … A major effort must now be made for people with mental disorders … The Committee requests that a binding action plan for psychiatry be prepared that includes … a financially binding escalation plan for the earmarked subsidy.Footnote 21

With this strong and urgent language, the politicians moved to earmark a whopping 24 billion NOK (about $5 billion contemporary USD) for the project to spend over the following eight years.Footnote 22 Counties would decrease the resident populations of their long-term mental health care institutions while both counties and municipalities would increase the provision of community-based alternatives. While municipalities gained significant financial support to expand social services (like their counterparts in Sweden, though with far more funding), Norwegian counties also gained financially; they would implement the district psychiatry centers. The earmarked funds also supported the hiring and upskilling of personnel. This move gave trade unions a pipeline of potential new members and even direct financial support, for they often administered the new training programs (interview with Norwegian civil servant mental health financing expert).

The result was the positive second part of the feedback loop (see Figure 6.4). The presence of a robust public labor–management coalition helped to ensure the implementation of the “Escalation Plan” over the following decade (the coalition also managed to extend the project by two years). Counties, municipalities, and their employees only received financing for service expansion if and when they submitted an implementation plan, which included the requisite set of services and staff. Although some managers complained about these firm requirements, in general the mental health workforce was keen to accept the new earmarked funds.Footnote 23 Moreover, the Council for Mental Health and its allies acted as implementation watchdogs. As the Council’s former Secretary General put it, the organization would “highlight whether the authorities actually granted what they were supposed to and whether the municipalities actually used the earmarked funds for what they were required to do.”Footnote 24 Of particular note was the Council’s advocacy for the expansion of new mental health resources and positions. Although some municipalities preferred to simply convert preexisting health and social care facilities and staff into resources for the mental health sector, the Council instead advocated for more facilities and more staff.

The result of this coalition and the policy feedback loop it facilitated was the production of the policy outcomes in Table 6.1. Even as psychiatric nursing homes were downsized, the number of district psychiatry centers increased, as did their staff. By the end of the Escalation Plan, supply-side policy feedback had increased total staffing in mental health by 20 percent (Romøren Reference Romøren, Hatland, Kuhnle and Romøren2018). The positive feedback, furthermore, appears to have continued. Norwegian public policy stipulates that the State must spend more on mental health care than somatic care, and as of 2023 a new Escalation Plan is underway at the Ministry.Footnote 25

Discussion and Conclusion

The absence of consensus between (and across) public sector managers and workers in Swedish mental health care facilitated negative supply-side policy feedback during the 1990s. In contrast, a forceful, formally organized coalition enabled positive supply-side policy feedback in Norwegian mental health care. In each case, I have traced a single loop launched in the 1990s, in contrast to the previous chapters on the United States and France, where three respective feedback cycles gradually reinforced contrasting patterns of deinstitutionalization. The results of the 1990s may have positioned Swedish and Norwegian mental health care policy and staff to experience several more self-reinforcing feedback cycles in the future as well, though the argument of this book does not aim to be deterministic. Theoretically, a coalition of managers and workers could emerge in Sweden and disappear in Norway. Nonetheless, contemporary levels of mental health care supply in the two countries (as well as the political momentum behind launching a second Escalation Plan in Norway) suggest a pattern of continued reinforcement since the 1990s, such that their diverging policy results have endured.

Although these two countries share much in common, readers familiar with their differences might wonder about whether and how three of these differences could have shaped these politics. To conclude this chapter, I consider whether and how contemporaneous differences between Sweden and Norway’s economic crises and right-wing governments may have shaped mental health care reform in either case. I also examine the effect of Sweden’s greater emphasis on decentralization. To be sure, this shadow “most similar systems” comparison does not allow for a fine-grained assessment of case-specific alternative hypotheses; but it is nonetheless important to briefly consider a few pertinent questions.

First, and perhaps most importantly, did Sweden’s deeper economic downturns render retrenchment more likely than in Norway? Conversely, did Norway’s access to oil revenues over-determine the expansion of public mental health services in that country? Although both countries experienced banking crises in the 1990s, between 1990 and 1993 average loss provisions amounted to 4.8 percent in Sweden, compared to 2.7 percent in Norway (Honkapohja Reference Honkapohja2009, 10). Not only did Sweden face greater financial pain but it also commenced its reforms precisely at that time. Norway, on the other hand, waited until the worst of the downturn had passed to reform (and expand) public mental health care. Moreover, the growth rate of the Norwegian oil fund escalated significantly in the following decade, as the Escalation Plan was underway. Technical quibbles notwithstanding (Norway’s recovery was slow, and in fact current accounts had fallen when the Escalation Plan passed), fiscal pressures were objectively greater in Sweden than in Norway at the onset of the reform. Later, during implementation, Norway would benefit from a wellspring of funds.

Recall that in Norway, however, the Ministry’s civil servants did not make financial requests of Parliament in their original proposal (1996–97 St meld 25). Yet elected politicians ultimately allocated a conspicuous amount of funding – far beyond what might have been expected at the time – to implementation (1996–97 Innst. S. 258; 1997–98 St prp 63). What occurred between these two steps? As any observer of economic inequality would note, politicians in resource-rich countries do not always choose to distribute that wealth to the needy. As the case study illustrates, the advocacy of the Council for Mental Health and its welfare workforce membership proved essential for motivating politicians to increase the size of those allocations. Had a consensus between managers and workers not existed in Norway, politicians may have been just as likely to use the economic crisis as an excuse to restrict their financial support for the reforms. Instead, they catapulted funding in this area. Certainly, after the reform passed, Norway’s increasing wealth helped to boost the funds available for the Escalation Plan, which no doubt helped to justify its two-year extension. But it is important to remember that politicians committed resources to mental health care before this windfall occurred.

Moreover, Sweden did devote significant resources to other social policy areas at this time. Major reforms to both the elderly care system and the disability care system occurred just before the mental health care reform, amounting to 5.5 billion and 1.6 billion SEK respectively (over $1 billion and about $300 million contemporary USD; Prop 1990/91:14 and Prop 1992/93:159; per OECD 2023; SCB 2023). The budgets allocated to these changes were much higher, perhaps in part because of their different constituencies. As in other countries, the interest groups representing older adults and people with physical disabilities tend to be more politically influential than those that represent people with mental disabilities, whose condition makes it especially difficult to mobilize. In addition, middle-class families are more likely to demand caregiving support for their older parents and, if to a lesser extent, relatives with physical disabilities than for their comparatively fewer relatives with severe psychiatric needs. Sweden allocated more funding to reforms in these two other areas than in mental health, both during the crisis and after it. Even as the economy picked up again in the late 1990s, far fewer resources were distributed to mental health care than to elderly care or disability support. By then, the negative feedback loop in mental health care had established itself in ways that continued to weaken this sector relative to other social policy areas.

If one steps back to compare the financial commitments in both cases, furthermore, the sheer magnitude of the difference in scale between them stands out (Table 6.1). In effect, Norway committed to spending over tenfold more per capita per year than Sweden, and for four times as long. These outcomes are strikingly divergent: Sweden spent far less than one might expect from a country with generous public service provision and Norway spent far more on a policy area that rarely receives substantial financial resources. It is difficult to explain these differences without attending to the politics that produced them.

A second alternative explanation accordingly considers the effects of political partisanship: Did the right-wing government and policy priorities of early 1990s Sweden bias outcomes in that country? The general elections of 1991 had dealt a serious blow to the long-standing dominance of the Social Democrats, generating a liberal-conservative Cabinet committed to fiscal restraint and marketization. The Cabinet sought to introduce these changes to a range of social welfare and public service areas, notably including care for the elderly and disabled. In some ways, the reforms in mental health care aligned well with these aims (even though the Ädel reforms may have received more financial and political attention).

The government that passed the Norwegian Escalation Plan was also a government of the Right, but of a very different character than Sweden’s at that time. The Norwegian elections of 1997 had brought Christian Democrats to power. Although this family of parties may prefer limited government, Christian Democrats stand out for their historic sympathies for the poor and marginalized (van Kersbergen Reference Kersbergen1995). As Rogers (Reference Rogers2022) has found, these sympathies extend to the mentally ill as well. Moreover, Norway’s Christian Democratic prime minister, Kjell Magne Bondevik, personally experienced and publicly acknowledged mental illness, so much so that in 1998 he took time away from office to recover from a depressive episode. One must nevertheless ask whether the Norwegian Christian Democrats would have allocated quite so much financial support to mental health care absent the advocacy of the public labor–management coalition.Footnote 26 This political party typically prefers to deliver social services through nongovernment, church, and family institutions, rather than the state (van Kersbergen Reference Kersbergen1995). More broadly, the reforms were timed with overall right-wing partisanship, a variable that cross-national studies associate with cuts, not expansions, to social spending (e.g., Huber and Stephens Reference Huber and Stephens2000).

Third, what role does decentralization play? Norway’s more centralized polity, for instance, appears to have helped unite its welfare workforce. Although both countries have unitary states, Sweden’s historic emphasis on local self-government – and its rise in the 1990s – renders public policy there somewhat less centralized than in Norway (Laegrid Reference Laegrid, Nedergaard and Wivel2018). This difference appears to have fragmented Sweden’s public sector workforce in the 1990s, contributing to the negative supply-side policy feedback process. A closer look at the impact of decentralization in Sweden and (more) centralization in Norway underscores several theoretical points discussed in Chapter 1.

It underscores the importance of management qua management to supply-side policy feedback, even if (or especially because) the substantive content of managerial divisions can vary. Like their counterparts in the previous chapters on the United States and France, public sector managers in Sweden sought to clearly demarcate and protect their administrative territory. What is more, the fierce debates between municipal and county managers over who had “primary responsibility” over mental health care show that managerial divisions can appear within the public sector, not just between the public and private sectors. Unlike their counterparts in the previous chapters, however, public managers in Sweden did not seek to protect medical territory. They were not physicians. In fact, the administrative goals of psychiatrists were all but ignored (SPF 1992, sec. 4.2.2). Rather, the Swedish case demonstrates how public sector managers influence policy even without a medical degree, and in what ways they too can practice ring-fencing within the public sector itself. In brief, managers matter to supply-side policy feedback because they are managers, not because they are doctors wielding medical authority.

It underscores, furthermore, the importance of organizational form. While county and municipal managers organized together in Norway, they did not in Sweden until later (they have since joined forces). As in the French and American cases, different organizational forms produce different vehicles for preference expression, with different results. Forced to speak with one political voice, county and municipal managers in Norway likely came to agreement in ways not politically feasible for their Swedish counterparts. The same could be said of Norwegian workers employed by different levels of government and in different services, as their joint participation in the Council for Mental Health also facilitated consensus.Footnote 27

As such, it underscores that workers can also be divided, reinforcing divisions among public sector managers and producing multiple, ineffective public labor–management coalitions. Since counties employ health care workers and municipalities employ social care workers, the welfare workforce split along sectoral lines in two out of the four policy issues studied. The fact that county-level workers were higher-skill and physicians could not work at the municipal level only cemented this divide further. As a result, there were in fact two public labor–management coalitions over these issues (between social care workers and municipal managers and between health care staff and county managers). Neither coalition, though, was successful. A conventional labor–management split followed in the third issue; that too was unsuccessful. For positive supply-side policy feedback to take off, it seems, a single coalition of public managers and workers must be present, as was the case in the fourth policy issue.

Lastly, it underscores that institutional factors can shape the possibilities for coalition, though that cause need not be intentional nor its effect definitive. Sweden’s long tradition of local government notwithstanding, the government had only recently begun to decentralize in earnest. This changing and often foggy landscape both weakened incentives and challenged the efforts of workers and managers at county and municipal levels of government to coordinate. It is not evident that the state intended to fragment the welfare workforce in this way. Such a claim would require a more precise definition of the state and who within it had the (rare) foresight to carry out this plan. Just as important, however, is the fact that structural factors do not unequivocally determine coalitional possibilities. The mobilization efforts of the Council for Mental Health in Norway or the occasional local examples that emerged in Sweden, for instance, show the importance of human agency in producing the outcomes observed there. The alternative explanation of administrative decentralization, then, both complements and clarifies the primary argument presented in this book.

In conclusion, a shadow comparison of the contrasting public mental health care reforms in Sweden and Norway in the 1990s is supportive of my hypothesis. Despite the many similarities between the two countries, Sweden and Norway took opposite approaches when they formalized their deinstitutionalization policies, such that the supply of public mental health care decreased in Sweden and increased in Norway. A review of both primary and secondary sources points to a core difference between the two countries: the political alliances and strategies of the welfare workforce. Where public sector managers and workers in Sweden could not come to agreement on how to reform the mental health care system, unifying organizations in Norway brought them to consensus and amplified their advocacy efforts. The result was, as hypothesized, negative and positive supply-side policy feedback, respectively.

Feedback processes such as these, moreover, can shape policies far beyond those in mental health. In the following and final chapter of this book, I explore the implications of these findings for the welfare state, other public services, and indeed the macroeconomy as a whole. In so doing, it focuses on three key trends: the welfare state’s emphatic shift from cash transfers in the postwar period to social services in the late 20th century; the rise of public service employment, now a linchpin of the advanced economies; and a new distributional logic of welfare provision. Increasingly, it is public sector – not private sector – unions that shape social policy. The politics of psychiatric deinstitutionalization therefore offer a window into these trends, illuminating several key dimensions and raising questions for future research.