Introduction

Palliative care (PC) work involves absorption of negative emotional responses, breaking bad news, challenges to personal beliefs, coping with the inability to cure, immersion in emotional clashes, poorly defined roles, recurrent exposure to death, working in an area of uncertainty, patient suffering, and secondary trauma (Rokach, Reference Rokach2005; Breen et al., Reference Breen, O'Connor and Hewitt2014). Healthcare professionals in PC settings can face a range of challenging situations while emotional demands on staff can lead to poor psychological well-being (Martins Pereira et al., Reference Martins Pereira, Fonseca and Sofia Carvalho2012; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Dempster and Donnelly2016). Specifically, nurses working in PC have a demanding role, requiring time and continual contact with patients and caregivers who are suffering. The nature of this work, often involving prolonged contact with people during the end stages of serious illnesses, predisposes PC nurses to significant physical, emotional, spiritual, and psychological distress (Cross, Reference Cross2019).

Four systematic literature reviews have been conducted to date synthesizing available literature in the area of PC. Martins Pereira et al.'s (Reference Martins Pereira, Fonseca and Sofia Carvalho2011) review included 15 studies published between 1999 and 2009 and exploring burnout in PC staff. Their findings suggested that burnout levels in PC do not seem to be higher than in other health contexts. However, a limitation of this review is that most of the studies included were not from PC settings, and half were from staff working in oncology services. Similarly, Parola et al.'s (Reference Parola, Coelho, Cardoso, Sandgren and Apóstolo2017) review of the prevalence of burnout in PC professionals included eight cross-sectional studies with a variety of healthcare professionals, such as nurses, physicians, and social workers. Hill et al.'s (Reference Hill, Dempster and Donnelly2016) review included nine quantitative studies investigating psychosocial interventions to improve the well-being of staff who work in PC settings. They found no meaningful conclusions could be drawn about effective interventions for staff due to the poor quality of the research, furthermore, their study was undertaken with a range of participants (paid or voluntary) with no restrictions to any one profession (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Dempster and Donnelly2016). Finally, Zanatta et al.'s (Reference Zanatta, Maffoni and Giardini2020) review of six quantitative studies on resilience in healthcare professionals providing PC to adults, found resilience moderates and facilitates nurses' adaptation to death anxiety, traumatic experiences, stress, and burnout. Zanatta et al.'s review (Reference Zanatta, Maffoni and Giardini2020) proposed a theoretical model of resilience experience and suggested that further research was required to validate their findings.

There have been several recent systematic reviews undertaken in related areas. Dijxhoorn et al. (Reference Dijxhoorn, Brom and van der Linden2020) investigated interventions for burnout in healthcare professionals providing PC in various settings. Their meta-analysis of 59 studies found a wide range of burnout in various healthcare settings with lower rates in specialist services. They also highlighted that a greater understanding of burnout among healthcare professionals in PC was needed (Dijxhoorn et al., Reference Dijxhoorn, Brom and van der Linden2020). Lagentu et al. (Reference Lagentu, Eka and Tahulending2017) undertook a systematic literature review of burnout in PC nursing; however, their review only included four quantitative studies. Lastly, Powell et al.'s (Reference Powell, Froggatt and Giga2020) systematic literature review of eight qualitative and mixed-methods studies focused on the resilience in inpatient PC nurses. They suggested that research on developing a greater understanding of PC nursing staff experiences of stress and burnout from a qualitative perspective is missing (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Froggatt and Giga2020).

To date, most research on stress, anxiety, and burnout in PC has been with patients and families. Moreover, much of the research that has been undertaken with healthcare professionals has focused on psychological interventions, developing resilience, or the prevalence of common mental health issues. Where systematic reviews have been undertaken into nurses’ experiences in PC, these have mainly been done in home care settings (Sekse et al., Reference Sekse, Hunskår and Ellingsen2018). As such, this systematic literature review will address the question: “What are palliative care nurses’ experiences of stress, anxiety, and burnout?”.

Methodology

Literature search

The review was registered on the systematic review protocols in the international prospective register (PROSPERO; ID number CRD42020221645). Searches for studies that have investigated PC nurses’ experiences of stress, anxiety, and burnout were undertaken in December 2020. The databases used included PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PubMed, and Web of Science. The SPIDER tool was used to identify studies for inclusion in the review (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Booth and Leaviss2013) as it provides an organizing framework by which to list search terms and main concepts (Methley et al., Reference Methley, Campbell and Chew-Graham2014). The main concept terms, and synonyms, were searched for within titles, abstracts, keywords, and the main text of studies to increase the probability of identifying relevant research. The truncation operator “*” was also employed to avoid relevant search results being excluded due to minor word differences. An overview of search terms is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Key search terms

A Boolean search strategy was used, and each search performed using the following search terms: (“nurs*” or “healthcare professional” or “health personnel” or “staff”) AND (“palliative care” or “terminal care” or “end of life”) AND (“stress” or “anxiety” or “burnout” or “vicarious trauma” or “compassion burnout” or “anticipatory grief”) AND (“questionnaire” or “survey” or “interview” or “focus group” or “case study” or “observational study”) AND (“perception*” or “coping”) AND (“qualitative” or “mixed methods”).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

An overview of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they were published in the English language, focused on the experience of stress, anxiety, or burnout and had nurses working in PC settings as participants. Also included were qualitative research, or mixed-methods studies where qualitative data were extractable. No limits were placed on study sample size, recruitment method, or date of publication. Initial screening of study titles and abstracts against inclusion and exclusion criteria was completed by both the lead researcher and a co-author. Relevant studies were retained, and the full text of each study was then screened independently by both the main author and the co-author. Any differences were managed by a moderating discussion between the two authors focusing on the aims of this literature review. Subsequently, it was decided that all studies with settings described as providing PC would be included.

Classification of studies

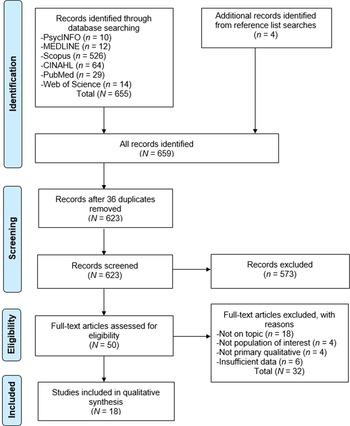

Study selection was recorded on a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff2009; Figure 1).

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram (adapted from Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff2009).

A total of 655 articles were identified following database searches. Four additional studies were identified after reference checking. After eliminating 36 duplicates, the remaining 623 article titles and abstracts were screened excluding a further 573 articles. The full texts of the remaining 50 articles were independently reviewed again by both authors and 32 articles not meeting inclusion criteria were excluded (Figure 1). The final result was 18 studies eligible for inclusion in the review.

Quality assessment

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist (CASP, 2018) was used to assess study quality as it is the most used tool for quality appraisal in health-related qualitative evidence syntheses (Long et al., Reference Long, French and Brooks2020). To enhance reliability, the co-author conducted an independent quality assessment check on all included studies using the same framework. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Cohen's kappa (κ). The overall kappa score was 0.877, suggesting very good inter-rater reliability (Altman, Reference Altman1999).

Quality assessment using the CASP resulted in scores ranging from 12 to 19, with an average score of 17. There were three main limitations of the included studies identified during the current review: sample diversity, researcher's reflexivity, and data analysis. A detailed description of the quality assessment of studies included in this review can be found in the Supplementary materials document.

Characteristics of the literature

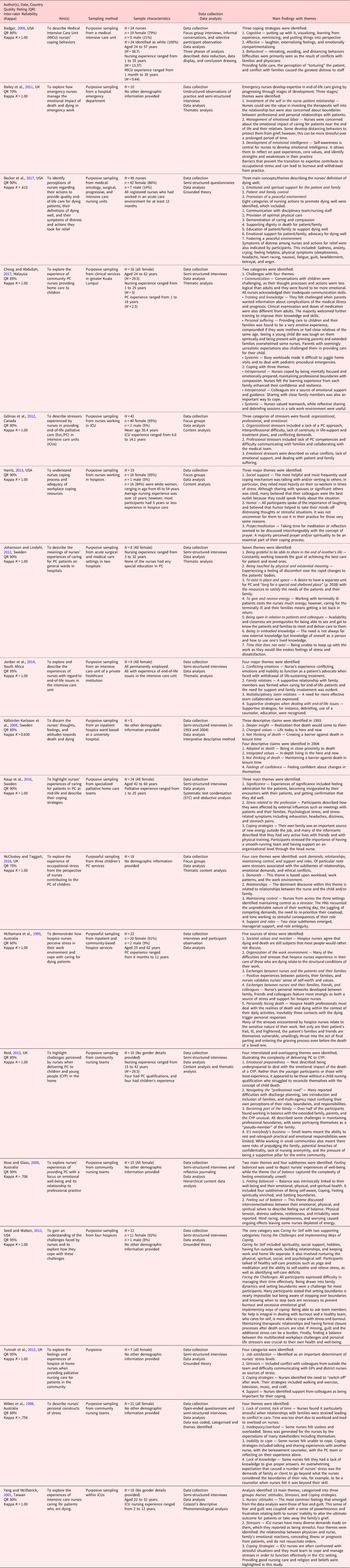

The author(s), date of publication, country, aim(s), sampling method, sampling characteristics, data collection, data analysis, and main findings were extracted from the original articles. A detailed description of the characteristics of studies included in this review can be found in the Supplementary materials document. A summary of the characteristics of the literature is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Characteristics of the literature

Analytic review strategy

Thematic synthesis was used to develop descriptive and analytical themes that extend the primary research studies to generate new interpretations (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008). During Stage One (Coding Text), each study was read with sections highlighted and codes created inductively to capture meaning and content. This resulted in 38 initial codes, such as Coping Strategies, Families Causing Stress, and Feeling Helpless. In Stage Two (Developing Descriptive Themes), the initial codes were grouped according to similarities and differences and descriptive codes were created to capture the meaning of these new groups. Stage Three (Developing Analytical Themes) involved addressing the review question by “going beyond” the original data and inferring PC nurses' experiences of stress, anxiety, and burnout based on the descriptive themes from Stage Two. Through this process, the final three analytical themes emerged. To ensure rigor in the analysis (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008; Houghton et al., Reference Houghton, Murphy and Meehan2017) NVivo 1.4 was used in each of its three stages of analysis (see Supplementary materials for screenshots and examples from each stage).

Results

Thematic synthesis identified three main themes: When work becomes personal, The burden on mind and body, and Finding meaning and connection. An overview of themes and subthemes is provided in Table 4. Additional quotes are provided in the Supplementary materials document.

Table 4. Main themes and subthemes

A summary of each paper's contribution to each main theme and subtheme is shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Summary of paper contribution to each theme

When work becomes personal

This main theme describes how PC nurses’ experiences of stress, anxiety, and burnout were linked with the personal impact of their work. Nurses in all studies apart from four (Källström Karlsson et al., Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008; Rose and Glass, Reference Rose and Glass2009; Tunnah et al., Reference Tunnah, Jones and Johnstone2012; Harris, Reference Harris2013) stated their relationships with a patient's family could be personally challenging and a source of stress. PC nurses “found it particularly stressful when relationships [within the family] were strained” (Wilkes et al., Reference Wilkes, Beale and Hall1998, p. 17) and/or when they were expected “to be the mediator” (Seed and Walton, Reference Seed and Walton2012, p. 5). In addition, some nurses also found it stressful when family members were experiencing difficult and distressing emotions, such as the lack of understanding, or denial, of a patient's palliative medical status. Others saw dealing with a families’ or patient's denial of illness prognosis as the most challenging task (Wilkes et al., Reference Wilkes, Beale and Hall1998, p. 17).

Caring for PC patients requires specialist knowledge and skills to balance the needs of patients and families. Nurses are often the first and main contact for many families. For some, it was a feeling of being under pressure from families for answers that led to their work being experienced as more stressful, “… a lot of relatives involved in the families … all looking to you for an answer … it is more stressful” (Reid, Reference Reid2013, p. 543). Nurses also reported that “families get very needy, and they start needing [the nurse] for every little part from getting [their] father up to poop, to everything that's going on in their personal life” (Seed and Walton, Reference Seed and Walton2012, p. E5).

Having good professional relationships with a patients’ family was seen as important to providing good quality care. However, where nurses had built up a good rapport with families, this was also seen to contribute to increasing stress in some situations (Wilkes et al., Reference Wilkes, Beale and Hall1998, p. 17).

In order to cope with pressure from families, some nurses had developed strategies that allow them to focus on the needs of their patients. Some learnt to “close the door, get [the family] out of the room, out of [their] personal space” (Badger, Reference Badger2005, p. 67). For others, this meant not allowing themselves to get too close to the patient and thus needing to “restrict [themselves] in the relationship” (Johansson and Lindahl, Reference Johansson and Lindahl2012, p. 2,037) to be able to continue to deliver professional support.

The burden on mind and body

This main theme describes how nurses found their work to be both emotionally and physically difficult. Two subthemes are discussed, Emotional impact and Physical impact.

Emotional impact

All but one study (Becker et al., Reference Becker, Wright and Schmit2017) reported the emotional impact that PC work had on nurses. A range of factors were seen to increase the emotional impact that nurses felt, such as having close relationships with patients and their families, the complexity of PC clinical care, and how PC work connected with their personal values:

“The majority of the participants expressed mixed emotions of sadness, grief and anger when caring for patients who presented with end-of-life issues. One participant explained it as follows: “Guilt, anger… helplessness, because… you want to fix it, but you can't. That's kind of sadness obviously…extreme sadness…”

(Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Clifford and Williams2014, p. 78)

Rose and Glass (Reference Rose and Glass2009, p. 188) highlighted nurses felt “out of balance” as a result of an inability to provide the kind of care they wished to give and the need to maintain high professional and personal standards. This for some led to them feeling “stressed, restless, angry. Not content, not happy not all the things that you wish you were. Very short tempered…” and for others to making “rash decisions that [they] wouldn't do”, putting themselves “in the firing line” and even behaving “like [they are] a victim” (Rose and Glass, Reference Rose and Glass2009, p. 189–190). While the emotional impact could lead to feelings of sadness, grief, and anger, positive emotional experiences, such as “the feeling of being needed, appreciated, and confirmed through the caring activities in which they engaged with patients”, which could be protective against stress, were also reported (Källström Karlsson et al., Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008, p. 230).

In 9 of the 18 studies, nurses specifically discussed the impact that patients’ deaths had on them (McNamara et al., Reference McNamara, Waddell and Colvin1995; Källström Karlsson et al., Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008; McCloskey and Taggart, Reference McCloskey and Taggart2010; Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Murphy and Porock2011; Seed and Walton, Reference Seed and Walton2012; Tunnah et al., Reference Tunnah, Jones and Johnstone2012; Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Clifford and Williams2014; Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Höög and Carlsson2016; Chong and Abdullah, Reference Chong and Abdullah2017). Nurses found it particularly difficult when patients died suddenly and unexpectedly (Källström Karlsson et al., Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008); however, it was also recognized that “… personally facing death was an issue that could not be ignored, but that [they] did get used to the idea of death”. (McNamara et al., Reference McNamara, Waddell and Colvin1995, p. 233).

Some nurses reported certain patient groups to be more challenging to work with, such as children (Chong and Abdullah, Reference Chong and Abdullah2017) or mid-life patients (McNamara et al., Reference McNamara, Waddell and Colvin1995; Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Höög and Carlsson2016), while others talked about the impact of having close relationships with patients and their families (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Murphy and Porock2011). Annette reflected on how a patient's death had affected her:

“I think it is more the emotional side of what happens. You just think [about the loss of life] and because the family told me so much personal stuff [information], you just feel for them so much. You are putting yourself in their shoes so much that it makes you emotional. It was just so rotten.”

(Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Murphy and Porock2011, p. 3,367)

Nurses formed close bonds with their patients and reported finding it particularly difficult when “many patients died within a short period or if death came quickly and unexpectedly” (Källström Karlsson et al., Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008, p. 230). In addition, for some nurses, “providing care to children and their families” was identified as presenting them with personal challenges “if [the nurses] are mothers or have close relatives of the same age” (Chong and Abdullah, Reference Chong and Abdullah2017, p. 128).

Two studies also reflected on some of the protective factors against burnout. Seed and Walton (Reference Seed and Walton2012, p. E6) identified the “importance of closure…. being able to be there for the death and see death in that moment” was seen as “optimal”, while Källström Karlsson et al. (Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008, p. 227) highlighted that “being present at the moment of death and taking care of the bodies seemed to result in less anxiety about [the nurses’] own death.”

Twelve of the 18 studies (Yang and Mcilfatrick, Reference Yang and Mcilfatrick2001; Badger, Reference Badger2005; Källström Karlsson et al., Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008; Rose and Glass, Reference Rose and Glass2009; Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Murphy and Porock2011; Gélinas et al., Reference Gélinas, Fillion and Robitaille2012; Johansson and Lindahl, Reference Johansson and Lindahl2012; Tunnah et al., Reference Tunnah, Jones and Johnstone2012; Harris, Reference Harris2013; Reid, Reference Reid2013; Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Clifford and Williams2014; Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Höög and Carlsson2016) discussed nurses’ feelings of helplessness when working in complex care systems, within strict medical hierarchies, and when caring for patients who are not expected to recover from their condition. Jordan et al. (Reference Jordan, Clifford and Williams2014, p. 78) found that nurses “expressed feelings of helplessness when unable to do more for their patients” and when they engaged in “futile or unnecessary care … when dealing with end-of-life issues”.

Organizational pressures such as staff shortages (Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Höög and Carlsson2016), system failures (Rose and Glass, Reference Rose and Glass2009), and difficulties managing their time (Seed and Walton, Reference Seed and Walton2012) were all mentioned as contributing to increased feelings of helplessness and stress. Stress for some nurses was also linked to a feeling that they were not working in the patients’ best interests as were required to keep the diagnosis confidential for cultural reasons connected to a “moral tension that was emerging because they felt uncomfortable with their inability to disclose prognosis” (Yang and Mcilfatrick, Reference Yang and Mcilfatrick2001, p. 439).

Physical impact

Seven of the 18 studies (McNamara et al., Reference McNamara, Waddell and Colvin1995; Wilkes et al., Reference Wilkes, Beale and Hall1998; Rose and Glass, Reference Rose and Glass2009; McCloskey and Taggart, Reference McCloskey and Taggart2010; Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Höög and Carlsson2016; Becker et al., Reference Becker, Wright and Schmit2017; Chong and Abdullah, Reference Chong and Abdullah2017) discussed how nurses were physically impacted by their work; “Bad deaths however, are problematic as well as physically and emotionally exhausting for those who participate in the nursing care” (McNamara et al., Reference McNamara, Waddell and Colvin1995, p. 231). Common symptoms included physical tension, distress, sadness, restlessness and irritability, mind racing and worrying, and sleeplessness (Rose and Glass, Reference Rose and Glass2009).

Physical symptoms of stress were particularly common in studies that looked at nurses working in the community (Wilkes et al., Reference Wilkes, Beale and Hall1998; Rose and Glass, Reference Rose and Glass2009; Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Höög and Carlsson2016; Chong and Abdullah, Reference Chong and Abdullah2017). Interestingly, some nurses reported the symptoms appeared only before or during certain patient encounters while other symptoms were more chronic and related to stress over a longer time period:

“…[nurses] described symptoms such as headache, dizziness, and stomach pain. Sometimes the symptoms appeared only in certain encounters; for example, stomach pain might occur on [a nurses] way to a specific patient where the participant knew it could be difficult. Other symptoms were more long lasting and were often related to stress over a longer period.”

(Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Höög and Carlsson2016, p. 567)

Further, Wilkes et al.'s (Reference Wilkes, Beale and Hall1998) participants reported that physical symptoms of stress and tension they experienced were a combination of work and home life stress.

Finding meaning and connection

The main theme Finding meaning and connection is concerned with how nurses cope with PC work. Despite the work being emotionally demanding, it was common for nurses to want to reflect on and find personal meaning in their roles rather than to distance themselves from it. Within this theme, two subthemes were identified, Feeling fulfilled and Connection with others.

Feeling fulfilled

Eleven of the 18 studies considered how nurses found meaning and reward in their work, giving them a sense of satisfaction and reward (Yang and Mcilfatrick, Reference Yang and Mcilfatrick2001; Källström Karlsson et al., Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008; Rose and Glass, Reference Rose and Glass2009; Gélinas et al., Reference Gélinas, Fillion and Robitaille2012; Johansson and Lindahl, Reference Johansson and Lindahl2012; Seed and Walton, Reference Seed and Walton2012; Tunnah et al., Reference Tunnah, Jones and Johnstone2012; Harris, Reference Harris2013; Reid, Reference Reid2013; Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Höög and Carlsson2016; Chong and Abdullah, Reference Chong and Abdullah2017). Nurses’ descriptions included their work being a privilege (Johansson et al., Reference Johansson and Lindahl2012; Tunnah et al., Reference Tunnah, Jones and Johnstone2012), being professionally rewarding, and giving them a sense of satisfaction (Seed and Walton, Reference Seed and Walton2012; Tunnah et al., Reference Tunnah, Jones and Johnstone2012; Harris, Reference Harris2013; Reid, Reference Reid2013; Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Höög and Carlsson2016).

PC nurses identified that job satisfaction came from feeling as thought they had made a difference; “If you can nurse someone at home and make them as comfortable as possible in their last days of life, it's a privilege to do it … it's well worth everything you do.” (Tunnah et al., Reference Tunnah, Jones and Johnstone2012, p. 286). Nurses acknowledged that PC work is challenging, personally and professionally; however they felt it was rewarding to deliver care during such a private, personal, and devastating time: “It was a very privileged place to be” (Reid, Reference Reid2013, p. 544).

Some nurses described being able to deliver care to the best of their ability as providing a sense of satisfaction and gratitude (Johansson and Lindahl, Reference Johansson and Lindahl2012). Others reported gaining strength and meaning in their roles after having affirming experiences and when they felt stimulated in their work (Källström Karlsson et al., Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008).

Several participants mentioned their spirituality and faith as ways of coping with the stress and impact of a patient's death. These seemed to enable some nurses to find a deeper meaning in their work that connected with their sense of faith. This is highlighted by one of Harris's (Reference Harris2013) participants who stated “it takes more of a toll than I think we know. You have to have a good spiritual base to deal with all” (p. 450).

Connection with others

Fourteen of the 18 studies reported nurses sought the support of other people (“either with another nurse, with the bereavement counsellor, with the palliative care team”; Wilkes et al., Reference Wilkes, Beale and Hall1998, p. 18) to cope with stress and the risk of burnout (McNamara et al., Reference McNamara, Waddell and Colvin1995; Wilkes et al., Reference Wilkes, Beale and Hall1998; Badger, Reference Badger2005; Källström Karlsson et al., Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008; McCloskey and Taggart, Reference McCloskey and Taggart2010; Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Murphy and Porock2011; Gélinas et al., Reference Gélinas, Fillion and Robitaille2012; Seed and Walton, Reference Seed and Walton2012; Tunnah et al., Reference Tunnah, Jones and Johnstone2012; Harris, Reference Harris2013; Reid, Reference Reid2013; Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Clifford and Williams2014; Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Höög and Carlsson2016; Chong and Abdullah, Reference Chong and Abdullah2017). For some nurses, this connection was related to them feeling socially connected to their colleagues at work, while seeking informal support was seen as an important coping strategy. Harris (Reference Harris2013) found that nurses identified talking to colleagues as a key coping strategy, “… the most helpful and most frequently used coping mechanism was talking with and/or venting to others. In particular, members of each of the focus groups reported that they relied most heavily on their coworkers in times of stress” (p. 449). Nurses felt it was important to use informal opportunities, to “chat with my colleague and the district nurses … make sure we have lunch together in the office so that we can chat” (Tunnah et al., Reference Tunnah, Jones and Johnstone2012, p. 288), at work to speak openly about their feelings.

Connections with colleagues were seen not just to help with symptoms of stress but were explicitly identified as preventing burnout. Nurses acknowledged that they relied heavily on their peers as a method of preventing burnout; “… the burnout is definitely there with all of us to a point. We all get to that point where I just, I just can't do it, but we bounce back real fast. We have a great team so we just work and talk among each other and help each other out” (Seed and Walton, Reference Seed and Walton2012, p. E5). While colleagues were most commonly mentioned, family relationships and having contact with others outside of work were also reported as protective factors against the impact of nurses’ work building up (McNamara et al., Reference McNamara, Waddell and Colvin1995; Källström Karlsson et al., Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008; Tunnah et al., Reference Tunnah, Jones and Johnstone2012; Kaup et al., Reference Kaup, Höög and Carlsson2016). The concept of connection with others being a “release” is articulated here by a nurse working in a hospital inpatient setting:

“Stable and functioning family relationships were desirable so that the nurses could regain their strength during their leisure time. Spending time with children and adults outside the family or professional colleagues was understood as a shield against thoughts of death. Meeting other people who were full of life “and talking about something completely different” was like a release.”

(Källström Karlsson et al., Reference Källström Karlsson, Ehnfors and Ternestedt2008, p. 288)

Others talked about finding it difficult to get support from outside of work due to the lack of understanding from those who do not work in PC; “Many nurses indicated that they thought people outside of the hospice “system” lacked an understanding of what was involved in caring for the dying” (McNamara et al., Reference McNamara, Waddell and Colvin1995, p. 229). Finally, nurses reflected on how their family members often did not want to hear about their work; “Could you change [the] subject?” … “It's depressing.”. “Do you have to talk about this over dinner?” (Gélinas et al., Reference Gélinas, Fillion and Robitaille2012, p. 32)

Discussion

This review addressed the question, “What are palliative care nurses’ experiences of stress, anxiety and burnout?”. Thematic synthesis identified three main themes.

When work becomes personal

PC nurses described how difficult relationships with a patient's family were seen as potential sources of stress and burnout. Conversely, some nurses with close personal relationships with families also found this to be stressful.

While the current review supports previous findings on the impact of conflict (François et al., Reference François, Lobb and Barclay2017), it also highlights how close personal relationships with families contributed to nurses’ experience of stress and burnout. Specifically, it extends our understanding of the different ways nurses can be affected by relationships with patient's families, and the importance of supporting nurses to recognize the impact of their professional relationships with patient's families to reduce the potential for increased stress, anxiety, and burnout.

The burden on mind and body

PC nurses were emotionally and physically impacted by stress, anxiety, and burnout, experiencing sadness, grief, anger, guilt, frustration, unhappiness, and dissatisfaction with themselves. These findings are consistent with the existing literature (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Cant and Payne2013; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Lee and Bloomer2018; Powell et al., Reference Powell, Froggatt and Giga2020; Zanatta et al., Reference Zanatta, Maffoni and Giardini2020). Furthermore, these findings are congruent with the work of Figley (Reference Figley1995, Reference Figley2002) exploring stress and compassion fatigue as seen in nurses supporting patients suffering traumatic events. However, this review also highlighted how positive experiences can moderate stress, anxiety, and burnout which has been seen as a limitation of Figley's original model (Sabo, Reference Sabo2011).

Feelings of helplessness were reported in many of the current review's studies. These feelings were related to clinical, personal, and organizational issues and contributed to nurses’ stress levels were also highlighted. This finding is supported by Powell et al. (Reference Powell, Froggatt and Giga2020) whose systematic literature review also found personal factors and organizational workload pressures to be key factors in PC nurses’ stress levels.

Nurses in the current review described how patients’ deaths affected them in deeply personal ways. This could be due to several factors including nurses’ relationships with patients due to the patient's age, cultural background, or when patients suddenly and unexpectedly died. These findings are supported by Malone et al.'s (Reference Malone, Anderson and Croxon2016) systematic literature review which identified that patient factors, such as age and cultural background, can impact on how nurses cope with patients’ deaths; however, their review was only looking at newly graduated nurses in PC.

Nurses also experienced physical symptoms of stress, anxiety, and burnout. Nurses consistently reported sleep difficulties, with tension and headaches common. This impacted them in several ways, including at home and work, with some nurses reported not being able to concentrate, feeling agitated, and unbalanced. These findings support Baqeas and Rayan's (Reference Baqeas and Rayan2018) that PC nurses’ sleep and physical well-being are significantly impacted by their work.

Finding meaning and connection

Nurses’ feelings of fulfillment and connection with others for support were discussed in relation to whether they experienced work to be stressful or not. Where nurses reported feeling fulfilled, a sense of satisfaction and pride in their work, they also talked about how this made the challenge of PC work worthwhile. Nurses also reported finding meaning in their spirituality and religion in six of the studies. A recent systematic review by Sekse et al. (Reference Sekse, Hunskår and Ellingsen2018), looking at nurses’ roles in PC, found that feelings of fulfillment were present when nurses felt they were able to be “attentively present and dedicated” (Sekse et al., Reference Sekse, Hunskår and Ellingsen2018, p. 33).

Nurses found seeking support from family and their colleagues helped them cope. Nurses identified that open and honest conversations about the impact of their work were important in reducing stress in the short-term and burnout in the longer-term. Spending time with others unconnected to their work was also important in helping them cope. This is consistent with other systematic reviews in PC nursing which have identified nurses’ need to express their emotional responses to others, whether with colleagues, friends, or family (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Froggatt and Giga2020; Zanatta et al., Reference Zanatta, Maffoni and Giardini2020).

Limitations

Efforts to synthesize findings meant trying to find a balance in papers’ inclusion and exclusion decisions, given PC's definition in research varies depending on the workplace setting. While all participants were nurses engaged in providing PC as part of their main role, the homogeneity of participants should be considered when interpreting the review's conclusions. For example, participants were recruited from inpatient, hospices, and community settings, and from countries with acknowledged cultural differences in attitudes to PC. Additionally, the search terms “compassion fatigue” and “secondary traumatic stress” were not included. These related concepts are well established in hospice and PC literature (Melvin, Reference Melvin2015) and their omission limits the search results and findings.

Clinical policy and practice implications

Findings from this review support and further demonstrate the complexity of feelings PC nurses have about their role, which may help both nurses and services take action to mediate against nurses’ experiences of stress, anxiety, and burnout. The findings may also help expand our understanding of how patient deaths impact PC nurses and how to better support them in this critical aspect of their work. Two main policy and practice implications were identified within the reviewed studies: greater staff support and more relevant learning and development opportunities.

Harris (Reference Harris2013) highlighted that having someone to talk to would be beneficial on a particularly stressful or painful day or when nurses experienced loss. Similarly, staff support groups that were not specific to grief alone were “facilitated by someone outside of hospice” and having their content kept “confidential” would be welcome (Harris, Reference Harris2013, p. 451). These findings are broadly consistent with research that has identified greater access to social support as protective against occupational stress in healthcare workers (Ta'an et al., Reference Ta'an, Al-Dwaikat and Dardas2020).

Seed and Walton (Reference Seed and Walton2012) suggested that nurse managers should regularly assess the stress and coping ability of their teams, to ensure nurses have/receive unscheduled time off because of undue stress and working with difficult families. Tunnah et al. (Reference Tunnah, Jones and Johnstone2012) similarly identified the need for further use of clinical supervision and reflection.

Further, staff training has been highlighted to support nurses having greater clarity on how to respond to challenging care situations as well as improving their abilities to identify stress and recognize their own emotional needs. This could include meaning-based reflective practice sessions which have been associated with greater self-awareness and less burnout in other healthcare professional groups (Heath et al., Reference Heath, Sommerfield and von Ungern-Sternberg2020). Finally, Becker et al. (Reference Becker, Wright and Schmit2017) suggested training staff to better communicate with families regarding helpful and harmful care during the end of life.

Further research

Research is needed to gain a more nuanced understanding of how PC nurses are affected by their work. For example, through exploring the experiences of nurses with a longer tenure working in PC, or by the use of longitudinal studies evaluating the emotional and physical impact of PC work. Finally, further studies could focus on helping education providers and employers better understand their role in training and staff support, for example when preparing newly qualified nurses who choose to work in PC.

Furthermore, recruitment of more diverse participant samples and reporting of relevant participant demographics could widen the range of views and experiences within the literature. Discussion of the relationship between researchers and participants and any conflicts, or potential bias, should also be included. Finally, research should be undertaken using appropriate research methods with clear reporting in methodological sections. Addressing these issues would improve the quality, replicability, and validity of research findings.

Conclusion

The current review explored PC nurses’ experiences of stress, anxiety, and burnout. Three main themes were identified which suggest that PC nurses' experiences are complex, encompassing clinical and organizational challenges, and the personal impact their work has on them. The findings of this review highlighted that nurses’ relationships with patients, patients’ families, and colleagues, can be both a source of stress and strength. While many nurses describe their work as difficult, they also find it personally and professionally rewarding.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S147895152200058X.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.