Globally, 1·3 billion tonnes of food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted every year, with serious environmental, financial and public health consequences(1). ‘Food loss’ refers to the decrease in edible food at the point of production, post-harvest and processing stages of the food supply chain; ‘food waste’ refers to the decrease in edible food at the end of the food chain or at the point of retail or consumption(1). The USA, the UK and Japan are the three industrialized countries that produce the greatest amount of food waste(Reference Melikoglu, Lin and Webb2). The UN Sustainable Development Goals has set a target of decreasing global food waste at the retail and consumer levels by 50 % by 2030(3). Such steep reductions will require engagement and cooperation across sectors and at all scales(3,Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken4) .

Schools are considered critical partners in global efforts to address food waste(5). In addition to educating students about the importance of this issue, schools can reduce food waste, also known as ‘plate waste’, through their lunch programmes. In the USA, the problem of school lunch waste in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) has been recognized for decades(Reference Byker Shanks, Banna and Serrano6,Reference Izumi, Bersamin and Byker Shanks7) . The NSLP is a federally assisted meal programme that provides students with nutritionally balanced and free or low-cost lunches each school day(Reference Izumi, Bersamin and Byker Shanks7). A recent literature review reported that more than 30 % of food served in the NSLP is discarded(Reference Byker Shanks, Banna and Serrano6). In addition to its environmental and financial costs, school lunch waste is a significant issue because students who throw away their food do not benefit from the nutrition it could provide. The impact of school lunch waste may be greatest for low-income children who depend on school meals as an important source of nutrition(Reference Murayama, Ishida and Yamamoto8–Reference Huang and Barnidge10). Studies of waste in the NSLP have focused on increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables through strategies such as extending the lunch period(Reference Hildebrand, Millburg Ely and Betts11), scheduling recess before lunch(Reference Bergman, Buergel and Englund12) or creating share tables where students can leave whole food or beverage items they do not want to eat, making the items available to students who want additional servings.

Japan provides a unique case study to examine school lunch waste because, although food waste at the national level is high, food waste generated through its national school lunch programme is relatively low – approximately 6·9 %(13). Furthermore, the high level of food waste at the national level stands in contradiction to the Japanese concept of mottainai, which represents a deeply ingrained social norm(Reference Lewis, DeVellis, Sleath, Glanz, Rimer and Marcus Lewis14) to respect resources (e.g. natural resources, food, material objects, individual skill) and use them to their fullest potential and with a sense of gratitude.

The modern-day school lunch programme in Japan was established in 1954 through the School Lunch Act(15). In 2015, over 20 300 elementary schools provided lunch to more than 6·5 million children in grades 1 through 6(16). The primary purpose of the act is to promote the healthy physical, mental and social development of children through a school lunch programme that is an integral part of the national school curriculum for elementary and junior high schools and in which all students must participate. School lunches are nutrient-based and provide at least one-third of the daily recommended allowance for energy and various nutrients(Reference Ishida17) (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S1). Funding for the school lunch programme is shared between families, the local government and the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, which administers the programme at the national level(15). Families pay for the cost of ingredients and local and national governments pay for direct costs, including labour and overheads, and provide financial support to help offset the cost of school lunches for low-income families(15).

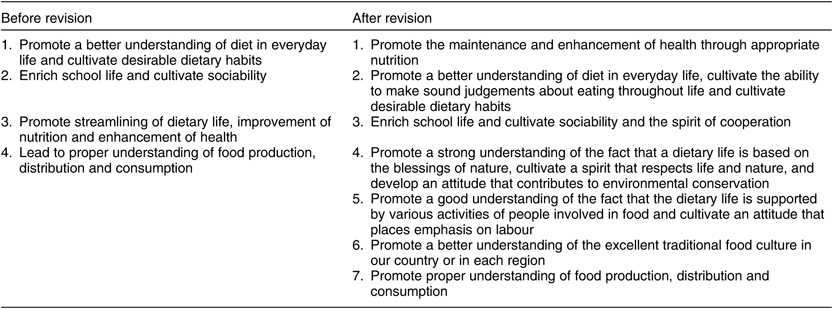

In 2008, the goals of the School Lunch Act were revised(Reference Ishida17) to reflect the priorities expressed in the Shokuiku Basic Act, a unique piece of legislation passed in 2005 to address a wide range of food and nutrition problems, including increasing rates of diet-related chronic diseases, decreased frequency of cooking at home and eating together, shrinking agriculture and fishing industries, low national food self-sufficiency and loss of traditional food culture due to globalization(18). The law aims to address these societal ills through promotion of shokuiku, which is usually translated into English as ‘food education’ but encompasses a more holistic approach to addressing food and nutrition problems than simply educating individuals and emphasizes multilevel linkages. The Shokuiku Basic Act identifies schools as a primary site for shokuiku promotion(Reference Ishida17,18) . In addition to promoting healthy physical, social and mental development of children, the goals of the revised School Lunch Act include a focus on cultivating respect for nature and food labour and traditional and regional food culture. Table 1 shows the goals of the School Lunch Act before and after passage of the Shokuiku Basic Act(Reference Ishida17).

Table 1 Goals of school lunches in Japan before and after the School Lunch Act(Reference Ishida17) was revised in 2008

To date, only a few quantitative studies have examined factors that influence lunch waste in Japanese elementary schools(Reference Abe and Akamatsu19–Reference Abe and Akamatsu23). Self-efficacy to finish a meal(Reference Abe and Akamatsu20,Reference Abe and Akamatsu23) , time for eating(Reference Abe and Akamatsu20,Reference Abe and Akamatsu23) , preference for vegetables(Reference Taniguchi and Akamatsu24), concept of mottainai (Reference Taniguchi and Akamatsu24) and palatability of a meal(Reference Abe and Akamatsu23) have been associated with food waste behaviour in 5th- and 6th-grade students. In a study of food waste in one Tokyo elementary school, Tada et al. found that some food categories (e.g. vegetables, rice, fish, traditional Japanese meals) generated more food waste than others and that younger students (i.e. 1st and 2nd grades) discarded more food than older students(Reference Tada, Umemoto and Ikeda22). Abe and Akamatsu reported that perceived behavioural control is associated with food waste behaviour(Reference Abe and Akamatsu19). Additional research is needed to understand these factors within the cultural context of Japanese society(Reference Levine, Miyamoto and Markus25).

Our ethnographic study is the first to use qualitative methods to provide a more in-depth understanding of the cultural context surrounding school lunch waste in Japan. The objectives of our study were to explore how these and other factors minimize food waste in Japanese elementary schools and to consider how such factors can be modified and applied in US schools.

Methods

We conducted a focused ethnographic study in Tokyo, the capital of Japan, in five different elementary schools. Ethnography is a qualitative research method that allows researchers to examine social and cultural phenomena within their natural settings(Reference Angrosino26). The research team consisted of two US researchers (B.T.I. and C.B.S.) and two Japanese researchers (R.A. and K.F.). B.T.I. led the study while she was a Fulbright US Scholar at Ochanomizu University in Tokyo.

We used maximum variation sampling, a purposeful sampling technique aimed at capturing central themes that emerge from diverse cases. We constructed a matrix of school lunch programmes in Tokyo that varied on characteristics such as such as number of meals served and programme type (e.g. off-site school lunch centre v. on-site kitchen) and used the matrix to identify six school dietitians or diet and nutrition teachers to participate in our study. School dietitians and diet and nutrition teachers were selected to participate in our study because they are responsible for overseeing school lunch programmes and shokuiku promotion. Diet and nutrition teachers are school dietitians who have a teaching certificate. They are considered part of the teaching staff and therefore also spend time on tasks such as leading extracurricular activities, including after-school clubs and sports(Reference Ishida17). In Japan, nemawashi, a subtle form of communication in which an individual with insider trust gathers support for a project, is essential to conducting research(Reference Fetters27,Reference Martinus and Hedgcock28) . Therefore, school dietitians and diet and nutrition teachers already known to the Japanese members of the research team were invited to participate in our study. Five school dietitians, including three diet and nutrition teachers(Reference Ishida17), agreed to participate; one declined due to her limited availability during our data collection period.

Table 2 shows demographic and site characteristics of the study participants. All five dietitians were female. Although three of the dietitians were diet and nutrition teachers, only one was employed as a diet and nutrition teacher; the other four worked as school dietitians. The number of years of experience working as a school dietitian ranged from 5 to 25 years. Four study participants worked as on-site dietitians in elementary schools that served 390–650 meals daily. One worked as an off-site dietitian in a school lunch centre serving 4200 meals daily across seven elementary schools and three junior high schools.

Table 2 Demographic and site characteristics of school dietitians (n 5) who participated in an ethnographic study of lunch waste in Tokyo elementary schools, November 2017–March 2018

Data collection

In order to enrich our understanding of factors that minimize school lunch waste in Japanese elementary schools and to enhance the credibility of our findings, we collected data using multiple sources: in-depth interviews with the dietitians, observation of nutrition education lessons, participant observation(Reference Jorgensen29) (i.e. observation while taking part in the activity) of school lunch and review of relevant school documents. In-depth interviews were conducted with the study participants (n 5) between November 2017 and March 2018. All data collection protocols were developed by the bilingual members of the research team (B.T.I., R.A. and K.F.) through an iterative process. The primary researcher (B.T.I.) and one Japanese researcher (R.A. or K.F.) interviewed each dietitian simultaneously using a semi-structured interview guide to ensure that all questions were covered and to accommodate the limited amount of time with each of the interviewees. Interviews were conducted in Japanese and audio-recorded. Probes and follow-up questions were asked to elicit depth of information and to follow up on leads initiated by the interviewees. Table 3 provides examples of interview questions related to the present study. School dietitians received the interview questions by email one week before the interview to give them time to consider their answers. Interviews lasted approximately an hour and took place in a meeting room at the school or school lunch centre. An independent transcriber transcribed the interviews verbatim and an independent bilingual-bicultural translator translated the transcripts into English. The bilingual members of the research team discussed each interview to ensure that translations were technically and conceptually accurate(Reference Squires30).

Table 3 Sample interview questions for school dietitians (n 5) who participated in an ethnographic study of lunch waste in Tokyo elementary schools, November 2017–March 2018

To gain a better understanding of how school lunch and nutrition education are implemented in Japanese elementary schools, the researchers observed a nutrition education lesson conducted by each of the dietitians and reviewed relevant school documents (e.g. lunch menus, food waste records, monthly newsletter). The researchers observed six nutrition education lessons, including one lesson the off-site dietitian conducted twice at one school and one lesson taught by each of the four on-site dietitians. Immediately before or after each lesson, the researchers ate school lunch with a class selected in advance by the school dietitian. During each observation and participant observation, the researchers recorded notes (e.g. factual data, setting, behaviours, conversations, follow-up questions) on a summary template and took photographs; B.T.I. expanded the notes and photographs into memos within 2 h after leaving the school in order to minimize loss of data due to recall limitations. Observation and participant observation notes included a description of the lesson topic, length of lesson, grade level of participants, materials used, school lunch menu, and teacher and dietitian behaviours.

Data analysis

We analysed data using thematic analyses(Reference Guest, MacQueen and Namey31). After each data collection, B.T.I. and C.B.S. identified emerging themes and concepts and created operationally defined codes, which were added to a code book. B.T.I. and C.B.S. independently coded all five interview transcripts and compared them for inter-coder reliability(Reference Guest, MacQueen and Namey31). Coded transcripts were shared with R.A. and K.F. and coding discrepancies were resolved through discussion until the entire research team reached 100 % agreement. The research team used the coded transcripts to develop a series of matrices to determine themes before drawing study conclusions(Reference Miles and Huberman32). B.T.I. presented the study findings during a member-checking process that engaged study participants and school dietitians who were not involved in the current study. This process was used as a validation technique to ensure that the results resonated with their experiences(Reference Creswell and Miller33).

Results and discussion

The first part of this section describes school lunchtime in Japan. The second part summarizes factors that minimize school lunch waste obtained through interviews with school dietitians (I), observations (O), participant observation (P) and document analysis (D), and is organized into major themes discussed within the context of the existing literature(Reference Goonan, Mirosa and Spence34): school lunchtime, social norms, menu planning, integrated school curriculum, teacher lunchtime practices and school lunch student committee. Then, based upon the themes that emerged from the data, we consider how factors that minimize school lunch waste in Japan can be modified and applied to reduce lunch waste in US schools.

School lunchtime

In most Japanese elementary schools, students and homeroom teachers eat the same food together in their classrooms during lunchtime (I). Meals are generally made from scratch using basic ingredients in an on-site school kitchen or off-site at a school lunch centre that serves multiple schools (I). Each week, students rotate through school lunch toban (duty) (I). The toban group is responsible for retrieving lunch carts, setting up the serving line, serving lunch to their classmates and teacher, cleaning up lunch, and returning tidy lunch carts to the on-site kitchen or receiving area (P). The lunch carts contain commercial size pots and pans, with the classroom portion of each menu item, single-serve milk cartons, serving utensils, and silverware or chopsticks (P). While the toban group sets up the serving line, the rest of the class rearranges the desks from rows into clusters of small groups and then lines up for lunch (P). The toban group serves each student a portion of each menu item (P). Before eating, the class conveys respect and appreciation for the food with the Japanese custom of placing their palms together and saying itadakimasu (‘I humbly receive’) in unison; after eating, the students and teacher say gochisousama (‘it was a feast’) in unison to express their gratitude for the meal (P). Students then return their lunch trays, dishes and eating utensils to the lunch cart, and break down and rinse their milk cartons for recycling (P). The toban group returns the lunch cart, including the pots and pans containing leftovers, to the kitchen or receiving area (P). The amount of leftover food is measured using a scale and recorded in a logbook (i.e. food waste record) before it is composted or thrown away (I).

Social norms

One dietitian emphasized that children in Japan grow up with a sense that they should not have leftovers (I). This sentiment is consistent with a study of Japanese 5th and 6th graders, which showed that feeling mottainai is associated with amount of leftovers(Reference Taniguchi and Akamatsu35). School dietitians are required to measure and report lunch waste to their principals on a daily basis, which in and of itself contributes to reinforcing the social norm to eat without waste (I, D). One dietitian, for example, indicated that her principal checked her daily food waste record and questioned her if the record did not show zero waste; his carefully monitoring of the records motivated her to dedicate substantial time and energy to reducing food waste (I).

All five dietitians reinforced the social norm to eat without waste through incentives, rewards and their presence in classrooms during the school lunch period (I, P). Two on-site dietitians provided classes with incentives to motivate students to minimize classroom food waste (I). One dietitian rewarded classes with 50 d of zero food waste with a sticker and the opportunity to make a menu request (I, P, D). Another dietitian gave classes with low levels of food waste extra food (e.g. mandarin oranges) provided by the school’s vendor (I). In one such class, the students believed that the extra food was a reward for consistently eating all of their school lunch and took pride in their reputation as a class that eats without waste (P). The four on-site dietitians regularly visited classrooms that generated high levels of food waste to motivate students to finish all of their food. One dietitian stated, ‘Children tend to eat better if I visit a class that has not been eating well.’ The off-site dietitian was not able to visit classrooms on a regular basis and relied on homeroom teachers to reinforce the social norm to eat without waste (I).

Menu planning

All five school dietitians emphasized the importance of teaching students to eat a wide variety of foods, including foods that are unfamiliar or disliked, in order to maintain a healthy diet (I). School lunch menus varied from day to day and included a diversity of foods from each of three food groups: green (main source of vitamins and minerals), red (main source of protein) and yellow (main source of energy) (D). Although unfamiliar or disliked foods generated higher levels of waste than familiar or favourite foods, the dietitians believed that exposing students to a wide variety of foods by including them on the school lunch menu would help students to learn to eat all foods without waste (I). Three dietitians believed that the number of foods served for school lunch that students are unfamiliar with or dislike has been increasing due to the Westernization of home diets, which limits student exposure to traditional Japanese foods at home (I). This is consistent with a previous study reporting higher food waste when Japanese main dishes were served for school lunch v. Western main dishes(Reference Tada, Umemoto and Ikeda22).

When menu planning, the dietitians included items with high levels of food waste using different ingredients or methods of preparation each time to help students to develop a refined palate that allowed them to experience new flavours and tolerate, or even enjoy, previously disliked foods (I, D). One dietitian also said that she reduced classroom portions of menu items with high levels of food waste in order to minimize leftovers while still exposing students to new flavours (I).

All five dietitians expected some level of food waste given their overall approach to menu planning, especially among younger children who have had less exposure to school lunch (I). Indeed, quantitative studies of school lunch waste have reported significantly higher food waste ratios among younger students compared with older students(Reference Tada, Umemoto and Ikeda22). However, as one dietitian described, by the time students are in 6th grade, they are familiar with all of the foods served for lunch, have greater self-efficacy to eat disliked foods and have expanded their repertoire of menu items that they are able to eat without waste (I).

Integrated school curriculum

School dietitians are required to collaborate with homeroom and subject teachers to develop an annual shokuiku plan that describes how schools will meet School Lunch Act goals(Reference Ishida17). The dietitians delivered shokuiku through multiple educational strategies, including short and long lessons taught by the dietitian alone or team taught with the homeroom or subject teacher, and written material such as menus and newsletters. The school lunch programme is considered the core educational strategy for shokuiku promotion and a daily opportunity for students to put their food and nutrition knowledge and skills into practice(Reference Ishida17). All five dietitians addressed food waste directly in their annual shokuiku plans through topics that focused on eating a balanced meal without likes and dislikes, eating with a feeling of gratitude and chisan-chisho (Reference Kimura and Nishiyama36), a national movement promoting the localization of food production and consumption (I, D). The four on-site dietitians also wrote a daily lunch letter to students in which they described the menu, including the nutritional content and health benefits of each item, its cultural significance (if any) and where they sourced the ingredients (I, D).

Consistent with a recently published systematic review of food and nutrition education topics implemented since the Shokuiku Basic Act was enacted(Reference Hosoyamada and Miyahara37), eating with a feeling of gratitude was a prominent shokuiku topic among the dietitians who participated in the current study. All five dietitians educated students about the people and processes involved in food production, preparation and waste (D, I, P). Four on-site dietitians collaborated with teachers to engage students in growing, harvesting or preparing food for use in school lunches (D, I). Three of the dietitians built relationships between farmers and students by inviting farmers to visit the class, showing students pictures of the farmer and the farm, and/or highlighting stories in the monthly menu or newsletter and the daily lunch letter about the farmer or class that grew the food (D, I, P). In accordance with previous reports(Reference Taniguchi and Akamatsu35), four dietitians indicated that such experiences improved attitudes towards and increased appreciation for and excitement about locally grown food. Three dietitians believed that students ate more of their school lunch when the ingredients used were grown by a farmer they knew or by other students at the school (I).

Shokuiku at schools served by school lunch centres is the responsibility of a shokuiku committee made up of school staff, including teachers, and off-site dietitians employed by school lunch centres (I). The off-site dietitian who participated in the current study acknowledged that time constraints and the need to provide the same lessons to all of the schools to which she was assigned limited the number of shokuiku lessons she was able to conduct and prevented her from inviting farmers to visit classes (I).

Teacher lunchtime practices

Teachers are responsible for implementing school lunch in their classrooms and all five dietitians emphasized that teacher practices related to portion sizes, distributing leftover food and managing time during the lunch period influenced the amount of food that students consumed and wasted (I).

Classroom food portions are determined based on the number of students in the class and grade level of the class (I, D). In theory, the toban group uses a picture of the lunch to serve each student the same portion of each menu item (I). In practice however, some teachers allow students to request smaller or larger portions of some or all of the items (I, P). After all of the students have been served, but before the meal begins, teachers generally allow students to return to the serving line to increase or decrease their meal portions (I, P). According to one dietitian, ‘allowing students to tailor their lunch portion increases the likelihood that students will learn to take the amount of food that is right for them. With practice, they will be able to finish all of the food on their plates’ (I).

Four school dietitians described teacher practices related to the distribution of leftover food as an important factor that influences school lunch waste (I). The researchers observed that older students managed the distribution of leftover food in their classrooms by, for example, helping themselves to second servings and organizing themselves in a game of janken, the Japanese equivalent of the game Rock Paper Scissors, to compete for leftovers of popular items (P). In contrast, younger students were typically served seconds by their teachers who walked around the room with the pots and pans containing the leftover items while asking students if they wanted seconds (P). The dietitians considered the active distribution of leftovers as an important practice for achieving zero school lunch waste, especially among 1st graders whose limited experience with school lunch meant that they may be more hesitant than older students to serve themselves seconds (I). Although quantitative studies have shown that such practices are associated with lower levels of school lunch waste(Reference Shimpo, Fukuoka and Akamatsu21), the degree to which teachers engaged in distributing leftovers varied (P, I).

Teacher practices related to managing time during the lunch period also varied (P, I). The lunch period is meant to be enjoyable and a chance for students to socialize with their classmates. However, too much socializing can result in students being unable to finish their meal within the allotted time, about 40 min, including time to set up, serve, eat and clean up lunch. To promote mindful eating practices, some teachers set a timer for mogu-mogu, which is a short period of time (i.e. 5–10 min) during which students eat in silence (P, I). One dietitian emphasized that this strategy for managing time during the lunch period is particularly effective for younger children who need more time to set up, serve, eat and clean up lunch (I). Some teachers also allow their students to continue eating after the lunch period has ended while the rest of the class moves on to their next period, which may be souji (cleaning the classroom or school) or recess (P, I).

The variation in lunchtime practices of teachers was not surprising given that teachers are given a fair amount of leeway in how they implement school lunch in their classrooms (I). Because the subject generally is not part of teacher education programmes, teachers largely rely on their own experiences in constructing their approaches to school lunch(Reference Shimpo, Fukuoka and Akamatsu21).

School lunch student committee

All 5th and 6th graders in Japan belong to student committees (e.g. caring for school flowerbeds, planning for annual field day, school lunch), which are meant to foster positive relationships among students and to encourage them to solve problems and improve school life through cooperation with other students and with the support of teachers and other school staff. All four on-site dietitians provided support to the school lunch student committees at their schools and described ways in which these committees contributed to reducing school lunch waste (I, D).

At a minimum, the school lunch student committees periodically measured the school lunch waste generated by each class using a scale and reported it to the dietitian. One dietitian stated that this helped to reduce food waste because ‘some students will eat well only when they know that their peers will be measuring school lunch leftovers’ (I). In addition to measuring school lunch waste, school lunch student committees also made posters, presentations and school-wide announcements encouraging students to eat without waste (I, D). At one school, the committee conducted a school-wide survey to identify favourite and least favourite foods among students and used the findings to develop recipes that featured the least favourite foods (I, D). The recipes developed by the committee were used in school lunch menus, which reportedly resulted in minuscule amounts of food waste (I, D). The off-site dietitian did not provide support to the school lunch student committees at the schools to which she was assigned, suggesting that such student involvement does not depend on the presence of an on-site dietitian (I).

Application of findings to the US National School Lunch Program

Examining factors that minimize school lunch waste in Japan provides an opportunity to consider how such factors could be modified and applied to the US NSLP. The cultural contexts of the US and Japan play important roles in shaping eating behaviour(Reference Levine, Miyamoto and Markus25). Eating without waste is a culturally normative behaviour in Japan(Reference Watabe, Liu, Bengtsson, Sahakian, Salona and Erkman38) and is considered an expression of gratitude for nature and the people involved in growing and preparing food(Reference Taniguchi and Akamatsu35). The school dietitians who participated in the current study reinforced this social norm by positively characterizing students who finished their meals and providing incentives and rewards to motivate students to eat without waste. In the USA, food and nutrition professionals encourage self-regulation and recommend child feeding practices that divide the responsibility for eating between the adult and child(Reference Satter39,Reference Nicklas and Hayes40) . According to this practice, the role of the adult is to provide the child with a positive eating environment and nutritious foods while children are responsible for whether and how much, if anything, to eat from what adults provide. The NSLP policy of division of responsibility is reflected in its ‘Offer Versus Serve’ provision, which is required for high schools and is optional for elementary and middle schools, and allows students to decline some of the food offered to reduce food waste(Reference Izumi, Bersamin and Byker Shanks7). The cultural context of food waste behaviour has a powerful effect on what children eat and waste, and must be considered, together with other influences, when developing recommendations to reduce food waste in the NSLP.

Although the cultural contexts of Japan and the US differ substantially, our study uncovered valuable insights about school lunch waste in Japan that can inform efforts to address food waste in US schools. We highlight four practical and tangible recommendations for food and nutrition professionals and educators who are interested in addressing food waste in the NSLP: (i) measure school lunch waste daily; (ii) educate students about the importance of reducing food waste; (iii) offer students flexible portion sizes; and (iv) provide students with meaningful opportunities to address food waste in their schools.

Currently, no federal policies exist for US schools to systematically measure and report their lunch waste, although the US Environmental Protection Agency and US Department of Agriculture publish guidance about strategies to measure the amount of food wasted in the cafeteria for schools that choose to undertake a food waste audit(41). Our study may spur policy makers, school administrators, teachers and nutrition researchers to begin collecting these data in order to understand the scope of the problem and devise evidence-based solutions. For example, school food-service professionals can use food waste reports to make menu changes or develop new recipes. Further, the decision to measure and report food waste can, in and of itself, influence social norms by sending a signal of institutional support for reducing food waste(Reference Tankard and Paluck42).

Our study also points to the importance of increasing student knowledge about the problem of food waste as an important first step to changing behaviour(Reference Hosoyamada and Miyahara37). While educational resources focused on reducing food waste already exist(43), the extent to which teachers use these resources or the effectiveness of these materials is unclear. In Japan, shokuiku promotion is largely focused on the topic of eating with a feeling of gratitude(Reference Hosoyamada and Miyahara37). Educational resources that promote an understanding of food as a gift of nature and that emphasize labour in the food system may be beneficial in the USA. While knowledge is necessary, however, efforts to educate students about food waste should be paired with environmental and policy changes for greatest impact(Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O-Brien44).

In addition to extending the lunch period(Reference Hildebrand, Millburg Ely and Betts11) and scheduling recess before lunch(Reference Bergman, Buergel and Englund12) (two environmental strategies that have been shown to reduce food waste in US schools), offering students flexible portion sizes may reduce leftovers by enabling students to practice gauging their hunger levels and taking the amount of food they can eat without waste. Currently, however, the NSLP requires students in kindergarten through 12th grade to select meals that include three of the five meal components (i.e. grains, meals or meat alternatives, vegetables, fruit, milk) in the required quantities(Reference Byker, Pinard and Yaroch45) (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table S2). By contrast, federal regulations give schools serving children of pre-school age and providers participating in the Child and Adult Care Food Program(46) (a federal programme that provides reimbursements for meals and snacks served to children enrolled in childcare centres or other institutions that provide day care services) the option of offering family-style meals in which children serve themselves from communal platters of food. While adults are required to encourage children to serve themselves the full required portion of each meal component, if children choose not to take the full minimum serving size, the meal may still be reimbursed. Policy changes that also allow schools participating in the NSLP some latitude in the initial portion of food served to students in kindergarten through 12th grade should be considered in order to reduce food waste and support the development of lifelong healthy eating habits by enabling eating self-regulation among students(Reference Satter39).

Finally, our findings suggest that students are integral to the process of reducing school lunch waste. The Let’s Eat! Engaging Students in Smarter Lunchrooms(47) guide provides information about building a School Lunch Advisory Committee to engage middle- and high-school students in creating lunchroom environments that encourage students to make healthy choices and waste less food. Such committees can provide meaningful opportunities for students to contribute to solving the problem of school lunch waste through, for example, weighing food waste(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken4).

Study limitations

The focused ethnographic approach we used provided an in-depth and nuanced understanding of factors that minimize school lunch waste in Tokyo elementary schools. However, we also note several limitations to our study. First, we carried out our study with a small sample of dietitians who worked in Tokyo elementary schools and therefore caution should be taken in attempting to generalize these findings to other settings in Japan. Future studies should include a larger sample of dietitians working in urban and rural elementary schools in Japan. Second, only one off-site dietitian participated in our study. Since off-site dietitians have a limited presence at multiple schools, the degree to which they are able to influence the amount of food waste generated by any one school may differ substantially from the influence of on-site dietitians who interact daily with students, teachers and principals. Future studies should include a larger sample of on-site and off-site dietitians working in diverse school settings. Third, response bias and bias that can result from researcher engagement in the research process may have influenced our study findings. It is also possible, for example, that the school dietitians participating in our study selected classes with low levels of classroom waste for participant observation. To minimize overall bias, we triangulated our interview data with other sources of data and carried out a member-checking process to ensure the accuracy of the conclusions we drew. Fourth, our study was not exhaustive and did not consider how factors such as funding for school lunch programmes influence lunch waste. Such factors are important considerations when determining how US schools can adapt the strategies described in the current study given differences in how programmes are funded. For example, the primary source of revenue for the NSLP is reimbursements offered by the US federal government for meals served to students v. the stable and predictable funding provided by the shared contributions of families, the local government and the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

Conclusions

Our study highlights mechanisms through which lunch waste is minimized in Tokyo elementary schools. The holistic and context-specific model reflected in Japan’s school lunch programme may be difficult to implement in US schools. However, given the scale of the problem and its environmental, financial and public health consequences, it is urgent that we consider how US schools can adapt strategies that have successfully reduced school lunch waste in other countries. Japan offers a model to do so, even if we must borrow elements of it rather than adopting it in its entirety. Policy makers, school administrators, educators, and food and nutrition professionals all have a role to play in reducing lunch waste in US schools by changing social norms, educating students about the importance of food waste reduction, implementing environmental and policy changes, and creating meaningful opportunities for students to contribute to solving the problem. A global commitment to addressing food waste is necessary in order to support healthy diets and sustainable food systems(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken4) and schools are critical partners in this process.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the principals, school dietitians, teachers and students who were involved in this study, and Emi Yoshii, Elizabeth Svisco, Kyoko Hosoe, Mami Kikuchi, Akiko Aioke and Mio Robinson for their contributions to this research. Financial support: This work was supported by a Fulbright US Scholar Program Award and Portland State University. Funding agencies had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: B.T.I. designed the study, collected and analysed data, and led manuscript writing. R.A. designed the study, identified research participants, collected and analysed data, and drafted and revised the manuscript. C.B.S. analysed data and drafted and revised the manuscript. K.F. collected and analysed data and drafted and revised the manuscript. Each author has seen and approved the contents of the submitted manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the research ethics committee at Ochanomizu University. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001900380X