The development of community care has led to an increased demand for consultant psychiatrists specialising in learning disabilities. Their role has changed considerably (Reference LindseyLindsey, 2000) and recent policy documents have recommended further changes (Department of Health, 2001; Scottish Executive, 2000). The workload has increased due to a variety of factors, including advances in assessment and treatment, increased expectations of service users and carers, changes in role within multi-disciplinary teams, greater involvement in service development and management, and the dispersed nature of services. A survey of Scottish learning disability psychiatrists (Reference Smiley, Cooper and MillerSmiley et al, 2002) showed a wide range in the level of psychiatric staffing, the population served and the services available. A comparative review of the spend on learning disability health services across England (Reference Forsyth and WinterbottomForsyth & Winterbottom, 2002) has also shown considerable inequalities.

A recent postal survey (Reference Alexander, Regan and GangadharanAlexander et al, 2002), which asked a sample of 67 consultants to rate 10 potential roles on a scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree, showed that while all were clearly in agreement with their role in the assessment and treatment of mental illness, there was a greater range of response in relation to the other roles including behaviour problems, epilepsy, autism and forensic work. With such a range of potential roles, this field is particularly challenging (Middleton & Courtney, 2000). It requires knowledge and skills in all branches of psychiatry, and it needs to be applied to a population of patients who often have significant communication problems and a high degree of comorbidity. It also lacks coherent models of service provision due to rapidly-evolving policies, and variations in local circumstances and history of services (Reference Moss, Bouras and HoltMoss et al, 2000).

In-patient services now usually provide assessment, treatment and rehabilitation for those individuals with learning disability with the most severe and complex mental health needs. The Scottish Executive estimates that four such in-patient beds for adults are required per 100 000 population (Scottish Executive, 2000), although Day (Reference Day1993) reported the need for 30 per 100 000. This latter figure is more in line with the figure reported by Bailey & Cooper (Reference Bailey and Cooper1997) in their survey of provision in England and Wales. The Scottish survey (Reference Smiley, Cooper and MillerSmiley et al, 2002) showed that the individual consultants were responsible for a median of 3.7 assessment and treatment and 23 long-stay beds, but there was a wide range.

Children and adolescents with a learning disability, their families and their carers are a specific population with medical, social and psychological mental health needs that ought to be met by a competent and well-integrated service. Consultant psychiatrists in learning disability are providing that service in many areas of the country, but there little is known about the extent to which this is the case and the alternatives available, such as access to child and adolescent mental health services.

The many roles that are undertaken raises the issue of the relationship between learning disability psychiatry and other specialities, and also the NHS organisational framework within which it is best placed. Service reconfigurations have created many new opportunities for professional development (Reference O'DwyerO’Dwyer, 2000). Alexander et al (Reference Alexander, Regan and Gangadharan2002) found that the majority of the consultants surveyed agreed with integration within mental health trusts or specialist learning disability trusts. Only 33% were satisfied with the current management changes within their trusts, but 67% were satisfied overall with their jobs.

Method

In August 2000, a questionnaire was sent to all members on the mailing list of the Faculty for the Psychiatry of Learning Disability, including the 208 consultants. Regional representatives contacted and redistributed questionnaires to all non-responders. Replies were returned by post over a period of 6 months.

The questionnaire included both direct and openended questions covering the nature of employment, catchment areas, patterns of work, areas of expertise, and the positive and negative aspects of the service in which the consultant worked. Likert scales were used to assess areas of job satisfaction. Data were interpreted as total number of, or proportion of, respondents giving specific answers. Likert scales were viewed graphically and free text was subjected to a careful thematic analysis.

Findings

There were 136 respondents (74 male, 62 female), 132 of whom were in substantive posts. Seventy-eight (57%) had been appointed to their present post in the past 10 years. Sixty-four had single registration in the field of learning disability, 46 in one or more other specialities and 36 did not have registration in learning disability. Tables 1 and 2 show the numbers and percentages of respondents with sessional commitments in specific areas of psychiatric work and responsibilities for areas additional to routine psychiatric practice, including that with patients functioning outside the learning disability range.

Table 1. Respondent sessions in different areas of psychiatric work

| Area of work | Number of respondents (n=136) | (% of respondents) |

|---|---|---|

| Adult community learning disability | 112 | (82) |

| Adult in-patient learning disability | 91 | (67) |

| Child/adolescent community learning disability | 52 | (38) |

| Child/adolescent in-patient learning disability | 25 | (18) |

| Forensic learning disability | 41 | (30) |

| Management | 80 | (59) |

| Psychotherapy learning disability | 22 | (16) |

| Academic | 83 | (61) |

| Other branches of psychiatry1 | 37 | (27) |

Table 2. Respondents’ areas of work additional to routine learning disability psychiatric work

| Area of work | Number of respondents (n=136) | (% of respondents) |

|---|---|---|

| Low/borderline normal IQ | 104 | (76) |

| Epilepsy | 110 | (81) |

| Asperger/high-functioning autism | 93 | (68) |

| Acquired brain injury | 51 | (38) |

| Hospital resettlement | 64 | (47) |

| Rehabilitation | 87 | (64) |

| Liaison with general hospital | 94 | (69) |

| Teaching/advice to primary care | 63 | (46) |

The majority of respondents had access to specialist in-patient assessment and treatment facilities for patients with mild (65%) and severe (52%) learning disability, total bed numbers varied widely (1–100). Twenty-five per cent only had access to beds in general adult wards for patients with mild learning disability.

One hundred and sixteen respondents (85%) had problems with admitting, and the same number in discharging patients. Only 21 (15%) said that they had no problems with admission and even less (10; 7%) had no problems with discharging patients. Of the problems with admission, 40 respondents (29%) reported that this was due to insufficient in-patient beds and 49 (36%) due to problems with discharge. Problems with discharge were reported by 73 respondents (54%) to be due to lack of suitable community accommodation and 52 (38%) reported lack of funding for post-discharge care. Other problem areas described were poor staffing, lack of medical cover, problems with social services and lack of a commitment to deal with difficult patients.

Seventy respondents (51%) cared for adults only, 42 (31%) covered the full age range, 11 (8%) worked exclusively with children and adolescents and 6 (4%) worked only with adolescents and adults. Across the country, an approximately one-third split was reported in the provision of services for children and adolescents between paediatrics, child and adolescent psychiatry and learning disability psychiatry. Twelve respondents (9%) stated that they had no service in their area for this population.

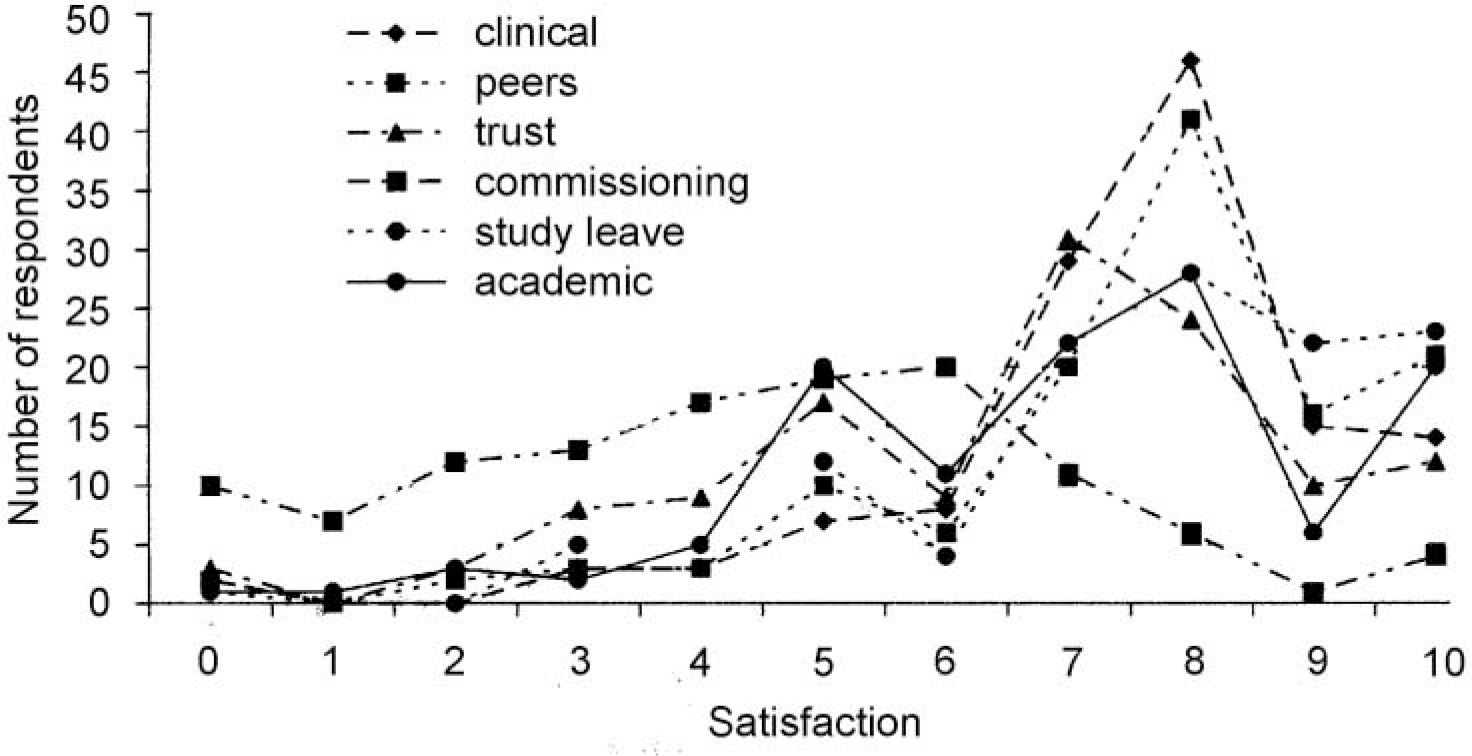

In the free text responses, 126 respondents cited positive aspects of the service, particularly professional relationships (52) and involvement with more specialist services, research and academic commitments (33). There were 123 comments expressing concerns about services, including insufficient and poor quality services (46), staff shortages and recruitment (26) and relationships with social services (14). Results of the Likert scale looking at job satisfaction are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Results of Likert scores of satisfaction for respondents in various areas of work.

Discussion

The 2000 College Census (Royal College Psychiatrists, 2001) identified 208 full-time and part-time filled substantive consultant posts in learning disability psychiatry in the UK. There were 136 respondents to the questionnaire, giving a response rate of 64%. It is possible that there is selection bias and that politicallymotivated individuals, or those with specific interest and time, were more likely to respond to the questionnaire. However, we believe that the sample is large enough to be broadly illustrative of the work and views of consultants in this field.

The large proportion of respondents registered in other specialities, with or without registration in learning disability psychiatry, may reflect the interesting range of skills required in this speciality. This is also shown in the many areas of work undertaken in addition to routine psychiatric work and the associated areas of clinical expertise including Asperger syndrome, epilepsy, acquired brain injury and the low or borderline normal IQ range. In addition, many were involved in liaison psychiatry and in providing teaching and advice to general practitioners. A large number also had sessions in academic or research posts. Alexander et al (Reference Alexander, Regan and Gangadharan2002) found a variation in the views regarding the appropriate roles and responsibilities of consultants.

Although total numbers of the population in hospitals with learning disabilities have gone down, it is evident that hospital resettlement is still ongoing as shown by the number with a rehabilitation role. The number with specific management sessions possibly reflects an interest among this consultant group in the wider aspects of service provision. Most consultants have access to in-patient beds for assessment and treatment, although the actual numbers are very disparate. Insufficient in-patient provision and problems discharging patients were major obstacles to admission. Overall, the high numbers reporting difficulties in this area, particularly lack of funding and after-care accommodation and the dearth of day care facilities, contribute to the impression countrywide of services with inadequate resources. Probably as a result, there are inconsistent and widely-variable patterns of service delivery. Therefore, although a report describing good practice has been published (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1996), there continue to be considerable problems in this area. Furthermore, the lack of appropriate beds is likely to lead to expensive placements outside the area (Reference O'BrienO’Brien, 1990), which goes against good practice recommendations (Reference MansellMansell, 1992).

Another disparity was in the availability of services for children and adolescents with learning disabilities. Only 11 consultants worked exclusively in this field, but over a third had some responsibility for children and/or adolescents. Countrywide, the provision of this service is split roughly equally between learning disability psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry and paediatrics and it is appalling that no service was available at all in 12 localities. Service availability in this area is clearly inadequate and inequitable, despite a report from the Royal College of Psychiatrists (1998) describing the services required by this population.

The high number of responses to the question on positive aspects of services is encouraging. The most commonly cited was quality of professional relationships, which suggests that good multi-disciplinary team working and support between colleagues is producing benefits. The other strong theme was involvement with more specialist services and the opportunity to develop areas of expertise. The availability of academic or research opportunities also appears to be very important for many. The quality and depth of services, as well as adequate staffing, were the most consistent concerns.

The good level of satisfaction with clinical work and peers is consistent with the answers regarding positive aspects of services where professional relationships and teamwork were most often cited. Respondents were also largely satisfied with other areas of work including their employing organisation, study leave, academic and teaching involvement and specialist interests. This perhaps suggests that where individual professional development is encouraged, satisfaction follows. A notable exception regarding satisfaction was commissioning and planning of services. This is similar to the findings of Alexander et al (Reference Alexander, Regan and Gangadharan2002) and compatible with the concerns mentioned earlier regarding staffing levels, range and quality of services. It perhaps illustrates that in areas where service provision is perceived to be inadequate, this has a significant impact on job satisfaction.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.