The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) provides nutritious foods, nutrition education, breast-feeding support and health care/social service referrals to approximately 8·3 million low-income pregnant and postpartum women, infants and children up to 5 years of age( Reference Oliveira and Frazao 1 ). Benefits are made available to WIC participants monthly in the form of different food packages for each participant stage (see Tables 1 and 2)( 2 ). In the USA, WIC is a central component of the federal food and nutrition safety net. Over 20 years of research has demonstrated the positive impact of WIC on nutrient adequacy, health outcomes, and healthy growth and development among participating women and children( Reference Tester, Leung and Crawford 3 – Reference Thomas, Kolasa and Zhang 7 ). Nevertheless, participation in the programme has continued to decline and retention of child participants is especially concerning( Reference Jacknowitz and Tiehen 8 ).

Table 1 Food packages provided to infants in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Adapted from the US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Supplemental Food Programs Division (2018)( 2 )

1 US fl. oz = 29·57 ml; 1 oz = 28·35 g.

Table 2 Food packages provided to children and women in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Adapted from the US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Supplemental Food Programs Division (2018)( 2 )

1 US fl. oz = 29·57 ml; 1 US qt = 946·35 ml; 1 oz = 28·35 g; 1 lb = 453·59 g.

* Allowable options for milk alternatives are cheese, soya beverage and tofu.

† At least one half of the total number of breakfast cereals on the State agency food list must be whole grain.

‡ Allowable options are wholegrain bread, whole-wheat pasta, brown rice, bulgur, oatmeal, wholegrain barley, soft corn or whole-wheat tortillas.

§ Allowable options for canned fish are light tuna, salmon, sardines and mackerel.

Since peaking in fiscal year 2010, the number of WIC participants has decreased by almost 10 %( Reference Jacknowitz and Tiehen 8 ). In 2014, WIC experienced the largest decrease since the programme’s inception( Reference Oliveira and Frazao 1 ). In 2011, the coverage rate (ratio of WIC participants compared with the eligible population) for children aged 1–4 years was 53·6 %, while the coverage rates for infants, pregnant women and postpartum women were 83·4, 69·5 and 76·0 % respectively( Reference Martinez-Schiferl, Zedlewski and Giannarelli 9 ).

The purpose of the present study was to gain an in-depth understanding of the factors that contribute to low-income caregivers’ perceived value of the benefits they receive from WIC. The study specifically targeted WIC caregivers of infants because the largest decline in participation occurs when children transition from the infant food package to the child food package, and evidence suggests that caregivers’ intention to leave may start in infancy( 10 ). Understanding caregivers’ lifestyles and experiences in their own words could help policy makers improve WIC and better inform efforts aimed at keeping children enrolled.

Methods

Parents/caregivers with infants aged 3–6 months enrolled in WIC were recruited at eight WIC agencies across the State of Illinois, USA, for a longitudinal study about WIC retention that included activities to improve client awareness of WIC benefits, improve staff/client interactions and improve image/understanding of WIC among health-care providers. Study sites were selected based on high and low child retention rates and were matched on demographic and caseload profiles. From 150 participants recruited at baseline, a sub-sample of participants (n 31) was recruited by a qualitative researcher experienced with WIC to participate in in-depth interviews from April 2015 to July 2016. Maximum variation sampling( Reference Patton 11 ) was employed to garner information from participants that varied by ethnicity, age, household composition, employment status, breast-feeding status and programme experience. Theoretical sampling continued and repeated until the data analysis reached saturation, when key emergent themes were no longer unique.

Guided by a constructivist approach( Reference Schwandt 12 ), interviews lasting about 1 h were conducted in private areas by the same qualitative researcher. Research questions within the semi-structured interview protocol (see the online supplementary material) were informed by prior research on the barriers and facilitators to using WIC services( 10 , Reference Uesugi, Porter and Reese 13 ) as well as dimensions described within the food choice literature( Reference Devine, Jastran and Jabs 14 , Reference Jabs, Devine and Bisogni 15 ).

Interviews were transcribed verbatim. Prior to coding, transcripts were read several times to obtain a clearer understanding of issues discussed within each interview. Each case was grouped according to interview site, ethnicity, infant feeding type (e.g. breast-fed v. formula-fed) and number of children using a software program for managing qualitative data (Atlas.ti version 8).

The constant comparative method( Reference Corbin and Strauss 16 ) was used to guide interview analysis. A list of codes and code groups was updated and maintained throughout analysis. Code agreement, categories and themes were finalized under the oversight of three researchers with expertise in nutrition, WIC and health equity research. To better understand the relationships between food preferences, perceived value of WIC and intention to keep child participants in the WIC programme, an inductive coding process was used to identify emergent themes. Codes were then queried via key words, like groupings, and other identifiers then compared within and between transcripts. Attention focused on emerging themes that were geography focused (e.g. urban v. rural), activity focused (critical incidents, crises, etc.) and time based (e.g. seasons, schedules, periods of child development, etc.)( Reference Patton 11 ). Themes were organized into a final conceptual framework which illustrated the barriers and contributors to the perceived value of WIC.

Inter-coder reliability was determined according to the procedures of Gough and Conner( Reference Gough and Conner 17 ). Two additional coders with backgrounds in public health completed code allocations, which were checked to assure a high level of correspondence (94 and 81 %, respectively). All coders came together to revise codes and themes according to their meaning until an acceptable consensus was reached (i.e. ≥95 % of quotations were allocated to the core themes). This was calculated using the joint probability of agreement method described by Thomas et al. ( Reference Thomas, Puig Ribera and Senye-Mir 18 ). Trustworthiness and data quality were evaluated using Lincoln and Guba’s criteria including prolonged engagement (on site at clinics throughout the course of the study), persistent observation (staff and client interactions), peer debriefing (reports and calls with the state agency and WIC site coordinators), dependability audits, as well as negative case study analysis( Reference Patton 11 ).

Results

Sample characteristics can be viewed in Table 3. The race/ethnicity and geographic locations of the sub-sample reflected those of the larger study at the time of data collection. Most participants (90 %) had one to three children; one participant had four, one had five, and one had seven children. Participants’ children’s ages ranged from 2 weeks to 17 years. All participants with more than one child had previous WIC experience with other children.

Table 3 Characteristics of the sample of low-income caregivers of children in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), from eight WIC clinics across Illinois, USA, who participated in interviews about WIC foods from April 2015 to July 2016 (n 31)

GED, General Educational Development; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

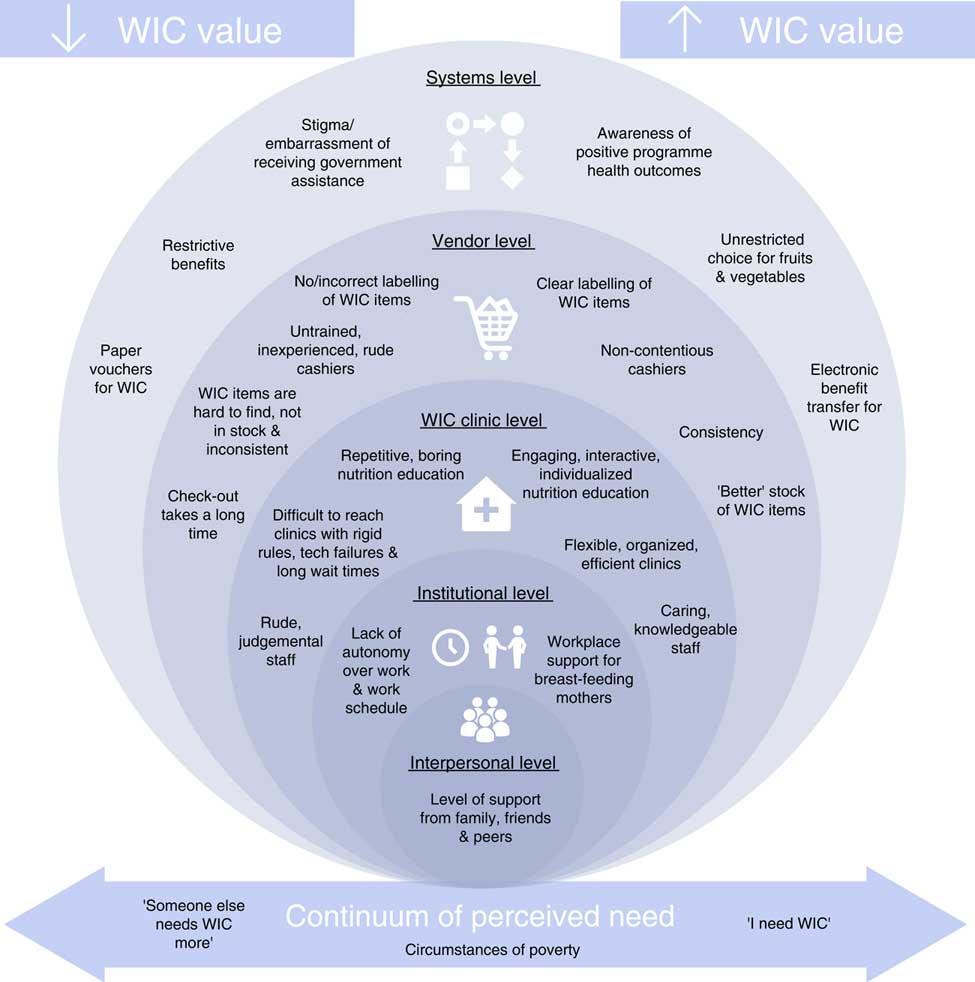

Several categories of codes overlapped into emergent themes that were organized to support the socio-ecological model( Reference McLeroy, Bibeau and Steckler 19 ) at the interpersonal, institutional, clinic, vendor and systems levels. These themes often existed along continua contributing to how WIC is valued, which transcended levels within the socio-ecological model. Constructs of hectic lifestyles, underemployment and varying levels of poverty demonstrated a spectrum of influence and meanings behind these values. Themes either increased or lowered the perceived value for each participant. Themes overlapped in participant interviews to the point of saturation; however, no participant group was completely homogeneous in the way caregivers valued WIC benefits. Value was not fixed for participants, but rather a rotating wheel of priorities in their food system. Organization of themes culminated into a final conceptual framework illustrated in Fig. 1, which reflects the factors influencing low-income caregivers’ perceived value of WIC.

Fig. 1 (colour online) Factors influencing low-income caregivers’ perceived value of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): a socio-ecological model

Interpersonal level themes

Formal and informal support systems such as family and friendship networks comprise the interpersonal level( Reference McLeroy, Bibeau and Steckler 19 ). Many caregivers faced stressors and support at this level which impacted their security and ability to remain in WIC:

‘I took a little bit of a break from WIC. Try to you know, to be a new mom. I re-joined WIC when I was pregnant with my first daughter. Then my ex-husband kicked me out of my own home. I was homeless for 9 months.’ (Caregiver aged 37 years)

Family, peers and social networks often influenced participants’ decision to enrol or remain in the programme:

‘At first it was really confusing ’cause I didn’t know what I was doing, but my mom kinda helped me with it. She had four kids too, so after a couple months, I got it and it was easy from there.’ (Caregiver aged 23 years)

Social support also influenced perceived value of WIC and the decision to breast-feed. Several mothers stated they initiated breast-feeding, but for various reasons (e.g. returning to work, latching issues, difficulty, inconvenience) relied on formula to feed their infants, thus making the infant package more valuable to them. The extra food offered to breast-feeding mothers was not a major contributor to the value of the programme when compared with the value of the infant package offered to their non-breast-feeding peers. Participants enjoyed the expanded food package they received as well as the supportive environment WIC provides; however, this was not what influenced their decision and ability to breast-feed:

‘I wanted to breast-feed before I even knew I was pregnant. I think it’s kind of a decision that you make. I feel like WIC does kind of push breast-feeding for young moms – and I think that when you’re working, it is harder. ’Cause I think, had I not had a good support system that probably would have been easier to just give him formula.’ (Caregiver aged 31 years)

Breast-feeding mothers echoed the formula-feeding mothers and spoke about the cost, time and inconvenience of breast-feeding. Working mothers talked about the difficulty of keeping up milk supply, leaking in front of co-workers, engorgement and finding time to pump.

The main difference between those who continued breast-feeding and those using formula was the level of available support. Breast-feeding mothers tended to have affordable or free help with childcare, work environments that were flexible with scheduling, and social networks that encouraged breast-feeding.

Institutional level themes

Institutional level factors at workplaces or places with organizational characteristics, such as the WIC clinics and vendors, also influenced the perceived value of WIC. One mother described how grateful she was for WIC because she could only breast-feed for 3 months due to her work environment. She was written up for leaving to pump outside designated break times. She was aware of her rights but prioritized keeping her job:

‘I know that there are [laws to support breast-feeding] but I didn’t wanna have any discrepancies with the supervisor or the manager. You have to work. It’s like a decent paying job. It pays twice as much as the minimum wage. I mean, I’m grateful for it.’ (Caregiver aged 26 years)

Several participants held little to no autonomy over their schedules, which affected their home life and ability to come to WIC appointments even if they valued the programme. Several participants talked about needing to work two jobs, jeopardizing sleep and time with their children. Those who were able to fit WIC into their schedule would use their limited time off only if they were in great need:

‘You’re like a robot – you don’t have that much time for yourself. I’ve gotten to this life where you’re always on a schedule – from school to home to work to eat and sleep. That’s it.’ (Caregiver aged 21 years)

WIC clinic level themes

Participants voiced that ‘WIC is more than food’. Many participants valued the education and health benefits they received from WIC. Individualized counselling and referrals to other services were appreciated, as was tracking children’s growth and development at WIC:

‘I think that when they ask, “Are you in a safe environment?” that’s valuable because there’s people that are not safe; they can refer you to people that can help you. I think that the weight and the height is very helpful as well because in between times of doctor’s visits, your baby’s growing and you be curious if your baby’s on the right track.’ (Caregiver aged 31 years)

Clinics that were organized, engaging, communicative, and had staff who were flexible and amicable were valued more. Participants valued staff who ‘worked with them’ if they needed to reschedule, were running late or couldn’t navigate the system. Participants reflected positively on individual staff members who made a personal connection with them:

‘His name was the “Milk-Man” ’cause he gave out WIC coupons for us to get milk. He was also a comedian, he would make us laugh, you know, he was down to earth, and I guess when he left, a lot of people left.’ (Caregiver aged 26 years)

Despite the positive clinic level influences, the way the WIC programme is administered sometimes negatively influenced programme value. Although some caregivers valued WIC nutrition education, others felt it was a waste of time, not useful, repetitive, outdated and a necessary burden to get their vouchers. Participants wanted curricula that were interactive, fun and ‘more than just recipes’:

‘I feel like it can be more beneficial than saying like, “Oh make a smoothie with peanut butter!” There’s other ways to do it. Like there could be taste tests. Like having the farmers come in to show it, or maybe – I don’t know, just something to make it exciting, instead of making it seem like this is what I have to do to get my vouchers.’ (Caregiver aged 28 years)

Certain clinics were described as disorganized and frustrating for participants who would make great efforts to get to WIC only to find the computer system down and they couldn’t complete their appointment. Many participants found it very difficult to reach a staff member on the phone if they needed to schedule or get into the system:

‘I’m trying to get both of my children [re]enrolled in WIC. The WIC office got it all messed up. So, I try to do what I can. I always tell people, when you got these WIC appointments, try to make it because nowadays you don’t get another appointment for three to four weeks.’ (Caregiver aged 40 years)

Some clinics held walk-in hours, but this didn’t seem to solve the wait-time issue according to participants. At certain clinics, participants experienced rudeness or judgement from staff members. Participants also encountered staff they felt were combative with them about their paperwork and documentation:

‘Sometimes you wait over an hour. Sometimes two to three hours. Maybe if they had more workers? Some people will be there to work, but they don’t wanna work, or they will take they sweet time because they know they can. They know the people who are sitting there, are going to wait, and that’s where I see a big problem. They feel like they can take they sweet time because you need the stuff. A lot of people get fed up with that. I ain’t got to wait, I’ll just go buy it.’ (Caregiver aged 27 years)

Vendor level themes

Negative experiences shopping for food benefits made it difficult to value WIC. Participants mentioned incorrect labelling and inconsistency of WIC-approved foods. Confusion over correct sizes and types of eligible items caused a great deal of frustration, leaving benefits unredeemed. Checking out with WIC vouchers was time-consuming whether participants had shopping issues or not. Participants described untrained cashiers and the cumbersome nature of the check-out process, which embarrassed those trying to redeem food for their family. Strategies to manage difficulties at the store involved apologizing to other customers in the line ahead of time as well as learning which cashiers to go to or avoid:

‘When you go to the grocery store, it’s like you’re already causing a big ol’ hold up in the line because they gotta get right up on the coupon, they gotta check your signature, so it’s like you hear this constant – like the from people “[sigh], it’s the WIC lane”. I tell people up front, look, I have WIC, I’m sorry.’ (Caregiver aged 36 years)

Two participants mentioned they were more comfortable with younger cashiers because they were less contentious. Some participants came prepared with WIC food lists and advocated for themselves. Others would separate their WIC items out or only use one voucher at a time, so they wouldn’t hold up the line. Selective shopping was employed to choose stores that had better items in stock or were deemed easier for redeeming WIC foods.

Systems level themes

Systems level factors include relationships across networks, organizations and public policies( Reference McLeroy, Bibeau and Steckler 19 ). Other programme use influenced the perceived value of WIC. Participants who received benefits through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) could easily compare programmes. For most participants, SNAP benefits far exceeded their WIC benefits (in dollars), were easier to use and offered less restriction. SNAP benefits could be purchased with an electronic benefit transfer card, whereas WIC vouchers could be difficult and stigmatizing to use and it took a long time to print/pick-up at the WIC office according to participants:

‘Well, I could tell you straight up that the food stamps are much more convenient. They’re also faster because you just scan your card and you can use your cash or your food stamps on the one card.’ (Caregiver aged 37 years)

Although participants enjoyed the expanded food choice SNAP offers, many were aware of the health-related differences between the two programmes:

‘With WIC, since they won’t let you take just anything, you will stick to the healthy. Without WIC, you would just choose other things – maybe not so healthy. When you have WIC, it’s kind of like a strict thing where you have to eat healthy. I think that’s the good thing about it.’ (Caregiver aged 21 years)

Despite certain preferences for SNAP, many caregivers still valued WIC because, for some families, ‘SNAP is not enough’. Many participants identified the ‘end of the month’ as a time of struggle when SNAP benefits ran out. Alternatively, some participants fell in the ‘donut hole of eligibility’ where their household income was not low enough to be eligible for SNAP and WIC was the only help they received.

Stigma of using government assistance programmes was a theme throughout the interviews and made WIC food packages less valuable. One participant was quite conflicted about doing what was right for her child:

‘I submitted all my information for WIC and I had like this weird – “Am I doing the right thing for my baby?” I didn’t want to be another Black woman in the system! And I’m like, I’m educated! I shouldn’t be doing this! But it’s good for your baby, so that conflict was in there. My degree was in education, so I always remember the countless stories about the single mom and she’s having a hard time feeding her children. I’m like, that’s not the case! I just want the proper nutrition for my baby! Do I want to fulfil that stereotype?’ (Caregiver aged 27 years)

Others took a ‘tough skin’ approach and maintained that other people’s opinions didn’t come before their children’s health. Many participants dismissed the ignorance and rationalized that those who caused this stigma did not understand the programme, the eligibility requirements or the societal benefits WIC provides. All participants that referenced stigma were from non-urban clinics. Those who were able to rationalize against the stigma perceived WIC as more valuable than those who were more affected by the stigma or held stigmatizing beliefs themselves.

Resoundingly, participants talked about the importance of having choice. Choices in WIC made the food packages more valuable, but participants did not fail to mention that ‘WIC is restrictive’. Many felt restricted by the WIC food options yet pointed out how much they enjoy the flexibility that accompanies the fruit and vegetable cash vouchers. Every participant either wished she had more autonomy within the programme or vocalized that she had no choice and that’s ‘how it is’. Lack of choice in the programme led to unredeemed vouchers, waste and low self-esteem:

‘They should have the option to sometimes get the things that they want to. If you don’t give families options, it kinda tears their self-esteem down. They say when you cook from the heart, your meals come out great. Sometimes when you’re angry or you trying to fast cook, then you might mess a meal up. I generally cook from the heart, so you know – it’s like soul into the food. So it’s just like when I go and pick out the food that I want to cook, I want to feel love coming from the food.’ (Caregiver aged 35 years)

Themes that influenced the perceived value of WIC along a continuum

Certain themes overlapped several levels of the socio-ecological model, existing along a continuum. The continuum of perceived need influenced how families valued WIC food benefits. Feelings of entrapment and hopelessness seeped through participants’ descriptions of their neighbourhoods, which made WIC less of a priority:

‘I hate it here to be honest. I’d rather go live in friggin’ Egypt or something than live here. I don’t know if you’ve heard this from anybody else or not, but everybody says they want to leave so bad but they can’t. Like they don’t know what’s stopping ’em but they can’t. That’s how I feel about it, but ’cause I really want to move, I really want to go somewhere better, but then I think, it’s like can’t go. What are you gonna do?’ (Caregiver aged 23 years)

Lower perceived value of the food packages for children was compounded by other economic, social and environmental barriers:

‘I think it’s just worth it for the baby [formula] ’cause you need it. You need the help. It is worth it for the kids, but I just don’t wanna deal with it. I don’t got no patience for them kids. But if I could bring – like if I bring one child, like my baby, I can just bring him and no problem, but so – I just took ’em all off [WIC].’ (Caregiver aged 28 years, four children eligible for WIC, only one enrolled)

There also seemed to be a notion among some participants that they should leave WIC because others are in greater need. Caregivers perceived themselves to be ‘taking someone’s spot’. This was a more common thread for caregivers living in non-urban areas, where taking care of one’s family independent of government help seemed to be a source of pride and receiving benefits when one can ‘afford it’ was deemed unacceptable. One participant described her perception that the families who stayed in WIC were often those who were ‘really struggling’ and those who left were able to ‘get by ok’. Several participants claimed they ‘went through the hassle’ of attending WIC appointments because they needed the help.

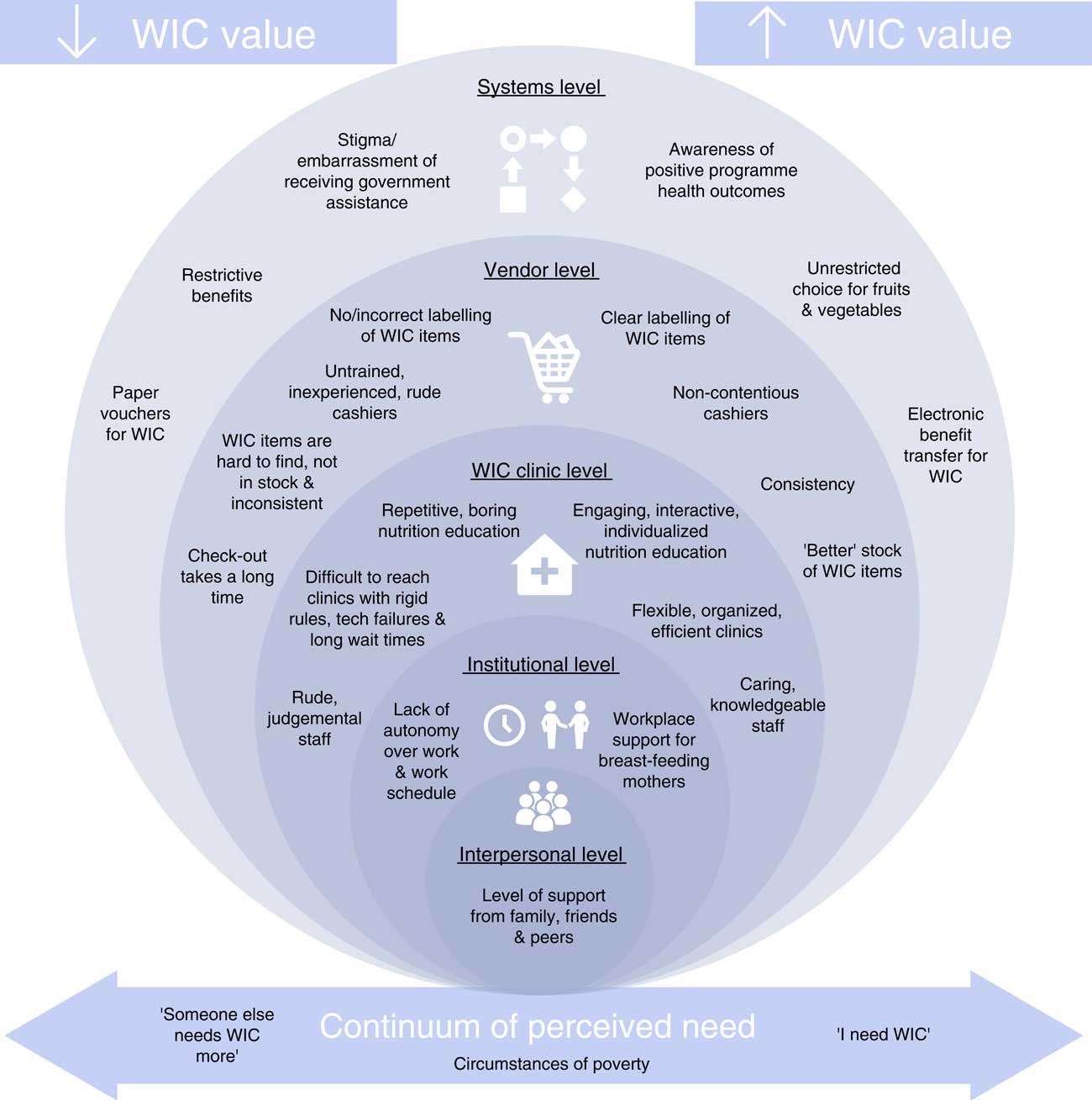

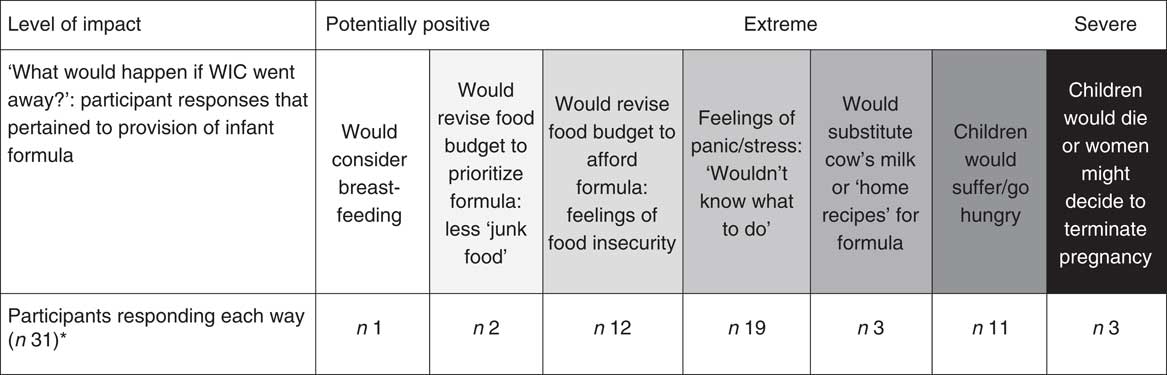

The perceived value of infant formula also impacted families along a continuum (Fig. 2). Similar to the WIC programme nationwide, most of the participants in the present study fed their infants formula, and infant formula provision was strongly valued in the study because of its expense and was emphasized as the most important item in WIC for many participants( Reference Weber, Uesugi and Greene 20 ). Participants were able to quantify exactly how much WIC saves and stated they would have had to resort to extreme measures to feed their infants if WIC did not provide free formula. Only one participant stated that she would have considered breast-feeding if WIC went away. Many participants mentioned they could use SNAP benefits for formula but recognized that price of formula would drain that resource quickly:

‘If WIC went away – Oh! My shopping would only be arranged like for formula. I think it will go to a lot less of what we wanted.’ (Caregiver aged 21 years)

Fig. 2 Perceived value of infant formula supplied by the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) among low-income caregivers from eight WIC clinics across Illinois, USA, April 2015 to July 2016. *Responses are not mutually exclusive

Some participants mentioned infants would be introduced to cow’s milk before 1 year of age if formula was not provided:

‘My brother had to start giving his baby whole milk before the [recommended] time. I think it’s like 2 year, but he had to give her that at 7 months because [formula is] so expensive. I think if WIC went away, a lot of moms wouldn’t be able to afford Enfamil – but that would be bad. I know that this programme really helps, like who has money – I know that I’m like young – I don’t have a good job to afford stuff.’ (Caregiver aged 22 years)

One participant stated she would make her own baby formula if she didn’t have WIC:

‘I don’t know the ingredients or anything, but I’ve seen YouTube videos [about formula home recipes]. If I didn’t have WIC, I would try that out because it’s expensive.’ (Caregiver aged 21 years)

Although about a third of the participants in the present study breast-fed their infants, their perceived value of formula provided by WIC was not lowered. Some breast-feeding mothers needed to use formula with previous children or knew other families who benefited from the formula WIC provides:

‘[If WIC went away] a lot of kids’d go hungry, cause a lot of kids is getting the formula – that’s very expensive. Again it wouldn’t be in my case because, it [breast milk] is coming from me, my body. I can see it even in my sister’s case – I mean it [formula] really help. She got three kids so […].’ (Caregiver aged 31 years)

Participants said many children would suffer if WIC went away. One participant illustrated this bleak situation:

‘I think if WIC went away, to be brutally honest, and I know people won’t like my answer, a lot of girls would probably get abortions ’cause they know they wouldn’t be able to afford it. So instead of WIC being crowded, the County [Hospital] would be crowded because they give $75 abortions. And that’s probably their only option. If you don’t have the money, the support from a spouse, or family support – period – you would not be able to afford a kid. $200 a month for an average amount of formula for a baby […] Sorry, you never know where the teenagers are gonna go to when the baby is crying and they don’t have the money to get milk for that baby, you don’t know what they’re gonna do.’ (Caregiver aged 26 years)

Discussion and conclusions

Following the socio-ecological framework, the present study identified factors that influenced low-income WIC caregivers’ perceived value of the federal nutrition programme. At the interpersonal and institutional levels, availability of support was a theme that influenced participants’ success with breast-feeding and ability to value WIC services. WIC participants in the current study considered breast-feeding to be beneficial, but multiple barriers existed, especially for working mothers. A qualitative study with both WIC and non-WIC mothers aimed at understanding the cultural factors affecting a mother’s decision to breast- or formula-feed revealed similar results in that participants agreed that breast-feeding is best, but barriers to breast-feeding leading to formula use were inevitable in some circumstances( Reference Fischer and Olson 21 ). As promotion efforts increase, breast-feeding rates in WIC have risen steadily( 22 ); however, most participants rely on formula. In a previous study using a socio-ecological perspective of barriers and contributors to breast-feeding among WIC mothers, breast-feeding was significantly related to employment status in that 55 % of mothers who breast-fed for 6 months were unemployed, 30 % worked part-time, while 15 % were employed full-time( Reference Dunn, Kalich and Fedrizzi 23 ).

Clinic level factors that made the programme less valuable for participants in the present study included rigid rules, long wait times, contact difficulties, poor staff attitudes and boring, redundant nutrition education. Woelfel et al. found similar clinic level barriers to WIC services among surveyed WIC participants( Reference Woelfel, Abusabha and Pruzek 24 ). Clinics whose services were perceived as valuable tended to follow the principles of participant-centred services( Reference Deehy, Hoger and Kallio 25 ), which have been documented to increase patient/client WIC usefulness( Reference Isbell, Seth and Atwood 26 ).

Several vendor level factors influenced the perceived value of WIC. Other studies have also revealed that difficulties while shopping have contributed to barriers to and dissatisfaction with using WIC( Reference Woelfel, Abusabha and Pruzek 24 , Reference Ritchie, Whaley and Crocker 27 ). WIC needs to work with vendors more closely to develop better cashier training and labelling systems. Strategies that provide clear, consistent, easy and correct solutions for WIC shopping must also be developed. WIC has required states to switch over to electronic benefit transfer by 2020( 28 ), which should alleviate several barriers for participants and vendors alike( Reference Oliveira and Frazao 1 ).

Restrictions on food choice, preferring SNAP over WIC, and stigma of using government assistance decreased the value of WIC for participants at the systems level. Although participants in the present study stated SNAP is easier to use and allows more choice, they were aware there is no restriction on SNAP foods based on health. Pomeranz and Chriqui have reviewed several factors related to revising the SNAP programme to be more like the WIC programme with respect to the ability to define and differentiate products that meet health guidelines( Reference Pomeranz and Chriqui 29 ).

Autonomy of choice is key to how participants perceive the value of WIC food packages v. the barriers to using the programme. Although WIC continues to revise its packages, more should be done to improve the choices in WIC that meet the recommendations put forth by current nutrition science. For example, the 2009 introduction of cash value vouchers for fruits and vegetables in WIC, which provides some level of choice, improved participants’ view of the programme in the present and other studies( Reference Adedze, Chapman-Novakofski and Witz 30 , Reference Lawrence and Barker 31 ). Further expansion of choices would likely increase the perceived value of the WIC food packages.

In the present study, circumstances of poverty created barriers to obtaining WIC services but also drove needy families to value WIC more. In a study examining the food purchasing behaviour of low-income women, circumstances of poverty reduced the odds of purchasing both healthy and unhealthy food groups( Reference Bertmann, Barroso and Ohri-Vachaspati 32 ). Previous studies have also found that parents with limited resources report having feelings of less control over their health outcomes( Reference Kim, Whaley and Gradziel 33 ). Some participants in the current study described being ‘appreciative of any help given’; however, appreciation sometimes surfaced in self-effacing behaviour such as being reluctant to constructively criticize a programme whose food choices were not useful to their households, stating ‘beggars can’t be choosers’. Other studies have found that lower self-esteem and self-efficacy are linked to poorer health behaviours related to eating( Reference Dammann and Smith 34 ); therefore, increased freedom of choice and variety in the programme could lead to heightened participant empowerment and improved health outcomes.

In conclusion, WIC helps many families, but factors at multiple levels decrease the perceived value of the programme. It is important that practitioners, health professionals and researchers consider circumstances of poverty, level of social support and stigma when delivering care and designing interventions to keep eligible participants enrolled in federal nutrition programmes. Future recommendations must consider the expectations of low-income families who desire choice, dignity and efficiency in today’s more technologically advanced society.

The current study is not without limitations. Care was taken to conduct the interviews privately and participants were informed that their responses would not affect their WIC participation in any way; however, certain participants may have been unwilling to speak negatively about the programme within clinic walls. All interview participants spoke English fluently; however, four participants spoke languages other than English at home. Conversing in participants’ secondary language might introduce language barriers and potentially influence interview interactions. The researchers were unable to recruit those who had already left WIC since all participants were recruited from a larger study that required programme participation at baseline. To partially remedy this, participants with previously enrolled children who had left the programme before the age of 5 years were recruited. Because WIC is administered at the state and local levels, all results of the study may not be empirically generalizable to participants, clinics and vendors in other states or at the national level.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the Illinois WIC staff and clinic site coordinators for sharing their space and being so accommodating during the data collection phase. They would also like to acknowledge the most important voices, those who cannot be named: the caregivers who allowed a researcher to ask about their lives and record them as they told their stories. Financial support: This research was funded by a grant from the Illinois Department of Human Services (grant number 11AQ0001). The Illinois Department of Human Services had no role in the design, analysis of writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: S.J.W. was responsible for development of the interview protocol, participant recruitment, participant interviewing, code development, analysis of interviews, conceptualization of the final model, and writing the manuscript. A.O.-Y. and N.C. oversaw development of the interview protocol, coding, analysis of interviews, and contributed final edits to the manuscript. J.W. assisted with participant recruitment, project coordination and writing/editing of the manuscript. S.B. and L.R. were instrumental throughout the beginning stages of the study regarding cooperation and oversight of the WIC agency sites; they also served during the peer debriefing process of this study. All authors have read and approved the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003336