1 Introduction

Throughout this paper, unless specified, M denotes a d-dimensional closed Riemannian manifold and

![]() $\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

the set of all

$\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

the set of all

![]() $C^1$

-maps from M into itself endowed with the

$C^1$

-maps from M into itself endowed with the

![]() $C^1$

-topology. The elements of

$C^1$

-topology. The elements of

![]() $\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

are called endomorphisms. Some of them exhibit critical points, that is, points on which the derivative is not a linear isomorphism; and the other ones, endomorphisms without critical points, are local diffeomorphisms or diffeomorphisms.

$\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

are called endomorphisms. Some of them exhibit critical points, that is, points on which the derivative is not a linear isomorphism; and the other ones, endomorphisms without critical points, are local diffeomorphisms or diffeomorphisms.

An endomorphism f is said to be robustly transitive if there exists a neighborhood

![]() $\mathcal {U}_f$

of f in

$\mathcal {U}_f$

of f in

![]() $\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

such that every

$\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

such that every

![]() $g \in \mathcal {U}_f$

is transitive, where transitive means the existence of a dense forward orbit.

$g \in \mathcal {U}_f$

is transitive, where transitive means the existence of a dense forward orbit.

It should be pointed out that we are actually defining

![]() $C^1$

robust transitivity. The

$C^1$

robust transitivity. The

![]() $C^r$

robust transitivity could also be defined using the

$C^r$

robust transitivity could also be defined using the

![]() $C^r$

-topology. Our approach cannot be extended for

$C^r$

-topology. Our approach cannot be extended for

![]() $C^r$

robust transitivity since many of the techniques used here do not work in

$C^r$

robust transitivity since many of the techniques used here do not work in

![]() $C^r$

-topology and, in [Reference Iglesias and Portela15], an example is constructed of a

$C^r$

-topology and, in [Reference Iglesias and Portela15], an example is constructed of a

![]() $C^2$

-robustly transitive endomorphism which is not

$C^2$

-robustly transitive endomorphism which is not

![]() $C^1$

-robustly transitive.

$C^1$

-robustly transitive.

The main purpose of this paper is to show that dominated splitting is a necessary condition for the existence of robustly transitive endomorphisms displaying critical points. Concretely, we prove the following result.

Theorem A. Every robustly transitive endomorphism displaying critical points admits a non-trivial dominated splitting.

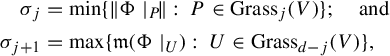

An endomorphism f admits non-trivial dominated splitting of index

![]() $\kappa $

if for every orbit

$\kappa $

if for every orbit

![]() $(x_i)_i$

, that is, a sequence of points

$(x_i)_i$

, that is, a sequence of points

![]() $(x_i)_i$

in M such that

$(x_i)_i$

in M such that

![]() $f(x_{i})=x_{i+1}$

for each

$f(x_{i})=x_{i+1}$

for each

![]() $i \in \mathbb {Z}$

, there are two non-trivial families

$i \in \mathbb {Z}$

, there are two non-trivial families

![]() $(E(x_i))_i$

and

$(E(x_i))_i$

and

![]() $(F(x_i))_i$

of

$(F(x_i))_i$

of

![]() $\kappa $

and

$\kappa $

and

![]() $(d-\kappa )$

-dimensional subspaces, respectively, satisfying the following:

$(d-\kappa )$

-dimensional subspaces, respectively, satisfying the following:

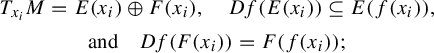

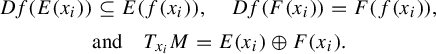

Invariant splitting. For each

![]() $i \in \mathbb {Z}$

, one has that

$i \in \mathbb {Z}$

, one has that

$$ \begin{align*} &T_{x_i}M=E(x_i)\oplus F(x_i), \quad Df(E(x_i)) \subseteq E(f(x_i)), \\ & \qquad\ \qquad \text{and}\quad Df(F(x_i))=F(f(x_i)); \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} &T_{x_i}M=E(x_i)\oplus F(x_i), \quad Df(E(x_i)) \subseteq E(f(x_i)), \\ & \qquad\ \qquad \text{and}\quad Df(F(x_i))=F(f(x_i)); \end{align*} $$

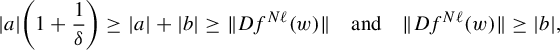

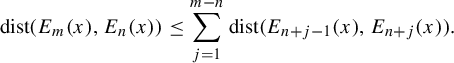

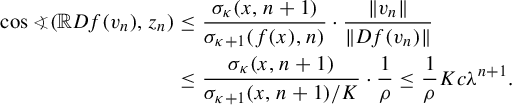

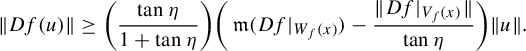

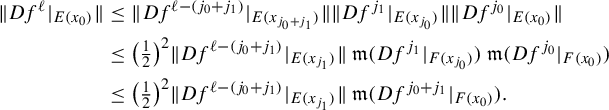

Domination property. There is an integer

![]() $\ell>0$

independent of any orbit such that

$\ell>0$

independent of any orbit such that

for every unit vectors

![]() $u \in E(x_i)$

and

$u \in E(x_i)$

and

![]() $v \in F(x_i)$

.

$v \in F(x_i)$

.

We will sometimes abuse notation and call the families of subspaces by E and F subbundles (cf. Remark 2.1). Further, we denote the domination property by

![]() $E\prec F$

or

$E\prec F$

or

![]() $E\prec _{\ell } F$

if we want to emphasize the role of

$E\prec _{\ell } F$

if we want to emphasize the role of

![]() $\ell $

. See §2 for further details about dominated splitting.

$\ell $

. See §2 for further details about dominated splitting.

The authors believe that, in general, robustly transitive endomorphisms displaying critical points require more than just dominated splitting. It is feasible that the dominated splitting

![]() $E\oplus F$

provided by Theorem A admits the finest dominated splitting such as

$E\oplus F$

provided by Theorem A admits the finest dominated splitting such as

![]() $E\oplus _{i=1}^k{F_i}$

where the derivative

$E\oplus _{i=1}^k{F_i}$

where the derivative

![]() $Df$

restricted to the extremal subbundle

$Df$

restricted to the extremal subbundle

![]() $F_k$

is volume expanding. (

$F_k$

is volume expanding. (

![]() $E_1\oplus \cdots \oplus E_k$

is the finest dominated splitting if

$E_1\oplus \cdots \oplus E_k$

is the finest dominated splitting if

![]() $E_1\prec E_2 \prec \cdots \prec E_k$

and none of the invariant subbundle

$E_1\prec E_2 \prec \cdots \prec E_k$

and none of the invariant subbundle

![]() $E_i$

admits a dominated splitting.) It was proved for a surface endomorphism in [Reference Lizana and Ranter17]. For higher dimension, it would be a similar result as that obtained for diffeomorphisms in [Reference Bonatti, Díaz and Pujals8] which states, in [Reference Bonatti, Díaz and Pujals8, Theorem 4], that every

$E_i$

admits a dominated splitting.) It was proved for a surface endomorphism in [Reference Lizana and Ranter17]. For higher dimension, it would be a similar result as that obtained for diffeomorphisms in [Reference Bonatti, Díaz and Pujals8] which states, in [Reference Bonatti, Díaz and Pujals8, Theorem 4], that every

![]() $C^1$

-robustly transitive diffeomorphism admits a finest dominated splitting such that the derivative

$C^1$

-robustly transitive diffeomorphism admits a finest dominated splitting such that the derivative

![]() $Df$

restricted to the extremal subbundles are volume contracting and volume expanding, respectively. See §1.1 for further discussion.

$Df$

restricted to the extremal subbundles are volume contracting and volume expanding, respectively. See §1.1 for further discussion.

As a consequence of the main result, we obtain the following topological obstruction. The proof is in §3.

Corollary 1.1. Even-dimensional spheres do not admit robustly transitive endomorphisms.

Note that the existence of robustly transitive diffeomorphisms in

![]() $S^3$

is a well-known open problem, and a negative answer is expected (see e.g. [Reference Díaz, Pujals and Ures11]). It makes sense to ask if examples of robustly transitive endomorphisms in

$S^3$

is a well-known open problem, and a negative answer is expected (see e.g. [Reference Díaz, Pujals and Ures11]). It makes sense to ask if examples of robustly transitive endomorphisms in

![]() $S^3$

may exist, while we expect this question to be difficult.

$S^3$

may exist, while we expect this question to be difficult.

We introduce now the following result that will be useful to prove Theorem A.

Theorem B. Let

![]() $f_0$

be a robustly transitive endomorphism displaying critical points and a neighborhood

$f_0$

be a robustly transitive endomorphism displaying critical points and a neighborhood

![]() $\mathcal {U}_0$

of

$\mathcal {U}_0$

of

![]() $f_0$

in

$f_0$

in

![]() $\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

such that every f in

$\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

such that every f in

![]() $\mathcal {U}_0$

is transitive. Then, there exist an integer

$\mathcal {U}_0$

is transitive. Then, there exist an integer

![]() $\ell \geq 1$

, a number

$\ell \geq 1$

, a number

![]() $\alpha>0$

, and subset

$\alpha>0$

, and subset

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

of

$\mathcal {F}$

of

![]() $\mathcal {U}_0$

such that the following hold:

$\mathcal {U}_0$

such that the following hold:

-

(a)

$f_0$

is accumulated by the endomorphisms in

$f_0$

is accumulated by the endomorphisms in

$\mathcal {F}$

; and

$\mathcal {F}$

; and -

(b) every

$f \in \mathcal {F}$

admits a dominated splitting

$f \in \mathcal {F}$

admits a dominated splitting

$E\oplus F$

such that

$E\oplus F$

such that

$E\prec _{\ell } F$

and the angle between E and F is greater than

$E\prec _{\ell } F$

and the angle between E and F is greater than

$\alpha $

. (It means that

$\alpha $

. (It means that  , for all vectors

, for all vectors

$u \in E(x_i),v \in F(x_i),$

for each

$u \in E(x_i),v \in F(x_i),$

for each

$x_i$

along the orbit

$x_i$

along the orbit

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda _f$

. For details, see §2.)

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda _f$

. For details, see §2.)

Theorem B implies uniformity of the dominated splitting for endomorphisms in

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

which will allow us, since

$\mathcal {F}$

which will allow us, since

![]() $f_0$

is accumulated by

$f_0$

is accumulated by

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

, to extend the dominated splitting to

$\mathcal {F}$

, to extend the dominated splitting to

![]() $f_0$

.

$f_0$

.

1.1 A brief history of robust transitivity

Robust transitivity has been well studied in the diffeomorphism context. The first examples were given by Shub on

![]() $\mathbb {T}^4$

in [Reference Shub and Chillingworth25] and by Mañé on

$\mathbb {T}^4$

in [Reference Shub and Chillingworth25] and by Mañé on

![]() $\mathbb {T}^3$

in [Reference Mañé19], which have an underlying structure weaker than hyperbolic, known as partially hyperbolic. However, Mañé proved for surface diffeomorphisms in [Reference Mañé20] that robust transitivity implies hyperbolicity and, in particular, the only surface that admits such systems is the torus,

$\mathbb {T}^3$

in [Reference Mañé19], which have an underlying structure weaker than hyperbolic, known as partially hyperbolic. However, Mañé proved for surface diffeomorphisms in [Reference Mañé20] that robust transitivity implies hyperbolicity and, in particular, the only surface that admits such systems is the torus,

![]() $\mathbb {T}^2$

.

$\mathbb {T}^2$

.

Bonatti and Díaz, in [Reference Bonatti and Díaz7], construct a powerful geometric tool (called a blender) to produce robustly transitive partially hyperbolic diffeomorphisms. Later, in [Reference Bonatti and Viana9], Bonatti and Viana construct the first examples of robustly transitive diffeomorphisms with dominated splitting which are not partially hyperbolic. In [Reference Bonatti, Díaz and Pujals8, Reference Díaz, Pujals and Ures11], Bonatti et al prove for a diffeomorphism on three- and higher-dimensional manifolds that robust transitivity requires some weak form of hyperbolicity.

In view of this, a natural question arises. In general, do robustly transitive endomorphisms require some weak form of hyperbolicty?

In the local diffeomorphisms scenario, there are several advances. Based on the examples of robustly transitive diffeomorphisms, robustly transitive non-expanding endomorphisms were constructed. In [Reference Lizana and Pujals16], necessary and sufficient conditions for robustly transitive local diffeomorphisms were obtained. In particular, it is not necessary any weak form of hyperbolicity for the existence of a robustly transitive local diffeomorphism; a trivial example is an expanding linear endomorphism with complex eigenvalues, which does not admit a dominated splitting. That result shows a difference between the diffeomorphisms and local diffeomorphisms setting. We note however that one can think of an endomorphism as having a strong stable bundle consisting on pre-orbits, and with this point of view, the results bear a closer analogy to those of diffeomorphisms.

In the endomorphisms displaying a critical points setting, the first examples were given in [Reference Berger and Rovella3, Reference Iglesias, Lizana and Portela14]. Although these examples exhibit some form of weak hyperbolicity and are homotopic to a hyperbolic linear endomorphism on

![]() $\mathbb {T}^2$

, any result about necessary conditions was established only recently. In [Reference Lizana and Ranter17], it was proved for surface endomorphisms that a weak form of hyperbolicity is needed for robust transitivity, so-called partial hyperbolicity. Furthermore, it was also proved that only the Torus and the Klein bottle support a robustly transitive endomorphism exhibiting critical points; and that the action of such a map on the first homology group has at least an eigenvalue with modulus greater than one. Later, new classes of examples of robustly transitive endomorphisms were given in [Reference Lizana and Ranter18]. The examples are homotopic to an expanding linear endomorphism on the torus or the Klein bottle; and an example of a robustly transitive endomorphism of zero degree. In higher dimension, the first examples of robustly transitive endomorphisms displaying critical points were constructed only recently in [Reference Morelli22].

$\mathbb {T}^2$

, any result about necessary conditions was established only recently. In [Reference Lizana and Ranter17], it was proved for surface endomorphisms that a weak form of hyperbolicity is needed for robust transitivity, so-called partial hyperbolicity. Furthermore, it was also proved that only the Torus and the Klein bottle support a robustly transitive endomorphism exhibiting critical points; and that the action of such a map on the first homology group has at least an eigenvalue with modulus greater than one. Later, new classes of examples of robustly transitive endomorphisms were given in [Reference Lizana and Ranter18]. The examples are homotopic to an expanding linear endomorphism on the torus or the Klein bottle; and an example of a robustly transitive endomorphism of zero degree. In higher dimension, the first examples of robustly transitive endomorphisms displaying critical points were constructed only recently in [Reference Morelli22].

1.2 Comments about some previous approaches

Here, we briefly comment on the main ingredients used to show that some (weak) form of hyperbolicity is a necessary condition for the existence of robust transitivity.

1.2.1 Key obstructions for robust transitivity

In a broad sense, an obstruction for robust transitivity is some phenomenon which is incompatible with this feature.

Here, we discuss these phenomena which play an important role in the proof that robust transitivity requires some weak form of hyperbolicity. These phenomena are in some sense related to ‘the candidate for dominated splitting’. Let us define them.

-

• Source. A periodic point p for f, where

$n_p \geq 1$

denotes its period, such that

$n_p \geq 1$

denotes its period, such that

$Df^{n_p}_p$

is a matrix having all the eigenvalues with modulus greater than one.

$Df^{n_p}_p$

is a matrix having all the eigenvalues with modulus greater than one. -

• Sink. A periodic point p for f, where

$n_p \geq 1$

denotes its period, such that

$n_p \geq 1$

denotes its period, such that

$Df^{n_p}_p$

is a matrix having all the eigenvalues with modulus less than one.

$Df^{n_p}_p$

is a matrix having all the eigenvalues with modulus less than one.

The set of all critical points of an endomorphism f will be denoted by

![]() $\mathrm {Cr}(f)$

and its interior in M denoted by

$\mathrm {Cr}(f)$

and its interior in M denoted by

![]() $\mathrm {int}(\mathrm {Cr}(f))$

.

$\mathrm {int}(\mathrm {Cr}(f))$

.

-

• Full-dimensional kernel. There exist a point

$x \in \mathrm {Cr}(f)$

and an integer

$x \in \mathrm {Cr}(f)$

and an integer

$n\geq 1$

such that

$n\geq 1$

such that

$\dim \ker (Df^n_x)=d$

.

$\dim \ker (Df^n_x)=d$

.

1.2.2 Key obstructions versus dominated splitting for diffeomorphisms

Here, we discuss the role of sources and sinks as obstructions to obtain that a robustly transitive diffeomorphism admits a dominated splitting. First, it is easy to see that transitive diffeomorphisms do not admit neither sources nor sinks, otherwise there is a small neighborhood such that its image by some (backward or forward) iterate goes into itself, which is incompatible with transitivity.

Let

![]() $\mathcal {U}_f$

be a neighborhood of f in

$\mathcal {U}_f$

be a neighborhood of f in

![]() $\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

, where all endomorphisms in

$\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

, where all endomorphisms in

![]() $\mathcal {U}_f$

are transitive diffeomorphisms. Let us start commenting on the approaches for surface diffeomorphisms in [Reference Mañé20] and on the higher-dimensional manifold in [Reference Bonatti, Díaz and Pujals8, Reference Díaz, Pujals and Ures11].

$\mathcal {U}_f$

are transitive diffeomorphisms. Let us start commenting on the approaches for surface diffeomorphisms in [Reference Mañé20] and on the higher-dimensional manifold in [Reference Bonatti, Díaz and Pujals8, Reference Díaz, Pujals and Ures11].

-

• In [Reference Mañé20], the fact that sources and sinks are obstructions for transitivity is used to prove that the set of all the periodic points of any surface diffeomorphism in

$\mathcal {U}_f$

is hyperbolic, and so, it has a ‘natural’ splitting given by the stable and unstable directions. Later, it is proved that the lack of domination property allows to create, up to a perturbation, sinks or sources contradicting the robust transitivity. Finally, the classical result is used, the so-called closing lemma, to extend the dominated splitting to the whole surface. Consequently, every robustly transitive surface diffeomorphism admits a dominated splitting (weak hyperbolicity). More precisely, the following dichotomy is proved.In particular, every robustly transitive surface diffeomorphism is an Anosov diffeomorphism.

$\mathcal {U}_f$

is hyperbolic, and so, it has a ‘natural’ splitting given by the stable and unstable directions. Later, it is proved that the lack of domination property allows to create, up to a perturbation, sinks or sources contradicting the robust transitivity. Finally, the classical result is used, the so-called closing lemma, to extend the dominated splitting to the whole surface. Consequently, every robustly transitive surface diffeomorphism admits a dominated splitting (weak hyperbolicity). More precisely, the following dichotomy is proved.In particular, every robustly transitive surface diffeomorphism is an Anosov diffeomorphism.Theorem [Reference Mañé20]

Let M be a closed surface. Then there is a residual subset

${\mathcal {R} \subseteq \mathrm {Diff}^1(M)}$

(that is, the set of all the diffeomorphisms

${\mathcal {R} \subseteq \mathrm {Diff}^1(M)}$

(that is, the set of all the diffeomorphisms

$\mathrm {Diff}^1(M)$

),

$\mathrm {Diff}^1(M)$

),

$\mathcal {R}=\mathcal {R}_1\sqcup \mathcal {R}_2,$

such that every

$\mathcal {R}=\mathcal {R}_1\sqcup \mathcal {R}_2,$

such that every

$f \in \mathcal {R}_1$

is an Axiom A and every

$f \in \mathcal {R}_1$

is an Axiom A and every

$f \in \mathcal {R}_2$

has infinitely many sources and sinks.

$f \in \mathcal {R}_2$

has infinitely many sources and sinks.

Note that in higher-dimensional manifolds, even if each periodic point is hyperbolic, they could have different indexes (that is, unstable directions of different dimensions) which hamper the choice of a ‘natural’ splitting over the set of all the periodic points. Thus, the approach followed in [Reference Bonatti, Díaz and Pujals8, Reference Díaz, Pujals and Ures11] was slightly different.

-

• In this context, they consider a hyperbolic saddle point p of the diffeomorphism f and its homoclinic class, denoted by

$H(p,f)$

. Then, one defines ‘naturally’ a splitting using the stable and unstable directions over

$H(p,f)$

. Then, one defines ‘naturally’ a splitting using the stable and unstable directions over

$H(p,f)$

and proves that if such splitting is not dominated, one can create a source or a sink for some perturbation of f. Since any diffeomorphism in

$H(p,f)$

and proves that if such splitting is not dominated, one can create a source or a sink for some perturbation of f. Since any diffeomorphism in

$\mathcal {U}_f$

admits neither sources nor sinks, one has that

$\mathcal {U}_f$

admits neither sources nor sinks, one has that

$H(p,f)$

admits a dominated splitting. Finally, using classical results such as the closing lemma and connecting lemma, they extend the splitting to the whole manifold, proving that robust transitivity for diffeomorphisms requires dominated splitting (weak hyperbolicity).In fact, the result above follows as a consequence of the following.

$H(p,f)$

admits a dominated splitting. Finally, using classical results such as the closing lemma and connecting lemma, they extend the splitting to the whole manifold, proving that robust transitivity for diffeomorphisms requires dominated splitting (weak hyperbolicity).In fact, the result above follows as a consequence of the following.Theorem [Reference Bonatti, Díaz and Pujals8]

Let p be a hyperbolic saddle of a diffeomorphism f defined on M. Then:

-

– either the homoclinic class

$H(p,f)$

of p admits a dominated splitting; or

$H(p,f)$

of p admits a dominated splitting; or -

– given any neighborhood U of

$H(p,f)$

and any integer

$H(p,f)$

and any integer

$\ell \geq 1$

, there exists g arbitrarily

$\ell \geq 1$

, there exists g arbitrarily

$C^1$

-close to f having

$C^1$

-close to f having

$\ell $

sources or sinks arbitrarily close to p, whose orbits are contained in U.

$\ell $

sources or sinks arbitrarily close to p, whose orbits are contained in U.

Even more, it was proved that every robustly transitive diffeomorphism is volume hyperbolic, which is a consequence of the following result.

Theorem [Reference Bonatti, Díaz and Pujals8, Reference Díaz, Pujals and Ures11]

Let

$\Lambda _f(U)$

be a robustly transitive set and

$\Lambda _f(U)$

be a robustly transitive set and

$E_1\oplus \cdots \oplus E_k$

,

$E_1\oplus \cdots \oplus E_k$

,

$E_1\prec E_2 \prec \cdots \prec E_k$

, be its finest dominated splitting. (A compact set

$E_1\prec E_2 \prec \cdots \prec E_k$

, be its finest dominated splitting. (A compact set

$\Lambda $

is a robustly transitive set for f if it is the maximal f-invariant set in some neighborhood U and if, for every

$\Lambda $

is a robustly transitive set for f if it is the maximal f-invariant set in some neighborhood U and if, for every

$g C^1$

-close to f, the maximal g-invariant set

$g C^1$

-close to f, the maximal g-invariant set

$\Lambda _g(U)=\bigcap _{n \in \mathbb {Z}}g^n(U)$

is also compact and

$\Lambda _g(U)=\bigcap _{n \in \mathbb {Z}}g^n(U)$

is also compact and

$g:\Lambda _g \to \Lambda _g$

is transitive.) Then,

$g:\Lambda _g \to \Lambda _g$

is transitive.) Then,

$\Lambda _f(U)$

is a volume hyperbolic set, that is, there exists an integer

$\Lambda _f(U)$

is a volume hyperbolic set, that is, there exists an integer

$\ell \geq 1$

such that

$\ell \geq 1$

such that

$Df^{\ell }$

uniformly contracts the volume in

$Df^{\ell }$

uniformly contracts the volume in

$E_1$

and uniformly expands the volume in

$E_1$

and uniformly expands the volume in

$E_k$

.

$E_k$

. -

1.2.3 Key obstructions versus dominated splitting for non-invertible endomorphisms

For the case of non-invertible endomorphisms, the situation changes dramatically. On the one hand, the existence of a source no longer is an obstruction, we can consider, for example, an expanding map. On the other hand, as it was said before, there are examples of local diffeomorphisms on surfaces without dominated splitting. Moreover, when endomorphisms having critical points are considered, the full-kernel obstruction (which was first introduced in [Reference Lizana and Ranter17]) plays an essential role.

Key Obstruction Lemma. There are no robustly transitive endomorphisms exhibiting a full-dimensional kernel.

To prove this, we use the following classical tool in

![]() $C^1$

-perturbative arguments introduced by Franks in [Reference Franks12] for diffeomorphisms that can be easily adapted for endomorphisms as follows.

$C^1$

-perturbative arguments introduced by Franks in [Reference Franks12] for diffeomorphisms that can be easily adapted for endomorphisms as follows.

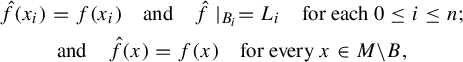

Franks’ Lemma. Given

![]() $\mathcal {U}$

open set in

$\mathcal {U}$

open set in

![]() $\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

and

$\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

and

![]() $f \in \mathcal {U}$

, there exist

$f \in \mathcal {U}$

, there exist

![]() $\varepsilon>0$

such that for every finite collection of distinct points

$\varepsilon>0$

such that for every finite collection of distinct points

![]() $\Sigma =\{x_0,\ldots ,x_n\}$

in M, and linear maps

$\Sigma =\{x_0,\ldots ,x_n\}$

in M, and linear maps

there exist an endomorphism

![]() $\hat {f} \in \mathcal {U}$

, a neighborhood B of

$\hat {f} \in \mathcal {U}$

, a neighborhood B of

![]() $\Sigma $

, and a family of balls

$\Sigma $

, and a family of balls

![]() $\{B_i\}_{i=0}^n$

contained in B, where

$\{B_i\}_{i=0}^n$

contained in B, where

![]() $B_i$

is centered at

$B_i$

is centered at

![]() $x_i$

, verifying

$x_i$

, verifying

$$ \begin{align*} &\hat{f}(x_i)=f(x_i) \quad \text{and}\quad \hat{f}\mid_{B_i}=L_i \quad \text{for each } 0\leq i \leq n; \\& \qquad\!\quad \text{and}\quad \hat{f}(x)=f(x) \quad \text{for every } x \in M\backslash B, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} &\hat{f}(x_i)=f(x_i) \quad \text{and}\quad \hat{f}\mid_{B_i}=L_i \quad \text{for each } 0\leq i \leq n; \\& \qquad\!\quad \text{and}\quad \hat{f}(x)=f(x) \quad \text{for every } x \in M\backslash B, \end{align*} $$

where, by abuse of notation,

![]() $\hat {f}\mid _{B_i}=L_i$

means the action of

$\hat {f}\mid _{B_i}=L_i$

means the action of

![]() $\hat {f}$

in each

$\hat {f}$

in each

![]() $B_i$

is equal to the linear map

$B_i$

is equal to the linear map

![]() $L_i$

.

$L_i$

.

Thus, we can conclude that the Key Obstruction Lemma follows from Franks’ Lemma applied to

![]() $\Sigma =\{x,f(x),\ldots ,f^{m-1}(x)\}$

and

$\Sigma =\{x,f(x),\ldots ,f^{m-1}(x)\}$

and

![]() $L_i=Df_{f^i(x)}$

for each

$L_i=Df_{f^i(x)}$

for each

![]() $i=0,1,\ldots ,m-1$

, where

$i=0,1,\ldots ,m-1$

, where

![]() $\ker (Df^m_x)$

is d-dimensional. Hence, there is an endomorphism

$\ker (Df^m_x)$

is d-dimensional. Hence, there is an endomorphism

![]() $\hat {f}$

arbitrarily close to f so that

$\hat {f}$

arbitrarily close to f so that

![]() $\hat {f}$

is equal to

$\hat {f}$

is equal to

![]() $L_i=Df_{f^i(x)}$

around

$L_i=Df_{f^i(x)}$

around

![]() $f^i(x)$

for each

$f^i(x)$

for each

![]() $i=0,1,\ldots ,m-1$

. In particular,

$i=0,1,\ldots ,m-1$

. In particular,

![]() $\hat {f}^m$

is equal to

$\hat {f}^m$

is equal to

![]() $Df^m_x$

around x and hence the image of such neighborhood of x by

$Df^m_x$

around x and hence the image of such neighborhood of x by

![]() $\hat {f}^m$

is exactly one point which contradicts transitivity. Therefore, f cannot be a robustly transitive endomorphism.

$\hat {f}^m$

is exactly one point which contradicts transitivity. Therefore, f cannot be a robustly transitive endomorphism.

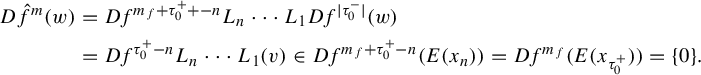

1.2.4 Two-dimensional endormorphisms with critical points

Let us quickly comment about the approach in [Reference Lizana and Ranter17]. For a robustly transitive surface endomorphism f displaying critical points having non-empty interior, one can define the set

![]() $\Lambda $

consisting of all the orbits

$\Lambda $

consisting of all the orbits

![]() $(x_i)_i$

which get into the interior of the critical set infinitely many times for the past and the future. That is,

$(x_i)_i$

which get into the interior of the critical set infinitely many times for the past and the future. That is,

![]() $(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

if and only if

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

if and only if

![]() $x_i \in \mathrm {int}(\mathrm {Cr}(f))$

for infinitely many

$x_i \in \mathrm {int}(\mathrm {Cr}(f))$

for infinitely many

![]() $i<0$

and infinitely many

$i<0$

and infinitely many

![]() $i>0$

. To simplify the notation, let us also denote by f the map on the space of all the orbits defined by

$i>0$

. To simplify the notation, let us also denote by f the map on the space of all the orbits defined by

![]() $(x_i)_i \mapsto (f(x_i))_i=(x_{i+1})_i$

. Then, one has that

$(x_i)_i \mapsto (f(x_i))_i=(x_{i+1})_i$

. Then, one has that

![]() $\Lambda $

is f-invariant and, moreover, one can define for every

$\Lambda $

is f-invariant and, moreover, one can define for every

![]() $(x_i)_i$

in

$(x_i)_i$

in

![]() $\Lambda $

an invariant splitting of the tangent bundle over

$\Lambda $

an invariant splitting of the tangent bundle over

![]() $\Lambda $

as follows:

$\Lambda $

as follows:

where

![]() $\tau _i^{+}\geq 0$

is the time that

$\tau _i^{+}\geq 0$

is the time that

![]() $x_i$

takes to enter in the critical set for the first time, and

$x_i$

takes to enter in the critical set for the first time, and

![]() $\tau _i^{-} < 0$

is the time that

$\tau _i^{-} < 0$

is the time that

![]() $x_{i}$

takes to go back to the critical set along the orbit

$x_{i}$

takes to go back to the critical set along the orbit

![]() $(x_i)_i$

for the first time. In particular, we have

$(x_i)_i$

for the first time. In particular, we have

![]() $x_{i+\tau _i^{+}}$

and

$x_{i+\tau _i^{+}}$

and

![]() $x_{i+\tau _i^{-}}$

in

$x_{i+\tau _i^{-}}$

in

![]() $\mathrm {Cr}(f)$

.

$\mathrm {Cr}(f)$

.

The splitting

![]() $E\oplus F$

is well defined over

$E\oplus F$

is well defined over

![]() $\Lambda $

because the full-dimensional kernel obstruction guarantees that

$\Lambda $

because the full-dimensional kernel obstruction guarantees that

![]() $\ker (Df^n_{x_i})$

is at most one-dimensional for any

$\ker (Df^n_{x_i})$

is at most one-dimensional for any

![]() $n\geq 0$

. In particular, E is one-dimensional and

$n\geq 0$

. In particular, E is one-dimensional and

![]() $Df$

-invariant. Furthermore, the definition of

$Df$

-invariant. Furthermore, the definition of

![]() $\tau _i^{-}$

is used together with the fact that

$\tau _i^{-}$

is used together with the fact that

![]() $\dim \ker (Df^n_{x_i}) \leq 1$

, for all

$\dim \ker (Df^n_{x_i}) \leq 1$

, for all

![]() $n\geq 1$

, to show that F is

$n\geq 1$

, to show that F is

![]() $Df$

-invariant. Then, to get that

$Df$

-invariant. Then, to get that

![]() $E\oplus F$

is a dominated splitting, it is proved in [Reference Lizana and Ranter17] that the absence of domination property allows to create a point having full-dimensional kernel for some

$E\oplus F$

is a dominated splitting, it is proved in [Reference Lizana and Ranter17] that the absence of domination property allows to create a point having full-dimensional kernel for some

![]() $C^1$

-perturbation of f which is incompatible with robust transitivity. Thus,

$C^1$

-perturbation of f which is incompatible with robust transitivity. Thus,

![]() $E\oplus F$

is a dominated splitting and it can be extended to the closure of

$E\oplus F$

is a dominated splitting and it can be extended to the closure of

![]() $\Lambda $

which is the whole space. Finally, we use that every robustly transitive endomorphism displaying critical points is approximated by such kinds of endomorphisms having dominated splitting, which allows us to push the domination splitting to the limit to conclude Theorem A for surface endomorphisms.

$\Lambda $

which is the whole space. Finally, we use that every robustly transitive endomorphism displaying critical points is approximated by such kinds of endomorphisms having dominated splitting, which allows us to push the domination splitting to the limit to conclude Theorem A for surface endomorphisms.

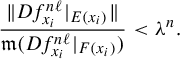

In higher dimension, the kernel of

![]() $Df^n$

may have distinct dimensions depending on n, even if the kernel of

$Df^n$

may have distinct dimensions depending on n, even if the kernel of

![]() $Df$

has constant dimension. Moreover, the subbundles E and F on

$Df$

has constant dimension. Moreover, the subbundles E and F on

![]() $\Lambda $

may not have constant dimension along the orbit on

$\Lambda $

may not have constant dimension along the orbit on

![]() $\Lambda $

.

$\Lambda $

.

In the sequel, we explain our strategy to figure out that obstacle and then prove Theorem A.

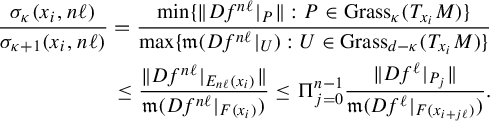

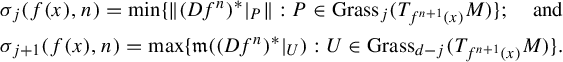

1.3 Sketch of the proof of Theorem A

Let

![]() $f_0$

be a robustly transitive endomorphism displaying critical points and

$f_0$

be a robustly transitive endomorphism displaying critical points and

![]() $\mathcal {U}_0$

a neighborhood of

$\mathcal {U}_0$

a neighborhood of

![]() $f_0$

in

$f_0$

in

![]() $\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

such that every endomorphism in it is (robustly) transitive. Up to shrink

$\mathrm {End}^1(M)$

such that every endomorphism in it is (robustly) transitive. Up to shrink

![]() $\mathcal {U}_0$

, we can find

$\mathcal {U}_0$

, we can find

![]() $1\leq \kappa <d$

as the smallest integer satisfying

$1\leq \kappa <d$

as the smallest integer satisfying

where

![]() $\dim \ker (Df)=\max _{x \in M}\dim \ker (Df_x)$

. Otherwise, we could find

$\dim \ker (Df)=\max _{x \in M}\dim \ker (Df_x)$

. Otherwise, we could find

![]() $f \in \mathcal {U}_0$

and

$f \in \mathcal {U}_0$

and

![]() ${m\geq 1}$

such that

${m\geq 1}$

such that

![]() $\dim \ker (Df^m)=d$

, which by Key Obstruction Lemma is absurd since f is also a robustly transitive endomorphism.

$\dim \ker (Df^m)=d$

, which by Key Obstruction Lemma is absurd since f is also a robustly transitive endomorphism.

Since

![]() $\kappa $

is chosen as the smallest integer satisfying (1.2), it follows that

$\kappa $

is chosen as the smallest integer satisfying (1.2), it follows that

![]() $f_0$

can be approximated by

$f_0$

can be approximated by

![]() $f \in \mathcal {U}_0$

satisfying the equality for some

$f \in \mathcal {U}_0$

satisfying the equality for some

![]() $m\geq 1$

. Let us define

$m\geq 1$

. Let us define

![]() $m_f$

as the smallest positive integer m such that:

$m_f$

as the smallest positive integer m such that:

-

•

$\{x \in M:\dim \ker (Df^m_x)=\kappa \}$

has non-empty interior; or

$\{x \in M:\dim \ker (Df^m_x)=\kappa \}$

has non-empty interior; or -

• if such a subset above has an empty interior, then we take

$m_f$

as the smallest one such that

$m_f$

as the smallest one such that

$\dim \ker (Df^m_x)=\kappa $

for some

$\dim \ker (Df^m_x)=\kappa $

for some

$x \in M.$

$x \in M.$

To avoid any confusion, we point out that the second item must be considered if and only if the interior of

![]() $\{x \in M:\dim \ker (Df^m_x)=\kappa \}$

is empty.

$\{x \in M:\dim \ker (Df^m_x)=\kappa \}$

is empty.

From now on, let us define

![]() $\mathrm {Cr}_{\kappa }(f)$

as the set

$\mathrm {Cr}_{\kappa }(f)$

as the set

![]() $\{x \in M:\dim \ker (Df^{m_f}_x)=\kappa \}$

. This set plays an important role in our approach. Furthermore, we denote the set of all endomorphisms f in

$\{x \in M:\dim \ker (Df^{m_f}_x)=\kappa \}$

. This set plays an important role in our approach. Furthermore, we denote the set of all endomorphisms f in

![]() $\mathcal {U}_0$

where

$\mathcal {U}_0$

where

![]() $\mathrm {Cr}_{\kappa }(f)$

has non-empty interior by

$\mathrm {Cr}_{\kappa }(f)$

has non-empty interior by

![]() $\mathcal {F}_0$

.

$\mathcal {F}_0$

.

It should be noted that

![]() $\mathcal {F}_0$

is non-empty and accumulates at

$\mathcal {F}_0$

is non-empty and accumulates at

![]() $f_0$

. Indeed, given

$f_0$

. Indeed, given

![]() ${x \in \mathrm {Cr}_{\kappa }(f)}$

for some f close to

${x \in \mathrm {Cr}_{\kappa }(f)}$

for some f close to

![]() $f_0$

, we can apply Franks’ Lemma to

$f_0$

, we can apply Franks’ Lemma to

![]() $\Sigma =\{x,f(x),\ldots , f^{m_f-1}(x)\}$

and

$\Sigma =\{x,f(x),\ldots , f^{m_f-1}(x)\}$

and

![]() $L_i=Df_{f^i(x)}$

, for each

$L_i=Df_{f^i(x)}$

, for each

![]() $i=0,1,\ldots ,m_f-1$

, to get an endomorphism

$i=0,1,\ldots ,m_f-1$

, to get an endomorphism

![]() $\hat {f} C^1$

-close to f and, therefore, close to

$\hat {f} C^1$

-close to f and, therefore, close to

![]() $f_0$

, such that

$f_0$

, such that

![]() $ \ker (D\hat {f}^{m_f}_y)$

is

$ \ker (D\hat {f}^{m_f}_y)$

is

![]() $\kappa $

-dimensional for every y near x. Then, we conclude that

$\kappa $

-dimensional for every y near x. Then, we conclude that

![]() $\mathrm {Cr}_{\kappa }(\hat {f})$

has non-empty interior and, moreover,

$\mathrm {Cr}_{\kappa }(\hat {f})$

has non-empty interior and, moreover,

![]() $m_{\hat {f}}\leq m_f$

.

$m_{\hat {f}}\leq m_f$

.

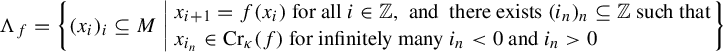

We now define the set

![]() $\Lambda $

and the splitting

$\Lambda $

and the splitting

![]() $E\oplus F$

in our context of higher dimension. For

$E\oplus F$

in our context of higher dimension. For

![]() $f \in \mathcal {F}_0$

, we define

$f \in \mathcal {F}_0$

, we define

$$ \begin{align} \Lambda_f=\left\{(x_i)_i \subseteq M\left|\!\begin{array}{l}x_{i+1}=f(x_i) \text{ for all } i \in \mathbb{Z}, \text{ and } \text{ there exists } (i_n)_{n} \subseteq \mathbb{Z} \text{ such that}\!\!\! \\ x_{i_n} \in \mathrm{Cr}_{\kappa}(f) \text{ for infinitely many } i_n<0 \text{ and } i_n>0\end{array}\right.\right\} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \Lambda_f=\left\{(x_i)_i \subseteq M\left|\!\begin{array}{l}x_{i+1}=f(x_i) \text{ for all } i \in \mathbb{Z}, \text{ and } \text{ there exists } (i_n)_{n} \subseteq \mathbb{Z} \text{ such that}\!\!\! \\ x_{i_n} \in \mathrm{Cr}_{\kappa}(f) \text{ for infinitely many } i_n<0 \text{ and } i_n>0\end{array}\right.\right\} \end{align} $$

and

where

Note that

![]() $\tau ^{-}_i$

and

$\tau ^{-}_i$

and

![]() $\tau ^{+}_i$

are slightly different from those in [Reference Lizana and Ranter17] (recall definition in (1.1)). However, it should be noted that

$\tau ^{+}_i$

are slightly different from those in [Reference Lizana and Ranter17] (recall definition in (1.1)). However, it should be noted that

![]() $m_f$

is the time that

$m_f$

is the time that

![]() $\ker (Df^n)$

have maximal dimension in

$\ker (Df^n)$

have maximal dimension in

![]() $\mathcal {U}_0$

and

$\mathcal {U}_0$

and

![]() $\mathrm {Cr}_{\kappa }(f)$

is the set such that the kernel of

$\mathrm {Cr}_{\kappa }(f)$

is the set such that the kernel of

![]() $Df^{m_f}$

has maximal dimension. In particular, if f is a surface endomorphism, we have that

$Df^{m_f}$

has maximal dimension. In particular, if f is a surface endomorphism, we have that

![]() $m_f=1, \kappa =1$

,

$m_f=1, \kappa =1$

,

![]() $\mathrm {Cr}_1(f)$

is the critical set of f, and

$\mathrm {Cr}_1(f)$

is the critical set of f, and

![]() $\tau ^{\pm }_i$

are the same as in [Reference Lizana and Ranter17].

$\tau ^{\pm }_i$

are the same as in [Reference Lizana and Ranter17].

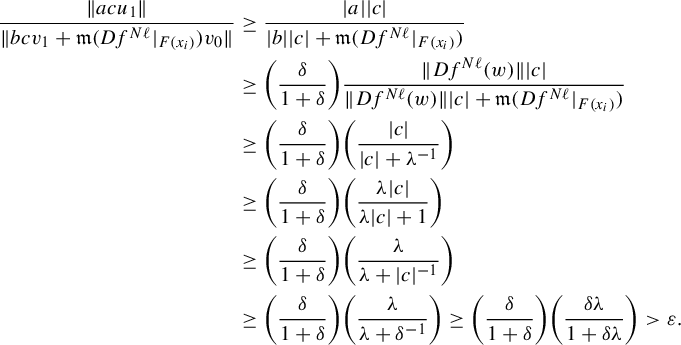

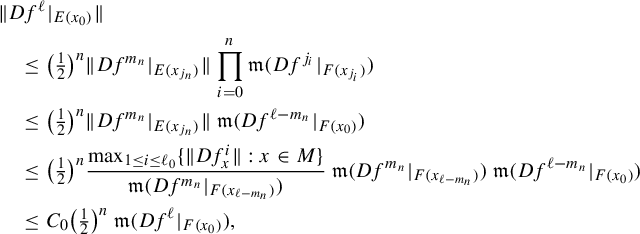

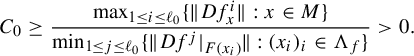

We remark that (up to taking a subset)

![]() $\mathcal {F}_0$

is the natural candidate to prove Theorem B. Then, it remains to show that there is an integer

$\mathcal {F}_0$

is the natural candidate to prove Theorem B. Then, it remains to show that there is an integer

![]() $\ell>0$

and a number

$\ell>0$

and a number

![]() $\alpha>0$

such that

$\alpha>0$

such that

![]() $E\oplus F$

is an

$E\oplus F$

is an

![]() $(\alpha ,\ell )$

-dominated splitting. To prove that, we will see in Lemma 3.1 that

$(\alpha ,\ell )$

-dominated splitting. To prove that, we will see in Lemma 3.1 that

![]() $\Lambda _f$

, given by (*), is dense in the inverse limit space (see §2) and, in Proposition 2.10,

$\Lambda _f$

, given by (*), is dense in the inverse limit space (see §2) and, in Proposition 2.10,

![]() $E\oplus F$

can be extended to the closure of

$E\oplus F$

can be extended to the closure of

![]() $\Lambda _f$

once provided that

$\Lambda _f$

once provided that

![]() $E\oplus F$

is an

$E\oplus F$

is an

![]() $(\alpha ,\ell )$

-dominated splitting.

$(\alpha ,\ell )$

-dominated splitting.

To prove such uniform behavior, we state a technical dichotomy as follows. However, before doing it, we would like to emphasize that to define E and F in (**), only the fact that

![]() $\Lambda _f\neq \emptyset $

is used and

$\Lambda _f\neq \emptyset $

is used and

![]() $\dim \ker (Df^m)\leq \kappa $

for all

$\dim \ker (Df^m)\leq \kappa $

for all

![]() $m\geq 1$

.

$m\geq 1$

.

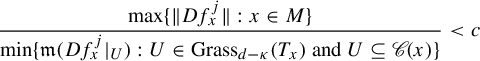

Theorem C. Let

![]() $f_0$

be an endomorphism displaying critical points. Assume that there is an integer

$f_0$

be an endomorphism displaying critical points. Assume that there is an integer

![]() $1\leq \kappa <d$

and a set

$1\leq \kappa <d$

and a set

![]() $\mathcal {F}$

consisting of endomorphisms converging to

$\mathcal {F}$

consisting of endomorphisms converging to

![]() $f_0$

such that every

$f_0$

such that every

![]() $f \in \mathcal {F}$

satisfies that

$f \in \mathcal {F}$

satisfies that

![]() $\Lambda _f\neq \emptyset $

and

$\Lambda _f\neq \emptyset $

and

![]() $\dim \ker (Df^m)\leq \kappa \text { for all } m \in \mathbb {Z}$

. Then, only one of the following statements hold:

$\dim \ker (Df^m)\leq \kappa \text { for all } m \in \mathbb {Z}$

. Then, only one of the following statements hold:

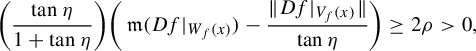

-

• either there exist

$\ell>0$

and

$\ell>0$

and

$\alpha>0$

such that for each

$\alpha>0$

such that for each

$f \in \mathcal {F}$

, the splitting

$f \in \mathcal {F}$

, the splitting

$E\oplus F$

is an (

$E\oplus F$

is an (

$\alpha ,\ell $

)-dominated splitting over

$\alpha ,\ell $

)-dominated splitting over

$\Lambda _f$

; or

$\Lambda _f$

; or -

•

$f_0$

is accumulated by endomorphisms g, where

$f_0$

is accumulated by endomorphisms g, where

$\ker (Dg^m)$

has dimension greater than

$\ker (Dg^m)$

has dimension greater than

$\kappa $

for some

$\kappa $

for some

$m \geq 1$

.

$m \geq 1$

.

We have already shown that

![]() $\mathcal {F}_0$

satisfies the hypothesis of Theorem C and

$\mathcal {F}_0$

satisfies the hypothesis of Theorem C and

![]() $f_0$

cannot be approximated by endomorphisms whose kernel has dimension greater than

$f_0$

cannot be approximated by endomorphisms whose kernel has dimension greater than

![]() $\kappa $

. Then, Theorem B follows from Theorem C since Lemma 3.1 implies the density of

$\kappa $

. Then, Theorem B follows from Theorem C since Lemma 3.1 implies the density of

![]() $\Lambda _f$

, and in Proposition 2.10, we prove that the dominated splitting can be extended to the closure of

$\Lambda _f$

, and in Proposition 2.10, we prove that the dominated splitting can be extended to the closure of

![]() $\Lambda _f$

which is the space of all the orbits.

$\Lambda _f$

which is the space of all the orbits.

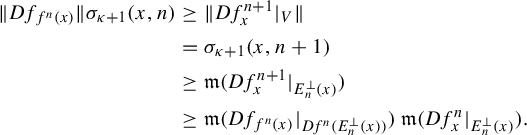

1.3.1 Novelties and new techniques

We want to emphasize the new approaches brought by the present paper that differ with those developed for diffeomorphisms and surface endomorphisms having critical points.

-

• The kernel of

$Df$

is used at the critical set (that could be multidimensional and have different dimension at distinct points) to build a candidate for a dominated splitting on a dense set. On the one hand, this is substantially different from how the splitting is built for the case of diffeomorphisms where the splitting over the periodic points is used. On the other hand, the strategy goes beyond the approach for surface endomorphisms where the kernel of

$Df$

is used at the critical set (that could be multidimensional and have different dimension at distinct points) to build a candidate for a dominated splitting on a dense set. On the one hand, this is substantially different from how the splitting is built for the case of diffeomorphisms where the splitting over the periodic points is used. On the other hand, the strategy goes beyond the approach for surface endomorphisms where the kernel of

$Df^n$

has dimension one for any point in the critical set and any iterated n.

$Df^n$

has dimension one for any point in the critical set and any iterated n. -

• A dominated splitting defined on an invariant non-compact set could not be extended to the closure (see Example 2.3). Therefore, a fine control on the angle between multidimensional subbundles has to be brought into consideration, an issue that is not present in previous approaches.

1.4 How the paper is organized

In §2, we discuss the notion of dominated splitting and some related properties, the equivalence of dominated splitting via cone criterion. In §3, we use Theorem B to prove Theorem A. Finally, §4 is devoted to the proof of Theorem C and to recall that Theorem B follows from Theorem C.

2 Weak form of hyperbolicity for endomorphisms

In this section, the notion of dominated splitting will be formalized in terms of invariant splitting for endomorphisms displaying critical points. Further, we will present some fundamental properties that will be useful throughout this paper.

Due to the fact that for an endomorphism, a point may exhibit more than one preimage, it is natural to consider the inverse limit space of M with respect to f,

It is a compact metric space and the natural projection

![]() $(x_i)_i \mapsto x_0$

is continuous. Moreover, an endomorphism

$(x_i)_i \mapsto x_0$

is continuous. Moreover, an endomorphism

![]() $f \in \mathrm {End}^1(M)$

induces a homeomorphism on

$f \in \mathrm {End}^1(M)$

induces a homeomorphism on

![]() $M_f$

defined by

$M_f$

defined by

![]() $(x_i)_i \mapsto (f(x_i))_i=(x_{i+1})_i$

, and whenever there is no confusion, it will also be denoted by f. The points in

$(x_i)_i \mapsto (f(x_i))_i=(x_{i+1})_i$

, and whenever there is no confusion, it will also be denoted by f. The points in

![]() $M_f$

are called the orbits of f. A subset

$M_f$

are called the orbits of f. A subset

![]() $\Lambda $

of

$\Lambda $

of

![]() $M_f$

is said to be f-invariant or simply, invariant if

$M_f$

is said to be f-invariant or simply, invariant if

![]() $f^{-1}(\Lambda )=\Lambda $

.

$f^{-1}(\Lambda )=\Lambda $

.

The concept of dominated splitting is established in the context of endomorphisms without critical points (that is, local diffeomorphisms and diffeomorphisms) and its definition is the following.

We say that an f-invariant set

![]() $\Lambda \subseteq M_f$

admits a dominated splitting of index

$\Lambda \subseteq M_f$

admits a dominated splitting of index

![]() $\kappa $

for f if for all

$\kappa $

for f if for all

![]() $(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

, there exist two families

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

, there exist two families

![]() $(E(x_i))_i$

and

$(E(x_i))_i$

and

![]() $(F(x_i))_i$

of

$(F(x_i))_i$

of

![]() $\kappa $

and

$\kappa $

and

![]() $(d-\kappa )$

-dimensional subspaces satisfying the following properties.

$(d-\kappa )$

-dimensional subspaces satisfying the following properties.

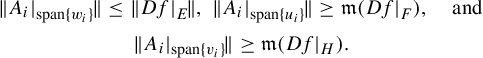

Invariant splitting. For each

![]() $i \in \mathbb {Z}$

, one has that

$i \in \mathbb {Z}$

, one has that

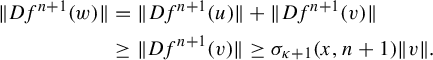

Domination property. There exists

![]() $\ell \geq 1$

such that for each

$\ell \geq 1$

such that for each

![]() $i \in \mathbb {Z}$

and unit vectors

$i \in \mathbb {Z}$

and unit vectors

![]() $u \in E(x_i)$

and

$u \in E(x_i)$

and

![]() $v \in F(x_i)$

, one has that

$v \in F(x_i)$

, one has that

When f is a diffeomorphism, M is used instead of

![]() $M_f$

in the definition above. Recall that the domination property is denoted by

$M_f$

in the definition above. Recall that the domination property is denoted by

![]() $E \prec F$

or

$E \prec F$

or

![]() $E\prec _{\ell } F$

if we want to emphasize the role of

$E\prec _{\ell } F$

if we want to emphasize the role of

![]() $\ell $

.

$\ell $

.

Remark 2.1. The families E and F are actually subbundles of the vector bundle of

![]() $M_f$

defined by

$M_f$

defined by

![]() $TM_f=\{((x_i)_i,v) : v \in T_{x_0}M\}$

. Moreover, the bundle E depends only on the forward orbit while F depends only on the backward orbit of a point in

$TM_f=\{((x_i)_i,v) : v \in T_{x_0}M\}$

. Moreover, the bundle E depends only on the forward orbit while F depends only on the backward orbit of a point in

![]() $M_f$

. This implies that the bundle E induces a subbundle of

$M_f$

. This implies that the bundle E induces a subbundle of

![]() $TM$

and this will be used in the proof of Corollary 1.1.

$TM$

and this will be used in the proof of Corollary 1.1.

Remark 2.2. Let W be any inner product space and

![]() $\Phi :W \to W$

be a linear map. For a subspace V of W, we denote

$\Phi :W \to W$

be a linear map. For a subspace V of W, we denote

![]() $\Phi $

restricted to V by

$\Phi $

restricted to V by

![]() $\Phi \mid _V$

and respectively define the norm and conorm of

$\Phi \mid _V$

and respectively define the norm and conorm of

![]() $\Phi \mid _V$

by

$\Phi \mid _V$

by

When V is the whole space, we simply say that

![]() $\|\Phi \|$

and

$\|\Phi \|$

and

![]() $\operatorname {{\mathfrak {m}}}(\Phi )$

are the norm and conorm of

$\operatorname {{\mathfrak {m}}}(\Phi )$

are the norm and conorm of

![]() $\Phi $

.

$\Phi $

.

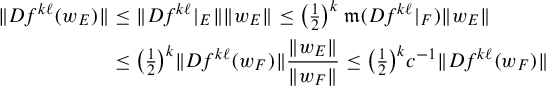

From now on, by Remark 2.2, we rewrite the inequality in the domination property:

Some differences should be pointed out when the derivative is not invertible everywhere. For instance, suppose that

![]() $E \oplus F$

is a splitting over an f-invariant set

$E \oplus F$

is a splitting over an f-invariant set

![]() $\Lambda \subseteq M_f$

verifying all the properties of the definition above. Note that if

$\Lambda \subseteq M_f$

verifying all the properties of the definition above. Note that if

![]() $u_E+u_F \in \ker (Df_{x_i})$

, where

$u_E+u_F \in \ker (Df_{x_i})$

, where

![]() $u_E \in E(x_i)$

and

$u_E \in E(x_i)$

and

![]() $u_F \in F(x_i)$

, then

$u_F \in F(x_i)$

, then

![]() $Df(u_E)$

is parallel to

$Df(u_E)$

is parallel to

![]() $Df(u_F)$

which affects the invariance property. Moreover, if

$Df(u_F)$

which affects the invariance property. Moreover, if

![]() $u_F \in \ker (Df_{x_i})$

, then the domination property implies that

$u_F \in \ker (Df_{x_i})$

, then the domination property implies that

![]() $ E(x_i)$

is contained in

$ E(x_i)$

is contained in

![]() $\ker (Df_{x_i})$

, and so neither

$\ker (Df_{x_i})$

, and so neither

![]() $E(x_i)$

nor

$E(x_i)$

nor

![]() $F(x_i)$

are invariant. Therefore, to extend the notion of dominated splitting, we require the following:

$F(x_i)$

are invariant. Therefore, to extend the notion of dominated splitting, we require the following:

In addition, we also require that the angle between E and F is uniformly away from zero. This will allow to extend the dominated splitting to the closure of

![]() $\Lambda $

, see Proposition 2.10. Otherwise, an orbit

$\Lambda $

, see Proposition 2.10. Otherwise, an orbit

![]() $(x_i)_i$

may exist such that

$(x_i)_i$

may exist such that

![]() $E(x_i)=\ker (Df_{x_i})$

, and the angles of

$E(x_i)=\ker (Df_{x_i})$

, and the angles of

![]() $E(x_i)$

and

$E(x_i)$

and

![]() $F(x_i)$

go to zero as i goes to

$F(x_i)$

go to zero as i goes to

![]() $+\infty $

then, somewhere on the boundary of

$+\infty $

then, somewhere on the boundary of

![]() $\Lambda $

, the extensions of E and F have some intersection. See the following example.

$\Lambda $

, the extensions of E and F have some intersection. See the following example.

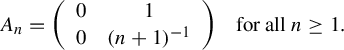

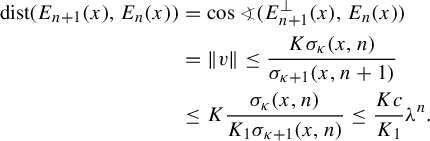

Example 2.3. Let

![]() $(A_n)_n$

be a sequence of square matrices defined by

$(A_n)_n$

be a sequence of square matrices defined by

$$ \begin{align*}A_n=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1\\ 0 & (n+1)^{-1} \end{array}\right)\! \quad \text{for all } n \geq 1.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}A_n=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1\\ 0 & (n+1)^{-1} \end{array}\right)\! \quad \text{for all } n \geq 1.\end{align*} $$

Take

![]() $E:=E_n$

and

$E:=E_n$

and

![]() $F_n$

as the subspaces generated by

$F_n$

as the subspaces generated by

![]() $v=(1,0)$

and

$v=(1,0)$

and

![]() $v_n=(1,1/n)$

, respectively. Then,

$v_n=(1,1/n)$

, respectively. Then,

![]() $E_n \oplus F_n$

is a dominated splitting for

$E_n \oplus F_n$

is a dominated splitting for

![]() $(A_n)_n$

since

$(A_n)_n$

since

![]() $A_n(E_n) \subseteq E_{n+1}$

and

$A_n(E_n) \subseteq E_{n+1}$

and

![]() $A_n(F_n)=F_{n+1}$

. Moreover,

$A_n(F_n)=F_{n+1}$

. Moreover,

for each

![]() $n \geq 1$

. However,

$n \geq 1$

. However,

![]() $E_n$

and

$E_n$

and

![]() $F_n$

converge to the same subspace E.

$F_n$

converge to the same subspace E.

This example shows the existence of a dominated splitting along an orbit which cannot be extended to the closure.

Thus, before proposing the definition of dominated splitting for an endomorphism displaying critical points, we should introduce the notion about the angle between subspaces.

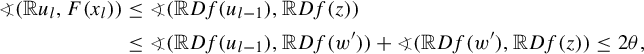

The angle between the non-zero vectors

![]() $v,w \in T_xM$

with respect to the metric

$v,w \in T_xM$

with respect to the metric

![]() $\langle \cdot ,\cdot \rangle $

(where, for simplicity, we ignore the dependence of the inner product on x in M) is defined as the unique number

$\langle \cdot ,\cdot \rangle $

(where, for simplicity, we ignore the dependence of the inner product on x in M) is defined as the unique number ![]() in

in

![]() $[0,\pi ]$

satisfying

$[0,\pi ]$

satisfying ![]() . Then, given V and W, two non-trivial subspaces of

. Then, given V and W, two non-trivial subspaces of

![]() $T_xM$

, we define the angle between them by

$T_xM$

, we define the angle between them by

The angle between two subspace is a number contained in

![]() $[0,\pi /2]$

. We also write

$[0,\pi /2]$

. We also write ![]() to refer to the angle between the space generated by a non-zero vector v and the subspace W.

to refer to the angle between the space generated by a non-zero vector v and the subspace W.

We would like to emphasize that ![]() does not mean that

does not mean that

![]() $V=W$

, it just means that the intersection between V and W is non-trivial; and

$V=W$

, it just means that the intersection between V and W is non-trivial; and ![]() for some

for some

![]() $\alpha>0$

means that V and W are far away from each other. This notion of angle between two subspaces will be useful to extend the definition of dominated splitting in the context of endomorphisms displaying critical points. Furthermore, that angle allows us to define a distance on

$\alpha>0$

means that V and W are far away from each other. This notion of angle between two subspaces will be useful to extend the definition of dominated splitting in the context of endomorphisms displaying critical points. Furthermore, that angle allows us to define a distance on

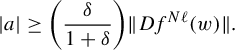

![]() $\mathrm {Grass}_r(T_xM)$

, called the r-dimensional Grassmannian of

$\mathrm {Grass}_r(T_xM)$

, called the r-dimensional Grassmannian of

![]() $T_xM$

, which consists of all the r-dimensional subspaces of

$T_xM$

, which consists of all the r-dimensional subspaces of

![]() $T_xM$

. For all V and W in

$T_xM$

. For all V and W in

![]() $\mathrm {Grass}_r(T_xM)$

, we define the distance between them by

$\mathrm {Grass}_r(T_xM)$

, we define the distance between them by

where

![]() $V^{\perp }$

denotes the orthogonal complement of V. It is well known that the Grassmannian endowed with this distance is a compact metric space. For more details about the distance, see [Reference Bochi, Potrie and Sambarino6, Appendix A.1]

$V^{\perp }$

denotes the orthogonal complement of V. It is well known that the Grassmannian endowed with this distance is a compact metric space. For more details about the distance, see [Reference Bochi, Potrie and Sambarino6, Appendix A.1]

Now, we are able to define a dominated splitting for endomorphisms exhibiting critical points.

Definition 2.1. Let

![]() $f \in \mathrm {End}^1(M)$

be an endomorphism displaying critical points. An invariant subset

$f \in \mathrm {End}^1(M)$

be an endomorphism displaying critical points. An invariant subset

![]() $\Lambda $

of

$\Lambda $

of

![]() $M_f$

admits a dominated splitting of index

$M_f$

admits a dominated splitting of index

![]() $\kappa $

for f if for all

$\kappa $

for f if for all

![]() $(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

, there exist two families

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

, there exist two families

![]() $(E(x_i))_i$

and

$(E(x_i))_i$

and

![]() $(F(x_i))_i$

of

$(F(x_i))_i$

of

![]() $\kappa $

and

$\kappa $

and

![]() $(d-\kappa )$

-dimensional subspaces such that the following properties hold.

$(d-\kappa )$

-dimensional subspaces such that the following properties hold.

Invariant splitting. For each

![]() $i \in \mathbb {Z}$

, one has that

$i \in \mathbb {Z}$

, one has that

$$ \begin{align*} & Df(E(x_i))\subseteq E(f(x_i)), \quad Df(F(x_i))=F(f(x_i)),\\ & \qquad\qquad\!\!\quad \text{and} \quad T_{x_i}M=E(x_i)\oplus F(x_i). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} & Df(E(x_i))\subseteq E(f(x_i)), \quad Df(F(x_i))=F(f(x_i)),\\ & \qquad\qquad\!\!\quad \text{and} \quad T_{x_i}M=E(x_i)\oplus F(x_i). \end{align*} $$

Uniform angle. There exists

![]() $\alpha>0$

such that

$\alpha>0$

such that ![]() for each

for each

![]() $i \in \mathbb {Z}$

.

$i \in \mathbb {Z}$

.

Domination property. There exists

![]() $\ell \geq 1$

such that

$\ell \geq 1$

such that

![]() $E\prec _{\ell } F$

.

$E\prec _{\ell } F$

.

We will say that

![]() $E\oplus F$

is an

$E\oplus F$

is an

![]() $(\alpha ,\ell )$

-dominated splitting if we want to emphasize the role of

$(\alpha ,\ell )$

-dominated splitting if we want to emphasize the role of

![]() $\ell $

and

$\ell $

and

![]() $\alpha $

. When

$\alpha $

. When

![]() $\Lambda =M_f$

, we also say that f has a dominated splitting. For simplicity, we will write

$\Lambda =M_f$

, we also say that f has a dominated splitting. For simplicity, we will write

![]() $E\prec F$

instead of

$E\prec F$

instead of

![]() $E\prec _{\ell } F$

when there is no confusion.

$E\prec _{\ell } F$

when there is no confusion.

Remark 2.4. Observe that if E and F satisfy the items in Definition 2.1, then

![]() $Df\mid _F$

is an isomorphism and

$Df\mid _F$

is an isomorphism and

![]() $\ker (Df_{x_i}^n) \subseteq E(x_i)$

for each

$\ker (Df_{x_i}^n) \subseteq E(x_i)$

for each

![]() $(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

and

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

and

![]() $n\geq 1$

.

$n\geq 1$

.

Remark 2.5. No uniform angle property is required to define dominated splitting for endomorphisms displaying critical points in the introduction. The uniformity of the angle follows from the fact that the manifold is compact and the subbundles are continuous.

More generally, an invariant subset

![]() $\Lambda $

of

$\Lambda $

of

![]() $M_f$

admits a dominated splitting of index

$M_f$

admits a dominated splitting of index

![]() $\kappa $

for f if for all

$\kappa $

for f if for all

![]() $(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

, there exist non-trivial families

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

, there exist non-trivial families

![]() $(E(x_i))_i$

and

$(E(x_i))_i$

and

![]() $(F_j(x_i))_i,\ {1\leq j \leq r}$

, of

$(F_j(x_i))_i,\ {1\leq j \leq r}$

, of

![]() $\kappa $

and

$\kappa $

and

![]() $d_j$

-dimensional subspaces with

$d_j$

-dimensional subspaces with

![]() $d_1+d_2+\cdots +d_r=d-\kappa $

satisfying the following properties.

$d_1+d_2+\cdots +d_r=d-\kappa $

satisfying the following properties.

Invariant splitting. For each

![]() $i \in \mathbb {Z}$

, one has that

$i \in \mathbb {Z}$

, one has that

Uniform angle. There exists

![]() $\alpha>0$

so that

$\alpha>0$

so that ![]() for each

for each

![]() $i \in \mathbb {Z}$

.

$i \in \mathbb {Z}$

.

Domination property.

![]() $E\prec F_1 \prec F_2 \prec \cdots \prec F_r$

.

$E\prec F_1 \prec F_2 \prec \cdots \prec F_r$

.

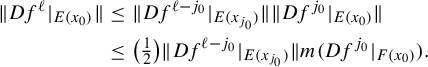

2.1 Dominated splitting properties

Throughout this section, we adapt some of the main properties about dominated splitting which appear in [Reference Crovisier and Potrie10] in the diffeomorphisms context to the context of endomorphisms displaying critical points.

Let f be an endomorphism displaying critical points and

![]() $E\oplus F$

be a dominated splitting over f-invariant subset

$E\oplus F$

be a dominated splitting over f-invariant subset

![]() $\Lambda $

of

$\Lambda $

of

![]() $M_f$

.

$M_f$

.

The uniqueness of the dominated splitting is guaranteed by the following.

Proposition 2.6. If

![]() $G\oplus H$

is a dominated splitting over

$G\oplus H$

is a dominated splitting over

![]() $\Lambda $

for f, which holds

$\Lambda $

for f, which holds

![]() ${\dim E=\dim G}$

, then

${\dim E=\dim G}$

, then

![]() $E(x_i)=G(x_i)$

and

$E(x_i)=G(x_i)$

and

![]() $F(x_i)=H(x_i)$

for all

$F(x_i)=H(x_i)$

for all

![]() $x_i$

in the orbit

$x_i$

in the orbit

![]() $(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

.

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

.

The proof needs some preliminaries.

Lemma 2.7. If

![]() $G\oplus H$

is a dominated splitting over

$G\oplus H$

is a dominated splitting over

![]() $\Lambda $

for f with

$\Lambda $

for f with

![]() $\dim E(x_i)\leq \dim G(x_i)$

for all

$\dim E(x_i)\leq \dim G(x_i)$

for all

![]() $(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

, then

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

, then

![]() $E(x_i)\subseteq G(x_i)$

. In particular,

$E(x_i)\subseteq G(x_i)$

. In particular,

![]() $E\oplus (G\cap F) \oplus H$

is a dominated splitting over

$E\oplus (G\cap F) \oplus H$

is a dominated splitting over

![]() $\Lambda $

for f.

$\Lambda $

for f.

Proof. We can, without loss of generality, choose

![]() $\ell \geq 1$

such that

$\ell \geq 1$

such that

![]() $E\prec _{\ell } F$

and

$E\prec _{\ell } F$

and

![]() $G\prec _{\ell } H$

. Moreover, it follows from Remark 2.4 that

$G\prec _{\ell } H$

. Moreover, it follows from Remark 2.4 that

![]() $Df\mid _{H}$

is an isomorphism and

$Df\mid _{H}$

is an isomorphism and

![]() $\ker (Df^m_{x_i})$

must be contained in

$\ker (Df^m_{x_i})$

must be contained in

![]() $E(x_i)$

and

$E(x_i)$

and

![]() $G(x_i)$

, for each

$G(x_i)$

, for each

![]() $(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

and

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

and

![]() $m\geq 1$

.

$m\geq 1$

.

To conclude the proof of the proposition, it remains to show that if

![]() $u \in E(x_i)$

such that

$u \in E(x_i)$

such that

![]() $Df^m(u)\neq 0$

, for every

$Df^m(u)\neq 0$

, for every

![]() $m\geq 1$

, then

$m\geq 1$

, then

![]() $u \in G(x_i)$

. Then, for every

$u \in G(x_i)$

. Then, for every

![]() $u \in E(x_i)$

, one can decompose

$u \in E(x_i)$

, one can decompose

![]() $u=u_G+u_H$

in a unique way where

$u=u_G+u_H$

in a unique way where

![]() $u_G \in G(x_i)$

and

$u_G \in G(x_i)$

and

![]() $u_H \in H(x_i)$

. Analogously, one can decompose

$u_H \in H(x_i)$

. Analogously, one can decompose

![]() $u_H=u^{\prime }_E+u^{\prime }_F$

, where

$u_H=u^{\prime }_E+u^{\prime }_F$

, where

![]() $u^{\prime }_E \in E(x_i)$

and

$u^{\prime }_E \in E(x_i)$

and

![]() $u^{\prime }_F \in F(x_i)$

. Then

$u^{\prime }_F \in F(x_i)$

. Then

![]() $u^{\prime }_F$

must be zero. Otherwise, we get that

$u^{\prime }_F$

must be zero. Otherwise, we get that

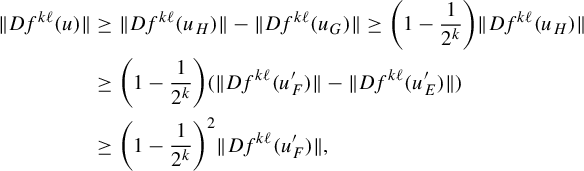

$$ \begin{align*} \|Df^{k\ell}(u)\|&\geq \|Df^{k\ell}(u_H)\|-\|Df^{k\ell}(u_G)\|\geq \bigg(1-\frac{1}{2^{k}}\bigg)\|Df^{k\ell}(u_H)\|\\ &\geq \bigg(1-\frac{1}{2^{k}}\bigg) (\|Df^{k\ell}(u^{\prime}_F)\|-\|Df^{k\ell}(u^{\prime}_E)\| )\\ &\geq \bigg(1-\frac{1}{2^{k}}\bigg)^2 \|Df^{k\ell}(u^{\prime}_F)\|, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \|Df^{k\ell}(u)\|&\geq \|Df^{k\ell}(u_H)\|-\|Df^{k\ell}(u_G)\|\geq \bigg(1-\frac{1}{2^{k}}\bigg)\|Df^{k\ell}(u_H)\|\\ &\geq \bigg(1-\frac{1}{2^{k}}\bigg) (\|Df^{k\ell}(u^{\prime}_F)\|-\|Df^{k\ell}(u^{\prime}_E)\| )\\ &\geq \bigg(1-\frac{1}{2^{k}}\bigg)^2 \|Df^{k\ell}(u^{\prime}_F)\|, \end{align*} $$

implying that

![]() $\|Df^{k\ell }(u)\|$

and

$\|Df^{k\ell }(u)\|$

and

![]() $\|Df^{k\ell }(u^{\prime }_F)\|$

have the same growth, which is impossible. Therefore,

$\|Df^{k\ell }(u^{\prime }_F)\|$

have the same growth, which is impossible. Therefore,

![]() $u_H \in E(x_i)\cap H(x_i)$

and

$u_H \in E(x_i)\cap H(x_i)$

and

![]() $u_G \in E(x_i)\cap G(x_i)$

. Symmetrically, we deduce that if

$u_G \in E(x_i)\cap G(x_i)$

. Symmetrically, we deduce that if

![]() $v \in G(x_i)$

whose

$v \in G(x_i)$

whose

![]() $v=v_E+v_F$

, then

$v=v_E+v_F$

, then

![]() $v_E \in G(x_i)\cap E(x_i)$

and

$v_E \in G(x_i)\cap E(x_i)$

and

![]() $v_F \in G(x_i)\cap F(x_i)$

. Moreover, since

$v_F \in G(x_i)\cap F(x_i)$

. Moreover, since

![]() $\dim E(x_i)\leq \dim G(x_i)$

, we have that either

$\dim E(x_i)\leq \dim G(x_i)$

, we have that either

![]() $G(x_i)=E(x_i)$

or

$G(x_i)=E(x_i)$

or

![]() $G(x_i)\cap F(x_i)\neq \{0\}$

.

$G(x_i)\cap F(x_i)\neq \{0\}$

.

Take non-zero vectors

![]() $u \in E(x_i)\cap H(x_i)$

and

$u \in E(x_i)\cap H(x_i)$

and

![]() $v \in G(x_i)\cap F(x_i)$

. Then, as

$v \in G(x_i)\cap F(x_i)$

. Then, as

![]() $G \prec H$

, we deduce that

$G \prec H$

, we deduce that

![]() $\|Df^{\ell }(u)\|$

grows faster than

$\|Df^{\ell }(u)\|$

grows faster than

![]() $\|Df^{\ell }(v)\|$

, which contradicts the fact that

$\|Df^{\ell }(v)\|$

, which contradicts the fact that

![]() ${E \prec F}$

. Thus, at least one of these intersections

${E \prec F}$

. Thus, at least one of these intersections

![]() $E(x_i)\cap H(x_i)$

and

$E(x_i)\cap H(x_i)$

and

![]() $G(x_i)\cap F(x_i)$

is trivial. Thus, we obtain that

$G(x_i)\cap F(x_i)$

is trivial. Thus, we obtain that

![]() $E(x_i)\cap H(x_i)=\{0\}$

. It implies that

$E(x_i)\cap H(x_i)=\{0\}$

. It implies that

![]() $E(x_i)$

is contained in

$E(x_i)$

is contained in

![]() $G(x_i)$

. To conclude the proof, we should observe that

$G(x_i)$

. To conclude the proof, we should observe that

![]() $G(x_i)\cap F(x_i)$

is invariant and

$G(x_i)\cap F(x_i)$

is invariant and

![]() ${E(x_i)\prec G(x_i)\cap F(x_i) \prec H(x_i)}$

.

${E(x_i)\prec G(x_i)\cap F(x_i) \prec H(x_i)}$

.

As a direct consequence of the previous lemma, we conclude the first part of the uniqueness of the dominated splitting.

Corollary 2.8. If

![]() $G\oplus H$

is a dominated splitting over

$G\oplus H$

is a dominated splitting over

![]() $\Lambda $

for f such that

$\Lambda $

for f such that

![]() ${\dim E=\dim G}$

, then

${\dim E=\dim G}$

, then

![]() $E(x_i)=G(x_i)$

for all

$E(x_i)=G(x_i)$

for all

![]() $x_i$

in the orbit

$x_i$

in the orbit

![]() $(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

.

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

.

To complete the proof of Proposition 2.6, we state the following.

Lemma 2.9. If

![]() $E\oplus F$

and

$E\oplus F$

and

![]() $E\oplus H$

are dominated splittings over

$E\oplus H$

are dominated splittings over

![]() $\Lambda $

for f, then

$\Lambda $

for f, then

![]() ${F(x_i)=H(x_i)}$

for all

${F(x_i)=H(x_i)}$

for all

![]() $x_i$

in the orbit

$x_i$

in the orbit

![]() $(x_i)_i$

in

$(x_i)_i$

in

![]() $\Lambda $

.

$\Lambda $

.

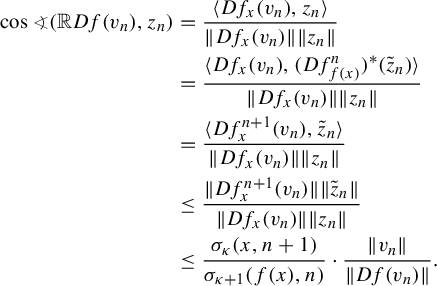

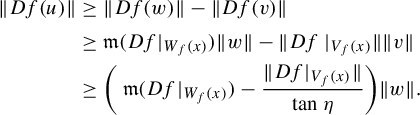

Proof. First, we assume that

![]() $(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

with

$(x_i)_i \in \Lambda $

with

![]() $x_i \notin \mathrm {Cr}(f)$

for all

$x_i \notin \mathrm {Cr}(f)$

for all

![]() $i \in \mathbb {Z}$

. Then, since

$i \in \mathbb {Z}$

. Then, since

![]() $Df_{x_i}:T_{x_i}M \to T_{x_{i+1}}M$

is an isomorphism, one has that for every unit vectors

$Df_{x_i}:T_{x_i}M \to T_{x_{i+1}}M$

is an isomorphism, one has that for every unit vectors

![]() $u \in E(x_i)$

and

$u \in E(x_i)$

and

![]() $v \in F(x_i)$

,

$v \in F(x_i)$

,

In particular,

![]() $F\prec _{\ell } E$

for

$F\prec _{\ell } E$

for

![]() $Df^{-1}$

along the orbit

$Df^{-1}$

along the orbit

![]() $(x_i)_i$

and, similarly,

$(x_i)_i$

and, similarly,

![]() $H\prec _{\ell } E$

for

$H\prec _{\ell } E$

for

![]() $Df^{-1}$

. Therefore, applying Corollary 2.8, one concludes that

$Df^{-1}$

. Therefore, applying Corollary 2.8, one concludes that

![]() $F(x_i)=H(x_i)$

since

$F(x_i)=H(x_i)$

since

![]() ${\dim F=\dim H}$

.

${\dim F=\dim H}$

.

In the general case, for a non-zero vector

![]() $u \in F(x_i)$

, one deduces that there are two vectors

$u \in F(x_i)$

, one deduces that there are two vectors

![]() $w \in E(x_i)$

and

$w \in E(x_i)$

and

![]() $v \in H(x_i)$

, with

$v \in H(x_i)$

, with

![]() $v\neq 0$

, such that

$v\neq 0$

, such that

![]() $u=w+v$

. Assume without loss of generality that

$u=w+v$

. Assume without loss of generality that

![]() $i=0$

. Then, using that

$i=0$

. Then, using that

![]() $Df\mid _F$

and

$Df\mid _F$

and

![]() $Df\mid _H$