Electoral gender quotas are increasingly common around the world. According to the Gender Quotas Database (International IDEA 2021), 129 countries have adopted some type of quota for national and/or local elections, contributing to the amelioration of women’s underrepresentation around the world (IPU 2015; O’Brien and Rickne Reference O’Brien and Rickne2016; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt‐Bayer2009; Tripp and Kang Reference Tripp and Kang2008). Quotas improve the descriptive representation of women not only by requiring a minimal level of legislative seats or candidacies, but also by redefining party elites’ perceptions of ideal candidates and by diversifying recruitment pools (Barnes and Holman Reference Barnes and Holman2020). In January 2022, the world average share of women in legislative lower houses was 26.4%, more than 10 percentage points higher than the 13.5% share in January 2000.Footnote 1

The global spread of gender quotas has sparked rich investigations in political science (cf. Krook and Zetterberg Reference Krook and Zetterberg2014). Existing studies offer various explanations for the adoption (and non-adoption) of gender quotas, emphasizing the critical roles played by women’s movements, partisan politics, and international actors (Caul Reference Caul2001; Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2006; Krook Reference Krook2009; Murray, Krook, and Opello Reference Murray, Krook and Katherine2012; Norris and Dahlerup Reference Norris and Dahlerup2015). One factor that underlies these explanations is public opinion, particularly evolving norms about equitable political representation. The fear of losing votes and pressure from civil society can push political parties to adopt quotas for strategic, electoral reasons (Franceschet, Krook, and Piscopo Reference Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012). Prior research shows that social and political attitudes are important predictors of quota support (Barnes and Cassese Reference Barnes and Cassese2017; Batista Pereira and Porto Reference Batista Pereira and Nathália2020; Beauregard Reference Beauregard2018; Beauregard and Sheppard Reference Beauregard and Sheppard2021; Galligan and Knight Reference Galligan and Knight2011; Gidengil Reference Gidengil1996).

That said, the determinants of citizens’ preferences regarding gender quotas are complex, as they are not easily reducible to self-interest or political ideology. One manifestation is the “principle-policy puzzle”: those who support egalitarian representation may nevertheless oppose affirmative actions to achieve them (Sniderman, Brody, and Tetlock Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991). The relationship between a principled commitment to gender equality and support for quotas is moderated by several factors. For example, different facets of sexism—benevolent, hostile, and modern—influence the degree to which voters support measures to improve women’s political representation. Another key factor is the perceived appropriateness of government intervention in achieving social aims (Barnes and Córdova Reference Barnes and Córdova2016). As legal gender quotas interfere in the decision-making of political parties, which would otherwise freely nominate candidates regardless of gender, some citizens may resist them on the grounds of civil liberty.

The reasons why citizens support or oppose gender quotas matter for both gender representation and the political sustainability of the quotas. Quotas remain controversial, and resistance to them can persist even after they have been implemented (Dahlerup and Freidenvall Reference Dahlerup and Freidenvall2010; Krook Reference Krook2016). If citizens regard political institutions—including gender quotas—as illegitimate, they may disengage from politics (Clayton Reference Clayton2015), leading to lower voter turnout and harming the quality of democratic representation.

To that end, this article investigates the mechanisms underlying citizens’ attitudes toward gender quotas through an original survey in Japan, which includes instruments that directly measure the perceived causes of women’s underrepresentation and the consequences of measures to alleviate it. Among G7 members, Japan and the United States are the only countries that have not implemented any binding gender quotas for legislative elections, contributing, in part, to the underrepresentation of women. In January 2022, women made up 9.7% of the lower house of the legislature and 22.9% of the upper house in Japan, and 27.3% and 25.0%, respectively, in the U.S. Congress, whereas the average shares in the lower houses of the remaining five G7 countries was 35.1%.

One reason why Japan is a valuable case for examining the degree of and reasons for quota support is that political actors have yet to mobilize voters on the issue itself. Japan’s Gender Parity Law, drafted by an all-partisan parliamentary group, was enacted in 2018 to encourage political parties to field an equal number of men and women candidates. It was amended to include sexual harassment prevention measures in 2021. The idea of binding targets was aborted because of resistance from the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), yet few legislators openly oppose the desirability of increasing women’s representation. According to a survey of lower house Diet members in 2022, only 1.5% of men (and 0% of women) stated that there was already sufficient gender parity (Shugiin Jimukyoku Reference Jimukyoku2022). That said, whether political parties should set a numerical target, much less a quota, has just gotten on the policy agenda in Japan, lessening the degree to which partisan cues may be driving preferences.

Our theoretical focus is the principle-policy puzzle: why a non-negligible segment of voters may want more women in the legislature but still oppose quotas. We show that this tension can be explained by two factors: modern sexism, or attitudes about the state of gender equality and women’s advancement (Swim et al. Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995), and beliefs about the appropriateness of government activism in gender matters. First, citizens’ understanding of discrimination against women in politics leads to their acceptance or rejection of gender quotas as a necessary response. Those who believe that structural barriers obstruct women from running for office are more likely to support gender quotas, whereas those who perceive that women are simply not interested in politics are more likely to oppose them. Furthermore, the belief that gender quotas would increase the number of unqualified women in political offices has a very strong negative association with quota support.

Second, we show that beliefs about the appropriateness of government activism in gender issues matter. Those who support greater state intervention, even in nonpolitical sectors, are also more likely to support quotas. As legal gender quotas intervene in the process of candidate nominations, those who are suspicious about the government taking an active role in civic life are more likely to dismiss gender quotas as a means to achieve gender balance in parliaments.

Importantly, we find that attitudes relating to modern sexism and government interventionism have a strong effect even among those who believe that there should be more women in the legislature. Even when citizens affirm the necessity of increasing the number of women in politics, this opinion does not necessarily translate into support for quotas—the heart of the principle-policy puzzle. One implication of our research is that to convince voters of the value of quotas, it is not enough to sell gender egalitarianism as a goal. Instead, it is essential to disseminate information about the actual effects of gender quotas, such as the fact that they actually increase the number of qualified women who run for office.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: The following section explores the case context in Japan, including past initiatives to improve gender parity and recent trends in elite and public opinion. The next section reviews the literature on the implementation of gender quotas, from which we derive testable hypotheses. Then we describe our survey research design and discuss the empirical results. The last section concludes with some implications of our findings for broader debates about ways to ameliorate gender disparities in politics.

Gender Inequality in Japanese Electoral Competition

Legal Context

Gender quotas are considered to be an effective means for improving the gender balance in legislatures, but their impact varies with their target and level of enforcement. The Gender Quotas Database (International IDEA 2021) provides comprehensive data on the diversity of gender quotas around the world. At the national level, 28 countries have adopted a reserved seat system, which allocates a certain proportion of seats to women, in the lower house. 65 countries have legislated candidate quotas that require political parties to field a certain percentage of women (or both women and men) candidates at the national and/or the local level. Political parties in 56 countries voluntarily use gender quotas when they endorse candidates. It is not unusual for two or three types of gender quotas to be used in a single country. Taken together, 129 countries used gender quotas of some kind as of January 2021. More than 30 countries have gone so far as to enumerate gender quotas or require equal electoral opportunities in their national constitutions.

Japan, on the other hand, has long resisted the adoption of gender quotas (Gaunder Reference Gaunder2015). Women’s organizations have called for quotas since at least the 1990s, but the quota movement gained enough strength to pressure political elites only when a women’s organization called Q no Kai (Association to Promote Quotas) was created in 2012 (Miura Reference Miura, Hardcare, George, Komamura and Seraphim2021). An all-partisan parliamentary group was formed in 2014 and drafted the Gender Parity Law, which was enacted with unanimous support in 2018. It urges political parties to field an equal number of men and women candidates in all elections. The law also encourages parties to take special measures, including numerical targets, to increase women candidates. Because the law is not binding, only some progressive parties have established such targets. In 2021, an amendment was passed in the Diet, again unanimously, that introduced a new clause to require legislatures and governments to prevent sexual harassment against women candidates and legislators.Footnote 2 While the all-partisan parliamentary group that drafted the original Gender Parity Law and its amendment had sought to make numerical targets compulsory, it gave up on that idea because of resistance from the long-ruling conservative LDP. Instead, it included several options that political parties are encouraged to adopt, such as improvements to the candidate endorsement process, providing training for women candidates, and adopting preventive measures against the sexual harassment of women.

A major reason for the LDP’s reluctance to set candidacy targets, despite calls to do so from some of its own women legislators, is intraparty constraints. For progressive opposition parties, quotas offer an opportunity to advocate their vision for gender equality. They are also in the minority and thus have fewer men incumbents. In order to win elections, they need to field many new candidates, which gives them room to implement numerical targets for women. The Japan Communist Party (JCP) has set targets of 30% for local elections and 50% for national elections. The Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) and the Democratic Party for the People (DPP) have set a 30% target for national contests. Indeed, even with the Gender Parity Law’s nonbinding mandate, the proportion of women opposition candidates increased slightly, from 22% in the 2017 lower house election to 26% in 2021. When looking solely at non-incumbents, the numbers are 24% and 30%, respectively.

By contrast, the LDP is predominantly male, including 92% of incumbents in the lower house and 85% in the upper house. Any numerical target would force a sizable proportion of LDP legislators to forfeit their seats, creating the risk of intraparty fissure. Moreover, the LDP’s candidate nomination process is highly decentralized, making it all the more difficult for national party leaders to impose numerical targets on its local branches. As incumbents are customarily granted automatic party endorsement, the LDP faces practical difficulties in setting a numerical target unless it drastically changes its endorsement process, especially in single-member districts. Its share of women candidates in lower house elections only increased from 8% to 10% between 2017 and 2021; among non-incumbents, the shares were just 7% and 15%. The exception is the open-list proportional representation (PR) tier of the upper house, in which voters can cast a vote either for an individual candidate or party. The LDP set a 30% target for proportional representation in the 2022 upper house election and achieved that goal, although open-list PR seats in Japan are considered to be difficult to win for inexperienced candidates.

Public Attitudes toward Quotas

Binding or compulsory gender quotas are still rare in Japanese government and society, although various actors have proposed voluntary targets. For example, the Cabinet Office of the executive branch has set various numerical goals to close gender gaps in a wide range of fields, including a 35% target for electoral candidacy by 2030. These targets, many of which were set in 2003, were ambitious from the start, and as of 2020, almost all decision-making bodies failed to pass this bar.Footnote 3 For example, the government was compelled to postpone the 30% target for women to take leadership positions across various sectors by 2020 to “as early as possible within the next decade.”

In Japan, the government has used the term positive action (“affirmative action” in American parlance), which mixes concrete quotas with aspirational goals and timetables. Thus, the term “quota” remains unfamiliar to many Japanese citizens. Neither corporations nor universities have used concrete quotas for their selection of managers or students, although some universities have recruited women on an ad hoc basis in order to redress gender imbalances in science and engineering faculties.

Public opinion data suggest that Japanese citizens do not give high credence to quotas, particularly mandatory ones. According to surveys by the Cabinet Office in 1995, 2000, and 2004 that asked respondents to choose appropriate “positive action” measures, only 20% to 23% of respondents selected voluntary candidate quotas by political parties. Quotas for companies’ recruitment and managers received slightly higher approval, between 19% and 30%.Footnote 4 A more recent survey of voters conducted by the University of Tokyo and Asahi Shimbun (UTAS; Taniguchi and Asahi Shimbun Reference Taniguchi and Shimbun2016) confirms this pattern. Its 2016 survey found that just 25% of men and 29% of women respondents agreed with the introduction of quotas to allocate a certain proportion of seats or candidacies to women.

That said, gender quotas are not an electorally polarizing issue, as seen by the ambiguous attitude of political elites. UTAS runs a parallel survey of election candidates, which includes identical questions to those asked of voters. Looking at the responses of victors in the 2016 upper house election,Footnote 5 42% of men and 65% of women winners agreed with the introduction of gender quotas, while 20% and 13% disagreed, respectively. Among LDP members, however, agreement was only 10% for men and 17% for women winners. Gender has a clear correlation with quota support: the agreement ratio of men and women politicians have statistically significant differences at the 5% level. We cannot realistically estimate gender differences by legislators’ party—something that Bohigues and Piscopo (Reference Bohigues and Piscopo2021) have shown in Latin American countries—as the number of elected women is very low. However, it is worth noting that 59% of men and 50% of women LDP respondents answered that they neither agreed nor disagreed with quotas. While we cannot discount social desirability bias on the part of legislators,Footnote 6 the high level of neutral responses suggests that elites are not eager to openly oppose quotas. This implies that elite partisan framing may be less salient on this topic, at least in Japan.

Theory: Determinants of Gender Quota Support

We are, of course, not the first to explore the determinants of public attitudes toward gender quotas. Past studies show that gender and partisanship are important predictors of individuals’ support for women’s political representation generally, and gender quotas specifically. Across national contexts, women are more likely to support the increased representation of women (Barnes and Córdova Reference Barnes and Córdova2016; Bolzendahl and Coffé Reference Bolzendahl and Coffé2020; Cowley Reference Cowley2013; Dolan Reference Dolan2004; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2003), even among elite-level actors (Bohigues and Piscopo Reference Bohigues and Piscopo2021; Meier Reference Meier2008). Sociodemographic similarities are “the simplest shortcut of all” (Cutler Reference Cutler2002), should voters prefer candidates who look like them. Self-interest also matters: women’s support for more women politicians derives from their expectation that they will benefit from women’s higher presence in politics (cf. Sears and Funk Reference Sears, Funk and Mansbridge1990). Values similarly play a role: women are more likely to commit to egalitarian values, which are correlated with quota support (Gidengil Reference Gidengil1996; Keenan and McElroy Reference Keenan and McElroy2017).

Partisanship must also be taken into consideration (Barnes and Cassese Reference Barnes and Cassese2017; Beauregard Reference Beauregard2018; Galligan and Knight Reference Galligan and Knight2011). Voters who support left-leaning progressive parties are more likely to support quotas than those backing right-leaning conservative parties, because the former parties tend to advocate equality and diversity more than do the latter. Moreover, left-leaning voters may be more supportive of government intervention in the private and public spheres, of which legislative quotas to correct gender imbalance are one type.

In this article, we go beyond these baseline differences in demographics and partisanship to identify how citizens’ understanding of the causes of women’s underrepresentation and the appropriateness of different remedies shape attitudes toward gender quotas. Notably, citizens’ normative beliefs about equality do not necessarily lead to their support for affirmative action policies. Even if citizens embrace equality as an ideal, they often reject the means through which it might be addressed. This puzzle, called the “principle-policy puzzle” (Sniderman, Brody, and Tetlock Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991) or “principle- implementation gap” (Dixon, Durrheim, and Thomae Reference Dixon, Durrheim and Thomae2017; Kane and Whipkey Reference Kane and Whipkey2009) has been mostly analyzed in the context of race. These studies find that prejudice toward minorities and ideologies regarding the appropriate role of government intervention jointly determine citizens’ approval of race-based affirmative action (Federico and Sidanius Reference Federico and Sidanius2002; Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996; Sniderman, Brody, and Kuklinski Reference Sniderman, Brody and Kuklinski1984).

In the context of gender quotas, the principle-policy puzzle best applies to those who (1) support more women in politics but (2) nevertheless oppose quotas. From past studies (Kane and Whipkey Reference Kane and Whipkey2009), we anticipate that gender attitudes measured by sexism and citizens’ support for government intervention are key underlying factors.

Benevolent, Hostile, and Modern Sexism

Previous scholarship offers insights into the role of gender beliefs. The question of whether to implement legislative quotas is inexorably tied to one’s views about the fitness of men versus women to serve in office, as well as women’s “appropriate roles” and “virtues.” Not surprisingly, those who hold gender-egalitarian attitudes tend to support gender quotas (Keenan and McElroy Reference Keenan and McElroy2017). However, the opposite attitude—sexism—needs to be analyzed with some nuance. For example, Glick and Fiske’s (Reference Glick and Fiske1996) seminal work posits the importance of differentiating “hostile” sexism from “benevolent” sexism. Hostile sexism represents antagonistic attitudes toward women, while benevolent sexism reflects paternalistic ideas about women’s role in society that relies on a “kinder and gentler justification of male dominance and prescribed gender roles” (Glick and Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske1996, 121).

Past studies show that hostile sexism is correlated with opposition to gender quotas (Keenan and McElroy Reference Keenan and McElroy2017) and women’s candidacy (Winter Reference Winter2022). By contrast, benevolent sexism can lead to support for gender quotas, because these can be a means to foster gender complementarities and stereotypes about women’s purity. Batista Pereira and Porto (Reference Batista Pereira and Nathália2020) show that those who embrace benevolent sexism tend to reject gender equality but support gender quotas. Similarly, Beauregard and Sheppard (Reference Beauregard and Sheppard2021) find that benevolent sexists are more likely to support gender quotas for “condescending and patronizing reasons,” such as that women need men’s assistance and protection. Women’s contribution in the private sphere justifies their participation in politics, as they are expected to bring “women’s perspectives” into policy making.

While these two well-used measures of sexism—hostile and benevolent—focus on women’s appropriate roles in society generally, modern sexism may be more relevant to understanding attitudes toward gender quotas. Modern sexism captures how respondents perceive and/or dismiss the very existence of gender discrimination and how this shapes their resentment toward those who are unhappy with the status quo. The original Modern Sexism Scale, developed by Swim et al. (Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995), consists of components that measure denial of continuing discrimination, antagonism toward women’s demands, and resentment about special dispensations toward women. The Modern Sexism Scale has been used to understand resistance to equality measures in various organizations, including universities (cf. Skewes, Skewes, and Ryan Reference Skewes, Skewes and Ryan2019) and workplaces (Archer and Kam Reference Archer and Kam2021), as well as concrete political behavior including voter turnout (Kam and Archer Reference Kam and Allison2021).

In the context of the principle-policy puzzle, modern sexism is particularly pertinent to understanding why some citizens support gender equality but nevertheless oppose quotas. They may believe that structural barriers to women’s entry have been resolved or that remaining inequalities are due to differences in the career preferences and efforts of women. They may also not agree with positive action measures as a remedy because of concerns about reverse discrimination.

For the purposes of our research, we measure modern sexism using survey items that have direct relevance to political processes and gender quotas in electoral democracy, rather than broader attitudes to gender inequality as captured by the Modern Sexism Scale. Two relate to beliefs about the reason for women’s underrepresentation. Prior research reveals a gender gap in people’s understanding of the causes of women’s relative absence. Women are more likely to attribute underrepresentation to structural-level factors, whereas men tend to focus on the level of individual women (Barnes and Córdova Reference Barnes and Córdova2016; Meier Reference Meier2008). Those who find fault with structural impediments, such as the gatekeeping role of political parties or the limited availability of resources such as money and time, are more likely to support gender quotas (Keenan and McElroy Reference Keenan and McElroy2017).

In order to examine the association between the perceived causes of gender imbalances and support for quotas, we directly asked respondents whether they believe that not enough women are recruited by political parties and/or are not interested in politics. From the foregoing discussion, we construct the following hypotheses.

H1 : A belief that underrepresentation occurs because parties do not actively recruit women is positively related to support for gender quotas.

H2 : A belief that underrepresentation occurs because women lack interest in politics is negatively related to support for gender quotas.

Beliefs about the effects of gender quotas on the quality of representative democracy should also affect citizens’ approval of such means. One naive fear of quotas is that they will lead to more unqualified people in office. A number of studies on gender quotas reveal that such changes do not take place after their adoption. Instead, women who are equally—if not more—qualified than men counterparts are more likely to step into a political career (Allen, Cutts, and Campbell Reference Allen, Cutts and Campbell2016; Besleyet al. Reference Besley, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017; Childs and Webb Reference Childs and Webb2012; Huang Reference Huang2016; Murray Reference Murray2010; Nugent and Krook Reference Nugent and Krook2016; O’Brien Reference O’Brien, Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012). In the Japanese context, Kage, Rosenbluth, and Tanaka (Reference Kage, Rosenbluth and Tanaka2019) show that voters do not find women candidates to be less competent than their men counterparts.Footnote 7

However, some voters may fear that the introduction of gender quotas would give unfair opportunities for unqualified women to win seats, as they may be unaware of findings in political science that deny such myths. Therefore, we construct the following hypothesis.

H3 : A belief that gender quotas would increase the number of unqualified women politicians is negatively related to support for gender quotas.

Government Interventionism

Even if one believes that women’s inequality is undesirable and its root causes are structural, there may be misapprehension about mandating gender parity through legislation. These relate to concerns about government overreach that are often captured as differences among progressives and conservatives (or libertarians) for “big” versus “small” government. Earlier research suggests that this dimension has important implications for gender quotas as well. Kane and Whipkey (Reference Kane and Whipkey2009) find that beliefs about the role of government in limiting economic stratification predict both men’s and women’s support for gender-related affirmative action in the United States. Similarly, Barnes and Córdova (Reference Barnes and Córdova2016) show that citizens’ normative beliefs about the role of government are important predictors of support for state-mandated gender quotas, independent of sex, gender-egalitarian attitudes, and ideology.

We take this view one step further and measure beliefs about the appropriate roles of government in social policy. Citizens have distinct preferences about the degree to which government should intervene in the private sector to realize egalitarian outcomes. As far as gender equality is concerned, government can affect not only women’s participation in politics, but also women’s social status on matters such as marriage, parenting, or sexual harassment.

We thus hypothesize that those who support government intervention to ensure gender equality in general should be more likely to also support quotas to achieve gender-balanced representation in parliament. Mandatory quotas are a particularly strong intervention, as political parties are forced to nominate a certain number of women candidates. Those who agree with state intervention, particularly in sociocultural matters, should be more comfortable with such laws, whereas those who are skeptical of government intervention should be more hesitant. Our survey incorporates items to assess respondents’ attitudes toward such intervention in the context of gender.

H4 : Support for greater government intervention in achieving an equal society is positively related to support for gender quotas.

Survey Design and Results

In order to test our hypotheses regarding citizens’ attitudes toward gender quotas, we conducted a survey of Japanese citizens between February 27 and March 11, 2020. Respondents were recruited by Rakuten Insight, one of the largest online survey providers in Japan, with quota sampling based on residence (prefecture), gender, and age (18–75) to match the 2015 national census distributions. The total number of valid responses, which excludes those who did not complete the survey, is N = 3,773. Because all questions included a “don’t know” option or allowed respondents to proceed without answering the question, the sample size in each model analyzed here varies slightly. Further details regarding our survey methodology and research ethics are available in Appendix A in the Supplementary Materials online. Descriptive characteristics of our survey respondents, including age, gender, and partisanship, is available in Appendix Table B1.

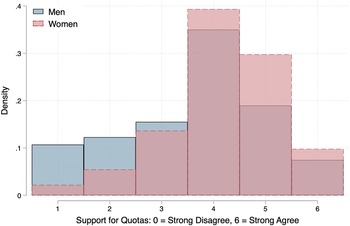

Our main dependent variable is Diet quota, which is the response to the following question: “Do you agree or disagree that a quota system should be introduced in law to achieve gender equality in politics?” Responses were given on a 6-point Likert scale: strong disagree (1), disagree (2), weak disagree (3), weak agree (4), agree (5), strong agree (6). Figure 1 shows the distribution of responses by gender. Women were more likely to rate quotas positively: the average scores of quota support were 3.51 for men (SD = 1.41) and 4.10 for women (SD = 1.15). When converted into binary yes/no responses, 58.1% of men gave an affirmative answer (strong support, support, weak support), compared to 75.2% of women.

Figure 1. Support for Diet quotas. Figure shows the distribution of responses to the following question: “Do you agree or disagree that a quota system should be introduced in law to achieve gender equality in politics?” Responses were given on a 6-point Likert scale, with higher values denoting greater agreement. Responses by men respondents are shown in blue (solid outline); those by women respondents are in red (dashed outline).

Table 1 shows the breakdown of responses by gender, age, and partisanship, which previous studies have identified as important correlates of quota support. It also denotes categories in which differences by gender are statistically significant. Women are more likely to support quotas than men across all age groups except for those in their 70s. In addition, while Diet quota for men is relatively flat across age groups, it trends downward for women. While younger and older men do not vary significantly in their preferences, younger women are significantly more likely to support quotas than older women. This pattern may be related to cohort differences in gender role attitudes among women, as predicted by modernization theory. Beliefs about gender roles shift over time gradually, often in response to socialization under different environments (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2003).

Table 1. Support for Diet quotas by partisanship and gender

+ p < .1; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Notes: Mean scores for support for Diet quota by age decile and party affinity. Stars denote cases in which the difference between men and women is statistically significant. We restrict the presentation of partisan differences to parties that won more than 5% of votes in the 2021 lower house election.

On partisan affinity, we find expected differences by the ideological orientation of parties. As discussed earlier, supporters of progressive/left-leaning parties are more likely to support gender quotas than those of conservative/right-leaning parties. Our survey asked respondents to select their preferred party from a list of 12 options. Table 1 lists attitudes toward quotas for supporters of parties that won more than 5% of the vote in the 2021 lower house election.Footnote 8 The largest party in the Diet is the conservative LDP, which is currently in a coalition government with the centrist Komeito. There is one opposition party that is considered center-right or right-wing: Nippon Ishin. Three opposition parties can be categorized as left or center-left in policy orientation: the CDP, DPP, and JCP. Independents include respondents who answered that they support “no party.”

Regardless of gender, supporters of the conservative LDP and Nippon Ishin are less likely to support quotas than are supporters of left-leaning parties. The centrist Komeito, while in coalition with the LDP, is considered to be more progressive on sociocultural issues, and this is borne out by its relatively high level of quota support. The estimates for independents lie between conservative and progressive parties. It is also worth noting that gender differences within parties remain significant. Support for quotas is below the middle level of 3.5 among men LDP and Ishin partisans, but above it for their women counterparts. In fact, the predicted support for quotas between LDP and Ishin women and left-leaning men are very close. This suggests that partisanship does not entirely determine or proxy for how Japanese citizens value legislative quotas.

One hurdle to testing our hypotheses is that many of the underlying factors are correlated, complicating how we interpret the coefficients of the key explanatory variables. For example, partisanship varies significantly by gender. In all, 41% of men respondents support the LDP, while 33% are independents; among women respondents, these shares are 26% and 52%, respectively. Similarly, we may expect the socialization of gender attitudes to differ between birth cohorts or educational attainment. At the same time, some of our explanatory variables are direct responses to specific questions, such as party affinity or age. Others, particularly relating to sexism, are estimates of latent scales, derived from multi-question batteries. In short, a multiple regression framework that throws in all variables may be unsuitable, given expected multicollinearity. A correlation heat map, showing the correlation matrix between key independent variables, can be found in Appendix C.

Accordingly, we test each hypothesis separately. Each subsection that follows examines each set of hypotheses individually, including a detailed discussion of how relevant variables are operationalized. Descriptive statistics of variables, estimated separately by gender, can be found in Appendix B. The results presented here do not include control variables for age or party identification. However, the results of models that do so are included in Appendix D; we do not find major substantive or statistical differences due to model specification.

Benevolent versus Hostile Sexism

Views on equitable gender representation are shaped by fundamental social attitudes toward the role of women in society. Our theoretical focus is the role of “modern sexism,” as discussed earlier, but we begin by confirming whether patterns found between ambivalent sexism and quota support in other contexts also apply to Japan. We analyze the relationship between benevolent and hostile sexism and Diet quota, drawing on a battery of questions taken from the Japanese translation of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory. Ui and Yamamoto’s (Reference Ui and Yamamoto2001) instrument includes 22 items, from which we select 6 with the highest factor loadings. Responses were given on a 6-point Likert scale (cf. Appendix Table B2). The first three items relate to benevolent sexism, while the next three relate to hostile sexism.

B1: Women are better at caring for vulnerable people than men.

B2: When mothers have full-time jobs, I feel sorry for their small children.

B3: Being a housewife can be as fulfilling as a job that earns an income.

H1: University education is more important for boys than girls.

H2: When employment opportunities are limited, men should be given preference for jobs over women.

H3: In general, men are better suited as political leaders than women.

In order to estimate latent dimensions of these two sexism types, we calculate the mean responses to the benevolent (Q1–3) and hostile (Q4–6) sexism questions. Scales are reversed from the original, such that higher values denote greater sexism. On benevolent sexism, the mean response for men is 3.46 and for women is 3.33; their difference (–0.13) is statistically significant at conventional levels (t = 4.07). On hostile sexism, the mean response for men is 3.11 and for women is 2.65; their difference (–0.46) is also statistically significant (t = 12.55). As the level of mean responses suggests, benevolent sexism is more prevalent than hostile sexism. The correlation between these two variables is a moderate 0.38.

We run separate models for men and women respondents, regressing Diet quota against the benevolent and hostile sexism scores. In lieu of predicted levels of quota support, Figure 2 shows the marginal change in Diet quota from a 1-point increase in each sexism score. For both men and women respondents, hostile sexism reduces support for gender quotas at statistically significant levels. On benevolent sexism, however, men with higher scores are more likely to support quotas, but the coefficient for women is statistically insignificant. In a separate model that collapses men and women respondents together, we find that benevolent sexism overall has a positive and statistically significant effect on Diet quota. Raw regression results, including for models that include partisan affinity and age as control variables, can be found in Appendix Table D1.

Figure 2. Benevolent and hostile sexism and quota support. Figure shows the marginal change in support for legislative gender quotas by benevolent and hostile sexism, estimated separately for men and women respondents. Estimates for men respondents are in blue; those for women respondents are in red. Markers denote point estimates, and bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Our result confirms the pattern observed in other countries such as Ireland (Keenan and McElroy Reference Keenan and McElroy2017), Brazil (Batista Pereira and Porto Reference Batista Pereira and Nathália2020), and Australia (Beauregard and Sheppard Reference Beauregard and Sheppard2021). The addition of Japan in the study of sexism and quota support indicates the robustness of the impact of these two variants of sexism. We also find that the impact of benevolent sexism on women is insignificant. This suggests that Japanese women do not consider gender differences in virtues or attributes to be a reason to ensure more women in politics, whereas men do, perhaps for paternalistic reasons. This may reflect the asymmetrical position of men and women in Japanese society.

Modern Sexism

We now move to our test of three hypotheses about modern sexism that directly address beliefs that underlie support or opposition to gender quotas. Citizens’ preferences are likely to vary with their perception of why women’s representation has been impeded. If they believe that the cause is attributable to structural factors, such as the failure of parties to actively recruit women candidates ( H1 ), then they may see quotas as a reasonable means to ameliorate gender imbalances. If they believe that the fault is with women themselves, such as their lack of interest in politics ( H2 ), then they may be less favorable.

To test these relationships, we asked respondents whether they agreed (dichotomous yes/no) with two statements relating to the perceived causes of women’s underrepresentation.

-

(1) Few women are interested in politics. (69.6% agreement)

-

(2) Political parties are not serious in their recruitment of women. (78.9% agreement)

H3 posits that respondents would be less likely to support quotas if they perceive the cure to be worse than the disease. We asked respondents whether they agreed with the following statement on a 6-point Likert scale, which we converted into a binary indicator so that coefficients are comparable to those for (1) and (2):

-

(3) If quotas become compulsory, the number of unqualified women candidates will increase. (67.2% agreement)

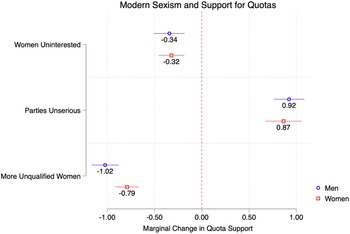

We include all three variables simultaneously as covariates in ordinary least squares regressions, with Diet quota as the dependent variable. Figure 3 shows the marginal change in support for quotas when each variable takes the value of 1 (i.e., agreement).Footnote 9 All have clear, predicted effects on quota support, with similar magnitudes across gender. Regarding the causes of women’s underrepresentation, those who attribute it to women’s lack of political interests are –0.34 (men) and –0.32 (women) points less likely to support quotas. The effect estimates are reversed for those who believe that parties are not recruiting women seriously, at +0.92 and +0.87 points greater support, respectively. In substantive terms, the starkest relationship is for unqualified women. Among men who agree that quotas will increase the number of unqualified women legislators, support for gender quotas falls by an astounding –1.02 points; for women, the coefficient is –0.79.Footnote 10

Figure 3. Modern sexism and support for quotas. Figure shows the marginal change in support for legislative gender quotas (6-point Likert scale) by perceived reasons for women’s underrepresentation and the potential effects of gender quotas, conditional on respondent gender. Responses by men respondents are in blue; those by women respondents are in red. Markers denote point estimates, and bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Collectively, the results presented in Figure 3 indicate that modern sexism is a strong predictor of support for gender quotas. Those who attribute women’s underrepresentation to women themselves do not think that quotas are necessary, while those who associate it with political causes such as stunted elite recruitment are in favor of quotas. Consequences also matter: those who believe that quotas will decrease the quality of political representation oppose quotas. While this linkage is perhaps not surprising, it speaks to the need for more communication, particularly by academics, that this supposed relationship is not borne out by comparative evidence. We return to this point in the conclusion.

Government Interventionism

A separate reason for opposition to gender quotas may be apprehension about inviting state intervention in political affairs, particularly on the decision-making freedom of political parties. Even if voters seek more diverse legislatures, they may not see direct government mandates as an appropriate price to pay—that is, the ends may not justify the means. By contrast, those who generally support direct government intervention may be more likely to also back gender quotas, as posited by H4 .

To isolate the effects of beliefs about the appropriateness of government intervention, as opposed to general left-right political ideology, our survey instrument included four questions relating to statutory requirements to improve gender diversity in nonpolitical spheres. These include support for (1) mandatory paternity leave, (2) same-sex marriage, (3) not requiring surname changes upon marriage, and (4) penalties for sexual harassment. The breakdown of responses to these questions is available in Appendix Table B3. While attitudes toward government activism in the private sphere can span multiple policy dimensions, including religion, race/ethnicity, and education, we purposefully chose items that relate to gender, so as to better assess its linkage to gender quotas in particular.

We use these responses to estimate a single latent dimension of support for government intervention, based on a graded response model that draws on item response theory. Interventionism has a mean of 0.00 and a standard deviation of 0.82; higher values are correlated with greater agreement with each of the four questions above. For ease of analysis, we collapse this latent dimension into quartiles, which we label “strong passive,” “weak passive,” “weak active,” and “strong active.”Footnote 11

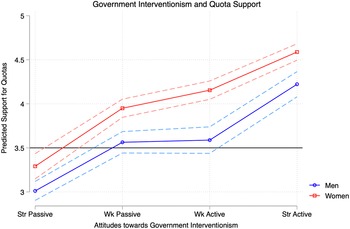

Figure 4 depicts the predicted level of Diet quota at each quaternary level of interventionism, conditional on gender.Footnote 12 As support for government intervention increases, so does support for gender quotas. Among men, the predicted levels between “strong passive” and “strong active” interventionists are 3.01 and 4.22, respectively; for women, this is 3.29 and 4.59, respectively. In other words, Diet quota increases by more than 1 point (on a 6-point scale) between those who strongly oppose versus support government intervention. This corroborates our contention in H4 that a key explanatory factor in support for quotas is beliefs about the appropriateness of government intervention to achieve greater gender egalitarianism in the legislature.

Figure 4. Government interventionism and quota support. Figure shows the predicted level of support for legislative gender quotas by support for government interventionism (4-point scale), conditional on respondent gender. Responses by men respondents are in blue; those by women respondents are in red. Solid lines denote predicted levels, and dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Principle-Policy Puzzle

Not all citizens who seek more women in the legislature support gender quotas. The literature has long noted this “principle-policy puzzle”: those who want more political diversity—whether based on race, religion, or, in our case, women—do not necessarily believe that this should be achieved through quotas. To estimate the extent to which this phenomenon is pertinent to Japan, we examine how the effect of our main explanatory factors—modern sexism and interventionism—are moderated by a desire for a more egalitarian legislature.

Our survey asked respondents for their ideal percentage of women in the Diet (range 0–100). The average percentages were 37.8 for men (median = 35, SD = 13.8) and 40.3 for women (median = 40, SD = 12.9). In general, those who desire more women politicians also support quotas, with a correlation coefficient of 0.324. That said, while 58.3% of respondents believe that women should comprise more than 40% of the Diet, of those, 23.9% nevertheless oppose gender quotas.

Here, we estimate Diet quota as a function of the interaction between respondents’ stated ideal percentage of women and our three variables for modern sexism (women uninterested, parties unserious, and unqualified women) and one variable for government intervention, as well as their respective additive terms. For ease of comparison, we convert intervention into a binary term that equals 1 if the original latent score is greater than 0, and 0 otherwise. Separate regressions are run for each of the four key variables. The raw regression coefficients can be found in Appendix Table D2.

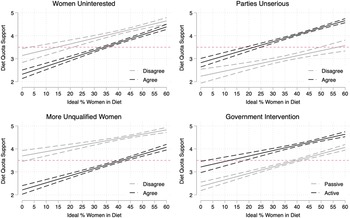

Figure 5 presents the results as four separate panels, one each for our four explanatory factors. Each line depicts the predicted level of Diet quota as a function of the ideal percentage of women in the Diet, conditional on agreement (black) or disagreement (gray) with each sentiment. Dashed lines are 95% confidence intervals. There are three points to note about these results. First, all slopes are positive, indicating that support for quotas increases among those who seek more women in the Diet. Not surprisingly, those who desire a more egalitarian legislature are generally more supportive of quotas as a means to achieve that aim.

Figure 5. Quota support and the principle-policy puzzle. Figure shows the predicted level of support for legislative gender quotas by the desired percentage of women in the Diet, conditional on agreement with the following four statements. Top-left panel: women’s underrepresentation is due to women’s disinterest in politics. Top-right panel: women’s underrepresentation is due to the lack of pro-egalitarian recruitment by political parties. Bottom-left panel: quotas will increase the number of unqualified women politicians. Bottom-right panel: support for active government intervention in gender affairs. Black lines denote those who agree with the statement; gray lines denote disagreement. Solid lines are predicted levels, and dashed lines are 95% confidence intervals.

Second, the slopes conditional on statement agreement are roughly parallel, suggesting that the main distinction is that of levels or intercepts. There are baseline differences in Diet quota, such that those who espouse modern sexism and oppose government interventionism are less supportive of gender quotas. This difference remains even as the desired percentage of women legislators increases, although the lines begin to converge for the variable women uninterested.

Third, the level of ideal percentage of women at which each slope is significantly above 3.5 (the middle level on the 1–6 scale) varies by the moderator. Among those who agree that unequal representation is due to women’s disinterest (top-left panel, black line), support for quotas goes into positive territory (above 3.5) when the ideal percentage of women is above 37%. For those who disagree that parties are unserious about recruiting women candidates (top-right panel, gray line), the predicted level is higher than 60%. For those who agree that quotas will increase the number of unqualified women legislators (bottom-left panel, black line), it is 45%. Finally, for those who are opposed to government interventionism on gender matters (bottom-right panel, gray line), the ideal percentage of women in the Diet needs to surpass 43% before the predicted level of Diet quota is in positive territory.

The main takeaway from this analysis is that to increase support for gender quotas, convincing citizens to support more women in the legislature is insufficient. For those who reject modern sexism and are open to government interventionism in gender matters, support for quotas is high at even moderate levels of desired parliamentary egalitarianism. Instead, the key hurdle is to convince people that parties can still do more to nominate women, that structural barriers for women legislators are real, and that gender quotas will not produce less qualified representatives. The first factor—elite recruitment—may deserve particular attention, given that those who think parties are doing enough already are least likely to support quotas, even when they want more women legislators (Figure 5, top-right panel).

As we discuss next, these attitudes may change in response to educational campaigns that inform citizens about structural societal constraints and rectify unwarranted concerns. The same may be said about convincing people to accept greater government intervention, but this attitude may be closer to a more fundamental political value that is less mutable. At a minimum, more research is necessary to determine how preferences about positive action are shaped, both in general and more specifically in Japan.

Conclusion

Our analysis of Japanese survey data on support for gender quotas confirms extant theories relating to differences by demographic and partisan factors. As has been found in other national contexts, women (particularly young women), and supporters of left-leaning parties are more supportive of quotas than men and right-leaning partisans. Similarly, we show that benevolent sexists are not opposed to quotas, while hostile sexists are.

This article’s main contribution is going one step further to elucidate the underlying beliefs that motivate these differences. First, we test the relationship between quota support and modern sexism, using survey items that directly measure sexism in a political context. We confirm our hypotheses that those who believe that political parties have not done enough to promote women support quotas, but those who believe that women are less interested in politics do not. Our results also show that citizens who think that gender quotas will reduce the quality of political representation oppose quotas.

Second, our research demonstrates a strong relationship between quota support and beliefs about government intervention. We measure the latter by respondents’ acceptance of government intervention in gender matters in the private sphere. Those who oppose active government intervention tend to be less supportive of legislative quotas.

Lastly, we find that the principle-policy puzzle holds true for legislative gender quotas. Even among respondents who desire more women in parliament, those who espouse a greater degree of modern sexism or stronger resistance to government intervention are less likely to support quotas. Put differently, these citizens only agree with legislative quotas when they also prefer a much higher ratio of women in the Diet, with that tipping point ranging from 37% to 60% depending on the factor.

Our findings point to the need for measures to correct misperceptions. The belief that women do not run for government because they lack interest or ambition implies ignorance about the obstacles that women face in politics. This includes societal gender norms that penalize women candidates (cf. Dolan Reference Dolan2004; Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2010; Ono and Yamada Reference Ono and Yamada2020; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002), as well as the decisive role of political parties in candidate recruitment and selection (cf. Ashe Reference Ashe2019; Bjarnegård and Kenny Reference Bjarnegård and Kenny2015; Dittmar Reference Dittmar2015; Hinojosa Reference Hinojosa2012). According to our analyses, among those who think that parties are already doing enough to recruit women candidates, support for quotas tilts to positive only when their desired level of women in parliament is higher than 60%. This unrealistically high proportion suggests the importance of informing citizens about the gatekeeping role of parties in recruiting more women.

In addition, pro-quota groups may want to emphasize that there is little evidence that quotas will increase the number of unqualified women. If anything, research shows that the average quality of politicians improves (Allen, Cutts, and Campbell Reference Allen, Cutts and Campbell2016; Besley et al. Reference Besley, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017; Childs and Webb Reference Childs and Webb2012; Huang Reference Huang2016; Murray Reference Murray2010; Nugent and Krook Reference Krook2016; O’Brien Reference O’Brien, Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012). To reiterate, our analyses imply the need for further informational campaigns, including better education about structural gender discrimination, the decision-making criteria (and biases) of parties, and the effects of quotas in other countries.

Citizens’ belief about the appropriate role of government may be harder to change, as it is a deeper “principle” about state-society relations rather than a softer “policy” preference. If gender quotas are perceived to be excessive government intervention, then their implementation may provoke mistrust about the quality of democratic governance. This may, in turn, have knock-on effects on political participation, such as voter turnout, and the perceived legitimacy of public policies. One avenue for further research is to explore whether different types of quotas, which vary in the level of government enforcement, provoke similar responses. For example, among those who oppose government intervention, increasing subventions (state subsidies) to parties that nominate more women may be more palatable than implementing a mandatory quota that prohibits parties from nominating less than the requisite number of women. In the Japanese context, there have been some discussions about establishing numerical targets whose percentage or deadlines can be freely set by parties, which may be less objectionable to many citizens.

Debates over legislative quotas have been percolating through the political agenda in Japan. As mentioned earlier, even the LDP introduced a numerical target of 30% for the PR tier of the 2022 upper house election. Political debate is slowly but steadily moving toward stronger measures to achieve gender parity in parliament. Our study suggests that demystifying the causes of gender inequality and the consequences of gender quotas, such as alleviating fears that they will increase unqualified women in office, may contribute to public support. This should reduce parties’ resistance to legal quotas, or at least make it more difficult to justify opposition to quotas on the grounds of democratic quality. Academic work by gender quota scholars, if widely known, can shape citizens’ views and political elites’ perception. Production of high-quality knowledge as well as rich communication between academia and civil society would advance our society in an egalitarian and diversified direction.Footnote 13

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X22000617.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the ISS Political Science Workshop and the WondeR Workshop. We thank Sarah Childs, Gregory Noble, Ki-young Shin, Jackie F. Steele, and Hiroto Katsumata for their comments. This article received funding from MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI 18H00817. Our survey received approval from the Research Ethics Review Board of the Institute of Social Science, University of Tokyo (see Appendix A for details).