Introduction/background

The use of robust research into patients’ needs, preferences, and experiences, as well as patient participation are the recommended approaches to ensure that the patient perspective is included in value determination in the health technology assessment (HTA). Increasingly, communication of patients and caregivers on social media (highly interactive mobile or web-based platforms through which individuals or communities share, co-create, discuss, and modify user-generated content) is used by patient organizations, industry, or other stakeholders as a source for such research. In relation to HTA, the findings may support the early scientific advice interactions or as part of the submission dossiers to both regulatory and HTA agencies for approval purposes.

The benefits of using Social Media Research for identifying patients’ needs, experiences, and preferences can be related to the unsolicited and open nature of the shared information, as well as the broad coverage of the patient population as compared to individual input or focus groups. However, Social Media Research is prone to certain risks and biases due to the personal nature of the information shared on social media. Particular sensitivity relates to ethical and legal aspects concerning the privacy and protection of the people who communicate and of other people they may communicate about (Reference Samuel, Derrick and van Leeuwen1). Currently, there is a lack of guidance on how to conduct Social Media Research appropriately to meet the ethical standards and the legal requirements of privacy protection as required for supporting HTA or healthcare policy decisions. This gap may be due to the innovation frequency of the communication media, the different ways of how they are used by all stakeholders and the research methods applied to analyze them. The media used by individuals to share views and to publish material online, the search engines available to users, and the approaches for conducting research with these communications are constantly evolving.

On the other hand, Social Media Research is conducted by a variety of disciplines that may not yet adhere to common guidance or “best practices,” including sociology, computer science, media/communications studies, public health research, and allied fields, but also others such as market research, epidemiology, anthropology, or bioethics. The varied aims and perspectives lead to high diversity in ethical standards which are applied across studies on all levels of the research ecosystem: among researchers, research groups, research entities, review boards, funding councils, publishing bodies, and nations (Reference Samuel, Derrick and van Leeuwen1).

Together with the increase of research on social media, examples of misuse of these data are surfacing. This triggers actions such as increased control for access to closed group on proprietary sites, restrictions for data sharing, closed access to data only within proprietary systems precluding use by external or independent researchers (Reference Ravn, Barnwell and Barbosa Neves2). These measures strengthen data privacy protection but may hinder the conduct of Social Media Research.

A consensus on the requirements to be met in the planning and conduct of Social Media Research to achieve a high level of protection for the users of social media while enabling Social Media Research in a way that it benefits the patients and healthcare systems would help researchers and users of the research results in improving or assessing the quality of the research. The aim of this report is to summarize the current academic discourse of ethical issues and standards, and to advance this discussion and guidance in order to foster the robustness and integrity of Social Media Research for informing regulatory, HTA or health policy decisions.

Methods

A literature search was conducted in PubMed and Embase with the following search strategy: (Research OR Listening OR Mining) AND (Social Media) AND (Legal OR Privacy OR Ethical OR Ethics). Non-relevant publications were eliminated in three steps: (i) a title screen; (ii) classification of remaining publications by three reviewers as “include,” “exclude,” or “potential” based on the following criteria (a) containing information relating to ethical, privacy or legal issues related to research in social media and (b) related or relevant to the use of the research for informing regulatory or other assessments of technologies or for healthcare policy decisions; and (iii) conflicts in classification were resolved by discussion. Each reviewer reviewed and summarized the findings of one-third of the articles classified as “include” or “potential” and made a final decision for inclusion.

The occurring themes were grouped by themes of ethical and privacy-related challenges, or by reported principles and guidance on the conduct of the Social Media Research. The occurring themes were mapped into the relevant items on a mapping software (MIRO). In this way, the three researchers were able to enrich existing or create new themes and substantiate them with the text from the publications. A summary of all extracted information including all references is available in the online supplementary material (Supplementary file 1).

The main challenges as reported in the scientific literature were summarized together with the proposed measures for mitigation. The identified themes and some of the strategies proposed in the literature were further developed through classification of the privacy and ethical aspects to propose a list of principles for the conduct of Social Media Research, and to provide a short checklist of the critical considerations to mitigate specific privacy and ethical risks.

Results

The process of the scoping review is reflected in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) diagram in Figure 1. Of the 1306 references retrieved in the general literature search, 935 were published between 2017 and April 2021. The first title screen excluded 825 references. Of the remaining 110 references, 38 were classified as “Exclude,” 33 as “Include” and 38 as “potential.” Finally, based on the full-text articles, the extracts of 41 publications were used in the thematic analysis. The main themes presented in this report are (i) definitions of social media research, (ii) ethical aspects, (iii) privacy, (iv) informed consent, (v) anonymity and confidentiality, (vi) authenticity and justice, (vii) beneficence and non-maleficence, (viii) context, and (ix) ethical review.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram for the scoping review.

Definition of social media research

For the purposes of this report, Social Media Research is defined as research with data originating from any social media platforms including, but not limited to Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Reddit, blogs, and chatrooms or forums (closed/password-protected and open/non-password-protected). As the method of research, this may refer to large quantitative data mining/modeling methods through to more qualitative in-depth analyses. The aims of Social Media Research generally are to reveal new insights into information sharing or policy discussions, to understand personal experiences and opinions or sentiments from the individual or patient community perspective, to conduct epidemiological studies, to identify and detect adverse events or other clinically relevant reports, or to observe online behavior in general.

Ethical aspects

Due to the fluidity of uses and content within online settings, existing guidelines such as the ones produced by the Association of Internet Researchers (AoIR) advise a deliberative, “bottom-up” approach to research ethics that allows for differing disciplines and research contexts, as opposed to providing a “top-down,” universal set of principles and regulations. Researchers are advised to engage in a deliberative process when making ethical decisions about online research, taking into account the vulnerability of online data and balancing the rights of authors (who might be considered “communities,” “authors,” or “participants”) against the potential benefit of the research (Reference Franzke, Bechmann, Zimmer and Ess3).

Privacy, anonymity and confidentiality, authenticity, and (rapidly changing) technologies for communication, data collection, and analysis have been identified as key themes in the ethical appraisal of Social Media Research (Reference Hunter, Gough and O’Kane4).

In addition, to improve consistency, quality, and integrity of ethical assessments over time, a requirement for a review by research ethics committees for all social media research has been suggested by Samuel and coauthors – even if it often may be declared exempt in the ethical review process (Reference Samuel, Derrick and van Leeuwen1).

Privacy

Privacy has been declared a human right by the United Nations. Privacy means “freedom from unauthorized intrusion” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/privacy) and, in more detail, “freedom from damaging publicity, public scrutiny, secret surveillance, or unauthorized disclosure of one’s personal data or information, as by a government, corporation, or individual” (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/privacy).

What is authorized in social media, is usually described in the privacy settings, which generally are constantly refined through resetting of user-chosen settings, leaving users resigned under the insurmountable task to understand them, maintain control, and ensure the protection of their own data. In addition, hidden in the jungle of legal text, service providers often secure the right for tracking and reusing the material at their own liberty. As Hunter and coauthors point out, “… public health researchers must recognize the self-serving interest of Social Media corporations and work within ethical principles that protect individual users, who are often powerless and uninformed in the labyrinthian Social Media environment” (Reference Hunter, Gough and O’Kane4).

Therefore, researchers and ethics review committees need to be guided and trained to minimize the risk to any of the people included or concerned by the research.

Informed consent

In clinical research, human subjects voluntarily confirm that their data can be used in a particular study, after having been informed of all aspects of the trial that are relevant to the subject’s decision to participate. However, the need for such consent in Social Media Research is debated and there is a controversy between data manifested public by the posts’ authors and the need for consent for extraction and processing (Reference Ravn, Barnwell and Barbosa Neves2–Reference Audeh, Bellet, Beyens, Lillo-Le Louët and Bousquet5;Reference Nicholas, Onie and Larsen6).

Collecting the consent retrospectively for thousands of posts from a large number of individuals may not be feasible, and in addition, the consent may be implied in the terms and conditions of the use of platforms or by the public nature of the posts (Reference Nicholas, Onie and Larsen6;7). The dilemma is that the use may be legal according to the user terms but not legitimate according to “human rights.” Patients posting data on publicly accessible social media are not always comfortable with these data to be used for specific research purposes, and generally, users do not pay attention or do not understand the implications of the terms of use (Reference Hunter, Gough and O’Kane4–Reference Ford, Curlewis, Wongkoblap and Curcin8).

Anonymity and confidentiality

Data processing, security, and management must respect the applicable data protection legislation (national/local plus wider legislation, such as on European level, where applicable) (Reference Hunter, Gough and O’Kane4;Reference Audeh, Bellet, Beyens, Lillo-Le Louët and Bousquet5).

In responsible social media research, users and third parties they may communicate about (e.g., parents communicating about the health of their children) must be protected against any potential risk for re-identification and against intrusion into their personal spheres (Reference Chiauzzi and Wicks10). A special challenge with Social Media Research is that the never forgetting and highly networked characteristic of the internet limits the effectiveness of traditional methods of anonymization and hence, users may often not be sufficiently protected against reidentification. (Reference Hunter, Gough and O’Kane4–Reference Azer9). For example, special risk of re-identification may occur in the space of rare diseases where only a small number of patients with unique combination of characteristics are active (Reference Gow, Moffatt and Blackport11).

Several measures can help to minimize the risk of identification. Firstly, only necessary data is collected, and any identifiable information is excluded. Secondly, data access permission policies as well as computer infrastructure cater for the safe use of data and prevent data loss or disclosure. Finally, reporting abstains from including any identifiable information. For example, quotes are frequently used in qualitative research. However, direct quotes may easily allow re-identification through a simple search tool. One way to reduce the risk of re-identification of individuals can be to distance the analysis from the point of data collection by using intermediaries (data/analysis brokers) (Reference Azer9).

Authenticity and justice

If Social Media Research is used to reveal matters relevant to the patients, healthcare decision makers must be able to trust that the conversation used for the research comes directly from the patients of interest (authenticity), that the breadth of patient population of interest is well represented by the research (representation), and the principle of justice is fulfilled. The principle of justice includes appropriate and fair participant selection, equal access to the research, and sharing in the benefits realized from the study findings (Reference Nebeker, Harlow, Giacinto, Orozco-Linares, Bloss and Weibel13).

Fake accounts, automated bots, or “astroturfing” (individuals adopt false identities and establish a false sense of group consensus or grassroot movements) are examples of how masses of Social Media communication are created that do not originate from the target population of the research (Reference Hunter, Gough and O’Kane4) and thus, are neither authentic nor representative. Thought must also be given to potential bias (Reference Hunter, Gough and O’Kane4–Reference Denecke12) and the risk of overreach (Reference Vitak, Proferes, Shilton and Ashktorab14), that is the inclusion of data of people who are not in the target population of the study.

The lack of authenticity, justice and representation can impede the relevance of the results. Due to the uncertainty around some of the requirements relating to authenticity, justice, and representativeness, the interpretative value of the information resulting from social media research needs to be verified and corroborated by other means (e.g., medical data, patient interviews/focus groups) (Reference Denecke12).

Beneficence and non-maleficence

The primary goal of any social media study should be beneficence, meaning the welfare of the participating subjects, and the avoidance of maleficence, meaning anything that opposes the welfare of any research participant. Hence, any social media research should only proceed if more benefits than harms are expected (Reference Nebeker, Harlow, Giacinto, Orozco-Linares, Bloss and Weibel13) and measures have been introduced to maximize benefits and minimize harms (Reference Hunter, Gough and O’Kane4). Key considerations in such assessments include (Reference Denecke12): (a) How can the data be utilized for the common good whilst respecting individual rights and liberties? (b) What are the acceptable trade-offs between individual rights and the common good? (c) How do we determine the acceptability thresholds for such trade-offs?

Context

In many cases of Social Media Research, most of the context of the communication will remain unknown as only certain parts of the communication are extracted and analyzed. When interpreting the data, the limitation of unknown context needs to be recognized, acknowledged, and its impact considered (Reference Samuel and Buchanan15;Reference Özkula16).

While context often is essential for precise understanding, revealing the contextual details may also increase the risk for identification. Hence, a balance must be found between which details of context are required for correct interpretation and which ones would expose individual subjects to the risk of re-identification.

The need for ethical review

Currently, researchers and Research Ethical Committees (REC) or Institutional Review Boards (IRB) are often left to their own devices in the development of their own frameworks based on trial-and-error learning approaches in an environment of rapidly changing and developing methods (Reference Hunter, Gough and O’Kane4). The formation of a flexible framework for things to consider and approaches to employ to maintain ethical conduct in public health research using social media data is recommended. Requirements may not be imposed by the IRB due to lack of expertise and guidance, but if they have potential ethical implications, they should still be considered by social media researchers (Reference Tan, Killela and Leckey17). Throughout the research life cycle, it is important for IRB/REC members to engage and listen to the researchers and build on their expertise which may originate from relevant practical engagement (Reference Sellers, Samuel and Derrick18).

Dedicated “technology ethics boards” (comprised of individuals with expertise in the technology as well as those versed in the ethical, legal, and social implications of data use) could be convened in universities and other research organizations to educate and advise scientists, research participants, IRBs, and the public (Reference Samuel, Derrick and van Leeuwen1–Reference Azer9;Reference Sellers, Samuel and Derrick18;Reference Pagoto and Nebeker19). Such boards should represent a broad range of perspectives (research, sociology, patient organizations, social media communication, computer scientists/data experts, legal knowledge) to reflect the breadth of perspectives from which Social Media Research in healthcare is undertaken or to be reviewed (Reference Samuel, Derrick and van Leeuwen1–Reference Pagoto and Nebeker19). Reviewers are trained regularly on new developments in social media (Reference Pagoto and Nebeker19), they inform themselves on the special issues related to research in social media, and guidance is appropriately updated and available to them.

Discussion and recommendations

With the intention of creating a simple guide not only for researchers and ethics reviewers, but also for HTA practitioners who use the results of Social Media Research, the findings of the scoping review were consolidated into a framework for future guidance tables (see Tables 1–3).

Table 1. Ethical and quality related aspects must be considered along the life-cycle of Social Media Research (adapted from (20))

Table 1 summarizes the guiding principles to consider in relation to the research tools, the data, and the ethical review process along the entire life cycle of Social Media Research form conceptualization and scoping to reporting and follow-up. For the tools and methods, the appropriateness, the reliability, and the replicability are of utmost importance. The research data must be representative and accessible to a broad range of the researched population, the required level of consent must be respected, and data should be sufficiently anonymized and safely managed and stored. The results need to be validated through other means and approaches. The ethics review process is not a one-time review and approval but happens along the lifecycle of the research throughout the planning of the research, the implementation of the study and the reporting, and is conducted by a specifically trained and up-to-date qualified review committee. Finally, a follow-up evaluation is performed to understand whether all risks and threats had been considered and whether the attitudes towards consent would change if the users had known that their data was used for this research.

In addition, Table 2 may serve as a more detailed checklist for the aspects related to research justification, research data and data sources, tools and methods, and legal requirements, which must be considered and reported in planning and reporting Social Media Research. While this checklist should be followed by researchers, it can also be used to document the appropriateness of the study for the potential use in HTA evidence appraisals.

Table 2. Principles for Social Media Research (adapted from (20–Reference Brosch, de Ferran and Newbould22) and others in this review)

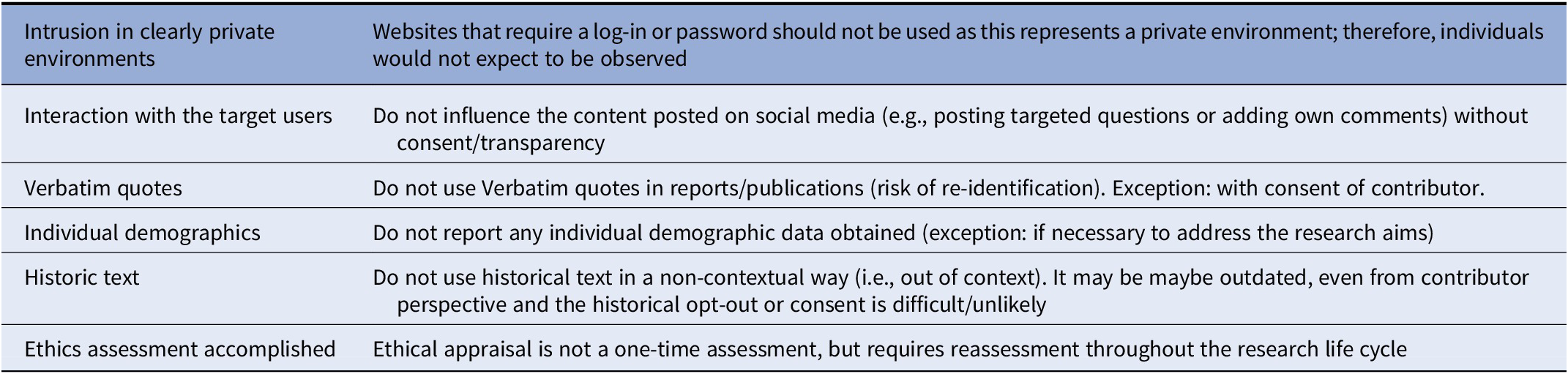

Finally, Table 3 summarizes some actions or activities that have been clearly identified to alleviate the risk to those who communicate on social media or to those they may communicate about or on behalf of, or to the quality of the research itself. Therefore, these actions should be avoided. They include intrusion in private environments (e.g., closed communities), uninvited interaction with target users, verbatim quotes or individual demographics in the reporting, the use of historic and potentially outdated data or text, and finally, the assumption that a point review for ethics is sufficient.

Table 3. Preventive considerations of actions to be avoided (based on (Reference Johnson, Kitchen and Marshall23–Reference Samuel and Derrick25))

Conclusions and recommendations for the use of social media research to inform HTA or health policy decision making

We have reviewed the existing guidance and current academic discourse of relevance related to the use of Social Media Research for generating patient insights that can inform HTA or health policy related decisions.

The main challenges reported in the publications were summarized together with the proposed measures for mitigation. Based on the findings of the scoping review in terms of the challenges and mitigation approaches, we propose in this report a set of practices and a checklist that can be applied when conducting Social Media Research to assure that the privacy and ethical risks are minimized. This aggregated list can be used for future guidance on the conduct of Social Media Research and for its use for decision making and should lay the base for further improvements in future based on the learnings resulting from systematic interaction between researchers and ethics experts as well as systematic follow-up.

Social Media Research has the promise to reveal new insights into patient needs, patient experiences, and, possibly, patient behaviors which could have high relevance to patient communities and give new directions for public health policies. However, the research approaches, methods, data interpretation, and communication may pose new challenges to researchers and ethics review boards in preventing potential harm to those who post the data on social media channels as well as to the people they are communicating about.

Although this report provides a set of principles and checklists on what to do and what to avoid when performing Social Media Research, it is strongly recommended to take an active and engaged approach to ensuring ethical innocuousness by carefully following best practices at each step of the research including the planning, the conduct, and the communication or dissemination. Throughout the process and as a follow-up, there should be a dialogue between the researchers and the ethics reviewers on a case-by-case basis to maximally protect the current and future users of social media, to support their trust in the research, and to advance the learnings in parallel to the advancement of the media themselves, the technologies, and the research tools.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462323000399.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the stakeholders who shared their opinions, observations, and critical considerations relating to social media research with us for their invaluable input. The Steering Committee of the Patient and Citizen Involvement in HTA Interest Group (PCIG), particularly the Chair Ann Single, has continuously reviewed the progress of the work and given input or made helpful connections in her network. The following people have given input in specific phases of the project: Lindsey Lockhart and Jennifer Dickson (Scottish Medicines Consortium, Healthcare Improvement Scotland), Sou-Hyun Lee (NECA, South Korea), and Jane Tsai (Vice-CEO of Formosa Cancer Foundation, Taiwan). Finally, we are grateful to the people who reviewed and commented on the report during the consultation phase.

Funding statement

The research underlying this paper received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The writing of the manuscript was financially supported by Novartis (Switzerland). The funding for the publication fees was provided by HTAi.

Competing interest

The work presented in this manuscript is the result of a project of the Patient and Citizen Involvement in HTA Interest Group (PCIG) of Health Technology Assessment international (HTAi; www.htai.org) which has received no funding. As a multi-stakeholder team, the authors come from different type of organizations: HTA (Y. Venable, M. Pierre, L.-Y. Huang), Patient Organizations (A. Silveira Silva, D. Walsh), Pharma & Med-Tech Industry (A. Danyliv, A. Krause, A. Hanna), Academia (J. Mattingly), and Consultancy (A.-P. Holtorf).