‘I have to say that this is a very well-done paper – substantial, important topic, innovative approach, well written and well organized, and built upon a sustained, thoughtful effort that has already paid dividends and, I would wager, that holds enormous potential [ … ] I did wonder just how good a fit this was for [journal] and specifically thought [ … ] would this paper not be a better fit in an eating disorders publication?’ Anonymous reviewer (Rejection decision on a manuscript by A.F.H.)

The above quote characterises an inaccurate sentiment familiar to eating disorder researchers: that eating disorders are ‘niche’ disorders. Manuscripts on eating disorders are more frequently rejected from general high-impact journals and recommended to disorder-specific journals than manuscripts on similar psychiatric concerns, owing to the belief that eating disorders represent a ‘specialty’ problemReference Strand and Bulik1 (additional citations supporting this and other statements in this Editorial can be found in Supplementary Material A, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2023.160). The suggestion that a paper perceived as important and innovative might be unsuitable to a general interest journal because of its topic is a problem of overspecialisation. Overspecialisation describes a restriction of reach and resources (e.g. high-impact publication, funding) due to a belief that a topic has lesser applicability to broader health disciplines, despite evidence to the contrary. There is consistent documentation suggesting overspecialisation of eating disorder research. Even this commentary on the dangers of the overspecialisation of the eating disorders field has been previously recommended for resubmission to a specialty eating disorder journal (Supplementary Material B). Funding for eating disorder research lags considerably behind that for other psychiatric disorders with comparable prevalence (US$0.73/affected individual for eating disorder research funding versus US$86.97/affected individual with schizophrenia).Reference Murray, Pila, Griffiths and Le Grange2 This pattern undermines the potential for eating disorder research to exert broader influence on knowledge and practice.Reference Strand and Bulik1 This trend is particularly concerning considering the severity, premature mortality and societal impact associated with eating disorders. Here, we detail how false assumptions may perpetuate overspecialisation of the eating disorder field, potentially obstructing critical research and treatment. We highlight the urgent need to embrace the study and treatment of eating disorders within and in partnership with broader mental health fields.

Debunking false assumptions

The overspecialisation of eating disorders may imply that these disorders are uncommon, disconnected from other mental illnesses and of lesser interest than other psychiatric concerns. Not only are these assumptions false, but they can reinforce the artificial barriers between psychiatric subfields and stall the development of effective supports for patients.

Eating disorders are not uncommon

The point prevalence of eating disorders is ~8% when using narrow classification standards and ~19% when using broader definitions.Reference Galmiche, Déchelotte, Lambert and Tavolacci3 Even these may be low estimates given the use of potentially biased methods (e.g. retrospective chart review). Eating disorder prevalence is also increasing. Since the appearance of COVID-19, hospital admissions for eating disorders have doubled and adolescent emergency visits have more rapidly increased for eating disorders than for other psychiatric concerns. Further, although certain forms of eating disorder behaviour (e.g. self-induced vomiting) may be relatively uncommon in the general population, at least one analysis suggests that ~50% of adolescents and adults engage in subclinical forms of disordered restrictive eating. Even subclinical disordered eating has been linked to myriad negative consequences (e.g. suicide, non-suicidal self-injury).

Eating disorders are not disconnected from other psychiatric concerns

Eating disorders are highly comorbid with other psychiatric disorders, including those considered more commonplace (e.g. depression, anxiety); 95% of individuals with an eating disorder have a co-occurring affective disorder and at least 20–35% of those with an affective disorder have an eating disorder. This elevated comorbidity suggests overlapping mechanisms between eating disorders and other psychiatric concerns. Eating disorder symptoms complicate treatment of other psychiatric disorders, highlighting the necessity of attending to eating disorder symptoms in general psychiatry.

Eating disorders are not less relevant to mainstream psychiatry

Despite eating disorder articles being under-published in general psychiatry journals, the most downloaded publication of 2021 from the high-impact outlet JAMA Psychiatry focused on the neurobiology of anorexia nervosa.Reference Frank, Shott, Stoddard, Swindle and Pryor4 This metric is especially striking given that <2% of JAMA Psychiatry articles in 2021 focused on eating disorder samples (versus ~16% on schizophrenia). This demonstrates a clear, widespread interest in eating disorder research, despite under-representation. Additionally, we argue that eating disorders are of urgent importance to psychiatry regardless of whether they garner general interest. Eating disorders are severe, debilitating, often persistent, and costly (~$400 billion/year in the USA). Anorexia nervosa is second only to opioid use disorder in lethality and other eating disorders share high premature mortality. Providers are often faced with life-or-death decisions in eating disorder care. These facts alone warrant increased attention on eating disorder research.

Why have false assumptions persisted?

It is unclear why eating disorders have been subject to more specialisation than other psychiatric disorders. One potential reason is that eating disorders have been inaccurately stereotyped as affecting only young, White, affluent, cisgender women. Although this misperception has been recently challenged by data demonstrating that eating disorders affect broader demographics than previously acknowledged, the harmful effects of this stereotype have likely perpetuated beliefs that eating disorders affect only a very specific segment of people. Additionally, whether or not it is reflective of the overall demographics of eating disorders, women are over-represented among eating disorder research samples (~95% of participants in eating disorder studies) and professionals (~84% of eating disorder academics are women, compared with ~40–55% in broader academic mental health). It is documented that women are disadvantaged in high-impact publishing and grant funding (even within the female-dominated eating disorder field)Reference Strand and Bulik1 and disorders that disproportionally affect women (e.g. endometriosis, premenstrual dysphoric disorder) are underfunded relative to disease burden. Therefore, the potential for gender bias underlying the overspecialisation of eating disorder research warrants consideration. Finally, eating disorders carry a unique physical risk, often necessitating specific interventions for medical stabilisation, which may enhance clinical specialisation.

The danger of false assumptions

There are real-world consequences of the overspecialisation within eating disorder research, which result in a deleterious cycle (Fig. 1). The less eating disorders are discussed in psychiatric training, journals and conferences, the less exposure professionals receive to this topic (Fig. 1(a)), which decreases the number of researchers and clinicians knowledgeable about eating disorders (Fig. 1(b)). Accordingly, psychiatric professionals are less likely to know of and collaborate with eating disorder researchers, apply for grants with eating disorder-focused projects or include eating disorder assessments in studies. New trainees, especially those historically under-represented in the eating disorder field, may not become familiar enough with eating disorder topics to pursue work in this area.

Fig. 1 The downstream effects and self-perpetuating cycle of overspecialisation within psychiatry.

Blue arrows and text: overspecialisation leads to siloing of information within the eating disorder (ED) field (a), which keeps work insular (b), reducing impact and impeding funding (c) and ultimately limiting the resources and workforce available for eating disorder treatment (d). Black arrows: in contrast, generalisation of eating disorder knowledge leads to increasing knowledge among mental health professionals (a), which promotes collaboration and an increase in the eating disorder workforce (b), increasing the impact and likelihood of funding (c), as well as resources and workforce to support eating disorder treatment (d).

Each of these issues can obstruct avenues for grant funding or high-impact, general-interest publications on eating disorders (Fig. 1(c)). Minimal exposure to information about eating disorders can also influence grant reviewers’ familiarity with the topic, potentially yielding uninformed and unenthusiastic reviews. Less research funding results in fewer well-resourced studies. For example, the authors of a letter to the American Journal of Psychiatry examined data on the quality of randomised controlled trials on eating disorders compared with panic disorder and agoraphobia, finding that studies on eating disorders were rated of lower quality.Reference Mendlowicz, Figueira and Souza5 They argued that lower-quality studies, rather than systematic bias and underfunding, were responsible for under-representation of eating disorder studies in high-impact journals. That correspondence was published 20 years ago and may not reflect current quality standards. However, if the quality of eating disorder research continues to be a concern, we raise the possibility that this reduced quality may not just be a cause, but also a consequence of the overspecialisation cycle described above. Lack of exposure to a topic can have an impact on the likelihood of funding for that topic, thereby affecting the quality of research on it and perpetuating the cycle. These issues have downstream effects on the resources and workforce available to identify and treat these serious disorders (Fig. 1(d)).

These damages are already apparent. Most healthcare providers do not receive training in eating disorders and do not assess for or treat these disorders. Most eating disorders go undetected, untreated or ineffectively treated; less than 20% of individuals with an eating disorder ever receive treatment. The mechanisms promoting eating disorders remain poorly understood and eating disorder treatment effects have not improved in decades. Overspecialisation of eating disorders also limits the ability to identify transdiagnostic mechanisms that account for comorbidity between eating disorders and other disorders, possibly impeding progress on both sides. A literature review by Ahuvia et al found that body image interventions decrease depression to the same degree as treatments specifically targeting depression – reinforcing the value and need for other fields to collaborate with eating disorder researchers. Ultimately, the above cycle results in less high-quality research being conducted on serious illnesses that can be fatal.

Beyond assumptions to action

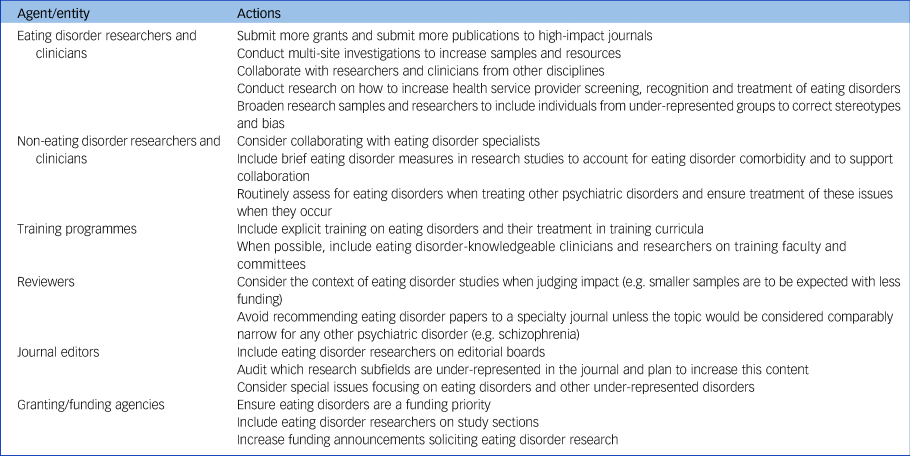

This Editorial is a call to action for funders, editors and researchers to take steps towards reducing misperceptions that silo eating disorders from other disciplines, with the end goal of promoting greater funding, high-impact research and access to treatment for these disorders. In Table 1, we provide recommendations on how to extend the eating disorder field's reach. Overspecialisation is not unique to eating disorders; therefore, these recommendations are relevant to other disorders frequently considered niche (e.g. personality disorders). Our aim is widespread recognition that, although eating disorders are many things – serious, puzzling, life-threatening – they are not niche.

Table 1 Actionable steps to extend the impact of eating disorder research

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2023.160.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

A.H.E. and A.F.H. contributed to the conceptualisation of this editorial. All authors provided input on the outline of topics addressed and were responsible for primary drafting and editing of the editorial. A.F.H. was responsible for incorporation of edits and manuscript formatting.

Funding

The authors receive funding as principal investigators from the National Institute of Health Office of the Director (DP5OD028123), National Institute of Mental Health (K08MH120341, R01MH126978, R15MH121445, R34MH124799, R34MH126965, R34MH127203, R34MH128213, R34MH129464, R43MH128075), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23DK132500), National Science Foundation (2141710), National Eating Disorders Association, Office on Women's Health of the US Department of Health & Human Services, the Upswing Fund for Adolescent Mental Health, Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation, and HopeLab. The preparation of this article was supported in part by the Implementation Research Institute (IRI) at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St Louis, through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (R25MH080916; J.L.S. is an IRI Fellow).

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.