Clozapine has been shown to be better in treating symptoms of schizophrenia than conventional antipsychotic drugs. Forty to 60 per cent of patients with refractory chronic schizophrenia will make clinically significant improvements with clozapine, based on high-quality evidence accepted by opinion leaders, policy-makers and purchasers of care (Reference Wahlbeck, Cheine and EssaliWahlbeck et al, 1998). Clozapine, although essentially free of extrapyramidal side-effects, has a wide range of side-effects of its own, the most important being agranulocytosis. Although expensive, there is evidence to suggest that acquisition costs are recouped by future savings on in-patient care (Reference Aitchison and KerwinAitchison & Kerwin, 1997). In view of this evidence base 10 years after its UK licence, we aimed to examine patterns of clozapine prescribing in the NHS. We set out to explain any inequalities in prescribing either arising as variations in need or in provision, since analysis of such variations can reveal insights into policy and practice (Reference KnappKnapp, 1997).

The study

We obtained prescribing data from all 12 NHS catchment area mental health provider units in an English county (total population 2 499 487), at three census dates: 1 April 1996, 1 November 1997 and 1 May 1998. Specialist tertiary care services such as forensic units were not included. We also obtained prescribing analysis and cost (PACT) information for the same timescale. PACT information was from the six health authorities that provided month-on-month expenditure details for other atypical antipsychotic drugs in primary care. This allowed for a longitudinal analysis over the 2-year period.

Findings

Raw data for the first census date showed cross-sectional prescribing rates to range between two and 52 patients per trust. Table 1 details the clozapine prescribing figures by each trust on the three census dates.

Table 1. Clozapine prescribing — raw data

| Census Date | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| NHS trust | 1 April 96 | 1 November 97 | 1 May 98 |

| A | 11 | 20 | 13 |

| B | 37 | 32 | 32 |

| C | 41 | 40 | 41 |

| D | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| E | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| F | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| G | 15 | 14 | 15 |

| H | 52 | 60 | 65 |

| I | 39 | 35 | 37 |

| J | 28 | 25 | 29 |

| K | 18 | 23 | 61 |

| L | 14 | 16 | 17 |

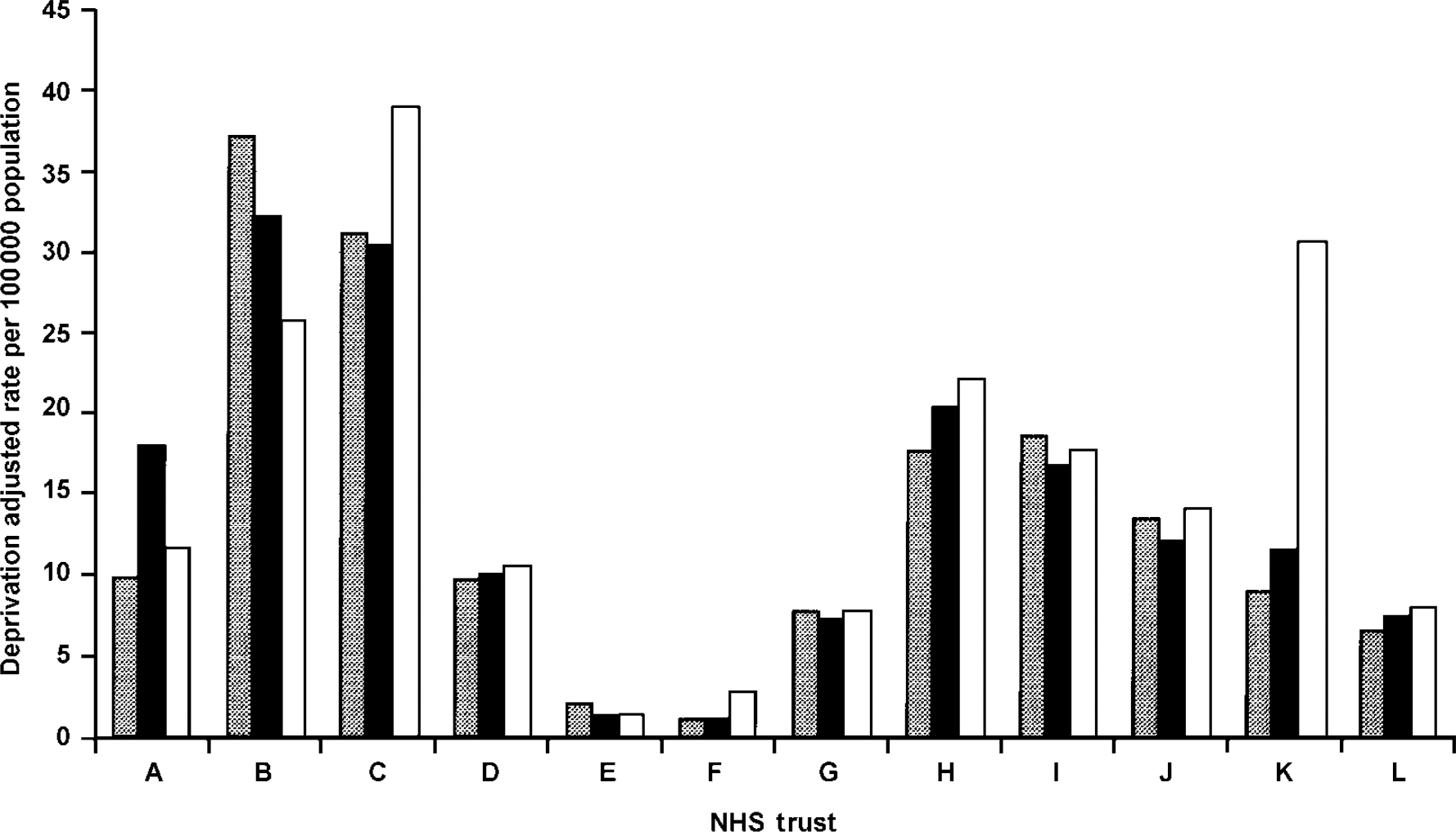

To test whether these differences reflected variations in local population need, rates were corrected for population size and deprivation, using the Mental Illness Needs Index, shown to predict mental health service usage (Reference GloverGlover, 1998). Population size and need-adjusted prescribing data showed a 34-fold variation between trusts, as shown in Fig. 1. This confirmed that the reason for inequalities was not population need. Therefore, we tested a series of hypotheses concerning supply.

Fig. 1. Rates of clozapine prescribing in 12 provider units population and deprivation adjusted. [UNK], 1 April 1996; ▪, 1 November 1997; □, 1 May 1998

First, we ensured that no purchaser- or provider-imposed limits on availability were in force: prior to the availability of high-quality evidence, local policies had often restricted clozapine use. This was not the case at either of the last two census dates for any of the 12 units. Three trusts (C, D and K) used drug treatment algorithms for the prescribing of antipsychotic medication prior to and following the three census dates.

Second, we checked whether trusts with lower prescribing rates at census date 1 were merely at an earlier stage of evidence-based practice by comparing rates with those at census dates 2 and 3. We found no decrease in variation between trusts at each of the three time-points: in fact, an increase was evident, suggesting the gap was not closing (s.d.s=15.6, 16.0, 20.2).

Third, although overprescribing of clozapine is inherently unlikely given its cost and licensing restrictions, we tested whether this had occurred in the high prescribing trusts. Using Conley & Buchanan's (Reference Conley and Buchanan1997) accepted criteria for treatment resistance, the case records of the 31 patients most recently prescribed clozapine were examined in the highest prescribing trust (C). All of these cases were found to have conformed to these criteria, with persistent symptoms despite full trials of at least two different antipsychotic classes.

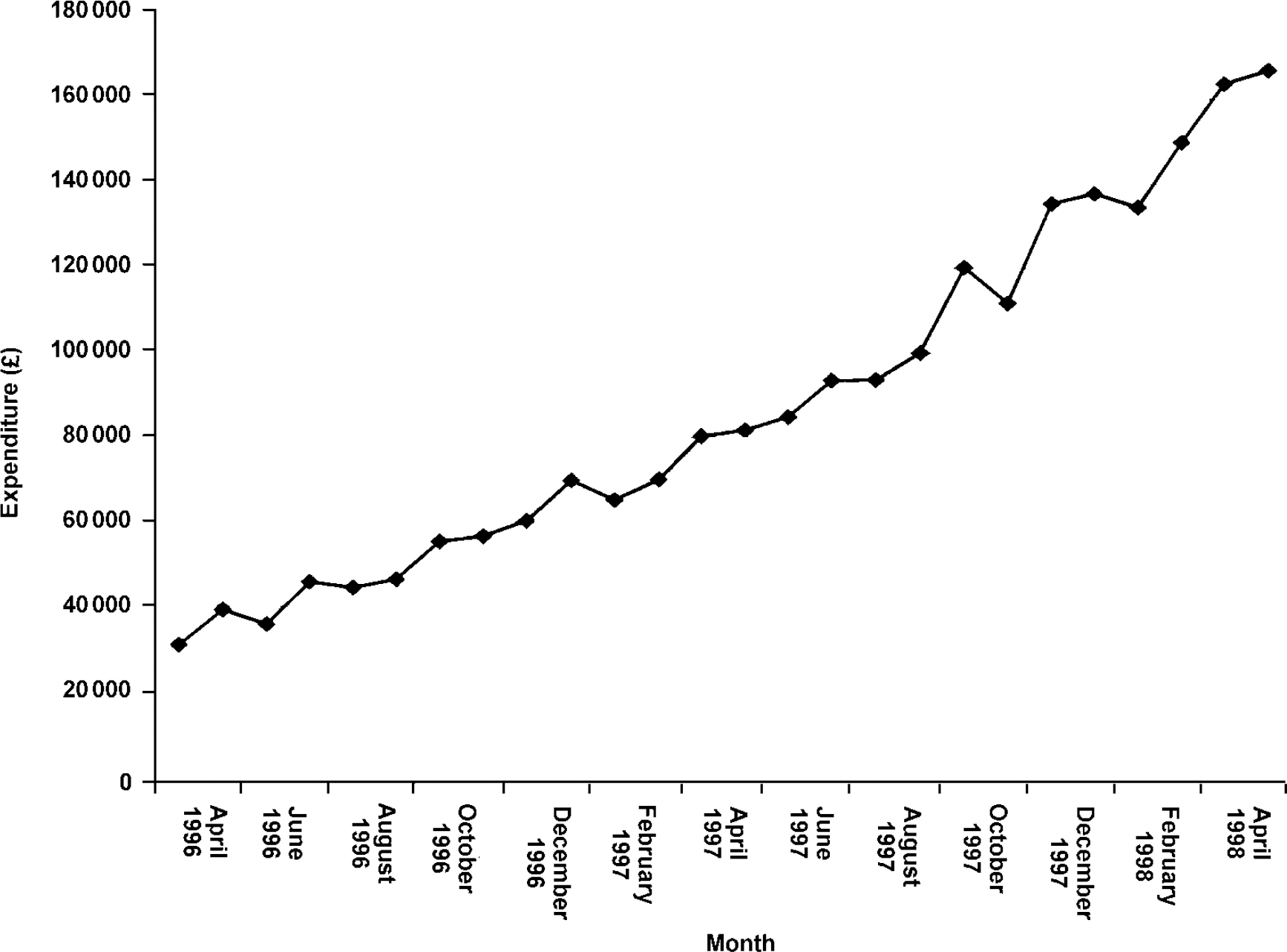

Fourth, we tested whether an alternative health technology was being provided for resistant schizophrenia in the low-prescribing trusts. Although the evidence base as yet gives formal support only to clozapine in resistant schizophrenia, there are emerging data for the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural therapy (Reference Tarrier, Yuupoff and KinneyTarrier et al, 1998) and good evidence for family interventions in preventing relapse (Reference Mari and StreinerMari & Streiner, 1994). On examination, the only four trusts to make available such services were the four highest, as opposed to the lowest, prescribers of clozapine. The newer atypical antipsychotic drugs introduced since clozapine may offer advantages over conventional drugs, although there is no good evidence that they are effective in treatment resistant schizophrenia (Reference Tuunainen and GilbodyTuunainen & Gilbody, 1999). Nonetheless, we tested whether they were being prescribed in lieu of clozapine in the low prescribing trusts. We found no evidence to support this. Rates of prescribing of this class of drug increased six-fold over the census interval (see Fig. 2), with rates of prescribing of the atypical antipsychotics showing in fact a positive correlation, r=0.4, rather than a negative, with rates for clozapine. Despite the place of new atypicals being less clear in schizophrenia management than clozapine, need adjusted variation between health authorities on the final census date was considerably less for new atypicals than for clozapine.

Fig. 2. Primary care prescribing of atypical antipsychotic medication

Our remaining hypothesis was that the variations in clozapine prescribing reflected variations in evidence-based clinical practice. We sought to test this by a case note review in a sample of the providers (Trusts A, C, E, F, G, H, I, J and L). This included all case notes of in-patients with an ICD-10 diagnosis of schizophrenia (World Health Organization, 1997; F20-F20.9) between 1 April 1996 and 31 March 1998. There were 1996 patients admitted during that period. Of the 777 case notes reviewed, 64% were male, 36% female and average age was 41 years. We checked for a putative marker of non-evidence-based practice: the prescribing of two or more antipsychotic drugs in parallel in the same patient. We found a 37% rate for such polypharmacy: in 33% there were two conventional drugs, 14% an atypical prescribed with a conventional drug and 0.4% were being prescribed two atypical antipsychotic drugs in parallel. The rates of polypharmacy between the trusts ranged from 28-51% of patients. The lowest prescribing trust for clozapine had the highest percentage of such polypharmacy.

Comment

Access to appropriate care in the new NHS is intended to be “on the basis of need and need alone” (Secretary of State for Health, 1997). Doctors appear to have a statutory duty to prescribe what patients need, although the introduction of new drugs can be slow. Clozapine has been available in the NHS since 1990. Despite robust evidence about its unique efficacy and probable cost-effectiveness in severe schizophrenia, its availability to patients in the county studied was uneven, with no evidence of this changing over the 2-year period examined.

Recent media attention has focused on the role of financial constraints imposed by health authorities as a main source of the variance in availability of clozapine nationally. Our data suggest that differences in evidence-based clinical practice at the provider/prescriber level are the main source of variance. There is a need to strengthen the evidence base available to clinicians in order to improve and develop local prescribing strategies based on patient need. Without change at this level special funding strategies by health authorities to support clozapine will have little impact on its availability to patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the trusts and health authorities for helping with data collection for the study and Dr Peter Elton, Director of Public Health, Wigan and Bolton Health Authority.

S.L. had the original idea for the study and obtained funding. H.P. was involved in data collection, with analysis and writing of the paper by both S.L. and H.P.

The study was supported by grants from Greater Manchester Health Authorities and the Stanley Foundation. No commercial funding was involved.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.